Part Five: Decision at Midway

Blank page

Chapter 1: Setting the Stage: Early Naval Operations1

Early in January 1942 the U.S. Pacific Fleet was looking for a way to strike back at the Japanese; and advocates of the fast carrier force, believing their case ironically had been proven by the Japanese at Pearl Harbor, were ready to test their theories.2 But first there were some fences to mend. The all-important communications chain to Australia and New Zealand was rather tenuous, and the bulk of the Navy had to be used for escort duty until reinforcements could be put ashore to bolster some of the stations along the route.

One of the most important links in this communication chain was Samoa. The worst was feared for this area when the Pago Pago naval station was shelled by a Japanese submarine on 11 January while the 2nd Marine Brigade (composed for the most part of the 8th Marines and the 2nd Defense Battalion) still was en route to the islands from San Diego. But on 23 January after the Marines’ four transports and one fleet cargo vessel were delivered safely to Samoa, Vice Admiral William F. Halsey’s Enterprise force, together with a new fast carrier force commanded by Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher and formed around the Yorktown, were released for the raiding actions that the fleet was anxious to launch.

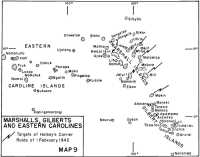

While the 2nd Marine Brigade unloaded at Samoa on 23 January, the Japanese landed far to me west at Rabaul where the small Australian garrison was quickly overrun. Although the importance of Rabaul to the Japanese was not realized at once, it was soon clear that from the Bismarcks the enemy could launch an attack through the Coral Sea toward Australia and New Zealand. This threat tended to increase rather than diminish the danger to Samoa. It was reasoned that a Japanese attack there would precede a strike at Australia or New Zealand to block U.S. Assistance to the Anzac areas. Japanese occupation of Makin Island in the Gilberts seemed to point toward Samoa, and naval commanders held that the best insurance against subsequent

Map 9: Marshalls, Gilberts and Eastern Carolines

moves would be a raid against the Marshalls, from which much of this Japanese action was mounted. Halsey’s Enterprise force therefor set out to strike Wotje and Maleolap, seaplane bases in the Marshalls, while Fletcher prepared to attack Mili and Jaluit (also in the Marshalls) plus Makin with his Yorktown group.

A submarine reconnaissance found the Marshalls lightly defended and spotted the largest concentration of Japanese planes and ships at Kwajalein Atoll in the center of the island group. Halsey decided to add this choice target to his list, and for the missions he divided Task Force 8 into three groups. The Enterprise with three destroyers would strike Wotje, Maloelap, and Kwajalein; Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance with the cruisers Northampton and Salt Lake City plus one destroyer would bombard Wotje; and Captain Thomas M. Shock in USS Chester, and with two destroyers, would shell Maloelap. The three southern atolls in the Marshalls group and Makin in the northern Gilberts would be attended to by Fletcher in the Yorktown with his independent command (TF 17) made up of the cruisers Louisville and St. Louis and four destroyers.

The twin attacks struck on 1 February. Halsey began launching at 0443 under a full moon when his carrier was just 36 miles from Wotje. Kwajalein, the main objective was 155 miles away. Nine torpedo bombers and 37 dive bombers led off the attack, the SBD’s striking Roi air base on the northern end of the atoll and the torpedo bombers hitting Kwajalein Island across the lagoon.

At Kwajalein the hunting was better; but in spite of the fact that there was no fighter opposition, and that the reports brought back by pilots were enthusiastic, damage to the Japanese installations and shipping was slight. Five Wildcats shot down two Japanese planes over Maloelap, and nine SBDs that returned from Roi later sortied again and damaged some airfield installations. The surface bombardment, too, was disappointing, and the bombardment flagship, Chester, took a light bomb through her main deck and lost eight men killed and eleven wounded.

To the south, Fletcher had bad luck over Jaluit when his fliers found their targets concealed by thunder showers. Two Japanese ships off Jabor Town were hit, but not sunk, and the damage ashore was slight. A mine layer was hit at Makin, and damage at Mili was also slight.

Similar actions were continued in other areas of the Pacific to harass the Japanese and to provide at least one outlet for efforts to fight back at the enemy when the news from all other fronts was gloomy. Most notable were strikes in early March against Wake and Marcus Island, and the daring raid by planes of Admiral Wilson Brown’s task force over New Guinea’s 15,000-foot Owen Stanley Mountains to hit the Japanese newly moved into Lae and Salamaua. But in all cases actual damage to the enemy still failed to measure up to expectations, much less to the reports turned in by overenthusiastic aviators.

Most audacious and unorthodox of the attacks, of course, was that which launched Lieutenant Colonel James H. Doolittle and his Army raiders from the Hornet’s deck to the 18 April Tokyo raid. Planned as “something really spectacular”—a proper retaliation for Pearl Harbor—the raid was designed more for its dramatic impact upon morale than for any other purpose. In that it was highly successful.

An army B-25, one of Doolittle’s Raiders, takes off from the deck of the carrier Hornet to participate in the first U.S. air raid on Japan (USN 41197)

Japanese carrier Shoho, dead in the water and smoking from repeated bomb and torpedo hits, was sunk by carrier planes in the Coral Sea Battle. (USN 17026)

After security-shrouded planning and training, Doolittle’s 16 B-25s left San Francisco on 2 April 1942 on board the Hornet which was escorted by cruisers Vincennes and Nashville, four destroyers, and an oiler. After a 13 April rendezvous with the Enterprise of Halsey’s TF 16, the raiding party continued along the northern route toward the Japanese home islands.3 Enemy picket boats sighted the convoy when it was more than 100 miles short of the intended launching range, and, with Doolittle’s concurrence, Halsey launched the fliers at 0725 on 18 April while the Hornet bucked in a heavy sea 668 miles from the Imperial Palace in central Tokyo.4

Much of the raid’s anticipated shock effect on Tokyo was lost by the coincidence of Doolittle’s arrival over the city at about noon just as a Japanese air raid drill was completed. The Japanese, confused by the attack which followed their own maneuvers, offered only light opposition to the B-25s which skimmed the city at treetop level to drop their bombs on military targets. One plane which struck Kobe received no opposition, although two others over Nagoya and Osaka drew heavy fire from antiaircraft batteries; but none was lost over Japan.

Halsey managed to retire from the launching area with little difficulty, and both carriers returned to Pearl Harbor on 25 April. Although the raid did more to boost American morale than it did to damage Japanese military installations, more practical results came later. It allowed a Japanese military group which favored a further expansion of their territorial gains to begin execution of these ambitious plans, and this expansion effort led directly to the Battle of Midway which “... alone was worth the effort put into this operation by ... [those] ... who had volunteered to help even the score.”5

The first of Japan’s planned expansion moves in the spring of 1942 aimed for control of the Coral Sea through seizure of the Southern Solomon Islands and Port Moresby on New Guinea as bases from which to knock out growing Allied air power in northeastern Australia. Seizure of New Caledonia, planned as part of the third step in the second major series of offensives, would complete encirclement of the Coral Sea. This would leave the U.S. communications route to the Anzac area dangling useless at the Samoan Islands; and later Japanese advances would push the U.S. Pacific Fleet back to Pearl Harbor and perhaps even to the west coast.

Characteristically, the Japanese plan called for an almost impossible degree of timing and coordination. It depended for success largely on surprise and on the U.S. forces behaving just as the Japanese hoped that they would. But this second element was largely corollary to he first, and, when surprise failed, the Japanese were shocked to discover that the U.S. fleet did not follow the script.

The Japanese anticipated resistance from a U.S. carrier task force known to be lurking somewhere to the south or southeast, but they expected to corner this force in the eastern Coral Sea with a pincers movement of carrier task forces of their own. Vice Admiral Takeo Takagi would skirt to the east of the Solomons with his Striking Force of heavy carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku and move in on the U.S. ships from that direction, while Rear Admiral Aritomo Goto’s Covering Force built around the light carrier Shoho would close in from the northwest. Destruction of the northeast Australian airfields would follow this fatal pinch of the U.S. fleet, and then the Port Moresby Invasion Group could ply the southeastern coast of New Guinea with impunity.

But Japanese overconfidence enabled U.S. intelligence to diagnose this operation in advance, and Fletcher’s Task Force 17 had steamed into the Coral Sea where he all but completed refueling before the first Japanese elements sortied from Rabaul. On 4 May Fletcher’s Lexington, Yorktown, screening ships, and support vessels were joined by the combined Australian-American surface force under Rear Admiral J.C. Crace of the Royal Navy.

On the previous day the Japanese had started their operation (which they called “Mo”) like any other routine land grab. A suitable invasion force, adequately supported, moved into the Southern Solomons, seized Tulagi without opposition6 and promptly began setting up a seaplane base. There Fletcher’s planes startled them next day with several powerful air strikes on the new garrison and on the Japanese ships still in the area. The U.S. carrier planes struck virtually unopposed,7 but they caused little damage in proportion to the energy and ammunition they expended. This startling deviation from the “Mo” script caused the Japanese to initiate the remaining steps of the operation without further delay.

The Battle of the Coral Sea proved the first major naval engagement in history where opposing surface forces neither saw nor fired at each other.8 Although both were eager to join battle, combat intelligence was so poor and aerial reconnaissance so hampered by shifting weather front that three days passed before the main forces found each other. But other things they did find led to a series of events on the 7th that might be described as a comedy of errors, although there was nothing particularly comical about them to those involved.

Early that morning an over-enthusiastic Japanese search pilot brought Takagi’s entire striking air power down on the U.S. fleet tanker Neosho and her lone convoying destroyer, the USS Sims, be reporting them as a carrier and heavy cruiser respectively. This overwhelming attack sank the Sims and so damaged the Neosho

that she had to be destroyed four days later.

Not to be outdone, the Americans reacted similarly a short time later to a scout plane’s report of two Japanese carriers and four cruisers north of the Louisiades. Actually these craft were subordinate enemy task group consisting of two old light cruisers and three converted gunboats. But more by good luck than good management, the attacking planes investigating the report sighted the Japanese Covering Force, then protecting the left flank of the Port Moresby Invasion Group, and concentrated on the Shoho to the virtual exclusion of her consorts. Against 93 aircraft of all types, the lone light carrier had no more chance than Task Force Neosho-Sims had against the Japanese, ad her demise prompted the morale-boosting phrase, “Scratch one flattop!”9

As a result of these alarms and excursions, both commanding admirals had missed each other once again. By midafternoon, however, Takagi had a pretty good idea of the U.S. carriers’ location and, shortly before nightfall, dispatched a bomber-torpedo strike against Fletcher. Thanks to a heavy weather front, these planes failed to find their target, and American combat air patrol intercepted them on their attempted return. In the confusion of dogfights, several Japanese pilots lost direction in the gathering darkness and made the error of attempting to land on the Yorktown.10

Early the following morning, U.S. search planes finally located the Japanese carriers at about the time the Japanese rediscovered the U.S. flattops. As last the stage was set for the big show.

Loss of the Shoho had cut the Japanese down to size. The opponents who slugged it out on 8 May 1942 were evenly matched, physically and morally, to a degree rarely found in warfare, afloat or ashore.11 However, at the time the battle developed, the Japanese enjoyed the great tactical advantage of having their position shrouded by the same heavy weather front that had covered the U.S. carriers the previous afternoon, while Fletcher’s force lay in clear tropical sunlight where it could be seen for many miles from aloft.

The attacking aircraft of both parties struck their enemy at nearly the same time (approximately 1100), passing each other en route.12 The two Japanese carriers and their respective escorts lay about ten miles apart. As the Yorktown’s planes orbited over the target preparatory to the attack, the Zuikaku and her screening force disappeared into a rain squall and were seen

no more during the brief action that followed, thereby escaping damage. So all U.S. planes that reached the scene concentrated on the Shokaku, but with disappointing results.

The Yorktown’s torpedo bombers went in first, low and covered by fighters. But faulty technique and the wretched quality of U.S. torpedoes at the stage of the war combined to make this attack wholly ineffective: hits (if any) proved to be duds, the pilots launched at excessive ranges, and the torpedoes traveled so slowly that vessels unable to dodge had only to outrun them. The dive bombers, following closely, scored only two direct hits. But one of these so damaged the Shokaku’s flight deck that she could no longer launch planes, although she still was capable of recovering them. Many of the Lexington’s planes, taking off ten minutes after those from Yorktown, go lost in the overcast and never found their targets. Those that did attack made the same mistakes the Yorktown fliers committed. The torpedoes proved wholly ineffective, and the damaging bomb hit on the Shokaku was something less than lethal despite the pilot’s enthusiastic report that she was “settling fast.”13

The Japanese did considerably better, thanks to vastly superior torpedoes and launching techniques. Two of the power “fish” ripped great holes in the Lexington’s port side, and she sustained two direct bomb hits plus numerous near misses that sprang plates. The more maneuverable Yorktown dodged all of the torpedoes aimed at her and escaped all but one of the bombs. But this was an 800-pounder, and it exploded with such a spectacular display of flame and smoke that the Japanese pilots may be excused their claim that they had sunk her.

These events made up the Battle of the Coral Sea. It was all over by 1140.

Preoccupation of both forces with the flattops left opposing escort vessels unscathed, although the Japanese claimed to have left burning “one battleship or cruiser.”14 The Americans had sustained far the heavier damage and casualties, but had inflicted the greater tactical blow in knocking the Shokaku out of further offensive action while both U.S. carriers still were operational. Even the crippled Lexington had put out fires, shored up torpedo damage, and was capable of sustaining 25-knot speed and conducting nearly normal flight operations an hour after the battle ended.

The Japanese had lost the greater number of planes: 43 from all causes against 33 for the Americans. Their command, accepting at face value the ecstatic reports of their pilots that they had sunk both U.S. carriers, started the beat-up Shokaku for home, and in the afternoon commenced withdrawal from the area on orders from Rabaul. Admiral Takagi concurred with higher authority that it would be unwise to risk the vulnerable transport convoy in the narrowing waters of the western Coral Sea in face of the Allies’ Australian airfields under cover of the whittled-down air complement of the single operational carrier. So the Port Moresby Invasion Group was ordered back to Rabaul.

But the final, tragic act of the drama remained. The gallant old Lexington, her wounds patched up and apparently fit to return to Pearl Harbor for permanent repairs, was suddenly racked by a terrible

explosion. This resulted only indirectly from enemy action: released gasoline fumes were ignited by sparks from a generator someone had carelessly left running. This set off what amounted to a chain reaction. The best efforts of her crew availed nothing, and at 1707 her skipper gave the order to abandon ship. This movement was carried out in the best order, without the loss of a man. At about 2000, nearly nine hours after the Japanese had withdrawn from the battle, torpedoes of her own escort put her under the waves forever.

Loss of the Lexington gave tactical victory to the Japanese, But by thwarting the invasion of Port Moresby, principal objective of the entire operation, the United States won strategic victory. At the time the enemy regarded this merely a postponement of their invasion plans; but events would prove that no Japanese seaborne invasion ever would near Port Moresby again.