Chapter 7: Talasea and Beyond

Recall to Rabaul1

The Japanese commanders at Rabaul, General Imamura of Eighth Area Army and Admiral Kusaka of Southeast Area Fleet, were in an unenviable situation following the loss of Cape Gloucester. They knew that the defensive line toward which the Matsuda Force was retreating was untenable. The 17th Division troops could, and would, undoubtedly, fight doggedly to hold the Allies at bay before Talasea and Cape Hoskins in the north and Gasmata in the south. The enemy’s dwindling force of warships and transports could attempt sacrifice runs to keep supplies flowing to the soldiers, and the naval planes of the Eleventh Air Fleet could provide weak and sporadic support of the ground action. Not even these few ships and aircraft were to be available, however. The success of the American amphibious assault on Kwajalein prompted the retirement of the Combined Fleet from its suddenly vulnerable base at Truk, and the follow-up carrier strike of 16-17 February on Truk decided Admiral Koga to issue recall orders to all Japanese naval aircraft in the Southeast Area.2

Enemy interceptors made their last attempt to break up an Allied air attack on Rabaul on 19 February. On the 20th, the fields that ringed Blanche Bay were deserted, “not a single moveable plane remaining”3 to contest control of the air. The harbor yawned empty too, with the hulks of sunken ships the only reminder of the bustling fleet that had once based there. The Japanese stronghold was forced to rely entirely on its ground garrison for defense. Imamura and Kusaka determined to make that defending force as strong as possible, adding to it every available soldier and sailor on New Britain.

On 23 February, orders to withdraw to Rabaul were received at 17th Division headquarters at Malalia. General Sakai gladly dropped the plans he had been formulating for holding out against the oncoming Allied troops, for he fully appreciated how isolated and hopeless his fight would have been. In the stead of preparations for a last-ditch defense centered on positions at Cape Hoskins, Sakai began hastily figuring the moves that would get his command back to Rabaul in fighting shape. The Matsuda Force was his major problem. The lead section of the weary column of men staggering along towards Talasea was still two weeks’ march from the Willaumez Peninsula.

Unless the Allies suddenly broke their pattern of pursuit and surged ahead of the retreating Japanese troops, Sakai could

figure that most of the men en route would reach their objective. Supply dumps located along the withdrawal routes held enough rations to enable the strongest and best-led elements of the Matsuda Force to make good their escape. The sick and wounded who fell behind, who lacked the strength to keep up with the main body or even to fend for themselves, were doomed. The kindest fate that might befall them was capture by a Marine patrol. Often the near-naked, emaciated wretches whom the Americans found glassy-eyed and dazed along the trails had not the strength left to survive the trip to the coast. So tangled and rugged was the country through which the enemy columns struggled that scores of stragglers who died a few feet off the track where they had crawled to rest would have lain unnoted but for the unforgettable stench of human remains rotting in the jungle.

The route taken by the defeated Japanese troops after they passed through Iboki headed sharply inland, following the course of the Aria River for 12-14 miles and passing through the native villages of Taliwaga and Upmadung on the west bank and Bulawatni and Augitni on the east. From Augitni, where the trail used by the Komori Force to escape Arawe joined, the track headed northeast across mountain slopes and through extensive swamps fed by sluggish, wide, and deep rivers. Hitting the coast at Linga Linga Plantation, a straight-line distance of 35 miles from Iboki, the route crossed the formidable obstacle posed by the Kapaluk River and paralleled the shore to Kandoka at the neck of Willaumez Peninsula. Continuing along the peninsula coast to Garu, the trail then crossed a mountain saddle to the eastern shore at Kilu and turned south to Numundo Plantation. An alternative route from Kandoka to Numundo across the base of the peninsula lay through a 15-mile-wide morass that bulged along the course of the Kulu River. Once the Japanese reached Numundo Plantation, they could follow the coastline trail to the airdrome at Cape Hoskins, to Malalia just beyond, and eventually, with luck, to Rabaul.

The task of keeping the escape route open until the Matsuda Force had reached the comparative safety of Malalia was given to two units. The 51st Reconnaissance Regiment performed the duties of rear guard, insuring the enemy withdrawal from contact, and the Terunuma Force, a composite battalion of the 54th Infantry, held the Talasea area, with orders to defend it against Allied attacks. The delaying actions of Colonel Sato’s reconnaissance unit in western New Britain gave General Matsuda the respite he needed to get his command underway to the east. If the Terunuma Force carried out its mission equally well, it would hold its positions long enough for the hundreds of survivors of the Cape Gloucester battle to reach the area east of the Willaumez Peninsula. The Japanese commanders considered that they had enough troops in the Cape Hoskins sector to require the Allies to mount a large-scale amphibious operation to take it. And barring such an effort, the 17th Division was confident that it could pull back to Rabaul with many of its units still in fighting trim. General Sakai estimated that most of his combat troops would reach the stronghold by mid-April and all of the remaining cohesive outfits, including rear-guard detachments, would make it by the middle of May.

Not all the Japanese movement had to be accomplished on foot; there were enough barges available to move a good part of the heavy munitions at Gasmata and Cape Hoskins back to Rabaul. Sick and wounded men, who could not survive a land journey, were given priority in these craft. Some combat units were transported a portion of the way to their goal in overwater jumps from Malalia to Ulamona and then on to Toriu. The first village was a major barge base about 65 miles from Cape Hoskins, and the second, 30 miles farther east, was the terminus of a trail network which led to Rabaul through the mountains of Gazelle Peninsula. The 17th Division planned that its components would move lightly armed, carrying little reserve ammunition and only a bare subsistence level of rations. If the Allies attempted to cut the retreat route, all available units would concentrate to wipe out the landing force.

Only a few Japanese craft were risked in the dangerous waters west of Willaumez Peninsula, and these were used, on 21 February, to carry 2nd Battalion, 53rd Infantry remnants to Volupai, opposite Talasea on Willaumez. The battalion, with reinforcing artillery, was sent on ahead of the main body of the Matsuda Force to form the nucleus of a covering force at Ulamona. The barges returned once more to the Aria River before the Marines landed at Iboki and took out General Matsuda, members of his immediate staff, and all the litter patients they could carry. Matsuda was landed at Malalia on the 25th.

Carrying out his orders, Colonel Sato of the 51st Reconnaissance Regiment saw the last march element of the Matsuda Force safely through Upmadung before starting his own unit on the trail. At Augitni, Sato met Major Komori who had brought his troops up from Arawe, and the two groups, both under Sato’s command, began moving east on 6 March. On the same date, the leading elements of the Matsuda Force column reached the base of Willaumez Peninsula.

Volupai Landing4

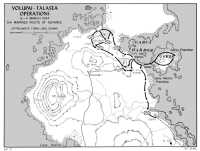

The 6th of March was the landing date chosen for the APPEASE Operation—the assault and seizure of the Talasea area of Willaumez Peninsula by the 5th Marines, reinforced. The principal objective included several parts, the government station on the shore of Garua Harbor that gave its title to the whole region, an emergency landing ground nearby, grandly called Talasea Airdrome, and the harbor itself which took its name from Garua Island that formed one of its arms. The landing beach, RED Beach, lay directly across the peninsula from Garua Harbor in the curve of a shallow bay at Volupai. The isthmus connecting the two points, 2½ miles apart, is the narrowest part of the peninsula. (See Map 30.)

Several plantations, one on Garua Island and the others at Volupai on the west coast and Santa Monica, Walindi, and Numundo

on the eastern shore, had the only easily traveled ground on Willaumez. The terrain of the rest of the peninsula followed the general pattern of New Britain, mountains and high ground inland covered by rain forest, with foothills and coastal flats choked with swamp forest, secondary growth, and sprawling swamps along the course of the many rain-swollen rivers and streams. Above the isthmus between Volupai and Garua Harbor, the peninsula was little used by the natives or the Japanese because of impassable terrain. Below the narrow neck of land, much of it occupied by Volupai Plantation, there were a number of native villages along the coast and on mountain tablelands. A cluster of four called the Waru villages, about 1,500 yards west of Talasea, and Bitokara village, the same distance northwest of the government station, figured as intermediate objectives in 5th Marines’ operation plans.

RED Beach was a 350-yard-wide corridor opening to Volupai Plantation, 400 yards inland; on its northern flank the beach was bordered by a swamp, to the south a cliff loomed over the sand. The cliff was part of the northwest slopes of Little Mt. Worri, a 1,360-foot peak that was overshadowed by 300 feet by its neighbor to the south, Big Mt. Worri. The eastern extension of Big Mt. Worri’s ridgeline included Mt. Schleuther (1,130 feet) which dominated Bitokara, Talasea, and the Waru Villages. The trail from Volupai to Bitokara, which was to be the 5th Marines’ axis of advance, skirted the base of these heights.

The major obstacle to the proposed landing at Volupai was the reef that extended 3,000 yards out from shore. Obviously impractical as the route for assault waves was the tortuous small-boat passage which wound through the coral formations. To make this narrow waterway safe for supply craft and support troops, the first Marines on RED Beach would have to land from LVTs which could ignore the reef and churn straight on to the beach from the line of departure. The 1st Marine Division would provide the tractors, the Seventh Fleet their transport and escort to the target, and the Army amphibian engineers all the rest of the landing craft needed. An Army officer, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Amory, Jr., would command all shipping during the movement to the objective and the landing.

The understrength company of LCVPs and LCMs that had supported BACKHANDER Force since D-Day could handle some portion of the load in the coming operation, but more engineer boats were needed. As early as 4 February, ALAMO Force alerted the Boat Battalion of the 533rd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment to a probable role in the coming operation. The 533rd, a unit of the 3rd Engineer Special Brigade, was newly arrived in the forward area and as yet untested in combat. Elements of the boat battalion headquarters, a boat company, a shore company, and a maintenance detachment, all under command of Lieutenant Colonel Amory, were detailed to the job. From Goodenough Island, the engineers and their equipment moved to Finschhafen, and, on 27 February, the advance echelon embarked in its own boats for the 85-mile run to Borgen Bay.

The soldier boatmen made their landfall late at night after a day-long passage through choppy seas, but they got no chance to explore the bivouac area, “in the least atrocious of the various swamps

Map 30: Volupai–Talasea Operations, 6-11 March 1944, 5th Marines Route of Advance

available,”5 which had been tentatively set aside for them. “Instead,” the unit’s history relates, “one of the worst ‘rat races’ of all times was to occupy every minute of every 24 hours for the next week.”6 This period of furious but ordered activity saw the movement of the 5th Marines and all its reinforcing units to Iboki, together with 20-days’ supplies for the nearly 5,000 men of the APPEASE task force. Concurrently, the few dozen landing craft available had to be used to transport the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines to Iboki, where it could take over patrol missions from the 5th and be available as a reserve if the APPEASE operation demanded.

While the landing force assembled at its staging point, scouts tried several times to land on Willaumez Peninsula to determine the location and strength of enemy defending forces. Moving at night in torpedo boats, the men were turned back by high seas on one occasion and on another by a sighting of troops moving in the proposed landing area. Finally, early on 3 March, Australian Flight Lieutenant G. H. Rodney Marsland, who had managed Santa Monica plantation before the war, the 1st Division’s chief scout, Lieutenant Bradbeer, and two natives landed near Bagum village about nine miles from Volupai. Setting up in the village, the party sent runners out to contact key natives known to Marsland and discover the Japanese dispositions. After nearly 24 hours ashore, the scouts withdrew with some useful information on the location and size of various enemy detachments, but they had surprisingly received no report of the major enemy concentration in the immediate Talasea area.7

Defending Willaumez Peninsula was a garrison of 595 men, some 430 of them concentrated in the vicinity of Talasea. A Japanese muster roll, completed at the same time the BACKHANDER scouts were ashore, agreed very closely with the information that was reported to the 5th Marines at Iboki. Volupai had only a rifle platoon and a machine gun squad to defend the beach, 28 men in all, but the bulk of the enemy force was within easy reinforcing distance. The Japanese, all under Captain Kiyomatsu Terunuma, commander of the 1st Battalion, 54th Infantry, consisted of most of that unit,8 plus the 7th Company of the 2nd Battalion, 54th, the 9th Battery, 23rd Field Artillery, a platoon of machine guns, and a platoon of 90-mm mortars. Terunuma’s orders were to hold his positions north of Kilu and the Walindi Plantation and not to retreat without permission of the 17th Division commander.

The 5th Marines had no indication that RED Beach was heavily defended; the natives reported that the area was not fortified, and aerial reconnaissance appeared to confirm this intelligence. Support for the APPEASE landing was therefore not overwhelming, but it was adequate for the job at hand. For three days prior to D-Day, Australian Beaufort squadrons based at Kiriwina Island flew bombing and strafing missions against targets in the Talasea and Cape Hoskins vicinity, and, on D-Day, the RAAF planes were to provide cover for the attack flotilla and to

blast RED Beach ahead of the assault waves. To make up for the absence of naval gunfire support, the 1st Division came up with its own brand of gunboats—medium tanks in LCMs. Four Shermans were added to the platoon of light tanks attached to the 5th Marines to provide the necessary firepower. Tests of the novel means of shelling the beach were made at Iboki to make sure that the tanks could fire from their seagoing gun platforms. The accuracy of the practice firing with 75-mm cannon was nothing to boast about,9 but the makeshift gunboats proved to be practical.

The operation plan of the 5th Marines called for the 1st Battalion, embarked in LVTs, to land in assault and secure a beachhead line which passed through the edge of Volupai plantation. The 2nd Battalion, following directly behind in LCMs and LCVPs, was to pass through the 1st’s positions and attack up the trail to Bitokara to seize the Talasea area. Two batteries of 75-mm pack howitzers of 2/11 were to follow the assault battalions ashore on 6 March to furnish artillery support for the attack across the peninsula. On D plus 1, the 5th’s 3rd Battalion and reserve elements of the regiment’s reinforcing units would move to RED Beach in landing craft which had returned from Willaumez.

Shortly before the APPEASE operation got underway, the 5th Marines got a new commander, Colonel Oliver P. Smith, who had just reported to the division. Colonel Selden stepped up to division chief of staff, replacing Smith who held the position briefly following his arrival on New Britain. A number of experienced senior officers, including Colonel Amor L. Sims, who had been chief of staff, and Colonel Pollock, the D-3, had returned to the States in February to fill key assignments in the continuing buildup of the Marine Corps for the Pacific War. Two of the 5th’s battalions also had comparatively new commanders. Major Gordon D. Gayle, who led 2/5, had taken over when Lieutenant Colonel Walt was promoted to regimental executive officer; Lieutenant Colonel Harold O. Deakin, who had the 3rd Battalion, assumed command after the battle for Aogiri Ridge was successfully concluded.

The invasion convoy that assembled off Iboki on 5 March for the 57-mile-long run to Volupai included 38 LCMs, 17 LCVPs, 5 LCTs, and 5 MTBs. Each of the Navy’s LCTs carried five tractors of Company B, 1st Amphibian Tractor Battalion, and the Marines of 1/5 who would ride them. The torpedo boats were under orders to escort the LCTs, as naval officers were dubious about risking their valuable landing craft in poorly charted waters without adequate communications or proper navigational guides. If anything, the engineer coxswains of Amory’s command had more to worry about than the sailors, for their boats were a good bit more thin-skinned than the LCTs, and they would be moving at night through strange waters abounding in coral outcroppings.

Men of the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 5th Marines and the regiment’s various reinforcing elements began loading their boats at 1300, and, at 2200, the convoy departed, carrying more than 3,000 men and 1,000 tons of equipment. Lieutenant Colonel Amory later categorized his motley convoy as “probably the war’s outstanding

example of overloading small boats,”10 but the movement to the target came off without a major hitch despite heavy rain squalls that struck shortly after midnight and continued for two hours.

There was one mishap en route with potentially serious consequences, but the lack of determined opposition at RED Beach negated its effect. The boat carrying the Army air liaison party attached to the landing force broke down early in the movement, and Major Gayle’s boat, which was proceeding independently after a late start, took the crippled craft in tow. Gayle was reluctant to delay his own progress, but considered the liaison group’s radios to be of vital importance in contacting supporting air units. As a result of his prudent action, the 2/5 commander arrived off Volupai after his battalion had begun landing, but its executive officer, Major Charles R. Baker, was fully in control.

The convoy of small craft arrived at its appointed place about 3½ miles off the coast at Volupai as dawn was breaking on D-Day. The LCTs closed slowly toward the reef as the Marines looked anxiously skyward for the planes which were supposed to be flashing in to hit the possible enemy positions at RED Beach. None of the RAAF Beauforts appeared, as their fields on Kiriwina were weathered in,11 and the troops became more and more conscious of their exposure to an unknown enemy waiting on the silent shore. Lieutenant Colonel Amory, from his LCVP at the head of the line of landing craft, radioed Colonel Smith, “Shall we proceed despite air failure,” and the landing force commander replied immediately, “Carry on.”12

At 0825, on Amory’s signal, the LCTs lowered their ramps and the LVTs of the first two waves roared into the water and on across the reef. As the tractors started toward the beach, Amory led a boat loaded with navigation buoys and two of the tank gunboats into the coral-free lane that aerial photos showed led to the beach. At the same time, on the opposite (left) flank of the line of departure, the other pair of tanks in LCMs started shoreward, keeping pace with the LVTs for as long as the irregular coral formations would permit. Standing on the bow of his boat, Amory with Flight Lieutenant Marsland at his side, conned the craft through the open water passage while the trailing LCVP dropped buoys to guide the third and succeeding waves of the landing force. The route that had to be used ran 45 degrees to the right of the path the tractors were following over the reefs until it got within 75 yards of the shore, where it “swung sharply to the left to coast six tenths of a mile just barely outside the overhanging trees to the beach at Volupai Plantation.”13

The tanks opened fire with their machine guns to cover the approach of the

tractors to the beach, reserving their 75s for any Japanese return fire. The spray of bullets from all the American landing craft, for the LCVPs and the LVTs fired as well, was finally answered by a few scattered shots from the featureless jungle, and then mortar shells began falling amidst the oncoming tractors. At this moment, the assault troops got all the close air support that the 5th Marines received on D-Day, and that from an unexpected source—a Piper Cub circling overhead, with Captain Petras as pilot and Brigadier General David A. D. Ogden, Commanding General, 3rd Engineer Special Brigade, as observer. Petras, when he saw the shell bursts, turned his tiny plane in over the tree-tops and started dropping the 25-30 hand grenades he carried on “any of the spots where it looked like there might be some Japs.”14 The results of the impromptu bombing were never checked, but the gallant effort drew considerable praise from the men who witnessed it.

At 0835, the LVTs crawled onto the beach, and the Marines of 1/5’s assault platoons clambered over the sides and began advancing cautiously inland. There was little opposition from enemy infantry at first, but mortar rounds continued to fall, with most of them hitting out in the water where the columns of landing boat waves were beginning to thread their way through the buoyed channel. After Lieutenant Colonel Amory waved the tank-LCMs in for a landing, he proceeded out into the narrow passageway to act as control officer to keep the boats from swamping the limited capacity of the beach. After untangling a snarl of landing craft that occurred when the third wave tried to follow the tractors rather than the marked passage, the Army officer spent the morning directing traffic at the corner where the channel turned to parallel the shore.

Major Barba’s two assault companies had little difficulty reaching their assigned objective. Company B encountered the only resistance, a small pocket of enemy riflemen it wiped out as it skirted the edge of the swamp that came right up to the northern edge of the Volupai-Bitokara track. Following his orders, Barba established a beachhead perimeter 200 yards inland and dispatched combat patrols to the flanks of his position as he waited for 2/5 to land and pass through his lines.

Immediately after the first tractors touched down on dry land, a reinforced platoon of 1/5 was sent up the slopes of Little Mt. Worri to eliminate an enemy machine gun nest. The existence of the position had been disclosed to the Marsland-Bradbeer scouting party by the natives. When the patrol found the emplacement, which commanded a good field of fire on the beach, it was abandoned. Pushing on through the thick undergrowth, the Marines sighted and engaged a group of enemy soldiers carrying a machine gun down the mountain toward Volupai Plantation.15 Japanese resistance stiffened appreciably as the 1/5 patrol neared the coconut groves; in the exchange of fire the Marines accounted for a dozen enemy and lost one man killed and another wounded. The patrol leader called for another platoon to help him destroy the position he had developed, but

was given orders to hold up where he was until the 2nd Battalion arrived on the scene.

The limited area for maneuver directly behind RED Beach and the narrow passage that had to be used to reach the shore slowed unloading appreciably. When Major Gayle reached the seaward end of the channel at 1230, reserve elements of his battalion were still landing, as were the firing batteries of Major Noah P. Wood, Jr.’s 2/11, carried in the LCMs of the last two waves. Company E of 2/5 had already passed through the 1st Battalion’s lines at 1100 and run up against the enemy strongpoint located by the 1/5 patrol earlier in the morning.

Three of the medium tanks which had furnished the naval gunfire for the assault landing came up the trail to support Company E in its attack; the fourth tank was bogged down in soft ground at the beach. When the lead Sherman opened fire on the Japanese, it quickly silenced a machine gun that had been holding up the infantry. Then, as the big machine ground ahead on the mud-slickened track, enemy soldiers leaped out of the brush on either flank and attempted to attach magnetic mines to its sides. One man was shot down immediately by covering infantry; the other succeeded in planting his mine and died in its resulting blast, taking with him a Marine who had tried to stop the contact. The mine jammed the tank’s turret and momentarily stunned the crew; luckily, the Marines inside also escaped injury from an antitank grenade that hit and penetrated the turret at about the same time. The damaged tank pulled off the trail to let the following armor come through and lead Company E’s assault. Later, when the tank attempted to move on up the trail, it exploded a mine that smashed one of its bogie wheels. The presence of land mines resulted in a hurry-up call to division for detectors.

Rooting out the enemy from his trenches and emplacements on the edge of the coconut plantation, the tank-infantry team crushed the opposition and moved ahead with 1/5’s 81-mm mortars dropping concentrations on any likely obstacle in the way. As Gayle took command of the attack, the Marines had a much clearer idea of what they were going to run up against. At the height of the battle for the enemy position, a map showing the defenses of the Talasea area had been found on the body of a Japanese officer, and, as happened so many times on New Britain, intelligence indoctrination paid off. The document was immediately turned in, not pocketed as a souvenir, and, by 1300, the regimental intelligence section was distributing translated copies.

Once it had passed the Japanese defenses near the beach, the 2nd Battalion, with Company E following the track and Company G moving along the mountain slopes on the right flank, made rapid progress through the plantation. At about 1500, five P-39s of the 82nd Reconnaissance Squadron at Cape Gloucester flew over the peninsula, but could not locate the Marine front lines, so they dropped their bombs on Cape Hoskins instead.16 At dusk, Major Gayle ordered his two assault companies to dig in for all-around defense,

while he set up with his headquarters and reserve in a separate perimeter at the enemy position that had been reduced during the day’s fighting. The 2nd Battalion, 11th Marines had registered its batteries during the afternoon, and the pack howitzers now fired harassing missions through the night to discourage any counterattacks from forming.

The artillery had taken a beating from the Japanese mortars during the day, as the enemy 90-mm shells exploded all over the crowded beach area. Some of the 75s had to set up almost at the water’s edge so that they could have an unmasked field of fire. Corpsmen going to the aid of artillerymen who were hit while unloading and moving into position all too often became casualties themselves. During the action on 6 March, the 5th Marines and its supporting elements lost 13 men killed and 71 wounded; 9 of the Marines who died and 29 of those who were wounded were members of 2/11. Fifty of the regiment’s seriously wounded men were loaded in an LCM and sent back to Iboki at 1830. The toll of counted enemy dead was 35; if there were Japanese wounded, they were evacuated by the elements of the Terunuma Force that had pulled back as 2/5 advanced.

Colonel Smith could count his regiment well established ashore at the end of D-Day. In the next day’s attack, he planned to keep pressure on the Japanese, not only along the vital cross-peninsula track, but also in the mountains that overshadowed it. Captain Terunuma, in his turn, was ordering the moves that would stave off the Marine advance and protect the elements of the Matsuda Force which were just starting to cross the base of the peninsula.

Securing Talasea17

To reinforce the shattered remnants of the small Volupai area garrison which had made a hopeless attempt to stem the Marine advance, Terunuma sent his 4th Company, reinforced with machine guns and mortars, “to check the enemy’s attack.”18 At dawn on 7 March, patrols from 2/5 scouting the trail to Bitokara found the Japanese dug in not 50 yards from the Marines’ forward foxholes. When Major Gayle’s assault company (E) led off the morning’s attack, the enemy entrenchments were found deserted. One of the deadly 90-mm mortars was captured intact with shellholes from 2/11’s fire as close as five feet to its emplacement. Passing swiftly through the abandoned hasty defenses, the 2nd Battalion pressed on towards the coast with patrols ranging the foothills that dominated the trail. As Gayle’s advance guard neared Mt. Schleuther just before noon, elements of the 4th Company, 54th Infantry swept the track clear with a deadly concentration of fire. It was soon evident that the Japanese force, which was holding a position on the northwest slopes of the mountain, was too strong to be brushed aside. The pattern of enemy fire, in fact, showed that the Japanese were

moving to outflank the Marines below and cut them off from the rest of the battalion column.

While Company E built up a strong firing line amid the dripping undergrowth along the trail, Major Gayle sent Company F directly up the steep slopes to hit the enemy troops trying to push west. Moving forward behind artillery and mortar supporting fires, the 2nd Battalion Marines beat the Japanese to the dominant ground in the area and drove the losers back with heavy casualties. Coming up on the extreme right of Company F’s position, a supporting weapons platoon surprised a machine gun crew setting up, wiped out the luckless enemy, and turned the gun on the retreating Japanese. As the firing died away, the bodies of 40 enemy soldiers testified to the fury of the action. For night security, 2/5 organized a perimeter encompassing its holding on Mt. Schleuther and the track to Bitokara.

Colonel Smith’s attack on 7 March was to have been a two-pronged affair with 2/5 moving along the main trail and 1/5 heading into the mountain mass toward the village of Liapo behind Little Mt. Worri and then east to the Waru villages, believed to be the center of enemy resistance. The plan depended upon the 3rd Battalion’s arrival early on D plus 1 to take over defense of the beachhead. Lieutenant Colonel Deakin had orders to board the landing craft returning from Volupai and make a night passage to RED Beach to be on hand at daybreak to relieve the 1st Battalion. General Rupertus, who was present at Iboki, countermanded the order and directed that no boats leave until after dawn on 7 March. The result of this unexpected change of plans, made to lessen the risk in transit through uncharted waters, was that 3/5 arrived at Volupai late in the afternoon.

After it became clear the reserve would be delayed, a reinforced company of the 1st Battalion was started inland for Liapo to pave the way for the next day’s operations. When the trail disappeared in a clutter of secondary growth, the company hacked its way onward on a compass course, but ended the tiring advance some distance short of the target. The approach of darkness prompted the isolated Marine unit to set up in perimeter defense. The night passed without incident.

On 8 March, Major Barba’s battalion, moving to the east of Little Mt. Worri, started toward Liapo along two separate paths. Unfortunately, a native guide, dressed in cast-off Japanese clothing, leading a column headed by Company B, was mistaken for the enemy by a similar Company A column. In the brief outburst of fire that followed the unexpected encounter, one man was killed and several others wounded. Shortly afterwards, near Liapo, the battalion found the east-west trail it was seeking and joined the company that had spent the night in the jungle. Although it encountered no Japanese opposition as it moved towards its objective during the remainder of the day’s advance, 1/5 found the rugged terrain a formidable obstacle. The men climbed and slid through numerous ravines and beat aside the clinging brush that often obscured the trace of the path they were following. At nightfall, Barba’s units set up in defense a few hundred yards short of their goal.

Major Gayle’s battalion had a hard time with both enemy and terrain on 8 March, but not until it had seized a sizeable chunk of the regiment’s primary objective. A

patrol out at daybreak found the last known position of the Japanese manned only by the dead: 12 soldiers, most of them victims of American artillery and mortar fire. Another patrol discovered a sizeable enemy force 500 yards ahead at Bitokara, and Gayle readied a full-strength attack. When the battalion jumped off, with assault platoons converging from the foothills and the track, it found that the Japanese had pulled out again. Bitokara was occupied early in the afternoon, and scouts were dispatched along the shore to Talasea. Again there was plenty of evidence of recent enemy occupation but no opposition. Taking advantage of the situation, Gayle sent Company F to occupy Talasea airdrome nearby.

Scouts who climbed the slopes of Mt. Schleuther, which looked down on Bitokara, soon found where some of the missing Japanese had gone. A well-intrenched enemy force was located on a prominent height that commanded the village, and Gayle made preparations to attack. At 1500, Company E, reinforced with heavy weapons, drove upward against increasing resistance. The fire of a 75-mm mountain gun and a 90-mm mortar, added to that from rifles and machine guns, stalled the Marines. After an hour’s fighting, during which the company sustained 18 casualties, Gayle ordered it to withdraw to Bitokara for the night. When the Japanese began to pepper the village with 75-mm rounds, concentrating their shelling on 81-mm mortar positions near the battalion command post, Gayle called down artillery on the height. The American howitzers and mortars continued to work over the enemy position all night long.

At 0800 on the 9th, a coordinated attack by companies of both assault battalions was launched to clear Mt. Schleuther and capture the Waru Villages. The artillery and mortar concentrations that preceded the jump-off and the powerful infantry attack that followed hit empty air. One dead soldier and two stragglers were all that was left of the defending force that had fought so hard to hold the hill position on the previous afternoon. The prisoners stated that the main body of the Terumuma Force had moved south down the coast on the night of 7 March, leaving a 100-man rear guard to hold off the Marines. This last detachment had taken off in turn after beating back 2/5’s attack on the 8th.

Patrols of the 5th Marines searched Garua Island and the entire objective area during the rest of the day and confirmed the fact that the Japanese had departed, leaving their heavy weapons behind. Colonel Smith moved the regimental command post to Bitokara during the afternoon and disposed his 1st Battalion around the Waru villages, the 2nd at Talasea and the airdrome, and left the 3rd to hold RED Beach. He then informed division that Talasea was secured, and that the 5th Marines would patrol Willaumez Peninsula to clear it of the enemy.

The end of Japanese resistance in the objective area gave the Marines use of an excellent harbor and brought a welcome end to use of RED Beach. Colonel Smith directed that all supply craft would land their cargoes at Talasea from 9 March onward. Marine pioneers and Army shore party engineers were ordered to improve the Volupai-Bitokara track enough to enable them to move all supplies and equipment to Talasea; the job took three days of hard work. The track was deep in mud from the effects of rain and heavy traffic

as evidenced by three medium tanks trapped in its mire.

Amphibian tractors had again proved to be the only vehicles that could keep up with the Marine advance; 2/5 used the LVTs as mobile dumps to maintain adequate levels of ammunition and rations within effective supporting distance. When the occasion demanded, the tractors were used for casualty evacuation, too. Although the ride back to the beach was a rough one for a wounded man, it was far swifter than the rugged trip that faced him with stretcher bearers struggling through mud.

The cost of the four-day operation to the 5th Marines and its reinforcing units was 17 men killed and 114 wounded. The Japanese lost an estimated 150 men killed and an unknown number wounded. The fighting had been sporadic but sharp, and Captain Terunuma had engaged the Marines just enough to earn the time that the Matsuda Force remnants needed to escape. The retirement of the Terunuma Force was deliberate; at Garilli, four miles south of Talasea, the Japanese halted and dug in to await the Marines.

Mop-up Patrols19

When General Sakai issued his withdrawal orders for the various elements of the 17th Division, he was quite anxious to recover the 1,200-man garrison of Garove Island. Until the Marines landed at Volupai, he was stymied in this wish by Eighth Area Army’s desire to keep the island in use as a barge relay point. Once the Americans had established themselves on Willaumez Peninsula, Garove was no longer of any value to the Japanese.20 Resolving to risk some of the few boats and landing craft that he had left to evacuate the garrison, Sakai ordered the 5th Sea Transport Battalion to load as many men as could crowd aboard the three fishing vessels and the one sampan available and sail for Ulamona. (See Map 31.)

The jam-packed boats, carrying about 700 men, left Garove shortly after midnight on 6 March and reached Ulamona unscathed the next afternoon. On their return voyage that night, the boats were intercepted by American torpedo boats and sunk. Immediately, the commander of the 8th Shipping Engineers, who was holding three large landing craft in reserve for this purpose at Malalia, sent them directly to the island to bring off the remainder of the garrison. The craft were discovered by torpedo boats and sunk after a running gun battle. Despite these losses, three more landing craft were sent to the island where they picked up 400 men and escaped to Rabaul without encountering any of the deadly torpedo boats or being spotted by Allied aircraft.

The waters around Willaumez Peninsula became increasingly unhealthy for the Japanese as the APPEASE Operation wore on. On the 9th of March, while an LCT carrying supplies to Talasea rounded the northern end of the peninsula, it sighted and shot up four barges lying ill-hidden amidst the overhanging foliage on

the shore. On the same day, LCMs ferrying Marine light tanks, which were a more seaworthy load than the Shermans, encountered a Japanese landing craft and drove it ashore with a torrent of 37-mm canister and .30-caliber machine gun fire. The terrier-like torpedo boats were the major killers, however, and, after a patrol base was established in Garua Harbor on 26 March, the northern coast of New Britain as far east as Gazelle Peninsula was soon swept clean of enemy craft.

Before the torpedo boats were out in force, however, the Japanese managed to evacuate a considerable number of men from staging points at Malalia and Ulamona. Except for Colonel Sato’s rear guard, most elements of the 17th Division had reached Cape Hoskins by the end of March. Issuing parties, in the carefully laid-out ration depots along the coastal trail, doled out just enough food to keep the men moving east, and then folded up as the units designated for rear guard at Malalia, Ulamona, and Toriu came marching in.

The only good chance that the Marines at Talasea had of blocking the retreat of General Matsuda’s depleted command was canceled out by the skillful delaying action of Captain Terunuma. A reconnaissance patrol discovered the Japanese position at Garilli on the 10th, and its destruction was a part of the mission given Company K, 3/5, when it moved out toward Numundo Plantation on the 11th. The company found that the enemy force had abandoned Garilli but was set up along the coastal trail about three miles farther south. The small-scale battle that ensued was the first of many in the next four days, as the Japanese blocked the Marines every few hundred yards and then withdrew before they could be badly hurt. An enemy 75-mm gun, dragged along by its crew, helped defend the successive trail blocks and disrupted a number of attempts to rush the Japanese defenses.

Late on the 16th, Company K reached Kilu village and tangled with the Terunuma Force for the last time. As the Marines and the Japanese fought, an LCM carrying Lieutenant Colonel Deakin and an 81-mm mortar section came through the fringing reef. The enemy artillery piece fired on the landing craft, but failed to score a hit. The arrival of the 81s appeared to turn the trick. As soon as the mortars started firing, Captain Terunuma’s men broke contact and faded away.

On the 18th, Company K reached Numundo, and, on the 25th, the whole 2nd Battalion outposted the plantation. Five days later, Major Gayle moved his unit to San Remo Plantation about five miles to the southeast and began patrolling west to the Kulu River and east as far as Buluma, a coastal village halfway to Hoskins airdrome. On the peninsula, 1/5 set up a strong ambush at Garu on the west coast. All units patrolled extensively, making repeated visits to native villages, checking the myriad of side trails leading off the main tracks, and actively seeking out the Japanese. Many stragglers were bagged, but only one organized remnant of the Matsuda Force was encountered in two months of searching. The task of destroying this unit, what was left of Colonel Sato’s reconnaissance regiment, fell to 2/1.

The 1st Marines had the responsibility of maintaining a patrol base at Iboki and spreading a network of outposts and ambushes through the rugged coastal region. In mid-March, Marine and Army patrols both made the trip between Arawe and the

north coast, discovering and using the trails that the Japanese had followed. Sick and emaciated enemy fugitives were occasionally found, but the signs all pointed to the fact that those who could walk were now east of this once important boundary.

Only a few engineer boats could be spared from resupply activities for patrol work. These LCMs and LCVPs were used to transport strong units, usually reinforced platoons or small companies, to points like Linga Linga Plantation and Kandoka where the Japanese had maintained ration dumps. The lure of food was irresistible for the starving enemy troops stumbling through the jungle, and the Marines took advantage of the certainty that the Japanese would at least scout the vicinity of places where they had counted on finding rations.

Near Kandoka on 26 March, Colonel Sato’s advance party ran head-on into a scout platoon from 2/1. The Japanese caught the Marine unit as it was crossing a stream and cut loose in a blaze of rifle and machine gun fire. For three hours, the Americans were pinned down on the stream banks before the arrival of another 2/1 patrol enabled them to withdraw; one Marine was killed and five wounded. Sato, who had several of his own men wounded in the fight, made the decision to bypass Kandoka and cut through the jungle south of the village. He ordered his men to strip themselves of everything but their weapons and ammunition for the push into the swamps at the base of Willaumez. On the 27th, Marine attempts to locate the Japanese column were unsuccessful, but the days of the 51st Reconnaissance Regiment were numbered.

While the head of Sato’s column was nearing Kandoka, the tail was sighted at Linga Linga by one of the 1st Division’s Cubs. The pilot, again the busy Captain Petras, was scouting a suitable landing beach for a large 2/1 patrol. After drawing a map that located the Japanese, he dropped it to the patrol and then guided the engineer coxswains into shore at the rear of the enemy positions. This time the Marines missed contact with Sato’s force, but with the aid of the landing craft they were able to move freely along the coast as additional sightings pinned down the location of the enemy unit.

On 30 March, a small Marine patrol sighted Sato’s rear guard, 73 men accompanied by the redoubtable enemy colonel himself, who was by this time a litter patient. Major Charles H. Brush, 2/1’s executive officer, who was commanding patrol activities in the region, reacted quickly to the report of his scouts. Leaving a trail block force at Kandoka, he plunged into the jungle with the rest of the men available, roughly a reinforced platoon, to engage the Japanese. Shortly before Brush reached the scene, a six-man patrol under Sergeant Frank Chilek had intercepted the Sato column and brought it to a halt by sustained rifle fire. When Brush arrived, Chilek’s unit was pulled back by his platoon leader, who had come up with a squad of reinforcements, so that the stronger Marine force would have a clear field of fire. The Japanese were wiped out, and, miraculously, not a Marine was harmed in the brief but furious battle. At least 55 Japanese were killed in one 100-yard stretch of trail, including Colonel Sato, who died sword in hand, cut down by Chilek’s patrol.

A few elements of the enemy reconnaissance regiment, those near the head of its column, escaped from the battle on 30 March. Without the inspiration of Sato, however, the survivors fell apart as a unit and tried to make their way eastward as individuals and small groups. Most of these men died in the jungle, victims of malnutrition, disease, and the vicious terrain; others were killed or captured by Marine patrols and outposts.

The 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, operating out of its base at San Remo, accounted for many of these stragglers who blundered into ambushes set on the trails that led to Cape Hoskins. Major Komori, who had led the quixotic defense of an airfield no one wanted, was one of those who met his end in a flurry of fire at a 2/5 outpost.

The major, wracked with malaria, had fallen behind his unit, and, accompanied only by his executive officer and two enlisted men, had tried to struggle onward. On 9 April, a Marine outguard killed Komori and two of his party; the sole survivor was wounded and captured. The death of Major Komori brought to a symbolic end the Allied campaign to secure western New Britain.