Chapter 4: The XV Corps Advance, 11–20 September

The Situation on the Southern Flank of the Third Army1

From the time the Third Army poured out of Normandy through the Avranches gap and into Brittany, it had operated with an unbelievably long and attenuated south flank. With one army corps tied up in western Brittany, by what amounted to siege operations, and two corps driving pell-mell in the direction of Germany, General Patton could detach only a limited portion of his cavalry, tanks, and infantry to guard the line of the Loire. Although the Third Army commander often expressed a cavalier disregard for his flanks this attitude was perhaps more apparent than real. The Third Army would rely heavily on the additional flank protection provided by the XIX TAC and the irregulars of the FFI. General Weyland’s planes maintained a constant lookout for any evidence of German troop concentration south of the Loire, swooping down to strike even small enemy columns. At General Patton’s request General Koenig, chief of the FFI, had ordered the FFI irregulars to reinforce the Third Army units patrolling the Loire flank. Although poorly armed and loosely organized, these French bands were extremely valuable, guarding bridges and supply dumps, patrolling roads, and ferreting out isolated enemy groups left behind by the swiftly moving American columns. An exact statement of the strength of these irregulars is impossible. It is probable,

however, that close to 25,000 of the FFI were cooperating with the Third Army II Special Forces Detachment (Lt. Col. R. I. Powell) by the end of August.

On 1 September the open flank of the Third Army extended from St. Nazaire, in Brittany, to Commercy and the Meuse River—a distance of 450 air-line miles. A further extension of this weakly guarded flank, as the Third Army approached the Moselle River and as the enemy stiffened, could not be undertaken with quite the same sang-froid that had marked General Patton’s August drive. General Bradley had repeatedly expressed concern about this exposed flank, which was also the south flank for the entire group of American armies then in northern France. And General Eddy, the new commander of the XII Corps, had assumed his post with some misgivings as to the relatively scanty protection that could be given the XII Corps right and rear—although General Patton characteristically tended to make light of this problem.2

There was general agreement, however, that reinforcements were necessary if the Third Army was to continue east across the Moselle River and still carry out its mission of protecting the open Allied flank. For this reason General Bradley promised General Patton on 25 August that Maj. Gen. Wade H. Haislip and the XV Corps headquarters, which had been taken from the Third Army during the Seine crossing operations, would be returned to the Third Army, and that as soon as possible some of the divisions “borrowed” by First Army during the August advance would fill out the corps. During the first days of September the XV Corps headquarters and some corps troops assembled east of Paris near Rozay-en-Brie. General Patton gave orders on 5 September that when the XV Corps was fleshed out it would be put in on the right of the XII Corps and there take over the protection of the south flank of the Third Army from Montargis eastward—a distance of about 150 miles. On 8 September the 2nd French Armored Division, leaving the scenes of its triumphal entry into Paris with the express consent of General de Gaulle,3 joined the XV Corps and took over the sector between Montargis and the Marne River. Meanwhile the 79th Infantry Division, coming from Belgium, began to assemble to the east of the French combat commands in the vicinity of Joinville. The movement of these two divisions released the 35th Infantry

Maj. Gen. Wade H. Haislip, XV Corps Commander

Division, which marched by regimental combat teams into the Toul area preparatory to taking part in the XII Corps attack across the Moselle.

General Haislip and the XV Corps headquarters were well known to Patton and the Third Army staff. The XV Corps had trained in North Ireland as part of the Third Army and had entered combat under Patton’s command. General Haislip, an infantryman, graduated from West Point in 1912. He took part in the Vera Cruz expedition, and during World War I served as a staff officer in the V Corps. After service in the peace years with the infantry and at the military schools, Haislip became G-1 in the War Department General Staff. There followed a tour of duty as a division commander; then, in February 1943, Haislip assumed command of the XV Corps.

General Haislip’s divisions had both seen earlier service with the XV Corps. The 2nd French Armored Division commander, Maj. Gen. Jacques Leclerc (a nom de guerre),4 had won fame in the Free French forces and was held in high regard by the XV Corps commander as an aggressive and able soldier.5 General Haislip himself was a graduate of the Ecole Supérieure de Guerre and by reason of this background was able to elicit a high degree of cooperation from the French general. The 2nd French Armored Division had its origin in French Equatorial Africa, when, in August 1940, the Régiment de Tirailleurs Sénégalais du Tchad joined de Gaulle. In December of that year Colonel Leclerc took command in the Tchad. After a series of successful raids against outlying enemy posts in Libya, Leclerc’s command made the long march north to join the British Eighth Army in December 1943. Additional Free French formations from Syria and Dakar, reinforced by loyal Frenchmen from all parts of the world, had increased the fighting strength of Leclerc’s force. In April 1944, after campaigning in North Africa, Leclerc’s command sailed for England as the 2nd French Armored Division. It arrived on French soil during the night of 1 August and fought its first action in France under the XV Corps. The losses suffered by the 2nd French Armored Division during the advance to Paris had been moderate and had been more than replaced by eager Frenchmen caught up by the patriotic fervor attendant on the liberation. The 79th Infantry Division was under the command of Maj. Gen. Ira T. Wyche. General Wyche was an artilleryman, a West

Maj. Gen. Jacques Leclerc, 2nd French Armored Division Commander

Point graduate in the class of 1911. He had served with the Allied Expeditionary Force in the St. Dié sector during the summer of 1918, but then had been brought back to the United States to train new gunners. In the postwar Army Wyche had continued the career of an artillery officer. In May 1942 he was given command of the 79th Division, a Reserve formation. The 79th Infantry Division had received an estimated 7,500 replacements over several weeks to make up for the losses sustained since entering combat in June. It was now at nearly full T/O strength and endowed with a good reputation as a veteran division.

The two divisions of the XV Corps had barely assembled southeast of Troyes when, on 11 September, the corps began the advance to the east ordered by General Patton as part of the general Third Army offensive. Unlike the Third Army left and center the XV Corps had no orders to cross the Moselle River, but instead operated under instruction to close up to the Moselle between Epinal and Charmes and continue to cover the south flank of the army in the sector east of Montargis. This dual mission made a power drive

straight to the east with both divisions out of the question. Instead, the first phase of the XV Corps attack would consist of a sequence of individual actions fought by separate combat teams or commands—irregularly echeloned back to the southwest so as to retain a continuing protective cover along the right flank of the Third Army.

The enemy forces confronting General Haislip’s troops on 11 September were little more than a heterogeneous array of small Kampfgruppen, collected piecemeal during the German retreat from southern and western France, under the LXVI Corps, commanded by General Lucht. (Map XVII) In the first week of September the LXVI Corps had operated as a kind of task force, directly under the command of Army Group G, charged with keeping the escape hatch open north of Dijon for the thousands of Germans moving in weary columns from the Mediterranean and the Bay of Biscay back toward the Reich. When General Patton’s rapid advance threatened to knife between the First Army, deployed along the Moselle line, and the Nineteenth Army, retreating north and east before General Patch’s Seventh Army, the LXVI Corps received specific orders to maintain contact—“at all costs”—with the 553rd VG Division of the First Army along the east-west line through Toul and Nancy that formed the German inter-army boundary. An additional burden was laid on the harassed LXVI Corps on 7 September when General Blaskowitz issued orders that it would form a main line of resistance along the Marne-Saône Canal, between Langres and Chaumont, and extend its right flank so as to screen the Neufchâteau–Mirecourt area—all this to secure maneuver space from which to launch a powerful counteroffensive against the Third Army’s exposed flank and rear. For this sizable task General Lucht was given permission to use the 16th Division (Generalleutnant Ernst Haeckel),6 which had marched clear across France from the Biscayan coast, shepherding a motley collection of smaller military detachments, customs officials, Todt workers and Luftwaffe ground personnel. The leading columns of this hegira, composed of the combat units, had just entered the Chaumont–Neufchâteau sector when the XV Corps attacked. In addition to having the 16th Division, the LXVI Corps was composed of Landesschützen (Home Guard) battalions, organized under Kampfgruppe Ottenbacher and the 19th SS Police Regiment,

whose battalions had been put in Andelot and Neufchâteau to cover the concentration of the 16th Division. Politics had outweighed military necessity, however, and on 3 September Himmler began the process of moving the 19th SS Police Regiment out of the area in order to provide “protection” for the French Chief of State, Marshal Pétain, and the Vichy administration now in Belfort.7 The LXVI Corps was weak, but the build-up of the XLVII Panzer Corps in the Neufchâteau–Mirecourt area, as part of the projected German counteroffensive, ultimately would provide some stubborn resistance in the path of General Haislip’s advance toward the east.

Hitler’s Plans for a Counteroffensive

The planning and operations of the German high command, as related to the strategic problem posed by the rapid advance of the Third Army, give an illuminating picture of the way in which Hitler’s “intuitive strategy” had come to supersede skilled professional operational planning and realistic appraisals of existing tactical conditions. In August 1944 Hitler studied the large-scale map in his headquarters at Eiche, near Berlin, and then ordered the counterattack toward Avranches designed to cut off the First and Third Armies, giving detailed instructions as to the way in which each division of the counterattack force should be employed.8 Now Hitler again intervened in an attempt to destroy the Third Army, and again without reference to the advice of his field commanders or the capabilities of the weapon in his hands.

On 28 August General Jodl, who had weathered the command crisis following the attempt on Hitler’s life and succeeded in retaining his post as chief of the operations staff in OKW, suggested a counteroffensive against the exposed flank of the Third Army, now extended from the neighborhood of Toul far back to the west. This attack was to strike in the Troyes sector and penetrate to the north between the Seine and the Marne. The project was abandoned as soon as it was proposed, for General Patton already was in force at the Meuse River. But on 3 September Hitler gave OB WEST new instructions for the over-all conduct of the war in the West which included

a plan for a large-scale counterthrust directed against the Third Army.9 This scheme was the most ambitious to be advanced during the months between the Mortain counterattack and the Ardennes offensive. By Hitler’s orders the German right wing and center would fight a defensive battle (but under no circumstances would any large units allow themselves to be encircled by the Allies). On the left wing a mobile force would be assembled west of the Vosges and given a dual mission: first, it was to cover the retreat of the Nineteenth Army and LXIV Corps while holding the terrain west of the Vosges necessary for freedom of maneuver; second, it was to attack in strength against the extended south flank of the Third Army, finally turning east to strike the American divisions in the back as they closed up facing the Moselle River. The Fifth Panzer Army staff, at the moment in Belgium, would be replaced by the staff of the Seventh Army and take over the direction of the counterattack.

This decision for a counterthrust at Patton’s army was in part dictated by the strategic necessity of preventing a juncture of the Third and Seventh American Armies, and in part by the exigencies of the tactical situation. On 3 September the troops under Blaskowitz still held a very substantial bridgehead across the Moselle in the area south of Toul. Here, at Neufchâteau, was the western terminus of the road net leading through the Trouée de Charmes, and from Neufchâteau ran the most direct and easiest military route for turning the south flank of the natural defense line along the Meuse escarpment—a line already in American hands. Neufchâteau had been an important communications center since the Napoleonic Wars, and in 1914 the GHQ of the Second French Army had been located there, adjacent to the operations being conducted in western Lorraine and northern Alsace.

Hitler proposed to implement his grandiose scheme with considerable force, and he personally selected the units to carry out the maneuver. The initial counterattack group, as designated by Hitler, was to be composed of the 3rd, 15th, and 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Divisions. It would be augmented by three new panzer brigades (111th, 112th, and 113th), to be brought up from Germany, and would be reinforced “if possible” by the Panzer Lehr Division, the 11th Panzer Division, the 21st Panzer Division, and three more panzer brigades (106th, 107th, and 108th). In addition, a single division (the 19th) would go to the First Army to replace the panzer grenadier units.

Several of the divisions named by Hitler were closely engaged on the First Army front at the time he gave his order, or were already in contact with American patrols pushing toward the Moselle. The three panzer grenadier divisions were in the Metz area, with one panzer grenadier regiment of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division engaged west of Arlon, in Belgium. The 11th Panzer Division was fighting a rear guard action in the Besançon area, to cover the eastern flank of the retreating Nineteenth Army. The famous Panzer Lehr had been reduced to a shadow division and was still engaged. The 21st Panzer Division was refitting. Of the panzer brigades only the 106th had reached the front, detraining at the moment near Metz, while the rest were organizing in Germany. Model, aware of the true situation, begged for three armored divisions from the Eastern Front, but with no success.

Again, as at Mortain, the means were not available fully to carry out the plan. The Russian front was an ever-present consideration in all allocations of tanks and men.10 Even while Blaskowitz was reading Hitler’s counterattack order, his staff and service echelons were being stripped of “volunteers” to reconstitute the 49th VG Division for use in the East. In Belgium the Allies had broken through every line the Germans had hoped to hold, and the very day after Hitler issued his counterattack order Field Marshal Rundstedt appealed to Berlin for twenty-five new divisions and an armored reserve of five to six divisions, without which, he said, the entrance to northwest Germany could not be defended. Finally, it was only a matter of hours until Patton, with his superior forces, would pin the First Army to the Moselle line.

Although the counterattack was the responsibility of General Blaskowitz and Army Group G, Hitler himself chose the commands to carry out this mission. Initially, the headquarters of XLVII Panzer Corps (General Lüttwitz) would head the counterattack group; but as quickly as possible the headquarters of the Fifth Panzer Army would be brought back from Belgium, reorganized, and sent forward to assume the command.

Blaskowitz, at his headquarters in Gerardmer, west of Colmar, reacted to the Führerbefehl with the promptness to be expected from a German commander not yet completely cleared of the suspicion that attached itself to all general staff officers after the 20 July putsch. On 4 September he finally reached Lüttwitz by phone (all wires had been out), told him of the plan, and ordered the XLVII Panzer Corps headquarters down from Metz to take

over in the Mirecourt–Neufchâteau area, the base for the proposed operation. The target date for the counterattack was set for 12 September—while Blaskowitz cast about for troops to give Lüttwitz. On or about that date the offensive would open with a thrust to the northwest on either side of Toul; this was to be followed by a general advance toward the Marne River, with the left German wing covered by the Marne, the center pushing through Bar-le-Duc, and the right wing moving south of the Argonne Forest.

On 5 September Blaskowitz told General Wiese that his Nineteenth Army must now stand and hold on its right flank, designating the main line of resistance from the Langres Plateau east to Besançon as essential cover for the concentration of the counterattack group in the north. At the same time, however, the American XII Corps was becoming a threat east of Toul. After General Chevallerie had protested that his First Army dared not further extend its already weakened south flank by moving the line of the 553rd VG Division down to Neufchâteau, the LXVI Corps was assigned the stopgap mission. In spite of this regrouping, Allied pressure all along the Western Front made it difficult, if not impossible, for the German divisions earmarked for the big counterattack to disengage and move rapidly into the bridgehead being held open between Neufchâteau and the Moselle. General Blaskowitz reluctantly informed OB WEST on 7 September that the target date for the counterattack must be set back to 15 September. General Knobelsdorff,11 menaced on the First Army front by the preliminary XII and XX Corps’ attempts to put bridgeheads across the Moselle, asked for permission to shorten his left wing and free additional troops by a withdrawal behind Nancy to an anchor position on the Marne-Rhin Canal. Promptly, however, Blaskowitz appealed to OB WEST, reminding that headquarters, probably needlessly, of Hitler’s express demands for a stroke against the Third Army. OB WEST replied on 8 September by transferring General Knobelsdorff’s First Army from Army Group B to Army Group G, under Blaskowitz’ command.

This addition of the First Army, from which many of the units tabbed for the counterattack were to be taken, did little to solve Blaskowitz’ problem. General Knobelsdorff now had his hands full south of Metz where the XX Corps had begun crossing the Moselle, and the XIII SS Corps, defending that sector, could not release the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division and the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division. Knobelsdorff also held on to one regiment of the

15th Panzer Grenadier Division, in spite of repeated orders for its release, pleading that lack of gasoline prevented movement to the south. In addition, the 106th Panzer Brigade had been thrown into a hasty counterattack against the 90th Division west of Thionville, on 8 September, and had come out of the fight with only nine usable tanks and assault guns—and no ordnance train to repair its damaged equipment.

Field Marshal Rundstedt had been sending daily reminders from his headquarters at Koblenz that the Hitler-inspired offensive must take place regardless of all difficulties. The Allied threat in the Aachen sector was growing more ominous hourly. On the German Seventh Army front the West Wall itself was in danger. At least six weeks, according to the calculations of the OB WEST staff, would be needed to put the West Wall in a state of proper defense. Rundstedt had a limited course of action. He could rush troops to the Aachen area and beg Hitler for new divisions. This he had done. He could hope to win time by seizing the initiative on another part of the front. This Hitler had decided, counter to Rundstedt’s desire to mass all available armor in defense of the gateway to the Cologne plain. Therefore, on the night of 7 September, Rundstedt sent an appeal to Jodl asking that OKW support the Fifth Panzer Army with sufficient matériel, fuel, and planes to make the counterattack a success. On 9 September, however, Blaskowitz was informed that the XLVII Panzer Corps would begin the counterattack with only a Kampfgruppe (Colonel Josef Rauch) from the 21st Panzer Division and the 111th and 112th Panzer Brigades coming up from Germany—a very considerable reduction from the scope of the original plan. Such a force was hardly calculated to inspire much confidence in any far-reaching success. The two panzer brigades were newly organized and equipped with a battalion of Mark IV’s and a battalion of Mark V’s (Panthers) apiece—a total of ninety-eight tanks, per brigade—plus a two-battalion regiment of armored infantry. But the 21st Panzer Division was woefully weak, for it had been broken up after the August fighting—one panzer grenadier regiment being assigned to Army Group B and the bulk of the remaining units being returned to Germany for refitting. Of the 21st Panzer Division, Blaskowitz had at his disposal on 9 September only the 192nd Panzer Grenadier Regiment (with three companies totaling about 250 men and 10 light machine guns), the 22nd Panzer Regiment (with no tanks), seven batteries of artillery (five of which had no prime movers), and two 88-mm. antitank guns.

Before even this modest force could be committed the XV Corps began a drive on a forty-mile front toward the Moselle, overrunning the Mirecourt–Neufchâteau area. Yet even now Berlin remained far removed from the tactical situation and Hitler issued a Jovian decree that the Fifth Panzer Army would not be used in any frontal attacks against the advancing Americans, but would be kept intact for its main mission. Blaskowitz gave a very liberal interpretation to this last order (if he did not flatly violate it) and committed the 112th Panzer Brigade against the XV Corps, with such disastrous results as to make that panzer brigade little more than a cipher in future operational plans.12

The XV Corps Advance to the Moselle

On the morning of 10 September the 313th Infantry (Col. S. A. Wood) arrived in the Joinville area, completing the movement of the 79th Infantry Division from Belgium to the south flank of the Third Army. The 315th Infantry (Lt. Col. J. A. McAleer) was already deployed and patrolling on the east bank of the Marne River. The 314th Infantry (Col. W. A. Robinson) had assembled on the west bank. The 79th Division, constituting the XV Corps left, lay forward of the 2nd French Armored Division, which was echeloned back to the southwest as a screen for the corps and army. (Map XVIII)

The XV Corps had made no contact with the Germans in the Chaumont–Neufchâteau sector. Intelligence reports indicated that the enemy was holding a string of towns along the main highway leading from Chatillon-sur-Seine northeast to Neufchâteau, and from Neufchâteau to Charmes, on the Moselle. Earlier in September the 42nd Cavalry had given the German high command a scare by sending small patrols toward Charmes. Indeed, Hitler had sent a personal order that Charmes be “retaken” at once, despite the fact that the Americans never entered the town. But the XII Corps cavalry had turned back to the north as the corps prepared to cross the Moselle, and ground observation of German troop movements into the Neufchâteau sector had ended. As a result the impending advance by Haislip’s XV Corps would be a meeting engagement in the classical sense epitomized for American military students by the 1914 clashes at Virton and Longwy.

The original mission given the XV Corps had been a relatively passive one. On 10 September, therefore, the troops were reconnoitering for defense positions, resting, taking hot baths in Joinville, and—in the 79th area—listening to Bing Crosby and his USO show. The 106th Cavalry Group (Col. Vennard Wilson) was moving through the 79th en route to take over a screening mission south of the infantry outposts. General Wyche, with Third Army permission, had just dispatched forty-eight of his 2½-ton trucks to the rear for supplies. Meanwhile the 35th Infantry Division, farther to the north and east, had begun the attack to carry the right wing of the XII Corps across the Moselle River. A little before 1500 a telephone message from the Third Army reached Haislip, alerting the XV Corps for advance to the east. This movement, set for the following morning, was intended to bring the corps to the west bank of the Moselle on a front extending from Charmes to Epinal. As yet, however, General Patton had given no orders for crossing that river in the XV Corps zone.

The main weight in this maneuver would have to be furnished initially by the 79th Division, since only a part of Leclerc’s armor could be freed from the screening mission on the army flank. General Wyche selected the 314th Infantry for a stroke calculated to seize Charmes and gain a position on the Moselle. The corps commander immobilized two battalions of corps artillery to motorize the 314th. Only five medium tanks of the 749th Tank Battalion (attached to the 79th Division) were in repair; these tanks and a company of tank destroyers also were given to the 314th Infantry. About 0800 on 11 September the 314th Infantry entrucked and, preceded by the 121st Cavalry Squadron, began a semicircular sweep of some sixty-five miles around the enemy outposts and across the face of the 16th Division, which was deployed fronting northward along the line Andelot–Neufchâteau–Charmes. The cavalry came within sight of Charmes around 1700 and engaged in a brief skirmish with the German outposts, but the 314th did not arrive in the Charmes neighborhood for another two and a half hours—too late to set up an attack against the town. The 313th Infantry had followed the 314th during the day, in trucks and on foot. In the late afternoon it wheeled south to get into position for an attack toward Mirecourt, possession of which would cut the main German line of communications leading from Neufchâteau to Epinal. The 315th Infantry meanwhile made twenty-two miles, also by motor and on foot, and as the day ended halted west of Neufchâteau, where patrols went forward to feel out the German positions.

While the 79th Division moved swiftly to strike at the north shoulder of the LXVI Corps salient, General Leclerc’s armor attacked the German units farther west. Here Kampfgruppe Ottenbacher held a defensive position behind the Marne and Marne-Saône Canal at right angles to the 16th Division, with its northern wing resting on Andelot and its southern wing abutting on the Langres Plateau. Generalleutnant Ernst Ottenbacher’s command consisted mainly of over-age reservists, poorly trained and armed, who had been assigned to police duties during the German occupation of France. Just before the French attack General Ottenbacher lost his only well-equipped and mobile troops when the 100th Motorized Brigade and the last two battalions of the 19th SS Police Regiment were taken away and sent to Belfort, leaving the Kampfgruppe with only six Landesschützen battalions.13

General Leclerc began to probe the German positions on the morning of 11 September, using one combat command to make the developing attack while the rest of the division continued the screening mission along the Third Army flank. Combat Command L (Col. Paul Girot de Langlade) began a maneuver in front of Andelot but found the Germans strongly entrenched. General Leclerc, anxious to avoid premature and piecemeal entanglement on ground chosen by the enemy, ordered CCL to bypass Andelot and reconnoiter farther to the east. This order was carried out with dispatch. Colonel Langlade’s command, advancing in two columns, struck sharply through Prez-sous-Lafauche, at the joint between the 16th Division and Kampfgruppe Ottenbacher, and cut the Neufchâteau–Chaumont and Neufchâteau–Langres roads. When night put an end to the French advance one column was nearing Vittel and the whole of CCL was deep inside the German lines.

The XV Corps maneuver on the first day of the advance had brought its troops around the enemy or through the weak spots in the overextended lines of the LXVI Corps. Now, on 12 September, General Haislip’s units came to grips with the Germans in a disconnected series of local engagements and surprise meetings extending all the way from Charmes back to Andelot. The 79th Infantry Division, spread over a forty-mile front, engaged the 16th Division, whose troops had been concentrated in a succession of towns organized as strong points. At Charmes the 314th Infantry attacked in midmorning and after a day-long fight drove the defenders, approximately two battalions of the 225th Regiment, out of the town and back across the Moselle. The retreating

Germans blew the Charmes bridges, but General Haislip ordered General Wyche to cross and secure a bridgehead. After dark the 1st Battalion of the 314th found a ford and crossed to the east bank without mishap. North of the town the 106th Cavalry Group started to cross the Moselle, meeting no opposition. West of Charmes the 313th became involved in a fire fight with a strong force from the 221st Regiment drawn up near the little village of Poussay just outside of Mirecourt. At Neufchâteau the 315th converged on the town from three sides, pushed the attack home late in the evening, and trapped a large part of the 223rd Regiment. Next day the German commander surrendered, turning over 623 prisoners and 80 vehicles and heavy weapons.

The 2nd French Armored Division also was busily engaged on 12 September, cutting into Kampfgruppe Ottenbacher and driving almost at will through the German rear areas. CCL outflanked Vittel from the south and reported a bag of over five hundred prisoners, captured as they fled along the highways. CCV (Col. Pierre Billotte), committed at Andelot, had a brisk fight and not only killed or snared the entire garrison but also cut to pieces a German battalion, en route from Chaumont to reinforce Andelot. The reports of the 2nd French Armored Division record that CCV killed an estimated 300 Germans and captured nearly 800 in this action.

Thus far Kampfgruppe Ottenbacher and the 16th Division had fought alone, defending strong points in crossroads towns and villages, and meeting defeat in detail as the Allied troops cut through their lateral communications. General Blaskowitz, torn by the dilemma of obeying Hitler’s orders to hold back the forces selected for the big counteroffensive without losing the Mirecourt–Neufchâteau area from which it was to be made, finally could delay no longer. On 12 September Blaskowitz ordered General Manteuffel to use elements of his newly arrived Fifth Panzer Army in a limited counterattack against the XV Corps. Manteuffel assigned this mission to General Lüttwitz’ XLVII Panzer Corps, which had been concentrated between Epinal and St. Dié. Lüttwitz was given no time for reconnaissance and no opportunity to arrange a coordinated attack; he was simply instructed to attack toward Vittel, free the encircled troops of the LXVI Corps, and drive northwest into the Allied flank. This move would give the Nineteenth Army time and space in which to extend its right wing northward as a covering force for the deployment of the Fifth Panzer Army.

The forces General Lüttwitz had under his command were relatively weak and widely separated. The 112th Panzer Brigade furnished the bulk

and the armored backbone of the XLVII Panzer Corps. If committed under different circumstances it might have been a formidable threat to the fragmentized XV Corps, since it had a full complement of new tanks: a battalion of 48 Mark IV’s and another of 48 Mark V’s. On 12 September the 112th Panzer Brigade debouched from Epinal in two columns. The right column, consisting of the Panther battalion, mobile infantry, and artillery, moved directly west in the direction of Vittel while the left column, containing the Mark IV’s, began a circular movement that carried it south toward Bains-les-Bains, in anticipation of an attack by advance units of the American Seventh Army which were already as far north as Vesoul. Late in the day the right column of the 112th Panzer Brigade bivouacked near the village of Dompaire, southeast of Mirecourt. The left column, finding no American troops on its flank, had begun to wheel north toward Darney, from which a main road led to Vittel. General Lüttwitz now decided to commit Kampfgruppe Luck, the weak infantry detachment belonging to his corps, and ordered it to march to Dompaire on 13 September.14 Once this infantry reinforcement had reached the north column and the south column was in position, Lüttwitz intended to throw the combined strength of the 112th Panzer Brigade and Kampfgruppe Luck at Vittel, some eleven miles to the west. But this ambitious plan was doomed to failure.

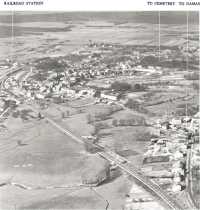

After seizing Vittel on 12 September, CCL, 2nd French Armored Division, continued east and laagered that night just short of Dompaire and Damas—the latter a village about two miles southeast of Dompaire. During the late afternoon French civilians had brought word to Colonel Langlade’s headquarters that a large German tank force was moving on Dompaire. This intelligence was confirmed in the early evening when French outposts picked up the sound of heavy vehicles congregating in the area. Langlade ordered his artillery into position and prepared to engage the enemy on the morrow. His plans were simple: the right column (Colonel Minjonnet) of CCL would strike through Damas and cut the main road between Dompaire and Epinal; the left column (Lt. Col. Jacques Massu) would attack the enemy concentrated at Dompaire. The village of Dompaire lay in a narrow valley and most of the German tanks were assembled here on the low ground.

At dawn on 13 September a small reconnaissance party, headed by four tank destroyers, left Minjonnet’s bivouac and rolled toward Damas. Just short

Dompaire

of the village it surprised some German Panthers, loosed a few rounds, knocked out a Panther, and hurriedly retired to the shelter offered by a small ridge. The German tankers made no move and soon the 12th Chasseurs was on the scene with its Sherman tanks. Colonel Langlade meanwhile had sent Massu’s force around to the north of Dompaire. Here his observers reported the town and near-by fields “literally crawling” with enemy tanks. Langlade made a feint with his armored infantry and then, when the German Panthers started to deploy to counter this move, the French poured in a terrific fire from their tanks and field guns. But the French were not to engage the Panthers by themselves. The American air support officer with the 2nd French Armored Division had succeeded in reaching XIX TAC by radio and General Weyland’s headquarters dispatched the 406th Group from its base at Rennes, far back in Brittany. The fighter-bombers made four strikes at Damas and Dompaire during the day, lashing at the huddled Germans with bombs and rockets. After each air strike Massu and Minjonnet displaced forward, using the cover of neighboring apple orchards and pine groves and compressing the milling Panthers into a narrowing killing ground on the valley bottom. Eventually the French seized a cemetery, on a rise at the north edge of Dompaire, that gave them complete control of the battlefield. In the afternoon the leading tanks of the south column of the 112th Panzer Brigade were discovered moving hurriedly toward Ville-sur-Illon, apparently intent on striking the French in the rear. CCL, however, was ready for this new threat and destroyed seven Mark IV’s at the first encounter. As this action continued the German losses increased, and finally the southern column abandoned its rescue attempt. Late in the day the Germans in the Dompaire sector deserted their vehicles and fled on foot to the east, leaving the battlefield to the French.

This fight, characterized warmly by the XV Corps commander as a “brilliant” example of perfect air-ground coordination, not only was an outstanding feat of arms but also had dealt a crippling blow to Hitler’s plans for an armored thrust into the Third Army flank. The 112th Panzer Brigade had lost nearly all of its Panther battalion—only four of these heavy tanks escaped the Dompaire débacle. In addition the Mark IV battalion had sustained some loss, bringing the total number of tanks destroyed to sixty.15

That day, 13 September, also proved to be an unlucky one for the Germans still fighting in the area west of Dompaire. CCD (Col. Louis J. Dio), the reserve combat command of the 2nd French Armored, took Chaumont and ended the last organized resistance by Kampfgruppe Ottenbacher. The 315th Infantry captured its substantial bag of prisoners and weapons at Neufchâteau after a stubborn house-to-house fight in the town. The 313th Infantry experienced some difficulty in coordinating plans for its attack to take Poussay: companies had become separated and the supporting artillery was not in position. By late evening, however, the 2nd Battalion was inside the village.16 In the confusion and darkness the Americans bivouacked next door to the enemy, some—it was later reported—in the same buildings with the Germans. Elsewhere the German retreat turned into a rout, although here and there small detachments attempted a stand, or minute rear guard tank and assault gun detachments essayed fruitless counterattacks. The events of this day finally convinced Blaskowitz that he should withdraw the 16th Division to the east before it was completely destroyed. General Lucht, the LXVI Corps commander, had advocated such a retirement many hours earlier. Now it was too late to make any coordinated withdrawal; the 16th would make its retreat in a general sauve-qui-peut.

Nevertheless the 79th Division, having had word of the tank battles on the south flank of the XV Corps, proceeded cautiously on 14 September, as yet unaware of the summary manner in which the French had disposed of the German armor. At Charmes the 315th Infantry extended its outposts to the south, while patrols from the 106th Cavalry Group reconnoitered on the east bank of the Moselle. The 313th Infantry mopped up Poussay, where the 2nd Battalion took seventy-four prisoners, and its 1st Battalion captured Mirecourt, thus cutting the Neufchâteau–Epinal road. That evening the 2nd Battalion bivouacked in the village of Ramecourt, on the road west of Mirecourt, with the intention of blocking the Germans who were fleeing from the 315th Infantry after a rear guard fight at Châtenois. At midnight the head of a retreating German column marched unexpectedly into the village and without preamble began to bivouac in the streets and houses where the American infantry lay. Sudden mutual recognition precipitated a burst of “wild fighting.” About two hundred prisoners were taken in the village itself and the

tail of the German column, still on the road, was riddled by the quick and accurate fire of the American gunners. By daylight over five hundred of the enemy had been killed or captured.17

The French, pursuing their victory of the preceding day, engaged Kampfgruppe Luck and some Mark IV’s near Hennecourt. But General Lüttwitz was unwilling to risk what was left of his command and on the night of 14 September ordered the 112th Panzer Brigade and Kampfgruppe Luck to withdraw to the Canal de l’Est just west of the city of Epinal, there to hold open a route of escape for the fleeing troops of the 16th Division and the remnants of Kampfgruppe Ottenbacher.

Although the XV Corps drive had been highly successful, General Haislip was restive under the compulsion of using one of his two divisions to protect the Third Army flank, and he therefore importuned General Patton for an additional infantry division. The Third Army commander had no infantry to spare. But on 14 September General Bradley released CCB of the 6th Armored Division in the sector west of Orléans and Patton sent it to take over the 2nd French Armored Division security mission west of Troyes. On this same day the 2nd French Armored met a Seventh Army patrol (from the 2nd Spahis, 1st French Armored Division) near Clefmont. This connection between the Third and Seventh Armies remained very tenuous, however, and while the 79th Division closed on the west bank of the Moselle General Leclerc’s combat commands remained strung out back to the southwest in position to guard the corps and army flank. Rumors of the movement of German armor in the Epinal area—which took on greater significance in the light of the big tank battle at Dompaire—had had enough weight to convince even General Patton that a continued watch toward the south and west was necessary, and on 14 September he gave verbal orders to the XV Corps commander to hold the balance of the 79th Division west of the Moselle and await crossing orders.18

Meanwhile, the enemy pocket between the Third and Seventh Armies was emptying rapidly. The remnants of the 16th Division fled as best they could, in civilian automobiles and on foot, as single stragglers and in disorderly groups. By 16 September what was left of this ill-fated command had crossed the Moselle, and both the XV Corps and Army Group G wrote off

the division as a combat unit. Following their usual practice the Germans subsequently re-formed the division under its old number, but American and German records both show that the 16th Division had been reduced to a mere number on a troop list in the five-day battle.19

While the 79th swung into line on the west bank of the Moselle, the advance battalion of the 314th Infantry remained in position on the east side of the river opposite Charmes, with the XV Corps artillery sited to give fire support if necessary. Actually, only scattered security forces faced the 79th at this point since the German position on the Moselle had been unhinged by the XII Corps advance in the north. One troop of the 106th Cavalry Group had crossed the river in the XII Corps area and then turned south to screen in front of the Charmes bridgehead. More of the corps cavalry crossed on 16 September and began to reconnoiter toward the Mortagne River, believed to be the next enemy line of resistance. During this same day a combat team from CCV, the most advanced of Lerclerc’s units, got into a sharp fight at Châtel, a village on the enemy bank of the Moselle about six miles south of Charmes to which the French had crossed during the previous night. Late on the afternoon of 16 September a large task force from the 111th Panzer Brigade (estimated to consist of fifteen Panthers and two infantry battalions) suddenly struck Châtel in a pincers attack. General Leclerc hurried reinforcements to the scene and the Germans were beaten off—an officer prisoner later told his captors that the attackers had lost two hundred men and five Panthers. Nevertheless, the French general withdrew his men across the river in order to avoid involvement in a large-scale engagement while he was still charged with protecting the army flank west of the Moselle.

It was only a matter of days until the Third and Seventh Armies would be aligned more or less abreast, facing east and in position to give some mutual cover on their inner wings. The 2nd French Armored Division cavalry (Col. Jean S. Remy),20 patrolling near Bains-les-Bains on 17 September, made contact with their compatriots of the French II Corps (Lt. Gen. de Goilard de Monsabert) who had driven north along the valleys of the Rhone and Saône on the left flank of the Seventh Army. In the gap still remaining to the west CCB, 6th Armored Division, arrived to relieve CCD in the Chaumont

sector, whereupon General Patton relieved the XV Corps of responsibility for watching the Third Army flank, save in the narrow space between the Meuse and Moselle Rivers. By the night of 17 September all of the 2nd French Armored Division was alongside the 79th on the west bank of the Moselle, except Langlade’s combat command and Remy’s cavalry, which remained echeloned to the right and rear of the division.21

The Advance to the Meurthe River

The XV Corps commander had expected to resume the attack east of the Moselle River on a somewhat narrower front, advancing in a column of divisions with the 2nd French Armored Division in the lead so as to give some rest to the tired infantry of the 79th Division. On 18 September, however, German armor struck the XII Corps at Lunéville. About 1345 General Patton arrived at General Haislip’s headquarters and after a conference with Haislip and the two division commanders ordered an immediate advance across the Moselle. The XV Corps mission remained the same—to furnish protection for the Army’s south flank—but General Patton changed the axis of attack from east to northeast, consonant with the general shift toward the northeast by the entire Third Army. This maneuver would give the XV Corps an extended front and require the use of both its divisions in the first stages of the advance. The 79th Division, on the left, would move toward Lunéville and cover the exposed right wing of the XII Corps, which was being subjected to increasingly heavy enemy pressure. The 2nd French Armored Division also would cross the Moselle and put some weight into the attack. The Seventh Army, however, had not yet pushed its northern flank as far as the Moselle and at the moment was in process of moving the 45th Division (Maj. Gen. W. W. Eagles) in to relieve the II French Corps on the army’s left wing. Until the 45th Division could resume the offensive and draw abreast of General Haislip the 2nd French Armored would have to make its attack a limited affair and concentrate heavily on screening toward the south and east.22

The German detachments facing the XV Corps were small in numbers and lacked heavy weapons. On the morning of 18 September the Fifth Panzer Army

finally had begun the often-postponed counteroffensive against the Third Army. Strategic circumstances had whittled away both the force and the maneuver area envisaged in Hitler’s original plans; the counteroffensive had dwindled in scope to what could more accurately be called a counterattack and its mission now was limited—at the most optimistic—to wresting the line of the Moselle away from the XII Corps. Lüttwitz’ XLVII Panzer Corps had a dual role in the undertaking. Most of it was thrown into an attack northward toward Lunéville. Part of the 21st Panzer Division and the remainder of the 112th Panzer Brigade were charged with guarding the exposed left flank of the Fifth Panzer Army along the Mortagne River, in which position these security detachments would meet the 79th Division attack. Farther to the south, in the Epinal–Rambervillers sector, the battered and broken LXVI Corps under the Nineteenth Army furnished a none too dependable anchor for Lüttwitz in an oblique extension from the latter’s left wing. Remnants of the 223rd Infantry Regiment (16th Division), reinforced by a few of Lüttwitz’ tanks and the loan of two of the three 88-mm. guns salvaged by Ottenbacher during the recent retreat, still held a position on the Moselle River at Châtel, which had been reoccupied when the advance guard of the French armored division withdrew to the west bank.

In midafternoon of 18 September the 314th Infantry, which already had a battalion east of the Moselle, began the XV Corps advance, marching behind the screen thrown out by the 106th Cavalry Group as far as Moriviller, where the regiment bivouacked for the night. The 313th Infantry crossed the river and then moved by truck to Einvaux, thus taking position on the left of the division. The 315th Infantry, in division reserve, also crossed the Moselle during the night of 18–19 September and closed behind the 313th Infantry. Thus far the 79th had met no opposition, but the movement had started too late in the day to bring the division to the Mortagne River that same evening, as Patton had ordered.

The 2nd French Armored Division began its advance in the late afternoon, under orders to drive no farther than the highway between St. Pierremont and Gerbéviller which followed the eastern bank of the Mortagne River. General Leclerc left CCL west of the Moselle as flank protection and brought Dio’s combat command up from reserve to head the attack. Three bridges quickly were thrown across the Moselle and while CCV held the bridgehead Dio’s tanks roared through the streets of Châtel, guided by the light of burning German trucks and the flashes of rifle fire from the houses where the enemy

lay barricaded. By daylight CCD was clear of Châtel and racing toward the Mortagne River.

Both of General Haislip’s divisions threw elements across the Mortagne on 19 September. The left regiment of the 79th, the 313th Infantry, put its advance guard across the river without opposition but ran into a sharp fight with some troops of the 192nd Panzer Grenadier Regiment, 21st Panzer Division, at the town of Xermaménil. The 21st Panzer Division, however, was too dispersed in its role as a covering force to fight more than a delaying action at any point on the Mortagne, and the 313th quickly cleared Xermaménil—opening the road to Lunéville. The 314th Infantry, moving on foot, reached the river about 1800 and opened an assault on Gerbéviller, whose bridges led to one of the few good roads east of the Mortagne. At dark the American attack was called off, but during the night the German garrison withdrew to the east. Dio’s French combat command reached the Mortagne about 1400; it found the enemy feeble and the crossing denied only by mines and blown bridges. During the evening the French made their way over the river near the village of Vallois, then dispatched reconnaissance troops to Vathiménil, on the west bank of the Meurthe River, which was taken around midnight.

The XV Corps breached the thin German line along the Mortagne at a half-dozen points on 19 September and during the night the Fifth Panzer Army commander ordered Generalleutnant Edgar Feuchtinger to pull his weak 21st Panzer Division, which had been reinforced by the 112th Panzer Brigade, back behind the Meurthe. But the detachments on the south flank were entrapped by the French raid to Vathiménil and were forced to flee on foot, abandoning over two hundred vehicles and some of the tanks belonging to the unfortunate 112th Panzer Brigade. General Blaskowitz railed at the Fifth Panzer Army commander for relinquishing the Mortagne line, but this was no more than a “statement for the record” since Army Group G had no reserves with which to shore up the Fifth Panzer Army’s threatened flank.

On 20 September the XV Corps made contact with the XII Corps in Lunéville, where the latter had been fighting since 16 September for command of the road and river complex dominated by the city. The leading battalion of the 313th Infantry passed through Lunéville, in which Americans and Germans still were battling, and wheeled southeast on the enemy bank of the Meurthe River in preparation for an attack designed to roll up the flank of the new German security line. To the south the 314th Infantry reached the Meurthe River but came under such heavy fire from the Forêt de Mondon,

in which the Germans had taken cover on the east bank of the river, as to be prevented from an immediate crossing. In the meantime the 2nd French Armored Division held in place and limited its activities to patrolling. CCL, which had been kept on the west bank of the Moselle to watch the German bridgehead at Epinal, was relieved during the day by the 45th Infantry Division. With the Seventh Army thus in position to start its left wing attacking across the Moselle, CCL moved east to rejoin Leclerc.

On 20 September General Patton altered the XV Corps left boundary, pushing it north to the Marne-Rhin Canal. This change allowed General Haislip more room for maneuver on his left flank. It also gave the XV Corps the responsibility for ejecting the remaining Germans from Lunéville and ultimately would bring the 79th Division into a bloody battle east of the city for possession of the Forêt de Parroy. The boundary shift had equally important implications in the XII Corps zone. When the German counterattack on 18 September hit the salient formed by the southern wing of the XII Corps, General Eddy’s troops had been caught in a precarious position astride the Marne-Rhin Canal. Now the XII Corps commander could concentrate his forces to meet the main German attack north of the canal.23