Chapter 8: Breakout: 17–19 August

Eager to take advantage of the weakness of the German defenders and their slow response to ANVIL, Truscott sent his three divisions inland. He wanted the bulk of the 3rd Infantry Division to continue its advance on 17 August, first pushing its left flank westward to the line of the Real Martin and Gapeau rivers, both running generally north to south under the western slopes of the Maures.1 Once there, the division’s left was to hold until the French II Corps, on or about 20 August, could move up to continue the drive toward Toulon. The rest of the 3rd Division was to assemble in the Le Luc–Gonfaron area and strike westward along the axis of Route N-7 to Brignoles, thirteen miles beyond Le Luc, and to St. Maximin, eleven miles farther and twenty-five miles directly north of Toulon (Map 7). Meanwhile, the 45th Division was to dispatch one regimental combat team northwest from Vidauban to the Barjols area, about eleven miles north of St. Maximin. CC Sudre (CC1)2 of the 1st French Armored Division was also to head westward to the St. Maximin–Barjols line, using both N-7 and secondary roads between the 3rd and 45th Divisions.

On the VI Corps’ eastern flank, scattered forces of Task Force Butler were to assemble at Le Muy on the 17th, reorganize in accordance with preassault plans, and start probing northwest on the 18th. The 36th Division was to relieve the 1st Airborne Task Force in the Le Muy–Les Arcs region and then, leaving one regiment along the coast to protect VI Corps’ right flank, be prepared to follow TF Butler. After assembling in reserve at Le Muy, the airborne force was to move eastward to relieve the regiment that the 36th Division had left behind.

In brief, Truscott’s plans provided for three mutually supporting maneuvers: first, a general pressure westward along the coast toward Toulon; second, an outflanking of Toulon to the north (possibly followed by an advance westward toward the Rhone); and third, a drive northwest by TF Butler and the 36th Division. On the

Map 7: Breakout From the Blue Line, 17–19 August 1944.

left, the advance westward to the Real Martin and Gapeau rivers would secure a base area for the attack on Toulon and Marseille by the French II Corps. The push in the center to the St. Maximin–Barjols line would protect the French northern flank and threaten the Rhone valley. Finally, the advance northwest by TF Butler and the 36th Division would greatly complicate German efforts to hold the lower Rhone and would pose a serious threat to a subsequent German withdrawal from the area.

German Plans

The German commanders spent the night of 16–17 August assessing their options.3 With the failure of the LXII Corps’ 148th and 242nd Divisions to halt or even slow down the invasion and with the collapse of the German counterattack in the Les Arcs area on the 16th, General Wiese, the Nineteenth Army commander, concluded that his major problem was no longer mounting an immediate, ad hoc assault but rather establishing a defensive line that would give his combat forces still west of the Rhone time to transfer to the east side of the river, either for defensive purposes or to build up the strength needed to launch a substantive counteroffensive. Furthermore, he decided that any new attempts to rescue the LXII Corps headquarters would be fruitless and could only disrupt orderly redeployments. However, on the basis of inadequate intelligence, Wiese also estimated that the Seventh Army posed no immediate threat to the region west of Toulon, allowing him to move units east from the Marseille area for defensive purposes and replace them with forces from west of the Rhone.

Late on the afternoon of 16 August Wiese directed General Baessler, commanding the battered 242nd Division, to build up delaying positions along the line of the Real Martin and Gapeau rivers from the coast inland for thirty miles northeast to Vidauban. (Wiese did not yet know that Vidauban was already lost.) To help hold this sector, he pulled three battalions of the 244th Division from positions west of Toulon and assigned the units to Baessler. About the same time, Wiese directed the 148th Division, now cut off on the eastern side of the Allied landing area, to employ whatever units it could find to halt what he believed to be an Allied drive along the coast toward Cannes. At this point, he thus had no clear idea of specific Allied objectives inland.

Pressing Westward

The rapid Allied advance westward soon made Wiese’s defensive plans obsolete.4 On the left of the 3rd Division, the 7th Infantry and the French African Commando Group moved up to the Real Martin and Gapeau rivers on the 17th and 18th, encountering

some stubborn but scattered resistance from units of the 242nd Division. On the 18th and 19th the French commandos and elements of the French 1st Infantry Division relieved the 7th Infantry in the coastal sector and continued the drive west.

In the 3rd Division’s center the 15th Infantry, following the 3rd Provisional Reconnaissance Squadron,5 reached the town of La Roquebrussanne on 18 August, ten miles south of Brignoles. The 30th Infantry, charged with seizing Brignoles, started out on 17 August with a firefight at Le Luc, but part of the regiment and elements of CC Sudre cleared the town after a four-hour action. Meanwhile, the main bodies of the two Allied units continued westward along Route N-7 and lesser roads, nearing Brignoles late on the 18th. After a battle that lasted until the next morning, the area fell to the French and American attackers. Farther north, the 157th and 179th Infantry, 45th Division, headed out of the Le Luc–Vidauban area late on the 17th, encountered little resistance, and halted at dark on the 18th within striking distance of Barjols. The entire advance completely dislocated the center of the line that Wiese had hoped to establish.

Well to the east the 142nd Infantry, 36th Division, cleaned out the north side of the Argens valley with little trouble and, passing through units of the 1st Airborne Task Force at Le Muy, mopped up the Draguignan area during the 18th. The 143rd Infantry reassembled in the vicinity of Le Muy on the 17th and 18th, while the 141st Infantry and the 636th Tank Destroyer Battalion spread out to secure the region extending east from Le Muy to the coast as well as the slopes of the Esterel. During the 18th the 636th Tank Destroyer Battalion sent reconnaissance troops north about fifteen miles from Frejus in an effort to rescue a group of misdropped paratroopers that the Germans had cut off. The first attempt failed, but after hard fighting on the 19th, elements of the 141st Infantry and the tank destroyer battalion extricated many injured paratroopers.

Meanwhile, the 36th Division’s Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop had been indulging itself in a series of long-distance scouting patrols to the north. Rapidly moving twenty-five to thirty miles north and northeast of Le Muy as far as Route N-85, which is the main highway from the Riviera to Grenoble, the light cavalry units encountered no significant resistance on 17 and 18 August. The patrolling, together with information received from ULTRA sources,6 reflected the general weakness of the German forces along the Seventh Army’s eastern flank. Once TF Butler and the 36th Division started north and northwest, they apparently would face no significant threat on their right, or northeastern, flank.

The German Defense

In the early afternoon of 17 August, Nineteenth Army officers

Troops and Tank Destroyers move through Salernes.

learned that VI Corps’ center and right wing had passed through the defensive line they had planned to establish from the coast to Vidauban. Seeking some way to hold back Allied forces until more German units, especially the 11th Panzer Division, could move to the east side of the Rhone, General Wiese decided to establish two new defensive lines. The first would extend northward from the eastern defenses of Toulon through Brignoles to Barjols. The second line, about fifteen miles farther west, would anchor on the south at Marseille, stretch eastward about twenty miles along Route N-8 (the Toulon–Marseille highway), and then swing north to the Durance River about fourteen miles northwest of Barjols. These two lines represented Wiese’s last effort to tie the defense of Toulon and Marseille to that of the Rhone River valley, which was still fifty miles farther west.

Wiese assigned responsibility for holding the two new lines to Lt. Gen. Baptist Kniess, commanding the LXXXV Corps. Kniess would have what was left of the 244th Division (guarding Marseille), the 338th Division (less one regimental combat team), the remnants of the 242nd Division, and part of the 198th Division, which was still trying to cross the Rhone. Wiese also gave Kniess General von Schwerin and his 189th Division headquarters, along with the miscellaneous units that von Schwerin had already assembled. Kniess, in turn, directed

Baessler of the 242nd Division to hold Toulon and the southern part of the first line with whatever units the division commander could round up; he ordered von Schwerin to hold the center at Brignoles and Barjols with the 15th Grenadiers of his former division and the battered 932nd and 933rd Grenadier Regiments of the 244th Division. The 198th Division, reinforced by elements of the 338th Division, would man the second line as quickly as possible, for Kniess had little confidence that he could hold the first line past nightfall on 18 August. If all went well, the delay along the first line would provide enough time for the 11th Panzer Division and the remaining elements of the 198th and 338th Divisions to cross the Rhone.

The German plans were again overtaken by events. Except on the immediate Toulon front, General Kniess was unable to establish the first line, and the Brignoles–Barjols area fell before any LXXXV Corps units could establish a coherent defense. Accordingly, during the afternoon of 18 August, Wiese directed a general retirement to the second line. Here Kniess planned to have the 198th Division, which so far had been able to deploy only two infantry battalions, hold the northern section of the second line near the Durance River; the 242nd Division—now so reduced in strength as to be redesignated Battle Group Baessler—defend the center with the equivalent of a regimental task force; and two battalions of the 244th Division anchor the line in the south at Marseille. The garrison at Toulon would have to fend for itself.

The Allied push westward was, however, again relentless. By the morning of 19 August, the 30th Infantry, 3rd Division, had cleared Brignoles, and Sudre’s CC1 had pushed to St. Maximin, eleven miles farther west. The 15th Infantry joined the French armor at St. Maximin later in the day and by the evening had traveled another nine miles west to the town of Trets. The general advance met only minor German resistance, but had breached the center of Kniess’ second line of defense before it could be established.

Meanwhile, north of Brignoles, the 179th Infantry of the 45th Division had cleaned out Barjols on the 19th, while still farther north the 157th Infantry had pushed west and by dusk was nearing the Durance River. It began to appear to jubilant operations officers at all echelons of command that the east-west highways and byways between the coastal ports and the Durance River might be undefended all the way to the Rhone. If so, the Nineteenth Army might be in for a major disaster if the American drive west continued at its current pace.

For General Patch, the Seventh Army commander, the capture of Toulon and Marseille was more pressing. Until the ports were in Allied hands, the success of the invasion could not be confirmed. Thus, as Sudre’s armored force was preparing to continue its drive west, Patch ordered Truscott to return the unit to French control for the assault on Toulon. Reluctant to lose the force and arguing that its return east would create traffic jams, which would seriously inhibit the westward progress of the 3rd Division, Truscott rushed to the Seventh Army’s command post at St. Tropez to dispute the decision.

Patch was unmoved and refused to reverse the long-standing arrangement. Although sympathetic, he reminded Truscott that the Seventh Army had promised General de Lattre to return CC1 by dark on the 19th to a position from which it could move forward on the 20th with the rest of the French forces heading toward Toulon. General Sudre of CC1, who disliked the redeployment order as much as Truscott, had no choice but to move his command back east along Route N-7, thus creating the traffic jams Truscott had feared and, more important, depriving the VI Corps of its most powerful mobile striking force. In its place, Task Force Butler would have to suffice.7

Task Force Butler

By evening on 17 August, almost all of TF Butler had assembled just north of Le Muy.8 A brigade-sized unit, the force included the 117th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron; the 753rd Tank Battalion (with two medium tank companies); the motorized 2nd Battalion of the 143rd Infantry, 36th Division; Company C, 636th Tank Destroyer Battalion; and the 59th Armored Field Artillery Battalion.9 Support forces included Company F of the 344th Engineer General Service Regiment; a reinforced company from the 111th Medical Battalion, 36th Division; the 3426th Quartermaster Truck Company; and a detachment of the 87th Ordnance Company (Heavy Maintenance).

Butler’s mechanized task force started out early on 18 August, first following the 45th Division’s trail west to the Barjols area, and then striking north on its own. By noon the force had reached the Verdon River, ten miles above Barjols, but found the highway bridge destroyed and was unable to cross until about 1600, despite assistance from the FFI and local French civilians. Then, with only about four hours of daylight left and five hours of fuel, Butler decided to wait for his resupply column, due to arrive that night. Meanwhile, one element of the force, Troop C, which had taken a slightly different route north, bumped into a portion of the LXII Corps staff that had eluded the airborne units, and captured the unfortunate General Neuling.

The next day, 19 August, the main body of the task force struck out northwest, crossing to the west bank of the Durance River to take advantage of better roads there, and continued north to Sisteron. Troops A and B of the 117th Cavalry remained on the eastern side of the river and, after a few minor skirmishes with isolated German units, entered Sisteron unopposed

about 1800 hours. The main column, its march north disturbed only by a mistaken strafing attack from friendly aircraft, reached the town shortly thereafter. The only sizable action took place at Digne, fifteen miles southeast of Sisteron, where armored elements of Butler’s force helped an FFI battalion convince about 500 to 600 German defenders—mostly administrative and logistical troops—to surrender after several hours of fighting.10

That evening Butler refueled his vehicles, established outposts north of Sisteron, and sent out several mobile patrols to the west, which scouted to within thirty miles of Avignon and the Rhone. With good radio communications established with VI Corps headquarters and several intact bridges over the Durance River in his hands, he was ready to move his task force either north toward Grenoble or west-northwest toward the Rhone River in the vicinity of Montelimar. Impatiently he awaited Truscott’s orders.

Accelerating the Campaign

The campaign in southern France was quickly reaching a crisis point. Well before 19 August the unexpected weakness of German resistance in the assault area had brought about two significant changes in Seventh Army plans.11 The first was Truscott’s exploitation order of late 16 August, which had started the 3rd and 45th Divisions westward and TF Butler northward. The second, made by Patch, was to accelerate the unloading of the French II Corps.

Original plans had called for the first echelon of the French II Corps to land between 16 and 18 August, and the second between the 21st and the 25th. Seeking to exploit German weakness and speed up the move to Toulon and Marseille, Patch, in conjunction with Admiral Hewitt and General de Lattre, pushed up the schedule. The bulk of the first French echelon came ashore on 16 August, and elements of various French armored units arrived the next day. This allowed the troop transports to make a rapid trip back to Corsica, and return with troops of the second echelon on the 18th. By nightfall that day almost all troops of the II Corps (excepting those of one armored combat command and one regiment) were ashore, but scarcely half the trucks, tanks, tank destroyers, artillery, and other heavy equipment were on hand.

Meanwhile, on 17 August, Patch and de Lattre decided to move the French troops up to the line of the Real Martin and Gapeau rivers on the 19th instead of assembling all of French II Corps, including its missing equipment, near the beaches. This decision alone had the French forces

moving westward at least six days earlier than originally planned. Finally, rather than waiting until 25 August, when all the French vehicles and equipment would be ashore, de Lattre wanted to attack Toulon as soon as possible, asking only for the return of Sudre’s armor on the 19th and the loan of artillery ammunition from Seventh Army stocks. With this help, he felt he could launch an effective assault on 20 August before the Germans had time to organize their defenses. Patch agreed to the acceleration, supplied the ammunition de Lattre needed, released CC1 to French control, and at noon on the 19th directed de Lattre to move immediately toward Toulon and Marseille.

Simultaneously, Patch ordered VI Corps to push westward to Aix-en-Provence, fifteen miles north of Marseille, in order to protect the northern flank of the attacking French. The American corps was also to secure crossings over the Durance River; seize Sisteron (which TF Butler reached about four hours later); continue strong reconnaissance northward; and prepare to start the 36th Division north toward Grenoble.

Seventh Army’s new orders also reflected changes in Allied estimates of German capabilities and intentions in southern France. Patch’s intelligence staff had originally expected that Army Group G, after making every effort to contain the Allied beachhead, would conduct an all-out defense of Toulon and Marseille, and, after it had exhausted its defensive potential east of the lower Rhone, would ultimately undertake a fighting withdrawal up the Rhone valley. But late on 17 August Seventh Army planners received information through ULTRA channels that forced them to revise this estimate. According to an ULTRA intercept, Army Group G was about to initiate a general withdrawal of its forces from southwestern France and the Atlantic coast south of Brest; if accurate, the withdrawal of the Nineteenth Army could not be far behind, and the success of the landing was assured.

The German Withdrawal

In Germany, OKW was more concerned about Army Group B in northern France than about Army Group G in the south. The Allied breakout from the Normandy beachheads at St. Lo, the failure of the German counterattack at Mortain, and the threatened Allied envelopment of the German forces in the Falaise Pocket, all pointed to a major German disaster in the north. At the same time, the ANVIL landings made it impossible for Army Group G to withdraw from southern France to northern Italy if German defenses in the Normandy area finally collapsed. Accordingly, on 16 August OKW put the issue before Hitler: either authorize the immediate withdrawal of Army Groups B and G or preside over the destruction of both. Having no real choice, Hitler reluctantly assented, and OKW quickly issued the necessary orders.

From the start, German execution of the orders was hampered by poor communications. The withdrawal orders for Army Group G were in two parts. About 1115 on 17 August Blaskowitz’s headquarters received the first part, pertaining mainly to

forces on the Atlantic coast and in southwestern France. This order came directly to Army Group G from OKW, and it was not until 1430 on the same day that Blaskowitz received an identical directive relayed through OB West channels. Presumably OKW dispatched the second part of the order, pertaining largely to the Nineteenth Army, at 1730 on 17 August, but neither OB West nor Army Group G received the second order that day. Such was the state of German communications that it was 1100 on the 18th before Blaskowitz, via OKW radio channels, received the second part of the order, which directed the Nineteenth Army to withdraw northward from southern France. Meanwhile, by early afternoon of the 18th, ULTRA sources had supplied the Seventh Army with the second part; thus Patch and Wiese were probably evaluating the new information at about the same time.12 Both armies now had to consider how best to react to the sudden change in plans.

Upon receiving the Atlantic coast-southwestern France directive on the 17th, Blaskowitz had ordered Lt. Gen. Karl Sachs, who commanded the LXIV Corps on the Atlantic front, to begin moving eastward immediately. The LXIV Corps was to assemble most of its assigned forces—the 16th and 159th Infantry Divisions, miscellaneous army combat and service units, and a conglomeration of small air force and naval organizations—in the northern part of Army Group G’s Atlantic sector. These units, representing three-quarters of LXIV Corps’ strength and virtually its entire combat complement, were to move generally eastward south of the Loire River to a rendezvous with the main body of Army Group G north of Lyon. Left behind on the Atlantic coast were the garrisons of three coastal strongpoints that Hitler directed be held to the end: Defense Area La Rochelle, Fortress Gironde North, and Fortress Gironde South. LXIV Corps was also to leave a small force at Bordeaux until the German Navy could put to sea a few submarines undergoing repairs there.

In the extreme southwest, Blaskowitz wanted Maj. Gen. Otto Schmidt-Hartung of the 564th Liaison Staff; a military government organization, to lead a motley collection of army service units and air force troops out of the Pyrenees–Carcassonne Gap–Toulouse area to join other Army Group G units along the west bank of the Rhone near Avignon.

The second OKW message—a “Hitler Sends” directive—ordering the northward deployment of the Nineteenth Army, called for a more carefully thought out withdrawal concept. On the western Mediterranean coast, the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps, with the 716th Infantry Division as its principal combat component, was to retire

up the west bank of the Rhone, picking up Schmidt-Hartung’s group, some local naval units, three infantry battalions of the 189th Division, one or two Luftwaffe infantry training regiments, and other miscellaneous units. On Army Group G’s far eastern flank, the 148th Division and the 157th Reserve Mountain Division no longer concerned Blaskowitz because the OKW withdrawal orders had transferred the two divisions to OB Southwest in Italy, and their retirement to the Alps seemed a relatively simple affair.13

Extracting that portion of the Nineteenth Army engaged in combat was by far the most difficult undertaking. Blaskowitz’s concept called for these forces to retire through successive defense lines, holding the U.S. Seventh Army east of the Rhone and south of the Durance until the 11th Panzer Division, the bulk of the 198th Division, and the two remaining regimental combat teams of the 338th Division could cross the Rhone to participate in a general withdrawal up the east bank. The garrisons at Toulon and Marseille, ordered by Hitler to fight to the death, were to tie down as many Allied troops as possible and ensure that the harbor facilities did not fall into Allied hands intact.

On 18 and 19 August the staffs of the Nineteenth Army and LXXXV Corps drew up detailed plans for the withdrawal, specifying three successive north-south delaying positions, labeled A, B, and C. The first, line A, began above Marseille and centered on Aix-en-Provence; the second, line B, was located between Lake Berre and the Durance River; and a third, line C, was just west of the Rhone. Kniess wanted his LXXXV Corps units to reach line A during the night of 19–20 August; line B during the night of 20–21 August; and line C before daylight on the 22nd. The Nineteenth Army expected him to hold along line C until evening on the 23rd, by which time, Wiese hoped, all preparations would be complete for a rapid, well-organized withdrawal up the Rhone valley, with the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps on the west bank and the LXXXV Corps on the east.

For the Germans, the appearance of American mechanized forces north of the Durance River on the 19th was an unwelcome surprise. As yet, Army Group G had little solid information concerning Task Force Butler, but Blaskowitz had learned enough by nightfall on the 19th to realize that he might have a problem securing the eastern flank of his forces withdrawing up the Rhone valley. With the Nineteenth Army already having trouble holding back VI Corps in the area south of the Durance River, a strong threat north of the Durance might turn a carefully phased withdrawal into a rout. On the other hand, Blaskowitz felt he had sufficient strength to deal with any immediate threat north of the Durance, and also estimated that for the time being a major thrust northward toward Grenoble and Lyon was of secondary importance in Allied planning.

On the evening of 19 August,

German attention thus remained focused on the critical Avignon area, the focal point for German forces withdrawing both east across the Rhone and north across the Durance. By that time substantial components of the 11th Panzer Division and the 198th and 338th Infantry Divisions still had to cross to the east bank of the Rhone on a single ferry near Avignon and on two more farther south. In addition, the Germans had to hold crossings over the Durance east of Avignon until the LXXXV Corps as well as units coming over the Rhone south of Avignon could move north across the Durance. A strong Allied drive toward Avignon could cut off much of the LXXXV Corps. An additional concern was an Allied drive to and across the Rhone south of Avignon before the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps, withdrawing up the Rhone’s west bank, could escape. If that happened, the bulk of the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps would probably be lost. Under these circumstances, Generals Blaskowitz and Wiese could hardly avoid the conclusion that a strong Seventh Army drive to the Rhone in the Avignon area would be the Allies’ most logical, timely, and likely course of action.

In the Allied camp, however, the proper course of action was not so evident. Based on the ULTRA information that Patch had received on 17 and 18 August, the Seventh Army’s best move appeared to be an immediate push toward the Rhone in an attempt to cut off the Nineteenth Army. But a number of factors stayed Patch’s hand. Logistics had now become a major problem. A general shortage of trucks and gasoline meant that the Allied logistical system could not immediately support a major effort to cut off the Nineteenth Army at Avignon or farther north up the Rhone valley. For deeper operations inland, Toulon and Marseille would have to be taken and rehabilitated, a task that a strong German defense might make exceedingly difficult. In northern France, Eisenhower’s forces were already suffering from a lack of operational ports, and Patch, with comparatively little over-the-beach supply capability, could not afford similar difficulties. Thus, on the 19th, he made Aix-en-Provence the western limit of Truscott’s VI Corps advance, primarily to protect the Seventh Army’s main effort, which was seizing Toulon and Marseille.

Toulon and Marseille

Before the invasion, de Lattre had planned to capture Toulon and Marseille in succession, but the accelerated French landings allowed him to envision almost concurrent actions against both ports.14 He divided his forces into two groups: one under Lt. Gen. Edgar de Larminat consisting of two infantry divisions, some tanks, and the African Commando Group; the other under Maj. Gen. Aime de Goislard de Monsabert consisting of an infantry division, some tanks, and a ranger-type unit. De Larminat was to attack Toulon westward along the coast; de Monsabert was to maintain flank contact with the VI Corps on the right, strike into Toulon from the

north, drive to the coast to encircle the city, and, if possible, probe west toward Marseille. From the afternoon of 19 August through the night, French troops poured westward from the landing beaches to take positions for the assault against Toulon on the following day.

If the Germans had had more time and matériel, they might have turned Toulon into a formidable fortress. The local garrison consisted of about 18,000 troops, including 5,500 naval personnel and 2,800 air force men, plus naval and army artillery and antiaircraft guns. Equally important, the port was virtually surrounded by rugged hills and mountains—those to the north rising to nearly 2,500 feet. If Toulon was strongly defended, the Allied timetable could be severely disrupted. However, from the start German command difficulties hampered the organization of a coherent defense. The senior admiral of the port had died of a heart attack several days before ANVIL, and General Baessler, the senior army officer, had been cut off from the city several days afterward. Rear Adm. Heinrich Ruhfus, who subsequently took command of the German defense, did the best he could and evacuated the increasingly restive civilian population, probably about 100,000 men, women, and children, prior to the battle. But Ruhfus needed time to reorganize his forces. The existing defenses were strongest in the wrong places. On the landward approaches, they were spotty and incomplete—in some cases no more than roadblocks—and little attention had been paid to the northern and western sectors of the city. If the Allies moved quickly, the Germans would have difficulty putting up any effective resistance.

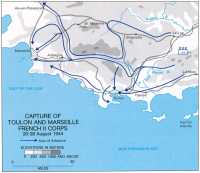

The French attacked on the morning of 20 August, and the first results were less than promising.15 Heavy artillery, antitank, and machine-gun fire was initially severe along the coastal road, and de Larminat’s forces had to reduce, one by one, a series of major and minor strongpoints. Infantrymen clawed their way to the outskirts of Hyeres, nine miles east of Toulon, late in the day; but determined German resistance stopped the French drive from the northeast (Map 8). In the west, however, de Monsabert’s units achieved spectacular success. Swinging across high rough mountains, they outflanked the German defenders and pushed through the western approaches to the city, some leading elements penetrating to within less than two miles of the Toulon waterfront. Another group, operating approximately six miles west of Toulon, cut the main highway between Toulon and Marseille,

Map 8: Capture of Toulon and Marseille, French II Corps 20–28 August 1944.

with elements of de Monsabert’s armor approaching the strongly defended village of Aubagne, which was eight miles from Marseille and the key to the eastern approaches to that city. In addition, troops of the U.S. 3rd Division, preparing to attack Aix-en-Provence, spilled into the French zone and came within six miles of Aubagne.

On the morning of the 21st the French attacked Toulon with renewed vigor. While some units hammered away toward the city along the coast, others continued to encircle the port on the north and west. Progress in the north was disappointing as German resistance stiffened. One French tank company managed to penetrate to about three and a half miles from the principal square in Toulon, but was cut off, taking heavy casualties while holding out for almost thirty-six hours.

Toward the end of the day, de Larminat, believing that the operations

against the two ports demanded a unified command, requested permission to take charge of the entire operation. De Lattre turned the corps commander down and, after a lengthy argument between the two quick-tempered generals, dismissed de Larminat and took direct control of the operation.16 The command change had little, if any, effect on French operations.

On the 23rd, the French continued to exert pressure on Toulon, forcing the Germans back into their inner fortifications, overrunning German strongpoints west of the city, and opening rail and highway connections toward Marseille. As the fighting continued, the German defense lost cohesion, and negotiations opened for the surrender of isolated German groups. The last organized German resistance ended on 26 August, and a small command garrison under Admiral Ruhfus surrendered on the 28th after two days of intense Allied air and naval bombardment. The battle cost the French about 2,700 men killed and wounded, while the Germans lost their entire garrison of 18,000. However, the French claimed to have taken almost 17,000 prisoners, indicating that only about 1,000 Germans lost their lives defending the city—hardly a serious attempt to follow Hitler’s order to fight to the last man. Toulon had been secured a full week ahead of Allied expectations.

Even as the French invested Toulon, part of their forces were moving on their second objective, Marseille. From the beginning of the attacks, de Lattre had decided that the conquest of Toulon would not absorb his entire force and directed de Monsabert to probe aggressively to the west. Although reminding his subordinate of Toulon’s priority, de Lattre probably expected him to interpret his instructions as broadly as possible and to exploit favorable opportunities to speed the seizure of Marseille. But de Monsabert’s first objective was Aubagne.

The German force at Aubagne was part of the 13,000-man garrison of Marseille, which included several key units of the 244th Infantry Division and 2,500 naval and 3,900 Luftwaffe personnel, all under the control of Maj. Gen. Hans Schaeffer, the 244th Division commander. The landward approaches to Marseille gave the Germans significant defensive advantages, but again time and lack of matériel worked against them. Their fortifications were less extensive than at Toulon, and the half a million civilian inhabitants of the second largest city in France were becoming increasingly hostile. Schaeffer had chosen not to evacuate the city, and as the attacking French military forces drew near, the FFI became bolder, encouraged by a major civil uprising on the morning of 22 August.

Without waiting to reduce Aubagne, de Monsabert positioned his units, consisting of less than a division in strength, around the eastern and northern outskirts of the city to harass the confused defenders. Gains on the 22nd put French troops within five to eight miles of the heart of the city, and they prepared to strike well into the port on the following day.

French troops in Marseille, August 1944.

While approving de Monsabert’s initiative, de Lattre was concerned by the dispersal of the attacking forces. Patch had informed him of the appearance of the 11th Panzer Division in the Aix-en-Provence area, and de Monsabert’s trucks and combat vehicles were running low on fuel.17 Believing that the French lacked sufficient strength for a full-fledged battle in Marseille, should it come to that, de Lattre instructed de Monsabert to back off a bit and ring the city with his troops, but to limit his offensive operations to clearing the suburbs until more units arrived.

On the ground, de Monsabert believed that more could be lost than gained by holding back. He relayed de Lattre’s orders to his own subordinates, but his instructions to Col. Abel Felix Andre Chappuis, who commanded the 7th Algerian Tirailleurs, were flexible. Spurred by calls for assistance from resistance groups inside Marseille, Chappuis’ infantry prowled the eastern suburbs; in the early hours of 23 August, one battalion, encouraged by large crowds of exuberant French civilians, plunged into the city itself. By 0800, the tirailleurs had begun pushing through the city streets, and two hours later, after cutting through the center of Marseille, they reached the waterfront. Later that day the rest of the regiment entered the city from the north and

northeast. This unplanned drive decided the issue, and the fighting, like the final days in Toulon, became a matter of battling from street to street, from house to house, and from strongpoint to strongpoint, with ardent FFI support.

On the evening of 27 August, Schaeffer parlayed with de Monsabert to arrange terms, and a formal surrender became effective at 1300, 28 August, the same day as the capitulation at Toulon. The French had lost 1,825 men killed and wounded in the battle for Marseille, had taken roughly 11,000 prisoners, and had again accomplished their mission well ahead of the Allied planning schedule.18

West to the Rhone

Meanwhile, the general picture of German weakness along the approaches to the Rhone changed on the afternoon of 21 August when elements of the 11th Panzer Division were reported west of the river. Patch and Truscott wondered whether the German armored movements, about which they could learn little, might indicate a counterattack. Truscott’s only reserve, the 36th Division, was already on its way north on the route followed by Task Force Butler, as was a regiment of the 45th Division. Truscott had been considering sending the entire 45th Division to the north, but now tabled this idea and ordered the 3rd and 45th Divisions to halt along a north-south line above Marseille.19

Unknown to the Allied commanders, the Germans had no intention of mounting a counterattack. Wiese’s decision to send a tank-infantry task force with about ten tanks toward Aix-en-Provence was a reaction to what had been, until the 21st, a steady Allied push to the Rhone. The task force was merely to give the Americans pause, something to think about. Wiese hoped to slow American progress and buy time for Kniess’ LXXXV Corps withdrawal. Truscott, in any case, had been ordered to hold up until Toulon and Marseille were secure. As a result, Kniess was able to withdraw the remainder of his forces without interference. His corps assembled along the second defensive line on the morning of 21 August and pulled back easily to the final line during the following night. By the morning of the 22nd, almost all units scheduled to cross over the Rhone from the west were on the eastern bank, and the bulk of Petersen’s IV Luftwaffe Field Corps, still west of the Rhone, was moving north and coming abreast of Kniess on the other side.

Deployed along the final defensive line early on the 22nd, Kniess planned to hold until dark on the 23rd. His defenses extended from the Rhone River at Arles, northeast to the Durance River at Orgon, and then north thirty miles to Avignon and the main Rhone valley. The focal point was Orgon, where the Durance River passed through a defile two miles wide. The Germans had to hold the gap until all of Kniess’ units could cross the river to the north bank. Concerned about his eastern flank, Wiese sent reconnaissance units of the 11th Panzer Division to probe north

of the Durance and ascertain the intentions of the American armored forces that Wiese knew were active there; but the unit found little except assorted FFI resistance units.

Not until late in the morning of the 22nd was Truscott sufficiently satisfied about German intentions in the lower Rhone. With the attacks against the ports proceeding as planned, he released another regiment of the 45th Division for redeployment northward, but decided to keep the 3rd Division south of the Durance until French forces could relieve it. Both the 3rd Division and the remainder of the 45th advanced westward during the day, and both units reached Kniess’ abandoned second line that afternoon.

Wiese now began to worry less about his southern front. Increasingly disturbed by threats developing on the eastern flank of his withdrawal route, he ordered all elements of the 11th Panzer Division to move immediately north; he alerted Kniess to start the 198th Division moving up the Rhone as well, leaving him only the weak 338th Division and miscellaneous attached units to hold the Durance crossings at Orgon, to protect his southern flank, and to defend Avignon against an American sweep. Wiese now wanted all his units to be north of the Durance well before dark on 23 August, the time previously set for abandoning the final line below the Durance.

On the 23rd, with the ports not yet secure, Patch and Truscott cautiously limited the 3rd Division’s movement west and thereby may have sacrificed an opportunity to cut off major portions of Kniess’ corps south of the Durance or to block the withdrawal of Petersen’s corps. Virtually undisturbed during the daylight hours, the remainder of Kniess’ forces crossed the Durance during the night of 23–24 August. On 24 August, as French units began to relieve elements of the 3rd Division, and Allied troops occupied Avignon unopposed, Kniess’ LXXXV Corps escaped. His forces, together with those of Petersen, now marched rapidly up the Rhone valley toward Montelimar, thirty miles away, and the focus of operations quickly began to shift to the north.