Chapter 2: The XII Corps Crossing of the Moselle, 5–30 September

The XII Corps Plan1

The successful coup de main by Combat Command A, 4th Armored Division, at Commercy on 31 August and the establishment of a bridgehead east of the Meuse placed the XII Corps in position to continue the advance toward the Moselle River and Nancy. (Map VII) Thus far the retreating Germans had offered no real opposition, nor were there any signs that the Wehrmacht shortly would stand and fight. During the past sixteen days the XII Corps had made an eastward advance of 250 miles. The 80th Infantry Division was coming up fast on the left of CCA and on 1 September crossed into the bridgehead. On the same day CCB, earlier slowed down by the necessity of repairing bridges over the Marne, crossed the Meuse River and took position south of the 80th Division and CCA. On 2 September the bulk of McBride’s 80th Division relieved CCA in the Commercy bridgehead, while the left-wing regiment, the 319th, crossed the river at St. Mihiel farther to the north. The 35th Infantry Division remained behind the rest of the XII Corps, guarding the right flank of the Third Army, and so far as General Eddy knew he had to make his future plans on the basis of one infantry and one armored division.

The quick successes won by speed and surprise in earlier river crossing operations prompted General Eddy to consider using the 4th Armored Division in a surprise attack at the Moselle, with the infantry following. Neither

General Wood, the armored commander, nor General McBride, the infantry commander, looked with favor on such a plan.2 They reasoned that the Moselle presented a more difficult military problem than any river yet encountered, that the enemy strength and dispositions were unknown, and that the armor should not be risked in such a venture but rather conserved to exploit a bridgehead won by the infantry.

Actually, any planning for a surprise crossing by the armor was somewhat academic in view of the gasoline shortage which paralyzed the XII Corps, just as it did the XX Corps, waiting to cross the Moselle in the north. Fortunately the XII Corps had overrun a number of enemy rail yards. After scouring the area the corps G-4 found enough loaded tank cars to augment the limited gasoline issue and so allow the corps to concentrate east of the Meuse River. First call on the gasoline available was given to the armored patrols and the corps cavalry. But on the afternoon of 2 September even the armored reconnaissance elements were forced to halt, with fuel for only twenty miles left in their gas tanks. The XII Corps was immobilized.

General Patton visited the XII Corps commander on 3 September and with his customary optimism launched into a discussion of methods for attacking the West Wall, many miles beyond the Moselle. There was reason for optimism. Gasoline was already on its way to the Third Army front and the XII Corps could prepare to continue the advance east. That night the 4th Armored Division received 8,000 gallons as a token installment, and on the following day enough gasoline arrived in the Commercy area to permit resumption of the forward movement.

In midafternoon on 4 September, General Eddy outlined his general scheme of maneuver.3 He had decided to commit one regimental combat team of his only available infantry division in a reconnaissance in force, such as had been so successful at the Marne and the Meuse. This first plan for negotiating the Moselle barrier and capturing Nancy turned on a quick thrust across the river north of Nancy. One regimental combat team of the 80th Division (the 317th Infantry and its attachments) was ordered to establish a bridgehead in the vicinity of Pont-â-Mousson, a crossing site since the days of the Romans. Through this bridgehead CCA, reinforced by a battalion of the 318th Infantry, was to make a wide sweep, circling to the south and attacking Nancy from

Maj. Gen. Manton S. Eddy, XII Corps Commander

the east. The 319th Infantry had the mission of securing a bridgehead at Toul, where the Moselle River made its wide loop to the west, and attacking east toward Nancy in conjunction with the envelopment by the armor. The 80th Division reserve, the 318th Infantry (-), was designated by General McBride to force a “limited bridgehead” in the center of the division zone, by crossing east of the Belleville–Marbache sector. No specific time schedule was set for the execution of this corps maneuver, but even as orders were being drafted at the XII Corps headquarters the 317th was on the march to test the enemy strength at the Moselle line.

The Assault at Pont-à-Mousson

During the late afternoon of 4 September the 317th Infantry (Col. A. D. Cameron) moved along the Flirey–Pont-à-Mousson road toward the Moselle. (Map 2) There was no time for daylight reconnaissance across the river, and indeed very little was known of the terrain on the west bank from which the crossing attempt was slated to be made that same night. Emphasis now was on speed—hurry to the river and hurry across—the tactic which had kept the retreating Germans punch drunk for days past. The enemy, however, had used his respite to dig in on the east bank of the river and there establish a consolidated position which by this time extended from a point opposite Pagny-sur-Moselle south to Millery. The 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division, recently hurried to France from the Italian front and still clad in tropical uniforms, held the greater part of this sector. It could be given some help by elements of the 92nd Luftwaffe Field Regiment which were deployed on the left of the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division opposite Dieulouard. The 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division (Generalmajor Hans Hecker) was an old and battle-tested Wehrmacht unit. Its morale was high and its ranks nearly full. The artillery regiment was intact, but much of the motorized equipment being of Italian make was only passable. The division engineers and the organic tank battalion, which normally characterized this type of division, had not yet arrived from Italy. The 92nd Luftwaffe Field Regiment was a temporary training regiment that had been hastily collected from antiaircraft gunners and Luftwaffe replacements stationed in and around Nancy.

Two days before, the Germans in this sector had been alerted to the threat of a crossing attempt by the activity of American cavalry in the vicinity of Pont-à-Mousson. In addition, enemy observers on Mousson Hill (382),

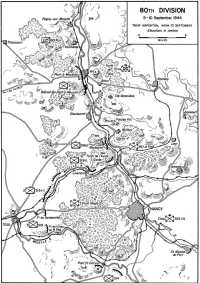

Map 2: 80th Division, 5–10 September 1944

Ste. Geneviève (382), and the Falaise (373) were able to watch every movement of the 317th Infantry as it advanced along the Flirey road. The strength and location of the German force east of the Moselle were unknown to the Americans. Reports from FFI (French Forces of the Interior) agents, whose sources of information were becoming more unreliable as the Allied advance reached the 1914 boundaries of France, and from cavalry patrols operating west of the Moselle, indicated that the Germans were not in sufficient strength to make a stand on the east bank. These reports, coupled with the optimism engendered by the speed of the American advance in August, prompted the XII Corps G-2 to advise the 80th Division commander that there was nothing much across the river.4

In the early evening the 317th Infantry arrived in assembly areas on the wooded bluffs looking down on the Moselle. Patrols, working in darkness, discovered a possible crossing site near Pagny-sur-Moselle far over on the north flank, another south of Vandières, and a third in the vicinity of Dieulouard. The situation in front of the 317th was still obscure, and about 2200 General McBride decided not to risk a night crossing but instead to try a surprise attack on the following morning. The area across the Moselle in which the 317th Infantry expected to establish a bridgehead was dominated by Mousson Hill, rising sharply east of the ancient town of Pont-à-Mousson, and by Hill 358, three thousand yards north of Mousson Hill. Colonel Cameron gathered his battalion commanders shortly before midnight and outlined a plan of attack for the next morning based on the seizure of the two commanding hills. The 1st Battalion, on the right, was ordered to begin an assault boat crossing east of Blénod-lès-Pont-à-Mousson at 0930 on 5 September, swing south of Atton toward the Forét de Facq, reorganize there in the woods, and then attack straight to the west and take Mousson Hill from the rear. At the same hour the 2nd Battalion, farther to the north, was scheduled to ford the Moselle at the Pagny site, move directly east toward Hill 385, and then attack south along the ridge line and seize Hill 358. The two hills were about 6,500 yards apart. The 3rd Battalion, in reserve, was to assemble behind the 1st Battalion and follow the latter across the river once a footing was secured. Colonel Cameron had been assured of air support and seems to have expected that the 80th Division artillery would fire concentrations on the regimental objectives before the infantry assault. Actually, the time necessary to effect coordination between

the infantry, artillery, and air was lacking. On 5 September the XIX TAC turned its entire striking power against the Brittany ports, sending no planes to the Moselle front. Artillery preparation for the 317th assault was fired only by the 313th Field Artillery Battalion on the right in direct support of the 1st Battalion.5

At daylight on 5 September—a bright, clear day—the assault battalions moved from the cover of the tree line on the western bluffs and down toward the Moselle. The 2nd Battalion had progressed some distance along a draw south of Pagny-sur-Moselle when suddenly it was struck by artillery and mortar fire coming in from positions dug on the forward slope across the river. So intense and accurate was this fire that the battalion was paralyzed—nor did it again move forward. On the right the 1st Battalion reached Blénod and reorganized for the assault in the shelter of the houses bordering the river flats. In front of Blénod a small canal ran parallel to the river. The battalion found a partially demolished footbridge and crossed the canal without difficulty; it moved only about two hundred yards in the direction of the river when enemy machine guns began to sweep the flats from the north. Completely in the open, the 1st Battalion reorganized and tried to move forward again. This time heavy and accurate mortar fire broke in the American ranks, destroying most of the rubber boats intended for the river crossing. About 1500 the battalion fell back to the line of the canal and there took shelter behind a railroad embankment. The division commander made another attempt to put troops across and ordered the 3rd Battalion to cross near Pont-à-Mousson by whatever means were at hand. However, no ford could be found and the battalion withdrew.

Late in the evening the 317th regrouped for another effort, a night attack in which all three battalions would take part. To the left the 2nd Battalion marched south to Vandiéres, where a possible crossing site had been reported. The 3rd Battalion, in the center, prepared to take Mousson Hill with a frontal assault across the river. The 1st Battalion moved across the canal to retrace its steps east of Blénod. But again the two exterior battalions were driven back from the river. The Germans on the opposite bank allowed the 1st Battalion to reach the flats between the canal and the river and then opened fire. Casualties were heavy and the badly shaken troops fell back to Blénod where the

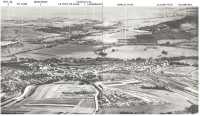

Frontal attack across the Moselle. The 3rd Battalion, 317th Infantry, prepares to take Mousson Hill, which may be seen across the river

survivors took refuge in a concrete factory building. Shortly after midnight the 2nd Battalion began crossing the canal at Vandiéres using some barges found tied to the bank. Very slowly, in the pitch black, the rifle companies formed in a single file and began groping their way across the open space between the canal and the river preparatory to forming in line for the final crossing assault. The battalion was swung out in a wide loop when, about 0415, the silence was broken by a command shouted in German. This single incident saved most of the infantry, for they fell in their places a split second before the German machine guns across the river opened an intense grazing fire. Flares and mortar shells followed, pinning the troops where they lay. One company close to the canal was able to withdraw, but the rest of the battalion was not pulled out of its precarious position until the following afternoon.

The 3rd Battalion had greater initial success in the central crossing attempt at Pont-à-Mousson. The 305th Engineer Combat Battalion, ferrying the infantry across the Moselle in rubber assault boats, landed about four platoons of infantry from I and L Companies on the enemy bank, although casualties

were heavy and thirty-eight of the sixty-four assault boats were lost. The infantry dug in about one hundred yards east of the river, and there they were held by machine gun and mortar fire as soon as day broke. The available troops of the 2nd Battalion now were ordered to march to Pont-à-Mousson and reinforce the 3rd, while smoke was put on the opposite bank to cover the thin American line. But before aid could be crossed the German infantry left their foxholes along the river bank and closed in with bayonets, grenades, and machine pistols. The American position was wiped out by 1100, with 160 officers and men missing.6

Further river crossing attempts at this point were canceled by the XII Corps commander, and the 317th Infantry began a slow, piece-meal withdrawal into the woods west of Pont-à-Mousson. Insufficient time for daylight reconnaissance, a daytime attack, the decision to dispense with an artillery preparation in order to gain tactical surprise, lack of coordination, and intelligence estimates that minimized the enemy strength had all contributed to the initial failure to bridge the Moselle. But the most important explanation of this reverse must be found in the fact that the enemy held ground superbly adapted to the defensive and that he was prepared to fight for it.

The 80th Infantry Division Advance East of Toul

The remainder of the 80th Infantry Division also met toughening opposition and more difficult terrain as it drove east out of the Commercy bridgehead. West of Nancy the Moselle makes a wide loop, swinging out as far as Toul, one of the most historic of French fortress cities. In the XII Corps plan it was intended for the 80th to attack astride the northern segment of the Moselle River loop. When the 317th Infantry began the march forward on 4 September, two battalions of the 318th Infantry, forming the division center, moved up along the north bank of the Moselle toward Marbache, about three miles south of Dieulouard. One battalion of the 318th Infantry was attached to CCA, 4th Armored Division, which assembled behind the 317th Infantry ready to cross the river when a bridgehead was established. Late on 4 September the 319th Infantry, forming the right wing of the division advance, forced its way across the Moselle at the point where it touched on the eastern suburbs of Toul, and drove a re-entrant into the wide, enemy-held salient formed by

the river loop.7 The terrain at the crossing site gave no advantage to the defender; therefore the Germans did not react in force.

Next morning the two regiments attacking astride the Moselle began a protracted battle to close up alongside the 317th Infantry, already at the main north-south river channel. In front of the 80th Division center the main body of the 92nd Luftwaffe Field Regiment was disposed on the heavily wooded hills and ridges surrounding Marbache. Despite its recent conversion to infantry the 92nd proved to be an able combat outfit. When the 3rd Battalion of the 318th Infantry attacked to take Hill 326, which commanded Marbache and the road running east to the Moselle, the Germans contested every step through the woods. Progress was slow, but on the morning of 6 September the battalion was in position for the final assault against Hill 326. American guns sprayed the crest with high explosive and in the middle of the afternoon the 3rd Battalion took the position. The enemy left seventy-five dead and wounded on the hilltop. The attackers also lost heavily and the battalion commander, Lt. Col. J. B. Snowden II, was mortally wounded. He refused to leave his men and died the following morning. On the right, the 2nd Battalion of the 318th made a predawn attack on 6 September against a battalion of the 92nd Luftwaffe Field Regiment entrenched on the west edge of the Forêt de l’Avant Garde. Although the first enemy position was quickly overrun after tanks and tank destroyers swept the tree line with fire, the Germans fought stubbornly as they were forced back through the woods, their retreat covered by twin 20-mm. antiaircraft guns and artillery firing from east of the river. A coordinated attack put the 2nd Battalion astride Hill 356 on 7 September. Now the 318th Infantry commanded the high ground north and south of Marbache, as well as the roads defiling through the town from the west, and on the night of 7–8 September patrols entered and outposted Marbache. Later, German fire swept the area and the American hold was broken by a counterattack.

The drive out of the 319th bridgehead went more slowly than the attack north of the river. Here, in the Moselle salient, the 3rd Parachute Replacement Regiment held an outpost line barring the western approaches to Nancy. This German position lay about ten miles west of that strategic city, running north and south across the narrow tip of the Moselle tongue and anchored at the flanks by two old French forts which had once formed a part of the Toul fortress system. The northernmost work, at Gondreville, fell to the 3rd Battalion

Fort Villey-le Sec

of the 319th on 5 September, the day on which the battalion began to wedge its way into the river salient. But Fort Villey-le Sec, occupying the high ground on the southern flank, was stubbornly defended by a full battalion of the 3rd Parachute and proved tough to crack. The fort was surrounded by a deep, dry moat faced with stone. The inner works had reinforced concrete walls and ceilings, five feet thick, and steel cupolas housing automatic weapons and at least one 75-mm. gun. In the woods surrounding the fort the Germans had dug in machine guns, strung wire, and emplaced a few artillery pieces. A preliminary attack on 6 September8 reached the fort but was broken up by cross fire from the German machine gun emplacements in the woods to the south. Company K led off a coordinated assault on the next day, accompanied by tanks and supported by fire from two towed tank destroyers. Lt. Col. Elliott B. Cheston, commanding officer of the 3rd Battalion, led his men up to the moat, firing tracers from his submachine gun to designate targets for the tanks.9 At the edge of the moat the infantry tried to force an entry, while the tanks beside them fired at the enemy embrasures. But the American assault failed to cross the moat: the tanks were forced to withdraw in the face of heavy antitank fire, and the infantry were beaten back by automatic fire and hand grenades pitched out of the port holes. Fort Villey-le Sec finally was occupied on 10 September when the German garrison withdrew toward Nancy.

The Germans launched a last series of counterattacks in the 80th Division zone north of the river on 8 and 9 September, using troops from the 553rd VG Division to reinforce the 92nd Luftwaffe Field Regiment. The recapture of Marbache was followed by sorties at Liverdun, where the 3rd Battalion, 318th Infantry, was attempting to clear the north bank of the Moselle bend. This last flurry, apparently a rear guard action, soon was ended and by 10 September most of the enemy had withdrawn across the north-south channel of the Moselle or had fallen back toward Nancy.

The XII Corps Returns to the Attack

General Patton’s order of 5 September, directing the XII Corps to cross the Moselle, seize Nancy, and prepare to continue the advance as far as Mannheim

and the Rhine River still stood.10 Even while the 317th Infantry was engaged in the last-gasp attempt to cross the river at Pont-à-Mousson, General Eddy was considering new ways and means for carrying out the XII Corps mission. For a brief period on 6 September the corps commander thought of throwing in CCA, 4th Armored Division, to help the 317th, but after conversation with General Wood the idea was abandoned and General Eddy ordered the crossing attempt halted. On this date the corps commander still expected to make a major crossing in the 80th Division zone and wrote in his diary: “This time we will make sure it goes through.”

Meanwhile the danger of a German thrust against the exposed and extended south flank of the XII Corps, which had caused General Eddy considerable concern, diminished day by day. The Seventh Army drive north along the Rhone Valley was pinching the retreating enemy, who now appeared to be more concerned with avoiding entrapment between the two American armies than with any counterattack operations aimed at the Third Army flank. The 2nd Cavalry Group, scouting toward the Madon River southeast of the XII Corps, brushed against German columns retreating hurriedly to the east. On 6 September the 42nd Cavalry Squadron and 696th Field Artillery Battalion blocked off one such column on the road between Xirocourt and Ceintrey, killed 151 Germans, captured 178, and destroyed 30 vehicles. On the following day the cavalry were on the Madon River and held a heavy bridge, still intact. In addition, the XV Corps had been returned to the Third Army and would shortly appear to take over the mission of protecting the open south flank. This meant that the 35th Infantry Division could be brought forward and used in mounting the new XII Corps attack.

On 7 September General Eddy mapped out a tentative new plan, much like his original scheme but this time shifting the main effort so as to use the 35th Infantry Division and the entire 4th Armored Division in a wide envelopment starting south of the existing corps front and swinging across the Moselle and Meurthe Rivers to gain the rear of Nancy. Once this limited-objective attack had been concluded, General Eddy expected to use his armor to spearhead a further advance toward the north and east, as part of the larger Third Army plan. Reaction to the proposed maneuver at headquarters of the 4th Armored Division was distinctly adverse; late in the afternoon General Wood phoned Col. Ralph Canine, the XII Corps chief of staff, and reported: “My people are appalled at this thing.” He reasoned that beyond the Madon

River the armor would become involved in negotiating a whole series of watercourses, the Moselle, the Mortagne, the Meurthe, and the Marne-Rhin Canal, not to mention various small but impeding tributaries, before the rear of Nancy could be reached. General Wood pointed out that the advance on the southern flank would be “a terrific problem” even without enemy resistance. He urged that his division be allowed to make its attack in the north, where CCA was in position to knife in alongside the projected XX Corps crossing site and where the only immediate natural obstacle was the Moselle River.11 General Eddy, however, regarded the Moselle headwaters as less difficult obstacles than the main river north of Nancy. Besides, the terrain in the north gave the enemy better observation than did that in the south. Reports coming in from the corps cavalry were building up a picture of German withdrawal south of Nancy. On the other hand it seemed likely that the enemy was still deployed in force opposite the XII Corps left. The solution finally adopted was this. The 35th Infantry Division would make the envelopment south of Nancy, and CCB, 4th Armored Division, at the moment deployed on the corps right flank in the neighborhood of Vaucouleurs, would add the armored impetus necessary to the sweep. The 80th Infantry Division would then be committed in the Moselle sector north of Nancy as the enemy attention switched south, and the combined corps effort would lead to a double envelopment of the initial objective, the city of Nancy. CCA, in corps reserve, would be available to exploit a crossing on either flank.

On 9 September the corps commander set 0500, 11 September, as H Hour for the attack on the south. The 35th Infantry Division was moving up into line, adequate stocks of gasoline were available, and all fuel tanks and auxiliary cans were full. The cavalry had established a screen along the Madon River and early that morning had begun a dash, fruitless as it proved, to seize the Moselle bridges between Gripport and Flavigny where the 35th expected to cross. On 10 September the corps heavy artillery moved south to support the initial attack. North of the XII Corps the sound of gunfire signaled the beginning of the attack to establish a bridgehead in the XX Corps zone.

The XII Corps Crosses the Moselle South of Nancy

On the morning of 10 September the 35th Infantry Division moved forward under scattered shellbursts to occupy the high ground west of the Moselle.

Two regiments, the 137th Infantry on the right and the 134th Infantry on the left, were designated to make the crossing set for the following day. Engineer support would be given by the 1135th Engineer Combat Group (Col. Charles Keller). The north wing of the division advance rested on the Moselle River loop and the southern wing swung eastward in line with the town of Vézelise. (Map VIII) The enemy was not in evidence and limited his opposition to artillery fire from guns earlier emplaced east of the Moselle. Shortly after noon the tempo of the advance accelerated when word reached the 35th Division headquarters from the 134th that there was a bridge, mined but still intact, on the Moselle near Flavigny.12 General Baade gave Col. B. B. Miltonberger, commanding the 134th Infantry, permission to push for this bridge. Colonel Miltonberger passed this information to his 2nd Battalion, which reached the bridge after a sharp skirmish with German infantry and armored cars west of the river in the Moulin Bois, and about 1900 began the crossing. Three hours later most of the battalion was dug in on the east bank of the Moselle near the bridge exit. But for some reason the tank destroyers, ordered to hurry across the bridge and support the American infantry, did not arrive. Up to this point fortune had favored the Americans and the enemy had failed to react in any force. About midnight German planes dropped bombs near the bridge but without making a hit. Then the German field guns took over the job and with a few accurate salvos smashed the structure, leaving the 2nd Battalion (Maj. F. C. Roecker, Jr.) stranded on the enemy bank. For two and a half hours enemy shells fell unremittingly on the American position and casualties mounted. At last the German counterattack, delivered by infantry from the 104th Panzer Grenadier Regiment of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division and paced by tanks, swept in on the decimated and shaken battalion. Losses inflicted on the Americans were very high.13 Those who could escaped through the night and swam or waded back to the west bank.

The reverse suffered by the 2nd Battalion temporarily checked the 134th Infantry attack. But the coordinated attack by Col. Robert Sears’ 137th Infantry, delivered as originally planned on the morning of 11 September, secured a toehold across the river. After firing for over an hour in a feint at an area five miles to the north of the 137th Infantry crossing site set at Crévéchamps, the entire 35th Division artillery, reinforced by heavier guns from the XII Corps,

laid a half-hour barrage across the river in front of the 137th. Shortly after daylight the first waves of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions were across the Moselle, but here they were stopped by fire from concrete emplacements manned by four companies of the 104th Panzer Grenadier Regiment. The American infantry dug shallow holes and held on grimly while fire swept back and forth along the bank, denying any movement and preventing reinforcement. Late in the afternoon the 1st Battalion was committed in a surprise attack to the south near Neuviller-sur-Moselle and put two companies across the river before nightfall. After dark the 1st Battalion pushed east to Lorey and General Baade ordered it to make contact with CCB, 4th Armored Division, which had crossed farther south during the day.

In the original XII Corps scheme of maneuver CCB (Brig. Gen. H. E. Dager) was to advance in two columns on the right of the 35th Infantry Division, the north column to cross the Moselle near Bayon, the south column to cross at Bainville-aux-Miroirs. Lunéville and Vic-sur-Seille were designated as objectives. When the armor attacked, on the morning of 11 September, the armored infantry leading the southern column became involved in a sharp fight in the town of Bainville-aux-Miroirs, were initially driven back from the river, but finally succeeded in crossing two companies. The northern column met less resistance in the Bayon sector. A platoon of tanks from the 8th Tank Battalion, led by 1st Lt. William Marshall, followed hard behind the infantry. At this point the main antitank obstacle was a steep-banked canal on the west side of the river channel. Although the German gunners had taken the American tanks under fire, Lieutenant Marshall proceeded to build his own causeway across the canal by firing into the banks until they caved into the water and then topping the earth with a ramp of rails and ties.14 Marshall’s platoon, followed by the rest of the 8th Tank Battalion, then successfully negotiated the four separate streams which here comprise the Moselle; bypassing Bayon, the left column of CCB seized the hills northwest of Brémoncourt which overlooked the 137th Infantry position.

During the night of 11–12 September the advance guard of the armor met the 1st Battalion of the 137th Infantry near Lorey. The engineers, meanwhile, had floated a 168-foot bridge over the Moselle at the Bayon site, and the remainder of CCB, with the 2nd Battalion of the 320th Infantry, started to move across into the bridgehead. The Germans made a desperate attempt to throw

Tank Crossing Canal near Bayon

American tank damaged by German fire. This tank of the 8th Tank Battalion was hit during the German counterattack to destroy the Bayon Bridge

the Americans back across the river, or at least to destroy the Bayon bridge, and early on 12 September sent a battalion through the outposts of the 8th Tank Battalion. This counterattack was suicidal. Tanks and infantry encircled the enemy detachment, killed many, and took about 150 prisoners. Meanwhile the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 137th Infantry fought their way out of the pocket at the river bank and during the morning swung south to join the main force. Tanks, tank destroyers, guns, and trucks by this time were pouring into the bridgehead. A few German tanks essayed a brief rear guard action east of Méhoncourt, but by midafternoon the remnants of the 104th Panzer Grenadier Regiment were in full retreat toward the Meurthe River, harassed by fighter-bombers sent over by XIX TAC and closely pursued by CCB and the 137th.

The 35th Division attack had been planned as a two-regiment maneuver. After the disastrous fight at Flavigny, however, the 134th Infantry took no further part in the battle for the crossing, becoming involved in holding the anchor point for the division left flank at Pont St. Vincent, where the Madon

River runs into the Moselle and a series of bridges funnel rail and highway traffic southwest from Nancy. On the west bank a French fort looks down on the town and bridges. One company of the 134th had been detailed to hold this key position and thus secure the north flank while the 35th Infantry Division launched the crossing attack on 11 September. About 0800 that morning the American garrison was surprised by two companies of German infantry which had crossed the river from the Nancy side, circled quietly to the woods north of the fort, and crept in close enough to breach the walls with bazooka fire. The attackers took some prisoners and for a while held a corner of the fort. About this time more Germans were seen entering the woods and word was relayed to the 35th Division headquarters, which ordered the 1st Battalion of the 134th to march to the aid of the American garrison. Friendly artillery soon neutralized the enemy assembly area in the woods and no further attempts were made to seize the fort. But this German threat had been successful in subtracting weight from the 35th Division assault at the Moselle.

The XII Corps Crosses the Moselle North of Nancy

The successful attack by CCB, 4th Armored Division, on 11 September and the seizure of a foothold across the Moselle in the Bayon sector, dictated a prompt effort to cross the Moselle north of Nancy and start the left hook required by the XII Corps plan of concentric attack. Furthermore, the XX Corps had achieved a crossing at Arnaville, just north of the zone selected for the thrust by the left wing of the XII Corps, and it might be expected that this would attract considerable German attention. On the afternoon of 11 September, therefore, General Eddy gave orders for the 80th Infantry Division to start the Moselle crossing the following morning.15

After the failure of the reconnaissance in force that the 317th Infantry had undertaken on 5–6 September, General McBride, his staff, and his regimental commanders laid plans for a carefully coordinated assault and adequate support in the next crossing attempt. A new crossing site was selected in the neighborhood of Dieulouard, about four miles south of Pont-à-Mousson. (Map IX) In the new plan the 317th Infantry again would be responsible for seizing the river crossing and securing a hold on the enemy bank, its initial objective to be the series of hills and ridges immediately east of Dieulouard. Once the

Long Tom mounted on Sherman tank chassis. This 155-mm. gun was one of many that concentrated on targets across the Moselle before the assault

317th was across, two battalions of the 318th Infantry (Col. H. D. McHugh) were slated to follow into the bridgehead, wheel north, and capture Mousson Hill and the surrounding heights. The 319th Infantry (Col. O. L. Davidson) was engaged astride the Moselle east of Toul; therefore General McBride could count on only five battalions. CCA, 4th Armored Division, assembled behind the 80th Infantry Division, was prepared to cross through the infantry bridgehead four hours after the heavy bridges were in and strike for Château-Salins, a strategic road and rail center some twenty-three miles east of Nancy. To give added weight to the armored drive the 1st Battalion, 318th Infantry, was motorized and attached to CCA. Engineer support for the 80th Infantry Division effort would be given by the 305th Engineer Combat Battalion (Lt. Col. A. E. McCollam), assigned the task of crossing the infantry assault force, and the 1117th Engineer Combat Group (Col. R. G. Lovett), designated to put in the heavy bridges and act as a combat reserve.

The initial attack by the 317th Infantry had shown that the Germans were well organized for defense in the Pont-à-Mousson sector, and it was probable

that this first American effort had alerted the enemy all along the river line in the 80th Infantry Division zone. Measures were therefore adopted to screen the direction of the new assault and assure at least some measure of tactical surprise. On 8 September patrols crossed the canal near Dieulouard and scouted as far as the river, selecting possible crossing sites and routes of approach. No further patrolling was allowed and all movement of troops or vehicles into the 317th area was prohibited. Each day the American artillery fired concentrations on the targets selected for special treatment on the day of the assault so as to forestall an enemy alert when the guns opened prior to H Hour. Counterbattery fire was laid on all known enemy gun positions but was none too successful. The winds generally blew toward the German lines, thus curtailing effective sound ranging, and the numerous hills and hollows east of the river offered flash defilade. Apparently the enemy interpreted this artillery activity as normal harassing and counterbattery work. No local reserves were moved into the Dieulouard sector and the daily German intelligence reports prior to 12 September concentrated exclusively on the signs of coming American attacks at Metz and south of Nancy.16

Although careful plans and preparations would increase the chances of a successful crossing, the Germans occupied a position so strengthened by the configuration of the ground that there was no easy route of penetration if they chose to defend. The heights of the Moselle Plateau, across the river from the 80th Infantry Division, were crowned by remains indicative of the historic military importance of the area. On Mousson Hill lay the vestiges of a medieval church-fortress, at Ste. Geneviève lines of Celtic earthworks could still be traced on the crest, and at Mount Toulon the ruins of a Roman fort were still evident enough to be shown on French General Staff maps.

The Moselle itself, as it winds through the Dieulouard sector, is no serious military barrier to any modern army. The average width of the river here is 150 feet, with a depth from 6 to 8 feet. Several fords are available for crossing infantry, but the river bottom is too muddy for tank going. East of Dieulouard the Moselle River and the Obrion Canal form two arms that wind around a flat, bare island, a little less than 2,000 yards across. A macadam road runs across this island and the approaches to fords and bridging sites, via the island, are good. Parallel to the western bank of the Moselle at this point is a barge canal, 50 feet wide and 5 feet deep, separated from the river by an 8-foot dyke

that rises abruptly between the two. North and south of the island the Moselle meanders through a wide flood plain covered by marsh grass and dotted by a few scattered trees. But once off the river flats infantry and armor advancing toward the east are faced with a series of abrupt ascents leading to the hills that crop out of the Moselle Plateau—Mousson Hill to the north, Hill 382 in the center, and the Falaise to the south. Numerous draws, gullies and low ridge lines lead back to the heights, but all of these avenues of approach are dominated by neighboring hills and afford excellent corridors for counterattacks directed down toward the river. This terrain limits tank maneuver, since the roads are often bounded by deep ditches on one side and cliffs or steep cuts on the other. Beyond the hill chain the ground to the northeast slopes gently into the Seille River basin, but any advance toward the southeast—that is, toward Château-Salins—must follow roads dominated by a second hill curtain at Mount St. Jean and Mount Toulon. In effect the enemy-held ground ahead of the 80th Infantry Division presented a tactical problem as difficult as any the Third Army would encounter in the course of the Lorraine Campaign.

As a preliminary to the 80th Infantry Division attack the IX Bomber Command sent fifty-eight medium bombers on 10 September to cut the bridge at Custines that spanned the Mauchère River and provided a quick route over which reinforcements might be moved from Nancy into the Dieulouard sector. The American bombers damaged the bridge, but it is problematical whether this hindered subsequent troop movement by the enemy. On the afternoon of 11 September other planes came over and began a feint at the Pont-à-Mousson area calculated to divert German attention from the intended crossing site. An air strike at Mousson Hill was successful and an artillery observer reported that “it looks like the top of the hill has been blown off”—an overly optimistic view as later events showed. The American artillery joined in this demonstration and continued to shell the Pont-à-Mousson sector during the night.

At midnight on 11 September the two assault battalions of the 317th Infantry moved through the trees covering the approaches to the Moselle and fell into line along the west bank of the barge canal. By 0400, H-hour for the crossing, the 3rd Battalion had traversed the island and was at the Obrion Canal, where a ford had been marked by the engineers. On the left, at a crossing site about 500 yards north of the island, the 2nd Battalion was hit by mortar fire and briefly disorganized while crossing the barge canal, but at H Hour the first wave was at the Moselle. Now nine battalions of field artillery

opened fire on the road south of Loisy, and fifty machine guns emplaced on the Bois de Cuite during previous nights and manned by engineers put a curtain of fire over the heads of the assault waves. Thirty rounds of white phosphorus set the town of Bezaumont ablaze and provided a marker to guide the infantry advance through the darkness. The 3rd Battalion forded the Obrion Canal and by 0530 had possession of its first objective, la Côte Pelée, south of Bezaumont. The 2nd Battalion waded across the Moselle or crossed in plywood boats and at 0800 was in position on the heights at Ste. Geneviéve.

Thus far the Germans had reacted only with occasional fire. Apparently the river line had been very weakly outposted and the high ground, seized by the 317th, was not occupied at all. A drizzling rain reduced visibility in front of the enemy OP’s (observation posts), and the moving barrage laid ahead of the attacking infantry probably knocked out the German communications net and dispersed local reserves. However, when the reserve battalion began to cross by a footbridge put in behind the 2nd Battalion the German gunners were on the target and succeeded in damaging the bridge. The engineers made repairs under fire and the 1st Battalion moved over the river to its objective, Hill 382, northeast of Bezaumont on the Ste. Geneviève Ridge. The arrival of the 1st Battalion between the 2nd and 3rd placed the 317th on its first objective, with a semi-organized front of some 3,000 yards. Just before noon the 318th Infantry (-) began crossing into the center of the bridgehead and took up positions on the reverse slope of Ste. Geneviève Ridge and west of Bezaumont. Later in the day the 318th Infantry tightened up the perimeter defenses of the bridgehead by road blocks near Ville-au-Val, Loisy, and Autreville-sur-Moselle. As night drew on the five American battalions dug in to await the inevitable counterattack.

All during the day the engineers had worked furiously to throw heavy bridging across the river and the canals. The original engineer plan provided that heavy bridge construction should be postponed until late on 12 September, when, it was expected, the German guns would be pulled back from direct ranging on the bridge sites. However, the speed and ease of the infantry advance during the morning led General McBride to order the heavy ponton companies immediately to work—a decision that had an important bearing on the events of the next day. By midnight of 12 September two companies of the 702nd Tank Battalion, the 313th Field Artillery Battalion (105 Howitzer), some antitank guns, and a few towed tank destroyers were in the bridgehead, the heavy weapons and vehicles being assembled in the dark –

close to the exit from the main ponton bridge—near a small cluster of houses known as le Pont de Mons.

Little sign of enemy activity had been seen during the day.17 As darkness settled, the German guns to the east began a sustained fire on the bridgehead, while enemy mortars methodically searched the reverse slopes on which the American infantry reserves lay. The 80th Infantry Division attack had struck a thinly manned sector of the First Army line. In front of the 80th extended the southern wing of the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division, rated by OKW as being capable of limited offensive operations (Kampfwert II), a rating usually given only the best German divisions on the Western Front since virtually none could be graded at this time as capable of sustaining an all-out attack (Kampfwert I). The rifle strength of the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division was still nearly complete, its artillery was good, and in addition it now had a complement of thirty-three assault guns—an unusual number for any German division at this stage of the war. Somewhat south of Bezaumont the sector of the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division joined that of the 553rd VG Division. On 12 September there was something of a gap between these two German divisions, covered only by an outpost line. The greater part of the 553rd VG Division was concentrated in and around Nancy, about ten air-line miles to the south of the 80th Division bridgehead. The left wing of the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division had been stripped to send reinforcements northward, where other elements of the 3rd were engaged alongside the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division in the attempt to erase the XX Corps bridgehead.18 Lacking local reserves in the Dieulouard sector the enemy had been unable to launch a prompt counterattack. But about 0100 on 13 September the Germans dealt the first blow at the 80th Infantry Division perimeter defenses. The initial counterattack was made by a battalion of the 29th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, reinforced by at least ten assault guns,19 which drove in on the road block north of Loisy held by F Company (Capt. Frank A. Williams) of the 318th. Captain Williams and his men fought bravely to hold the position until orders

came for the company to fall back to the south. The main German counterattack developed from the Forêt de Facq as a tank-infantry thrust aimed at rolling up the north flank of the bridgehead and destroying the American bridges. This force (later estimated as two battalions and fifteen tanks) took the village of Ste. Geneviève, swept over the end of the ridge which extended south of the village, captured Bezaumont, and began a final assault in company with the Loisy combat group to reach the bridge sites. The small detachments of the 317th Infantry outposting the north tip of the Ste. Geneviève Ridge were driven back into the 318th Infantry positions. Communications were destroyed and command posts overrun. At the command post of the 318th Infantry a sharp fight briefly halted the German attack, but the regimental commander, Col. Harry D. McHugh, was wounded, part of the regimental staff was captured, and about 120 officers and men were killed.

Little coordinated resistance was possible as the scrambled units of the 317th and 318th were forced back toward the bridges.20 Officers gathered small groups wherever they could locate a few men in the darkness, majors commanding platoons and captains commanding battalions. Near the bridge site the situation was further confused when American vehicles coming from across the river met the stream of trucks and infantry moving back toward the bridges. About 0500 a thin line of infantry firing from the ditches along the road between Loisy and the crossroad west of Bezaumont momentarily checked the enemy; but this position was quickly overrun by German tanks that left the ditches full of dead and wounded. However, the fight along the roadside had given time for Lt. Col. J. C. Golden, commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion, 318th Infantry, to gather enough men and tanks at le Pont de Mons to meet the final German assault. While the infantry fought from the houses, B Company, 702nd Tank Battalion, knocked out the leading enemy tanks and assault guns at ranges as close as two hundred yards. No Germans reached the bridges, although at one time the fight surged within a hundred yards of the eastern exits, where three companies from the 248th and 167th Engineer Combat Battalions defended the bridges with rifles and machine guns. The attack had spent itself, the German commander had no fresh troops to give the added impetus needed for the last few hundred yards, and with full daylight the attackers began to withdraw toward the north, harassed by

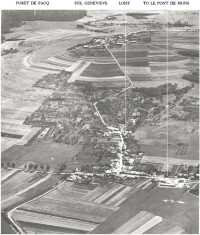

Dieulouard Bridgehead Area

[Image merged onto previous page]

shells from the 313th Field Artillery Battalion—the only American artillery in the bridgehead.

Meanwhile CCA, 4th Armored Division, had begun to cross into the bridgehead and the head of the armored column cut into the retreating enemy. By 0800 the advance guard had fought its way into Ste. Geneviève and the armor was rolling toward the east, leaving the American infantry to recover its lost ground and hold the bridgehead. The troops around le Pont de Mons were hastily reorganized and at 0930 General McBride gave the order to counterattack. Many of the enemy left in the wake of CCA were captured, and at no point could the Germans stand and hold. Company A, 702nd Tank Battalion, which led the 80th Division counterattack, lost five tanks, but the 80th regained Loisy, Bezaumont, and Ste. Geneviève. Two companies of the 317th had maintained their hold on Hill 382 throughout the night and at dawn on 13 September counterattacked and drove the enemy off the slopes. Infantry of the 317th also had repelled a number of sorties made against the outpost position at Landremont, the most advanced point reached the previous day. The 80th Division counterattack regained contact with these isolated positions and by the late afternoon of 13 September had restored the original bridgehead perimeter.

CCA, 4th Armored Division, Begins the Penetration

During the lull following the unsuccessful attack by the 317th Infantry at Pont-à-Mousson, CCA, 4th Armored Division (Colonel Clarke), lay in the rear areas of the XII Corps awaiting gasoline and further orders. The commander and staff of the 4th Armored Division were extremely anxious to continue the highly mobile operations that had characterized the work of the division in Brittany and across France, and they produced a new attack plan almost daily, most of which turned on the idea of a deep thrust by the entire 4th Armored north and east of Nancy. When the corps commander decided to execute a double envelopment, General Wood gave Colonel Clarke permission to choose his own crossing site on the north wing of the corps. The XX Corps attack to secure a crossing near Dornot, on 8 September, had prompted Colonel Clarke to suggest that CCA should cross the Moselle alongside the 5th Infantry Division. On 11 September the establishment of a bridgehead by the 5th Division, and the beginning of the XII Corps envelopment via the south wing, gave the opportunity General Wood and Colonel Clarke had

been waiting for. Plans were made for CCA to cross the Moselle the following day over bridges to be thrown across the river near Pagny-sur-Moselle, immediately south of the 5th Infantry bridgehead.21 On the night of 11 September the armored engineers moved down to the river with orders to put in a bridge before morning. Most of the steel treadway equipment had been given to CCB. Some large timbers and “I” beams were found at the site but these could not be manhandled into place. Finally the single bulldozer in use overturned and with this last bit of bad luck bridging attempts ceased. Colonel Clarke postponed further operations for twenty-four hours and sent a request to the corps headquarters for a Bailey bridge; but by this time the corps bridge parks were nearly exhausted, except for the large sections of Bailey equipment earmarked for future use at Nancy.22

In the interim the 80th Infantry Division made its quick, successful crossing at Dieulouard and on the afternoon of 12 September General Wood ordered CCA to cross through this bridgehead. Colonel Clarke dispatched D Troop, 25th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron (Capt. Charles Trover), to move to the bridgehead and establish liaison with the infantry. When Captain Trover and his armored cars arrived at the river the heavy bridges were already in place, but a regulating officer refused to allow the troop to cross.23 The main body of the combat command began the move to the river about 0400 on 13 September. By this time the Germans were counterattacking all along the bridgehead perimeter and were driving through the north flank of the 80th toward the bridges. Shortly after 0615 the regulating officer gave Captain Trover permission to cross; with this the troop rolled over the bridge and into the midst of the battle on the east bank. Troop D fought its way through the German infantry, crashed through Loisy, and headed up the heights toward Ste. Geneviève. There enemy self-propelled guns proved too heavy for the light armor and Captain Trover pulled his troop off the road and into defilade on the rear slopes, where he and his men awaited the rest of Colonel Clarke’s combat command.

Back on the west bank General Eddy was holding a council of war with the commanders of the 80th Infantry Division, the 4th Armored Division, and CCA. The bridgehead area had been drastically reduced, and the risk entailed in crossing CCA was obvious. General Eddy asked Colonel Clarke if there was sufficient space left for CCA to deploy on the east bank, assuring him that he would receive no blame if he decided against the venture. The CCA commander turned to ask the opinion of Lt. Col. Creighton W. Abrams, at this time commanding the 37th Tank Battalion and already marked in the division as a daring combat leader. Pointing across the river, Abrams laconically remarked: “That is the shortest way home.” Colonel Clarke, with the approval of the corps commander, ordered: “Get going!”24

Colonel Abrams immediately sent into the bridgehead the 37th Tank Battalion, comprising the bulk of the first of the three task forces making up the long armored column. Thus began a demonstration of daring armored tactics which the XII Corps commander later likened to Stuart’s ride around the Union Army in front of Richmond. The road net leading out of the bridgehead was good and generally hard surfaced. Along these roads the armored column rolled, punching to break through the crust of German defense positions and road blocks encircling the bridgehead and fighting for control of the twenty-two feet of highway surface which in effect constituted the “front” for the combat command.

The 37th Tank Battalion had driven the enemy out of Ste. Geneviève by 0800, though this advance had resulted in some sharp fighting, and the remainder of CCA began to cross the river. Covered on both flanks by a screening force of light tanks, Task Force “Abe” continued along the highway toward Château-Salins, marked generally as the initial objective for CCA. About 1615 the head of the three-hour-long column was south of Nomény, while some elements of the command were still crossing the Moselle bridges. Thus far the advance had been halted repeatedly by enemy road blocks, small German tank detachments, and antiaircraft gun emplacements. These were quickly knocked out by the 75-mm. guns on the leading medium tanks or were blasted by fire from the armored artillery following close behind the head of the column. The last phase of the day’s operations saw the beginning of the wheel to the southeast. The major part of the combat command coiled

for the night near Fresnes-en-Saulnois, only three miles from Château-Salins, after having “swept aside” enemy resistance in a penetration of some twenty miles. In this day of action CCA had lost only twelve dead and sixteen wounded. The damage inflicted on the enemy was very considerable: 354 prisoners had been taken; 12 tanks, 85 other vehicles, and 5 large-caliber guns had been captured or destroyed. The number of German dead and wounded is unknown, but must have been high.25

On the morning of 14 September CCA remained in laager waiting for the arrival of its trains, which had bivouacked during the night near Ste. Geneviève. Shortly after noon the division commander radioed Colonel Clarke and gave new orders. CCA would bypass Château-Salins and seize the high ground around Arracourt, north of the Marne-Rhin Canal, block any German move coming in from the east, and cut the escape routes from Nancy. In addition the combat command was to effect contact with CCB, coming up from the south, and use its bridge train at the Marne-Rhin Canal to help CCB, whose bridging equipment had been almost entirely expended on the supply route over the watercourses now behind it.

As on the previous day Task Force “Abe” led CCA, taking to the side roads and trails until the road center at Moyenvic was reached and then rolling south on the main highway. Now the armor was deep in enemy territory and the back areas offered good targets. Near Arracourt the American tanks caught up with columns of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, moving out of the First Army zone to reinforce the German lines southeast of Nancy. By the end of day they had taken 409 prisoners and destroyed or captured 26 armored vehicles, 136 other vehicles, and 10 88-mm. guns. An American air observer, flying over the combat command, was able to report “a path of destruction” clear to the canal. Again the losses sustained by CCA had been relatively slight: ten men killed, twenty-three wounded, and two medium tanks destroyed.26

CCA assembled in the Arracourt–Moncourt area on the night of 14 September and set up a perimeter defense facing east. One task force took position astride highway N-74, the main paved road running from Nancy, and began

snatching up small German detachments as they came down the highway serenely unaware that there were any Americans within miles. Colonel Clarke saw an opportunity to follow up the successes of the past two days by forcing an even deeper penetration straight to the east. He was in radio range of CCB and by midnight patrols from the two combat commands would meet at the Marne-Rhin Canal. The CCA commander therefore broached the matter by radio to General Wood: “Recommend capture Sarrebourg early tomorrow in order to get crossing over Canal [des Houillières de la Sarre] and thru lake region [east of Dieuze] while enemy is on the run.”

General Wood passed this proposal to the corps commander, who refused the desired permission, pointing out that such an advance would take CCA outside the XII Corps zone, which was projected northeast rather than due east, and that the main corps mission at the moment was to destroy the Germans in the Nancy sector and incidentally to open a main supply road for the Third Army across the Marne-Rhin Canal. In this particular case, as so often in the operations of the Third Army, the corps commander was forced to concern himself with the necessity of providing infantry support close in the wake of the armored penetration. The Third Army commander and his armored leaders, accustomed to envision sweeping tank movements, seldom gave much thought to this tactical consideration. As early as the afternoon of 13 September Colonel Clarke had urged that the 80th Division send infantry forward to clear the Germans out of the Forêt de Facq, which bordered on the CCA line of supply, and on the night of 14 September he strongly urged that the 80th Division “rush men to Lemoncourt to follow up the advantage gained.”

Back in the bridgehead, however, the infantry had been hit by counterattacks in considerable force on 14 September; every available rifleman was engaged in a bitter struggle to hold the ground already won and extend the bridgehead line out to the east and onto the last chain of hills, grouped around Mount Toulon and Mount St. Jean. On 15 September the situation in the 80th Division bridgehead had deteriorated so markedly that General Eddy ordered the CCA commander to release the 1st Battalion of the 318th Infantry, which had been attached to the combat command, and sent it back by truck to reinforce the 80th. Colonel Clarke dispatched a company of tanks to convoy the truck column and the following morning, after some sharp skirmishing along the road, the little task force arrived in the bridgehead—just in time to intervene in a fight then raging. CCA remained, as ordered, in the Arracourt

area, shooting up the Germans on the Nancy road and patrolling toward the Marne-Rhin Canal, where, late on 15 September, CCB effected a crossing.

The Envelopment Southeast of Nancy Continues

After CCB, 4th Armored Division, and the 35th Infantry Division had forced their way over the Moselle River on 11 and 12 September, the enveloping wing south of Nancy began to gain considerable momentum.27 The terrain between the Moselle and the Meurthe Rivers offered no natural obstacles to favor the defense; therefore, the few companies of the 553rd VG Division and 15th Panzer Grenadier Division that had opposed the Americans along the Moselle fell back precipitately to the cover of the Forêt de Vitrimont, which borders the north bank of the Meurthe hard by Lunéville.(Map VIII) On 13 September a gap developed on the east flank of the retreating enemy,28 and through this opening the American armor drove.

By the morning of 14 September the two columns of CCB had crossed the Meurthe at Damelevières and Mont-sur-Meurthe and were heading into the Forêt de Vitrimont. The enemy had not been given time to dig in and make any kind of stand. No real effort was made to hold the forest and only the muddy, narrow roads delayed the American tanks and supply trucks following. By that evening CCB had its left flank on the Marne-Rhin Canal near Dombasle and was astride the main road leading east into Lunéville. Some of the enemy fled across the canal toward Buissoncourt and Haraucourt; the rest fell back on Lunéville under cover of a thin screen of infantry and tanks. This important rail and road center was fast becoming a trap, since the 2nd Cavalry Group had crossed the Meurthe southeast of the city and was busily engaged in blocking the highways into Lunéville, destroying bridges, and shooting up traffic on the roads. Late that night patrols from CCA and CCB met near the canal, here completing the concentric envelopment of the Nancy-Moselle

position. What the 4th Armored Division columns had accomplished (Map X) was spectacular,29 and, as the German records show, exceedingly worrisome to the First Army; but the XII Corps would endure weeks of costly fighting before the area now rimmed by the routes of the armored columns could be occupied by the Americans.

While CCB made its sweep toward Lunéville the 35th Infantry Division moved up fast on the left flank of the armored columns. Early on 13 September General Baade committed his reserves, two battalions of the 320th Infantry (Col. B. A. Byrne), to exploit the 137th bridgehead at Lorey, swinging the 320th through and to the east of the 137th and then sending the two regiments abreast in an oblique advance toward the Meurthe River. (Map VIII) The enemy harassed the infantry columns with fire from roving artillery pieces and isolated mortar and machine gun positions but could do little more. The 104th Panzer Grenadier Regiment had been pulled back at right angles to the 553rd VG Division, which still held the Moselle north and south of Nancy, and the 35th Division attack hit directly at the weak joint between the two German units. About the middle of the morning the enemy artillery abruptly slackened its fire, apparently an indication of a general German withdrawal across the Meurthe River. By the evening of 14 September the two battalions of the 320th Infantry were on the enemy bank of the Meurthe, east of Rosières-aux-Salines, and the 737th Tank Battalion had patrols along the river at St. Nicolas-du-Pont, only six miles from Nancy.

On 15 September the entire southern wing of the XII Corps either crossed the Marne-Rhin Canal or closed along the near bank. On the right CCB began a fight for crossings at Maixe and Crévic, under orders from the division commander to push forward, hit the retreating Germans, and “cut them to pieces.” General Dager replied aggrievedly, “We are cutting them to pieces,” but ordered his combat command to spur on. At Maixe, on the right flank, the enemy made a determined stand, reinforced by artillery across the canal. Intensive counterbattery fire and smoke laid on the high ground north of the canal finally quieted the German guns, and at dark a platoon of armored infantry crossed the canal. Since the crossing at Crévic met little opposition the

tank units of the combat command were sent over at that point. General Dager had radioed word of the enemy concentration at Maixe to CCA, and the 37th Tank Battalion was sent down to strike the German rear; but when the 37th arrived on the morning of 16 September it found that the enemy had withdrawn from the Maixe sector during the night. This foray was not without result, however, for a tank company of the 37th Tank Battalion, detached en route to clear out the village of Courbesseaux, surprised a large force there, destroyed seven antiaircraft guns, and killed nearly two hundred enemy infantry. CCB assembled in the vicinity of Courbesseaux on 16 September and after a series of orders and counter-orders was told to attack north toward Nomény with the object of easing the pressure on the 80th Infantry Division. Although the main body of the 4th Armored Division was now concentrated north of the Marne-Rhin Canal, the small division reserve, CCR (Col. Wendell Blanchard), which was seldom used on independent combat command missions in 4th Armored practice, was dispatched to Lunéville on 16 September and took up positions in the northwest quarter of the city. Meanwhile the 42nd Cavalry Squadron, 2nd Cavalry Group, entered from the southeast.

On the left of CCB the two regiments of the 35th Division continued to move men and equipment across the Meurthe River and the Marne-Rhin Canal. By 0800 the 320th Infantry (minus the 2nd Battalion attached to CCB) was on the march toward Dombasle. The scattered units of the 553rd VG Division continued their retreat in front of the 320th Infantry, and in the afternoon the 1st Battalion of the 320th crossed the canal in a sharp attack30 and deployed in defensive positions on the bluffs north of Dombasle and Sommerviller, closely supported by the 216th Field Artillery Battalion firing interdiction on the roads behind the canal. In the sector northwest of Rosières-aux-Salines the 137th Infantry met a stubborn German rear guard, and an attempted assault boat crossing over the Meurthe in the vicinity of St. Nicolas-du-Pont was checked by concentrated mortar and machine gun fire.

The enemy began to stiffen on 16 September, holding where he could and even turning to counterattack. The 3rd Battalion, 320th Infantry, drove north toward Buissoncourt, but was slowed down by sharp skirmishes with the German rear guard. At dusk the battalion reached Buissoncourt, surrounded the village, and then made an assault that netted 115 prisoners from the

Men of 320th Infantry crossing canal near Dombasle

320th Infantry are supported by a tank which fires on village from across the canal

104th Replacement Battalion (15th Panzer Grenadier Division). During the night the 1st Battalion came up from the south and CCB released the 2nd Battalion, thus allowing the 320th Infantry to concentrate for a further drive northward.

The 137th Infantry effected crossings at the Meurthe and the canal during the morning of 16 September; the 2nd Battalion swung northwest in the direction of Nancy,31 and a company of the 1st Battalion secured the village of Varangéville. In the meantime the tank destroyers and tanks attached to the regiment crossed over the bridges in the 320th Infantry zone and hurried along the Meurthe valley to support the 2nd Battalion, now pushed out precariously on the left flank. Around noon a “Cub,” flying observation for the division artillery, spotted a large German formation about a mile away from the 2nd Battalion, which by this time was near the village of Chartreuse. The Germans, estimated to number at least 800 foot troops and some 16 tanks, were advancing in conventional attack formation, with a platoon of infantry accompanying each armored vehicle. Six battalions of American artillery opened very effective artillery fire, reinforced at closer range by the 105-mm. howitzers of the assault gun platoon, 737th Tank Battalion. This massed shelling broke the counterattack before it could reach the 2nd Battalion lines. The coup de grâce was delivered by A Company, 737th Tank Battalion, and B Company, 654th Tank Destroyer Battalion, which closed with the German tanks and knocked out at least eight of them. The success at Chartreuse placed the left wing of the 137th Infantry within two miles of Nancy and in position to continue the advance northward alongside the 134th Infantry, now pushing out to the northeast after the occupation of Nancy.32

Task Force Sebree Occupies Nancy—15 September

The decision to take Nancy by concentric rather than frontal attack had resulted from the consideration of two factors: the strength of the German

forces reported to be in and around the city, and a terrain which favored the defender. Unlike Metz, the other linchpin of the Moselle line, Nancy was not a fortified city. Its strength lay in the geographic features, like the Forêt de Haye and the heights of the Grand Couronné, which had made Nancy a natural bridgehead for centuries. French strategy had conceived of Nancy as a garrison center from which, in time of war, field armies would be deployed to defend the Lorraine bridgehead east of the Moselle and Meurthe Rivers. This policy had been adopted in reverse by the German conquerors, and in 1944 Nancy became a bridgehead facing west in which the 553rd VG Division, the 92nd Luftwaffe Field Regiment (attached to the 553rd on 9 September), and miscellaneous fortress, training, air force, and police units concentrated to halt the advance of the XII Corps. The most important natural barrier between the Americans and Nancy was the triangular massif of the Forêt de Haye. Through early September intelligence reports from the FFI gave repeated stories of large concentrations of enemy troops in the woods, of heavily mined roads, and of freshly dug field works, backed up by numerous antitank guns. The approaches to the Forêt de Haye were too well defended to permit reconnaissance by light armored elements; the extent of its tree covering likewise ruled out effective reconnaissance from the air. As a result the XII Corps commander was forced to make his plans with little knowledge of the strength or location of the enemy force concentrated west of Nancy. In the main, intelligence reports indicated that Nancy would be defended. On 9 September the FFI informed the XII Corps G-2 that large German forces were fortifying the Grand Couronné and that there were at least five thousand enemy troops and huge ammunition dumps in the Forêt de Haye. The FFI reports probably were fairly accurate, for on this same date General Blaskowitz, commanding Army Group G, ordered the First Army to hold Nancy at all costs as a sally port for the counterattack against the Third Army then in the planning stage.

General Eddy hoped to soften up the Germans in the Forêt de Haye and called for help from the air force. On 10 September the IX Bomber Command diverted seven groups of B-26’s from the Brittany targets and they bombed the forest—with indeterminate results. Two days later four groups of medium bombers made an attempt to knock out the German observation posts on the wooded heights. Again there was no way in which the results of the air effort could be measured; General Eddy wrote in his diary: “Nobody knows what is in the Forêt de Haye.”

On 12 September the corps commander gave the formal order for the XII Corps to “concentrate east of the Moselle River.” No immediate move was made to enter Nancy, although a provisional task force, commanded by Brig. Gen. Owen Summers, Assistant Division Commander, 80th Infantry Division, was organized from the 134th Infantry and the 319th Infantry for this purpose. At the same time word was sent to a French intelligence team, operating behind the German lines under the command of a Major Crinon, that the enemy signal cables leading into the Forêt de Haye from the east must be cut. This task was accomplished on the night of 13 September. A few hours earlier, however, Blaskowitz had given the First Army commander permission to evacuate Nancy, “except for a small bridgehead garrison in the west part of the city,” in order that the 553rd VG Division, already weakened by commitments on the flanks of the Nancy position, might be used in the concentration of forces with which it was hoped to erase the Dieulouard bridgehead.33 On the American side the situation in the 80th Division bridgehead had called General Summers and part of the 319th Infantry north.34 As a result the Nancy task force was reconstituted under Brig. Gen. E. B. Sebree, Assistant Division Commander, 35th Infantry Division. On the night of 14 September new intelligence from the French undercover agents indicated that the enemy had evacuated the Forêt de Haye. Next day Task Force Sebree, guided by three members of the Nancy FFI, marched down the Toul road and entered the city; one battalion of the 134th Infantry pushed straight through to the east edge, with no opposition. Nancy was now in the hands of the Third Army; it would become the army headquarters and the chief bridgehead for the main army supply routes leading into Lorraine. The decision

to isolate this important communications center by envelopment had paid good dividends, but the bulk of the Nancy garrison had escaped and would face the Third Army again.

The Battle for the Dieulouard Bridgehead

The news of the 80th Infantry Division attack on 12 September caused little concern in the higher echelons of the German command. But a considerable furor resulted at the First Army headquarters when, on the morning of 13 September, General Knobelsdorff received word that an American armored column had broken through the German force in the Dieulouard sector and was striking east. First, Knobelsdorff dispatched an infantry battalion, reinforced by assault guns and two batteries of antitank guns, to Bénicourt—apparently in the hope of stopping the American tanks on the main paved road leading to Nomény. (Map IX) At least a part of this task force was engaged by CCA, 4th Armored Division, in Bénicourt at midday and was beaten decisively. Next, the First Army commander sought permission from Blaskowitz to evacuate Nancy, since he reasoned that the Dieulouard bridgehead must be erased, even at the cost of endangering the south flank of the First Army. Blaskowitz gave grudging assent to General Knobelsdorff’s request and three infantry battalions moved north from Nancy on the evening of 13 September. At the same time Knobelsdorff dispatched two battalions of the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division from Metz as additional reinforcements for the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division, bolstering these battalions with elements of the ill-fated 106th Panzer Brigade which had only five operational tanks in the entire brigade.35

This move to reinforce the German troops containing the bridgehead, on the night of 13–14 September, required a ruthless weakening of the First Army line. Knobelsdorff had one division in army reserve, but this was the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division (Generalleutnant Eberhard Rodt) earmarked by Hitler himself as a part of the Fifth Panzer Army being formed for the proposed counteroffensive against the south flank of the Third Army. The 15th Panzer Grenadier Division had arrived piecemeal on the Western Front after ten months of continuous action in Italy. It had suffered heavy losses in Italy and from air attacks on the rail journey north; at this time it had about

50 percent of its normal combat strength. The organic tank battalion was en route from Italy, but the division had on hand about seventeen tanks and assault guns. Although understrength, the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division still was rated as a “limited attack” unit.

In reality the actual strength of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division was not available to Knobelsdorff, since the division was already moving by serial out of the First Army zone en route to join General der Panzertruppen Hasso von Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army farther south. The leading regiment, the 104th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, had become involved in the fight south of Nancy, where some of its rifle companies had been thrown in to cover the open flank of the 553rd VG Division. Other elements of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division had been pulled out of the Arnaville area and were passing through the rear areas of the First Army en route to Lunéville; during this journey they were set upon by CCA, 4th Armored Division. Although the First Army commander had strict orders to release the entire 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, he succeeded in halting the departure of the 115th Panzer Grenadier Regiment by making various excuses to his superiors, and this unit was added to the counterattack force being gathered to destroy the Dieulouard bridgehead.

General Hecker, the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division commander, did not wait for the concentration of the units being hurried to his sector but instead began a series of local counterattacks, committing each additional reinforcement as it arrived on the scene. In the early hours of 14 September the Germans struck at the 80th Infantry Division positions, using the tactics that had been so successful in the initial counterattacks the day before—tactics that would be employed with varying degrees of success throughout the battle in the bridgehead. The complex of hills, ridges, valleys, and ravines gave an obvious invitation to such counterattack. The early morning fogs rising from the Moselle River extended the protection offered by hours of darkness and gave the attacker time to maneuver into position and drive the attack home. The compartmentalization of the bridgehead into alternating sectors of high and low ground isolated the American detachments at outposts on road blocks and made them fair prey to attack in detail. German infantry were consistently able to win at least temporary success by attacking under the cover of darkness or fog, blinding the American outposts with flares, pinning them in position with automatic weapon fire, encircling and then sweeping over the position. Once the road block was destroyed or the outpost position driven

Loisy

in, the German tanks or assault guns took the lead, reinforced by larger infantry units gathered from assembly areas in the Forêt de Facq or behind the hills to the southeast. While the enemy assault troops drove down the roads and paths into the bridgehead, German guns and mortars placed intense fire on the hills and ridges where lay the main American positions, in preparation for final attempts to recover the high ground by direct assault.