Part 3: Ordeal in the Vosges

Blank page

Chapter 12: Strategy and Operations

While Truscott’s divisions wheeled toward the Belfort Gap, de Monsabert’s French II Corps, on the Seventh Army’s western flank, had continued north toward Dijon, periodically delayed by fuel shortages. The French northern drive from Lyon had been opposed ineffectively by a medley of odd-sized German forces—Groups Browdowski, Taeglichsbeck, and Ottenbacher and what was left of Group Bauer and the 716th Infantry Division, all under the occasional supervision of the LXIV Corps in the south and the LXVI Corps in the north. On 11 September the French 1st Armored Division rolled into Dijon unopposed and, scarcely pausing to join the celebration of the city’s populace, headed north for Langres, about forty miles farther. Approximately fifteen miles to the west, the French 1st Infantry Division matched its pace, moving north and northeast led by the 13th Foreign Legion Demibrigade, the 2nd Dragoons (tank destroyers), and the 1st Naval Fusiliers. Intermittently throughout the day both of de Monsabert’s divisions had telephone contact over local lines with the French 2nd Armored Division, part of Patton’s U.S. Third Army that had already reached Chatillon-sur-Seine. Finally, later in the afternoon of the 11th, the 2nd Dragoons met a small patrol from the U.S. 6th Armored Division at Saulieu, twenty-five miles north of Autun, which formally marked the physical union of the OVERLORD and ANVIL armies in northern France. As the II Corps moved east, the French and American forces cemented the juncture between Dijon and Chatillon, giving the Allied armies in France a common front from the English Channel in the north to the Mediterranean in the south. The time had now come to implement existing plans that would unify the Allied command structure in France and place the Allied forces from southern France under Eisenhower’s SHAEF command. Henceforth Seventh Army’s operations would conform to strategic and operational concepts determined by SHAEF for the prosecution of the war against Germany. The “champagne campaign” was officially over.

SHAEF’s Operational Concepts

Patch’s approval on 3 September of Truscott’s plan for a concerted VI Corps drive on the Belfort Gap, with the French divisions of Army B split between the attacking American forces, was a purely opportunistic measure

that only temporarily altered the Seventh Army’s general campaign plans. Whatever the results of Truscott’s drive, Patch fully intended to implement the deployment concept he had promulgated late in August—concentrating de Lattre’s French forces on the Seventh Army’s right and Truscott’s VI Corps on the left. The VI Corps was then to advance northeast across the Vosges Mountains to Strasbourg and the Rhine, while the French divisions would push through the Belfort Gap to the Alsatian plains.1 General Eisenhower himself had outlined this deployment plan as the Seventh Army moved toward Lyon, and it had been approved by General Wilson as well as by General Devers, the commander-designate of the 6th Army Group. Shortly thereafter Eisenhower and Devers confirmed the concept during coordinating conferences at SHAEF headquarters between 4 and 6 September.2

Eisenhower had always held that command of the ANVIL forces should be transferred to SHAEF soon after the Seventh Army started moving in strength north of Lyon, an advance VI Corps had initiated on 3 September. The date of transfer received consideration during the 4–6 September conferences, and on the 9th, after additional long-distance consultation, AFHQ and SHAEF finally agreed that Eisenhower would assume operational control of the forces in southern France on 15 September. At that time Headquarters, 6th Army Group, would become operational in southern France, and simultaneously control of the XII Tactical Air Command would pass from the Twelfth to the Ninth Air Force.

Eisenhower, Wilson, and Devers agreed that the transfer of operational responsibility need not wait until SHAEF assumed logistical and administrative control except in the field of civil affairs. At the time, SHAEF was having logistical problems of considerable magnitude and was in no position to assume the added burden of controlling logistical operations in southern France. Thus the Allied commanders decided that the 6th Army Group would administer its own semi-independent logistical system through Mediterranean channels, using supplies arriving directly from the United States as well as excess stocks not needed in MTO reserves.

Eisenhower and Devers also determined that the activation of the 6th Army Group would be accompanied by the transformation of French Army B into the First French Army, an organization that would be operationally, logistically, and administratively independent of Patch’s Seventh Army. Until more American forces became available, the change would leave Patch with little more than Truscott’s VI Corps to control. Although Devers decided that Patch would continue to direct First French Army operations until the redeployment was completed, this somewhat anomalous situation lasted only until 19 September.

Devers was understandably disturbed

over leaving the Seventh Army with just a single corps. Such an understrength army command could play only a minor role in future operations against Germany. Devers, in fact, had been concerned by the lack of American strength since the beginning of ANVIL. Once the landings in southern France were successful, he would have preferred transferring the entire U.S. Fifth Army as well as the rest of the Twelfth Air Force from the Italian to the southern France front. Realizing that such a large redeployment was both politically and operationally impossible, Devers had sought to have at least the Fifth Army’s IV Corps shipped from Italy to southern France. But early in September Wilson had blocked the move, convincing the CCS and the JCS that the transferral would ruin any chance for the success of operations then under way in Italy. Devers next requested that one of SHAEF’s American corps be transferred to the Seventh Army, a proposal that Wilson also made. At the time, Gen. Sir Bernard Montgomery’s 21st Army Group had five corps and Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley’s 12th Army Group had seven. But Eisenhower stated that he could not spare a corps at that time and believed that the three fresh American divisions scheduled to arrive through southern French ports during October and November would greatly strengthen the Seventh Army, even if no additional corps headquarters were available. In the end, the 6th Army Group received no reinforcements, and the Seventh Army was left with only a single corps headquarters and three infantry divisions in its order of battle.

SHAEF’s Operational Strategy

General Devers, now in the process of assuming direct control of both the U.S. Seventh Army and the First French Army, had never commanded a unit on the battlefield. However, along with Generals Eisenhower, Lesley J. McNair, and Brehon B. Somervell, he had been one of the principal officers used by General Marshall to train, equip, and direct the efforts of the American Army in the European theater.3 As commanding general of ETOUSA in 1943 and of NATOUSA in 1944, Devers had vigorously represented the views of Marshall and the JCS and knew the importance that they attached to a direct thrust at Germany through northern France. This background had given the new army group commander a good feel for the political and personal dimensions of the Allied high-level command, an area where Patch and de Lattre had little experience. Now, as one of the major Allied field commanders, the energetic and sometimes outspoken Devers would have the opportunity to put his ideas and knowledge into action.

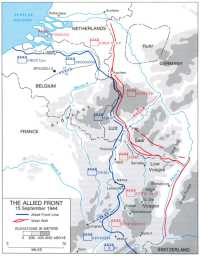

Like Patch, Devers was well aware that realigning the Seventh and First French Armies was part of Eisenhower’s larger plan for the use of Allied military power in northeastern France. American forces, Eisenhower had long since decided, would occupy the center of a broad Allied advance in northern France toward the German border (Map 12). For this

reason he wanted Bradley’s 12th Army Group in the middle of the Allied line, between Montgomery’s 21st Army Group in the north and Devers’ 6th Army Group in the south. In mid-September Bradley’s center command had three armies, but only two were on line, the First and the Third, with the Ninth Army still clearing the Brittany peninsula in the west. Montgomery’s 21st Army Group, consisting of the First Canadian and Second British Armies, constituted the left, or northern, wing of the Allied line, and Devers’ 6th Army Group was its right, or southern, wing. The eventual arrival of the Ninth Army in Bradley’s center and the redeployment of Patch’s Seventh Army to the left of the 6th Army Group would complete the concentration of American combat power in the center of the Allied line.

Eisenhower would have preferred transferring the entire Seventh Army to Bradley’s central army group, but feared that the First French Army might not be ready to undertake total responsibility for the Allied right wing. Moreover, without Patch’s Seventh Army, the 6th Army Group’s American contingent would have consisted of little more than some artillery and service units directly supporting the First French Army; various logistical and administrative units along its line of communications to the Mediterranean; and the 1st Airborne Task Force, still outposting the Franco-Italian border area. Under such circumstances de Gaulle would certainly have pressed for French command of the army group or at least the elimination of the army group and an expanded role for the First French Army. The result would have forced Eisenhower to deal with both French and British national interests personally, further multiplying his command problems. Eisenhower thus believed it necessary to preserve a significant American complexion in the 6th Army Group, and so he left the existing command arrangements in place.4

Having accepted the need for the 6th Army Group headquarters on his southern wing, Eisenhower was still uncertain regarding the role he would assign to it. The northern boundary of Devers’ command, as established by SHAEF, stretched northeast from Langres past Epinal, about forty miles north of Vesoul, to Strasbourg on the Rhine. Although its southern flank technically rested on the Swiss border, the army group also inherited the Seventh Army’s responsibility for outposting the Franco-Italian border in the far south. Initially Eisenhower assigned the 6th Army Group three general missions within its main area of operations: destroy the opposing German forces; secure crossings over the Rhine River; and breach the Siegfried Line—the generic term SHAEF applied to the German-built West Wall fortifications just inside the German border. How these objectives fit into SHAEF’s larger operational plans is difficult to discern.

Following the breakout from the Normandy beachhead, the opening eastern movement of Eisenhower’s OVERLORD forces had been characterized by rapid pursuit, and the ensuing period by even more narrow axes of

Map 12: The Allied Front, 15 September 1944.

advance because of SHAEF’s inability to support a more general offensive logistically. Eisenhower had therefore never been able to implement his so-called broad front strategy. By mid-September logistical concerns had in fact made the seizure and rapid rehabilitation of a major port, Antwerp, an overriding military objective. Although Antwerp had fallen to Montgomery’s 21st Army Group on 4 September, the Germans still controlled the approaches to the port from the Schelde Estuary; the estuary would have to be cleared before the port could be opened. A complementary development was the desire to concentrate the Allied ground advance against specific objectives that would seriously impair Germany’s ability to wage war. The closest and most obvious target was the Ruhr industrial area of northwestern Germany, a region whose capture would also provide a wide invasion route into the heart of Germany. All these factors dictated that the main Allied effort should be focused along a narrow front in the zone of the 21st Army Group, an idea that General Montgomery as well as many high-ranking British political and military leaders vociferously advocated.

Faced in September with the continued logistical impossibility of supporting a broad offensive, Eisenhower adopted Montgomery’s operational concept as the most suitable course of action. In doing so, however, he abandoned the flexibility of the broad front strategy and made terrain the main Allied objective rather than enemy forces. The failure of the Allied armies to close the Falaise Pocket earlier had already demonstrated a certain operational rigidity as well as a tendency to measure success totally in terms of terrain, a problem that had also beset the Italian campaign. Moreover, SHAEF’s inflexibility in this area was further aggravated by the difficulties Eisenhower continued to have in controlling the independently minded Montgomery. Such, perhaps, was the inevitable nature of coalition warfare, and Eisenhower’s ability to manage his sometimes quarrelsome subordinates, as well as to fend off their political chiefs and preserve the alliance, may have been the most accurate measure of his success in the art of generalship.

To gain his objectives in the north, Eisenhower intended to employ Montgomery’s 21st Army Group and most of the 12th Army Group’s First Army. He also planned to use the bulk of his available airborne forces—now in reserve and organized into the First Allied Airborne Army—in the 21st Army Group’s Operation MARKET-GARDEN, an attempt to envelop the Ruhr basin from the north. If Montgomery’s daring offensive succeeded, Eisenhower hoped to drive across the north German plains and finish the war by the end of the year.

With close to half its strength supporting the northern effort, the rest of Bradley’s 12th Army Group was relegated to a secondary role. Patton’s Third Army, Eisenhower told Bradley, was to confine itself to limited advances, pushing east to secure bridgeheads over the Moselle River in the Metz–Nancy region, thereby threatening the Saar basin, an industrial region second only to the Ruhr. This action would also fix German

units in place that might otherwise be deployed north. Once the Third Army had its forces firmly across the Moselle, the 12th Army Group was to concentrate its remaining resources to help the First Army seize crossings over the Rhine immediately south of the Ruhr. Then the Third Army could begin moving against the Saar. Although the resulting SHAEF campaign plan appeared somewhat rigid, it was perhaps complex enough to confuse the Germans and still allow SHAEF some flexibility if a change in the main effort became necessary.

Despite these arrangements, disagreements over operational strategy still plagued the Allied high command. Eisenhower felt that his plans followed the principles of the broad front strategy as much as was practicable; Montgomery believed they adhered too closely to the concept, fearing that the Third Army’s secondary thrust against the Saar might undermine his single concentrated thrust in the north. But in this matter, Eisenhower strongly disagreed, believing that ceasing all offensive operations in the central and southern Allied sectors would allow the Germans to transfer more forces north or to initiate a major counterattack elsewhere. The projected efforts of Bradley in the center also enabled Eisenhower to retain at least the semblance of a broad front strategy. In this, however, he was mistaken. His new offensives were now closely tied to fixed terrain objectives, while the aim of a true broad front offensive was the destruction of enemy forces, either by attrition or by maneuver once weaknesses in the enemy defenses became apparent.

Having discarded a flexible operational strategy, SHAEF had no real role to assign the newly created 6th Army Group. From a theater point of view, a major effort in the south seemed pointless. Devers’ forces faced a daunting array of obstacles, starting with the Vosges Mountains, followed by the Rhine River and the West Wall, and finally the Black Forest, another thirty miles of almost impenetrable terrain, all highly favorable to the defense. And even if his Franco-American forces were somehow able to push through these barriers, which was extremely unlikely, the seizure of Nuremburg or Munich—just about the only prizes on the other side—did not seem especially worthwhile objectives. However, there were alternatives that neither Eisenhower nor his SHAEF planners ever considered: for example, sending a reinforced 6th Army Group north through the Rhenish plains in a vast enveloping maneuver against the flank or rear of the German forces defending the Saar and Ruhr regions; or sending it north as far as Frankfurt and then northeast, following the famous Napoleonic route toward Berlin through the critical Fulda corridor. Instead, both Eisenhower and his major subordinates remained preoccupied with their existing plans which called for a drive into Germany by two army groups, one operating north of the Ardennes forest, and the other to the south. Developing the port of Antwerp and designating the Ruhr and Saar as strategic objectives had been given some thought earlier during OVERLORD planning and now meshed easily with the operational concepts already in place. But SHAEF planners had never taken into consideration

a major force coming up from the south, and SHAEF concepts had not changed after the CCS approved ANVIL, or even after the Seventh Army had landed and sped northward faster than anyone expected.

Finding no role for it in the northern offensive, Eisenhower appeared to give Devers’ 6th Army Group a somewhat independent status. With only three American divisions and a French army composed primarily of colonial troops, Devers’ command must have seemed insignificant despite its imposing army group designation. Nevertheless, although small, the group had its own independent line of communications and its own logistical base; the French forces could, in fact, recruit and train replacements immediately behind the battlefield. For the present then, the force appeared capable of sustaining itself without making any demands on SHAEF’s overtaxed logistical system in northern France. This situation, in turn, enabled the group to conduct its own, more or less separate offensives that could tie down German divisions, without detracting from the more important operations in the center and north of the Allied line. But Eisenhower still expected little from the 6th Army Group, believing that even the most successful advances in the south had little strategic potential.5

What independence thereby fell to Devers’ command was the product of circumstance—the simple geographical distance between SHAEF’s northern and southern wings and the perception that the southern sector of the Allied line was a dead end. But officially at least, 6th Army Group operations were part of the larger Allied concept. On 15 September, for example, Eisenhower promised Bradley that the Seventh Army, even though it remained part of the 6th Army Group, would always be maneuvered to support the 12th Army Group.6 To the CCS and Montgomery, Eisenhower maintained that 6th Army Group operations would be designed primarily to support the more important drives farther north and to protect the 12th Army Group’s southern flank. Possibly SHAEF approved 6th Army Group’s offensives toward Strasbourg and the Rhine only because they did not appear to interfere in any way with the northern effort; furthermore, Eisenhower must have hoped that the southern army group’s separate line of communications might enable him to increase the 12th Army Group’s logistical support at some future date once the capacity of the Mediterranean supply system had been sufficiently expanded. But as long as Devers remained logistically independent, Eisenhower was apparently willing to give him a certain freedom of action.7

Lt. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott, General Patch, and General Devers, October 1944.

Patch and Truscott

Within the 6th Army Group, the reactions of the senior commanders to SHAEF’s plans were mixed.8 General Devers was undoubtedly disappointed. Hoping ultimately for a greater role for his command, he continued to press SHAEF for an additional American corps to strengthen Patch’s Seventh Army. Patch was also understandably unenthusiastic upon receiving word that his forces would be relegated to a minor supporting role, and Truscott was obviously displeased that his current offensive would have to be halted and his front moved north opposite the Vosges Mountains. In contrast, General de Lattre, unhappy with the current division of the First French Army between Patch’s Seventh, was generally satisfied with the concentration of the French on the Allied right wing.9 For both political and military reasons that decision, fully supported by Devers and Patch, was to prove sound.

Based on Eisenhower’s guidance, Devers issued new orders calling for the French II Corps to move from the sector west of the Saone River, on VI Corps’ northern flank, to the area south of the VI Corps, taking over the territory currently occupied by the 45th Infantry Division. The 36th Division would simultaneously stretch to the north, taking over the area vacated by the II Corps. These changes would put all of de Lattre’s forces opposite the Belfort Gap, with the II Corps in the north and the I Corps in the south and Patch’s three-division “army” opposite the rugged Vosges Mountains. Within its zone, the First French Army was to drive through the Belfort Gap and then head north to clear the Alsatian plains; to the north, the VI Corps was to march northeast across the Vosges, with its axis of advance between Vesoul and St. Die, and aim at Strasbourg, some 120 miles from Vesoul.

After fully digesting the Seventh Army’s new orders, Truscott wrote a strongly worded letter to Patch

making strenuous objections to the change in plans.10 Believing that the Nineteenth Army was close to total collapse and that the VI Corps was on the verge of breaking through the northern shoulder of the Belfort Gap to the Rhine, he reminded Patch that the Army commander himself had just approved the continuation of his offensive against Belfort and, he felt, had agreed that the Belfort Gap was one of the primary gateways to the German heartland. By the time the Allies regrouped their forces, the Germans would have slammed the gate shut. Truscott had had his fill of winter fighting in the mountains of Italy, and neither he nor any of his troops desired to repeat the experience in the Vosges. The terrain and weather, he pointed out, would allow the Germans to control the pace of any Allied offensive there and, in his opinion, would waste three fine American divisions with little benefit either to SHAEF’s efforts in the north or to the First French Army’s drive against Belfort. Rather than tying German divisions down to defend the area, a mountain offensive would allow them to deploy more resources elsewhere. In Truscott’s opinion the greatest assistance that the Seventh Army could provide SHAEF was to send the VI Corps directly through the Belfort Gap to the Rhine. If, he concluded, the VI Corps could not be employed properly in France, then it should be returned to Italy under AFHQ control to mount an amphibious operation against Genoa. Such an operation, Truscott was convinced, would at least break the stalemate in Italy, whereas an attack through the High Vosges Mountains would accomplish nothing.

Patch tried to soothe Truscott as best he could, relaying the news that the U.S. Senate had recently confirmed his promotion to lieutenant general. Nevertheless, he could offer little hope that SHAEF’s operational concepts could be altered or that the VI Corps would be allowed to continue its offensive against the Belfort Gap. In this area Patch could do little more than affirm his confidence in Truscott and hold out hope that the Germans might also have discounted an Allied attack over the Vosges and thus maintained only a thin defensive shell there.

Tactical Transition

On 15 and 16 September Truscott’s forces resumed their drive east, meeting stiff German resistance on the 15th but only scattered opposition on the following day as the 3rd Division occupied Lure, the 36th Division secured Luxeuil, and the 117th Cavalry Squadron reached St. Loup. Late on the 16th, however, Truscott ordered a halt to the advance and, in compliance with Patch’s directive of the 14th, issued instructions reorienting the corps for an immediate drive northeast across the Moselle River and into the Vosges Mountains toward St. Die and Strasbourg.11 He hoped that the French II Corps, redeploying from the north, could relieve the 45th Division on his southern wing by the 17th. Ever the opportunist,

Truscott wanted to begin as quickly as possible before the Germans had time to recover. But Devers decided that the northern French corps would be unable to complete its redeployment until 21 September, forcing Patch to direct Truscott to hold his units in place until the transfer of area responsibilities could be completed. Truscott, temporarily frustrated, used the next several days to have his units bring up supplies and secure forward assembly areas for the Moselle crossing. During this period the 45th Division also began deploying from the VI Corps’ right to its left, or northern, wing, replacing the departing French. By 18 September, Truscott thus had his three divisions oriented on the Moselle and the Vosges, ready to advance northeast on command.

To Truscott’s surprise, preliminary probes toward the Moselle between 16 and 18 September found German opposition again stiffening in the southern part of his sector close to the Belfort Gap, but almost negligible resistance in the north, especially in the Remiremont–Epinal area along the Moselle. Again the irrepressible Truscott sought Patch’s permission for an immediate attack to exploit the situation. This time the reaction was more positive. Although SHAEF had not yet officially approved the plan to push the Seventh Army across the Vosges, Devers and Patch agreed with Truscott that further delays would only allow the Germans to become more entrenched along the Moselle and the western slopes of the Vosges. So, with the French II Corps’ redeployment nearly complete, Patch, with Devers’ blessing, gave Truscott the green light to start this new offensive the following morning. Thus, at 1630 on the 20th, the three VI Corps infantry divisions began their advance toward the High Vosges.12

German Plans and Deployment

Once the Allied armies had broken out of their OVERLORD beachheads, the basic German operational objective in northern France was to hold along a defensive line as far west of the Franco-German border as possible. Ostensibly, this defensive line was to originate at the Schelde Estuary in the Netherlands and cross into Germany near the city of Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle). From the vicinity of Aachen south to the confluence of the Sarre and Moselle rivers near Trier, the line corresponded to the neglected prewar West Wall, sometimes known as the Siegfried Line. The Trier area also marked the boundary between Army Groups B and G as of 8 September.13

From Trier southwest thirty-five miles to Thionville, the line followed the Moselle River and was therefore designated the Moselle position. At Thionville the main defensive line was to swing sharply back southeast for about fifty miles to Sarralbe, corresponding

for the most part with the French prewar Maginot Line. From Sarralbe the line was to continue generally south and southwest across the Vosges, through the approaches to the Belfort Gap, and on to the Swiss border. In the area north of Devers’ 6th Army Group, the German high command also wanted to establish a western salient at Metz, on the Moselle twenty miles south of Thionville, and, in addition, a buffer line along the Moselle from Metz through Nancy, Epinal, and Remiremont, all the way south to the vicinity of l’Isle-sur-les-Doubs.

In mid-September this projected line, named the Weststellung, or West Line, existed largely on paper. North of Aachen, for example, construction of permanent fortifications and obstacles had barely begun, and south of the city the old West Wall defenses needed to be completely rebuilt. Between Thionville and Sarralbe, the Maginot Line defensive works, although more formidable, would either have to be altered to face westward or demolished. South of Sarralbe and opposite the 6th Army Group, the only activity on the trace of the proposed line was the hasty construction of some field fortifications in the Vosges by civilian forced labor and a few pioneer battalions.

As the VI Corps was about to begin its attack, the opposing German forces were desperately trying to buy time to turn the Weststellung into a solid defensive position. Army Group G’s most immediate concern was not the Belfort Gap or the Vosges defenses, but defenses in the area around Metz and Nancy. There the progress of Patton’s Third Army had kept the German First Army off balance, making it impossible for Blaskowitz to assemble and direct a strong armored counterattack with Lt. Gen. Hasso von Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army against Patton’s southern flank, as Hitler had ordered. The Third Army had continually forced the First Army back, and Blaskowitz’s concerns had been almost entirely defensive. At the insistence of von Rundstedt, whom Hitler had brought back to command OB West in early September, he finally launched a counterattack with one panzer corps on 9 September, but by the 14th these forces had been shattered by Third Army units assisted by the Seventh Army’s French II Corps driving east of Dijon.

To gain additional strength for a renewed effort, Blaskowitz requested authorization to pull the bulk of the Nineteenth Army back to the Moselle River, keeping some forces west of the river in front of the Belfort approaches. Von Rundstedt referred the matter to OKW, and Hitler approved the withdrawal on the 15th, with the proviso that Army Group G launch the new counterattack no later then 18 September. To ensure its success, OB West ordered Blaskowitz to send both the 11th Panzer Division and the 113th Panzer Brigade from the Belfort Gap area north to von Manteuffel.

By 17 September Army Group G had completed most of the redeployments and command shufflings necessitated by the scheduled counterattack. In the far north the First Army held Army Group G’s right wing with two corps between Trier and Nancy. In its center, the Fifth Panzer Army occupied a thirty-mile front from Nancy to the

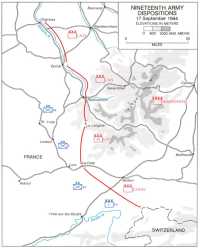

Rambervillers area just north of Epinal. Both armies faced units of Bradley’s 12th Army Group. South of Rambervillers, the Nineteenth Army stood opposite Devers’ small 6th Army Group along a front stretching for about ninety miles (Map 13). Along the Moselle, from Charmes ten miles south to Epinal, the Nineteenth Army’s LXVI Corps held the river line with a motley collection of 16th Division and Group Ottenbacher remnants, stragglers from other kampgruffen chopped up in the Dijon salient, two battalions of the 29th SS Police Regiment, and some Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine “retreads.”

From Epinal southeast eleven miles along the Moselle to Remiremont and another eleven miles southwest to La Longine, the Nineteenth Army’s LXIV Corps took over with the 716th Division on its right and the 189th Division (Group von Schwerin) on its left. Next was the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps with the 338th and 198th Divisions deployed on a line, north to south, along a fifteen-mile front west of the Moselle from La Longine south to La Cote, about four miles east of Lure on Route N-19. Below La Cote to the Swiss border, a distance of about thirty miles, was the LXXXV Corps, guarding the Belfort Gap with the 159th Division on its right, Group Degener in the center, and the 11th Panzer Division on the south. Wiese had somehow managed to retain the panzer division until the night of 18–19 September, but its departure was imminent. Only the headquarters of Corps Dehner, currently based inside Belfort city, remained uncommitted.

From 15 to 19 September Truscott’s final eastward advance had pushed back the Nineteenth Army units holding positions west of the Moselle from Remiremont south to the Doubs River. The German withdrawal to new defensive lines was well under way across most of the front by the morning of the 19th, which accounts for the diminishing resistance experienced by the VI Corps and the French II Corps. By the evening of 19 September the II Corps French troops were within two miles of La Cote; elements of the 3rd Division were scarcely three miles from La Longine; the 36th Division had a reinforced infantry battalion two miles from Remiremont; and the 117th Cavalry Squadron had closed within four miles of Epinal. Thus, although Patch and Truscott feared that the Germans might have reestablished a firm defensive line by the 19th, both Blaskowitz and Wiese were concerned whether their units could make much of a showing south of Charmes with the Allied forces seemingly still in hot pursuit.

How close the Nineteenth Army was to collapse at this juncture is hard to estimate. Due to the command and administrative confusion throughout the force, even determining its general strength and actual dispositions is difficult. Employing the German practice of counting only troops under the combat battalion headquarters as combat effectives, Wiese’s infantry strength numbered about 13,000 men on 19 September, with the total strength of the divisions deployed across the Nineteenth Army’s front perhaps three to five times as high. But these figures are conjectures only, and even these estimates leave out the numerous kampfgruppen, security

Map 13: Nineteenth Army Dispositions, 17 September 1944.

and police units, Army service units, and Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine troops filling in here and there as infantry, some of which may have been counted in with the total infantry division effectives. Other organizations in the Nineteenth Army’s area included security, fortress, and engineer units, which were generally associated with the construction of the Weststellung defenses and were thus under Army Group G control, but could pass to the Nineteenth Army in an emergency. Also included in this category were the four-regiment 405th Replacement Division and various static artillery units. Under direct army control, Wiese had about 90 pieces of field artillery, roughly 30 infantry light howitzers (75-mm.), and around 25 dual-purpose 88-mm. guns. The 11th Panzer Division, reduced to about 25 tanks as of 19 September, was beginning to receive some replacements and new equipment, but was still only marginally effective. In sum Wiese would have an increasingly difficult time holding back a general 6th Army Group offensive, or even a smaller one if it was concentrated in the right area.

Meanwhile, events north of the Nineteenth Army’s front had begun to threaten its right flank. Von Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army launched an attack toward Lunéville on the 18th and Nancy on the 19th, but both offensives were too weak to have any chance of success. Von Manteuffel’s left wing was quickly forced back by the advance of the U.S. Third Army’s XV Corps across the Moselle, and, in the process, Wiese’s northernmost force, the LXVI Corps, was pushed back farther east. The evening of 19 September thus found it in disarray, trying to regroup its forces south of Rambervillers and hold the Nineteenth Army’s northern flank between the Moselle and Baccarat, situated on the Meurthe River about ten miles northeast of Rambervillers.

Not surprisingly, Hitler had become increasingly critical of Blaskowitz’s performance. The failure of the Fifth Panzer Army’s counterattack against the U.S. Third Army and the continuous withdrawal of the Nineteenth Army in the face of little more than Truscott’s three divisions had predictably angered the German Fuhrer. Hitler had never established a close relationship with the apolitical Blaskowitz and, unwilling to take any action against von Rundstedt, relieved the Army Group G commander on 21 September. Blaskowitz was replaced by Lt. Gen. Hermann Balck, formerly the commander of the Fourth Panzer Army on the Russian front. But whether Balck or any other German general could greatly influence the coming battles along the German frontier was problematic.