Chapter 9: The Battle of Montelimar

As de Lattre’s French forces prepared to move against the port cities with the bulk of Truscott’s VI Corps on their northern flank, Patch began to consider his future course of action if all went well along the coast. His first task, to secure the landing area, had been accomplished; seizing Toulon and Marseille was his next major objective. The ports would give him the logistical base he needed for a sustained drive north to join Eisenhower’s armies in northern France, his third major task. But until the ports were secure, supplying his American divisions with fuel, vehicles, and ammunition for anything so ambitious would be extremely difficult. Nevertheless, both he and Truscott were eager to exploit the rapid German withdrawal and unwilling to allow the remainder of the Nineteenth Army to escape intact, especially if the Germans intended to make a stand farther up the narrow Rhone valley. Truscott had created Task Force Butler for this purpose. With its motorized infantry battalion, its approximately thirty medium tanks, twelve tank destroyers, and twelve self-propelled artillery pieces, and the armored cars, light tanks, and trucks of the cavalry squadron, TF Butler represented a balanced, mobile offensive force.

Task Force Butler (19–21 August)

On 19 August, Butler’s vehicles were already well on their way north. At noon, shortly before Butler reached Sisteron, Patch directed Truscott to alert one infantry division for a drive northward on Grenoble. Truscott, in turn, instructed General Dahlquist, the 36th Division commander, to be prepared to have his unit execute the order early the following day.1 The VI Corps commander expected at least one regiment of the 36th Division to be at Sisteron on the afternoon of the 20th. Convinced of German intentions to withdraw up the Rhone valley, Truscott also radioed Butler to hold at Sisteron and await the arrival of Dahlquist’s units, adding that he should continue his patrols westward to “determine the practicability of seizing the high

ground north of Montelimar.”2 Montelimar, a small city on the east bank of the Rhone River about fifty miles north of Avignon and sixty miles west of Sisteron, lay astride the most probable German route of withdrawal. (See Map 7.)

Butler, whose radio communications with VI Corps headquarters had become intermittent, never received the message.3 The only instructions arriving during the night of 19–20 August stated that the mission of his task force was unchanged. Shortly before midnight, Butler thus reported his intention to continue his reconnaissance activities the following morning, but warned that shortages of fuel and supplies would limit his advance to forty miles in any direction. He emphasized his need for further instructions that would enable him to direct his main effort either north to Grenoble or west to Montelimar and the Rhone. The general also felt uneasy remaining stationary at Sisteron, deep in enemy territory, with limited logistical support. The FFI and his own artillery liaison planes had reported a strong, mobile German force at Grenoble and a large garrison at Gap, about thirty miles above Sisteron. Both could block Butler’s advance northward. Expecting Grenoble to be his immediate objective, Butler decided to establish a strong outpost at the Croix Haute Pass, about forty miles north on the main highway to Grenoble, and to dispatch a force to Gap. Meanwhile, he sent his operations officer in a liaison plane to corps headquarters for more specific guidance.

On the following morning, 20 August, Butler grouped the main body of his task force at Sisteron and Aspres, thirty miles to the northeast, and sent reinforced cavalry troops to the pass at Croix Haute and to Gap. Both forces reached their objectives during the afternoon, the Gap patrol capturing over 900 German prisoners after a short skirmish aided by local FFI elements. By dusk Task Force Butler was thus spread over a wide area, but oriented more for an advance on Grenoble than one on Montelimar. Supply convoys brought Butler news on the approach of 36th Division elements, but his operations officer returned with no information other than that new orders would be forthcoming sometime that night.

On the evening of the 20th, Butler met with Brig. Gen. Robert I. Stack, the assistant division commander of the 36th. Stack, arriving with an advance echelon of the division headquarters and a regimental task force built around two battalions of the 143rd Infantry (its third battalion was with Butler), passed on to Butler what information he could: that the 36th Division was now displacing north; that Truscott had released the division’s 142nd Infantry from corps reserve at noon that day, and this regiment was now arriving at Castellane, thirty-five miles away; and that the 141st Infantry had finally been relieved by airborne troops on the Seventh Army’s right flank and would follow north the next morning. However,

American armor moves inland.

he warned Butler that all divisional movements had been slowed by a serious shortage of fuel and trucks, and that most units were moving north in time-consuming company-sized shuttles. Precisely when they would reach Sisteron was unknown. The assistant division commander further explained that he intended to have the 143rd Infantry strike out for Grenoble on the following morning, 21 August, and that it was his opinion also that Grenoble was Butler’s most logical objective.

Radioing Dahlquist, Stack asked whether the 143rd Infantry was to use the same roads to Grenoble as Butler. Dahlquist, having talked with Truscott on the 19th but knowing little of Butler’s movements, responded that Butler was to remain in the Sisteron area until most of the 36th Division had arrived and promised to seek clarification on the matter from Truscott. Communicating with Stack several hours later, Dahlquist instructed him to hold all arriving division elements in the Sisteron region and to cancel the move to Grenoble, explaining that the division’s objective might be changed to the Rhone valley. Further orders, Dahlquist continued, would come early the following morning. Stack relayed this information to Butler about 2300, 20 August.

Unknown to Stack and Dahlquist, Truscott had met again with Patch around noon of the 20th, had informed him of the decision to send the 143rd Infantry northward, and had

requested his approval to follow the regiment with the rest of the 36th Division and to send Task Force Butler west to the Rhone. Patch quickly agreed with these plans, which were bold undertakings considering the uncertain situation in the south and the lack of vehicles and fuel. Perhaps mindful of these constraints, Truscott did not immediately relay these orders to Butler, thereby failing to forestall the temporary dispersion of his task force. By the end of the day, however, the corps commander had become more certain of German intentions south of the Durance River and of his ability to reinforce Butler if necessary. Thus at 2045, 20 August, Truscott finally radioed specific instructions to Butler, directing him to move to Montelimar at dawn with all possible speed. There Butler was to seize the town and block the German routes of withdrawal. The 36th Division would follow the task force as quickly as possible.

Butler received the message that night and acknowledged receipt early the next morning. Nevertheless, Truscott also sent Lt. Col. Theodore J. Conway of his G-3 section to Butler’s headquarters with more specific written instructions. Reaching Butler’s command post at Aspres in the early hours of 21 August, Conway delivered the letter from Truscott instructing Butler to seize the high ground immediately north of Montelimar, but not the city itself, before dark that day. Two battalions of corps artillery were on their way to reinforce the task force, but initially only a single regimental combat team from the 36th would support the effort; the rest of the division would follow later. Dahlquist would take control of Butler’s task force when he arrived in the forward area.

The new orders presented several problems. First, neither Stack nor Dahlquist had been informed of the switch in the main effort from Grenoble to Montelimar. Second, Butler’s movements on the previous day had oriented his advance north toward Grenoble, and he needed considerable time to reassemble his scattered forces. At the same time, he felt compelled to leave a small blocking force at Gap to secure his rear and, as directed by supplemental orders from Truscott, to retain the block at the Croix Haute Pass until 36th Division units could take over.

By daybreak of 21 August, Butler had regrouped the bulk of his task force at Aspres. Leaving a small detachment at the pass and a larger one at Gap, he started the rest of his command rolling westward. Moving without interference a good twenty-five miles, the task force reached Crest on the Drome River in the late afternoon, about thirteen miles east of the Rhone. Before it lay the Rhone valley and the setting for the eight-day battle of Montelimar.

The Battle Square

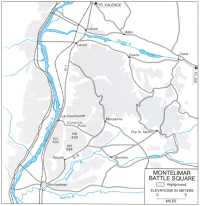

Almost twenty miles northeast of Montelimar, the town of Crest was at one corner of what became known as the Montelimar Battle Square, bounded by the Drome River on the north, the Rhone River on the west, and the Roubion River on the south (Map 9). With sides varying from nine to seventeen miles, the square, or rectangle, encompassed an area of about

Map 9: Montelimar Battle Square

250 square miles on ground that alternated between flat, open farmland and rugged, wooded hills, which rose, often steeply, to more than 1,900 feet.

Montelimar itself is on a small, flat plain extending along the north bank of the Roubion River, a little over two miles east of the Rhone. Route N-7, the main north-south artery along the Rhone, passes through the city and then runs almost due north to the Drome. A secondary road, D-6, runs northeast from Montelimar about two miles to the small village of Sauzet and then turns east, skirting the

northern bank of the Roubion. On Route N-7, about six miles above Montelimar, is the small town of La Coucourde. Between Montelimar and La Coucourde the eastern side of the Rhone valley narrows considerably, squeezing both N-7 and a parallel railway line between the Rhone and a high ridgeline, which the American troops labeled Hill 300. The ridgeline easily dominated Route N-7, as well as a parallel road on the west bank of the Rhone and the railways on both sides. Two other hills to the east, Hill 294 and Hill 430, provided additional observation of both banks of the Rhone and, to the south, overlooked the approaches to Sauzet and D-6. In all, this high ground dominated the Rhone valley for a distance of roughly fifteen miles. All retreating German forces would have to pass through the bottleneck that Task Force Butler was about to squeeze.

Initial Skirmishes (21–22 August)

Late in the afternoon of 21 August, Butler’s men moved south from Crest to Puy St. Martin, and then west to Marsanne in the center of the square, probing farther west through the Condillac Pass toward La Coucourde and south down Route D-6 toward Sauzet and Montelimar. Lt. Col. Joseph G. Felber, commanding the advance party, immediately recognized Hill 300 as the key terrain feature and established his command post nearby at the Chateau Condillac. Unable to secure the entire ridgeline of Hill 300, Felber set up outposts, roadblocks, and guard points and posted accompanying FFI soldiers in Sauzet.

German forces were already traveling north along the main highway, and, as soon as an artillery battery could unlimber its pieces, Felber had it open fire on the German traffic. A second battery and several tanks and tank destroyers soon added their fire, while a cavalry troop and some infantry placed a roadblock across the main highway, until a German attack at dusk drove the small force back into the hills. On the north bank of the Drome River, another cavalry troop, after moving west from Crest, fired on a German truck column fording a stream, and then advanced and destroyed about fifty German vehicles.

Upon reaching the forward area, Butler ordered the troop operating on the Drome back to Crest to protect the roads to Puy St. Martin, but left a platoon on the north bank of the Drome as flank protection. After establishing his command post at Marsanne, he sent a message to Truscott’s corps headquarters at 2330 confirming his unit’s arrival at the objective area. His forces, Butler reported, were thinly spread, but with the expected reinforcements—a regiment of the 36th Division and more artillery—he was confident he could deal with a determined German reaction and launch a successful attack against Montelimar the following afternoon. However, until he was resupplied with ammunition, his artillery and tank destroyers would be unable to halt all the German traffic along the highway.

The morning of 22 August found Butler still waiting for supplies and reinforcement. Meanwhile the Germans moved first, mounting what was to be the first of many efforts to dislodge the Americans. Grouped

around the reconnaissance battalion of the 11th Panzer Division and elements of the 71st Luftwaffe Infantry Training Regiment,4 an ad hoc force attacked north from Montelimar about noon, took Sauzet, and forced an American outpost and the FFI back into the hills. The action, however, proved to be a feint. The main German force reassembled south of the Roubion River, advanced nine miles east, and then swung north, crossing the river and advancing on Puy St. Martin and Marsanne, behind Butler’s defenses. Almost unopposed, the Germans occupied Puy that afternoon, cutting the American supply line to Crest and Sisteron.

The German success was short-lived. By chance, Butler’s detachments at Gap and the Croix Haute Pass had been relieved by some of Stack’s forces on the 21st, and both had been traveling to rejoin Butler. The Gap group had just turned south from Crest on the afternoon of the 22nd, and its commander, realizing the implications of the German advance, quickly organized a tank-infantry counterattack into Puy. While Sherman tank fire blocked the roads leading from Puy to Marsanne, the unit from Gap cleared Puy that evening, destroying ten German vehicles but suffering no casualties.

Butler believed that the German attack was only a probe to determine his strength, and he expected a much stronger assault on the following day, 23 August. Still no units of the 36th Division had arrived during the day. The only forces joining him on the 22nd were his own detachments from Gap and the pass and two 155-mm. battalions of VI Corps artillery. Equally important, his own artillery and armor were dangerously low on ammunition, with about twenty-five rounds per gun. To preserve his position, he needed both reinforcements and resupply.

Reinforcing the Square

Around 2200 on the evening of the 22nd, as Butler was beginning to despair, a single battalion of the 141st Infantry arrived along with the regimental commander, Col. John W. Harmony. Harmony quickly brought Butler up to date on the situation in the rear. Throughout the previous day, 21 August, he explained, General Stack had been waiting at Sisteron to learn whether to move the 143rd Infantry to Grenoble or Montelimar. Dahlquist, the 36th Division commander, had not yet been able to determine where Truscott wanted the Rhone blocked. Although ready to push the 143rd north to Grenoble or west to Montelimar, he had also ordered the 142nd Infantry to Gap to protect his eastern flank and had sent Harmony’s 141st regiment initially to Sisteron to serve as his reserve. Unconfirmed intelligence reports still placed the 157th Reserve Mountain Division in the Grenoble–Gap region, and an attack on the 36th Division’s northeastern flank thus remained

a possibility. Dahlquist had then altered these plans on the evening of the 21st, judging that the 143rd was too oriented on Grenoble to assist Butler and giving the mission to the 141st. Harmony related that his regiment, the last major unit of the 36th Division to displace north, had arrived in the Sisteron–Aspres area only on the morning of the 22nd and, due to the general shortage of vehicles, had not been able to advance much farther. Using captured German fuel stores, he had finally managed to bring the one battalion with him to Marsanne, but did not expect the rest of his units to reach the Montelimar area until the following day. In the meantime, Butler would have to make do with this limited reinforcement.

The lack of reinforcements reflected American indecision. Throughout the day and evening of 21 August neither Patch nor Truscott had been willing to make Montelimar the major effort. They were still unable to predict when Toulon and Marseille would fall or confirm the beginning of a complete German withdrawal up the Rhone valley. On the morning of the 21st, Truscott had ordered one regiment of the 45th Division—the 179th Infantry—to Sisteron, but had canceled the movement abruptly at 1330 when an ULTRA intercept informed him that units of the 11th Panzer Division had crossed the Rhone and were south of the Durance River.5 Although the radio intercept was accurate, the armored threat was just a ruse, for the 11th Panzers had been able to ferry only a few of their imposing machines across the Rhone.6 Nevertheless, the move apparently succeeded, for Truscott stayed his hand; it was not until 2300 that evening that he finally ordered Dahlquist to move on to Montelimar, and the next day before the 179th regiment resumed its movement north.

When Truscott’s orders arrived, late on the 21st, Dahlquist sent the rest of Harmony’s 141st regiment on its way west and, through the 22nd, tried to reorient the rest of his scattered division on Montelimar. To secure his northern flank, he decided to allow the 143rd Infantry to resume its advance on Grenoble, which Americans entered that afternoon, and then have it swing west and south, through the city of Valence, into the battle square.7 Transportation problems, however, hindered his efforts to accelerate the movement of the 141st to Montelimar, and to follow it with the 142nd regiment from Gap and the rest of the division. Impatient with these delays, Truscott arrived at the 36th Division command post near Aspres shortly before noon

and, finding Dahlquist absent, made his dissatisfaction clear to the division chief of staff, Col. Stewart T. Vincent. Noting the 143rd advancing on Grenoble, the 142nd at Gap and points east, and elements of the 141st just pulling into Aspres, he demanded that the entire division move to the Rhone “forthwith,” and attached the 179th regiment (45th Division) to the division for employment at Grenoble.

Upon returning to his own command post, Truscott composed a letter to Dahlquist with detailed instructions. Indicating his displeasure with the division’s deployments, he emphasized that “the primary mission of the 36th Division is to block the Rhone Valley in the gap immediately north of Montelimar.”8 Dahlquist was to push the entire 141st regiment to Montelimar as soon as possible; move the 179th to Grenoble and shift the 143rd from Grenoble to Montelimar; and march the rest of the 142nd west to the Montelimar–Nyons area to protect Butler’s southern flank. He also suggested that Dahlquist screen Butler’s northern flank by reconnoitering toward Valence above Montelimar. The 45th Division, he explained, would ultimately assume responsibility for the entire Grenoble–Gap–Sisteron region. Truscott appreciated Dahlquist’s logistical difficulties, however, and arranged to have the Seventh Army headquarters rush a special truck convoy of fuel to the north during the afternoon. This resupply, together with captured gasoline, allowed the bulk of the 141st, following Harmony, to resume its march west at 0330 early on the 23rd.

Late on the evening of the 22nd, about 2100, Truscott and Dahlquist hashed out their differences over a recently opened telephone line. Dahlquist recommended moving the 179th, rather than the 143rd, to Montelimar and even suggested sending the entire 45th Division there while the 36th dashed up to Dijon, 150 miles farther north. Truscott brushed aside these proposals, showed increasingly less sympathy for Dahlquist’s transportation problems, and again emphasized the need to block the Rhone valley near Montelimar, telling him to get his men there even if they had to walk. His one concession was to allow Dahlquist to move the 179th Infantry to the west in lieu of the 143rd.

Throughout the rest of the night and into the early morning hours of 23 August, Dahlquist continued to shuffle the growing number of units under his command into some kind of order. Lack of fuel and transportation rather than lack of manpower remained his key problem. Soon after conversing with Truscott, he directed the 142nd Infantry to start westward at once, traveling at night, not to the Nyons region southeast of Montelimar as Truscott had recommended, but rather to Crest and Butler’s area. Several hours later, however, Dahlquist countermanded the order and sent the 142nd to Nyons, where the leading elements arrived about 0730 on the morning of the 23rd.

Meanwhile, as the 179th Infantry was leaving Sisteron at 2230, 22 August, Dahlquist changed its objective from Grenoble to Montelimar, but, as the unit rolled into Aspres around midnight, he changed its destination

back to Grenoble. Once there, the unit was to relieve the 143rd Infantry, which would then move west to Valence and south to Montelimar. Again, the availability of fuel and vehicles dictated these troublesome changes, and Dahlquist and his staff labored to keep them to a minimum.

Dahlquist’s final orders for 23 August appeared to put his house in order at last. Pushing the 143rd to Montelimar through Valence would safeguard Butler’s northern flank, and deploying the 142nd into the Nyons area would cover Butler in the south; meanwhile, the movement of the 141st directly to Montelimar would receive priority, and the divisional units could follow as transportation became available. Truscott approved these final dispositions and also ordered the 180th Infantry, another 45th Division regiment, to the Gap area from where it and the rest of the division could follow the 179th to Grenoble and points north at some future date. As a result, the 45th Division was soon able to relieve the last 36th Division units in these areas, leaving Dahlquist free to devote his attention to the Rhone. But Truscott was still uneasy. To make sure that his operational concept was clearly understood by Dahlquist, he telephoned him once again at 0200 hours, 23 August, and reminded him that his task was to halt the German withdrawal. Not a single German vehicle was to pass Montelimar.

The German Reaction

The German commanders were quick to appreciate the dangerous situation. Late on 21 August German intelligence reports had convinced Wiese, the Nineteenth Army commander, that the Allied forces that had suddenly appeared above Montelimar posed a serious threat to his northward withdrawal.9 He responded by sending his most powerful and most mobile force, the 11th Panzer Division under Maj. Gen. Wend von Wietersheim, toward the troubled area. It was the division’s reconnaissance battalion that had probed Butler’s positions on the 22nd, while the rest of the 11th, less the force feinting toward Aix-en-Provence, began blocking the major roads to the Rhone coming from the east. But the action around Puy that afternoon, when Butler’s armor pushed light elements of the 11th Panzers back across the Roubion, further alarmed Wiese, who then ordered von Wietersheim to speed his entire division northward. The panzer division was to clear the high ground northeast of Montelimar and secure the main highway from Montelimar north to the Drome. Wiese also directed General Kniess, the LXXXV Corps commander still at Avignon, to reinforce Wietersheim’s unit with the 198th Infantry Division within twenty-four to forty-eight hours.

Fortunately for Butler, von Wietersheim found Wiese’s orders hard to execute. Fuel shortages, the presence of service and administrative traffic on the roads, and the difficulties of marching at night under blackout

conditions all delayed the movement of his division north. Groupe Thieme, the first major element of the division, reached Montelimar only at noon, 23 August, with a battalion of infantry, ten medium tanks, and a self-propelled artillery battery; the rest of the division was not expected to arrive before the 24th. Yet the Germans were determined to take the initiative. Although they were unsure of the exact strength of the American forces, they realized that every delay gave their enemy more time to build up his strength along their unprotected line of withdrawal.

In the Square (23–24 August)

On the morning of 23 August, Dahlquist dissolved Task Force Butler as a separate entity, but allowed Butler to remain in command of those forces in the battle square area. Butler planned to have the 141st Infantry, with the motorized battalion of the 143rd attached (one of the original components of Task Force Butler), take control of the Rhone front from the Drome River south to the Roubion. Initially he tasked one battalion to secure Hill 300; another, with tanks and tank destroyers, to strike southwest from Sauzet to seize Montelimar; and the two remaining battalions to serve as a reserve near Marsanne, helping to secure Hill 300 as necessary. Small forces were to patrol the main supply route from Crest to Puy, guard both banks of the Drome, and secure Butler’s southern flank on the Roubion. Butler also dispatched cavalry elements to the north and south in order to link up with 36th Division units on their way to Valence and Nyons. However, German activities and the late arrival of the 141st Infantry put most of these plans in abeyance.

Shortly after dawn on the 23rd, the Germans again attempted to take the initiative. Above Montelimar elements of the panzer division’s reconnaissance battalion, supported by a few tanks and self-propelled guns, infiltrated into Sauzet only to be thrown out by an American counterattack several hours later. About noontime, another small German armored column, repeating the maneuver of the previous day, struck across the Roubion River toward Puy St. Martin, but was also pushed back, this time by concentrated American artillery fire, Finally, Groupe Thieme entered the fray, moving from the Sauzet area toward the Hill 300 ridge, but again American forces resisted the pressure and held.

Uncertain of German strength and dispositions, the American counterattacks fared little better. About 1630 that afternoon Butler sent an infantry battalion, some service troops, and a few tanks southward through Sauzet to seize Montelimar. But the German defense was far too strong, and a counterattack halted the American drive at 1800 scarcely a mile short of the city. Thus neither side had accomplished a great deal during the 23rd.

Since the German withdrawal through the Montelimar area had not yet begun in earnest, Butler had not made a strong effort to interdict Route N-7 physically. Some ammunition had come up during the night, and the artillery units had engaged several German convoys on the highway, destroying nearly one hundred vehicles. But the need to conserve

shells for defensive fire and the uncertainty of resupply limited the effort. The Germans, for their part, had begun to sort out a potentially monumental traffic jam at Montelimar and had started some administrative and service organizations moving northward again. However, they had made little progress clearing the danger area, especially the all-important Hill 300. Both sides required more strength at Montelimar, and both expected stronger actions by their opponents on the following day.

Outside of the battle square, Dahlquist inexplicably had shown little urgency in moving the rest of his division to the Montelimar area on the 23rd. In the north, the 143rd Infantry did not leave Grenoble until 1730 and, although encountering no opposition, had stopped above Valence, more than twenty miles north of the Drome, that evening. In the south, the 142nd Infantry had two infantry and one artillery battalions in the vicinity of Nyons—twenty-five miles southwest of Montelimar—by midafternoon, but made no effort to move up to the battle square. Perhaps Dahlquist felt that the coming battle would not be limited to the square, and was thus wary of pushing his entire division into an area that might become a German noose. The earlier German attacks on Butler’s flank at Puy St. Martin supported this concern.

Dahlquist’s plans for 24 August were conservative. He ordered the 143rd to seize Valence and the 142nd to extend its covering line from Nyons to within ten miles southeast of Montelimar. Only later, sometime during the night, did he order the remaining battalion of the 142nd that had been left at Gap to move to Crest as soon as the 180th Infantry of the 45th Division relieved it. In the Montelimar Battle Square, Dahlquist wanted Butler to secure all the ground dominating the valley between Montelimar and the Drome River and, if possible, to capture the city itself. But without the direct support of the 143rd and 142nd regiments, Butler’s ability to block the Rhone valley physically and to handle German counterattacks at the same time was becoming questionable.

Wiese was more realistic. Throughout the 23rd, he repeatedly urged von Wietersheim to rush his panzer division up to Montelimar, and pressured Kniess to have the 198th Division follow as soon as possible. He recommended that the 198th relieve 11th Panzer Division outposts and roadblocks at least as far north as Nyons, and have a regiment at Montelimar by the morning of the 24th. Then Wiese wanted von Wietersheim to clear all American forces from the area using the entire 11th Panzer Division, the regiment of the 198th, and the 63rd Luftwaffe Training Regiment, which was then assembling at Montelimar.

Wiese’s subordinates had their own problems. At the time, Kniess was more concerned with having his corps across the Durance River that night, and made no provisions to deploy a regiment of the 198th up to Montelimar; von Wietersheim had to contend with crowded roads and shortages of fuel, and his armor arrived in the battle square area in dribs and drabs. Nevertheless, German strength in the Montelimar region on 24 August was enough to give Task Force Butler and the 36th Division considerable trouble.

Another American attack that morning by a battalion of the 141st Infantry from Sauzet toward Montelimar again ended in failure when German troops, striking from the west, first drove a wedge into the American flank, and then infiltrated a maze of small roads and tracks to threaten the unit’s rear. That evening, as Harmony attempted to withdraw the battalion, a second series of infantry-armor counterattacks struck the unit’s front and flanks, cutting the battalion off from Sauzet and dispersing many of the troops. American artillery broke up further German efforts, and the battalion managed to fight its way back to Sauzet, but, as German pressure renewed, the Americans again pulled out of the village and took positions on the southern slopes of Hill 430. The battalion lost about 35 men wounded and 15 missing, captured 20 Germans, and estimated killing 20.

Meanwhile, a few miles farther north, a second German attack had cleared several early morning American patrols from Route N-7, and then had slowly pushed scattered elements of the 141st Infantry off most of the Hill 300 ridgeline. By dark the American position had received a serious setback. Pleased, Wiese ordered von Wietersheim to finish the job on the following day with the rest of his units plus several battalions of the 198th Division, which the army commander had personally dispatched north.

Both Sides Reinforce

Behind the battlefield on the 24th, Dahlquist now directed the rest of his units into the battle square, still with less dispatch and more confusion than was called for. That morning, for example, he ordered the 2nd Battalion, 142nd Infantry (relieved of its defensive assignment at Gap), first to Crest, then to Nyons, and finally, as it entered Nyons at 1500, back to Crest. He then directed the rest of the 142nd regiment, still in the Nyons area, to follow and take up positions in the battle square along the Roubion River guarding the American southern flank. Meanwhile, between 1300 and 1830, Dahlquist dispatched no less than four contradictory directives—three by radio, one by liaison officer—to the 143rd Infantry still above Valence. The regiment started to receive them at 1600 in the wrong sequence. Not until 1900 did the regiment, reinforced by FFI units, get under way toward Valence only to be halted by German defenses on the outskirts of the town; and, as the American units reorganized for a second effort, another order arrived directing its immediate movement to Crest. Breaking contact, the 143rd left Valence to the FFI and the Germans, but were unable to reach Crest and the battle square until early the following morning, 25 August.

By this time Dahlquist was becoming more concerned with defending his own positions than in attacking Montelimar or blocking the Rhone highways. Expecting larger German attacks on the 25th, he tried to organize his forces into a tight defensive posture, with the 141st and 142nd regiments on line (the 141st on the high ground and the 142nd along the Roubion) and the 143rd and Task Force Butler, now reconstituted, in

reserve. The only offensive action planned for the next day was to have elements of the 141st attempt to cut Route N-7 at La Coucourde, several miles farther north of the previous day’s battles. Truscott, who had visited Dahlquist’s forward command post near Marsanne that day, wanted a more offensive role for Butler, but had approved Dahlquist’s plans, allowing the division commander to deploy his forces as he thought best.

The confusion in American command channels was far from over. About 2330 that night, 24 August, Dahlquist, concerned about protecting his flanks and rear, asked Truscott to send a regiment of the 45th Division to Crest early the next day. Although he had already instructed the 45th Division to move the 157th Infantry to Die, twenty miles east of Crest, Truscott refused the request, feeling that Dahlquist’s strength in the battle area was adequate. A few hours later, perhaps feeling that the division commander’s defensive concerns might lead him to abandon his main mission, Truscott reminded him that he still expected his division to block the main highway as soon as possible. His troops, Dahlquist radioed in reply, had been there during the day, and he assured Truscott that they were “physically on the road.”10 However, although small groups of American soldiers may have reached the highway from time to time, the implication that they controlled any portion of N-7 was inaccurate; at best, Dahlquist’s knowledge of his own troop dispositions may have been faulty.

On the German side, the fog of war had begun to dissipate a little. On the evening of the 24th a detailed copy of Dahlquist’s operational plans for 25 August had fallen into their hands, giving the German commanders their first clear picture of the forces opposing them at Montelimar.11 As a result, Wiese now decided to move the entire 198th Infantry Division to the north and form a provisional corps under von Wietersheim, consisting of the 11th Panzer and 198th Divisions, the 63rd Luftwaffe Training Regiment, the Luftwaffe 18th Flak Regiment (with guns ranging from 20-mm. to 88-mm. in caliber), a railroad artillery battalion (with five heavy pieces ranging from 270-mm. to 380-mm. in caliber), and several lesser units. With these forces he expected von Wietersheim to launch a major attack before noon on the 25th and sweep the American units away. At the same time, Wiese continued to urge Kniess to move his corps north as fast as he could. Having withdrawn the last of the LXXXV Corps across the Durance during the night of 23–24 August, and having executed another withdrawal the following night without pressure from the south, Kniess was about fifteen miles north of Avignon but still more than thirty-five miles south of Montelimar on the morning of the 25th. Success at Montelimar would be for naught if Kniess’ units were destroyed in the south.

While the rest of the 36th Division

entered the battle square that night, von Wietersheim, with Dahlquist’s order in hand, issued detailed instructions for his attack. He divided the units under this control into six separate task forces, four from the 11th Panzer Division—Groupes Hax, Wilde, and Thieme and the 11th Panzer Reconnaissance Battalion—and two from the 198th Division built around the unit’s 305th and 326th Grenadiers. The 198th Division, reinforced with armor, would conduct the main effort. The 305th Grenadiers, attacking northeast of Montelimar, were to seize the eastern section of Hill 430, seal the western end of the Condillac Pass, and then move northwest to Route N-7. Slightly to the east, the 326th Grenadiers would support this effort by striking across the Roubion near Bonlieu, marking the weakly held boundary between the 141st and 142nd Infantry, and then driving north. In the west, Groupe Hax, consisting of two panzer grenadier battalions and two battalions of the 63rd Luftwaffe Training Regiment, reinforced by artillery and tanks, was to support the 198th Division’s attacks by clearing the area north and northeast of Montelimar, the rest of Hill 300, and the western slopes of Hill 430. Meanwhile, Groupe Thieme, with one panzer grenadier battalion supported by tanks and the 119th Replacement Battalion, was to assemble at Loriol in the north and strike eastward along the south bank of the Drome River to Grane, five miles short of Crest; at the same time Groupe Wilde, consisting of another panzer grenadier battalion, an artillery battalion, and a few tanks, would relieve elements of Groupe Thieme outposting Route N-7 around La Coucourde. Von Wietersheim hoped that the 305th Grenadiers would be able to isolate the American infantry and artillery in the Hill 300–Condillac Pass area, while the 326th Grenadiers, coming up from the south, swept behind them and linked up with Groupe Thieme in the north, thus surrounding the entire 36th Division. Groupe Wilde, at La Coucourde, would act as a reserve, able to reinforce any of the various efforts or strike into the Condillac Pass on its own. Finally, the 11th Panzer Reconnaissance Battalion was again to push into the Puy St. Martin area, further disrupting American lines of communication. Taking advantage of the dispersion of Dahlquist’s units, his logistical difficulties, and the temporary numerical superiority of the German forces, the armored division commander hoped to destroy completely both Task Force Butler and the 36th Division. With this impediment out of the way, the German withdrawal could be easily accelerated and all delaying action could be focused on the U.S. 3rd Division slowly moving up from the south.

The Battle of 25 August

The German plan of attack was ambitious but exceedingly complex and depended greatly on the ability of the participating units to arrive at their assembly areas on time and ready for action. From the beginning, difficulties in communications and transportation made a coordinated attack, as envisioned by von Wietersheim, impossible. Groupe Thieme, setting out from Loriol around 1130, was the first unit under way. Pushing back outposts of the 117th Cavalry Squadron,

the attackers reached Grane before 1400, while other German forces seized Allex, on the north side of the Drome, at approximately the same time. Alarmed, Dahlquist sent Task Force Butler, now little more than a weak battalion combat team, north from Puy St. Martin about halfway to Crest to protect his main supply route; Butler, in turn, dispatched a tank platoon northwest over a mountain road toward Grane. Unable to retake Grane, the tank unit established a blocking position just south of the town, while a heterogeneous collection of infantry, reconnaissance, armor, and engineer units hurriedly set up roadblocks west of Crest on both sides of the Drome. Although this mixed force expected a major German effort against Crest to follow, no further German advances along the Drome took place that day. Groupe Thieme had accomplished its mission and was content to defend its gains.

Elsewhere German attacks accomplished much less. Groupe Hax, for example, did not start out until 1400, and then succeeded only in consolidating earlier gains above Montelimar. Groupe Wilde did not reach its assigned positions in the Hill 300–La Coucourde area until 1500, and the planned attacks of the 305th Grenadiers and the 11th Panzer Reconnaissance Battalion never even began. The only serious German threat in the south that day was the attack of the 326th Grenadiers in the Bonlieu area late in the afternoon. Although the grenadiers easily routed a company of the 111th Engineer Battalion which was holding the area, American artillery quickly broke up their advance and again forced the Germans back across the Roubion. The 1st Battalion, 143rd Infantry, part of Dahlquist’s reserve, entered Bonlieu at 2100 hours that night without opposition.

The American effort that day to cut Route N-7 turned out to be the most promising offensive action. Due to the early departure of Groupe Thieme and the late arrival of Groupe Wilde, the Germans had left the Hill 300–La Coucourde area nearly unprotected for much of the day. However, Harmony’s 141st Infantry was stretched thin along a six-mile front, and the regimental commander was unable to put together an attacking force until late afternoon. Finally, around 1600, while units of the 2nd Battalion, 143rd Infantry, secured the northern slopes of Hill 300, the 1st Battalion, 141st Infantry, moved west out of the Condillac Pass supported by some tanks and tank destroyers and struck out for La Coucourde. Despite the arrival of Groupe Wilde elements, the attack succeeded, and by 1900 one and later two rifle companies, four tanks, and seven tank destroyers were blocking the highway.

Whether the Americans could keep the block in place was critical. Until darkness halted observed fire, American artillery prevented the Germans from assembling forces for a counterattack, but Harmony doubted that he could hold the roadblock through the night. Increased German pressure across his entire front made it impossible to reinforce the blocking force, and he had considerable difficulty keeping it supplied. Accordingly, he suggested that the force retire into the pass for the night, blowing up several small bridges in the area before leaving, and

return in the morning. But Dahlquist, complying with Truscott’s orders, told him to maintain the block as long as possible.

At this juncture, von Wietersheim took a personal hand in affairs. Disgusted with the failure of his plans and especially with the inability of his forces to keep at least the highway open, he organized an armored-infantry striking force from units scraped up in the Montelimar–Sauzet area and led a midnight cavalry charge against the American roadblock. By 0100 on the 26th, German armor had dispersed the blocking force, knocking out three American tanks and six tank destroyers and driving what was left back into the Condillac Pass. After reopening the highway, Wietersheim swung some of his forces east to seize the high ground on the northern side of the pass to prevent the Americans from resuming their ground attacks on the highway in the morning. At the time, Harmony still had two rifle companies on the northern section of the Hill 300 ridgeline, but nothing strong enough to counter this new German force.

Once again the action at Montelimar ended in a stalemate. Dahlquist had still committed little of his strength in La Coucourde area, and most of his 142nd and 143rd Infantry had seen no action. With so much American strength held in reserve or in supporting defensive positions, the inability of Dahlquist and Harmony to interdict the highway—their main mission—was not surprising. But Wietersheim had done little better. His grandiose attack plans had gone nowhere and, in the end, had only spread his forces out over the periphery of the battle square, nearly leading to his defeat in the center where it counted.

More Reinforcements

Additional American troops were on their way to the Montelimar sector. When Truscott learned of the German push toward Crest on the 25th, he directed the 45th Division to send the 157th Regimental Combat Team and the 191st Tank Battalion north to the battle square area. Taking a southerly route via Nyons, one battalion and most of the tanks reached Marsanne about 2200 on the 25th; the rest of the regiment along with one tank company began closing on Crest early the following morning. Truscott attached the units at Marsanne to the 36th Division, instructing Dahlquist to use them as his reserve, and ordered the rest of the force to remain at Crest as the corps reserve.

Meanwhile, late on the 25th, Dahlquist began planning for a limited offensive on the following day. He wanted Task Force Butler to attack first west from Crest along the south bank of the Drome and then south along Route N-7 to the Condillac Pass. At the time, Harmony’s 141st Infantry was still maintaining its roadblock near La Coucourde, and it appeared that no more Germans would reach the Drome. Nevertheless, expecting stronger German counterattacks on the 26th in the southern sector of the battle square, Dahlquist continued to deploy his main strength, the bulk of the 142nd and 143rd regiments, and the recently arrived battalion of the 157th with its attached tanks in reserve or in defensive

positions along his northern and southern flanks.

In the early morning hours of 26 August, American tactical plans again underwent a major revision. The dispersion of the 141st regiment’s roadblock at La Coucourde prompted Dahlquist to change Butler’s mission, and he subsequently directed the task force to launch an attack at daylight from the western exit of the Condillac Pass to restore the roadblock. Butler’s attack was still the only offensive action that Dahlquist planned for the 26th.

The Germans were also changing their plans. Late on the 25th von Wietersheim directed the 110th Panzer Grenadiers, previously split between Groupes Hax and Thieme, to displace north of the Drome and protect the routes of withdrawal beyond the river. At the same time he notified Wiese that he felt unable to retain command of the provisional corps and devote sufficient attention to his own division. Wiese, unhappy with the conduct of operations that day, agreed and assigned most of the remaining forces in the Montelimar sector to the LXXXV Corps, directing Kniess to continue the attacks against the American forces in the area on the 26th. For this purpose, he allowed Kniess to employ Groupes Hax and Wilde, both reduced to a single panzer grenadier battalion but each reinforced with tanks.

On 26 August Kniess planned to renew the attacks north and northeast of Montelimar between Hill 300 and the Bonlieu area with the 198th Division’s 305th and 326th Grenadiers. He expected Groupe Wilde to keep Route N-7 open and placed Groupe Hax in reserve near Montelimar. He also wanted the withdrawal of the rest of his corps speeded up. Still well south of Montelimar were the 308th Grenadiers plus other elements of the 198th Division; the 338th Division, less one regiment traveling up the west bank of the Rhone; several field artillery and antiaircraft battalions; some combat engineer units; and a host of lesser combat and service units of both the army and air force. Kniess had good reason for concern. Late on the 25th the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division had caught up with several LXXXV Corps elements north of Avignon, and he had no way of predicting the speed of the American advance north. Accordingly, he canceled existing plans for a phased withdrawal and directed the 338th Division to begin a forced march that, he hoped, would bring it to Montelimar early on the 26th. The 669th Engineer Battalion, reinforced, was to man rear-guard blocking positions to cover the corps’ withdrawal and delay the 3rd Division.

In the south, the 3rd Division had started north on the 25th after receiving orders from Truscott to push reconnaissance patrols across the Durance and prepare for a drive on Montelimar. But the progress of the division was continually delayed by general transportation problems and the necessity of waiting for French units to take over American positions south of the Durance. Leading elements of the 3rd Division reached Avignon about 1400, 25 August, and, finding the Germans gone, moved fifteen miles farther north to Orange where, about 1730, they ran into the German rear guard. Under pressure from Truscott to strike northward

with all possible speed, General O’Daniel, the division commander, planned to bring his main strength up to the Orange–Nyons area on the 26th, and continue northward with two regiments abreast—the 15th Infantry along the Rhone and the 30th Infantry to the east. But, like Dahlquist, he lacked the fuel and transport to move quickly.

Battles on the 26th

Well before the 3rd Division resumed its march north on 26 August, Task Force Butler, after a grueling night march, assembled in the Condillac Pass, ready to drive west toward the highway. The new American attack developed slowly against scattered but determined German resistance. After a few initial patrols toward La Coucourde failed to reach Route N-7, Butler sent two rifle companies of the 3rd Battalion, 143rd Infantry, over the northern nose of the Hill 300 ridgeline around 1330; and as they started down the northwest slope toward the highway, he reinforced them with a platoon of medium tanks and a few tank destroyers moving directly out of the pass. Skirmishing with German infantry most of the way and harassed by German artillery fire, these forces butted into Groupe Wilde, which had moved up from the south and swung east toward the pass. Simultaneously, other German forces attacked from the north, and indeterminate fighting continued throughout the entire area until dusk when the American armor finally pulled back into the pass for the night, leaving the two infantry companies clinging to the northern slope of Hill 300. Another attempt to cut Route N-7 had failed, and again the primary reason for the failure was the inability of the 36th Division to commit sufficient strength at the crucial point.

The German attacks on the 26th were even less successful. In the Montelimar corner of the battle square, Kniess’ offensive began at 1130 with a lone battalion of the 305th Grenadiers moving toward Hill 430 and was quickly repelled by American artillery and tank fire. A second German attack at 1530 in the Bonlieu area, again hitting the crease between the 141st and 142nd regiments, penetrated a little over a mile north of the Roubion, but was also stopped by American artillery, and the position was restored by counterattacks of the 1st Battalions of the 142nd and 143rd regiments, both pulled out of reserve. In the northern sector of the square, the 11th Panzer Reconnaissance Battalion broke through American roadblocks to come within two miles of Crest, but was too weak to press home the attack; during the afternoon, units of the 157th Infantry helped restore American blocking positions near Grane and Allex.

The German Withdrawal (27–28 August)

During the 26th, American artillery managed to block the road and rail lines along the Rhone intermittently, but, still short of ammunition, was unable to halt the steady stream of German foot and vehicle traffic that continued up the valley and across the Drome. Although much of the movement consisted of artillery, antiaircraft, and service units, it also included

major combat units. Dawn on the 27th found all of the 110th Panzer Grenadiers, the 11th Reconnaissance Battalion, the 119th Replacement Battalion, most of the 119th Panzer Artillery Regiment, and part of the 15th Panzer Regiment (Groupe Thieme) safely north. Guarding the Drome crossings were Groupe Wilde and units of the 305th Grenadiers, while south of the Hill 300 bottleneck were Groupe Hax, the bulk of the 198th Division, the 338th Division, and—mainly on Hill 300—the 63rd Luftwaffe Training Regiment. The 338th had not moved north as rapidly as Kniess and Wiese had hoped, and it had only begun to arrive at Montelimar after dark on the 26th. However, the pursuing 3rd Division proved even slower and, beset by severe fuel shortages, was ten miles short of Truscott’s objective by dusk of the 26th and still fifteen miles south of Montelimar.

Although not surprised by Dahlquist’s failure to block N-7, Truscott had about lost patience with the division commander. Arriving at Dahlquist’s headquarters on the morning of the 26th, Truscott intended to relieve him, complaining that his situation reports had proved erroneous and that he had failed to carry out his main objective, interdicting the German withdrawal.12 According to Truscott, Dahlquist explained that in the confusion of battle his subordinate units had sometimes misinformed him regarding their locations and progress, and that continuous German attempts to strike at his supply routes at Crest and Puy had occupied much of his reserve force. Shortages of transportation, fuel, and ammunition were also constant problems, and the net result had been the impossibility of concentrating sufficient combat power to hold the ridgeline on Hill 300 or to establish a permanent block across the highway in the face of several desperate German divisions. Somewhat mollified by a firsthand look at the terrain, Truscott decided not to take any action against Dahlquist for the moment, but remained unhappy with the state of affairs.

At the conclusion of the conference Truscott directed Dahlquist to employ Task Force Butler once again to establish a roadblock near La Coucourde and then, if possible, move the force north across the Drome and then east to Crest to close all of the Drome crossing sites. He also suggested that Butler could then head north, bypass Valence, and take Lyon, thereby preventing the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps from crossing to the east side of the Rhone north of Montelimar. For this purpose, he gave Dahlquist permission to use the 3rd Battalion, 157th Infantry, and its attached armor as he saw fit, but Truscott retained the main body of the 157th Infantry under his own control, directing it to move west on the north side of the Drome to help Butler close the crossing sites. Truscott also hoped that O’Daniel’s 3rd Division could push substantial strength into the Montelimar area on the 27th to relieve some of Dahlquist’s units.

Much to Truscott’s disappointment, the fighting on 27 August was inconclusive. Butler, strengthened by the 3rd Battalion, 157th Infantry, again pushed west from the Condillac Pass

toward Route N-7, starting a battle that seesawed back and forth all day and that ended in failure for the Americans. During the afternoon, mixed elements of the 141st and 143rd Infantry managed to push the Germans off the eastern slopes of Hill 300, but German infantry held on to the remainder of the ridge for the rest of the day. To the south, further German attacks against 141st Infantry units on Hill 430 were repulsed but, worried about another German attack on his southern flank, Dahlquist kept most of the 142nd Infantry idle in defensive positions along the Roubion. Meanwhile, in the north, American elements entered Grane late on the 27th without opposition and the 157th Infantry cleared Allex; but neither force was able to move any closer to the Livron–Loriol area that day. South of the battle square, the 3rd Division’s northward advance was still hampered by continued transportation problems as well as by roadblocks of mines, booby traps, felled trees, destroyed bridges, and other obstacles, and by evening the unit was still four miles short of Montelimar.

On the German side Wiese had become increasingly nervous at the steady northern progress of the 3rd Division and the slow speed of the LXXXV Corps withdrawal. He had expected to have all his units across the Drome by nightfall, except the 198th Division. Instead Kniess had kept Groupes Hax and Wilde south of the Drome and had committed part of the 338th Division to what the Nineteenth Army commander felt were fruitless attacks against Hill 430 and the Condillac Pass. Meanwhile, German matériel losses in the battle square were mounting at a rate that Wiese considered alarming. Route N-7 was littered with destroyed vehicles, guns, and dead horses; the railroad was blocked with wrecked engines and cars, including those of the railway artillery battalion. Personnel losses had also risen sharply on the 27th, not only from American bombardments but also as a result of Kniess’ unprofitable attacks.

At dusk on the 27th Wiese directed Kniess to pull the 338th Division and Groupes Hax and Wilde across the Drome at all costs on the 28th. The 198th Division and the rear-guard engineers were to continue to hold back the 3rd and 36th Divisions and, once the other units were across the Drome, to escape as best they could.

If Wiese was pessimistic, Truscott was still optimistic. On the basis of overly enthusiastic messages from Dahlquist on the 27th and erroneous intelligence reports, Truscott believed that major portions of the LXXXV Corps had been destroyed south of the Drome and that only remnants of three German regiments remained in the Montelimar area. Equally significant, he knew that the French had now cleared nearly all of Toulon and Marseille without much of a fight, and the remaining German forces in both ports were expected to surrender formally at any moment. It was time to begin the drive to northern France in earnest. He therefore gave orders for the 3rd and 36th Divisions to mop up the area between the Drome and Roubion rivers on 28 August, for Task Force Butler and the 157th Infantry to occupy Loriol and Livron, and for units of the 45th Division to begin moving north from Grenoble

toward Lyon. He expected both banks of the Drome to be in American hands by noon, and hoped that the 36th Division could start one regimental combat team north before dark.

Truscott soon discovered that he had greatly overestimated the speed of the German withdrawal and underestimated the strength of their forces still south of the Drome. When units of the 141st Infantry, now commanded by Lt. Col. James H. Critchfield,13 tried to advance toward Montelimar on the morning of the 28th, they were quickly repelled by the 198th Division’s 308th Grenadiers supported by heavy artillery and mortar fire; Critchfield spent the better part of the day trying to extricate two of his attacking infantry companies that had been surrounded. Task Force Butler’s drive on Loriol was equally unsuccessful. Now built around the 3rd Battalion, 157th Infantry, the task force ran into heavy German tank and antitank fire at Loriol, losing three medium tanks and two tank destroyers within a few minutes, which forced Butler to pull back at once. North of the Drome the 157th Infantry did little better when stubborn resistance from the 110th Panzer Grenadiers reinforced with tanks stopped their attack just short of Livron.

Meanwhile, in the center, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 143rd Infantry, spent most of the day defending American positions in the area of Hills 300 and 430 and the Condillac Pass. Although American artillery continued to shoot up German traffic along the road, the effort to block the highway with ground troops in the area of La Coucourde was not resumed. To the south, units of the 3rd Division, which had conducted a day-long running engagement with the German rear guard, entered the southern outskirts of Montelimar that evening, but were unable to secure the city until the following morning, 29 August.

Although the Germans had again frustrated American attempts to cut their route of withdrawal during the 28th, their losses in men and matériel continued to multiply. South of Montelimar the 3rd Division overran a column of some 340 German vehicles and took almost 500 German prisoners. Moreover, although Groupe Hax, part of the 933rd Grenadiers, and elements of the 338th Division’s artillery and special troops had arrived safely across the Drome, Kniess was unable to move either the 338th Division or Groupe Wilde northward. Instead he was forced to commit Groupe Wilde and the 338th’s 757th Grenadiers at Loriol to hold back Task Force Butler; to use a battalion of the 933rd Grenadiers, 338th Division, and another from the 305th Grenadiers, 198th Division, to secure the high ground between the Condillac Pass and Loriol; and to retain other elements of the 305th and the 63rd Luftwaffe to hold at least a portion of Hill 300. At dusk these units were still in place, while the main body of the 198th Division was concentrated a few miles north of Montelimar, just above what was left of the rear-guard engineer battalion.

End of the Battle

With Groupe Wilde and elements of the 338th Division protecting the Drome crossings near Livron and Loriol, Kniess ordered Brig. Gen. Otto Richter, commanding the 198th Division, to break out of the battle square during the night of 28–29 August and the morning of the 29th. For the escape, Richter decided to divide his forces into three tactical columns, each built around one of his grenadier regiments and each moving north during the early hours of the 29th by a separate route. On the west a column led by the 305th Grenadiers was to move directly up Route N-7; two other columns, one centered around the 308th Grenadiers and the other around the 326th Grenadiers, were to push up separately through the valley between Hills 300 and 430 and try to swing back to the highway near La Coucourde.

Meanwhile Dahlquist, intent on resuming his clearing operations that night, ordered the 141st regiment to again strike south against Montelimar, supported by the 143rd Infantry, which was also to advance toward the city through the valley between Hills 300 and 430. In addition, he ordered Task Force Butler to make another attempt against Loriol at first light, and directed the 142nd Infantry, which had replaced the 157th north of the Drome, to continue west through Livron to block the Drome fords. Inevitably the opposing forces would clash head on.

As units of the 143rd Infantry moved south through the Hill 300–430 valley in the early hours of 29 August, their leading elements ran into the two columns of the 198th Division moving north. In the violent night melee that followed, some of the German soldiers managed to break through the American lines and, under constant fire, reach Route N-7 by morning; most, however, were either killed or captured during the lengthy skirmish, just about ending the effectiveness of at least two of the three 198th Division regiments. Meanwhile the 305th’s column, which was supposed to wait until the other groups had cut back onto the highway, left early during the night and made good its escape directly up Route N-7 without opposition.

As daylight broke on the morning of the 29th, the 141st Infantry resumed its drive on Montelimar, policing stragglers of the 198th; capturing General Richter, the division commander; and joining forces with the 3rd Division’s 7th regiment coming up from the south. During the final fighting of 28–29 August, the three converging American regiments captured over 1,200 Germans (including about 700 by the 143rd Infantry in the area of the Hill 300–430 valley) while suffering 17 killed, 60 wounded, and 15 missing. The 15th Infantry, 3rd Division, clearing Montelimar, captured another 450 Germans; and the 3rd Division’s 30th Infantry, which continued mopping up during the day, took several hundred more. On the 30th, those 3rd and 36th Division units remaining in the battle square swept the entire area, taking nearly 2,000 additional prisoners.

To the north, along the Drome, the 142nd Infantry cleared Livron by 0930 on the 29th, and, despite stiff German opposition, Task Force Butler secured

Loriol during the afternoon. However, neither force could make a final push to the Rhone that day to stop Germans who were still crossing at a few small fords. These eleventh-hour German escapees still had some punch left, and during the night they swallowed up two American roadblocks, capturing 35 American troops. Total casualties during the 29th for the two attacking American forces on the Drome were about 13 killed, 69 wounded, and 43 missing, but approximately 550 more German soldiers were prisoners.

For the Nineteenth Army, 29 August was the last day of cohesive action in the battle square. As long as they could, German soldiers continued to flee over the Drome River in ones and twos and disorganized groups. Groupe Wilde pulled out during the early afternoon, as did what was left of the 338th Division, followed later in the day and into the evening by those elements of the 198th Division that had managed to break through from the south. This last-minute success, however, came at the expense of other German units, such as the 757th Grenadiers, that were virtually destroyed during the day trying to protect the Loriol–Livron crossings.

The battle officially ended on the morning of 31 August when the 142nd regiment finally reached the Rhone River, clearing the north bank of the Drome and capturing 650 more Germans in the process. Although exhausted and thoroughly disorganized, the Nineteenth Army had managed to save the bulk of the 11th Panzer Division, Kniess’ LXXXV Corps with two greatly weakened infantry divisions, and a host of miscellaneous units, parts of units, and individual groups of army, air force, navy, and civilian personnel. West of the Rhone, the bulk of the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps, including the understrength 716th Infantry Division and an assortment of units under the 189th Division, had pulled abreast of Montelimar as early as 26 August and had also continued north, led by the 71st Luftwaffe Infantry Regiment, which, fleeing in disarray, had already reached Lyon. At Vienne, fifty miles north of the Drome, the corps crossed the Rhone, joining the LXXXV Corps’ flight northward with elements of the 11th Panzers constituting a new rear guard. The battle of southern France was over, and the race for the German border had begun.

Montelimar: Anatomy of a Battle

Was Montelimar an Allied victory, a German victory, or something in between? Casualty figures tell part, but by no means all, of the story. American units involved in the battle suffered 1,575 casualties—187 killed, 1,023 wounded, and 365 missing. These losses, representing well under 5 percent of the American strength ultimately committed, hardly seem heavy considering the size of the forces engaged, although the concentration of casualties in a few infantry battalions of the 141st and 143rd regiments attests to the bitterness of some of the fighting and the length of the conflict.

German losses were considerably higher. American forces engaged in the attempt to cut the Rhone valley escape route captured some 5,800 Germans from 21 through 31 August.

Of these, about 4,000 were from LXXXV Corps units and most of the remainder from assorted Luftwaffe elements. In addition, the withdrawal along the east bank of the Rhone cost the German Army about 600 men killed, 1,500 wounded, and several thousand others missing during the same time period. West of the river, the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps lost approximately 270 killed, 580 wounded, and 2,160 missing, mostly due to air attacks, FFI operations, and the general disorganization that characterized the movement north.

Taking into account all available information, the German Army units moving up the east bank of the Rhone suffered about 20 percent casualties. More important, most of these losses came from front-line combat units, greatly reducing their effective combat strength, which was defined by the German Army as fighting troops forward of the infantry battalion headquarters. For example, the 338th Division (omitting the attached 933rd Grenadiers) was down to 1,810 combat effectives by the 31st, and the 198th Division was reduced to about 2,800. In addition, both units had lost much of their artillery as well as substantial quantities of other equipment, such as vehicles, radios, crew-served weapons, and small arms. Thus, although the total manpower, or “ration,” strength of these units might have been considerably more than their combat effective strength—as determined by German accounting—they could assemble little more than a single, weak regimental combat team apiece for action. At the end of the month, the U.S. Seventh Army intelligence thus rated the 338th Division as only 20 percent effective but, over-generously, put the equally damaged 198th at 60 percent.

In contrast, the 11th Panzer Division, the “Ghost Division,” survived the Montelimar withdrawal in relatively good condition, suffering no more than 750 casualties and arriving at Vienne with about 12,500 effectives. The unit also brought out 39 of its 42 artillery pieces, over 30 of its 40-odd heavy tanks, and 75 percent of its other vehicles. With accuracy, the Seventh Army G-2 rated the panzer division as 75 percent effective. However, the 11th had not really done much during the campaign. While serving as the Nineteenth Army’s reserve, it had only been committed to battle briefly and had led, rather than followed, the main German withdrawal, with disastrous consequences for the less mobile infantry divisions.

Despite the heavy German losses in personnel and equipment, the escape of the Nineteenth Army was a disappointment for Truscott, Dahlquist, and Butler. Truscott, looking back on his experiences in the Italian campaign, was acutely aware of the need to destroy or at least damage the retreating German forces as severely as possible. From the beginning, the oblique advance to the Grenoble–Montelimar area had been a gamble, one that attempted to take advantage of the hasty German withdrawal as well as the failure of Wiese to protect the flanks of his narrow route of retreat. The courageous assistance of the FFI—harassing German detachments, providing valuable local intelligence to the advancing Americans, and augmenting their combat forces whenever possible—was another advantage

enjoyed by the Allies that is often overlooked. But the inability of the Allied commanders to concentrate their limited forces early enough at a single point—at Montelimar or, had circumstances dictated otherwise, perhaps Loriol, Valence, or even farther north—made it extremely difficult to stop the withdrawal, especially considering the strong German response once the danger was perceived. Allied logistical problems in the north—particularly the shortage of transport—caused by the rapid success of the landing itself, also reduced the flexibility of the northward thrust and made an earlier decision on a focal point necessary. Had this been done, the Seventh Army might have been able to push more fuel and ammunition up to the battle square in support, and Butler and Dahlquist might have been able to throw much more of their strength in the Hill 300–La Coucourde area sooner. But until a firm decision was made to focus on Montelimar and was communicated to all participants, the tactical commanders could not begin to close the Rhone valley escape route. As a new division commander and one who was unfamiliar with Truscott’s methods of operation, Dahlquist was unsure of himself and needed more guidance. At the time, he blamed himself for allowing the Germans to escape, feeling that he had had “a great opportunity” and had “fumbled it badly.”14 But, operating on a logistical shoestring, the so-called hard-luck 36th Division had at least given a beating to almost every retreating German division, forcing them to run a gauntlet they would not quickly forget.

The Seventh Army’s logistical problems were not mysterious. Its rapid progress inland had created a gasoline shortage as early as D plus 1; by 21 August the three American divisions alone required approximately 100,000 gallons of fuel per day. At the time there was a surplus of ammunition in the beachhead area, but the three beach fuel dumps had only about 11,000 gallons of gasoline left between them. Using captured fuel stores at Draguignan, Le Muy, and Digne (26,000 gallons) helped somewhat, as did severe rationing, but there was no easy solution. Employing the 36th Division’s trucks to motorize Task Force Butler only compounded both the fuel and vehicle shortage within the Allied command. As a result, the Seventh Army and the VI Corps lacked the wherewithal to assemble Task Force Butler and the 36th Division quickly at Montelimar and support the force with adequate rations, fuel, and munitions from the beach depots 200 miles to the rear. Although the ammunition expenditures of American artillery units in the Montelimar area were approximately three times higher (about ninety 105-mm. and thirty 155-mm. rounds per tube per day) than elsewhere, there was never enough to support these infantry and armored units adequately or to interdict the highway by fire alone.15

From Patch’s broader perspective, the results were more satisfying. His

army’s main objective—securing the ports of Toulon and Marseille—had been accomplished in record time, but it was a task that had kept most of the Allied combat power—including vehicles, fuel, and munitions—well south of the Durance. Patch’s priorities forced first Butler and then Dahlquist to grapple with the more powerful German units at Montelimar with little direct support. Although they subsequently failed to halt the German retreat, both Task Force Butler and the 36th Division acquitted themselves well against often superior German forces that continually attempted to outflank their blocking positions. The ensuing battle greatly sapped the strength of the remaining German units, while having little effect on the American forces involved. The action also forced Wiese to use his most mobile force, the 11th Panzer Division, at Montelimar rather than as a rear guard. As a result, the 3rd Division had a relatively easy time following the Germans up the Rhone, while the capture of Grenoble and its subsequent occupation by 45th Division units that were poised to strike even farther northward was an added bonus.

On the German side, General Wiese had managed to save much of his army, in part due to the early decision of OKW to withdraw German forces from southern France. However, he could not have been too happy over either the Montelimar episode or the rapid fall of the Mediterranean ports. His own failure to secure the flanks of the Nineteenth Army’s withdrawal was the result of poor planning and poor intelligence. Aside from the capture of the 36th Division’s order of 24 August, similar difficulties beset the German commanders throughout the battle. As a result, they rarely had a clear idea of the strength and dispositions of the forces opposing them at Montelimar and were unable to take advantage of weak points in the American lines. Like the Americans, the Germans suffered from an inability to concentrate sufficient strength at the crucial time and place, and were thus unable to exploit local tactical successes. Piecemeal commitment of battalions, small task groups, and hastily assembled provisional units characterized German efforts throughout the battle. Moreover, the German commanders often spread out these forces over a broad front on terrain that generally favored the defense. Had they concentrated on holding the Hill 300 ridgeline and directing the remainder of their available strength at one of the American flanks—Crest or Puy, for example—they might have been able to extract much more from the south and, at the same time, deal a severe blow to their pursuers. Thus, while Montelimar was certainly not the victory that Truscott had hoped for, it highlighted serious German military weaknesses as well as demonstrated the willingness of Allied commanders to undertake a certain degree of risk and initiative at the operational level of war.