Part 5: The Hürtgen Forest

The Hürtgen Forest

Blank page

Chapter 16: The Big Picture in October

During the early days of October, at the start of the bitter campaigning near Aachen and Schmidt, it had become obvious that the halcyon days of pursuit had ended. Yet because Allied commanders reckoned the enemy’s resurgence more a product of transitory Allied logistical weakness than of any real German strength, they seem to have assumed that a lucky push at the right spot still might catapult the Allies to the Rhine.1

Not until October passed its mid-point, a fortnight before the start of the second attack on Schmidt, had the full portent of the hard fighting at Aachen, in the Hürtgen Forest, along the Schelde estuary, in the Peel Marshes, and with the Third Army at Metz become apparent. The Germans had effected a remarkable reorganization. This made it imperative that General Eisenhower make a new decision. How best to pursue the war to advantage during the harsh, dreary days of poor campaigning weather that soon must set in?

As the Supreme Commander met with top officers at Brussels on 18 October to plan his decision, he faced the fact that in the period of slightly more than a month—since first patrols had crossed the German border—the most notable advance had been that of MARKET-GARDEN, which had fallen short of expectations. That was the story all along the line. Operations begun in an aura of great expectations usually had ended in bitter dogfights and plodding advances not unlike that in the Norman hedgerows.

In the far north, Field Marshal Montgomery’s 21 Army Group, having failed with MARKET-GARDEN’s bold thrust to turn the north flank of the West Wall and sweep to the Ijsselmeer, at last had given consummate priority to clearing Antwerp’s seaward approaches. This the British commander had done even though it meant postponement of his plans to clear the western face of the Ruhr by driving southeast from Nijmegen and to eliminate the enemy’s bridgehead west of the Maas in the Peel Marshes. Bright prospects of opening Antwerp to Allied shipping had ensued. As the situation developed, the first cargo ship was not to drop anchor in the harbor until 28 November, but no one could have known in mid-October that the campaign along the Schelde would take so long.

On the northern wing of General Bradley’s 12th Army Group next to the British, the First Army had registered

several impressive achievements, including penetrations of the West Wall both north and south of Aachen. The fall of Aachen itself was only a few days off. Yet the sobering fact was that after more than a month of fighting, the First Army in no case had penetrated deeper than twelve miles inside Germany. The enemy had sealed off both West Wall breaches effectively and in the process had dealt the First Army almost 20,000 casualties.2

Though the hard-won gains about Aachen meant a good jump-off point for a renewal of the drive to the Rhine, the development in this sector auguring most for the future was not in the nature of an offensive thrust into the line but of a lateral shift in units behind the line. General Bradley had decided to introduce General Simpson’s Ninth Army between the First Army and the British in the old XIX Corps zone north of Aachen. The 12th Army Group commander had made the decision as early as 9 October, only five days after General Simpson’s army, then containing only one corps of two divisions, had arrived from the conquest of Brest and assumed responsibility for the old V Corps zone in Luxembourg.3

Though Ninth Army’s commitment in Luxembourg thus was to be but a pause in transit, General Bradley had not intended it that way. He had hoped that the Ninth Army’s defense of the lengthy but relatively inactive front in the Ardennes might permit his two more experienced armies—the First and Third—to achieve greater concentration for renewing the drive to the Rhine.4 But before the Ninth Army could be fleshed out with new divisions and accomplish much in this direction, Bradley made his decision to abandon this plan in favor of moving the Ninth Army to the north. General Bradley based his decision in part on a reluctance to put American troops under foreign command, in part on his knowledge of the working methods of the First and Ninth Army staffs. During these early days of October, while the Ninth Army was moving into Luxembourg, Bradley had come to believe that General Eisenhower would not long resist Field Marshal Montgomery’s persistent request for an American army to strengthen the 21 Army Group. Bradley reasoned that unless he acted quickly to juxtapose another army next to the British, the army he would lose would be the First, his most experienced army, his former command for which he held much affection, and an army whose “know-it-all” headquarters staff was difficult to work with unless the higher commander understood fully the staff’s idiosyncrasies. “You couldn’t turn over a staff like that to Montgomery.”5 “Because Simpson’s Army was still our greenest,” General Bradley wrote after the war, “I reasoned that it could be the most easily spared. Thus rather than leave First Army within Monty’s reach, I inserted the Ninth Army between them.”6

To decide five days after moving an army into the center of the line to transfer the same army to the north wing during the height of a transportation shortage might appear at first glance impractical if not actually capricious. Yet a closer examination would reveal that General Bradley never intended to make a physical transfer of more than the army headquarters and a few supporting troops. Beyond circumventing loss of the First Army to the British, the transfer would in effect further Allied concentration north of the Ardennes, which was in keeping with the Supreme Commander’s long-expressed determination to put greatest strength there. In addition, to put the army that was the logical command for absorbing new corps and divisions into the line along the American north flank would serve to shore up what had been a chronic Allied weakness along the boundary between national forces.

To avoid the complicated physical transfer of large bodies of troops and supplies, Bradley ordered that the First Army take command of the Ninth Army’s VIII Corps and its divisions, thereby reassuming responsibility for the Ardennes, while the Ninth Army took over the XIX Corps north of Aachen. By the time written orders for the exchange could be distributed, the VIII Corps had grown from two divisions to four, including the veteran 2nd, 8th, and 83rd Infantry Divisions and the untested 9th Armored Division. These were to pass to the First Army. Artillery was to be exchanged on a caliber-for-caliber basis. Supply stocks were to be either exchanged or adjusted on paper in future requisitions and allocations. The Ninth Army was to open a new command post at Maastricht on 22 October, and at noon on that date the paper transfer of corps and supporting units was to take place.7

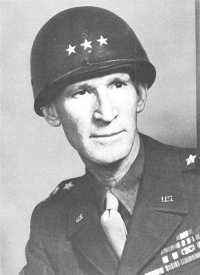

The commander of this youngest Allied army on the Continent was an infantryman with a fatherly devotion to his troops after the manner of Bradley and Hodges. Even without insignia of rank, Bill Simpson looked the part of a general. His rangy, six-foot-four frame would have commanded attention even had he not kept his head clean-shaven. Having had wide combat experience—against the Moros in the Philippines, Pancho Villa in Mexico, and the Germans in the Meuse-Argonne—General Simpson had a healthy respect for the assistance machines and big guns could give his riflemen.

Like their commander, most members of the Ninth Army general staff were infantrymen. The exception was the G-2, Col. Charles P. Bixel, a cavalryman who had transferred his affection to armor. Though the Ninth Army had been organized no earlier than 22 May 1944 and had become operational on the Brittany peninsula only on 5 September, the commander and staff had worked together for a longer period. Both had been drawn primarily from the Fourth Army in the United States, a training command General Simpson had held for seven months. The young Chief of Staff, Brig. Gen. James E. Moore, had even longer association with his commander, having come with General Simpson to the Fourth Army from a previous command. The important G-3 post was held by Col.

General Simpson

Armistead D. Mead, Jr.8 Under Simson’s tutelage, the Ninth Army was to mature quickly and to draw from General Bradley the compliment that “unlike the noisy and bumptious Third and the temperamental First,” the Ninth Army was “uncommonly normal.”9

Even younger than the Ninth Army was the tactical air headquarters which was to work closely with General Simpson’s command. This was the XXIX Tactical Air Command under Brig. Gen. Richard E. Nugent, which was created by taking a rib from the other two tactical commands in the theater. Activated on 14 September, the XXIX TAC, for want of assigned planes, pilots, and headquarters personnel, had operated through September more as a wing than as a separate command. The airmen nevertheless had gotten in a few licks at Brest, gaining a measure of experience for the support to be rendered the Ninth Army through the rest of the European campaign.10

Elsewhere on the American front during September and early October, German resurgence and American logistical limitations had restricted operations as much or more than in the northern sector. Though the logistical crisis had prompted General Eisenhower on 25 September to put the Third Army on the defensive, General Patton had refused to take the blow lying down. Under the guise of improving his positions, Patton had managed to concentrate enough ammunition and supplies to launch limited attacks in the vicinity of Metz. Yet neither General Patton’s legerdemain in matters of supply nor his dexterity in interpreting orders from above had permitted a large-scale offensive. All of October was to pass before the Third Army could hope to push far beyond the Moselle.11

South of the Third Army, General Devers’ 6th Army Group was more independent logistically by virtue of Mediterranean supply lines, yet this force too had ground to a halting pace. After crossing the upper Moselle in late September and

entering the rugged Vosges Mountains, neither General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny’s 1st French Army nor Lt. Gen. Alexander M. Patch’s Seventh U.S. Army could make major gains.12

Air Support

A disturbing aspect of the over-all situation was the marked increase of unfavorable flying weather, which severely limited effectiveness of the tactical air arm. The IX Tactical Air Command, for example, was able to fly only two thirds as many missions in October as in September, and the prospects for November and the winter months were less than encouraging.13 “There’s lots of times,” noted a platoon leader, “when we can’t move an inch and then the P-47s come over and we just walk in almost without a shot.”14 When weather drastically curtailed the number of times the P-47s could come over, this obviously was a serious turn of events.

Weather had a particularly damaging effect as long as the crippled ground transport situation prevented the airmen from moving their bases close to the front lines. At the end of September most of the bases were far back in northern or northwestern France. Not only was time in flight wasted, but often the weather at the bases differed radically from that over the target area, forcing the pilots to return home prematurely. By the time transport became available to move the bases, heavy autumn rains had set in, making bogs of likely airfield sites and requiring increased outlay of time and equipment for airfield construction. By the end of October, most bases of the IX TAC had been moved into Belgium, with the greatest concentration in the vicinity of Charleroi and Liège; but airfields even closer to the front were needed, particularly after the move of the XXIX Tactical Air Command with the Ninth Army to Maastricht.15

The primary missions of the tactical aircraft continued as before: rail-track cutting designed to interfere with movement of German reserves; armed reconnaissance and column cover; and close support of the ground troops against targets like gun positions, troop concentrations, and defended villages. Medium bombers of the IX Bombardment Division concentrated primarily upon interdicting enemy communications by bombing precision targets like road junctions and bridges. Though the airmen protested that pillboxes were an unprofitable target for tactical aircraft, they continued to answer ground requests for support against the West Wall fortifications. In general, the results of the fighter-bomber strikes were less spectacular than during the days of pursuit; but the workmanlike, deliberate effort of the air forces still was rewarding. “We could not possibly have gotten as far as we did, as fast as we did, with as few casualties,” said General Collins of the VII Corps, “without the wonderful air support that we have consistently had.”16

The differing duties and living conditions of air and ground troops sometimes led to misunderstanding, a problem intensified in the wake of short bombing or misdirected strafing.17 For all this, the ground troops gradually developed confidence in their air support and a genuine appreciation of it. Troops who early in the campaign seldom asked for air strikes against targets closer than a thousand yards from the front lines later were naming targets as close as 300 yards. For their part, airmen came to appreciate the effective protection which artillery could provide against enemy flak.18 To help promote mutual understanding, teams of pilots and ground officers were exchanged for several days at a time to share their opposites’ living conditions and combat hazards.

A particular weakness of U.S. tactical air commands was a lack of night fighters. For a long time German troop movements after nightfall were virtually unopposed, and the Luftwaffe was free to operate with impunity. Noting during October that German night interceptor attacks against heavy bombers had decreased markedly, top air officers made available the two P-61 (Black Widow) night fighter squadrons in the theater to the IX and XIX (supporting the Third Army) Tactical Air Commands. Impressed by the accomplishments of the P-61s in this role, air officials lamented only that they had so few of them.19

In an effort to make the best of the unfavorable weather, the air commands turned more and more to special techniques of “blind bombing.” The most widely used was the MEW (Mobile Early Warning) or SCR-584 radar system, whereby forward director posts equipped with radio and radar vectored the planes to the target area over the overcast, talked them into the proper approach, and took them down through the overcast directly over the target. At this point either the pilot himself made final adjustment for the attack or the forward director post specified the moment of bomb release. MEW also was used successfully in night control of aircraft. Despite the weather, the number of fighter-bomber missions, which dropped in October, was to rise again in November and December.20

An Enigma Named Logistics

Two of the reasons for only limited Allied territorial gains in late September and early October were the weather and German resurgence. But the real felon was the crippled logistical structure which still had a long way to go before recovering from the excesses of the pursuit. Although commanders all the way up to General Eisenhower had been willing to defer capture of ports in favor of promised lands farther east, the tactical revelers at last were being forced to penitence. No matter how optimistic the planners or how enthusiastic the executors, the logistical situation never failed to rear its ugly head. October was destined to be the worst month in matters of supply the

Allies were to experience during the campaign on the Continent.21

Though the bulk of American supplies still came in at only two points, Cherbourg and the Normandy beaches, the crux of the problem continued to lie less in shortage of ports than in limitations of transport. How to get supplies from Cherbourg and the beaches to a front that in the case of the First Army at Aachen was more than 500 road miles away? The answer obviously had two facets: improve the transportation system and/or get new ports closer to the fighting lines.

Through all of September and until Field Marshal Montgomery in mid-October gave unequivocal priority to opening Antwerp, hope of new ports was dim. Even capture of Le Havre on 12 September failed to help much, both because damage to the harbor was extensive and because by this time Le Havre was far behind the front. The only hope for the moment lay in improvement in the transport situation. That would be a long uphill struggle.

Railway repairmen, air transport pilots, truck drivers—all soon were performing near miracles. By 10 September sleepy-eyed truckers had completed an original mission of delivering 82,000 tons of supplies to a point southwest of Paris near Chartres and were hauling their loads on an extended Red Ball Express route beyond Paris. By the first of October repairs on the rail net east and northeast of Paris made it possible to transfer truck cargoes near Paris to the railways. Yet not until 16 November was the Red Ball Express to halt operations. By that time, during a life of eighty-one days, the express service would have carried a total of 412,913 tons of supplies.

Many of the trucks borrowed during the pursuit from artillery and antiaircraft units had to be returned as the nature of the fighting again called for all tactical formations at the front. The armies themselves nevertheless continued to augment the trucking resources of the Communications Zone. Because army depots still were far behind the line, much army transportation went toward bridging the gap between the depots and the front. First Army, for example, transported supplies from army dumps at Hirson on the French-Belgian border until early October, when advancement of rail lines brought the dumps to Liège. To obtain winter clothing, the 5th Armored Division sent its organic trucks all the way to the beaches to pick up duffel bags containing long underwear and overcoats. To meet a crisis in 105-mm. ammunition, the First Army on 21 September sent six truck companies back to the beaches.22

Though transport aircraft had made major contributions to supply during the pursuit, they had been withdrawn from this task in order to participate in Operation MARKET-GARDEN. Despite vociferous cries for renewal of an airlift, the SHAEF Air Priorities Board ruled this means of transport too extravagant for large-scale supply movements. Airlift gradually came to be restricted to meeting emergency requirements, as originally intended.

In the last analysis, the railways were the workhorse of the transportation system.

Engineers, railway construction battalions, and French and Belgian laborers worked round the clock to repair lines running deep into the army zones. By mid-September, although the Allies had uncovered almost the entire rail system of France, Belgium, and Luxembourg, rail lines actually in use were few. In little more than a fortnight repairmen opened approximately 2,000 miles of single track and 2,775 miles of double track. Two routes accommodated the First Army, one extending as far northeast as Liège and another as far as Charleroi, there to connect with the other line to Liège.

For all the diligence of the truckers, the airmen, and the railway repairmen, no quick solution of the transport problem was likely. The minimum maintenance requirements for the 12th Army Group and supporting air forces already stood in mid-September at more than 13,000 tons per day and would rise with the commitment of new divisions. In addition, the armies needed between 150,000 and 180,000 tons of supplies for repair or replacement of equipment, replenishment of basic loads, rebuilding of reserves, and provision of winter clothing. Against these requirements, the Communications Zone in mid-September could deliver only about 11,000 tons per day. Some 4,000 tons of this had to be split among the Ninth Air Force and other special demands. Only 40,000 tons of reserves, representing but two days of supply, had been moved any farther forward than St. Lô. Temporarily, at least, U.S. forces could not be supported at desired scales. Tactical operations would have to be tailored to the limited means available. So tight was the supply situation that General Bradley saw no alternative but to continue the unpopular system of tonnage allocations instituted at the height of the pursuit. On 21 September Bradley approved an allocation giving 3,500 tons of supplies to the Third Army, 700 tons to the Ninth Army (which was en route to Luxembourg), and the remainder to the First Army with the understanding that the First Army would receive a minimum of 5,000 tons. This was in keeping with General Eisenhower’s desire to put his main weight in the north. A few days later, upon transfer of the 7th Armored Division from Metz to the Peel Marshes, an adjustment in tonnage gave the First Army 5,400 tons per day to the Third Army’s 3,100. The new allocation took effect on 27 September, at a time when General Hodges had ten divisions to General Patton’s eight.

By careful planning and conservation the two armies conceivably could execute their assigned missions with these allotments on a day-by-day basis. Yet the wildest imagination could not foresee accumulation of reserve stocks on this kind of diet. The fact that the First Army’s operations during the latter days of September and through October developed more in a series of angry little jabs than in one sustained thrust thus had a ready explanation.

Under these circumstances, the armies had to confine their requisitions to absolute essentials, for every request without exception went against the allocation. Even mail ate into assigned tonnage. That friction between the armies and the Communications Zone would arise under these conditions could not have been unexpected. The armies were piqued particularly by a practice of the Communications Zone of substituting some other item, often a nonessential, when temporarily out of a requested item. This

practice finally stopped after the Communications Zone adopted a First Army recommendation that, when it was out of a requisitioned item, tonnage in either rations or ammunition be substituted. Less easily remedied was a failure of the Communications Zone to deliver total amounts allocated. From 13 September to 20 October, for example, the First Army averaged daily receipts of 4,971 tons against an average daily allocation of 5,226.23 Only time and over-all improvement in the logistical structure could remove this source of contention.

The Communications Zone, in turn, complained about an apparent paradox in the supply situation. During the latter days of October, supply chiefs noted that the armies were improving their reserve positions, even though deliveries had increased only slightly, to about 11,000 tons daily. By the end of October, though serious shortages existed in many items, stocks in the combat zone of the 12th Army Group totaled more than 155,000 tons.

That the armies could accumulate reserves at a time when deliveries averaged only 11,000 tons against stated requirements of 25,000–28,000 could be explained partially by the quiescent state of the front; but to the Communications Zone it bore out a suspicion that the armies were overzealous in their requisitioning. The supply and transport services hardly could have let pass without question the dire urgency of army demands which listed as “critically short” items like barber kits and handkerchiefs.

The Communications Zone suspected the First Army in particular of having taken for granted the supply advantage it had enjoyed since before the Normandy landings. The Third Army appeared to accept the supply hardship more graciously, and the Ninth Army, having been born in poverty, usually could be counted on to limit requests to actual needs. Of the three, the First Army was the prima donna, a reputation seemingly borne out by the army’s own admission that the six truck companies which returned to the beaches for critically needed 105-mm. ammunition used some of their cargo space for toilet paper and soap.24 Even General Bradley, whose esteem for the army he formerly commanded was an accepted fact, later termed the First Army “temperamental” and deserving of a reputation for piracy in supply. “First Army contended,” General Bradley wrote, “that chicanery was part of the business of supply just so long as Group [headquarters] did not detect it.”25

Both the Communications Zone and the armies found another supply expedient in local procurement. Though the economy and industrial facilities of the liberated countries were in poor shape, they made important contributions to alleviating the logistical crisis. Local procurement provided the First Army particular assistance in relieving shortages in spare parts for tanks and other vehicles. During October alone, First Army ordnance officers negotiated for a total of fifty-nine different items (cylinder head gaskets, batteries, split rings, and the like).26

A factory in Paris overhauled radial tank engines. Liège manufactured tires and tubes and parts for small arms. The First Army quartermaster entered into

contracts for such varied services as manufacturing BAR belts, assembling typewriters, and roasting coffee.27

No matter what the value of these expedients, the very necessity of turning to them was indicative of the fact that the logistical structure might be frail for a long time. In the first place, the shift from pursuit to close-in fighting had increased rather than decreased supply requirements. Though gasoline demands were lower, ammunition needs were higher. On 2 October, the day when the XIX Corps attacked to penetrate the West Wall north of Aachen, General Bradley instituted strict rationing of artillery ammunition. A few days later Bradley discovered that even at the rationed rate of expenditure the armies by 7 November would have exhausted every round of artillery and 81-mm. mortar ammunition on the Continent. He had no choice but to restrict the armies further. They were to use no more ammunition than that already in army depots, en route to the armies, or on shipping orders. Not until the first of November was artillery ammunition to pass out of the critical stage.28

Maintenance was a major problem. With the pause in the pursuit, commanders could assess the damage done to their vehicles during the lightning-like dashes when maintenance had been a hit-or-miss proposition. As autumn deepened, so did the mud to compound the maintenance problem. Depots often had to be moved to firmer ground. Continental roads, not built for the kind of traffic they now had to bear, rapidly deteriorated. Sharp edges of C Ration tins strewn along the roads damaged tires. This and the deterioration caused by overloading and lack of preventive maintenance quickly exhausted theater tire reserves. Lack of spare parts put many a vehicle in deadline.

Through September the First Army operated with less than 85 percent of authorized strength in medium tanks. To achieve an equitable distribution of those available and to establish a small reserve, the army adopted a provisional Table of Organization and Equipment (T/O&E) reducing authorized strengths in medium tanks. The new T/O&E cut the authorized strengths for old-type armored divisions from 232 to 200, for new-type divisions from 168 to 150, and for separate tank battalions from 54 to 50. The Ninth Army later adopted the same expedient.

The needs of winterization added greatly to the logistical problem. Transporting sleeping bags, blankets, wool underwear, overshoes, and overcoats often had to be accomplished by emergency airlift. In one instance the First Army took advantage of transfer of three DUKW companies from the beaches to obtain wool underwear and blankets. First Army engineers turned to local sawmills for more than 19,000,000 board feet of lumber needed to meet winter housing requirements.29 Not until well into November, after the winds had become chill and the rains were changing to sleet, was the bulk of the winterization program met. The 28th Division, for example, jumped off on 2 November in the cold and mud of the Hürtgen Forest with only ten to fifteen men per infantry company equipped with overshoes. Through

A winter overcoat reaches the front lines

almost all of November antifreeze for vehicles was dangerously limited.

Further compounding the logistical problem was the continuing arrival of new units, both new divisions and smaller separate units. From the time the first patrols crossed into Germany on 11 September until General Eisenhower convened his commanders at Brussels on 18 October, 357,272 more men (exclusive of those arriving via southern France) set foot on the Continent. The cumulative total rose to 2,525,579.30 In terms of divisions, the Allied logistical structure at start of the Siegfried Line Campaign had to support 39 divisions. By 18 October General Eisenhower commanded 30 infantry, 15 armored, and 2 airborne divisions, an increase of 8 for a total of 47.31

Though the 6th Army Group was outside the orbit of the supply services

operating from Normandy, General Eisenhower’s assumption of command over that group had raised total Allied strength under SHAEF to 58 divisions.32 This figure was to stand through the rest of October, though 83,206 more men, either members of small units or replacements, were to arrive. Two more U.S. divisions were scheduled to arrive through Normandy soon after the first of November.33

Tactical commanders naturally chafed to get the new divisions into the line; yet logistical planners on 11 October warned General Bradley that for some six to eight weeks to come their resources would permit support in active combat of no more than 20 divisions, the number already committed. The incoming divisions would have to stick close to the Normandy depots. Though General Bradley did not heed this warning, he had to commit the divisions one by one, so that their arrival failed to produce any immediate marked change in the tactical situation.

Of the new units, 1 infantry division went to the 6th Army Group, another to the Ninth Army, 1 armored and 2 infantry divisions to the Third Army, and 1 armored division to the First Army. The 2 other new units were the airborne divisions which were paying a second visit to the Continent via MARKET-GARDEN. Of 2 additional divisions which had been arriving just as the first patrols crossed into Germany, the 94th Division had come directly under the 12th Army Group for containing bypassed Germans in the lesser Brittany ports, and the 104th Division had helped the Canadians open Antwerp and was soon to go to the First Army. Neither of these was included in the reckoning of 20 divisions supportable in the 12th Army Group. Two other infantry divisions which arrived soon after the first of November were split between the First and Ninth Armies. The net effect of these arrivals on the three armies of the 12th Army Group was to provide 3 additional divisions each for the First and Third Armies and 2 for the Ninth.

The new divisions represented only about one third of the new troops that had set foot on the Continent since early September. The others were in separate units—tank, tank destroyer, antiaircraft, and engineer battalions, line of communications units, and the like—or were replacements. Many were airmen. Most of these men and units had to be transported to the front, and all had to be supplied.

Replacements by this time had high priority, for during September and October casualties had risen by 75,542 to a cumulative total, exclusive of the 6th Army Group, of 300,111. Two thirds of these were U.S. losses.34 Like ammunition at one time in October, replacements were a commodity in short supply on the Continent. On a series of inspection trips down to divisional level during October, General Eisenhower saw at first hand the need for replacements, particularly riflemen. He appealed to the War Department

and also directed a rigid combout of men in the Communications Zone who might be converted into riflemen.35

Not the least of the logistical worries was the shift of the Ninth Army into an active campaigning role north of Aachen. Though General Bradley’s “paper transfer” helped, the Ninth Army still had to amass reserve supplies before opening a major offensive. The logistical pie now had to be cut in three big slices. From the tonnage allocation of 14 October, for example, the Ninth Army drew almost 5,000 tons, an increase over 8 October of 3,200.36

Somewhat paradoxically, even as supply forecasts were gloomiest, the black cloud which had hung depressingly over the logistical horizon actually began to lift. During the last few days of October and the first week of November, forward deliveries fell short of the somewhat modest requirements set; nevertheless, the armies improved their reserve positions. The historian who tells the supply story for this period finds himself in the role of a novelist who leads his reader to believe one thing, then switches dramatically but incredibly to another. But in the autumn of 1944 that was how it was. This was clearly apparent from the fact that by the end of October, when stocks in the combat zone of the 12th Army Group totaled more than 155,000 tons, deliveries still were running far under the armies’ stated requirements. By the end of the first week in November, army reserves were to reach 188,000 tons.

The fact was that a relatively quiescent front and the extraordinary efforts of the supply and transport services at last had begun to show effect. The logistical patient had gained a new lease on life.