Chapter 4: The Battle of the Tenaru

With naval support gone, about the only hope was the airfield. Shipping would need air cover before regular runs could bolster the Marines’ slim supply levels, and time was of the essence. If the Japanese struck hard while the landing force was abandoned and without air support, the precarious first step toward Rabaul might well have to be taken all over again. Vandegrift centered his defense at the field and gave completion of the strip top priority equal to the task of building the perimeter’s MLR.

On 8 August, almost as soon as the field was captured, Lieutenant Colonel Frank Geraci, the Division Engineer Officer, and Major Kenneth H. Weir, Division Air Officer, had made an inspection of the Japanese project and estimated the work still needed. They told Admiral Turner that 2,600 feet of the strip would be ready in two days, that the remaining 1,178 feet would be operational in about two weeks. Turner said he would have aircraft sent in on 11 August. But the engineer officer had made his estimate before the transports took off with this bulldozers, power shovels, and dump trucks.1

Again, however, the Marines gained from the Japanese failure to destroy their equipment before fleeing into the jungle. Already the U.S. forces were indebted to the enemy for part of their daily two meals, and now they would finish the airfield largely through the use of enemy tools. This equipment included nine road rollers (only six of which would work), two gas locomotives with hopper cars on a narrow-gauge railroad, six small generators (two were damaged beyond repair), one winch with a gasoline engine, about 50 hand carts for dirt, some 75 hand shovels. and 280 pieces of explosives.

In spite of this unintentional assistance from the Japanese, the Marine engineers did not waste any affection on the previous owners of the equipment. The machinery evidently had been used continuously for some time with no thought of maintenance. Keeping it running proved almost as big a job as finishing the airfield, and one of the tasks had to be done practically by hand, anyway. The Japanese had started at each end of the airstrip to work toward the middle, and the landing had interrupted these efforts some 180 to 200 feet short of a meeting. Assisted by a few trucks and the narrow gauge hopper cars (which had to be loaded by hand), engineers, pioneers, and others who could be spared moved some 100,000 cubic feet of fill and spread it on this low spot at midfield. A steel girder the Japanese had intended to use in a hangar served as a drag, and a Japanese road roller flattened and packed the fill after it had been spread.

Problems facing the infantry troops were just as great. There had been no impressive ground action on Guadalcanal since the landing, but intelligence in the immediate vicinity as well as in the South Pacific in general was not yet able to indicate when, how, and where Japanese reaction would strike. Estimating a counterlanding to be the most probable course of Japanese action, General Vandegrift placed his MLR at the beach. There the Marines built a 9,600-yard defense from the mouth of the Ilu River west around Lunga Point to the village of Kukum. The Ilu flank was refused 600 yards inland on the river’s west bank, and at Kukum the left flank turned inland across the flat land between the beach and the first high ground of the coastal hills. The 5th Marines (less one battalion) held the left sector of the line from Kukum to the west bank of the Lunga, and the remainder of the line (inclusive of the Lunga) was held by the 1st Marines.

The line was thin. The bulk of the combat forces remained in assembly areas inland as a ready reserve to check attacks or penetrations from any sector. Inland (south) of the airfield, a 9,000-yard stretch of rugged jungle terrain was outposted by men from the artillery, pioneer, engineer, and amphibian tractor battalions. These men worked during the day and stood watch on the lines at night.

The workers on the airfield as well as those on the thin perimeter were under almost constant enemy observation. Submarines and destroyers shelled the area at will day or night. Large flights of high-level bombers attacked the airfield daily, and observation planes were continually intruding with light bombs and strafing attacks. At night the enemy patrols became increasingly bold, and troops on the MLR mounted a continuous alert during the hours of darkness. South of the airfield the outpost line had to be supplemented by roving patrols.

In spite of this harassment, the perimeter shaped up. The 1st Special Weapons Battalion dug in its 75-mm tank destroyers (half-tracks) in positions inland from the beach, but kept them ready to move into prepared positions near the water. Howitzers of the 11th Marines were situated to deliver fire in all sectors. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the artillery regiment had 75-mm pack howitzers and the 5th Battalion had 105-mm howitzers. There were no 155-mm howitzers or guns for counterbattery, there was no sound-flash equipment for the location of enemy batteries, and the 3rd Defense Battalion had not had a chance to unload its 5-inch seacoast guns or radar units prior to the departure of the amphibious shipping. Air defense within the perimeter also was inadequate. There were 90-mm antiaircraft guns ashore, but the restricted size of the perimeter kept them too close to the field for best employment.

It was a hazardous and remote toe-hold which the Marines occupied, and within the Pacific high command there were some grave doubts whether they could hang on. Major General Millard F. Harmon said to General Marshall in a letter on 11 August:–

The thing that impresses me more than anything else in connection with the Solomon action is that we are not prepared to follow up. ... We have seized a strategic position from which future operations in the Bismarcks can be strongly supported. Can the Marines hold it? There is considerable room for doubt.2

Admiral Ghormley, also concerned about the precarious Marine position,3 on 12 August ordered Admiral McCain’s F 63 to employ all available transport shipping to take aviation gasoline, lubricants, ammunition, bombs, and ground crews to Guadalcanal. To avoid Japanese air attacks, the ships were to leave Espiritu Santo in time to reach Sealark Channel late in the day, unload under cover of darkness, and depart early the following day.

For the “blockade run” to Guadalcanal, Admiral McCain readied four destroyer transports of TransDiv 12. They were loaded with 400 drums of aviation gasoline, 32 drums of lubricant, 282 bombs from 100- to 500-pounders, belted ammunition, tools, and spare parts. Also on board were five officers and 118 Navy enlisted men from a Navy construction base (Seabee) unit, Cub-1. Under the command of Major C. H. Hayes, executive officer of VMO-251, this unit was to aid the Marine engineers in work at the field and to serve as ground crews for fighters and dive bombers scheduled to arrive within a few days.

McCain’s ships arrived off Guadalcanal during the night of 15 August, and the equipment and men were taken ashore. By this time the Marine engineers had filled the gap in the center of the landing strip and now labored to increase the length of the field from 2,600 feet to nearly 4,000 feet. Work quickened after the Seabees landed, but there was no steel matting and the field’s surface turned to sticky mud after each of the frequent tropical rains.

General Harmon blamed a faulty planning concept for the serious shortages of tools, equipment, and supplies. The campaign, he said, “... had been viewed by its planners as [an] amphibious operation supported by air, not as a means of establishing strong land based air action.”4

But in spite of these shortages at the airfield and elsewhere, the Lunga Point perimeter was taking on an orderly routine of improvement and defense. Motor transport personnel had put their meager pool of trucks into operation shortly after the landing, and they had added some 35 Japanese trucks to he available list. Pioneers had built a road from the airfield to the Lunga River where they erected a bridge to the far side of the perimeter. Supply dumps also had been put in order. The pioneers cleared the landing beach, moving gear west to the Lunga-Kukum area, and sorted and moved Japanese supplies. The old Japanese beach at Kukum was cleaned up and reconditioned to receive U.S. material.

Most of the work of moving the beach dumps to permanent sites was completed in four days. There was a great amount of tonnage to handle in spite of the fact that only a small portion of the supplies had been landed. Amphibian tractors and all available trucks, including the Japanese, were used. The Government Track (the coastal road to Lunga) was improved and streams and rivers bridged to speed truck traffic. The amphibians carried their loads just offshore through shallow surf, and farther out to sea the lighters moved from old beach to new and back

again. The amount of supplies at each of the new classified dumps was kept low to avoid excessive loss from bombardment.

Captured material included almost every type item used by a military force—arms, ammunition, equipment, food, clothing, fuel, tools, and building materials:–

As the division was acutely short of everything needed for its operation, the captured material represented an important if unforeseen factor in the development of the airfield and beach defenses and the subsistence of the garrison.5

The landing force was particularly short of fuel, but in this case the supply left behind by the Japanese garrison was not as helpful as it might have been. Marines found some 800 to 900 drums of Japanese aviation gasoline on Guadalcanal, but this 90-octane fuel was not quite good enough for our aircraft, and it was too “hot” and produced too much carbon in trucks and Higgins boats unless mixed evenly with U.S. 72-octane motor fuel. Likewise some 150,000 gallons of Japanese motor fuel of 60 or 65 octane proved unreliable in our vehicles although some of it was mixed with our fuel and used in emergency in noncombat vehicles.

So critical was the supply of gasoline and diesel fuel that the division soon adopted an elaborate routine of “official scrounging” from ships that came into the channel. Rows of drums were lined bung up on old artillery lighters, and these craft would wallow alongside ships where Marines would ask that a hose from the ships’ bulk stores be passed over so they could fill the drums one at a time. This method helped the Marines’ fuel supply, but not relations with the Navy. Small boats taking off supplies had difficulty negotiating their passes alongside with the unwieldy lighters in the way, and ships officers quite frequently took a dim view of dragging along such bulky parasites when they had to take evasive action during the sudden air raids. But the system often worked well when early preparations were made with particularly friendly ships.

This over-water work in Sealark Channel, maintaining contact between Tulagi and Guadalcanal as well as meeting the supply ships which began to sneak in more frequently, pointed to another serious deficiency: there was no organized boat pool available to the division. more often than not the personnel and craft that the division used in those early days had merely been abandoned when the attack force departed, and there was no semblance of organization among them. Even the creation of order did not solve all the problems. A high percentage of the boats were damaged and crewmen had no repair facilities. The situation was gradually improved but was never satisfactory.

At last, on 18 August, the engineers and Seabees had a chance to stand back and admire their work. The airfield was completed. On 12 August it had been declared fit for fighters and dive bombers, but none were immediately available to send up. A Navy PBY had landed briefly on the strip on that date., but this was before Admiral McCain made his initial blockade run, and there was very little fuel for other planes anyway. But by the 18th the fill in the middle had been well packed, a grove of banyan trees at the end of the strip had been blasted away to make the approach less steep, and newly arrived gasoline and ordnance were ready and waiting for the first customers. In the South Pacific during that period of shoestring existence,

Marine commanders on Guadalcanal appear in a picture taken four days after the landing which includes almost all the senior officers who led the 1st Marine Division ashore

Left to right, front row: Col George R. Rowan, Col Pedro A. del Valle, Col William C. James, MajGen Alexander A. Vandegrift, Col Gerald C. Thomas, Col Clifton B. Cates, LtCol Randolph McC. Pate, and Cdr Warwick T. Brown, USN. Second row: Col William J. Whaling, Col Frank B. Goettge, Col LeRoy P. Hunt, LtCol Frederick C. Biebush, LtCol Edwin A. Pollock , LtCol Edmund J. Buckley, LtCol Walter W. Barr, and LtCol Raymond P. Coffman. Third row: LtCol Francis R. Geraci, LtCol William E. Maxwell, Col Edward G. Hagen, LtCol William N. McKelvy, LtCol Julian N. Frisbee, Maj Milton V. O’Connell, Maj William Chalfont, III, Capt Horace W. Fuller, and Maj Forest C. Thompson. Fourth row: Maj Robert G. Ballance, Maj Henry W. Buse, Jr., Maj James G. Frazer, Maj Henry H. Crockett, LtCol Leonard B. Cresswell, LtCol John A. Bemis, Maj Robert B. Luckey, LtCol Samuel G. Taxis, and LtCol Eugene H. Price. Last row: Maj Robert O. Bowen, LtCol Merrill B. Twining, Maj Kenneth W. Benner (behind Bemis), LtCol Walker A. Reeves, LtCol John DeW. Macklin, LtCol Hawley C. Waterman, and Maj James C. Murray. Many of these men went on to become general officers and three of them (Vandegrift, Cates, and Pate) later became Commandants of the Marine Corps. (USMC 50509)

however, “readiness” was a comparative thing. There were no bomb handling trucks, carts or hoist, no gas trucks, and no power pumps.

The state of readiness had a way of fluctuating rapidly, too, and the breathing spell for the workers did not last long. With most sadistic timing, a large flight of Japanese planes came over and scored 17 hits on the runway. One engineer was killed, nine were wounded, and the field “was a mess.”6

The runway damage was disquieting but not altogether a surprise. Air raids had been frequent, shelling from offshore submarines likewise was common, and planes droned overhead frequently during the hours of darkness to drop small bombs here and there at well-spaced intervals. After the big raid on the 18th, the well-practiced repair teams merely went to work again. In filling the craters, the engineers and Seabees first squared the holes with hand shovels and then air hammered the new dirt solid by tamping every foot and a half of fill. They had found that this system kept settling to a minimum and prevented dangerous pot holes.

Two days later Henderson Field, named after Major Lofton Henderson, a Marine aviator killed at Midway, was again ready. And this time the planes arrived. The forward echelon of Marine Aircraft Group 23, the first arrivals, numbered 19 F4Fs and 12 SBD-3s. The units were under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Charles L. Fike, executive officer of the air group. The F4Fs, a part of Marine Fighter Squadron 223, were commanded by Major John L. Smith, and the 12 Douglas dive bombers from Marine Scout-Bomber Squadron 232 were led by Lieutenant Colonel Richard D. Mangrum.

Arrival of planes ended an era for the Guadalcanal defenders—the hazardous period from 9 to 210 August when the landing force operated entirely without air or surface support. During this period lines of communications were most uncertain. Nothing was known of the general naval situation or the extent of losses at sea, and little information was received from aerial reconnaissance from rear areas. Ashore, patrolling was constant, but the terrain was such that much could be missed. Short rations, continuous hard work, and lack of sleep reflected in the physical condition of the troops. Morale, however, remained high.

Formed in March of 1942 at Ewa, Oahu, MAG-23 remained in training there, with much shifting of personnel and units, until this two-squadron forward echelon sailed to the South Pacific on 2 August on board the escort carrier Long Island. Smith’s men had just been issued new F4Fs with two-stage superchargers, and Mangrum’s unit had turned in its old SBD-2s for the newer 3s with self-sealing gasoline tanks and armor plate. The remaining two squadrons of the group, Captain Robert E. Galer’s VMF-224 and Major Leo R. Smith’s VMSB-231, would sail from the Hawaiian area on 15 August.

John Smith’s VMF-223 and Mangrum’s VMSB-232 came down by way of Suva in the Fijis and Efate in the New Hebrides. At Efate, Smith traded some of his young, less-experienced pilots to Major Harold W. Bauer’s VMF-212 for some fliers with more experience. On the afternoon of 20 August, the Long Island stood 200 miles southeast of Guadalcanal and launched the planes.

Two days later, on 22 August, the first Army Air Force planes, five P-400s7 of the 67th Fighter Squadron, landed on the island. On 24 August, 11 Navy dive bombers from the battle-damaged Enterprise moved to Henderson Field to operate for three months, and on 27 August nine more Army P-400s came in. Performance of these Army planes was disappointing. Their ceiling was 12,000 feet because they had no equipment for the British high-pressure oxygen system with which they were fitted, and they could not reach the high-flying enemy planes. Along with the Marine SBDs, the P-400s spent their time during Japanese air raids off strafing and bombing ground targets, and they returned to Henderson after the hostile planes departed.

A short while later—early in September—supply and evacuation flights were initiated by two-engined R4Ds (C-47s) of Marine Aircraft Group 25. Flying daily from Espiritu Santo and Efate, the cargo planes each brought in some 3,000 pounds of supplies and were capable of evacuating 16 stretcher patients.

Although this increased air activity at Henderson Field was of great importance to the operation in general and the combat Marines in particular, the field still was not capable of supporting bombers which could carry attacks to Japanese positions farther to the north. On 20 August General Harmon voiced the opinion that it would be too risky to base B-17s at Henderson until more fighter and antiaircraft protection were available.8

Early in September he suggested that heavy bombers stage through the Guadalcanal field from the New Hebrides and thus strike Rabaul and other Japanese bases,9 but a closer investigation pointed up the impracticality of this plan. It would have meant hand-pumping more the 3,500 gallons of gasoline into each bomber landing at Guadalcanal on the 1,800-mile round trip from the New Hebrides to the Northern Solomons; and although this manual labor was not too great a price to pay for an opportunity to strike at the Japanese, it was impossible to maintain a fuel stock of that proportion at Henderson Field.

Ground Action

Combat troops meanwhile probed the jungles with patrols, and early reconnaissance indicated that the bulk of Japanese troops was somewhere between the Matanikau River, about 7,000 yards west of the Lunga, and Kokumbona, a native village some 7,500 yards west of the Matanikau. General Vandegrift wanted to pursue the enemy and destroy him before the Japanese could reinforce this small, disorganized garrison, but no substantial force could be spared from the work of building the MLR and the airfield.

Minor patrol clashes occurred almost daily, but many of these meeting engagements were with wandering bands of uniformed laborers who only confused attempts to locate the main enemy force. This patrolling gradually revealed that the area between the Matanikau and Kokumbona was the main stronghold, however, Stiff resistance continued there with each attempt to probe the area, and this

pattern had started as early as 9 August when one officer and several enlisted men were wounded while trying to cross the river. This patrol had reported the west bank of the river well organized for defense. The enemy kept shifting his position, though, to maneuver for an advantage against the patrols which came to seek him out. Final confirmation of the enemy location came on 12 August when a Japanese warrant officer captured behind the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines said that his unit was between the Matanikau and Kokumbona.

Under questioning, the prisoner admitted that possibly some of his fellow garrison mates were wandering aimlessly through the jungle without food and that some of them might surrender. First Sergeant Stephen A. Custer of the division intelligence section made plans to lead an amphibious patrol to the area. Meanwhile, a Marine patrol reported seeing what it took to be a white flag west of the river. Hearing these reports, Lieutenant Colonel Frank Goettge, division intelligence officer, decided to lead the patrol himself.

The original plan had called for an early start so that a daylight landing could be made. The patrol then would work inland along the west bank of the Matanikau and bivouac for the night far back in the hills. The second day was to be spent in a cross-country return to the perimeter. The primary mission of the patrol would be that of reconnaissance, but it was to be strong enough for combat if it ran into a fight.

Colonel Goettge’ new plans delayed departure of the patrol about 12 hours and cut down its combat potential by including among its 25-man strength Lieutenant Commander Malcolm L. Pratt, assistant division surgeon, Lieutenant Ralph Cory, a Japanese linguist, and several members of the 5th Marines intelligence section. The boat got away from the perimeter at about 1800 and landed after dark at 2200 at an undetermined point west of the Matanikau. The Japanese, instead of surrendering, attacked the patrol and cut off from the beach all but three men who escaped back into the surf to swim and wade to safety.

One of these men, Sergeant Charles C. Armdt, arrived in the perimeter at about 0530 on 13 August to report that the patrol had encountered enemy resistance. Company A, 5th Marines set off immediately as a relief patrol to be reinforced later by two platoons of Company L and a light machine-gun section. Meanwhile, the other two escaped patrol members, Corporal Joseph Spaulding and Platoon Sergeant Frank L. Few, came back at 0725 and 0800 respectively and revealed that the remainder of the Goettge patrol had been wiped out.

The relief patrol landed west of Point Cruz, a coastal projection a short distance west of the Matanikau’s mouth. Company A moved east along the coastal road back toward the perimeter while the reinforced platoons of Company L traveled over the difficult terrain inland from the beach. Company A met brief Japanese resistance near the mouth of the river, but neither force found a trace of the Goettge patrol.10

This action was followed a week later by a planned double envelopment against the village of Matanikau. Companies B and L of the 5th Marines would carry out

Marine engineers erected this bridge across the Tenaru River to speed the flow of troops and supplies from the beaches to the perimeter. (USMC 50468-A)

Solomons natives, recruited by Captain W.F. Martin Clemens, BSIDF, guide a patrol up the winding course of the Tenaru River in search of Japanese. (USMC 53325)

this attack while Company I of the same regiment made an amphibious raid farther west, at Kokumbona, where it was hoped that any Japanese retreating from Matanikau could be cut off. On 18 August Company L moved inland, crossed the Matanikau some 1,000 yards from the coast, and prepared to attack north into the village the next day. Company B, to attack west, moved along the coastal road to me east bank of the river.

Next day, after preparation fire was laid down by the 2nd, 3rd, and 5th Battalions of the 11th Marines, Company L launched its attack. Shortly after jumping off, scouts discovered a line emplacements along a ridge some 1,000 yards to he left flank of the company front. The platoon on this flank engaged the small enemy force in these emplacements while the remainder of the company moved on toward the village. In this action off the left flank, Sergeant John H. Branic, the acting platoon leader was killed. The company executive officer, Lieutenant George H. Mead, Jr. next took command. When he was killed a short time later Marine Gunner Edward S. Rust, a liaison officer from the 5th Marines headquarters took command. This platoon continued to cover the advance of the remainder of the company.

Company B, thwarted in its attempt to cross the river because of intense Japanese fire from the west bank, could only support the attack of its sister company by fire. Company L managed to reach the outskirts of the native village at about 1400, however, and one platoon entered the settlement. This platoon lost contact with the remainder of the company, and when the other platoons attempted to enter the village they were met by a strong Japanese counterattack which caused the separated platoon to withdraw to company lines. The Marines were nearly enveloped and succeeded in repulsing the attack only after close-range fighting. Defending in depth, the Japanese drew up on a line which extended from the river some 200 yards west through the village. While the Marines maneuvered for an attack, the Japanese fire became more sporadic, and an assault at about 1600 revealed that the enemy pocket had dispersed.

Meanwhile the amphibious raid of Company I also aroused opposition. Two enemy destroyers and a cruiser lobbed shells at the landing craft while they swung from the Marine perimeter to Kokumbona, and the raiding party escaped this threat only to be met at the beach by Japanese machine-gun fire. The landing succeeded, however, and the enemy resistance began to melt. By the time a Marine attack swept through the village, the defenders had retired into the jungle to avoid a conclusive engagement. The three companies killed 65 Japanese while suffering the loss of four Marines killed and 11 wounded.

Although these actions served only to located the general area into which the original Japanese garrison of Guadalcanal had withdrawn in the face of the Marine landing, another patrol on 19 August indicated the pattern of things to come on the island.

The patrol and reconnaissance area assigned to the 1st Marines lay east and southeast of the perimeter where the plains of the Lunga fan into a grassy tableland which is nearly eight miles wide near the coastal village of Tetere. Some thought had been given to the construction of an airfield there, and on 12 August a survey party went out with a platoon-sized security force under Second Lieutenant John J. Jachym. Passing through a native village on 13 August, this group encountered Father Arthur C. Duhamel, a young Catholic

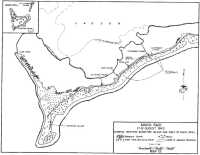

Map 12: Makin Raid

priest from Methuen, Massachusetts,11 who related native rumors of an enemy force along the coast to the east.

Two days later a partial verification of the priest’s information was made by Captain (of the British Solomons Islands Defense Force) W. F. M. (Martin) Clemens, the district officer who had withdrawn into the hills to become a coastwatcher when the Japanese entered his island. On 14 August Clemens left his watching station near Aola Bay with his 60 native scouts12 and entered the Marine perimeter. Clemens and his scouts reported seeing signs of a new Japanese force. And on the heels of Clemens’ reports came word from Admiral Turner that naval intelligence indicated a Japanese attack in force.

To investigate, Captain Charles H. Brush, Jr. took a part of his Company A of the 1st Marines and at 0700 on 19 August began a patrol eastward along the coastal track toward Koli Point and Tetere. At about noon near Koli Point the patrols spotted a group of four Japanese officers and 30 men moving, with no security to front or flanks, between the road and the beach. Captain Brush struck frontally with a part of his unit while Lieutenant Jachum led and envelopment around the enemy left flank. In 55 minutes of fighting, 31 of the Japanese were killed. The remaining three escaped into the jungle. Three Marines were killed and three wounded.

It was clear that these troops were not wandering laborers or even members of the original garrison. Helmets of the dead soldiers bore the Japanese Army star rather than the anchor and chrysanthemum device of the special landing force. A code for ship-to-shore communications to be used for a landing operation also was found among the effects, and the appearance of the uniforms indicated that the troops were recent arrivals to Guadalcanal. There appeared little doubt that the Japanese were preparing an attempt to recapture their lost airfield. And Brush found they had already completed some excellent advance work:

With a complete lack of knowledge of Japanese on my part, the maps the Japanese had of our positions were so clear as to startle me. They showed our weak spots all too clearly.13

While these patrols searched for the enemy on Guadalcanal, another force of approximately 200 Marines moved into enemy waters farther north and raided a Japanese atoll in the Gilbert Islands. Companies A and B of Lieutenant Colonel Evans F. Carlson’s 2nd Raider Battalion went from Oahu to Makin atoll on board submarines Argonaut and Nautilus and landed on the hostile beach early on 17 August. The raid was planned to destroy enemy installations, gather intelligence data, test raiding tactics, boost home front morale, and possibly to divert some Japanese attention from Guadalcanal. It was partially successful on all of these counts, but its greatest asset was to home-front morale. At a cost to themselves of 30 men lost, the raiders wiped out the Japanese garrison of about 85 men, destroyed radio

stations, fuel, and other supplies and installations, and went back on board their submarines on 18 August for the return to Pearl Harbor. This raid attracted much attention in the stateside press but its military significance was negligible. Guadalcanal still held the center of the stage in the Pacific and attention quickly turned back to that theater.14

Battle of the Tenaru15

The picture that began to take shape as these bits of intelligence fitted together provided an early warning of Japanese plans that already were well underway. On 13 August, Tokyo ordered Lieutenant General Haruyoshi Hyakutake’s Seventeenth Army at Rabaul to take over the ground action of Guadalcanal and salvage the situation. The naval side of this reinforcement effort would be conducted by Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka, a wily Imperial sea dog who was a veteran of early landings in the Philippines and Indonesia and of the battles of Coral Sea and Midway. With no clear picture of his opponent’s strength, Hyakutake decided to retake the Lunga airfield immediately with a force of about 6,000 men. On the evening of the 15th of August, while Tanaka’s ships of the reinforcement force were loading supplies at Truk, the admiral got orders to hurry down to Rabaul and take 900 officers and men to Guadalcanal at once. Hyakutake had decided that the attack would begin with a part of the 7th Division’s 28th Infantry Regiment and the Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force. These units would be followed by the 35th Brigade.

Admiral Tanaka thought he was being pressed a little too hard, considering that the Eighth Fleet under which he operated had just been formed at Rabaul on 14 July, and that the admiral himself had hardly been given time to catch his breath after hurrying away from Yokosuka for his new job on 11 August. The admiral reported later:–

With no regard for my opinion ... this order called for the most difficult operation in war—landing in the face of the enemy—to be carried out by mixed units which had no opportunity for rehearsal or even preliminary study. ... In military strategy expedience sometimes takes precedence over prudence, but this order was utterly unreasonable.

I could see that there must be great confusion in the headquarters of Eight Fleet. Yet the operation was ordained and underway, and so there was no time to argue about it.16

Backbone of the initial effort would consist of the reinforced 2nd Battalion, 28th Infantry, a 2,000-man force of infantry, artillery, and engineers under the command of Colonel Kiyono Ichiki. This force had been en route to Midway when the defeat of the Japanese carriers caused a change to Guam.17 Later the Ichiki Force was en route back to the home islands when the Marine landing in the Solomons brought another change of

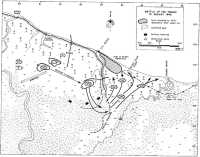

Map 16: The Perimeter, 12 August 1942

Japanese plans. The unit was diverted to Truk where it landed on 12 August and was attached to the 35th Brigade which then garrisoned the Palau Islands. The brigade’s commander was major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi. The 900 or 1,000 men which Admiral Tanaka loaded for his first reinforcement run to Guadalcanal were from this Ichiki unit.

The reinforcement ships landed Colonel Ichiki and this forward echelon at Taivu Point on Guadalcanal during the night of 18 August. While this force landed at this point some 22 air miles east of the Lunga, some 500 men of the Yokosuka Fifth Special Naval Landing Force arrived at Kokumbona. This was the first of many runs of the Tokyo Express, as Marines called the Japanese destroyers and cruisers which shuttled supplies and reinforcements up and down The Slot in high-speed night runs. Brush’s patrol had encountered part of Ichiki’s forward echelon, and the Japanese commander, shaken by the fact that he had been discovered, decided to attack at once.

At that time the Marines had five infantry battalions available for defense of Lunga Point. Four battalions were committed to beach defense, one was withheld in division reserve. On 15 August work had begun on a new extension of the right flank by refusing it inland along the west bank of the Ilu River (then called the Tenaru) for a distance of 3,200 yards. This plan involved road and bridge construction as well as extensive clearing before field fortifications could be built. As of 18 August little progress had been made.

In the face of the threats pointed out by intelligence sources, the division considered two courses of action: first, to send the division reserve across the Ilu to locate and destroy the enemy, or second, to continue work on defensive positions while limiting actions to the east to strong patrols and outposts. The first course, General Vandegrift realized, involved accepting the premise that the main Japanese force had landed to the east and that it could be dealt with by one Marine battalion. But if Brush’s patrol had encountered only a small part of the new enemy unit while the bulk of the force stood posed to strike from another direction, or from the sea, absence of the reserve battalion would become a serious manpower shortage in the perimeter. The intelligence Vandegrift had gleaned form all sources was good, but there wasn’t enough of it. So the division sat tight to await developments. Work continued on field fortifications, native scouts worked far to the east, and Marines maintained a strong watch on the perimeter each night.

The Marines did not have long to wait. Colonel Ichiki had wasted no time preparing his attack, and during the night of 20-21 August Marine listening posts on the east bank of the Ilu detected enemy troops moving through the jungle to their front. A light rattle of rifle fire was exchanged, both sides sent up flares, and the Marines withdrew across the river mouth to the lines of their battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Edwin A. Pollock’s 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines. They reported that a strong enemy force appeared to be building up across the river.18

Map 17: Battle of the Tenaru, 21 August 1942

By this time Ichiki had assembled his force on the brush-covered point of land on the east bank of the river, and all was quiet until 0310 on 21 August when a column of some 200 Japanese rushed the exposed sandspit at the river mouth. Most of them were stopped by Marine small-arms fire and by a canister-firing 37-mm antitank gun of the 1st Special Weapons Battalion. But the Marine position was not wired in, and the weight of the rushing attack got a few enemy soldiers into Pollock’s lines where they captured some of his emplacements. The remainder of the line held, however, and fire from these secure positions kept the penetration in check until the battalion reserve could get up to the fight. This reserve, Company G, launched a counterattack that wiped out the Japanese or drove them back across the river.

Ichiki was ready with another blow. Although his force on the east bank had not directly supported this first attack, it now opened up with a barrage of mortar and 70-mm fire, and this was followed by another assault. A second enemy company had circled the river’s mouth by wading beyond the breakers, and when the fire lifted it charged splashing through the surf against the 2nd Battalion’s beach positions a little west of the river mouth.

The Marines opened up with everything they had. Machine-gun fire sliced along the beach as the enemy sloshed ashore, canister from the 37-mm ripped gaping holes in the attack, and 75-mm pack howitzers of the 3rd Battalion, 11th Marines chewed into the enemy. Again the attack broke up, and daylight revealed a sandy battlefield littered with the bodies of the Japanese troops who had launched Guadalcanal’s first important ground action.

Although outnumbered at the actual point of contact, Pollock assessed the situation at daybreak and reported that he could hold. His battalion had fire superiority because of the excellent artillery support and because the course of the river gave part of his line enfilade fire against the enemy concentration in the point of ground funneling into the sandspit. In view of this, General Vandegrift ordered Pollock to hold at the river mouth while the division reserve, the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines enveloped Ichiki. While this battalion prepared for its attack, Company C of the 1st Engineer Battalion went forward to Pollock’s command to help bolster defensive positions. During the morning the engineers built antitank obstacles, laid a mine field across the sandspit, and helped the 2/1 Marines string tactical wire and improve field fortifications. They were under intermittent rifle fire during most of this work.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Colonel Lenard B. Cresswell’s division reserve battalion had reverted to parent control and reported to Colonel Cates to receive the attack plan for the envelopment. Before 0700, Cresswell crossed the Ilu upstream, posted elements of his Company D (weapons) to cover a possible Japanese escape route to the south, and then turned north toward the Ichiki Force. By 0900 his companies crossed their lines of departure in the attack against the Japanese left and rear.

Company C on the right along the coast met one platoon of the enemy near the village at the mouth of the Block Four River, and the Marines moved to encircle this force and isolate it from the remainder of Ichiki’s unit farther west. The other companies moved north with little opposition,

A on the right and B on the left. As the advance continued, the enemy was forced into the point of land on the Ilu’s east bank. By 1400 the enemy was confined completely by the river, the beach, and the envelopment from the left and rear. Some of the Japanese made unsuccessful attempts to escape through the surf and along the beach; another group burst out temporarily to the east but ran head-on into Company C moving up from its battle at the mouth of the Block Four.

The fight continued, with Cresswell tightening his encirclement, and more of the Japanese attempted to strike through to the east. These breakout attempts gave the Guadalcanal fliers, on the island less than 24 hours, a chance to fire their first shots in anger, and the F4F pilots from VMF-223 gave Cresswell’s Marines a hand with strafing attacks that destroyed the Japanese or turned them back into the infantry trap.

To conclude the action by nightfall, Vandegrift ordered a tank attack across the sandspit and into what now had become the rear of the Ichiki Force. The platoon of light tanks struck at 1500, firing at the enemy with canister and machine guns. Two tanks were disabled, one by an antitank mine, but the crews were rescued by the close supporting action of other tanks and the attack rolled on into the Japanese positions. It was over by 1700. Nearly 800 Japanese had been killed and 15 were taken prisoner while only a few escaped into the jungle. Disgraced by the debacle, Colonel Ichiki committed suicide.

The action cost the Marines 34 dead and 75 wounded. A policing of the Japanese battlefield gleaned the division ten heavy and 20 light machine guns, 20 grenade throwers, 700 rifles, 20 pistols, and undetermined number of sabers and grenades, three 70-mm guns, large quantities of explosive charges, and 12 flame throwers. The flame throwers were not used in the action.

Admiral Tanaka later had this to say about the disaster:–

I knew Colonel Ichiki from the Midway operation and was well aware of his magnificent leadership and indomitable fighting spirit. But this episode made it abundantly clear that infantrymen armed with rifles and bayonets had no chance against an enemy equipped with modern heavy arms. This tragedy should have taught us the hopelessness of ‘bamboo-spear’ tactics.19

Battle of the Eastern Solomons

While Colonel Ichiki prepared for his ill-fated attack, Rear Admiral Tanaka and Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, the Eighth Fleet commander, worked to get the colonel’s second echelon ashore for what they hoped would be an orderly, well-coordinated effort against the Marines. These troops were on board the Kinryu Maru and four destroyer transports, and they were escorted by the seaplane carrier Chitose with her 22 floatplanes and by Tanaka’s Destroyer Squadron 2, which Tanaka led in light cruiser Jintsu. A larger naval force operated farther to the east outside the Solomons chain. In all, the Japanese task forces included three aircraft carriers, eight battleships, four heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and 22 destroyers in addition to the five transport vessels.

At this time Admiral Fletcher’s force of two carriers, one battleship, four cruisers, and ten destroyers operated to the southeast of the Lower Solomons conducting

routine searches to the northwest. Fletcher believed the area to be temporarily safe from Japanese naval trespass, and he had sent the carrier Wasp off to refuel. This left him only the Enterprise and the Saratoga for his air support.

On 23 August, two days after the Battle of the Tenaru, American patrol planes first sighted the Japanese transports and the Tanaka escort some 350 miles north of Guadalcanal. marine planes from Henderson Field attempted to attack the troop carriers, but a heavy overcast forced them back to Lunga. The fliers had a better day on the 24th, however. At 1420 the F4F pilots intercepted 15 Japanese bombers being escorted toward Guadalcanal by 12 fighters from the carrier Ryujo. Marines broke this raid up before it got close. They downed six of the Zeros and ten bombers in what was VMF-223’s first big success of the war. Captain Marion Carl splashed two bombers and a Zero, and two planes each were downed by Lieutenants Zennith A. Pond and Kenneth D. Frazier, and Marine Gunner Henry B. Hamilton:–

This was a good day’s work by the fighter pilots of VMF-223. It is necessary to remember that the Japanese Zero at this stage of the war was regarded with some of the awe in which the atomic bomb came to be held later ... The Cactus [Guadalcanal] fighters made a great contribution to the war by exploding the theory that the Zero was invincible; the Marines started the explosion on 24 August.20

Three Marine pilots did not return from the action, and a fourth was shot down but managed to save himself by getting ashore at Tulagi. In plane strength, however, the Cactus Air Force (as the Guadalcanal fliers called their composite outfit) gained. This was the day, as mentioned earlier in this chapter, that the 11 SBDs came in from the damaged Enterprise. At the time the ship was struck, Lieutenant Turner Caldwell, USN, was up with his “Flight 300,” and, low on gas, he led his fliers to Guadalcanal where they more than paid for their keep until 27 September.

Meanwhile Admiral Fletcher’s carrier planes located the enemy task force in the Eastern Solomons at about the same time Japanese planes spotted Fletcher. Like the Battle of Midway, the resulting action was an air-surface and air-air contest. Surface vessels neither sighted nor fired at each other.

The Ryujo, whose Zeros had fared so poorly with John Smith’s F4F pilots, took repeated hits that finally put her out of control and left her hopelessly aflame. One enemy cruiser was damaged; the Chitose sustained severe wounds but managed to limp away; and 90 Japanese planes were shot down. On the American side, 20 planes were lost and the damaged Enterprise lurched away to seek repair.

This action turned back the larger Japanese attack force, and Fletcher likewise withdrew. He expected to return next day and resume the attack, but by then the Japanese had moved out of range. The escorted transports with reinforcements for the late Colonel Ichiki continued to close the range, however, and early on 25 August SBDs form VMSB-232 and the Enterprise Flight 300 went up to find them. The Battle of the Eastern Solomons had postponed Tanaka’s delivery of these reinforcements, but after that carrier battle was over the admiral headed his ships south again late on 24 August.

At 0600 on 25 August, Tanaka’s force was some 150 miles north of Guadalcanal, and there the SBDs from Henderson

Field found him. The Jintsu shook under an exploding bomb that Lieutenant Lawrence Baldinus dropped just forward of her bridge, and Ensign Christian Fink of the Enterprise scored a hit on the transport Kinryu Maru amidships. Admiral Tanaka was knocked unconscious by the explosion on his flagship, and a number of crewmen were killed or injured. The ship did not list under the bow damage, however, and she still was seaworthy. When Tanaka recovered he transferred his flag to the destroyer Kagero and sent the Jintsu to Truk alone.21

Flames broke out on the Kinryu Maru which carried approximately 1,000 troops of the Yokosuka 5th SNLF, and the destroyer Muzuki went alongside to rescue survivors. At just that moment this ship became “one of the first Japanese warships to be hit by a B-17 since the war began”22 when these big planes from the 11th Bombardment Group at Espiritu Santo arrived to lend a hand to the Cactus fliers. The Muzuki sank at once. Another ship then moved in to rescue the survivors from this destroyer while two destroyer transports went to the rescue of the men from the Kinryu Maru. These men were picked up just as the Maru also went to the bottom. Meanwhile another pass at the ships had resulted in light damage to the destroyer Uzuki, and Admiral Tanaka turned back for Rabaul. Many of the SNLF men had been lost, and his force was badly shaken and disordered:–

My worst fear for this operation had come to be realized. Without the main combat unit, the Yokosuka 5th Special Naval Landing Force, it was clear that the remaining auxiliary unit of about 300 men would be of no use even if it did reach Guadalcanal without further mishap.23

Thus had the 1st Marine Division gained some valuable time to prepare for the next Japanese attempt to dislodge its Lunga defense. With air support on Henderson Field and with a tenuous supply route established to the New Hebrides, the division’s grip on Guadalcanal was much improved at month’s end. But it still was a long way from being completely secure, especially now that Ichiki’s act of harakiri had pointed up for the Japanese the impropriety of trying to dislodge the landing force with only 900 or 1,000 men.