Chapter 17: Into the High Vosges

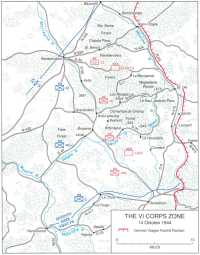

While the U.S. XV Corps and the French II Corps undertook only limited operations during the second half of October, VI Corps resumed its drive toward St. Die on the 15th.1 The renewed attack had several objectives. First was the seizure of Bruyères and Brouvelieures. To sustain the offensive toward St. Die, the VI Corps still needed the rail and highway facilities in this region, lying at the center of the corps’ axis of advance. Second, Truscott wanted to secure a suitable line of departure along the constantly rising, forested terrain east and northeast of Bruyères and Brouvelieures. With these areas in hand, the VI Corps could begin its main attack—a three-division drive on St. Die—on or about 23 October, spearheaded by O’Daniel’s 3rd Division. Appropriately named Operation DOGFACE, the attack was to carry the VI Corps at least as far as the high ground that overlooked a ten-mile stretch of the Meurthe River valley and Route N-59 between St. Die and Raon-l’Etape (Map 23). DOGFACE, in turn, would constitute a prelude to an even larger offensive scheduled by Devers for mid-November, which would push the entire 6th Army Group over the Vosges and through the Belfort Gap.

Planning the Attack

General Truscott, commanding the VI Corps, had no illusions about the difficulties of carrying DOGFACE through to a rapid conclusion, or even of quickly executing the preliminaries of the operation against Brouvelieures and Bruyères that were to begin on 15 October. While VI Corps’ general supply situation had improved since the beginning of the month, some problems remained. The distribution of winter clothing was far from complete, critical shortages of mortar and artillery ammunition persisted, and even stricter rationing had to be imposed on artillery expenditures. The 13th Field Artillery Battalion of the 36th Division, for example, estimated that during the last half of October the unit could have fired a ten-day ration of its 105-mm. howitzer ammunition profitably in about ten minutes. Furthermore, Truscott felt that the VI

Map 23: The VI Corps Zone 14 October 1944.

Corps lacked the heavy artillery needed for mountain fighting in the Vosges. About the only bright spot in the picture was the availability of ample ammunition for tanks and tank destroyers as well as for the cannon companies of the infantry regiments. But how much use the armor would be in the increasingly difficult terrain was very hard to predict.

Truscott also had misgivings about the condition of his infantry. For the DOGFACE preliminaries against the Bruyères–Brouvelieures region, the picture was particularly bleak. On the north the 157th Infantry of the 45th Division and the 117th Cavalry Squadron were fully occupied with securing the VI Corps’ left flank at Rambervillers and maintaining contact with the XV Corps. Until the 3rd Division’s thrust, which was to pass through the 45th Division’s right, allowed the 45th to redeploy strength northward, the 157th and 117th could contribute little, leaving the burden of the fighting to the 179th and 180th regiments. But these two units had not yet recovered from their failure in early October to seize Bruyères and Brouvelieures, and both were still tired and understrength.

The status of the 36th Division was mixed. The division had been reinforced for the 15 October preliminaries by the Japanese-American 442nd Regimental Combat Team. This unit, composed primarily of American citizens of Japanese ancestry, had arrived in France from Italy at the end of September and was experienced and relatively fresh.2 However, the efforts of the 36th Division to rotate its infantry battalions in the line during the first half of October had been only partially successful in providing rest and rehabilitation. In addition, all of the division’s nine infantry battalions had a serious shortage of foot soldiers, with the individual rifle companies averaging about 121 officers and enlisted men out of an authorized strength of 193 (but the 442d’s companies averaged 180 men).

For the attacks on the Bruyères–Brouvelieures area, the 36th Division would have available only the 442nd and 143rd Infantry regiments. The rest of the division was temporarily confined to defensive roles, covering the corps’ right flank and relieving the 3rd Division’s 30th Infantry in the Le Tholy–La Forge sector. The 36th Division’s right-flank units (and the 30th Infantry as well) were also to participate in a deception effort designed to make the Germans believe that the 3rd Division, rather than redeploying, was actually concentrating for an attack eastward from the Le

Tholy area toward Gerardmer in conjunction with the French II Corps offensive to the south.

Truscott expected that the 3rd Division’s infantry would be in better shape for the main DOGFACE offensive. While the 36th and 45th Divisions were securing Brouvelieures and Bruyères between 15 and 23 October, O’Daniel’s division would be resting at least two of its infantry regiments, the 7th and the 15th, for one week or more following their relief by French II Corps forces. However, the division’s 30th Infantry, holding defensively in the Le Tholy–La Forge area, might not be available until later; therefore, the 3rd Division would probably have to begin its attack toward St. Die, the main DOGFACE effort, with only two-thirds of its combat strength.

Truscott also worried about the terrain and weather his troops would be facing during both the preliminary operations and DOGFACE itself. His staff expected that precipitation would increase during the last half of October, with rain, wet snow, fog, mist, and low-hanging clouds continuing to hinder both tactical air support and airborne forward observers (artillery spotters in light aircraft). On the ground, forward artillery observers would often be unable to see potential targets or analyze the results of friendly fire. The rising, rough, and often densely forested terrain lying on the corps’ route of advance would also complicate the problems of artillery registration and observation. Compared to the Vosges, the affair of the XV Corps in the Forest of Parroy would appear tame.

The rugged Vosges terrain continued to provide the Germans with various natural defensive advantages—advantages which they could be expected to improve on throughout the coming battle. To the left of Route N-420—the main road leading to St. Die—the vast, wooded ridge and mountain complex of the Rambervillers forest stretched northward over eight miles to Route N-59A, linking the towns of Rambervillers and Raon-l’Etape. The main part of the forest averaged about five miles in width, west to east; but a southeasterly portion, the Magdeleine woods, extended another five miles to culminate in heights of some 2,100 feet overlooking St. Die. Between Routes N-59A and N-420 only one second-class road, Route D-32, penetrated the difficult terrain, although many lesser unpaved roads, trails, and tracks cut through all reaches of the old forest.

To the right and south of Route N-420 lay the equally rugged and wooded terrain of the Domaniale de Champ forest, bisected only by a third-class road, D-31, which passed along the valley floor of the small Neune and Taintrux streams. East of D-31 the terrain was equally difficult until reaching the Meurthe River valley and the north-south Route N-415, which linked St. Die with Gerardmer and roughly constituted the VI Corps’ right, or southern, boundary.

In the DOGFACE preliminaries, the center and right of the 45th Division, with the 180th Infantry on the north and the 179th to the south, were to seize Brouvelieures and then push north of the Mortagne River, east and west of Route N-420. The 180th Infantry would first clear the high,

wooded ground that the Germans still held west of Brouvelieures, including Hill 385. At the same time, the 179th Infantry would seize Brouvelieures from the south and, in support of the 36th Division’s attack on Bruyères, clear the forested hills between the two towns. Once these tasks had been accomplished, the two regiments would secure forward assembly areas across the Mortagne River for the main DOGFACE attack.

As its share of the DOGFACE preliminaries, the 36th Division was to advance north, with the attached 442nd Regimental Combat Team on the left and its organic 143rd regiment on the right. The 442nd, striking east across wooded hills west of Bruyères, would seize the town, clear the surrounding heights, and then push a few miles farther to the village of Belmont, coming abreast of the 45th Division units on its left. Meanwhile, the 143rd Infantry would secure crossings over the Vologne River in the Laval region and then head northeast along the Neune River valley to Biffontaine, four miles east of Bruyères, thereby anchoring the right flank of the assembly area. The rest of the 36th Division was to hold defensive positions along high ground south of Biffontaine, ultimately relieving the 30th Infantry, 3rd Division, in the Le Tholy area.

The 36th Division thus had an extended front—over ten miles from Biffontaine to Le Tholy—but Truscott evidently felt the division would have little problem with the task. The battles during the first half of October had seriously depleted German strength in the area between the Vologne River and Le Tholy, and Truscott estimated that planned deception operations and limited French pressure would keep the Germans on the defensive in this sector. Then, when the 3rd Division began its surprise attack toward St. Die, German attention would be diverted from the 36th Division’s right flank to the center of the VI Corps’ zone. The risks seemed acceptable.

Finally, during the DOGFACE preliminaries the 3rd Division was to redeploy secretly to positions behind the center and right of the 45th Division. From there the 3rd Division would eventually lead the main attack on 23 October, striking through the 45th Division and pushing toward St. Die generally on the edge of the Rambervillers forest between Routes D-32 and N-420. Once the 3rd Division’s surprise attack was well along, the 45th Division would shift its strength northward to clear the northern section of the Rambervillers forest from D-32 to Route N-59A, and the 36th Division would push east through the Domaniale de Champ forest, further anchoring the corps’ right flank.

German Deployments

On 15 October the Fifth Panzer Army’s XLVII Panzer Corps still held a 23-mile front that included the roughly six miles between Rambervillers and Bruyères.3 At the time, the 21st Panzer Division had responsibility for the northern part of the Rambervillers–Bruyères sector, and the 16th Volksgrenadier Division had the southern

half; the small town of Autry on Route D-50 marked the boundary between the two units. Below the Bruyères region, the Nineteenth Army’s LXIV Corps covered from Laval south through the area around Le Tholy with the 716th and 198th Divisions. The Germans, however, were in the midst of another command and control reorganization that was to cause some confusion during the ensuing battle. On 17 October, XLVII Panzer Corps headquarters was scheduled to be replaced by the LXXXIX Corps under Lt. Gen. Werner Freiherr von und zu Gilsa and responsibility for the corps zone would be transferred to the Nineteenth Army.4 While the panzer corps was leaving for the Army Group B front, von Gilsa arrived on the 17th, but with only his chief of staff and little else; it would be 23 October before his corps staff was assembled and fully operational.

Additional strength available to the Nineteenth Army included four fortress infantry regiments and twenty fortress battalions (infantry, machine gun, or artillery). By 15 October three of the four fortress infantry regiments were fully committed to the front lines, as were all but one or two of the fortress battalions; most were in the process of being absorbed into the regular infantry divisions. Thus, according to the German system of accounting, von Gilsa’s LXXXIX Corps had perhaps 22,000 combat effectives, and the LXIV Corps, under General Thumm, had as many as 18,000. Although the bulk of these troops could be considered adequate for defensive purposes only, the figures contrasted sharply with Seventh Army G-2 estimates in October, which gave the LXXXIX Corps only 5,200 combat effectives and the LXIV Corps no more than 3,000. The low American figures probably reflected the inability of Allied intelligence to track the German fortress (Weststellung) units and their incorporation into the line infantry divisions. During the entire month of October, for example, the Seventh Army G-2 could account for only six of the nineteen fortress battalions that the Germans committed to forward defensive roles, and by the end of the month the G-2 assessments allowed for only one of the three Wehrkreis V fortress infantry regiments also deployed to the front.5

Beyond the Weststellung units, General Wiese of Nineteenth Army could expect few reinforcements to feed into the front lines or to form any reserve. Scheduled arrivals for the last half of October included the 201st and 202nd Mountain Battalions, light infantry units of about 1,000 men each.6 Wiese was also to receive an understrength infantry battalion consisting of troops on probation from courts-martial and a similar unit made up of men suffering or recovering from ear ailments.

The Nineteenth Army’s main armored reserve in mid-October was the 106th Panzer Brigade, actually little more than a reduced tank battalion reinforced with supporting combat and service units that rendered the “brigade” somewhat self-sufficient. On 15 October the 106th was stationed in the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps’ sector south of the LXIV Corps. Also in reserve was the 1st Battalion, 130th Panzer Regiment, located near Corcieux, in the LXIV Corps’ sector, about eight miles east of Bruyères.7

The Nineteenth Army’s artillery was in better shape. The supply of artillery and mortar ammunition had increased considerably, and the transfer of fortress artillery battalions to front-line support helped to augment defensive fires. Shorter and more stabilized lines of communication, developing as the Germans grudgingly fell back to the east, further eased ammunition supply problems, while inclement weather aided German efforts to move ammunition and troops on highways and railroads during daylight hours by limiting Allied air interdiction strikes. In addition, Allied artillery ammunition shortages restricted the amount of fire used to harass German supply operations, especially in the VI Corps area where Truscott was trying to build up his stocks for direct combat support missions. Finally each German division in front of the VI Corps had been reinforced by an antiaircraft battalion, the batteries of which were generally positioned at critical points, readily available for ground support roles.

The missions and tactics of Nineteenth Army remained unaltered. General Balck of Army Group G still insisted that Wiese’s units hold well forward of the main Weststellung positions and counterattack all Allied penetrations of their forward defensive lines. Rejecting the argument that an immediate withdrawal to the Weststellung would conserve both men and matériel, Balck still hoped that his delaying tactics would gain the time needed to complete the Weststellung fortifications and to man the defenses with newly organized fortress units from Germany. The transferral of so many fortress units to the Nineteenth Army’s forward defenses and the continual delays in the various Weststellung construction projects because of poor weather and labor shortages only increased his determination to make a stand well forward of the Vosges Foothill Position, the Weststellung’s first line of defense on the east bank of the Meurthe River.8

West of the Vosges Foothill Position, the Germans constructed only hasty field fortifications. However, from bitter experience VI Corps troops knew that the so-called hasty defenses they would encounter in the heavily forested high ground lying north and south of Route 420 could be formidable. All roads and trails would be

blocked by tangles of felled trees, and most barriers would be booby-trapped, mined, covered by machine-gun fire, or carefully targeted by German mortars and artillery. Numerous infantry strongpoints, often well concealed, covered by tree trunks, and supported by artillery and antitank weapons, would have to be laboriously eliminated one by one. All but the best-paved roads would break up under heavy military traffic, and wet weather would quickly turn lesser roads and mountain trails into quagmires. Elaborate minefields could be expected on critical open ground, and randomly sown mines and booby traps along roads and trails. Tree bursts from German artillery had proved especially troublesome in such terrain, and the VI Corps’ infantrymen would also encounter increasing amounts of barbed-wire entanglements wherever they went.

The Preliminary Attacks

Elements of the 45th Division’s 180th Infantry began the offensive early. On 14 October the regiment cleared the last Germans from battered Hill 385 overlooking the Mortagne valley and, with its rear secured, began advancing toward Brouvelieures; the 179th Infantry joined the effort on the following day. For the next four days the two regiments slowly pushed back into the wooded ridges and hills that they had abandoned after the German counterattack of 6 October, confirming that the 16th Volksgrenadier Division had made good use of the intervening days to improve old defenses and construct new ones.

Progress against determined resistance was slow but steady. On 19 October General Eagles reinforced the 179th Infantry with a battalion of the 157th from Rambervillers, and by the 21st, after repeated attacks, the units found German resistance in the area beginning to collapse. By 1540 that afternoon the 179th Infantry had troops in Brouvelieures, where house-to-house fighting continued until dark, while advance units of the 3rd Division came up from the south to secure an intact bridge over the Mortagne a mile north of Brouvelieures. The following day, 22 October, the 179th and 180th Infantry regiments mopped up west of the Mortagne; however, elements of the 180th, attempting to seize another bridge, had to fall back west of the river in the face of heavy German fire, and the defenders quickly destroyed the span. Although successful in occupying Brouvelieures, Eagles wondered if his division would still have to fight its way north over the Mortagne River to secure the assembly areas for Truscott.

The slow advance of the 45th Division was balanced by the surprisingly rapid progress of Dahlquist’s 36th Division on the corps’ right wing. Although fighting across well-defended forested ridges and hills, staving off numerous small German counterattacks, and subject to heavy German artillery and mortar fire, the fresh 442nd Infantry had cleared the hills immediately west and north of Bruyères late in the afternoon of 18 October, unhinging the German defenses at Bruyères and forcing the 716th Division’s right wing to withdraw. South of Bruyères, Laval fell to

Japanese-American Infantry (442nd RCT) in hills around Bruyères.

the 143rd Infantry on 15 October, and the regiment had secured several crossings over the Vologne River by the 17th. On 18 October the 143rd began pushing into Bruyères from the south, while the 442nd probed into the city from the north and west; patrols from the two units began to run into one another early that evening. The next day the 143rd Infantry took over the burden of clearing artillery-shattered Bruyères, while the 442nd secured the heights east of the town and began advancing farther north toward Belmont and the Domaniale de Champ forest.

The 3rd Division Attacks

The slow progress of the 45th Division and the success of the 36th resulted in Truscott’s modifying his plans for the main attack. By noon of 19 October he realized that a dangerous gap was growing between the two attacking divisions because of their disparate rates of advance. But he also believed that adhering to his original plan and holding the 36th Division in the Bruyères area to wait for the 45th to cross the Mortagne River would only destroy the momentum of the 36th’s attack and give the Germans time to reform their crumbling defenses. Accordingly, on 19 October, Truscott asked General O’Daniel if one of the 3rd Division’s waiting regiments, either the 7th or 15th, could move into the line between the 36th and 45th Divisions on 20 October

from the regimental assembly areas near Remiremont. With O’Daniel’s assurance that at least one and possibly both regiments could be ready by noon on the 20th, Truscott ordered the 3rd Division to begin its attack at once, passing through the Brouvelieures–Bruyères area and advancing northeast on Route N-420, while pushing into the wooded hills on both sides of the highway. When available, the 30th Infantry could be committed on the division’s left. The new plan, in effect, made the 3rd Division responsible for securing much of the 45th Division’s portion of the DOGFACE line of departure as well as for taking over the 45th Division’s mission to attack northeast along Route N-420. Nevertheless, it enabled Truscott to take advantage of the new tactical situation of the VI Corps and focused the combat power of O’Daniel’s 3rd Division on a narrower route of advance without any loss of momentum.

During the afternoon of 20 October the 3rd Division’s 7th Infantry secured a key road junction about midway between Bruyères and Brouvelieures and cleared a steep-sided hill mass immediately east of the crossroads. Late in the day the 15th Infantry assembled near the junction, and both regiments began preparations for a major push north up Route N-420 the following morning. To all intents and purposes, the DOGFACE operation itself would commence three days earlier than Truscott had planned.

The progress of the 3rd Division was rapid. By the 22nd the attacking regiments were approaching Les Rouges Eaux, about halfway to St. Die, forcing remnants of the 16th Volksgrenadier Division back into the forests on either side of the road. At the same time the success of the 3rd Division made conditions easier for the 36th, which was operating east of N-420. On 22 October the 36th Division’s Felber Force, an ad hoc armored task force commanded by Lt. Col. Joseph G. Felber,9 secured Belmont; meanwhile, the 442nd and 143rd regiments fought their way across the southern sector of the Domaniale de Champ forest through elements of the 716th Division, halting only after reaching the high wooded ground above the Neune River valley just short of Biffontaine.10 In doing so, the 36th Division had accomplished its part of the initial DOGFACE objectives and, as a bonus, had driven a wedge between the LXXXIX Corps’ 16th Volksgrenadier Division and the LXIV Corps’ 716th Division.

The successes of both the 3rd and 36th Divisions were the product of Truscott’s rapid change of plans. In addition, the deception operations of the VI Corps and the French II Corps had succeeded admirably in keeping German attention focused on the Gerardmer sector of the Vosges front. Not until the morning of 23 October did the Nineteenth Army learn of the 3rd Division’s redeployment to the VI

Corps’ center, but by then Truscott’s forces had driven a deep salient into the German forward defenses in the Bruyères sector, and the resulting confusion in the German front lines made it even more difficult to move local reinforcements to the threatened area. On the evening of 22 October, Truscott was thus justified in feeling that once again the German forces across his front were on the verge of complete collapse.

However encouraging, the developing situation forced Truscott to make further revisions in his DOGFACE plans on the 22nd.11 On his left, or northern, flank, the 45th Division was preparing to cross the Mortagne River in strength north of Brouvelieures that night. In the center, the 3rd Division’s surprise attack had exceeded expectations, and its two attacking regiments were well on their way to St. Die. On the right, the 36th Division had two regiments in sight of the Biffontaine objective line; in accordance with the basic DOGFACE concept, both units were ready to move on to clear the northern and eastern sections of the Domaniale de Champ.

For the moment, Truscott decided to leave the corps’ current dispositions unchanged. With the 3rd Division now making the main effort via N-420, he directed the 45th Division to clear the Rambervillers forest area, advancing first across the Mortagne River and then pushing north, using Route D-32 as a phase line. The 45th Division’s 157th regiment would join the effort from Rambervillers, and the final objectives of the division would take it to Routes N-59, N-59A, Raon-l’Etape, and the Meurthe River valley. The 36th Engineer Combat Regiment12 and the 117th Cavalry Squadron, both under direct corps control, would guard the 45th Division’s left flank and maintain contact with the XV Corps’ French 2nd Armored Division north of Rambervillers.

In the VI Corps center the 3rd Division’s immediate mission was to seize the road junction town of Les Rouges Eaux on Route N-420. Once this town was secured, O’Daniel wanted one of his regiments to advance northeast toward La Bourgonce, taking the high ground on the north side of Route N-420; meanwhile, the rest of the division would push east down both sides of the road, securing it as the corps’ main supply route and occupying the high ground in the Magdeleine woods, overlooking St. Die. The division’s ultimate objective was a three-mile stretch of the west bank of the Meurthe just north of St. Die, but not the city itself, the larger part of which lay on the opposite side of the river.

Truscott’s new plans also envisioned more extensive objectives for the 36th Division. On the left the 442nd Infantry was to clear the northern part of the Domaniale de Champ forest and then assemble in reserve at Belmont. In the division’s center, the 143rd regiment

was to hold in place while the 141st continued the attack, pushing through the eastern section of the Domaniale de Champ and securing the high ground that overlooked La Houssière. The regiment’s final objective was the forested hills just west of St. Leonard, a railroad town on Route N-415 about five miles farther east of La Houssière and a similar distance south of St. Die. Once in reserve, the 442nd would assist the 141st as necessary. On the division’s (and the corps’) right flank, the 143rd and 142nd Regimental Combat Teams, north to south, would defend the area from Biffontaine south to the vicinity of Le Tholy; ultimately they would relieve the 3rd Division’s 30th regiment still in the Le Tholy area and mesh with the French II Corps’ 3rd Algerian Division.

Truscott, however, would never see his revised DOGFACE plans executed. Destined for a higher level command in the Italian theater, he turned over the VI Corps to Maj. Gen. Edward H. Brooks at noon on 25 October and left the Vosges front.13 The Seventh Army had lost its hard-charging corps commander, who had in many ways dominated the Allied campaign in southern France from the Riviera beaches to the Vosges Mountains. For over two months he had feverishly kept his three American infantry divisions on the move, forever harassing the retreating Germans and allowing them little time to rest and reorganize. His new offensive was yet another attempt to destroy the German defenses before they could solidify—an attempt that, like those before, was to be undertaken in the face of severe Allied logistical difficulties. However, the effort was also marked by much tactical and operational imagination, such as the secret massing of the 3rd Division in the corps’ rear. Lucian Truscott would be missed in northern France. Nevertheless, the new phase of the DOGFACE attack would begin almost immediately under the direction of General Brooks.14