Chapter 8: Critical November

If Tokyo by now realized that one of her long tentacles of conquest had been all but permanently pinched off unless the Solomons invaders were at last taken in all seriousness, the critical Guadalcanal situation likewise was getting more active attention in Washington. On 18 October Admiral Ghormley had been relieved of South Pacific Area command by the aggressive Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., and almost immediately the new command was allotted more fighting muscle to back his aggressiveness.1

Ten days after Halsey assumed his new command, the Marine Corps established a supra-echelon staff for coordination of all Fleet Marine Force units in the South Pacific. Major General Clayton B. Vogel headed this newly organized I Marine Amphibious Corps with headquarters at Noumea. He exercised no tactical control over the Guadalcanal operation; his staff was concerned only with administrative matters. And it would not be until later that the amphibious corps would have many troops with which to augment divisions for landing operations.

At a Noumea conference on 23-25 October, General Vandegrift assured Admiral Halsey that Guadalcanal could be held if reinforcements and support were stepped up. Some thought also had to be given to relief of the reinforced 1st Marine Division, weakened by strenuous combat and the unhealthy tropics. Halsey promised Vandegrift all the support he could muster in his area, and the admiral also requested additional help from Nimitz and from Washington.

Shortly after this conference the Marine Commandant, General Holcomb, who had concluded his observations of the Marine units in action on Guadalcanal, south to clear up the command controversy between General Vandegrift and Admiral Turner. Holcomb prepared for Admiral King, the Chief of Naval Operations, a dispatch in which he set forth the principle that the landing force commander should be on the same command level as the naval task force commander and should have unrestricted authority over operations ashore. Holcomb then used his good offices to get Admiral Halsey to sign this dispatch. The Marine Commandant then started back to me States, and at Nimitz’ office in Pearl Harbor he again crossed the path of the dispatch he had prepared for Halsey’s signature. Holcomb assured Nimitz that he concurred with this message, and the admiral endorsed it on its way to King. It was waiting when Holcomb returned to Washington, and King asked the Commandant whether he agreed with this suggestion for clearing up the question of how a landing operation should be commanded. Holcomb said he did agree with it, and this led eventually to the establishment of firm lines of command for future operations in the Pacific. Holcomb had

shepherded Marine Corps thinking on this important matter across the Pacific to its first serious consideration by the top military hierarchy.2

Aside from the general policy that directed America’s major war effort toward Nazi Germany during this period, the South Pacific was not intentionally slighted. But as Rear Admiral Samuel E. Morison points out, Washington at this time had its hands full:–

Our predicament in the Solomons was more than matched by that caused by the German submarines, which, during the month of October, sank 88 ships and 585,510 tons in the Atlantic. The North African venture was already at sea; British forces in Egypt still had to be supplied by the Cape of Good hope and Suez route. Guadalcanal had to be fitted by the Joint Chiefs of Staff into a worldwide strategic panorama, but Guadalcanal could be reinforced only by drawing on forces originally committed to the build-up in the United Kingdom (Operation “Bolero”) for a cross-channel operation in 1943. General Arnold wished to concentrate air forces in Europe for the strategic bombing of Germany; Admiral King and General MacArthur argued against risking disaster in the Solomons and New Guinea in order to provide for the eventuality of a future operation in Europe. President Roosevelt broke the deadlock on 24 October by sending a strong message to each member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, insisting that Guadalcanal must be reinforced, and quickly.3

Immediate results of the Roosevelt order were particularly cheering to Halsey and Vandegrift. Admiral Nimitz ordered the new battleship Indiana and her task group to the South Pacific; the 25th Army Division in the Hawaiian area was alerted for a move south; the repaired USS Enterprise, damaged in the August Battle of the Eastern Solomons, headed back into the fighting. The Ndeni operation, much dog-eared from perpetual shuffling in the pending file, finally was scrapped by Halsey, and the 1st Battalion, 147th Infantry, the latest outfit to start the Ndeni job, was called off its course to the Santa Cruz Islands and diverted to Guadalcanal. Other battalions of the 147th regiment followed.

Also scheduled to reinforce the general Guadalcanal effort were Colonel Richard H. Jeschke’s 8th Marines from American Samoa, two companies (C and E) of Colonel Evans F. Carlson’s 2nd Raider Battalion,4 a detachment of the 5th Defense Battalion, Provisional Battery K (with British 25-pounders) of the Americal Division’s 246th Field Artillery Battalion, 500 Seabees, two batteries of 155-mm guns, additional Army artillery units, and detachments of the 9th Defense Battalion. The old Guadalcanal shoestring from which the operation had dangled for three critical months was being braided into a strong cord.

The two 155-mm gun batteries—one Marine and the other Army5—landed in the Lunga perimeter on 2 November to provide the first effective weapons for answering the Japanese 150-mm howitzers. On 4 and 5 November the 8th Marines landed with its supporting 1st Battalion of the 10th Marines (75-mm pack howitzers), but the other reinforcements commenced a distinctly separate operation on the island. These units included the 1st Battalion of the 147th Infantry, Carlson’s Raiders, the 246th Field Artillery’s Provisional Battery K, and the Seabees. Joined under

the command of Colonel W. B. Tuttle, commander of the 147th Infantry, this force landed on 4 November at Aola Bay about 40 miles east of the Lunga. There, over the objections of Vandegrift and others, Tuttle’s command was to construct a new airfield.6

Geiger’s Cactus Air Force also grew while Vandegrift added to his manpower on the ground. Japanese pounding under the October counteroffensive had all but put the Guadalcanal fliers out of action; on 26 October, after Dugout Sunday, Cactus had only 30 planes capable of getting into the air.7 But in the lull of action following the defeat of General Hyakutake and the withdrawal of the Japanese naval force from the Battle of Santa Cruz, Cactus ground crews had a chance to do some repairs, and more planes began to arrive at Henderson Field.

Lieutenant Colonel William O. Brice brought his MAG-11 to New Caledonia on 30 October, and in the next two days parts of Major Joseph Sailer, Jr.’s. VMSB-132 and Major Paul Fontana’s VMF-211 reported up to Guadalcanal. On 7 November Brigadier General Louis E. Woods assumed command at Cactus, and General Geiger went down to his wing headquarters at Espiritu Santo. By 12 November MAG-11 completed a move to Espiritu Santo where it would be close to Henderson, and more of the units were able to operate from the Solomons field. “In mid-November there were 1,748 men in Guadalcanal’s aviation units, 1,557 of them Marines.”8

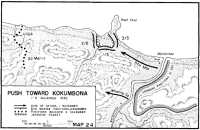

As these fresh troops and fliers came ashore, the veterans of Guadalcanal’s dark early days were off on an expedition to the west. With the Japanese reeling back from their defeat of late October, the Marines sought to dislodge the enemy completely from the Kokumbona-Poha River area some five and a half miles west of the Matanikau. Once cleared from this area, where the island’s north coast bends sharply northwest toward Cape Esperance, the Japanese Pistol Petes would be beyond range of Henderson Field, and the Marines and soldiers could possibly meet Japanese reinforcements from the Tokyo Express before another buildup could muster strength for a new major effort against the perimeter. Under Colonel Edson, the force on this operation included the colonel’s 5th Marines, the 2nd Marines (less 3/2), and a new Whaling Group consisting of the scout-snipers and the 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines. The 11th marines and Army artillery battalions, Cactus fliers, engineers, and bombardment ships were in support. (See Map 24)

The plan: At 0630 on 1 November attack west across the Matanikau on engineer footbridges; move on a 1,500-yard front along the coast behind supporting artillery and naval shelling; assault the Japanese with the 5th Marines in the van, the 2nd Marines in reserve, and with the Whaling Group screening the inland flank. By 31 October preliminary deployment had taken place. The 5th Marines had relieved battalions of the 7th west of the Lunga; the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 2nd Marines

Map 24: Push Toward Kokumbona, 1-4 November 1942

had come across from Tulagi;9 and the engineers were ready with their fuel-drum floats and other bridging material for the crossing sites. Companies A, C, and D of the 1st Engineer Battalion constructed the bridges during the night of 31 October, and by dawn of 1 November, Company E of 2/5 had crossed the river in rubber boats to cover the crossing of the other units on the bridges. The 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 5th Marines reached their assembly areas on the Matanikau’s west bank by 0700 and moved out in the attack with 1/5 on the right along the coast and 2/5 on high ground farther inland. The 3rd Battalion was Edson’s regimental reserve, and battalions of the 2nd Marines followed as force reserve. The area around Point Cruz was shelled by cruisers San Francisco and Helena and destroyer Sterett while P-39s and SBDs from Henderson Field and B-17s from Espiritu Santo strafed and bombed Japanese positions around Kokumbona.

Marines of 2/5 advanced against little opposition along the high ground to reach their first phase line by 1000 and their second phase line by 1440. But near the coast 1/5 met strong resistance, and as it help up to attack Japanese dug in along a deep ravine near the base of Point Cruz, the two 5th Marines battalions lost contact. Farther inland, Whaling screened the flank with no significant enemy contacts. It seemed clear that 1/5 had located the major Japanese force in the area.

While Companies A and C of 1/5 (Major William K. Enright) engaged the enemy, Company B was ordered up to fill

a gap which opened between these attacking companies. The opposition held firm, however, and Company C, hardest hit in the first clash with the entrenched Japanese, had to withdraw. The Company B commander, trying to flank positions which had plagued the withdrawn unit, led a 10-man patrol in an enveloping maneuver which skirted behind Company C, but this patrol also suffered heavy casualties and it, too, was forced to withdraw. Edson then committed his reserve, and Companies I and K of 3/5 (Major Robert. O. Bowen) came up to the base of Point Cruz on a line between 1/5 and the coast. This put a Marine front to the east and south of the Japanese pocket; but the enemy held, and the Marines halted for the night.

Next morning (2 November) Edson’s 2nd Battalion (Major Lewis W. Walt) came to the assistance of the regiment’s other two battalions, and the enemy was thus backed to the beach just west of Point Cruz and engaged on the east, west, and south. The Marines pounded the Japanese with a heavy artillery and mortar preparation, and late in the afternoon launched an attack to compress the enemy pocket. Companies I and K stopped short against an isolated enemy force distinct from the main Japanese position, but this resistance broke up under the campaign’s only authenticated bayonet charge, an assault led by Captain Erskine Wells, Company I commander.

Elsewhere the going also was slow, and advances less spectacular. A Marine attempt to use 75-mm half-tracks failed when rough terrain stopped the vehicles. The 3/5 attack gained approximately 1,500 yards but the main pocket of resistance held, and the regiment halted for another night.

Final reduction of the Japanese stronghold began at 0800 on 3 November. Companies E and G of 2/5 first assaulted to compress the enemy into the northeast corner of the pocket, and this attack was followed by advances of Company F of 2/5 and Companies I and K of 3/5. Japanese resistance ended shortly after noon. At least 300 enemy were killed; 12 antitank 37-mms, a filed piece, and 34 machine guns were captured.

It seemed that this success should at last help pave the way for pushing on to Kokumbona, the constant thorn in the side of Lunga defenders and long a military objective of the perimeter-restricted Marines. From there the enemy would be driven across the Poha River, Henderson Field would be beyond reach of Pistol Pete, and the Japanese would have one less weapon able to bear on their efforts to ground the Cactus fliers. But the frustrating Tokyo Express again quashed Marine ambitions. The Express had shifted its terminal back to the east of the perimeter, and another buildup was taking place around Koli Point.

The 8th Marines was not due in Sealark Channel until the next day (and there was always a chance that Japanese surface action would delay this arrival) so Vandegrift again pulled in his western attack to keep the perimeter strong. Division decided to hold its gain, however, and it left Colonel Arthur’s 2nd Marines (less 3rd Battalion) and the 1st Battalion, 164th Infantry on the defense near Point Cruz while Edson and Whaling led their forces back to Lunga.

Action at Koli Point

With their October counteroffensive completely wrecked, the Japanese faced an

important decision, and on 26 October Captain Toshikazu Ohmae, Chief of Staff of the Southeastern Fleet, came down to Guadalcanal from Rabaul to see what General Hyakutake proposed to do about it. And while Hyakutake had been proud and confident when he reached Guadalcanal on 9 October, Ohmae reflected Rabaul’s current mood which had been much dampened during the month. The counteroffensive had failed, Ohmae believed, because Hyakutake bungled by not carrying out attacks according to schedule and because the Army did not understand problems facing the fleet. “The Navy lost ships, airplanes and pilots while trying to give support to the land assault which was continually delayed,” Ohmae said later in response to interrogations.10

On 9 October Hyakutake’s appetite had been set for Port Moresby; Guadalcanal was but a bothersome bit of foliage to be brushed aside along the way, and the general had the bulk of his 38th Division and other reserves, plus quantities of supplies, in Rabaul and the Shortlands ready to plunge south when the airfield at Lunga was plucked from the Solomons vine like a ripe grape. But now “the situation was becoming very serious,”11 Ohmae was here to point out, and either Guadalcanal or Port Moresby had to be scratched off the conquest list, at least temporarily. In the conference with the naval captain, Hyakutake agreed that the U.S. advance in the Solomons was more serious than the one through New Guinea,12 and he agreed to divert his reserves to a new assault against Vandegrift and the Henderson fliers on the banks of the Lunga.

This time, though, things would be conducted differently. Rather than lurking in wait of successes ashore, the Imperial Fleet would run the show. Ohmae’s chief, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of the Combined Fleet, wanted Hyakutake’s uncommitted troops of the 38th Division13 to land at Koli Point so the Americans would be worried and split by forces on both sides of them. High-speed army vessels would transport these Japanese troops down The Slot under escort of the Tokyo Express. Then Yamamoto’s bombardment ships and Japanese fliers would knock out Henderson Field once and for all, and Hyakutake could land more troops and finish off a battered defensive garrison which would have no air support.

It was a bold plan, but there were some Japanese officers who thought that it was not particularly wise. Admiral Tanaka, that veteran of many distressing hours in The Slot, was one of these. He had suggested after the October defeat that defenses should be pulled back closer to Rabaul so that they would have a better chance to stand off the Allies while Japan gained more strength in the Solomons. “To our regret,” he reported later, “the Supreme Command stuck persistently to reinforcing Guadalcanal and never modified this goal until the time came when the island had to be abandoned.”14

Colonel Shoji already was at Koli Point with his veterans of the October assault against Bloody Ridge, and other Japanese troops now made ready to join him there. Hyakutake planned to build an airfield there so Japanese planes could be more effective during the November attacks. But while Edson and Whaling fought their action to the west around Point Cruz, a Marine battalion marched out to the east and stepped into the middle of Hyakutake’s plans there.

On 1 November, the same day Edson and Whaling crossed their foot bridges westward over the Matanikau, division sent Lieutenant Colonel Herman H. Hanneken’s 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines out to investigate reports of Japanese activities to the east. Hanneken trucked his men to the Tenaru River that day, and on 2 November the battalion made a forced march across the base of Koli Point to the Metapona River, about 13 miles east of the perimeter. Intelligence had it that the Japanese had not yet been able to build up much strength here, and Hanneken’s mission was to keep things that way. On the night of 2 November he deployed his battalion along the coast east of the Metapona and dug in for the night.

While 2/7 Marines strained to see and hear into the black rainy night, six Japanese ships came down Sealark Channel, lay to offshore about a mile east of the American battalion, and began to unload troops. This force was made up of about 1,500 men from the 230th Infantry,15 and they were carrying out initial plans of the Imperial Army and Navy for the buildup to the east.

Rain had put Colonel Hanneken’s radio out of commission, and he could not contact division with information of this landing. The Marines held their positions that night but moved to attack next morning after an eight-man Japanese patrol approached their line by the Metapona. Marines killed four members of this patrol, and the battalion then moved up to fire 81mm mortars into the enemy’s landing site. This brought no immediate response, but as Hanneken’s infantrymen prepared to follow this mortar preparation a large force of Imperial soldiers maneuvered to flank the Marines who began also to draw mortar and artillery fire. In the face of this coordinated attack by the Japanese, 2/7 withdrew, fighting a rear guard action as it pulled back to take up stronger positions on the west bank of the Nalumbiu River, some 5,000 yards west of the Metapona.

During the withdrawal, Hanneken managed to make radio contact with the CP at Lunga. He reported his situation, and called for air attacks against the enemy and for landing craft to meet him at Koli Point and evacuate his wounded. This message reached division at 1445, and Vandegrift immediately dispatched the requested air support and also relayed the situation to gunfire ships which had supported the Koli Point operation.

Cruisers San Francisco and Helena and destroyers Sterett and Landsdowne shelled likely target areas east of the Marine battalion, and planes ranged overhead in vain searches for signs of the enemy. Communications still were none too good, however, and elements of 2/7 were accidentally strafed and bombed by some of the first planes that came out from Cactus.

Meanwhile, division had made the decision to concentrate more force against the evident buildup to he east. The western attack then in progress would be called back while General Rupertus, due to come across Sealark Channel from Tulagi, went to Koli Point with Colonel Sims of the 7th Marines, and Sims’ 1st Battalion (Puller). And to the efforts of this regiments (less its 3rd Battalion), Vandegrift added the 164th Infantry (less 1st Battalion) which would march overland to envelop the Koli Point enemy from the south. Artillery batteries of the 1st Battalion, 10th Marines would be in general support.

By dusk of 3 November the 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines reached the west bank of the Nalimbiu River near the beach at Koli Point, and there General Rupertus met Hanneken next morning with Colonel Sims and Puller’s 1st Battalion, 7th Marines. At 0600 on 4 November Brigadier General Edmund B. Sebree, Americal Division ADC who had just arrived on the island to prepare for the arrival of other Americal troops (which included the 132nd and 182nd Infantry regiments, in addition to the 164th Infantry already in the Solomons actions), marched out of the perimeter in command of the 164th Infantry. Thus General Vandegrift, with two field forces command by general officers, operated his CP like a small corps headquarters.16 And to add even more troops to this concentration of effort to the east, Vandegrift obtained release of Carlson’s 2nd Raider Battalion from Colonel Tuttle’s command at Aola Bay, and ordered it to march overland toward Kili Point and cut off any Japanese who might flee east from the envelopment of the 7th Marines and the 164th Infantry.

On 4 November the Japanese on the east bank of the Nalimbiu did not seriously threaten the Marines on the west, but General Rupertus held defensive positions while awaiting the arrival of the 164th Infantry. The soldiers, weighted down by their heavy packs, weapons, and ammunition, reached their first assembly area on the west bank of the Nalimbiu inland at about noon. There the regimental CP bivouacked for the night with the 3rd Battalion while the 2nd Battalion pushed on some 2,000 yards downstream toward Koli Point.

Next day the 3rd Battalion, 164th crossed the river about 3,500 yards upstream and advanced along the east bank toward the Japanese. The 2nd Battalion likewise crossed the river and followed its sister battalion to cover the right rear of the advance. As the soldiers neared the Japanese force they began to draw scattered small-arms fire, and two platoons of Company G were halted temporarily by automatic weapons fire. This opposition was silenced by U.S. artillery and mortars, however, and when the Army units halted for the night there still was no firm contact with the enemy.

Action on 6 November likewise failed to fix the Japanese in solid opposition, although the 7th Marines crossed the Nalimbiu and moved eastward along the coast, and the 164th Infantry found an abandoned enemy bivouac farther inland. Meanwhile, Company B of the 8th Marines, just ashore on the island, moved east to join the attacking forces as did regimental headquarters and the Antitank and C Companies of the 164th Infantry. The combined force then advanced to positions a mile west of the Metapona River and there dug in for the night, the Marines near the beach to guard against an expected Japanese landing that did not materialize.

Unknown to Marines and Army commanders, the situation was shifting because of new changes in the Japanese plans. During the night of 5-6 November the enemy began to retire eastward from positions facing the Marines across the Nalumbiu, and when the U.S. force stopped west of the Metapona the Japanese were east of the river preparing rear guard defensive positions that would aid a general withdrawal. General Hyakutake and Admiral Yamamoto on 3 or 4 November had changed their plans about hitting the Lunga perimeter from two sides, and the idea of an airfield at Koli Point was abandoned. Shoji was to return overland to Kokumbona where he would join the main elements of the Seventeenth Army’s buildup on the west.17

After remaining in positions to guard against the expected landing throughout 7 November, the U.S. forces under Generals Rupertus and Sebree advanced eastward again on the 8th. Patrols had located the Japanese near the coast just east of Gavaga Creek, a stream some 2,000 yards east of the Metapona River. The 2nd Battalion, 164th Infantry was attached to the 7th Marines as regimental reserve, and the combined forces moved rapidly to surround the Japanese. During the advance General Rupertus retired from the action with an attack of dengue fever, and Vandegrift placed General Sebree in command of the entire operation. The 1st Battalion, 7th Marines met stiff resistance, and four Marines were killed while 31, including Lieutenant Colonel Puller, were wounded. Major John E. Weber next day succeeded to command of this battalion.

Hanneken’s 2/7 moved around the Japanese to take up positions east of the creek with its right flank on the beach. The 2nd Battalion of the 164th Infantry, committed from reserve, tied in on 2/7’s left (inland) flank, straddled Gavaga Creek south of the Japanese, and tied in with the right flank of the 1st Battalion 7th Marines. From this point 1/7 extended north to the beach along the west side of the Japanese positions, and the ring was closed on the enemy. With this action to the east thus stabilized, division called for the return of the 164th Infantry (less 2nd Battalion) and Company B of the 8th Marines. Vandegrift planned to resume the western action toward Kokumbona.

On 9 November the 7th Marines and 2/164 began attacks to reduce the Gavaga Creek pocket. Supported by 155-mm guns, two pack howitzer batteries, and aircraft, the two Marine battalions closed in from east and west while the soldiers of the Army battalion moved north to compress the Japanese into the beach area. The Japanese fought bitterly to break out of the trap, especially to the south through a gap where Companies E (on the right)

and F of the 164th Infantry were unable to make contact across the swampy creek. This action continued through 10 November, with repeated orders by General Sebree for 2/164 to close the gap across the creek. This was not done, however, and the commander of 2/164 was relieved on 10 November.

During the night of 11-12 November most of the enemy escaped along the creek to the south. On 12 November the three battalions swept through the area where the Japanese had been trapped, met little opposition, and withdrew that afternoon across the Metapona River. Marines estimated that the action had cost the enemy approximately 450 dead. About 40 American were killed and 120 wounded.

Meanwhile, Colonel Carlson and his raiders, traveling cross-country to Koli Point, encountered the rear elements of the retiring Japanese. Joined by his Companies B and F, as well as elements of Company D, Carlson concentrated his battalion inland near the native village of Binu and patrolled the surrounding area. During the afternoon of 12 November the raiders beat off five attacks by two Japanese companies. Scattered actions took place for the next five days, and on 17 November the main Japanese force began withdrawing into the inland hills to skirt south of Henderson Field to Kokumbona. Carlson pursued, was augmented by the arrival of his Company A and by native bearers, and remained in the jungle and ridges until 4 December. His combat and reconnaissance patrol covered 150 miles, fought more than a dozen actions and killed nearly 500 enemy soldiers. Raiders lost 16 killed and 18 wounded.

Admiral Tanaka had now been placed in charge of a larger Japanese reinforcement fleet, and Admiral Mikawa of the Eighth Fleet had stepped up his plans for the buildup on the west side of the Marine perimeter. On the night of 7 November Tanaka sent Captain Torajiro Sato and his Destroyer Division 15 down The Slot with an advance unit of some 1,300 troops. After evading a U.S. bomber attack in the afternoon, these ships landed the troops as Tassafaronga shortly after midnight and then sped back north to the safety of the Shortlands. While these ships came north, the second shuttle went south from Rabaul to the Shortlands with the main body of the 38th Division. Two days later (on 10 November) 600 of these troops under Lieutenant General Tadayoshi Sano made the move from the Shortlands to Guadalcanal. The convoy was heckled by U.S. planes and PT boats, but the troops were landed safely, and the ships made it back to the Shortlands on 11 November.18

Brief Renewal of Western Attack

Meanwhile Colonel Arthur’s 2nd Marines (less 3/2), augmented by the 8th Marines and the 164th Infantry (less 2/164), pushed west from Point Cruz toward Kokumbona on 10 November. The force advanced against ragged opposition from infantry weapons and by 11 November had regained most of the ground that had been given up when Vandegrift shifted his attacks to the east earlier in the month.

General Hyakutake, to thwart this thrust at his Guadalcanal command post, assigned Major General Takeo Ito (formerly CO of the 228th Infantry and now infantry group commander of the 38th Division)

to maneuver inland and flank the American advance.

But before Ito could strike—and before the Americans were aware of his threat—General Vandegrift again had to call off the western attack. On 11 November the troops pulled back across the Matanikau, destroyed their bridges, and resumed positions around the Lunga perimeter. Intelligence sources had become aware of the plans of Hyakutake and Yamamoto to mount another strong counteroffensive, and Vandegrift wanted all hands available.

Decision at Sea

It did indeed appear that the Lunga perimeter would need all the strength it could muster. Rabaul was nearly ready for a showdown, winner take all, and the time was now or never. The Japanese were losing their best pilots in this Solomons action, and shipping casualties likewise were beginning to tell. At the same time Allied strength in the South Pacific was slowly growing. It was becoming an awkward battle, and Japan was spending altogether too much time and material on this minor outpost which never had borne much intrinsic value. This needless loss had to be stopped, and Admiral Yamamoto was determined that the new counteroffensive would not be botched.

At 1800 on 12 November Admiral Tanaka’s flagship, the destroyer Hayashio, headed out of the Shortlands leading the convoy which carried the main body of the 38th Division.19 Elsewhere in these Solomon waters two Japanese bombardment forces also made for Guadalcanal. Admiral Yamamoto had ordered them to hammer Henderson Field while Tanaka landed the soldiers. Yet a third Japanese flotilla ranged the Solomons in general support. Nothing was to prevent the 38th Division from landing with its heavy equipment and weapons. The troops would be put ashore between Cape Esperance and Tassafaronga.20

On 23 November the 8th Marines passed through the 164th Infantry to attack the Japanese positions steadily throughout the day. Again there was no gain, and the American force dug in to hold the line confronting the strong Japanese positions. There the action halted for the time with the forces facing each other at close quarters. The 1st Marine Division was due for relief from the Guadalcanal area, and more troops could be allotted for the western action.

On 29 November Admiral King approved the relief of Vandegrift’s division by the 25th Infantry Division then en route from Hawaii to Australia. This division was to be short-stopped at Guadalcanal and the Marines would go to Australia.

During the period that preceded the withdrawal of the 1st Division, the last naval action of the campaign was fought off Tassafaronga. Shortly after midnight on 29 November the Japanese attempted to supply their troops in that area, and an American task force of five cruisers and six destroyers moved to block the attempt.

The American force, under the command of Rear Admiral Carleton H. Wright, surprised the Japanese force of eight destroyers, but the enemy ships loosed a spread of torpedoes before retiring. One Japanese destroyer was sunk,

but the U.S. lost the cruiser Northampton, and three others, the Minneapolis, New Orleans, and Pensacola, were seriously damaged.

But Japan’s day of smooth sailing in the Slot was over. With a reinforced submarine fleet of 24 boats, Admiral Halsey’s command had been prowling the route of the Tokyo Express to destroy or damage several enemy transports. The Japanese edge in fighting ships also was becoming less impressive. In addition to the carrier Enterprise, Halsey had available two battleships, three heavy and one light cruisers, a light antiaircraft cruiser, and 22 destroyers organized in two task forces.

The strength of the Lunga perimeter was likewise much improved since the Japanese attacks of late October. Arrival of fresh troops enabled an extension of defensive positions west to the Matanikau and the establishment of a stronger line along the southern (inland) portions of the infantry ring around Henderson Field. These new positions plus the shooting by the 155-mm guns kept Pistol Pete from carefree hammering at the airfield and beach areas.

And the perimeter was to grow even stronger. More planes were becoming available to Henderson fliers, bombers from the south were able to provide more support for the Solomons area, and another regiment from the Americal Division was ready to move in from New Caledonia. Colonel Daniel W. Hogan’s 182 Infantry (less 3rd Battalion) sailed from Noumea in the afternoon of 8 November on board Admiral Turner’s four transports. Admiral Kinkaid with the Enterprise, two battleships, two cruisers, and eight destroyers would protect the transports, and all available aircraft in the area would cover the troop movement. A day later (9 November) Admiral Scott sailed from Espiritu Santo with a supply run for Guadalcanal, and a day after that Admiral Callaghan followed with his five cruisers and ten destroyers.

Early on 11 November (the day Vandegrift called off his western advance) Scott’s transports arrived off Lunga Road to begin unloading. Enemy bombers twice interrupted the operations, and damaged the Betelgeuse, Libra, and Zeilin. Damage to the latter ship was serious, and she was mothered back to Espiritu Santo by a destroyer. The other two transports retired at 1800 to Indispensable Strait between Guadalcanal and Malaita, and later joined Turner’s transports. During the night Admiral Callaghan patrolled the waters of Sealark Channel.

Turner’s transports with the 182nd Infantry arrived at dawn on 12 November to begin unloading troops and cargo. During the morning the Betelgeuse and Libra drew fire from near Kokumbona. The two ships escaped damage, however, and American counterbattery and naval gunfire silenced the Japanese. Unloading ceased in the afternoon, and the ships were flushed into dispersion by an attack of about 31 torpedo bombers. The transports escaped unscathed, but Callaghan’s flagship San Francisco and the destroyer Buchanan were damaged. Only one Japanese bomber survived the American antiaircraft fire and air action, and unloading resumed two hours later.

Meanwhile, intelligence reports plotted the Japanese fleet closing in on the Guadalcanal area. During the morning American patrol planes north of Malaita had spotted a Japanese force of two battleships, one cruiser, and six destroyers. Later five destroyers were observed 200

miles north-northwest. By midafternoon another sighting placed two carriers and a brace of destroyers some 250 miles to the west.21 Coastwatchers in the upper Solomons logged other sightings. Turner appraised the various reports at two battleships, two to four heavy cruisers, and ten to twelve destroyers. Callaghan was heavily outweighed. But Halsey’s orders were to get the naval support of Guadalcanal out of the dark back alleys of the South Pacific; and after he shepherded the unloaded transports south to open water, Callaghan turned back to engage the enemy.

Japanese battleships Hiei and Kirishima, light cruiser Nagara, and 15 destroyers steamed south to deliver Admiral Yamamoto’s first blow of the new counteroffensive. This bombardment group was to enter Sealark Channel and hammer Henderson Field and the fighter strip to uselessness so that Cactus air could not bother General Hyakutake’s reinforcements en route. This Japanese mission gave Callaghan one slight advantage. For shore bombardment, the Imperial battleships carried high explosive projectiles for their 14-inch guns, not armor-piercing shells which would have been much more effective against the hulls of U.S. cruisers.

Near Savo Island at 0124 on 13 November, cruiser Helena raised the Japanese in radar blips at a range of 27,000 yards, and she warned the flagship that the enemy was approaching between Savo and Cape Esperance. But radar on the San Francisco was inadequate, and Callaghan could not determine the exact positions of his own or the enemy ships. The admiral therefore delayed action until he was sure of the situation. By that time the range had closed to about 2,500 yards, and the van destroyer of the American force was nearly within the Japanese formation. When they maneuvered to launch torpedoes, the American ships disorganized their formation, and they took up independent firing. Some swerved off course to avoid collision, and in the melee both American and Japanese ships fired at their sister craft.

The San Francisco caught 15 solid hits from big Japanese guns and was forced to withdraw with Admiral Callaghan killed and others, including Captain Cassin Young, her skipper, dead or fatally wounded. A cruiser hit on the Atlanta killed Admiral Scott and set fire to the ship. But the small American force held in spite of heavy losses, and by 0300 the Japanese group retired without being able to attempt its bombardment mission. The Imperial bombardment force had lost two destroyers and four others were damaged by more than 80 American hits.

For the American ships it was a costly victory. Henderson Field had been protected, but the antiaircraft cruisers Atlanta and Juneau sank in the channel along with destroyers Barton, Cushing, Monssen, and Laffey. In addition to Callaghan’s flagship, heavy cruiser Portland also was seriously damaged as were destroyers Sterett and Aaron Ward. Destroyer O’Bannon sustained minor concussion to her sound gear. These ships struggled back to the New Hebrides after daybreak on 13 November. Of the 13 American ships in the action only destroyer Fletcher escaped damage.

Planes from Henderson Field took off at first light on 13 November to nip the

heels of the retiring Japanese ships. They found the crippled battleships Hiei afire near Savo, and bombed and strafed her throughout the day. The Japanese fought a losing battle to salvage their hapless ships, but they had to scuttle her next day (14 November).

During the night battle off Guadalcanal, Admiral Tanaka had been ordered to lead his convoy back to the Shortlands. He headed south again from there during the afternoon of 13 November at about the same time that Admiral Halsey ordered Kinkaid to withdraw the carrier Enterprise south with the remnants of Callaghan’s force. Halsey wanted this carrier—the South Pacific’s sole operational flattop—safely out of Japanese aircraft range. To guard Henderson Field, Admiral Lee would steam on north with his battleships Washington and South Dakota and four destroyers from Kinkaid’s task force. The distance was too great for Lee to make that night, however, and only the Tulagi PT boats were available to protect Sealark Channel. Shortly after midnight Japanese cruisers and destroyers entered the channel and shelled the Cactus airfield for about half an hour. There was no serious damage, however. At dawn on 14 November the Henderson fliers found their field still operational.

Early search flights found Admiral Tanaka’s convoy heading down The Slot some 150 miles away and the bombardment cruisers and destroyers retiring north. In spite of the fact that the shelling of Henderson Field had been ineffective, Tanaka was coming on down to Guadalcanal with the 10,000 troops of the 38th Division’s 229th and 230th Regiments, artillery personnel, engineers, other replacements, and some 10,000 tons of supplies.

First Cactus attacks struck the retiring warships which had shelled Henderson during the night. Ground crews on the field hand-loaded their planes and visiting craft from the Enterprise with fuel and ordnance, and the planes mounted from the muddy runways in attack. They damaged Japanese heavy cruiser Kinugasa and the light Isuzu. Planes still on the Enterprise, now 200 miles southeast of Guadalcanal, also attacked the Japanese warships, They added to the troubles of the Kinugasa and Isuzu, and also damaged heavy cruisers Chokai and Maya and destroyer Michishio.

Meanwhile, the 11 troop transports steamed on down The Slot until by about 1130 they were north of the Russells and near Savo. A previous light attack by Enterprise fliers had inflicted little damage to this convoy, but at 1150 seven torpedo bombers and 18 dove bombers from Henderson were refueled, rearmed, and boring in for an attack. This strike hulled several of the transports. About an hour later 17 fighter-escorted dive bombers delivered the second concentrated American attack on the transports and sank one of them. Next turn went to 15 B-17s that had left Espiritu Santo at 1018. They struck at 1430 from an altitude of 16,000 feet and scored one hit and several near misses with their 15 tons of explosives.

These attacks continued all day as the Henderson fliers scurried back and forth from their field. Nine transports were hit, and seven of them sunk. But from these sinking ships, some 5.000 men were rescued by destroyers. As Admiral Tanaka described the day:–

The toll of my force was extremely heavy. Steaming at high speed the destroyers had laid smoke screens almost continuously and delivered

a tremendous volume of antiaircraft fire. Crews were near exhaustion. The remaining transports had spent most of the day in evasive action, zigzagging at high speed, and were now scattered in all directions.

In detail the picture is now vague, but the general effect is indelible in my mind of bombs wobbling down from high-flying B-17s, of carrier bombers roaring toward targets as though to plunge full into the water, releasing bombs and pulling out barely in time; each miss sending up towering columns of mist and spray; every hit raising clouds of smoke and fire as transports burst into flame and take the sickening list that spells their doom. Attacks depart, smoke screens lift and reveal the tragic scene of men jumping overboard from burning, sinking ships. Ships regrouped each time the enemy withdrew, but precious time was wasted and the advance delayed.22

In spite of this disastrous day, Tanaka steamed on south in his flagship, doggedly leading transports Kinugawa Maru, Yamatsuki Maru, Hirokawa Maru, and Yamaura Maru on toward Guadalcanal. These ships and three destroyers from Destroyer Division 15 which continued to escort him were the only sound vessels Tanaka had at sundown that day—“... a sorry remnant of the force that had sortied from Shortland.”23 But what was worse, Tanaka then got the word that a strong U.S. task force appeared to be waiting for him at Guadalcanal, but Japanese intelligence reported these ships to Tanaka as four cruisers and four destroyers. To counter this threat, headquarters at Rabaul ordered Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo to hurry down and run interference for Tanaka with a fighting force which included the battleships Kirishima, heavy cruisers Atoga and Takao, light cruisers Sendai and Nagara, and an entire destroyer squadron. Kondo was to complete the Henderson Field knockout which Admiral Callaghan’s force had thwarted two nights earlier.

Throughout the day Admiral Lee likewise sifted intelligence reports which funneled into his flagship, the battleship Washington. Then he moved against this powerful Tokyo Express which was headed his way.*

Lee entered Sealark Channel at about 2100 on 14 November and patrolled the waters around Savo. An hour before midnight, radar indicated a Japanese ship (the cruiser Sendai) nine miles to the north. About 12 minutes later the target was visible by main battery director telescopes and Lee ordered captains of the Washington and the South Dakota to fire when ready. Their first salvos prompted the Sendai to turn out of range.

Shortly before this Admiral Tanaka, still leading his four transports south toward Guadalcanal, had been much relieved to see Admiral Kondo’s Second Fleet in front of him in The Slot. But when the cruiser Sendai scurried back from this first brief brush with the American ships, the Japanese officers found that for the first time in the Pacific war they were up against U.S. battleships, and not just cruisers as they had expected.

Tanaka immediately ordered his three escorting destroyers—the Destroyer Division 15 ships commanded by Captain

[Footnote number 23 was used twice in the original printed document. The first one remains as footnote 23. The second one has been included here as an inline footnote]

* (23) The American admiral also moved against some powerful naval thinking. Many officers at ComSoPac headquarters “doubted the wisdom of committing two new 16-inch battleships to waters so restricted as those around Savo Island, but Admiral Halsey felt he must throw in everything at this crisis. And he granted Lee complete freedom of action upon reaching Guadalcanal.” Struggle for Guadalcanal, 272.

Torajiro Sato—into the fight, and the admiral then turned his transports north and shepherded them beyond range of the impending action. Meanwhile Admiral Kondo’s fleet closed for the fight, and soon the American destroyers leading Admiral Lee’s formation came within visual range of some of these ships. The U.S. destroyers got the worst of the bargain. By 2330 all four of them were out of action: the Walke afire and sinking, the Benham limping away, the Preston gutted by fire that caused her abandonment later, and the Gwin damaged by a shell in her engine room. Only one Japanese destroyer, the Ayarami, had been damaged.

The two U.S. battleships continued northwest between Savo and Cape Esperance. The South Dakota, turning to avoid the burning destroyer Preston, came within range of the Japanese ships which had just scuffled with the American destroyers, and the word passed by these Japanese ships brought their “big brothers” out from the shelter of Savo’s northwest coast.

Admiral Kondo steamed into the fight with destroyers Asagumo and Teruzuki in the van followed by heavy cruisers Atago and Takao, and the battleship Kirishima in the wake.

The South Dakota, partially blind because of a power failure that hampered her radar, soon came within 5,000 yards of the Japanese who illuminated her with their searchlights and opened fire. Almost at once the Washington blasted her 16-inch main batteries at the enemy battleship about 8,000 yards away.

The Kirishima took nine 16-inch hits and nearly half a hundred 5-inch wounds in less than ten minutes, and she staggered away in flames. Japanese cruisers Agate and Takao, revealed by their own searchlights, also were damaged. But the original Japanese onslaught had caused enough serious damage to the South Dakota to force her to retire, also.

Admiral Lee continued on a northwesterly course to divert the Japanese, then bore away to me southwest near the Russells, and finally retired from the area when he noted the Japanese likewise withdrawing. The enemy battleship Kirishima was abandoned as was the destroyer Ayanami. American destroyer Benham likewise had to be abandoned later.

With his escorting destroyers dispersed by this battle and its aftermath, Admiral Tanaka now was alone in his flagship Hayashio with the four transports. He made full speed for Tassafaronga, but it was clear to him that the transports would not be able to unload before daylight. After that the U.S. planes would attack them like they had those six transports which tried to unload during daylight in October. But these men were critically needed on Guadalcanal, Tanaka knew. He sent a message to Admiral Mikawa at Eighth Fleet headquarters and asked if he could run the transports aground on the beach to insure prompt unloading. Admiral Mikawa said “No.” But Admiral Kondo, disengaging his Second Fleet from the battle with Lee’s battleships, contacted Tanaka and told him to go ahead with this plan.

By now the early light of dawn was turning Sealark Channel a slick gray, and Tanaka followed Admiral Kondo’s message of approval. He ordered the four transports to run aground off the landing beaches, and after he watched them head for shore the admiral turned

north, gathered up his destroyers again and sailed through the waters east of Savo Island.24

The admiral wrote later:–

Daylight brought the expected aerial assaults on our grounded transports which were soon in flames from direct bomb hits. I later learned that all troops, light arms, ammunition, and part of the provisions were landed successfully.25

Two guns of the 244th Coast Artillery Battalion and the 5-inch guns of the 3rd Defense Battalion also contributed to the damage of the grounded transports. This fire hit two of the ships, and then the American destroyer Meade came over from Tulagi to enter the fight. Planes from Henderson Field and Espiritu Santo soon joined this grisly “Buzzard Patrol,” and the Japanese transports were reduced to useless hulks engulfed in flames. Japanese plans for a big November counteroffensive had met disaster, and Imperial headquarters now began to think seriously about the more cautious plan to pull the line back closer to Rabaul. There now were some 10,000 new Japanese troops on Guadalcanal, but these recent sea and air actions made it clear to he Japanese that these troops could not be supplied or reinforced on a regular basis. The shipping score against the Japanese scratched two battleships, a cruiser, three destroyers, and 11 transports. Nine other ships had been damaged.

American losses numbered one light cruiser, two light antiaircraft cruisers, and seven destroyers. Seven other U.S. ships were damaged. But the Tokyo Express had been derailed. Never again was Japan able to reinforce significantly with night runs from Rabaul. From this point the Imperial force on the island began to dwindle26 while the American command continued to grow. Critical November had turned into decisive November, in the Pacific War as well as the Guadalcanal Battle. The Japanese never again advanced and the Allies never stopped.

Admiral Tanaka, whose skillful conduct of the convoy and aggressiveness in throwing his four escorting destroyers into the battle against Admiral Lee’s force near Savo had contributed most to what limited success the Japanese had had during this harrowing month, summed it up this way:–

The last large-scale effort to reinforce Guadalcanal had ended. My concern and trepidation about the entire venture had been proven well founded. As convoy commander I felt a heavy responsibility.27

Back Toward Kokumbona

With this Japanese attempt to reinforce General Hyakutake decisively stopped, the American ground advance to the west was resumed. General Sebree, western sector commander, would be in command. With the troops of his sector—the 164th Infantry, the 8th Marines, and two battalions of the 182nd Infantry—the general planned to secure a line of departure extending from Point Cruz inland for about 1,700 yards. From this line the attack would press on to Kokumbona and the Poha River where the main Japanese force was concentrated.

The 2nd Battalion of the 182 Infantry crossed the Matanikau on 18 November and took up positions on the south (inland) flank of the proposed line of departure. On the following day the 1st Battalion of the same regiment moved west to take up the right flank position at the base of Point Cruz. Company B of the 8th Marines screened the left flank of 1/182’s advance, and these two units met sporadic infantry opposition. About noon the Army battalion halted, dug in, and refused its inland flank. The screening Marine company withdrew to rejoin its regiment east of the Matanikau. A gap of more than 1,000 yards separated the two battalions of the 182 Infantry.

Meanwhile, the Japanese deployed for a local offensive action of their own. With the 38th Division troops who had been on the island, plus those few brought ashore from the ill-fated transports, the Japanese moved east to force a Matanikau bridgehead from which a new attack at the Lunga perimeter could be launched. Other elements of the 38th Division moved inland to occupy the Mount Austen area. Remnants of the battered 2nd Division were held in Kokumbona.

On the night of 19-20 November, the Japanese took up positions facing the two Army battalions west of the river and engaged the Americans with artillery and mortar fire. At dawn (20 November) the Japanese struck the inland flank of 1/182. The Army troops gave ground for approximately 400 yards, but this was regained later in the morning with air and artillery support. This U.S. attack continued to the beach just west of Point Cruz, but halted there in the face of increased enemy artillery and mortar fire.

During the night the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 164th Infantry moved into the gap between the two battalions of the 182nd, and a general American attack jumped off on the morning on 21 November. Strong Japanese positions fronting the 164th held the attempt to no gain, however, and a second attack on the morning of 22 November likewise was halted.