Chapter 16: Approaching the Gaps: Belfort

While the XV Corps moved out of Lunéville toward the Mondon and Parroy forests and the VI Corps began its approach to the Moselle, the First French Army had marked time, waiting for the men, matériel, and supplies that would ultimately fuel de Lattre’s offensive against the Belfort Gap. For the moment strong German resistance along the approaches to Belfort made any limited efforts futile, and the French had to be content with moving up the rest of their units from southern and central France and deploying them on line. Yet, perhaps even more than the American commanders, the French leaders were restless. French territory and people lay before them—towns, villages, and hamlets still under German rule and subject to the caprices of the harsh German occupation. Moreover, the German defenses still appeared to be weak in many areas, especially in the mountains where dense forests made it difficult to establish a continuous line of resistance. It was a temptation that French officers found hard to resist.

The Initial French Attacks

On the First French Army’s left, or northern, wing, de Monsabert’s II Corps positioned the French 1st Infantry and 1st Armored Divisions on the northern routes to Belfort; in the center and on the right, or southern, wing, General Bethouart’s I Corps reinforced the 3rd Algerian Division with the 9th Colonial Infantry Division and Moroccan Tabor units from southern France. General du Vigier’s armored division had finally been strengthened with its third combat command, and, like Truscott, he and de Monsabert were eager to move east before the German defenses had solidified. Although many of de Lattre’s units were still arriving from North Africa, American difficulties on the northern flank of the French army soon gave the French tactical commanders an opportunity for action.1

By 23 September both Truscott and

O’Daniel had also become concerned about the growing gap between the U.S. VI Corps and the French II Corps, especially considering the 3rd Division’s failure to make any headway on its right wing toward the Moselle. Although French and American cavalry units had tried to cover the sector between the two Allied forces, they had been stretched thin and were unable to move up Route N-486 to Le Thillot. Le Thillot itself, a key road junction town on the upper reaches of the Moselle River, lay in the French zone of advance and had become one of the major anchors of the German defenses in the mountains north of Belfort. Accordingly, on 23 September, Truscott asked de Monsabert if his forces could assume complete responsibility for Le Thillot area. At the time he suggested that the French make an armored thrust up N-486 from Lure complemented by a second French drive on Le Thillot from the north, using the crossing sites at Rupt and La Roche that O’Daniel’s 3rd Division had finally secured. Since the American forces were encountering only spotty defenses along the Moselle, there was no reason to believe that the French would not find the area equally permeable at some point. Enthusiastic, de Monsabert quickly passed the request on to de Lattre, who approved the proposal that evening with the proviso that the effort be limited to one combat command of the French 1st Armored Division and one regimental combat team of the French 1st Infantry Division.

Planning began immediately. De Monsabert wanted the 1st Armored Division’s Combat Command (CC) Sudre to move through the sector of the 3rd Division and attack Le Thillot from the north, on the eastern side of the Moselle. CC Caldiarou, the new arrival, was to push up Route N-486 with the 3rd African Chasseurs toward Le Thillot from the south; and CC Kientz and a brigade of the French 1st Infantry Division was to launch a supporting attack south of the highway. The plan obviously called for more strength than the limited forces approved by de Lattre; but both de Monsabert and du Vigier, still commanding the French 1st Armored Division, viewed the American request as an opportunity to outflank the main German defenses at Belfort between Lure and Issy-les-Doubs, and hoped that a quick strike by du Vigier’s entire division might catch the Germans by surprise.

The French southern attack began early on 25 September, and the main assault on Le Thillot started on the 26th after the attacking units had moved up to forward assembly areas. De Monsabert’s plans were flexible. He hoped to catch the Germans unawares and either cut a path through the southern Vosges to Belfort from the north or push directly over the Vosges via Gerardmer and the Schlucht Pass to Colmar and the Rhine. Much depended on speed, surprise, and the ability of the armor to find a weak point in the German lines—some road or pass where defenses had been neglected, poorly organized, or perhaps completely ignored.

The effort, however, proved premature. Despite the speed of the attacks, the French found the Germans better prepared than in the north. The

narrow roads leading to Le Thillot jammed the attacking armor, and the battles for the heavily wooded, steep hillsides along the highways put a premium on infantry. As the attacks slowed down, the Germans were able to clog the French avenues of advance even further with reinforcements, making the quick penetration that de Monsabert and du Vigier had hoped for impossible. The fighting was similar to that encountered by the XV Corps, now attempting to clear the Parroy forest, and to that which would be experienced by the VI Corps in its drive for Bruyères and Brouvelieures. Between 26 and 29 September progress by the French in the southern Vosges was minimal, and the attacking forces lost about 115 killed, 460 wounded, and 30 missing.

Rather than terminate the failing offensive, de Lattre chose to reinforce it. Realizing that de Monsabert had surpassed his instructions, he nevertheless approved the II Corps commander’s initiative. His own estimates regarding the time necessary to bring up enough supplies and troops to launch a major frontal attack against the Belfort Gap had been too optimistic; by the end of September it was obvious that the First French Army as a whole would not be ready to resume the offensive until 20 October at the earliest. In the meantime, de Monsabert’s attacks would at least put some pressure on the enemy and, at the very least, divert German attention away from the Belfort Gap. For these reasons de Lattre agreed to increase de Monsabert’s infantry strength, transferring both the 3rd Algerian Infantry Division and the 3rd Moroccan Tabor Group to the II Corps, and promising him the 2nd Tabor Group, the two-battalion French parachute regiment, and the assault battalion as soon as they arrived. In addition he increased the frontage held by Bethouart’s I Corps, with the 9th Colonial Division and the recently arrived 2nd Moroccan Division, by about fifteen miles, thus allowing the II Corps to narrow its focus of attack. Devers, after extensive negotiations with de Lattre, also moved the French II Corps boundary north, to encompass the entire Rupt-Le Tholy–Gerardmer area, despite the fact that the 3rd Division had not yet been able to penetrate into the region very deeply.

Logistical Problems

During the boundary discussions, de Lattre took the opportunity to thrash out his logistical problems with Patch and Devers. Charging that the French had been short-changed regarding supplies and equipment, he asserted that the lack of gasoline had prevented him from bringing up enough troops and ammunition to the battle area, thus forcing de Monsabert to break off his attack before it had a chance to succeed. The “unfavorable treatment” afforded his army in the matter of supplies, he went on, was inexcusable and “seriously endangered its existence and operations.”2

Generals Marshall, de Lattre, and Devers visit French First Army headquarters in Luxeuil, France, October 1944.

In a memorandum he also included statistics showing that the First French Army, with five reinforced divisions in the forward area, had received about 8,715 rail-tons of supplies between 20 and 28 September, while the Seventh Army, with three divisions at the front, had received roughly 18,920 rail-tons during the same period.

In a subsequent conference to iron out these difficulties, Seventh Army representatives initially took the position that any supplies that the army could spare from VI Corps’ allocations had to be sent to the recently acquired XV Corps. They also pointed out the 6th Army Group—no longer Seventh Army—was now responsible for the logistical support of the First French Army. In private, Seventh Army logisticians believed that French supply problems stemmed largely from inadequacies in their own supply services. General Devers agreed in part, observing that the French had been slow to build up supply surpluses in the forward area. At the same time, however, he concluded that during its period of responsibility for French supply, the Seventh Army had not adequately monitored logistical operations supporting de Lattre’s forces and had generally favored Truscott’s units in such matters.

Based on these judgments, Devers instructed the Seventh Army to meet

the most urgent logistical requirements of the First French Army. Therefore, after the conclusion of a series of conferences with First French Army representatives on 1 October, the Seventh Army G-4 recomputed requirements and stocks and allocated 65,000 gallons of gasoline, 53,000 rations, and about 280 tons of ammunition to the French. An additional 60,000 gallons of gasoline were to be turned over to them on 2 October, and the Seventh Army also agreed to make up daily shortages of rations and gasoline for the First French Army until a revised rail-supply schedule for the French went into effect on 4 October.3

For the moment de Lattre appeared satisfied. On 8 October, however, during a visit by General Marshall to the 6th Army Group, the French commander launched into another tirade about his supply problems, embarrassing Devers and angering Marshall.4 Later de Lattre more or less apologized to Devers over the incident, but there were no easy answers to French logistical problems. A basic difficulty was the ability of the Seventh Army to consistently “outbid” the small French army headquarters for supplies and matériel; the larger, better-trained American staffs were simply more efficient in forecasting the logistical needs of their units and justifying those requests with detailed statistical data. In addition, the larger number of trained American supply officers and agencies—depots, accounting offices, repair facilities, and so forth—allowed the Seventh Army to control its internal stockage and expenditure of supplies and equipment with an efficiency that the French understandably could not hope to match. As a result, 6th Army Group logisticians would have to step in at various times during the coming campaigns and approve special supply allocations to the French to make up for critical deficiencies. Until the French Army had been completely rebuilt at some future date, there was no other solution.

French Plans

Early in October new French plans called for a major assault through the High Vosges north of the Belfort Gap, continuing and expanding de Monsabert’s original effort.5 Somewhat chastened by his failure to take Le Thillot, de Monsabert believed that, despite the reinforcements sent by de Lattre, the II Corps lacked the strength to seize Gerardmer and push through the Schlucht Pass. Instead, he hoped to force a passage through the Vosges, taking a more southerly

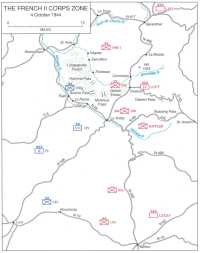

route between Gerardmer and Le Thillot. The 3rd Algerian Infantry Division, redeploying from I Corps, was to take over II Corps’ left to make the main thrust. The Algerians, covering on their left toward Gerardmer and the Schlucht Pass, were to aim their effort twenty-five miles east across the Vosges from the Longegoutte forest to Cornimont and La Bresse and ultimately to Guebwiller, at the edge of the Alsatian plain and about thirteen miles south of Colmar (Map 22).

In the center, du Vigier’s 1st Armored Division was to support the Algerian effort by renewing its attacks in the Le Thillot area and, if successful, was to continue eastward on Route N-66 through the Bussang Pass to St. Amarin and Cernay, seven miles south of Guebwiller. On the II Corps’ right, or southern, wing, the French 1st Infantry Division was to act as a hinge anchoring the eastward attack in the vicinity of Ronchamp on Route N-19. Ultimately, de Monsabert hoped that the division would also be able to push eastward just above the city of Belfort. Meanwhile, opposite the Belfort Gap, the French I Corps, with the 2nd Moroccan Division on the left and the 9th Colonial on the right, was to undertake a few limited attacks to tie down German forces that otherwise might be shifted to the II Corps front.

De Lattre had initially wanted to add the strength of the French 5th Armored Division to the offensive. The 5th—the third and last of the three French armored divisions equipped by the Americans—had begun arriving in southern France from North Africa on 19 September but, because of French supply and transportation problems, would not close the front until the 20th of October and consequently could play no part in the October attacks. Its arrival in France marked the last major elements of the First French Army to reach the metropole. With only a few minor combat and service units of the approved French troop list remaining in North Africa or on Corsica, further French reinforcements would have to depend on local recruitment and training.

In any case, what de Monsabert needed was not armor, but more infantry. With de Lattre’s blessing, therefore, he reinforced the attacking units with the 2nd and 3rd Tabor Groups, the parachute regiment, the African Commando Group, and the Shock Battalion. In reserve he left the 1st Moroccan Tabor Group, the 2nd Algerian Spahis Reconnaissance Regiment (an armored reconnaissance squadron), and, when it arrived sometime after 4 October, the 6th Moroccan Tirailleurs (a regimental combat team of the 4th Moroccan Mountain Division). De Monsabert also planned to employ a number of FFI units to the full extent of their capabilities.

During the initial phase of the attack, de Monsabert wanted the 3rd Algerian Division to push its left east across the Moselotte River in the Zainvillers and Thiefosse areas. Simultaneously, its right was to drive north across the Longegoutte forest ridges through the Rahmne Pass, a little over two miles northeast of the Moselle. In the center, the 1st French Armored Division, reinforced heavily with light infantry, was to outflank Le Thillot on the north via the southeastern portion of the Longegoutte

Map 22: The French II Corps Zone, 4 October 1944

3rd Algerian Division moves up to the Rupt area.

and Gehan forests and cut the German lines of communication between the Moselotte valley and Le Thillot in a drive that would carry to Cornimont, on the upper Moselotte valley. At the same time the division was to continue pressure toward Le Thillot down Route N-66 southeast from Ferdrupt as well as along N-486 from the southwest.6

The 3rd Algerian Division began moving into its new sector early on 3 October, and de Monsabert set 4 October as the date his corps would start its new attack. All in all, de Monsabert would begin his October offensive with more strength than was available to Truscott’s VI Corps.

The German Defense

At the beginning of October, General Wiese’s Nineteenth Army had two corps facing de Lattre’s French forces, the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps in the High Vosges and the LXXXV Corps in the Belfort Gap, both now veteran organizations of the southern France campaign.7 Facing de Monsabert’s attacking II Corps, the IV

Luftwaffe Field Corps had on line, north to south, the 338th Infantry Division, the 308th Grenadiers of the 198th Division, and Regiment C/V.8 The LXXXV Corps extended the German front south and southeast another twenty-five miles, blocking the southern approaches to Belfort. Facing the far right of the French II Corps and most of Bethouart’s I Corps, LXXXV Corps deployed across its front the rebuilt 933rd Grenadiers,9 the 159th Reserve Division, and three provisional brigades—Groups Degener, von Oppen, and Imisch—employing an assortment of fortress units, police formations, and other odds and ends.

Balck, Wiese’s superior, decided that the Nineteenth Army urgently needed a strong, mobile tactical reserve to supplement the small task force that the 11th Panzer Division had left behind; he, therefore, directed the First Army, on Army Group G’s northern wing, to disengage the 106th Panzer Brigade and the 103rd Panzer Battalion and dispatch both units south to the Belfort sector.10

Although primarily worried about the situation in the Rambervillers area, Balck was obviously concerned about the German defenses in the Belfort Gap. At the time he believed that French operations in late September around Le Thillot presaged a more determined effort to outflank the gap on the north, but was equally concerned about increasing French pressure directly toward Belfort from the west and south, an error made when German intelligence mistook the troop movements of de Lattre’s organizational reshuffling for reinforcements to the French forces opposite the Belfort Gap. Looking over the collection of units in Wiese’s two southern corps, he characterized their effectiveness as “deplorable,” and complained that “never before have I led in battle such motley and poorly equipped troops.”11 Nevertheless, he finally decided to divert the small mobile reserves from the First Army—the 106th Panzer Brigade and the 103rd Panzer Battalion—to the more critical Rambervillers–St. Die area at his center, leaving Wiese with only the detachment of the 11th Panzer Division as a reserve in the south.12 Ultimately, the German forces in the south would have to make do with their own resources.

The II French Corps’ October Offensive

The renewed offensive of the French II Corps into the Vosges began on 4 October during weather—heavy rain and dense fog—that could hardly have been worse for either infantry or armor in the forested mountains. In general the revised French dispositions pitted the 3rd Algerian Division against LXIV Corps’ 198th

Infantry Division in the Longegoutte and Gehan forests southeast of St. Ame; the French 1st Armored Division against the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps’ 338th Infantry Division centered around Le Thillot and the surrounding mountains; and the French 1st Infantry Division against assorted IV Luftwaffe and LXXXV Corps units south of Le Thillot. Although all the French divisions had been beefed up with additional infantry—Moroccans, paratroopers, FFI units, and so forth—they again made little progress during the first days of the offensive. De Monsabert quickly discovered that O’Daniel’s 3rd Division had done little more in the Rupt–Ferdrupt area than secure the Moselle River bridgeheads, and the attacking French found that they had to fight their way into the heights above the Moselle before they could even attempt to penetrate the Vosges valleys and passes beyond.

On the 4th, the main body of the 1st Armored Division made no progress toward Le Thillot, but on the division’s left the attached 1st Parachute Chasseurs, spilling over into the 3rd Algerian Division’s sector, found gaps in the German defenses along the southern slopes of the Longegoutte and Gehan forests, and pushed several miles north of the Moselle into the Broche and Morbieux passes. De Monsabert quickly decided to exploit the paratroopers’ success and directed the armored division to concentrate all possible strength on its left for a rapid thrust northward through the two forests into the Moselotte valley. The rest of the division was to limit its operations to covering actions that would maintain some pressure on German forces along the rest of the division’s front.

Alarmed, the Germans began reinforcing 338th Division13 forces in the forests, but on the 5th the French armored division again made significant gains. The left drove through Rahmne Pass to the northern slopes of the Longegoutte forest, while the right pushed through the Gehan forest over a mile east of the Morbieux Pass. The 338th Division thereupon pulled the 308th Grenadiers14 out of the line and assembled the regiment for a counterattack on 6 October.

At first, the German attack achieved considerable success, forcing the French to pull back from the passes and several of the surrounding hills. Confused, bitter fighting raged for two days as units on both sides became isolated or cut off, and both French and German casualties mounted rapidly. Meanwhile, to the south, French armor had managed to push its way down Route N-66 along the north bank of the Moselle, but was finally stopped one mile short of Le Thillot, again failing to take the key junction town. The Germans, however, had no intention of holding on to the two forests. The 338th Division began to break off the action during the night of 7–8 October and the next night withdrew across the Moselotte, keeping only the northernmost section of the Gehan forest near Cornimont,

and leaving the French with their first foothold in the High Vosges.

The initial affray had been expensive for the Germans—the 308th Grenadiers lost over 200 men taken prisoner alone—and the Nineteenth Army had to scrape up reinforcements for both LXIV Corps and IV Luftwaffe Field Corps. The army now sent forward four fortress machine-gun battalions, three fortress infantry battalions, and, demonstrating the scope of the German replacement problem, 150 troops from an NCO school at Colmar. Wiese also sent some assault guns and the small task force of the 11th Panzer Division northward from the Belfort area to Le Thillot, which had now become the key to the German defensive line in the area under attack.

Taking up the offensive as the Germans withdrew, the 3rd Algerian Division began attacking east and south from the St. Ame area between 9 and 13 October. Pushing only about six miles east of Vagney, its advance was continually hampered by foul weather and increasing supply problems. The inability of the II Corps to secure the road hub at Le Thillot forced the French to employ long, circuitous supply routes through St. Ame to support both the reinforced 3rd Algerian Division and fully a third of the 1st Armored Division. Driving across or along one forested height after another, the French gained control of high ground and muddy mountain trails, but German artillery, mortar, and antitank fire made it impossible for them to use the main, paved roads through the valleys.

During the period 9–13 October progress was limited on the 3rd Algerian Division’s left, where flank protection requirements and the need to take over American positions absorbed much of its strength. Heavier fighting took place at the center and especially on the right, where the Algerians assumed responsibility for the Gehan forest sector. They cleared the last Germans from the northeastern part of the Gehan forest on 13 October and the same day cut route N-486 near Travexin, a mile or so south of Cornimont, which fell to the French on 14 October after the departing Germans had burned down most of the village.

Pausing briefly to redeploy units and build up supplies, the Algerians resumed the attack on 16 October. On the left the objective was La Bresse, a road junction town between Cornimont and Gerardmer. In this sector the 6th Moroccan Tirailleurs of the 4th Moroccan Mountain Division led off.15 Crossing N-486 north of Cornimont, the Moroccans pushed up Hill 1003 (Le Haut du Faing), dominating the upper Moselotte valley as far as La Bresse. A bloody three-day battle ensued as the 6th Moroccans—suffering about 700 casualties in the process—first seized the broad height and then secured it against strong German counterattacks. However, the 3rd Algerian Division could make no substantive progress elsewhere during the period 16–18 October, and the Moroccan infantrymen found it impossible to advance beyond Hill 1003.

To the south, CC Deshazars16 of the 1st French Armored Division drove east along the axis of Route D-43 from Travexin with the immediate objective of seizing the Oderen Pass, which would provide a rather indirect and difficult route across the High Vosges. The combat command’s infantry advanced about two miles east of Travexin along high ground north and south of D-43, but the armor, in the face of German fire, could not break out of the mountain village. Beyond some isolated gains, the best the French armored division had to show after three days was possession of that portion of Route N-486 north of Le Thillot. But the achievement was of little value to the French as long as the Germans still controlled the junction of Routes N-66 and N-486 at Le Thillot itself and were able to resupply the town from the south.

By 17 October General de Lattre had had enough. Never completely enamored of General de Monsabert’s plan to drive across the High Vosges in a deep, northerly envelopment of the Belfort Gap, the First French Army commander, on 17 October, decided to bring the operation to a halt. While the II Corps had made substantial gains in the area north and northeast of Le Thillot across a front of nearly twelve miles, de Lattre concluded that they had been too costly and indecisive. Moreover, south of Le Thillot, the right wing of II Corps had made no significant progress. Nowhere were de Monsabert’s forces ready or able to drive through the passes of the High Vosges and into the Belfort Gap or the Alsatian plains. Meanwhile, the transfer of troops and supplies to de Monsabert’s forces had virtually immobilized General Bethouart’s command, which, during the first half of October, had had little opportunity to begin preparations for its own offensive directly through the Belfort Gap.

Also evident to de Lattre, the forces of the II Corps had been exhausted by the slow forest fighting. The 3rd Algerian Division and its attachments were spread thin in the mountains and valleys; the 6th Moroccan Tirailleurs had been chewed to bits in just three days of action; and the 1st Parachute Chasseurs (attached to the 1st French Armored Division) was operating on little more than esprit de corps. The terrain, coupled with German artillery and antitank fire, had made it impossible for the French 1st Armored Division to bring its firepower to bear; its own infantry forces, some three battalions, were equally tired. Supply problems were increasing with every yard the French gained, while unusually poor weather (exceptionally early snow had already fallen in the Vosges) complicated both logistical and tactical operations.

To resume the attack, de Monsabert would need either fresh infantry reinforcements or direct assistance from Truscott’s VI Corps. De Lattre realized that both solutions were out of the question. Truscott, resting the 3rd Division for his main attack on St. Die, was not about to shift the division back to Le Thillot; throwing more French strength into the Vosges

would probably force de Lattre to postpone his offensive against the Belfort Gap for several months. All the French infantry, except for minimum essential reserves and some poorly equipped FFI units of questionable quality, had already been committed. Moreover, Devers was pressing de Lattre to relieve the 1st Airborne Task Force along the Riviera and in the Maritime Alps, a task that could only divert more French infantry from the Vosges and Belfort sections. Even worse, de Lattre soon learned, the French provisional government was making plans to mount an all-French operation to secure the port of Bordeaux on the Atlantic coast, an effort that might force him to relinquish two of his divisions for at least several months.

De Lattre thus concluded that the tactical situation, the state of his army, and the heavy rains, snowfalls, and freezing temperatures expected in the mountains (the early harsh weather of October seemed to foreshadow a severe winter) made it impracticable for the First French Army to push strong forces into Alsace except through the relatively easy terrain of the Belfort Gap. A resumption of de Monsabert’s assault in the north could well result in immobilizing the bulk of the First French Army along the western slopes of the Vosges until springtime. Instead, de Lattre decided, his offensive center of gravity would have to be shifted back to the Belfort Gap sector, and preparations to launch his long-planned offensive there would be given first priority. Henceforth, de Monsabert’s activities would be limited to consolidating the gains already made, while conducting limited patrols and perhaps some minor offensive actions to keep German attention focused on the area.

General de Monsabert learned of de Lattre’s decision on 17 October and formally halted the corps’ Vosges offensive the next day. Although disappointed that his attacks had not made greater gains, he continued to feel, with characteristic optimism, that further reinforcements would have allowed the II Corps to regain its momentum and drive through the Vosges passes within a short time. Yet, de Monsabert could find some satisfaction in his corps’ accomplishments since the beginning of October. The II Corps had freed over 200 square miles of French soil; had driven the enemy from many French towns, villages, and hamlets; had liberated thousands of French citizens; and, by French estimates, had killed about 3,300 Germans and captured over 2,000 more during the period 1–18 October—the equivalent of nine German infantry battalions.17 The command had also forced the Germans to reinforce their front with numerous infantry and weapons battalions from the main Weststellung positions, thereby weakening that defensive line; it had likewise prompted the Germans to redeploy other troops from the Belfort Gap sector to bolster the Vosges front. The French offensive had even forced the German commanders to import additional reinforcements into the Vosges from other areas, including Germany

proper. Finally, under the most miserable conditions of terrain and weather and while facing shortages of artillery ammunition and other supply problems, the French II Corps had beaten back the strongest counterattacks the Germans would mount.

Perhaps de Monsabert’s real problem was the inability of Devers at this stage to coordinate the efforts of the Seventh Army with those of the French and to move the full weight of the 6th Army Group against the German defenses. However, as in the north, such a unified offensive would have to wait for major improvements in the Allied supply situation. In the meantime, it remained to be seen whether Truscott’s VI Corps or Bethouart’s I Corps could profit from the sacrifices of de Monsabert’s forces and the attention that Wiese and Balck had been forced to pay to the southern Vosges.