Chapter 29: The Colmar Pocket

By the end of the German winter offensives, the battered Western Front traced a ragged line across Belgium, France, and Germany from the North Sea down to the Swiss border. The first Allied order of business was to straighten this line, pulling it taut and reducing its length as much as possible. Shorter lines would mean fewer troops at the front, thus allowing the commanders of the three army groups to move more units back to the rear for rest and recuperation and, ultimately, to concentrate them for a final thrust into the German interior. In northern Alsace, the German attack, which forced the VI Corps out of the Lauterbourg salient and onto the more defensible Moder River line, had partially solved this problem, reducing the VI Corps front by more than half. To the south, however, the Colmar Pocket still created a large fifty-mile gap in the Rhine front of the First French Army, an enemy-held salient that threatened the flanks of any future French advance eastward into Germany.

In early December de Lattre had tried to eliminate the pocket, but his renewed offensive had been undermined by the demands of Operation INDEPENDENCE and by the constant attrition of men and matériel throughout the winter fighting in the Vosges. The French commander continued to have difficulty in overcoming his weak support organization and in turning FFI militia and local draftees into conventional soldiers. The Ardennes emergency finally forced him to call off the effort. For the Germans, maintaining the pocket also presented severe problems. French aggressiveness had kept almost the entire Nineteenth Army busy in defense of the salient, greatly limiting its ability to assist German attacks in the north. The northern offensives, in turn, had siphoned off any reserves that might have been committed to the pocket, making Operation SONNENWENDE, the Nineteenth Army’s contribution to the battle of Alsace, a limited affair that only lengthened the vast 130-mile defensive perimeter around the city of Colmar

Planning the Colmar Offensive

Even as the German attacks in northern Alsace reached their peak, Devers was preparing for a new major offensive against the 850-square-mile Colmar Pocket.1 Allied intelligence

sources, including ULTRA, showed that the Germans did not intend to transfer the rest of their armored forces to the Alsatian front and indicated that de Lattre’s headquarters may have greatly overestimated the size of the German forces now remaining in the pocket. Nevertheless, the 6th Army Group commander was prepared to reinforce the French with considerable American support to ensure that the southern Alsatian plains were swept clean. Devers wanted the Colmar Pocket eliminated once and for all, preferably in January or early February before rainfall and warmer temperatures turned the frozen farming area into a quagmire. The weather was critical for the timing of the attack. The 6th Army Group expected that, after the heavy snowfalls of December and early January, the weather would break in the latter half of January, giving the French some clear skies and clear roads for the offensive, an expectation that agreed with official SHAEF weather predictions. But once slightly warmer weather began to melt the accumulated snowfall, military operations would again become extremely difficult.

On the afternoon of 11 January, Devers and de Lattre conferred at Vittel regarding a renewal of the Colmar offensive. Although both men were eager to begin the effort as soon as possible, they were also concerned about the ground the French had recently been forced to relinquish around Erstein and about the possibility of having to make a last-ditch defense of Strasbourg. For the moment, Devers thought the First French Army was too weak to see the operation through alone and promised to seek additional units from the SHAEF reserve.

Two days later, during a visit by Eisenhower’s chief of staff to the 6th Army Group, Devers put the question to Bedell Smith, asking for two American divisions—an infantry division to reinforce O’Daniel’s 3rd Division at Colmar and an armored division to replace Leclerc’s unit, which he also intended to return south. Smith apparently convinced Eisenhower that the request was justified and cabled a favorable response to Devers the following day, 14 January; he promised the 6th Army Group both the 10th Armored and 28th Infantry Divisions, but warned Devers that the 28th, still badly battered from the Ardennes fighting, was capable of only limited offensive action.

Meanwhile, Devers had already ordered his own staff to put together a general operational plan for de Lattre based on the expected reinforcements and the employment of the U.S. XXI Corps headquarters, which Devers had temporarily placed in charge of Patch’s northern flank.2 Dubbed Operation

CHEERFUL by the Americans, the basic concept was a simultaneous attack on both sides of the pocket toward the major surviving Rhine River bridge near Neuf-Brisach, about seven miles east of Colmar city. The French I Corps was to lead off in the south with a drive from Mulhouse directly to the bridge area, conducting a secondary attack in the mountains north of Thann in order to tie down German forces. After the German reserves had hopefully moved to the south, Maj. Gen. Frank W. Milburn’s XXI Corps was to direct the main effort; while Milburn sent two American infantry divisions and Leclerc’s armored division against the Neuf-Brisach area, assisted perhaps by an airborne assault, the French II Corps would seize Colmar itself. The 6th Army Group planners estimated that Operation CHEERFUL would take about one week and, after studying weather and flood records, recommended that it begin in early February, certainly before the 20th.

Devers accepted the general operational concept, but was more worried about rising temperatures than cloudy skies and insisted that the operation begin much earlier, without either Milburn’s corps or Leclerc’s armor if necessary. De Monsabert’s French corps would have to direct the main effort, which, he agreed, should not be toward Colmar but against Neuf-Brisach. SHAEF’s negative response regarding the availability of airborne forces, an unnecessary complication, did not disturb Devers. He ordered de Lattre to begin the effort by attacking from the south on 20 January and from the north on the 22nd, with the U.S. 28th Infantry Division supporting the northern effort in accordance with its limited capabilities as it arrived on the scene. Despite the rather precarious situation of the VI Corps in the north, Devers was confident that Patch could handle the situation there and wanted to move against the Colmar Pocket while the Germans were still overextended and the weather prognosis was good.

De Lattre accepted the 6th Army Group’s planning concept to use the southern attack to draw off German reserves and concentrate the main effort against the Neuf-Brisach bridge, trapping as many Germans inside the pocket as possible.3 In the north, de Monsabert’s II Corps, already consisting of the U.S. 3rd, the French 1st, and the 3rd Algerian Divisions, would be reinforced with both the French 5th Armored Division and the U.S. 28th Infantry Division, under Maj. Gen. Norman D. Cota. Cota’s weak division was to take over the northwestern perimeter of the pocket, along the Kaysersberg valley just above Colmar city, while the 3rd Algerian Division screened the extreme northern perimeter south of Strasbourg. O’Daniel’s 3rd and the two other French divisions would be concentrated in between, just south of Selestat, for the thrust at Neuf-Brisach and the Rhine. To provide more combat power, Devers also agreed to begin deploying Leclerc’s 2nd Armored Division south to the Strasbourg area as quickly as he could and to move the U.S. 12th Armored Division into the Kaysersberg–Selestat area

by the 22nd as a reserve for the French.4

With these additions, de Monsabert decided that the American 3rd Division, reinforced by one infantry regiment from Task Force Harris (63rd Infantry Division) and supported by one combat command of the French 5th Armored Division, would make the main effort, pushing southeast from the area between Selestat and Kaysersberg. On its left, the French 1st Infantry Division, with some of Leclerc’s armor attached, would push east, covering the northern flank of the American unit. The extreme flanks of the offensive would, in turn, be screened by the rest of de Monsabert’s French units in the north and by Cota’s 28th Division in the south. Once the U.S. 3rd Division had secured bridgeheads over the Colmar Canal, about halfway to the Rhine, the French commander was prepared to commit the rest of the 5th Armored Division to seize the objective area, leaving Leclerc and some attached FFI forces to mop up any Germans left in the Erstein salient north of Neuf-Brisach. At the beginning, however, the main attacking forces would ignore both the Erstein salient and Colmar itself and would advance southeast, between these two more obvious objectives. The projected route of advance would take them across four major water barriers: the Fecht and Ill rivers, the Riedwiller Brook, and the Colmar Canal. Each was critical, and de Monsabert hoped that, with speed and surprise, all four could be breached quickly before the Germans could react.

On the southern edge of the pocket, General Bethouart’s I Corps prepared to support the main effort by beginning its attack two days earlier than de Monsabert and striking north with two divisions, the 4th Moroccan Mountain and the 2nd Moroccan Infantry, using the 9th Colonial Infantry Division at the base of the pocket as a pivot. The French 1st Armored Division would provide some tank support to the attacking formations, but the bulk of du Vigier’s armored command would initially remain in reserve. Departing from the 6th Army Group’s planning concept, Bethouart wanted his Moroccan divisions to make the main effort on the left (west) between Thann and Cernay over the Thur River toward Ensisheim, while the 9th Colonial pushed into the suburbs and woods north of Mulhouse. Once these forces had cleared a roughly triangular shape of territory between Cernay, Ensisheim, and Mulhouse and had secured bridges over the Ill River at Ensisheim, the 1st Armored Division would pass through the French lines and drive for Neuf-Brisach.

North of Thann, in the High Vosges, de Lattre had replaced the 3rd Algerian Division with the new French 10th Infantry Division, which had been assembled primarily from FFI resources, and expected the unit only to guard the western boundaries of the pocket on the slopes of the Vosges.

As everyone now realized, the Colmar terrain presented many challenges to the Allied forces, both north and south. Because of innumerable

streams, brooks, small rivers, and canals on the projected routes of advance of both corps, considerable bridging equipment was required. To make the maximum amount available, the French replaced many of the existing Bailey bridges in their areas with timber structures, and Devers managed to obtain a bridge company from the Third Army to provide direct support for the U.S. 3rd Division. But bridging remained scarce and had to be carefully rationed; ultimately much more had to be made available to the French from Seventh Army and theater reserves during the course of the operation. Other shortages existed throughout the First French Army: initially only ten days’ worth of ammunition and one day’s reserve of gasoline were available at forward depots; large numbers of vehicles were deadlined and awaiting repair due to a lack of spare parts; and the manpower losses suffered during the November offensive had not yet been replenished. O’Daniel’s 3rd Division was in better shape, having been relieved by Cota’s 28th on 19 January, but had been fighting a fierce seesaw battle for control of the Kaysersberg valley since its arrival on the northern approaches to Colmar.5 Before the offensive and during the days that followed, the 6th Army Group staff endeavored to satisfy de Lattre’s most pressing supply and equipment shortages, aided by the quiet that had finally descended on Patch’s Seventh Army front to the north.

The German Defense

In mid-January 1945 the mission of General Rasp’s Nineteenth Army was to tie down the largest possible number of Allied forces west of the Rhine, giving OKW more time to redeploy German units to the Eastern Front and reorganize the defenses of those that remained. In addition, on 22 January Army Group Oberrhein ordered Rasp to be prepared to renew his attacks in the northern corner of the pocket in support of what was to be the final German effort against Brooks’ VI Corps along the Moder River. At the time, Rasp and his two corps commanders would have preferred to conduct a gradual, fighting withdrawal to the east bank of the Rhine and eventually to deploy the bulk of the Nineteenth Army north of the Black Forest, where the major Allied offensives were expected to occur.6 But the abrupt termination of the offensive in northern Alsace on the 26th at least freed them from any further supporting requirements.

Inside the Colmar Pocket the Nineteenth Army controlled two corps headquarters, eight infantry divisions, and one armored brigade. General Thumm’s LXIV Corps held the northern half of the pocket with the 189th and 198th Infantry Divisions and the 16th and

708th Volksgrenadier Divisions.7 Operation SONNENWENDE had left the 198th in the Erstein salient and the 708th Volksgrenadiers holding a north-south line along the Ill River from Selestat south to Colmar, supported by the 280th Assault Gun Battalion. At Colmar, the 189th Infantry Division took over the defensive perimeter, which stretched westward into the Vosges where the 16th Volksgrenadiers outposted the mountainous western section of the pocket. In the south Lt. Gen. Erich Abraham, who had replaced Schack as commander of the LXIII Corps on 13 December, had the 338th, 159th, and 716th Infantry Divisions, with the weak 338th in the mountains northwest of Thann, the 159th centered around Cernay, and the 716th opposite Mulhouse. In army reserve were the 106th Panzer Brigade and the 269th Infantry Division; however, the latter unit was currently in the process of deploying to the Eastern Front, and its replacement, the 2nd Mountain Division, was still nowhere in sight.

All of the line divisions were under-strength, under-trained, and under-equipped, having only about 30 to 40 percent of their antitank weapons and little ammunition for their more numerous artillery pieces. Armor was even scarcer, totaling perhaps sixty-five operational tanks and assault guns, and was concentrated generally in the armored brigade and two mobile antitank units, the 280th Assault Gun Battalion and the 654th Tank Destroyer (Panzerjaeger) Battalion. Experienced infantry was also in short supply, with most of the line battalions fleshed out with hastily trained fillers and recruits. By now, such conditions must have seemed almost normal to the Nineteenth Army staff, which could still count on many advantages that made it difficult for the Allies to summarily eject its forces from the area. Rasp had some 22,500 effectives (versus an Allied estimate of 15,000); short interior lines of communication; good wire communications down to at least the battalion level; ample rations and stocks of mines and small-arms ammunition; and a secure rear area. The weather and terrain heavily favored the defense, as did the Alsatian network of small towns, each of which could be turned into a tiny fortress; together they provided a ready-made strongpoint defensive system that enabled Rasp to make the best use of his poorly trained but highly motivated troops. The failure of the French and Americans to make any vital penetrations in this system during the past month attested to its effectiveness, but Rasp’s fixed defensive arrangements also made it difficult to concentrate his forces for local counterattacks of any significance.

Key to Rasp’s defensive effort was his ability to secure two major bridges over the Rhine, which, because of their sturdy construction, had proved impossible to destroy by air attacks. The first was a single-track, reinforced railway bridge at Brisach (two miles east of Neuf-Brisach), which the German soldiers had already awarded an honorary Iron Cross for surviving massive Allied bombing assaults; the

second was the Neuenburg bridge just opposite the French town of Chalampe, which de Lattre had considered seizing back in November. In addition the Nineteenth Army maintained numerous permanent ferry sites along the Rhine capable of handling 8-, 16-, 40-, and even a few 70-ton loads. Near Brisach alone were four 10-ton, six 16-ton, and one 70-ton ferry sites, two cable ferries, and one fuel pipeline; furthermore, all road networks on the German side of the Rhine were in good condition. But the two bridge sites were critical for the survival of the Nineteenth Army, and the German commanders predicted that the Allies would eventually try to seize them. No one at either Nineteenth Army headquarters or at Army Group Oberrhein, however, expected that the attempt would be made before the battles in the north had ended and the Allied forces had taken some time to recover.

The Initial Attacks

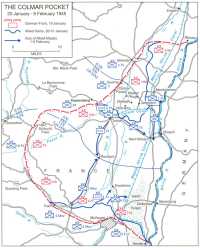

As scheduled, the French I Corps attack jumped off in the south on 20 January with Bethouart’s two Moroccan divisions undertaking the main effort from Cernay to Ensisheim, the 9th Colonial Division making a secondary foray north of Mulhouse, and other units conducting a small diversionary maneuver north of Thann (Map 35). Unhappily for the southern French forces, Allied weather predictions proved incorrect, and the offensive began in the middle of a driving snowstorm. Bethouart’s forces easily achieved tactical surprise, driving forward several miles during the first day of the attack and striking hard at the boundary between the German 159th and 716th Divisions. But the adverse weather and terrain together with the elastic German defenses broke the tempo of the advance during the night. Throughout the 21st, the Germans launched a series of small armor-supported counterattacks and managed to hold on to Cernay and limit French gains above Mulhouse. Although failing to achieve the deep penetration that the I Corps commander had hoped for, the attacks at least succeeded in drawing the Nineteenth Army’s scant armor reserves southward. Army Group Oberrhein approved the immediate commitment of the 654th Tank Destroyer Battalion and also ordered the 106th Panzer Brigade and later arriving elements of the 2nd Mountain Division southward to the threatened area. Initially, however, neither Himmler nor Rasp attached any great significance to the actions, which, they believed, represented no more than a limited diversionary effort to reduce pressure on Strasbourg in the north.

Despite the attention that Rasp would direct to his northern sector several days later, the I Corps attack remained stalled in the south for the rest of the month. Bethouart shifted his main effort slightly east, where the 9th Colonial had done a bit better, but the results were the same. German resistance was stubborn and their defenses were organized in depth, with the French attacks channeled by roads, forests, streams, and small towns through a series of heavily defended choke points. Furthermore, the slow pace of the French advance allowed bypassed

Map 35: The Colmar Pocket, 20 January–5 February 1945

defenders to pull back in an orderly manner, aided by the heavy snowfall and overcast skies that limited Allied air support and vehicle mobility. At the end of the month, after eleven days of fighting, the 159th Division maintained its hold on Cernay, and the I Corps forces were still a disappointing five or six miles short of Ensisheim, their intermediate objective. At the time, Bethouart reported that his infantry was exhausted, his stocks of artillery ammunition almost depleted, and two of his armored division’s three tank battalions reduced to between sixteen and eighteen operable armored vehicles apiece. CC1 alone had lost thirty-six tanks during the offensive to German mines.

In the north de Monsabert’s II Corps attack began on 22 January, also on schedule, and initially achieved more success. General Thumm, the LXIV Corps commander, had noted the Allied buildup between Colmar and Selestat as well as the reinforcement of the U.S. 3rd Division by what he assumed was the entire American 63rd Infantry Division (actually it was one TF Harris regiment). Since he was under orders to hold the entire Erstein salient, however, the German commander had no opportunity to consolidate his defending forces or to strengthen those facing the American units. Instead, he instructed the 708th Volksgrenadier Division to maintain only a thin defensive screen west of the Ill River, keeping enough forces to the rear for strong, local counterattacks in order to prevent its front from being pierced by a single concentrated attack. He also attached the 280th Assault Battalion, with a dozen or so heavy Mark V jagdpanthers and some tanks and assault guns, to the division to give it reserve muscle, but he lacked the infantry strength in the area to give the defense more substance and depth.

General O’Daniel, still commanding the experienced 3rd Division, fully understood the difficulties that would face his troops. The arrival of the U.S. 28th Division in the Kaysersberg area had at least given him the opportunity to rest his infantry for a few days while he concentrated them for the attack. With the French 1st Infantry Division supporting his advance on the left, and with both units substantially reinforced with experienced armored units, O’Daniel was confident that a rapid breakthrough could be achieved. Specifically he planned to begin the 3rd Division’s attack with a successive series of assaults by his four infantry regiments (the 7th, 15th, and 30th and the attached 254th). Each was to push directly east for a few miles and then drive south for another five to ten miles; the next attacking regiment would pass through the rear lines of the first and then attack east for a few miles before turning south as the first had done. In this way O’Daniel hoped to sidestep the entire division southeast to the Colmar Canal and beyond, opening a path for a final drive by the French 5th Armored Division on Neuf-Brisach. At that point the 28th Division could extend its front westward, allowing most of the 3rd Division to support the final push. The maneuver might also deceive the Germans into believing that the Americans were trying either to outflank Colmar city or threaten the Erstein salient, when their real objective was the Neuf-Brisach bridge and ferry sites.

The Bridge at Maison Rouge

Successful river crossings were vital to the Allied attack. On the first two days of de Monsabert’s offensive, 22 and 23 January, all went according to the 3rd Division plan, Operation GRANDSLAM.8 The division’s 7th Infantry regiment, commanded by Col. John A. Heintges, crossed the Fecht River at Guemar, which was already in Allied hands, around 2100 on the 21st and proceeded south. There it would spend the next four days clearing the forests and towns between the Fecht and Ill rivers for about ten miles, rolling up Thumm’s9 thin screening forces in the process. Following in the footsteps of the 7th, the 30th Infantry, under Col. Lionel C. McGarr, was also to cross the Fecht at Guemar during the night of 22–23 January. McGarr planned to have his unit march east through the Colmar forest, previously cleared by the 7th regiment, secure crossing points over the Ill, and then push south, paralleling the advance of the 7th, clearing the towns of Riedwihr and Holtzwihr, and finally seizing crossing points over the Colmar Canal. O’Daniel had attached one tank and one tank destroyer company to the regiment to screen its open, eastern flank until the next attacking regiment, the 15th Infantry, could swing into position behind and to the east of the others.

McGarr’s regiment set out from Guemar around midnight, trudging through the deep snow. In addition to his semiautomatic M1, each rifleman carried four bandoleers of ammunition, three fragmentation and one white phosphorous grenade, one day’s worth of K-rations, one blanket and one shelter half, and inevitably cigarettes, toilet articles, and other miscellaneous personal items, including letters and pictures from home. The temperature was well below freezing, but the dark Colmar forest cut the wind somewhat, which made the foot march more bearable. The unit’s initial objective was the Maison Rouge bridge, a medium-sized wooden span over the Ill River opposite the southeastern corner of the forest. Once this crossing site had been secured, along with a road junction a few miles beyond the Ill, the engineers were to bring up bridging equipment early on the 23rd, enabling the entire force to move across the Ill for its advance south.

Shortly after entering the Colmar forest, McGarr split the regiment into two attacking forces; he sent the 3rd Battalion southeast directly for the bridge and the 1st Battalion east with instructions to cross the Ill about 1,500 yards above the bridge site and move down to the crossing site from the north. Subsequently, the 1st Battalion managed to cross the Ill in rubber boats during the night unopposed and sweep down the east bank of the river, surprising a small detachment of Germans at the bridge. By 0530 the next morning, McGarr’s unit thus found itself in possession of a fairly large but worn timber bridge

over the Ill as well as the crossroads located about a mile or so east of the bridge and the small farm complex of Maison Rouge in between.10

During the early morning hours of the 24th, McGarr consolidated the bridgehead, bringing the rest of his forces up to the area as quickly as possible, organizing defensive positions for the expected German counterattack, and pushing patrols out to the east, southeast, and south. Outside of several strands of trees along the Ill River and a small parallel stream, the troops found little natural cover in the area, with broad, snow-covered Alsatian fields stretching off to the east of the river for several miles. About two miles to the southeast stood the Riedwihr woods and, beyond the small forest, the towns of Riedwihr and Holtzwihr, both intermediate regimental objectives. With apparently no German response to the crossing immediately forthcoming, McGarr decided to continue the advance as quickly as possible. He directed the 1st Battalion to move through the Riedwihr woods toward Riedwihr; the 3rd to pass behind the 1st and advance on Holtzwihr, a mile or so farther south; and the 2nd to follow the 1st into the Riedwihr woods as a reserve. O’Daniel had already radioed McGarr at 0755 that morning, impressing on him the need for speed and the necessity of pushing across the Colmar Canal by the following night.

The bridge at Maison Rouge presented a problem for the attacking force. The Americans had not expected to find the structure intact and had planned to begin constructing an armored treadway bridge to the north later in the day. The capture of the span, however, changed these plans, and McGarr judged that his accompanying vehicles could use the bridge after engineers reinforced it. Division engineer officers confirmed McGarr’s estimate around 1330, but could not guarantee completion of the work until early the next morning. The river at the crossing site was about 90 feet wide; the bridge was about 100 feet long, consisting of two 30-foot approach ramps and two 20-foot center spans. One of the attached thirty-ton Sherman tanks had been run up and down the west ramp, causing the structure to shake and sway violently, which ended any ideas the tankers might have had of charging across.

Throughout the day McGarr became increasingly nervous about his lack of armor or antitank support east of the river. As early as 1142, leading elements of the 1st Battalion had reported hearing enemy armor around Riedwihr and later, from the eastern edge of the Riedwihr woods, had seen a few German armored vehicles running through the town. Concerned, McGarr pressed the engineers for immediate assistance with the bridge; they decided that, as an expedient, strengthening the center spans somewhat and reinforcing the surface with treadway bridging would enable it to hold the heavier vehicles. However, when the treadway sections finally arrived around 1500, the engineers found that too little had been brought forward to cover the entire

bridge and warned that the arrival of additional sections might be delayed several hours because of the heavy traffic on the 3rd Division’s supply routes. Informed of the difficulty, O’Daniel again called McGarr at 1555 and instructed him to continue his advance south without the armor. Speed was essential if the momentum of the attack was to continue.

At 1630 McGarr ordered his units to begin their assaults on Riedwihr and Holtzwihr. Almost immediately both attacking battalions ran into trouble. The 3rd Battalion moved into Holtzwihr sometime between 1630 and 1700, but was counterattacked by strong infantry-tank teams and reported having difficulty holding on. The 1st Battalion met heavy enemy fire as soon as it approached Riedwihr and was barely able to reach the outskirts of town. Both units requested immediate assistance to deal with the enemy armor.

Impressed by the need to bring some tanks across the Ill at once, the engineers took a calculated risk. Without waiting for additional bridging supplies, they decided to overlay both of the unsteady bridge ramps with treadway sections and hoped that the shorter center spans could take about ten medium tanks. About 1700, after running three of the regiment’s towed 57-mm. antitank guns and movers and a large ten-ton truck across the bridge, Lt. John F. Harmon drove the lead tank up the reinforced ramp and onto the center span. Almost immediately, as soon as the thirty-ton Sherman had cleared the eight-inch high treadway and hit the wooden surface, the bridge gave way, with tank and lieutenant falling “like an elevator” into the icy Ill River. Harmon escaped with a few bruises, but obviously no more American vehicles would be attempting to cross the river for many hours, and the 30th Infantry would have to fight on alone. The crews of the remaining tanks and tank destroyers could do little more than place their machines in supporting positions along the opposite bank of the river.

What occurred during the next several hours is unclear. Apparently all three of McGarr’s battalions suddenly found themselves in the midst of a general German counterattack from elements of the 708th Volksgrenadier Division and the 280th Assault Gun Battalion. The 30th Infantry’s antitank forces, bazookas and 57-mm. cannons, had no chance against the heavily armored jagdpanzers and jagdpanthers (assault guns on Mark IV and V tank chassis). Around 1800 one of the American tank officers, after crossing the damaged bridge on foot to reconnoiter the opposite side, reported streams of panicked soldiers from the 30th pouring back from the Riedwihr woods in complete disorder, abandoning weapons and attempting to climb over the damaged bridge. In the background he noted white tracers from German automatic weapons mingled with the red tracers of American arms—someone was still fighting—but most of the regiment appeared to be taking refuge along the stream and riverbanks or braving the cold waters of the Ill to reach the opposite shore. There, frustrated tank and tank destroyer crews watched the debacle, and shortly thereafter, as the sunlight began to fade, they spotted the squat German assault guns

moving up two by two, each section covering the advance of the other. Antitank and artillery fire kept the counterattacking force at bay for a while, but sometime after dark the bridgehead appeared to be in German hands, though no one could tell for sure.11

At 2030 that night, as the 30th Infantry collected itself on the west side of the Ill, O’Daniel ordered Lt. Col. Hallett D. Edson, commanding the 15th Infantry, to secure the bridgehead, see to the repair of the structure, and resume the 3rd Division’s attack as soon as possible. Loss of momentum had to be avoided at all costs. Edson alerted his 3rd Battalion and immediately sent two of its rifle companies, I and K, directly through Guemar and the Colmar woods and over the Ill, following the trail that the 30th Infantry’s 1st Battalion had taken twenty-four hours earlier. Descending on the Maison Rouge area from the north, as their predecessors had done, the two companies scattered a small German holding force around 0500 on 24 January, rounded up a number of 30th regiment infantrymen who had somehow survived the night on the east bank, and proceeded to secure the area as best they could. Instructed to defend both the bridge area and the crossroads, the battalion commander gave Company K the responsibility for the crossing site and sent Company I out to occupy the crossroads. As dawn came, the Company I commander, finding the crossroads completely exposed and without any cover, requested permission to pull the unit back to the tree line, but was instructed to hold in place: division engineers were just completing a new treadway bridge to the north, and armored support could be expected shortly.

For the next several hours the men of Company I frantically chipped away at the frozen ground, digging up at best a few inches of dirt, ice, and snow and wondering when the tanks would arrive. They finally came about three hours later, but from the wrong side. At 0800 on the 24th, the Germans launched their second counterattack against the bridgehead with thirteen heavy assault guns and a company or more of infantry. As the enemy machines began pushing through the mile or so of fields between Company I and the Riedwihr woods, the American soldiers scrambled into their makeshift foxholes and watched and waited, lying flat on the frozen ground. Friendly artillery soon caused the attacking infantry, barely visible at first, to disperse and lag behind; but the assault guns, accompanied by a few tanks and lighter armored vehicles, continued toward them at a steady pace. The company commander and his forward observer ticked off the German progress for many to hear—800 yards away, then 600, and then 500. A few panicked and fled, and others asked their officers, “Can we go?” The rest stayed, although, as one sergeant later recalled, “we all practically had one foot out of the foxhole,” and when the company commander finally made the decision to pull back, “we didn’t have to give the order very loud.”

That morning, shortly after 0800, the company was overrun. Some soldiers were crushed under the German tank treads or machine-gunned where they lay; others managed to fall back into the Company K area closer to the river; still others were shot while trying to surrender. Most of the 3rd Platoon was thought to have been captured.

The success of the German counterattack again proved brief. As it swept through Company I and moved on against Company K, direct American tank and tank destroyer fire from across the river forced the German assault guns back, and the German infantry was unable to budge the defenders by themselves. In the north, however, two American tanks and a tank destroyer, which had finally managed to cross the new treadway bridge, charged south and rolled into the battle area “bumper-to-bumper,” where they were promptly picked off by the German tank gunners. The battle for the bridgehead thus continued throughout the rest of the morning and into the early afternoon, with neither side able to completely secure the area. At last, around 1430 that afternoon, the 1st Battalion, 15th Infantry, counterattacked from the north with more armor, finally relieving those at the bridge site: “here they come ... if that ain’t a beautiful sight ... strictly a Hollywood finish ... just like the movies.” The rest of the regiment soon followed.

Edson’s regiment continued south, advancing on Riedwihr, Holtzwihr, and the Colmar Canal, while the German forces pulled back east, still unsure of the 3rd Division’s specific axis of advance. West of the Ill the 30th Infantry, rather dazed but also embarrassed and angry, regrouped and reorganized. The average strength of its rifle companies had fallen to seventy-two or seventy-three men, and the survivors later added a new verse to the regimental ditty:

But we have our weaker moments

Even when success is huge

‘Cause the outfit took a licken

at the bridge at Maison Rouge.

But three days later, on 27 January, after only a brief respite, the 30th Infantry went back into action as if nothing had happened. O’Daniel’s high opinion of the unit and his equally high expectations of its performance remained unchanged.

The fighting at Maison Rouge typified the back-and-forth flow of the Allied advance in the north and south. In both areas the attackers found the Germans deployed in depth, counterattacking whenever possible but lacking the strength or mobility to do more than wear down the advancing forces. As the 15th Infantry entered Riedwihr on the night of 25–26 January, O’Daniel was slipping the 254th Infantry regiment behind the 15th and directing it at the next 3rd Division objective, Jebsheim. On the 26th and 27th, the Germans made a spirited defense of the town, a key north-south communications junction, while launching repeated armor-supported counterattacks in the Riedwihr area, but to no avail. On 26 January 1945, in the much-contested Riedwihr woods, 2nd Lt. Audie Murphy, one of the most decorated U.S. soldiers of the war and later a popular film star, earned the Congressional Medal of Honor

for turning back several German attacks from the turret of a burning tank destroyer.12 With equal determination, the 254th secured Jebsheim by the 28th and continued east.

O’Daniel recommitted the 30th Infantry south of Riedwihr on the 27th. McGarr’s unit again took Holtzwihr and drove south, reaching its original objective, the Colmar Canal, on the 29th. Meanwhile, de Monsabert extended the front of the U.S. 28th Division eastward, freeing Heintges’ 7th regiment for employment elsewhere; furthermore, to the north the French 1st Infantry Division, which had also encountered difficulties maintaining a bridgehead over the Ill, began making substantial progress, securing the 3rd Division’s northern flank. With the 30th Infantry on the canal and the 28th Division moving east, O’Daniel finally sidestepped both the 7th and 15th regiments between Riedwihr and Jebsheim, putting them over the Colmar Canal on the night of 29–30 January, abreast of the 30th Infantry. The following day all three regiments drove south several miles, securing the canal crossing sites for the French 5th Armored Division. By the 30th therefore, O’Daniel had pushed a fairly substantial wedge into the German lines, with the 30th Infantry outflanking Colmar city on the east; the 254th advancing out of Jebsheim toward the Rhone–Rhine Canal and the Rhine River; and the 7th and 15th regiments, supported by French armor, facing south and southeast toward Neuf-Brisach. Here the advance halted. The 3rd Division was exhausted at least temporarily and, with some of its rifle companies now down to about thirty able-bodied men, its offensive capabilities were greatly reduced.

Reorganization

From the beginning of the effort Devers had been concerned about de Lattre’s strength as well as the vagaries of weather and terrain. Despite the advances by American troops, the progress of the French forces north and south had not been encouraging. As early as the 27th the slow forward movement of both attacks and the heavy expenditure of ammunition had convinced the 6th Army Group commander that more American assistance was needed. Assessing the situation on that day, Devers was dissatisfied, feeling that the French units lacked “the punch or the willingness to go all out,” but he also noted that, contrary to expectations, “the weather, with three feet of snow, has been abominable,” and had slowed progress everywhere on the Allied front. He was, however, proud of the 3rd Division’s accomplishments, describing the earlier Maison Rouge episode as “one of those unpredictable things in war.” He noted that O’Daniel, “sound, sober ... but just as determined as ever to carry on,” took full responsibility for the tactical mistakes made there.13

At the time, SHAEF had already promised Devers two more American infantry divisions, the 35th for Patch and the 75th for de Lattre; furthermore, Devers was now ready to

commit Milburn’s XXI Corps and Allen’s 12th Armored Division to the Colmar struggle. Basically Devers wanted the XXI Corps to control the three American infantry divisions, the 3rd, 28th, and 75th, for a final drive on Neuf-Brisach, with the 12th Armored in reserve. De Lattre agreed and also assigned the French 5th Armored Division entirely to Milburn, leaving Leclerc’s 2nd Armored Division with de Monsabert. General Milburn, who had been alerted to the mission well before the start of the offensive, intended to continue using O’Daniel’s 3rd to spearhead the attack, but now reinforced it with most of the 5th Armored Division in order to beef up the tired American regiments. Cota’s 28th Division, assisted by Maj. Gen. Ray E. Porter’s 75th, another worn-out veteran of the Ardennes, would continue to fill in the southern flanks of the advance, while de Monsabert’s II Corps forces secured the northern flank. The 12th Armored Division, still recovering from its ordeal at Herrlisheim, would temporarily remain in reserve north of Colmar. With these forces plus additional allocations of artillery ammunition from the 6th Army Group, de Lattre planned to renew the dual offensive on 1 February.

Significant changes had also occurred on the opposing side. On 29 January General Paul Hauser, a combat-experienced SS officer, assumed command of Army Group G, including all forces formerly assigned to Army Group Oberrhein. At the same time Hitler dissolved Army Group Oberrhein, assigned Himmler a command on the Eastern Front, and appointed Blaskowitz commander of Army Group H in Holland. The German armies on the Western Front were thus once again united under von Rundstedt’s OB West.

In preparation for the command change, Army Group G had already reviewed the situation of the Nineteenth Army in the Colmar Pocket and, as early as the 25th, had concluded that the enclave was no longer important to the German defensive effort in the west. The current Allied attacks were threatening to isolate and destroy the German divisions in the Erstein salient, and their evacuation seemed the first order of business. In sum, the staff recommended that either the entire pocket should be abandoned or, at the very least, the northern extension at Erstein should be evacuated and the forces used to strengthen the northern shoulder. On the night of 28–29 January Hitler finally agreed to the partial withdrawal in the north, but insisted that the pocket be defended as long as possible. Von Rundstedt was of the same opinion, mistakenly believing that a renewed Allied offensive against the Saar basin was imminent and that a continued diversion of Allied resources against Colmar would significantly delay the start of this endeavor.

German intelligence in the Colmar area was faulty. The German commanders generally remained ignorant of American reinforcements until the troops actually appeared on the battlefield, and they continued to believe that the primary Franco-American objective in the north was a drive directly east from Selestat to Marckolsheim, which would reach out to the Rhine River and both isolate the forces in the Erstein salient and secure a

springboard for a later offensive against the Neuf-Brisach bridge. At no time did they appear to discern de Lattre’s intention of attempting a double envelopment from north and south; instead they judged that de Lattre’s forces in the west and south would simply try to exert pressure on all sides of the pocket until something gave way.

Inside the pocket the defensive situation of the Nineteenth Army was also becoming muddled. To assist in the defense of both Cernay and Ensisheim in the south and Marckolsheim in the north, Rasp had authorized his corps commanders, Thumm and Abraham, to begin withdrawing several battle groups from the Vosges. As a result, units from the 16th Volksgrenadier and the 189th and 338th Infantry Divisions had become hopelessly mixed with those of the other divisions in a helter-skelter fashion; these mixtures were then further infused with a miscellany of service and support forces turned into infantry as well as with units of the 2nd Mountain Division, which had begun arriving in the pocket sometime after the 20th and were being fed piecemeal into the battle. For the American and French commanders, the German tactical situation was often equally confusing, with many of the 3rd Division’s regiments identifying elements of four or five different German divisions on their front. The net result was the fragmentation of the entire German defensive effort. On the 29th, for example, Thumm had tried to counter the surprise American assault south over the Colmar Canal with a few battalions of the 189th Division, one from the 198th (currently deploying from the Erstein salient), and another from the 2nd Mountain Division. Not surprisingly, the counterattacks were uncoordinated and ineffective. Elsewhere similar situations were common, and the German commanders remained unable to discern the main axis of de Lattre’s offensive or even to predict the next objective of O’Daniel’s side-stepping division.

Only on 30 January, with the entire 3rd Division pouring over the Colmar Canal, did Rasp, Hauser, and von Rundstedt begin to perceive that the Allied drive was headed directly for the bridge at Neuf-Brisach and not Marckolsheim; at the same time they concluded—again mistakenly—that the objective of the French drive in the south was the Neuenburg bridge at Chalampe. Yet almost all of their “reserves”—forces from the Erstein salient and those from the Vosges—had been committed elsewhere, and they had no means of stopping a renewed Allied drive or reinforcing those units that appeared to lie in its path. As a result, on the night of the 30th, Army Group G sent new orders to Rasp, specifying that his main mission was to “assure the survival” of the German pocket across the Rhine for as long as possible and authorizing him to withdraw most of his forces from the Vosges front, leaving only reconnaissance detachments to hold the mountain passes. The Nineteenth Army was henceforth to concentrate all of its combat power on the northern and southern shoulders of the bridgehead. Rasp, in turn, ordered the immediate evacuation of all forces in the Vosges that had no organic transportation as well as the transfer of all heavy equipment and support installations to and

Railway bridge at Neuf-Brisach finally destroyed

across the Rhine, while sending what reinforcement he could from the west to protect his two major bridge sites. How much time he had to shuffle his units around was a question mark, especially since OKW had so far refused to authorize the withdrawal of any of his forces across the Rhine.

The February Offensive

The second Franco-American surge against the Colmar Pocket proved successful. Although the Germans still tried to jam the Allied advance at key road and water junctions, especially those on their own lines of communication, the Allied penetration of their initial strongpoint defense system was too deep; their secondary and tertiary positions had too many gaps that were easily exploited; and they continued to be unable to move adequate reinforcements to threatened areas. The U.S. 75th Infantry Division had begun moving into the First French Army area on 27 January and by the evening of the 31st started to relieve O’Daniel’s 3rd Division regiments south of the Colmar Canal for the final push. Again O’Daniel attacked east and then south, first slipping the 30th Infantry behind the others and moving it east to the Rhone–Rhine Canal for a drive south with units of the French 5th Armored Division. Next, with the arrival of Porter’s 75th Division on the battlefield, he transferred both the 7th and 15th Infantry to the far side of the Rhone–Rhine

Canal, turning them south as well. The 254th Infantry brought up the rear. By 3 February elements of all three 3rd Division regiments were approaching Neuf-Brisach, and the Germans began a last-ditch defense of the bridgehead with all available manpower.14 On the 5th, with the old fortress town nearly surrounded, the Germans started to evacuate the area, and by noon of the following day, 6 February, the entire sector was under Allied control.

Inside the pocket the German defenses around the city of Colmar had already collapsed. While the 3rd Division attacked toward Neuf-Brisach, first the attached 254th regiment and then the regiments of the 28th Division steadily pushed against the northern approaches to Colmar in the Kaysersberg valley. By 2 February Cota’s units had cleared the city’s suburbs against diminishing resistance, allowing units of the French 5th Armored Division to drive into the heart of Colmar nearly unopposed. Immediately de Lattre agreed to commit the U.S. 12th Armored Division through the 28th Division for a drive south; two days later American armored task forces, moving south along two parallel axes, met French I Corps elements at Rouffach during the early morning hours of 5 February. By that date the bulk of Bethouart’s southern forces had finally bypassed German emplacements around Ensisheim and, finding enemy defenses crumbling elsewhere, raced to Rouffach from the south. The drives split the Colmar Pocket wide open.

Between 5 and 9 February, as the supporting American divisions redeployed northward, French forces finished cleaning out the pocket. In the north de Monsabert’s forces swept the west side of the Rhine from Erstein to Marckolsheim, while in the west units of the new French 10th Infantry Division and the 4th Moroccan Mountain Division policed up the interior of the pocket. To the south, Bethouart directed his main effort against the last German bridgehead at Chalampe, using the 1st Armored and the 2nd Moroccan and 9th Colonial Divisions. Here German resistance remained fierce for a few days, but the French managed to penetrate across the Ill River on 5 February, secure Ensisheim on the 6th, and reach the Rhone–Rhine Canal by the 7th. There they were joined by Leclerc’s armor on the 8th; the next morning, elements of the 9th Colonial reached the Rhine at Chalampe, forcing the Germans to destroy the remaining bridge at 0800. This final act marked the end of the Colmar Pocket and the German presence in upper Alsace as well.

Tactics and Techniques

For the troops on the ground, the fighting rivaled the harshness of the earlier advance through the Vosges. Here the French were at a disadvantage: the ranks of their specialized colonial troops were stretched precariously thin, and many Caucasian infantry replacements had little more than a few months of military training at best. They were good enough for

Neuf-Brisach (old fortress town)

static defensive operations, but less able to perform the tactically more complicated mission of attacking. Only the stubbornness of their own officers and the assistance of the Americans finally gave them the edge. In this area, the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division showed everyone why it was considered one of the finest units in the American Army. Shrugging off the Maison Rouge bridge incident, the division’s stellar performance was clearly vital to the First French Army’s overall success. Although it was an “old” division that theoretically had been “fought out”—exhausted—by the end of its Italian campaigning, its small units, especially the infantry-tank teams, seemed to rise to the occasion as they approached each of the fortified Alsatian towns on their route of advance.15

By this time, experienced units like the 3rd Division had almost unconsciously perfected their combined arms teamwork to a fine art, enabling them to overcome the physical fatigue that most of the soldiers, officers and enlisted men alike, must have felt. In the Colmar campaign, the American armor-supported infantry units sent out small patrols to scout each town

French Infantry advances into Colmar

briefly, while the main attacking forces prepared to assault the area. If the town was defended, the infantry moved forward covered by the direct fire of supporting tanks and tank destroyers; stronger resistance merited additional support from mortars and artillery and perhaps even tactical air strikes if available. Once foot soldiers reached the outskirts of town, a few tanks might move up to support deeper penetrations, but the rest stayed clear of the built-up areas, covering the flanks of the attacking force and maybe shifting their position to one side of the town or the other in order to prevent reinforcements from arriving. Inside, infantrymen searched each house deliberately from top to bottom, tossing grenades in the cellars where the defenders usually congregated and greeting survivors with the traditional “Hindy Ho” (Hande Hoch, or literally “hands up”). Meanwhile, American artillery shells destined for “Krautland” streamed overhead, striking the opposite side of the town or interdicting the roads beyond that might carry German reinforcements, or perhaps only “softening up” the unit’s next objective down the line.

The American troops were brave, but not foolhardy. As elsewhere, the 3rd Division combat soldiers had an abiding fear of the German flat-trajectory, high-velocity cannons—the so-called 88s (although most were 75-mm. pieces)—as well as German mortar fire (for its accuracy) and the

buzz-saw-like German machine guns (with a higher rate of fire than the American equivalents).16 In the eyes of the average soldier, however, the German tanks presented the most serious problem. Because of the better armor protection of the heavier German vehicles, tanks and assault guns alike (foot troops tended to identify all as Tigers), the bazookas and 57-mm. antitank guns organic to the infantry battalions and regiments were relatively ineffective, as were the 37-mm. cannons of the cavalry units; even the 75-mm. and 76-mm. (3-inch) guns of the tanks and tank destroyers had to close to within 300 yards or less to do any damage to the frontal armor of the German machines.17 Contemporary American military doctrine regarded the tank primarily as an antiinfantry rather than an antitank weapon and, in the infantry-tank team, expected supporting tanks to engage enemy automatic weapons, while infantry dealt with opposing antitank gun crews, and artillery and tank destroyers handled enemy armor. In practice, however, even the self-propelled, turreted American tank destroyers found it difficult to close within effective firing range of German armor, while American artillery often had only a limited effect on such moving targets. Fighter-bombers were one answer, but they were affected by the weather, limited to the daytime, and dependent on good air-ground communications—something still lacking at the tactical unit level. As a result, small-unit commanders in the 3rd Division and other Allied infantry elements often could do little more than direct artillery and mortar fire on German armored units, at least keeping the German machines on the move and separating them from supporting infantry. Even bazooka fire could force the largest German tanks to keep their distance; although direct hits from any of the available American weapons might not destroy such machines, they often caused damage to treads, periscopes, radios, and other ancillary equipment, or at least shook up the German crews enough to make them leave. For the half-blinded German panzer troops, friendly infantry support was as vital to them as it was to the American tankers, for at close range even the smallest antitank weapons could immobilize the heaviest tank of the battlefield.

Fighting below the Colmar Canal on 30 January, for example, one 7th regiment private managed to KO (“knock out”) an advancing armored panzerjaeger by arcing his bazooka rocket high in the air, about 200 yards out, somehow hitting the vehicle on top and destroying it, a rather extraordinary feat—or tale. Later the same day, another 7th Infantry bazookaman inflicted similar damage on a Mark IV medium, firing at it point-blank from a window as it passed through a town the unit was attempting to secure. However, in this case a second German tank, obviously wiser, elected to withdraw about 1,000 yards

to the side of the town, content to pump high-explosive shells and machine-gun fire into the American positions despite their best efforts to chase it away with rocket and artillery fire. Fortunately for the 3rd Division, the Nineteenth Army had few such machines, partly because of the difficulty in fielding them. As the Americans already knew, the terrain of southern Alsace was not conducive to the employment of large armored formations.

For the 12th Armored Division, one of the least-experienced units in the American Army, which was still recovering from its initiation at Herrlisheim, the push from Colmar to Rouffach marked its transition to a veteran unit.18 Here the division’s mobile tank-infantry task forces had greater success, duplicating the combined arms tactics used by the 3rd Division units to the north. Dismounted infantry cleared the outskirts of each town before tanks and tank destroyers moved forward, with the tanks taking enemy automatic weapon positions under fire and the infantry probing for antitank mines and gun positions. Inside the town, infantry skirmish lines preceded each tank by twenty-five yards or more, attempting to secure all of the entrances to the town first (to prevent the arrival of reinforcements) before completely clearing the town itself. On the road, armored commanders led off with their latest model Shermans, with higher-velocity guns and more armor, and with their newer TDs (tank destroyers) in direct support, equipped with the very effective 90-mm. antitank cannons. Experience had taught them to leave wider gaps between vehicles and to stagger the gaps as well, allowing individual drivers to vary their speeds, thus preventing German antitank gunners from “leading” their target effectively. Placing artillery and even direct fire on possible enemy antitank sites also cut down on losses, as did switching the point, or lead, position between the most experienced crews. In this way the 12th Armored leapfrogged from town to town—one task force passing through an area secured by the other—until the junction was made with southern French forces, suffering relatively few casualties in the process. The experiences here would soon be put to good use in the final campaign to come.

In Retrospect

The struggle for the Colmar Pocket had few immediate implications for either Allied or German operations elsewhere. The formation of the pocket itself was almost an accident, a product of two factors: Eisenhower’s eagerness to have Patch’s Seventh Army turn north, and Hitler’s determination to hold on to at least a portion of southern Alsace at all costs. The resulting inability of the 6th Army Group to eliminate the pocket in December was perhaps inevitable. De Lattre’s First French Army was clearly superior to the German Nineteenth in terms of matériel and supplies but, when all was said and done,

probably greatly inferior in terms of trained manpower. The French lacked the command and control and the logistical apparatus to conduct a sustained offensive in the face of determined opposition, and even their combat leadership lacked the depth to sustain heavy losses on the battlefield within the ranks of junior officers and NCOs. Furthermore, the terrain and weather repeatedly dulled the cutting edge of their combat formations, making a repeat of the quick penetration that they had achieved south of Belfort (and at Saverne) in November extremely unlikely on the southern Alsatian plains. Perhaps it would have been better to leave a defensive holding force around Colmar in November and turn the bulk of the First French Army north along with Patch’s Seventh.

Eisenhower continued to hold Devers responsible for the Colmar Pocket, describing it during a visit to the 6th Army Group headquarters on 27 January as the only “sore” on his entire front and emphasizing the need to eliminate the enclave as soon as possible.19 The Supreme Commander was now more than willing to send assistance to both Patch and de Lattre, ultimately providing five American combat divisions (the 24th, 35th, and 75th Infantry, 10th Armored, and 101st Airborne) and 12,000 service troops to Devers by the end of the month. As might be expected, General Bradley, commanding the 12th Army Group, was upset by the transfer of combat forces south, feeling that Devers was “using up” all of his rested divisions, that the defensive efforts of the Seventh Army had been “poorly handled,” and that Eisenhower was probably trying to do too many things at once with the limited resources available.20 Devers, aware of the opinions of the 12th Army Group commander, noted only that his own forces had repeatedly supported the northern army groups when they were in trouble and that it was unfair to begrudge the 6th a few divisions when they were desperately needed.21

The cost of the Colmar battle was heavy on both sides. The 6th Army Group staff estimated American casualties around 8,000 and French losses about twice that number, but only some 500 American soldiers were killed in action; in both national components, disease and noncombat injuries accounted for almost a third of the losses and probably even more.22 The deep snow, freezing temperatures, and numerous water crossings caused a marked increase in trench foot and frostbite, and the mixed Franco-American casualty evacuation flow prevented medical services from keeping a precise tally of the toll taken by the weather. German casualty records are even more sparse than usual. During the operation, the 6th Army Group recorded 16,438 Germans taken prisoner in the Colmar area and obviously thousands more were killed or wounded, while nonbattlefield casualties from the weather may also have been high. On 10 February

the Nineteenth Army recorded over 22,000 permanent (killed or missing) casualties, and Rasp probably saved no more than 10,000 troops of all types.23 Certainly no more than 400 to 500 combat effectives from each of the eight divisions managed to escape across the Rhine. Allied losses of combat vehicles because of enemy action and mechanical breakdown were also high, but most were recoverable, while the German defenders lost most of what they had permanently. As an effective fighting force the Nineteenth Army had ceased to exist.

The high German losses were a direct result of the decision by Hitler and von Rundstedt to maintain the pocket as long as possible. By 1 February, despite standing orders to the contrary, General Rasp, the Nineteenth Army commander, had at least begun to deploy most of his forces out of the Vosges and to move service troops and damaged equipment east of the Rhine in expectation of a withdrawal order. The order never came. Hitler’s directions to stand fast in the pocket arrived at Army Group G headquarters at 1719 that night and were immediately passed on by telephone to the Nineteenth Army. Von Rundstedt fully supported the decision and, while approving a limited withdrawal from the Vosges, personally informed Rasp that he was to defend the northern and southern shoulders of the pocket with every man at his disposal.

Renewed Allied attacks on the 1st only increased the confusion in the German high command, as the appearances of first the U.S. 75th Infantry Division and then the 12th Armored Division were suddenly noted on the battlefield. On 3 February, as Allied forces were investing Neuf-Brisach and simultaneously driving south out of Colmar, Army Group G began proposing various contingency plans for a greatly reduced salient across the Rhine and at least a partial Nineteenth Army withdrawal to Germany. Hauser could not afford to lose all these forces, which would be desperately needed north of Alsace where the main Allied attack would inevitably come. Nevertheless, at 1940 that evening OKW again informed the German field commanders that the pocket was to be maintained at all costs and that the Nineteenth Army was to defend the shoulders of the pocket to the last man. There would be no withdrawal.

These final instructions from OKW remained unaltered to the end. By the 5th, neither Rasp nor his corps commanders could influence the battle or organize an orderly withdrawal. On the night of 5–6 February, OB West approved the Nineteenth Army’s plan for a final stand in the southeast corner of the pocket along the Rhone–Rhine Canal, but instructed it to delay any evacuation until the last possible minute. Nevertheless, between 6 and 9 February, Rasp took responsibility for starting to evacuate at least some of his equipment over the Rhine, either by ferry or over the Neuenburg bridge, while the bulk of what combat forces remained attempted

to fall back on Chalampe.24 On the night of 7–8 February the German high command again insisted that the bridgehead be held without thought of retreat; OKW had interpreted the redeployment of American forces from the battlefield after the fall of Neuf-Brisach as the end of the Allied offensive there. At that point, however, the Nineteenth Army had no control over the conduct of the battle, and what remained of the Colmar Pocket was no more than an enclave seven miles wide and two miles deep. Hitler’s permission to withdraw finally arrived at Army Group G headquarters at 1445 on the 8th and was transmitted to the Nineteenth Army by telephone shortly thereafter. But by that time the order served no purpose. The Nineteenth Army had been sacrificed for no appreciable gain.

Toward the Final Offensive

The battles of northern Alsace and those in the Colmar Pocket had seriously depleted the fighting capabilities of the German Army. During the last weeks of February and the first weeks of March, the 6th Army Group made final preparations to exploit this weakness during its forthcoming drive into Germany. In the First French Army zone, de Lattre’s forces swept the entire Colmar area, from the Vosges to the Rhine, and moved up to the more easily defensible Franco-German river border. Outposting the river with FFI units and a few regular formations, the French units finally had a chance to rest, recovering and repairing equipment that had begun to wear thin and absorbing new recruits into their units in much the same way as the Germans had been doing.

In the north, Patch’s Seventh Army made several limited attacks to improve its posture for future offensive operations. While the bulk of the VI Corps remained in place on the east-west Moder River line, the U.S. 36th Infantry Division on Brooks’ right, or eastern, wing pushed into the Gambsheim bridgehead area on 31 January to close up the slight indentation in the corps’ front line, finally retaking Rohnviller, Herrlisheim, Offendorf, and Gambsheim itself. Although assisted by CCB of the 14th Armored Division, flood conditions continued to limit the use of armor, and a shortage of munitions throughout the army group greatly reduced artillery support, thus turning what had been planned as a rapid, concentrated drive against weak units of the XIV SS Corps into a series of small, hard-fought infantry engagements that only ended on 11 February.25

To the north, the XV Corps also conducted a number of limited offensives in the Sarre valley region with the U.S. 70th, 63rd, and 44th Infantry

Divisions, seizing the heights above Saarbrucken as well as key terrain between Saarbrucken and Bitche. German forces opposite Haislip’s units offered only minimal resistance when engaged, briefly defending a few prepared strongpoints, such as the old Schlossberg fortress in the 70th Division’s zone of attack and the Bliesbrucken and Bellevue farm complexes in the zones of the 63rd and 44th. However, on both the Sarre valley and Gambsheim fronts, mines and booby traps took a high toll of American soldiers, as did the cold, wet weather.

For most of the 6th Army Group, the last days of winter were spent reorganizing and retraining, stocking supplies and equipment, improving local defensive positions, and planning for future operations across the German border. Unit commanders conducted formal training programs for new recruits in basic weaponry, map reading and use of the compass, and squad- and platoon-level tactics and worked new soldiers into their seasoned units; even veterans in rear areas performed range firing to resight weapons, while those on the front lines conducted periodic raids into German territory. The logistical buildup was critical. Food and, with the reduction in mobile operations, fuel supplies were adequate, but the general shortage in munitions forced Devers to drastically curtail almost all expenditures of large-caliber weapons and urgently request supplemental supplies from SHAEF. At the same time, to avoid a complete deterioration of the local French road network, the 6th Army Group had to place severe restrictions on vehicle speeds and loading, minimize the lateral movement of large units, and, whenever possible, rely more heavily on the French rail system. As the Riviera-based armies grew ever larger and plunged ever deeper into the European heartland, logistics remained critical. The Franco-American forces under Devers, Patch, and de Lattre had come a long way since the relatively simple landings in the sunny south and the heady drive up the Rhone River valley.

Properly fueled and supplied, the 6th Army Group was now a powerful fighting force and one that was still growing steadily in size and combat power. By the end of February all major American participants in the Colmar struggle had returned north, including the XXI Corps, the three infantry divisions, and the 12th Armored Division. In the ensuing reorganization, the Seventh Army returned the 10th Armored Division to the U.S. Third Army, the 101st Airborne Division to the SHAEF reserve, and eventually the 28th, 35th, and 75th Divisions to the 12th Army Group. For the moment at least, de Lattre retained control of the French 2nd Armored Division, while Patch kept the 3rd Algerian, and also received a new unit, the 6th Armored Division, to replace Leclerc’s force. In early March, after further shuffling and resting of these tired units, the Seventh Army had three corps with eight infantry divisions and one armored division on line as well as three infantry divisions and two armored divisions in reserve.26 South of

Strasbourg the First French Army could put two corps with three armored and four infantry divisions—all French—in the field. The 6th Army Group, now stronger than ever, was ready for the final offensive in Western Europe.27