Chapter 29: The Liberation of Paris

Allied Plans

As American troops neared Paris, soldiers recalled the “fanciful tales of their fathers in the AEF” and began to dream of entering the city themselves.1 Despite their hopes, despite the political, psychological, and military significance of the city, and even though any one of three corps had been capable of liberating Paris since mid-August, the Allied command had long before decided to defer liberation on the basis of tactics, logistics, and politics.

Before the cross-Channel attack, Allied planners had thought it likely that the Germans would hold on firmly to Paris. With two potential switch lines in the Marne and Oise Rivers, the Germans would possess not only favorable defensive positions but also a most suitable base for a counteroffensive. To attack Paris directly would therefore probably involve the Allies in prolonged street fighting, undesirable both because of the delay imposed on operations toward Germany and because of the possibility of destroying the French capital. Yet the Allies would need to reduce the German defenses at Paris before they could initiate action beyond the Seine River. The best way to take the capital, the planners indicated, would be to by-pass and encircle it, then await the inevitable capitulation of the isolated garrison.2

Staff officers responsible for supply favored this course. Because the Combined Chiefs of Staff had advised the Supreme Commander that he was to distribute relief supplies to liberated areas if he could do so “without hindrance ... to the logistical administrative support required to sustain the forces allocated ... for the defeat of Germany,” the logisticians saw Paris in terms of a liability. The Allied civil affairs commitment there could not help but drain supplies from the combat units and adversely affect military operations.3

The civil affairs commitment seemed particularly large in August because Allied bombing and French sabotage directed against German transport had virtually isolated the capital from the provinces. A famine of food, coal, gas, and electricity threatened the city. Planners estimated that four thousand tons of supplies per day would be required, which, if converted to gasoline

for the combat troops, was “enough for a three days’ motor march toward the German border.” In view of the disintegration of the German forces in Normandy, which invited immediate Allied pursuit operations toward Germany, the necessity of diverting troops and supplies to Paris on humanitarian grounds, though difficult to reject, seemed unwarranted, particularly since the military supply lines were already strained and since continued military pressure east of Paris might bring the war to a quick end. The Allies felt that the Germans in Paris could only delay the Allied advance, and because the Allies would soon have other crossing sites over the Seine, an unnecessary challenge might provoke the Germans into destroying the city.4

The political factor working against immediate liberation stemmed from the aspirations of General Charles de Gaulle, chief of the Free French movement. Though Marshal Henri Pétain headed the government in France, de Gaulle several days before the invasion had proclaimed his own National Committee of Liberation the provisional government of the French Republic. By making possible de Gaulle’s entry into Paris and thus unavoidably intervening in the internal affairs of France, General Eisenhower “foresaw possible embarrassment.”

The result might be the imposition of a government on France that the French people might not want.5

These logistical and political factors played a part in the Allied decision to postpone the liberation, despite recognition that “Paris will be tempting bait, and for political and morale reasons strong pressure will doubtless be exerted to capture it early.”6 The circumstances were such as to give full play to the desire to spare Paris and its two million inhabitants devastation and injury. Ever since the preliminary phases of Operation OVERLORD when Allied planes had attempted to destroy the German communications network in France, pilots had attacked railroad marshaling yards outside Paris rather than terminals inside the city, and in August the same motivation applied in the decision to swing ground troops around the capital rather than through it.

German Hopes

The German high command had long had “grave worries” that loss of Paris to the Allies would publicize the extent of the German reverses. Because of this and because of Hitler’s tactical plans, the Germans decided at the beginning of August to hold the French capital.7

At the same time that Hitler had conceived the Mortain counterattack, he had had to consider seriously the possible eventuality of withdrawing his forces from Normandy, perhaps from

France. To cover the withdrawal, OKW on 2 August ordered General der Flieger Karl Kitzinger, Military Governor of France, to construct and organize defensive positions along the line of the Somme, Marne, and Saône Rivers, to which the forces then in Normandy would retire. To insure a successful withdrawal to the Seine and Marne, Hitler directed OKH to establish a special command at Paris under Army Group B, and on 7 August he appointed Choltitz, former commander of the LXXXIV Corps in the Cotentin, Commanding General and Military Commander of Greater Paris.8

Choltitz’s mission at first was to make Paris “the terror of all who are not honest helpers and servants of the front.”9 He was to inactivate or evacuate all superfluous military services in Paris, dispatch all rear-area personnel able to bear arms to front-line units, restore discipline among troops accustomed to easy living, and maintain order among the civilian population. Several days later Choltitz received the prerogatives of a fortress commander—unqualified command of the troops of all services in the area and full authority over the civilian inhabitants. Paris was to be defended to the last man. All the seventy-odd bridges within the city limits were to be prepared for demolition. The troops were to battle outside the city as well as inside in order to block the Allies at the Seine.10

Choltitz’s predecessor in Paris, Generalleutnant Hans Freiherr von Boineburg-Lengsfeld, whose mission had been merely to maintain “peace and order,” had on his own initiative constructed an “obstacle line” west and southwest of Paris, which he felt could be defended successfully with the troops at his disposal. He believed that fighting inside Paris would be an act of complete irresponsibility because of the almost certain destruction of irreplaceable art treasures. He judged that his forces—twenty-five to thirty thousand men of the 325th Security Division, armed with light infantry weapons for guard duty—would be able to delay the Allies outside the city and west of the Seine. Just before Choltitz’ arrival, antiaircraft and security elements occupied these positions to block the main highway approaches to the capital.11

The forces west and southwest of Paris soon grew in strength in response to Hitler’s desire for additional antitank weapons west of the Seine. Antitank companies from units in the Army Group G sector and from the 6th Parachute and 48th and 338th Infantry Divisions (all of which were soon to become at least partially involved in the defense of Paris) were to move to the Paris-Orléans gap, screen the capital, and knock out American reconnaissance columns and armored spearheads that were moving eastward from le Mans. Col. Hermann Oehmichen, an antitank expert, arrived from Germany to teach local units the technique of antitank

protection. With him he brought a cadre of instructors trained, in antitank defense and demolition, a reconnaissance battalion, a column of light trucks, and a supply of Panzerfausts. Although Oehmichen’s program was not completed in time to halt the American drive toward the Paris-Orléans gap, some of his antitank elements reinforced the Paris defenses.12

By 16 August the defenses west of Paris included twenty batteries of 88-mm. antiaircraft guns, security troops of the 325th Division, provisional units consisting of surplus personnel from all branches of the Wehrmacht, and stragglers from Normandy. The remnants of the 352nd Division were soon to join them. These troops, all together numbering about 20,000 men, were neither of high quality nor well balanced for combat. Upon the approach of American forces, Choltitz recommended that Lt. Col. Hubertus von Aulock (brother of the St. Malo defender) be placed in command of the perimeter defense west and southwest of Paris. Kluge, still in command of OB WEST and Army Group B, promoted Aulock to the rank of major general, gave him authority, under Choltitz, to reorganize the defenses, and assigned him Oehmichen to coordinate the antitank measures. Choltitz, with about 5,000 men and 50 pieces of light and medium artillery inside Paris and about 60 planes based at le Bourget, remained the fortress commander under the nominal control of the First Army.13

When Kluge visited Choltitz around 15 August, the two officers agreed that the capital could not be defended for any length of time with the forces available. In addition, should the city be besieged, the supply problem would be insurmountable. Thus, house-to-house fighting, even assuming the then questionable presence of adequate troops, would serve no useful purpose. Destroying the bridges as ordered, even if sufficient explosives were on hand, was against the best German interest because the Germans could cross the Seine by bridge only at Paris. The better course of action was to defend the outer ring of Paris and block the great arterial highways with obstacles and antitank weapons.

Jodl probably informed Hitler of at least some of this discussion, for on 19 August Hitler agreed that destruction of the Paris bridges would be an error and ordered additional Flak units moved to the French capital to protect them. Impressed with the need to retain the city in order to guarantee contact between the Fifth Panzer and First Armies, Hitler also instructed Jodl to inform the troops that it was mandatory to stop the Allies west and southwest of Paris.14

Since the Americans had of their own accord stopped short of the gates of Paris, the defenders outside the city improved their positions and waited. Inside the

capital the garrison had a sufficient number of tanks and machine guns to command the respect of the civil populace and thereby insure the security of German communications and the rear.15

French Aims

Though was not an immediate major military goal to the Allies, to Frenchmen it meant the liberation of France. More than the spiritual capital, Paris was the only place from which the country could be effectively governed. It was the hub of national administration and politics and the center of the railway system, the communication lines, and the highways. Control of the city was particularly important in August 1944, because Paris was the prize of an intramural contest for power within the French Resistance movement.

The fundamental aim of the Resistance—to rid France of the Germans-cemented together men of conflicting philosophies and interests but did not entirely hide the cleavage between the patriots within occupied France and those outside the country—groups in mutual contact only by secret radios and underground messengers.16 Outside France the Resistance had developed a politically homogeneous character under de Gaulle, who had established a political headquarters in Algiers and a military staff in London, and had proclaimed just before the cross-Channel attack that he headed a provisional government. Inside France, although it was freely acknowledged that de Gaulle had symbolically inspired anti-German resistance, heterogeneous groups had formed spontaneously into small, autonomous organizations existing in a precarious and clandestine status.17 In 1943 political supporters of de Gaulle inside and outside France were instrumental in creating a supreme coordinating Resistance agency within the country that, while not eradicating factionalism, had the effect of providing a common direction to Resistance activity and increasing de Gaulle’s strength and authority in Allied eyes.

Although political lines were not yet sharply drawn, a large, vociferous, and increasingly influential contingent of the left contested de Gaulle’s leadership inside France. This group clamored for arms, ammunition, and military supplies, the more to harass the Germans. Some few in 1943 hoped in this small way to create the second front demanded by the Soviet Union. The de Gaullists outside the country were not anxious to have large amounts of military stores parachuted into France, and the matériel supplied was dropped in rural areas rather than near urban centers, not only to escape German detection but also to inhibit the development of a strong left-wing opposition.18

Early in 1944 the de Gaullists succeeded

in establishing the entire Resistance movement as the handmaiden of the Allied liberating armies. The Resistance groups inside France became an adjunct of OVERLORD. French Resistance members, instead of launching independent operations against the Germans, were primarily to furnish information and render assistance to the Allied military forces. To coordinate this activity with the Allied operations, a military organization of Resistance members was formed shortly before the cross-Channel attack: the French Forces of the Interior. SHAEF formally recognized the FFI as a regular armed force and accepted the organization as a component of the OVERLORD forces. General Koenig (whose headquarters was in London), the military chief of the Free French armed forces already under SHAEF, became the FFI commander. When the Allies landed on French soil, the FFI (except those units engaged in operations not directly connected with the OVERLORD front—primarily those in the south, which were oriented toward the forthcoming ANVIL landing on the Mediterranean coast) came under the command of SHAEF and thus under de Gaulle’s control.19

News in July of unrest in Paris and intimations that there was agitation for an unaided liberation of the city by the Resistance led General Koenig to order immediate cessation of activities that might cause social and political convulsion.20 Since Allied plans did not envision the immediate liberation of the capital, a revolt might provoke bloody suppression on the part of the Germans, a successful insurrection might place de Gaullist opponents in the seat of political power, civil disorder might burgeon into full-scale revolution.

Despite Koenig’s order, the decrease in the German garrison in August, the approach of American troops, and the disintegration of the Pétain government promoted an atmosphere charged with patriotic excitement. By 18 August more than half the railway workers were on strike and virtually all the policemen in the capital had disappeared from the streets for the same reason. Public anti-German demonstrations occurred frequently. Armed FFI members moved through the streets quite openly. Resistance posters appeared calling for a general strike, for mobilization, for insurrection.

The German reaction to these manifestations of brewing revolt seemed so feeble that on 19 August small local FFI groups, without central direction or discipline, forcibly took possession of police stations, town halls, national ministries, newspaper buildings, and the seat of the municipal government, the Hôtel de Ville. The military component of the French Resistance, the FFI, thus disobeyed orders and directly challenged Choltitz.

The Critical Days

The challenge, although serious, was far from formidable. Perhaps 20,000

men in the Paris area belonged to the FFI, but few actually had weapons since the Allies had parachuted only small quantities of military goods to them. While the Resistance had been able to carry on a somewhat systematic program of sabotage and harassment—destroying road signs, planting devices designed to puncture automobile tires, cutting communications lines, burning gasoline depots, and attacking isolated Germans—for the FFI to engage German armed forces in open warfare was quite another matter.21

The leaders of the Resistance in Paris, recognizing the havoc that German guns could bring to an overtly insubordinate civilian population and fearing widespread and bloody reprisals, sought to avert open hostilities. They were fortunate in securing the good offices of Mr. Raoul Nordling, the Swedish consul general, who volunteered to negotiate with Choltitz. Nordling had that very day succeeded in persuading Choltitz not to deport but to release from detention camps, hospitals, and prisons several thousand political prisoners. The agreement, which “represented the first capitulation of Germany,” was a matter of considerable import that “was not lost either on the Resistance or on the people of Paris.”22 Having established a personal relationship with Choltitz that promised to be valuable, Nordling was able to learn on the evening of 19 August that Choltitz was willing to discuss conditions of a truce with the Resistance. That night an armistice was arranged, at first to last only a few hours, later extended by mutual consent for an indefinite period.

Without even a date of expiration, the arrangement was nebulous. Choltitz agreed to treat Resistance members as soldiers and to regard certain parts of the city as Resistance territory. In return, he secured Resistance admission that certain sections of Paris were to be free for German use, for the unhampered passage of German troops. Yet no boundaries were drawn, and neither Germans nor French were certain of their respective sectors. Thus, an uneasy noninterference obtained.23

The advantages for both parties were clear. The French Resistance leaders were uncertain when Allied troops would arrive, anxious to prevent German repressive measures, aware of Resistance weakness to the extent of doubting their own ability to defend the public buildings seized, and finally hopeful of preserving the capital from physical damage.

For the Germans, the cessation of hostilities per se fulfilled Choltitz’ mission of maintaining order within the capital and enabled him to attend to his primary mission of blocking the approaches to the city. Having known for a long time of the attempts to subordinate the Resistance to the Allied military command, the Germans guessed that sabotage directly unrelated to Allied military operations was “mainly the work

of communist groups.”24 It was therefore reasonable for Choltitz to assume that the disorder in Paris on 19 August, which had no apparent connection with developments on the front, was the work of a few extremists. Since part of his mission was to keep order among the population and since the police were no longer performing their duties, Choltitz felt that the simplest way of restoring order was to halt the gunfire in the streets. To prevent what might develop into indiscriminate rioting, he was willing to come to an informal truce, “an understanding,” as he termed it.25

A more subtle reason also lay behind Choltitz’ action. Aware of the factionalism in the French Resistance movement, he tried to play one group off against the other to simplify his problem of control.26 Choltitz believed that since the insurrectionists directed their immediate efforts toward seizing government buildings and communications facilities, the insurrection was at least in part the opening of an undisguised struggle for political power within France. The Pétain government no longer functioned in Paris (Pétainist officials with whom the Germans were accustomed to work no longer answered their telephones), and in this vacuum there was bound to be a struggle for power among the Resistance factions. “The Resistance had reason to fear,” a German official wrote not long afterwards, “that the Communists would take possession of the city before the Americans arrived.”27 By concluding a truce, Choltitz hoped to destroy the cement that held the various French groups together against their common enemy and thus leave them free to destroy themselves.

That Choltitz felt it necessary to use these means rather than force to suppress the insurrection indicated one of two things—either he was unwilling to endanger the lives of women and children or he no longer had the strength to cope with the Resistance. He later admitted to both. In any event, French underground activities had become so annoying that Choltitz’ staff had planned a coordinated attack on widely dispersed Resistance headquarters for the very day the insurrection broke out, but Choltitz himself had suddenly prohibited the action. Instead of resorting to force, he listened to representations in favor of peace from the neutral Swedish and Swiss consulates. Meanwhile, should civil disturbance become worse, Choltitz gathered provisional units to augment his strength, securing, among other units, a tank company of Panzer Lehr.28

Choltitz apparently informed Model, the new chief of OB WEST and Army Group B, of his weakness, for when Hitler on 20 August advised Model that Paris was to become the bastion of the Seine-Yonne River line, Model replied that the plan was not feasible. Although Model had arranged to move the 348th Division to Paris, he did not think these troops could arrive quickly enough

to hold the city against the external Allied threat and the internal Resistance disturbance. Apparently having misunderstood Hitler’s desire, Model decided that the Seine was more important than Paris. Since the Seine flows through the city, defending at the river would necessitate a main line of resistance inside the capital. With the civil populace in a state of hardly disguised revolt, he did not believe Choltitz could keep civil order and at the same time defend against an Allied attack with the strength at hand. Model therefore revealed to OKW that he had ordered an alternate line of defense to be reconnoitered north and east of Paris.29

Model’s action seemed inexcusable since the order to create a fortress city implied that Paris was important enough in Hitler’s judgment to warrant a defense to the last man. Furthermore, Hitler had explicitly stated on 20 August, “If necessary, the fighting in and around Paris will be conducted without regard to the destruction of the city.” Jodl therefore repeated Hitler’s instructions and ordered Model to defend at Paris, not east of it, even if the defense brought devastation to the capital and its people.30

Hitler himself left no doubt as to his wishes when he issued his famous “field of ruins” order:–

The defense of the Paris bridgehead is of decisive military and political importance. Its loss dislodges the entire coastal front north of the Seine and removes the base for the V-weapons attacks against England.

In history the loss of Paris always means the loss of France. Therefore the Führer repeats his order to hold the defense zone in advance [west] of the city. ...

Within the city every sign of incipient revolt must be countered by the sharpest means ... [including] public execution of ringleaders. ...

The Seine bridges will be prepared for demolition. Paris must not fall into the hands of the enemy except as a field of ruins.31

The French Point of View

Resistance leaders in Paris had meanwhile radioed the exterior Resistance for help, thereby alarming Frenchmen outside Paris by reports, perhaps exaggerated, of disorder in the city and by urgent pleas that military forces enter the capital at once.32 De Gaulle and his provisional government had long been worried that extremist agitation not only might bring violent German reaction but also might place unreliable Resistance elements in the capital in political power. The parties of the left were particularly influential in the Paris Resistance movement, to the extent that the FFI commander of Paris belonged to one of them. Conscious of the dictum that he who holds Paris holds France and sensitive to the tradition of Paris as a crucible of revolution, its population ever ready to respond to the

cry “Aux barricades!” the French commanders within the OVERLORD framework advocated sending aid to Paris immediately.33 Their argument was that if riot became revolution, Paris might become a needless battleground pulling Allied troops from other operations.

An immediate hope lay in parachuting arms and ammunition into the city. This would enable the FFI to resist more effectively and perhaps permit the Resistance to seize tactically important points that would facilitate Allied entry. Despite a natural reluctance to arm urban people and SHAEF’s concern that the heavy antiaircraft defenses of Paris might make an air mission costly, an airdrop of military equipment was scheduled for 22 August. When a thick fog that day covered all British airfields, the drop was postponed. On the following day, when the British radio made a premature announcement that Paris had already been liberated, SHAEF canceled the operation.34

The decisive solution obviously lay in getting Allied troops into the capital, for which provision had been made in Allied plans as early as 1943. SHAEF had agreed to include a French division on the OVERLORD troop list “primarily so that there may be an important French formation present at the re-occupation of Paris.”35 The 2nd French Armored Division had been selected. Just before the cross-Channel attack and again early in August, the French military chief, General Koenig, had reminded General Eisenhower of the Allied promise to use that unit to liberate Paris. Its entry into the capital would be a symbolic restoration of French pride as well as the preparation for de Gaulle’s personal entry into Paris, symbolic climax of the French Resistance.36 When the situation seemed propitious for these events to take place, General Leclerc’s armored division was at Argentan, more than a hundred miles away, while American troops were less than twenty-five miles from the center of the capital. If the French could persuade General Eisenhower to liberate Paris at once, would he be able to honor his promise to employ Leclerc?

General Eisenhower had no intention of changing the plan to bypass Paris, as Generals de Gaulle and Koenig discovered when they conferred with him on 21 August, but he repeated his promise to use Leclerc’s division at the liberation. Although the French had agreed to abide by General Eisenhower’s decisions on the conduct of the war in return for Allied recognition of a de facto government headed by de Gaulle, General Alphonse Juin that same day, 21 August, carried a letter from de Gaulle to the Supreme Commander to threaten politely that if General Eisenhower did not send troops to Paris at once, de Gaulle might have to do so himself.37 The threat was important, for de Gaulle

was the potential head of the French government and would theoretically stand above the Supreme Commander on the same level with President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill.

Leclerc, who was conscious of the historic mission reserved for him, had long been impatient for orders to move to Paris. As early as 14 August, when he learned that Patton was sending part of the XV Corps (but not the 2nd French Armored Division) eastward from Argentan, Leclerc had requested the corps commander to query the Third Army commander as to when the French division was to go to Paris. Leclerc’s explanation—“It is political”—availed little, for the army chief of staff bluntly ordered that Leclerc was to remain where he was. Two days later Leclerc wrote Patton suggesting that since the situation at Argentan had become quiet, the 2nd French Armored Division might commence to assemble for its projected march on Paris.38 That evening he visited Patton’s headquarters, where he saw Bradley as well as Patton, and gained cordial assurance from both that he would have the honor of liberating the capital. Patton laughingly turned to General Wood, who was also present and who had been pressing for permission to lead his 4th Armored Division to Paris. “You see, Wood,” Patton supposedly said, “he [Leclerc] is a bigger pain in the neck than you are.”39 Patton nevertheless announced his intention of moving Leclerc to Dreux as soon as possible.40

Unfortunately for Leclerc’s hopes, the last stage of operations to close the Argentan–Falaise pocket had started, and his armored division found itself again engaged, eventually under the control of the First U.S. Army and General Gerow’s V Corps. Although Leclerc was not told, Bradley and Patton on 19 August agreed once more that only the French division would “be allowed to go into Paris,” probably under First Army control.41 Leclerc fretted and bombarded V Corps headquarters with requests premised on the expectation of a momentary call to Paris—for example, he attempted to secure the release of the French combat command attached to the 90th Division. For his part, General Gerow saw no reason to employ the French division any differently from his American units, for Paris was no specific concern of his.42

Invited by General Hodges to lunch on 20 August, Leclerc seized upon the occasion for “arguments, which he presented incessantly,” that roads and traffic and plans notwithstanding, his division should run for Paris at once. He said he needed no maintenance, equipment, or personnel, but a few minutes later admitted that he needed all three. General Hodges “was not impressed with him or his arguments, and let him understand that he was to stay put” until he received orders to move.43

When British troops on 21 August moved across the V Corps front and V

Corps divisions began to withdraw to assembly areas south of Argentan, Leclerc saw no justification for remaining so far distant from his ultimate objective. “We shall not stop,” he had said in 1941, “until the French flag flies over Strasbourg and Metz,” and along the route to these capitals of Alsace and Lorraine, Paris was a holy place.44 He persuaded himself that Gerow was sympathetic to his wishes, and though the corps commander was powerless to authorize Leclerc’s march on Paris, Leclerc convinced himself that as the sole commander of French regular military forces in Operation OVERLORD, he was entitled to certain prerogatives involving national considerations.45 Furthermore, since Koenig, who anticipated that the 2nd Armored would liberate Paris sooner or later, had appointed Leclerc provisional military governor of the capital, Leclerc felt that this gave him authority to act.46 With at least an arguable basis for moving on Paris, Leclerc on the evening of 21 August (the same day that Eisenhower had rejected de Gaulle’s request) dispatched a small force of about 150 men—ten light tanks, ten armored cars, ten personnel carriers—under a Major Guillebon toward the capital. Guillebon ostensibly was to reconnoiter routes to Paris, but should the Allies decide to enter the city without the 2nd French Armored Division, Guillebon was to accompany the liberating troops as the representative of the provisional government and the French Army.47 Writing to de Gaulle that evening, Leclerc explained, “Unfortunately, I cannot do the same thing for the bulk of my division because of matters of food and fuels” (furnished by the U.S. Army) and because of respect for the “rules of military subordination.”48

Knowing that Guillebon could not reach Paris undetected, Leclerc sent his G-2, Maj. Philippe H. Repiton, to Gerow on the morning of 22 August to explain his act on the following basis: insurrection in the capital made it necessary for an advance military detachment to be there to maintain order until the arrival of regular French political authorities. Guillebon’s absence, Leclerc pointed out, did not compromise the ability of the division to fulfill any combat mission assigned by the corps. Gerow, who was thoroughly a soldier and who had received a peremptory message from the Third Army asking what French troops were doing outside their sector, saw only Leclerc’s breach of discipline. “I desire to make it clear to you,” Gerow wrote Leclerc in a letter he handed personally to Repiton, “that the 2nd Armored Division (French) is under my command for all purposes and no part of it will be employed by you except in the execution of missions assigned by this headquarters.” He directed Leclerc to recall Guillebon.49

Unwilling to comply, Leclerc sought

higher authority by taking a plane to the First Army headquarters. There he learned that General Bradley was conferring with General Eisenhower on the question of Paris. Leclerc decided to await the outcome of the conference.

Eisenhower’s Decision

Reflecting on Choltitz’ behavior after the truce arrangement, Resistance members were somewhat puzzled. They began to interpret his amenity as a special kind of weakness, a weakness for the physical beauty as well as the historical and cultural importance of Paris. They figured that Choltitz was appalled by the destruction he had the power to unleash, and they wondered whether he worried that fate had apparently selected him to be known in history as the man who had ravaged the capital.50 How else could one explain his feigned ignorance of the Resistance, his calling the insurrection only acts of violence committed by terrorists who had infiltrated into the city and who were attempting to incite a peaceful population to revolt, his pretense that he had no authority over French civilians (despite his plenary power from Hitler to administer Paris), his acceptance of Nordling’s explanation that the Resistance members were not terrorists or ruffians but patriotic Frenchmen, and his willingness to agree to a truce? Either that or he felt that the German cause was hopeless. His offhand but perhaps studied remark to Nordling that he could of course not be expected to surrender to irregular troops such as the FFI seemed a clear enough indication that to salve his honor and protect his family in Germany he had at least to make a pretense of fighting before capitulating to superior forces. He apparently would surrender to regular Allied troops after a show of arms.

To convince the Allied command of the need for regular forces in Paris at once while Choltitz vacillated between desire and duty, Resistance emissaries, official and unofficial, departed the city to seek Allied commanders.51 Nordling’s brother Rolf and several others in a small group reached the Allied lines on 23 August and made their way up the echelons to the Third Army headquarters. Patton, who was disappointed in being denied, was contemptuous of their efforts. Deciding that “they simply wanted to get a suspension of hostilities in order to save Paris, and probably save the Germans,” he “sent them to General Bradley, who”—he imagined incorrectly—“arrested them.”52

Nordling’s group reached Bradley’s command post too late to affect the course of events, but another envoy, Resistance Major Gaullois (pseudonym of a M. Cocteau), the chief of staff of the Paris FFI commander, had left Paris on 20 August and had reached Bradley’s headquarters on the morning of 22 August.53 He may have had some influence, for he spoke at some length with Brig. Gen. A. Franklin Kibler, the 12th Army Group G-3, who displayed interest in the information that Choltitz would surrender his entire garrison as soon as

Allied troops took his headquarters—the Hôtel Meurice on the rue de Rivoli.54

It so happened that General Eisenhower had on the evening of 21 August (after his conference with de Gaulle) begun to reconsider his decision to delay . In this connection he requested Bradley to meet with him on the morning of 22 August. De Gaulle’s letter, delivered by Juin, had had its effect, and Eisenhower had jotted down that he would probably “be compelled to go into Paris.”55 The Combined Chiefs of Staff had informed him on 16 August that they had no objection to de Gaulle’s entry into the capital, certainly strong evidence of Allied intentions to recognize his government, and it was becoming increasingly clear that the majority of French people approved of de Gaulle and thereby reinforced his claim to legality.56 Koenig’s deputy, a British officer who reflected the British point of view of favoring (apparently more so than the United States) de Gaulle’s political aspirations, also urged the immediate liberation of the capital.57 Pressed on all sides, General Eisenhower set forth his dilemma in a letter to General Marshall:–

Because of the additional supply commitment incurred in the occupation of Paris, it would be desirable, from that viewpoint, to defer the capture of the city until the important matter of destroying the remaining enemy forces up to include the Pas de Calais area. I do not believe this is possible. If the enemy tries to hold Paris with any real strength he would be a constant menace to our flank. If he largely concedes the place, it falls into our hands whether we like it or not.58

The dilemma had another aspect. If liberating Paris only fulfilled a political need, then the Supreme Commander’s position of conducting operations on military grounds alone would not allow him in good conscience to change his mind—unless he turned Leclerc and the French loose to liberate the capital as they wished. If he could not approve such a politically motivated diversion of part of his forces, or if he felt he could not afford to lose control of the French division, he had to have a military basis for an Allied liberation. Yet how could he initiate action that might damage the city? The only solution seemed to be that if the Germans were ready to quit the city without giving battle, the Allies ought to enter—for the prestige involved, to maintain order in the capital, to satisfy French requests, and also to secure the important Seine crossing sites there.

Much indicated to General Eisenhower that the Germans were ready to abandon Paris. De Gaulle thought that a few cannon shots would disperse the Germans. Bradley had told Eisenhower that he, Bradley, agreed with his G-2, who thought “we can and must walk in.” Bradley had even suggested, facetiously, that the large number of civilian newspapermen accredited to his headquarters comprised a force strong enough to take the city “any time you want to,” and that

if they did, they would “spare us a lot of trouble.”59

In the midst of conflicting rumors that Choltitz was ready to capitulate and that the Germans were ready to destroy the city with a secret weapon, the Resistance envoys appeared. They brought a great deal of plausible, though incorrect, information. They assured the Allied command that the FFI controlled most of the city and all the bridges, that the bulk of the Germans had already departed, that enemy troops deployed on the western outskirts were only small detachments manning a few roadblocks. They argued that the Germans had agreed to the armistice because the German forces were so feeble they needed the truce in order to evacuate the city without fighting their way through the streets. The envoys stated both that the armistice expired at noon, 23 August, and that neither side respected the agreement. Since the FFI had few supplies and little ammunition and was holding the city on bluff and nerve, the Resistance leaders feared that the Germans were gathering strength to regain control of the city and bring destruction to it upon the termination of the truce. To avoid bloodshed, it was essential that Allied soldiers enter the city promptly at noon, 23 August.60

Unaware that the reports were not entirely accurate, the Allied command reached the conclusion that if the Allies moved into Paris promptly, before guerrilla warfare was resumed, Choltitz would withdraw, and thus the destruction of the bridges and historic monuments that would ensue if he had to fight either the Resistance or the Allies would be avoided.61 Since the available “information indicated that no great battle would take place,” General Eisenhower changed his mind and decided to send reinforcement to the FFI in order to repay that military organization, as he later said, for “their great assistance,” which had been “of inestimable value in the campaign.”62 Reinforcement, a legitimate military action, thus, in Eisenhower’s mind, transferred from the political to the military realm and made it acceptable.

To make certain that Choltitz understood his role in , an intelligence officer of the “‘Economic Branch’ of the U.S. Service” was dispatched to confirm with Choltitz the “arrangement” that was to save the city from damage. The Allies expected Choltitz to evacuate Paris at the same time that Allied troops entered, “provided that he did not become too much involved in fighting the French uprising.” The time selected for the simultaneous departure and entry was the supposed time the truce expired—noon, 23 August.63

Allied Airlift, planned on 22 August, began delivery of food and fuel to the people of Paris on 27 August.

Since a civil affairs commitment was an inescapable corollary of the decision to liberate Paris, General Eisenhower ordered 23,000 tons of food and 3,000 tons of coal dispatched to the city immediately. General Bradley requested SHAEF to prepare to send 3,000 tons of these supplies by air. The British also made plans to fulfill their part of the responsibility.64

The decision made, Bradley flew to Hodges’ First Army headquarters late in the afternoon of 22 August to get the action started. Finding Leclerc awaiting him at the airstrip with an account of his differences with Gerow over Guillebon’s movement to Paris, Bradley informed Leclerc that General Eisenhower had just decided to send the French armored division to liberate Paris at once. Off the hook of disobedience, Leclerc hastened to his command post, where his joyous shout to the division G-3, “Gribius, ... mouvement immédiat sur Paris!” announced that a four-year dream was finally about to come true.65

On to Paris

“For the honor of first entry,” General Eisenhower later wrote, “General Bradley selected General Leclerc’s French 2nd Division.” And General Bradley explained, “Any number of American divisions could more easily have spearheaded our march into Paris. But to help the French recapture their pride after four years of occupation, I chose a French force with the tricolor on their Shermans.” Yet the fact was that SHAEF was already committed to this decision. Neither Eisenhower nor Bradley could do anything else except violate a promise, an intention neither contemplated. Perhaps the presence and availability of the French division made it such an obvious choice for the assignment that the prior agreement was unimportant, possibly forgotten. Both American commanders wanted to do the right thing. Even General Hodges had independently decided about a week earlier that if he received the mission to liberate Paris he would include French troops among the liberation force.66

Suddenly General Bradley was at the First Army headquarters on the afternoon of 22 August with “momentous news that demanded instantaneous action.” Since 20 August, he told General Hodges, Paris had been under the control of the FFI, which had seized the principal buildings of the city and made a temporary armistice with the Germans that expired at noon, 23 August. Higher headquarters had decided that Paris could no longer be bypassed. The entry of military forces was necessary at once to prevent possible bloodshed among the civilian population. What troops could Hodges dispatch without delay?

General Hodges said that V Corps had completed its assignment at Argentan and was ready for a new job. From Argentan the corps could move quickly to the French capital with Leclerc’s 2nd French Armored and Barton’s 4th Infantry Divisions. It would be fair for General Gerow, the corps commander, to have the task of liberating Paris because he and Collins had been the two American D-Day commanders and Collins had had the honor of taking Cherbourg.

Bradley accepted Hodges’ recommendation, and the V Corps was alerted for immediate movement to the east. Then frantic phone calls were put in to locate General Gerow. He was found at the 12th Army Group headquarters and instructed to report to the army command post with key members of his staff. Late that afternoon, as Gerow and his principal assistants gathered in the army war room, a scene that had taken place a week earlier was repeated. Maps were hastily assembled, movement orders hurriedly written, march routes and tables determined, and careful instructions prepared for the French, “who have a casual manner of doing almost exactly what they please, regardless of orders.”67

General Gerow learned that General Eisenhower had decided to send troops

to Paris to “take over from the Resistance Group, reinforce them, and act in such mobile reserve as ... may be needed.” The Allies were to enter Paris as soon as possible after noon of 23 August. The Supreme Commander had emphasized that “no advance must be made into Paris until the expiration of the Armistice and that Paris was to be entered only in case the degree of the fighting was such as could be overcome by light forces.” In other words, General Eisenhower did not “want a severe fight in Paris at this time,” nor did he “want any bombing or artillery fire on the city if it can possibly be avoided.”68

A truly Allied force was to liberate the city: the 2nd French Armored Division, the 4th U.S. Infantry Division, an American cavalry reconnaissance group, a 12th Army Group technical intelligence unit, and a contingent of British troops. The French division, accompanied by American cavalry and British troops, all displaying their national flags, was to enter the city while the 4th Division seized Seine River crossings south of Paris and constituted a reserve for the French. Leclerc was to have the honor of liberating Paris, but he was to do so within the framework of the Allied command and under direct American control.69

The leader of the expedition, General Gerow, had been characterized by General Eisenhower as having demonstrated “all the qualities of vigor, determination, reliability, and skill that we are looking for.”70 Further, he had had the experience needed for a mission fraught with political implications. Serving with the War Plans Division of the War Department from 1936 to 1939, he was chief of that division during the critical year of 1941. He was thus ho stranger to situations involving the interrelationship of military strategy and national policy. Yet he had not been informed of the political considerations involved, and his instructions to liberate Paris were of a military nature.71

Acting in advance on General Hodges’ orders to be issued on 23 August to “force your way into the city this afternoon,” Gerow telephoned Leclerc on the evening of 22 August and told him to start marching immediately. The 38th Cavalry Squadron was to accompany Leclerc to “display the [American] flag upon entering Paris.”72 According to the formal corps order issued later, the only information available was that the Germans were withdrawing from Paris in accordance with the terms of the armistice. The rumor that the Germans had mined the sewers and subways was important only in spurring the Allies to occupy the city in order to prevent damage. No serious opposition was expected. If the troops did, however, encounter strong resistance, they were to assume the defensive.73

Despite the anticipated absence of opposition, Gerow commanded a large force that was to move on two routes-Sées, Mortagne, Château-en-Thymerais, Maintenon, Rambouillet, Versailles; and Alençon, Nogent-le-Rotrou, Chartres, Limours, Palaiseau. The northern column—the bulk of the French division, the attached American troops, a U.S. engineer group (controlling three combat battalions, a treadway bridge company, a light equipment platoon, and a water supply platoon), the V Corps Artillery (with four firing battalions and an observation battalion), in that order of march—had an estimated time length of fourteen hours and twenty-five minutes. The southern column—a French combat command, the bulk of the American cavalry, the V Corps headquarters, the 4th Division (reinforced by two tank destroyer battalions, an antiaircraft battalion, two tank battalions), in that order—had a time length of twenty-two hours and forty minutes. For some unexplained reason the British force, despite General Eisenhower’s explicit desire for British participation, failed to appear. To make certain that the French troops, which led both columns, respected the truce in the capital, Gerow ordered that no troops were to cross the Versailles-Palaiseau line before noon, 23 August.74 (Map XIII)

Although Gerow had ordered Leclerc to start to Paris immediately on the evening of 22 August, the division did not commence its march until the morning of 23 August. By evening of 23 August the head of the northern column was several miles beyond Rambouillet on the road to Versailles; the southern column had reached Limours. At both points, the French met opposition.

Within Paris, before receiving Hitler’s order to leave the city to the Allies only as a “field of ruins,” Choltitz had had no intention of doing anything but his duty. His handling of the insurrection was sufficient evidence of that. When Aulock, who commanded the perimeter defenses west of the city, requested permission to withdraw on 22 August because he felt he could not stop an Allied advance, Choltitz said no. But after receiving Hitler’s order and realizing that he was expected to die among the ruins, Choltitz began to reconsider. About the same time he learned that the 348th Division, which was moving from northern France to strengthen the Paris defenses, was instead to be committed north of the capital along the lower Seine.75 At that moment he became rather cynical. “Ever since our enemies have refused to listen to and obey our Führer,” he supposedly remarked at dinner one evening, “the whole war has gone badly.”76

One of Choltitz’ first reactions to Hitler’s “field of ruins” order was to phone Model and protest that the German high command was out of tune with reality. The city could not be defended. Paris was in revolt. The French held important administrative buildings. German forces were inadequate to the task of preserving order. Coal was short. The rations available would last the

troops only two more days.77 But Choltitz was unable to secure a satisfactory alternative from Model, so he phoned Speidel, Model’s chief of staff at Army Group B. After sarcastically thanking Speidel for the lovely order from Hitler, Choltitz said that he had complied by placing three tons of explosive in the cathedral of Notre Dame, two tons in the Invalides, and one in the Palais Bourbon (the Chamber of Deputies), that he was ready to level the Arc de Triomphe to clear a field of fire, that he was prepared to destroy the Opéra and the Madeleine, and that he was planning to dynamite the Tour Eiffel and use it as a wire entanglement to block the Seine. Incidentally, he advised Speidel, he found it impossible to destroy the seventy-odd bridges.78

Speidel, who had received Hitler’s order from OKW and had realized that the destruction of the bridges meant destroying monuments and residential quarters, later claimed that he had not transmitted the order forward and that Choltitz had received it directly from OB WEST. Yet, since Gestapo agents were monitoring Speidel’s telephone to prove his complicity in the July 20th plot, Speidel later recalled that he urged Choltitz—as diplomatically and as obliquely as he knew how—not to destroy the French capital.79

Choltitz had no intention of destroying Paris. Whether he was motivated by a generous desire to spare human life and a great cultural center, or simply by his lack of technical means to do so—both of which he later claimed—the fact was that representatives of the neutral powers in Paris were also exerting pressure on him to evacuate Paris in order to avoid a battle there.80 Yet Choltitz refused to depart. Whether he was playing a double game or not, his willingness to avoid fighting inside Paris did not change his determination to defend Paris outside the city limits—a defense that eventually included orders to demolish the Seine River bridges, three rejections of Allied ultimatums to surrender, and refusal of an Allied offer to provide an opportunity for him to withdraw.81

The field fortifications on the western and southern approaches to the city formed a solid perimeter that was more effective than Aulock judged. Obviously, 20,000 troops dispersed over a large area could not hold back the Allies for long, but they could make a strong defense. Artillery, tanks, and antiaircraft guns sited for antitank fire supported strongpoints at Trappes, Guyancourt, Châteaufort, Saclay, Massy, Wissous, and Villeneuve-le-Roi. The roads to Versailles were well blocked, and

forward outposts at Marcoussis and Montlhéry as well as strong combat outposts at Palaiseau and Longjumeau covered the approaches to the positions guarding the highway north from Arpajon.82

On the Allied side, there was practically no information on the actual situation inside Paris and on its approaches. When General Leclerc arrived in Rambouillet with a small detachment around noon 23 August, well ahead of his division, he learned for the first time from his reconnaissance elements and from French civilians that there appeared to be a solid defense line along the western and southwestern suburbs of Paris, a line reinforced by tanks, antitank weapons, and mines. This meant that a major effort by the whole division would be necessary to open the way into the city proper.

Eager though he was to come to the rescue of the FFI in Paris, which he thought might have by this time liberated the interior of the city, General Leclerc had to postpone his attack. He had to wait until the following morning because the main body of his division could not reach the Rambouillet area before evening of the 23rd.83

The Liberation

Leclerc’s plan of attack departed from Gerow’s instructions. Two combat commands, Colonel de Langlade’s and Colonel Dio’s, in that order, were advancing toward Rambouillet on the northern route; Col. Pierre Billotte’s combat command was on the south. Instead of making the main effort from the west through Rambouillet and Versailles, Leclerc decided to bring his major weight to bear on Paris from the south, from Arpajon. He directed Billotte to go from Limours to Arpajon, turn north there, and attack toward the southern part of Paris. He switched Dio to the southern route in direct support of Billotte. CCR was to stage a diversionary attack toward St. Cyr, while Langlade, skirting Versailles on the south, was to push through Chevreuse and Villacoublay to Sèvres. When Leclerc showed his operations order to General de Gaulle, who was at Rambouillet that evening, de Gaulle said merely that Leclerc was lucky to have the opportunity of liberating Paris, and thereby, by inference at least, approved.84

Not so the Americans, who years later could not understand Leclerc’s reasons for disregarding the V Corps instructions. Was Leclerc reluctant to attack through Versailles because he did not want to endanger that national monument? Was he concerned about securing the right flank protection afforded by the Seine River and the destroyed bridges between Corbeil and Paris? Though he had cautioned his troops to avoid the large traffic arteries, was he attracted nevertheless to the wide Orléans—Paris highway, which passes through Arpajon? Did he want to display his independence and his resentment

General Leclerc at Rambouillet, on the Road to Paris

of American control in a matter that seemed to him to be strictly French? Perhaps he had not even seen Gerow’s instructions.85

Actually, the military basis of Leclerc’s decision was his estimate that the opposition along the Arpajon-Paris axis seemed “less robust” than in the Rambouillet-Versailles area.86 Guillebon’s detachment on the previous day had encountered German outposts near Arpajon.

These were weak when compared to the positions in the Rambouillet area, where American troops of the XX Corps had swept aside the outposts and laid bare the main line of resistance. By deciding to make his main effort at Arpajon, Leclerc inadvertently selected as his point of intended penetration the place where the German defense was in greatest depth.

There were other unfortunate results. By directing his southern column to go from Limours to Arpajon, he impinged on the sector of the 4th Division. By switching his principal effort from Versailles to the southern axis through

French Soldiers Attack Toward Châteaufort

Arpajon, he placed his main attack outside the range of the V Corps Artillery.87 When Gerow received Leclerc’s operations order on the morning of 24 August, he immediately warned General Barton, the 4th Division commander, of French encroachment but instructed Barton to continue on his mission “without regard to movements of French troops.” After informing General Hodges, the army commander, of Leclerc’s activity, Gerow drove to Rambouillet to see Leclerc and straighten out the matter. He discovered that Leclerc had gone forward from Rambouillet. Gerow followed until traffic congestion forced him to return to his command post.88

Meanwhile, Leclerc had launched his attack toward Paris at dawn, 24 August, in a downpour of rain that later diminished to a drizzle. On the left, CCR made a diversionary attack to block off St. Cyr, and Langlade moved toward Châteaufort and Toussus-le-Noble. The armored columns quickly encountered mines and artillery fire, but after a four-hour fire fight at close range, the French knocked out three of eight tanks and penetrated the German defensive line. With only slight enemy interference, Langlade’s combat command then swept toward the Pont de Sèvres, the greatest obstruction being the enthusiastic welcome of civilians, who swarmed about the combat vehicles, pressing flowers,

kisses, and wine on their liberators and luring some from duty. “Sure we love you,” the more conscientious soldiers cried, “but let us through.” At Sèvres by evening, Langlade found the bridge still intact and unmined. He quickly sent several tanks across the Seine and established a bridgehead in the suburb immediately southwest of Paris. French troops had almost, but not quite, reached the capital.

Billotte’s combat command in the main effort north from Arpajon had a much more difficult time. Encountering resistance at once, the troops had to turn to a dogged advance through a succession of German outposts, roadblocks, and well-positioned strongpoints supported by numerous antiaircraft guns sited for antitank fire. Narrow, crooked roads through a densely populated region of small stone villages further frustrated rapid progress. It took two full-scale assaults to capture Massy, and costly street fighting was necessary to take heavily defended Fresnes that evening. American tactical air support could not assist because of the rainy weather.89

Whereas Langlade had moved fifteen miles, had tanks across the Seine, and was almost touching Paris, Billotte, after advancing thirteen bitter miles, was still five miles from the Porte d’Orléans (the closest point of entry into the city proper), seven miles from the Pantheon (his objective), and eight miles from Ile de la Cité, the center of the capital. The easy entrance the Allies had expected had not materialized.

To the American commanders following French progress on the midafternoon of 24 August, it was incredible that Leclerc had not yet liberated Paris. Since they expected the Germans to withdraw, Leclerc’s slow progress seemed like procrastination. That the French had failed to move immediately from Argentan and to reach their designated line of departure by noon, 23 August, seemed to substantiate this feeling. If Leclerc’s inability to move more rapidly on 24 August was due to his unwillingness to “jeopardize French lives and property by the use of means necessary to speed the advance,” that too was insubordination, for Leclerc had been instructed that restrictions on bombing and shelling Paris did not apply to the suburbs.90

It seemed to Bradley, as he recalled later, that the French troops had “stumbled reluctantly through a Gallic wall as townsfolk along the line of march slowed the French advance with wine and celebration.”91 Gerow substantiated the impression. It appeared to him that the resistance was slight and the attack halfhearted, that the French were fighting on a one-tank front and were not only unwilling to maneuver around obstacles but also were reluctant to fire into buildings.92

Exasperated because Leclerc was disregarding “all orders to take more aggressive action and speed up his advance,” General Gerow requested authority to send the 4th Division into Paris. Permission might be enough, he thought, to shame Leclerc into greater activity and increased effort. Agreeing

that he could not wait for the French “to dance their way to Paris,” Bradley exclaimed, “To hell with prestige, tell the 4th to slam on in and take the liberation.”93

Actually, Leclerc had all the incentive he could possibly need to enter Paris quickly. He was quite conscious of the prestige involved for French arms and aware of the personal distinction that awaited him as the hero of the liberation. He had heard conflicting and exaggerated reports of the German threats, reprisals, and destruction that only the entrance of regular troops could prevent. He knew that de Gaulle expected him to be in Paris on 24 August to resolve the internecine struggle for power in the capital—“Tomorrow,” de Gaulle had written the previous evening, “Tomorrow will be decisive in the sense that we wish.”94

Four factors had retarded Leclerc: faulty attack dispositions; the reluctance of his troops to damage French property; the real problem posed by the enthusiastic welcome of the French population; and the German opposition, which had been stronger than anticipated.

The 4th Division staff understood that the American division was being ordered into Paris as a normal procedure of reinforcing a unit that was having unexpected difficulty with an enemy who was not withdrawing, but instead strengthening his defenses. A British intelligence agency reported no evidence that the French were moving too slowly and declared: “ ... the French Armored Division is moving into Paris at high speed. Those enemy elements ... in the. way ... have been very roughly handled indeed.” Finally, French losses in the battle toward Paris did not indicate an absence of opposition; 71 killed, 225 wounded, 21 missing, and 35 tanks, 6 self-propelled guns, and 111 vehicles destroyed totaled rather heavy casualties for an armored division.95

The American commanders, however, were less interested in reasons than in results. Ordered to liberate Paris and dissatisfied with Leclerc’s progress, they committed the 4th U.S. Infantry Division without regard to preserving the glory of the initial entry for the French. “If von Choltitz was to deliver the city,” General Bradley wrote, “we had a compact to fulfill.”96

Advised by Hodges that it was “imperative” for Allied troops to be in Paris without delay and that considerations of precedence in favor of the French no longer applied, Gerow ordered Leclerc: “Push your advance vigorously this afternoon and continue advance tonight.” He notified General Barton that he was still to secure a Seine River bridgehead near Corbeil, but now he was to shift his main effort from east to north and use all the means at his disposal “to force a way into the city as rapidly as possible.” When Barton said that he would start north from Villeneuve-le-Roi two hours

after midnight, Gerow informed Leclerc that Barton would help the French and that Leclerc was to render assistance to Barton “in every way.”97

Leclerc decided to make one more effort that night. Although Langlade was practically inside the city at Sèvres and faced no opposition, Leclerc could get no word to him, for, as the French admitted, “liaison between the columns for all practical purposes no longer exists.”98 For that reason, Leclerc called on Billotte to dispatch a small detachment of tanks and half-tracks to infiltrate into the city. A small force under a Captain Dronne rolled along side roads and back streets, through the southern suburbs. Civilians pushed aside trees they had felled along the routes to hamper the Germans, repaved streets they had torn up to build barricades, and guided Dronne into the capital by way of the Porte de Gentilly (between the Porte d’Orléans and the Porte d’Italie). Following small streets, Dronne crossed the Seine by the Pont d’Austerlitz, drove along the quays of the right bank, and reached the Hôtel de Ville shortly before midnight, 24 August.99

Although the Germans had resisted effectively on 24 August, their defenses melted away during the night as Choltitz ordered Aulock to withdraw behind the Seine.100 General Barton, who had assembled the 4th Division near Arpajon, selected the 12th Infantry—which was closest to Paris and had lost over 1,000 casualties while attached to the 30th Division at Mortain and needed a boost to morale—to lead the division into Paris on 25 August. Motorized, the regiment started to take the road through Athis-Mons and Villeneuve-le-Roi, but gunfire from the east bank of the Seine deflected the movement away from the river. Without encountering resistance, the troops, screened by the 102nd Cavalry Group, reached Notre Dame cathedral before noon, 25 August, “the only check ... being the enormous crowd of Parisians in the streets welcoming the troops.” Units of the regiment occupied the railroad stations of Austerlitz, Lyon, and Vincennes, and reconnaissance elements pushed northeast and east to the outskirts of the city.101 (Map 18)

While American troops secured the eastern half of Paris, the French took the western part. Langlade’s command advanced to the Arc de Triomphe, Billotte’s to Place du Châtelet, the spearheads of both columns meeting later at Rond Point des Champs Elysées. Dio’s troops, split into two task forces, moved to the Ecole Militaire and to the Palais Bourbon. Several sharp engagements took place with Germans entrenched in public buildings, some of them of great historic value—Luxembourg, Quai d’Orsay, Palais Bourbon, Hôtel des Invalides, and Ecole Militaire among

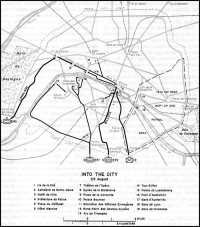

Map 18. Into the City, 25 August

others. About two thousand Germans remained in the Bois de Boulogne. To avoid a fanatic last-ditch struggle that might irreparably damage the city, Choltitz’ formal surrender was necessary. Though Nordling presented him with an ultimatum from Billotte, Choltitz refused to capitulate.

In the Rue de Rivoli, 25 August.

The end came after French tankers surrounded the Hôtel Meurice shortly after noon, set several German vehicles under the rue de Rivoli arcades on fire, and threw smoke grenades into the halls of the hotel. A young French officer suddenly burst into Choltitz’ room and in his excitement shouted, “Do you speak German?” “Probably better than you,” Choltitz replied coolly and allowed himself to be taken prisoner.102

Leclerc had installed his command post in the Montparnasse railway station, but he himself went to the Prefecture of Police. Barton, who was in Paris and wanted to coordinate the dispositions of the divisions with Leclerc, located him there having lunch. Holding his napkin and appearing annoyed at being disturbed, Leclerc came outside to talk with

Barton. Without inviting him to lunch, Leclerc suggested that Barton go to the Montparnasse station. Barton, who was hungry as well as irritated by Leclerc’s attitude, finally said, “I’m not in Paris because I wanted to be here but because I was ordered to be here.” Leclerc shrugged his shoulders. “We’re both soldiers,” he said. Barton then drove to the Gare Montparnasse, where he found General Gerow already taking charge of the enormous responsibility of Paris.103

Instead of taking Choltitz to Montparnasse, which would have been normal procedure, his French captors took him to the Prefecture of Police, where Leclerc was waiting. There Choltitz signed a formal act of capitulation in the presence of Leclerc and the commander of the Paris FFI, who together as equals

accepted Choltitz’ surrender—not as representatives of the Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force, but in the name of the Provisional Government of France.104 Copies of the document were quickly reproduced and circulated by special teams of French and German officers to scattered enemy groups still in the city. All surrendered (including a large force of 700 men with several tanks in the Luxembourg gardens) except the troops in the Bois de Boulogne.105 The V Corps took about

10,000 prisoners in the city and received a “staggering amount of information ... from FFI sources.” Choltitz made certain that the Allies understood that “he could have destroyed bridges and public buildings but despite pressure from above would not give [the] order” to do so.106

Choltitz insisted that only the arrival of military forces had “saved Paris from going up in smoke.” He stated that neither mines nor booby traps had been placed in the city. He said that he had concluded long before his capitulation that it “was hopeless” to defend the city; and he had thus “taken no great steps to do so.” He asserted that the war among the French political factions had “surpassed all his expectations.” He emphasized that “he was damn glad to get rid of the job of policing both Paris and the Frenchmen, both of which he apparently detests.”107

As for the internecine struggle for political power inside the capital, the de Gaullists had proved more astute and better disciplined than their opponents. Taking advantage of the insurrection on 19 August, they had quickly seized the seat of government and taken the reins of political control.

The Aftermath

Paris was liberated, but one more scene was required—the appearance of General de Gaulle. He arrived unannounced in the city on the afternoon of 25 August to an enthusiastic reception by deliriously cheering Parisians. The demonstration persuaded him to make an official entry to strengthen an uneasy political unity that prevailed and to display his personal power. He therefore requested Leclerc to furnish part of the 2nd French Armored Division for a parade from the Etoile to the Place de la Concorde; and through General Koenig, who was also in the capital as the de Gaullist-appointed military governor, de Gaulle invited Gerow and his staff to participate, together with one American officer and twenty men and a like number of British.108

Gerow was hardly ready to comply. Although the situation was “quiet in main Paris area except some sniping,” groups of isolated Germans southwest of Paris near Meudon and Clamart, in the eastern part near Vincennes and Montreuil, and north of Paris near Montmorency and le Bourget claimed exemption from Choltitz’ surrender terms. In addition to these forces, another group still held the Bois de Boulogne.

General von Choltitz shortly after his capitulation

High-ranking German prisoners in the Hôtel Majestic

Furthermore, Paris posed serious problems of control, both with regard to the civilian population and to the troops, particularly because of the danger that the liberation hysteria might spread to the soldiers. The thought of a German air attack on a city with unenforced blackout rules and inadequate antiaircraft defenses hardly added to Gerow’s peace of mind. The Germans north and east of the city were capable of counterattacking. Feeling that the city was still not properly secure, anticipating trouble if ceremonial formations were held, and wishing the troops combat-ready for any emergency, Gerow ordered Leclerc to maintain contact and pursue the Germans north of the capital.109

Leclerc replied that he could do so only with part of his forces, for he was furnishing troops for de Gaulle’s official entry. Acknowledging Gerow as his military chief, Leclerc explained that de Gaulle was the head of the French state.110 Profoundly disturbed because the de Gaulle-Leclerc chain of command ignored the Allied command structure, Gerow wrote Leclerc a sharp note:–

You are operating under my direct command and will not accept orders from any other source. I understand you have been directed by General de Gaulle to parade your troops this afternoon at 1400 hours. You will disregard those orders and continue on the present mission assigned you of clearing up all resistance in Paris and environs within your zone of action.

Your command will not participate in the parade this afternoon or at any other time except on orders signed by me personally.

To keep the record straight, Gerow informed Hodges that he had “directed General Leclerc to disregard those orders [of de Gaulle] and carry out his assigned mission of clearing the Paris area.”111

Some members of Leclerc’s staff were purportedly “furious at being diverted from operations but say Le Clerq has been given orders and [there is] nothing they can do about [it].” They were sure that the parade would “get the French Division so tangled up that they will be useless for an emergency operation for at least 12 hours if not more.”112

Torn by conflicting loyalties, Leclerc appealed to de Gaulle for a decision. To an American present, de Gaulle supposedly said, “I have given you LeClerc; surely I can have him back for a moment, can’t I?”113

Although Barton suggested that Gerow might cut off Leclerc’s gasoline, supplies, and money, Gerow felt that it would have been unwise, as he later wrote, “to attempt to stop the parade by the use of U.S. troops, so the only action I took was to direct that all U.S. troops be taken off the streets and held in readiness to put down any disturbance should one occur.”114

Gerow’s concern was not farfetched. When Hitler learned that Allied troops were entering the French capital, he asked whether Paris was burning,

General de Gaulle. At his left is General Koenig, behind them, General Leclerc.

“Brennt Paris?” Answered in the negative, Hitler ordered long-range artillery, V-weapons, and air to destroy the city. Supposedly contrary to Model’s wish, Speidel and Choltitz later claimed to have hampered the execution of this order.115

Scattered shooting and some disorder accompanied de Gaulle’s triumphal entry of 26 August. Whether German soldiers and sympathizers, overzealous FFI members, or careless French troops were responsible was unknown, but Gerow curtly ordered Leclerc to “stop indiscriminate firing now occurring on streets of Paris.” Ten minutes later, Leclerc ordered all individual arms taken from his enlisted men and placed under strict guard. Shortly thereafter, in an unrelated act, 2,600 Germans came out of the Bois de Boulogne with their hands up. They might have instead shelled the city during the parade. Frightened by what might have happened, de Gaulle and Koenig later expressed regrets for having insisted on a parade and agreed to cooperate in the future with the American command.116

Meanwhile, part of Leclerc’s division had, in compliance with Gerow’s instructions, pushed toward Aubervilliers and St. Denis on 26 August, and two days later, after a three-hour battle with elements of the 348th Division (recently arrived from the Pas-de-Calais), the French took le Bourget and the airfield. Some French units seized Montmorency on 29 August, while others cleared the loop of the Seine west of Paris from Versailles to Gennevilliers and took into custody isolated enemy groups that had refused to surrender to the FFI.117

At the same time, the 4th Division had established Seine River bridgeheads near Corbeil on 25 August, had cleared the eastern part of Paris, and after assembling in the Bois de Vincennes, began on the afternoon of 27 August to advance toward the northeast. Two days later the troops were far beyond the outermost limits of Paris.118

All the corps objectives, in fact, had been reached “well outside Paris limits” by 27 August.119 To continue its attack

eastward, V Corps released the French division, retained command of the 4th Division, and received the 28th Infantry and 5th Armored Divisions.

Developments leading to the release of the French division began on 26 August, when General de Gaulle wrote General Eisenhower to thank him for assigning Leclerc the mission of liberating Paris. He also mentioned that although Paris was “in the best possible order after all that has happened,” he considered it “absolutely necessary to leave [the division] here for the moment.”120 Planning a visit to Paris on 27 August to confer with de Gaulle on this and other matters and “to show that the Allies had taken part in the liberation,” General Eisenhower invited General Montgomery to accompany him. When Montgomery declined on the ground that he was too busy, Eisenhower and Bradley went to Paris without him.121 At that time de Gaulle “expressed anxiety about conditions in Paris” and asked that two U.S. divisions be put at his disposal to give a show of force and establish his position. Since General Gerow had recommended that Leclerc be retained in Paris to maintain order, General Eisenhower, who earlier had thought of using Leclerc’s division for occupation duty in the capital, agreed to station the French division in Paris “for the time being.” To give de Gaulle his show of force and at the same time make clear that de Gaulle had received Paris by the grace of God and the strength of Allied arms, Eisenhower planned to parade an American division in combat formation through Paris on its way to the front.122

Ostensibly a ceremony but in reality a tactical maneuver designed as a march to the front, the parade would exhibit American strength in the French capital and get the division through the city—a serious problem because of traffic congestion—to relieve Leclerc’s division.123 While the 5th Armored Division assembled near Versailles for its forthcoming commitment, General Cota led the 28th Division down the Champs Elysées on 29 August and through the city to the northern outskirts and beyond in a splendid parade reviewed by Bradley, Gerow, de Gaulle, Koenig, and Leclerc from an improvised stand, a Bailey bridge upside down.124