Chapter 26: On the Siegfried Line

The opening days of December 1944 found General Devers increasingly disturbed over the Seventh Army’s slow progress northward as well as the even slower advance of both the Seventh and the First French Armies toward the city of Colmar.1 After conferring with General de Lattre on 1 December, Devers once again postponed French redeployments for Operation INDEPENDENCE, thereby hoping to accelerate the elimination of the Colmar Pocket. Now the French 1st Infantry Division was to start westward on 9 December instead of the 7th, and the French 1st Armored Division on the 17th instead of the 10th. For similar reasons the 6th Army Group commander decided to transfer operational control of the U.S. 36th Infantry Division and the French 2nd Armored Division from the Seventh to the First French Army, effective 5 December. As a corollary, Devers also moved the boundary between the two armies north to Plobsheim, seven miles below Strasbourg. These changes relieved both Patch and Brooks of any further responsibility for the Colmar area, although the Seventh Army continued to provide logistical support for the two transferred divisions. With these reinforcements and the continued deferral of Operation INDEPENDENCE, Devers wanted the First French Army to renew its offensive as soon as possible and finish the job of clearing southern Alsace.

Having presumably settled matters concerning the Colmar Pocket and INDEPENDENCE, General Devers turned his attention to the Seventh Army’s attack northward. At its current rate of advance, Haislip’s XV Corps would be unable to protect and support the right of Patton’s Third Army. In fact, by 2 December, the 4th Armored Division of the Third Army’s XII Corps was already waiting impatiently for the XV Corps’ 44th Division to come up on its right before continuing its advance northward.2 To speed up the advance of the 44th and his other forces toward the German border and

Brig. Gen. Albert C. Smith

the West Wall, Devers estimated that he would need the full power of Patch’s Seventh Army, including both the XV and VI Corps, and on 2 December he issued orders to that effect.

With Devers’ instructions in hand, Patch quickly published implementing directives the same day, outlining new corps boundaries, deployments, and missions. Brooks’ VI Corps was to move north and position itself to the right of Haislip’s XV Corps. The new boundary between XV and VI Corps would run from the vicinity of Saverne north and northeast along the crest of the Low Vosges Mountains, which was essentially the same boundary that Haislip had previously established between the 100th and 45th Divisions. West of the new boundary the XV Corps, now consisting of the 44th and 100th Infantry Divisions, would continue the attack northward on a narrower sector approximately ten to fifteen miles wide. To the east, the VI Corps would push northward across a much broader front of about thirty miles with the 45th, 79th, and 103rd Infantry Divisions, leaving the 3rd Division behind to secure the Strasbourg area. To strengthen the offensives of both corps, Patch gave each an armored division: the 14th Armored Division, now united under Brig. Gen. Albert C. Smith, went to Brooks; and a fresh unit, the recently arrived 12th Armored Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Roderick R. Allen, went to Haislip. In addition, Devers wanted to have elements of the new 42nd, 63rd, and 70th Infantry Divisions, scheduled to begin disembarking at Marseille in early December, brought north as quickly as possible relieving the 3rd Division of its static mission and making another experienced division available for the drive north.

A final arrangement involved the XV Corps’ new 12th Armored Division. As December opened, General Eddy, the XII Corps commander, informed General Patton, in charge of the Third Army, that the worn 4th Armored Division was no longer capable of making any substantive contribution to XII Corps operations, and suggested that Haislip’s XV Corps, with a much narrower front, could spare a division to relieve the tired unit temporarily. The 12th Armored Division was the obvious candidate for the proposed substitution.

Maj. Gen. Roderick R. Allen

Patton put the question to Patch, who agreed in principle, but was understandably reluctant to lose control of the unit. However, Devers, Patch, and Haislip realized that the proposition was sensible. The 12th Armored Division would find the hilly but generally open terrain of the 4th Armored Division’s sector more suitable than the rough, forested ground of the Low Vosges over which the XV Corps infantry divisions were advancing. Moving slightly to the west, the new armored division would have a much easier time breaking in its various components, while giving the 4th Armored Division—which had given a good account of itself earlier during the Panzer Lehr Division’s counterattack against the XV Corps—a well-earned rest. In the end, the involved commanders worked out a compromise: the 12th Armored would move into the XII Corps’ sector to relieve the 4th, but would not pass to General Eddy’s command and instead would remain under General Haislip’s “tactical control.” Subsequently CCA of the 12th Armored Division began relieving forward elements of the 4th Armored on the morning of 7 December, and the last of its units were out of the line by evening of the next day.3

The German Situation

While the Seventh Army was reorganizing for its December offensive, Army Group G and the First Army were taking what measures they could to halt or at least delay the advance of the Third and Seventh Armies to the West Wall.4 As December opened, leadership and morale within the First Army was low. What had once been considered an excellent organization had fallen on hard times. Both von Rundstedt at OB West and Balck at Army Group G felt that the headquarters had developed a withdrawal psychosis; at the same time, its units had run up a sobering total of defections, desertions, and surrenders in the face of continuous pressure from the American Third and Seventh Armies. Furthermore, von Rundstedt and

Balck were increasingly dissatisfied with the conduct of the First Army’s commander, General von Knobelsdorff, and a series of events soon resulted in his relief. On 1 December von Rundstedt warned Balck that Army Group G would have to redeploy even more units to Army Group B for the Ardennes offensive, specifically the Panzer Lehr Division, 11th Panzer Division, and the 401st and 404th Volks Artillery Corps—all First Army units. After learning of the impending transfers, von Knobelsdorff informed Balck that he could not accept responsibility for stabilizing his front if these forces were withdrawn, nor could he hold his section of the West Wall with the forces that would remain. The following morning, 2 December, von Knobelsdorff reported being ill, and von Rundstedt immediately replaced him with Lt. Gen. Hans von Obstfelder.

Von Obstfelder took command of a rather demoralized army that consisted of three corps: the LXXXII on the far right, or west; the XIII SS in the center, with its southeastern flank in the vicinity of Sarre-Union; and the LXXXIX Corps, which occupied a front of over forty-five linear miles from Sarre-Union east to the Rhine. The LXXXII Corps and the XIII SS Corps faced Patton’s Third Army, as did LXXXIX Corps units in the Sarre-Union area, while the rest of the LXXXIX Corps held the German front opposite the Seventh Army.

During the first week of December the German high command made several changes in these arrangements. First, von Obstfelder moved the right, or western, boundary of the LXXXIX Corps east to Bitche, thereby narrowing the corps front by about ten miles. Next, von Rundstedt decided to transfer the XC Corps headquarters from the Nineteenth Army’s center to the First Army, inserting it between the XIII SS and the LXXXIX Corps; initially the transferred corps would control little more than the 25th Panzer Grenadier Division. This action ultimately pushed the LXXXIX Corps’ western boundary farther east to the Camp de Bitche, a large prewar French Army installation.5 For the Seventh Army, these boundary adjustments meant that Haislip’s XV Corps would face both Petersen’s XC and Hoehne’s LXXXIX Corps, while, from the crest of the Low Vosges east to the Rhine, Brooks’ VI Corps would meet only LXXXIX Corps forces.

Increasingly concerned over American advances east of the Low Vosges and apparently doubting the ability of First Army headquarters to supervise and coordinate the operations of four corps, von Rundstedt, on 8 December, raised the LXXXIX Corps headquarters to the status of an independent command, directly under Balck’s Army Group G and on the same echelon as the First and Nineteenth Army headquarters. Designated Group Hoehne, the new command consisted mainly of the 361st, 245th, and 256th Volksgrenadier Divisions and had an effective strength of about 9,000 troops, of which some 5,500 could be considered infantry combat effectives. On 8 December Group Hoehne also picked up Division Raessler and the 21st Panzer Division. The panzer division

was greatly understrength at the time, with no more than 2,200 combat effectives, and would need several days to redeploy to Hoehne’s sector. Division Raessler, with about 4,700 troops, was responsible for preparing the West Wall defenses in Group Hoehne’s sector; however, a standing directive from Hitler forbade the employment of any West Wall troops forward of the fortification line, so the acquisition was of no immediate advantage.

Both General Hoehne and his neighbor, General Petersen, had the mission of holding the area in front of the West Wall until 16 December, the scheduled date for the start of the Ardennes offensive. While accomplishing this task, Balck also instructed both commanders to preserve the integrity of their units so that they could fall back on the West Wall reasonably intact and contribute to its defense. Von Rundstedt agreed to this additional guidance, but made it clear to all concerned that the West Wall was to be a final line from which no further German withdrawals could be countenanced.

The XV Corps Offensive North

Late on 4 December, as the reorganized XV Corps prepared to continue its drive north, the German forces in front of Haislip’s command began a limited withdrawal. As a result, the XV Corps’ attack on the 5th at first encountered little resistance. Quickly elements of the 100th Division’s 397th and 398th Infantry regiments cleared the Wingen–Ingwiller section of Route N-419 through the Low Vosges, thus placing the entire east-west mountain road under American control (Map 32). On the corps’ left, the 44th Division’s 324th and 114th Infantry secured the Ratzwiller area on the 5th and seized Montbronn on the 6th. Although operating in more rugged and more forested terrain, the 100th Division easily kept pace, moving up from N-419 to the area east of Montbronn and occupying Mouterhouse, all against negligible German resistance. The 106th Cavalry Group, meanwhile, initiated an extensive mountain patrolling program east of the 100th Division to protect XV Corps’ right flank.

The initial gains of 5 and 6 December made Haislip optimistic, and he urged both divisions to push on rapidly to their current objectives: Siersthal and nearby high ground for the 44th Division, and Bitche and associated fortifications for the 100th. The divisions would then drive on to “develop” the German West Wall defenses.6 At the time, forward elements of the 44th Division were only four miles short of Siersthal, and the leading 100th Division units were about the same distance from Bitche. Haislip also expected that operations by the fresh 12th Armored Division on the XV Corps’ left, or western, flank would assist the advance of both units.

On 7 December, however, the German defenses in front of Haislip’s two divisions suddenly became more active. Infantry resistance stiffened markedly, and advancing American troops came under heavy and accurate mortar and artillery fire, which forced several local withdrawals. Delaying

Map 32: Seventh Army Advance to the German Border, 5–20 December 1944

German forces clung to hamlets and towns and turned isolated stone farmhouses into minor strongholds that slowed American progress. The retreating units had destroyed or damaged all bridges, left craters in roads, and blocked almost all routes of advance with booby traps and mines including many made of plastic and clay, which the American troops found hard to detect. The terrain, especially in the 100th Division’s sector, became more rugged as the advance moved north, and its difficulty was increased by hasty field fortifications that went up wherever the Germans chose to make a stand. Rain, fog, and occasionally snow and ice now added to the discomfort of the XV Corps’ infantrymen, while the heavily overcast skies continued to limit air support. From 5 to 20 December the XII Tactical Air Force supporting the 6th Army Group was able to provide significant air support on only four days, and on three of those days poor visibility curtailed the planned missions.

On the same day that German resistance stiffened, the 12th Armored Division’s CCA moved into forward positions west of Ratzwiller and, on the 9th, launched an attack over open terrain toward Singling and Rohrbach near the 6th Army Group boundary. Passing through undefended or lightly manned Maginot Line positions, the American armor secured Singling on 9 December and Rohrbach on the 10th and then continued to push northward. Above Rohrbach, however, mines and later accurate German antitank fire and armored counterattacks halted CCA on the 10th and 11th, forcing several withdrawals. This series of actions cost the 23rd Tank Battalion eight medium tanks as well as many casualties, including the life of its commander, Lt. Col. Montgomery C. Meigs.7 Like the 14th Armored Division, the 12th was acquiring its experience the hard way.

On 12 December the German forces facing the 12th Armored Division, apparently exhausted, withdrew, and CCA, now reinforced by CCR, had little trouble consolidating its previous gains. On 16 December the XII Corps’ veteran 80th Infantry Division began taking over the 12th Armored Division’s sector, and on the 17th the armored division reverted to XV Corps reserve. The division’s introduction to combat between 7 and 15 December had cost approximately 5 officers and 40 enlisted men killed and 15 officers and 140 enlisted men wounded.

While Allen’s 12th Armored Division was operating in the Rohrbach area, Spragins’ 44th Division took another five hard days—7 through 11 December—to battle its way northward to Siersthal. This town finally fell to the 71st Infantry late on the 11th, just as the 324th Infantry was coming up on the west between Siersthal and Rohrbach. But on the XV Corps’ right, the 100th Division, fighting its way across rough, forested country, found the going tougher; at dusk on the 11th it was still over two miles short of Bitche.

Commanding Generals contemplate the next move. Generals Allen and Spragins are on the left.

The Fortresses of Bitche

The capture of Siersthal opened a potential route, through the valley of the Schwalb River, bypassing the German-held Maginot Line installations in the Bitche area on the west. By the end of 11 December, however, it was evident that the Germans had chosen to hold the forts around Bitche, threatening the flank of any American advance that ignored these strongholds. Reluctantly, Haislip thus ordered both of his infantry divisions to prepare assault operations against the western and central fortresses. Both he and his division commanders hoped that the Germans would not defend the fortresses in any great strength and would abandon the area after only token resistance.

In deciding to make a stand at the Ensemble de Bitche, the Germans had chosen well. Unlike most Maginot Line forts, which were positioned primarily against attacks from the north and east, many of the installations in the Bitche area could also defend and fire effectively against an assault from the south. The Ensemble stretched eastward about eight miles from the vicinity of Hottviller past Bitche and the Camp de Bitche to Fort Grand Hohekirkel. The major works lay on rising ground north of Route D-35, the east-west road running through the valley in which the town of Bitche was located.

Westernmost of the larger fortifications was Fort Simserhof with ten separate fortified complexes, or “units,” all situated on commanding ground south of Hottviller and approximately two miles north of Route D-35. About a mile and a half east of Simserhof was Fort Schiesseck with eleven units, the most extensive of all Bitche area installations; just on the south side of D-35 from Fort Schiesseck was the much smaller Fort Freudenberg, with only a single major unit. Another mile and a half east of Schiesseck and centered half a mile north of Bitche spread Fort Otterbiel with four or five larger units; and, continuing east, several rather isolated installations dominated Route D-35 for the two miles between Bitche and the Camp de Bitche. The Ensemble ended in the east with Fort Grand Hohekirkel, which had five major units all located about a mile east of the Camp de Bitche.

The units of the main installations were each formidable fortifications built of reinforced concrete, with walls and overheads that were three to ten feet thick. Some had as many as five underground levels, while others had no ground-level entrances and could be reached only through long tunnels. Barbed-wire entanglements surrounded most of the fortifications, supplemented by elaborate antitank obstacles. Most of the installations were mutually supporting and provided broad, clear fields of fire in all directions. Gaps between the major units were covered by hasty field fortifications, and many of the German troops initially occupied such positions rather than the interiors of the larger installations.

The Germans were able to employ some French artillery, including a few disappearing guns, while German field artillery and mortars emplaced north of the fortresses added to the defense. Although the latter could be neutralized by counterbattery fire, American artillery, up to 8-inch and 240-mm., would find the fortifications themselves nearly impervious except at entrances, escape hatches, and open gun emplacements; the ordnance delivered by XII Tactical Air Force fighter-bombers would fare no better. In the end, the reduction of the massive forts would depend largely on teams of infantry and combat engineers.

The XC Corps’ 25th Panzer Grenadier Division was responsible for defending Forts Simserhof, Schiesseck, and Otterbiel, and Group Hoehne’s 361st Volksgrenadier Division for Fort Grand Hohekirkel and the installations in the Camp de Bitche area. However, with the rapid changes in the German boundaries during this period, many of the troop reassignments could not be put into effect before the American attack, and the defensive responsibilities for the central fortresses were somewhat blurred.

From the American point of view, the lay of the land and the positioning of the major installations dictated that the Ensemble de Bitche forts should be taken out sequentially, from west to east. Thus, on 13 December the 44th Division led off the XV Corps’ effort with an attack on Fort Simserhof, the westernmost fortification. While the 71st Infantry made the main assault from the Holbach area south of the installation, General Spragins sent the 324th Infantry

71st Regiment, 44th Division, Fort Simserhof, November 1944

east across the Schwalb River to seize high ground north of the fort in the vicinity of Hottviller in order to secure the flank of the attack. The 324th’s effort met little opposition, but the 71st Infantry’s advance on the fort proved painfully slow. On the left, the 71st was subject to intense German artillery and mortar fire; on the right, a German counterattack from the Freudenberg Farm area, half a mile west of Fort Freudenberg, frustrated attempts by the regiment to outflank Simserhof on the east. The 44th Division ended the first day of the assault with little to show for its efforts.

On 14 December the 71st Infantry regained some lost ground and secured Freudenberg Farm. In addition, the regiment captured some minor positions between Forts Simserhof and Schiesseck and, reinforced with combat engineers, began pushing northward in another attempt to invest Simserhof on the east. Progress, however, was again slow. During the next four days, 14 through 18 December, Spragins put all the artillery, tank, and tank destroyer fire that he could marshal against the major installations of Simserhof, while the 71st, fighting off numerous small counterattacks, focused its infantry-engineer assault teams against the fort’s ammunition and personnel entrances, which were all about 1,500 yards south of the main units. By evening of the 17th, troops of the 71st Infantry, with engineer

support, had entered the underground portions of Simserhof, while other elements of the regiment on the surface had penetrated a number of the strongest fortifications. On the morning of 19 December, the 71st launched a final attack to clear the last Germans from the installations, only to find that the remaining defenders had withdrawn northward during the night. On the same day, the 44th Division’s 114th regiment moved into the town of Hottviller without opposition. With the fall of Simserhof and Hottviller, the division began regrouping for an attack north to the West Wall, gratefully leaving the rest of the Ensemble de Bitche to the 100th Division.

On 14 December General Burress, commanding the 100th Infantry Division, had sent the 398th Infantry directly toward Forts Freudenberg and Schiesseck without any extensive preliminary bombardment, about the same time that the 44th Division was beginning to invest Simserhof. Like the 71st Infantry, the 398th quickly learned that the Germans intended to present more than token resistance. Moving north out of the wooded hills south of Bitche and Route D-35, the advancing American infantry was met by accurate artillery fire from both Forts Schiesseck and Otterbiel and was forced to pull back almost immediately. Burress then brought up his corps and division artillery, including some heavy 240-mm. pieces, to begin a two-day bombardment, supplemented when possible by air strikes. Although a later investigation would show that the firepower exercise caused no significant damage to the installations themselves (the French had built well), it did appear to shake the morale of the defenders. Equally important, Burress’ infantry commanders used the two days to plan their approaches to the fortifications more carefully.

Resuming the attack on 17 December, the 398th Infantry recaptured small Fort Freudenberg8 and secured the two southern entrances to Fort Schiesseck. The strong German opposition lessened somewhat on the 18th, allowing the 398th Infantry, with engineer support, to begin closing on the main units of the fort. As each unit was reached, infantry-engineer teams engaged any Germans remaining on the ground level, and then dropped explosives down elevator shafts, stairwells, and ventilating conduits to isolate the lower levels. The American troops generally made no attempt to descend into the depths of the fortifications, satisfied with sealing off the lower sections of each installation and interring any Germans that remained.

On 20 December the 398th secured the last of Fort Schiesseck’s eleven major units, and the regiment, with the rest of the Century Division, prepared to push on toward the German border, roughly eight miles north of Bitche. A few forces stayed behind in the Simserhof–Schiesseck area to protect the division’s right flank. Bitche itself remained in German hands, as did Forts Otterbiel and Grand Hohekirkel and the entire Camp de Bitche area. Haislip may have hoped that the

Germans occupying the Ensemble de Bitche would leave once they were no longer in a position to delay his advance to the West Wall and their own escape routes to the north were threatened. Unknown to the XV Corps commanders, events occurring outside of their area of operation had already made the question academic.

The 398th Infantry’s operations against the Ensemble de Bitche from 14 through 20 December cost the regiment approximately fifteen men killed and eighty wounded; the low casualties stemmed in part from the decision to use firepower instead of potentially costly infantry assaults against the prepared positions. Heavy artillery and air bombardments, supplemented as often as possible by direct tank and tank destroyer fire, at least kept the German defenders under cover, unable to man weapons or maneuver above the ground, and allowed American infantry and engineers to infiltrate the approaches to the individual blockhouses in order to do their work.

Of at least equal importance was von Rundstedt’s guidance to the field commanders directing the defense of the Bitche area: to prepare to withdraw to the West Wall once the Ardennes offensive was under way and to preserve unit integrity during that withdrawal. Both Generals Petersen and Hoehne thus regarded the Ensemble de Bitche as no more than a delaying position. Had they manned these installations with greater strength, the seizure of Simserhof and Schiesseck would have been a much more expensive affair for the American forces.

The VI Corps Offensive North

On 5 December General Brooks, the VI Corps commander, assumed operational control of the 45th and 79th Infantry Divisions, which were spread across a front of about thirty miles from the Low Vosges to the Rhine. During the following days he bolstered these units with the 14th Armored and 103rd Infantry Divisions, inserting the 103rd between the 45th and 79th and assembling the 14th Armored in the rear, ready to move up on command. Temporarily O’Daniel’s 3rd Infantry Division, still assigned to the VI Corps, would remain around Strasbourg.

Brooks’ offensive plans called for the 103rd and 79th Divisions to undertake the main effort in the strengthened Seventh Army drive north to the West Wall.9 Wyche’s 79th, on the corps’ right, or eastern, sector, was initially to lead the main attack, moving north up the right bank of the Rhine with Haffner’s 103rd on its left. The 79th Division was to attack on 9 December, and the 103rd Division on the 10th. When Brooks decided the time was right, Smith’s 14th Armored Division would pass through the 103rd and head for Wissembourg, about seventeen miles north of Haguenau. There the armored division would secure crossings over the Lauter River, which marked the German border in the Wissembourg area, and prepare to exploit northward through the West Wall.

The 45th Division, in a supporting role, would conduct limited objective

attacks on the VI Corps’ left wing until 10 December; it would then strike northeast from the vicinity of Niederbronn-les-Bains, the division’s current objective, to support the main effort. The 45th would have a new commander for the December offensive. General Eagles had been wounded on 30 November when his jeep hit a mine, and Maj. Gen. Robert T. Frederick, formerly the commander of the 1st Airborne Task Force, took command of the division on 4 December.

The VI Corps confronted the bulk of Group Hoehne’s forces. On General Hoehne’s right, or western, sector the 361st Volksgrenadier Division held the Low Vosges area from the Camp de Bitche southeast about twelve miles to the vicinity of Niederbronn-les-Bains.10 The weak 245th Volksgrenadier Division occupied the zone from Niederbronn southeast about ten miles to the Moder River at Schweighausen, covering a gap of generally open, rolling ground between the Low Vosges and the Haguenau forest. The sector from Schweighausen to the Rhine, over fifteen miles, was the responsibility of the stronger 256th Volksgrenadier Division.

In preparation for the main series of attacks on 9 and 10 December, the 45th and 79th Divisions conducted several preliminary operations to secure their lines of departure. On 5 December the 45th Division’s three regiments continued their push up to the Niederbronn–Mertzwiller railway line, but progress was slow. The division’s axis of advance was beginning to take Frederick’s forces deep into the broadening Low Vosges Mountains, where heavily wooded hills and valleys channeled and constricted forward movement. Every village and hamlet became a German delaying position difficult to outflank; roadblocks, demolitions, and mines abounded; nearly every bridge was destroyed or damaged; and German artillery and mortar fire seemed to intensify with each step American troops took toward the West Wall. On the division’s right, the 180th regiment, still operating in reasonably open terrain, cleared most of Mertzwiller on the 5th; but the next day a German infantry-armor counterattack drove the Americans south, back across the Zintsel du Nord Brook, which bisected the town.11 The Germans chose not to follow up their success, and on 7 December a battalion of the 410th Infantry, 103rd Division, coming from the High Vosges front, relieved the 180th Infantry, thus allowing Frederick to pull the regiment back for the main attack three days away.

Meanwhile, the 45th Division’s 157th regiment was able to slowly outflank German defenses at Niederbronn on the west and north, and finally occupied the town on 9 December. However, the 179th regiment, in the division’s center, made little headway, and the area around Gundershoffen, between Niederbronn and Mertzwiller, remained in German

hands. Although it had defended its sector fairly well, the 245th Volksgrenadier Division, one of Group Hoehne’s weakest units, had taken severe losses from the continued 45th Division attacks and would have difficulty carrying on the fight.

The preparatory actions of the 79th Infantry Division were more crucial. Both Brooks and the division commander, General Wyche, were concerned with the corps’ right flank. As long as the Germans held the Gambsheim area on the west bank of the Rhine, Wyche felt obliged to secure the sector between Gries and Weyersheim with the 313th regiment and to post the attached 94th Cavalry Squadron below Weyersheim as well.12 In the south, the 117th Cavalry Squadron, temporarily attached to the 3rd Infantry Division, screened the Gambsheim area from La Wantzenau, just north of Strasbourg. This entire effort, all because of a small German bridgehead west of the Rhine, was absorbing too many units, and the 79th Division commander wanted Gambsheim secured before he moved his division north.

Wyche gave the task of clearing Gambsheim to the 94th Cavalry Squadron, which had been reinforced by a platoon of medium tanks, two companies of armored infantry, and a battery of 105-mm. self-propelled artillery. After a thirty-minute artillery preparation early on 7 December, the squadron attacked, at first meeting stiff resistance. Automatic weapons and well-directed mortar and artillery fire, some from positions east of the Rhine, slowed the light armor down somewhat, but by evening the leading cavalry units had reached the western edge of Gambsheim. The following day, 8 December, resistance faded. By noon, after twenty-five soldiers from the 256th Volksgrenadier Division surrendered, the 94th Cavalry cleared the town and surrounding area, thus ending the threat to the 79th Division’s flank and allowing Wyche to use all three of his infantry regiments for the main attack.

VI Corps Attacks (10–20 December)

For Brooks, the 79th Division’s initial assault across the Moder River and through Haguenau was the most critical phase of the offensive. A delay here would have repercussions all along the front, while a successful crossing could set a good pace for the entire advance. Located on VI Corps’ right wing, the 79th had two infantry regiments—the 315th and the 314th—facing the Haguenau area, west to east, and a third—the 313th—in reserve securing the division’s right flank. Initially Wyche planned to attack north on 9 December, directing his main effort east of Haguenau. He wanted his forces to cross the Moder River in the vicinity of Bischwiller, some four miles southeast of Haguenau, and then drive north for about fifteen miles to Seltz, a mile or so west of the Rhine. To screen the left flank of the projected Moder River crossing, he wanted to pull the entire 315th regiment out of his left wing and have it swing behind and through the 314th to seize Kaltenhouse, about two miles northwest of Bischwiller. To screen the right side,

he ordered the 94th Cavalry Squadron to advance northward from Gambsheim. The 313th regiment, currently in reserve, would undertake the main effort, striking north for the Moder River at Bischwiller, as the 314th moved up to the Moder around Haguenau, keeping the German defenders occupied and ready to reinforce any of the principal attacking forces on Wyche’s order.13

The 79th Division faced Group Hoehne’s 256th Volksgrenadier Division, which was understrength as well as weak in supporting armor, antitank weapons, and some type of artillery. Although it was occupying good defensive terrain and had been receiving some reinforcements from east of the Rhine, the 256th had no designated reserves, and Group Hoehne could supply none. Neither Brig. Gen. Gerhard Franz, commanding the 256th, nor Generals Hoehne and Balck expected the unit to hold back a general attack.

With the Gambsheim area secured by 8 December, the 79th Division launched its attack on the 9th as planned. The 256th Volksgrenadiers appeared to have concentrated their defenses around Haguenau, and the direction of the 79th Division’s main effort took them by surprise. Although the 314th reached the Moder only with great difficulty and the 315th was stopped about a mile short of Kaltenhouse, the advance of the 313th on Bischwiller was only lightly opposed. Striking north at 0645 without any preliminary artillery bombardment, the 313th managed to capture intact a major bridge over the Moder. By the end of the day the regiment had cleared Bischwiller, crossed the river, and pushed northward another mile.

The breakthrough at Bischwiller opened up many possibilities for Wyche. On 10 December, with the 314th and 315th Infantry still stalled in the Haguenau–Kaltenhouse area, Wyche had a battalion of the 315th sidestep to the east, cross the Moder at Bischwiller, then strike out west along the northern side of the Moder, hitting the German defenders on their flanks and occupying Camp d’Oberhoffen, a former French Army training center. Meanwhile the 313th Infantry consolidated its bridgehead and continued to push north, advancing to Schirrhein, four miles north of Bischwiller, while elements of the 94th Cavalry Squadron reached Herrlisheim, three miles north of Gambsheim, on the 79th Division’s right.

While German attention was focused on the Haguenau area, the 45th and 103rd Infantry Divisions began their offensives in the west. On 10 December the 157th Infantry, leading the 45th Division’s attack on the corps’ extreme left wing, gained over two miles north and northeast of Niederbronn, while the 180th Infantry, coming back into the line, passed through the 179th regiment to cross the railway line and Route N-62 at Gundershoffen, three miles south of Niederbronn. The 180th then swung off to the northeast as the 411th Infantry of the 103rd Division came up on its right to push two miles east of Gundershoffen against diminishing resistance. Another three miles to the south the 103rd Division’s 410th Infantry

313th Regiment, 79th Division, in the vicinity of Bischwiller. M5 Light tanks are on the road, December 1944

recaptured Mertzwiller after bitter house-to-house fighting, an action that included the recovery of about eighty men of the 180th Infantry who had been hiding out in the town since 6 December.

After Mertzwiller, the 410th advanced over a mile eastward into the western fringes of the vast Haguenau forest, which extended east about twenty miles. Laced by minor roads and logging trails, the forest lay on generally flat land cut by numerous small streams that in wet weather could severely curtail troop and vehicle movements. In addition there were several Maginot Line installations in the eastern third of the forest, and a determined German defense of the forest could have caused serious trouble. Now, however, the full weight of the VI Corps’ assault as well as the earlier offensives of the XV Corps began to have a decided effect on the weary German defenders, and by evening of the 10th the entire German line had begun to give way.

The attacks of the 45th and 103rd Divisions on 10 December had caught the weak 245th Volksgrenadier Division unprepared to conduct an organized defense, and by the end of the day the unit had begun to fall apart. Hoehne was quick to appreciate that its collapse would threaten the flanks of both his other divisions; as a partial remedy, he narrowed the 245th’s

sector somewhat, forcing the 256th to extend its right flank to the northwest. But with the continued penetration into the 256th Volksgrenadier Division’s front by the 79th Division along the Rhine, the measure was obviously unsatisfactory. Sometime that night, therefore, with the approval of Army Group G, Hoehne directed both the 245th and 256th to withdraw two to six miles north to a secondary defensive line. The new line was to begin at Nehwiller, a little over two miles east of Niederbronn, and extend twenty miles eastward to the Rhine at Fort Louis. The decision meant that Group Hoehne would abandon both Haguenau city and most of the Haguenau forest without further fighting, but given his strength as well as his instructions to preserve the integrity of his forces, General Hoehne felt that he had little choice. At Army Group G, General Balck reluctantly acquiesced to the withdrawal.

During 11 December all three of Brooks’ attacking infantry divisions made considerable progress. On the corps’ right, the 79th Division’s 314th regiment moved into Haguenau unopposed in the morning, and the 315th secured the area between Bischwiller and Haguenau, uncovering large stocks of unused German supplies and equipment in Camp d’Oberhoffen. Still pushing northward, the 313th Infantry met strong resistance at Soufflenheim, but reconnaissance patrols probing the eastern portion of the Haguenau forest detected no enemy presence. Along the Rhine other patrols advanced the lines three miles north from Herrlisheim. During the day most of the 94th Cavalry Squadron rejoined the 14th Armored Division, and the 117th Cavalry Squadron, with one troop of the 94th attached, took over the right flank security mission.14

In the west, the 157th Infantry, 45th Division, secured Nehwiller on 11 December against little opposition, breaking through Hoehne’s projected defensive line before it could be established. The 157th then pushed northeastward through the Low Vosges another mile or so, while the 180th Infantry, on the 45th Division’s right, gained about three miles. But the terrain facing the 45th was now becoming increasingly difficult. In the 103rd Division’s sector, the 411th and 409th Infantry advanced nearly three miles, piercing the planned German line near the road junction town of Woerth; on the division’s right, the 410th Infantry seized Walbourg on the northeastern border of the Haguenau forest. Neither of the two divisions encountered any significant German opposition.

On the 12th the German rout continued. In the Vosges the 45th Division seized Philippsbourg on the corps’ far left and outflanked a German strongpoint at Lembach, only about four miles short of the border. To the east the 103rd Division kept pace, reaching Surbourg on the northern edge of the Haguenau forest; along the Rhine, the 79th Division occupied Soufflenheim and advanced eight miles farther north to Niederroedern and Seltz. Wyche, the 79th Division commander, expected

German counterattacks from the eastern section of the Haguenau forest, but his patrols there found only damaged bridges, abandoned roadblocks, and empty Maginot Line installations. The 256th Volksgrenadier Division was no longer trying to contest his division’s advance.

By 12 December Brooks had become convinced that the Germans would not stand and fight, but would instead attempt a series of delaying actions as they fell slowly back to the German border and the West Wall. The cold weather plus the rain, rough terrain, demolitions, mines and roadblocks of all types, mortar and long-range artillery fire, and tactical supply problems were more responsible for retarding American progress than any ground combat action on the part of the Germans. As for Group Hoehne’s forces, 12 December was a disaster. Hoehne’s small staff was no longer able to keep pace with the tempo of changing events nor could it direct its subordinate units in any coherent manner. In the center the 245th Volksgrenadier Division finally collapsed, and the 256th along the Rhine was not in much better shape. Deep in the Vosges the failing 361st Volksgrenadiers, under increasing pressure from Haislip’s XV Corps around Bitche, could do little to assist their neighbors. Only the emergency arrival of the 192nd Panzer Grenadiers of the 21st Panzer Division forestalled a complete breakthrough in Hoehne’s front.

Drive to the West Wall

With the Germans reeling, Brooks was now ready to commit Smith’s 14th Armored Division. Believing that at best only a weak shell of defenders confronted his forces, he reviewed his plans for the commitment of the armored unit on the evening of the 12th. Originally he had intended to have the armored division pass through the 103rd Division and strike for Wissembourg. However, after the 256th Volksgrenadier Division put up a respectable defense in front of the 79th Division on 9 and 10 December, he considered passing the 14th Armored through the right flank of the 103rd, swinging it north of the Haguenau forest and east to the Rhine, thus striking the German defenses around Haguenau from the rear. However, with the 256th now rapidly retreating, Brooks decided to insert the 14th Armored Division between the 103rd and 79th Divisions. This action would allow both infantry divisions to concentrate on narrower fronts for a continuing push north and would provide the armored division with a sector of its own without masking the advance of the others. Brooks therefore directed the armored division to move up to the Haguenau forest area and attack northward at daylight on 13 December across a nine-mile-wide front between Surbourg and Niederroedern. Still aiming for Wissembourg, the division was to secure crossings over the Lauter River southeast of the town, while the 103rd and 79th Divisions, their sectors of advance substantially narrowed, would continue northward abreast of the armored forces to the German border.15 For the second

time since taking command of the VI Corps, General Brooks had ordered what amounted to a general pursuit.

Leading off for the 14th Armored Division on 13 December, CCB quickly reached Surbourg and then swung east six miles along the northern edge of the Haguenau forest to Hatten before encountering significant opposition. CCA followed CCB to Surbourg and continued northeast about two miles to Soultz-sous-Forets, where the armor linked up with the 103rd Division’s 409th Infantry coming in from the west. On 14 December CCA gained another five miles along the axis of Route N-63, the Haguenau–Wissembourg road, and wound up the day in a fire fight three miles south of Wissembourg. CCB, on the same day, pushed northeast seven miles from Hatten to Salmbach, about one mile short of the Lauter River and the German border. As armored patrols approached the small river, they found it flooded, measuring up to eighty feet across in some areas and not easily fordable.

Meanwhile, the VI Corps’ infantry divisions continued their steady advances during 13 and 14 December. On the 13th, the 79th Division resumed its drive northward just east of the armored division, clearing Seltz and Niederroedern after much house-to-house fighting; it then advanced another two miles north to Eberbach and reached the Lauter River near Scheibenhard and Lauterbourg on the 14th.

In the far west the 45th Division, struggling through the Low Vosges, finally took isolated Lembach and reached Wingen on 14 December. On its right flank, the 103rd Division continued northward, meeting heavy resistance at Climbach, a road junction town two miles east of Wingen. There the 3rd Platoon of Company C, 614th Tank Destroyer Battalion (towed), a black unit of a 411th Infantry task force, lost three of its four guns and suffered 50 percent casualties, but threw back a strong armor-supported counterattack by the 21st Panzer Division.16 Elsewhere the 103d’s advance met less resistance, and division elements reached Rott on the 13th and the Wissembourg area the following day.

Into Germany

By the morning of 15 December, Brooks’ VI Corps was ready to move across the German border in strength. In the broadening Low Vosges, the 45th and 103rd Infantry Divisions prepared to push through a rough, wooded axis of advance, five to six miles wide, with four regiments on line and two in reserve. In the VI Corps center, the 14th Armored Division concentrated against Wissembourg and Schleithal, aided by the right wing of the 103rd Division. To the east the 79th Infantry Division focused on Lauterbourg and the Lauter

River, still using armored cavalry units to screen its right flank on the Rhine. The final drive north would take all of the units directly into the vaunted West Wall, the defensive works that the German Army had been preparing for several months a few miles inside the German border.

Facing the center of the VI Corps was the weak 21st Panzer Division intermixed with remnants of the 245th Volksgrenadier Division and filled in here and there by yet a few more rear-echelon units turned infantry. To the west the 361st Volksgrenadier Division still had a precarious hold on its mountain defensive line from the Camp de Bitche to the area just northwest of Wingen; to the east the 256th Volksgrenadier Division was attempting to make a final delaying stand on the Lauter River. Meanwhile, behind all of Group Hoehne’s flagging forces, Division Raessler and the other designated fortress units were preparing to make their first defense of the West Wall.

During the morning of 15 December, the 14th Armored Division’s CCA cleared Riedseltz, but ran into intense artillery fire and a German tank-supported counterattack while attempting to move farther north, probably indicating the arrival of additional 21st Panzer Division units to reinforce the 256th Volksgrenadiers. CCA repulsed the assault, destroying two tanks, but gained little more ground. Elsewhere VI Corps units were at first more successful. Although harassed by artillery and mortar fire, the 45th Division’s 157th Infantry gained almost two miles of rugged terrain on the division’s left; meanwhile the 180th Infantry, more than keeping pace, reached the German border north of Wingen and at 1245 sent a patrol into Germany. On the 45th Division’s right, the 411th Infantry of the 103rd Division, after cleaning up the Climbach area, crossed the German border at 1305 and continued north. To the east, in the Lauter River area, the 79th Division’s 315th regiment cleared the southern half of Scheibenhard and sent patrols across the river into the German half of the town (Scheibenhardt). In the meantime, the 313th Infantry had come up on the right and, after more house-to-house fighting, had forced the Germans out of Lauterbourg, placing the southern bank of the Lauter firmly in the hands of the 79th Division.

By late afternoon of 15 December, VI Corps forces had thus reached or crossed the German border at half a dozen locations. At this point General Hoehne, having committed all his forces and realizing that a stand at the border itself was impossible, decided that the moment had finally come for a complete withdrawal into the West Wall defenses. Accordingly he informed Balck of his decision, emphasizing that an immediate withdrawal was necessary if he was to preserve the integrity of his remaining forces and use them to strengthen the fortified line. At Army Group G headquarters Balck had learned that the long-awaited Ardennes offensive was definitely to be launched on 16 December and concluded that Group Hoehne had fulfilled its stated mission: to hold in front of the West Wall until the Ardennes operation began. At 2045 on 15 December, he therefore approved the withdrawal of Group

Hoehne into the West Wall defenses.17

Balck’s decision was not well received at OB West. Von Rundstedt at first refused to condone the withdrawal and severely criticized Balck for the conduct of operations in Hoehne’s area. The field marshal wanted to halt the withdrawal, but Group Hoehne had already begun pulling back and there was little he could do to reverse the movement. Von Rundstedt insisted, however, that the 361st Volksgrenadier Division continue to hold across the Vosges and that the 25th Panzer Grenadier Division of XC Corps continue to defend the Maginot Line positions west of the Camp de Bitche where the XV Corps was attacking. Balck relayed these directives to Hoehne at midnight, allowing Group Hoehne to withdraw everything except the 361st Volksgrenadier Division, but warned him that the West Wall was to be the final German position—“there you die.”18

Between 16 and 20 December VI Corps units found that German resistance would slacken, but then stiffen remarkably as the units bumped into the West Wall defenses. In the Vosges the 45th Division seized the German mountain village of Nothweiller and the town of Bobenthal on the upper reaches of the Lauter River on the 16th, and reached Bundenthal and Nieder Schlettenbach a few miles farther north by 18 December. There its advance ended, and on the 18th and 19th German counterattacks and intense artillery and mortar fire forced a general withdrawal back across the Lauter. The experience of the 103rd Division was much the same. On the 14th Armored Division’s front in the VI Corps’ center, American armor occupied Wissembourg and Schleithal on the 16th and reached out to Schweighofen, a mile or so into Germany; but by the 19th Smith’s armored units were able to hang on to only a few precarious bridgeheads in the face of German counterattacks and increased artillery fire. In the east, combat engineers had erected some bridges over the Lauter unmolested, which allowed 79th Division units to push several miles into Germany, but this advance also stalled by the 19th.19 The VI Corps had now reached the outer works of the West Wall and would need a respite before attempting a major penetration of the somewhat overrated defensive line.

Stalemate at Colmar (5–20 December)

By 5 December General Devers had turned almost the entire Seventh Army north, still expecting that General de Lattre’s First French Army could finish off the Colmar Pocket assisted by Dahlquist’s 36th Infantry Division and Leclerc’s armor. At the time de Lattre assigned both units to the French II Corps, although they would still be supported logistically by the Seventh Army. Devers and de Lattre were accordingly surprised when the German defensive effort

Troops of the 45th Division make house-to-house search, Bobenthal, Germany, 1944

continued to solidify and, rather than meekly withdrawing across the Rhine, the Nineteenth Army held in place. Once again Wiese attempted to fill up the depleted combat battalions of his now ten infantry divisions20 with a variety of military personnel from all branches and services. On the 10th, Hitler’s determination to hold the trans-Rhine enclave was sharply underscored by the appointment of police chief Heinrich Himmler to oversee the task. Himmler was to command Army Group Oberrhein, a new headquarters controlling Wiese’s Nineteenth Army in the Colmar region as well as a mixture of defensive formations on the east bank of the Rhine south of Lauterbourg. Oberrhein would be a semi-independent headquarters and treated as a separate theater command; thus Himmler reported not to von Rundstedt’s OB West, but directly to OKW, and in practice answered only to Hitler himself. Himmler, in turn, replaced Wiese on 15 December with Lt. Gen. Siegfried Rasp, apparently finding the long-time commander of the Nineteenth Army less than enthusiastic regarding his new mission.

For the next few weeks the command changes proved effective. However questionable his military abilities, Himmler was able to accelerate the infusion of replacements into both the Colmar area and the east bank defenses by having the immediate German interior scoured more thoroughly for supplies, equipment, and manpower. In addition, the direct presence of the head of the dreaded secret police undoubtedly ensured that no unauthorized withdrawals occurred and inspired local German troop commanders to defend each village, water crossing, and road intersection more vigorously.

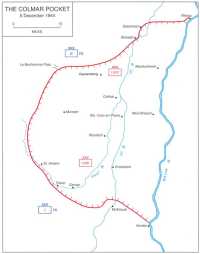

At the time of the VI Corps’ redeployment northward, its attacks in the north had reduced the base of the Colmar Pocket from about fifty to forty miles—from the town of Rhinau in the north to Kembs in the south—but the pocket still extended about thirty miles to the west, reaching the upper Thur River valley deep in the High Vosges (Map 33). On the southern border of the pocket, the Nineteenth Army had managed to secure the Harth forest area between Mulhouse and the Rhine and to form a solid defensive line from St. Amarin in the Vosges to Cernay and the Thur River. To the west, in the High Vosges, German units continued to defend the mountain passes in the area that once marked the gap between the First French and U.S. Seventh Armies. On the northern edge of the pocket, between Selestat and the Rhine, Wiese and his successor, Rasp, had gradually reinforced the area with mainly infantry units of all types, so that each Alsatian hamlet and crossroads had become a defensive strongpoint.

To crack this defensive enclave, de Lattre planned a full-scale offensive. Bethouart’s I Corps would attack north through Cernay on 13 December, and de Monsabert’s II Corps, with the U.S. 36th Infantry and the French 2nd Armored Divisions attached, would push south from the Selestat region on the 15th.21 But de Lattre’s mid-December offensive probably never had the strength necessary for success. The November fight through the southern portion of the High Vosges and the Belfort–Mulhouse drive had been more difficult than Haislip’s advance to Strasbourg, and had exhausted French manpower and matériel resources. Furthermore, with their weaker logistical and personnel support systems, the French units always took longer to recuperate than their American counterparts. In December Devers regarded the endemic French shortage of infantry replacements as de Lattre’s most immediate problem, followed by the shortage of line officers with experience handling African colonial troops. Efforts to attach militia elements to regular units continued to have serious drawbacks, and the recruiting and training of new personnel, especially officers and technicians, could not be accomplished overnight.

From the French commander’s point of view, the need to commit strong forces to Operation INDEPENDENCE in western France was his greatest frustration. Ordered again to begin redeploying major troop units for an endeavor entirely unrelated to his current mission, he could only rue

Map 33: The Colmar Pocket, 5 December 1944

his misfortune. On 5 December the French 1st Infantry Division had begun moving west; by the 18th, the main body of the division had closed on western France, and major units of the 1st Armored Division were preparing to follow. Suddenly, SHAEF agreed to yet another postponement.22 Although the infantry division quickly turned around and headed back to the main front, it could obviously play no part in the renewed offensive against Colmar. To Devers and de Lattre, the entire redeployment affair was a waste of effort.

Meanwhile, the tired 36th Division and the roadbound French 2nd Armored Division had continued to plug their way south. Between the Rhine and the Ill rivers, Leclerc’s armor had difficulty penetrating the canal-laced, water-soaked Alsatian plains without more infantry. West of the Ill, Dahlquist’s 36th Division, initially strung out between the Bonhomme Pass in the High Vosges and the Selestat region on the plains, managed only to clean out a portion of the Kaysersberg valley during ten days of heavy fighting, taking one small village after another while fending off almost continuous German counterattacks. Progress was agonizingly slow, but from their observation posts in the mountains, 36th Division troops could see German soldiers walking the streets of Colmar.23 So near, yet so far. In almost constant combat since it first began to push through the Vosges in October, the 36th was exhausted, and Dahlquist finally requested the division’s immediate relief. With Devers’ approval, Patch replaced it with O’Daniel’s rested 3rd Infantry Division on 15 December. Recalling his promise at the Vittel conference in November to clear southern Alsace, Devers hoped that de Lattre’s renewed offensive, with the help of one of the Seventh Army’s strongest units, would finally complete the task.24 Provisionally American engineer units assumed responsibility for the Strasbourg area, and the 36th Division went into a reserve status.

At the same time that Dahlquist was having problems pushing the 36th Division farther, Devers began having serious difficulties with Leclerc. The commander of the French 2nd Armored Division was extremely unhappy with his new orders and had gone to Paris to plead his case with de Gaulle, later arguing that the mission of clearing the Alsatian plains between the Rhine and Ill rivers was more appropriate for an infantry division. He also requested that his armored unit be returned to American control immediately, even though, like the 3rd and 36th Divisions, it was still supported logistically by the Seventh Army. Angry, Devers personally mediated the altercation and privately considered for a short time either disbanding the unit or having Eisenhower ship it off somewhere else. He kept his misgivings to himself, however, feeling that the real problem was the

“bitter hatred” between Leclerc, de Monsabert, and de Lattre over past political differences. Avoiding any open discussion of such matters, Devers informed Leclerc that the mission was necessary and that he had no infantry to spare. The justifiably famous “deuxieme division blindee” would have to make the best of a difficult situation. The problem with Leclerc and the hostility among the various French elements would nag Devers throughout the rest of the war.25

On 15 December, shortly after the arrival of O’Daniel’s 3rd Division, de Lattre renewed his offensive against the pocket, with de Monsabert’s II Corps striking through the Kaysersberg–Selestat area for Colmar city and Bethouart’s I Corps again heading for Cernay. For the first few days, however, the attacks went nowhere; neither the American division nor the French forces were able to make more than a few dents in the now strengthened German defenses. As elsewhere throughout the Allied front, offensive operations continued to be slowed by increasingly cold, wet, and overcast weather. In the flooded southern Alsatian plains, especially in the area between the Ill and Rhine rivers, vehicles of all types found it impossible to operate off the narrow roads, which nullified de Lattre’s numerical superiority in tanks and other armored vehicles. In addition, German control of the Ill–Rhine area exposed the flank of de Monsabert’s offensive to infantry counterattacks from the east, thus blunting the strength of the Franco-American attack toward Colmar.26

On 22 December, after more than one week of fruitless attacks against the Colmar Pocket, Devers finally ordered a halt to the effort. Developments to the north, on the front of General Bradley’s 12th Army Group, now began to have a major effect on Allied military operations throughout western Europe. This concern led Eisenhower to order the 6th Army Group to adopt a defensive posture, and de Lattre’s forces once again broke off the action against Colmar.

Epilogue

News of the German Ardennes attack had spread rapidly through the staffs of the Seventh Army and the 6th Army Group during the evening of 16 December. Initially there was some jubilation. Not believing at first that the assault would pose any severe difficulties for Bradley’s forces, many of Devers’ commanders hoped that the German effort in the north might correspondingly weaken German strength in the south, thereby offering

the Seventh Army a unique opportunity to break through the West Wall defenses into the German interior.27 But such wishful thinking did not last far beyond 18 December as the strength of the German offensive became more evident. A successful German offensive in the north, threatening Antwerp and the entire Allied rear, would be a disaster for all.28

Once again the weight of Allied combat strength began to shift north, although this time for different reasons. Late on the 18th, SHAEF ordered the Third Army’s 80th Infantry and 4th Armored Divisions to redeploy northward for the Ardennes, which forced Haislip to quickly recommit the 12th Armored to the vacated sector. At the same time, Bradley instructed Patton, the Third Army commander, to halt all preparations for his own offensive, then scheduled for the following day, and prepare to send more of his divisions northward. Patton complied but was disgruntled, feeling that the Seventh Army’s drive into the West Wall had loosened up the German defenses in the Third Army’s sector. However, he rapidly recovered both his composure and his enthusiasm after learning of the grave situation in the north and the importance of his new mission.

These changes were only the first signs of a rapid Allied reorientation toward the threatened front. The next day, 19 December, General Eisenhower held a major command conference at Verdun with Devers, Bradley, Patton, and various high-ranking staff officers. There the Allied Supreme Commander’s primary concern was the Ardennes sector, and the urgent need to prepare counterattacks against the northern and southern shoulders of the German penetration. Eisenhower and Bradley put Patton’s Third Army in charge of the southern counterattack, changing its direction of advance from east to north. To support the effort, Devers’ 6th Army Group was to halt all offensive operations and be ready to yield ground if necessary. Furthermore, the 6th Army Group would be responsible for most of the sector vacated by the Third Army. Priority in supplies, equipment, and manpower would go to the forces fighting in the Ardennes.

With this guidance, Devers ordered the offensives against the West Wall and the Colmar Pocket abruptly ended. He also directed the Seventh Army to undertake responsibility for the extended front, spreading out to the west and northwest over twenty-five miles. The increased frontage meant that even without Eisenhower’s instructions, the Seventh Army would have to cease offensive operations, reorganize its forces, and adopt a defensive posture by straightening out its front lines and echeloning its troops in depth.29

Privately General Devers was hardly pleased with the new orders. Recalling Eisenhower’s decision on 24 November

halting the Seventh Army’s Rhine crossing in the Rastatt area, he felt that his command was once again being called on to bail out the northern army groups “just as we are about to crack the Siegfried Line by infiltration ... which would permit us to turn both east and west, threatening Karlsruhe to the east and loosening up the entire Siegfried Line in front of the Third Army to the west.” Although recognizing the necessity of turning the Third Army north against the German Ardennes offensive, Devers believed it a “tragedy” that the Allied high command “has not seen fit to reinforce success on this flank.”30

Once the territorial adjustments were made, the new boundary between the 12th and 6th Army Groups would be located near St. Avold, roughly twenty-seven miles west of the old 26 November line.31 Patch’s Seventh Army would have to absorb the new frontage. To accomplish this, Patch decided to leave his corps boundary intact, but to transfer the 103rd Infantry Division from the center of the VI Corps line to the left of the XV Corps. There, with elements of the 12th Armored Division and the 106th Cavalry Group, it would be responsible for almost all of the new sector. As a precaution, he also pulled the 14th Armored Division back into reserve.

South of Strasbourg, General Devers made no changes in the boundary between the U.S. Seventh and the First French Armies. Although calling off the current effort against Colmar, he directed the First French Army to be prepared to resume its offensive no later than 5 January by which time he expected the emergency in the north to be over.32