Part 5: Breakout to the East

Blank page

Chapter 22: Week of Decision

As operations had begun in Brittany during the early days of August, Allied and German commanders were making decisions that markedly altered the development of the campaign. The immediate consequence of the decisions on both sides decreased the importance of Brittany. Normandy remained the stage for continuing action that would soon become vital.

The German Decision

The seriousness of the German situation at the time of the American breakthrough to Avranches was not lost on Hitler.1 The Balkans and Finland were about to be lost, and there were indications that Turkey might soon enter the war against Germany. Hitler considered these events as a kind of external defection over which he had little control. The Putsch of July 20th, on the other hand, was an internal defection that threatened him personally, and he was increasingly uneasy over the feeling that disloyalty had permeated the entire

German military organization even to the highest levels. Soviet advances sent his Eastern Front reeling, but because construction had been started in July on a new defense line stretching from East Prussia to the Carpathians, Hitler hoped that his forces would somehow hold. His main concern lay in the west, for he had long considered the west the vital sector of what had become, at least for the moment, a defensive war.

The breakthrough on the Western Front posed the ominous possibility that the Germans might have to withdraw from France. With France lost, the threat of Allied penetration of the German homeland would become immediate.

The Seine River, with its deep bends and twists, was difficult to defend and could be no more than a temporary rallying position, but between the Seine and the Rhine were a number of historic water obstacles where the Germans could hope to stop the Allies short of the German border. To utilize the water barriers, Jodl sketched a major defensive belt across Belgium and France (and into northern Italy) that consisted of two lines: the Somme–Marne–Saone River line, and the Albert Canal–Meuse River line, both anchored on the Vosges Mountains.

Behind these lines were the permanent fortifications of the West Wall

(Siegfried Line), protecting the approaches to the German border. Although neglected for four years and partially dismantled, the West Wall in the summer of 1944 was not a negligible defensive factor. Late in July Jodl ordered the West Wall repaired and rearmed and the river lines in France prepared for defense. The Todt Organization was to cease work on the Atlantic Wall and commence construction of defensive positions along the newly projected lines inland. Authority was granted to impress civilians for work on roads and defenses in Belgium and France.

In addition to the erection of defensive positions, Hitler enunciated on the last day of July a two-point policy directed against Allied logistics. He ordered his forces to deny the Allies ports of entry on the Continent and, if a withdrawal from France became necessary, to destroy the transportation system there by demolishing railroads, bridges, and communications.

Though withdrawal from France was extremely undesirable, Hitler foresaw the possible necessity of it. He indicated as much by ordering the movement of some units out of the Balkans and Italy for defense of the homeland, thereby accepting the probability of losing the Balkans immediately and the calculated risk of having to withdraw in Italy to the Alps. Hitler also quickened preparations for raising a reserve force within Germany.

Stabilizing the Normandy front appeared the only alternative to withdrawal from France. On the credit side, a front line in Normandy would be the shortest and most economical of any possible in the west. On the debit side, failure to stabilize the front in Normandy would—because of Allied air superiority—involve the German forces in mobile warfare under unfavorable conditions.

Reluctant to accept the hazards of mobile warfare in these circumstances and needing time to prepare rearward defenses, Hitler decided to take the risks and continue to fight in Normandy. Since the war in western Europe had reached a critical stage, he took responsibility for the battle upon himself. Creating a small staff taken from members of the OKW planning section (WFSt) to help him, Hitler sought to recreate the conditions of static warfare while at the same time preparing to withdraw in the event of failure. By this move, Hitler in effect assumed the functions of theater commander and filled the virtual vacuum in the chain of command that had existed since Rommel’s incapacitation and Kluge’s assumption of dual command of Army Group B and OB WEST. Ordering Kluge to close the gap in the left portion of the German defenses and to anchor the front on Avranches, Hitler forbade the commanders in the field to look backward toward defensive lines in the rear.

As seen by the staff of OB WEST, the situation in Normandy at the beginning of August, while critical, could have been worse.2 The recent appearance on the Continent of Canadian units and other formations that had been thought to belong to Patton’s army group, and the commitment in Normandy of ever-growing numbers of close-support planes indicated that a second large-scale Allied

strategic landing in western Europe was no longer likely. Also, the Allied breakout from the limited continental lodgment and the development of mobile warfare underscored the fact that the Allies no longer needed to make another landing. The knowledge that the Germans in Normandy already faced the bulk of the Allied forces in western Europe was somewhat of a relief.

Two possibilities seemed in order. The first was the more cautious: to break off the battle in Normandy and withdraw behind delaying action to the Seine while Army Group G evacuated southern France. This would have the virtue of saving the main body of German troops, though admittedly at the expense of heavy losses, especially in matériel. Eberbach later claimed that, when Warlimont visited the front about 1 August, he, Eberbach, suggested an immediate withdrawal to the Seine, a recommendation Warlimont rejected as being “politically unbearable and tactically impractical.”3

OB WEST could understand OKW’s reluctance to withdraw, for pulling back to the Seine would more than likely be the first step toward retirement behind the West Wall. If the Germans did not succeed in holding the relatively short front in Normandy, then only at the West Wall—another relatively short defensive line that could be reinforced—was there a prospect of success. The consequences of such a decision would be hard to accept—surrender of France with all the political and economic implications of it, loss of long-range projectile bases along the Pas-de-Calais, unfavorable reaction in Italy that might lead to the loss of a region valuable to the German war economy, withdrawals on other fronts to project the homeland.

The other alternative was to stabilize the front in Normandy. To do so, the breach at Avranches would have to be closed, a step that appeared tactically feasible at the beginning of August. If the gap were not closed, there would be an unavoidable crisis on the front, for the likelihood of being able to pull back across the Seine at that late date would be slim.

As events developed, Hitler left OB WEST no choice. He ordered the forces in the west to continue fighting in Normandy even as Kluge was already trying to remedy the situation at Avranches.

Although all of Kluge’s available forces in Normandy were committed by the first day of August, one armored and six infantry divisions were on the way to reinforce the front. The 84th and 85th Divisions were moving from the Pas-de-Calais toward Falaise. The 89th Division had just crossed the Seine River, and the 331st Division was in the process of being ferried across. Parts of the 363rd Division were already in the Seventh Army rear and were being committed in the LXXXIV Corps sector. From southern France came the 708th Division, which was crossing the Loire River near Angers, and the 9th Panzer Division, which was moving toward the Loire for eventual assembly near Alençon. Whether all would get to the front in time to be of use before the situation in the Avranches sector deteriorated completely was the vital question. It appeared that at least three divisions, the 363rd, the 84th, and the 89th, would be

available at Avranches during the first week in August.4 (Map IX )

Except at Avranches, the situation along the front was far from desperate. Eberbach’s Panzer Group West, which was to change its name on 5 August to the Fifth Panzer Army, was actively engaged only in one sector. The LXXXVI Corps, the I SS Panzer Corps, and the LXXIV Corps controlled quiet zones, as did the LVIII Panzer Corps headquarters, recently brought up from southern France. Only the II SS Panzer Corps was fighting hard by 2 August, having committed all three of its divisions against the British attack launched on 30 July south of Caumont toward the town of Vire.

Hausser’s Seventh Army front, on the other hand, was hard pressed. In a narrow sector just east of the Vire River, the II Parachute Corps had only the 3rd Parachute Division to defend the town of Vire. West of the Vire River to the Forêt de St. Sever, the XLVII Panzer Corps controlled the 2nd Panzer Division (which had absorbed the 352nd Division) and the 2nd SS Panzer Division (which had absorbed the remnants of Panzer Lehr and the 17th SS Panzer Grenadiers). On the left, LXXXIV Corps directed the 353rd Division and the 116th Panzer Division on a front from the St. Sever forest to the See River. Provisional units, formed from remnants and stragglers (including the 5th Parachute Division) and operating under the staff of the 275th Division, covered the gap south of the Sée River and east of Avranches, and the weak 91st Infantry Division was at Rennes.5

Since the Seventh Army (or any other outside ground headquarters) could not exercise effective command of the XXV Corps in Brittany, Kluge placed the corps directly under Army Group B as a matter of administration. Writing off the XXV Corps in this manner in accordance with Hitler’s orders emphasized the floating nature of the Normandy left flank. The weak forces at Rennes were obviously unable to offer sustained resistance. A large opening between the Sée and Loire Rivers invited American exploitation eastward toward the Paris-Orleans gap.6 To cover the gap thus exposed, Kluge on 2 August ordered the First Army to extend its control northward from the Biscay coast of France to the Loire River, take command of the forces along the Loire, and hold bridgeheads on the north bank at the crossing sites between Nantes and Orleans. On the same day Kluge also ordered the LXXXI Corps headquarters to hurry south from the coastal sector between the Seine and the Somme Rivers to take control of the arriving 708th Infantry and 9th Panzer Divisions on a refused Seventh Army left flank in the Domfront-Alençon sector.7 With these measures taken, Kluge turned his attention

to regaining Avranches as the new anchor point of the defensive line in Normandy.

If Avranches were to be regained, a counterattack had to be launched immediately. Where to get the troops for it was the problem, and Hitler provided the solution. On 2 August, in ordering a strong armored counterattack, Hitler authorized a slight withdrawal to a shorter line (Thury-Harcourt through the town of Vire to the western edge of the Forêt de St. Sever). A shortened front and the arrival of new units would give Kluge the means with which to counterattack to Avranches.8

Specifically, Hitler first thought of disengaging the II SS Panzer Corps (the 9th SS, the 10th SS, and the 21st Panzer Divisions) for the counterattack, but Kluge felt this impossible because of the British pressure south of Caumont. Kluge recommended that the XLVII Panzer Corps, which was nearer the critical sector, make the effort with the 2nd and 2nd SS Panzer Divisions reinforced at first by the LXXXIV Corps’ 116th Panzer Division and later by the incoming 9th Panzer Division (after the latter moved from Alençon to Sourdeval near Mortain). Since there was some question whether the 9th would arrive in Alençon in time to participate, Kluge suggested that additional armor be secured by pulling the 1st SS or the 12th SS Panzer Division out of the Caen sector where the British appeared to have become quiet, a risk that Eberbach had agreed to accept. Jodl approved Kluge’s proposals.9

This plan accepted, Kluge directed Hausser to launch an attack with the XLVII Panzer Corps, using the 2nd SS, the 2nd, and the 116th Panzer Divisions in an initial effort and the 1st SS Panzer Division as an exploiting force. The divisions were to be relieved from the line by 6 August through withdrawal to a shorter front.10

While the LXXIV and II SS Panzer Corps in the Panzer Group West sector prepared to withdraw during the night of 3 August in order to disengage the 1st SS Panzer Division, Hausser planned to disengage the other three divisions from his Seventh Army front by executing a three-phase withdrawal. The 2nd, 2nd SS, and 116th Panzer Divisions were to be pulled out of the line in that order on three successive nights starting 3 August and assembled in the area east of Mortain by 6 August. To make this possible, the II Parachute Corps was to extend its responsibility to the west to take control of a regiment of the 353rd Division, and the LXXXIV Corps was to integrate the arriving 363rd and 84th Divisions into its front. The XLVII Panzer Corps, which was to direct the attack, received the 275th as left flank cover. With three armored divisions moving abreast in an initial assault and a fourth ready to exploit initial success, the XLVII Panzer Corps commander, Funck, was to attack after dark on 6 August without artillery preparation.

General Haislip

His objective was to reach the Cotentin west coast and secure Avranches.11

Commitment of a Corps

While the Germans thus made their decision and laid their plans, the Americans, who were exploiting the Avranches gap, were also coming to a decision that was to alter the OVERLORD plan. The first move in the new direction of what was to be a profound change lay in the circumstances of the commitment of the XV Corps.

Commanded by Maj. Gen. Wade H. Haislip, a West Pointer who had fought in France during World War I and had recently been the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-1, on the War Department General Staff, the XV Corps headquarters had arrived on the Continent near the middle of July as a Third Army component. Because the single mission accorded the Third Army in early planning was securing Brittany and its ports, and because XV Corps was to become operational immediately upon commitment of the Third Army, it was expected that XV Corps would share the Brittany mission with VIII Corps. Yet the situation created by COBRA raised doubt as to the need of two corps in Brittany; thus the exact role of the XV Corps remained undefined except for projected commitment near Avranches.12 There was even doubt about the divisions the corps would control. Though the 4th Armored Division had been tentatively assigned to XV Corps, it was well employed as part of VIII Corps. To give XV Corps an armored force, Patton promised that if the 4th could not be made available, the recently arrived and assembled 5th Armored Division would be assigned. Because the 35th and 5th Infantry Divisions, also slated to come under the XV Corps, were in the V Corps sector, far from Avranches, it seemed more convenient to use the 83rd and 90th Divisions, which had been pinched out near Périers. Trying to be ready for any eventuality, General Haislip alerted the 83rd and 90th Division commanders to their possible assignment to the corps while at the same time keeping a close check on

General Eddy

the 4th Armored “so that intelligent orders for it to side-slip into [the] zone of XV Corps” could be issued promptly. On 1 August Haislip learned that he was to control the 5th Armored, 83rd, and 90th Divisions, but this too was to be changed.13

Where the XV Corps was to be employed was also somewhat a matter of conjecture. Early plans had projected a XV Corps advance along the north shore of Brittany, but at the end of July a zone on the left of VIII Corps seemed more probable. Since the immediate Third Army objective was the Rennes-Fougères area, it was reasonable to expect the XV Corps to be directed on Fougères as a preliminary for a subsequent advance to the southwest toward Quiberon. Early on 1 August, General Haislip learned that “the projected operation of the Corps toward the southwest had been cancelled, and that [a] new operation would be [started] towards the southeast.”14

The reason for the change lay in the constriction and vulnerability of the Avranches bottleneck. To prevent German interference with American troop passage, a protective barrier was necessary. To ameliorate traffic congestion, a wider corridor was desirable. To attain these ends became the first combat mission of XV Corps, and to achieve

it the corps was to enter the gap between the diverging VIII and VII Corps. On 1 August the VIII Corps left flank extended almost to Rennes, while the VII Corps right flank reached for Brécey and beyond. Although the distance between Rennes and Brécey provided more than adequate room for the new corps, the few miles between Avranches and Brécey presented a problem. The approach march in particular was bound to be difficult, for units of XV Corps would have to pass through the already congested rear areas of the two adjacent corps.15

Although General Haislip wanted to move his armored component to the fore immediately in order to exploit German disorganization, traffic congestion was so bad that after two days the 5th Armored Division was still north of the Sée River.

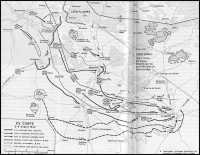

Map 12: XV Corps, 2–8 August 1944

There, the armor was temporarily halted to conform with new instructions from the army group commander, General Bradley.16 Fortunately, the 90th Division was able to take over the first corps assignment of moving to Avranches and eastward to take blocking positions between the Sée and the Sélune Rivers.17 (Map 12)

The 90th Division’s reputation at the beginning of August was still somewhat blemished. The division’s part in the battle of the hedgerows during July had done little to alter the general impression that the 90th was far from being combat effective, and there had been talk of breaking it up to provide replacements for other units.18 However, under a new commander, Brig. Gen. Raymond S. McLain, the 90th was to have another chance to make good.

General McLain’s first mission was to capture St. Hilaire-du-Harcouët, a town on the Sélune River not quite fifteen air miles southeast of Avranches. Possession of a Sélune River bridgehead at St. Hilaire would widen the Avranches corridor and establish an anchor point for blocking positions east of the coastal bottleneck. With St. Hilaire in hand, McLain was to set up a defensive line north to the Sée River to block enemy movement westward between the Sée and the Sélune.19

A task force under the command of Lt. Col. George B. Randolph was to screen the movement of a larger force under Lt. Col. Christian E. Clarke, Jr., that was to spearhead the division advance.20 The leading units began to move an hour before midnight, 1 August. Although traffic was heavy and the troops had a “tough time” moving during darkness, Task Force Randolph swept aside a small number of enemy rear guards and on the morning of 2 August reached St. Hilaire. The main bridge was still intact. When Task Force Clarke arrived, the artillery took defiladed positions, other support units built up a base of fire, and an infantry skirmish line followed by light tanks charged across several hundred yards of open ground and crossed the bridge in the face of enemy shelling. The troops quickly eliminated the halfhearted resistance in the town. So rapid and aggressive had the assault been that casualties were few. With St. Hilaire in hand, General McLain brought the remainder of the 90th Division forward to a line north of the town in order to establish contact with the VII Corps at Juvigny, thus erecting a barrier against German attack from the east.21 The performance of the division at St. Hilaire was far different from that in the Cotentin and augured well.

As the 90th Division consolidated in the area east of Avranches, General McLain received an order from General Haislip to extend his defensive line seven miles from St. Hilaire south toward Fougères to the village of Louvigné-du-Désert. In compliance, Task Forces Randolph and Clarke occupied Louvigné shortly after midnight, 2 August.22 By this advance, the XV Corps adequately covered the VII Corps right flank.

Though the VII Corps right flank was thus protected by the advance of the XV Corps, the VIII Corps—then making the main American effort—had its left flank open between Louvigné and Rennes, a 35-mile gap covered only by patrols of the 106th Cavalry Group.23 To remedy the situation, General Patton, just before noon on 2 August, ordered General Haislip to move the 5th Armored Division south to Fougères, the hub of an important road network. To Haislip, Patton’s order not only pertained to flank protection for the VIII Corps but also indicated that XV Corps was about to embark on a campaign of exploitation.24

As events developed, Haislip was in for disappointment. About the same time that Patton decided to cover the exposed VIII Corps flank, General Bradley, the army group commander, was visiting General Middleton’s command post. Also concerned about the corps flank, Bradley and Middleton decided to send a strong force to Fougères at once.

The only unit immediately available for this mission was the 79th Division, whose leading regiment was already at Pontorson on a projected move to follow the 6th Armored Division westward to Brest. Reversing the direction of the 79th Division “pursuant to instructions of army group commander,” Middleton ordered occupation of Fougères before dark, 2 August, and establishment of contact with the 90th Division at Louvigné-du-Désert.25 It was this set of instructions from General Bradley that prompted the halt of the 5th Armored Division north of the Sée River.26

Patton had acted simultaneously with Bradley to close the gap, the difference being the choice of the unit. Sending the 79th instead of the 5th Armored brought quicker action at Fougères and lessened traffic congestion around Avranches, but it also temporarily brought some complications to both the VIII and the XV Corps. The 79th Division replaced the 83rd on the corps troop list, and the immediate result was some confusion: the XV Corps headquarters had “no wire to either division—90th Inf Div has no wire to anybody—79th Inf Div seems to have wire (only) to VII Corps”; and the 83rd Division for a short time was simultaneously attached to two corps—VIII and XV—that were going in opposite directions.27 Yet the shift was made with relative ease, primarily because uniformity of training and of staff procedures throughout the U.S. Army gave units flexibility. Throughout the campaign a brief telephone call was enough to set into motion an apparently complicated change.

To secure Fougères, reconnaissance troops of the 79th Division moved on the heels of a 106th Cavalry Group patrol into the town. The division occupied Fougères in force on the morning of 3 August and established contact with the 90th Division on the north.28 As the 106th Cavalry Group (assigned to the XV Corps) continued to screen the area between Fougères and Rennes, apprehension over the VIII Corps left flank vanished.29 The VIII Corps drove westward into Brittany, but the XV Corps, in contrast with earlier OVERLORD plans, faced to the southeast.

The orientation of XV Corps to the southeast reflected the reaction of the American high command to the changed situation brought about by the breakout. The 90th Division on the left and the 79th on the right held a defensive line from Juvigny to Fougères, facing away from Brittany, while the 5th Armored Division prepared to move south through Avranches toward the corps right flank.30 In a sense, it was a fortuitous deployment that was to prove fortunate. For as the corps reached these positions, thinking on the higher echelons of command crystallized. The result altered a basic concept of the OVERLORD planning.

OVERLORD Modified

In the midst of the fast-moving post-COBRA period, the utter disorganization of forces on the German left flank contrasted sharply with unexpected firmness in other parts of the German line. To exploit the collapse on the German left and to deal with continuing tenacity elsewhere, the Allied command seized upon the southeastern orientation of the XV Corps.

In the post-COBRA exploitation during the last days of July, when General Bradley had directed XIX Corps to advance along an axis projected through Tessy, Vire, and Domfront to Mayenne, Bradley thought the XV Corps might advance toward the upper reaches of the Sélune River, pinch out the VII Corps at Mortain, and meet the XIX Corps at Mayenne.31 Unfortunately, XIX Corps had not gotten much beyond Tessy by 3 August. In contrast, XV Corps had met no “cohesive enemy front” in moving to the St. Hilaire-au-Harcouët-Fougères-Rennes line, and the 79th Division reported no enemy contact at all at Fougères.32 To exploit this contrasting situation was tempting.

Pre-invasion OVERLORD and NEPTUNE planners had expected the early Allied effort to be directed toward Brittany unless the Germans had decided to withdraw from France or were at the point of collapse, and actual operations during June and July had conformed to this concept. Since the Germans appeared on the verge of disintegration at the beginning of August, the Allies began to consider the bolder choice offered by the planners: an immediate eastward drive toward the principal Seine ports of Le Havre and Rouen.33

The NEPTUNE planners had visualized the Allied right in Normandy making a wide sweep south of the bocage country, and as early as 10 July General Montgomery had suggested a maneuver of this kind eastward toward the successive lines Laval-Mayenne and le Mans-Alençon. Several days before COBRA and again several days after COBRA, Montgomery had reiterated this concept: he wanted the First U.S. Army to wheel eastward while the Third Army was occupied with operations in Brittany.34

During the latter days of July, when 21 Army Group planners considered in detail the bountiful advantages that might accrue from capture of Avranches, they were impressed by three opportunities that seemed immediately and simultaneously feasible: seize the Breton ports, destroy the German Seventh Army west of the Seine River, and cross the Seine before the enemy could organize the water line for defense. Thus assuming that the ground forces were about to fulfill the objectives of the OVERLORD plan, the Allies began to think seriously of post-OVERLORD operations directed toward the heart of Germany.

Occupying the OVERLORD lodgment area had always implied possession of

the Breton ports, one of the most vital strategic objectives of the OVERLORD plan, before winter weather precluded further use of the invasion beaches. Now the planners were confident that a small force, one American corps of perhaps an armored division and three infantry divisions, “might take about a month to complete the conquest.” The remainder of the Allied forces could turn to the other, more profitable opportunities: “round up” the Germans west of the Seine, drive them against the river, destroy them within the limits of the lodgment area, and, by seeking such distant objectives as Paris and Orléans, prepare to cross the Seine River.35

These speculations slighted a fundamental factor that had governed OVERLORD planning until that time: the belief that the Allies needed the Breton ports before they could move outside the confines of the lodgment area. Montgomery’s planners had weighed the logistical merits of gaining Brittany against the tactical opportunities created by COBRA and by arguing for the latter presented a radically different conclusion. Until that moment the importance of the Breton ports could hardly have been exaggerated, for the very success of OVERLORD had seemed predicated on organizing Brittany as the principal American base of operations.36

General Eisenhower reflected the changing attitude toward the question of Brittany on 2 August. He believed that “within the next two or three days” Bradley would “so manhandle the western flank of the enemy’s forces” that the Allies would create “virtually an open [enemy] flank,” and he predicted that the Allies would then be able to exercise almost complete freedom in selecting the next move. He would then “consider it unnecessary to detach any large forces for the conquest of Brittany,” and would instead “devote the greater bulk of the forces to the task of completing the destruction of the German Army, at least that portion west of the Orne, and exploiting beyond that as far as [possible].” He did not mean to write off the need for the Breton ports, but securing both objectives simultaneously, he believed, would now be practical.37

On the same day, 2 August, General Bradley was still thinking along the lines of the original OVERLORD plan. Patton’s forces then entering Brittany were still executing the American main effort, and the entire Third Army was eventually to be committed there to secure the ports. The St. Hilaire-du-Harcouët-Fougères—Rennes line, in the process of being established by the XV Corps, was no more than a shield to prevent interference with the Third Army conquest of the Brittany peninsula.38 On the following day, 3 August, Bradley changed the entire course of the campaign by announcing that Patton was to clear Brittany with “a minimum of forces”; the primary American mission was to go to the forces in Normandy who were to drive eastward and expand the continental lodgment area.39 Brittany had

become a minor prize worth the expense of only one corps. “I have turned only one American Corps westward into Brittany,” General Montgomery stated on the following day, “as I feel that will be enough.”40 Had logistical planners not insisted that the ports were still needed, even fewer forces might have been committed there.41 Several days later, when heavy resistance had been discovered at the port cities, Montgomery resisted “considerable pressure” to send more troops “into the peninsula to get the ports cleaned up quickly,” for he felt that “the main business lies to the East.”42

The new broad Allied strategy that had emerged concentrated on the possibility of swinging the Allied right flank around toward Paris. The sweeping turn would force the Germans back against the lower reaches of the Seine River, where all the bridges had been destroyed by air bombardment. Pushed against the river and unable to cross with sufficient speed to escape, the Germans west of the Seine would face potential destruction.43

Because the XV Corps was already around the German left and oriented generally eastward, General Haislip drew the assignment of initiating the sweep of the Allied right flank. The remaining problem was to resolve from somewhat conflicting orders the exact direction in which Haislip was to move-south, southeast, or east.44

“Don’t Be Surprised”

Exclusive of Brittany, the mission outlined for the Third Army by General Bradley on 3 August had both offensive and defensive implications. General Patton was to secure a sixty-mile stretch of the north-south Mayenne River between Mayenne and Château-Gontier and to seize bridgeheads across the river. He also was to protect his right flank along the Loire River west of Angers, part of the southern flank of the OVERLORD lodgment area.45

Because this task was too great for the XV Corps alone, General Patton brought in the XX Corps to secure the Mayenne River south of Château-Gontier and to protect the Loire River flank. While the XV Corps was to drive about thirty miles southeast to the water line between Mayenne and Château-Gontier, the XX Corps was to move south toward the Loire. Although Patton assigned no further objectives, he was thinking of an eventual Third Army advance forty-five miles beyond Laval to le Mans—to the east. When, by which unit, and how this was to be done he did not say, but the obvious presumption that the XV Corps would continue eastward beyond the Mayenne River was not necessarily correct. “Don’t be surprised,”

Patton told Haislip, if orders were issued for movement to the northeast or even to the north.46 The implication was clear. Patton had sniffed the opportunity to encircle the Germans west of the Seine River, and he apparently liked what he smelled.

General Haislip planned to use the 106th Cavalry Group to screen the advance of the 90th Division from St. Hilaire to Mayenne and that of the 79th Division from Fougères to Laval. While the infantry divisions secured bridgeheads across the Mayenne River, the 5th Armored Division was to move south and southeast from Avranches and extend the corps front to Château-Gontier. French Resistance groups near Mayenne and Laval, numbering about 2,500 organized members, were to help by harassing the German garrisons. If the American troops met pockets of resistance, they were to go around them. “Don’t stop,” Patton ordered.

Sweeping through enemy territory for thirty miles and crossing a river that was a serious military obstacle was an ambitious program. The Mayenne was a steep-banked stream about one hundred feet wide and five feet deep. All the bridges except one at the town of Mayenne had been destroyed. Enemy interference was conjectural. “Nobody knows anything about the enemy,” the corps G-2 stated, “because nothing can be found out about them.”47

Air reconnaissance helped little. The reports of air reconnaissance missions filtered down to corps level too late to be of assistance. “Each day we would get a thick book from the air force,” General Haislip recalled long afterwards, “and we would have to try to figure out what if anything in it applied to our little spot on the map. By the time we could figure it out, we were far away from there.”48

Nothing could be found out about the Germans because there were hardly any Germans left. Only weak rear-echelon guard and supply detachments garrisoned Mayenne and Laval. Even though a captured American field order led the German command to expect the main American thrust to be made westward into Brittany, not eastward toward Laval and le Mans, the Germans considered that the lack of combat troops in the Laval-le Mans region still had to be remedied. The LXXXI Corps headquarters was moving from the Seine-Somme sector to assume responsibility for Laval and le Mans, and the 708th Infantry and the 9th Panzer Divisions were moving north from southern France. Because neither the corps headquarters nor the divisions had yet arrived (the leading units of the 708th were across the Loire near Angers on 3 August), the Seventh Army operations officer was dispatched to the army rear command post at le Mans to organize a defense of the Mayenne-Loire area and to accelerate the movement of the arriving forces. Laval in particular was important, for its loss would threaten le Mans and Alençon, where vital German communications and supply centers were located. The army operations officer collected

the troops he could find—remnants, stragglers, supply personnel—and as his first measure reinforced a two-battalion security regiment performing guard duty and a flak battalion with 88-mm. guns emplaced at Laval. Despite the fact that Laval could then be considered relatively strongly held, alarming reports of troop instability and the increasing possibility of an American thrust to the east led to frantic but generally unsuccessful efforts to speed up the commitment of the incoming divisions in the Mayenne-Alençon area.49 These forces were not in position when the XV U.S. Corps launched its attack on 5 August.

On the XV Corps left, General McLain entrusted the 90th Division advance to Mayenne to a task force under the assistant division commander, Brig. Gen. William G. Weaver.50 Proving that facile capture of St. Hilaire had been no fluke, Weaver’s force reduced several roadblocks, overran or bypassed pockets of resistance, and covered the thirty miles to the west bank of the Mayenne River in less than half a day, before noon of 5 August. Finding the highway bridge leading into the town of Mayenne still intact, but discovering also that the arrival of American troops had stirred up frenzied defensive activity, Weaver dispatched two infantry battalions to outflank the town on the south. No sooner had he done so than he became impatient and ordered the remainder of his task force to make a frontal assault by way of the bridge. The frontal attack succeeded, and even before the outflanking force had arrived in position, Mayenne had fallen. Although the Germans had mined the bridge, the 90th Division attack had forestalled demolition. While Task Force Weaver occupied Mayenne, the remainder of the division moved forward from St. Hilaire on a broader front to the Mayenne River, where engineers constructed additional bridges.51

To capture Laval, General Wyche built a 79th Division task force around Colonel Wood’s motorized 313th Infantry and sent it along the main Fougères-Laval highway, which had previously been reconnoitered by a squadron of the 106th Cavalry Group.52 Half way to Laval, a strong roadblock halted progress for about two hours while the leading units reduced the resistance and captured about fifty prisoners and several field guns. Additional roadblocks held up the task force briefly, and it was midnight of 5 August before American troops reached a point about two miles northwest of Laval. During the night of 5–6 August, while the remainder of the 79th Division moved forward from Fougères, patrols discovered that the German garrison had thoroughly destroyed the Mayenne River bridges but had evacuated Laval. On the following

morning, against no opposition, the division crossed the river and entered Laval in force—one infantry battalion being led across a dam by French policemen, two battalions crossing the river on an engineer footbridge, another paddling across on rafts and in boats found along the west bank, and two battalions being ferried across by engineers who had rushed up assault boats. A treadway bridge spanned the river shortly after midnight, and a floating Bailey bridge was opened to traffic at noon, 7 August.53

Even before the capture of Laval, it had become obvious that only insignificant and disorganized forces opposed the XV Corps.54 As soon as Mayenne fell on 5 August, Patton received permission to send the corps on to le Mans. The corps axis of advance thus changed from the southeast to the east.55 Emphasizing that action during the next few days might be decisive for the entire campaign in western Europe, Haislip urged his commanders “to push all personnel to the limit of human endurance.”56 This was not idle talk, for the corps had a large order to fill. To take le Mans the corps, with both flanks open, would have to advance across forty-five miles of highly defensible terrain, cross a major military obstacle in the form of the Sarthe River, and capture a city of 75,000 population that the Germans presumably not only intended to defend but also had had ample time to fortify.57

The presumption was not altogether wrong. By this time the reconnaissance battalion of the 9th Panzer Division and parts of the leading regiment of the 708th Infantry Division had reached the vicinity of le Mans. Instead of holding these units and allowing the remaining portions of both divisions to assemble, the LXXXI Corps committed the small forces at once. The premature and, in the opinion of the Germans, disgraceful capitulation at Laval made necessary the immediate evacuation of administrative personnel from le Mans, long the location of the Seventh Army headquarters. With Laval lost, the Germans had to expect an American thrust along the Laval-le Mans highway and a subsequent threat to Seventh Army and Army Group B rear installations and supply dumps. Hastily trying to build up a front to deny the important center of le Mans, the LXXXI Corps dispatched units of the 708th Division (arriving on foot and with horse-drawn vehicles) and the 9th Panzer Division reconnaissance battalion west toward the Mayenne River line as soon as they arrived. These advance components were to collide with American columns near Aron and Evron in true meeting engagements.58

Since the 79th Division was still in the process of seizing Laval, the task of initiating the XV Corps attack to le Mans devolved upon the 90th. Accorded use of the main Laval—le Mans highway, General McLain planned to move the bulk of the division southeast from Mayenne to the highway, then eastward to le Mans behind Task Force Weaver, which was to drive along a

more direct route southeast from Mayenne to the objective.59 General Weaver, again in command of the division spearhead, divided his force into two columns for an advance over parallel roads. One column, under his personal command, was to proceed on the left through the towns of Aron and Evron.60 The other column, commanded by Colonel Barth, was to move through Montsûrs, Ste. Suzanne, and Bernay.61

Barth’s column on the right encountered only slight opposition on 6 August in moving southeast from Mayenne about twelve miles to Montsûrs, then turning east and proceeding ten miles farther to the hamlet of Ste. Suzanne. There, that evening, the column struck determined opposition and halted.

In contrast with the excellent advance of Barth’s force, Weaver’s column had hardly departed Mayenne before meeting a strong German armored and infantry force at Aron. Engaging the enemy in a fire fight that lasted all day, Weaver’s troops were unable to advance.

Meanwhile, the remainder of the 90th Division was approaching or crossing the Mayenne River in two regimental columns—the 358th (Colonel Clarke) on the left and the 359th (under Col. Robert L. Bacon) on the right.

Checked at Aron, Weaver on the morning of 7 August left contingents of the 106th Cavalry Group to contain the enemy in the Aron-Evron sector and to protect the division and corps left flank, reversed the direction of his column, and followed Barth’s route of the previous day as far as Montsûrs. Instead of turning eastward at Montsûrs, Weaver continued to the south. Clarke’s 358th Infantry, approaching Montsûrs in column from the west, waited for Weaver to clear the village before proceeding eastward toward Ste. Suzanne in support of Barth.

Weaver, moving south, reached the village of Vaiges on the main Laval—le Mans highway. There he intended to turn east to parallel Barth’s movement, not on Barth’s left as originally planned, but on his right. Weaver had to change his plan when he discovered that Bacon’s 359th Infantry had already entered Vaiges from the west and was proceeding along the Laval—le Mans highway toward the division objective, clearing opposition that had formed around roadblocks.

Refusing to be shut out of the action, but unwilling to risk traffic congestion likely if his and Bacon’s troops became intermingled, Weaver led his column northeast from Vaiges, aiming to insert his column between Barth’s and Clarke’s on the north and Bacon’s on the south. He would thus add a third column to the eastward drive toward le Mans. Several miles northeast of Vaiges, however, at the hamlet of Chammes between Vaiges and Ste. Suzanne, Weaver again was thwarted, this time by the same enemy force opposing Barth at Ste. Suzanne.

Barth, in the meantime, had sustained and repelled a tank-supported counterattack launched from St. Suzanne. American artillery fire effectively stopped

the Germans, but in wooded terrain south of the Ste. Suzanne-Bernay road the enemy continued to resist. Soon after Weaver’s arrival, however, the opposition slackened.

As enemy fires diminished and American artillery shelled the Germans, Barth rushed his motorized column past the wooded area southeast of Ste. Suzanne, passed through Bernay that night without stopping, and on the morning of 8 August struck an enemy defensive position only a few miles west of le Mans. Weaver left a small containing force at Chammes, moved south to the Laval—le Mans highway, turned east, passed through Bacon’s troops, and slammed down the road, reducing small roadblocks at virtually every hamlet. Early on 8 August, Weaver, too, was only a few miles from le Mans.

As Barth and Weaver swept by the German forces in the forest southeast of Ste. Suzanne, Clarke on the north and Bacon on the south mopped up demoralized remnants and stragglers. Although the Americans had judged that only minor enemy forces had been present in the Evron area, the 90th Division took 1,200 prisoners and destroyed in large part the reconnaissance battalion of the 9th Panzer Division and a regiment of the 708th Division. The success of the approach march to le Mans was attributable in great measure to the aggressive persistence of General Weaver, who had not permitted his troops to be pinned down by opposition. The result left no doubt that the same 90th Division that had stumbled in the Cotentin was now a hard-hitting outfit.62

With both columns several miles west of le Mans by 8 August, General McLain halted the advance, terminated the task force organization, and prepared to attack the city. That night Clarke’s 358th Infantry crossed the Sarthe River north of le Mans to cut the northern exits of the city. On the morning of 9 August, after shelling a German force observed escaping to the east and capturing fifty prisoners, the troops moved into the northern outskirts of the city. Barth’s 357th Infantry also crossed the river during the night of 8 August, entering le Mans on the following morning.63 Troops of the 90th Division made contact with part of the 79th Division, which had secured its portion of le Mans on the previous afternoon.

The 79th Division had started its drive east from Laval on the morning of 7 August as 106th Cavalry troops and Colonel Wood’s motorized and reinforced 313th Infantry moved through the area immediately south of the main Laval-le Mans highway. Clearing small groups of Germans, the task force advanced more than half the distance to the objective. To give the attack added impetus on 8 August, General Wyche motorized Lt. Col. John A. McAleer’s 315th Infantry and passed it through the 313th. The new spearhead unit surged forward, dispersing sporadic resistance, and the leading troops detrucked on the southwest outskirts of le Mans that afternoon. Concluding an outstanding exploitation effort, troops of the 79th Division

crossed the Sarthe River and reached the center of le Mans, by 1700 on 8 August.64 The Seventh Army headquarters troops were gone.

The 5th Armored Division had also had a hand in the advance. Commanded by Maj. Gen. Lunsford E. Oliver, the 5th Armored Division on 6 August had moved south against light resistance past Avranches and through Fougères and Vitré. At the village of Craon, opposition at a destroyed bridge temporarily halted a combat command, but quick deployment dispersed the Germans and aggressive reconnaissance secured a bypass crossing site. By evening the division was at the Mayenne River at Château-Gontier on the corps right flank. There, the division faced the serious problem of how to cross the river in the face of an acute shortage of gasoline.

Several days earlier, on 4 August, General Haislip, the corps commander, had directed the 5th Armored Division to unload fuel and lubricants from a hundred of its organic trucks so that the trucks might be used to motorize the two infantry divisions. Although Haislip had intended to return the vehicles before committing the armor, he had been compelled instead to replace them with a corps Quartermaster truck company on the night of 5 August. The division commander, General Oliver, instructed the truck company to draw gasoline at any army Class III truckhead north of Avranches and to join the armored division south of Avranches on the following morning. When the trucks failed to appear, Oliver sent an officer back to locate them. The officer found the Quartermaster company and had the trucks loaded, but traffic congestion prevented the vehicles from getting to the division that day. Not until the early morning hours of 7 August did they arrive. Uncertain whether the Third Army could establish and maintain supply points at reasonable distances behind armored forces in deep exploitation and unwilling to risk a recurrence of the gasoline shortage, Oliver provided the division with an operational fuel reserve by attaching a platoon of the Quartermaster company to each combat command.

General Oliver need not have worried. The organic trucks of the division were released by the infantry and returned to the 5th Armored area early on 7 August. At the same time, the Third Army moved 100,000 gallons of gasoline to Cossé-le-Vivien, several miles south of Laval, whence 5th Armored Division trucks transported it across the Mayenne River to Villiers-Charlemagne. Here the division quartermaster established a Class III dump. A platoon of the division Engineer battalion protected the supply point until the division civil affairs section obtained sufficient numbers of the FFI for guard duty.

Gassed up on the morning of 7 August, the 5th Armored Division crossed the Mayenne River after eliminating the Château-Gontier garrison (about a company strong), repairing the damaged bridge there, and constructing several bridges south of Château-Gontier. General Haislip had instructed General Oliver to advance on le Mans echeloned to the right rear of the 79th Division, but had also authorized him to use all possible routes in the corps zone, providing he did not interfere with the infantry

divisions. If the infantry encountered opposition strong enough to retard progress seriously, the armor was to move to the head of the corps attack. This was not necessary. The 5th Armored Division reached the Sarthe River south of le Mans on the evening of 7 August and crossed during the night. Sweeping through some opposition on 8 August, the armor bypassed le Mans on the south, swung in a wide arc, and moved around the eastern outskirts of the city. By midnight of 8 August, the converging attacks of the three divisions had closed all exits from le Mans and infantrymen were clearing the streets of the city.65

In four days, from 5 to 9 August, General Haislip’s XV Corps had moved about seventy-five miles—from the St. Hilaire-Fougères line to le Mans—an extraordinarily aggressive advance at little cost. Extremely light casualties contrasted well with a total of several thousand prisoners.66 The immediately apparent achievement of Haislip’s exploitation was that the XV Corps had frustrated German plans to organize strong defenses at Laval and le Mans. But soon an even more spectacular result would become obvious.

During the first week of August the Third Army headquarters had been serving two bodies with one head. Two distinct fronts had been advancing in opposite directions, moving ever farther apart. By 8 August more than two hundred miles separated the 6th Armored Division of the VIII Corps at the gates of Brest and the XV Corps at le Mans.

Less than one hundred miles east of le Mans lay the final 12th Army Group objective designated by the OVERLORD plan, the eastern edge of the OVERLORD lodgment area, an area roughly between Paris and Orléans. With le Mans occupied so easily there seemed to be few German forces to restrain further Third Army advance toward its part of the objective, the Paris-Orléans gap. Yet, this advance was not to be, for the moment at least; a new goal appeared more desirable.

The XV Corps advance to le Mans had in one week moved an enveloping right flank eighty-five air miles southeast of Avranches and was well on its way to outflanking the German armies west of the Seine River, or had already done so. If the basic purpose of military operations was to close on advantageous terms with the enemy and destroy him, and if a favorable moment for a move of this kind appeared, purely geographical objectives receded in importance. The opportunity for a decisive victory seemed doubly propitious, for the Germans in making a bid to regain the initiative in the battle of France had played into American hands.

General Bradley was ready to act, and in his new decision the XV Corps had an important role. “Don’t be surprised,” Patton had earlier warned Haislip. Instead of going farther east from le Mans, the XV Corps turned north toward Alençon.