Chapter 23: Through the Belfort Gap

The first Allied troops to arrive at the Rhine River in the 6th Army Group’s sector of the western front were French, and the signal honor of reaching the Rhine first belonged to a detachment of the French 1st Armored Division, a component of Bethouart’s long-quiescent I Corps. This patrol reached the Rhine on 19 November at Rosenau, some thirty miles east of Belfort and about seventy miles south of Strasbourg. Thus, even as Haislip prepared to unloose Leclerc’s 2nd Armored Division against Saverne and as Brooks maneuvered his forces for the crossing of the Meurthe, de Lattre’s French forces had already completed the first stage of their long-awaited Belfort penetration.

The First French Army’s Front

While the First French Army began to deploy for the November offensive, the width of its front had continued to grow as Devers moved its boundary with the U.S. Seventh Army northward. In mid-November de Lattre’s northern boundary thus followed the trace of Route N-417 from Remiremont on the Moselle northeast to Le Tholy and then east to Gerardmer deep in the Vosges (Map 29). From there, the boundary again turned northeast across the Vosges and continued to Erstein, about twelve miles south of Strasbourg, and then crossed the Rhine to Offenburg. As the First French Army’s southern boundary remained fixed on the irregular but stable east-west Swiss border, every northeastern advance of the northern boundary would obviously enlarge the army’s frontage as it moved east.

In early November de Lattre had both of his corps on line with two infantry divisions apiece and had withdrawn his two armored divisions for rest and refitting. On the First French Army’s left, de Monsabert’s II Corps faced the steep mountains and narrow passes of the High Vosges, while on the right Bethouart’s I Corps stood poised before the long-prepared German defenses of the Belfort Gap. The inter-corps boundary led east from the vicinity of Lure, passed south of Champagney (twenty-five miles south of Gerardmer), and stretched east again to Valdoie, just three miles north of Belfort. De Lattre tentatively intended to extend the inter-corps boundary east and northeast to Mulhouse, on the Alsatian plains twenty-five miles south of Colmar.

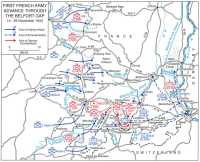

Map 29: First French Army advance through the Belfort Gap, 14–25 November 1944

The French II Corps had on line, from north to south, the 3rd Algerian Infantry Division and the 1st Infantry Division, both reinforced by a few regular and FFI units.1 The 3rd Algerian Division held the corps front from the vicinity of Le Tholy southeast about ten miles to Cornimont. The 1st Infantry Division extended the front south almost twenty miles farther to Ronchamp, just west of Champagney.

Below these units, the I Corps had on its left a provisional force, Group Molle,2 holding a front that ran south about seven miles from Ronchamp. On Group Molle’s right was the 2nd Moroccan Infantry Division, covering a sector that stretched south ten miles to the Doubs River. South of the Doubs, the 9th Colonial Infantry Division’s lines ran southeast and then east to the Swiss border at Villars, eighteen miles south of Belfort. Both divisions had more or less permanent FFI and regular attachments, while for the offensive de Lattre intended to reinforce the I Corps with the 5th Armored Division, CC2 of the 1st Armored Division, a regimental combat team of the 4th Moroccan Mountain Division,3 two separate tank destroyer battalions, the 9th Zouaves (light infantry), and a host of lesser units. De Lattre also gave I Corps first priority for units in the First French Army’s general reserve, which would be made available to the two corps as the situation dictated.4

Fire support for the French offensive would have an American flavor. In the I Corps, the artillery was commanded by Brig. Gen. Carl C. Banks, USA, who was also in charge of the U.S. Army’s 13th Field Artillery Brigade. For the Belfort offensive, the brigade (exclusive of French units) consisted of the 1st Field Artillery Observation Battalion; the 36th Field Artillery Group; and the 575th, 630th, 697th, and 933rd Field Artillery Battalions. In addition, the U.S. Army’s 2nd Chemical Mortar Battalion (4.2-inch) was in direct support of the 9th Colonial Division.

In general, the First French Army’s forces were rested and in fairly good condition for the November offensive. The only major exception was the 3rd Algerian Division, which had not been out of the front lines since it first began moving against Toulon and Marseille on 20 August. Although the division had undertaken no substantial offensive operations since the first week of November, it had continued aggressive patrolling in order to focus German attention on the High Vosges. There its units had been operating in the most rugged terrain

and during the worst weather on the entire French front. The 1st Infantry Division, by contrast, had seen relatively little action since late September and, adopting a generally defensive attitude, had spent most of October absorbing indigenous replacements for its black troops. The 2nd Moroccan Division had likewise engaged in mainly defensive action since taking over its sector north of the Doubs River in early October, as had the 9th Colonial Division south of the Doubs. The 1st Armored Division had not been in heavy combat since mid-October and had come out of the line on the 25th of that month. The 5th Armored Division was fresh but untried. Finally, all units were fully equipped and had devoted substantial time to training and building up their supply stocks. Although the weather conditions had somewhat dampened the spirits of the French troops for the coming offensive, most were confident that they would soon overcome the best the Germans had to offer in the Belfort Gap and the southern Vosges.

Defending the Gap

From Le Tholy south about fifteen miles to Le Thillot, the left wing of the Nineteenth Army’s IV Luftwaffe Field Corps confronted the left of de Monsabert’s II Corps.5 South and southeast about thirty-five miles from Le Thillot to the Swiss border, LXXXV Corps was responsible for holding the approaches to Belfort and blocking the Belfort Gap. In static defensive positions behind this corps, Fortress Brigade Belfort held the city of Belfort and the old stone and masonry forts that encircled it. East of these organizations, provisional Corps Dehner controlled other provisional units along the Swiss border and temporarily served as a reserve headquarters.

On 7 November Army Group G learned that LXXXV Corps headquarters was to be transferred to Army Group B, and on the 14th Corps Dehner took over the tactical command in the Belfort sector. Having only a skeletal staff and lacking the normal corps support units, Corps Dehner was ill prepared for its expanded role. Officially given the title of corps on 15 November, the organization became LXIII Corps on the 18th, and its former security mission along the Swiss border went to an ad hoc organization designated Staff Boineburg. The entire command change could hardly have come at a worse time for the German defenders.

Whatever the deficiencies of the corps-level commands, the Nineteenth Army could rely on several fairly good divisions in the Belfort area. On the north, holding a sector extending some five miles south from Le Tholy, the left of the 198th Division faced part of the 3rd Algerian Division. Understrength but consisting largely of battle-tested veterans, the 198th could be depended on to hold its ground. The rest of the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps zone was held by the relatively strong and fresh 269th Volksgrenadier Division, which had recently arrived from Norway.

From the corps’ boundary at Le Thillot south about fifteen miles to

Route N-19—the main east-west highway through Belfort—the 159th Division held good defensive terrain with three rebuilt regiments that had felt little pressure since late September. The division, with a southern boundary that corresponded roughly to the First French Army’s inter-corps boundary, faced most of the French 1st Infantry Division. Two regiments of the 159th were almost up to strength, and the weaker third regiment was made up of fortress and Wehrkreis V troops. The division had less than half of its authorized artillery, and its antitank battalion was considerably understrength.

From Route N-19 south about ten miles stood the 189th Division, facing Group Molle and much of the 2nd Moroccan Division. The 189th was also responsible for the defense of Hericourt, a key highway junction and railroad town about six miles southwest of Belfort. The division was truly an ersatz unit. The division headquarters had formerly belonged to the 242nd Infantry Division, most of which had been destroyed in southern France during August. One infantry regiment was built on a former police security regiment, and a second on a Luftwaffe infantry training regiment; the third had been pieced together from stragglers and miscellaneous small units rounded up in the Belfort area. The division lacked reconnaissance and engineer battalions, was short of both artillery and ammunition, was weak in antitank weaponry, and had scant reserves. Nevertheless, the 189th had had time—since late September—to weld its disparate components together, and the Nineteenth Army rated the division as adequate for defensive purposes.

From a point a mile or so south of Hericourt, the 338th Infantry Division extended the German front south and southeast over fifteen miles to the Swiss border. The 338th, facing the right of the 2nd Moroccan Division and all of the 9th Colonial Division, was the weakest link in the German line. Pulled out of the High Vosges toward the end of October, the division had brought south just two ad hoc infantry regiments, both of which were suitable only for static defensive missions.6 The division was also short of artillery and devoid of reserves, deploying all of its existing infantry on its eggshell-thin front line. In brief, the Germans had inadvertently placed their weakest division along what was to be the focal point of the French attack.

Situated slightly to the rear of the 189th was Fortress Brigade Belfort, with two fortress artillery battalions and several fortress machine-gun companies. Necessity had forced the brigade to transfer some of its artillery to the infantry divisions, while a number of its remaining guns were captured French and Russian pieces for which little ammunition was available. The brigade had recently received thirty new 88-mm. antitank weapons of German manufacture, but most of them had arrived lacking vital parts, such as sights.

As a tactical reserve, the LXIII Corps7 stationed two understrength infantry battalions at Belfort, while an understrength infantry battalion of

the 189th Division was also earmarked for a reserve role. However, as was the case elsewhere along the Nineteenth Army’s front, there were no true reserves. All of the armored units that had once been scheduled for the Belfort Gap had been diverted either to the First Army or to the Nineteenth Army’s northern front. In an emergency at the Belfort Gap, General Wiese could call only on the NCO training center at Colmar—some 1,500 troops in all, counting students, faculty, and staff. A more remote possibility was the 30th SS Grenadier Division, a unit of conscripted Russian nationals stationed near Mulhouse who were waiting for transportation east across the Rhine. Following a mutiny in September, the division had been reorganized, but was still considered unreliable. Nevertheless, the unit now had a substantial German cadre (one German to three Russians) and might have some defensive possibilities. Outside of these forces, however, the Nineteenth Army had no other reserves from Colmar south to the Swiss border.

The weaknesses of the German forces in the Belfort Gap sector reflected a fundamental difference of opinion between General Balck of Army Group G and General Wiese of Nineteenth Army regarding the intentions and capabilities of the French. After de Lattre had halted the attempt by de Monsabert’s II Corps to outflank Belfort on the north in October, Wiese decided that the French would ultimately switch their main effort to a drive through the Belfort Gap itself in order to take advantage of better terrain. Balck, on the other hand, was convinced that the French would sooner or later resume their advance across the High Vosges, aiming for Colmar on the Alsatian plains. Once this had been accomplished, the Army Group G commander thought that the French would then swing back south to open the Belfort Gap by attacking from the rear. Any French pressure toward the Belfort Gap from the west, he believed, was only an effort to divert Army Group G’s attention away from a major threat across the Vosges. For this reason Balck insisted that Wiese keep two of the Nineteenth Army’s best divisions, the 198th Infantry and the 269th Volksgrenadier, in the High Vosges, occupying the excellent mountain defensive terrain opposite the French II Corps; meanwhile, the relatively flat area south of Belfort, a region much more difficult to defend, was left in the hands of the ailing 338th Division.

De Monsabert’s diversionary attack of 3–5 November in support of VI Corps’ DOGFACE offensive created a stir at Army Group G headquarters and undoubtedly confirmed Balck’s estimate of French intentions. Meanwhile, de Lattre initiated an elaborate deception program that also focused Army Group G’s attention on the Vosges. Carefully prepared false or misleading orders found their way into German hands;8 troop movements that never took place were brought to the attention of the Germans; and fake command posts for I Corps units were established in the II Corps sector. Then, as 13 November

approached, all attack units of Bethouart’s I Corps began moving up to their lines of departure under cover of darkness; poor weather, although creating some problems for the French, further concealed the assembly of attacking forces.

French Plans

The role of de Monsabert’s II Corps in the November offensive was at first limited to maintaining an attitude that was aggressive enough to keep the Germans worried about the Vosges front.9 Depending on available strength and on developments in the I Corps sector, the II Corps was ultimately to drive across the Vosges along the axis of Route N-66 and the Bussang Pass in order to join I Corps forces in the vicinity of Mulhouse. On the I Corps’ left side, Group Molle was to maintain contact with the II Corps and seize the dam at the Champagney reservoir, about three miles southeast of Champagney, to prevent the Germans from flooding the Lisaine River valley between Hericourt and Montbeliard.

South of Group Molle, the 2nd Moroccan Infantry Division was to launch the I Corps’ main effort, first driving eastward north of the Doubs to the Lisaine valley, and then seizing Belfort city with the surprise attack from the south. Failing that, the division was to encompass Belfort on the north and south, attacking the metropolitan area and the surrounding forts from the rear. Initial reinforcements for the 2nd Moroccan Division included two combat commands of the 5th Armored Division, CC4 and CC5, and four or five FFI infantry battalions.

Below the Doubs River, the 9th Colonial Infantry Division was to drive generally northeast, its left flank on the Doubs and its right on the Swiss border. Continuing across a north-south stretch of the Doubs (which makes a great loop near Montbeliard), the division would press northeastward to the general line of the Allaine River between Morvillars and Delle, on the Swiss border. The 9th Colonial Division’s reinforcements included CC2 of the 1st Armored Division, the 6th Moroccan Tirailleurs (a regimental combat team) of the 4th Moroccan Mountain Division, the 9th Zouaves, a tank destroyer battalion, and four FFI infantry battalions. Both the main and secondary attacks were to begin simultaneously on 13 November.

The I Corps Assault

During the night of 9–10 November I Corps’ leading attack units began moving up to their lines of departure for the assault on the 13th. The weather had been rainy and overcast for several days, and on the 9th continued heavy rains increased the flooding along the Doubs and its tributaries. During the next few days, problems caused by inclement wealther mounted. Many of the corps’ temporary

bridges were washed out or seriously damaged; lesser roads became impassable for wheeled or even tracked vehicles; wire communications failed; radio transmissions were sporadic; and low visibility made the registration of artillery fire almost impossible. On the 11th, General Bethouart, the I Corps commander, suggested postponing the attack until the weather improved. At first de Lattre refused to countenance any delay, but approved some changes, agreeing with Bethouart’s proposal to have the 9th Colonial Division lead off the attack. Since the so-called colonial division was now made up mostly of younger troops from metropolitan France, the French generals thought that these soldiers might be better able to contend with the mud, rain, snow, and increasingly cold weather than the men of the 2nd Moroccan Division. Accordingly, the generals moved the date of the 9th Colonial Division’s attack up to the 13th and pushed that of the 2nd Moroccan Division back to the 14th. De Lattre also instructed Bethouart to move his armor forward on the 14th, somewhat earlier than planned, so as to be ready to exploit any success the two infantry divisions might achieve. Finally, the French army commander directed de Monsabert’s II Corps to launch diversionary attacks in the Champagney area on 13 and 14 November.

For both sides, dawn of 13 November revealed what de Lattre later described as a “Scandinavian landscape.”10 Heavy snow had been falling for hours, and the almost complete lack of visibility forced the French to cancel the attack. The next morning, 14 November, low, dark clouds continued to cover much of the sector, but some clearing took place north of the Doubs. After another quick change of plans, de Lattre and Bethouart ordered the offensive to begin, with the 2nd Moroccan Division attacking at 1200 behind a two-hour artillery preparation, and the left wing of the 9th Colonial Division joining in at 1400. Elsewhere on the 9th Colonial front, fog, sodden terrain, and additional snowfall held the division in place.

As the French were preparing their attack, Maj. Gen. Friederich-August Schack, the newly appointed commander of the defending LXIII Corps, decided to take a personal look at his unfamiliar front. Schack drove to an observation post near Bretigney, on the north side of the Doubs River about eight miles west of Montbeliard, and on the way picked up Maj. Gen. Hans Oschmann, commanding the 338th Infantry Division. Suddenly French artillery began a devastating barrage that immobilized the observation party—the two generals, each with an aide; it was over two hours before the small group could start groping eastward through woods that artillery fire had turned into a shambles. Running into small groups of Moroccan infantrymen, Oschmann was killed and the two aides captured, but Schack somehow made his way past the Moroccans and reached his command post at Belfort before dark.

In the midst of the melee in the woods, a detailed map of the 338th Division’s dispositions fell into French hands, along with notes revealing that

Oschmann, far from expecting a major attack, had concluded that the French across his front were digging in for the winter. For the 338th Division, the attack of the 2nd Moroccan Division had thus come as a complete surprise, and the response of the defenders was further hampered by the absence of both the corps and division commanders during the early stages of the attack. To make matters worse, the French artillery fire had also disrupted German wire communications, making it impossible for the LXIII Corps’ staff to obtain an accurate picture of the situation at the front.

During the first day of the attack, 14 November, the left wing of the 2nd Moroccan Division gained little ground against the relatively strong 189th Division, but in the center and on the right the Moroccans broke through 338th Division positions across a front of nearly six miles and advanced over two miles into the German lines. With its attack delayed until 1400, the 9th Colonial Division found 338th Division units south of the Doubs on the alert, yet pushed forward on the left a mile and a half across a three-mile front.

French armor played only a minor role in the early gains, but de Lattre, hoping for a breakthrough on the 15th, immediately released the headquarters and CC3 of the 1st Armored Division to the I Corps, leaving only the division’s CC1 as the First French Army’s main reserve (as well as the only element of the division immediately redeployable to the Atlantic coast). General Bethouart, the I Corps commander, intended to retain both the 1st Armored Division’s CC3 and the 5th Armored Division’s CC6 as his own reserve, while allowing the 9th Colonial Division to retain CC2 and the 2nd Moroccan Division to keep CC4 and CC5. If the armored units advanced ahead of the infantry, they could begin operating independently under the control of the armored division headquarters.

Despite French advances, no alarm bells rang on 14 November at Army Group G, where Balck continued to regard all activities on the Belfort front as a ploy to divert attention from the Vosges. More concerned with the situation on the Nineteenth Army’s northern front and with the First Army’s sector, Army Group G had even begun preparations to move the 338th Division north by rail during the night of 14–15 November. The result was a tug of war that evening between Army Group G and the Nineteenth Army. While Balck was directing the Nineteenth Army to pull the 338th Division out of the Belfort lines, Wiese, the Nineteenth Army commander, was instructing the LXIV Corps to disengage the division’s missing regiment from the St. Die area and speed the unit south to the Belfort front. At the same time, Wiese ordered the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps to move two field artillery battalions (one of them organic to the 338th Division) south to Belfort, along with two light antiaircraft battalions. Pending the arrival of these units, General Schack of LXIII Corps committed his three reserve infantry battalions in the 338th Division’s sector early on the 15th.

Schack’s reinforcements had little immediate impact. On 15 November the center and right of the 2nd Moroccan Division gained another three miles in the 338th Division’s sector; to

the south, the 9th Colonial Division overran some of the 338th Division’s strongest positions and seized a number of important road junctions. By dark the 338th Division’s front was thus completely disorganized, and General Wiese directed the LXIII Corps to pull the division back a mile or two in an attempt to stabilize it along a new line. Then—and only then—did Wiese seek permission from Army Group G to execute the withdrawal. Lacking accurate information regarding the situation on the Belfort front, however, Balck continued to call for the complete disengagement of the 338th from the south, leaving Wiese with little choice except to procrastinate, thereby creating a temporary stalemate over the matter.

On 16 November French armor, previously slowed by mud, disintegrating roads, and extensive minefields, began to play a more decisive role. With their left flank along Route N-83, the Hericourt–Belfort highway, elements of the 5th Armored Division and the 2nd Moroccan Division reached a point scarcely a mile short of Hericourt and the Lisaine River. To the south and along the Doubs, the Moroccans and attached armor advanced another two miles to the east and northeast. Even farther south the 9th Colonial Division’s attack finally gathered momentum, with the support of the 1st Armored Division’s CC3, and advanced up to three miles. On the far right, close by the Swiss border, French troops reached the vicinity of Glay, seizing more road junction towns and further disrupting local German tactical communications, which depended heavily on the telephone and teletype lines of the German-controlled French civil communications system.

During the course of 16 November, General de Lattre released CC1 of the 1st Armored Division from army reserve. This move came as something of a surprise to General du Vigier, who commanded the armored division, for he had been prepared to start CC1 toward the Atlantic coast on the 18th, with the rest of the division following on the 21st. On the 17th, however, de Lattre officially halted further deployments for INDEPENDENCE and told du Vigier that departures for the Atlantic coast would be postponed a minimum of four days.11

De Lattre’s action must have had at least the tacit approval of General Devers, who was having increasing doubts about removing any major units from the First French Army at such a crucial point in the Belfort Gap offensive. On the 16th Devers told Lt. Gen. Sir Frederick E. Morgan, the SHAEF Deputy Chief of Staff, who was visiting the 6th Army Group command post, that no French units would be withdrawn from the Vosges and Belfort fronts as long as they continued their current drive; he believed that Morgan agreed with his position.12 Thus, for at least a few more days, Bethouart’s attacking

corps could look forward to employing two full armored divisions against the weakening German forces on the Belfort front.

On the other side, the German commanders had been unable to resolve their differences. All day long on the 16th, Wiese continued to argue with Army Group G over the redeployment of the 338th Division, which by dark was becoming so disorganized that its disengagement would have been extremely difficult. By that time even OKW was becoming perturbed about the situation and informed OB West that a French breakthrough at the Belfort Gap had to be prevented at all costs; OB West quickly relayed these instructions to Army Group G. About 2000 on the 16th, General Balck, now under pressure from his superiors to reevaluate the entire situation, decided to leave the 338th Division in place and to send instead the much better 198th Division of the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps to the First Army. At the same time Balck directed that the shattered 16th Volksgrenadier Division and the weak 716th Division, both still deployed in the St. Die area, be moved south to replace the 198th Division in the southern Vosges.

After absorbing these orders, General Wiese of Nineteenth Army must have felt that he had won a battle but lost a campaign. He had intended to redeploy the 198th Division to the Belfort Gap and the 16th Volksgrenadier Division to his northern flank, leaving only the 716th Division in the St. Die area. In retrospect, he probably would have been content to lose the 338th, if he could have retained the 198th. The decisions, however, were not his to make, and Balck’s orders made the German situation in the south even more precarious.

Finally, during the evening of 16 November, Balck gave Wiese permission to undertake a limited withdrawal. The LXIII Corps was to pull back to the Lisaine River, between Hericourt and Montbeliard, and the southern elements of General Schack’s 338th Division were to make a parallel withdrawal between Montbeliard and the Swiss border. But Wiese, acting on his own, had already approved a similar withdrawal on the previous evening, so Balck’s new directions had little bearing on the situation around Belfort.

Breakthrough

On 17 November the German front began to fall apart. The 2nd Moroccan Division and its armored attachments overran 189th and 338th Division positions and pushed bridgeheads across the Lisaine River between Luze, Hericourt, and Montbeliard. To the south, the center of the 9th Colonial Division pushed east about five miles to Herimoncourt. Its left wing joined the Moroccans at Montbeliard, and its right wing, led by CC2, reached out to Abbevillers, three miles northeast of Glay, encountering only spotty resistance.

Sensing an imminent breakthrough, General Bethouart issued new orders, which de Lattre tentatively approved. Du Vigier’s 1st Armored Division (reinforced)13 was to assemble in the

Abbevillers–Herimoncourt area in order to strike east between the Rhone–Rhine Canal and the Swiss border. His main effort was to take place on the left with the first objective being Morvillars, seven miles northeast of Montbeliard and close to the south bank of the canal. Then du Vigier was to push on to Dannemarie, a rail and road center along Route N-19 on the south side of the canal about twelve miles east of Belfort. Behind the 1st Armored Division the 9th Colonial Division was to mop up, secure the armored division’s left flank, and seize bridgeheads along the Rhone–Rhine Canal between Montbeliard and Morvillars.

In part, the bridgehead mission was designed to support attacks against Belfort by the 2nd Moroccan Division and the attached combat commands of the 5th Armored Division. However, indications are that de Lattre and Bethouart felt that Belfort could be secured in a few days primarily by infantry forces and that the combat commands of the 5th Armored Division could be returned to division control by noon on 19 November. Then, de Lattre envisaged, the entire armored division could begin an exploitation along the general axis of Route N-83 from Belfort northeast to Cernay and ultimately to Colmar. To accomplish this, the division was first to move south and then east, crossing the Rhone–Rhine Canal at or near Morvillars and continuing north to N-83, bypassing all of the urban Belfort region on the east.

Meanwhile, a new struggle between Army Group G and the Nineteenth Army had developed over the deployment of the 198th Division. About noon on 17 November General Balck decided to leave the 198th under Wiese’s control, but specified that he move the division to the Nineteenth Army’s northern flank, where the attack against Sarrebourg by Haislip’s XV Corps was beginning to have an effect. For the moment Balck approved the transferral of only one regimental combat team of the 269th Volksgrenadier Division south, from the IV Luftwaffe Field Corps’ Vosges front to the Belfort area. That evening, probably because of pressure from OKW and OB West, Balck finally decided that the French operations around Belfort were more significant than he had first believed, and he approved the movement of the 198th Division, along with the regiment of the 269th Volksgrenadiers, to the Belfort Gap. About the same time he also gave Wiese permission to pull the LXIII Corps back to the Weststellung—actually, a southeastern extension of the Vosges Ridge Position—from Hericourt southeast to the Swiss border.

Once again the German reaction come too late to affect the situation on the ground. The withdrawal, which concerned primarily the 338th Division, began after midnight, and dawn on 18 November found 338th troops still retreating east. To avoid French roadblocks and to take advantage of the best roads, most of the units south of the Rhone–Rhine Canal withdrew through Morvillars with the intent of reforming along the Allaine River and Route N-19A. There the northern trace of the Swiss border would greatly reduce the frontage that the survivors of the 338th would have to hold. However, the withdrawal plans required the division first to

French light tanks at Huningue

reassemble in the Allaine River valley and then to move into the Weststellung positions, many of which were little more than symbols on a map.

Again the French gave the Germans no respite. Long before the German redeployments could be completed, units of the 1st Armored Division had penetrated the Weststellung positions from Morvillars southeast to Delle, having encountered mainly service troops and security detachments. Only in the Morvillars area did the 338th Division successfully defend a Weststellung location, but French armor broke into the Allaine valley well south of Morvillars and pushed north across the river for about three miles. At Delle, two miles beyond the Weststellung southern anchor, another armored force seized a bridge over the Allaine; meanwhile, closer to the Swiss border, other armored units probed eastward four miles beyond Delle to Courtelevant without encountering significant opposition. This last advance took place along Route N-463, a good highway that led toward the Rhine, less than twenty-five miles away.

The French advance continued the next day, 19 November, but with little success on the left wing where the Germans held on to part of Morvillars. There CC2 of the 1st Armored Division and elements of the 9th Colonial Division were unable to secure any crossings over the Rhone–Rhine Canal and, in the face of stiffening opposition, made scant progress

toward Dannemarie. French losses now began to mount, and casualties in the armored command alone included 30 men killed, about 60 wounded, and 11 tanks destroyed.

To the south CC3, starting out from Courtelevant before dawn, headed eastward in three columns. Pushing along Route N-463 through Seppois and over the Largue River, the advancing armor reached Largitzen north of the highway, Moernach south of the road, and Waldighofen in the center, located on N-463 eleven miles east of Courtelevant and only twelve miles from the Rhine River. During the afternoon of the 19th, an advance detachment of the command swung off along back roads; it avoided almost all German defenses and reached the Rhine at Rosenau, twelve miles northeast of Waldighofen, a little after 1800 that evening.14 Reinforcements soon came forward, and the 2nd Battalion of the 68th African Artillery, 1st Armored Division, lobbed a few shells across the Rhine—the first French artillery fire to fall on German soil since the spring of 1940. The breakthrough had been achieved.

As de Lattre received word that his forces had reached the Rhine, General Devers had more good news for the French commander. Devers had again been able to postpone the departure of the 1st Armored Division for Operation INDEPENDENCE on the Atlantic coast, this time until mid-December. However, the redeployment of the 1st Infantry Division remained set for the end of November. Having already postponed the start of INDEPENDENCE from 10 December to 1 January, Devers now pushed the starting date back even further to 10 January, a delay that SHAEF approved.15

The Battle of the Gap

However promising the Rosenau penetration, the French situation in the Belfort Gap at dusk on 19 November was by no means secure. The operations of the 2nd Moroccan Division against Belfort had not progressed as rapidly as hoped, and de Lattre found it necessary to leave the 5th Armored Division’s CC6 attached to the Moroccan unit, while the rest of the armored division moved south. In fact, the 2nd Moroccan Division, even with the support of CC6, was unable to clear the Belfort area until 25 November.16 A second major problem was the failure of the 9th Colonial Division and CC2 to secure crossings over the Rhone–Rhine Canal, thus making it impossible for the 5th

Armored Division to begin its drive toward Cernay. Instead the armored division was temporarily immobilized in the Montbeliard region, where its long columns of vehicles clogged the supply routes of the 9th Colonial and 1st Armored Divisions.

A third danger was the nature of the French penetration. The 1st Armored Division’s CC3 had poked out a very slender salient to the Rhine, and its supply routes east from Delle were extremely vulnerable. In order to secure the armored command’s lines of communication eastward, Bethouart’s forces would have to clear and hold the cut-up, hilly, and largely wooded terrain south of the Rhone–Rhine Canal from Morvillars to Dannemarie, as well as similar terrain south of Route N-19 from Dannemarie to Altkirch. Although de Lattre was not an ULTRA recipient, he knew from his own sources that the German 198th Infantry Division had moved out of the Vosges and must have expected it to arrive in the threatened area shortly.17

De Lattre gave the task of securing the French penetration to the 9th Colonial Division. He ordered the 1st Armored Division, joined by its CC1 on 20 November, to clear the west bank of the Rhine from Huningue (on the Swiss border) north seventeen miles to Chalampe, where several major bridges crossed the Rhine. However, Dannemarie on Route N-19 was still an objective of the 1st Armored Division, which indicated that de Lattre felt the muscle of both divisions would be needed to hold the broad area north of the French penetration. Finally, de Lattre remained confident that the inexperienced 5th Armored Division (less CC6) would somehow find a way to breach the Rhone–Rhine Canal on the 20th and launch a drive north toward Colmar, which would parallel the 1st Armored Division’s projected advance north along the Rhine. A second breakthrough by the 5th Armored Division would also greatly hamper any German efforts to interdict the supply lines of the 1st Armored Division along Route N-463 and would complete the German rout.

On the other side of the front, General Wiese of Nineteenth Army, at dusk on 19 November, was considering another major withdrawal, abandoning Belfort and pulling his army’s southern flank all the way north to Mulhouse. At OB West, however, von Rundstedt was adamantly opposed to giving up Belfort without a protracted fight. Instead, he directed Army Group G to hold at Belfort and, at the same time, to mount a counterattack south of the city, cutting off the French penetration and pushing their forces back south and west of the Allaine valley.

Finding the means to hold Belfort and simultaneously mounting a counterattack posed major problems for Wiese. During the period 17–19 November the German command had shifted four battalions of the 189th

Division to the 338th Division’s sector, a step that weakened the defenses of Belfort city but did little to stay the French advance.18 By November, the 490th Grenadiers of the 269th Volksgrenadier Division had also reached the front with orders to push down the Allaine valley south of Morvillars. Before the 490th could attack, however, the French had driven past the valley and attacked Morvillars in strength. The 490th had then deployed defensively in the vicinity of Brebotte, on the Rhone–Rhine Canal three miles northeast of Morvillars, at least blocking further advances along the canal to Dannemarie. On the same day, two Wehrkreis V infantry battalions, hurriedly brought across the Rhine, deployed along the canal to the northeast of the 490th Grenadiers; it was these forces that prevented the French from crossing the waterway, which would have allowed the 5th Armored Division to begin its drive to the northeast. Additional reinforcements on the way included another infantry battalion, a small armor-infantry task force with ten tanks, and an antitank company, all from Wehrkreis V; meanwhile, Wehrkreis VII was preparing two regimental combat teams for deployment west of the Rhine. Other units that would arrive in the Belfort Gap sector within a day or two included the 280th Assault Gun Battalion and the 654th Antitank Battalion, the latter unit equipped with thirty-six new 88-mm. guns mounted on Mark V (Panther) tank chassis.

Casting about for additional forces, Wiese secured permission to employ the unreliable 30th SS Division. Initially, the division’s role was to be limited to a holding mission along the Largue River, which Route N-463 crossed at French-held Seppois. However, the redeployment of the 198th Division, which was scheduled to launch an attack toward Delle and the Allaine valley during the night of 19–20 November, was so slow that Wiese assigned to the 30th SS a supporting offensive role. While the 198th Division struck for Delle, the 30th SS Division was to retake Seppois and block the Largue valley north and south of Route N-463.

It was almost dark on 19 November before the 198th Division had assembled sufficient forces (actually, hardly more than a regimental combat team) in the Dannemarie area for its counterattack south. With little or no prior reconnaissance, the division moved southward through terrain characterized by poor roads, swamps and lakes, and many stands of thick woods. Early on the 20th, its leading elements reached Brebotte, Vellescot, and Suarce, about halfway to the final objective, Delle; but they were finally halted after running into French armor and infantry deploying for an attack in the opposite direction, toward Dannemarie. The result was inconclusive fighting throughout the afternoon of the 20th centering around Suarce. Meanwhile, to the east, elements of the 30th SS Division advanced to a point just over a mile north of Seppois, but had to withdraw under French pressure. The French then set up blocking positions in the Largue valley to protect the Seppois

bridges, across which a steady stream of French military traffic passed throughout 20 November.

While CC2 and elements of the 9th Colonial Division turned back the 198th Division’s first counterattacks, the 1st Armored Division was ready to begin its part of the drive north. By 1000 on 20 November, CC3 had assembled in the area of Bartenheim, three miles west of the Rhine at Rosenau; CC1, coming forward through Delle and Seppois, began pulling into Waldighofen about noon. Meanwhile, an armored reconnaissance squadron, speeding northeast along Route N-73 from Moernach, reached Huningue on the Rhine River near the Swiss border, but was unable to eliminate a strong bridgehead that the Germans had established on the west bank of the Rhine, nor could it create a bridgehead of its own on the east bank.

At this juncture, French operations also began to exhibit some confusion. Like Patch, de Lattre had no clear idea of his army’s long-range objectives once the Rhine had been reached and Belfort cleared. The formulation of more specific plans to clear the entire Alsatian plains or force a crossing of the Rhine had not yet begun. Although de Lattre’s general plans had called for the early seizure of Mulhouse, he began to attach more importance to a deep drive north along the Rhine to the Chalampe bridges as the offensive progressed; between 18 and 20 November, he had conveyed these ideas to Generals Bethouart and du Vigier. De Lattre was, in fact, ready to let the 1st Armored Division bypass Mulhouse on the east in order to speed the drive north.19 His field commanders, however, may have viewed an early seizure of undefended Mulhouse as necessary to secure the flank of a major drive north. In addition, the lure of historic Mulhouse, the second most important city of Alsace after Strasbourg, may have influenced the French officers. Whatever the case, about 1330 on 20 November, CC3 struck northwest toward Mulhouse from Bartenheim. Encountering only scattered resistance, the armored task force achieved considerable surprise as leading units pushed into that portion of Mulhouse lying south of the Rhone–Rhine Canal. On the following day, the 21st, CC3 crossed the canal and cleared most of Mulhouse north of the waterway; but it was 25 November before the last Germans evacuated the city—the same day that the last Germans left Belfort.

Du Vigier’s other major unit also converged on Mulhouse. CC1, which could have swung eastward past the rear of CC3 on 20 November to initiate a drive toward Chalampe, instead headed for Altkirch, ten miles southwest of Mulhouse. By dark, leading elements were within three miles of Altkirch. After a sharp clash with 30th SS Division troops, the task force cleared the small city on the 21st and advanced four miles farther north along the Rhone–Rhine Canal to Illfurth.

The commitment of CC1 and CC3 at Altkirch and Mulhouse left only a

small 1st Armored Division element, Detachment Colonnier, along the Rhine. Consisting of an armored infantry company and a tank destroyer platoon, it nevertheless undertook the task of driving north to Chalampe and seizing the Chalampe rail and highway bridges across the Rhine. On 20 November Detachment Colonnier moved out from Kembs, four miles north of Rosenau; reached Hombourg, five miles farther north that afternoon; and arrived at the southern outskirts of Ottmarsheim, just three miles short of Chalampe, on the morning of the 21st. But, this was as close as any French formation would come to Chalampe for two and a half months. On 23 November German counterattacks forced the detachment to withdraw to the west side of the Harth forest between the Rhine and Mulhouse. Meanwhile, the Germans were able to retain and reinforce their west bank bridgeheads at Chalampe and Huningue and, in between, establish new bridgeheads at Rosenau, Loechle, and Kembs. De Lattre’s hopes for an early drive north up the Alsatian plains at least as far as Chalampe had begun to fade away and, given the First French Army’s limited strength along the Rhine, may not have had great potential anyway.

The German Counterattacks

The inability of du Vigier to secure the western banks of the Rhine between Chalampe and Huningue was undoubtedly disappointing for General de Lattre. However, the continued German resistance in the area southwest of Dannemarie and the failure of Bethouart to free the 5th Armored Division for the planned drive on Cernay must have been even more frustrating. Now, as the rest of the 198th Division and other reinforcing elements arrived, the French situation became more precarious. Perhaps inevitably, since it had been de Lattre’s forces that led off the 6th Army Group’s November offensive, it was these attacking forces that first captured the attention of the German high command and were now about to feel the consequences of their early success.

By 20 November, with the arrival of German reinforcements both north and south of the Rhone–Rhine Canal west of Dannemarie, Bethouart’s I Corps forces were unable to make any significant progress east of Morvillars. Now leading the corps’ attack in this area, the 1st Armored Division’s CC2 had been unable to advance over the canal or move along its southern side any farther than Brebotte and Vellescot. Thus, Task Force Miquel,20 leading the 5th Armored Division from Montbeliard east along N-463 to Delle and then north through Morvillars, soon learned that the division would have to fight its own way across the canal. By midmorning TF Miquel reached Brebotte, where the unit took over from elements of CC2 and managed to advance northeast another two miles, constantly under fire from German weapons north of the canal. Forward elements attempted to cross the canal, but were thrown back with heavy losses. This

Infantry-Tank Team of the 5th Armored Division, Belfort, November 1944

check left TF Miquel with its vehicles strung out back to Morvillars and then south on Route N-19A in the Allaine valley. Forward movement was further impeded by CC2 vehicles in the Brebotte area as well as by convoys bringing supplies up to CC2 and elements of the 9th Colonial Division. Behind TF Miquel, the 5th Armored Division’s next column, CC5, began just north of Delle and stretched back all the way to Montbeliard, where the 5th Division’s CC4 could not even move out of its assembly areas because of the crowded road conditions. Efforts to bypass roadbound units and push more strength up to the Brebotte–Vellescot area came to naught, for both wheeled and tracked vehicles quickly bogged down in rain-soaked terrain. Soon a large traffic jam twelve miles long blocked the narrow roads all the way back to Montbeliard, and the French were unable to untangle the confused situation for about thirty-six hours.

Late in the evening of 20 November de Lattre directed CC2 to move out of the Brebotte–Vellescot–Allaine valley area in order to give the 5th Armored Division room to maneuver its stalled components. De Lattre then wanted the 5th, with its two combat commands on line, to cross the Rhone–Rhine Canal, push one task force north toward Cernay, and swing the other eastward to seize Dannemarie, previously an objective of the 1st Armored Division. If the armored units were still unable to force their

way across the canal, de Lattre intended to make more changes in his plans, by having the 1st Armored Division strike out for Cernay from the Mulhouse area and by giving the 5th Armored Division the task of pushing north along the west bank of the Rhine to Chalampe. However, he realized that such a switch would absorb many precious hours, dangerously slowing the momentum of his attack. In either case the bulk of the 9th Colonial Division would have to protect the northern flank of I Corps’ penetration above Route N-463, leaving no more than one detached regiment to support a more determined advance north along the west bank of the Rhine.

Sorting out all of the involved units understandably proved difficult. Somehow, during the night of 20–21 November, CC2 extricated itself from the Brebotte–Vellescot area, backtracked through Delle, and began reassembling its components in the Waldighofen area on Route N-463 by noon of the 21st. Along the Rhone–Rhine Canal, however, CC5 of the 5th Armored Division, remained partially entangled in the traffic jam and could make no progress in either crossing the canal or advancing northeast toward Dannemarie. At the same time, CC4, under local orders to secure the Suarce area and then strike north for Dannemarie, bypassed the traffic jam and reached Delle about 0930, shortly after most of CC2 had passed through on its way to the Rhine. Events now took a turn for the worse, however, from the French point of view. At Delle, CC4 learned that the Germans were holding Suarce and had cut the vital Route N-463 near Courtelevant, behind CC2. The 1st Armored Division operating to the east was thus isolated, cut off from its sources of supply.21

With supply convoys of the 1st Armored Division and rear elements of CC2 already backed up at Delle, the arrival of CC4 created another traffic jam. But clearing N-463 east of Delle had immediate priority. Moving as fast as it could, CC4 managed to work its way around the confusion and overrun the German roadblock by noon. But at 1430 the Germans again cut the road, and CC4 was not able to reopen the highway until 1700. Meanwhile, elements of CC2 had returned from Waldighofen to help out near Courtelevant and to clear secondary supply routes south of N-463. Scattered German elements, however, continued to block the lesser roads below N-463, and the highway itself was still threatened by German forces operating in the forests north and south of the highway.

Redeploying part of CC2 to protect the supply routes heading east from Delle immobilized the rest of the combat command in the Waldighofen area. As a result, de Lattre’s efforts to push more French strength north up the west side of the Rhine River were again frustrated. He had hoped that CC2 could continue northward from Waldighofen to take over the task of securing the Mulhouse area while CC3 regrouped for the push northward. By dark on the 21st, however, his latest hopes for the seizure of the Chalampe bridges had evaporated in

the face of increasing German pressure.

Much of that pressure on 21 November came from the 198th Division, which, by the end of the day, had finished deploying its main body from Vellescot to Courtelevant.22 The 30th SS Division added some pressure in the Altkirch region and along the Largue valley north of Seppois. The following day, 22 November, Wiese of Nineteenth Army intended to push a large part of the 198th Division, reinforced by elements of the 654th Antitank Battalion, south to the Swiss border near Rechesy, a mile or so south of Courtelevant. Another force, built on elements of the 30th SS Division and the rest of the antitank battalion, was to strike south for Seppois and then continue south and southeast to help 198th Division units cut any secondary French supply routes south of N-463. Wiese hoped that the 106th Panzer Brigade, the 280th Assault Gun Battalion, and a Wehrkreis V infantry regiment would reach the Seppois sector during the day to assist.

On the morning of 22 November the 308th Grenadiers of the 198th Division, again cutting Route N-463, reached Rechesy and Pfetterhouse on the Swiss border, but French forces halted a northern thrust from Pfetterhouse to Seppois. Above Seppois the attack of the 30th SS Division came to a quick halt in the Largue valley a little over two miles north of Route N-463; to the west, French forces finally captured Suarce and pushed the Germans back several miles toward the canal and Dannemarie. Obviously the reinforcements that Wiese expected had not arrived at the 198th Division’s front.

Throughout the 22nd the Germans continued to threaten Route N-463 east of Courtelevant and blocked the highway intermittently, but at least one 1st Armored Division fuel convoy broke through to the east.23 The unstable situation along N-463 continued to stall traffic at the Delle bottleneck, however, and the one regiment of the 9th Colonial Division that was to have deployed to the Rhine could not move past Delle. Meanwhile, waiting at Mulhouse deep inside the German lines, CC3 had to bring in its outposts and reconnaissance units as German reinforcements, many of them crossing the Rhine over the Chalampe bridges, began moving toward the city.

During 23 November Wiese wanted the 198th Division to continue blocking Route N-463 as well as all secondary east-west roads in the area, moving some of its forces all the way down to the Swiss border.24 The Nineteenth Army commander expected that the 106th Panzer Brigade and the 280th Assault Gun Battalion would reach the 198th Division’s sector during the day, but he directed the 198th to move out on the 23rd without waiting for the armor to arrive. In addition, he ordered

the 30th SS Division, with elements of the 654th Antitank Battalion in support, to resume its attack southward against Seppois.

On 23 November it was the German deployments that were beset by confusion and disarray. North of Seppois, the 30th SS Division was again unable to make any progress south and instead had to pay considerable attention to the 1st Armored Division’s CC1, which had started to push west and north from Altkirch, heading for Dannemarie and threatening its rearward supply lines. To the south, the German counterattack reached its high point in the morning, when the 198th Division’s 308th Grenadiers established a strong roadblock on Route N-463 about two miles west of Seppois; secured most of the Rechesy–Pfetterhouse–Seppois road south of the main highway; and patrolled routes in and out of the Swiss border to the south. The regiment was clearly overextended, however, and could not be expected to hold these positions without reinforcement from German armor arriving that afternoon.

Again the German reinforcement effort was late, and the constant switching back and forth of units may have almost exhausted the Nineteenth Army’s staff and transportation capabilities. Transportation problems virtually halted the southward movement of the 280th Assault Gun Battalion, and confusion in the German high command prevented the 106th Panzer Brigade from reaching the critical area. Apparently, the armored brigade’s leading elements had moved over the Rhine River bridges at Chalampe and motored south, reaching Ottmarsheim on Route N-68 about 1000 on 23 November. There they prepared to move farther south along the Rhine and then directly west to assist the 198th Division. But as the panzer unit reached Ottmarsheim, Wiese informed Balck that other units had recaptured a key bridge across the Huningue Canal in the middle of the Harth forest about five miles east of Mulhouse. Acting on this information, Balck directed the 106th to cross the bridge, bypass Mulhouse on the east, and feint toward the area between Altkirch and Mulhouse. Then the brigade was to swing back to the Huningue Canal, turn south and then west to bypass Altkirch, and drive directly toward Seppois. The entire maneuver was exceedingly complicated, and Balck only made the situation worse by directing that the armored brigade be committed piecemeal as its various components reached the front. Instead of concentrating the tank brigade for a rapid, powerful thrust, Balck invited the unit’s destruction in detail.

Not surprisingly, the maneuver was a total failure. During the afternoon of 23 November, as the 106th Panzer Brigade moved toward Mulhouse reinforced by several weak infantry battalions, it ran up against units of the 1st Armored Division and quickly became engaged in a day-long armor duel with the French. The next morning, 24 November, the battle continued with CC2 plus the artillery of the 1st Armored Division repulsing a series of attacks by forces assigned or attached to the 106th in the area immediately east and southeast of Mulhouse. At the same time, French fire made it impossible for the German

brigade to move southward.

The lack of expected armored support sealed the fate of the 308th Grenadiers of the 198th Division. During the afternoon of 23 November, French units regained control of Route N-463 through Seppois, isolating the 308th Grenadiers from the rest of the 198th Division north of the highway; the next day French forces swept the Rechesy–Pfetterhouse area, destroying most of the regiment. What was left of the 308th—less than 300 troops—crossed the border into Switzerland to be interned. The French breakthrough at the Belfort Gap was now complete, and the German counterattack a failure.

The Belfort Gap Secured

When Bethouart’s I Corps initiated its drive through the Belfort Gap on 14 November, the immediate mission of de Monsabert’s II Corps was to maintain sufficient pressure across its mountainous front to keep some German attention focused on the High Vosges.25 On 15 November, at the request of VI Corps, the II Corps had mounted a limited attack on its left flank in conjunction with the 36th Division, pushing southeast through Le Tholy toward Gerardmer. The French effort, undertaken largely by FFI units attached to the 3rd Algerian Infantry Division, passed through Le Tholy and advanced along Route N-417; in doing so, the French discovered that the Germans had burned many hamlets and farms along the way. The diversionary effort had ended quickly around the 16th, but on 19 November the 3rd Algerian Division noticed that the 198th Division was pulling out of its lines and lost no time in following up. The left wing of the division reached destroyed Gerardmer, while five miles to the south other troops of the division entered burned-out La Bresse.

On the same day, 19 November, the 1st Infantry Division, on the II Corps’ right, or southern, wing, began a series of attacks to support the I Corps’ 2nd Moroccan Division, which was having considerable difficulty clearing the city of Belfort. Holding its position on the left in order to maintain contact with the 3rd Algerian Division, the 1st Division planned to push its center east along the axis of the Chevestraye Pass and Plancher-les-Mines toward Giromagny, on Route N-465 about eight miles north of Belfort. Its leading forces would then exploit seven miles farther east to Rougemont-le-Chateau and Masevaux, at the southern edge of the Vosges; meanwhile, the division’s right would push east from Ronchamp to seize Champagney and nearby high ground and then head generally east and northeast. The plan was, in effect, a modified revival of the attempt to outflank Belfort on the north that de Lattre had called off in mid-October.

The attack began on 19 November. In the center, the 1st Division found that the once-strong German defenses in the Chevestraye Pass area had been vacated, and the attackers pushed on to a ridge overlooking Plancher-les-Mines. On the right, Champagney,

where the French encountered extensive minefields and liberally sown booby traps, fell the same day with only spotty resistance, and troops of the 1st Division met elements of the 2nd Moroccan Division near the Champagney reservoir to the south.

The Moroccans, meanwhile, had penetrated farther into the city of Belfort and had slowly begun to eliminate the remaining German defenders. On the 20th, in order to allow the I Corps to concentrate on operations to the east, General de Lattre took direct command of the 2nd Moroccan Division and two days later passed control of the unit to de Monsabert.

While the 3rd Algerian and 2nd Moroccan Divisions progressed slowly in the northern and southern sectors of the widened II Corps zone, the 1st Infantry Division in the center continued to forge ahead and moved into Giromagny north of Belfort nearly unopposed on the 22nd. The division’s left flank then pressed toward the great bulk of the Ballon d’Alsace, six miles north of Giromagny, as the right, keeping in touch with the Moroccans to the south, reached Valdoie, two miles north of Belfort.

Impressed by the 1st Division’s progress and concerned over the German counterattacks south of the Rhone–Rhine Canal, de Lattre issued new orders on 22 November, calling for a general exploitation across the First French Army’s entire front. Bethouart’s I Corps was to advance north and de Monsabert’s II Corps move generally east, thereby squeezing the German forces in the middle. A northern advance in strength to Mulhouse, which was already in French hands, would obviously threaten the rear of the German counterattacking forces around Dannemarie, as well as those defending along the Rhone–Rhine Canal to the west. Each side would thus be attempting to attack the rear of the other.

De Lattre’s new orders called for the II Corps to push its center through Rougemont-le-Chateau and drive for Burnhaupt on the Doller River. The Moroccans on the corps’ right would secure Belfort, and the Algerians on the left would push east across the Vosges through the Bussang and Schlucht passes. This accomplished, de Monsabert’s forces were to take Cernay, ten miles west of Mulhouse, and join Bethouart’s I Corps forces, now reinforced by the rest of the 4th Moroccan Mountain Division from the Italian Alpine front. The two corps would then begin a concentrated push north to Colmar and eventually Strasbourg, thus liberating all of Alsace.26

On 23 and 24 November the 1st Infantry Division again made significant progress, reaching the crest of the Ballon d’Alsace on the left, the outskirts of Sewen on the Doller River in the center, and a point just two miles short of Rougemont-le-Chateau on the right. Despite these gains, however, de Lattre decided on the 24th that his plans were too ambitious. In the Vosges, the 3rd Algerian Division continued to meet determined German resistance and made little progress; on the corps’ right the 2nd Moroccan Division remained stalled by some German-held strongpoints in and

around Belfort. To the east, I Corps faced steadily increasing German pressure in the Mulhouse region, while the 198th Division, now with some armored support, still had sufficient strength north of Route N-463 to threaten I Corps’ main supply route in the Courtelevant–Seppois area. Also influencing his thoughts was the imminent loss of the 1st Division, which would be pulled out of its lines within a few days to redeploy to the Atlantic coast for Operation INDEPENDENCE.27 The 2nd Moroccan Division (plus CC6) and the 3rd Algerian Division would then have to take over the 1st Division’s sector, greatly diluting the combat strength of the II Corps. Finally, de Lattre had to take into consideration the losses of men and equipment that the First French Army had suffered over the past ten days (14–24 November) as well as his declining stocks of ammunition, fuel, and other supplies.

Recognizing the limitations of his strength and realizing that a major operation to clear all of Alsace was at least temporarily out of the question, de Lattre issued new orders on the 24th outlining a more conservative plan.28 The primary objectives of the revised plan were securing the entire Belfort Gap area and destroying the remaining forces of the LXIII Corps as far north as the Doller River—roughly the region south of Sewen, Masevaux, Burnhaupt, and Mulhouse. For this purpose de Lattre’s orders called for a double envelopment by the I and II Corps, with the pincers to close at Burnhaupt. Bethouart’s I Corps, holding firmly at Mulhouse, was to push part of its strength west from Mulhouse and northwest from Altkirch toward Burnhaupt, and de Monsabert’s II Corps was to strike for Burnhaupt from the west. In the II Corps’ sector the main effort would have to be made by the 2nd Moroccan Division and its attached CC6, but de Monsabert intended to keep the 1st Infantry Division in the line pushing eastward as long as possible.

At dawn on 25 November de Monsabert’s forces were surprised to find that the German troops facing them in the gap area had withdrawn during the night, and both the 1st Infantry and 2nd Moroccan Division immediately accelerated their drives east. On that day the 1st Division pushed to within half a mile of strongly defended Masevaux; to the south, the Moroccans were not even able to regain contact with the retreating Germans. On the other hand, de Monsabert realized that the Germans were probably trying to build up some sort of defensive line along the trace of the Doller River in order to hold up the French advance and extract their remaining forces from the Dannemarie–Suarce area. Both he and Bethouart would have to move their forces as rapidly as possible if their trap was to close before the Germans could escape.

De Lattre received a needed boost on the 26th when General Devers announced yet another postponement of First French Army redeployments

French troops raise Tricolor over Chateau de Belfort, November 1944

for INDEPENDENCE. Now the 1st Infantry Division would not have to be pulled out of the lines and reassembled until 2 December, and the 1st Armored Division not until the 5th.29 This delay enabled both French corps to resume their envelopments with confidence, and on the afternoon of 28 November, after much bitter fighting, the pincers closed at Burnhaupt.

The completion of de Lattre’s “Burnhaupt Maneuver” marked the end of the First French Army’s November offensive. By seizing both Belfort and Mulhouse, the French had completely outflanked the German defenses in the Vosges Mountains and, in the process, further eroded the German forces facing the 6th Army Group. The Burnhaupt Maneuver, taking place from 25 through 28 November, had bagged some 10,000 German prisoners, most of them from the LXIII Corps, which had lost at least another 5,000 prisoners earlier during the period 14–24 November.30 However, French manpower losses from 14 through 28 November were also serious and numbered 1,300 killed, 4,500 wounded, 140 missing, and over 4,500 nonbattle casualties. French matériel losses included about 55 medium tanks, 15 light tanks, 15 tank destroyers, 15 armored cars, and 50 half-tracks, while many more combat vehicles had been damaged, and all were in need of overhaul. Moreover, the task of clearing all of upper Alsace was only half completed.

De Lattre’s inability to achieve all his objectives reflected some of the inherent weaknesses of his army. Although de Lattre himself had personally supervised the actions of both corps, giving de Monsabert and Bethouart considerably less freedom than Patch had afforded Truscott, Haislip, and Brooks, his span of control was limited, especially as the advance began to stretch French staff and communications capabilities thin. In addition, many of his key units, such as the 5th Armored Division, were relatively inexperienced, and many of

his infantry units were made up of recently recruited soldiers with little more than the rudiments of military training. The trained military technicians necessary to fill out the First French Army’s ordnance, signal, engineer, and other support units were in extremely short supply, making it difficult for French forces to sustain an extended armywide battle for any length of time. The projected losses to support Operation INDEPENDENCE were another major factor that hampered French planning, causing confusion and hesitation. Thus, although de Lattre was unable to drive all the way up the Rhine valley, he probably did the best anyone could have with his existing resources and constraints. In this respect, Wiese’s insistence that the 198th Division be brought south and deployed as quickly as possible across the 1st Armored Division’s line of communications probably saved the day for the Nineteenth Army. However, given the confusing orders from Balck, the Germans were fortunate not to have suffered even heavier losses in the Belfort Gap.

Whether an early seizure of the Chalampe bridges would have affected the situation is moot. French control of Chalampe might have left Mulhouse in German hands and stretched du Vigier’s slender supply lines even thinner. A stronger drive north along the Rhine might also have made it easier for Wiese, if he had the nerve, to concentrate the 198th Division and other early reinforcements for a more intensive counterattack south of Dannemarie, obviously with undesirable consequences for du Vigier’s armor. The arrival of reinforcements such as the 106th Panzer Brigade might have been delayed if they were forced to cross the Rhine north of Chalampe, but the lag would have been of no consequence. In short, the German infantry counterattack south of Dannemarie, which temporarily interdicted the French 1st Armored Division’s supply lines, was the primary factor behind de Lattre’s inability to project more strength along the Rhine throughout the offensive.

The end of the battle on 28 November saw the French consolidating their gains in and around Belfort, while the Germans continued to pressure I Corps units in the Mulhouse area and in the region between Mulhouse and the Rhine, building up new defenses along the line of the Doller River west of Mulhouse and holding tenaciously to the mountainous terrain north of Masevaux. Although Wiese still controlled a large portion of the Alsatian plains in the region around Colmar, General Devers now believed that those units of the Nineteenth Army still west of the Rhine would soon withdraw across the river. Furthermore, he estimated that once the forces of the First French Army had caught their breath, they would be able to police up the rest of the German troops between Mulhouse and Strasbourg, with the help perhaps of one or two American divisions. However, considering the winter weather and the exhaustion of his own troops and supplies, de Lattre was by no means so hopeful.