Part 2: The Battle of the Hedgerows

Blank page

Chapter 4: The Offensive Launched

The Preparations

Designated to lead off in the U.S. First Army offensive to the south, VIII Corps was to advance twenty miles along the Cotentin west coast, secure high ground near Coutances, and form the western shoulder of a new army line extending to Caumont. The line was to be gained after VII, XIX, and V Corps attacked in turn in their respective zones. A quick thrust by VIII Corps promised to facilitate the entire army advance. By threatening the flank of enemy units opposing U.S. forces in the center, the corps would help its neighbors across the water obstacles and the mire of the Cotentin. At the conclusion of the offensive action across the army front, the Americans would be out of the swampland and on the dry ground of Normandy bocage.

The VIII Corps held a fifteen-mile front in a shallow arc facing a complex of hills around the important crossroads town of la Haye-du-Puits. Athwart the Cherbourg-Coutances highway and dominating the surrounding countryside, these hills formed a natural defensive position on which the Germans anchored the western flank of their Normandy front. Just to the south of the hill mass, the firm ground in the corps zone narrowed to seven miles between the Prairies Marécageuses de Gorges and the tidal flats of the Ay River. This ground was the VIII Corps’ initial objective. (Map 3)

Charged with the task of unhinging the German line at its western end was Maj. Gen. Troy H. Middleton, a soldier with a distinguished and extensive combat career. He had enlisted in the Regular Army in 1910 and had risen during World War I to regimental command and the rank of colonel. He had demonstrated his competence in World War II as a division commander in Sicily and Italy. Several months before the invasion of western Europe he had assumed command of the VIII Corps, and nine days after the continental landing the corps headquarters had become operational in France with the mission of protecting the rear of the forces driving on Cherbourg. The terrain that had been of great assistance to the VIII Corps in June now inversely became an aid to the enemy.

Looking south across hedgerowed lowland toward la Haye-du-Puits, General Middleton faced high ground between sea and marsh, heights that shield the town on three sides. On the southwest, Hill 84 is the high point of the Montgardon ridge, an eminence stretching almost to the sea. On the north, twin hills, 121 and 131 meters in height, and the triplet hills of the Poterie ridge rise abruptly. To the east, Mont Castre lifts

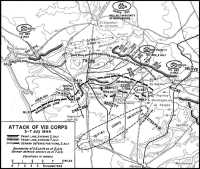

Map 3: Attack of VII Corps, 3–7 July 1944

its slopes out of the marshes. The adjacent lowlands make the hill masses seem more rugged and steep than they are. To reach the initial objective, VIII Corps had first to take this commanding terrain. General Middleton had three divisions, veterans of the June fighting. All were in the line, the 79th Infantry on the right (west), the 82nd Airborne in the center, and the 90th Infantry on the left. Because the 82nd was soon to be returned to England to prepare for projected airborne operations, General Middleton assigned the division only a limited objective, part of the high ground north of la Haye-du-Puits. The 79th Division on the right and the 90th on the left were to converge and meet below the town to pinch out the airborne infantrymen. Thus, the corps attack was to resemble a V-shaped thrust, with the 82nd clearing the interior of the wedge. The terrain dictated the scheme of maneuver, for the configuration of the coast and the

westward extension of the marecage narrowed the corps zone south of la Haye-du-Puits. To replace the airborne troops, the 8th Division was to join the corps upon its arrival in France. Expecting to use the 8th Division beyond the initial objective, staff officers at corps headquarters tentatively scheduled its commitment to secure the final objective, Coutances.

Thus the VIII Corps was to make its attack with three divisions abreast. Each was to secure a portion of the heights forming a horseshoe around la Haye-du-Puits: the 79th was to seize the Montgardon ridge on the west and Hill 121; the 82nd Airborne was to capture Hill 131 and the triplet hills of the Poterie ridge in the center; and the 90th, making the main effort, was to take Mont Castre on the east. With the commanding ground about la Haye-du-Puits in hand, the 79th Division was to push south to Lessay. There, where the tidal flats of the Ay River extend four miles inland and provide an effective barrier to continuing military operations southward, the 79th was to halt temporarily while the 90th continued with the newly arrived 8th.1

Two problems confronted VIII Corps at the start of the attack: the hedgerow terrain north of la Haye-du-Puits and the German observation points on the commanding ground around the town. To overcome them, General Middleton placed great reliance on his nine battalions of medium and heavy artillery, which included two battalions of 240-mm. howitzers; he also had the temporary assistance of four battalions of the VII Corps Artillery. Only on the afternoon before the attack did he learn that he was also to have extensive air support. In accordance with routine procedure, the air liaison officer at corps headquarters had forwarded a list of five targets considered suitable for air bombardment—suspected supply dumps and troop concentration areas deep in the enemy rear. A telephone call from First Army headquarters disclosed that General Eisenhower had made available a large number of aircraft for employment in the VIII Corps zone. When assured “You can get all you want,” the corps commander submitted an enlarged request that listed targets immediately in front of the combat troops.2 Allied intelligence was not altogether in agreement on the probable German reaction to the American offensive. Expecting a major German counterattack momentarily, higher headquarters anticipated strong resistance.3 On the other hand, the VIII Corps G-2, Col. Andrew R. Reeves, thought either a counterattack or a strong defense most unlikely. Because of the inability or reluctance of the Germans to reinforce the Cherbourg garrison, because of their apparent shortage of artillery ammunition and their lack of air support, and because of the

La Haye-du-Puits. Road at top leads south to Périers and Coutances.

probable low morale of their soldiers, he considered an immediate counterattack improbable. Nevertheless, he recognized that if the Germans were to keep the Allies from expanding their bridgehead, they would eventually have to counterattack. Until they could, it was logical that they try to keep the Allied beachhead shallow by defending where they stood. Colonel Reeves believed, however, that they lacked the strength to remain where they were. He expected that as soon as they were driven from their main line of resistance near la Haye-du-Puits, they would withdraw through a series of delaying positions to the high ground near Coutances.4

That VIII Corps would drive the enemy back was a matter of little doubt, since it was generally believed on the lower levels that the corps had “assembled a force overwhelmingly superior in all arms. ... ”5 Below the army echelon, intelligence reports exaggerated the

fragmentary nature of German units and underestimated German organizational efficiency and flexibility. The First Army G-2 cautiously estimated that the German infantry divisions in Normandy averaged 75 percent of authorized strength and lacked much equipment. But the VIII Corps G-2 judged that among the enemy forces on his immediate front “the German divisional unit as such ... has apparently ceased to exist.”6 Perhaps true in the last week of June, the latter statement was not accurate by the first week in July.

For all the optimism, combat patrols noted that the Germans had set up an exceptionally strong outpost screen, replenished their supplies, reorganized their forces, and resumed active reconnaissance and patrolling. It was therefore reasonable to assume that the enemy had strengthened his main line of resistance and rear areas. Morale had undoubtedly improved. On the other hand, intelligence officers judged that enemy morale and combat efficiency had risen only from poor to fair. Germans still lacked aggressiveness when patrolling; critical shortages of mines and wire existed; and artillery fired but sporadically, indicating that the Germans were undoubtedly conserving their meager ammunition supplies to cover delaying action as they withdrew.7

Confidence and assurance gained in the Cherbourg campaign led most Americans to expect no serious interruption in the offensive to the south. A schedule of artillery ammunition expenditures allotted for the attack revealed temporary removal of restrictions and a new system of self-imposed unit rationing. Although ammunition stocks on the Continent were not copious, they appeared to be more than adequate. Even though officers at First Army warned that unreasonable expenditures would result in a return to strict controls, the implicit premise underlying the relaxation of controls for the attack was the belief that each corps would have to make a strong or major effort for only two days. Two days of heavy artillery fire by each corps was considered adequate to propel the army to the Coutances–Caumont line.8

In the two days immediately preceding the attack, U.S. units on the VIII Corps front noted a marked change in enemy behavior. German artillery became more active; several tanks and assault guns made brief appearances; small arms, automatic weapons, and mortar fire increased in volume; infantrymen seemed more alert. American patrols began to have difficulty moving into hostile territory. Only in the corps center could reconnaissance patrols move more freely into areas formerly denied them. From these indications, corps concluded that the enemy was preparing to make a show of resistance before withdrawing.9

Commanders and troops making last-minute preparations for the jump-off watched in some dismay a few minutes after midnight, 2 July, as a drizzling rain began to fall. The early morning attack hour was fast approaching when the rain became a downpour. It was

obvious that the heavy air program promised in support of the offensive would have to be canceled.10 As events developed, not even the small observation planes, invaluable for locating artillery targets in the hedgerow country, were able to get off the ground.

Despite this early disappointment, the attack otherwise began as scheduled. American troops plodded through the darkness and the mud toward the line of departure. At 0515, 3 July, the artillery started a 15-minute preparation.

The Defenses

The Germans had no intention of falling back. From the high ground near la Haye-du-Puits, so dominating that observers on the crests could watch Allied shipping off the invasion beaches, Germans studied the preparations for the attack they had been expecting for almost two weeks. They were ready. Yet despite their readiness, they were almost taken by surprise. The state of affairs harked back to the development of the LXXXIV Corps defenses west of the Prairies Marécageuses de Gorges.

In June, just before American troops had cut the Cherbourg peninsula and isolated the port, Rundstedt, Rommel, Dollman, and Fahrmbacher had decided to divide the LXXXIV Corps forces into two groups—one in the north to defend Cherbourg, the other to block American movement south. Their intention had been to leave weak forces in defense of Cherbourg and to build a strong line across the Cotentin from Portbail to the Prairies Marécageuses de Gorges.11 By insisting on compliance with original plans for a forceful defense of Cherbourg, however, Hitler had disrupted the German commanders’ plan. As a result, the troops in the south were weaker than had been hoped. The designated chief of the forces in the south (Generalleutnant Heinz Hellmich of the 243rd Division) was killed in action on 17 June, and Col. Eugen Koenig (the acting commander of the 91st Infantry Division, whose general had died on 6 June) became the local commander responsible for erecting a defense to halt the expected drive to the south.

Koenig had had available a total of about 3,500 combat effective soldiers of several units: remnants of the 91st and 243rd Divisions, a Kampfgruppe of the 265th Division (from Brittany), and miscellaneous elements including Osttruppen, non-German volunteers from eastern Europe. Together, the troops composed about half the effective combat strength of a fresh infantry division. With these few forces, but with adequate artillery in support, Koenig had fashioned a line that utilized marshland as a defensive barrier.

When Choltitz had taken command of the LXXXIV Corps, he had soon come to the conclusion that he could not depend on Koenig to hold for long. American paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division had actually penetrated the marsh line as early as 12 June.12 Koenig’s forces were too weak to

eliminate the penetration or to hold the positions already seriously threatened. The Osttruppen were not always reliable.13 Besides, Choltitz felt that the high ground near la Haye-du-Puits was better defensive terrain. He therefore had his reserve units—the 353rd Division, which had just arrived from Brittany, and remnants of the 77th Division establish positions on the Montgardon ridge and on Mont Castre. The ridge defenses, sometimes called the Mahlmann Line after the commander of the 353rd, were hastily organized because of anxiety that the Americans might attack at any moment. When the positions were established, Choltitz regarded them as his main line of resistance. Thinking of Koenig’s troops as manning an outpost line, he expected them to resist as long as possible and eventually to fall back to the ridge line.

In contrast with Choltitz’s idea, Rundstedt had recommended that the main line of resistance be established even farther back—at the water line formed by the Ay and Sèves Rivers. Although Choltitz did not place troops there, he considered the water line a convenient rally point in case withdrawal from the la Haye-du-Puits positions became necessary.14 Hitler, who disapproved of all defensive lines behind the front because he feared they invited withdrawal, wanted Koenig’s positions to be held firmly. To inculcate the idea of holding fast, he had Koenig’s defenses designated the main line of resistance. With Koenig’s marsh line marked on maps as the main defenses in the area, the fresh troops of the 353rd Division seemed unoccupied. In order to use them, OKW ordered Hausser to have Choltitz move the 353rd to replace the panzer grenadiers in the eastern portion of the corps sector. The panzer grenadiers were to disengage and become a mobile reserve for the Seventh Army. With the 353rd scheduled to depart the high ground around la Haye-du-Puits, Choltitz had to reduce the Mahlmann Line to the reality of a rally line manned entirely by the Kampfgruppe of the 77th.

By 3 July the 77th Division troops had moved to the eastern part of Mont Castre, while the 353rd was moving from ridge positions to assembly near Périers. The VIII Corps attack thus occurred at a time of flux. Members of the LXXXIV Corps staff had correctly assumed, from the noise of tank motors they heard during the night of 2 July, that an American attack was in the making, and they had laid interdictory fires on probable assembly areas. But judging that the rain would delay the jump-off—on the basis that bad weather neutralized American air power—the Seventh Army staff mistakenly labeled the VIII Corps offensive only a reconnaissance in force with tank support. The real American intention soon became apparent to both headquarters, however, and Hausser and Choltitz recalled the 353rd Division from Périers and repositioned the men on the high ground about la Haye-du-Puits.15 Hitler’s desires notwithstanding, these positions became the main line of resistance.

As a result of the last-minute changes that occurred on 3 July, the Germans opposing VIII Corps were able to defend from positions in depth. Fanned out in front was Group Koenig, with parts of the 91st, the 265th, and the 243rd Divisions on the flanks, and east European volunteers (including a large contingent of Russians) generally holding the center. Artillery support was more than adequate—the entire division artillery of the 243rd, plus two cannon companies, five antitank companies, a complete tank destroyer battalion, and an assortment of miscellaneous howitzers, rocket launchers, antiaircraft batteries, captured Russian guns, and several old French light tanks. Behind Group Koenig, the 353rd and a Kampfgruppe of the 353rd were to defend the high ground of the Montgardon ridge and Mont Castre. The 2nd SS Panzer Division, assembling well south of St. Lô in Seventh Army reserve, was able to move, if needed, to meet a serious threat near la Haye-du-Puits.16 Even closer, in the center of the LXXXIV Corps sector, south of Périers, was one regiment (the 15th) of the 5th Parachute Division (still in Brittany). Although under OKW control, it could probably be used in an emergency to augment the la Haye-du-Puits defenses. All together, the German forces were far from being a pushover.

Poterie Ridge

In the VIII Corps attack, the 82nd Airborne Division had the relatively modest role of securing a limited objective before departing the Continent for England. Having fought on French soil since D Day, the airborne division had lost about half its combat strength. Yet it still was an effective fighting unit, with three parachute infantry regiments and one glider infantry regiment forming the principal division components.

The troops had been carefully selected for airborne training only after meeting special physical and mental standards. The division had participated in World War II longer than most units in the European theater, and its members regarded with pride their achievements in Sicily and Italy. To an esprit de corps that sometimes irritated others by its suggestion of superiority, the aggressive veterans added a justifiable respect and admiration for their leaders. Maj. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway, the division commander, displayed an uncanny ability for appearing at the right place at the right time. His inspiring presence, as well as that of the assistant division commander, Brig. Gen. James M. Gavin, was responsible in no small degree for the efficiency of the unit.17

In the center of the VIII Corps sector, the 82nd Airborne Division held a line across the tip of a “peninsula” of dry ground. In order to commit a maximum number of troops at once, General Ridgway planned to sweep his sector by attacking westward—between marshland on the north and the la Haye-du-Puits—Carentan road on the south—to take the hills just east of the St. Sauveur-le-Vicomte—la Haye-du-Puits road, which separated the airborne division’s zone

from that of the 79th Division. The terrain was hedgerowed lowland, with half a dozen tiny settlements and many farmhouses scattered throughout the countryside; there were no main roads, only rural routes and sunken lanes.

In the early hours of 3 July, even before the artillery preparation that signaled the start of the First Army offensive, a combat patrol made a surprise thrust. Guided by a young Frenchman who had served similarly in the past, a reinforced company of the 505th Parachute Infantry (Lt. Col. William Ekman) slipped silently along the edge of the swamp and outflanked German positions on the north slope of Hill 131. At daybreak the company was in the midst of a German outpost manned by Osttruppen. Startled, the outpost withdrew. The main body of the regiment arrived by midmorning and gained the north and east slopes of the hill. Four hours later the 505th was at the St. Sauveur-le-Vicomte—la Haye-du-Puits road and in possession of the northern portion of the division objective. The regiment had taken 146 prisoners and had lost 4 dead, 25 wounded, and 5 missing.18

The 508th Parachute Infantry (Col. Roy E. Lindquist) had similar success in gaining the southeast face of Hill 131, and a battalion of the 507th Parachute Infantry (Col. Edson D. Raff) cleared its assigned sector. The leading units moved so rapidly that they bypassed enemy troops who were unaware that an attack was in progress. Though the U.S. follow-up forces had the unexpected and nasty task of clearing small isolated groups, the leading units were at the base of the objective by noon and several hours later were ensconced on the slope. Casualties were few.

On the left the story was different. Making the main division effort, the 325th Glider Infantry (Col. Harry L. Lewis) was to move west to the base of the Poterie ridge, then up and down across each of the triplet hills. After a slow start caused by enemy mines, the regiment moved rapidly for a mile. At this point the advance stopped—two miles short of the eastern slope of the Poterie ridge. One supporting tank had hit a mine, three others were floundering in mud-holes, and German fire rained down from the slopes of Mont Castre, off the left flank.

It did not take long for General Ridgway to recognize the reason for easy success of the regiments on the right and the difficulty of the 325th. While the parachute regiments on the right were rolling up the German outpost line, the glider men had struck the forward edge of the German main line of resistance. At the same time, they were exposed to observed enfilading fire from Mont Castre.

To deal with this situation, Ridgway directed the 325th commander to advance to the eastern edge of the Poterie ridge. Using this position as a pivot, the other regiments of the division were to wheel southward from their earlier objectives and hit the triplet hills from the north in frontal attacks.

Colonel Lewis renewed the attack during the evening of 3 July, and although the glider men advanced over a mile and a half, they were still 600 yards short of

their objective when resistance and darkness forced a halt two hours before midnight. When another effort on the morning of 4 July brought no success, General Ridgway ordered the wheeling movement by the other regiments to begin. Each battalion of the 508th was to attack one of the triplet hills while the 505th moved south along the division boundary to protect the open right flank.

Problems immediately arose when two battalions of the 508th and the glider regiment disputed the use of a covered route of approach. Because of the delay involved in coordinating the route and because of withering fire from both the Poterie ridge and Mont Castre, the two battalions made little progress during the day. The third battalion, on the other hand, had by noon gained a position from which it could assault the westernmost eminence, Hill 95. Following an artillery preparation reinforced by corps guns, two rifle companies made a double envelopment while the third attacked frontally. The battalion gained the crest of the hill but, unable to resist the inevitable counterattack that came before positions could be consolidated, withdrew 800 yards and re-formed.

Meanwhile, troops of the 505th moved south along the division boundary, advancing cautiously. Reaching the base of Hill 95 that evening, the regiment made contact with the 79th Division and set up positions to control the St. Sauveur-le-Vicomte—la Haye-du-Puits road.

His battalions now in direct frontal contact with the German positions but operating at a disadvantage under German observation, General Ridgway ordered a night attack. As darkness fell on 4 July, the men moved up the hedgerowed and unfamiliar slopes of the Poterie ridge. The 325th Glider Infantry secured its objective on the eastern slope of the ridge with little difficulty. The battalion of the 508th Parachute Infantry that had taken Hill 95 during the afternoon only to lose it walked up the slope and secured the crest by dawn. A newly committed battalion of the 507th Parachute Infantry, moving against the easternmost hill, had trouble maintaining control in the darkness, particularly after making contact with the enemy around midnight. Withdrawing to reorganize, the battalion commander sent a rifle company to envelop the hill from the east while he led the remainder of his force in a flank approach from the west. Several hours after daylight on 5 July the two parties met on the ridge line. The Germans had withdrawn.

Another battalion of the 507th moved against the center hill of the Poterie ridge, with one company in the lead as a combat patrol. Reaching the crest without interference and assuming that the Germans had retired, the advance company crossed the ridge line and formed a defensive perimeter on the south slope. Daybreak revealed that the men were in a German bivouac area, and a confused battle took place at close range. The remainder of the battalion, which had stayed on the north slope, hurried forward at the sound of gunfire to find friend and foe intermingled on the ridge. Not until afternoon of 5 July did the battalion establish a consolidated position.19

During the afternoon the 82nd Airborne Division reported Hill 95 captured and the Poterie ridge secure. Small isolated German pockets remained to be cleared, but this was a minor task easily accomplished. Maintaining contact with the 79th Division on the right and establishing contact with the 90th Division in the valley between the Poterie ridge and Mont Castre on the left, the 82nd Airborne Division assumed defensive positions.

In advancing the line about four miles in three days, the airborne division had destroyed about 500 enemy troops, taken 772 prisoners, and captured or destroyed two 75-mm. guns, two 88-mm. antitank guns, and a 37-mm. antitank weapon. The gains had not been without serious cost. The 325th Glider Infantry, which was authorized 135 officers and 2,838 men and had an effective strength of 55 officers and 1,245 men on 2 July, numbered only 41 officers and 956 men four days later; the strongest rifle company had 57 men, while one company could count only 12. Casualties sustained by this regiment were the highest, but the depletion of all units attested to the accuracy of German fire directed from superior ground.

By the morning of 7 July, all enemy pockets had been cleared in front of the airborne division. Lying in the rain-filled slit trenches, the men “began to sweat out the much-rumored trip to England.”20 The probability appeared good: two days earlier the 79th Division had briefly entered la Haye-du-Puits, the 90th had moved up the slopes of Mont Castre, and the 8th was almost ready to enter the lines.

Mont Castre

The action at the Poterie ridge was not typical of the VIII Corps attack launched on 3 July, for while the 82nd Airborne Division swept an area relatively lightly defended, the 79th and 90th Divisions struck strong German positions in the la Haye-du-Puits sector. Trying to execute the V-shaped maneuver General Middleton had projected, the infantry divisions hit the main body of the LXXXIV Corps on two major elevations, the Montgardon ridge and Mont Castre. Their experience was characteristic of the battle of the hedgerows.

The ability of the 90th Division, which was making the corps main effort on the left (east), was an unknown quantity before the July attack. The performance of the division during a few days of offensive action in June had been disappointing. The division had lacked cohesion and vigor, and its commanding general and two regimental commanders had been relieved. Maj. Gen. Eugene M. Landrum, with experience in the Aleutian Islands Campaign the preceding year, had assumed command on 12 June and had attempted in the three weeks before the army offensive to reorganize the command and instill it with aggressiveness.21

To reach his assigned portion of the corps intermediate objective, General Landrum had to funnel troops through a corridor a little over a mile wide—a corridor between Mont Castre on the west and the Prairies Marécageuses de Gorges on the east. His troops in the corridor would have to skirt the edge of the swampland and operate in the shadow of Mont Castre, a ridge about 300 feet high extending three miles in an east-west direction. The western half of Mont Castre, near la Haye-du-Puits, was bare, with two stone houses standing bleakly in ruins on the north slope. The eastern half, densely wooded and the site of an ancient Roman encampment, offered cover and concealment on a height that commanded the neighboring flatland for miles. No roads mounted to the ridge line, only trails and sunken wagon traces—a maze of alleys through the somber tangle of trees and brush. If the Germans could hold the hill mass, they could deny movement to the south through the corridor along the base of the eastern slope. Possession of Mont Castre was thus a prerequisite for the 90th Division advance toward Périers.

Reflecting both an anxiety to make good and the general underestimation of German strength, General Landrum planned to start his forces south through the corridor at the same time he engaged the Germans on Mont Castre. The division was to attack with two simultaneous regimental thrusts. The 359th Infantry (Col. Clark K. Fales), on the right, was to advance about four miles through the hedgerows to the thickly wooded slopes of Mont Castre, take the height, and meet the 79th Division south of la Haye-du-Puits. The 358th Infantry (Col. Richard C. Partridge), on the left, was to force the corridor between Mont Castre and the prairies. In possession of the high ground, in contact with the 79th Division, and holding the corridor east of Mont Castre open, General Land-rum would then commit the 357th Infantry (Col. George H. Barth) through the corridor to the initial corps objective.

To provide impetus across the hedge-rowed lowlands, General Landrum ordered the 357th, his reserve regiment, to mass its heavy weapons in support and the attached tanks and tank destroyers also to assist by fire. In addition to the organic artillery battalions, General Landrum had a battalion of the corps artillery and the entire 4th Division Artillery attached; the 9th Division Artillery had been alerted to furnish fires upon request.

The driving, drenching rain, which had begun early on 3 July, was still pouring down when the attack got under way at 0530. At first it seemed that progress would be rapid. Two hours later resistance stiffened. By the end of the day, although American troops had forced the Germans out of some positions, the Seventh Army commander, Hausser, was well satisfied. His principal concern was his supply of artillery ammunition.22

The 90th Division advanced less than a mile on 3 July, the first day of attack, at a cost of over 600 casualties.23

The Germans demonstrated convincingly, contrary to general expectation, that they intended and were able to make a stand. The 90th Division dented only the outpost line of resistance and had yet to make contact with the main defenses. “The Germans haven’t much left,” an observer wrote, “but they sure as hell know how to use it.”24

If the Germans had defended with skill, the 90th Division had not attacked with equal competence. Tankers and infantrymen did not work closely together; commanders had difficulty keeping their troops moving forward; jumpy riflemen fired at the slightest movement or sound.

The experience of Colonel Partridge’s 358th Infantry exemplified the action along the division front for the day. One of the two assault battalions of the regiment remained immobile all day long not far from the line of departure because of flanking fire from several German self-propelled guns. The other battalion moved with extreme caution toward the hamlet of les Sablons, a half-dozen stone farmhouses in a gloomy tree-shaded hollow where patrols on preceding days had reported strong resistance. As infantry scouts approached the village, enemy machine gun and artillery fire struck the battalion command post and killed or wounded all the wire communications personnel. Unable to repair wire damaged by shell-bursts, the unit commanders were without telephones for the rest of the day.

Judging the enemy fire to be in large volume, Colonel Partridge withdrew the infantry a few hundred yards and requested that division artillery “demolish the place” with white phosphorus and high-explosive shells. The artillery complied literally, and at noon riflemen were moving cautiously through the village. Ten minutes later several enemy tracked vehicles appeared as if by magic from behind nearby hedgerows. A near panic ensued as the infantrymen fled the town. About twelve engineers who were searching for mines and booby traps were unable to follow and sought shelter in the damaged houses.

To prevent a complete rout, Partridge committed his reserve battalion. Unfortunately, several light tanks following the infantry became entangled in concertina wire and caused a traffic jam. Anticipating that the Germans would take advantage of the confusion by counterattacking with tanks, Partridge ordered a platoon of tank destroyers to bypass les Sablons in order to fire into the flank of any hostile force. He also called three assault guns and three platoons of the regimental antitank company forward to guard against enemy tanks. The 315th Engineer Combat Battalion contributed a bazooka team to help rescue the men trapped in the village.

The Germans did not attack, and in midafternoon Partridge learned that only one assault gun and two half-tracked vehicles were holding up his advance. It was late afternoon before he could act, however, for German shells continued to fall in good volume, the soft lowland impeded the movement of antitank weapons, and the presence of the American engineers in les Sablons inhibited

the use of artillery fire. After the engineers had worked their way to safety, Partridge at last brought coordinated and concentrated tank, artillery, and infantry fire on the area, and a rifle company finally managed to push through les Sablons that evening. Colonel Partridge wanted to continue his attack through the night, but an enemy counterthrust at nightfall, even though quickly contained, convinced General Landrum that the regiment had gone far enough.

The excellent observation that had enabled the Germans to pinpoint 90th Division activity during the day allowed them to note the American dispositions at dusk. Through the night accurate fire harassed the division, rendering reorganization and resupply difficult and dangerous.

Resuming the attack on 4 July, the 90th Division fired a ten-minute artillery preparation shortly after daybreak. The German reaction was immediate: counter-battery fire so intense that subordinate commanders of the 90th Division looked for a counterattack. Not wishing to move until the direction of the German thrust was determined, the regimental commanders delayed their attacks. It took vociferous insistence by General Landrum to get even a part of the division moving. No German counterattack materialized.

Colonel Fales got his 359th Infantry moving forty-five minutes after the scheduled jump-off time as a surprising lull in the German fire occurred. Heading for Mont Castre, the infantry advanced several hundred yards before the enemy suddenly opened fire and halted further progress. Uneasy speculation among American riflemen that German tanks might be hiding nearby preceded the appearance of three armored vehicles that emerged from hedgerows and began to fire. The infantrymen withdrew in haste and some confusion.

Through most of the day, all attempts to advance brought only disappointment. Then, at dusk, unit commanders rallied their men. Unexpectedly the regiment began to roll. The advance did not stop until it had carried almost two miles.25

The sudden slackening of opposition could perhaps be explained by several factors: the penetration of the airborne troops to the Poterie ridge, which menaced the German left; the heavy losses sustained mostly from the devastating fire of American artillery; and the lack of reserves, which compelled regrouping on a shorter front. With great satisfaction the Germans had reported that their own artillery had stopped the 90th Division attack during the morning of 4 July, but by noon the LXXXIV Corps was battling desperately. Although two battalions of the 265th Division (of Group Koenig), the 77th Division remnants, and a battalion of the 353rd Division succeeded in denying the approaches to Mont Castre throughout 4 July, the units had no local reserves to seal off three small penetrations that occurred during the evening. Only by getting OKW to release control of the

15th Parachute Regiment and by committing that regiment at once was the Seventh Army able to permit the LXXXIV Corps to refashion its defensive line that night.26

Despite their difficulties, the Germans continued to deny the 90th Division entrance into the corridor between Mont Castre and the swamp. German fire, infiltrating riflemen, and the hedgerows were such impediments to offensive action that Colonel Partridge postponed his attack several times on 4 July. Most of his troops seemed primarily concerned with taking cover in their slit trenches, and American counterbattery fire seemed to have little effect on the enemy weapons.

When part of the 358th Infantry was pinned down by enemy artillery for twenty minutes, the division artillery investigated. It discovered that only one enemy gun had fired and that it had fired no more than ten rounds. Despite this relatively light rate of fire, one rifle company had lost 60 men, many of them noncommissioned officers. The commanding officer and less than 65 men remained of another rifle company. Only 18 men, less than half, were left of a heavy weapons company mortar platoon. A total of 125 casualties from a single battalion had passed through the regimental aid station by midafternoon, 90 percent of them casualties from artillery and mortar shelling. Tired and soaking wet from the rain, the riflemen were reluctant to advance in the face of enemy fire that might not have been delivered in great volume but that was nonetheless terribly accurate.

Although German fire continued, the 358th Infantry got an attack going late in the afternoon toward the corridor. With the aid of strong artillery support and led by Capt. Phillip H. Carroll, who was wounded in one eye, the infantry moved forward several hundred yards to clear a strongpoint.27 By then it was almost midnight. Because the units were badly scattered and the men completely exhausted, Colonel Partridge halted the attack. Long after midnight some companies were still organizing their positions.

On its second day of attack, 4 July, the 90th Division sustained an even higher number of casualties than the 600 lost on the first day.28 Mont Castre, dominating the countryside, “loomed increasingly important.” Without it, the division “had no observation; with it the Boche had too much.”29

More aware than ever of the need for Mont Castre as a prerequisite for an advance through the corridor, General Landrum nevertheless persisted with his original plan, perhaps because he felt that the Germans were weakening. Judging the 358th Infantry too depleted and weary for further offensive action, he committed his reserve regiment, the 357th, on 5 July in the hope that fresh troops in the corridor could outflank Mont Castre.

The 357th Infantry had only slight success in the corridor on 5 July, the

third day of the attack, but on the right the 359th registered a substantial gain. Good weather permitted tactical air support and observed artillery fires, and with fighter-bombers striking enemy supply and reinforcement routes and artillery rendering effective support, the regiment fought to the north and northeast slopes of Mont Castre in a series of separate, close-range company and platoon actions. Still the Germans continued to resist aggressively, launching repeated local counterattacks.30 The failure of the 357th Infantry to force the corridor on the left and the precarious positions of the 359th on the slopes of Mont Castre at last compelled General Landrum to move a battalion of the 358th Infantry to reinforce his troops on Mont Castre, the beginning of a gradual shift of division strength to the right.

Colonel Fales on 6 July sent a battalion of his 359th Infantry in a wide envelopment to the right. Covered by a tactical air strike and artillery fire and hidden by hedgerows on the valley floor, the infantry mounted the northern slope of Mont Castre. At the same time, the other two battalions of the 359th and a battalion of the 358th advanced toward the northeastern part of the hill mass. Diverted by the wide envelopment that threatened to encircle their left and forced to broaden their active front, the Germans fell back. The result was that by nightfall four battalions of U.S. infantry were perched somewhat precariously on Mont Castre. Not only did General Landrum have possession of the high ground, he also owned the highest point on the ridge line—Hill 122.

Success, still not entirely certain, was not without discomfiture. The wide envelopment had extended the 90th Division front. A roving band of Germans on the afternoon of 6 July had dispersed a chemical mortar platoon operating in direct support of an infantry battalion, thus disclosing gaps in the line, and had harassed supply and communications personnel, thus revealing the tenuous nature of the contact between the forces in the valley and those on the high ground.31 To fill the gaps and keep open the supply routes, General Landrum committed the remaining two battalions of the 358th Infantry in support of his units on Mont Castre, even though concentrating the weight of his strength on the right deprived the troops on the left of reserve force. Two complete regiments then comprised a strong division right.

The decision to reinforce the right did not entirely alleviate the situation. The terrain impeded efforts to consolidate positions on the high ground. Underbrush on the eastern part of the hill mass was of such density and height as to limit visibility to a few yards and render movement slow. The natural growth obscured terrain features and made it difficult for troops to identify their map locations and maintain contact with adjacent units. The incline of the hill slope, inadequate trails, and entangling thickets made laborious the task of bringing tanks and antitank guns forward.32

Evacuation of the wounded and supply of the forward troops were hazardous

because obscure trails as well as the main routes were mined and because many bypassed or infiltrating Germans still held out in rear areas. The understrength infantry battalions were short of ammunition, water, and food. Seriously wounded soldiers waited hours for transportation to medical installations. One regiment could hardly spare guards or rations for a hundred German prisoners. Vehicles attempting to proceed forward came under small arms and artillery fire. Much of the resupply and evacuation was accomplished by hand-carry parties that used tanks as cargo carriers as far as they could go, then proceeded on foot. A typical battalion described itself as “in pretty bad shape. Getting low on am and carrying it by hand. Enemy coming around from all sides; had 3 tks with them. Enemy Arty bad. Ours has been giving good support. No report from [the adjacent] 1st Bn.”33 General Landrum relieved one regimental commander, who was physically and mentally exhausted. About the same time the other was evacuated for wounds.

Rain, which began again during the evening of 6 July, added to General Landrum’s concern. Conscious of the enemy’s prior knowledge of the terrain and his skillful use of local counterattack at night as a weapon of defense, General Landrum drew on the regiment engaged in the corridor to shift a battalion, less one rifle company, to reinforce Mont Castre and alerted his engineers for possible commitment as infantry.

General Landrum’s anxiety was justified, for the enemy counterattacked repeatedly during the dark and rainy night, but on the morning of 7 July the 90th Division still possessed Hill 122 and the northeast portion of the ridge. One battalion summed up the action by reporting that it was “a bit apprehensive” but had “given no ground.”34

Continuing rain, deep mud, and the difficulty of defining the enemy front hindered further attempts on 7 July to consolidate positions on Mont Castre. Judging the hold on the high ground still to be precarious, General Landrum placed all three lettered companies of the engineer battalion into the line that evening.35 With the division reconnaissance troops patrolling the north edge of the Prairies Marécageuses de Gorges to prevent a surprise attack against the division left flank and rear, one battalion of the 357th Infantry, less a rifle company, remained the sole combat element not committed. During the night of 7 July General Landrum held onto this battalion, undecided whether the situation on Mont Castre was more critical than that which had developed during the past few days in the corridor on the left.

In the corridor, Colonel Barth’s 357th Infantry had first tried to advance along the eastern base of Mont Castre on the morning of 5 July. Shelling the regimental command post, the Germans delayed the attack for an hour and a half. When the fire subsided, Colonel Barth sent a battalion of infantry in a column of companies, supported by

tanks, toward the hamlet of Beaucoudray, the first regimental objective.

Between the regimental line of departure and Beaucoudray, a distance of about a mile, a tar road marked the axis of advance along a corridor bordered on the east by encroaching swamps, on the west by a flat, grassy meadow at the foot of Mont Castre. Near Beaucoudray, where the ruins of a fortified castle indicated that the terrain was tactically important a thousand years earlier, a slight ground elevation enhanced the German defense. The position on the knoll was tied in with the forces on Mont Castre.

Aided by artillery, infantry and tanks entered the corridor on 5 July, knocked out a German self-propelled gun, and moved to within 1,000 yards of Beaucoudray before hostile artillery and mortar fire halted further advance. With inadequate space for the commitment of additional troops, the battalion in the corridor sought cover in the hedgerows while the enemy poured fire on the men. A platoon of 4.2-inch chemical mortars in support became disorganized and returned to the rear.

On 6 July, early morning mist and, later, artillery and mortar smoke shells enabled a rifle company to advance through Beaucoudray and outpost the hamlet.36 This displacement created room for part of the support battalion. While two rifle companies north of Beaucoudray covered by fire, two other companies advanced several hundred yards south of the village. The result gave Colonel Barth good positions in the corridor—with three rifle companies south of Beaucoudray, two immediately north of Beaucoudray, and one at the entrance to the corridor, the regiment at last was ready to drive toward the division objective.

The achievement was actually deceptive. The troops were in a defile and in vulnerable positions. As nightfall approached and with it the increasing danger of counterattack, Colonel Barth moved his regimental antitank guns well to the front. His defense lost depth when General Landrum decided to move the battalion that constituted Barth’s regimental reserve to reinforce the Mont Castre sector. Fortunately, Landrum left one company of the battalion in position north of the corridor as a token regimental reserve.

The Germans, meanwhile, had reinforced their positions in the la Haye-du-Puits sector with the 15th Parachute Regiment and had been making hurried attempts since 5 July to commit part of the 2nd SS Panzer Division, the last of the Seventh Army reserve, in the same sector. To maintain their principal defenses, which were excellent, and allow reinforcements to enter them, the Germans had to remove the threat of encirclement that Colonel Barth’s 357th Infantry posed in the corridor. Remnants of the 77th Division therefore prepared an attack to be launched from the reverse slope of Mont Castre.37

At 2315, 6 July, enemy artillery and mortar fire struck the right flank of the U.S. units in the corridor as a prelude to an attack by infantry and tanks. The American antitank weapons deployed generally to the front and south were for the most part

ineffective.38 One of the three rifle companies south of Beaucoudray fell back on the positions of a company north of the village. The other company north of Beaucoudray fell back and consolidated with the company at the entrance to the corridor. The six rifle companies of the two battalions became three two-company groups, two of them—those immediately north and south of Beaucoudray—in close combat with the enemy. Fused together by the pressure of the German attack, the consolidated two-company units inside the corridor fought through a rainy, pitch-black night to repel the enemy. When morning came the group north of the village appeared to be in no serious danger, but the group south of Beaucoudray had been surrounded and cut off.

To rescue the isolated group, Colonel Barth on 7 July mounted an attack by another rifle company supported by two platoons of medium tanks. Despite heavy casualties from mortar fire, the infantry reached the last hedgerow at the northern edge of Beaucoudray. There, the company commander committed his supporting tanks. A moment later the commander was struck by enemy fire. As the tanks moved up, the Germans launched a small counterattack against the right flank. By this time all commissioned and noncommissioned officers of the company had been either killed or wounded. Deprived of leadership, the infantrymen and tankers fell back across the muddy fields. Difficulties of reorganizing under continuing enemy fire prevented further attempts to relieve the encircled group that afternoon.

In quest of ammunition, a small party of men from the isolated group reached safety after traversing the swamp, but the battalion commander to whom they reported deemed the return trip too hazardous to authorize their return. In the early evening, radio communication with the surrounded companies ceased. Shortly afterward a lone messenger, after having made his way through the swampy prairies, reported that one company had surrendered after enemy tanks had overrun its command post. Although Colonel Barth made his reserve company available for a night attack to relieve any survivors, the ineptitude of a battalion commander kept the effort from being made.

Sounds of battle south of Beaucoudray ceased shortly after daylight on 8 July. When six men, who had escaped through the swamp, reported the bulk of both companies captured or killed, Barth canceled further rescue plans.39 Apprehensive of German attempts to exploit the success, he formed his regimental cooks and clerks into a provisional reserve.

After five days of combat the 90th Division had advanced about four miles at a cost of over 2,000 casualties, a loss that reduced the infantry companies to skeleton units. Though this was a high price, not all of it reflected inexperience and lack of organization. The division had tried to perform a difficult mission in well-organized and stubbornly defended terrain. The German defenders were of equal, perhaps superior numbers—approximately 5,600 front-line combat-effective troops of the 91st, 265th, 77th,

and 353rd Infantry Divisions, the 15th Parachute Regiment, and lesser units. The pressure exerted by the 90th Division alone had forced LXXXIV Corps to commit all its reserve, Seventh Army to commit certain reserves, and OKW to release control of the parachute regiment, its only reserve in the theater. Wresting part of Mont Castre from the enemy had been no mean achievement. Though fumbling and ineptitude had marked the opening days of the July offensive, the division had displayed workmanship and stamina in the fight for Mont Castre.

To commanders at higher echelons, possession of undeniably precarious positions on Mont Castre and failure to have forced the Beaucoudray corridor seemed clear indications that the 90th Division still had to learn how to make a skillful application of tactical principles to hedgerow terrain. The division had demonstrated continuing deficiencies, hangovers from its June performance. Some subordinate commanders still lacked the power of vigorous direction. Too many officers were overly wary of counterattack. On the surface, at least, the division appeared to have faltered in July as it had in June. The conclusive evidence that impressed higher commanders was not necessarily the failure to secure the initial objectives south of la Haye-du-Puits in five days, but the fact that by 8 July the division seemed to have come to a halt.

Montgardon Ridge

While the 90th Division had been attacking Mont Castre and probing the corridor leading toward Périers, the 79th Division, on the VIII Corps right, had made its effort along the west coast of the Cotentin. On the basis of the attack on Cherbourg in June, the 79th was considered a good combat unit.40 Imbued with high morale and commanded by the officer who had directed its training and baptism of fire, Maj. Gen. Ira T. Wyche, the division was in far better shape for the July assignment than was the 90th.

During the first phase of the VIII Corps drive to Coutances, General Wyche was expected to clear his zone as far south as the Ay River estuary, seven miles away. He anticipated little difficulty.41 To reach his objective, he had first to secure the high ground in his path near la Haye-du-Puits—the Montgardon ridge and its high point, the flat top of Hill 84. Capture of the height would give General Wyche positions dominating la Haye-du-Puits and the ground descending southward to the Ay, would make la Haye-du-Puits untenable for the Germans, and would permit the 79th to meet the 90th approaching from the corps left.

To take the Montgardon ridge, the 79th Division had to cross six miles of hedgerowed lowland defended by remnants of the 243rd Division and under the eyes of a battalion of the 353rd Division entrenched on the ridge. Only a frontal assault was possible. The division was also to seize the incidental objective of Hill 121, a mound near the left boundary that provided good observation toward la Haye-du-Puits and

Montgardon. General Wyche planned to send the 314th Infantry against Hill 121 on the left while the 315th moved toward the Montgardon ridge on the right.

Attempting to outflank Hill 121, the 314th Infantry (Col. Warren A. Robinson) drove toward la Haye-du-Puits on the rainy morning of 3 July with a rifle company on each side of the main road.42 Machine gun and mortar fire from a railway embankment parallel to the road stopped the leading units after a half-mile advance, but the heroic action of a single soldier, Pfc. William Thurston, got the attack moving again. Charging the embankment and eliminating the enemy machine gunners in one position with rifle fire, Thurston penetrated the German line and unhinged it.43 His companions quickly exploited the breach, and by the end of the afternoon they had gained about three miles. There, the leading battalion halted and set up blocking positions to protect a separate advance on Hill 121. Another battalion that had followed was to turn left and approach the hill in a flanking maneuver from the southwest.

A large bare mound, Hill 121 was adorned by a small ruined stone house reputed to be of Roman times, a romanesque chapel, and a water tower. Also visible were German fortifications of sandbagged logs. Spearheaded by a twelve-man patrol, the battalion started toward the base of the hill at dusk. As the men disappeared into the hedgerows, the regimental commander lost communications with the command party. At 2300, when General Wyche instructed his regiments to halt for the night, no acknowledgment came from the men moving on Hill 121. Not until 0230, 4 July, when an artillery liaison officer who apparently possessed the only working radio in the command reported the battalion closing on the objective did any word emerge. An hour later the same officer provided the encouraging news that the battalion was on the hill.

Upon receipt of the first message, Colonel Robinson, the commander of the 314th, had immediately dispatched his reserve battalion to assist. At daybreak both forces were clearing the slopes of Hill 121. The Germans had held the hill with only small outposts. By midmorning of 4 July Hill 121 was secure. The division artillery had an excellent observation post for the battle of the Montgardon ridge and la Haye-du-Puits. On 4 July the 314th Infantry moved to within two miles of la Haye-du-Puits and that evening established contact with the 82nd Airborne Division on the left. Because heavy German fire denied the regiment entry into la Haye-du-Puits, the infantry dug in and left the artillery to duel with the enemy.

The artillery would be needed on the Montgardon ridge because the 315th Infantry (Col. Bernard B. McMahon) still had a long way to go toward that objective, despite encouraging progress

during the morning of 3 July. With two battalions abreast and in columns of companies, the third echeloned to the right rear, and a company of tanks in close support, the regiment at first advanced slowly but steadily; self-assurance and optimism vanished just before noon when three concealed and bypassed German armored vehicles on the coastal flank opened fire. The loss of several tanks promoted panic, and infantrymen streamed to the rear in confusion.

Because artillery and antitank weapons reacted effectively, the disruption to the attack proved only temporary, although not until midafternoon were tanks and infantry sufficiently reorganized to resume the attack. By nightfall the 315th had advanced a little over a mile.

Movement through the hedgerows toward Montgardon was slow again on the second day of the attack until the observation provided by the 314th Infantry’s conquest of Hill 121 began to show effect. Such good progress had been made by afternoon that the division artillery displaced its battalions forward.

Not until evening, when the infantry was two miles short of Hill 84 and taking a rest, did the Germans react with other than passive defense. Enemy infantry supported by armored vehicles suddenly emerged from the hedgerows. Two rifle companies that had halted along a sunken road were temporarily surrounded, but 50 men and 4 officers held firm to provide a bulwark around which the dispersed troops could be reorganized. As the division artillery went into action with heavy fire, the regiment built up a solid defensive perimeter. The Germans had counterattacked to cover a withdrawal of the 243rd to the main line of defense on the Montgardon ridge. During the action the Germans took 64 prisoners.44

Temporarily checked in the drive on the Montgardon ridge, General Wyche ordered the 314th Infantry to enter la Haye-du-Puits the next morning, 5 July, in the hope of outflanking the German positions on the high ground. Moving down mined and cratered roads to the northeastern outskirts of town, one company formed a base of fire while another slipped into the railroad yard. The success was short-lived, for enemy artillery and mortar fire soon drove the company back.

By midmorning of 5 July General Wyche had decided on a new, bold move, which he hoped might explode the division out of its slow hedgerow-by-hedgerow advance and perhaps trap a sizable number of Germans north of the Ay River. He committed his reserve, the 313th Infantry (Col. Sterling A. Wood), in a wide envelopment to the right, to pass across the western end of the Montgardon ridge and drive rapidly downhill to the Ay.

Starting at noon on 5 July, the 313th Infantry moved toward the ridge with a two-company tank-infantry task force in the lead. Marshy terrain and lack of adequate roads slowed the movement. By late afternoon the task force was still several hundred yards short of the ridge. As the troops reached a water-filled ditch running through the center of a flat grassy meadow, they came under such a volume of artillery fire that the

advance stalled. Just before dark the enemy counterattacked twice and drove the task force and the rest of the regiment several miles back in confusion. Before daybreak, 6 July, few would have attested either to the location or the integrity of the regiment. Mercifully, the Germans did not exploit their success. The regiment found time to regroup.

Disappointed in the results of the 313th Infantry advance even before the counterattack, General Wyche late on 5 July had again sent the 315th, supported by tanks and tank destroyers, directly against Hill 84. This time the regiment reached the north slope of the hill. The 79th Division at last had a toehold on the highest part of the Montgardon ridge.

To reinforce this success and prepare for final conquest of the ridge, General Wyche on 6 July jockeyed his other two regiments. He ordered the 314th to swing its right around la Haye-du-Puits and gain a foothold on the eastern slope. The regiment accomplished its mission during the morning. He turned the 313th eastward from its location on the division right rear to positions in support of the troops on Hill 84. By noon of 6 July, the fourth day of the attack, the 314th and 315th Regiments were on the northern and eastern slopes of Montgardon, while the 313th was echeloned to the right rear at the base of the ridge.

In ordering all three regiments to attack during the afternoon to carry the crest, General Wyche bowed to the compartmentalizing effect of the hedgerow terrain and told each commander to attack alone when ready. The technique worked. Although the 313th Infantry on the right gained no ground against strong positions protected by wire and mines, the 315th in the center overran Hill 84, and the 314th on the left completed occupation of the eastern portion of the main ridge. By daybreak of 7 July the 79th Division could note that la Haye-du-Puits was outflanked, that the Germans ought now to abandon the town, and that as soon as earlier advances were extended to cover the entire ridge, the division might head south toward the Ay River.

It did not take long on 7 July for General Wyche and his subordinate commanders to realize that this kind of thinking was premature. The Germans held doggedly to the rest of the high ground. They also stayed in la Haye-du-Puits; an American patrol accompanied by a German prisoner who was recruited to talk the garrison into surrender could not even get past the first houses. The Germans not only refused to budge from the high ground and the town, they prepared to attack. Having hurriedly reinforced the la Haye-du-Puits sector with a small portion of the 2nd SS Panzer Division, Choltitz launched his counterattack on the afternoon of 7 July as armored contingents in about two-battalion strength assaulted the Montgardon ridge.45

The German armored troops struck with such violence and behind such a volume of supporting fire that the first blow almost pushed the 79th Division off the ridge. In an attempt to achieve better coordination between the two regiments on the main ridge, General Wyche placed both under one commander.

The expedient worked. Soon the infantry, artillery, tanks, and tank destroyers began to execute a coordinated defense. Destruction of three German tanks appeared to extinguish the spark of the German drive.46 By nightfall the Germans were stopped, but gone was the optimistic belief that a quick drive to the Ay would be possible.

In five days of hedgerow fighting, the 79th Division had attained the crest of the Montgardon ridge but was still short of the intermediate objective. Though the division casualties in the hedgerows had not been consistently high, the fighting on the high ground on 7 July alone resulted in over 1,000 killed, wounded, and missing. The cumulative total for five days of battle was over 2,000.47 Seriously depleted in numbers, its remaining troops badly in need of rest, and some units close to demoralization in the face of seemingly incessant German shelling, the 79th Division was no longer the effective force that had marched to Cherbourg the preceding month. For the moment the 79th seemed no more capable of effective offensive combat than did the 90th.

Initiating the First Army offensive, the VIII Corps had failed to achieve the success anticipated. The Germans had indicated that they were prepared and determined to resist. They had given up little ground, defended stubbornly, and utilized the hedgerows and observation points with skill. They had employed their weapons on a scale not expected by the Americans and had inflicted a large number of casualties. Although the VIII Corps took 543 prisoners on 3 July, 314 on 4 July, 422 on 5 July, and 203 on 6 July, they were inferior troops for the most part, non-Germanic eastern Europeans, and the corps could look forward to no sudden enemy collapse.

The rain had been a severe handicap to the Americans. Although limited visibility gave the troops some measure of concealment and protection from the German fire, the weather had denied the corps the full use of its available resources in fire power and mobility. Not until the third day of the offensive had tactical air been able to undertake close support missions, and two days later recurring poor weather conditions again had forced cancellation of extensive air support. Operations of the small artillery observation planes were also limited by weather conditions. Finally, the rain had transformed the moist fields of the Cotentin into ponds of mud that immobilized in great part the motorized striking force of the American tracked and wheeled vehicles.

The 82nd Airborne Division had swept across an area for the most part lightly defended and had displayed a high degree of flexibility and effectiveness in meeting the problems of hedgerow warfare. If the 79th and 90th Divisions seemed less adaptable and less professional than the airborne troops, they had met enemy forces at least numerically equal in strength who occupied excellent defenses. The two infantry divisions had nevertheless by the end of 7 July breached the German main line of defense. By then, replacements untested by battle comprised about 40 percent of

their infantry units. With both the 79th and the 90th Division needing rest and the aggressive 82nd Airborne Division about to depart the Continent, its place to be taken by the inexperienced 8th Division, VIII Corps could expect no sudden success. On the other hand, the Germans could anticipate no respite, for to the east the U.S. VII Corps in its turn had taken up the battle.