Chapter 15: The Road to St. Die

At the beginning of October, the American commanders, Generals Devers, Patch, Truscott, and Haislip, realized that their personnel and supply problems made it impossible to launch a general offensive, even if approved by SHAEF. Before any major operations could be undertaken, their troops had to be rested, replacements brought up and trained, and supply stocks, especially ammunition and fuel, built up in the forward area. During this process, front-line infantry strength would have to be reduced by about one-third as infantry battalions were pulled out of the line for brief periods of rest and rehabilitation. For a while, no regiment could plan to have more than two of its three infantry battalions at the front at any one time. The expectation that the poor weather experienced in late September would only worsen during October made ammunition stockpiling even more necessary. Difficult flying conditions greatly reduced the amount of air support the ground troops could count on and increased the reliance on artillery and mortar fire.

Tactical considerations also militated against a hasty push to the east. All the roads from the Seventh Army’s base areas along the Moselle River led steadily upward into the thickly forested Vosges, terrain in which the Germans would continue to have every conceivable defensive advantage. The steep, wooded hills were rarely traversable by vehicles, even by the lighter American tanks and half-tracks, while the narrow mountain roads were easily interdicted; furthermore, heavy vegetation made it difficult to direct accurate artillery and mortar fire or to employ direct air support. The forests also tended to compartmentalize the battlefield, making it easy for advancing units to become widely separated and vulnerable to infiltration and enemy flanking attacks.

The VI Corps

On a larger scale, Truscott was increasingly concerned over the difficulty in securing a deep but narrow advance into the mountains. The VI Corps could not push very far east and northeast of Rambervillers without dangerously exposing its northern flank. To avoid such a situation, Patch and Truscott had hoped that Haislip’s XV Corps would have been able to clear the Parroy forest rapidly and

then begin a drive northeast of Rambervillers abreast of the VI Corps. The tenacious German defense of the Parroy forest, however, destroyed whatever ideas the two commanders may have entertained in that regard before October was a week old. As a result, the XV Corps was unable to launch any offensive operations in the southern sector of its zone, and the VI Corps was forced to commit sizable forces in the Rambervillers area throughout October in order to secure its northern flank.

On the VI Corps’ right, or southern, flank, a similar situation prevailed. There the French II Corps had been stalled in the foothills of the Vosges, and the situation was further complicated by the diverging courses of the two Allied armies, the American Seventh moving northeast and the French First advancing east. Nevertheless, both Patch and Truscott were willing to take the risks that accompanied a unilateral VI Corps attack. Both regarded a complete cessation of offensive activity as extremely dangerous, giving the Germans too much time to build and man defenses throughout the Vosges as well as to rehabilitate their own depleted divisions.

Despite their tactical and logistical limitations, Patch and Truscott still favored a limited VI Corps offensive in October. While neither expected a quick breakthrough to Strasbourg, they believed that the city of St. Die was a reasonable objective. On the Meurthe River deep in the heart of the Vosges, St. Die was an industrial, road, rail, and communications center that VI Corps would have to seize if any drive northeast across the Vosges was to succeed. Route N-59 and the principal trans-Vosges railroad came into St. Die from the north, through Lunéville and Baccarat; Route N-420 and the railroad led northeast from St. Die through the Saales Pass, on the most direct route to Strasbourg; N-59 continued east from St. Die through the Ste. Marie Pass to Selestat, on the Alsatian plain between Strasbourg and Colmar; Route N-415 led south and then east through the Bonhomme Pass to Colmar; and Route D-8 branched off N-415 on its way south to Gerardmer, Route N-417, and the Schlucht Pass. Possession of the Meurthe River mountain town was thus vital to the Allied advance, and the Germans could be expected to defend it vigorously if allowed the time to reorganize and strengthen their forces.

VI Corps’ most direct route to St. Die started at Jarmenil, on the Moselle about midway between Epinal and Remiremont. This axis followed the valley of the small Vologne River, passing through open, flat-to-rolling farmland dominated on the north and northwest by the relatively low, wooded hills and ridges of the Faite forest and on the south and east by higher, more rugged, forested terrain. Route N-59A and then Route D-44 led northeast along the Vologne about ten miles from Jarmenil to the small city of Bruyères, a rail and road hub ringed by close-in, steep hills on the west, north, and east. From Bruyères, Route N-420 went north about two and a half miles to Brouvelieures on the Mortagne River—here no more than a brook. Winding and hugging the slopes of heavily wooded hills, N-420 continued northeast

about four miles to Les Rouges Eaux. Then the highway climbed and twisted through a dense coniferous forest to emerge in the valley of the Taintrux Creek about two and a half miles short of St. Die. The city itself lay on flat ground surrounded by wooded mountains and hills (some of the hills having a peculiar conical shape). The Meurthe River, flowing northwest through St. Die, was normally too slow to be much of an obstacle except in a few places where it ran between steep banks or manmade retaining walls.

While keeping his sights on St. Die, Truscott initially assigned the 45th and 36th Divisions the more limited goals of seizing the railroad and highway hubs of Bruyères and Brouvelieures. Eagles’ 45th was to make the main effort, striking for Brouvelieures and Bruyères from the Rambervillers area, while Dahlquist’s 36th, advancing from the south, was to keep the German frontal defenses occupied and ultimately assist in clearing Bruyères.1 The 45th Division’s advance from Rambervillers would send it southeast, down over nine miles of forests and country roads along the southern side of the Mortagne River valley. To the south, the 36th Division would have to clear the Vologne River valley and route D-44 from Docelles to Bruyères, a distance of about eight miles. The VI Corps attack to seize Bruyères and Brouvelieures was to begin on 1 October, and Truscott hoped to have both objectives in hand by 8 October at the latest.

The German Defenses

The fall of Rambervillers in late September had again forced the Germans to rethink their defensive dispositions.2 For some time the town had marked the boundary between Army Group G’s Fifth Panzer Army, which confronted the Third Army’s XV and XII Corps, and the Nineteenth Army, which faced the Seventh Army’s VI Corps and all of the First French Army. American XV and VI Corps operations in the Rambervillers sector had threatened to drive a wedge between the two German armies as early as 28 September; at that time the Nineteenth Army’s LXVI Corps, consisting largely of the rebuilding 16th Infantry Division, lacked the strength to restore the situation. To consolidate command in the Rambervillers area, which he considered critical, General Balck of Army Group G had transferred control of LXVI Corps from the Nineteenth Army to the Fifth Panzer Army. But on the 30th, Balck had withdrawn the LXVI Corps headquarters from the front and passed control of the 16th Division to the XLVII Panzer Corps, on the Fifth Panzer Army’s left, or southern, flank.3 On the same day Balck also pushed the boundary between the Fifth Panzer Army and the Nineteenth Army south about eleven miles from Rambervillers to a northeast-southwest line passing just north of Bruyères, a line that corresponded roughly to the

boundary between the VI Corps’ 45th and 36th Divisions.

Thus, at the beginning of October, the 2nd French Armored Division of XV Corps and the 45th Infantry Division of VI Corps faced General von Lüttwitz’s XLVII Panzer Corps, Fifth Panzer Army, in the Rambervillers area. The panzer corps consisted (north to south) of the weak 21st Panzer Division; Group Oelsner, a provisional infantry regiment made up of security troops, engineers, and Luftwaffe retreads, all soon to be incorporated into the 16th Division; and the lamentable 16th Infantry Division itself. The 21st Panzer Division had 65 percent of its authorized strength of about 16,675 troops, but the unit had little punch left. Its 22nd Panzer Regiment was reduced to nine operational tanks, and the 125th and 192nd Panzer Grenadier Regiments were down to about 50 percent of their authorized strengths. The division’s only strong points were its high percentage of seasoned veterans and its rigorous training program for replacements. The 16th Infantry Division, then being reorganized as a volksgrenadier division,4 had an effective strength of about 5,575 ill-trained troops, and its three infantry regiments averaged about 35 percent of their authorized strength. The Germans rated the division as capable only of “limited defense.”

Backing up von Lüttwitz’s front-line units were the fortress troops of Group von Claer, with a total strength of about 8,000 men. The group’s principal components were Regiment A/V5 and provisional Regiment Baur, each with five infantry battalions and some supporting artillery and antitank weapons. But von Lüttwitz’s control over Group von Claer was limited. The group’s primary mission was to man Weststellung positions, and its troops could be employed in front-line combat only with the expressed permission of General Balck.

South of the Bruyères–St. Die boundary between the Fifth Panzer Army and the Nineteenth Army stood the latter’s LXIV Corps, the lines of which extended southward about twenty miles to Rupt-sur-Moselle. With the 716th Division and the 198th Division (less the 308th Grenadiers) on line from north to south, the LXIV Corps, under Lt. Gen. Helmut Thumm, faced VI Corps’ 36th Division as well as most of the 3rd Division.6

General Wiese of Nineteenth Army had in reserve the small task force from the 11th Panzer Division as well as the 103rd Panzer Battalion, just arriving at St. Die from the First Army’s sector. The 106th Panzer Brigade, intended for the Belfort Gap, had not yet arrived from First Army, and Balck had laid tentative plans to divert the brigade

to the critical Rambervillers sector. There, Fifth Panzer Army had in reserve Task Force Liehr of the 21st Panzer Division and what was left of Regimental Group Usedom, a unit that had launched a counterattack against units of the French 2nd Armored Division northeast of Rambervillers on 2 October.7 Badly damaged during that action, Group Usedom then had to dispatch one of its two panzer grenadier battalions to bolster the forces defending the Parroy forest. Losses, redeployments, and blocking commitments thus left the Fifth Panzer Army with no reserve worthy of the name to support the XLVII Panzer Corps until the 106th Panzer Brigade arrived.

Von Lüttwitz’s panzer corps had other problems as well: a shortage of artillery ammunition; a lack of heavy machine guns and mortars; and, above all, a critical shortage of infantrymen. Consequently, General von Manteuffel, commanding Fifth Panzer Army, queried Balck on the possibility of withdrawing portions of the panzer corps to the east of Rambervillers, where it would find better defensive terrain.8 However, the Army Group G commander, adhering to his policy of no withdrawals and immediate counterattacks against any and all Allied penetrations, refused permission for any retreat and likewise turned down von Manteuffel’s requests for more infantry and heavy weapons. The most Army Group G could promise was to increase deliveries of ammunition. At the time, Balck felt that the Fifth Panzer Army, whatever its problems, was still better off than Wiese’s tottering Nineteenth Army in the Vosges and the Belfort Gap.

First Try for Bruyères and Brouvelieures

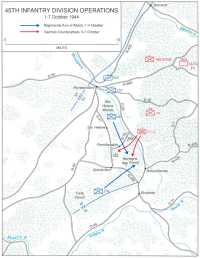

The 45th Division’s attack toward Brouvelieures and Bruyères demanded that the Rambervillers area be secured first, in order to protect the division’s northern flank. The 157th Infantry and the 117th Cavalry Squadron accomplished this task by blocking the roads leading northeast, east, and southeast from Rambervillers, while maintaining contact with the XV Corps’ French 2nd Armored Division in the north. These requirements, however, together with the German domination of the generally open country immediately east of Rambervillers with artillery and mortar fire, prevented the division’s left from mounting any significant attacks toward Baccarat, and left General Eagles, the division commander, with only two regiments for his main effort. Nevertheless, the 45th Division commander hoped to outflank the Germans by taking an indirect approach to his objective. While pushing his 179th Infantry regiment north through the Faite forest, he wanted the 180th to make a wide swing to the left, moving up to the Rambervillers area and then heading southeast through the Ste. Hélène woods, between two secondary roads (D-50 and D-47) and the small Mortagne River, to attack the German lines from the side and rear (Map 19).

Map 19: 45th Infantry Division Operations, 1–7 October 1944.

At first the attack went as planned. While the 157th secured Rambervillers, the 180th Infantry cleared most of the mile-wide Bois de Ste. Hélène by 29 September, meeting only scattered German delaying actions. German defenses, however, stiffened along D-70, a small road that bisected the 180th’s advance southward and marked a general boundary between the gentle Ste. Hélène woods and the more rugged Mortagne forest guarding the final approaches to both Bruyères and Brouvelieures. To the south, the 179th Infantry emerged from the Faite forest about the same time, but found it difficult to cross the narrow N-420 valley road skirting the southern edge of the Mortagne forest. By October 2, after three days of hard fighting, the 180th managed to take Fremifontaine, a small hamlet on D-70, and the 179th secured Grandvillers; however, the stubborn 16th Volksgrenadier Division infantry hung on to a defensive network centered around three prominent elevations—Hills 385, 422, and 489. Nevertheless, the German defenses now appeared ready to collapse.

Late on 2 October, as Eagles’ converging regiments prepared to continue the offensive into the forest itself, von Manteuffel advised Balck that the XLVII Panzer Corps lacked the means to launch a counterattack to recapture Grandvillers and Fremifontaine, and two days later he convinced the Army Group G commander that the situation in the sector was becoming irretrievable. Heavily engaged in the Parroy forest battle, the Fifth Panzer Army had no significant resources that it could deploy south. By that time the 180th and 179th Infantry had penetrated deeply into the Mortagne forest, bypassing German positions on Hill 385, driving a wedge between two of the 16th Division’s regiments, and approaching to within a mile of Brouvelieures itself. Reinforcements were needed if the 16th was to survive.

At the time Balck could do little. On 5 October he released two reserve battalions to the XLVII Panzer Corps, which, together with some odds and ends that von Manteuffel had been able to scrape together, the Army Group G commander hoped would save the situation.9 But von Manteuffel warned that the reinforcements were inadequate, prompting Balck to allow portions of the 11th Panzer Division north of the Rhine–Marne Canal to be pulled out of the line, despite the constant pressure there from Patton’s Third Army.

The counterattacking force that von Manteuffel finally assembled thus consisted of the 11th Panzer Grenadiers of the 11th Panzer Division, ten to twelve Mark IV medium tanks from the same division, and four infantry battalions under 16th Division control. Covered by German forces on Hill 385, much of the infantry and a few of the armored vehicles assembled in the Mortagne valley about three-quarters of a mile east of Fremifontaine; the rest of the tanks and additional infantry gathered at the head of a ravine about a mile to the south; and two more infantry battalions came together another mile farther south. For the northern elements of the German counterattack the most

83rd Chemical (Mortar) Battalion, 45th Division, fire 4.2-inch mortars, Grandvillers area.

important objective was Hill 422, an American-held height three-quarters of a mile southeast of Fremifontaine that provided good observation in all directions. The two southern infantry battalions were to support the attack on Hill 422 and were also to strike for Hill 484, a mile and a half farther south and a similar distance east of Grandvillers, the ultimate objective.10 If the German counterattack developed properly, it would slam into the left and rear of the 180th Infantry north-west of Brouvelieures and sever the tenuous contact between the 179th and 180th regiments, perhaps cutting off the 180th.

The counterattack, which began about 0900 on 6 October, took the two 45th Division regiments by surprise. Although the assembly of noisy tanks and self-propelled guns was difficult to muffle, the weakening German resistance during the previous days may have given the American attackers a false sense of security; moreover, deep in the forest it was difficult to tell friend or foe by noise alone. By late afternoon the German northern wing had seized Hill 422

and cut off much of the 2nd Battalion, 180th Infantry, opening a wide gap between the two American regiments. In the south, however, the two attacking German battalions made little headway in the Hill 484 sector and were in turn outflanked by aggressive 179th Infantry counter-maneuvers. The fighting continued throughout the night, quickly degenerating into a continuous series of violent but confused skirmishes, with neither side being able to accomplish much in the dark forests.

On the morning of 7 October, the American units began reorganizing and started eliminating the German penetrations. The 180th Infantry retook Hill 422 while the 179th isolated the German southern assault forces from the panzer grenadiers in the north and, in the process, secured all of Hill 484. Deciding that no more could be accomplished, von Manteuffel directed the 11th Panzer Division’s task force to start disengaging during the night of 7–8 October, leaving the 16th Division to reestablish a defensive line as best it could.

When the front finally stabilized on 9 October, the 180th Infantry had established a new line extending from the vicinity of Hill 385—still in German hands—south across Hill 422 to the regimental boundary just north of Hill 484. The German counterattack had thus forced the regiment to pull its front to the west and south about three-quarters of a mile, and had cost it 5 men killed, 40 wounded, and about 30 missing (most of these last, captured). The 179th Infantry had also pulled back and was preparing a defensive line extending southwest from Hill 484 to the northeastern slopes of the Faite forest, after losing 18 men killed, 64 wounded, and about 25 missing. The 179th had captured around 30 Germans, and the 180th nearly 50.

The German attack had not succeeded in its larger objective—retaking Grandvillers and Fremifontaine—which again illustrated Army Group G’s inability to push any counterattack through to a decisive conclusion. On the other hand, the operations had forced the 179th and 180th Infantry regiments to take up defensive positions; the units would need nearly a week before they were ready to resume offensive operations. The XLVII Panzer Corps had at least bought some time for its hard-pressed left flank.

The 36th Division

Truscott had intended that Dahlquist’s 36th Division only support the 45th’s attack on the Bruyères–Brouvelieures area. At the time, the division had been slowly pushing northeast up the Vologne and D-44 valley, clearing out elements of the German 716th Infantry Division from the wooded hills on either side of its advance. By 1 October the 36th Division’s 143rd regiment, on the left wing, had moved through the eastern edge of the imposing Faite forest to Docelles and Deycimont, while the 141st regiment, at the division’s center, had come up abreast of the 143rd on the eastern side of the river, crossing first Route D-11 and then D-30 to secure the town of Lepanges (Map 20). To the southeast, the division’s remaining regiment, the 142nd, had emerged from the steep hills and valleys of the Froissard forest to

Map 20: 36th Infantry Division Operations, 1–14 October 1944

cut D-11 near the mountain hamlet of Tendon. The regiment, reinforced by a battalion of the 141st, had then gone on to occupy two hill masses north of the road, Hills 728 and 827, cutting the 716th Division’s lateral communications with Le Tholy and threatening Route D-30, which now became the defenders’ main supply artery in the region. But despite their success, all three of Dahlquist’s regiments were exhausted, and the terrain between their current positions and Bruyères was, if anything, even more difficult. Yet any attempt to take what was obviously the easiest and most direct route to their objective area—marching straight up the Vologne River valley, with German units of unknown size in the forests on both flanks—seemed extremely dangerous.

Believing that at least one of his regiments should be removed from the line for rest and refitting, Dahlquist decided to make his main effort east of the Vologne, through a rectangular terrain compartment bounded by the towns of Laval, Herpelmont, Houx, and Lepanges—about twelve square miles of mountainous forests nearly devoid of human habitation. Possession of the area would secure his right flank for an advance up the east bank of the Vologne to Bruyères, leaving the Faite forest to the 45th Division, with security forces along the river itself covering his left flank.

To accomplish this, Dahlquist planned to have the 141st regiment, with its two battalions and attached armor, make the division’s main assault between Lepanges and St. Jean-du-Marche. The 141st would be supported by a secondary attack north

from the ridge line of Hill 728–827 toward D-30 between Houx and Rehaupal, and beyond. But Dahlquist gave the latter task to the 143rd Infantry, transferring it east from the Faite forest area and moving the tired 142nd into reserve for a long-needed rest. During the repositioning, the 143rd was even able to occupy the town of Houx on 2 October; henceforth, a small north-south road between Houx and Herpelmont would mark the boundary between the two attacking regiments.

During the planning process, Dahlquist had considered making his main effort west of the Vologne River, where his forces might have better complemented the offensive operations of Eagles’ 45th Division. However, he felt that such a move, coupled with the pending redeployment of the 3rd Division on his right flank from the Le Tholy area, would have given the defending 716th Division too much room to prepare a counterattack from the southeast, and so he abandoned the idea.

One of Dahlquist’s major problems was making the best use of his attached armor in this type of terrain. Like most other American divisions, he had one tank battalion and one tank destroyer battalion attached, which he habitually broke up into mixed task groupings. He had already formed one such unit, a small armored blocking force under Lt. Col. Edward M. Purdy, commanding the 636th Tank Destroyer Battalion, to secure the west bank of the Vologne River.11

On 2 October he created a similar grouping, Task Force Danzi, to support the 141st Infantry on the east side of the river.12 While a small part of the force deployed in the St. Jean-du-Marche area to protect the right rear of the 141st Infantry, the main body assembled near Prey, on the Vologne a mile northeast of Lepanges, with the principal mission of assisting the infantry drive toward Herpelmont. On the 3rd, Purdy assumed control of this force, while retaining command of the one west of the Vologne, but both were now subordinate to the 141st regiment.

From 1 to 4 October, the 141st, still with only two infantry battalions, made substantial progress pushing through the heavy forests, and by dusk on the 4th it had secured roughly two-thirds of the rectangle. Its left flank was on the Vologne near Prey, and the right had crossed the Houx–Herpelmont road toward the western slopes of Hill 676, half a mile south of Herpelmont. However, the regiment now began to run out of steam, casualties started to mount, and the Nineteenth Army began deploying reinforcements into the area.

In the 143rd Infantry’s sector, progress had been slower. By 4 October

the regiment had cleared the Houx area, pushed northeast a mile and a half up the Houx–Herpelmont road, and, on the right, advanced over a mile southeast from Houx along Route D-30. But the 143rd quickly discovered that German artillery and mortar fire prevented them from using either of the narrow roads as a supply route or an axis of advance; like the 141st, the regiment was forced to depend on a variety of time-consuming cross-country routes for these purposes. Both regiments also found that German resistance grew stronger as their advance carried them slowly to the east-west road nets of D-51 and D-50 that the Germans were undoubtedly using to supply their forces.

Not surprisingly, armor played a minimal role in the struggle, and in fact the 141st Infantry units complained loudly about the lack of tank support.13 The real problem, however, was the terrain, which restricted vehicles to back roads and trails that were easily interdicted by mines, demolitions, and German artillery fire. In addition, rain and fog severely limited visibility, often leaving the tanks and tank destroyers with nothing at which to fire. The rain and heavy military traffic broke up back roads and turned mountain trails into muddy quagmires that bogged down tracked vehicles; booby-trapped roadblocks, together with numerous mines along most of the better routes, slowed the armor to the pace of engineer clearing operations. Finally, in most cases, the noisy movement of armor along the back roads and main trails, as well as across what open ground there was, immediately brought down carefully registered German artillery, antitank, and mortar fire. The LXIV Corps apparently did not suffer from any serious ammunition shortages.

The limited Vosges offensive produced, in fact, a serious shortage of artillery ammunition in the VI Corps, forcing Truscott to place severe restrictions on the number of daily rounds expended by each of the division’s artillery battalions. Dahlquist’s troops, who were perhaps the most dependent on indirect fire support because of the nature of the fighting, felt the restrictions the hardest. As a partial remedy, on 4 October Dahlquist ordered the division’s tank and tank destroyer units to be attached to one of his three field artillery battalions by night in order to undertake the harassing and interdiction missions normally fired by the artillery batteries, making at least some use of his impotent armor.14

At about the same time Dahlquist also combined Purdy’s task forces into a larger grouping, Felber Force, under Lt. Col. Joseph G. Felber, the commander of the 753rd Tank Battalion.15 At the behest of the 141st Infantry,

Felber Force passed from regimental to division control, but the transfer caused some confusion, leaving the 141st with little control over its armored support. By the morning of 7 October, only two tanks and two tank destroyers were physically with the 141st Infantry. Although a request to division headquarters brought a platoon of tanks and another of tank destroyers back to regimental control, the bulk of the 36th Division’s armor remained assigned to Felber Force under Dahlquist’s direct supervision. Since the advancing infantry could seldom employ more than one or two tanks profitably at any one time, Dahlquist judged it best to keep the bulk of the machines in reserve for the moment.

From 4 October through the 14th, daily progress of both the 141st and 143rd Infantry was measured in yards. Resistance from the 716th Division stiffened markedly and, while the opposition was largely static in nature, German patrols constantly harassed the 36th Division’s supply routes. Herpelmont fell to the 141st Infantry on 8 October, but German artillery fire rendered the road junction untenable. The 141st nevertheless secured Hill 676 south of Herpelmont, as well as the high ground immediately northwest of town. By the evening of 14 October the regiment had also cleared Beaumenil on Route D-50, a mile northwest of Herpelmont, and Fimenil, about a mile short (southeast) of Laval.

Meanwhile, by 10 October, the 143rd Infantry had secured most of the dominating terrain from the southern slopes of Hill 676 south nearly three miles to Route D-30 near Rehaupal. The regiment’s gains allowed artillery forward observers to direct counterbattery fire on German positions along the upper (western) Vologne River valley west of D-50 and on rising ground east of the river.

The 142nd Infantry began moving back into the line on 5 October, but made limited progress in the area south of the 143rd. On 13 October the 142nd took over the 143rd Infantry’s positions from the vicinity of Hill 676 south to Route D-30, while the 143rd prepared to switch back to the 36th Division’s left for a renewed attack toward Bruyères. In fact, during the later stage of their slow advance northward, the 36th Division regiments normally deployed only two battalions on line, switching them back and forth to give each a seven- to ten-day rest. The division also began preparing to resume VI Corps’ drive toward St. Die, to which the limited gains through 14 October had been a necessary, if costly, prelude. The 36th Division’s infantry casualties for the period 1–14 October numbered approximately 85 killed, 845 wounded, and 115 missing, for an official total of 1,045, almost half of which were suffered by the tired 141st regiment.16

Map 21: 3rd Infantry Division Operations, 30 September–14 October 1944.

The 3rd Division

Immediately south of the 36th Division lay the sector of the 3rd Division’s 30th Infantry regiment, which had moved to its parent unit’s left flank on 29 September. The 15th Infantry held the 3rd Division’s center around St. Ame, and on the far right the 7th Infantry held along the Moselle as far as Ferdrupt, nine miles farther south (Map 21). Current VI Corps plans envisaged that elements of French II Corps would soon relieve the 7th Infantry, but the division’s principal objective was still Gerardmer, some ten miles northeast along Route N-417 from St. Ame, with an intermediate objective of Le Tholy, about halfway to Gerardmer. At the time, ongoing negotiations with the French to take over the area had not yet affected the division’s plans.

Located at the junction of Routes D-11 and N-417 five miles northeast of St. Ame, Le Tholy had become the

center of German resistance in the region. Route N-417, representing the most direct avenue to Le Tholy from the Moselle, ran through a mountain valley, along which flowed the Rupt de Cleurie River, actually a small watercourse no larger than a brook. Much of the valley, up to a mile wide, was given over to open, rolling farmland rising on both sides of the stream to rough, forested hills. For over half the distance from St. Ame to Le Tholy, Route N-417 ran along open slopes east of the river, and country lanes provided additional mobility throughout the valley, at least in good weather. However, a number of stone quarries, usually near the tree line, punctuated the upper slopes of the Cleurie valley on both sides of the river, providing the Germans with ready-made defensive positions.

At the end of September General O’Daniel, the 3rd Division commander, intended to send the 15th Infantry directly up Route N-417 from St. Ame toward Le Tholy, supported by the 30th Infantry working through wooded hills along the western side of the valley. Once de Monsabert’s French forces arrived in the south, O’Daniel planned to bring his third regiment, the 7th Infantry, up to the St. Ame area as well to launch a supporting, limited objective attack eastward along the axis of Route D-23, a rather difficult southerly approach to Gerardmer.

Facing the 3rd Division was LXIV Corps’ 198th Division, the unit that had earlier counterattacked the 36th Division in the same area. During the first half of October the German division opposed the advance of O’Daniel’s units with its own 305th Grenadiers, the attached 602nd and 608th Mobile Battalions, two battle groups built on remnants of the 196th and 200th Security Regiments, and a host of smaller ad hoc units that the 198th Division was absorbing to rebuild its depleted ranks. Later the 7th Infantry would also encounter troops of the 198th Division’s 326th Grenadiers on its southern flank, while on the north the 30th Infantry would run into elements of the 716th Division, the bulk of which was battling the 36th Division.

The attack of the 3rd Division, Truscott’s best and most experienced unit, ran into trouble from the beginning. By 1 October, the slowly advancing 15th Infantry had come up against a major German strongpoint at one of the largest quarries, L’Omet, on the eastern side of the valley, only about a mile and a half north of St. Ame, and there the advance of the division up N-417 halted. Unable to force L’Omet, O’Daniel switched his main effort to the 30th Infantry still advancing through the woods west of the valley, but even there progress was slow. Terrain and weather precluded both armor and air support and greatly limited the effectiveness of artillery. Not until 10 October did the regiment reach Route D-11, about a mile and a half northwest of Le Tholy, and secure Hill 781, overlooking Le Tholy on the north. There the 30th Infantry quickly discovered that the Germans had the town—which was in a shambles—well covered by artillery fire and had established strong defenses to the west, making a further advance toward Gerardmer temporarily impossible. The 30th Infantry, accordingly, made no

determined effort to clear Le Tholy or to push eastward through the town. Having suffered some 600 casualties during the period 30 September-10 October, the regiment needed to catch its breath.

In the center the 15th Infantry had meanwhile found the northern and southern entrances to L’Omet quarry nearly cliff-like and covered by German automatic weapons fire, while at the eastern and western approaches the Germans had piled up impressive stone roadblocks across a narrow route through the quarry. Inside the quarry, passageways, tunnels, stone walls, and scrap piles of broken stone provided the defenders with good cover and concealment. Although the number of Germans within the quarry at first probably numbered no more than a few hundred, reinforcements arrived during the battle, while other troops manned machine-gun positions in the adjacent woods to cover most approaches to the quarry. Not surprisingly, infantry assaults on the quarry between 30 September and 2 October proved useless. On the 3rd, two tank destroyers and two special M4 tanks mounting 105-mm. howitzers pumped about 500 rounds of high explosive ammunition into the German defensive works, while mortars of the 1st Battalion, 15th Infantry, lobbed in a week’s allotment of ammunition. The effort had little effect.17

On 4 October the attack continued behind the supporting fire of three artillery battalions, but made little progress until tanks laboriously made their way up to the west entrance, knocking down the stone roadblocks and finally opening up the interior of the quarry to the infantry. The last organized resistance crumbled during midafternoon on the 5th, with some twenty Germans fleeing after most of the defenders had apparently evacuated their positions during the night.

Following the quarry fight, the 15th Infantry found the going easier as the Germans grudgingly gave way. On 6 October the regimental left reached the town of La Forge, about halfway to Le Tholy on Route N-417. German artillery and mortar fire again took command of the highway, however, and it was not until the 11th that infantry from the 15th regiment could secure the town.18 Thereafter the regiment avoided the center of the valley, pushed more rapidly across wooded hills east of the highway, and by the evening of 14 October occupied a line from Route N-417 just south of Le Tholy west another two and a half miles along good, wooded holding ground.

On the 15th Infantry’s right, the 7th Infantry regiment had begun its own infiltration of the Vosges Mountains. At the end of September the 3rd Battalion, 7th Infantry, held positions on high, forested terrain south of St. Ame, which overlooked, to the east, the road junction town of Vagney on Route D-23 and the Moselotte River.

4.2-inch Mortars hit Le Tholy

At the time the 1st Battalion was still based at Rupt-sur-Moselle, seven miles south of St. Ame, and had projected some strength several miles up into the Foret de Longegoutte toward the Moselotte; the 2nd Battalion was concentrated around Ferdrupt, three miles southeast up the Moselle from Rupt. When relieved by the 3rd Algerian Division of the French II Corps, the 7th Infantry was to concentrate in the St. Ame area and then seize Vagney and the nearby forested heights.

Leaving behind small holding detachments, the regiment quietly redeployed its two battalions along the Moselle during the nights of 2–3 and 3–4 October. It began its attack on Vagney late on the afternoon of the 4th, with the 2nd Battalion seizing the high ground north of the St. Ame–Sapois road, and the other units crossing D-23 to secure Hill 822, a mile west of Vagney. After a three-day battle Vagney fell on 7 October, two days earlier than the VI Corps and 3rd Division had expected.

This time the Germans defended their mountain strongholds with vigor. About 2020 on the 7th, German infantry, with the support of two tanks, launched a desperate counterattack into Vagney. In the fog and darkness the 7th Infantry’s troops mistook the lead German tank for a

vehicle of the 756th Tank Battalion, which had a platoon of mediums in the area. The German armor then penetrated quickly into the town, taking the command posts of both the 1st and 3rd Battalions under fire, which led to a wild melee before the German force was finally ejected.19

Brushing off the German counterattack, the 7th Infantry’s right pushed up the Moselotte River on the 8th to secure Zainvillers, a mile south of Vagney, but not before the Germans blew the Zainvillers bridge. The left meanwhile reached out along D-23 toward Sapois, a mile and a half west of Vagney. After three days of stubborn resistance the Germans withdrew from Sapois, and troops of the 7th Infantry moved in, ending the regiment’s last significant action in the Vagney area. Plans to push part of the 7th Infantry toward Gerardmer along Route D-23 had been abandoned by this time, and already elements of the regiment had moved out of the line as troops of the 3rd Algerian Division began arriving from the south to relieve the American unit.

Relief and Redeployment

Since 28 September, discussions had been under way between the U.S. Seventh and First French Armies regarding the movement of the inter-army boundary north, which would give the French more room to maneuver against the northern approaches to Belfort and allow Truscott to pull the 3rd Division out of a region that had become a dead end for the VI Corps. Truscott wanted the 3rd Division to spearhead a renewed offensive toward St. Die, while de Monsabert felt the St. Ame–Vagney region would give him a back door to the German defenses at Le Thillot and southward. The subsequent relief of the 3rd Division caused some problems between the American and French commands, and between Truscott and Patch as well. The 3rd Algerian Division, beset by supply and transportation problems and engaged in a new offensive against the Gerardmer–Le Thillot area, had been unable to move northward in strength as rapidly as the American commanders had expected. Meanwhile German resistance in the Vagney area had proved stronger than estimated, making it dangerous for the 7th Infantry to disengage until the Algerians had substantial strength on the ground. In the interim, sharp differences arose between Patch and Truscott over the scope of 7th Infantry operations in the area, and later between the French and the Americans when de Monsabert’s forces were finally able to assume responsibility for the additional territory.20

Trouble began on 7 October when the VI Corps directed the 3rd Infantry Division to be prepared to move most of the 7th Infantry out of the line after 1000 on the 8th, replacing the infantry with engineer and armored units. During the course of the 8th, however, Seventh Army informed VI Corps that such preparations were premature. Keeping close track of the French progress northward as well as their attacks on Le Thillot and Gerardmer, Patch realized that the 3rd Algerian Division could not possibly take over the 7th Infantry’s positions on 8 October, and instead recommended that the 7th continue its attacks eastward in support of de Monsabert’s offensive. Truscott objected, fearing that the attacks would tie up the 7th Infantry for some days; furthermore, he pointed out that Patch’s orders of 4 October had limited the 7th Infantry’s responsibilities to the seizure of Vagney and neighboring high ground. After more discussion, Patch reluctantly agreed that it would probably accomplish little to have the 7th Infantry advance farther along Route D-34, but insisted that the regiment maintain strong pressure to the east.

Truscott and General O’Daniel interpreted the Seventh Army instructions as loosely as possible. On the 9th O’Daniel pulled the 2nd Battalion, 7th Infantry, out of the front line and, by the morning of the 10th, had also assembled the 7th regiment’s 1st Battalion in reserve at Vagney. Meanwhile the two commanders had agreed between themselves that the 7th Infantry would make no further efforts south; consequently, the 7th never went beyond dispatching a few small patrols out of Zainvillers. At the time, both Truscott and O’Daniel were more interested in preserving the strength of both the 3rd Division and its 7th regiment for the projected drive on St. Die and did not want to commit the regiment deeply into the Moselotte valley. In the end, the 7th Infantry left only a small holding detachment at Zainvillers, pending the arrival of French troops, and abruptly ended its advance in the north after securing Sapois on the 11th. Following the fall of Sapois, O’Daniel began redeploying the rest of the 7th Infantry, replacing them by the morning of the 12th with two companies of the 48th Engineer Combat Battalion.21 All American pressure against the German forces in the area was thus relaxed, well before the French offensive just to the south ended.

By the 12th even Truscott, who now realized that de Monsabert’s corps could initially put little more than a reconnaissance squadron and an FFI battalion in the Sapois–Vagney–Zainvillers area, began to have second thoughts about the speed of the 3rd Division’s disengagement; he, therefore, directed O’Daniel to leave at least one battalion of the 7th Infantry at Vagney for added security. However, two days later, on 14 October, Devers officially moved the inter-army boundary north of Route N-417 and Le Tholy, and between 14 and 17 October the French II Corps assumed responsibility for the area, relieving first the remaining 7th Infantry battalion and then the 15th regiment. It was not until 23 October,

though, that units of the 36th Division finally relieved O’Daniel’s last regiment, the 30th, in the Le Tholy–La Forge area west of N-417. None of O’Daniel’s regiments had accomplished much in any of their zones since the 11th, giving little support to de Monsabert’s offensive between 4 and 17 October and allowing the Germans ample time to rebuild their battered defenses before the newly arriving French units could begin to pose a threat. All in all, the lack of coordination between the two Allied forces did not augur well for the future.

The Vosges Fighting: Problems and Solutions

As the VI Corps moved into the High Vosges during late September and early October, wear and tear on its three infantry divisions greatly accelerated. As early as 26 September General O’Daniel, commanding the 3rd Division, observed a significant decline in the aggressiveness of his infantry units. Explanations that the troops were wet and tired and developing a certain caution—based on a general feeling that the war would soon be over—failed to satisfy O’Daniel, who urged his subordinate commanders to emphasize that a go-easy attitude could only prolong the war and increase casualties. Dahlquist, commanding the 36th, later noted the disciplinary problems that all VI Corps units were experiencing, especially desertions among the line infantry companies in combat (50–60 cases per division) and the ever-present straggler phenomenon that had afflicted the corps since the initial landings. In part he felt these difficulties were a product of the heavy officer and NCO casualties sustained by the fighting units in both Italy and France and the resulting decline in leadership as enlisted men were rapidly promoted to take up the slack.22

Other VI Corps officers echoed these concerns. The commander of the 3rd Division’s 15th Infantry felt that his regiment’s quality was slipping. Replacements, he averred, were often inept and poorly trained. Moreover, the many veterans of the regiment’s bitter fighting in the snow-drenched mountains of Italy had little stomach left for another winter’s operations in French mountains. In the 45th Division the 180th Infantry reported about sixty-five recent combat fatigue cases, while at the same time skin infections were becoming endemic, largely as the result of constant wet weather and a chronic shortage of bathing facilities. Col. Paul D. Adams, commanding the 143rd Infantry of the 36th Division, reported an almost alarming mental and physical lethargy among the troops of his regiment, and General Dahlquist, the division commander, had to tell General Truscott that the 36th had little punch left.

Dahlquist felt that he had been driving his troops too hard and, after privately discussing the problem with his regimental commanders, had established small division rest camps for his infantrymen. According to Colonel Adams, the troops needed to be rested continually during the late

autumn and winter fighting in the Vosges because of the terrain and weather. “It takes about three days [of rest] with men that age,” he judged.

You give them three days and they’ll ... be back in shape without any trouble. Just leave them alone, let them sleep and eat the first day, make them clean up the second day, and do whatever they want to do the rest of the time, and they’ll be ready to go.23

Once the division headquarters became sensitive to the issue of battle fatigue, Adams felt, the 36th did much better despite the hardships it had undergone and would continue to meet in the future.

Improvements in the Seventh Army’s supply situation might have alleviated some of these problems, but General Devers’ optimism over the capabilities of his Mediterranean supply lines proved premature. Despite the fall of Marseille, Toulon, and the lesser Riviera ports and the best efforts of Army logisticians in the communications zone, the 6th Army Group’s land supply lines were still overextended. At the end of September the Seventh Army requested daily rail delivery of some 4,485 tons of supplies and ammunition for the period 1–7 October; however, the 6th Army Group’s G-4, now responsible for setting rail priorities, could allocate to the Seventh Army only 2,270 rail-tons per day, and actual receipts ran well below that figure. On 5 October, for example, the Seventh Army received only 1,655 tons by rail, and on the 6th about 1,670 tons. During the same two days the Seventh Army received by rail only 20 tons of ammunition, while its units were expending ammunition at the rate of nearly 1,000 tons per day. To make up for rail deficiencies, the 6th Army Group had to continue to rely on long truck hauls, but increasingly bad weather, deteriorating highways, vehicle maintenance requirements, and the 400-mile distance from ports to forward depots combined to make road transportation increasingly difficult and slow. In addition, moving supplies from forward depots to units in the field also proved arduous as the tactical forces moved farther into the mountains.

General Truscott had one solution to his tactical transportation problems. On 2 October, anticipating the hardships of mountain campaigning, he requested two pack trains from Italy. After numerous delays, the 513th Pack Quartermaster Company finally arrived in the Vosges area on 23 November with 300 mules and a veterinary detachment. Dividing the mule trains between the divisions still in the Vosges, the mule skinners and their charges were able to haul rations and munitions to the infantry units by night. Although providing forage for the animals was a problem, the users reported little or no interference from German artillery or mines and booby traps; and resupply, even in the most difficult terrain, was possible.24 Had the animals and trained handlers been readily available earlier, they obviously would have been useful throughout the Vosges campaign.

Ammunition was another concern.

Artillery munitions: vital in the Vosges

Even before Truscott began his limited October offensive, VI Corps was feeling the pinch of a shortage of artillery and other types of munitions.25 On 2 October, for example, the 30th Infantry of the 3rd Division reported that it was down to 300 rounds of 81-mm. mortar rounds and was approaching the exhaustion of its M1 rifle ammunition. Severe rationing was the only immediate answer. Throughout the 3rd Division, for example, O’Daniel limited 60-mm. mortar ammunition expenditures to eight rounds per weapon per day and 81-mm. mortars to eleven rounds, 105-mm. howitzers to thirty-two rounds, and 155-mm. howitzers to thirty rounds. During much of the early part of October, however, Seventh Army depots could not even furnish enough ammunition to meet these restricted rates. Even .30-caliber ammunition was sometimes critically short, and the 3rd Division had to almost denude the support units of small arms ammunition to supply its rifle companies and machine-gun platoons. For several days, in fact, there was no M1 rifle ammunition to be found at the Seventh Army’s expanding supply installations in and around Epinal. To preserve morale, Truscott even prohibited the dissemination of information on overall ammunition allocations below the level of infantry regiment and divisional artillery headquarters.

Although the VI Corps’ ammunition shortages were partly overcome by mid-October, quartermaster supplies and rations remained a problem. Units often had to exist on half-rations or live off packaged, hard rations for days at a time. More serious, clothing for wet, cold weather was scarce. Winter clothing did not begin to arrive in adequate amounts until after 20 October, and even by the end of the month shoe-pacs (rubberized boots), heavy sweaters, and extra-heavy socks were available to only about 75 percent of the infantry. Heavy, long overcoats were on hand, but their usefulness was doubtful, for the field units reported that the garment was “too bulky for reconnaissance and armored units to use in their compact fighting compartments ... [and] so immobilizing that it cannot be worn by the infantry, and, if issued to them, will be discarded the first time they attack.”26 The infantry much preferred the long, lined M-1943 field jacket, and the 3rd Division gradually managed to amass enough of these jackets to outfit its infantry battalions. Other units reported shortages of signal and engineer equipment of all types throughout October, but the technical service units generally accomplished their missions through improvisation, substitution, and outright scrounging.

The solution to many of these problems was the strengthening of the logistical organizations supporting the 6th Army Group. To this end, on 18 September the Continental Base Section (CBS) at Marseille moved an advanced echelon of its headquarters to Dijon, and on the 26th, the Continental Advance Section (CONAD), under Maj. Gen. Arthur R. Wilson, became operational at Dijon, absorbing the advanced echelon of CBS. Supply agencies along the Mediterranean coast then passed to the control of a new headquarters, Delta Base Section (DBS), under Brig. Gen. John P. Ratay. Retaining some personnel from the old CBS, DBS obtained additional manpower from Northern Base Section on Corsica, which ceased to exist. At the same time SOS NATOUSA (still located at Caserta, Italy) set up an advanced echelon at Dijon under Brig. Gen. Morris W. Gilland. The French logistical agency, Base 901, divided its personnel between DBS and CONAD, with most of Base 901 moving up to Dijon with CONAD, and Brig. Gen. Georges Granier becoming the deputy commanding general of CONAD for French affairs. Although the various changes were phased in fairly rapidly and all became effective on 1 October, several weeks were necessary before the new organizations could function smoothly and support the army group’s growing requirements. However, in some areas theater logisticians were powerless. The shortage of artillery ammunition, for example, was a theater-wide concern, and the solution would ultimately depend on increasing production in the United States and Great Britain.27

In the end, terrain and weather were the most decisive factors in defining the character of the Vosges fighting.

With only ten good flying days during the month of October, Allied air power was less effective interdicting German troop movements behind the battlefield, and Allied ground units were more dependent on artillery fire support despite the shortage of ammunition. Armor, except as mobile artillery, was less useful in the mountains, leaving the bulk of the fighting on both sides to the infantry battalions; even here the compartmentalized terrain made it difficult to maneuver units that were larger than platoons and squads. In the words of one regimental commander:–

The fighting during the month of October was comparable to jungle fighting, where ... maintenance of direction was most difficult because of the dense forests. This alone resulted in many erroneous reports as to locations of units and enemy positions. Difficulties arose as orders based on the best available information, which was frequently inaccurate, miscarried, and at times resulted in bitter and unexpected fighting ... [and he advised that] all commanders must report actual conditions carefully, avoiding all possibility of errors in locations of units and omitting entirely reports based on optimism rather than fact. Forest areas must be mopped up thoroughly. Small, well-dug-in enemy detachments if not mopped up will harrass supply columns, and present difficult problems of liquidation because of our inability to use our supporting weapons inside our lines... . Sometimes the enemy deliberately lets us get as close as seventy-five or one hundred yards to him before disclosing his presence with fire, and on occasion lets the leading elements pass by. This reduced the fight to a small arms fight with the enemy enjoying the advantage of good cover... . Holding the top of a hill or even what is ordinarily termed the military crest of a wooded hill does not necessarily give us control of the surrounding terrain. We must require all units engaged in capturing a hill covered with forests to continue down the forward slopes until the open country is under small arms fire and artillery observation.28

Interestingly, General Balck of Army Group G also likened the situation in the Vosges to jungle fighting, the key to which he considered to be having plenty of infantry on hand.29 To this, all small-unit commanders could readily agree.

Truscott probably also would have agreed with these judgments. The weather, terrain, and lack of infantry had prevented him from putting more force in the push to Bruyères and Brouvelieures. Nevertheless, the VI Corps was still in a better position to make a more decisive effort toward St. Die and ultimately Strasbourg and the Rhine. Securing the Rambervillers area in the north and the sector defined by Le Tholy and Route N-417 in the south gave the corps more protection on both of its flanks, while the 45th and 36th Divisions had just about cleared the way to Bruyères and Brouvelieures in the center. At the same time, both of these divisions had managed to rest many of their infantry battalions, never putting their full strength on the line. In the south, the arrival of French units finally allowed Truscott to pull almost the entire 3rd Division into reserve, where it would rest and refit for the major VI Corps offensive soon to follow. Meanwhile, on the German side, the combat strength of the 16th and 716th Infantry Divisions had been steadily eroded, and the two units had been regularly pushed back, giving

them little time to improve their defensive positions and forcing their parent corps to commit what reserves they had to shore up their patchwork defensive lines. If the Seventh Army and the 6th Army Group could solve some of their more serious logistical problems and expand their unique supply routes through southern France, a more concentrated VI Corps push through the Vosges might well split the two weakening German divisions far apart.