Chapter 19: Götterdämmerung

Although the Germans had no formal plans for a National Redoubt, Adolf Hitler had intended leaving Berlin on 20 April, his fifty-sixth birthday, to continue the fight from southern Germany. By mid-April the bulk of the ministerial staffs already had abandoned the capital in a frantic exodus to the south, though Hitler himself began to procrastinate. While conscious of the difficulty of holding Berlin indefinitely, he persisted in the self-delusion that time remained, and even that his armies might achieve a spectacular victory before Berlin.

The atmosphere in the Führerbunker beneath the ruined city ranged alternately from despair to blind hope. One moment Hitler railed that the German people had failed him; they deserved the cruel fate they would suffer at the hands of the conqueror from the east. The next moment it was his generals—incompetent, negligent, spineless; they were fools, fatheads. Yet when a general occasionally dared to speak the truth, to reveal that the end was near, Hitler seized on some new scheme designed to set everything right again—previously uncommitted (and untrained) Luftwaffe and naval troops thrown into the line, a counterattack here, a shift of forces there.

The early moments of 13 April brought news that elated many of Hitler’s coterie, if not the Führer himself. Goebbels, the propagandist, reported it to Hitler by telephone while an air attack raged over the city. As it had been written in the stars, the miracle Goebbels had been awaiting to save the Third Reich, as in an earlier day another had saved Frederick the Great, had come to pass.

“My Führer!” Goebbels exclaimed. “I congratulate you! Roosevelt is dead.”1

The events that followed—among other reverses, Vienna fell that day to the Russians—hardly confirmed Goebbels’s expectations of deliverance from the enemies of the Reich. Hitler nevertheless used the President’s death to exhort his troops to supreme effort. In an order of the day on 15 April, he proclaimed: “At the moment when fate has removed the greatest war criminal of all time from the earth, the turning point of this war shall be decided.”

As the military high command and the party hierarchy gathered in the bunker to pay obeisance to the leader on his birthday, Hitler repeatedly professed faith that the Russians were about to incur their worst defeat in front of Berlin. Even though the generals warned that Russians and Western Allies soon would link to cut all escape routes to the south, he declined to leave the capital. Should the linkup occur, he decreed, the

front was to be divided into two commands, to be headed in the north by Grossadmiral Karl Doenitz, the naval chief; in the south by someone else, perhaps Kesselring or the Luftwaffe’s Hermann Goering.

Hitler then sanctioned the departure of various commanders and party leaders from Berlin, which most were happy to leave in desperate hope of saving their skins or at least postponing the end. The SS chief, Himmler, scurried north to continue peace negotiations he had recently opened in secret with Count Folke Bernadotte, head of the Swedish Red Cross. Doenitz too moved north. In a truck caravan loaded with luxuries, Goering turned south. Foreign Minister von Ribbentrop also got out, as did most of the staff officers and clerks of OKW and OKH, though Keitel and Jodl remained with a small staff in a western suburb to keep OKW functioning. The faithful Goebbels was invited to move with his wife and children into the bunker, to which Hitler’s mistress, Eva Braun, already had repaired.

The next day, 21 April, Hitler hit on a new scheme to set everything right. From the north an SS corps was to counterattack to break through Russian columns and relieve the city. Yet twenty-four hours later even Hitler had to admit that this offered no hope. At the daily situation conference, he exploded in what may have been the greatest of many notable rages. This was the end. Everybody had deserted him; lies, corruption, cowardice, treason. They had left him no choice but to remain in Berlin to direct the defense of the capital himself and die.

Then hope stirred again as General Jodl proposed that Wenck’s Twelfth Army turn its back on the Allies at the Elbe and come to the relief of Berlin. That Hitler ordered, along with a drive on Berlin from the south by the Ninth Army, already threatened by Russian encirclement. Keitel and Jodl were to direct the converging attack. When the stratagem inevitably failed, continued Russian advances forced the remnants of OKW to displace farther and farther to the north.

Learning on the 23rd of Hitler’s decision to stay in Berlin, Reichsmarshal Goering, whom Hitler long ago had designated to be his successor, believed the time had come for him to take over and try to salvage something by peace negotiations. From Berchtesgaden, he radioed Hitler for instructions, noting that if he received no answer by late evening, he would assume that Hitler had lost freedom of action, whereupon he would take control.

That same evening, in the north, Heinrich Himmler was usurping the powers of dictatorship without even asking. Concluding his negotiations with Count Bernadotte, Himmler signed a letter to General Eisenhower. Germany, he wrote, was willing to surrender to the Western Powers while continuing to fight the Russians until the Allies themselves were ready to assume responsibility for the campaign against bolshevism.

Goering’s message threw Hitler into another rage, as would the news of Himmler’s act when it reached the bunker several days later by way of a monitored broadcast of the BBC. Accusing Goering of “high treason,” Hitler demanded his resignation from command of the Luftwaffe and from the Nazi party. Before dawn the next day, the heir-apparent

of the Third Reich found himself under arrest by the SS.

By that time, 23 April, the Russians had completed encircling Berlin. Although linkup between Russians and Allies was yet to come, the encirclement, in effect, split the German command. As Jodl notified all senior commanders that the fight against bolshevism was the only thing that mattered and that loss of territory to the Western Allies was secondary, Hitler on 24 and 25 April approved a new command structure for the Wehrmacht. Abolishing OKH, Hitler made OKW responsible, subject to his authority, for operations everywhere. As head of OKW, Keitel reserved for himself control of all army units in the north until such time as communications with Hitler might be severed, whereupon he would submit to the authority of Admiral Doenitz. He designated another commander for those forces opposing the Russians south of Berlin, General der Gebirgstruppen August Winter, and directed Field Marshal Kesselring to assume command of German forces in Italy, Austria, and the Balkans in addition to his command of Army Group G and the Nineteenth Army.

OKW’s primary mission, Hitler directed, was to re-establish contact with Berlin and defeat the Soviet forces there. Making his first specific reference to creating a redoubt, he issued a half-hearted directive to units in the south to prepare a defense of the Alps “envisioned as the final bulwark of fanatical resistance and so prepared.” Just how either of those assignments was to be accomplished, he did not say.2

The Meeting at Torgau

As these futile efforts to keep up a pretense of hope persisted on the German side, a fever of expectation that contact with the Russians was imminent had begun to grip Allied troops and commanders, particularly those of the First and Ninth U.S. Armies holding the line of the Elbe and Mulde Rivers. Eager to go down in history as the unit that first established contact, divisions vied with each other in devising stratagems to assure the honor for themselves. Which unit was the leading contender at any given time might have been judged from the size of the press corps that flitted from one headquarters to another in an impatient wait to report the event.

What would happen when Allied and Russian troops came together had been on many minds on the Allied side for a long time. Because the Russians throughout the war had treated the Western Powers with suspicion and distrust, creating a workable liaison machinery had proved impossible; even where makeshift arrangements had been established, the Russians had disrupted them constantly by procrastination and delay.3 While the disruption was merely exasperating in early stages of the war, it became as the war neared an end potentially dangerous. Misunderstandings, even collisions resulting in casualties, were possible among U.S. units fighting side by side; as Allied and Russian troops devoid of liaison approached each other in fluid warfare where even division commanders were not always sure within

twenty to forty miles where their forward troops were located, serious clashes might ensue, resulting not only in casualties but possibly in postwar recrimination.

The problem for the air forces had long been acute. As early as the preceding November, U.S. fighters attacking what they identified as a German column in Yugoslavia had killed, the Soviets charged, several Russian soldiers, including a lieutenant general. Despite the incident, efforts to establish effective coordination with the Russians by means of a flexible bomb line had been basically unproductive until March 1945, when the Russians at last agreed to a bomb line 200 miles short of forward Russian positions. The line was not to be violated by Allied planes except on 24-hour notice, which the Russians might veto.

Although the Western Allies and the Russians had sealed an agreement on zones of occupation at the Yalta Conference, no one pretended that the demarcation lines corresponded with military requirements, though the Russians from time to time expressed concern about Allied intentions to withdraw from the Soviet zone once hostilities ceased. In a series of exchanges lasting past mid-April, the Combined Chiefs of Staff, General Eisenhower, and the Red Army’s Chief of Staff finally agreed that the armies from east and west were to continue to advance until contact was imminent or linkup achieved. At that point adjustments might be made at the level of army group to deal with any remaining opposition while establishing a common boundary along some well-defined geographical feature.

Since the arrangement did little to forestall the possibility of Allied-Soviet clashes, General Eisenhower began, even as the exchanges proceeded, to negotiate on recognition signals. At Eisenhower’s request, the Red Army’s Chief of Staff suggested as an over-all recognition signal, red rockets for Soviet troops, green rockets for Allied. Eisenhower concurred. To a Russian proposal that Soviet tanks be identified by a white stripe encircling the turret, Allied tanks by two white stripes, and that both place a white cross atop the turret, General Eisenhower suggested instead that to avoid a delay in operations while putting on new markings, the Soviet troops be acquainted with existing Allied markings. The Russians agreed, and by 21 April identification arrangements were complete.4

General Eisenhower also proposed exchanging liaison officers, which the Russians neither refused nor encouraged, and asked the Russians for details of their operational plan while expanding on his own, which, to the chagrin of the British, he had revealed broadly not quite a month before. Repeating the intent stated earlier to stop his central forces on the Elbe–Mulde line, Eisenhower noted that the line could be changed to embrace upper reaches of the Elbe should the Russians want him to go as far as Dresden. His northern forces, he made clear, were to cross lower reaches of the Elbe and advance to the Baltic Sea at the base of the Jutland peninsula, while forces in the south drove down the valley of the Danube into Austria.

The Russians responded with unusual alacrity. Agreeing to the line of the Elbe–Mulde

as a common stopping place, they noted that the Soviet armies, in addition to taking Berlin, intended to clear the east bank of the Elbe north and south of Berlin and most of Czechoslovakia, at least as far as the Vltava (Moldau) River, which runs through Prague.

Coordination with the Russians would come none too soon for commanders of units that were hourly anticipating contact. General Hodges of the First Army, for example, spent much of the morning of 21 April trying to get instructions from SHAEF on procedures to be followed, only to obtain little guidance other than to “treat them nicely.”5 It was past midday when confirmation from the Russians on recognition signals arrived and word went out to subordinate units.6

As finally determined, whoever made the first contact was to pass word up the chain of command immediately to SHAEF, meanwhile making arrangements for a meeting of senior American and Russian field commanders. To the vexation of the small army of excited war correspondents, no news story was to be cleared until after simultaneous announcement of the event by the governments in Washington, London, and Moscow.7

First word was that bridgeheads already established over the Elbe (the 83rd Division’s at Barby) and the Mulde (those of the 69th Division east of Leipzig; the 2nd Division southeast of Leipzig; the 6th Armored and 76th Divisions near Rochlitz, northwest of Chemnitz; and the 87th and 89th Divisions west of Chemnitz) might be retained; but another message from the Russians early on the 24th changed that.8

Beginning at noon that day, the Russians revealed, they were to start an advance on Chemnitz by way of Dresden. During the advance, their air force would refrain from bombing or strafing west of the line of the Mulde as far south as Rochlitz, thence along a railroad from Rochlitz to Chemnitz, then to Prague. General Eisenhower promptly ordered all bridgeheads across the Mulde withdrawn as far south as Rochlitz with only outposts to protect bridges and small patrols to make contact with the Russians remaining on the east bank. Patrols were to venture no more than five miles beyond the Mulde.

Excitement among First and Ninth Army units was mounting all along the line. Rumor piled upon rumor; one false report followed another. Russian radio traffic cutting in on American channels convinced almost everybody that contact was near. Word was on the 23rd that a staff sergeant in the 6th Armored Division actually had talked by radio with the Russians. Unit after unit reported flares to the east, attaching to them varying interpretations. A battalion of the 69th Division on 23 April reported sighting a Russian tank with a white stripe around the turret, then had to admit

that it was actually a grassy hummock with a clothesline stretched across it.9

Men of the 84th Division painted signs of welcome in Russian. The division canceled all artillery fire beyond the Elbe lest it hit Russian troops, but rescinded the order when German soldiers on the east bank began blatantly to sunbathe. At General Hodges’ command post, a specially outfitted jeep was ready by the 23rd for presentation to the army commander of the first Russian troops encountered.10

After pilots of tactical aircraft reported numerous (but erroneous) sightings of Russian columns east of the Elbe, almost all divisions sent their frail little artillery observation planes aloft for a look. The pilot of a plane belonging to the 104th Division was convinced of success late on the 23rd when far beyond the Mulde he spotted a column of troops. Landing, he found only Germans with a few British prisoners heading west in hope of surrendering. Another pilot from the 104th Division flew fifteen miles east of the Elbe beyond the town of Torgau on 24 April, where he observed what appeared to be an artillery duel between Russians and Germans. Although he tried to land behind Russian lines, antiaircraft fire turned him back. Other units on the 24th reported seeing Russian planes over American positions.

Although the 83rd Division in its bridgehead over the Elbe readied a task force that included tanks, tank destroyers, and a company of infantry to probe eastward to find the Russians, the force dutifully awaited approval from higher command before setting out. There were few other units that did not, in the meantime, violate the order on depth of patrols. Some patrols of the 2nd Division probed in vain up to seven miles beyond the Mulde. One from the 104th Division’s reconnaissance troop, composed of three men under 1st Lt. Harlan W. Shank, roamed more than twenty miles and reached the Elbe at Torgau late on April 23rd, spent the night in the town under occasional Russian artillery fire, and finally departed at noon on the 24th after seeing no Russian troops.

Through it all, the men along the line of the Mulde still had a war to fight—after a fashion. As late as the 22nd, part of the 69th Division’s 271st Infantry was fighting hard to clear the town of Eilenberg, astride the Mulde, and after night fell had to repulse a determined counterattack by as many as 200 Germans. Company-size counterattacks also hit some units of the 2nd Division. Meanwhile, other German soldiers in small groups and in large poured into American lines, eager to surrender. Every division handled thousands each day, as well as hundreds of American and Allied prisoners released by their captors. At the same time hordes of civilians gathered at bridges over the Mulde, terrified of the Russians, tearfully hopeful of refuge within American lines. Although the official word was to turn back German civilians, many an American soldier looked the other way as the refugees tried to pass, or liberally interpreted the proviso that foreign laborers might cross.

Unwittingly setting the stage for momentous events to follow, the burgomaster of Wurzen, on the Mulde’s east bank east of Leipzig, begged permission late

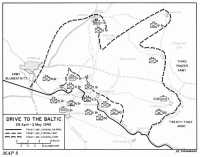

Map 7: The American-Russian Linkup, 25 April 1945

on the 23rd to surrender his town to the 69th Division’s 273rd Infantry. Since the burgomaster’s purpose was to release thousands of American and Allied prisoners and to surrender hundreds of German troops in the town, and since a restraining order on bridgeheads over the Mulde was yet to come, commanders up the chain of command sanctioned the move. The bulk of a battalion crossed the Mulde in early evening into Wurzen to participate in a chaotic night of processing both the liberated and the newly captured.

By the afternoon of 24 April nobody yet had any definite word of the Russians. Nor could anyone know that contrary to the agreement with General Eisenhower, Russian troops approaching that part of the Elbe which runs some eighteen to twenty miles east of the Mulde were under orders to halt, not at the Mulde but at the Elbe. Word on the Mulde as a demarcation line had yet to

pass down the Russian chain of command.11

Frustrated by the prolonged wait, the commander of the 273rd Infantry, Col. Charles M. Adams, in midafternoon of 24 April directed 1st Lt. Albert L. Kotzebue of Company G to lead a jeep-mounted patrol of thirty-five men “to contact the Russians.” Lieutenant Kotzebue was to go only as far as Kühren, a village four miles beyond the Mulde; but when he reached Kühren after encountering only a few hospitalized Allied prisoners and hundreds of docile Germans anxious to surrender, he gained permission to proceed another three miles, technically two miles beyond the five-mile limit. (Map 7) That Kotzebue did, encountering only the usual German groups trying to escape the Russians, then returned to Kühren to bed down for the night. Although he received two messages ordering his patrol to return before dark, Lieutenant Kotzebue ignored them because it was already well after dark.

With no further word from Kotzebue, Colonel Adams that night ordered two more patrols to depart the next morning, 25 April. The orders were the same, “to contact the Russians,” again within the five-mile limit. Members of one patrol made up of the regiment’s intelligence and reconnaissance platoon apparently accepted the limitation without question. Those of another commanded by a platoon leader of Company E but accompanied by the 2nd Battalion’s executive officer, Maj. Frederick W. Craig, took the restriction less seriously. To a man they entered into a kind of humorous conspiracy to meet the Russians, regardless. As the two patrols left in jeeps mounting machine guns early on the 25th, no one yet had heard anything more from Lieutenant Kotzebue in Kühren.

Later in the morning, at Wurzen, the 1st Battalion’s S-2, 2nd Lt. William D. Robertson, awoke from a deep sleep occasioned by staying up the previous night to help process the surrendering Germans and liberated Allied prisoners in the town. With three men, Lieutenant Robertson left by jeep in midmorning to scout neighboring towns and villages for other Allied prisoners and other Germans wanting to surrender. Having no radio with him, Lieutenant Robertson had no intention of contacting the Russians as he headed eastward.

In Kühren, in the meantime, Lieutenant Kotzebue and his men had awakened to a breakfast prepared by villagers eager to please in fear that if the Americans left, the Russians would come with the reign of terror that rumor promised would follow. Caught up in the general expectation that the Russians were on their way, Lieutenant Kotzebue saw no reason why he should not be the one to meet them first. His orders, “to contact the Russians,” he deemed sufficiently broad to warrant continuing toward the east. Leaving his radio jeep in Kühren to serve as a relay point for messages, he headed east with the bulk of his patrol.

Thus, in midmorning of 25 April, four separate groups of the 69th Division’s 273rd Infantry were moving eastward. Only one, the intelligence and reconnaissance platoon, was concerned enough

with the five-mile restriction to comply with it.12

Encountering dispirited German soldiers, jubilant American and Allied prisoners, apprehensive German civilians, and exuberant, sometimes intoxicated foreign laborers, Lieutenant Kotzebue and his men advanced almost due east through the town of Dahlen toward the Elbe in the vicinity of Strehla, a few miles northwest of Riesa, some seventeen miles southeast of Torgau. It was almost noon as the jeeps slowed to enter the farming village of Leckwitz, less than two miles from the Elbe.

Far down the main street, the men spotted a horseman just as he turned his mount into a courtyard and passed from view. At a glance, the man’s costume seemed unusual. Could it be? Was this it?

Spinning forward, the jeeps came to a halt at the entrance to the courtyard. Inside, among a crowd of foreign laborers, was the horseman. There could be no doubt. He was a Russian soldier.

The time was 1130 on 25 April, the setting inauspicious, but the moment historic: the first contact between Allied armies from the west, Soviet armies from the east.

Through Russian-speaking Tech. 5 Stephen A. Kowalski, Lieutenant Kotzebue asked directions to the soldier’s commander; but the Russian was suspicious and reserved. Waving his arm to the east, he suggested that one of the foreign laborers, a Pole, could lead them better than he. With that, he galloped away.

Taking the Pole as a guide the patrol continued to the Elbe, a few hundred yards north of Strehla. Seeing uniformed figures on the east bank milling about the wreckage of a column of vehicles close to the remains of a tactical bridge, Lieutenant Kotzebue raised his binoculars. Again there could be no doubt. They were Russians. The rays of the sun reflecting off medals on their chests convinced him.

At the lieutenant’s direction, his driver fired two green signal flares. Although the figures on the far bank gave no answering signal, they began to walk toward the edge of the river. As Kotzebue’s driver fired another flare for good measure, the Polish laborer shouted identity across the water.

Using a hand grenade, Lieutenant Kotzebue blasted the moorings of a sailboat and with five of his men rowed across the Elbe. A major and two other Russians, one a photographer, met them. The meeting was at first restrained, but as Kotzebue explained who he was, the Russians relaxed.

Minutes later, Lt. Col. Alexander T. Gardiev, commander of the 175th Rifle Regiment, arrived. Making clear that he intended to take the Americans to meet his division commander, he suggested that the men return to the west bank of the Elbe and proceed northward to a hand-operated cable ferry opposite the village of Kreinitz. There the Russians would meet them again, presumably at the pleasure of two motion-picture cameramen who by that time also had arrived on the scene.

Returning to the west bank, Kotzebue sent one of his jeeps accompanied by his second-in-command back to Kühren with a message to be transmitted by radio to headquarters of the 273rd Infantry. Making a mistake he would come to rue,

the lieutenant gave the wrong map coordinates for his location.

Lieutenant Kotzebue signed his message at 1330. His regimental commander, Colonel Adams, received it not quite two hours later: “Mission accomplished. Making arrangements for meeting between CO’s. Present location (8717). No casualties.”

Hardly had Colonel Adams telephoned that information to the division’s chief of staff when the division commander, General Reinhardt, picked up the phone. Reinhardt was irate. As late as that morning he had been at Adams’s command post where he had reiterated the order that patrols were to go no more than five miles beyond the Mulde. If Kotzebue was where the map coordinates indicated, he was far beyond the Mulde at the Elbe itself on the fringe of the town of Riesa.

General Reinhardt’s first reaction was to clamp a blackout on the news until Colonel Adams could verify it by a meeting with the Russians himself. On second thought he telephoned the V Corps commander, General Huebner, who reacted much as had Reinhardt but passed the word to General Hodges at First Army. Hodges passed it on to General Bradley at 12th Army Group, who took it calmly.

Mollified by this reaction near the top and rationalizing that Lieutenant Kotzebue might not have known of the five-mile restriction, General Reinhardt still was reluctant to publicize the contact without some confirmation. Time for proof was short, for despite all efforts to contain the news, rumors of a meeting with the Russians were rife throughout the division, and correspondents already were deserting neighboring divisions to rush to the 69th’s command post. To speed confirmation, Reinhardt directed Adams to cancel arrangements for a personal meeting with the Russians pending a flight by the division G-3 in an artillery spotter plane to the site Lieutenant Kotzebue had specified.

The results of the flight further confused the issue. Taking along an interpreter in a second plane, the G-3 flew to Riesa, which marked the coordinates Kotzebue had mistakenly given. Antiaircraft fire at Riesa turned both planes back.

On two occasions, in late morning and early afternoon of 25 April, Colonel Adams ordered Major Craig and the 47-man patrol from the 273rd Infantry’s 2nd Battalion to advance no farther. Both times he qualified the order with authority “to scout out the area” near where the patrol was located. Both times Major Craig used this authority to justify continuing toward the east.

Craig and the men with him, like Lieutenant Kotzebue and his men, were caught up in the elation of the moment. Abroad in what was technically enemy territory, they were welcomed by jubilant foreign laborers and Allied prisoners as liberators, by the German populace and soldiers as saviors from some ephemeral dread called “the Russians are coming.” Only occasionally did a German soldier display any inclination to fight. One word and white flags appeared in the villages as if by magic.

Craig had another incentive to continue. With him was a historian, Capt. William J. Fox, operating out of headquarters of the V Corps. Rationalizing that he was not subject to the five-mile restriction, Fox insisted that if Craig felt

obligated to turn back, he personally would continue to contact the Russians.

Two hours after the second stop order from Colonel Adams, Major Craig and his patrol still were traveling eastward. The patrol’s radio was delightfully void of any more orders, and Craig sent no further reports on his position lest they generate a new directive to halt.

By midafternoon the patrol had reached a point less than three miles from the Elbe when two jeeps overtook the column. They carried men from Lieutenant Kotzebue’s patrol on their way forward from Kühren after having relayed the message telling of Kotzebue’s meeting with the Russians.

All doubts about continuing to the Elbe erased by this news, Craig’s patrol was heading for Leckwitz, the village where Kotzebue had first encountered the lone Russian, when a cloud of dust revealed the approach of horsemen. Craig halted his jeeps and the men piled out, eager and excited at the prospect of meeting what obviously was Russian cavalry interspersed with a few men on motorcycles and bicycles.

“I thought the first guy would never get there,” one soldier recalled. “My eyes glued on his bicycle, and he seemed to get bigger and bigger as he came slower and slower towards us. He reached a point a few yards away, tumbled off his bike, saluted, grinned, and stuck out his hand.”13

The time was 1645, 25 April.

After a few self-conscious speeches from both sides extolling the historic moment, the Russians went on their way south toward Dresden, while Craig and his patrol hurried on to the Elbe to join Lieutenant Kotzebue on the east bank. There the commander of the 58th Guards Infantry Division, Maj. Gen. Vladimir Rusakov, whose 175th Regiment had made the first contact with Kotzebue, saw it his duty for the second time in the same afternoon to welcome an American force with toasts in vodka to Roosevelt, Truman, Churchill, Stalin, the Red Army, the American Army, and, it seemed to some Americans present, to every commander and private soldier in each army.

Back at headquarters of the 273rd Infantry on the Mulde, a radio message from Major Craig arrived shortly before 1800: “Have contacted Lieutenant Kotzebue who is in contact with Russians.” To Colonel Adams, that confused the issue more than ever.

Having left Wurzen in midmorning of 25 April in a jeep with three men in search of Allied prisoners and surrendering Germans, Lieutenant Robertson, the 1st Battalion S-2, experienced much the same reactions to the arrival of Americans in the German towns and villages as did the patrols of Kotzebue and Craig. Although Robertson had no intention at first of trying to find the Russians, he kept moving from one town to the next until at Sitzenroda, a little past the midpoint between Mulde and Elbe, a group of released British prisoners told him there were many American prisoners, some of them wounded, in Torgau on the Elbe. Already exhilarated by the ease with which he was moving across the no man’s land between the two rivers, Robertson used the information to justify his continuing to Torgau, rescuing the prisoners, and if possible, meeting the Russians.

Entering Torgau in midafternoon, Lieutenant Robertson searched for the reported American prisoners to no avail, though he did find a group of released prisoners of various nationalities that included two Americans, a naval ensign and a soldier. The two joined Robertson’s little band. The few German troops encountered appeared to be preparing to leave the town and readily gave up their weapons.

Hearing small arms fire from the direction of the Elbe, Robertson and his men headed through the center of the town toward a castle on the river’s west bank. Assuming that the fire came from Russians east of the Elbe, Robertson yearned for an American flag to establish his identity. As he passed an apothecary shop, the idea came to him that he could make a flag. Inside the shop, he found red and blue water paint with which he and his men fashioned a crude flag from a white sheet.

With the flag in hand, Robertson climbed into a tower of the castle. Although the firing had stopped, he could see figures moving about on the east bank of the Elbe. Displaying the flag outside the tower produced no fire, but when one of Robertson’s men showed himself, the figures on the east bank began again to shoot.

At long last the firing stopped, and a green signal flare went up from the other side of the river. Robertson was elated. That, as he remembered it, was the agreed recognition signal to be fired by the Russians. (The Russians should have fired a red signal.) Certain that the figures on the east bank were Russians and not having a flare with which to answer, Robertson sent his jeep back to the Allied prisoners found earlier to bring up a Russian who had been among the lot.

Climbing the tower, the Russian shouted across to the east bank. Almost immediately the figures beyond the Elbe began to mill about. They understood, the freed prisoner shouted from the tower, that Robertson and his men were Americans.

With that, Robertson and his little group rushed to a destroyed highway bridge and slowly began to climb across the river on twisted girders. A Russian soldier from the far bank began to climb toward them. The soldier and the released prisoner met first, then Robertson reached the soldier. The lieutenant could think of nothing to say. He merely grinned and pounded the Russian exuberantly.

The time was 1600. Although word of Major Craig’s contact reached the 273rd Infantry command post before that of Robertson’s, the meeting on a girder above the swirling waters of the Elbe was by some forty-five minutes the second contact between the armies from east and west.

Once on the east bank, Americans and Russians pounded each other on the back, everybody wearing a perpetual grin, then drank a series of toasts in wine and brandy provided by the Russians. They had fired on Robertson’s flag, the Russians explained, because a few days earlier a group of Germans had displayed an American flag to halt Russian fire and make good their escape. The impromptu celebration went on for an hour. When Robertson at last announced a return to his own headquarters, a Russian major, two lesser officers, and a sergeant volunteered to go

Lieutenant Robertson (extreme left) shows General Eisenhower the makeshift flag displayed at the Elbe

with him. They were from the 173rd Rifle Regiment.

Shortly after 1800, Lieutenant Robertson and his overloaded jeep arrived at the 1st Battalion command post in Wurzen. As soon as he could convince his battalion commander that the Russians were genuine soldiers, not released prisoners, word passed up the line to regiment.

To Colonel Adams this development was more startling than the others. He had ordered no patrol from the 1st Battalion, yet the battalion had four Russians as living proof of contact. He ordered them brought to his headquarters, where they successfully ran a gantlet of war correspondents and photographers who had almost inundated the 273rd Infantry command post.

When the division commander, General Reinhardt, learned of the new development, he was more irate than ever. The corps commander obviously was getting the impression that nobody in the 69th Division followed orders, and Reinhardt could hardly blame him. Reinhardt even toyed briefly with the

idea of a court-martial for Robertson. (Someone noted in the 273rd Infantry journal: “Something wrong with an officer who cannot tell 5 miles from 25 miles.”)

The fact that Robertson’s exploit had produced tangible evidence entitling the 69th Division to the acclaim of first contact with the Russians apparently had something to do with Reinhardt’s decision to play it straight. Once he himself had talked with the Russians at his command post, he interrupted the inevitable toasts and photographs to report the news to the V Corps commander. General Huebner in turn told Reinhardt to proceed with arrangements for a formal meeting of division commanders the next day, 26 April, and of corps commanders on the 27th. Since nobody yet had any specific information on the site of Lieutenant Kotzebue’s meeting, the formal linkup celebrations would be held at Torgau.

General Reinhardt met General Rusakov, the man of many welcomes, on the east bank opposite Torgau at 1600 on the 26th. Camaraderie, photographs, toasts, dancing in the street, and a hastily assembled feast with a main dish of fried eggs were the order of the day. General Huebner conducted a second ceremony on the 27th with his opposite, the commander of the 34th Russian Corps, and General Hodges a third on the 30th with the commander of the First Ukrainian Army. The American, British, and Soviet governments officially announced to the world at 1800 on the 27th that east and west had met on the Elbe at Torgau.

In the meantime, somebody at last had remembered to do something about Lieutenant Kotzebue, Major Craig, and their men waiting on the east bank upstream near Kreinitz. Late on the 26th, a patrol brought them the news that history had passed them by. On the same day, Lieutenant Shank of the 104th Division, who also had had a close brush with history, returned to Torgau, this time actually to meet the Russians he had failed to wait for long enough two days before.

A few problems of coordination with the Russians remained on the northern and southern portions of the front. The British Chiefs of Staff were particularly concerned lest the Russians intended the Elbe as a stopping point in the north as well as the center of the front. A Russian drive to the Elbe would jeopardize the British drive to the Baltic. Urging General Eisenhower to make the distinction clear, the British Chiefs also pointed out that by seeking to halt on a well-defined geographical line, Eisenhower might be forgoing remarkable political advantages to be gained by liberating Prague and much of the rest of Czechoslovakia. If possible without detracting from the main drives to the Baltic and into Austria, they believed the Allies should exploit any opportunity to drive deep into Czechoslovakia.

In the course of passing that view to General Eisenhower, General Marshall remarked: “Personally and aside from all logistic, tactical or strategical implications I would be loath to hazard American lives for purely political purposes.”14 Right or wrong from a political standpoint, the decision was in keeping with the U.S. military policy followed generally throughout the

General Hodges meets the Russians at the Elbe

war—to concentrate everything on achieving military victory over the armed forces of the enemy.15

First priority, Eisenhower told Marshall, was to be accorded the drives to the Baltic and into Austria. The thrust to the Baltic, he said, was to forestall Russian entry into Denmark (a departure from the stated military policy which no one officially remarked); the thrust into Austria to deny a National Redoubt. If additional means should be available, he intended to attack enemy forces that still might be holding out in Czechoslovakia, Denmark, and Norway. Both the latter, he believed, should be the province of the Allies; but the Red Army was in perfect position to clean out Czechoslovakia and certainly to reach Prague in advance of U.S. troops. “I shall not attempt any move I deem militarily unwise,” he assured Marshall, “merely to gain a political prize unless I receive specific orders from the Combined

Chiefs of Staff.”16 As in the case of going to Berlin, such orders never came.

In an even fuller explanation of plans to the Russians, General Eisenhower on the last day of April allayed British fears about lower reaches of the Elbe. In the north, the Supreme Commander noted, he intended to clear the Baltic coast as far east as Wismar and build a line south to Schwerin, thence southwest to Doemitz on the Elbe, 23 miles downstream from Wittenberge. From headwaters of the Mulde River southward, he intended to hold a line approximately along the 1937 frontier of Czechoslovakia, though he might advance as far into Czechoslovakia as Karlsbad, Pilsen, and České Budějovice. Farther south he planned to halt in the general area of Linz.

The Russians accepted these proposals, but four days later, on 4 May, when General Eisenhower said he was willing not only to advance to the Elbe in the vicinity of Dresden but also to clear the west bank of the Vltava within Czechoslovakia, which would bring his forces in the center as far east as Prague, generally on a line with those in the south at Linz, the Red Army Chief of Staff strongly objected. To avoid “a possible confusion of forces,” he asked that the Allies confine their advance in Czechoslovakia to the Karlsbad–Pilsen line as earlier stated. He added pointedly that the Russians had stopped their advance toward the lower Elbe in accordance with Allied wishes.

General Eisenhower promptly agreed to the Russian request.17

The End in Berlin

Linkup by the enemies of the Third Reich was but one more thorn in a bristling crown of troubles pressing hard on Adolf Hitler’s brow. Indeed, amid the welter of sad tidings pouring into the Führerbunker, the meeting on the Elbe may have passed unremarked.

Since Hitler’s decision on the 22nd to stand and die in Berlin, an air of aimless resignation had hung over the bunker, relieved more and more rarely by some vain flurry of hope. It was common knowledge among the sycophants in the bunker that Hitler intended suicide, as did Eva Braun. Late on the 26th, Russian artillery fire began to fall in the garden of the Reich Chancellery above the bunker, reminder enough for any who still might have doubted that the end was near. Yet the Führer’s military chiefs, Keitel and Jodl, even though now removed from Hitler’s presence, persisted either in coloring their reports on the military situation or in refusing to face the facts themselves.

General von Manteuffel, who earlier had been transferred from the west for the twilight of the campaign in the east, told Jodl late on the 27th that anyone who wanted a true picture had but to stand at any crossroads north of Berlin and observe the steady stream of refugees and disheartened troops clogging the roads to the rear. What the soldier could do had been done, Manteuffel insisted; now the time had come for

political action, for negotiations with the Western Powers.18

Yet both Keitel and Jodl could persist in their belief that more still might be done. Relieving the army group commander north of Berlin, they ordered General Student, commander of the First Parachute Army, to fly from the Netherlands to assume command.

On the 28th, grim news poured into the bunker in a torrent. Italian partisans, Hitler learned, had arrested his erstwhile partner, Mussolini, and there were distressing rumors of army leaders in Italy negotiating surrender. He learned too of the uprising in Munich. On that day also, telephone communications with OKW failed.

The 29th was grimmer still. Hitler himself would not be notified until the next day, but on the 29th the last thin hope of relieving Berlin evaporated when the turnabout attack of General Wenck’s Twelfth Army stalled near Potsdam, seventeen miles southwest of the capital. Only some 30,000 men of the Ninth Army south of Berlin had escaped Russian encirclement; so exhausted were they, so depleted their arms and ammunition, that they would be of no help to Wenck.

Mussolini and his mistress, Hitler learned, had been executed the day before and strung up by their heels. Yet the most crushing blow was the word that Heinrich Himmler had turned traitor. As with Goering, Hitler expelled Himmler from the party and stripped him of all claim to the succession. When his fury had passed, he drew a will and testament appointing Admiral Doenitz as head of the German state and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. Then, before daylight the next morning, he married Eva Braun.

Field Marshal Keitel finally sent a message by radio early on the 30th telling of the failure of Wenck’s Twelfth Army, in effect admitting that all hope was gone. Although the message may never have reached the bunker, Hitler apparently already had concluded that it was time to die. He spent much of the morning saying farewells to his staff, seemingly unmoved by the news that Russian troops were little more than a block away, then in midafternoon retired with Eva Braun to his suite.

Eva Braun killed herself by biting on a cyanide capsule. Hitler shot himself with a pistol. In accordance with prior instructions, members of the household staff burned the bodies outside the bunker.19

News of the Führer’s death was slow to emerge. Most likely those in the bunker delayed in order to await the outcome of a Goebbels-inspired attempt to negotiate the surrender of Berlin in exchange for safe passage of those in the bunker. When the Russians predictably declined any accommodation, word went out at last—more than twenty-four hours after the suicide—that Hitler was dead. Admiral Doenitz announced it publicly by radio that evening, 1 May, in the process giving the impression that Hitler had died a hero’s death.

That same day Goebbels and his wife, after poisoning their six children, arranged their own deaths at the hands of an SS guard. Three of Hitler’s military entourage also killed themselves. The others tried to escape. Few made it.

The Drive to the Baltic

As these melodramatic events occurred, two major Allied offensives were continuing, one by Montgomery’s 21 Army Group to clear northern Germany and the Netherlands, the other by Devers’s 6th Army Group and the Third Army into Austria.

The 21 Army Group’s offensive evolved from the bridgehead established over the Rhine near Wesel. While the First Canadian Army on the left drove generally north to reach the IJsselmeer and the North Sea, the Second British Army attacked northeast to seize the line of the Elbe from Wittenberge to the sea. Those goals achieved, the Canadians were to turn west to clear the Netherlands and east to sweep the littoral from the Dutch border to the estuary of the Weser River. The British were to attack across the Elbe to capture Hamburg and make a 45-mile drive to the Baltic in the vicinity of Lübeck.20

Benefiting much as had the First and Ninth U.S. Armies from the great gap created in the German line by encirclement of Army Group B in the Ruhr, the British south wing alongside the Ninth Army made the most rapid gains. There the 8 Corps had a four-day brush with contingents of Wenck’s Twelfth Army near Uelzen but reached the Elbe the next day, 19 April, opposite Lauenberg, some thirty miles upstream from Hamburg. Another corps in the center reached the Elbe opposite Hamburg four days later on the 23rd. Both this corps and another on the left that was advancing on the great port of Bremen fought against the essentially makeshift force, Army Blumentritt, formed in early April as a component of OB NORDWEST, the new command under Field Marshal Busch which had been created as the Allied armies threatened to split the Western Front.21 Strengthened by sailors fighting as infantry, the Germans made a stand for a week in front of Bremen, but by nightfall of 26 April the British were in full control of the city.

The First Canadian Army at the same time was facing the remains of General Student’s First Parachute Army and the Twenty-fifth Army, which was subordinate to OB NEDERLANDER, the new command under General Blaskowitz who formerly had headed Army Group H. Comprising two of the more cohesive forces remaining to the German Army in the west, the troops drew added strength from readily defensible positions along one canal or river after another. Contingents of one Canadian corps nevertheless reached the North Sea near the northeastern tip of the Netherlands on 16 April, thereby splitting the German front. Another corps on the 14th took Arnhem on the Neder Rijn, an objective that had eluded British troops in the preceding September’s big airborne attack, and on the 18th ended a 40-mile trek to the IJsselmeer.

One corps turned east to clear the

coast between the Dutch border and the Weser, but little reason remained for the other to make the planned assault to erase the Germans trapped in the western portion of the Netherlands. If the Canadians attacked, the Germans in all probability would flood the low-lying countryside, increasing the suffering of a Dutch population already facing a food shortage that was close to famine. Even the Nazi high commissioner in the Netherlands, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, had by early April become concerned that a catastrophe was in the making. Word that Seyss-Inquart might be amenable to a relief operation reached the Canadians in mid-April, resulting in conferences with the Germans that led to an agreement for the Allies to provide food for the Dutch by land, sea, and air. Airdrops began on 28 April while negotiations were still going on.22

During the conferences, General Eisenhower’s representative tried to persuade Seyss-Inquart to agree either to a truce or to unconditional surrender. Seyss-Inquart refused on the grounds that it was the duty of the Germans in the Netherlands to fight until ordered to do otherwise by the German government. As Dutch relief operations got underway, a lull not unlike a truce nevertheless settled over the front.23

For the British attack across the Elbe to reach the Baltic, General Eisenhower provided assistance by General Ridgway’s XVIII Airborne Corps with three U.S. divisions. Although the corps was attached to the Second British Army for the operation, the Ninth Army provided administrative and support services. Under the British plan, the 8 Corps was to make an assault crossing of the Elbe, whereupon the 12 Corps and the XVIII Airborne Corps were to cross into the bridgehead, the former to mask and later capture Hamburg, the latter to clear additional bridging sites upstream and protect the right flank of the 8 Corps in a northward drive to the Baltic.24

The rapid deterioration of German forces everywhere on the Western Front prompted Field Marshal Montgomery to advance the date of the river crossing two days, to 29 April. It also prompted General Ridgway to propose that instead of waiting six or seven days to cross British bridges, the XVIII Airborne Corps make its own assault crossing before daylight on 30 April. The commander of the Second Army, General Dempsey, approved.

General Ridgway’s problem was to get an assault force ready in time. Although one division, the 8th, had arrived by nightfall of the 28th from mop-up operations in the Ruhr, its regiments were concentrated near the British crossing site in keeping with the original plan. Of the 82nd Airborne Division, assembling near the bridge sites reserved for the U.S. corps, only a battalion had arrived by dawn of the 29th, and a full regimental combat team was not scheduled to arrive until late afternoon of the same day, a few hours before the time for the assault. A third division, the 7th Armored, was not to complete its move until the 30th.

In the interest of speed and in a belief

Map 8: Drive to the Baltic, 29 April-2 May 1945

that resistance would be light, Ridgway named the airborne division for the assault even though at the start only one battalion of the 505th Parachute Infantry would be available. To provide a ready follow-up force, he attached four battalions of the 8th Division to the 82nd.

Following an almost unopposed crossing by British commandos near Lauenburg before daylight on the 29th, the battalion of the 505th’s paratroopers moved silently in assault boats across the sprawling Elbe at Bleckede, six miles upstream from Lauenburg, at 0100, 30 April. (Map 8) As rain mixed with snow prompted the Germans on the far bank to seek cover, only an occasional flurry of small arms fire swept the river.

The paratroopers fanned out against sporadic resistance, though artillery fire began to fall in heavy volume at the crossing site. The shelling harassed succeeding waves and hampered engineers constructing a heavy ponton bridge, but a 1,110-foot bridge was nevertheless ready for traffic before dark on the first day, fifteen hours after work had begun.

The next day, 1 May, the bridgehead expanded rapidly. Having crossed a British bridge at Lauenburg, the 6th

In the Austrian alps a nest of resistance confronts men of the 103rd Division

British Airborne Division was attached to General Ridgway’s command to form the left wing of the corps. Four battalions of the 8th Division and an additional parachute infantry regiment of the 82nd participated in the day’s attacks amid increasing indications that all resistance was about to collapse. By the end of this second day, the American bridgehead was six miles deep, contact was firm with the British on the left, and a second bridge was in operation eight miles upstream from Bleckede. Contingents of British armor to assist the British airborne division and a combat command of the 7th Armored Division to help the 82nd were crossing the river.

On 2 May, as news of Hitler’s death spread, the enemy’s will to fight disappeared. In rare instances was a shot fired. The problem became instead how to advance without running down hordes of German soldiers and civilians who appeared to have only one goal: to get out of the way of the Russians.

With attached armor, the 82nd Airborne Division moved east to Ludwigslust and southeast along the Elbe to Doemitz to anchor the 21 Army Group’s right flank on the line General Eisenhower

had specified to the Russians. The 8th Division drove forty-five miles to the northeast to occupy Schwerin. While British troops before Hamburg began negotiations for the fire-gutted city’s surrender and while a British armored division entered Lübeck without a fight, the 6th British Airborne Division dashed all the way to Wismar on the Baltic. The drive sealed off the Jutland peninsula, trapping German forces in the nation’s northernmost province and barring the way to Denmark. Two hours later the first Russian troops arrived.

Piecemeal Surrenders

The second of the continuing Allied offensives, a prolongation into Austria of the drive through southern Germany by the 6th Army Group and the Third Army, also became closely involved in the growing German dissolution. Hardly were the first troops across the Austrian frontier when the news broke that on 29 April the German command in Italy had surrendered. The capitulation was effective at noon on 2 May and included the Austrian provinces of Vorarlberg, Tirol, Salzburg, and part of Carinthia (Kaernten), the areas into which troops of the 6th Army Group were moving.25

On the same day, 2 May, Admiral Doenitz, new head of the Third Reich, convened his advisers in a headquarters established in the extreme north of Germany. Anxious to end the bloodshed, Doenitz just as fervently wanted to save as many German soldiers and civilians as possible from the grasp of the Russians. Aware that agreements between the Western Powers and the Soviet Union precluded his surrendering all to the Western Allies alone, he believed that the only chance of saving more Germans lay in opening the front in the west while continuing to fight in the east, meanwhile trying to arrange piecemeal surrenders to the Allies at the level of army group and below.

As Doenitz surmised, the way was open for such surrenders. Basing their conclusions on indications reaching General Eisenhower’s headquarters in mid-April that German commanders in Norway, Denmark, and the larger north German cities might be induced to surrender, the Combined Chiefs of Staff on 21 April had notified the Russians that surrender of large formations was a growing possibility. They suggested that Britain, the Soviet Union, and the U.S. be represented on each front in order to observe negotiations for surrender. The Soviets had promptly agreed.

Word went out from Doenitz’s headquarters during 2 May to commanders facing the Russians in the north to move as many men as possible behind the line Wismar–Schwerin–Ludwigslust–Doemitz and to exploit any opportunity to negotiate local surrenders to the Allies.26 General der Infanterie Kurt von Tippelskirch, commander of the Twenty-first Army, complied that afternoon, contacting General Gavin, commander of the 82nd Airborne Division, in Ludwigslust. Tippelskirch surrendered his command unconditionally, though in deference to the Russians, Gavin specified

that the capitulation was valid only for those troops who passed through Allied lines.27

A formal surrender was hardly necessary in any case. By the afternoon of 2 May the bulk of the German troops and their commanders were falling over themselves to get into Allied prisoner-of-war enclosures. That the Germans in the area north of Berlin were squeezed into a corridor only some twenty miles wide between Russian and Allied troops hardly could have eluded anybody. Great columns of motor vehicles, horse-drawn carts, foot troops, even tanks, moved in formation to surrender. Other soldiers straggled in individually, many with their women and children and pitiful collections of personal belongings. To the 8th Division alone at Schwerin more that 55,000 Germans surrendered that day.

The next day, 3 May, Tippelskirch himself entered an enclosure of the 82nd Airborne Division along with some 140,000 other Germans of the Twenty-first Army, while farther north, at Schwerin, some 155,000, mainly of the Third Panzer Army, including the commander, General von Manteuffel, surrendered to the 8th Division. The headquarters of the army group controlling these two armies apparently disintegrated. Having narrowly escaped capture when men of the 8th Division entered Schwerin, the newly assigned commander, General Student, went into hiding but would be apprehended later in the month.

As Tippelskirch surrendered on 2 May, Admiral Doenitz was sending emissaries to Field Marshal Montgomery with a view to surrendering all German forces remaining in northern Germany. Under instructions from General Eisenhower, Montgomery on 4 May accepted the unconditional surrender effective the next day of all Germans in the Netherlands, the Frisian Islands, Helgoland, and all other islands, north Germany, and Denmark. (Norway, Eisenhower ruled, would constitute a political rather than a tactical surrender and thus would have to await negotiations at which Russian representatives would be present.) Although Montgomery refused to accept withdrawal into his zone of German civilians or military formations still opposing the Russians, he agreed to accept individual soldiers. Since the bulk of those opposing the Russians already had entered Allied lines in any case, the restriction made little difference.

General Wenck’s Twelfth Army and the 30,000 survivors of the Ninth Army meanwhile entered negotiations with the Ninth U.S. Army on 4 May in hope of gaining approval for troops and a mass of civilians accompanying them to cross the Elbe and surrender. The Ninth Army’s representatives agreed to accept the troops so long as they brought their own food, kitchens, and medical facilities, but forbade the civilians to cross. Actually, the Ninth Army’s troops imposed no ban on civilians. On a catwalk spanning the ruins of a railroad bridge, on ferries, boats, and rafts, or by swimming, some 70,000 to 100,000 men of the Ninth and Twelfth Armies got to the west bank of the Elbe.28

In Austria, first indications that Field Marshal Kesselring might be ready to surrender his Army Group G and the Nineteenth Army developed on 3 May when General Devers learned through SHAEF that Kesselring had asked the German command in Italy to whom he should surrender.29 On the same day Kesselring asked Admiral Doenitz for authority to surrender, which Doenitz granted.

As Kesselring began his overtures, the war in Austria went on amid an aura of unreality—not really war, yet not quite peace. There were three main drives, that of the French into the Vorarlberg, that of General Patch’s Seventh Army toward Landeck and Innsbruck, and that of General Patton’s Third Army toward Linz.

The 13th Armored Division of General Walker’s XX Corps in the Third Army’s center was the first of Patton’s troops to reach the Austrian frontier in strength, doing so on the first day of May along the Inn River opposite Braunau (Hitler’s birthplace). The next day, as divisions of the XX Corps bridged the Inn at three places, in the process capturing both Braunau and Passau, the latter at the juncture of the Inn with the Danube, a new order and another that was pending forced General Patton to alter and broaden his plan of attack.

The first order was the boundary change according Salzburg to the Seventh Army. The change pinched out the III Corps along that part of the Inn River that flows inside Germany, ending participation of General Van Fleet’s command in the fighting. The second was based on a plan to withdraw headquarters and special troops of the First Army from the line, a first step in projected deployment of General Hodges’ command to the Pacific. As part of the plan, General Huebner’s V Corps on 2 May began relieving northernmost units of General Irwin’s XII Corps along the Czechoslovakian frontier, a preliminary to transfer of the V Corps two days later to the Third Army. Irwin’s corps was thus freed to join the drive on Linz down the north bank of the Danube. The scene was also prepared for an operation to which General Eisenhower had alerted the Russians a few days earlier, an advance of up to forty miles inside Czechoslovakia to Karlsbad, Pilsen, and České Budějovice.30

Under the new arrangement, Walker’s XX Corps was to press from its bridgehead over the Inn to the line of the Enns River southeast of Linz while the right wing of Irwin’s XII Corps moved along the north bank of the Danube to capture Linz. Irwin’s left wing meanwhile was to attack into the southwestern corner of Czechoslovakia toward Klatovy and České Budějovice, while Huebner’s V Corps advanced eastward to take Karlsbad and Pilsen.

The divisions of the XX Corps drew only occasional enemy fire as they moved swiftly to reach the Enns River on 4 May and there awaited the Russians. The 11th Armored Division of the XII Corps at the same time reached a point only a few miles north of Linz, where an official of the city offered to surrender on condition that the German garrison be allowed to march east against the Russians. The armor refused that proviso, and a column advanced swiftly the next morning to

find a bridge across the Danube intact, the city almost devoid of Germans. Another column uncovered more evidence of German atrocities in concentration camps near Mauthausen and Gusen. The armor then moved to the Linz–České Budějovice highway to join neighbors of the XX Corps in a watch for the Russians.

For the rest of the XII Corps and for the V Corps, the drive into Czechoslovakia was at first an anticlimax. The fighting was unreal, a comic opera war carried on by men who wanted to surrender but seemingly had to fire a shot or two in the process. The land, too, was strange, neither German nor Czech. The little towns near the border, with their houses linked by fences and their decorated arches over the gates, had the look of Slavic villages, but the population was unquestionably hostile. This country was the disputed Sudetenland.

The monotony—an occasional burst of small arms fire along roads, a rocket from a Panzerfaust at a roadblock, a stray round of artillery fire in fields—was broken for the 90th Division on 4 May when out of the wooded hills emerged an old foe of the Third Army, the 11th Panzer Division. This time the panzers were bent not on attack but on surrender. With an odd conglomeration of tanks and other vehicles, the remnants of the division marched with their commander, General von Wietersheim, to prisoner-of-war cages.

Two days later General Patton sent the 4th Armored Division through the 90th in the hope that General Eisenhower would agree to an advance down the valley of the Vltava River to Prague, but approval never came. Patrols had advanced as far as Pisek on a tributary of the Vltava northwest of České Budějovice when the armor came to a halt.

On 6 May men of the 2nd and 97th Divisions and a new unit, the 16th Armored Division (Brig. Gen. John L. Pierce), came upon an entirely new scene. Early in the day the armor began unsuspectingly to pass through the infantry along the highway leading to Pilsen. Past silent, undefended forts of Czechoslovakia’s western fortifications, the “Little Maginot Line,” again untested in battle as it was after the Munich Pact, the troops burst suddenly from the Sudetenland with its apathetic, sometimes sullen German sympathizers into a riotous land of colorful flags and cheering citizenry.

As if they had stepped across some unseen barrier, the men found themselves in a new land of frenzy and delight. War and nonfraternization lay behind. It was Paris all over again, on a lesser scale and with different flags, but with the same jubilant faces, the same delirium of liberation. Past abandoned antiaircraft guns that had protected the big Skoda industrial complex on the outskirts of the city, the armor raced into Pilsen. “Nazdar! Nazdar!” the people shouted.

Except for the 1st Division, advancing on Karlsbad, the V Corps had joined the growing list of American units for which the shooting war was over. It was almost over for the 1st Division as well. Karlsbad surrendered by telephone early the next afternoon, the staff of the opposing Seventh Army the day after that.

In the Tirol, in the meantime, the Alpine terrain restricted the forces the Seventh Army could employ in drives on Innsbruck and Landeck to two divisions. Although only a few Germans resisted,

Austrian civilians line a street in Innsbruck to welcome American troops

they drew added strength from their positions in the precipitous, narrow Alpine passes. Snow mixed with freezing rain and great drifts of the preceding winter’s snow also slowed the advance. Nor were the men and their commanders eager, in view of the approaching end of the war, to take undue chances.

Relieving the armor of the VI Corps before the Mittenwald Pass leading to Innsbruck, the 103rd Division during 1 May established telephone contact with the German garrison in the Tirolean capital, but the lines went out before surrender negotiations could be completed. Further negotiations were underway when, during the afternoon and evening of 2 May, Austrian partisans seized control of Innsbruck. Although the partisans begged for American entry lest SS troops counterattack, the 103rd Division still had to fight through occasional German delaying groups to get to the city. During midmorning of 4 May, in a driving snowstorm, the Americans entered.

From Innsbruck, General McAuliffe sent his 411th Infantry hurrying southward in trucks to gain the Brenner Pass. In hope of speeding the advance over a

Czechoslovakian villagers welcome tank crew of the 6th Armored Division

treacherous Alpine road, McAuliffe sent the convoy forward the night of 3 May with headlights blazing. Without firing a shot, the 411th Infantry took the town of Brenner just before 0200, 4 May, while a mounted patrol continued through the pass and across the Italian frontier to Vipiteno, there making contact at 1051 with reconnaissance troops of the 88th Infantry Division. A Seventh Army that had invaded Sicily long months before, then had left the fighting in the Mediterranean to the Fifth Army while detouring by way of southern France to Germany, joined hands with those men who had fought up the long, mountainous spine of Italy. That the troops belonged to the VI Corps was appropriate, for long ago the VI Corps had fought in Italy in a besieged beachhead at Anzio.

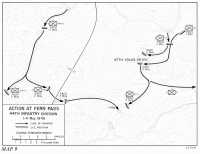

At the Fern Pass, where men of the 44th Division relieved other contingents of the armor of the VI Corps, a 300-man German detachment staunchly defended a serpentine highway blocked by deep craters and a landslide. A battalion of the 71st Infantry began to attack the

Map 9: Action at Fern Pass, 44th Infantry Division, 1–4 May 1945

position early on 1 May. (Map 9) Anticipating difficulty getting through the pass, the division commander, General Dean, at the same time sent a reinforced company on a circuitous 40-mile outflanking maneuver, back almost to the Oberjoch Pass, then southwestward up the valley of the Lech River to another route—more a trail than a road—leading across a high mountain range to the vicinity of Imst, some eight miles behind the Fern Pass.

The company was still bucking fresh snow and old drifts when around midday on 2 May the commander of the 71st Infantry sent a second battalion to help in reducing the defenses at the Fern Pass. As the battalion was moving up, five Austrian partisans appeared with an offer to guide the men along a little-known secondary road that would put them in rear of the pass. Led by the Austrians, the battalion moved swiftly along a road that cut through forests and over a steep crest south of the Fern Pass. The men seized the town of Fernstein behind the pass, then before dark, came upon the Germans at the pass from the rear. Resistance collapsed.

The next day men of the 44th Division pushed on foot toward Imst, to make contact there with the reinforced

company that two days before had begun the wide outflanking maneuver; but resumption of a full-scale advance to Landeck and the Resia Pass beyond had to await repair of the road through the Fern Pass and the coming of tanks and other vehicles. It was this delay that prompted the commander of the First French Army, General de Lattre, to try to beat the Americans into Landeck by way of the Arlberg Pass.31

Unaware that de Lattre had begun a race for Landeck, the 44th Division was in no rush, particularly not in view of other developments on 4 May. Through the division’s lines at Imst that day passed emissaries of General Brandenberger’s Nineteenth Army on their way to open negotiations for surrender. Not far away, other emissaries on the night of 4 May approached troops of the 3rd Division of the XV Corps to begin arrangements for capitulation of General Schulz’s Army Group G.

The Nineteenth Army surrendered in keeping with a detailed scenario worked out at headquarters of the VI Corps. The enemy commander, Brandenberger, was to present himself at the Landsrat in Innsbruck at a specified time on 5 May. The scenario spelled out how Brandenberger was to be met, that no salutes or handshakes were to be exchanged, even the times when conferees would stand and when they would be seated.

Except that Brandenberger reached the scene some minutes late, all went according to plan. Shortly before 1500 the VI Corps commander, General Brooks, afforded Brandenberger and his staff a brief period in which to confer privately upon condition that they return to the conference room at 1500. At that time the Ninteenth Army surrendered unconditionally, effective at 1800 the same day.32

A regiment of the 44th Division meanwhile had resumed the advance on Landeck when in midmorning of the 5th, the German commander in the region suggested a truce pending the outcome of Brandenberger’s negotiations. On the condition that the arrangement include evacuation of Landeck, General Dean agreed, and a battalion of the 44th Division occupied the town that afternoon, in the process unwittingly thwarting General de Lattre’s effort to reach Landeck first. Not until two days later, on the 7th, would anyone bother to proceed to the Resia Pass, which de Lattre so earnestly wanted to attain. At 1900, 7 May, the 44th Division established contact there with contingents of the 10th Mountain Division.

In the broader surrender of Army Group G, an element of surprise was present in that General Devers had anticipated, on the basis of Field Marshal Kesselring’s query as to whom he should surrender, that Kesselring would be surrendering his entire command. Kesselring had intended to do that, but the new German government had granted authority only for Army Group G, not for those troops opposing the Russians in Austria and the Balkans, which by Hitler’s order of 24 April were at that point under Kesselring’s command.33

Thus it was that the commander of the First Army, General Foertsch, representing the commander of Army Group G, General Schulz, appeared the night of

4 May before troops of the XV Corps. The 3rd Division commander, General O’Daniel, accompanied the delegation to an estate at Haar, near Munich, where negotiations began on the rainy fifth day of May. Among those present, in addition to Devers, were Patch of the Seventh Army and Haislip of the XV Corps. No representative of the First French Army was included.

Although General Foertsch made no objection to terms, he felt impelled to point out that even with the best of intentions, it would be difficult for the Germans to comply with some provisions in the time allowed. Such was the state of German communications, for example, that many hours might pass before all German troops received word of the surrender. He also asked if the Allies would hand over prisoners to the Russians.

With these points answered, usually noncommittally, General Devers stated firmly that General Foertsch’s action was no armistice; it was unconditional surrender.

“Do you understand that?” he asked.

Foertsch stiffened. After nearly a minute, he responded.

“I can assure you, sir,” he said, “that no power is left at my disposal to prevent it.”

At approximately 1430, representatives of both sides signed the terms to become effective at noon the next day, 6 May.34

The surrender affected all German troops between Army Group G’s eastern boundary near the Austro-Czech border and the western border of Switzerland, thus excluding General von Obstfelder’s Seventh Army in Czechoslovakia, which a week earlier had been subordinated directly to OB WEST, but including Brandenberger’s Nineteenth Army and its shadow appendage, the Twenty-fourth Army, even though Brandenberger, apparently without the knowledge of General Foertsch, had begun negotiations ahead of Foertsch. The duplication probably resulted from Kesselring’s authorizing both army group and army commanders to enter negotiations, from a breakdown in communications within Army Group G, or from the on-again, off-again nature of the Nineteenth Army’s subordination to Army Group G during the preceding month, this last apparently having depended either on the whim of Kesselring or on the state of communications among the three headquarters. Troops of the Nineteenth Army, in any event, generally observed the earlier effective hour of surrender specified in Brandenberger’s negotiations with the VI Corps.

The same was not true of the shadow force, the Twenty-fourth Army, though only partially through the fault of the Germans. Representatives of the commander of the force, General der Infanterie Hans Schmidt, had approached the French at noon on 4 May with a request for terms of surrender, but before word could reach General de Lattre, the French commander received a request from the 6th Army Group to send a parliamentary to the VI Corps to treat with the Nineteenth Army. When General Schmidt’s delegation reached de Lattre’s headquarters with word that Schmidt had authority to treat independently, de Lattre theorized that the French had been invited to participate in the Nineteenth Army’s surrender because

soldiers of that army faced both French and Americans but that he was free to treat alone with Schmidt since only French troops faced the Twenty-fourth Army.35

By the time General Schmidt’s emissaries returned from contacting the French, Schmidt had learned that Army Group G was surrendering to the 6th Army Group. Deciding against presenting himself to de Lattre, Schmidt sent instead a letter noting the broader surrender and suggesting that the French get in touch on the matter with the 6th Army Group.

Shocked by the “insolence” of Schmidt’s letter, General de Lattre demanded that General Devers send on to him any plenipotentiaries from the Twenty-fourth Army who might approach American forces. He intended to continue hostilities, he said, until the moment German representatives presented themselves at his headquarters.

General Devers’s chief of staff replied that Army Group G had surrendered in entirety effective at noon on 6 May, including the troops opposing the French. Devers’s orders were that all troops of the 6th Army Group stop in place and cease fighting immediately, the word to be transmitted without delay to both Germans and French.

De Lattre was not satisfied. If the Nineteenth Army as a part of Army Group G had surrendered individually with an effective hour different from that for the entire army group, then the same conditions should be applied, he reasoned, to the Twenty-fourth Army. Failing to take cognizance of the fact that Schmidt’s command was attached as a subordinate unit to Brandenberger’s, he rationalized that if the Twenty-fourth Army had been included in the surrender, it would have been mentioned by name. Defying the directive from Devers, de Lattre sent a courier to General Brandenberger to demand that he send Schmidt to surrender to the French. In the meantime, he said, the French would continue to fight.

Hostilities ostensibly were continuing in the French sector when late on 6 May General Devers sent a liaison officer to explain to de Lattre how, even as negotiations had been underway with Brandenberger, a delegation from Army Group G had arrived to surrender the entire command. De Lattre was still not to be placated. Ignoring the fact that the Twenty-fourth Army bore the name of an army command purely for purposes of deception, he pointed out that neither in the surrender of Army Group G nor of the Nineteenth Army had the Twenty-fourth Army been specifically mentioned. Besides, he maintained, not without logic, if the Germans on his front were included in Army Group G’s surrender, then the First French Army should have been represented at the ceremony.

When the liaison officer asked him at this point to sign his name to the surrender document, de Lattre refused on the grounds that General de Gaulle had named him as an official representative of the French government to accept the over-all German surrender and that a governmental representative should not affix his signature to an operational document originating in the field. In declining,