Chapter 13: The Rhine Crossings in the South

From the first, General Patton had hoped to exploit his Third Army’s part in the Saar-Palatinate campaign into a crossing of the Rhine. He wanted a quick, spectacular crossing that would produce newspaper headlines in the manner of the First Army’s seizure of the Remagen bridge. He wanted it for a variety of reasons, no doubt including the glory it would bring to American arms, to the Third Army, and possibly to himself, but most of all he wanted it in order to beat Field Marshal Montgomery across the river. Despite General Eisenhower’s earlier indications to the contrary, Patton remained concerned lest the Supreme Commander put the First and Third Armies on the defensive while farming out ten American divisions to the 21 Army Group.1

It was this concern, shared by Generals Bradley and Hodges, that hovered specterlike over the meeting of the three American commanders at Bradley’s headquarters in Luxembourg City on 19 March. Having received Eisenhower’s permission earlier in the day to increase the First Army’s strength in the Remagen bridgehead and an alert to be ready to break out from 23 March onward, General Bradley told Patton to do the very thing the Third Army commander wanted to do—take the Rhine on the run.2 Once the Third Army had jumped the river in the vicinity of Mainz, the First and Third Armies were to converge in the Lahn River valley, then continue close together to the northeast, generally up the Frankfurt–Kassel corridor. The object—in Patton’s mind, at least—was to get such a major force committed in a far-reaching campaign that the 12th Army Group rather than Montgomery’s 21 Army Group “could carry the ball.”3

To avoid a second crossing operation at the Main River, which joins the Rhine at Mainz, the most logical Rhine crossing site for the Third Army was at some point downstream from Mainz. To General Patton and his staff, determined resistance in the outskirts of Mainz seemed to indicate that the Germans appreciated this fact and would be watching for a crossing near the city. Why not, Patton reasoned, accept the handicap of a crossing of the Main in exchange for surprise at the Rhine? Patton told General Eddy of the XII Corps to make a feint near Mainz while actually crossing the Rhine ten miles upstream at Oppenheim.4 (Map X.)

As the troops of the XII Corps drew

up to the Rhine, General Eddy had intended to put the 5th Division in corps reserve. With that in mind, the division commander, General Irwin, called a conference of his unit commanders, but before the meeting could begin early on 21 March, Irwin himself received a summons to appear at corps headquarters. When he returned, his manner and opening remarks alerted his commanders to startling news. Conqueror of twenty-two rivers in France, Belgium, and Germany, the 5th Division was to challenge the mightiest of them all—the Rhine.5

While the 90th Division made a feint behind a smoke screen at Mainz, General Irwin explained, the 5th Division was to launch a surprise night crossing at Oppenheim. Perhaps the most startling news of all was the timing. Although Irwin personally believed Patton would not order the crossing before the 23rd, the division was to be prepared to go within a few hours that same night, 21 March.

The magnitude of the task of bringing assault boats, bridging, and other engineer equipment from depots far in the rear was argument enough for delaying the crossing at least until the 23rd. Yet hardly had General Bradley on the 19th told Patton to cross when convoys started forward with this equipment from stocks carefully maintained in Lorraine since the preceding fall. Although another day would pass before tactical advances in the Saar-Palatinate opened direct routes for the convoys, the Third Army commander would listen to no voices cautioning delay. Each day, even each hour, gave the Germans additional time to recover from the debacle in the Saar-Palatinate and prepare a Rhine defense. Furthermore, Field Marshal Montgomery’s Rhine crossing was scheduled to begin during the night of 23 March. If Patton was to beat Montgomery across, he had to move by the night of the 22nd.

When General Eddy in midmorning of 22 March told General Irwin that Patton insisted on a crossing that night, Irwin protested that it would be impossible to make a “well-planned and ordered crossing” by that time. On the other hand, Irwin added, he would be able “to get some sort of bridgehead.”6 Some sort of bridgehead was all General Patton was after.

During late morning of the 22nd the commander of the 5th Division’s 11th Infantry, Col. Paul J. Black, was at his 3rd Battalion’s command post in the town of Nierstein, a mile downstream from Oppenheim, when word came from General Irwin. The 11th Infantry was to cross the Rhine that night at 2200.

Allotted about 500 boats manned by the 204th Engineer Battalion, the 11th Infantry was to employ two battalions in the assault wave, the 3rd crossing at Nierstein, the 1st at Oppenheim. Although an impressive artillery groupment of thirteen battalions stood ready to fire on call, they were to eschew preparatory concentrations in quest of surprise. Observation for the artillery was excellent: hills on the west bank of the Rhine overlook an expanse of generally flat ground stretching more than ten miles beyond the river. The ground is crisscrossed by small canals and drainage

ditches. The width of the Rhine at this point ranges from 800 to 1,200 feet.

Once the 11th Infantry and its sister regiments had secured a bridgehead, the 4th Armored Division was to exploit to the northeast, bypassing Frankfurt-am-Main and gaining a bridgehead over the Main River east of Frankfurt at Hanau. From that point the XII Corps was to drive northward toward a juncture with the First Army in the Lahn River valley. The 6th Armored, 89th, and 90th Divisions also were available.7

Despite the haste involved in the timing of the assault, a force of 7,500 engineers made elaborate preparations for supporting the infantry and bridging the Rhine. Early assault waves were to transport bulldozers and air compressors so that work could begin immediately on cutting ramps for DUKWs and preparing bridge and ferry sites. Although first waves were to paddle across in assault boats, reinforcements were to cross in DUKWs and—as at Remagen—LCVPs manned by Naval Unit 2 of the U.S. Navy. With the aid of searchlights mounted on tanks, bridge building was to begin soon after the first infantrymen reached the far shore.8

As the troops prepared for the crossing, the Third Army commander entertained a suggestion from his chief of artillery, Brig. Gen. Edward T. Williams, to speed build-up of reinforcements by a novel method. Williams urged assembling approximately a hundred artillery liaison planes to carry one soldier each to landing fields on the east bank. With each plane making two flights each half hour, a battalion could be airlifted every two hours. Although the 5th Division commander, General Irwin, protested, fearing heavy losses from antiaircraft fire, General Patton went so far as to order a practice flight. Appearance of German planes over the crossing sites eventually would prompt cancellation, but Patton remained convinced the idea was “extremely good.”9

Troops of the 11th Infantry could discern few indications that the Germans would seriously contest the assault. An occasional cluster of shells from artillery and mortars fell in the streets of Nierstein and Oppenheim, reminder enough that an enemy with the power to kill still peopled the far bank, but neither American artillery observers nor aircraft pilots could find lucrative targets.

Only two days had passed since Field Marshal Kesselring had given his blessing to withdrawal of the Seventh Army behind the Rhine, and German commanders were as intent at the moment on re-establishing some semblance of organization in their fleeing remnants as on actually manning a defensive line. Charged with holding more than fifty miles of the Rhine from Wiesbaden, opposite Mainz, to Mannheim, the Seventh Army commander, General Felber, had only one regular corps headquarters, the XIII Corps (General von Oriola), and headquarters of the local military district, Wehrkreis XII. Heretofore engaged solely in recruiting, training, and rear area defense, the Wehrkreis headquarters was summarily upgraded to become the XII Corps, though Felber had no divisions to go with the advancement. In

the entire Seventh Army he possessed only four divisions still organized as such.

Two of those divisions were little more than remnants grouped around their surviving staffs. A third, the 559th Volksgrenadier Division, still had about 60 percent of its normal strength, since some battalions had arrived too late for active commitment in the counterattack role planned west of the Rhine. All three divisions were under the XIII Corps, the 559th near Mannheim, the other two extending the line to the north. The fourth division, the 159th Volksgrenadier, though severely depleted and disorganized, Felber had earmarked as an army reserve.

Thus the provisional XII Corps, charged with the Wiesbaden–Oppenheim sector, had no divisional unit, only rear echelon security detachments, hastily equipped students and cadres from nearby training schools, and convalescent companies. Neither headquarters of the XII Corps nor Felber himself knew much about the numerical strength of these conglomerate forces, but their fighting abilities clearly were limited. Although efforts were under way to rally the residue of other divisions, including the 2nd Panzer, and organize them under division staffs as small task forces, it would be some days before those efforts produced results.10

While Felber and other German commanders might hope the Americans would pause for a systematic build-up before jumping the Rhine, the experience at Remagen and all previous dealings with General Patton indicated otherwise. An immediate attack held particular concern for General Felber, since of three sites along the upper Rhine the Germans considered most suitable for crossing attempts, one was in the Seventh Army sector—at Oppenheim. Yet because of the accidental site where fleeing troops had reassembled after crossing the Rhine, the bulk of the Seventh Army’s formations, the three so-called divisions under the XIII Corps, were well south of Oppenheim.

Despite a promise from the army group commander to bring up more trainees, convalescents, stragglers, anybody to swell the ranks, Felber knew that the only hope of thwarting an immediate crossing at Oppenheim lay with his own reserve, the 159th Volksgrenadier Division. A visit to that command revealed only two weak infantry regiments of two battalions each and two light artillery batteries, plus a few odds and ends.

To complicate matters further, General Felber had lost all communication and contact with the First Army to the south, some of whose units still were fighting on the west bank. To the north contact existed with the LXXXIX Corps, which had withdrawn several days earlier behind the Rhine. On the theory that this corps, holding the sector opposite Koblenz, would be drawn into the fighting against American units breaking out of the Remagen bridgehead, OB WEST had transferred it to Army Group B.

The chances of repelling a blow at Oppenheim, should it come right away, were pathetically meager.

The moon shone with disturbing brightness as men of the 11th Infantry’s

3rd Battalion crept down to the Rhine at Nierstein a few minutes before 2200 the night of 22 March. Half an hour behind schedule, the leading assault boats carrying men of Company K pushed out into the stream. Not a sign of protest arose from the opposite shore.

First to touch down on the east bank was an assault boat carrying a platoon leader, eight men, and Company K’s commander, 1st Lt. Irven Jacobs. The rest of the company arrived safely moments later. Seven surprised Germans promptly surrendered and obligingly paddled themselves across the river without escort.11

Leading the 1st Battalion’s assault a few hundred years upstream at Oppenheim, men of Companies A and B were less fortunate. The assault boats were in midstream when German machine gunners opened fire. The infantrymen and their engineer colleagues had no choice but to paddle straight into the teeth of the fire. Most of them made it, but a fierce skirmish went on for half an hour before the last German defender gave in. For all the noise and apparent ferocity of the defense, the German gunners imposed few losses on the attackers. In the assault crossing of the Rhine, the entire 11th Infantry incurred only twenty casualties.

By midnight all troops of the 11th Infantry were across and ready to drive on the first tier of villages beyond the river, and men of a second regiment had begun their trek to the assault boats. Only at that point did the first hostile artillery fire—a smattering of what might have been expected—begin to fall. Some fifty rounds, for example, including occasional shells from self-propelled guns, fell before daylight on Oppenheim.

Soon after dawn twelve German planes strafed and bombed the crossing sites, the first of a series of aerial raids, usually by only one or two planes, that were to persist throughout the day of 23 March. Damage was negligible. Two men in a battalion command post in Oppenheim were wounded and an ammunition truck was set ablaze, but otherwise the only casualty of the German strikes was General Patton’s scheme to transport infantry reinforcements across the river in artillery liaison planes. American pilots who flew cover most of the day claimed nineteen German planes destroyed.

Success of the assault crossing assured, American commanders concentrated on quick and heavy reinforcement and on putting as much distance as possible between the forward troops and the river. A deep bridgehead was important because of a lack of dominating high ground on which to anchor defense of the bridgehead and because of the absence of a reasonably good road network short of the town of Grossgerau, six and a half miles beyond the river.12

By daylight (23 March) the second of the 5th Division’s regiments was across, and by early afternoon the third. A fourth regiment attached from the 90th Division then followed. During the morning attached tanks and tank destroyers began to move across by ferry and LCVP. A class 40 treadway bridge opened in late afternoon. Engineers speeded traffic to the crossing sites by tearing down fences bordering the main

Reinforcements of the 5th Division cross the Rhine in an LCVP

highway and widening the road to accommodate three lanes of one-way traffic.

The leading infantry battalions fanned out from the crossing sites against varying degrees of resistance. Advancing northeast along the main road toward Grossgerau, the 11th Infantry’s 1st Battalion was pinned down in flare-illuminated open fields short of the first village until platoon leaders and squad sergeants rallied the men and led them forward, employing intense marching fire. “Walking death,” the men called it. At the same time the 3rd Battalion, attacking more directly north, raised scarcely a shot until it reached a small airstrip. There almost a hundred Germans counterattacked with fury, but when the coming of daylight exposed their positions to American riflemen and machine gunners, they began surrendering en masse.

Seldom did the Germans employ weapons heavier than rifles, machine guns, machine pistols, and Panzerfausts, except for occasional mortars and one or two self-propelled guns. With those they staged demonstrations sometimes disturbingly noisy but seldom inflicting casualties. A battalion of the 10th Infantry,

for example, engaged in an almost continuous fire fight while advancing southeast from the crossing sites, took no casualties, and found it unnecessary to call for supporting artillery fire until after midday.

The German units were a veritable hodgepodge: here an engineer replacement battalion, there a Landesschützen replacement battalion, elsewhere a Kampfgruppe of SS troops.13 Most were youths or old men. Having once exhibited a furious spurt of resistance or delivered a reckless counterattack, they were quick to capitulate. The Volkssturm among them often hid out in cellars, awaiting an opportunity to surrender.

By the end of the first full twenty-four hours of attack beyond the Rhine, the radius of the 5th Division’s bridgehead measured more than five miles, and Grossgerau and its essential network of roads lay little more than a mile away. So obvious was the success of the surprise crossing that in late afternoon of 23 March the corps commander, General Eddy, ordered the 4th Armored Division to start across early on the 24th, the first step toward exploitation.

Anticipating quick commitment of American armor and with it loss of any hope, however faint, of annihilating the bridgehead, the Seventh Army’s General Felber struggled through the day of the 23rd to mount a counterattack. Although Felber believed the Americans intended to drive east against Darmstadt rather than northeast toward Frankfurt, he chose to make his main effort against the northern shoulder of the bridgehead where he believed the Americans to be weakest. Also, a regimental-size unit formed from students of an officer candidate school in Wiesbaden had become available for commitment there. Augmented by a few tanks and assault guns, this force was potentially stronger than the army reserve, the depleted 159th Volksgrenadier Division.

Still disorganized from the flight across the Rhine and harassed all day by American fighter-bombers, the Volksgrenadiers were far from ready to launch a projected subsidiary thrust against the eastern tip of the bridgehead when at midnight, 23 March, General Felber decided he could delay no longer. Not only did the thought of the pending advent of American armor disturb him, but Felber also had to endure the critical eyes of his superiors, the Commander in Chief, Field Marshal Kesselring, and the Army Group G commander, General Hausser, both of whom watched the preparations anxiously from the XII Corps command post in Grossgerau. The officer candidates, Felber directed, would have to go it alone.

Only moments after midnight the student officers struck three villages along the northern and northeastern periphery of the bridgehead. Although the Germans displayed a creditable elan, the presence of two battalions of American infantry in each village made the outcome in all three inevitable. Infiltrating Germans caused considerable confusion through the hours of darkness, particularly when they took three of the battalion command posts under fire; but the coming of day enabled 5th Division infantrymen to ferret them out quickly. Although other Germans outside the villages remained close, fire from some of the seventeen artillery battalions that already

had moved into the bridgehead and from sharpshooting riflemen and machine gunners soon either dispersed the enemy or induced surrender.

The 159th Volksgrenadier Division apparently never got into the fight in strength. A subsidiary thrust against a village on the southeast edge of the bridgehead caused some concern when it struck moments after a battalion of the 90th Division had relieved a battalion of the 10th Infantry, but nothing more developed. A battalion of the 10th Infantry, moving up for a dawn attack, bumped into a German column moving down a road and may have been responsible. The Germans fled in disorder.

Even before the defeat of the counterattacks put a final seal on success of the Rhine crossing, the 12th Army Group commander, General Bradley, released news of the feat to the press and radio. American forces, Bradley announced, were capable of crossing the Rhine at practically any point without aerial bombardment and without airborne troops. In fact, he went on, the Third Army had crossed the night of 22 March without even so much as an artillery preparation.14

Both the nature and the timing of Bradley’s announcement were aimed at needling Field Marshal Montgomery, whose 21 Army Group was then crossing the Rhine after an extensive aerial and artillery bombardment and with the help of two airborne divisions. Although General Patton had informed Bradley of his coup at the Rhine early on the 23rd, he had asked him to keep the news secret; shortly before midnight he telephoned again, this time enjoining Bradley to reveal the event to the world. Thus the announcement came at a time calculated to take some of the luster from news of Montgomery’s crossing.

Some officers of the Third Army’s staff drew added delight from the fact that the British Broadcasting Corporation the next day played without change a prerecorded speech by Prime Minister Churchill, praising the British for the first assault crossing of the Rhine in modern history. That distinction everybody knew by this time belonged not to the 21 Army Group but to the Third Army.15

The VIII Corps in the Rhine Gorge

As if to furnish incontrovertible proof for General Bradley’s boast that American troops could cross the Rhine at will, the Third Army was readying two more assault crossings of the river even as Montgomery’s 21 Army Group jumped the lower Rhine. Ordered on 21 March, shortly after Patton approved plans of the XII Corps for crossing at Oppenheim, the new crossings actually reflected a concern for success of the Oppenheim maneuver and of the subsequent crossing of the Main River that was intrinsic in the original decision to go at Oppenheim.16

Responsibility for both new Rhine crossings fell to General Middleton’s VIII Corps, its boundaries adjusted and its forces augmented following capture of Koblenz. Before daylight on 25 March, the 87th Division was to cross near Boppard,

a few miles upstream from Koblenz. Slightly more than twenty-four hours later, in the early hours of 26 March, the 89th Division—transferred from the XII Corps—was to cross near St. Goar, eight miles farther upstream.17

After establishing a firm hold on the east bank in the angle formed by confluence of the Lahn River with the Rhine, the 87th Division on the left was to be prepared to exploit to the east, northeast (toward juncture with First Army troops from the Remagen bridgehead), or southeast (toward the rear of any enemy that might be defending the Main River). The 89th Division was earmarked for driving in only one direction, southeast. The two divisions were, in effect, to begin clearing a pocket that was expected to develop between the First Army and the XII Corps.

Terrain, everybody recognized, posed a special challenge. The sector assigned to the VIII Corps, from Koblenz upstream to Bingen, embraced the storied Rhine gorge. There the river has sheared a deep canyon between the Hunsrück Mountains on the west and the Taunus on the east. Rising 300 to 400 feet, the sides of the canyon are cliff-like, sometimes with rock face exposed, other times with terraced vineyards clinging to the slopes. Between river and cliff there usually is room only for a highway and railroad, though here and there industrious German hands through the years have foraged enough space to erect picturesque towns and villages. These usually stand at the mouths of sinuous cross-valleys where narrow, twisting roads provide the only way out of the gorge for vehicles.

So sharply constricted, the Rhine itself is swift and treacherous, its banks in many places revetted against erosion with stone walls fifteen feet high. Here, just upstream from St. Goar, stands the Lorelei, the big rock atop which sits the legendary siren who lures river pilots to their deaths on outcroppings below. Here in feudal times lived the river barons who exacted toll from shippers forced to pass beneath their castles on the heights. Here still stood the fabled castles on the Rhine.

A more unlikely spot for an assault crossing no one could have chosen. This very fact, General Patton claimed later, aided the crossings.18 Whether infantrymen who braved the tricky currents and the precipitous cliffs would agree is another matter.

Certainly General Höhne’s LXXXIX Corps, defending the Rhine gorge, was relatively better prepared for its job than were those Germans on the low ground opposite Oppenheim; that preparation was attributable less to expected attack than to the simple fact that the LXXXIX Corps had had almost a week behind the Rhine. Höhne’s corps would have been considerably better prepared had not Field Marshal Kesselring ordered transfer on the eve of the American assault of the 6th SS Mountain Division, still a fairly creditable unit with the equivalent of two infantry regiments and two light artillery battalions. Kesselring sent the divisions to the southeast

toward Wiesbaden, probably in reaction to the Oppenheim crossing, not from any sense of complacency about the Rhine gorge.

Transfer of the SS mountain division left General Höhne with what remained of the 276th Volksgrenadier Division (some 400 infantrymen and 10 light howitzers), a few corps headquarters troops, a conglomerate collection of Volkssturm, two companies of police, and an antiaircraft brigade. The antiaircraft troops were armed mainly with multiple-barrel 20-mm. pieces, most of them lacking prime movers.19

On the 87th Division’s left (north) wing, it would have been hard to convince anybody in the 347th Infantry that the Rhine gorge afforded advantages of any kind for an assault crossing. At one battalion’s crossing site at Rhens, “all hell broke loose” from the German-held east bank at five minutes before midnight, 24 March, six minutes before the first wave of assault boats was to have pushed into the stream.20 Fire from machine guns, mortars, 20-mm. antiaircraft guns, and some artillery punished the launching site. Almost an hour passed before the companies could reorganize sufficiently for a second try. Possibly because few of the defenders had the stomach for a sustained fight, the second try at an assault proceeded with little reaction from the Germans. Once on the east bank, the men “let loose a little hell of their own.”

A few hundred yards downstream leading companies of another battalion moved out on time, apparently undetected, but hardly had they touched down when German flares flooded the river with light. Men of the follow-up company drew heavy fire, and at both this site and the one at Rhens the swift current snatched assault boats downstream before they could return for subsequent waves. Reluctance of engineers to leave cover on the east bank to paddle another load of infantrymen across the exposed river added to the problem. All attempts at organized crossing by waves broke down; men simply crossed whenever they found an empty boat. After daylight an attempt to obscure German observation by smoke failed when damp air in the gorge prevented the smoke from rising much above the surface of the water. In early afternoon the 347th Infantry’s reserve battalion still had been unable to cross when the assistant division commander, Brig. Gen. John L. McKee, acting in the temporary absence of the division commander, ordered further attempts at the site abandoned.

Upstream at Boppard, two battalions of the 345th Infantry had experiences more in keeping with Patton’s theory that crossing in the inhospitable Rhine gorge eased the burden of the assault. Although patrols sent in advance of the main crossings to take out enemy strongpoints drew heavy fire, the assault itself provoked little reaction. The leading companies made it in twelve minutes, and engineers were back with most of the assault boats in eight more. In contrast to 7 men killed and 110 wounded in the battalion of the 347th Infantry

that crossed at Rhens, one of the battalions at Boppard lost 1 man killed and 17 wounded. In midafternoon General McKee made up for the lack of a reserve with the 347th Infantry opposite Rhens by sending a battalion of his reserve regiment to cross at Boppard and advance downstream to help the other regiment.

For neither assault regiment was the going easy once the men got ashore, but both made steady progress nevertheless. Machine guns and 20-mm. antiaircraft guns were the main obstacles, particularly the antiaircraft pieces, which were strikingly effective against ground troops. Although plunging fire is seldom so deadly as grazing fire, the spewing of these guns was painful even when it came from positions high up the cliffs.

By late afternoon the 345th Infantry had a firm hold on high ground lying inside a deep curve of the Rhine opposite Boppard, and the 347th had a similar grasp on high ground and the town of Oberlahnstein at the juncture of the Lahn and the Rhine. Probably reflecting the presence of the 276th Infantry Division around Oberlahnstein, the only counterattack of the day—and that of little concern—struck a battalion of the 347th Infantry. The worst obviously over with the assault crossing itself, General McKee readied his reserve regiment to extend the attack to the east early the next morning.

Throughout the morning of 25 March the 89th Division commander, General Finley, watched progress of the 87th’s attack with the hope that part of his division might use the Boppard crossing site and sideslip back into its own zone, thereby obviating another direct amphibious assault. As the day wore on, he reluctantly concluded that congestion and continued enemy fire at Boppard meant he had to go it alone.

The experiences of both assault regiments of the 89th Division turned out to be similar to those of the 347th Infantry. Time and places were different (0200, 26 March, at St. Goar and Oberwesel), and the details varied, but early discovery by the Germans, the flares, erratic smoke screens, and the seemingly omnipresent 20-mm. antiaircraft guns were the same.

As at Rhens, for example, a battalion of the 354th Infantry at St. Goar came under intense German fire even before launching its assault boats. Flares and flame from a gasoline-soaked barge set afire in midstream by German tracers lit the entire gorge. Into the very maw of the resistance men of the leading companies paddled their frail craft. Many boats sank, sometimes carrying men to their deaths. Others, their occupants wounded, careened downstream, helpless in the swift current. A round from an antiaircraft gun exploded in Company E’s command boat, killing both the company commander, Capt. Paul O. Wofford, and his first sergeant.

Although their ranks were riddled, the two leading companies reached the east bank and systematically set about clearing the town of St. Goarshausen. Most of the 89th Division’s casualties (29 killed, 146 missing, 102 wounded) were sustained by the 354th Infantry.

Perhaps the most unusual feature of the 353rd Infantry’s crossing upstream at Oberwesel was the use of DUKWs for ferrying reinforcements even before the crossing sites were free of small arms fire. Word had it that an anxious, determined, division commander, General Finley, personally prevailed upon engineers

Crossing the Rhine under enemy fire at St. Goar

at the river to put the “ducks” of the 453rd Amphibious Truck Company to early use. Capable of carrying eighteen infantrymen at once, the DUKWs speeded reinforcement. They also made less noise than power-propelled assault boats, and when noise more often than not invited enemy shelling, that made a difference.

Having organized two light task forces for exploiting the crossings, General Finley was eager to get them into the fight. When by noon he determined that both regimental bridgeheads still were too confined for exploitation, he arranged to fall back on his earlier hope of using the 87th Division’s site at Boppard. There a bridge was already in place.

In midafternoon the first of the two task forces began to cross at Boppard. Almost coincidentally, resistance opposite both St. Goar and Oberwesel began to crumble, revealing how brittle and shallow was the defense. In late afternoon, following a strike by a squadron of P-51 Mustangs, riflemen of the 354th Infantry carried rocky heights near the Lorelei, eliminating the last direct fire from the St. Goar crossing site. A few minutes later they raised an American flag atop the Lorelei.

Raising the American flag atop the Lorelei overlooking the Rhine gorge

As night fell on 26 March, report after report reaching the VIII Corps commander, General Middleton, indicated that the enemy’s Rhine defense everywhere was collapsing. Fighter pilots told of German vehicles trying to withdraw bumper-to-bumper down roads clogged with soldiers retreating on foot. Shortly before dark the 87th Division’s 345th Infantry broke away from the Rhine cliffs for a five-mile gain. Even more encouraging news came from other units to the north and south. From the north an armored column emerging from the First Army’s Remagen bridgehead down the Ruhr–Frankfurt autobahn seized Limburg on the Lahn River and was pointed across the VIII Corps front toward Wiesbaden. To the south the Oppenheim bridgehead too exploded. Reacting to the obvious implications of these developments but lacking an armored division to exploit them, General Middleton told the 6th Cavalry Group to divide into light armored task forces and head east the next day.

What might well become the last big pursuit of the war appeared to be starting.

To the Main River and Frankfurt

The first explosion from the Oppenheim bridgehead came during the afternoon of 24 March soon after Combat Command A arrived as vanguard of the 4th Armored Division. The armor headed southeast to swing around the city of Darmstadt before setting out on the main axis of attack to the northeast. Once started, CCA’s tankers and armored infantrymen appeared loath to halt. Taking advantage of a bright moonlit night, the combat command finally stopped after midnight only after half encircling Darmstadt and reaching a point more than fifteen miles from the Oppenheim crossing site.21

The spectacular start of the armor prompted the German Seventh Army’s General Felber to abandon defense of Darmstadt. “In order to avoid the unnecessary annihilation of the few forces committed for the defense of the city,” Felber rationalized later.22 Felber’s action enabled the 4th Armored Division’s reserve combat command to move in with little difficulty the next day.

On 25 March the explosion became a general eruption. Leaving the jobs of mopping up and expanding the base of the bridgehead to infantry divisions, the XII Corps commander, General Eddy, ordered the 6th Armored Division into the bridgehead to strike directly northeast for a crossing of the Main River between Frankfurt and Hanau. Combat Commands A and B of the 4th Armored Division also headed for the Main, one at Hanau, the other fifteen miles upstream at Aschaffenburg.

Having earlier missed an opportunity at the Moselle, men and commanders in both combat commands seemed obsessed with one thought: get a bridge. In both cases the obsession paid off. Held up along a main highway by 20-mm. flak guns, CCA left a platoon each of tanks and infantry to deal with the opposition, then continued the advance over back roads and trails. A mile upstream from Hanau, the combat command found a railway bridge to which an appendage had been added for vehicular traffic. At

the last moment the Germans set off demolitions. Although they effectively blocked the railway portion of the bridge, the appendage, though damaged, still hung in place. While supporting artillery placed time fire over the bridge to deny the Germans a second chance, a company of armored infantry got ready to cross. Despite mines and booby traps that killed six men and wounded more than ten, the infantry made it. About the same time, Combat Command B at Aschaffenburg took a railway bridge intact.

German efforts to dislodge the attackers were relatively feeble at Aschaffenburg but caused considerable concern near Hanau, where only two companies of armored infantry were yet across the river and where the damaged bridge had so deteriorated that neither tanks nor additional foot troops could cross. Not long before dark a train bearing German troops and four 150-mm. railway guns arrived in the town opposite the bridge. Although the troops apparently were surprised to find Americans in the town, they quickly set out to drive them into the river. Men of both sides soon were so intermingled that for a while American artillery dared not risk firing on the German guns. Fighting raged at close quarters until well after dark when American engineers completed a treadway bridge and a third company of armored infantrymen joined the fray. By midnight the Americans were in firm control of the town.

Early the next morning, 26 March, the 6th Armored Division’s Combat Command A dashed through a large forest south of Frankfurt, bypassing the sprawling Rhine-Main Airport, which infantry of the 5th Division would clear later in the day. In early afternoon the combat command reached the Main at Frankfurt’s southern suburb of Sachsenhausen. There General Grow’s armor also found a bridge still standing, although too damaged by demolitions for vehicles to use. A company of armored infantry crossed quickly to secure a few buildings at the north end of the bridge.

What the demolitions had failed to accomplish, German self-propelled guns inside Frankfurt and big stationary antiaircraft pieces on the periphery of the city tried to redeem. Almost any movement in the vicinity of the bridge was sufficient to bring down a rain of deadly shelling, much of it airbursts from the antiaircraft pieces. A battalion of the 5th Division’s 11th Infantry nevertheless dashed across the bridge soon after nightfall and began to expand the slim holdings of the armored infantrymen on the north bank.

All through the next day the German shelling continued to be so intense that engineers had no success trying to repair the bridge to enable tanks and tank destroyers to cross. During lulls in the enemy fire, more infantrymen of the 5th Division nevertheless managed to reach the north bank and get on with the task of clearing the rubble-strewn city, where police and some civilians along with a hodgepodge of military defenders tried in vain to deny the inevitable.

The Hammelburg Mission

News of the crossing of the Main at Aschaffenburg had in the meantime excited the Third Army commander. General Patton saw in it an opportunity for a foray deep into German territory to liberate hundreds of American prisoners

of war from an enclosure near Hammelburg, some thirty-five miles to the northeast. A successful thrust to Hammelburg would outdo a similar raid executed a month earlier by General Douglas MacArthur’s forces in the Philippine Islands, while possibly concealing from the Germans the Third Army’s pending change of direction to the north.

The man whose troops would have to carry out the foray was the 4th Armored Division commander, General Hoge, one of the heroes of Remagen who only a few days earlier had assumed command of the division when General Gaffey moved up to a corps. Both Hoge and the XII Corps commander, General Eddy, deplored Patton’s scheme. When they failed to talk him out of it, General Eddy insisted on sending a small armored task force instead of diverting an entire combat command as Patton suggested. The change further upset Hoge, as it did the commander of CCB, Lt. Col. Creighton W. Abrams, whose command received the assignment. Both Hoge and Abrams believed a small task force would be destroyed, but they failed to convince Eddy.

To make the thrust, Colonel Abrams created a task force built around a company each of CCB’s 10th Armored Infantry and 37th Tank Battalions. Because of the illness of the infantry battalion commander, the infantry S-3, Capt. Abraham J. Baum, took command. Basic armament consisted of 10 medium and 6 light tanks, 27 half-tracks, and 3 self-propelled 105-mm. assault guns.

Strength totaled 293 officers and men, and Maj. Alexander Stiller, one of Patton’s aides, as well. Although Stiller outranked Baum, the understanding was clear that Baum was in full command. Stiller told both General Hoge and Colonel Abrams that he wanted to go along “only because General Patton’s son-in-law [Lt.] Colonel [John K.] Waters, was in the prison camp.”23

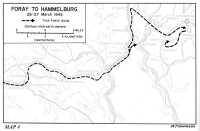

Captain Baum’s mission was to proceed as rapidly as possible to the prisoner-of-war camp two miles south of Hammelburg. (Map 4) He was to load all vehicles to capacity with liberated prisoners for the return trip and to give the remaining prisoners a choice either of accompanying the task force on foot or making their way on their own to American lines.

As Baum’s little task force began to move shortly after midnight, 25 March, small arms fire in the first few towns inflicted a number of casualties; but in general the Germans along the route were too surprised to fight back. It was still dark when at Lohr, just past the midpoint of the journey, the task force stumbled on a column of German vehicles

Map 4: Foray to Hammelburg, 25–27 March 1945

heading west. Not even pausing in the advance, the American tankers opened fire, destroying twelve German vehicles with a loss of one medium tank. Outside Lohr they destroyed a German locomotive, and just before dawn at Gemünden, three-fourths of the way to Hammelburg, they shot up seven more.

On the outskirts of Gemünden, defending Germans destroyed two more of Baum’s tanks and blew up a bridge over a small stream, forcing a detour to the north. It was well into the day of 26 March when, a few miles from Hammelburg, the task force liberated about 700 Russian soldiers, to whom they entrusted some 200 Germans captured in the course of the journey. A short while later the men spotted a German liaison plane hovering near the column.

To Baum and his men the plane spelled trouble—an airborne Paul Revere alerting the German command against the thrust—but it actually mattered little, for the alarm already had been sounded. In advancing toward Lohr, Task Force Baum had passed within two miles of headquarters of the Seventh Army, which had escaped from Darmstadt and Aschaffenburg only steps ahead of the 4th Armored Division columns. For want of anything better, the staff quickly alerted headquarters of the local Wehrkreis.24

It was not this alert but mere chance that actually was responsible for the troubles that began to beset Task Force Baum. In midafternoon, as the task force sought to bypass the town of Hammelburg, a German assault gun battalion that had arrived only minutes before opened fire.25 It took two hours of hard fighting and the loss of three more medium tanks, three jeeps, and seven half-tracks, including one loaded with precious gasoline, for the American column to force a way through. The Germans’ loss of three assault guns and three ammunition carriers was small consolation for the American losses and the delay.

When at last Task Force Baum approached the prisoner-of-war enclosure, the tankers mistook Yugoslav prisoners for Germans and opened fire. At the request of the camp commandant, three U.S. officers volunteered to go with a German officer under a makeshift American flag to have the fire lifted. One of the Americans was Colonel Waters, Patton’s son-in-law, captured two years earlier in North Africa. As the group marched beyond the enclosure, a German soldier in a nearby barnyard fired one round from a rifle, wounding Colonel Waters.

While the other officers were taking Colonel Waters back to the compound, the tanks of Task Force Baum broke the wire enclosure. The pandemonium of liberation took over. The number of prisoners far exceeded any previous estimate: 4,700, of whom 1,400 were American officers. While as many as possible climbed aboard the remaining tanks and half-tracks, others formed to march alongside.

Well after dark Task Force Baum—reduced to about 110 men and only four of its medium tanks—started the return journey. By that time Germans rallied by an unidentified major home on leave in Hammelburg were ready. A round from a Panzerfaust knocked out Baum’s leading tank a scant fifty yards from the prisoner-of-war enclosure. All hope of the physically unfit’s accompanying the task force faded. They returned under a white flag to the enclosure.

Seeking to avoid the apparent German strength near Hammelburg, Captain Baum turned the task force to the southwest; but at the village of Hessdorf, five miles away, another contingent of Germans equipped with Panzerfausts lay in wait. There Baum lost two light tanks and one more medium.26

Retiring to a nearby hill to reorganize, Baum found the gasoline in his remaining vehicles dangerously low. He directed the men to siphon the fuel from eight of the half-tracks, then to destroy them. He placed the seriously wounded men in a building marked with a red cross, then readied the rest of the force, which included some sixty-five of the liberated prisoners, for another try at the return journey.

They had yet to move out when, just before daylight (27 March), a dozen German tanks supplemented by assault guns opened fire. Under cover of this fire, two companies of German infantry attacked. In rapid succession, one after another of Baum’s tanks and other vehicles

General Haislip

went up in flames. His position apparently hopeless, Baum called a council of war. His instructions were brief. The survivors were to form in groups of three or four and attempt to infiltrate through the converging Germans and make their way to American lines.

Baum himself tried to escape in company with an unidentified lieutenant and Major Stiller. For most of the day they successfully kept under cover, while in the distance they could hear the baying of bloodhounds as the Germans methodically tracked down the survivors. Just before dark a German sergeant spotted the three officers. He fired, striking Captain Baum in a leg (his third wound of the operation). There seemed little choice but to surrender.

Over the next few days, fifteen men from Task Force Baum made their way back to American lines. Nine were established as killed, 16 missing, 32 wounded, the others captured. There remained only for the Germans to make propaganda of the ill-starred raid. An entire American armored division attacking Hammelburg, the Germans claimed, had been destroyed.27

The Seventh Army Crossing at Worms

As disappointing and tragic as was the outcome of the raid on Hammelburg, it was a relatively minor incident in an otherwise uninterrupted surge of Allied power against and beyond the Rhine defenses. General Patch’s Seventh Army, its West Wall breakthrough and mop-up in the Saar-Palatinate completed, added its strength to that surge before daylight on 26 March, even as Task Force Baum began its ill-fated drive.

Before the ease and extent of the victory in the Saar-Palatinate had become apparent, the Supreme Commander, General Eisenhower, had offered an airborne division (the 13th) to help the Seventh Army across the Rhine. Primarily because of the advantages the hills and forests of the Odenwald, east of Worms, would afford as a barrier to hostile movement against an airhead, General Eisenhower’s planners focused their attention on a crossing near Worms. From the viewpoint of advance beyond the bridgehead, the Seventh Army would have preferred a crossing about twenty miles to the south near Speyer, for there a plateau between the Odenwald and the Black Forest provides egress to the east. On the other hand, the help inherent in

an airborne attack was a compelling argument.28

After the unexpectedly rapid and deep intrusion of the Third Army into the Saar-Palatinate sharply narrowed the Seventh Army’s Rhine frontage, Worms lost some of its attraction as a crossing site because it then lay on the extreme left of the Seventh Army’s zone. News that preparations for the airborne assault could be completed only near the end of March took away still more of the lure. Then the Third Army’s successful crossing of the Rhine at Oppenheim made Worms attractive again, even while making it obvious that an airborne assist would be unnecessary. The advantages of making the assault close to the Third Army’s already established bridgehead, General Patch decided, outweighed other factors. Ordering his VI and XXI Corps to make contingent plans for subsidiary crossings near Speyer, he told General Haislip’s XV Corps to make the main thrust at Worms.29

Mop-up of German pockets on the west bank, relief of Third Army divisions that had violated the inter-army boundary, and the time-consuming trek of convoys bearing boats and bridging equipment from far in the rear imposed inevitable delay on the assault. Not for the Seventh Army a running broad-jump like that of the Third Army’s 5th Division. General Haislip’s XV Corps was to make a deliberate two-division assault, the 45th Division just north of Worms, the 3rd Division just south of town, with two more infantry divisions and a cavalry group scheduled for quick follow-up. The attack was to begin at 0230, 26 March.30

The mechanics of getting ready rather than concern for enemy strength dictated the timing of the Seventh Army assault. Although intelligence officers estimated that remnants of twenty-two divisions had escaped across the Rhine in the general area, they could not believe, in view of the confusion accompanying their flight, that the German units represented any formidable strength. The Third Army’s experience at Oppenheim corroborated the view, as did the experience of several reconnaissance patrols. One patrol, led by a battalion commander of the 45th Division’s 180th Infantry, reconnoitering on the east bank for half an hour the night of 24 March, found no mines, barbed wire, or emplacements. Although the men saw a few Germans and believed the Germans saw them, they drew no fire.31

Based on the actual German situation, General Patch’s reasoning in deciding to cross the Rhine near Worms was justified. Those Germans manning the east bank were part of the same Seventh Army that had already been rent asunder by the Third Army crossing. The sector came under General von Oriola’s XIII Corps, already affected by the American attack at Oppenheim.

This was the corps that had one fairly respectable divisional unit, the 559th Volksgrenadier Division, located at

Mannheim. Two other units that went by the names of the 246th and 352nd Volksgrenadier Divisions, extending the line northward, were Kampfgruppen of about 400 men each. When the U.S. 4th Armored Division had broken out from the Oppenheim bridgehead on 24 March, the northernmost 352nd Division had had to fall back.32

Like almost all German commanders in the vicinity, General von Oriola expected the American armor to turn southeast to cut in behind the Odenwald and trap the adjacent First Army or at least to expand the Oppenheim bridgehead southward as far as Mannheim and the Neckar River. Two major north-south highways, the Darmstadt–Mannheim autobahn on the Rhine flats and the Bergstrasse, the latter forming a dividing line between the Odenwald hills and the Rhine lowlands, invited a turn to the south. In a feeble effort to forestall such a move, Oriola turned the retreating remnants of the 352nd Division to face northward astride the highways.

Defense of the Rhine itself north and south of Worms was left to the 246th and 559th Volksgrenadier Divisions, whose numbers permitted only “very sparse” occupation of the east bank and no depth at all.33 The lack of depth was particularly disturbing because of the exposed nature of the defensive positions on the Rhine flats. The only corps reserve of any kind was an assault gun brigade that still had five guns. Artillery consisted of six understrength battalions, plus some ninety stationary antiaircraft pieces around Mannheim.

The new American assault against the Rhine would begin before any major realignment of German forces in response to the Oppenheim breakout occurred; but before the first day of the new attack came to an end, Oriola’s XIII Corps was destined to be transferred to the First Army. That was a logical move since the American breakout had effectively split the Seventh Army and since the First Army appeared seriously threatened should the Americans turn southeast or south.

General Foertsch’s First Army had escaped across the Rhine in slightly better shape than had the Seventh Army, but still was in no condition to pose any real challenge. It had three corps headquarters and the skeletons of twelve divisions, though two of the latter were en route to the Seventh Army the night of 25 March and three others were in such a condition that General Foertsch had sent them to the rear in hope somehow of reconstituting them. That left seven, few of which were anything more than regimental-size Kampfgruppen. To provide an army reserve, Foertsch counted on the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division, whose troops got behind the Rhine only late on the 25th and would require at least a day or two to reorganize.34

To know the status and locations of the major units in the German XIII Corps is to possess the basic ingredients of the story of the Rhine crossing by the Seventh Army XV Corps. In the zone of the 45th Division, north of Worms, where the weak Kampfgruppe called

246th Volksgrenadier Division barred the way, it was a case of fierce initial opposition from small arms, machine guns, mortars, and small caliber antiaircraft pieces, then a collapse. In the zone of the 3rd Division, where the 559th Volksgrenadier Division had 60 percent of normal strength and where the big (up to 128-mm.) antiaircraft guns protecting Mannheim were in effective range, it was different.

Vigilant German pickets opposite the 3rd Division, perhaps alerted by feigned crossing attempts to the south near Speyer, detected movement on the American-held west bank well before the H-hour of 0230. The Germans opened fire, primarily with mortars and antiaircraft guns, seriously hampering American engineers who were trying to move assault boats to the water’s edge and to shave the steep revetted banks for the amphibious vehicles that were to come later. Surprise compromised, American artillery opened a drumbeat of fire. In thirty-eight minutes the artillery expended more than 10,000 rounds, “painting the skyline a lurid red.”35

Despite the light from a burning barn that illuminated the crossing site, little German fire fell as the first wave of infantrymen pushed into the stream. The artillery support had done its job well. The first wave of “storm boats” (metal pontons propelled by 50-hp. outboard motors) took less than a minute to cross the thousand feet of water. Only then, as the artillery desisted, did enemy fire begin to fall in disturbing volume.

In the 45th Division sector, supporting artillery held its fire, for the hope was that the crossing preparations had gone undetected. The hope proved vain. Although the first wave got almost across before the Germans came to life, the far bank at that point seemed to erupt with fire. The infantrymen had to come ashore with rifles and submachine guns blazing. For the better part of an hour a fight raged, while succeeding waves of boats took a fierce pounding. In the 180th Infantry’s sector more than half the assault boats in the second and third waves were lost, but once the first flush of resistance was over, men of the 45th Division began to push rapidly eastward.

About the only opposition that developed from then on came in the villages. Planes that kept a constant vigil over the battlefield all day helped eliminate this resistance, by nightfall contact had been established with contingents of the Third Army on the left, and forward troops were across the Darmstadt–Mannheim autobahn, a good eight miles beyond the Rhine.

The 3rd Division, the effect of its artillery preparation dissipated, lagged behind. One problem was an incessant chatter of machine gun and antiaircraft fire from an island in an offshoot of the Rhine southeast of Worms. Despite a smoke screen laid at the crossing sites, the fire hampered follow-up operations until well after midday when a battalion of the 15th Infantry cleared the island after an amphibious assault against the enemy’s rear. Elsewhere the main resistance centered in the villages and in every cluster of houses. At two of the villages the Germans of the 559th Volksgrenadier Division crowned their opposition with counterattacks supported by self-propelled guns and mobile 20-mm. flakwagons.

Infantry of the 3rd Division climb the east bank of the Rhine

Here and in the 45th Division sector amphibious tanks that crossed the Rhine close behind the infantry assault waves were put to good use. These were “DD” (duplex drive) tanks, M4 mediums equipped with twin propellers for propulsion in the water and with a normal track drive for overland. An accordion-like canvas skirt enabled the tank to float. Of twenty-one DD tanks supporting the 3rd Division, fifteen made it across the river. Of the six that failed, one was destroyed by shellfire before crossing, one stuck in the mud at the water’s edge, the canvas on two was badly torn by shell fragments before the crossing, and two others sank after fragments punctured their canvas during the crossing. All fourteen DD tanks assigned to the 45th Division crossed safely.

As night came, troops of the 3rd Division still had to pick their way through some two miles of thick forest before reaching the autobahn, and on the south flank heavy fire from the antiaircraft guns ringing Mannheim still proved troublesome. Indications nevertheless were developing that the 559th Volksgrenadier Division at last was giving up and that the XV Corps would be ready

early the next morning, 27 March, to make the most of it. Already both a treadway bridge and a heavy ponton bridge were supplementing DUKWs, rafts, and ferries serving the 3rd Division, and bridges were nearing completion behind the 45th Division. All artillery normally supporting the four assault regiments was across, and the Seventh Army commander, General Patch, had ordered transfer of the 12th Armored Division to the XV Corps for exploitation. During the crossing operations more than 2,500 Germans had surrendered, while XV Corps casualties reflected more noise than effect in the day’s German fire. Losses totaled 42 killed and 151 wounded.36

The XX Corps in the Rhine–Main Arc

By nightfall of 26 March General Bradley’s 12th Army Group had established four solid bridgeheads across the Rhine—the First Army’s at Remagen, the Third Army’s VIII Corps along the Rhine gorge and XII Corps at Oppenheim, and the Seventh Army’s XV Corps at Worms. A fifth was pending, for the Third Army’s General Patton still had one corps on the Rhine’s west bank that he chose to send across by assault rather than by staging through either of his already established bridgeheads. He wanted General Walker’s XX Corps to cross between his other two corps at Mainz.

Just why Patton chose to make another assault crossing at this stage is mainly conjectural. He probably disdained any thought that the Germans could seriously interfere with a new crossing. Patton also wanted to get on with the task of building permanent rail and highway bridges across the Rhine to speed his army’s advance. Mainz with its network of roads and railways and its central location in relation to the army boundaries was the logical spot for the bridges; and an assault crossing appeared the quickest way to free the east bank of Germans.37

Patton’s original plan was to send a regiment from the already established VIII Corps bridgehead southeastward along the Rhine’s east bank to support the new assault crossing by seizing high ground overlooking the crossing site. The 80th Division of the XX Corps then was to cross at Mainz. Eddy’s XII Corps was to continue its drive to cross the Main River east of Frankfurt, whereupon all three corps were to head for the same objective, the town of Giessen and juncture with the First Army. “I told each Corps Commander that I expected him to get there first,” Patton recalled later, “so as to produce a proper feeling of rivalry.”38

Somewhere along the line, Patton did away with the preliminary thrust to take the high ground overlooking the 80th Division crossing site. The reason went unrecorded, but it may have been because of the explosive dash of an armored

Duplex-Drive tank with skirt folded

division from the First Army bridgehead that looked for awhile as if it would carry to Wiesbaden, across the Rhine from Mainz. In late afternoon of 26 March, the 12th Army Group chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Leven C. Allen, telephoned the news that the armor had seized a bridge intact over the Lahn River at Limburg, less than twenty miles from Wiesbaden. If the Third Army approved, a combat command was prepared to cut across the front of the VIII Corps and capture Wiesbaden.39

Patton did approve, but it was well into the next day, 27 March, before the armored force could start its drive; although a bridge had been captured, the Germans had blown it after only four tanks had crossed. When units of Middleton’s VIII Corps broke out of their bridgehead early on the 27th, their columns quickly became entangled in those of the combat command. The objective soon ceased to be getting the armor to Wiesbaden; it became instead getting it out of Middleton’s way. With the XX Corps scheduled to launch its crossing of the Rhine before daylight the next morning,

Duplex-Drive tank enters the water

chances were the attackers would find no friendly forces either in Wiesbaden or along the Rhine opposite Mainz.

Details of the XX Corps plan were worked out not by Patton but by his chief of staff, General Gay, while Patton was in the XII Corps bridgehead setting up Task Force Baum.40 The 80th Division (General McBride) was to send one regiment across the Rhine at Mainz while another regiment, having crossed into the XII Corps bridgehead, was to jump the Main River three miles upstream from the Rhine opposite Hochheim. Forces from the two bridgeheads then were to converge to clear the angle or arc formed by the confluence of the Main and the Rhine. Aside from the obvious advantages of dividing the opposition with two crossings, the decision to jump the Main as well as the Rhine hinged on a desire to make full use of existing stocks of bridging equipment; the stocks were insufficient for two Rhine bridges but would suffice for one over

the Rhine and another over the narrower Main.41

The Germans remaining in the Rhine-Main arc would give the XX Corps commander, General Walker, and his staff little pause. Even a cautious G-2 could find reason to believe that but one divisional unit and a hodgepodge of lesser forces defended there, and the estimate of even one divisional unit was actually in error. To the Germans it was quite apparent that Wiesbaden and the surrounding sector were soon to be either captured or encircled; the Americans in the bridgeheads both north and south of the city would see to that. With this in prospect, no one on the scene would have been willing to leave sizable forces in the threatened arc—even had they been available.

The same provisional XII Corps that had come to grief in the Oppenheim bridgehead had borne responsibility for this part of the front as well until midday 25 March, when General Kniess and the staff of his LXXXV Corps arrived. Theirs was a thankless, hopeless task; indeed, part of the staff had trouble even getting to the scene. Having been sent northward by Army Group G, the staff found American armor pouring out of the Oppenheim bridgehead and had to make a long detour to the east to avoid it, not to mention having the usual difficulty with ubiquitous American fighter-bombers that circumscribed almost all movement in daylight.42

When General Kniess took over from the provisional XII Corps on 25 March, he inherited only one divisional unit, the weak, almost ineffectual 159th Infantry Division, which was still south of the Main River. He had promise of three others, of which only one, the skeleton of an infantry division sent from the First Army, actually arrived. The other two were the 11th Panzer Division, fast becoming the fire horse of the front now that the 9th Panzer Division had virtually expired at Cologne, and the 6th SS Mountain Division, the latter ordered out of the lines of the LXXXIX Corps just before the U.S. VIII Corps established a bridgehead across the Rhine gorge; but both would become involved with units breaking out of the VIII Corps bridgehead before they could reach General Kniess’s sector.

Responsible for defending the Main River around Frankfurt and Hanau as well as the Rhine opposite Mainz, General Kniess had to focus his attention on the Main River cities, since American armor was already racing toward them from the Oppenheim bridgehead. When a request to OB WEST for permission to withdraw from the Rhine-Main arc drew the usual blunt refusal, Kniess and the Seventh Army commander, General Felber, resorted to what Felber’s chief of staff termed “the well tested method” of withdrawing most of the troops from the arc, leaving a weak shell in place to maintain a semblance of defense.43

By that move Felber and Kniess wrote off the Rhine-Main arc and laid plans for a new defensive line extending north from Frankfurt. Just what troops were left in the arc by nightfall of 27 March neither of them probably knew for sure;

but as of two days before, there had been available to defend almost twenty-five miles of Rhine-Main frontage only three infantry replacement battalions with some engineer support, two artillery battalions, and scattered antiaircraft detachments.

The connivance with Kniess to abandon the Rhine-Main arc was one of General Felber’s last acts as commander of the Seventh Army. Somebody had to pay for the failure—however inevitable—to prevent the American crossing of the Rhine at Oppenheim. That somebody was the army commander. Late on 26 March, Felber relinquished his command to General der Infanterie Hans von Obstfelder, a former interim commander of the First Army. General Kneiss, the LXXXV Corps commander, unable to do anything about either the armored spearheads spreading from Oppenheim or American crossings into the Rhine-Main arc, would follow Felber into Hitler’s doghouse only three days later.

It was a noisy little war the 80th Division staged at Mainz and a few miles away on the Main River before daylight on 28 March, but few, on the American side at least, were hurt. Following a half-hour artillery preparation, men of the 317th Infantry pushed out in assault boats at 0100 from slips and docks of the Mainz waterfront, despite a blaze of German fireworks, mainly small arms and 20-mm. antiaircraft fire. Once the troops were ashore, the Germans mounted two small counterattacks, which like the fire on the river produced more tumult than effect. By the end of the day contingents of a follow-up regiment had cleared Wiesbaden and more than 900 Germans had thrown up their hands; the 317th Infantry had lost not a man killed and only five wounded. One of the more noteworthy events of the day was capture of a warehouse with 4,000 cases of champagne.

The 319th Infantry meanwhile encountered less clamor along the Main opposite Hochheim but took a few more losses—3 men killed, 3 missing, 16 wounded; there too it looked more like theatrics staged by condottieri than genuine battle. By early afternoon the 319th had linked its bridgehead solidly with that of the 317th, and bridge construction was proceeding apace with scarcely a round of German shellfire to interfere.44

The Third Army’s third major Rhine bridgehead came easy. Even those who believed their audacious army commander might have spared his troops a third assault crossing by using one of the bridgeheads previously established could find little quarrel with the outcome.