Chapter 10: The Peel Marshes

Culmination of the fight for Antwerp meant that with one exception the front of the 21 Army Group was economical and secure. Yet the exception was not minor. Until it could be taken care of, the British could not launch their long-delayed Ruhr offensive.

The problem lay in that region west of the Maas River between the MARKET-GARDEN salient and the 21 Army Group boundary with the XIX U.S. Corps eleven miles north of Maastricht. Situated between the British and Americans, this region had become a joint problem as early as mid-September when the Americans had driven northeastward via Aachen and the British had turned northward toward Eindhoven, two divergent thrusts creating a great gap which would remain a threat to the open flanks of both forces until somebody got around to closing it. As events developed, neither Americans nor British were to turn sufficient attention to the gap until the Germans had displayed their penchant for exploiting oversights and weaknesses of their adversaries.

First Army Draws the Assignment

On 22 September—the day when General Hodges authorized postponement of the West Wall assault of the XIX Corps, when Hodges’ entire army went on the defensive, and when hope still existed that Operation MARKET-GARDEN might succeed—the great gap on the left flank of the XIX Corps became not only a threat and an annoyance to the First Army but also First Army’s responsibility. This stemmed from the conference of 22 September at Versailles when General Eisenhower and his top commanders had noted the magnitude of the 21 Army Group’s assignments and decided that the British needed help.1

To strengthen the British and thereby facilitate Field Marshal Montgomery’s proposed new thrust against the Ruhr, the commanders agreed to adjust the boundary between the two army groups northward from the old boundary which ran eleven miles north of Maastricht. General Bradley’s 12th Army Group—more specifically, the First Army and in turn the XIX Corps—was to assume responsibility for the major portion of the region west of the Maas that had been lying fallow in the British zone. At least two British divisions thus would be freed to move to the MARKET-GARDEN salient, the steppingstone for the projected Ruhr offensive. To become effective on 25 September, the new boundary ran northeast from Harselt through the Belgian town of Bree and the Dutch towns of Weert, Deurne, and Venray to the Maas at Maashees (all-inclusive to the 12th Army Group). The detailed location of

the boundary was to be settled by direct negotiation between Montgomery and the First Army commander, General Hodges, while any extension of it beyond Maashees was to “depend upon the situation at a later date.”2

The task of the First Army in the Ruhr offensive became, for the moment, to clear the region west of the Maas while preparing, as far as logistical considerations would permit, for a renewal of the push toward Cologne. To provide forces for the new area of responsibility, General Bradley ordered the Third Army to release the 7th Armored Division to the First Army and also gave General Hodges the 29th Division from the campaign recently concluded at Brest. These two divisions, Montgomery, Bradley, and Hodges agreed at a conference on 24 September, should be sufficient for clearing the region, whereupon one of the two might hold the west bank of the Maas while the other joined the main body of the First Army in the drive on Cologne. Because Montgomery intended that a British corps in a later stage of the Ruhr offensive would drive southeast between the Maas and the Rhine, the commanders foresaw no necessity for extending the new boundary east of the Maas beyond Maashees.3

Despite the expectation that the First Army would not have to go beyond the Maas in the new sector, General Hodges was unhappy with the arrangement. Without a firm guarantee that the new boundary would not be extended, he could visualize a dispersion of his army’s strength east of the river. Furthermore, he had been counting on the 29th Division to protect his own exposed flank, most of which lay east of the Maas; but use of the division for this mission now obviously would be delayed.4

General Hodges apparently took these concerns with him on 26 September when he conferred with Field Marshal Montgomery and the Second British Army commander, General Dempsey, for he emerged from the meeting with an arrangement that satisfied him. Instead of a plan using both the 7th Armored and 29th Divisions, a plan was approved whereby only the armor was to be employed, plus the 113th Cavalry Group and a unit of comparable size provided by the British, the 1st Belgian Brigade.5 As for the boundary, the British had agreed on a line running from Maashees southeast, south, and southwest along the Maas back to the old boundary eleven miles north of Maastricht, thereby giving General Hodges the assurance he wanted against having to conduct operations

east of the river.6 The end result was that the First Army was assigned a giant, thumb-shaped corridor about sixteen miles wide, protruding almost forty miles into the British zone west of the Maas. The entire corridor encompassed more than 500 square miles.

That the basic objective in creation of the corridor, assisting the British in the Ruhr offensive, might have been handled with less complexity by attaching American forces to British command and leaving the boundary in its old position eleven miles north of Maastricht must have been considered. After the war, General Bradley noted three reasons for the unorthodox arrangement, all related to the matter of supply. First, U.S. supply lines led more directly into the region; second, putting U.S. troops under British command would have complicated the supply picture because of differences in calibers and types of weapons; and third, U.S. troops, General Bradley had remarked as far back as the Tunisian campaign, disliked British supplies, particularly British rations.7

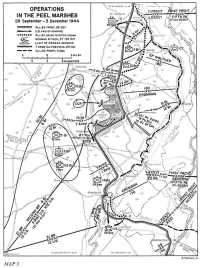

The area which the First Army inherited is featured by the extensive lowlands of De Peel, or the Peel Marshes, a vast fen lying in the upper western part of the region. Covering some sixty square miles between the Maas and Eindhoven, the marshes are traversed only by a limited road net. They represent an obvious military obstacle of great tracts of swampland and countless canals. (Map 3) By 25 September, when the British relinquished control of the sector, the corridor was clear as far north as a canal several miles within the Netherlands, the Nederweert-Wessem Canal which runs diagonally across the corridor between the town of Nederweert at the southwestern edge of the Peel Marshes and a point on the Maas near Wessem, nine miles north of the old army group boundary.

In early planning, when it was expected that two U.S. divisions would be employed in the corridor, the XIX Corps commander, General Corlett, had intended to clear the base of the corridor as far north as the Peel Marshes with the two divisions, then to dispatch a highly mobile force along a narrow neck of comparatively high ground between the marshes and the Maas to link with the British at the north end of the corridor.8 But General Hodges, after conferring with the British commanders on 26 September, had radically altered the plan. Hodges directed that the 7th Armored Division pass around through the British zone and make the main attack southward along the narrow neck of land between the marshes and the Maas. Coincidentally, the 1st Belgian Brigade and the 113th Cavalry Group were to launch a secondary thrust from the south. The 29th Division thus would be available immediately to hold the north flank of the XIX Corps east of the Maas, thereby freeing the entire 2nd Armored and 30th Divisions to break through the West Wall north of Aachen and participate in the drive on Cologne.9

So optimistic was General Hodges that a combination of the XIX Corps West Wall offensive and a renewal of the attack

Map 3: Operations in the Peel Marshes 29 September-3 December 1944

by the VII Corps would produce a breakthrough toward the Rhine that he seriously considered the possibility that the 7th Armored Division’s operation west of the Maas might prove unnecessary. Not to be caught unawares should this develop, he directed that the 7th Armored Division be prepared to jump the Maas and drive eastward or southeastward to complement any breakthrough achieved by the bulk of the XIX Corps.10

Bowing to his superior’s direction, General Corlett issued final orders for the Peel Marshes offensive on 28 September. The 7th Armored Division was to pass through the British zone to positions north of the Peel Marshes and attack southeast and south through Overloon and Venray to clear the west bank of the Maas. Because the British had not occupied all their zone within the new boundary, the first five miles of the 7th Armored Division’s route of attack lay within the British zone. The 1st Belgian Brigade was to attack northeast across the Nederweert–Wessem Canal early on 29 September, eventually to link with the 7th Armored Division. The Belgians were to deny crossings of the Maas in the vicinity of Roermond, six miles northeast of Wessem, and were to regulate their advance with that of the 113th Cavalry Group attacking north toward Roermond from the vicinity of Sittard along the east bank of the Maas. This move by the cavalry would tend to soften the angle of a gap which still would remain on the left flank of the XIX Corps east of the Maas even after completion of the Peel Marshes offensive.11

To the detriment of the Peel Marshes operation, the plan to clear the thumb-shaped corridor from the north instead of from the south and with but one instead of two available divisions reflected an erroneous impression of the dispositions and strength of German forces in the corridor. Usually prescient in these matters, the XIX Corps G-2, Col. Washington Platt, had erred notably in this instance in his estimate of the enemy. Perhaps the error resulted from the fact that the XIX Corps had so recently taken over the corridor; perhaps the fact that the British who had heretofore borne responsibility for the corridor had had little enemy contact upon which to base accurate intelligence information. In any event, Colonel Platt estimated that within the corridor the Germans had only about 2,000 to 3,000 troops.12

In reality, the Germans occupying the thumb-shaped corridor were at least seven to eight times stronger than Colonel Platt estimated. Just as in the other sectors of the First Parachute Army, the enemy here had increased greatly in strength and ability since General Student first had assumed command of the army three weeks before. Within the corridor itself, General Student had the bulk of an entire corps, General von Obstfelder’s LXXXVI Corps.

On 18 September the LXXXVI Corps had assumed command of Colonel

Landau’s 176th Division and Parachute Training Division Erdmann, the latter the division which General Student early in September had formed around a nucleus of three parachute regiments. After an initial commitment against the MARKET-GARDEN salient at Veghel, Obstfelder had gone on the defensive against the 8 British Corps, which had driven northward along the right flank of the MARKET-GARDEN corridor. As September drew to a close, the LXXXVI Corps still was defending along the east wing of the First Parachute Army. The 176th Division was east of the Maas near Sittard but would be drawn into the battle of the corridor because of the 113th Cavalry Group’s northward attack toward Roermond. Although the 176th Division had been buffeted unmercifully in the 2nd U.S. Armored Division’s mid-September drive toward the German border, General von Obstfelder was able during the latter third of September to replenish the division with heterogeneous attachments. By the end of the month Colonel Landau was capable of a presentable defense against an attack in no greater strength than a cavalry group could muster.

Sharing a boundary with the 176th Division near the Maas, the Parachute Training Division Erdmann held the widest division sector within the LXXXVI Corps, a front some twenty-two miles long extending along the Nederweert-Wessem Canal northwestward to include about half the Peel Marshes. Had the Americans followed their original plan of attacking northeastward across the Nederweert-Wessem Canal with two divisions, they would have encountered in Division Erdmann a unit of creditable strength and fighting ability but also a unit hardly capable in view of this elongated front of holding the attack of two U.S. divisions.13

Had these been the only two German forces available, the choice of attacking along the narrow neck of land between the Peel Marshes and the Maas might have been a happy one. As it was, General von Obstfelder received two additional units only a few days before the Americans were to jump off. The first was an upgraded training division of doubtful ability, the 180th Replacement Training Division. This division assumed responsibility for the northern half of the easily defensible Peel Marshes north of and adjacent to Division Erdmann. The second unit was Kampfgruppe Walther, the combat team of varying composition which first had opposed the British in the bridgehead over the Meuse–Escaut Canal and subsequently had cut the MARKET-GARDEN corridor north of Veghel. Having failed to maintain severance of the corridor, Kampfgruppe Walther had been pulled back into the LXXXVI Corps sector and reinforced with a strong complement of infantry from the 180th Division. The major component still was the 107th Panzer Brigade, which even after fighting against the MARKET-GARDEN salient had approximately seven Mark IV tanks and twenty Mark V’s. Though Kampfgruppe Walther probably was no stronger than a reinforced U.S. regiment, it was a force to be reckoned with in constricted terrain.14

Although the mission of the LXXXVI Corps was purely defensive, General von Obstfelder had specific orders to halt the Allies as far to the west as possible. That the point of decision in this defense might come at the exact spot the Americans had chosen for the main effort of their corridor campaign was indicated five days before the event by the Army Group B commander. “It is particularly important,” Field Marshal Model said, “to hold the areas around Oploo and Deurne. ...”15 Deurne was but a few miles southwest of the spot chosen for the 7th Armored Division’s attack. Oploo was to be the point of departure for the attack.

But these things the Americans did not know. Still under the impression that only about 3,000 Germans held the entire thumb-shaped corridor, the 7th Armored Division moved early on 29 September to pass through the British zone and reach jump-off positions near Oploo. At the same time, both the 1st Belgian Brigade and the 113th Cavalry Group began to attack along the south of the corridor toward Roermond.

Before crossing the Nederweert-Wessem Canal, the 1st Belgian Brigade had to reduce a triangular “bridgehead” which Division Erdmann had clung to about the town of Wessem near the juncture of the canal with the Maas. But even this the lightly manned, lightly armed Belgians could not accomplish. Although strengthened by attachment of a U.S. tank destroyer group, the Belgians could make little headway across flat terrain toward the canal. By 2 October revised estimates of enemy strength in Wessem and beyond the canal were so discouraging that the attack was called off.16

The 113th Cavalry Group’s coincident attack developed in a series of piecemeal commitments, primarily because one squadron was late in arriving after performing screening duties along the XIX Corps south flank. By 4 October, two days after operations of the adjacent Belgian brigade had bogged down, a special task force had cleared a strip of land lying between the Maas and the Juliana Canal to a point a few miles beyond the inter-army group boundary; an attached tank battalion (the 744th) had built up along a line running northwest from Sittard to the point on the Juliana reached by the special task force; and other contingents of the cavalry and the armor clung precariously to a scanty bridgehead across the Saeffeler Creek a few miles northeast of Sittard. Assisted by numerous small streams and drainage ditches, the enemy’s 176th Division had offered stout resistance all along the line, particularly in the bridgehead beyond the Saeffeler. The cavalry lost heavily in men and vehicles. Because the group had “exhausted the possibilities of successful offensive action” with the forces available, the commander, Colonel Biddle, asked to call off the attack. With its cessation, all hope that the main effort by the 7th Armored Division in the north might benefit from operations in the south came to an end.17

In the meantime, on 30 September, the 7th Armored Division under Maj. Gen.

Lindsay McD. Silvester had reached jump-off positions southeast of Oploo and was prepared to launch the main drive aimed at clearing the west bank of the Maas.18 Having rushed north straight out of the battle line along the Moselle River near Metz, General Silvester had found little time in which to reorganize his troops and replace combat losses. Casualties in the Metz fighting, the division’s first all-out engagement, had been heavy; and in seeking to get the best from his units, General Silvester had replaced a number of staff officers and subordinate commanders. Including officers killed or wounded as well as those summarily relieved, CCB now had its fourth commander in a month; CCR, its eighth.

Immediate objectives of the 7th Armored Division were the towns of Vortum, close along the Maas, and Overloon, near the northeastern edge of the Peel Marshes. Hoping to break the main crust of resistance at these points, General Silvester intended then to sweep quickly south and bypass expected centers of resistance like Venray and Venlo. At these two points and at Roermond, which was to be taken by the Belgians and 113th Cavalry, the Germans had concentrated the meager forces they had been able to muster for defense of the corridor. Or so General Silvester had been informed by those who predicted that the enemy had but two to three thousand troops in the corridor.

Attacking in midafternoon of 30 September, the 7th Armored Division encountered terrain that was low, flat, open, sometimes swampy, and dotted with patches of scrub pines and oaks. Moving on Vortum, a town blocking access to a highway paralleling the Maas on the division’s left wing, a task force of CCB (Brig. Gen. Robert W. Hasbrouck) ran almost immediately into a strong German line replete with antitank guns, mines, panzerfausts, and infantry firmly entrenched. Because drainage ditches and marshy ground confined the tanks to the roads and because the roads were thickly mined, the onus of the attack fell upon the dismounted armored infantry. Fortunately, the infantry could call upon an ally, the artillery. Although the 7th Armored Division had only one 4.5-inch gun battalion attached to reinforce the fires of its organic artillery, General Silvester could gain additional support from organic guns of a British armored division that was in the line farther north. Thus on 2 October seven British and American artillery battalions coordinated their fires to deliver 1,500 rounds in a sharp two-minute preparation that enabled the task force of CCB at last to push into Vortum. In the town itself, resistance was spotty; but as soon as the armor started southeast along the highway paralleling the Maas, once again the Germans stiffened.

In the meantime, General Silvester was making his main effort against the road center of Overloon, southwest of Vortum. Col. Dwight A. Rosebaum’s CCA attacked the village along secondary roads from the north. After pushing back German outposts, the armor early on 1 October struck the main defenses. Here the main infantry components of Kampfgruppe Walther were bolstered by remnants of a parachute regiment which had

Using a Drainage Ditch for Cover, an infantryman carries a message forward in the Peel Marshes area

fought with the Kampfgruppe against the MARKET-GARDEN salient.19 Employing the tanks of the 107th Panzer Brigade primarily in antitank roles from concealed positions, the Kampfgruppe was able to cover its defensive mine fields with accurate fire that accounted for fourteen American tanks.20 The American infantry nevertheless gained several hundred yards to approach the outskirts of Overloon; here small arms and mortar fire supplemented by artillery and Nebelwerfer fire forced a halt.

Resuming the attack at daybreak on the third day (2 October) behind a preparation fired by seven battalions of artillery, the forces of the 7th Armored Division attempting to invest Overloon still could not advance. Although the first air support of the operation hit the objective in early afternoon and reportedly resulted in destruction of a German tank, this failed to lessen German obstinacy materially. An hour before dark, the enemy launched a counterattack, the first in a seemingly interminable series that must have left the American soldier in his foxhole or tank wondering just which side held the initiative. Fortunately none of

the counterattacks was in strength greater than two companies so that with the aid of supporting artillery and fighter-bombers, the men of CCA and CCB beat them off—but not without appreciable losses, particularly in tanks.

Late on 3 October General Silvester relieved CCA with CCR (Col. John L. Ryan, Jr.) The counterattacks continued. In the intervals, the Americans measured their advance in yards. Even though the combined efforts of CCA and CCR eventually forged an arc about Overloon on three sides, the Germans did not yield.

By 5 October the 7th Armored Division had been stopped undeniably. For a total advance of less than two miles from the line of departure, the division had paid with the loss of 29 medium tanks, 6 light tanks, 43 other vehicles, and an estimated 452 men. These were not astronomical losses for an armored division in a six-day engagement, particularly in view of the kind of terrain over which the armor fought, yet they were, in light of the minor advances registered, a cause for concern. The 7th Armored Division in gaining little more than two miles failed even to get out of the British zone into the corridor it was supposed to clear.

As early as the afternoon of 2 October, the date of the first of the German counterattacks that eventually were to force acceptance of the distasteful fact that the 7th Armored Division alone could not clear the thumb-shaped corridor, General Corlett had irretrievably committed the main forces of the XIX Corps in an assault against the West Wall north of Aachen. Thus no reinforcements for the secondary effort in the north were available. On 6 October General Hodges told General Corlett to call off the 7th Armored Division’s attack.21

The 7th Armored Division could point to no real achievement in terms of clearing of the corridor. Had the division’s mission been instead to create consternation in German intelligence circles, General Silvester certainly could have claimed at least an assist. Indeed, had this been the purpose of the Allied commanders at Versailles in adopting a boundary creating such a cumbersome corridor, someone could have taken credit for a coup de maître. For the German G-2’s just could not conceive of such an unorthodox arrangement.

The order of battle of the Second British and First US. Armies [the Army Group B G-2 wrote on 2 October] at present is obscure in one significant point: We have not yet definitely determined whether the presence of 7th U.S. Armored Division opposite the right wing of LXXXVI Corps indicates a shift of the British-American army group boundary to the area eight to ten miles south of Nijmegen. If this should be so ... we would then have to expect that the enemy will stick to his original plan to launch the decisive thrust into the industrial area (the Ruhr) from the area north of the Waal and Neder-Rijn [i.e., a projection of the MARKET-GARDEN salient]; a new, major airborne landing must be expected in conjunction with such an operation.

In any event the enemy will continue his attacks to widen the present penetration area [the MARKET-GARDEN salient] in both directions. ...

The assumption that the front of the American army group has been lengthened by 40–50 miles is a contradiction of intelligence reports concerning strong concentrations of forces at Aachen; it appears questionable whether the enemy forces [in the vicinity of Aachen] are strong enough that, in addition to this main effort concentration,

they can also take over a sector heretofore occupied by the British. ...

We must also consider the possibility that the intelligence reports concerning the intended offensive via Aachen toward Cologne were intentionally planted by the enemy, and that in contradiction to them, the Americans will shift their main effort to push northeastward from the Sittard sector, and to roll up the Maas defense from the south. ...22

On the date the Army Group B intelligence officer wrote this remarkable treatise, he was wrong in almost every respect. The inter-army group boundary had seen no genuine shift northward; on this very day of 2 October, U.S. forces in the Aachen sector had begun a drive designed to put the XIX Corps through the West Wall, a preliminary to resuming a major thrust from Aachen toward Cologne; and the British commander, Field Marshal Montgomery, had abandoned his intention of extending the MARKET-GARDEN salient northward in favor of a drive from Nijmegen southeastward against the western face of the Ruhr.

A few days later Montgomery had to go a step further and forego all plans for an immediate drive on the Ruhr. Indications of enemy strength near Arnhem, British responsibilities in the opening of Antwerp, and the 7th Armored Division’s experience with an unyielding enemy at Overloon—together these factors proved too overwhelming.23 Except for operations to open Antwerp, about all Montgomery could do for the moment was to attempt to set the stage for a later drive on the Ruhr by eliminating once and for all this problem of German holdout west of the Maas.

In a conference on 8 October, the British commander and General Bradley agreed to readjust the army group boundary to its former position, thus returning the region of the Peel Marshes to the British. But the Americans still were to have a hand in clearing the sector. To General Dempsey’s Second British Army General Bradley transferred the 7th Armored Division and the 1st Belgian Brigade, including American attachments. The complex situation whereby American units under American command had assumed responsibility for clearing a corridor running deep into the British zone was dissipated. Unfortunately, the problem of the Germans in this holdout position west of the Maas could be neither so readily nor so happily resolved.

The British Attempt

Upon transfer, General Silvester’s 7th Armored Division came under the 8 British Corps, commanded by Lt. Gen. Sir Richard N. O’Connor. Relieving the armor in the Overloon sector with British units, General O’Connor directed General Silvester to take over an elongated, zigzag defensive sector within, west, and south of the Peel Marshes. The line ran from the vicinity of Deurne southeast along the Deurne Canal to Meijel, a town well within the confines of the Peel Marshes, then southwest along the Noorder Canal to Nederweert and southeast along the Nederweert–Wessem Canal to the Maas near Wessem. Though this front was some thirty miles long, defense would be facilitated by obstacles like the three canals and the limited routes of communication through the marshes. In addition, General Silvester had the 1st Belgian Brigade as an attachment to hold approximately

nine miles of the line along the Nederweert–Wessem Canal and the Maas River.

Seeing advance to the Maas as a prerequisite to renewing a British thrust on the Ruhr, Field Marshal Montgomery directed an early offensive by O’Connor’s 8 Corps. Using an infantry division (the 3rd), General O’Connor was to seize the elusive objective of Overloon and push on to Venray, the largest town the Germans held in this sector and the most important road center. Coincidentally, the 7th US. Armored Division was to feign an attack eastward through the Peel Marshes from the vicinity of Deurne. Upon seizing Venray, General O’Connor hoped to shake loose a British armored division (the 11th) to strike along the narrow neck between the marshes and the Maas southeastward to Venlo while as yet unidentified forces attacked northeastward to clear the southern part of the corridor from the vicinity of Nederweert. This offensive by the 8 Corps, Field Marshal Montgomery directed during the first week of October at a time before he had given unequivocal priority to the fight to open Antwerp.24

On 12 October infantry of General O’Connor’s 8 Corps attacked Overloon and just before dark succeeded in entering the village. Renewing the attack the next day to cover three remaining miles to Venray, the British encountered dogged opposition like that the Americans had faced earlier: extensive mine fields, marshes, woods, antitank guns, Nebelwerfer and artillery fire, and tanks cleverly employed in antitank roles. Not until five days later on 17 October did the British finally occupy Venray.

Any plans General O’Connor might have had for exploiting the capture of Venray had been negated even before his troops took the town. For on 16 October, a day before occupation of Venray, Field Marshal Montgomery had issued his directive shutting down all offensive operations in the Second Army other than those designed to assist the opening of Antwerp. Completion of the task of clearing the west bank of the Maas had to await termination of the battle of the Schelde.

A Spoiling Attack

For ten days following postponement of British plans to clear the corridor west of the Maas, activity throughout the sector was confined to patrol and artillery warfare, except for a small incursion by the 7th Armored Division’s CCB during 19–22 October across the Deurne Canal along a railway running east from Deurne. Not until Field Marshal Montgomery could complete the onerous tasks on his left wing could he again turn attention to this annoying holdout position. In the meantime, the First U.S. Army became heavily engaged in reorganization around Aachen in preparation for a new attempt to reach the Rhine.

Where the Allies had to be content to file this region for future consideration, the Germans did not. Behind the facade of patrol clashes and artillery duels, German commanders hit upon a plan designed to exploit their holdout position to the fullest. In casting about for a way to assist the Fifteenth Army, which was

incurring Allied wrath along the Schelde and in southwestern Holland, the Army Group B commander, Field Marshal Model, suggested a powerful, raid-like armored attack from the Peel Marshes into the east flank of the MARKET-GARDEN salient. If strong enough, this kind of attack might force the British to call off their efforts in the southwestern part of the Netherlands.25

The forces required for this maneuver happened to be available. A week before Model broached his idea to the Commander in Chief West, Rundstedt, headquarters of the XLVII Panzer Corps under General von Lüttwitz (former 2nd Panzer Division commander) had been disengaged from the front of Army Group G, whose forces sat astride the boundary between the 12th and 6th U.S. Army Groups. The corps had moved north to a position behind the left wing of the First Parachute Army, there to conduct training and rehabilitation of the 9th Panzer and 15th Panzer Grenadier Divisions and to constitute a reserve for Army Group B.26

By the latter part of October, strength of the two divisions under the XLVII Panzer Corps was not inconsiderable. Numbering about 11,000 men, the 9th Panzer Division had at least 22 Panther tanks, 30 105-mm. and 150-mm. howitzers, and some 178 armored vehicles of various types, probably including self-propelled artillery. The 15th Panzer Grenadier Division numbered close to 13,000 men and had at least 1 Mark II and 6 Mark IV tanks.27

Endorsing the Army Group B commander’s plan, Rundstedt ordered that the XLVII Panzer Corps attack on 27 October with the 9th Panzer Division and attachments from the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, whereupon the rest of the panzer grenadiers were to exploit early gains of the armor. The attack was to strike sparsely manned positions of the 7th U.S. Armored Division along the Deurne Canal and the Noorder Canal deep within the Peel Marshes west of Venlo. The center of the thrust was to be the town of Meijel, near the junction of the two canals. Only a limited objective was assigned: to carve a quadrilateral bulge into Allied lines six miles deep, encompassing about forty-five square miles. The deepest point of penetration was to be at Asten, northwest of Meijel alongside the Bois le Duc Canal.28

At 0615 on 27 October, after a week of bad weather that had reduced visibility almost to zero, the dormant sector within the Peel Marshes erupted in a forty-minute artillery preparation. The attack that followed came as a “complete surprise.” As intelligence officers later were to note, the only prior evidence of German intentions had come the day before when

observers had detected about 200 infantry marching westward at a distance of several miles from the front and the night before when outposts had reported the noise of vehicles and a few tanks moving about.29 Although no relationship between this attack and the enemy’s December counteroffensive in the Ardennes could be claimed, the former when subjected to hindsight looked in many respects like a small-scale dress rehearsal for the Ardennes.

The commander of the 9th Panzer Division, Generalmajor Harald Freiherr von Elverfeldt, made his first stab a two-pronged thrust at Meijel, held only by a troop of the 87th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron. Forced from their positions, the cavalrymen rallied and with the help of another troop of cavalry counterattacked. But to no avail.

A few miles to the north along the Meijel-Deurne highway at Heitrak another armored thrust across the Deurne Canal broke the position of another troop of cavalrymen. Reacting quickly the 7th Armored Division commander, General Silvester, got reinforcements of CCR onto the Meijel-Deurne highway to deny further advance for the moment in the direction of Deurne; but another highway leading northwest from Meijel out of the marshes to Asten still was open. Farther southwest, near Nederweert, another German push forced a slight withdrawal by another cavalry unit; but here commitment of tank, infantry, and tank destroyer reinforcements from CCA stabilized the situation by nightfall of the first day.

Seeking to bolster the 7th Armored Division by shortening the division’s elongated front, the British corps commander, General O’Connor, sent contingents of a British armored division to relieve CCB in the bridgehead the Americans had won earlier beyond the Deurne Canal along a railroad that traverses the marshes. This relief accomplished not long after nightfall on 27 October, General Silvester had a reserve for countering the German threat. He promptly ordered the CCB commander, General Hasbrouck, to counterattack the next morning.

Early on 28 October, General Silvester aimed two counterattacks at Meijel along the two highways leading to the town. A task force of CCR under Lt. Col. Richard D. Chappuis drove southeast along the Asten-Meijel road, while General Hasbrouck’s CCB pushed southeast along the Deurne-Meijel highway. One column of CCB branched off to the east along a secondary road in an effort to recapture a bridge the Germans had used in their thrust across the Deurne Canal to Heitrak.

During the night, the Americans soon discovered, the 9th Panzer Division’s Reconnaissance Battalion had pushed several miles northwest from Meijel up the road toward Asten, and along the Deurne highway the Germans had consolidated their forces about Heitrak. At Heitrak, the XLVII Panzer Corps commander, Luettwitz, had thrown in the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division while shifting the entire 9th Panzer Division to the center and south of the zone of penetration near Nederweert and toward Asten.30 In the face of these developments and marshy terrain that denied maneuver off the roads,

none of the 7th Armored Division’s counterthrusts made much headway.

Early on the third day, 29 October, the Germans renewed the attack. A strong thrust drove Colonel Chappuis’ task force back almost half the distance to Asten before concentrated artillery fire forced the enemy to halt. Two other thrusts, one aimed northwest from Heitrak toward Deurne, the second along the secondary road from the east, forced both columns of General Hasbrouck’s CCB to fall back about half the distance from Meijel to Deurne. Trying desperately to make a stand at the village of Liesel, the combat command eventually had to abandon that position as well. The loss of Liesel was particularly disturbing, for it opened two more roads to serve the Germans. One of these led west to Asten. If the Germans launched a quick thrust on Asten, they might cut off Colonel Chappuis’ task force of CCR southeast of that village.

From the German viewpoint, capture of Liesel had another connotation. This village was the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division’s farthest assigned objective along the Meijel-Deurne highway; its capture emphasized the rapid success the spoiling attack had attained. Perhaps equaling or surpassing Allied surprise upon the opening of the enemy’s drive was German surprise at the speed and extent of their own gains. So impressed was Field Marshal Model that he saw visions of turning what had been conceived as a large-scale raid into something bigger. As early as 28 October, the second day of the attack, Model had asked Rundstedt at OB WEST to reinforce the XLVII Panzer Corps immediately with the 116th Panzer Division and the 388th Volks Artillery Corps.31 The latter was no minor force: it controlled six artillery battalions totaling 87 pieces ranging in caliber from 75-mm. guns to 210-mm. howitzers.32

This tract of marshland might have seen major German commitments had it not been for two related factors. First, neither the 116th Panzer Division nor the 388th Volks Artillery Corps was readily at hand. Second, before either could be committed, soberer heads than was Model’s at this time had appraised the situation. On 28 October, they noted, the 7th Armored Division’s counterattacks virtually had tied the Germans to their first day’s gains while “droves” of Allied aircraft attacked delicate German communications lines through the Peel Marshes. On 29 October, for all the success at Liesel and along the Asten road, the Americans had resisted stubbornly. The Germans had lost up to thirty tanks. Furthermore, noted the OB WEST G-2 no indications existed to show that the attack had drawn any Allied strength from the attacks against the Fifteenth Army in the southwestern part of the Netherlands.33

Perceiving that gains thus far were ephemeral, Field Marshal von Rundstedt called a halt. “Continuation of the XLVII Panzer Corps attack no longer promises any results worth the employment of the forces committed,” Rundstedt said. “On the contrary, there is great danger that 9th and 15th Panzer Divisions [ sic] will suffer personnel and matériel losses which cannot be replaced in the near

future. Hence the attack will be called off. ...”34

Had Rundstedt waited a few more hours, he might have spotted an indication that the spoiling attack was accomplishing its purpose, that it was drawing Allied strength away from the Fifteenth Army. A British infantry division (the 15th) which had fought in southwestern Holland began relieving the 7th Armored Division’s CCB at Liesel and CCR southeast of Asten during the night of 29 October. Noting the early identification of two fresh German divisions in the Peel Marshes, Field Marshal Montgomery himself had intervened to transfer this infantry division. Yet removal of the division from the southwestern part of the Netherlands was, in reality, no real loss there, for the division already had completed its role in the campaign south of the Maas.

Upon arrival of this relief, the 8 Corps commander, General O’Connor, directed General Silvester to concentrate his 7th Armored Division to the southwest about Nederweert and Weert. As soon as the situation at Meijel could be stabilized, the American armor was to attack northeast from Nederweert to restore the former line along the northwest bank of the Noorder Canal while British infantry swept the west bank of the Deurne Canal.

Arrival of British infantry to block the highways to Asten and Deurne and introduction of substantial British artillery reserves brought a sharp end to German advances from Meijel. For another day the Germans continued to try, for Field Marshal Model wrung a concession from Rundstedt to permit the attack to continue in order to gain a better defensive line.35 On two days the elusive Luftwaffe even attempted a minor comeback, but with little success. To strengthen the British position further, Field Marshal Montgomery shifted to the sector another British infantry division (the 53rd) that had been pinched out of the battle south of the Maas. Though the German attack in the end had prompted transfer of two British divisions and artillery reinforcement, it had failed to result in any diminution of other operations on the 21 Army Group front. This the Germans failed to recognize when they belatedly—and wrongly—concluded that their attack had accomplished its original purpose.36

All three combat commands of General Silvester’s American division were in the vicinity of Nederweert and Weert by nightfall of 30 October. The front had been stabilized both at Nederweert and near Meijel. The next day General O’Connor narrowed the 7th Armored Division’s sector even more by bringing in a British armored brigade (the 4th) to strengthen the 1st Belgian Brigade along the Nederweert-Wessem Canal and by relieving the Belgians from attachment to the U.S. division. This left the 7th Armored Division responsible only for the Nederweert sector.

While this adjustment was in process, General Bradley on 30 October came to the 7th Armored Division’s headquarters and relieved General Silvester of his command, replacing him with the CCB commander, General Hasbrouck. The relief, General Silvester believed, was based not on the Peel Marshes action but on personality conflicts and a misunderstanding

of the armored division’s performance in earlier engagements in France. General Bradley wrote later that he had made the relief because he had “lost confidence in Silvester as a Division Commander.”37

In the meantime, the Germans also were making adjustments. During the night of 30 October, the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division withdrew to return to its earlier status as Army Group B reserve. The 9th Panzer Division disengaged during the first week of November. Also on 30 October, headquarters of the Fifth Panzer Army (General der Panzertruppen Hasso von Manteuffel) assumed command of the XLVII Panzer Corps, General von Obstfelder’s LXXXVI Corps, and Corps Feldt, the last the provisional corps that had opposed the 82nd U.S. Airborne Division at Nijmegen. Thus the Germans carved a new army sector between the First Parachute and Seventh Armies. Command of the Fifteenth and First Parachute Armies was unified under Army Group Student, a provisional headquarters which subsequently was to be upgraded to a third full-fledged army group.38

On the Allied side, plans for a coordinated drive by the British and Americans to clear the Nederweert–Meijel sector were changed on the first day of November when Field Marshal Montgomery foresaw an end to his campaign in the southwestern part of the Netherlands and decided to introduce his entire 12 Corps on the right flank of the 7th Armored Division along the Nederweert–Wessem Canal. The 12 Corps then was to drive northeast through the thick of the enemy’s holdout position west of the Maas to Venlo, a first step in British co-operation with a new American offensive aimed at reaching the Rhine. The 7th Armored Division now was to attack alone to clear the northwest bank of the Noorder Canal. Not until the armor neared Meijel were the British to launch their part in the attack to take the town.

Though indications were that the 7th Armored Division would meet only about a battalion of Germans on the northwest bank of the Noorder Canal, it was obvious that even an undermanned defender could prove tenacious in this kind of terrain. The attack had to move through a corridor only about two miles wide, bounded on the southeast by the Noorder Canal and on the northwest by De Groote Peel, one of the more impenetrable portions of the Peel Marshes. The armored division’s effective strength in medium tanks at this time was down to 65 percent, but in any case the burden of the fight in this terrain would fall on the armored infantry.

Directing a cautious advance at first, the new division commander, General Hasbrouck, changed to more aggressive tactics when resistance proved light. The principal difficulties came from boggy ground, mines, and German fire on the right flank from the eastern bank of the Noorder Canal. On 6 November, as the armored division neared its final objective just south of Meijel, the British north of that village began their attack southward. But the 7th Armored Division was not to be in on the kill. Late that day General Hasbrouck received orders for relief of his division and return to the 12th Army Group. The Americans had need of the

division in a projected renewal of their offensive toward the Rhine. The relief occurred the next day, 7 November.

With this change, the British delayed the final assault on Meijel to await advance of the 12 Corps northeast from the Nederweert–Wessem Canal. The Germans subsequently abandoned Meijel on 16 November as the 12 Corps threatened their rear. The 8 Corps then drove southward from Venray while the 12 Corps continued northeastward on Venlo. Not until 3 December, more than two months after the first optimistic attempt to clear the enemy from west of the Maas with a lone American division, did these two full corps finally erase the embarrassment of the enemy’s holdout. As the First U.S. Army had been discovering in the meantime in the Hürtgen Forest southeast of Aachen, the Germans were great ones for wringing the utmost advantage from difficult terrain.

Elsewhere along the 21 Army Group front, the Canadians held their economical line along the south bank of the Maas and built up strength about Nijmegen, ready to help in Field Marshal Montgomery’s Ruhr offensive. A British corps (the 30th) prepared to assist a new American offensive by limited operations along the American left flank. This general situation was to prevail on the 21 Army Group front until mid-December.