Chapter 10: Pursuit to the North

With its rear area secure and the Germans in full retreat, the Seventh Army’s next objective was to move northward as rapidly as possible and join Eisenhower’s SHAEF forces by linking up with General Patton’s Third Army, which was operating on Eisenhower’s right, or southern, wing. While French units policed up the port cities, Patch’s staff began pushing more supplies to Truscott’s VI Corps units to support the trek north. At the same time, the influx of troops, supplies, and equipment over the original landing beaches continued, with the remainder of the French combat units gradually coming ashore along with the rest of the American logistical and administrative support units. As all these forces sorted themselves out, it was evident that the Seventh Army had become almost inadvertently involved in a race to northeastern France against what remained of Wiese’s Nineteenth Army, as well as the rest of Army Group G’s forces fleeing from western France. The German goal was to reach the area in front of the Reich border before the Allied advance, join with Army Group B, and present a unified front to the invaders. As a result, from the last days of August to mid-September, the two opposing armies in southern France raced up the Rhone valley and proceeded northward, one after the other—each often more concerned with reaching its objective than in impeding the progress of the other. Clashes between the two forces were, however, unavoidable.

Allied Plans

On 25 August, as the battle of Montelimar was reaching its climax, Patch was already issuing orders that outlined his plans for future Seventh Army operations.1 In accordance with preassault concepts, he intended to have Truscott’s VI Corps drive rapidly northward, first to the city of Lyon, 75 miles up the Rhone from Montelimar, and then to Dijon, 110 miles farther. Subject to later arrangements with Eisenhower, VI Corps would then strike northeast from Dijon 160

miles to Strasbourg on the Rhine. The tasks assigned to de Lattre’s French forces were more complex. The French would first complete the seizure of Toulon and Marseille; second, screen the area west of the Rhone, pushing reconnaissance elements north along its west bank; and third push north and northwest on the right of the VI Corps, moving into Alsace and the upper Rhine valley through the Belfort Gap, about 90 miles east of Dijon. Finally, the 1st Airborne Task Force would continue to screen the Franco-Italian border area assisted by French forces when available.

For the immediate future Patch’s orders of 25 August specified that the airborne force, continuing to operate under the direct control of the Seventh Army, would secure the army’s east flank from the mouth of the Var River near Nice, north into the Alps about 60 miles to the Larche Pass. The VI Corps, in addition to fighting it out at Montelimar, was to push east, northeast, and north to a line extending about 130 miles northwest from the Larche Pass through Grenoble to Lyon. The French units would receive their own operational sectors as their forces became available for the drive north.

On 28 August, with the Montelimar episode nearing an end, Patch issued more specific guidance, repeating his desire to have the VI Corps start its drive north to Dijon as soon as possible and confirming Lyon as Truscott’s immediate objective. West of the Rhone the French were to reconnoiter 100 miles west and southwest of Avignon, while pushing forces northward in support of the Lyon attack. East of the Rhone, de Lattre’s forces, Army B, were to support the right flank of the VI Corps by moving north through Grenoble and east of Lyon, before turning their advance toward the Belfort Gap and the Rhine. In addition, Patch instructed de Lattre to relieve the airborne units and any other American forces in the area of the Franco-Italian border.

General de Lattre was understandably upset with these instructions. If followed, they would divide what was to become the First French Army into several parts—two protecting the Seventh Army’s extreme eastern and western flanks, and two others on either side of the VI Corps supporting its drive to Lyon. With such dispersion de Lattre doubted whether he could project much of a force into the Belfort Gap area, especially with his weaker logistical organization. He put these arguments to Patch, and the two subsequently reached a compromise. The 1st Airborne Task Force would continue to hold the area from the Mediterranean to the Larche Pass, but de Lattre would accept responsibility for the border region north of the pass. West of the Rhone, Patch conceded that the “reconnoitering” of southwestern France could be done by a small reconnaissance force assisted by FFI elements; de Lattre agreed to send both the French 1st Armored Division, now unified under Maj. Gen. du Touzet du Vigier, and the 1st Infantry Division up the west bank of the Rhone as soon as they were available. East of the Rhone other French units would secure the VI Corps’ right flank, pushing north from Grenoble. However, after the fall of Lyon, the two French divisions

coming up the west bank of the Rhone would redeploy east of VI Corps and join the rest of the French forces, thereby uniting de Lattre’s army for a stronger drive on the Belfort Gap.

During the planning process, Patch viewed the capture of Lyon primarily as a stepping stone to the German border rather than as another chance to trap the retreating Nineteenth Army, and he paid relatively little attention to the German forces retiring across the Alps into northern Italy. But the Nineteenth Army’s line of withdrawal and Truscott’s aggressive temperament made it inevitable that the pursuing Americans would exploit every opportunity to destroy their retreating foe. Lyon represented the first focal point of such an effort. Situated at the juncture of the Saone and Rhone rivers, Lyon was the third largest city in France and an important road and rail center, whose seizure would have important logistical as well as propaganda value. The city also controlled the two most logical German routes of withdrawal. One route led northeast through the towns of Bourg-en-Bresse and Besancon to the Belfort Gap. Another went almost due north up the Saone valley to Dijon, from where Army Group G forces could continue north to join other German commands facing Eisenhower’s armies or could swing back east, either through Besancon or routes farther north, to the Belfort Gap. The longer Lyon–Dijon route was much easier and faster, while the Lyon–Besancon route, although shorter, offered many natural defiles that French and American forces could attempt to interdict as they had at Montelimar.

The Seventh Army’s G-2 section believed that the Nineteenth Army’s main body would follow the Lyon–Bourg–Besancon route of withdrawal because the Lyon–Dijon route would put the enemy forces in an area that was becoming a major battlefield. In contrast, Truscott’s corps staff estimated that Wiese’s forces would take the northern route to Dijon and then simply swing east, heading for the natural defenses of the Vosges Mountains. From the Vosges the Nineteenth Army could anchor its left, or southern, flank on Belfort and the Swiss border, while stretching its right out to Army Group B forces north of Dijon. French intelligence estimates generally agreed with this second assessment.2

The German Situation

The VI Corps’ projection proved accurate, for the bulk of the Nineteenth Army was indeed to head north from Lyon to Dijon. OB West ordered Army Group G to extend what would become its right wing northeast of Dijon toward the retreating Army Group B forces and establish a strong defensive line from Dijon through Besancon to the Swiss border. Such a line would not only secure the approaches to the Belfort Gap, but would also create a German pocket, or salient, west of the Vosges. At the insistence of Hitler and OKW, OB West intended to launch an armored counterattack from this salient against the

southern flank of Patton’s eastward-moving Third Army. Blaskowitz, the Army Group G commander, also wanted to hold the salient until the LXIV Corps, withdrawing from the Atlantic coast, could reach Dijon and strengthen the new line.3

With the Montelimar episode on their minds, both Blaskowitz and Wiese were also concerned with the possibility of the Seventh Army executing a wide envelopment northeast of Lyon in another attempt to trap their retreating forces. Erroneous reports that strong Seventh Army formations had already pushed east of the city increased their alarm. Almost equally worrisome was the news that the FFI had started a major uprising within the city, a development that could further retard the German withdrawal. On 26 August Blaskowitz accordingly had sped units north from the Montelimar sector to put down the Lyon uprising and suggested that Wiese pull the 11th Panzer Division out of the Montelimar battle to protect the Nineteenth Army’s flank east of Lyon. At the time the armored division was still fully engaged, however, and the best Wiese could do was direct the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps to accelerate its withdrawal all the way to Lyon and protect the LXXXV Corps’ route of withdrawal up the east bank of the Rhone.

Following the LXXXV Corps’ escape past Valence and Vienne during 29–30 August, Wiese arranged for a phased withdrawal through Lyon, assigning the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps the task of holding the city and controlling traffic through it. He intended to withdraw all of the rear-guard forces into the city on the night of 31 August, and have the bulk of the army start north up the Saone valley toward Dijon the following evening; he then intended to pull his rear guard out of Lyon on the night of 2–3 September after it had destroyed all bridges across the Rhone and Saone rivers in the area. During the exodus, the 11th Panzer Division was to guard the army against any flanking attack from the east—a threat that Wiese knew by the evening of 30 August had again become imminent.

North to Lyon

The Allied drive on Lyon was not as far advanced as the German commanders at first feared. On 25 August both Truscott and de Lattre were hard-pressed to round up any combat units for the thrust north. The bulk of the French forces were still clearing Toulon and Marseille, while most of Truscott’s VI Corps was deeply involved in the Montelimar battle. Nevertheless, on 26 August Truscott directed General Eagles, the commander of the 45th Division, to initiate reconnaissance toward Lyon from Grenoble, and on the 27th the two commanders agreed to start the 45th Division’s 179th regiment moving north on the next morning. To strengthen the effort, Truscott also ordered the 157th regiment, then in

the Crest–Livron area, to join the drive; for the same reason, he relieved the 180th regiment from the mission of securing the corps’ eastern flank. Now regarding any threat from the Franco-Italian border area as remote, he replaced the 180th Infantry with a small provisional task force made up of reconnaissance, mortar, and antitank units.

Patch’s directive of 28 August confirmed the VI Corps’ new objective, Lyon. Since the first French units were not due to arrive at Grenoble until the 30th, Truscott decided that his American units would have to make the drive alone. Speed was essential. Accordingly, he ordered Eagles’ 45th Division to seize Bourg-en-Bresse, lying northeast of Lyon, as soon as possible, while Dahlquist’s 36th Division, advancing directly north along the east bank of the Rhone, moved against Valence, Vienne, and finally Lyon. O’Daniel’s 3rd Division would follow the 45th, ready to reinforce either leading division if necessary. Truscott hoped that the dual drive would make the advance more flexible, would enable VI Corps units to sidestep German rear-guard defenses along the Rhone, and would ultimately offer him another opportunity to trap the retreating enemy if the Bourg-en-Bresse area could be taken early enough.

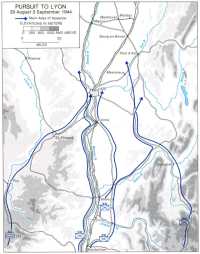

On 29 August, as the Nineteenth Army’s survivors trundled past Vienne, 15 miles south of Lyon, leading elements of the 45th Division bypassed the retreating Germans on the east and came abreast of the city. Encountering negligible resistance, the 45th Division forces captured two intact bridges over the Rhone 15 to 20 miles east of Lyon, and on the following days, 30 and 31 August, advanced 15 miles farther north to the town of Meximieux and then another 15 miles to Pont d’Ain on the Ain River (Map 10). Thus far, there had been no sign of the 11th Panzer Division or any other German security forces.

As Eagles struggled to bring the bulk of his division up to the Meximieux area, the rest of the VI Corps followed as rapidly as possible. By 31 August the 36th Infantry Division, closely followed by two regiments of O’Daniel’s 3rd, had also avoided the German rear-guard defenses by using roads east of the Rhone valley and was only about thirty miles from Lyon. In addition, the 3rd Algerian Division started north from Grenoble on the 31st, following in the wake of the 45th Division and reporting that there were no Germans on the VI Corps’ eastern flank. On 1 September the Allied concentration against Lyon continued, but early in the day the commanders of the leading American divisions began to sense the first German reactions to their rapid pursuit. At Dahlquist’s command post, FFI reports indicated that the Germans were constructing heavy rear-guard defenses just south of Lyon; meanwhile at Eagles’ headquarters subordinate commands notified the 45th Division staff that its outposts in the Meximieux–Pont d’Ain area were being probed by German armor. Obviously the Germans were more sensitive to threats to their rear or flanks than they had been before the battle of Montelimar.

Wiese had hoped that the 11th Panzer Division would have secured or destroyed all the Rhone and Ain river

Map 10: Pursuit to Lyon, 29 August–3 September 1944

bridges east of Lyon before the Americans could reach the area. This done, the task of covering the withdrawal of his two corps north to Dijon would have been fairly easy, with the panzer units slowly retiring directly to the northeast toward the Belfort Gap. But the early arrival of the 45th Division (or the late arrival of the 11th Panzers) complicated these designs. To protect his eastern flank, Wiese now ordered General von Wietersheim, the panzer division commander, to make a major effort to dislodge the American forces from the Meximieux area and to strengthen German outposts at Bourg, about fifteen miles above Pont d’Ain. His actions would have to be closely coordinated with Group von Schwerin, composed of remnants of the 189th Division and the 71st Luftwaffe Training Regiment, which had been charged with defending the southern and eastern approaches to Lyon itself.

Meanwhile, units of the 45th Division began assembling north of Meximieux on 1 September in preparation for a major attack on the 2nd, and the 117th Cavalry Squadron moved out to secure their right flank. The result was a series of disorganized engagements between elements of the 11th Panzers and 45th Infantry Division that lasted throughout the day. At Meximieux, a strong German infantry-tank force bypassed the American troops advancing north—probably by accident—and penetrated to the center of town. There, a desperate defense by two reserve companies of the 179th Infantry and the regimental headquarters, including clerks and kitchen personnel, managed to repulse the persistent German attackers several times, using bazooka, tank destroyer, and artillery fire against the enemy armor. Fighting continued in the town until dusk, when units of the 179th and 157th Infantry began returning to Meximieux from the north. With their withdrawal routes threatened, the German attackers finally broke off the action, but 45th Division troops were unable to clear the area completely until 0350 on the following morning.

As counted by the 179th Infantry, German casualties during the Meximieux affair totaled 85 men killed and 41 captured. In addition, 45th Division units destroyed 8 medium and 4 light tanks, 3 self-propelled guns, and 7 other vehicles. The 11th Panzer Division, with more enthusiasm than truth, reported to the Nineteenth Army that it had destroyed an entire American regiment. Actually, casualties of the 179th Infantry and supporting units numbered 3 men killed, 27 wounded, and 185 missing and probably captured. Matériel losses included 2 tank destroyers, 2 armored cars, 1 half-track, and 2 jeeps destroyed with about 20 other vehicles damaged. The most the German effort accomplished was to disrupt preparations by the 179th Infantry to participate in the 45th Division’s attack on 2 September. This, however, was von Wietersheim’s primary mission. Nevertheless, by the end of the day the threat to Lyon had grown even greater as both the 3rd and 36th Divisions as well as the French forces moving up west of the Rhone all arrived within striking distance (some five to ten miles) of Lyon.

Despite the growing Allied threat to Lyon, Wiese felt more confident by

the evening of the 1st. On the following day, 2 September, he expected that the bulk of the Nineteenth Army would be well north of the city screened in the south and east by the 11th Panzer Division, now reinforced by a regiment of the 338th Division. Yet Truscott still had hopes of catching Wiese’s forces off-guard. With Patch’s consent, he decided to allow the French the honor of formally occupying Lyon, while he had the 36th Division sidestep past the eastern edge of the city. To the northeast, he still expected the 45th Division to launch a major attack toward Bourg on 2 September, while the 117th Cavalry Squadron probed east and west of the town. With luck, he still might be able to penetrate the German flank defenses at some point and strike at their northward withdrawal columns.

This time the American units found the German security forces more solid and better organized. Between 2 and 3 September the 45th Division’s 157th and 180th regiments encountered strong German resistance south and east of Bourg-en-Bresse, and were unable to pierce the German flank defenses there. Meanwhile, seeking less difficult routes through the German lines, Truscott had the 117th Cavalry Squadron send out a series of reconnaissance patrols from the Meximieux area toward Macon, about thirty miles north of Lyon and fifteen miles west of Bourg. Although making little progress in the west, the squadron was able to slip one of its scout troops north through the German defensive lines and past Bourg without encountering any resistance. At 1730 that evening, B Troop entered the small town of Marboz located on a secondary road, ten miles north of Bourg. The cavalry force lost Marboz briefly to a small German counterattack, but reentered the town at dusk to stay the night.

Truscott immediately saw the tiny troop, with only armored cars and light trucks, as a lever that might unhinge the entire German flank security force. But speed was essential. Before the situation could be completely clarified, he directed the cavalry unit to push westward seven miles from Marboz and occupy Montrevel on Route N-75, the main highway northwest from Bourg. Since the new objective lay squarely on the 11th Panzer Division’s main supply route, the isolated cavalrymen expected trouble. One platoon of Troop B even managed to work its way into the eastern edge of Montrevel that night, but was abruptly thrown out by the German garrison and forced to retire to Marboz.

Meanwhile, the 117th Cavalry commander, Lt. Col. Charles J. Hodge, tried to concentrate the rest of his widely scattered forces in the Marboz area as quickly as possible. Troop A reached the town during the night along with a forward squadron command group, which immediately began planning for a second attempt at Montrevel early on the 3rd. Much, however, still depended on the arrival of more reinforcements, especially the squadron’s Troop C, Troop E (assault guns), and Company F (light tanks).4 But when these forces, which

had been scouting the area east of Bourg, failed to show, the squadron commander decided to attack anyway with only his two reconnaissance troops.

On 3 September Troop B started into Montrevel shortly after dawn followed quickly by Troop A. After scattering about 300 German service troops, the small force secured the town by 0930, but lacked the strength to occupy the entire area. Looking over the objective in daylight for the first time, the cavalrymen found that Montrevel stood on a low ridge surrounded by open farmland with few defensive possibilities; the two troops lacked the manpower even to occupy the entire town. But expecting a violent reaction from the German armored unit—the tiger on whose tail they now sat—the two troops tried to prepare a creditable defense of the eastern section of Montrevel as best they could.

Upon learning of the threat to his main route of supply and withdrawal, von Wietersheim immediately pulled his 11th Panzer Reconnaissance Battalion out of Bourg, reinforced it with a battery of self-propelled artillery, six medium tanks, and an engineer company, and dispatched the task force northwest to clear Montrevel. The German force reached Montrevel at 1100 and began a fight that lasted well into the afternoon. The Americans called for reinforcements, while holding on as best they could and mounting counterattacks to keep the Germans off balance. But the light armored vehicles of the cavalry were not intended for heavy combat, and the contest was uneven; by 1330 the American force was surrounded and in disarray. The self-propelled guns of Troop E, a mile or so to the west, could provide little support because of the confused nature of the fighting, and the arrival of Troop C and Company F was delayed by traffic problems as the units tried to backtrack through the 45th Division’s area of operation.

At 1430, with the Germans completely encircling the town, Company F attacked from the east and Troops A and B tried to break out. The results were disappointing. German artillery and tank fire easily destroyed or drove off the American light tanks, and only a few troopers within Montrevel managed to escape. By 1630 the American situation in the town had become hopeless.5 The number of wounded made other breakout attempts impracticable, and the ammunition of the cavalry force had just about run out. Shortly thereafter, all of the troopers who were left in the town surrendered. Half an hour later Troop C and the 2nd Battalion of the 179th Infantry began reaching the scene, but were too late to help. The remaining American forces in the area retired to Marboz for the night, leaving the German panzer division with its escape route intact.

When the cavalry squadron could take a count, it found that Troop A

had lost only 12 men, but only 8 soldiers from Troop B could be found. In addition, Troop B and one platoon of Troop A had lost all their vehicles—20 jeeps and 15 armored cars—while Company F had 2 light tanks destroyed and 3 damaged. The Germans captured 126 men, including 31 wounded, while 5 troopers had been killed during the fight. About 10 of those captured escaped during the next few days, and the Germans left behind 12 of the most seriously wounded when they evacuated Montrevel. German personnel losses are unknown, but the cavalry force accounted for at least 1 German tank, 2 armored cars, and 4 other vehicles.

Truscott later determined that the 117th Cavalry troopers at Montrevel had been careless and were caught napping by elements of the 11th Panzer Division withdrawing from Bourg. However, given German and American strength and dispositions in the area, it is hard to escape the conclusion that Truscott simply assigned missions to the 117th Cavalry Squadron that were beyond its capabilities.6 If Truscott expected more of the reconnaissance unit, then he ought to have reinforced it with tanks and tank destroyers. But Truscott and his staff may have underestimated the recuperative powers of the 11th Panzer Division and its strength in the Bourg area. As later noted by von Wietersheim, the 11th often went into action with about 50 to 60 percent of its available strength, in order to avoid heavy losses from Allied air and artillery if the tactical units were caught out in the open.7 This policy also made it easier to reconstitute damaged units fairly quickly, even after they had been in heavy action as at Montelimar, and may explain the division’s seemingly great staying power on the battlefield. Nevertheless, at both Montrevel and Meximieux as elsewhere, von Wietersheim’s actions were rarely decisive, even at the small unit level; and Truscott’s persistence in using every opportunity that presented itself to turn his opponent’s flank and strike at his rear was to slowly wear the 11th and its sister infantry divisions down to the bone.

While his forces were reoccupying Montrevel, von Wietersheim learned that the bulk of the Nineteenth Army had escaped north up the Saone valley past Macon and that only the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps rear guard remained in the area. His primary mission, protecting the retreating army’s flank, had thus been accomplished, and the panzer division commander now began planning his own escape. Faced with the certainty that the VI Corps would renew its attacks on 4 September, he ordered his armored elements to vacate their delaying positions in the Meximieux–Bourg–Montrevel area on the night of 3–4 September. But rather than heading north with the rest of Wiese’s forces, von Wietersheim turned the 11th Panzer Division to the northeast, planning to pull it back along the approaches to the Belfort Gap.

On the morning of 4 September,

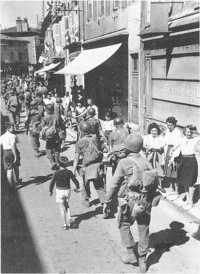

157th Infantry, 45th Division, passes through Bourg, September 1944

Truscott’s forces found that their foes had once again escaped. Units of the 45th Division occupied Bourg-en-Bresse, while those of the 36th Division moved into Macon. There was no opposition. In the west, French units of the 1st Infantry Division, after overcoming scattered German roadblocks and their own logistical problems, had entered Lyon earlier, on the 3rd, and also found the Germans long gone. However, bypassing the city on the west, CC Kientz of du Vigier’s 1st Armored Division, reinforced with the 2nd Algerian Spahis, achieved a signal success by trapping and destroying the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps’ rear guard twenty miles north of Lyon, taking nearly 2,000 prisoners. Meanwhile, on the other side of Patch’s spearhead, the French 3rd Algerian Division, out of Grenoble and now abreast of the leading VI Corps units, probed the Jura Alps toward the Swiss border, finding nothing but assorted FFI units. Behind the Algerians, O’Daniel’s 3rd Division finally rumbled up to the front lines, eager to get on with the drive north and with what many American GIs in the rear had begun to call “the champagne campaign.”

A Change in Plans

Patch’s original plans of 28 August had called for VI Corps to continue its drive directly north, moving up the Saone valley to Dijon in order to join Patton’s eastward-moving Third Army. Simultaneously, de Lattre’s forces on Truscott’s right were to begin a concentrated thrust to the northeast, aiming for the Belfort Gap and the Rhine.8 However, events had continued to move faster than many Allied planners predicted, and Truscott now believed the earlier plans were impractical. On 2 September, in view of the rapid German withdrawal to Dijon and the still-scattered deployment of the French divisions, he proposed several major revisions to these instructions. Pointing out that

de Lattre would need at least a week to concentrate his forces in the Bourg-en-Bresse area for the drive on Belfort, he suggested that his VI Corps undertake the mission instead. His three mobile infantry divisions were already massed east of Lyon and could begin to move northeast toward the Belfort Gap within a day or two. In front of them, he felt, were only scattered elements of the 11th Panzer Division, also moving northeast, but with very little armor left. More important, a rapid thrust to the northeast, taking the shortest route to the Vosges–Belfort Gap area, would give the Seventh Army yet another chance to trap the Nineteenth Army, catching the Germans between Dijon and the Vosges as they ultimately tried to withdraw eastward. The French, Truscott added, were already well north of Lyon and were therefore in a better position to pursue the bulk of the retreating German forces and then swing east through the Vosges passes to Strasbourg.

Patch formally agreed to Truscott’s proposals early on the morning of 3 September, but de Lattre was angry and objected strenuously to the changes. In part, his irritation stemmed from his belief that the two principal American commanders, Patch and Truscott, were making major decisions without consulting him or his staff. The fact that the French army would soon deploy more than twice as many divisions as the Americans on the battlefield lent weight to his position that the French divisions, as agreed upon, should be united on the Seventh Army’s right and, after joining with Eisenhower’s forces, become an independent army. If the French forces remained split, obviously this would be impossible.

De Lattre admitted that it would take several days to transfer the two French divisions, the 1st Armored and 1st Infantry, to the area east of Lyon, and probably a few more to bring up one or two additional infantry divisions from southern France. But he also pointed out that the 3rd Algerian Division, on VI Corps’ right, had already sent strong armored reconnaissance elements of its own fifty miles east of Bourg to scout out the routes to Belfort; moreover, the division planned to send an infantry regiment reinforced with a tank destroyer battalion toward the Belfort Gap on the following day. Starting even more forces east at this point was dangerous, he felt; and de Lattre questioned Truscott’s ability to support a corps-sized drive logistically.

In the end de Lattre compromised. On the afternoon of 3 September the French commander unilaterally announced the formation of two French corps-level commands—the I Corps under Lt. Gen. Emile Bethouart and the II Corps under General de Monsabert.9 De Monsabert’s II Corps was to control the French 1st Armored and 1st Infantry Divisions west of the Rhone and Saone, pushing north toward Dijon; Bethouart’s I Corps was to operate to the right of VI Corps with the 3rd Algerian and 9th

Colonial Divisions and later the 2nd Moroccan Division. In compliance with the revised Truscott-inspired plans, the French II Corps was to push north toward Dijon and then swing east toward Strasbourg; the French I Corps was to push east and northeast toward Belfort, presumably supporting Truscott’s drive northeast. The 2nd Moroccan Division would take over the northern sector of the Franco-Italian Alpine front and be replaced by the 4th Moroccan Mountain Division in early October (while the American 1st Airborne Task Force and the 1st Special Service Force continued to secure the southern sector). His forces thus remained split, but de Lattre had asserted himself as at least a provisional army-level commander of two French corps, easing the eventual establishment of a French army command, the First French Army, sometime in the near future.

Not wishing to make an issue of the matter, Patch accepted de Lattre’s amendments to his plans and issued supplemental orders on 4 September. Bethouart’s II Corps was to advance northeast toward the Belfort Gap on an axis that would take it south of Belfort city, and Truscott’s VI Corps was to aim for the northern shoulder of the gap. Truscott, although at first fearing that this solution would restrict his freedom of movement, agreed to the compromise and set to work hammering out the details of the operations with both his own and Bethouart’s new staff.

Creation of the Dijon Salient

On 3 September, as the Seventh Army leaders adjusted their plans, Hitler personally reminded Blaskowitz of Army Group G’s primary responsibilities: establishing a common front with Army Group B; defending the approaches to the Belfort Gap; and holding the salient around Dijon. This last was obviously the most difficult task, but the German political leader still had visions of launching an armored counterattack from an assembly area west of the Vosges. Blaskowitz, aware of the German Army’s limited capabilities in the west, was more concerned with holding on to the Dijon area until the remainder of his forces from the Atlantic coast could escape. However, he also knew that his pursuers from the south would not give him much time to pause and regroup. Taking all these factors into consideration, he completed plans to accomplish his diverse missions by 4 September.10

To protect his southern flank, Blaskowitz decided to establish delaying positions along and just south of the Doubs River, a small watercourse flowing generally west and southwest from the Montbeliard area through the small city of Besancon and joining the Saone River about thirty miles south of Dijon. The 11th Panzer Division, still operating under the Nineteenth Army’s direct control, was to defend the eastern section of the new line with a thirty-mile front from Mouchard to the Swiss border. From Mouchard the LXXXV Corps’ 338th

and 198th Infantry Divisions were to extend the line westward to the town of Dole on the Doubs River, thirty miles west of Besancon, and from Dole twenty miles farther west along the Doubs to the Saone. Backstopping the LXXXV Corps was a second line along the Doubs east of Dole, centering on Besancon and consisting of various ad hoc combat formations under Corps Dehner, which was a provisional headquarters under General Ernst Dehner, who had previously commanded the administrative and security organization Army Area Southern France. The main task of all these forces was to guard the approaches to Belfort.

Blaskowitz intended to hold the Dijon salient with three corps: the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps in the south; the LXIV Corps in the west, if it ever arrived intact from the Atlantic coast; and the LXVI Corps, which OB West had assigned to Army Group G on 27 August, in the north. At the time the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps had only the 716th Division and the remnants of the 189th Division; the forces that might be available to the other two corps were uncertain. Nevertheless, Blaskowitz thought it possible to hold for at least three or four days a loose cordon of strongpoints from Givry in the south, northwest to Autun, then north past Dijon to Chatillon-sur-Seine, and back east to Langres. The western section would be no more than an outpost or screening line through which retreating LXIV Corps elements could pass on their way to Dijon. The missing corps had incurred few losses on its way across central France, delayed only by FFI harassment, MAAF air attacks on march columns and bridges, and its own lack of transportation. By the time it arrived, Blaskowitz expected that he would be forced to fall back to the Saone and even farther east, depending on how much pressure the Allies brought to bear on his flanks.

At the time, elements of the LXIV Corps were already beginning to straggle into Dijon. The corps had begun its withdrawal with about 82,500 troops, of whom some 32,500 were members of ground combat units; the remainder belonged to various units from all branches and services assigned or attached to the Atlantic coast garrisons. Leading elements of the LXIV Corps’ vanguard, the weak 159th Infantry Division, reached the Saone River on 4 September; the 16th Infantry Division, which lacked three of its nine organic infantry battalions, entered the salient on the following day. The 360th Cossack Cavalry Regiment (horse cavalry) and the 950th Indian Regiment (infantry) arrived about the same time, as did the 602nd and 608th Mobile Battalions (light, motorized infantry). These organizations represented almost all of the “regular” combat strength for which the LXIV Corps had been able to find any transportation. Another 50,000 troops were still on the way, including rear elements, afoot, of the 16th and 159th Divisions; army, air force, and navy supply and administrative units; and a number of security, or police, battalions and regiments armed as auxiliary infantry. Some units and equipment were entrained but unable to move due to Allied air attacks on rail bridges and switching sites. The LXIV headquarters, which established a command post at Dijon on the 4th,

felt that the chances of bringing many of these troops into the salient were slim.11

Army Group G’s problems were all intensified by the increasingly rampant disorganization and depletion of units under its control, especially those now being positioned to defend the salient. All of these forces had suffered heavily from the almost inevitable straggling inherent in retrograde movements, and combat casualties had only increased the confusion. The result was a defensive order of battle so complex that its effectiveness was extremely doubtful. For example, north of Dijon, the LXVI Corps held the northern edge of the salient was an assortment of forces that Blaskowitz had been able to scrape together: the tankless Group Rauch of the 21st Panzer Division; the 608th Mobile Battalion and the bulk of the 16th Division just arriving from the Atlantic coast; Group Ottenbacher, a provisional brigade composed mainly of police and security units; and a host of smaller combat, quasi-combat, and service units of all types. The mixed force did little to allay Blaskowitz’s fear of an armored attack led by Patton toward Nancy on the boundary between Army Groups G and B.

In the west, screening the Givry–Chatillon outpost line, the LXIV Corps boasted Group Browdowski, consisting of the 615th Ost Battalion, the 4th Battalion of the 200th Security Brigade, a heavy battery of the 157th Antiaircraft Battalion, a provisional machine-gun platoon, and little more. Defending the southern edge of the salient, the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps had two major commands, the 189th Division and Group Taeglichsbeck. The remnant 189th, temporarily renamed Group von Schwerin, had two weak infantry battalions, a four-piece artillery “battalion,” and some miscellaneous attachments, altogether totaling less than 1,200 combat effectives. Group Taeglichsbeck included the 602nd Mobile Battalion, the 3rd Battalion of the 198th Security Regiment, an engineer company from the same unit, three batteries of the 990th Artillery Battalion, and an antitank company from the 16th Division.

To the southeast, Blaskowitz regarded the threat posed by Patch’s aggressive Seventh Army as equally worrisome, and the defenses in front of the Belfort Gap as little better than those outposting the salient. In answer to Wiese’s pleas for reinforcements there, he dispatched the 159th Division to Corps Dehner, which at the time had only a few police and security units, a couple of undependable Ost battalions, and a few pieces of light artillery. But to the south and east, the worn-out 11th Panzers and the 338th and 198th Infantry Divisions could not have been in much better shape. In fact the composition of the Nineteenth Army’s various gruppen changed from day to day as more elements of the LXIV Corps came into the Dijon salient and others arrived from the immediate army rear. Wiese, for example, tried to beef up the 189th Division in the south by adding to it the 726th Grenadiers of the 716th Division and the 2nd Battalion of the 5th Cossack Regiment. Finally Hitler himself gave Blaskowitz permission to reorganize his forces more or less as he saw

fit, bringing up to strength all of Army Group G’s regular formations by infusing them with “suitable” personnel from all branches of the armed services within the army group’s area of operation. Only certain specialists and technicians were excepted. The result was a slow but steady rise in the paper strength of the German divisions, but the effectiveness of the filled-in units remained to be seen. Without more training, Blaskowitz believed that units composed of such fillers had little offensive capability and could only be expected to defend in place for about two or three days. The German defenders would have to continue relying more on Allied supply problems than on their own military strength to keep the attackers at bay.

The Seventh Army Attacks

Given the weak German defenses, the Seventh Army’s advance northward continued almost at will between 4 and 8 September. In the west, the French II Corps’ 1st Armored Division slammed into the ragged line that the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps was trying to improvise between Givry and Chalons-sur-Saone (Map 11). It cleared both towns by the 5th and continued northward another ten to fifteen miles before halting on the 6th to await fuel supplies. During the night of 6–7 September responsibility for defending the sector passed from the IV Luftwaffe to the LXIV Corps. The change made no difference to the French, however, who continued pushing north on the 7th, nearing Beaune and rounding up hundreds of stragglers from the German 16th and 159th Infantry Divisions who were still trying to make their way to Dijon. In light of the rapid French advance, Wiese had already decided to begin abandoning the salient, and on that day ordered the LXIV Corps to pull its forces back to an area within a ten-mile radius of Dijon. Thus while CC Sudre occupied Baume unopposed on 8 September, the other units of the French II Corps were busy capturing the growing number of German forces unable to reach safety. These included six railroad trains—one of them armored—full of LXIV Corps troops, vehicles, guns, and supplies, and some 3,000 troops from Group Bauer, another ad hoc march group from the Atlantic.12 Meanwhile, Wiese had become increasingly concerned over the widening gap between the LXIV Corps and the rest of the Nineteenth Army, as Allied forces east of the Saone River began their drive on the Belfort Gap–Vosges area.

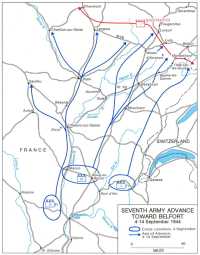

After regrouping and resupplying its forces on 3 September, VI Corps had begun its drive northeast on the 4th, heading in the general direction of Besancon on the Doubs River about fifty miles away. Initially O’Daniel’s 3rd Division led the attack with Dahlquist’s 36th Division on the left and Eagles’ 45th in the rear. On the corps’ right, or eastern, flank, the 3rd Algerian Division, the only French I Corps unit to have moved up to the

Map 11: Seventh Army advance toward Belfort, 4–14 September 1944

Lyon area, kept abreast of the American units. The rapid Allied advance gave Wiese no time to establish any kind of defensive line forward of the Doubs River, and the LXXXV Corps had to struggle to construct even a thin defensive screen there.

Approaching Besancon on the morning of the 5th, lead elements of the 3rd Division began probing German defenses and seeking suitable water crossings east and west of the town. Corps Dehner, responsible for defending the Besancon area, still had little more than a few security units under its control, but Wiese had reinforced it with a battalion-sized task force, including a company of tanks, from the 11th Panzer Division and was currently hurrying the 159th Infantry Division into the sector from Dijon.13 Wiese intended to make a stand here, if only to give the rest of his forces more time to move into their defensive sectors. However, on the 5th the supporting units of the 11th Panzer Division were about to depart the area, leaving Besancon defended by a few 88-mm. guns and crews from an antiaircraft unit, some engineers, a naval artillery unit, one security battalion, and elements of two reconnaissance battalions.

As the 3rd Division brought up its strung-out forces for a major effort against Besancon on 6 September, Truscott considered having the 3rd and 45th Divisions bypass the town on the east and allowing units of the 117th Cavalry and the 3rd Division to screen any German forces there. Later on the 5th, after 3rd Division troops had discovered an intact bridge west of the town, he discussed the possibility of outflanking Besancon from the opposite side. However, trouble late in the day farther east caused him to abandon the entire idea of bypassing the German defenses. At Baume-les-Dames, eighteen miles east of Besancon, the 3rd Algerian Division’s 4th Tunisian Tirailleurs had rushed over the Doubs using a damaged bridge, but were then severely mauled in a German counterattack by the 11th Panzer Division. With its other elements scattered south and southeast of Baume, the French requested immediate American assistance.

Meeting with Bethouart and the commander of the 3rd Algerian Division on the morning of the 6th, Truscott decided that it was too risky to simply bypass the German strongpoints and that they would have to be taken by force. To accomplish this he proposed that his 3rd Division seize Besancon, the 45th Division move against Baume, and the 3rd Algerian—its front somewhat narrowed—launch a concentrated thrust toward Montbeliard.

Meanwhile, during the night of 5–6 September, Wiese had again been busy reorganizing his defenses. First, he placed the LXXXV Corps headquarters, which had been controlling the sector west of Corps Dehner, in charge of the Belfort Gap defenses, leapfrogging it to the east and replacing it with the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps from the southern border of his now collapsing salient. Second, he moved all 11th Panzer Division elements out of

30th Infantry, 3rd Division, crosses Doubs River at Besancon, September 1944.

the Besancon–Baume region, shifting them well east of the winding Doubs and onto the most direct approaches to the Belfort Gap. At the same time, he attempted to fortify Corps Dehner’s weak defenses with the arriving 159th Division.

Along the Doubs River these shifts did the Germans little good. O’Daniel managed to move his 3rd Division troops across the Doubs and occupy the wooded hills around Besancon, thereby surrounding the town before the German defenders could react effectively. Despite a garrison that now totaled about 4,200, the strongpoint fell late on 8 September after about two days of desultory fighting, during which over half the defending troops were captured or made casualties. Subsequently Wiese had to withdraw what remained of the 159th Division for a complete overhaul.

West of Besancon, Dahlquist’s 36th Division reached the Doubs River line on the 6th, pushed aside the weak 338th Division elements defending the area, and, while advancing northeast of the Doubs on 8 September, bumped into the IV Luftwaffe Corps’ 198th Division as it was attempting to move across the rear of the German front to launch a counterattack against Besancon. A day-long battle between the two units around St. Vit, ten miles west of Besancon, saw the German forces routed, convincing Wiese that another general withdrawal was in order.

East of Besancon, Allied operations

Tanks of 45th Division advance in vicinity of Baume-les-Dames, September 1944.

proceeded more slowly. Lack of strength in the forward areas because of transportation and supply problems were the major culprits, and there was little that Patch or Truscott could do to solve these difficulties quickly. On 7 September the 45th Division’s 180th regiment crossed the Doubs southwest of Baume with no opposition, forcing 11th Panzer Division elements to evacuate the town on the evening of the 8th to avoid encirclement. To the southeast, the 3rd Algerian Division made some progress toward Montbeliard, but was firmly halted eleven miles short of the city by the bulk of the 11th Panzer Division, which had finally been infused with some new equipment. By then it was also evident that the French could not really pose a strong threat to Belfort until Bethouart’s I Corps could bring more of its divisions up to the front line. For now, a successful drive on Belfort would depend entirely on Truscott’s VI Corps.

To the Belfort Gap

By the evening of 8 September the Nineteenth Army had begun another major withdrawal along with the rest of Army Group G’s forces. The Seventh Army’s advances through St. Vit, Besancon, and Baume in the south made a continued stand along the Doubs River pointless; and, in the west, the French I Corps drive on Dijon was rapidly puncturing the German salient. Moreover, OKW had changed

the proposed counterattack assembly area from the vicinity of Dijon to that of Nancy, much farther north. Thus, with just about all of the units arriving from the Atlantic coast that could be expected, the so-called salient had outlived its usefulness. However, Blaskowitz could not order too deep a withdrawal. Patton’s Third Army was still moving east, and OB West had just transferred control of the German First Army—formerly on Army Group B’s left, or southern, wing—to Army Group G. The change made Blaskowitz responsible for launching the Hitler-proposed armored counterattack from the Nancy area against the Third Army. Although the army group commander could now afford to have the bulk of Wiese’s Nineteenth Army pull back to the Vosges, a certain portion of it plus the entire First Army would have to remain west of the mountains to defend Lorraine.14

To effect these changes, Blaskowitz directed the LXVI Corps to withdraw its forces east thirty-five miles from Chatillon-sur-Seine to Langres, fifty miles north of Dijon. From Langres the LXVI Corps’ new front was to stretch north some twenty miles to Chaumont, where it would then swing northeast to Nancy. He also instructed Wiese to pull the LXIV Corps back to the Saone, abandoning Dijon, and even farther east should French advances make it necessary; at the same time, Blaskowitz gave him permission to withdraw his forces from the Doubs River back to the northeast. Wiese, in turn, began pulling the diverse elements of the LXIV Corps, the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps, and Corps Dehner back to the east and northeast in an attempt to establish a new defensive line centering around Vesoul, a road and rail hub at the base of the Vosges some thirty miles northeast of the Doubs River line. Only in the far southeast, where the 11th Panzer Division and assorted battle detachments held the Allied forces at bay before the Belfort Gap, did the Nineteenth Army’s front appear relatively stable.

During 7 and 8 September the LXIV Corps redeployed the weak 716th and 189th Divisions to the Auxonne–St. Vit area, and prepared to move back even farther east on the 9th. In what had now become the Nineteenth Army’s center, Petersen’s IV Luftwaffe Field Corps began falling back ten miles to the Ognon River. There Wiese wanted Petersen to establish an intermediate defensive line with the 198th Division and Corps Dehner (now little more than a regimental-sized task force of the 159th Division) in the center; the 338th Division on its right, or western, wing; and a new formation, Group Degener, on its left, or eastern, wing.15 Composed of several odd police and security units, some provisional infantry companies organized from stragglers assembled at Belfort, and a couple of 88-mm. antiaircraft batteries, this patchwork organization was reinforced with a battalion combat team from the 11th Panzer Division and later by a new provisional security regiment. With Group Degener

anchoring the corps’ left wing at l’Isle-sur-les-Doubs, and the 338th Division holding the corps’ right at Ognon, about ten miles north of St. Vit, Wiese hoped that he could tie his center defenses into those of the LXIV Corps, retreating from the salient. However, before the new positions could be firmly established, Truscott’s VI Corps was again on the move.

On 9 September Truscott ordered his three divisions to wheel to the east, pivoting on the 45th Division in the l’Isle-sur-les-Doubs region. O’Daniel’s 3rd Division, in the center of the VI Corps line, had the mission of taking Vesoul, while Dahlquist’s 36th, on the corps’ left, was to swing wide to the north, keeping east of the Saone River, and end up in the Vosges foothills. Above the 36th Division, the 117th Cavalry was to screen the corps’ northern flank and tie into the French II Corps as it pushed east from Dijon.

Resuming its advance on the 10th, the 3rd Division encountered strong resistance along the approaches to Vesoul by Corps Dehner and the 198th Division, but, just to the west of the 3rd, Dahlquist’s 36th Division penetrated the defending 338th Division’s positions before the unit had time to deploy all its forces. Regarding Vesoul as critical, Truscott considered sending the bulk of the 36th to assist the 3rd. However, on the night of 10–11 September, Wiese decided to pull both the battered 338th Division and Corps Dehner out of the line, and again move the boundary between the LXIV Corps and the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps eastward, thereby leaving Vesoul defended only by the weak 198th Division. Apprised of these changes, Truscott held back the 36th Division, but finally approved its reinforcement of O’Daniel’s units when the 3rd Division proved unable to wrest the town from a German garrison that was larger than expected.16 Finally, about noon on the 12th, with units of both the 36th and 3rd Divisions beginning to surround Vesoul, the LXIV Corps ordered an immediate evacuation, and by 1500 that afternoon General O’Daniel pronounced the town secure.

Southeast of Vesoul, the 45th Division had less distance to travel, but the hilly terrain in its area favored the defense, and Group Degener, reinforced with armor, gave little ground without a fight. The German failure to hold at Vesoul finally forced Wiese to pull Group Degener back, but he quickly used it to form a new line defending the northern approaches to the Belfort Gap under the LXXXV Corps, and further reinforced the area with the 159th Division, somewhat reorganized and strengthened after its ordeal at Besancon. Below the 45th Division, I Corps’ 3rd Algerian Division still lacked the strength to make much of an impression on the 11th Panzer Division, now reinforced by Regiment Menke, a provisional infantry force operating in the more rugged terrain near the Swiss border.

During 13 and 14 September, Truscott’s three divisions completed their wheeling movement against the Belfort

The Champagne Campaign comes to a close.

Gap, moving up to the towns of Fougerolles, Luxeuil, Lure, and Villersexel. To the north, units of the French II Corps from Dijon began to arrive above the 36th Division, and in the south leading elements of the French I Corps occupied the sector from the 3rd Division’s southern flank to the Swiss border. In the German center the LXIV and IV Luftwaffe Field Corps appeared nearly broken; neither was capable of deploying more than a confusing medley of ill-trained and poorly armed provisional units in the path of the American advance. Truscott felt that the Nineteenth Army was close to collapse and, on the 14th, planned to launch what he expected would be a final push into the Belfort Gap. However, early on 14 September he received new orders from General Patch canceling all current operations. Both the Seventh Army and the VI Corps had now come under the authority of Eisenhower’s SHAEF headquarters, whose operational priorities and objectives did not envision possession of the Belfort Gap as especially significant. Up to now Patch, Truscott, and de Lattre had operated almost independently, with only loose supervision on the battlefield from General Wilson, the Allied commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean theater, through his deputy, General Devers. After 14 September, however, the plans of Patch and his principal commanders would have to conform to a larger operational framework dictated by

SHAEF. For all purposes the campaign of southern France was officially over and a new one begun, one in which the Mediterranean-based Allied army would obviously play a lesser role than before.

An Evaluation

By this time the Seventh Army had chalked up an impressive record. The success of ANVIL from an operational, tactical, and technical point of view was obvious. Despite the shortage of amphibious shipping and the constraints on planning and training, the execution of the operation had been almost flawless. From the German perspective, Blaskowitz and Wiese probably could not have prevented the Allied lodgment, but their response had been more disorganized than warranted, and the timely withdrawal orders saved them further embarrassment. Once ashore, Truscott had no intention of remaining within the beachhead—as had his ill-fated predecessor in the Anzio debacle barely six months earlier—and neither did Patch and de Lattre. Despite subsequent speculation over the possibilities of the battle at Montelimar, any extra fuel and vehicles that Patch might have been able to bring ashore under a different loading configuration would probably have gone to the French divisions driving on the vital ports, and not to Truscott’s VI Corps. An even greater reshuffling of the ANVIL assault force would probably have changed little as well. The two French armored divisions were inexperienced, and the three mobile American infantry divisions could not have moved very far north whatever additional support units were brought ashore until at least Toulon had been secured. Nor could Patch or Truscott have foreseen the complete disorganization of the German defenses in northern France prior to the start of ANVIL. The Allied commands were unable to confirm the breakout from Normandy until the failure of the Mortain counterattack on 10 August, and by the time that the American and Canadian forces in the north were beginning their attempt to close the Falaise Pocket on the 13th, all 500 or so ANVIL invasion ships were loaded and ready to sail. Moreover, a German collapse in the north did not guarantee a German withdrawal in the south, however logical that course of action may seem in retrospect.

Clearly Truscott’s efforts to trap the Nineteenth Army and speed up the advance of the VI Corps northward along the Besancon–Belfort axis to within striking distance of the Rhine River had not succeeded. Nor had his forces been able to split the front of the rapidly retreating Nineteenth Army or to isolate those units in the Dijon salient. The Germans had repeatedly been able to shift their forces more rapidly and defend key areas more tenaciously than either Truscott or Patch had believed possible. Nevertheless, it was equally clear that the French would not have been able to concentrate their forces east of Lyon quickly enough to have undertaken a similar drive, especially since any delays would have made the advance toward the Belfort area even more difficult. As at Montelimar and Lyon, Truscott and Patch had once again shown a willingness to take a calculated risk, taking full advantage of the

campaign’s momentum and ready to capitalize on any errors their opponents might make. Had they attacked toward Belfort on a narrower front, they might have had more success, but such a maneuver would also have exposed the VI Corps’ left, or northern, flank to a German counterattack and in addition would have allowed Wiese to concentrate more of his own forces along the immediate and more defensible approaches to the gap. In any case, a rapid seizure of the gap itself would not have necessarily opened up the Alsatian interior and the Rhine valley, since the Seventh Army’s logistical problems would have multiplied even further.

Logistical problems, mainly fuel and transportation shortages, played a major role in slowing down the Allied advance in both northern and southern France. Increasing the allocations of fuel and trucks to the initial assault force might have helped somewhat at Montelimar, but could not have substituted for the seizure and rehabilitation of the larger ports, especially Marseille. Their early conquest by de Lattre’s aggressive French units gave the Seventh Army an important supply edge over the Normandy-based Allied armies, although this advantage would dissipate as the distance between the Mediterranean harbors and the battlefield grew ever longer. By the time the Seventh Army had reached the Moselle, American engineer units had restored the ports, but they were just beginning the frantic effort to repair and expand the French north-south railway system. Other critical factors slowing the progress of the Seventh Army during early September included the lack of close air support, worsening weather, and general troop fatigue. The first problem was a logistical and engineering one solved by the gradual displacement of airfields north, but answers to the other two were more elusive.17

Troop fatigue, affecting both officers and men, was difficult to quantify. On 9 September General Butler, who had returned to his post as assistant VI Corps commander after Montelimar, noted the declining aggressiveness of the front-line troops and a tendency to rely more often on artillery and mortar fire in small combat engagements.18 This reluctance to close with the enemy—to rely more on firepower than on maneuver on the battlefield—was, he felt, a sign that the combat troops and especially their leaders were beginning to tire, psychologically if not physically. By that time the VI Corps had advanced some 300 miles from its ANVIL assault beaches in just twenty-six days (Eisenhower’s SHAEF forces had taken ninety-six days to cover a similar distance) and the actual travel mileage was obviously much greater. The 3rd Division’s command post, for example, had moved along some 400 miles of French roads on its way north from ALPHA RED to Besancon, and many other units, such as the 117th Cavalry Squadron, had covered even more ground. According to one participant, the VI Corps headquarters units became so adept at moving that “those fellows could knock it down

and, just like Ringling Brothers [Circus], set it up again” at a moment’s notice.19 In the rear areas, the American and French advance northward had indeed been somewhat of a circus. Most Seventh Army soldiers had come on foot because of the critical shortage of trucks, which was aggravated by the continuing need to divert almost all vehicles to support the lengthening supply lines. In the French formations, de Lattre’s officers drafted civilian autos, river boats, horse carts, and any type of functioning captured vehicles that could further the movement of troops and supplies north. Finally, although the SHAEF troops had certainly seen more fighting, they were also a larger force, able to distribute the rigors of the campaign over many more divisions; while in the case of the Seventh Army, most of the advance had been accomplished by a smaller number of units operating without respite. Thus, after pushing an average of ten miles per day, normally on foot, through German-defended territory, the forward infantry units of the Seventh Army had understandably begun to wear out as they approached the Belfort Gap and the Vosges Mountains.

Casualties also began to influence VI Corps’ effectiveness. As of the evening of 9 September the corps had suffered over 4,500 battle casualties (including 2,050 killed, captured, or missing) and some 5,300 nonbattle casualties. Of the nearly 9,900 losses, about 2,900 men had been returned to duty; although the corps received around 1,800 replacements, it was short about 5,200, mostly infantrymen. French casualties were slightly higher, although spread out over a greater number of units.20 With most of the Allied armies in both France and Italy in the same situation, there was general competition for infantry fillers that, for the time being, could not be fully satisfied except by cannibalizing new units or turning support units into rifle formations—solutions that had only adverse effects in the long run.

Weather was another important consideration. Inclement weather almost always penalizes the attacker by reducing the mobility of military forces. By 9 September the French autumn rains had begun in earnest; streams were rising, and cross-country movement was becoming progressively more difficult. Trails and dry-weather roads turned into quagmires, forcing most vehicles to rely on paved routes, many of which were deteriorating rapidly under heavy military traffic. In addition, the overcast weather reduced the amount of air support available, greatly limiting its ability to interdict German movements during September. Terrain was also a factor, for by 9 September both

the VI Corps and the French I Corps were well into hilly, often wooded ground that gave many advantages to the defense. The combination of all these factors—transportation, supply, fatigue, weather, and terrain—thus began to blunt the edge of the Seventh Army’s combat power, especially in the final drive toward the Belfort Gap.

An accurate appraisal of the German actions is difficult. Finally forced to make a stand between Dijon and Belfort, Wiese and Blaskowitz had managed to hold the area for a few critical days before retiring to the Vosges and the gap. If the conduct of the defense had lacked a certain grace and finesse, at least it was handled well enough to avoid a catastrophe. Despite the makeshift character of the successive defensive lines, Wiese was becoming more skillful at presenting a continuous front to his pursuers, thus guarding his own flanks and, by persevering, keeping the Seventh Army well away from the German border. The losses of both Army Group G and the Nineteenth Army, however, had been staggering, and Truscott’s estimate that Wiese’s forces were close to a total collapse was correct. Between 3 and 14 September the Seventh Army had captured another 12,250 Germans, about 6,500 of them taken by VI Corps troops. Adding the nearly 20,000 men of Group Elster, which had been cut off west of Dijon, the Allies had now captured roughly 65,250 men that Army Group G had tried to extricate from southern and western France. To this figure must be added the 31,000 German prisoners taken at Toulon and Marseille by the French, the 25,000 left hopelessly isolated in Atlantic coast garrisons, and some 10,000 prisoners taken by the U.S. Third Army from units that Army Group G had dispatched north of Dijon to protect its weak right flank. The grand total of prisoners alone (plus the troops isolated on the west coast) came to 131,250, over 40 percent of Army Group G’s original strength on 15 August.

From available sources it is impossible to ascertain with any degree of accuracy the losses in killed and wounded among the units employed by Army Group G through 14 September. Estimates run as high as 7,000 killed and three times that number wounded. If so, Army Group G, as of the evening of the 14th, had incurred at least 143,250 casualties, over half of its strength a month earlier.21

The German units that survived both the arduous trek out of southern and southwestern France and the fighting against Seventh Army’s French and American forces certainly did not resemble cohesive combat organizations by 14 September. All units were grossly understrength and underequipped; not one of the Nineteenth Army’s divisions deserved the title. The German troops were tired—even more than the VI Corps infantrymen—and their logistical system was a shambles. The 338th Division had fewer than 3,200 men left on its

rolls, and of these only 1,100 were combat effectives. The 159th Division had less than 3,500 effectives left; the 716th Division probably had 3,250; the 198th not more than 2,400; and the 189th less than 1,000. And many of these “effectives” were not experienced infantrymen at all, but a mixture of police, administrative, and logistical support, navy, and other fillers thrown into depleted units as cannon fodder. The 11th Panzer Division, which had reached Lyon almost completely intact, had suffered heavy losses between 3 and 14 September, ending up with only 6,500 men, of whom only 2,500 were in line combat battalions. In addition, the panzer division had lost all but a dozen of its tanks and was down to two operating self-propelled guns. Furthermore, the Nineteenth Army’s many provisional kampfgruppen had lost up to 30 percent of their strength during the same period, but no one could tell exactly.

The good news for Army Group G’s soldiers was the increasingly favorable defensive terrain into which their units were now withdrawing as well as the reduced frontage they would have to defend. Already, German support units were constructing hasty defenses in the Vosges Mountains and repairing and reorienting old fixed French fortifications in the Montbeliard–Belfort area. Reserves were building up in and around Belfort, while a steady flow of better trained replacements and newer equipment had begun to arrive from Germany for the units facing VI Corps. Between 14 and 19 September, for example, the 11th Panzer Division’s operational tank strength more than doubled, even though the unit lost more tanks during that period. Army Group G’s supply lines had also grown much shorter, making the almost traditional logistical problems of the German Army less pressing. The approaching winter weather promised to decrease even more the effectiveness of Allied air attacks and to hide German military movements and dispositions from Allied observation. On the other hand, the German Army had just about run out of space to trade for its survival in the west. If the Allied armies could engineer a major breakthrough in the weakly held German lines before the defenders had a chance to recover, the collapse that Truscott had hoped for might well follow. Nevertheless, for both sides one major campaign had ended and a new one was about to begin.