Chapter 7: The XII Corps Resumes the Offensive, 8–17 November

Plans for the November Offensive1

During the last week of October the XII Corps began to map plans for the day when the Allied supply situation would allow the Third Army to resume the offensive. On 3 November General Eddy issued Field Order No. 10 giving the general mission for the drive now scheduled to open between 5 and 8 November. Faulquemont, about twenty miles east of the front lines of the 80th Division on the main railroad between Metz and Saarbrücken, was designated as the first objective. Thereafter the XII Corps was to advance “rapidly” to the northeast and secure a bridgehead over the Rhine River, in the sector between Oppenheim (south of Mainz) and Mannheim. The first general objective east of the Rhine was indicated tentatively as the Darmstadt area.

General Eddy had a very sizable force under his command for this operation: three infantry divisions, including the veteran 35th and 80th—now brought up to strength by replacements—and the new 26th; two veteran armored divisions, the 4th and 6th; and seventeen battalions of field artillery, approximately nine engineer battalions, seven tank destroyer battalions, seven antiaircraft artillery battalions, three separate tank battalions, and two squadrons of mechanized cavalry.

American intelligence agencies estimated the German strength opposite the XII Corps as two complete infantry divisions (the 559th and 361st VG Division), plus a part of the 48th Division and some smaller formations, giving a strength of about 15,000 men and twenty tanks or assault guns. In addition it was believed that the 11th Panzer Division and the panzer regiment

of the 21st Panzer Division were re-forming in rearward areas within the XII Corps zone of advance. This G-2 appreciation was fairly accurate, although the 21st Panzer Division actually was far to the south in the Nineteenth Army area.

The 361st VG Division (Colonel Alfred Philippi) had come into the Moyenvic sector on 23 October, there relieving the 11th Panzer Division. New and unseasoned, it was organized under a reduced T/O with two battalions per regiment and manned with a collection of sailors, Luftwaffe personnel, and a miscellany of other similar troops stiffened by a substantial number of veteran officers and noncoms. Artillery and train were horse-drawn—indeed the movement of the division from north Holland had been delayed for several days by an epidemic among its horses. Unlike other divisions, whose artillery had been left immobile by the shortage of automotive prime movers and gasoline, the 361st was able to haul its full complement of guns. In addition the division had one battery of assault guns.

The 559th VG Division (Mühlen), still in the Château-Salins area, had been roughly handled by the XII Corps in earlier fighting but could hardly be considered a weak division—at least in comparison with other VG divisions on the Western Front. However, it did lack tank destroyers and other heavy antitank weapons. The 48th Division (Generalleutnant Carl Casper) had fought against Third Army troops at Chartres and then, in September, had taken extremely heavy losses in the fighting in Luxembourg. On 13 October the 48th was sent in opposite the 80th Division to relieve the wrecked 553rd VG Division, although it too was far below strength. The 48th had been rebuilt, but with over-age replacements, and now it was considered one of the poorest divisions on the First Army front. Two of its regiments had had some training, but the third (the 128th Regiment) was not yet ready for combat.

During October the headquarters of the Fifth Panzer Army and the XLVII Panzer Corps had been withdrawn from Army Group G. On 1 November the LVIII Panzer Corps headquarters went north to the Seventh Army and was replaced by the LXXXIX Corps (General der Infanterie Gustav Hoehne), which took over the sector on the left flank of Priess’ XIII SS Corps. On the eve of the American offensive the German order of battle opposite XII Corps was as follows: the 361st VG Division, assigned to the LXXXIX Corps, disposed in the sector from the Marne-Rhin Canal up to a point just west of Moyenvic; the 559th VG Division, deployed toward the west with its right boundary at Malaucourt; and the 48th Division, holding a

line from Malaucourt to north of Eply. These last two divisions were under the XIII SS Corps.2

Although General Balck had outlined a detailed defense plan to his subordinates, based on the collection of local reserves for immediate counterattack, the German divisions, understrength as they were, could not afford the luxury of large tactical reserves. Early in November the 48th Division had one battalion in reserve at Delme Ridge; the 559th VG Division was rotating its regiments in a reserve position in the Château-Salins area, and the 361st VG Division had a battalion in reserve near Dieuze. Few, if any, changes were made in these allocations of reserves before the American attack. The 11th Panzer Division remained the only division in operational reserve available to Army Group G in the area west of St. Avold. This division had been re-equipped after the September battles with the 4th Armored Division; on 8 November it had a complement of nineteen Mark IV tanks and fifty new Panthers, but not more than one or two tank destroyers. The reserve location of the 11th Panzer Division had been chosen with an eye to meeting an attack from either Thionville or what the Germans still called the “Pont-à-Mousson bridgehead.” But when the First Army commander had raised the question as to where the 11th Panzer Division would counterattack in case the American offensive should strike in both these sectors, General Balck, with no other reserves at hand, could only defer an answer.

Hitler himself added another reserve component to Army Group G at the eleventh hour by sending it the 401st Volks Artillery Corps. The five artillery battalions making up this new unit were detraining at St. Avold in the first week of November. Finally, the 243rd Assault Gun Brigade—really a battalion—was ordered to the Dieuze area and plans were made to relieve the 21st Panzer Division from the Nineteenth Army and send it behind the First Army lines for needed rehabilitation. Both of these units, however, failed to arrive in the First Army zone before the Americans struck.3

During its first weeks in France, General Patton’s Third Army had thrust deep into the Continent. In contrast to this swift campaign, the operations of XII Corps, begun on 8 November and continued through early December, took on the character of a far more conventional type of warfare. The offensive spirit had not changed—but the terrain and the weather had.

After passing the Moselle River and clearing the irregular scarps to the east, the right wing of the Third Army had debouched into the rich farming country of Lorraine. The territory east of the Moselle, called by the French “la Plaine,” was gently rolling, interspersed with irregular watercourses and dotted with forests and hills. Military geographers and historians recognized this area as “the Lorraine gateway,” since historically it had formed a natural route between the Vosges mountains to the south and the western German mountains in the north. But although it permits greater ease of entrance or exit between eastern France and the Rhine Valley than the mountains on either side, the Lorraine gateway also has its barriers. To the east the Sarre River and the lower Vosges act as a curtain connecting the bastions formed by the Vosges and the western German mountains. The Sarre River position in turn is strengthened on its southern flank by the maze of forests, swamps, and lakes in the triangle bounded by Dieuze–Mittersheim–Gondrexange, and on its northern flank by the Saar Heights which rim the Saar Basin.

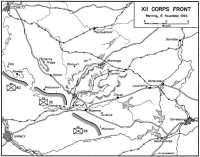

West of the Sarre River and directly in front of the XII Corps lay two long, narrow plateau spurs paralleling the projected American line of advance. (Map 7) These two outcroppings are separated by the Petite Seille River. They are generally known by the names of the most important towns near them—the Morhange plateau in the north and the Dieuze plateau in the south. Perhaps a more accurate identification is furnished by the forests which cover them, since the Forêt de Bride et de Koecking runs nearly the entire length of the Dieuze plateau, and the Morhange plateau is outlined in its southwestern extremity by the Forêt de Château-Salins. Any advance eastward along the valley of the Seille would have to pass under the shadow of the plateau covered by the Forêt de Bride et de Koecking, and any move northeast toward Morhange would be constricted by the two plateaus. To the northwest lies an isolated military barrier known to the Americans as Delme Ridge (Côte de Delme). It has fairly abrupt slopes and dominates the Seille Basin. Delme Ridge has long been recognized as having a prime tactical importance: first, because the Seille River, at its foot, forms a local natural re-entrant running back into the Moselle position; second, because Delme Ridge itself affords observation over the entire area bounded by the Nied and the Seille.

In the years prior to 1914 the French General Staff, under the influence of the Grandmaison school of strategy, planned, in the event of war with Germany, to take the offensive in the first days and strike obliquely, into the

Map 7: XII Corps Front, Morning, 8 November 1944

flank of what the French thought would be the German route of advance, with a double-headed offensive through the Belfort Gap and the southern sector of the Lorraine gateway. On 14 August 1914 the French began this double attack. Four days later, after overrunning the forward German defense line which extended from Delme Ridge via Château-Salins and Juvelize (or Geistkirch) across the Marne-Rhin Canal to Blâmont, the French Second Army (Castelnau) and a part of the First Army (Dubail) were in contact with the main forces of the German Sixth Army, commanded by Archduke Rupprecht of Bavaria. The battle which followed, on 19 and 20 August, is generally known as the Battle of Morhange, although it covered much more terrain than just the approaches to that city. This battle is instructive since the French were faced with most of the tactical problems encountered on the same ground by the XII Corps in November 1944.

Because the Germans in 1914 held Delme Ridge in strength and could readily be reinforced from Metz, Castelnau made no attempt to take the ridge, leaving a reserve infantry division to contain the position and cover his left flank and rear. The 20 Corps, commanded by General Foch, advanced across the Seille between Chambrey and Moyenvic, took the valley route toward Morhange (with its ultimate objective as Faulquemont), skirted the Forêt de Château-Salins, and crossed the western tip of the Forêt de Bride et de Koecking. Initially the enemy opposition in the valley was none too strong and by the morning of 20 August the 20 Corps held a line from Chicourt to Conthil. On the right the 15 Corps attacked diagonally from Moncourt into the Seille valley and after bitter fighting reached Dieuze, which it held for a few hours. Farther to the east the 16 Corps advanced directly north, threading its way through the swamps and forests between Dieuze and Saarburg in an attempt to turn the German position by an attack along the east bank of the Sarre River. The terrain forced the 16 Corps to dissipate its strength in small detachments and the advance finally was brought to a halt in the neighborhood of Loudrefing. Then, as the German artillery began to play havoc with the attackers on the morning of 20 August, the 16 Corps was forced to fall back in a hurried retreat. Now the Bavarians counterattacked all along the front, leaving the cover of the forests and pouring down from the Dieuze and Morhange plateaus, while their heavier guns silenced the French 75’s. Caught in the valleys below, the French could not hold. Castelnau’s army fell back on Nancy and the Grand Couronné, covered by Foch’s 20 Corps which fought a rear guard action near Château-Salins where the two valleys converged. In August 1914 the French were beaten by heavy field artillery, by the machine gun, and by the German possession of admirable defensive positions. In November 1944 the attacker possessed the superiority in matériel—as well as numbers—but the Germans again had the advantage of the ground and in addition were to be favored by the autumn rains.4

The XII Corps plan of attack was ready by 5 November. D Day would be set by General Patton. The scheme of maneuver was simple. Since the area ahead was so broken up by streams, woods, and isolated elevations as to make detailed tactical planning fruitless, General Eddy and his division commanders allowed a free hand to the subordinate leaders who would direct the action on the battleground.5 The three infantry divisions would launch the attack, making a coordinated advance along the entire corps front. The two armored divisions, the 4th behind the right wing and the 6th behind the left, had orders to push into the van and lead the attack as soon as the German forward lines were broken and a favorable position for further exploitation was secured.

In this attack, as in the three-division operation a month earlier, the XII Corps could rely on its tremendous superiority in the artillery arm—a superiority which made initial success certain whether or not the American Air Force was able to support the offensive. The XII Corps artillery fire plan again was elaborate and detailed. Tactical surprise would be sacrificed in order to bring the greatest weight of metal against the forward enemy positions, on which the Germans had worked and sweated for a month past under the glasses of American observers. The seventeen battalions of corps artillery would fire a preparation for three and a half hours (H minus 60 minutes to H plus 150), with twenty battalions of division artillery strengthening the fire during the first thirty minutes. Of the 380 concentrations planned, 190 would be fired on enemy artillery positions; for the most important targets a concentration was charted every three minutes. To thicken this terrific fire the 90-mm. guns of the antiaircraft artillery battalions, the 3-inch guns of the tank destroyers, and the 105-mm. howitzers of the regimental cannon companies were pushed forward close behind the infantry’s line of departure. By 5 November the artillery had completed its registrations, and only just in time, for torrential rains and low-hanging clouds grounded the artillery observation planes and blinded the American observation posts.6

These preparations were reminiscent of the tactics of 1916 and the close coordination then developing in the artillery-infantry team. There was less

unanimity of thought, however, on the use of armor in the coming operation. General Patton believed, and stated this belief at every opportunity, that tanks could easily breach the West Wall, now the big obstacle athwart the route to the Rhine. But many of the veteran junior officers in the armored divisions were less sanguine and privately held the opinion that the armor would be cut to pieces in the maze of antitank defenses ahead. Of greater immediate concern was the problem of tank going in the November mud. Many believed that the campaign was beginning a month too late—a belief shared by infantry and armored officers alike. There was nevertheless considerable optimism among the troops and their leaders, though this optimism was less flaunted than it had been in August and September. Now it was tempered by the long period of inactivity, the mud and the rain, and their exaggerated estimate of the strength of the German West Wall.

Beginning on 5 November, the first date possible for the attack according to Third Army plans, rain fell with only brief intermissions. On 7 November a downpour began that lasted without a break for twenty-four hours. General Patton could wait no longer for flying weather and gave the code words, “Play ball,” which were to begin the XII Corps advance on the morning of 8 November. At nightfall on 7 November the infantry slowly toiled through rivers of mud into position for the attack. So began the Third Army’s education in Napoleon’s “fifth element of war”—mud—bringing for some a personal appreciation of what other Americans had experienced in France a generation earlier. This November campaign would lack the dash and the brilliant successes of earlier operations by the Third Army, but it would record a heroic story of endurance and devotion to duty.

H Hour came at 0600 on 8 November with most of the elements of the three infantry divisions moving forward as had been planned. On the right the 26th Division advanced with the 104th, 101st and 328th Infantry abreast (left to right). In the center the 35th Division, attacking on a narrower front, led off with the 137th and 320th Infantry in line (left to right) and the 134th Infantry in reserve. On the left the 80th Division attacked with the 317th, 318th, and 319th Infantry abreast (left to right). The XII Corps right flank, abutting on the Marne-Rhin Canal, was covered by the 2nd Cavalry Group; its left flank was protected by the XX Corps, whose advance was scheduled to begin on the following day.

The opening bombardment by the massed field artillery battalions smashed the forward enemy positions, destroyed communications, and effectively neutralized

most of the German guns. The XII Corps artillery fired 21,933 rounds in the twenty-four hours from 0600 on 8 November to 0600 of the next day, the gunners using time fire wherever possible because impact fuses often failed to detonate in the mud. Later, as the bad weather abated, planes from the IX and XIX TAC’s swooped down to give close support by striking at woods, towns, and entrenchments.

The infantry advance, in its early hours, found little will to resist among the German grenadiers and machine gunners whose carefully prepared dugouts and trenches had received such a merciless pounding. As always, there were small islands of resistance where a few determined grenadiers held stubbornly in place and forced the attackers to recoil, necessitating the arduous business of outflanking the position or making costly and repeated frontal assaults. Mud, however, slowed the American infantry more than did the German line. The Seille River had flooded its banks, with the highest waters since 1919, and fields and woods along the river channel had turned to quagmires or veritable lakes. But in spite of the mud and cold the infantry moved steadily forward. Over a thousand Germans in the front-line positions were captured in the rapid advance of this first day and a large quantity of enemy equipment was taken or destroyed.

It is impossible to tell to what degree the German troops and commanders were caught by surprise on the morning of 8 November. German intelligence had reported unusual vehicular activity behind the XII Corps lines on the nights before the attack. But the top intelligence officers at Army Group G believed that in all probability the next major American thrust would come in the Thionville sector or between Metz and Pont-à-Mousson. This opinion was reinforced by the continued activity on the XX Corps front, and by the American destruction of the Etang de Lindre dam, which was interpreted as an indication of a purely defensive attitude in the XII Corps sector. OB WEST did not share the view that Patton would make the prospective drive with his left. On 2 November the G-2 at Rundstedt’s headquarters predicted that the Third Army would launch a general attack all along its front—but he did not hazard a guess as to the date. Apparently the enemy front-line troops did not anticipate any immediate danger, for those taken prisoner on the first day said that their positions were regarded as a “winter line,” in which they were to sit out a lull in operations until spring arrived. Possibly there was a division of opinion in the higher German headquarters. There is evidence that at least a few German intelligence officers predicted that General

Patton would launch an attack on 8 November in commemoration of the Allied landings in North Africa on that date two years before; but no last-minute changes were made in the German order of battle to indicate that such a prediction was given any weight.7 In any case it is unlikely that the limited German forces opposite the Third Army could have done more than they did in the face of the first crushing blow of men and metal thrown against them. Most of the German officers who faced the attack of 8 November later agreed that careful preparations and excellent camouflage had won tactical surprise for the Americans.8

The First Phase of the 26th Infantry Division Advance

On the night of 7–8 November the 26th Infantry Division moved up to its attack positions, prepared to carry forward the right wing of the XII Corps in the drive scheduled for the morrow. (Map XXVII) The 104th Infantry assembled opposite Salonnes and Vic-sur-Seille, the assault companies of the 101st concentrated near the “Five Points” on highway 414, which led to Moyenvic, and the 328th faced east toward Moncourt and Bezange-la-Petite. The right flank of the division was covered by a cavalry screen thrown out by the 2nd Cavalry Group, which General Eddy had attached to the 26th to cover the gap between the Marne-Rhin Canal and the main forces of the division. South of the canal the dispositions of the Seventh Army assured a solid anchor on the right of the Third Army base of operations. The left boundary for the 26th Division zone ran from Chambrey through Château-Salins, thus placing Dieuze and the eastern Seille in the division sector, as well as the eastern half of the valley of the Petite Seille which offered a natural route to the town of Morhange. The zone of advance would require that the commanders of the smaller units be given a free hand. The 328th Infantry (Col. B. R. Jacobs), on the right flank of the division, was ordered to make a feint toward Moncourt and Bezange-la-Petite—the obvious route toward Dieuze and the one taken by the French troops in 1914. In the center the 101st Infantry (Col. W. T. Scott) was given the mission of seizing the Seille crossing at Moyenvic. Once across the river the regiment would attack Hill 310 (Côte St. Jean), about 2,400 yards to the north, which formed the forwardmost bastion of the 8½-mile plateau-wall covering Dieuze. The main

Côte St. Jean

assault would be made by the 104th Infantry (Col. D. T. Colley), crossing at Vic-sur-Seille and advancing east of Château-Salins so as to swing into the attack on the north side of the Koecking ridge. Two small task forces, made up of tank destroyers, tanks, and engineers, were added to reinforce the 104th Infantry.9

On the morning of 8 November the 26th Division attack began, moving with speed and élan much as had been planned. At 0600 the American gunfire lifted. The 104th Infantry drove into Vic-sur-Seille and after a short, sharp fight seized some bridges which the outposts of the 361st VG Division had not completely demolished.10 At the same time the 2nd Battalion of the 101st Infantry (Lt. Col. B. A. Lyons) jumped off to take the Seille bridge at Moyenvic, while the 1st Battalion (Lt. Col. L. M. Kirk) made a diversionary attack toward the east near Xanrey. The Moyenvic assault gained complete surprise. Just before dawn the 101st Field Artillery Battalion opened fire on Hill 310 and then “rolled back a barrage” through Moyenvic as the 2nd Battalion attacked. The dazed German garrison yielded 542 prisoners. Company E, stealing forward from house to house, managed to reach the bridge over the Seille before the enemy demolition crew could blow it and crossed the river at once to begin the fight for Hill 310, there joining riflemen of F Company who had swum the river.

This dominating ground was held by troops of the 953rd Regiment and 361st Engineer Battalion, reinforced by six infantry howitzers as well as mortars and machine guns. The forward slopes extended for some fifteen hundred yards, mostly open but dotted here and there with lone trees and small clumps of woods. Company E moved up the slope to the assault, but about five hundred

yards from the top of the hill was stopped by the murderous fire delivered from the German entrenchments on the crest and field guns firing from the village of Marsal. This fusillade cost E Company its commander and several men. Company F, following on the left, lost all of its officers. The two companies crowded together, seeking shelter where they could, and tactical organization soon was lost. All heavy weapons had been left behind to enable the troops to move quickly up the slope; sporadic and uncontrolled rifle fire could not pin the enemy down.

About 1100 G Company was committed, but its commander was hit while crossing the Moyenvic bridge and the company remained on the slope below E and F. An hour later two companies of the 3rd Battalion arrived on the slope in accordance with the timetable earlier arranged for an attack by column of battalions, but the assault could not be started forward again. Here the infantry huddled through the afternoon, the clumps of trees where they sought cover continually swept by cross fire and by German guns on the crest. As dusk came on the enemy guns blasted the slope with a 20-minute concentration, causing heavy casualties and still further disorganizing the American assault force.11 During the night the engineer battalion of the 559th VG Division arrived to reinforce the German hold on the hill.

Although the initial attack at Hill 310 had failed, the 26th Infantry Division generally had been successful in the first day of the new offensive. The 101st and 104th had the Seille bridges securely in hand, while the demonstration toward Dieuze by the 328th Infantry had pushed the American lines past Bezange-la-Petite and Moncourt, pinning at least six companies of the 952nd Regiment to the defense of this sector, although with heavy cost to the attackers.12

Now the 26th Division began a three-day battle to maneuver around Hill 310 and pivot onto the Koecking ridge. The weather suddenly had turned cold; snow and rain fell on 9 November. The 101st Infantry, whose men had shed even their field jackets in the assault on Hill 310, suffered particularly, and exposure started to reduce the already weakened rifle strength on the slopes. Carrying parties could reach the 101st only through a deadly cross fire, and food had to be sacrificed for ammunition. Cold, hungry, with its ranks thinned and many of its officers casualties, the 101st tried to envelop the enemy positions on the crest. On the morning of 9 November the 1st Battalion, which had skillfully disengaged at Juvrecourt and come up through Moyenvic during the night, attempted a double envelopment but was stopped in its tracks by the German fire and by the mud which bogged down its supporting tanks at the base of the hill. The 3rd Battalion finally dispatched two companies in an attack north up the ravine toward Salival, a little hamlet from which enemy machine gun fire enfiladed the western slope. At dark Salival was taken and the American infantry passed into the woods beyond, where German trenches, strongly manned, covered the flank and rear of the 953rd positions atop Hill 310.

Meanwhile the 104th Infantry, which had moved to flank Château-Salins in conjunction with the 35th Division attack toward the Forêt de Château-Salins, fought its way into this key town. On 9 November the troops from the 559th VG Division which were holding Château-Salins were ejected by the 104th, and the right flank of the regiment was extended to Morville-lès-Vic in an attempt to put troops on Koecking ridge behind Hill 310. Morville was taken about 1500 by one of the task forces (Task Force A) attached to the division. Company K, 101st Infantry, cleared the town in a house-to-house fight, after the lead tank of a platoon from the 761st Tank Battalion was knocked out by a bazooka, blocking the narrow road into the town and forcing the infantry to go it alone. Then the little task force continued on toward Hampont, its progress slowed by mud and antitank fire. Capt. Charles F. Long, the K Company commander, was killed and half of the infantry company was lost in this fight.

The infantry had borne the burden of the attack on 9 November. Visibility was poor for the supporting gunners. Many of the artillery liaison planes

were grounded, some of them standing in water up to their wings. Not only was the artillery blinded to the point where it could give only limited support, but the air cooperation which had played such an important role in earlier operations also was drastically curtailed. The IX Bombardment Division sent 110 bombers to attack Dieuze, but because of the murky weather only 29 aircraft arrived over the target.

Nonetheless the left wing of the 26th Division had driven far enough to clear the way for intervention by the armor and, without realizing it, had forced a wedge between the left wing of the 559th and the right wing of the 361st.13 On the night of 9 November General Eddy ordered CCA, 4th Armored Division, to attack on the following morning. At 1055 CCA (now commanded by Lt. Col. Creighton W. Abrams) began crossing over the Seille bridges en route to Hampont. But the appearance of the American tanks had no immediate effect on the battle still being fought for the possession of Hill 310.

The 1st Battalion of the 101st Infantry continued to work its way around Hill 310 on 10 November. About 1610 Colonel Scott gave the order to assault the ridge behind the hill. This assault was the turning point in the fight for a foothold on the Koecking plateau. Company C, attacking with marching fire behind a curtain of shells, succeeded in pushing the Germans off the ridge northeast of Hill 310. A company of enemy infantry counterattacked immediately, but C Company beat off the attack, although it was badly mauled; it then dug in while the German gunners took over the fight and tried to shell the Americans out of the position. The rest of the 1st Battalion swung around to the left, into the Bois St. Martin, and reached out to meet the 3rd Battalion, which the day before had wheeled in a wider arc to move onto the Koecking ridge. The 3rd Battalion literally blasted its way out of the thick, dark woods and on 11 November reached a road junction south of Hampont, where about a hundred Germans were captured.14 Then the 3rd Battalion turned back on the main ridge line to meet the 1st Battalion. On the same day, the 1st had finally driven the enemy off Hill 310 and from this vantage point was now directing the American batteries in counterfire against the German guns at Marsal and Haraucourt-sur-Seille in the valley below. Firmly astride the Koecking ridge, the 26th Division could begin the slow and costly process of fighting step by step to clear the Koecking woods, displace

the enemy on the plateau, and seize the villages in the valleys and on the slopes. The 26th Division, however, already was understrength. The fight for Hill 310 alone had cost 478 officers and men, dead and wounded.15

Initial success in the penetration by CCA, 4th Armored Division, in the Hampont sector offered some possibility for maneuver by the 26th Division’s left. On 11 November, therefore, General Paul switched the 328th Infantry to the center of the division zone—on top of Koecking ridge—sent the 104th Infantry in on the left to support CCA in the drive toward Rodalbe, and turned the 101st to the east in an advance along the southern slopes of the Koecking ridge.

The CCA Attack along the Valley of the Petite Seille

The 4th Armored Division entered upon the November campaign as one of the crack armored divisions in the American armies in Europe. It was now a thoroughly battle-wise division, imbued with a high degree of confidence as a result of the successful tank battles in late September, with relatively few green replacements, and with nearly a full complement of tanks and other vehicles. However, the 4th Armored, as well as General Patton’s other armored divisions, was faced with a combination of terrain and weather which promised very bad tank going and which would inevitably restrict the mobility that had distinguished American armored formations in preceding months. During the final phase of the November operation the 4th Armored Division would be handicapped also by the fact that the right boundary of the Third Army continually was subject to change, making it necessary for the division constantly to alter its axis of advance in order to stay within the proper zone, and even, on occasion, to double back on its tracks.16

General Wood appears to have suggested that his entire division be used in an attack through the Dieuze defile, along the Moyenvic–Mittersheim road. General Eddy did not favor this plan because reports from the corps cavalry indicated that a considerable German force had been gathered to hold the narrow avenue through the Dieuze bottleneck.17 Furthermore, Mittersheim, the Dieuze road terminus, lay inside the projected Seventh Army zone. General

Eddy and his staff considered putting the 4th Armored Division through north of Château-Salins as the spearhead of the XII Corps advance. But General Patton’s decision to add the 6th Armored Division to the XII Corps for the November offensive necessitated a regrouping of Eddy’s armored strength. In the final plan the 4th Armored Division was given a “goose egg” on the map, covering the Morhange area, as an initial objective. Its additional and very tentative assignment was to continue the offensive in the direction of Sarre-Union and the Sarre River crossings there. In this plan it was intended that CCA would advance on the right, pass through the 26th Division, attack northeast along the valley of the Petite Seille, bypass Morhange, and strike out along the Bénestroff–Francaltroff road. CCB meanwhile would circle to the north of the Morhange plateau, in order to free the one good road through the valley of the Petite Seille for CCA, and capture the vital road center at Morhange. Both combat commands would have to contend with the lack of hard-surfaced roads in the area. As a result the routes finally followed consisted of a series of zigzags and cutbacks—the whole further complicated, as events showed, by the movement of supply and transport for the infantry divisions on these same roads.

On 9 November CCB (Brig. Gen. H. E. Dager) jumped off through the 35th Division bridgehead.18 The following day CCA entered the attack, Colonel Abrams19 passing his lead column (Major Hunter) through the 104th Infantry, which was fighting the rear guard of the 559th near Morville. Hunter’s column moved slowly, since even the limited enemy resistance encountered at road blocks along the way caused delay and confusion. Maneuver generally was impossible. Tanks and trucks that went off the black-top surface of the main highway had to be winched out of the quagmire. Hunter’s tanks drove through Hampont before dark on 10 November, but CCA’s second column (Lt. Col. Delk M. Oden) was unable to make a start along the crowded roadway and did not reach Hampont until the close of the next day.

Hunter’s column fought its way toward Conthil on 11 November but ran into serious difficulty south of the village of Haboudange, where a battalion of the 361st VG Division and the 111th Flak Battalion had assembled in preparation for a counterattack to regain contact with the retreating 559th.20

Task Force Oden leaving Château-Salins, on the morning of 11 November

At this point the road passed through a narrow defile formed by the river on one side and a railroad embankment on the other. As the column entered the defile hidden German dual purpose guns opened fire. The leading tanks were knocked out, blocking the road and bringing the column to a halt. Four American officers were killed, one after another, as they went forward to locate the enemy gun positions. Finally Hunter turned the column back and continued the move by a side road, bivouacking that night between Conthil and Rodalbe, while two companies of the 104th Infantry outposted the latter village. Progress had been slow this day, impeded by the German antitank guns and minor tank sorties, but Hunter’s column had destroyed fourteen enemy guns and three tanks—although at considerable cost in American dead and wounded.21

The next morning Oden’s column drew abreast of Hunter, with the 2nd Battalion of the 104th Infantry (the regiment was now commanded by Lt. Col. R. A. Palladino) following in support. Oden turned off the main road and took Hill 337, southeast of Lidrezing, a commanding height that overlooked the enemy positions along the path of advance eastward. About noon Hunter’s column reached Rodalbe, which had been occupied the previous evening by K and L Companies of the 3rd Battalion (Lt. Col. H. G. Donaldson), and started north toward Bermering with the intention of cutting off the troops of the 559th VG Division now retreating in front of CCB and the 35th Division. However, the enemy had had enough time to prepare some defense and the road north of Rodalbe had been thoroughly mined. While the tanks of the 37th Tank Battalion were trying to maneuver off the road in order to avoid the mines, a number became hopelessly mired and an easy target for the German guns which opened up from the north and from the Pfaffenforst woods. Hunter’s column was forced to fall back under the rain of shells and took cover in the Bois de Conthil, about a thousand yards west of Rodalbe.

The enemy was ready to capitalize on the thin, elongated outpost line held by the 104th Infantry. On 10 November Balck finally had committed his armored reserve, the 11th Panzer Division, against the left and center of the XII Corps, and by 12 November the German tanks were in action along a 12-mile front. The width of this front made any linear defense impossible and Wietersheim was forced to rely on a mobile defense, counterattacking wherever

Rodalbe

opportunity availed. Wietersheim had sent his reconnaissance battalion, ten Panther tanks, and a battalion of the 110th Panzer Grenadier Regiment to support the elements of the 559th VG Division in the Rodalbe sector and restore the connection between the XIII SS Corps and the LXXXIX Corps. This combined force unleashed a full-scale counterattack on the heels of Hunter’s withdrawal. The American artillery broke up the first attack aimed at Rodalbe on the afternoon of 12 November; but back to the west the enemy surrounded two companies of the 1st Battalion of the 104th in the neighborhood of Conthil—only to lose his intended prey when the Americans fought their way out of the trap.

The next morning the Germans launched an infantry attack against the 3rd Battalion troops in Rodalbe but were repulsed. Just before dusk the enemy returned to the attack after extremely accurate counterbattery fire had effectively neutralized the American artillery. The German grenadiers pushed into the town from all sides and their tanks followed down the Bermering road. A 28-man patrol from the 2nd Battalion, 104th, succeeded in entering the town with orders for the 3rd Battalion troops to withdraw, but it was too late. The 2nd Battalion patrol became engulfed in the fight and only one officer and three men returned to report the fate of the Rodalbe force. Company I, the regimental reserve, by this time reduced to twenty-three men, tried to force a way through to relieve the trapped companies; but the German tanks now held all the entrances to Rodalbe. West of the village Panther tanks, mines, and antitank guns barricaded the highway against an attack by the American tank battalion in the Bois de Conthil. Actually the mud and the darkness prevented any such intervention. Inside the village the American infantry took refuge in cellars and attempted to make a stand, but civilians pointed out their hiding places to the enemy tankers who blasted them with high explosives at short range. A few Americans escaped during the night; two officers successfully led thirty men of M Company back to the American lines. But some two hundred officers and men were lost in Rodalbe, although a handful of survivors were found in hiding when the village finally was reentered on the morning of 18 November.22

The reverses suffered on 12 November brought CCA and the 104th Infantry to a halt. Hunter’s force was placed in reserve, while waiting for new

tanks to replace those lost by the 37th Tank Battalion, and Oden detached a task force which recaptured Conthil and opened the main supply route back through the valley. The 104th Infantry, now badly understrength, took up positions along the arc made by the Conthil–Lidrezing road. This whole line formed a salient in which the weakened 104th Infantry “stuck out like a sore thumb,” with CCB and the infantry of the 35th Division on the left flank stepped back along the railroad line between Morhange and Baronville, and the balance of the 26th Division advancing slowly and painfully to the right and rear along the Koecking ridge.

The Fight for the Koecking Ridge23

Since the 101st Infantry had been badly cut up during the fight for Hill 310, General Paul committed the 328th Infantry in the center of the division zone to carry the main burden of clearing the forest atop the Koecking ridge. He added the 3rd Battalion of the 101st Infantry to the left flank of the 328th in order to strengthen the attack. The woods ahead were mostly beech, still covered with leaves that gave the forest a dark and somber aspect even during the light of the short November days. Dense copses of fir trees within the forest formed cover for machine gun positions and for snipers. Mines, booby traps, barbed wire, and concrete pillboxes reinforced the old zigzag trench positions of World War I. Nor had the attackers escaped the mud; even on this plateau the forest floor had turned into a bog under the constant rain. There were numerous trails and clearings, but the most important avenues of advance were a steeply banked east-west road, which traversed the entire length of the forest, and a lateral road running from Conthil to Dieuze, which had been prepared by the Germans as a reserve battle position. The enemy force there deployed to meet the 328th was small, consisting of the 43rd Machine Gun Battalion and the 2nd Battalion of the 1119th Regiment (some elements of the 553rd VG Division had been taken over by the 361st VG Division). Nevertheless, these units were veterans, skilled woods fighters, and well entrenched on ground with which they were familiar.

The 328th Infantry started east through the forest on the morning of 12 November and at first encountered little opposition. Shortly after noon the advancing skirmish line reached an indentation in the woods made by a large

clearing around Berange Farm. Here small arms fire from German pillboxes, reinforced by a very accurate artillery concentration, brought the advance to an abrupt halt and wounded the regimental commander, Colonel Jacobs. The 2nd Battalion, which had reached another large quadrangular opening in the woods southeast of Berange Farm, was hit by a sudden hail of mortar fire as it entered the clearing. Many were killed, including the battalion commander, Maj. R. J. Servatius, who had taken over the battalion only the night before. The Americans rallied all along the line, however, and by 1530 the German defenders had been driven back. The strong point at Berange Farm was cleared after 120 rounds of artillery were poured in on the farm buildings.

Now the night turned cold and snow fell on the foxholes in the sodden forest. The infantry had left their blankets behind during the attack. After the day of severe fighting, exposure also took its toll.

South of the woods the 1st Battalion of the 101st embarked on an attack to take St. Médard. Here the open ground was swept by cross fire from the edge of the forest and from the enemy guns at Dieuze, which for three hours shelled the attack positions of the 101st and inflicted severe losses. General Paul then called off the 101st advance until the 328th could outflank the St. Médard position from the north.

On 13 November the German batteries in Dieuze became even more active, and the 328th, advancing along the east-west road, found itself under almost constant shelling. Early in the day the advance was slowed down by fire from automatic weapons sited in the underbrush. Tanks and tank destroyers advancing along the east-west road gradually blasted the Germans out of the woods on either side and by nightfall the skirmish line was abreast of the lateral highway. The progress of the 328th had carried it well ahead of the 101st (-), still held up at St. Médard and Haraucourt, and the 328th found enemy pressure increasing on its exposed right flank. The 26th Division was slowing down, with its rifle companies much below strength and its flanks contained by a stubborn enemy. The 101st Infantry had just received some 700 replacements, but it would require time for so many new officers and men to learn their business. The 328th Infantry had lost many battle casualties in the forest fighting, but exposure had claimed even more victims: over five hundred men were evacuated as trench foot and exposure cases in the first four days of the operation. The 104th was even weaker. Its rifle companies averaged about fifty men; in the 1st Battalion some company rosters

showed only eight to fifteen effectives. Said an officer of the 104th: “All through this I think we were taking a worse beating than the Jerries. They fought a delaying action, all the way. When things got too tough they could withdraw to their next defense line. And when we sat for awhile, they pounded us.”

This bitter fighting had been done at high cost to the enemy as well. The weak German battalions, although reinforced by the 2nd Battalion of the 953rd Regiment and a Luftwaffe engineer battalion, could hold no position for any great length of time. On 14 November CCA made a sweep through the Bois de Kerperche, the northeastern appendage of the Koecking woods, and this pressure on the German flank and rear helped pry loose the enemy grip on the Koecking ridge. The 328th, reinforced by the 3rd Battalion, 101st, put its weight into an attack on 15 and 16 November which drove straight through to the eastern edge of the woods. Little fighting was involved, for most of the enemy had withdrawn on the night of 14–15 November. At the same time the 101st Infantry and 2nd Cavalry Group pushed toward Dieuze, following the enemy who were now in full retreat. On 17 November the 26th Infantry Division regrouped, parceled out new batches of replacements to the 104th Infantry, issued dry clothing, and prepared to attack the next German position.

Meanwhile the enemy undertook a general withdrawal in front of the 26th Division; concurrently Balck shifted the bulk of the German artillery, which had played so important a role, northward for use against the XII Corps left and center. The new enemy line, facing CCA and the 26th Division, followed the railroad spur between Bénestroff—an important railroad junction east of Rodalbe—and Dieuze. This position had little to offer in natural capabilities for defense, except on the north where woods and hills masked Bénestroff. But solid contact had again been established on the right with the 11th Panzer Division.

Task Force Oden Attacks Guébling

Colonel Oden’s column, CCA, 4th Armored Division, made the initial attempt to penetrate the new German position between Bénestroff and Dieuze. Oden’s objective was Marimont-lès-Bénestroff, a crossroads village about one and a half miles southeast of Bénestroff. A passable road led out of the

Guébling. Circles indicate wreckage of German tanks

Koecking woods through Bourgaltroff to Marimont, avoiding the hills and woods around Bénestroff. This road intersected the German line at the village of Guébling, about four miles north of Dieuze, which would be the scene of the first American assault.

Leaving Hunter’s column to cover the exposed flank and rear of CCA, Oden’s column, divided into two task forces, struck out from an assembly area near Hill 337 at first light on the morning of 14 November. Task Force West skirted the Bois de Kerperche and moved by a secondary road southeast toward Guébling. Task Force McKone took a route directly through the woods, which had not yet been cleared of the enemy by the advance of the 328th Infantry, but found the forest road so heavily mined that it was forced to turn back. About 0845 Major West’s force encountered six Panther tanks which had taken position among the buildings at Kutzeling Farm on the road to Guébling. These tanks belonged to a detachment of ten Panthers that General Wietersheim had dispatched from the 15th Panzer Regiment as a roving counterattack formation. For nearly six hours the German tanks fought a stubborn rear guard action along the road to Guébling, using the long range of their high-velocity 75-mm. guns to keep the Americans at bay. After much maneuvering at Kutzeling Farm, West’s tanks closed in and disabled three of the Panthers. The rest escaped under a smoke screen. Later in the day five Panthers made a stand just west of the railroad, where a corkscrew road out of the forest dipped abruptly toward Guébling. Again the Panthers showed themselves impervious to long-range fire from the American M-4’s and supporting 105-mm. howitzers, and again maneuver was used to bring the Panthers within killing range. Fortunately, the German tanks were so closely hemmed in by their own mine fields as to be virtually frozen in position. Snow and rain precluded an air strike by the fighter-bombers, but finally an artillery plane managed to go aloft and adjust fire for the 155-mm. howitzers of the 191st Field Artillery Battalion. This fire forced the Panthers to close their hatches, and A Company of the 35th Tank Battalion charged in on the flanks of the partially blinded Germans. Leading the attack, 1st Lt. Arthur L. Sell closed within fifty yards of two Panthers and destroyed them, although two of his crew were killed, two seriously wounded, and his own tank was knocked out.24 Sell’s companion tanks finished off the remaining Panthers, and as the afternoon drew to a close Task Force West rolled into Guébling.

The village itself was quickly secured, but the short November day gave no time for the armored infantry to take the high ground and the German observation posts that lay beyond.

Next morning about 0300 three gasoline trucks came into the village to refuel the task force. The sound of movement inside Guébling reached the enemy observation posts and brought on the worst shelling the American troops had yet experienced. The gasoline trucks were destroyed and several tanks and other vehicles were damaged. Early in the morning Task Force McKone arrived to strengthen the detachment in Guébling, and at daylight the 10th Armored Infantry Battalion was thrown into an attack to clear the high ground beyond the village. The armored infantry pushed the attack with vigor and determination but were beaten back by the German gunners. American counterbattery fire failed to subdue the enemy batteries, the guns shooting blindly into a curtain of snow and rain.

About noon the 4th Armored Division commander ordered Colonel Oden to withdraw from the precarious position in Guébling and return to the original assembly area at Hill 337. Oden evacuated his wounded, destroyed his damaged vehicles, and gave the order to withdraw. By this time the German guns had ranged in on the exit road running back to the west and the Americans were forced to run a 1,500-yard gauntlet of exploding shells, with only the cover provided by a smoke screen. Oden’s command finally extricated itself, suffering “severe losses” in the process, and rejoined the 26th Infantry Division. This venture had cost the armor heavily—the 35th Tank Battalion had only fifteen tanks fit for battle—and on 16 November General Wood gave orders putting an end to independent attacks by elements of the 4th Armored Division.25

The Attack by the XII Corps Center

On the eve of the November offensive the 35th Infantry Division was deployed with the 134th Infantry (Col. B. B. Miltonberger) on the right, holding the Forêt de Grémecey, and the 137th Infantry (Col. W. S. Murray) on the left, aligned along the ridges running from the Forêt de Grémecey to the 80th Division boundary northwest of Ajoncourt. At H Hour on 8 November the 320th Infantry (Col. B. A. Byrne) was scheduled to pass through

the lines of the 134th Infantry, the latter going into division reserve while the 320th made the attack. (Map XXVIII) As elsewhere in the XII Corps no detailed plan had been laid down for the division scheme of maneuver except to set a line through Laneuveville-en-Saulnois, Fonteny, and the southwestern section of the Forêt de Château-Salins as the initial objective. Once the 35th Division had achieved a hold on the terminus of the Morhange plateau and the 26th Division had broken through the enemy on the right, the entrance to the valley of Petite Seille would be open for a thrust by CCA, 4th Armored Division. CCB, assigned to work with the 35th Division, was to pass through the attacking infantry as quickly as possible and advance toward Morhange, while the infantry followed to take over successive objectives softened up by the armor. General Eddy also foresaw some possibility that the 6th Armored Division, teamed with the 80th Division on the left, might find a weak spot in the German line and ordered General Baade to put his reserve regiment in trucks, prepared to exploit a break-through by either the 6th Armored Division or CCB of the 4th.

The rain had been pouring down steadily for five hours by 0600 (H Hour) of 8 November, flooding the roads and footpaths along which the 320th Infantry was moving to its line of departure. Before day broke and the line of departure was reached, the assault troops on the right already were tired and gaps appeared in the ranks as stragglers fell behind. However, most of the formations slated to make the attack were able to jump off close to schedule.

The 137th Infantry, on the division left, had as its mission to establish a bridgehead across the Osson Creek and make a quick jab at Laneuveville, some four miles distant, in order to cut the main highway between Château-Salins and Metz. In September, when the 35th Division had fought along its banks, the Osson had been no more than a small stream. Now the flood waters of the sluggish Seille had backed into the creek, increasing its width to about fifty yards and making it a real barrier. The engineers had prepared for this obstacle, however, and by 1040 the attackers had put a prefabricated bridge across south of Jallaucourt. Two hours later the 1st Battalion of the 137th, supported by tanks of the 737th Tank Battalion, was in the shell-torn village itself. The enemy soldiers froze in their places at sight of the tanks and surrendered. A second bridge opened the road into Malaucourt, and shortly after 1600 two companies of the 2nd Battalion, supported by tanks, took the village. By midnight the 137th Infantry was in position on the ground rising east of the two villages, having taken some two hundred prisoners (mostly from

the 1125th Regiment of the 559th VG Division) at a cost of eighty-two casualties.26

On the right wing of the 35th Division the 320th Infantry attacked to secure a foothold in the Forêt de Château-Salins on the Morhange plateau, in conjunction with the 26th Division attempt to gain a position on the Koecking ridge. The only road that led from the 35th Division area into the Forêt de Château-Salins was blocked by the German possession of Fresnes, about 1,200 yards north of the 35th Division lines. Until Fresnes was taken and the road eastward cleared, no tanks could be used in support of the 320th Infantry attack on the forest, and supply had to be made by carrying parties wallowing up to their knees in mud. Apparently the Americans had hoped to clear Fresnes by a quick stroke and thus open the vital roadway in time to send the tanks into the forest edge in conjunction with the infantry assault. But the German hold on Fresnes was far more tenacious than on the villages in front of the 137th Infantry. Fresnes had been an important supply and communications center for the enemy in earlier operations and had received constant and heavy shelling by the American artillery. As a result the German garrison, estimated to be a battalion, had dug in deep and was little disturbed by the heavy shelling on the morning of 8 November. When the fire lifted, the garrison rose to meet the American attack. The 3rd Battalion, 320th Infantry, and a company of tanks succeeded in entering Fresnes after a bitter fight; but all during the night and for part of the next day the German defenders fought on, barring the road into the forest.

While the 3rd Battalion hammered at Fresnes, the 2nd Battalion, on its right, began a frontal attack toward the western extension of the Forêt de Château-Salins known as the Bois d’Amélécourt—only to suffer a series of costly mishaps in this first day of the offensive. The assault troops of the 320th Infantry had had to pass through the lines of the 134th Infantry during the night of 7–8 November. This move, difficult enough under favorable conditions, was further complicated by the seas of mud, and the two companies leading the attack arrived on the line of departure at the northeast edge of the Forêt de Grémecey a half hour late, their rifle strength already depleted by stragglers who had fallen out along the way or been lost in the woods.27

When the 2nd Battalion finally moved into the attack, daylight already had come and the smoke screen which had been fired for ten minutes before daylight was beginning to dissipate—leaving little cover as the companies started to cross some two thousand yards of muddy ground. The Bois d’Amélécourt was held by a battalion of the 1127th Regiment, whose northern flank in turn was covered by a battalion from the 1125th Regiment. The Germans in the woods held a strong position on the higher ground and were supported by three infantry howitzers that had been wheeled forward to the tree line so as to cover the open ground over which the Americans had to attack. In addition the highway passing in front of the woods had been wired and mined as a forward defense position, and was further strengthened with machine guns sited in enfilade.

The Americans crossed the first few hundred yards of open ground without drawing much fire. Company G, on the left, reached the enemy outpost line, which here followed a railroad embankment, and took some forty Germans from their foxholes. Beyond the railroad F Company drew abreast of G Company and the two started toward the woods. When the first assault wave reached the wire along the highway the guns and mortars in the woods opened fire, while the German machine guns swept the American right flank. Under this hot fire Company F fell back, until rallied by a battalion staff officer. Company E, the reserve, attempted to intervene but also was repelled by the German fire. Company G, somewhat protected by a slight rise, reached the edge of the woods and hurriedly dug in. During the afternoon the two rifle companies still outside the woods made a second effort. In the midst of the assault the American batteries firing smoke in support of the infantry ran out of smoke shells, and as the smoke screen blew away a fusillade poured in from the German lines. Again the attack was brought to a halt and the two companies withdrew to the cover of the railroad embankment. The 2nd Battalion had suffered severely but was saved from complete destruction by the mud, which absorbed shell fragments and in which the German shells, fitted with impact fuses, often failed to explode.

In the late afternoon Colonel Byrne ordered the 1st Battalion of the 320th Infantry up from reserve to close the gap between Fresnes and the Bois d’Amélécourt. Mine fields slowed down the battalion, however, and when darkness fell it halted at the Fresnes road. During the night of 8–9 November the 3rd Battalion mopped up the enemy still holding on around Fresnes. The

2nd Battalion sent carrying parties back to evacuate the wounded and bring up ammunition, which had run low during the fire fight in the afternoon. This still further depleted the rifle strength opposite the enemy; indeed it is characteristic of most of the woods fighting in November that a considerable part of the roster of every unit had to be detached from the fire line to keep communications to the rear functioning over terrain where vehicles could not be used.

When morning arrived on the second day of the battle the engineers cleared the mines from the road east of Fresnes and the 1st Battalion marched to the aid of the 2nd Battalion. Company C, 737th Tank Battalion, which had played a major role at Fresnes, followed behind the infantry, although it was seriously crippled and had lost six of its tanks in the fight for the village. Meanwhile the 2nd Battalion resumed the attack on the Bois d’Amélécourt. Two of the troublesome German howitzers had been knocked out by the American artillery, but the enemy machine guns still were in position to rake the American flank. Once again the attack was broken by the withering fire and this time the dispirited infantry could not be induced to return to the assault. About 1000 the tanks from Fresnes arrived on the scene. Their appearance abruptly shifted the balance against the enemy. The tank gunners quickly destroyed the German machine gun nests and drove the enemy back from the edge of the woods, putting the 1st and 2nd Battalions inside the tree line.28

Once inside the woods, however, the infantry found the enemy cleverly entrenched and determined to fight for every yard of ground. Barbed wire, prepared lanes of fire, dugouts roofed with concrete and sod, foxholes, and breastworks improvised from corded wood provided an intricate net of field works facing the attackers wherever they turned. Once again the German grenadier proved himself an experienced and resourceful woods fighter, clinging obstinately to each position and closing to fire rifle grenades and even antitank grenades point blank at the American infantry. Significant of the stubbornness with which the defense was conducted, the enemy left more dead than prisoners in American hands.29

On the north flank of the 35th Division the rapid advance made by the 137th on the first day of the attack offered an opening for armored exploitation.

Wounded soldier helped to aid station, after fighting in the Forêt de Grémecey

General Eddy committed CCB, 4th Armored Division, on the morning of 9 November, sending it wheeling north of the Forêt de Château-Salins in a drive toward Morhange. General Dager, CCB commander, followed the usual practice of the division and attacked in two columns: the left column (Maj. Thomas G. Churchill) passed through the 137th near Malaucourt; the right column (Lt. Col. Alfred A. Mayback) struck into the open near Jallaucourt. The enemy had not recovered from the brusque attack made by the American infantry on the previous day and could present little in the way of a coordinated defense against the armored columns. Churchill’s column was able to stick to the highway, though five medium tanks were lost to mines, and reached the village of Hannocourt. Here the enemy had emplaced a few antitank pieces to cover the road, but the 510th Squadron of the XIX TAC, flying cover over the American tanks, blasted the German gun positions with fragmentation bombs and napalm. Churchill’s advance uncovered the southern flank of the 48th Division position at Delme Ridge—directly in front of the 80th Infantry Division—and enabled the 137th Infantry to capture the village of Delme, an attack made in conjunction with the 80th Division assault against the ridge itself.30

On the right Colonel Mayback’s column met much stiffer opposition but moved speedily ahead despite concrete road blocks, antitank gunfire, and the necessity of having to halt and clear German foxhole chains alongside the road. At first the troops of the 559th were slow to react to the appearance of the American armor deep inside their lines. At Oriocourt the 1st Battalion of the 137th Infantry, following close behind the tanks, bagged a battery of field guns and 150 prisoners. At Laneuveville the American tanks overran the enemy guns before the startled crews could get the covers off their pieces. The supporting infantry captured 445 prisoners with only slight losses in their own ranks. While the infantry mopped up in Laneuveville Mayback’s armored column moved east toward the village of Fonteny. In midafternoon the American advance guard had just begun to descend the road into the draw where the village lay when suddenly enemy guns opened fire from positions on a hill northeast of Fonteny and from the Forêt de Château-Salins. The Americans had run into a hornet’s nest: this was a prepared secondary position which had been heavily armed in early November by guns from the 9th

Task force Churchill crossing the Seille river

Flak Division.31 Having brought the column to a halt the enemy struck with a detachment of tanks against the American flank. A lieutenant and a small party of armored infantrymen equipped with bazookas drove off the German tanks, though nearly all of the little detachment were killed or wounded during the fight.

Meanwhile, Colonel Mayback sent forward C Company, 37th Tank Battalion, to help the advance guard. The main body of the column had been somewhat protected by a small rise of ground, but the moment the company of medium tanks crossed the sky line three tanks were knocked out. When C Company attempted to deploy off the road the tanks bogged down, presenting more or less a series of sitting targets for the German gunners. Nevertheless C Company inflicted considerable damage on the German batteries (it was later estimated that the tanks had put thirty German guns out of action) and continued the duel until the ammunition in the tanks was expended. As night

fell Colonel Mayback ordered his forward elements to withdraw behind the ground mask southwest of the village. The American losses, mostly sustained in the fight outside of Fonteny, had been heavy: fifteen tanks, ten half-tracks, and three assault guns. But the column had made an advance of some four miles into enemy territory and had broken a way for the infantry.32

When word of the fight at Fonteny reached General Dager the CCB commander ordered Mayback to hold up his advance and wait for reinforcements from Churchill’s column, bivouacked near Hannocourt. The marching American infantry was still about five miles behind the armored columns. During the night of 9–10 November enemy infantry and tanks from the 11th Panzer Division cut in behind Churchill’s force and occupied the village of Viviers, thus severing the only usable road to Fonteny. This German force was fairly strong, including troops of the 43rd Fortress Battalion and the 110th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, as well as a large number of self-propelled guns. The fight to clear the enemy from Viviers on 10 November developed into a series of confused actions. The 22nd Armored Field Artillery Battalion, located on Hill 260, halfway between Viviers and Hannocourt, entered upon an old-fashioned artillery duel with some batteries of the 401st Volks Artillery Corps to the north which were harassing Churchill’s column. The American tanks attempted to open the road to Viviers but were forced off the highway by the enemy antitank guns and mired down in the boggy fields.33 The 2nd Battalion, 137th Infantry, which had come up from the west, then carried the attack into Viviers in a battle that continued through the entire afternoon.34 At dusk the infantry secured a firm hold on the village, after a heavy shelling had somewhat softened up the enemy garrison. More than one hundred dead Germans were counted in the streets and houses and some fifty surrendered, but a small and desperate rear guard detachment held on in the burning village through most of the night.

The 35th Division fought a punishing battle all along its front on 10 November and only slowly eased the enemy pressure on CCB. While the 2nd Battalion of the 137th Infantry attacked at Viviers, other elements of the regiment pushed past Laneuveville and joined Mayback’s column west of

Fonteny, there extending the flanks of the 51st Armored Infantry Battalion which had been thrown out as a screen for the armor. During the day the Germans directed one small tank attack against Mayback’s command, but this was repelled handily by the American tank destroyers.

In the center of the division line the 320th Infantry passed from the Bois d’Amélécourt and continued the fight in the mazes of the Forêt de Château-Salins, its men soaked to the skin and harassed day and night by enemy detachments that slipped through the woods like Indians in raids on the flanks and rear. German reinforcements were coming in from the 1126th Regiment and the 110th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, bringing the numbers on each side to something approaching equality. The 3rd Battalion relieved the 2nd Battalion, as the fighting strength of the latter diminished, but even when placed in reserve the tired American infantry had to battle heavily armed German patrols sneaking through the fragmentary front lines. General Baade had put the 134th Infantry in on the right of the 320th Infantry, on 9 November, with the mission of clearing the eastern edge of the Forêt de Château-Salins and covering the division’s flank. Here, too, the Germans stubbornly contested the ground; by the night of 10 November the regiment still was short of Gerbécourt, only a third of the way alongside the forest.

Resistance in the Forêt de Château-Salins began to slacken on 11 November, and during the afternoon the 559th commenced a general withdrawal toward a line between Frémery and Dalhain, giving the fighter-bombers an appetizing target as the columns of infantry and horse-drawn artillery debouched into the open. The 365th Squadron destroyed fifty-eight guns and vehicles in a single sweep. No continuous front line remained—only German rear guard detachments holding out grimly at points of vantage. Their stand, coupled with the miserable conditions of the roads and early darkness, made the 35th Division advance a slow affair. Both the 320th and 134th Infantry made some progress, but both were beset by the difficulty of getting food and ammunition forward through the rivers of mud.35

On the left of the division, resistance briefly increased in front of CCB and the 137th Infantry, and shellfire poured in as the German artillery sought to halt the American advance long enough to permit the troops in the Forêt de Château-Salins to escape. Early in the day a counterattack was thrown at

Churchill’s force, which had been ordered to continue toward Morhange, only to be dispersed by the armored artillery. During the day the column destroyed fourteen antitank guns yet was unable to fight its way clear of the Bois de Serres, through which the main roads to Morhange passed. The Mayback column made an attempt to drive straight through Fonteny but was beaten back by direct antitank fire at close range. Meanwhile the 1st Battalion, 137th Infantry, and a tank company had come up to aid in the assault and another attempt was made with an attack in deployed order. Shortly after noon the Americans entered the little village, and the fight continued from house to house all during the afternoon and through most of the night. During this action Colonel Mayback and Lt. Col. William L. Shade, commanding officer of the 253rd Field Artillery Battalion, were mortally wounded; command of the column passed to Maj. Harry R. Van Arnam. In the early morning hours of 12 November the 11th Panzer detachment evacuated Fonteny, saving most of its guns and infantry but abandoning three Panther tanks.

The 3rd Battalion of the 137th Infantry came up to relieve the 1st Battalion in Fonteny, the 2nd Battalion of the regiment seized Faxe—thus reopening contact between the north and south columns of CCB—and the armor and infantry struck east to secure the entrance into the valley of the Nied Française, through which passed the route to Morhange. Before the day ended the American tanks reached the village of Oron, there seizing a bridge across the Nied Française. The retreating Germans had offered little coordinated or effective resistance, and over six hundred surrendered to CCB and the 137th Infantry.36

The German withdrawal on 12 November placed the 35th Division and CCB in position for a final drive against the outpost villages guarding the western approaches to Morhange. In the center the 320th Infantry finally cleared the Forêt de Château-Salins. The regiment was placed in reserve and the shivering, weary men given fresh clothing—the first dry apparel for most of them since the fight for the forest began. On the east flank the 134th Infantry advanced almost without opposition. General Baade finally ordered the regiment to a halt at Bellange, about three and a half miles southwest of Morhange, so that warm clothing and dry socks could be issued to the attacking troops. The week-long rain had come to an end, but this brought no relief to the soldier, for bitter cold followed. The XII Corps commander ordered

Prisoners being marched to the rear, after surrendering to Combat Command B on 12 November

that overshoes be returned to the troops—they had been discarded at the beginning of the offensive37—and extra blankets and heavy clothing were issued as quickly as they could be brought into the front lines. Winter warfare was about to begin.

The Drive toward Morhange

Any military map of Lorraine will show the importance of Morhange as a road center. In 1914 the control of Morhange gave the German armies a sally port from which to debouch into the Seille Basin. In November 1944 the forces driving northeastward out of the Seille Basin were forced to funnel, at least in part, through Morhange. But a map will reflect the difficulty of reaching Morhange in force except by an attack along the chain of ridges leading in from the west.

The drive toward Morhange began on 13 November. On the left CCB moved east along the valley of the Nied Française with the 137th Infantry close behind. Van Arnam’s column, south of the river, though advancing slowly in the face of successive mine fields and blown bridges, at dark was astride a ridge north of Achain and less than three miles from Morhange. Churchill’s column, which had crossed to the north bank of the Nied Française at Oron, advanced by road as far as Villers-sur-Nied. At this point the enemy had mined the highway so thoroughly that Churchill decided to take his command cross country. In the course of this maneuvering Company A of the 8th Tank Battalion worked its way to the rear of some German batteries covering the Villers-sur-Nied–Marthille road. The light tanks of the battalion pointed the target with tracer bullets; then the company of mediums rolled over the gun positions with its own pieces blazing. Taken completely by surprise the German crews were unable to bring their guns to bear, and in one blow the American tankers destroyed seven 88-mm. and eleven 75-mm. field pieces. Churchill’s column laagered on a ridge north of Marthille not far from Van Arnam’s column during the night of 13–14 November, and the engineers undertook the difficult and dangerous task of clearing the mines from the road to the rear.

The next day CCB and a battalion of the 137th attacked the villages of Destry and Baronville, preparatory to flanking Morhange from the north in conjunction with a drive from the south and west by the bulk of the 35th Infantry Division. The attack was successful, although the enemy fought back doggedly until well into the night. Fresh German replacements, just arrived from Poland, here had entered the 559th VG Division line with orders to hold until the last man. The journals of the American troops who opposed them at Destry and Baronville all speak of “extremely bitter resistance” ending only with the death or capture of the German grenadiers.

However, the plans for CCB to close on Morhange from the north and continue the drive to Sarreguemines were doomed by the weather, rather than enemy resistance. The rains resumed, the armor was road-bound, and the left flank of CCB was left hanging in the air along the Metz–Sarrebourg railroad. While engaged in futile attempts to maneuver off the roads CCB received orders from XII Corps headquarters on 15 November to hold up the attack. Two days later CCB moved south to join the rest of the 4th Armored Division in a drive through the Dieuze gap, thus ending seven days of what the combat command would later recall as a “heart break action.”38

The pressure applied in the Morhange sector by the American armor had helped to render the new German defensive line untenable and may have weakened the enemy will to resist. But the final phase of the operation, that is, the frontal attack by the 35th Division in the direction of Morhange, cost the American infantry heavily. After a night of snow and bitter cold the 134th Infantry moved out on the morning of 13 November to clear the natural causeway along which the Château-Salins–Baronville road led into Morhange. The 3rd Battalion, on the left, was ordered to take the section of the ridge line known as the Rougemont (later known to the Americans as “Bloody Hill”) and then drive astride the highway to the northeast. The 3rd Battalion was roughly handled, losing its commander, Lt. Col. Warren C. Wood, when he was wounded and suffering severe losses during the advance across the valley floor and up the slopes of Bloody Hill, an advance in which each rifleman was outlined as a perfect target against the fresh white snow. Nonetheless the

battalion took the objective and wheeled toward Morhange, bypassing Achain where the 2nd Battalion was heavily engaged.