Chapter 21: Through the Saverne Gap

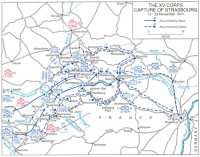

As D-day for the November offensive of the XV Corps approached, Haislip readied his three divisions, now constituting the smallest Allied attacking force. His left wing was still anchored on the Rhine–Marne Canal at Xures, about three miles across from the opposing flank of the German LXIV Corps at Lagarde. The XV Corps’ 106th Cavalry Group screened the corps’ left for two miles, maintaining contact with the Third Army’s XII Corps north of the canal. The 44th Infantry Division held the next seven miles south to the Vezouse River near Domjevin, now in Allied hands. The French 2nd Armored Division, its front bulging eastward, covered the ground from the Vezouse south another eight miles to Baccarat, on the boundary between the XV and VI Corps. The 79th Infantry Division, out of the line since 24 October and resting south of Lunéville, was to play a major role in the forthcoming attack. To strengthen these forces Patch had decided to give Haislip the VI Corps’ 45th Division as soon as it had completed its rest after DOGFACE. Thus, although small in numbers, the XV Corps could marshal some of the most experienced units on the entire Allied front for the assault against the narrow Saverne Gap, now defended only by three weak Volksgrenadier divisions.

XV Corps Plans

General Haislip, commanding XV Corps, set forth the requirements for his November offensive in succinct terms: capture and secure Sarrebourg; force the Saverne Gap; and prepare to exploit east of the Vosges.1 With the cavalry force covering along the Rhine–Marne Canal, the 44th Division was to make the main effort initially, heading northeast twenty miles to seize Sarrebourg from the west and north. The 79th Division, coming back into the line south of the Vezouse River, would pass through the 2nd Armored Division and head northeast to invest Sarrebourg from the south and east. Both divisions were to be ready to continue the offensive northeast and east after securing Sarrebourg. During this time the French 2nd Armored Division would remain in reserve as the XV Corps’ exploitation force. When the infantry divisions began breaking through the German defenses, Haislip planned to send the armored unit through the infantry, striking for the Saverne Gap and securing a bridgehead through the Vosges somewhere in the Saverne

Generals Spragins, Haislip, and Wyche at XV Corps Command Post, Lunéville, October 1944.

area. The timing of the armored division’s attack would be critical.

The designations Saverne and Saverne Gap require some explanation. The small, busy, but pleasant city of Saverne lies under the eastern slopes of the Vosges and at the western edge of the Alsatian plains. Through the city passes Route N-4, the Paris–Strasbourg highway; the main railroad line to Strasbourg; and the Rhine–Marne Canal and its contributory stream, the little Zorn River. Another rail line leads off to the northeast, while lesser highways and secondary roads come in from the north, south, and east.

The easiest approach to Saverne from the west is along Route N-4, which passes through Phalsbourg, on the edge of the Lorraine plateau, and winds down the wooded eastern slopes of the Vosges in a gradual southeasterly descent. However, the Saverne Gap proper lies farther south, originating in the west at Arzviller, five miles east of Sarrebourg, and emerging at the southwestern approaches to Saverne itself. The gap, an almost gorge-like passage through the Vosges, is scarcely 100 yards wide at places, but accommodates the main railroad line to Strasbourg, the Rhine–Marne Canal, the upper reaches of the Zorn River (merging with the canal through much of the gap), and a narrow secondary highway. The railroad passes through a number of tunnels (one, near Arzviller, a mile

Saverne

and a half long); the canal drops 500 feet between Arzviller and Saverne through a series of locks; and the road hugs the base of the forested, towering hills through much of its journey.

Haislip estimated that XV Corps would encounter no strong, continuous defensive lines, but instead would run up against delaying forces at strongpoints at key road and canal junctures—a judgment that corresponded closely with LXIV Corps’ capabilities.2 His units would have to force their way through elements of at least three Volksgrenadier divisions: part of the 361st under von Gilsa’s LXXXIX Corps (First Army) north of the canal and all of the 553rd and perhaps half of the 708th under Thumm’s LXIV Corps south of the waterway (Nineteenth Army). Since neither of the opposing corps had any mobile reserves, Haislip expected that the defenses would be spotty, but in great depth; therefore, he instructed his division commanders to have their leading units bypass isolated strongpoints, leaving them for follow-up forces. Should the van units became entangled in such defenses, he wanted the second echelons of the attacking

forces to bypass the action and maintain the forward momentum.

XV Corps Attacks

After the French 2nd Armored Division’s seizure of Baccarat and after some minor 44th Division advances during the first week of November, little change had taken place along the XV Corps’ front until the night of 11–12 November. Then, under cover of darkness, the 79th Division began moving into forward assembly lines in the Mondon forest south of the Vezouse River (Map 26). Heavy rains had gradually turned into blizzards during the days preceding the attack, and by evening of the 12th wet snow blanketed the entire corps sector. All streams in the area were flooded, many roads and bridges were under water, and the troops described the now ever-present French mud as bottomless.3 In fact, the weather had been so poor that General Devers contemplated postponing Haislip’s attack; but about 2300 that night he decided to proceed with the offensive, hoping that the Germans might not expect a major attack under such adverse conditions.4 The 44th and 79th Divisions, each with two regiments abreast, jumped off on schedule early the following morning of 13 November.

Behind an intensive artillery preparation, the 44th Division attacked along the axis of the railroad line to Sarrebourg, with the 324th Infantry on the left and the 71st Infantry on the right. At first both regiments advanced rapidly, but by 0800 the Germans had recovered from the bombardment and responded with heavy and accurate artillery, mortar, and machine-gun fire all across the division’s front. By dark, disappointing gains had carried the leading battalions hardly a mile eastward, and the high point of the day was the capture of battered Leintrey, a small town at the junction of three secondary roads. Operations on 14 November were even less productive, and General Spragins, the division commander, decided to commit his reserves, the 114th Infantry, in the Leintrey area. After passing through the 71st Infantry on the south, the 114th was to swing north across the fronts of the other two regiments, sweeping through the defenses of the 553rd Volksgrenadier Division from the flank and rear.

This somewhat unorthodox—if not dangerous—maneuver proved successful; by the evening of the 15th, the 114th Infantry had gained a mile and a half to the east, northeast, and north of Leintrey, thus dislocating the German defenses in the rising, partially wooded ground. On 16 November the 114th Infantry and the 106th Cavalry Group mopped up on the division’s left, and the next day the 324th and 71st Infantry continued their advance east, passing through the wake of the 114th, which reverted to its reserve status.

By 18 November the defenses of the 553rd Volksgrenadier Division began to unravel in the face of the continuing attack. During the following day

Map 26: The XV Corps Capture of Strasbourg, 13–23 November 1944

the 71st Infantry undertook the division’s main effort and pushed some nine miles along the axis of Route N-4, coming almost within sight of the Rhine–Marne Canal, about six miles short of the division’s objective, Sarrebourg. To the north, the 324th, now in support of the 71st, kept pace, as did elements of the 106th Cavalry stretching eastward along the canal. The 44th Division had achieved at least half of the breakthrough that Haislip had hoped for.

South of the 44th Division, General Wyche’s 79th Division began its attack on 13 November from a line of departure near Montigny, at the junction of Routes N-392 and N-435. By the following day the 314th Infantry on the left had reached Halloville, while the 315th on the right pushed several miles up Route N-392 toward Badonviller. The Halloville thrust threatened to drive a wedge between the 553rd and 708th Volksgrenadier Divisions and was clearly the most dangerous penetration. As the 708th prepared a strong counterattack, the 315th Infantry, moving up to support its sister unit, struck first and sent an infantry force backed by tanks and tank destroyers into the German assembly area east of Halloville, which dispersed the German reserves and, in the process, destroyed most of the 708th’s assault guns.5

On the 15th the Germans made two more attempts to restore the situation in the Halloville sector. First, elements of the 553rd Volksgrenadier Division struck south from Blamont, along Route N-4 and the Vezouse River about three miles north of Halloville. Then another force, probably under the direct control of the LXIV Corps, moved up from the southeast. So ineffectual were these efforts that the 79th Division’s forward units reported no unusual activity. Thus, as the 44th Division began to dislocate the 553rd Division’s defenses in the north, the 79th Division now began to penetrate the lines of the 708th Division at will, walking nearly unopposed into Harbouey, two miles northeast of Halloville, and continuing its advance toward the southern approaches to Sarrebourg.

At the headquarters of both the Nineteenth Army and the LXIV Corps, the situation began to appear desperate as early as 16 November. Lacking any radio or telephone communications with the 708th Volksgrenadier Division, the German commanders believed that the converging Allied attacks along Route N-4 had pushed back the 708th’s right flank, thus cutting off the 553rd Volksgrenadier Division from the rest of the corps. Actually the situation was not yet that bleak. During the night of 15–16 November, the left of the 553rd had fallen back in fairly good order to Blamont and reestablished a defensive line on the Vezouse to Cirey-sur-Vezouse. About the same time, the rather disorganized right wing of the 708th Volksgrenadiers began moving into line south from Cirey along rising, forested terrain dotted with installations of the Vosges Foothill Position. Nevertheless, the condition of LXIV Corps’ defenses was rapidly becoming a serious problem.

On 16 November Haislip began to commit elements of the 2nd Armored Division in order to secure the flanks of both attacking divisions and to ensure that the momentum of the offensive continued. Combat Command Remy (CCR) began to push southeast from Halloville along secondary roads, clearing roadblocks and mines and generally disorganizing the 708th Division’s lines of communication. On the 17th CCV reinforced Remy, striking east about five miles along Route N-392 from Montigny to seize Badonviller and then swinging north two miles to Bremenil. Meanwhile, to the north, elements of CCL (de Langlade) began moving up to Blamont along Route N-4, as 79th Division infantry forces crossed the Vezouse River to the east, in the face of still strong opposition from the 553rd Volksgrenadier Division, and began to invest the town from the north.

On 18 November, as the 44th Division started its deep penetration of the 553rd Volksgrenadiers’ front along Route N-4, the right of the 708th Volksgrenadier Division collapsed, as Wiese had feared. CCR and elements of CCV subsequently rolled northward for four unopposed miles to capture bridges at Cirey-sur-Vezouse. The Badonviller–Cirey road had been a main supply route of the German defenders, and the French found it clear of roadblocks and mines. On the same day, the left of the 79th Division walked unopposed into Blamont. Although German artillery and mortar fire halted further progress north of the Vezouse, the effect was only temporary.

During the night of 18–19 November, the left wing of the 553rd Volksgrendier Division withdrew in a vain attempt to establish a new defensive line from Richeval, five miles northeast of Blamont, south and east through Tanconville to Bertrambois and Lafrimbolle. The American and French attackers never gave the 553rd time to pause. By noon on the 19th, the 79th Division’s 314th regiment was approaching Richeval; the 315th had passed through Tanconville; CCL had cleared Bertrambois; and CCR units had reached out to Lafrimbolle in the mountains, a mile and a half east of Bertrambois. Haislip was now ready to begin the exploitation phase of his attack, and at 1345 that afternoon he turned the rest of Leclerc’s 2nd Armored Division loose.

The Exploitation Plan

Leclerc’s immediate objective was Saverne, on the far side of the Vosges Mountains. Toward this end he had divided his division into carefully organized task forces, and he assigned to each complementary but independent missions, including primary and alternate routes of penetration.6 To support the division’s scheme of maneuver, his staff had also put together every available scrap of information about road conditions, German deployments, and German defenses. Leclerc planned to lead off with two combat commands, CCD (Dio) and CCL, each subdivided into two smaller task forces. After crossing the Rhine–Marne Canal, CCD units were to bypass Sarrebourg to the west and north, head east across the Low

Vosges well north of the Saverne Gap in two columns, and then, once on the other side of the mountains, descend on Saverne from the north and northeast. South of the canal and south and east of Sarrebourg, CCL, also with two columns, was to push rapidly east over second-class roads, crossing the Vosges well south of the Saverne Gap; push through the heavily forested mountains to the Alsatian plains; and then swing north to meet CCD. CCV would be in general reserve, ready to reinforce either CCD or CCL, while CCR, the armored division’s permanent reconnaissance organization, would support CCL in the south and secure the division’s extended right flank. If Leclerc’s intelligence estimate was correct, the plan would allow him to avoid the strong defenses that he expected in the Saverne Gap itself and cut through the mountain passes before the Germans had a chance to block them.

Haislip’s larger objectives also required that Leclerc’s armor secure all eastern exits of the Vosges passes from La Petite-Pierre, eight miles north of Saverne, to Dabo, about eight miles south of the gap. To assist, Haislip wanted the 44th Division to seize Sarrebourg as soon as possible and be prepared to relieve French armor along the northern portion of the corps’ objective area. In addition, the 79th Division, now relieved of its Sarrebourg mission, would be ready to exploit the French gains in the southern half of the corps’ sector and secure the southern portion of the objective area. Upon relief by the 44th and 79th Divisions, Leclerc was to push his entire armored division on to Haguenau, an important highway and rail junction on the Alsatian plains, seventeen miles north of Strasbourg. If necessary, however, the French armor was also prepared to withdraw all the way back to Weyer, on the west side of the Vosges ten miles north of Sarrebourg, in order to protect XV Corps’ exposed northern flank.7

The so-called Weyer alternative demonstrated that Patch and Haislip were fully aware of the risks involved in a deep penetration by the French armored division. By 19 November the XV Corps’ left flank was more than ten miles beyond the right wing of the Third Army’s XII Corps, which was still back in the area just above Lagarde. Although currently screened by the XV Corps’ 106th Cavalry Group, the gap could only grow larger as Haislip’s forces drove east.8 A similar situation existed in the south, where the lengthening boundary with Brooks’ VI Corps at Baccarat was screened by CCR. Both Patch and Haislip felt, however, that the possibility of a German counterattack was minimal. The two opposing Volksgrenadier divisions were falling apart, and the German forces on both of their flanks were too concerned with their own immediate fronts to assist the 553rd or 708th. North of the Rhine–Marne Canal, the First Army’s southernmost unit, LXXXIX Corps’ 361st Volksgrenadier Division, was fully committed to the defense of its own

sector against the attacking U.S. XII Corps. South of the XV Corps, the rest of the LXIV Corps had its hands full defending against Brooks’ VI Corps attack, now in full swing. Only by bringing substantial reinforcements forward from outside the Nineteenth Army’s zone could the Germans develop any serious threat to either of the XV Corps’ extended flanks, and this danger seemed remote. Such a counterattack would take time to assemble and deploy, and Haislip still had the 45th Infantry Division in reserve for such contingencies. Nevertheless, the Weyer alternative put Leclerc on notice that his forces might have to return west of the Vosges should a threat develop.9

Seizing the Gap

During the afternoon of 19 November CCD assembled south of the forward positions of the 44th Division near Heming, at the juncture of N-4 and the Rhine–Marne Canal. Before dawn on the 20th, Allied troops had secured several bridges over the canal, and at daylight the armored attack began. Initially the 44th Division’s 71st Infantry moved northeast along Route N-4 directly toward Sarrebourg. Meanwhile, CCD and the 324th Infantry, following all passable roads, crossed the canal and headed north, delayed only by scattered elements of the LXXXIX Corps’ 361st Volksgrenadier Division, which for the most part lacked any artillery support.

The 361st Volksgrenadiers were in a difficult position. During the night of 19–20 November, under pressure from the XII Corps, the division had begun withdrawing into Weststellung positions north of Heming, only to lose the southern portion of its new line to Haislip’s XV Corps before the withdrawal could be completed. Now the division had to pull itself even farther back in an attempt to keep Sarrebourg from falling into the hands of Allied forces advancing up Route N-4 from the southwest. To assist in the effort, Balck, the Army Group G commander, transferred the remnants of the 553rd Volksgrenadier Division from the Nineteenth Army’s LXIV Corps to the First Army’s LXXXIX Corps; and von Gilsa, the corps commander, ordered the 361st Division to assemble a regimental task force to reinforce the 553rd south of the canal. During the night of 19 November von Gilsa also moved the headquarters of the LXXXIX Corps to Sarrebourg, only to be forced to evacuate the city hurriedly on the afternoon of the 20th as the 71st Infantry approached. There was little he could do to salvage the position. By dark the 71st Infantry had secured most of the city, and other 44th Division units had overrun about half of the reinforcements sent to the area by the 361st Volksgrenadier Division.

As these developments were taking place, CCD had continued to move north of the German lines, dividing itself into two armored columns. The southern arm, Task Force Quilichini, reached the Sarre River at Sarraltroff, over two miles north of Sarrebourg.

Meanwhile, the northern column, Task Force Rouvillois, captured a bridge over the river at Oberstinzel, two miles farther north, and by dark had sent patrols to Rauwiller, over three miles to the east.

The French incursions abruptly forced the 361st Volksgrenadiers backward along a new defensive line between Mittersheim, Rauwiller, and Schalbach, facing generally southward to protect the LXXXIX Corps’ rear lines of communication. Whittled down to less than 2,000 infantry effectives, however, the hapless 361st had little chance of holding either this new line or its main defensive positions still facing west against Third Army units.

Accurately assessing the German situation, Col. Louis J. Dio, commanding CCD, obtained Leclerc’s permission to have TF Rouvillois cross the Vosges through a route farther north than the one planned, both to take advantage of German weaknesses in the area and to further dislocate any German defenses in the Vosges or in the open country north of Sarrebourg. Striking out early on the morning of 21 November, TF Rouvillois was soon past Schalbach and then swung northeast for about three miles to Siewiller, at the western edge of the Low Vosges. Crossing a main north-south artery, Route N-61, the force pushed on and by late afternoon was at La Petite-Pierre, in the heart of the Low Vosges some ten twisting road miles beyond Siewiller. Behind TF Rouvillois, the XV Corps’ 106th Cavalry Group probed northward, securing Baerendorf, Eywiller, Weyer, and Drulingen on the corps’ northern flank. Nowhere did the cavalry encounter any threat to CCD’s rear.

CCD’s second column, TF Quilichini, had meanwhile headed almost due east, rapidly covering the eight miles from Sarraltroff to Mittelbronn along Route D-36. After a brief clash with undermanned German defenses at Mittelbronn, the advance halted, for patrols had discovered formidable, well-defended antitank obstacles across N-4 in front of Phalsbourg, a mile or so to the east. To the rear, the 44th Division’s 324th Infantry crossed the Sarre River at Sarraltroff behind TF Quilichini, and the 114th Infantry, coming out of reserve, reached out along Route N-4, two miles beyond Sarrebourg. South of Sarrebourg, units of the 79th Division now made an appearance, bypassing a CCL fight along the way and moving up to the main highway, Route N-4. The American infantry divisions along with some of the French armored units were thus rapidly converging on Phalsbourg and the immediate western approaches to the Saverne Gap.

South of Sarrebourg, CCL’s northern column, Task Force Minjonnet, had left Bertrambois on the morning of the 19th and, following a third-class country road, pushed north two miles through dense forests to be halted just south of Niederhoff. The southern column, TF Massu, also made little initial progress against 553rd Volksgrenadier defenses north of Lafrimbolle, but the thinly dispersed 553rd could not hold out long. Increasingly disorganized and out of communication with its corps headquarters, the division tried to establish a new defensive line during the night of 19–20 November between

Heming, on the Rhine–Marne Canal, south and southeast along the Sarre Rouge and Sarre Blanche rivers to St. Quirin, deep in the Vosges.10

On 20 November the French advance in the south continued. After some brief fighting during the morning, TF Minjonnet’s armor cleared Niederhoff and then swung northeast along back roads for about two miles, crossing the Sarre Rouge and forcing its way eastward another two miles to Voyer. Here it overran 553rd Division artillery positions and captured some 200 German troops. Minjonnet’s flank and rear security were assured later in the day when the 314th Infantry also fought its way across the Sarre Rouge and the 313th Infantry moved up to Niederhoff.

Farther south, TF Massu spent much of the morning outflanking and breaking through last-ditch positions of the 553rd along the Sarre Blanche west of St. Quirin, which fell about 1400 on the 20th, thus marking the complete collapse of the 553rd Volksgrenadier Division’s defensive effort. Massu then sped his armor along the twisting mountain roads to Walscheid, five miles—straight line distance—northeast of St. Quirin, and continued north another three miles to pick up Route D-114, also known as the Dabo Road, which ran uphill to the southeast for eight miles through wild, forested country to the Wolfsberg Pass.

Prisoners, mostly from artillery and service units, now began to create a problem, especially for CCL task forces south of Saverne. As a remedy, the XV Corps directed the 79th Division to attach two rifle companies to the French 2nd Armored Division to help handle the increasing number of surrendering Germans. About the same time, General Leclerc decided that opposition during the day warranted committing his CCV reserve in the southern sector. CCV’s main effort was to be made along the Dabo Road, with TF Massu passing to its control. Task Force Minjonnet of CCL would continue north and northeast from Voyer to Arzviller, but was to double back and follow CCV through the mountains if strong opposition was encountered. CCR, which had been maintaining roadblocks along the XV Corps’ right, or southern, flank, would reassemble at Walscheid, ready to secure the Dabo Road behind CCV.11

Amid a heavy rainstorm TF Massu, overrunning small groups of fleeing Germans, continued southeast up the Dabo Road. That evening, about 2000 on the 20th, forward elements of the task force reached the village of Dabo, three road miles short of the Wolfsberg Pass, where they halted to refuel and await the arrival of CCV. The latter force, moving out of an assembly area near Cirey-sur-Vezouse, had traveled east as rapidly as rain and road conditions permitted and, after dark, continued on with all vehicle headlights ablaze to catch up with Massu’s forces near Dabo at 0200 on the 21st.

Although the Dabo Road could have been easily interdicted, the 553rd Volksgrenadiers were no longer interested. What was left of the division was surrounded and sought only to escape from the advancing Allied forces. Maj. Gen. Hans Bruhn, the division commander, assembled about 1,800 troops, some light artillery pieces, and all operable vehicles in an area just north of Voyer. Aided by a heavy downpour, Bruhn’s group hugged the Rhine–Marne Canal and passed by several Allied outposts in the night, probably units of the 314th Infantry, to reach Arzviller before dawn on the 21st. Another force of some 300 553rd Volksgrenadier Division troops farther east somehow sidled past French units along the mountain roads and also reached Arzviller during the morning of 21 November. With these two groups and miscellaneous other troops already in the area, Bruhn began to organize the defenses of the Saverne Gap proper, attempting to tie in his forces with the existing defenses at Phalsbourg. There the German defenders had received an unexpected bonus, a well-equipped battalion of troops from an NCO school at Bitche, some twenty miles north of Saverne. The defenses were thus in much better condition.

Prior to the XV Corps’ attack, Bruhn had made provisions for a last-ditch defense of the most obvious approaches to Saverne, down Route N-4 and through the gorge of the Saverne Gap, but had neglected to prepare blocking positions along the narrow mountain roads north and south of Saverne, as Leclerc had surmised. The 553rd was now too weak to remedy the mistake, and the units on both its flanks were unable to fill in. In the north the left wing of the 361st Volksgrenadier Division had almost disappeared, while in the south the rest of the 708th Volksgrenadier Division had been badly cut up by the VI Corps’ 100th Division at Raon-l’Etape. In fact, between Arzviller and Bertrambois—the new northern boundary of the Nineteenth Army—a gap of about ten miles existed with no organized defense.

Starting out at dawn on 21 November, TF Massu, followed by CCV, reached the Wolfsberg Pass by noon despite spotty, but determined resistance. Two hours later its leading elements, moving as fast as possible down the steep sides of the eastern Vosges, broke through to the Alsatian plains. Massu immediately turned north, heading for Saverne, while CCV moved east, spreading out over the broad rolling terrain. Meanwhile, TF Minjonnet battled most of the day with scattered elements of the 553rd Volksgrenadiers a mile south of Arzviller; only after dark did it reverse its course and cross the Vosges via the Dabo Road, leaving the Arzviller area to the 79th Division’s infantry units. During the night the German forces in the area began withdrawing into the Saverne Gap gorge for a final stand.

By 22 November, the French 2nd Armored Division’s penetration of the Vosges was complete. In the north, TF Rouvillois of CCD broke out of the Low Vosges at Wieterswiller, four miles east of La Petite-Pierre and, after overrunning scattered German rear units, sped south seven miles across open farmland to Monswiller, just over a mile north of Saverne,

where they met elements of Massu’s force. TF Massu had entered the town of Saverne earlier and, without much of a fight, had captured over 800 Germans, including General Bruhn of the 553rd Volksgrenadiers, as well as part of the LXXXIX Corps headquarters. General von Gilsa, the LXXXIX Corps commander, escaped, at least from the Allies. Dissatisfied with his performance, Balck had replaced him with Lt. Gen. Gustav Hoehne, and von Gilsa had left Saverne that morning. But Hoehne, arriving as von Gilsa left, could do little except pull the bulk of the corps headquarters out of Saverne as quickly as possible and move it into the Saverne Gap gorge. Upon learning that Bruhn had been captured, the new corps commander took over what elements of the 553rd Division he could find and, during the night of 22–23 November, led them and his remaining corps staff northward along back roads through the Low Vosges to escape a second potential trap.

While CCL (TF Massu and TF Minjonnet recombined) and TF Rouvillois of CCD cleaned out Saverne and its environs on the 22nd, CCV secured more Alsatian towns and villages south and southeast of the city, meeting little German resistance. Later in the afternoon, TF Minjonnet moved northwest up Route N-4 from Saverne and by dusk, after having overrun many westward-facing German defenses, was about a mile short of Phalsbourg. Meanwhile, TF Quilichini, which had been operating north of the Sarrebourg–Phalsbourg area, west of the Vosges, crossed the mountains to rejoin the rest of CCD via the northern La Petite–Pierre route.12 By the end of the day only two tasks remained in order to finish securing the bridgehead that Haislip wanted into Alsace: opening the rest of Route N-4 from Phalsbourg to Saverne and clearing the Saverne Gap gorge.

West of the Vosges the 79th Division’s 314th regiment had moved up to Phalsbourg on the 22nd, and on the morning of 23 November the 314th and TF Minjonnet made short work of the remaining defenders. To the south, the 315th Infantry had entered the Saverne Gap gorge near Arzviller during the afternoon of the 22nd, and spent all of the 23rd pushing through scattered resistance from mines, roadblocks, and demolitions, finally reaching Saverne about noon on the 24th. The first phase of Haislip’s XV Corps offensive was complete.

The German Response

Both Field Marshal von Rundstedt at OB West and General Balck of Army Group G quickly realized that the Allied penetration opened a dangerous gap between the First and Nineteenth Armies.13 At the same time, pressure from the Third Army’s XII Corps prompted OB West to warn OKW about the possibility of another imminent breakthrough on First Army’s left wing. Taken together, the operations of both the XII and XV Corps could well foreshadow a major

disaster for the Germans, leading to the outflanking of the Saar basin on the south and east, the destruction of German military forces west of the Rhine, and ultimately an Allied crossing of the Rhine itself.

Von Rundstedt had already directed Army Group H, in the Netherlands, to dispatch the weak, rebuilding 256th Volksgrenadier Division to the front of the First Army. Now, on the 21st, he had Army Group H start another worn-out division, the 245th Volksgrenadiers, south to strengthen the First Army, and also released the four-battalion 401st Volks Artillery Corps to Army Group G for the same purpose. The First Army, in turn, reinforced the 361st Volksgrenadier Division with its last reserves, an understrength infantry assault battalion and the army headquarters guard company. The 361st Division, having failed to hold the Mittersheim–Schalbach line on 21 November, was to pull its left wing northward another three miles and hold a front between the towns of Mittersheim, Baerendorf, Weyer, and Drulingen, west to east.

On 22 November von Rundstedt gave Army Group G a provisional corps headquarters, Corps Command Vosges, to consolidate defensive preparation in the Strasbourg area. To slow Allied progress there, Corps Command Vosges was to establish a screening line from the Moder River south to Wasselonne, eight miles southeast of Saverne. However, to accomplish this mission, Army Group G could give Corps Command Vosges only a few insignificant elements: Feldkommandantur 987, the occupational area command located at Haguenau; the armed forces command of Strasbourg itself; the headquarters (only) of the 49th Infantry Division;14 two scratch infantry “battalions” (about 600 troops in all) from Wehrkreis VII; and a broad miscellany of smaller units that had begun streaming westward across the Rhine from Wehrkreis V and XII. Apparently, the 256th Volksgrenadier Division was also to pass to the control of Corps Command Vosges upon its arrival in the Haguenau area, beginning about 24 November.

Von Rundstedt realized that all these defensive arrangements were largely palliative and that only a strong counterattack held out any hope of preventing an Allied breakthrough of major proportions. For this purpose he needed armored reinforcements, and for days he had been importuning OKW to release the Panzer Lehr armored division to him.15 Currently refitting behind the battlefield, the Panzer Lehr, commanded by Maj. Gen. Fritz Bayerlein, had been earmarked for the Ardennes offensive, and OKW was reluctant to authorize its commitment.16 However, on the afternoon of the 21st, the German high command finally approved the use of the division, and by 1800 that evening the unit had started south. However, both Hitler and OKW specified that Panzer Lehr would have to return northward by 28 November.

Passing control of Panzer Lehr to Army

Group G, von Rundstedt admonished Balck to employ the division in its entirety for an attack deep into the northern flank of the XV Corps’ penetration in order to end the danger of a split between the two armies. The division was to assemble near Sarralbe, about nineteen miles north of Sarrebourg, and strike south to cut Route N-4 between Sarrebourg and Phalsbourg. Supporting the attack would be the 401st Volks Artillery Corps, the weakened 361st Volksgrenadier Division, and, Balck hoped, the understrength 25th Panzer Grenadier Division. Balck wanted the 361st and the 25th Panzer Grenadiers to protect the eastern flank of Panzer Lehr’s attack, blunting any Third Army (XII Corps) thrust toward Sarre-Union, fourteen miles north of Sarrebourg.

Balck also directed the Nineteenth Army to organize a task force to link up with the Panzer Lehr Division in the vicinity of Hazelbourg, on the western slopes of the High Vosges about six miles south of Phalsbourg. To release troops for this supporting attack, Balck authorized Wiese to pull most of his right-wing units back to the Vosges Ridge Position, including all units between the Blamont area and the Saales Pass, a distance of about twenty miles. This last order reflected Balck’s lack of information about the 553rd Volksgrenadier Division, which he thought was still holding steady in the Hazelbourg area, and about the 708th Volksgrenadier Division, which had also fallen apart. The possibility of adding a southern pincer to Bayerlein’s northern thrust was thus highly unlikely.

East of the Vosges, Balck intended to have the newly arrived 256th Volksgrenadier Division push south and west from Haguenau, expecting one regimental task force from the division to be available on the morning of 24 November and the rest of the division on the 26th. Finally, the Army Group G commander assumed that the 245th Volksgrenadier Division would arrive from Holland by 28 November, in time to help secure the ground that the Panzer Lehr had taken during its armored counterattack.

With unjustified optimism, Balck promised decisive results from the complicated and decentralized series of planned operations. However, his immediate subordinate, General Otto von Knobelsdorff, commanding the First Army, was less enthusiastic, believing that the Panzer Lehr would be fortunate to hold what little of the Sarre River valley region in Lorraine his forces still controlled.

Planning the Final Stage

Although hardly privy to all these German plans and preparations, Patch’s Seventh Army intelligence staff knew that something was brewing on the other side by the afternoon of the 22nd. Nevertheless, General Patch had already begun to revise his plans based on the current situation in both the XV and VI Corps zones.17 On 21 November he decided that the XV Corps was to direct its main effort after Saverne toward the capture of Haguenau and then Soufflenheim, eight miles farther

east of Haguenau and six miles short of the Rhine. Haislip was also to leave security forces in and west of the Vosges to protect his exposed northern flank and, in the south, to secure the Molsheim area, about fifteen miles south of Saverne.18 This latter action would project XV Corps forces into the rear of German units still holding up the advance of Brooks’ VI Corps in the High Vosges.

Finally, Patch ordered Haislip to “attack Strasbourg, employing armored elements to assist the VI Corps in the capture of the city.”19 Although technically Strasbourg was still a VI Corps objective, the city now appeared to be within easy reach of Haislip’s forces if they acted quickly. Since Brooks’ units were still fighting their way through the mountains, the new mission seemed appropriate. After the fall of Strasbourg, the XV Corps was then to reconnoiter northward along the Rhine to the Soufflenheim–Rastatt area, taking advantage of any opportunity to force a quick crossing. The VI Corps, in turn, would be prepared to cross the Rhine in its sector or, more likely, to exploit through a XV Corps bridgehead.

Issuing complementary orders during the morning of 22 November, Haislip went a step further in regard to Strasbourg. After cleaning up the Saverne area, Haislip ordered Leclerc’s 2nd Armored Division, previously assigned the seizure of Haguenau, to strike for Strasbourg and secure the city if it reached the area before the VI Corps. He then reassigned the Haguenau–Soumenheim mission to the 44th Division and tasked the 79th Division, also in the process of deploying east of the Vosges, to support either the 44th or the French 2nd, as tactical developments dictated. The task of securing the Molsheim area was temporarily delayed and transferred to the 45th Division’s 179th regiment, which was scheduled to arrive at Cirey-sur-Vezouse from its rest area before dark on the 22nd. The security and liaison mission north of Sarrebourg and west of the Low Vosges would be undertaken by the 106th Cavalry Group and by the rest of Eagles’ 45th Division as it came out of reserve.

Striking for Strasbourg

Starting out about 0715 on 23 November, the French 2nd Armored Division’s CCL rolled rapidly eastward across the Alsatian plains with TF Rouvillois on the north and TF Massu to the south.20 Overrunning German outposts and minor garrisons in the small Alsatian farming towns, TF Rouvillois achieved complete surprise and entered Strasbourg at 1030 that morning. TF Massu, which was to have driven into the city from the northwest, encountered stronger German opposition, but ultimately followed shortly thereafter. Later, about 1300 that afternoon, CCV also began pouring into Strasbourg from the west, bringing with it a battalion

French 2nd Armored Division moves through Strasbourg

of the 313th Infantry, 79th Division.

Meanwhile, amid almost incredible scenes of German surprise and consternation, Rouvillois’ armor wheeled through the streets of Strasbourg to the Rhine, seizing intact bridges over the canal-like watercourses in the eastern section of the city. Ahead lay the highway and railway bridges over the Rhine to the German town of Kehl; scarcely 650 yards short of the river, however, the French armor ran into strongly manned German defenses in apartment houses and thick-walled bunkers, buttressed by antitank barriers and antitank weapons. Soon German artillery and mortars emplaced east of the Rhine began laying down accurate fire that forced Rouvillois’ troops and vehicles to pull back and seek cover. The local German commanders had apparently ignored any instructions to outpost the Alsatian plains and instead had concentrated on defending certain sections of the city, including the vital Kehl bridges.

Throughout 23 and 24 November TF Rouvillois made several attempts to reduce the German bridgehead, but the result was a stalemate. Lacking strength for an all-out assault in the urban area, the infantry-poor French armored units had to be content with isolating the German enclave from the rest of the city. The Germans, in turn, made no move to reinforce or enlarge the bridgehead and, pending orders to destroy the bridges, held on mainly to aid the escape of German troops and civilians able to infiltrate through the French

vehicles to safety. In the meantime, TF Massu and CCV mopped up isolated pockets of resistance, took hundreds of German troops prisoner, and began rounding up German civilians for internment. By the time the last elements of the French armored division left Strasbourg on 28 November, the division had captured a total of 6,000 German troops—mostly service and administrative personnel—in and around the city and had taken into custody about 15,000 German civilians. From 19 to 24 November the Saverne and Strasbourg operations cost the French division approximately 55 men killed, 165 wounded, and 5 missing.

During this period, the situation in and around Strasbourg made it impossible for CCV and CCL to concentrate sufficient strength to eliminate the German enclave and seize the Kehl bridges. The disorganized but large number of German troops and civilians scattered throughout the city, including many German-speaking inhabitants who were not especially sympathetic to the French, posed a security problem that led to a wide dispersal of Leclerc’s available infantry forces. Having committed the rest of his combat forces, CCD and CCR, to protect his twenty-mile line of communications across the Alsatian plains, Leclerc asked General Haislip to speed American infantry into the city. But developments west of the Vosges, together with the Seventh Army’s directive to move against Haguenau, temporarily tied Haislip’s hands; and Brooks’ VI Corps forces would probably not be able to reach Strasbourg for three or four more days. In the meantime, Leclerc would have to consolidate his existing gains, rest and resupply his forces, and be patient.

Haislip moved quickly to secure Leclerc’s narrow supply line across Alsace. By 24 November all three regiments of the 79th Division had crossed the Vosges and begun to arrive in the Moder River area west of Strasbourg and just south of Haguenau. Behind the 79th, the 44th Division’s 324th regiment and the 45th Division’s 180th regiment took up station along the Alsatian plains north of Saverne, and thus the northern flank of the XV Corps’ penetration east of the Vosges appeared well protected.

On the southern flank, the 45th Division’s 179th regiment reached Wasselonne during the afternoon of the 23rd and, as planned, struck south for Molsheim on the 24th with CC Remy, encountering little resistance. Late in the day it met elements of the 3rd Division’s 15th Infantry, the first of Brooks’ VI Corps units to finally push through the High Vosges and onto the Alsatian plains.21 The juncture of the two units augured the arrival of the rest of the VI Corps units to cement the southern flank of Haislip’s penetration. However, CCR and CCD outposts between Molsheim and Strasbourg had already reported the absence of any German threat in the south, and thus both of Leclerc’s flanks seemed secure.

However, on 23 November, as Haislip’s infantry regiments were pouring across the Alsatian plains, the

XV Corps commander suddenly learned of the arrival of the Panzer Lehr Division on his northern flank west, rather than east, of the Vosges. He immediately suspended movement of all XV Corps forces across the Vosges and began to reorient troops that remained west of the mountains to meet the new threat. First, he transferred the Haguenau mission from the 44th Division to the 79th, which was already positioned reasonably close to the objective area. Second, he ordered the bulk of the 44th to concentrate in the area above Sarrebourg with its 71st and 114th regiments and the two squadrons of the 106th Cavalry. Third, he kept the 45th Division’s remaining regiment, the 157th, east of the Vosges as a reserve. If necessary, Leclerc’s armor could also return to the Sarrebourg area, but Haislip was apparently confident that the 44th Division could handle the danger.

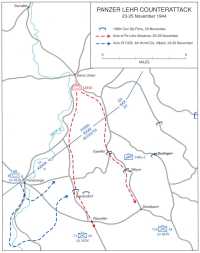

The Panzer Lehr Counterattack

During the evening of 21 November and all of the following day, the 361st Volksgrenadier Division had attempted to establish a defensive line facing south from Mittersheim to Drulingen. The effort was futile, however, and the unit had slowly been squeezed between the advances of the Third Army’s XII Corps from the west and assorted XV Corps units from the south. By dark on the 21st, elements of the XV Corps’ 106th Cavalry Group were either in or north of Baerendorf, Weyer, and Drulingen. The following day, the XII Corps’ 4th Armored Division cleared Mittersheim, and the 106th Cavalry, reinforced by units of the 44th Division’s 71st and 114th regiments, moved up to Eywiller and several other towns—all north of what was to have been the 361st Division’s main line of resistance. Finally, on 23 November, the advance elements of the eastward-moving 4th Armored Division met units of the 71st Infantry near Fenetrange, completely disorganizing the defending Volksgrenadiers and leaving the Panzer Lehr Division with no screening force on its western flank for its projected attack south.

Von Rundstedt and Balck had assumed that the Panzer Lehr, with about seventy tanks, would reach the Sarralbe area in time to launch its counterattack early on the morning of 23 November. However, the division deployed southward more slowly than anticipated; was not in position to attack until 1600 on the 23rd, at least ten hours later than planned; and initially could muster only thirty to forty tanks, two of its four panzer grenadier battalions, and about ten assault guns for the effort.22 By that time the XV Corps had begun to react to the German buildup, and the Panzer Lehr could only hope to achieve some local tactical surprise. Moreover, assistance from other German forces was negligible. The 361st Volksgrenadier Division

was too weak; OKW refused to release the 25th Panzer Grenadier Division for the attack; and the Nineteenth Army, under strong pressure from both the VI Corps and the First French Army, lacked the means to mount any kind of counterattack from the south. Nevertheless, acting virtually alone, Bayerlein’s elite unit launched its drive southward that afternoon.

The Panzer Lehr Division advanced in two columns: a western one with about ten to twelve Mark IV medium tanks moving south through Baerendorf, and a larger, eastern one with twenty to twenty-five Mark V heavies (Panthers) moving parallel down through Eywiller (Map 27). At first the German armor and accompanying panzer grenadiers rode roughshod over the scattered American advance elements. By dusk Bayerlein’s forces had pushed the 106th Cavalry back to Baerendorf and Weyer, and during the night Panzer Lehr’s western column broke through Baerendorf to reach Rauwiller, several miles to the south, taking about 200 prisoners from the 44th Division. Temporarily putting aside all thoughts of celebrating a quiet Thanksgiving holiday, elements of the 106th Cavalry and the 71st Infantry finally slowed down the German thrust just south of Rauwiller. Meanwhile, Panzer Lehr’s eastern column pushed XV Corps cavalry forces out of Weyer and south to Schalbach, forcing the 114th Infantry to move up to cover this second threat. But despite these gains, von Rundstedt viewed the southward progress of the panzer division as too slow, and during the night he advised OKW that the counterattack had little chance of success.

Unknown to von Rundstedt, the situation of the Panzer Lehr had actually become much more precarious. While the German division was moving south, the XII Corps’ 4th Armored Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. John S. (“P”) Wood, had resumed its advance west toward Sarre-Union. Judging the soggy ground west of the Sarre River to be unsuitable for armored operations, Maj. Gen. Manton S. Eddy, the XII Corps commander, obtained permission from General Haislip to have the American armored unit’s CCB move eastward across the Sarre into the XV Corps’ zone, before swinging north toward Sarre-Union.23 A clash between the two opposing armored formations was inevitable.

Crossing the Sarre at two points near Baerendorf on the morning of 24 November, the American combat command almost immediately ran into the Panzer Lehr Division’s exposed western flank. House-to-house and tank-to-tank fighting ensued at Baerendorf until, during the afternoon, CCB’s southern column cleared the small town, while the northern column contained German armored units attempting to outflank the embattled American forces. Elsewhere, the 71st Infantry retook Rauwiller before dark, and the 106th Cavalry Group, while losing some ground along the western slopes of the Vosges, managed to hang on to

Map 27: Panzer Lehr Counterattack 23–25 November 1944

Schalbach and stabilize the rest of the American line through Drulingen.

In light of these developments, von Rundstedt reduced the mission of the Panzer Lehr from closing the gap between Balck’s two armies to just blocking Route N-4 between Sarrebourg and Saverne. The change probably reflected his realization that the Nineteenth Army was in no condition to launch any kind of supporting attack from the south, but the mission was still too ambitious. Although von Rundstedt also directed Balck to feed the 25th Panzer Grenadier Division into the battle, he must have known that the understrength 25th could not reach the Sarre–Union area until 25 November; even then it was doubtful that its addition could influence the struggle.

General Balck’s evaluation of the counterattack became increasingly pessimistic throughout the 24th. He had expected the leading units of the 256th Volksgrenadier Division to reach Haguenau that day and had planned to commit the units of the division to supporting attacks east of the Vosges as they arrived on the front. However, transportation problems continued to delay the arrival of the division, and the first units did not reach Haguenau until 26 November, with the rest of the division following on the 28th.24 In any case von Rundstedt, who appeared to have little faith in the counterattack, now directed Balck to use the 256th in a defensive role around Haguenau, an order that effectively disassociated the arriving division from the Panzer Lehr operation. Finally, Balck learned that the 245th Volksgrenadier Division, also arriving from the Netherlands, would not reach the First Army’s sector before 3 December, far too late to have any bearing on the situation he was facing in the Sarre valley.

On 25 November the battle in the Sarre River valley resumed. Just before dawn, the Panzer Lehr’s western column launched an attack against the 4th Armored Division’s CCB elements at Baerendorf and reoccupied part of Rauwiller. Confused fighting lasted several hours, but again the Germans were forced to withdraw to the north and east with little accomplished. Meanwhile, the stronger eastern Panzer Lehr column was a bit more successful, overrunning part of the 2nd Battalion, 114th Infantry, near Schalbach. But American artillery helped turn back further German advances south, and by afternoon all German offensive operations in the area had stopped.

The Schalbach action proved to be the high point of the Panzer Lehr counterattack, and on the evening of the 25th von Rundstedt, with Hitler’s reluctant consent, called off the operation. The German panzer division immediately began to withdraw northward to temporary defensive lines between the Sarre River and Eywiller to lick its wounds. The movement marked the end of any danger to XV Corps’ northern flank. Still relatively unscathed, Haislip’s forces were ready to resume their attack to the east.