Chapter 16: Reducing the Ruhr

In the Remagen bridgehead, commanders and troops of the First U.S. Army had known since 19 March that they would be permitted to break out of their bridgehead soon after the 21 Army Group had staged its Rhine crossing. Since 22 March they had known that the breakout attack was to be made on the 25th.1 While tolerating accusations of timidity from news correspondents, the First Army commander, General Hodges, used the wait to advantage by launching limited objective attacks to secure key roads and terrain designed to speed the breakout when the time came.

The 12th Army Group’s orders for the breakout reflected the employment both General Bradley and General Eisenhower had planned almost from the first for the forces in the Remagen bridgehead. Between them, Hodges’ First Army and Patton’s Third were to create a bridgehead ninety-two miles wide, extending from the Sieg River in the north to the Main in the south. From that lodgment the two armies were to drive astride the Lahn River northeast up the Frankfurt–Kassel corridor to Kassel; the First Army was then to turn northward to form the right pincers of a double envelopment of the Ruhr. Since the plan was originally formulated before Patton had achieved any crossing of the Rhine, the orders included provision for part of the First Army to cross the Lahn to help clear the Third Army’s half of the bridgehead.2

Holding the northern rim of the Remagen bridgehead, where the Germans had concentrated their greatest strength in the belief a breakout would be aimed northward toward the Ruhr, General Collins’s VII Corps was occupied through the 24th in turning back the piecemeal armored counterattacks that represented the best that the German tank expert, General Bayerlein, could muster. The corps nevertheless had gained the scheduled line of departure beyond the Ruhr–Frankfurt autobahn whence General Collins was to send his own armor eastward, with the Sieg River affording left flank protection. General Van Fleet’s III Corps in the center of the bridgehead meanwhile juggled its units after relinquishing the southern periphery of the bridgehead to the incoming V Corps, then secured its line of departure east of the autobahn with a night attack that met only crumbling opposition.

General Huebner’s V Corps began its limited objective attacks on 22 March. Aware that the bulk of German armor had shifted to the north, nobody expected resistance in the south to be resolute;

neither was anybody prepared for an impending German collapse. Close by the Rhine a combat command of the 9th Armored Division crossed the Wied River with little difficulty and advanced four miles, while the 2nd Division’s 38th Infantry, alongside the armor, covered more than eight miles in three days to establish a second bridgehead over the Wied four miles deep. Both armor and infantry could readily have advanced even farther with little more effort. Huebner’s V Corps quite clearly could break out at will.

Having anticipated fairly firm resistance at the start of the breakout, General Hodges had planned the First Army’s main effort to be made by Van Fleet’s III Corps, directed southeastward toward the Lahn at Limburg; the V Corps would mop up the east bank of the Rhine down to the Lahn, and there be pinched out by Van Fleet’s advance and shifted into army reserve. The experience of the V Corps in its limited objective attacks changed the plan. To take advantage of the apparent soft spot, Hodges shifted the intercorps boundary to swing the III Corps northeastward short of Limburg, aim Huebner’s V Corps at Limburg, and provide General Huebner with a zone of advance to the northeast for what seemed to be a fast-developing breakout operation.3

The soft spot represented all that was left of General Hitzfeld’s LXVII Corps, southernmost of the three corps under General von Zangen’s Fifteenth Army. That Hitzfeld was down to tattered remains of some five or six infantry divisions and had no armor was known to his superiors, but they could provide no reinforcement without stripping General Bayerlein’s LIII Corps in the north. This Field Marshal Model at Army Group B refused to sanction because of his persisting belief that the breakout attack would be directed northward. Nor would the Fifteenth Army commander approve a shift to the south. Even though Zangen disagreed with Model’s estimate of the direction the breakout would take, he thought it would be directed not to the southeast but east-northeast generally from the center of the bridgehead. Furthermore, as of 24 March, the north wing had already been weakened by orders from Field Marshal Kesselring at OB WEST. In response to General Patton’s surprise crossing of the Rhine at Oppenheim, Kesselring had ordered Army Group B to release the Fifteenth Army’s strongest unit, the 11th Panzer Division, to go to the aid of Army Group G at Oppenheim.4

With the loss of the 11th Panzer Division, there were few reinforcements that either Zangen or Model might have sent in any case. Already Model had drained the Fifth Panzer Army, which was holding the east bank of the Rhine along the face of the Ruhr, to a dangerously low level, and in all of Army Group B there remained only some sixty-five tanks, fifty of which already were fighting along the northern periphery of the bridgehead. Otherwise there was available behind the front only “a confused army of stragglers,” and even though commanders constantly gathered and

committed these men, they did so only to see them “slip away again.”5

Obsessed with the idea that the Americans would strike north, Field Marshal Model based his only hope of preventing a breakout on a strong defense along the natural barrier of the Sieg River and subsequent counterattack into the flank of any northward penetration. General von Zangen counted instead on a hope that when the Americans struck eastward, as he expected, against Püchler’s LXXIV Corps in the center, Bayerlein’s LIII Corps and Hitzfeld’s LXVII Corps could maintain contact with Püchler’s flanks to present a cohesive front long enough to enable Bayerlein’s armor to mount a counterattack from the north.

Somehow managing to ignore bigger American gains southward across the Wied River, Zangen took the limited objective attacks of the U.S. VII and III Corps as proof of his theory that the breakout would be directed east-northeast. When he pressed Army Group B with that presumed evidence, he detected a weakening in Model’s position. The army group commander nevertheless continued to believe that the location of his greatest strength in the north was advisable, since he might counterattack from the north into the flank of either a northward or an eastward drive.

The Breakout Offensive

Even if Model and Zangen were not actually aware of it at the time, they were soon to realize that they were balancing one vain hope against another. Indeed, so weak were the Germans everywhere and so powerful all three corps of the American First Army that neither commander would discern, even after the assault began, that the Allied main thrust was directed not to the east or even northeast but to the southeast toward the Lahn.6

Five infantry and two armored divisions opened the First Army breakout drive before daylight on 25 March. Aiming first for the road center of Altenkirchen, then for crossings of the Dill River more than forty-five miles east of the Rhine, General Collins’s VII Corps used an infantry division, the 78th, to hold that part of the Sieg River line already captured while another, the 1st, protected the corps north flank by attacking eastward along the river. (Map XII) At the same time, the 3rd Armored Division attacked through positions of a third infantry division, the 104th, due east toward Altenkirchen, while the infantry mopped up bypassed resistance.

The Germans at many points made a real fight of it that morning. Reflecting the German concentration near the northern periphery of the bridgehead, the 1st Division and the two northern columns of the armor had the worst of it. There a newly arrived Kampfgruppe of the Panzer Lehr Division—all that was left of the division—and contingents of the 11th Panzer Division that had not yet departed for the Army Group G sector fought with old-time fury; German artillery fire from north of the Sieg was so heavy at some places that it reminded veterans of hectic days in the Siegfried Line. Steep, wooded hills and gorgelike draws and valleys added to the difficulty, but in the end, American power was

simply too overwhelming. In sparkling clear skies, fighter-bombers of the XIX Tactical Air Command time after time struck German formations with particular attention to tanks and assault guns. Supporting artillery fired 632 missions. One Tiger tank and a self-propelled gun fell victim to an American T26 (Pershing), one of the experimental tanks in the 3rd Armored Division. By midday the armor was through the enemy’s main line, and when night came stood twelve miles beyond its line of departure, half the distance to Altenkirchen.7

General Van Fleet’s III Corps in the center, also driving toward eventual crossings of the Dill River but with a southeastward orientation at first in order to help the advance of the V Corps, withheld its armor on the first day. There too resistance was strongest in the north, where the 9th Division brushed against the remnants of the resurrected 9th Panzer Division, the only force of any appreciable power left to General Püchler’s LXXIV Corps. The 9th gained almost four miles through densely wooded, sharply convoluted terrain, while the 99th Division on the right picked up more than five miles. An order from the army commander, General Hodges, to get the 7th Armored Division into the fore the next day arrived moments after General Van Fleet himself had made the same decision and alerted the armor for the move.

In the V Corps, headed for Limburg on the Lahn, the 9th Armored Division continued its thrust down the east bank of the Rhine, coming to a halt only after an advance of over eight miles to the Rhine town of Vallendar, a few miles short of Koblenz. From there good roads led almost due east to Limburg. The 2nd Division’s 23rd Infantry meanwhile carried the advance on the armor’s left, losing two men killed and fifteen wounded in exchange for gains of more than five miles. The promise of the earlier limited objective attacks in this sector clearly was to be fulfilled.

During the course of this advance, soon after midday, the 23rd Infantry’s Company G gained a crossing of the little Sayn River, only to face a clifflike stretch of wooded high ground beyond. Tired from the morning’s fight, hot in a wool uniform baked by a brilliant spring sun, the company commander deplored the thought of walking with heavy equipment up the winding road ahead. “Climb on the tanks,” he ordered his men. They responded by enthusiastically clambering aboard two platoons of attached medium tanks. You did not ride, the men knew, until the resistance had begun to collapse.

Events the next morning, 26 March, proved the men and their company commander right, to the immense pleasure of the army commander, General Hodges, and his guests of the day, Generals Eisenhower and Bradley.8 The day before, the Third Army’s 4th Armored Division had broken out of the Oppenheim bridgehead and seized bridges over the Main River at Hanau and Aschaffenburg, and the VIII Corps had begun jumping the Rhine gorge at Boppard. Before daylight on the 26th, the Seventh Army had begun to cross the Rhine near Worms, and British and American units north of the Ruhr were straining to achieve a breakout. With those developments

as a backdrop, Hodges was elated when news of his three-pronged armored advance began to come in.

Despite an early morning counterattack by infantry supported by assault guns, apparently designed to allow remnants of the Panzer Lehr Division to pull back behind the Sieg River, the 3rd Armored Division in General Collins’s VII Corps raced eastward in great bounds. With a motorized combat team of the 104th Division attached, the armor bypassed Altenkirchen, leaving that road center for reserves to clear. After taking high ground outside Hachenburg, half the distance from the original bridgehead to the objectives on the Dill River, it coiled for the night. At those points where the Germans elected to make a stand, mainly along the north flank, planes of the 48th Fighter-Bomber Group in close coordination with the armor swooped down to take out tanks and self-propelled guns. In late afternoon such organized units as still opposed the advance began to peel back across the Sieg.

In the III Corps the time proved fully propitious for committing armor. After an early delay caused by craters blown in the roads and by mines, demolished bridges, and a mix-up with the V Corps over running rights on the autobahn, the 7th Armored Division broke loose to roam almost at will southeastward toward Weilburg on the Lahn River. By road measurement some units of the division advanced over thirty miles. When night came the 7th Armored Division held high ground overlooking Weilburg, while infantry of the 9th and 99th Divisions, advancing on attached tanks and tank destroyers and by shuttle in trucks borrowed from artillery antiaircraft units, struggled to keep up. The III Corps on 26 March captured 17,482 Germans, more than 12,500 taken by the armored division. Several hundred of these prisoners represented the rear echelon of the 11th Panzer Division, caught as they moved diagonally across the front en route to commitment with Army Group G.

The story was much the same with the 9th Armored Division of the V Corps. Once calls to higher headquarters straightened out the brief run-in with the 7th Armored Division on the autobahn, the 9th Armored drove eastward toward Limburg against almost no opposition. Although remnants of General Hitzfeld’s LXVII Corps fled ahead of the armor, in most cases their flight served merely to augment the prisoners of the adjacent III Corps.

In midafternoon Combat Command B found a bridge intact over the Lahn River and got four tanks across before the Germans could ignite the prepared demolition and blow the span. Dismounted armored infantrymen then made their way across on the rubble and systematically began to clear Limburg of scattered small arms resistance, augmented occasionally by fire from Panzerfausts. Although most of the town was in hand soon after dark, the division commander, General Leonard, postponed a continuation of the drive beyond the river to cut in behind those Germans opposing the Third Army’s VIII Corps until he could get a treadway bridge built across the Lahn.

Collapse of the LXXXIX Corps

On 27 March, as General Leonard prepared to send his reserve combat command

southeastward along the autobahn, the German LXXXIX Corps, having fought vainly to prevent crossings of the Rhine gorge, had fallen back from the Rhine to a line not quite midway between the river and the autobahn. This was the corps, commanded by General Höhne, that only shortly before the American VIII Corps attacked had been transferred to Army Group B’s Fifteenth Army; in the confusion of events, no contact had ever been established with the army headquarters and little with headquarters of the army group. This was the corps, too, that had lost the 6th SS Mountain Division at the order of Field Marshal Kesselring only hours before the VIII Corps attacked. Like the incoming 11th Panzer Division, the mountain division, its 6,000 men representing a still creditable fighting unit, was supposed to be used to counterattack Patton’s crossing at Oppenheim.9

Receiving the news of American armor racing toward the Lahn, Kesselring had quickly reconsidered and reassigned the mountain division to the LXXXIX Corps to be committed to hold the line of the Lahn around Limburg. Because the division had no gasoline, the men had to march on foot, arriving at the southern edge of Limburg late on the 26th only after American armor had already entered. With additional units of the division that arrived during the night, the commander, Generalmajor Karl Brenner, built up a line facing north astride the autobahn.10

It was too little too late. In an attack that started shortly after midday on 27 March, the 9th Armored Division’s CCR sliced quickly through the hasty defenses on the autobahn and reached its objective of Idstein, fifteen miles to the southeast, before dark.

Pressed hard from the west by the oncoming VIII Corps and faced with this sizable American force to his rear, the commander of the LXXXIX Corps, General Höhne, finally managed in late afternoon to establish radio contact with Field Marshal Kesselring at OB WEST. To Höhne’s request that he be allowed to withdraw east of the autobahn, Kesselring gave a decisive no.

It made little difference. Having already lost communications with whatever remained of the 6th SS Mountain Division, Höhne during the morning learned from his one surviving division, the 276th Infantry Division, that collapse was imminent. Höhne took it upon himself to order withdrawal. His own headquarters was under hostile fire from reconnaissance cars and infantry when, with a group of some thirty of his staff, he headed east. “Corps HQ,” he was to note later in something of an understatement, “was no longer in a position to exercise effective command.”11

What was left of General Brenner’s 6th SS Mountain Division—some 2,000 men—meanwhile continued to hold out west of the autobahn and from time to time during the next two days set up roadblocks on the autobahn, even after forward units of the VIII Corps had moved well to the east and the 9th Armored’s CCR had gone back north of the Lahn. During the night of 30 March

Brenner and his force would begin an attempt to infiltrate back to German lines, an odyssey destined to end three days later, on 2 April, when the remnants, including General Brenner, were finally rounded up.

During the course of their peregrinations, the SS troops captured an American field hospital, where they obtained critically needed gasoline and transportation. Although they treated the hospital personnel correctly, a rumor that they had murdered the staff and raped the nurses accounted, General Patton reported later, for the fervor with which American troops hunted them down. Some 500 were killed before a last 800 surrendered.12

The collapse of the LXXXIX Corps severed the last tenuous link between Army Groups B and G, and there was nothing the Germans could do about it. The only reserve even remotely available, the remains of the 11th Panzer Division, would be swept up in the general American advance and ripped to pieces with no chance of mounting a counterattack. Only the division commander and the reconnaissance battalion even reached their destination with Army Group G.13

A Turn to the North

Even without that collapse, the two army groups soon would have been separated, for the American First Army’s breakthrough of the positions of the Fifteenth Army opposite the Remagen bridgehead on 26 March was total. In the process the army commander, General von Zangen, lost contact with almost everybody but his own staff and the headquarters of one of his corps, General Püchler’s LXXIV Corps, which had been utterly crushed by the breakout offensive. Unable to reach the Fifteenth Army headquarters by radio or telephone, Field Marshal Model at Army Group B was fast coming to the conclusion that Zangen had been captured.14

Since he was unable to contact Zangen, Model dealt directly with the commander of the LIII Corps, General Bayerlein, ordering him to pull back behind the Sieg, relinquish the line of the Sieg to contingents of the Fifth Panzer Army, and prepare for a counterattack into the American flank in the direction of Limburg. To Bayerlein, knowing how weak were the remnants of his corps, a counterattack seemed “impossible and entirely hopeless ... insane,” but he dutifully began preparations.15

The pace of the American drive on this same day, 27 March, supplied any affirmation Bayerlein might have needed that counterattack would be in vain. While occupied with the thrust south of the Lahn River, the 9th Armored Division of the V Corps made no further eastward advance. In the VII Corps, on the north wing of the First Army, the 3rd Armored Division gained an impressive twenty-two miles to jump the Dill River in two places. At the same time, the 7th Armored Division of the III Corps also crossed the Dill, seizing four bridges intact. Fog in morning and afternoon and a low overcast the rest of the day prevented

air support, but the armored columns had little need of it. They were roaming the enemy’s rear areas, everywhere catching the Germans by surprise, and finding them unprepared to defend with more than an occasional roadblock covered by a smattering of small arms fire or perhaps a Panzerfaust or a lone self-propelled gun that could be quickly put to flight. Only on the First Army left flank, where the 1st Division continued to sweep up to the south bank of the Sieg, was there any real resistance, and it was more a reminder that there were sizable German forces beyond the Sieg covering the Ruhr than it was an immediate problem.

The next day, 28 March, the armor of the VII Corps again set the pace, driving another twenty-one miles and seizing the little cultural center of Marburg on the upper reaches of the Lahn. The town’s thirteenth century cathedral and its university, founded in 1527, showed no scar from twentieth century battle. En route, the 3rd Armored Division overran several German hospitals with more than 5,600 soldier patients, took another 10,000 prisoners, so many they could not all be processed during the day, and sent scores of liberated foreign laborers coursing happily toward the west. The V Corps meanwhile took a day to reorganize, while the armor of the III Corps kept almost abreast, advancing thirteen miles, capturing Giessen, and dispersing a fairly persistent delaying force before seizing crossings over the Lahn.

To the 12th Army Group commander, General Bradley, the time had arrived to begin the great wheel to the north designed to join with the Ninth Army to encircle the Ruhr. Redrawing army boundaries, Bradley turned the First Army northward toward Paderborn, leaving the Third Army oriented northeast on Kassel to protect the First Army right flank; anticipating a rapid drive, he rejected a proposal from the First Allied Airborne Army for an airborne attack to seize Kassel. (Map XIII) The new Fifteenth Army was to take over defense of the Rhine’s west bank so that all the First Army divisions could cross the river to man the ever-lengthening front facing the Ruhr.16

Within the First Army, General Collins’s VII Corps from its position on the inside of the wheel was the obvious choice for making the main thrust to Paderborn, despite the continuing sensitive reaction of the Germans on the left flank. The other two corps were to continue northeastward to protect Collins’s right flank.

A task force, commanded by Lt. Col. Walter B. Richardson and built around a medium tank battalion that included three of the new Pershing tanks, led the 3rd Armored Division advance on 29 March. The orders: “Just go like hell!”17 Although the objective—Paderborn—lay more than sixty miles away, Richardson was determined to make it before calling a halt.

Crashing through some roadblocks, bypassing others, occasionally shooting up the landscape, everywhere encountering dismayed Germans who obviously had no inkling that American troops were near, Task Force Richardson plunged rapidly forward, hardly missing the tactical air support that a hazy, overcast day denied. Follow-up units, supply troops, liaison

officers, and messengers probably did more actual fighting than did the leading force, since German stragglers and bypassed groups often recovered from their first bewilderment to fight back. The longest delay for Richardson’s column developed in Brilon, twenty-five miles short of Paderborn, where, as Richardson and an advance guard pushed on, someone among the tank crews discovered a warehouse filled with champagne. When the tanks finally caught up with their commander, the actions of many of the crewmen provided disconcerting evidence of their find.

Task Force Richardson at last halted around midnight fifteen miles short of Paderborn. The decision to stop was based on about equal parts of concern for exhausted troops and a report that tanks from an SS panzer replacement training center were in the Sennelager maneuver area near Paderborn. Although still short of the objective, Richardson and his men had covered forty-five miles at a cost of no casualty more severe than the headaches some men suffered from too much champagne.

The next day, 30 March, the complexion of the battle abruptly changed. Hardly had Task Force Richardson resumed the advance when the point bumped into a defensive line hastily manned during the night by students from an SS panzer reconnaissance training battalion and an SS tank training and replacement regiment, banded together with support from an SS tank replacement battalion of approximately sixty Tiger and Panther tanks into a unit named SS Ersatzbrigade Westfalen. By midafternoon Richardson’s men had forced their way into a town only six miles short of Paderborn. There they fought the rest of the day and much of the night against at least two tanks and more than 200 Germans, most of whom employed Panzerfaust antitank weapons with suicidal fervor.

Coming up on Richardson’s right, another task force commanded by Col. John C. Welborn tried to bypass the town by a secondary road. Dusk was approaching when small arms fire from either side of the road and round after round from tanks and self-propelled guns cut the column. One of those who dived for cover in a ditch was the 3rd Armored Division commander, General Rose, on his way forward to supervise the final assault on Paderborn with his aide and a small party traveling in jeeps and an armored car.

Hardly had Rose finished sending a radio message to his command post to dispatch another task force to take out this nest of opposition when four German tanks appeared, coming up the road from the rear. In the early evening darkness, Rose and his party tried to escape by racing past the tanks, but one of the tanks suddenly swerved, pinning Rose’s jeep against a tree. A German standing in the turret motioned with a burp gun. Rose, his aide, Maj. Robert Bellinger, and his driver, Tech. 5 Glen H. Shaunce, dismounted. They had no choice but to surrender.

Standing in front of the tank, Bellinger and Shaunce unbuckled their pistol belts and let them drop. Rose started either to do the same or to remove his pistol from its holster. The German in the turret quickly swung his burp gun, and a spout of flame split the darkness. Rose pitched forward. Bellinger and Shaunce dived for a ditch and, in the

confusion, got away. Maurice Rose, esteemed by his superiors as one of the best division commanders in the theater, was dead.18

As the cordon designed to encircle all of Army Group B rapidly took shape, the army group commander, Field Marshal Model, had no stomach for a last-ditch stand among the bomb-shattered factories, mines, and cities of the Ruhr. Summarizing the situation for OB WEST on the 29th, Model noted that he had lost contact with headquarters of the Fifteenth Army and that his only reserve consisted of headquarters of the LIII Corps (Bayerlein), two mobile Kampfgruppen (the Panzer Lehr and 3rd Panzer Grenadier Divisions), and a partially rebuilt infantry division, the 176th. With the forces and supplies remaining, Model reckoned, he might be able to hold out in the Ruhr, even though encircled, until mid-April at the latest; but if a decisive attack were not mounted from the outside by that time, the army group likely would be destroyed.19

Model clearly wanted to withdraw immediately from the Ruhr, saving his army group to fight again in central Germany. To assist a withdrawal, he urged an immediate attack by Bayerlein’s LIII Corps from the vicinity of Winterberg, in densely wooded hill country fourteen miles south of Brilon, eastward to the Eder-See, a reservoir approximately midway between Winterberg and Kassel. To complement the thrust, he hoped for a converging attack from Kassel to be launched by troops of the Fifteenth Army, which he presumed had fallen back on Kassel. The two attacks, Model hoped, might cut off the American armored columns even then closing in on Paderborn and prevent encirclement long enough for Army Group B to pull out.

Kesselring’s reply came that night. Attack, yes; withdraw, no. Only the day before, Hitler had reiterated his long-standing order to authorize no withdrawal on pain of death. Army Group B would have to stand in the Ruhr and—Model well might have predicted—die there as well.

Having already alerted General Bayerlein and subordinate units to the possibility of an attack east from Winterberg, Model dutifully continued with the arguments. In the absence of the Fifteenth Army commander, he designated the army group artillery commander, General der Artillerie Karl Thoholte, to command the attack and to create a defensive line from Siegen to Brilon, the line to be manned by Luftwaffe units, alarm and construction troops, and Volkssturm. Recognizing that the only chance of success lay in striking before the Americans could consolidate behind their armor, Model ordered that the attack begin with whatever units had arrived by the evening of 30 March.

The Fifteenth Army commander, General von Zangen, though out of contact with headquarters of the army group, had in the meantime been trying to erect some kind of defensive barrier across the Frankfurt–Kassel corridor. He still had communications with remnants of Püchler’s LXXIV Corps and had established liaison with a corps headquarters that had been attached to the Fifteenth

Army sans combat troops soon after the American breakthrough, the LXVI Corps under Generalleutnant Hermann Floerke.20

Zangen ordered both corps to collect stragglers (the roads were jammed with them), security troops, ambulatory hospital patients, whatever, to build a line across the corridor near Giessen; when American armor overran that position before any barrier could be raised, he ordered the line built south of Marburg. Again the American columns overran the position.

Hardly had Zangen dutifully designated a third line, this time along the Lahn River north of Marburg, when word reached him that American armor already had jumped the Lahn and bypassed his headquarters town of Biedenkopf on both east and west. (This was on 29 March, the day of the 3rd Armored Division’s explosive advance toward Paderborn behind Task Force Richardson.) The third line obviously had been compromised even before Zangen designated it, and his headquarters was cut off not only from the army group but also from the two remaining corps commands.

Only a step ahead of American tanks, Zangen herded his headquarters staff and attached units out of Biedenkopf into a nearby forest. There, as night came, he and his men hid, warily eyeing tanks and vehicles of the 3rd Armored Division driving past.

When sentries reported large gaps in the American column, Zangen seized upon a daring scheme to escape and make his way back into the Ruhr. Organizing his men and more than a hundred remaining vehicles into small groups, he ordered them to thread their way in the darkness into the gaps, march with the Americans for several miles to a road junction, then turn to the west as the Americans continued northward. Zangen and almost his entire force escaped. Only one truckload of troops and a motorcyclist failed. They made the mistake of calling out in their native tongue to the lead vehicle in an American serial that came up behind them.

The Thrust From Winterberg

In pinning much of their hope for a successful attack from Winterberg on striking before American infantry could consolidate behind the armored spearheads, German commanders failed to give proper consideration to the speed of the infantry units. Conscious of insufficient infantry strength in the old-style “heavy” armored divisions, of which the 3rd Armored was one, General Rose and the VII Corps commander, General Collins, had long practiced attaching an entire infantry regiment to the armor in breakthrough situations. As the 3rd Armored had rolled toward Paderborn, the 104th Division’s 414th Infantry had gone along, some men mounted on the armored division’s tanks, tank destroyers, and half-tracks, others in the regiment’s own vehicles. These “doughs” (short for doughboys), as the tank crewmen called them, were not to mop up resistance but to help the tankers if the going got sticky.

Close behind the armor and its attached infantry came the rest of the

104th Division, mounted on its own vehicles, those of its artillery and attached antiaircraft battalion, trucks furnished by the First Army quartermaster, and the battalions of tanks and tank destroyers that by that stage of the war had for so long been constantly attached that the division looked upon them almost as permanent fixtures. Motorized and supported in this manner, an infantry division could move almost with the speed of an armored division, particularly when following in the wake of armor. Thus the infantry was quickly available to mop up and to provide depth to the armored spearheads.

To the Germans at Winterberg, chances of success appeared brighter because a distance of only about fifteen miles separated Winterberg from their objective, the elongated Eder-See, a narrow corridor through which apparently only forward elements of one armored division had passed. They were reckoning without the 104th Division. They were reckoning, too, without the speed of the other two corps of the First Army.

By nightfall of 30 March, the 7th Armored Division of General Van Fleet’s III Corps had come up close along the right flank of the VII Corps to seize a dam at the east end of the Eder-See and several bridges over lower reaches of the reservoir and of the river downstream from the dam.21 This the troops of the III Corps had accomplished despite meeting a fresh German unit, the 166th Infantry Division, moved from Denmark in accord with Hitler’s earlier promise. Meanwhile, the 9th Armored Division of General Huebner’s V Corps also reached the Eder River downstream from the dam and forced a crossing. Infantry divisions followed the armor closely in both corps, providing strength close at hand either to knife into the flank of any complementing German thrust that might be launched toward the Eder-See from Kassel or to furnish reinforcement for the VII Corps.

In their hope for a complementary thrust from Kassel, the Germans were doomed to disappointment. There simply was no German unit at Kassel strong enough to launch an attack. For lack of coordination, the incoming 166th Infantry Division, which might have formed the nucleus for an attack, had already been committed futilely two days earlier and cut up in an engagement with the U.S. III Corps. Although Field Marshal Model had counted on the SS Ersatzbrigade Westfalen to assist a drive from Kassel, he had not known how locked in combat this makeshift force was with the 3rd Armored Division spearheads just outside Paderborn.

For the Americans, rumor after rumor passed on by German stragglers and civilians during the 30th had pointed to a concentration of German tanks and infantry at Winterberg, massing for a breakout attempt that night. To guard against it, the 104th Division commander, General Allen, ordered his regiments to occupy key towns and road junctions along the corps left flank facing Winterberg. He also sent a mobile task force racing through the night over roads bypassing Winterberg to defend Brilon, which, aside from having provided

champagne for Task Force Richardson, afforded a blocking position astride a major highway leading from the Ruhr across the 3rd Armored Division’s rear to Kassel. The First Army commander, General Hodges, ordered Van Fleet’s III Corps to release its leading infantry division, the 9th, to go to the VII Corps the next day.

For the start of the attack from Winterberg on the night of 30 March, only two Kampfgruppen had yet arrived, each representing a mixed battalion of infantry and combat engineers, plus twelve tanks of the Panzer Lehr Division, a few assault guns, but no artillery. The LIII Corps commander, General Bayerlein, sent these battalions with guides from the local forestry service down forest trails leading southeast to cut a highway connecting the towns of Hallenberg and Medebach. From this highway, westernmost of three routes serving the 3rd Armored Division, Bayerlein intended to continue the attack to the Eder-See once the rest of his troops, including the 176th Infantry Division, arrived.22

The columns on the forest trails got moving at midnight. As dawn approached, both columns cut the Hallenberg–Medebach highway with no difficulty, but a battalion of the 415th Infantry posted in each of the two towns rapidly restored the route. The hottest fight, meanwhile, developed at a village midway between the two towns, where sixteen men from Company A, 414th Infantry, had bedded down for the night while crews of two 3rd Armored Division tanks they had been riding awaited a maintenance vehicle. Also on hand, awaiting maintenance, was a crippled self-propelled artillery piece.

One of the infantrymen, S. Sgt. Cris Cullen, recalled the start of the fight:

The first thing I heard that morning was one of the Polish slave laborers running around yelling, “Panzer! Panzer!” Then as I started to go back to sleep, mumbling to myself about that ‘damn crazy Polack,’ I heard the unmistakable sound of a German machine gun. That fixed the sleep.

While I was cramming on my boots, one of our men came in for ammo and I asked him what was going on. ‘Plenty,’ he said. ‘There’s a Kraut tank coming down the street.’ People exaggerate when they are excited. I would go look for myself before I got excited.

I got excited. About forty yards away and coming slowly forward was a German tank with a gun on it that looked as large as a telephone pole.23

Before Sergeant Cullen and the others could bring rifle and bazooka fire to bear from the houses, the German tank knocked out the unmanned artillery piece; but as the tank commander raised his head from his turret to survey his victim, one of the riflemen cut him down. A fusillade of small arms fire from the houses drove the accompanying German infantry to flight. The tank followed.

Through the rest of the day, the Germans made occasional forays against some points along the highway, but they had not the strength to take the 415th Infantry’s sally ports of Hallenberg and Medebach, which would have to be occupied if any cut of the highway was to be sustained. The Fifteenth Army commander, General von Zangen, who assumed over-all command following his

escape from encirclement, opted to delay hitting the two towns until additional troops arrived.

The thrust from Winterberg had thus far been little more than a nuisance raid.

Breakthrough North of the Ruhr

Even as the Germans in the Ruhr first prepared to launch the weak beginning of their attempt to force a corridor to the outside, their plight was about to be compounded by developments along the northern edge of the Ruhr. There, on 28 March, troops of the XVIII Airborne Corps had scored a rapid gain to Haltern, on the north bank of the Lippe River more than twenty-five miles east of the Rhine, opening the way for the breakthrough that the 30th Division and the 8th Armored Division of General Anderson’s XVI Corps had sought in vain south of the Lippe. On the same date Field Marshal Montgomery had announced his new policy, to be put into effect on the 31st, for use of the Rhine bridges at Wesel and the roadnet north of the Lippe that insured a way for General Simpson to bring more of his powerful Ninth Army to bear.

On the 29th Simpson published his plan for the breakout drive to the east. While Anderson’s XVI Corps swung southeastward to build up along the Rhein–Herne Canal on the northern fringe of the Ruhr, General McLain’s XIX Corps, moving north of the Lippe River, was to take over the main effort. With two armored and three infantry divisions, McLain’s corps was to drive first to Hamm, at the northeastern tip of the Ruhr, then go on to link with the First Army at Paderborn. General Gillem’s XIII Corps, meanwhile, as maneuver room developed and as the Wesel bridges passed to the Ninth Army, also was to move north of the Lippe and drive northeastward on Muenster, twenty miles north of Hamm. In the process, the XVIII Airborne Corps was to be relieved, British units within the corps passing to the British Second Army and General Gillem assuming control of the U.S. 17th Airborne Division.24

Alerted in advance to the orders, a combat command of the 2nd Armored Division, reinforced by an attached infantry regiment, began to cross the Rhine into the crowded rear areas of the XVI Corps early on 28 March. From there the armor was to cross the Lippe, bypassing the bottleneck of Wesel, and start its eastward thrust even before the Wesel bridges passed to the Ninth Army’s control.

Although the rapid advance of the XVIII Airborne Corps and pending commitment of the XIX Corps north of the Lippe at this point obviated the necessity of a breakthrough south of the river, the division that earlier had been assigned the goal, the 8th Armored, continued to attack. The armor was to take the long-sought objective alongside the Lippe, the town of Dorsten, needed as a bridge site to serve the XIX Corps, then was to continue eastward to cross upper reaches of the Lippe. Both the 8th Armored and the 30th Divisions then were to pass from control of the XVI Corps to that of the XIX Corps.

Renewing the attack on 29 March, the 8th Armored Division found the enemy’s 116th Panzer Division, which as part of General Lüttwitz’s XLVII Panzer Corps

had thwarted a breakout from the Rhine bridgehead, still making a fight of it. By nightfall the American armor claimed Dorsten, but it had been a plodding fight against an enemy helped by marshy ground, woods, and deadly nests of big antiaircraft guns in concrete emplacements. Given the wooded nature of the terrain east of Dorsten, there was no evidence but that the same kind of slow, dogged advance might be in the offing for days.

The story was far different north of the Lippe. There reconnaissance forces of the 2nd Armored Division had moved out of Haltern before midnight on the 29th with every indication of a swift sweep eastward. Not long after daylight the next morning, 30 March, the main columns reached the Dortmund–Ems Canal, paused while engineers built bridges, then resumed the advance in late afternoon. All through the night of the 30th and the next day the armor rolled, while the 83rd Division, mounted on trucks belonging to the corps artillery, followed closely. In the process the tanks cut two major rail lines leading north and northeast from Hamm, leaving only one railroad open to the Germans in the Ruhr. In late afternoon of the 31st the armor also cut the Ruhr–Berlin autobahn near Beckum, northeast of Hamm, just under forty miles beyond the original line of departure.

To the top German commanders north of the Ruhr—Blaskowitz of Army Group H and Blumentritt, the new commander of the First Parachute Army—the American breakthrough north of the Lippe mocked the standfast orders that Hitler and Kesselring had so recently issued when denying Blaskowitz’s appeal to withdraw, first to the Teutoburger Wald, then behind the Weser River.25 So swift and deep was the American thrust, irreparably splitting the First Parachute Army down the middle, that the end result was bound to be much the same as the withdrawal Blaskowitz and Blumentritt had recommended.

With the means at hand, no hope existed of counterattacking southward into the American flank, as Hitler’s emissary, General Student, would himself discover upon his arrival. Those contingents of the parachute army north of the breakthrough had no choice but to fall back toward the Teutoburger Wald—indeed, they would be hard put to keep ahead of American and British troops. All communications with the First Parachute Army and Army Group H having been severed, Lüttwitz’s XLVII Panzer Corps and Abraham’s LXIII Corps south of the breakthrough appealed for orders to Field Marshal Model at Army Group B. Just as Blaskowitz earlier had urged, Model told both corps to form a new line facing north behind the Rhein–Herne Canal and, farther east, behind the Lippe River. These two corps, brigaded under Lüttwitz’s headquarters as Gruppe von Lüttwitz, then would comprise the defense for the northern face of the Ruhr.26

For a day or so Field Marshal Kesselring would fuss and fret over Model’s presumption in absorbing the two corps, though he would inevitably be forced to accept it. Thus, by the first day of April, the lineup of units around the

perimeter of the Ruhr was basically complete: in the north and turning the northeastern corner short of Lippstadt, some twenty miles up the Lippe from Hamm, Gruppe von Lüttwitz; beginning at the Moehne Reservoir on the upper reaches of the Ruhr River, Zangen’s Fifteenth Army, which faced east and southeast, to a point on the Sieg River near Siegen; facing south along the Sieg and west along the Rhine, Harpe’s Fifth Panzer Army. As this lineup took shape, the time left before the Germans in the Ruhr would be fully encircled could be measured in hours.

Late on 31 March, as the Ninth Army’s 2nd Armored Division was cutting the autobahn near Beckum, the army commander, General Simpson, received a troubled telephone call. It was from Joe Collins, commander of the First Army’s VII Corps. His 3rd Armored Division, Collins said, had stirred up a fury of opposition from fanatic SS troops near Paderborn. It might take days to eliminate the resistance and continue north to the army group boundary to establish contact with the Ninth Army, thereby sealing the circle around the Ruhr. Furthermore, he went on, the Germans inside the pocket already had begun to strike at the rear of the 3rd Armored Division in what prisoners reported was the beginning of a major effort to break out of the Ruhr.

Collins asked Simpson to turn a combat command of his 2nd Armored Division southeast toward Lippstadt, midway between Beckum and Paderborn. Collins, for his part, would divert a force from the 3rd Armored to meet the combat command halfway.

General Simpson promptly ordered a combat command of the 2nd Armored Division to turn southeast toward Lippstadt. Before daylight the next morning, 1 April—Easter Sunday—a task force commanded by Lt. Col. Matthew W. Kane, including a battalion of 3rd Armored tanks transporting “doughs” from the 414th Infantry, turned from the fight at Paderborn toward Lippstadt. Neither force encountered serious opposition; fire came mainly from small arms, though there were a few rounds from flak guns, whose dispirited crews quickly fled or surrendered. By noon pilots of artillery liaison planes from the 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions could see leading ground troops of both divisions. About 1300 the two columns came together, amid cheers and ribald jokes, on the eastern fringe of Lippstadt.

The Ruhr industrial area was encompassed. Trapped in a pocket measuring some 30 miles by 75 miles were the headquarters and supporting troops of Army Group B, all of the Fifth Panzer Army, the bulk of the Fifteenth Army, and two corps of the First Parachute Army, a total of 7 corps and 19 divisions. American intelligence officers estimated that the force consisted of some 150,000 men. They were, events soon would disclose, far too conservative.

Making Motions at Breakout

Although the trap was closed the German command, with commendable bravado but little else, was making bellicose but empty motions and issuing pretty but illusory orders aimed at opening a corridor into the Ruhr Pocket. While General von Zangen’s Fifteenth Army, using Bayerlein’s LIII Corps, renewed its attack from Winterberg, Field Marshal Kesselring tried to mobilize a force near

Kassel strong enough to push a way through from the east.27

To command the attack, Hitler sanctioned using headquarters of the Eleventh Army, a staff that in happier times had compiled a good record on the Russian front. Only recently reconstituted, the staff was to be subordinated directly to OB WEST. The commander was to be General Hitzfeld, heretofore commander of the Fifteenth Army’s LXVII Corps, which had escaped entrapment in the Ruhr.

General Hitzfeld was to have his own LXVII Corps, General Floerke’s LXVI Corps, and a provisional corps headquarters created from the staff of the local Wehrkreis. This force looked solid enough on paper; in reality, it signified little. Its strongest component was to be the SS Ersatzbrigade Westfalen, which late on 1 April finally relinquished Paderborn to the American 3rd Armored Division and fell back with possibly as many as forty tanks and assault guns still fit to fight. There were in addition two surviving battalions of the ill-starred 166th Infantry Division, stragglers, Volkssturm, hospital returnees, and about twenty tanks from a factory at Kassel. With those odds and ends Hitzfeld was not only to break into the Ruhr but was also to build a solid line against further eastward advance along the Weser River.

Hitzfeld’s force was only beginning to assemble when, before daylight on 1 April, the Germans at Winterberg renewed their heretofore feeble attempts to push eastward to the Eder-See.28 Although the 176th Infantry Division still had not arrived, enough troops and artillery and a few tanks of the 3rd Panzer Grenadier and Panzer Lehr Divisions were on hand to send a column against each of the two key towns, Medebach and Hallenberg.

About 150 panzer grenadiers with four tanks struck Medebach before dawn on 1 April. In the first flush of the attack, they gained a toehold in the western fringes of the town, but a battalion of the 104th Division’s 415th Infantry held fast. Organic 57-mm. antitank guns knocked out one German tank; a bazooka accounted for another. The other two and those panzer grenadiers not killed or captured hastily retreated.

At Hallenberg the Panzer Lehr attack never got going; it ran head on into an attack by the 9th Division, hurriedly transferred from the adjacent III Corps to strike the supected base of the German breakout offensive. Men of the 39th Infantry, attacking up the road from Hallenberg toward Winterberg, never even knew a German attack was in progress. The drive, the regiment reported, encountered “moderate resistance.” “Here,” the LIII Corps commander, Bayerlein, was to note later, “the enemy seemed to form a point of main effort.”29

With arrival of part of the 176th Division later in the day, the Germans at Winterberg launched another thrust early on 2 April. While the Panzer Lehr to the southeast and the 176th to the northeast held the shoulders, the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division was to make the main effort, again through Medebach.

Medebach was not to be had. Although the panzer grenadiers this time

infiltrated around the town in the darkness to hit from both east and west, the men of the 415th Infantry again held fast, killing 30 Germans and capturing 61. The defending battalion itself lost 2 dead and 2 wounded. Part of the force infiltrating around the town machine gunned an artillery battery supporting the 415th but melted away when the artillerymen hastily formed a skirmish line and returned the fire.

The German attack beaten back by midmorning, the 104th Division commander, General Allen, ordered the 415th Infantry to make a counterthrust, driving from Medebach and along another road from the northeast toward Winterberg. When night came, men of the 415th were locked in close combat with remnants of the German force in woods several miles west of Medebach.

The Panzer Lehr Division, meanwhile, had failed to do its job of holding the southern shoulder of the German attack. Despite steep hillsides and dense woods, a battalion of the 9th Division’s 39th Infantry pushed into Winterberg just as day was breaking. In the town itself, the Germans offered no fight in deference to several hospitals in the town and to hordes of refugees seeking cover there.30 The most severe fighting occurred in midmorning at a village southwest of Winterberg where infantry of the Panzer Lehr supported by a few self-propelled guns launched what men of the 9th Division’s 60th Infantry took to be a counterattack. The Germans held the village briefly until a battalion of the 39th Infantry came in on their rear from Winterberg.

Farther north, General Collins had moved the 1st Division to clean out woods and villages close behind the positions of the 3rd Armored Division.31 With three infantry divisions thus in place to hold that part of the corps left flank, any danger that a thrust in no greater strength than that launched by Bayerlein’s LIII Corps might succeed had passed. Bayerlein’s weak force would be hard put even to hold defensive positions on wooded hills west of Winterberg.

As for the Eleventh Army and the proposed strike from the vicinity of Kassel, it had become apparent early to the army commander, General Hitzfeld, that the entire scheme had been from the first no more than a fantasy. The Americans were already exerting pressure toward the east and obviously soon would break into the open and jump the Weser. Hitzfeld had scarcely enough men to irritate such a thrust when it came, let alone launch an attack.32

By radio Hitzfeld appealed on 3 April to Field Marshal Kesselring to cancel the attack. Kesselring waited to reply until the next day when he could visit Hitzfeld’s headquarters. A firsthand look then made the situation all too clear. Kesselring canceled the order but, probably for the record, directed a substitute

thrust southward into spearheads of the U.S. Third Army. Like the thrust to relieve the Ruhr Pocket, that one too, Kesselring and Hitzfeld both must have known, would never come off in any appreciable strength.

The Ruhr Pocket

Upon the collapse of Bayerlein’s counterattack from Winterberg, Field Marshal Model and his staff inside the Ruhr Pocket retained little hope of assistance from the outside.33 The Eleventh Army they deemed too weak to break through. Because the Twelfth Army was not even to be activated until 2 April, they saw no chance of help from that quarter, no matter what faith Hitler still might have in it. Their only possibility of escape, most believed, was to break out southward, where the Americans seemed to be weakest. Even that depended on gaining a respite from the fighting, which would come only if the Americans, while concentrating their power in the continuing drive to the east, should try to contain the pocket rather than to erase it.

Under this condition, plans for another try at breakout never passed the talking stage. Even while completing the encirclement of the Ruhr, American commanders, rich in resources, had been adjusting their units in order to move on to the east and at the same time reduce the Ruhr.

By 1 April when the pincers around the pocket snapped shut, Simpson’s Ninth Army had one corps already engaged, in effect, in reducing the pocket. Having wheeled southeastward against the Ruhr after establishing a Rhine bridgehead for the Ninth Army, Anderson’s XVI Corps had three infantry divisions in the line. Two were fighting among the houses, apartments, shops, and factories on the fringe of the Ruhr along the north bank of the Rhein–Herne Canal.

On 2 April, after representatives of the First and Ninth Armies established the Ruhr River as the dividing line between them, General Simpson also gave General McLain’s XIX Corps a role in the reduction of the Ruhr, but coupled it with a continuing drive to the east. Along with General Gillem’s XIII Corps, a portion of the XIX Corps was to drive east, while two divisions attacked southwest from the vicinity of Hamm and Lippstadt toward the Ruhr River.

In the First Army, General Hodges gave the job of renewing the drive east to Collins’s VII Corps and Huebner’s V Corps. Van Fleet’s III Corps, pinched out of a lineup at the Eder reservoir, was to take over from Collins along that part of the periphery of the Ruhr Pocket facing generally west, while headquarters of Ridgway’s XVIII Airborne Corps, its job in Operation VARSITY over, shifted to the First Army and assumed command of those units facing northward along the Sieg River. The attack to clear the pocket thus was to be, in essence, a converging attack by the equivalent of four corps.34

Splitting the pocket at the Ruhr River gave almost all the heavily built up industrial district to the Ninth Army. There the landscape is so urbanized that one city, grimy from the smoke of steel mill and blast furnace, blends

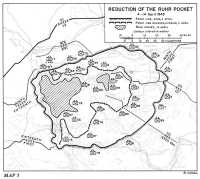

Map 5: Reduction of the Ruhr Pocket, 4–14 April 1945

almost imperceptibly into another—Duisburg, Essen, Gelsenkirchen, Bochum, Dortmund. If the Germans had had sufficient strength, the fighting there could have become a plodding, block-by-block campaign.

South of the Ruhr River, the First Army sector had no such concentration of industrial districts, though there were major cities—Duesseldorf, Wuppertal, the eastern suburbs of Cologne—but it was about three times the size of that of the Ninth Army. It was a sector of rugged terrain—steep hills and gorgelike valleys—at least 80 percent forested—a region known as the Sauerland.

The two corps of the Ninth Army began to attack in earnest on 4 April, the day the Ninth Army passed to control of the 12th Army Group. (Map 5) As the drive to clear the pocket began, no pattern emerged in the German defense north of the Ruhr River. As might have been expected the Germans made a contest

Infantrymen of the 79th Division cross the Rhein–Herne Canal

of it behind the water obstacle of the Rhein–Herne Canal, but once that established position was broken, one city or town might be stoutly defended, another abandoned without a fight.

It took a regiment of the 95th Division four days to clear Hamm, while contingents of the 17th Airborne Division, given a sector alongside the Rhine, walked into Duisburg almost without firing a shot. The 79th Division and other units of the 17th Airborne found no resistance in Essen, site of the great Krupp steel works, while at Dortmund, for no apparent reason, the Germans opposed the 75th and 95th Divisions stiffly, sometimes counterattacking with a fervor belying their lost cause. A combat command of the 8th Armored Division forestalled a sharp fight for Soest by making a quick 25-mile end run around the city, so threatening contingents of the 116th Panzer Division with encirclement that the Germans withdrew. At many small towns the burgomaster came out with a white flag; at others, the Germans fought until overwhelmed. The presence of SS troops more often than not made the difference.

South of the Ruhr River, where the

inhospitable terrain—laced by a limited roadnet passing through dense woods and narrow defiles and dotted with seemingly countless bridges over deep-cut streams—lent itself admirably to defense, resistance followed more conventional delaying tactics. The III Corps began to attack on 5 April, the XVIII Airborne Corps the next day. During the first few days, the Germans defended in some degree almost every town and village and most ridge and stream lines, particularly in the vicinity of Siegen, where several tank-supported counterattacks were apparently designed to keep the 8th Division from breaking into a fairly open corridor leading through the Sauerland, and near Winterberg, where the Germans had concentrated for their attempt at breakout; but as they were pushed back some four to six miles each day, their numbers and their resolution decreased.35

By 11 April the Germans were seldom defending ridges or wooded areas; resistance centered only in towns and villages along main roads. Sometimes bridges were left intact even when prepared for demolition. At Wuppertal, an S-2 of the 78th Division used the civilian telephone system to try to talk the mayor into surrender, but in vain. At other places both the 78th and 99th Divisions had greater success by using tank-mounted public address systems to demand surrender. In those later days opposition almost always centered around a roadblock covered by infantry supported either by a few tanks and assault guns or by antiaircraft pieces, usually 20-mm. “flakwagons.” At one point the Germans delayed the 7th Armored Division by blanketing a valley with a dense smoke screen.36

Beginning on 7 April days of overcast and light rain gave way to warm sunny weather, enabling planes of the IX and XXIX Tactical Air Commands to aid the mop-up. North of the Ruhr River, the aircraft could make few contributions other than those against isolated strongpoints, both because that part of the pocket shrank fairly rapidly and because pilots now were forbidden to hit a usual primary target, railroad rolling stock (the Allies soon would need all boxcars they could get). Although the ban also applied to planes of the IX Tactical Air Command south of the Ruhr River, the area there was vast enough to provide other targets, particularly columns of foot troops and horse-drawn and motor vehicles retreating or shifting positions.

In the Ninth Army’s sector, notably in the zone of the XVI Corps, artillery operating for the first time with unrationed ammunition supplies more than made up for the restrictions on aircraft. Artillery in support of the XVI Corps alone fired 259,061 rounds in fourteen days. Both artillery and air units had to observe the Ruhr River scrupulously as

a “no fire” line lest, in the converging attack, they hit friendly troops.

In the course of the advance almost every division overran a number of military hospitals, and several units liberated prisoner-of-war camps. At Waldbroel, not far north of the Sieg River, the 78th Division freed 71 hospitalized American soldiers, only 2 of whom were able to walk. At Hemer the 7th Armored Division rescued 23,302 prisoners of war, most of them Russians, living under appalling conditions of filth, disease, and hunger. The only Americans, a group of 99, were in fair condition, having been assigned to the camp only a few days. Among the others, deaths were averaging more than a hundred a day.37

The advance also freed thousands of forced laborers. In Hagen alone, 16,000; in Wuppertal, 30,000. Almost everywhere the sudden release of these people on the countryside produced incidents of looting and terrorizing. In the III Corps liberated slave laborers so congested the roads that the corps commander ordered them restricted to their compounds. Finding food and transportation for them and for thousands of German prisoners harried quartermasters and transportation officers alike.

In the cities, block after block of rubble attested to the destructive proficiency of Allied bombers, although the effect on German production had been less real than apparent. Machines and facilities were in many cases intact or could be put into operation after relatively minor repairs. Many plants had been moved to protected locations or their operations decentralized into scores of small, isolated buildings often untouched by bombs.

During the course of the attack, command adjustments took place in both the First and Ninth Armies. The 5th Division joined the attack of the III Corps on 9 April, releasing the 9th Division for a rest; arrival of the 13th Armored Division (Maj. Gen. John B. Wogan) on 9 April provided an armored component for the XVIII Airborne Corps. North of the Ruhr, the 194th Glider Infantry Regiment of the 17th Airborne Division reinforced the XIX Corps, while the remainder of the division went to the XVI Corps. To control the glider infantry, the 15th Cavalry Group, the 8th Armored Division, and the 95th Division, while the rest of the XIX Corps participated in the Ninth Army’s continuing drive to the east, the corps commander, General McLain, grouped them on 7 April into a task force under the 95th Division commander, General Twaddle. As the two divergent attacks put the two contingents of the XIX Corps ever farther apart—180 miles by 8 April—General Simpson transferred operational control of Task Force Twaddle to Anderson’s XVI Corps.38

In the First Army, the commanders of both corps tried hard to speed the advance by shaking loose their armored divisions, but it was 12 April before the 7th Armored Division of the III Corps could move out in front of neighboring infantry divisions, and the 13th Armored Division of the XVIII Airborne Corps never did achieve a lightning advance. Committed on 10 April to pass through troops of the 97th Division (Brig. Gen.

Milton B. Halsey), the 13th Armored was to drive rapidly along relatively flat terrain close by the Rhine to a point east of Cologne, then turn northeast to get in behind those Germans fighting against the 8th, 78th, and 86th (Maj. Gen. Harris M. Melasky) Divisions, deep in the Sauerland. This was the armored division’s baptism of fire; only two of its combat commands and little of the division trains had arrived by jump-off time early on 10 April, and both men and equipment were worn out from two road marches totaling more than 260 miles with no time between for rest or servicing equipment. One combat command was down to 50 percent of normal strength in medium tanks.

Pressed by General Hodges to speed the mop-up in order to release units to reinforce the drive to the east, the corps commander, General Ridgway, would approve no pause before the attack; but Ridgway himself, in effect, slowed the attack in advance by ordering the division to “destroy” German forces encountered.39 Although the order ran contrary to armored doctrine, the division commander, General Wogan, and his subordinates took it literally.

Hardly had the advance begun when communications among various components of the division broke down and some units lost their way. A stream held up the columns as tanks and infantry deployed to “destroy” the enemy. (General Ridgway specifically changed the order on the 12th.) Not until late on 13 April did leading troops reach the point east of Cologne where the division was to change direction to the northeast. By that time the infantry divisions that the armor was to have assisted by trapping the enemy in front of them were already practically on top of the armor’s final objectives.40

Early on the 14th General Ridgway changed his instructions, telling the armor to continue north generally along the Rhine. Even then bad luck continued to plague the division as the commander, General Wogan, having gone forward to speed removal of a roadblock, was seriously wounded by rifle fire. The former commander of the III Corps, General Millikin, took his place.

Driving past what had been the armored division’s objectives and going another ten miles to the north, a battalion of the 8th Division’s 13th Infantry late on 14 April reached the Ruhr River at Hattingen, southeast of Essen. Jubilantly, the men shouted across the river to men of the 79th Division’s 313th Infantry. On the north bank the last of the Ninth Army’s forces had closed to the river, signaling elimination of that part of the Ruhr Pocket. The 13th Infantry’s thrust meant that the pocket south of the river was split into two enclaves, the larger to the west embracing the cities of Duesseldorf and Wuppertal.

For the next two days there would still be an occasional sharp engagement in the Ruhr Pocket, but for the most

Russian prisoners liberated by the Ninth Army

part a new phase of the battle had begun. It was a time for mass surrenders, a full and final collapse.

“The predominant color was white.”

The question of when and how to surrender had been before German staffs and commanders in the Ruhr since the American pincers closed on Easter Sunday, particularly so since failure of the breakout attempts at Winterberg. Yet the belief among most of the staff of Army Group B was that the fight was worthwhile because it was holding up the drive to the east by pinning down eighteen American divisions (four were west of the Rhine).41

When news of continuing American advances to the east came on 7 April, this rationale was no longer valid. Field Marshal Model’s chief of staff, Generalmajor Karl Wagener, urged Model to spare his troops and the civilians in the Ruhr further fighting by asking Hitler’s approval to surrender. This Model declined to do. In the first place, permission hardly would be granted. Furthermore,

German soldiers on the way to a prisoner-of-war camp without guard

Model himself could not reconcile surrender with the demands he had put on his officers and troops through the years. Yet news both within and without the Ruhr Pocket was so utterly devoid of hope that Model continued to struggle with his conscience for a solution. Every life saved was another life capable of taking up the struggle to rebuild Germany. He at last decided, in effect, simply to dissolve Army Group B by order. There could be no formal surrender of a command that had ceased to exist.

All youths and older men, Model decreed on 15 April, were to be discharged from the army immediately, provided with discharge papers, and allowed to go home (the order, thousands were to discover, lacked American concurrence). As of two days later, 17 April, when ammunition and supplies presumably would be exhausted, all remaining noncombatant troops were to be free to surrender, while combat soldiers were to be afforded a choice either of fighting in organized groups in an attempt to get out of the pocket or of trying to make their way, either in uniform or civilian clothes but in any case without arms, back to

their homes. The latter was a veiled authority to surrender.

Even before this order was issued, sharply increasing numbers of German troops had begun to capitulate. American divisions that in the first few days of April were taking 300, 500, or even 1,000 prisoners a day, by 11 April and the days following were capturing in almost all cases 2,000 and sometimes as many as 5,000. Many a German walked mile after mile before finding an American not too occupied with other duties to bother to accept his surrender. A man from the 78th Division’s 310th Infantry started out of Wuppertal with 68 prisoners and discovered, upon arrival at the regimental stockade, that he had 1,200.

The most famous individual to emerge from the Ruhr was taken early. On 10 April, a patrol from the 194th Glider Infantry found Franz von Papen, the German chancellor before Hitler’s rise to power, at his estate near Hirschberg, not far from the eastern periphery of the Ruhr Pocket.

On the 13th, having lost all control over subordinate units, the commander of the Fifteenth Army, General von Zangen, surrendered along with his staff to the 7th Armored Division, as did General Koechling of the LXXXI Corps. The commander and all that remained of the once mighty Panzer Lehr Division surrendered on 15 April to the 99th Division.

On 16 April an all-out rush to give up began. People displayed handkerchiefs, bed sheets, table linen, shirts, anything to show intent to surrender. “The predominant color,” noted the 78th Division’s historian, “was white.”42 While liberated slave laborers milled about, cheering, laughing, and shouting, glum German civilians, incredulity stamped on their faces, watched silently or sought to ingratiate themselves with the conquerors by insisting that they had never been Nazis, that they were happy the Americans had come. There were no Nazis, no ex-Nazis, not even any Nazi sympathizers any more.

The prisoner-of-war list read like an order of battle, and with the commanders usually came their staffs and remaining troops: Bayerlein of the LIII Corps, Lüttwitz of the XLVII Panzer Corps, Waldenburg of the 116th Panzer Division, Denkert of the 3rd Panzer Grenadier, Lange of the 183rd Volksgrenadier, commanders of the 180th, 190th, and 338th Infantry Divisions, and the final remnants of the 9th Panzer Division. Paratroopers of the 17th Airborne Division apprehended the commander of the Fifth Panzer Army, General Harpe, as he tried to cross a bridge over the Ruhr River in an effort to make his way to German positions in the Netherlands. The commander of the XVIII Airborne Corps, General Ridgway, sent his aide under a white flag to headquarters of Army Group B to try to persuade Field Marshal Model to surrender himself and the entire command. Model refused.

The flow of prisoners continued on the 17th—young men, old men, arrogant SS troops, dejected infantrymen, paunchy reservists, female nurses and technicians, teen-age members of the Hitler Youth, stiffly correct, monocled Prussians, enough to gladden the heart of a Hollywood casting director. In every conceivable manner, too, they presented themselves to their captors: most plodding wearily on foot; some in civilian

Prisoners of war in the Ruhr Pocket

automobiles, assorted military vehicles, or on horseback; some pushing perambulators; one group riding bicycles in precise military formation; a horse-drawn artillery unit with reins taut, horses under faultless control; some carrying black bread and wine; others with musical instruments—accordions, guitars; a few bringing along wives or girl friends in a mistaken hope they might share their captivity. With tears streaming down his face, the officer in charge of a garrison in one town surrendered his command in a formal, parade-ground ceremony.

Prisoner-of-war cages were nothing more than open fields hurriedly fenced with a few strands of barbed wire. Here teeming masses of humanity lolled in the sun, sang sad soldier songs, stared at their captors, picked at lice. Those among them who spoke English offered their services profusely as translators. Some were in high spirits, others bedraggled, downcast. There was nothing triumphant about it; it was instead a gigantic wake watching over the pitiable demise of a once-proud military force.

“Have we done everything to justify our actions in the light of history?”

Field Marshal Model asked his chief of staff on one of those last days. “What is there left to a commander in defeat?”

Model paused, then answered his own question.

“In ancient times,” he said, “they took poison.”43

On 18 April all but a few stragglers gave up, all resistance at an end. Some 317,000 Germans were captured—more than the Russians took at Stalingrad, more even than the total of Germans and Italians taken at the end of the campaign in North Africa. Thousands more, of whom there was no record, had perished in the fighting.

The mop-up cost units of the Ninth Army 341 killed, 121 missing, and not quite 2,000 wounded. The First Army losses probably were about three times as high.44

As the battle ended, one of the stragglers was the commanding general of Army Group B, Field Marshal Model. Having ordered his staff to disperse, Model himself repaired with his aide and two other officers to a forest north of Düsseldorf.

To those who knew the field marshal intimately, it was a certainty that he would never surrender. He had long been critical of Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus for capitulating at Stalingrad. “A field marshal,” he had said then, “does not become a prisoner. Such a thing is just not possible.”

During the afternoon of 21 April, Model asked his aide to accompany him and walked deeper into the forest, away from the other two officers. There he shot himself.45