Part V: Marine Air Against Rabaul

Blank page

Chapter 1: Target: Rabaul

The overriding objective of the Allied campaign in the Southwest Pacific was, at first, to capture, and, later, to neutralize Rabaul. Each successive advance during 1943 had its worth valued by the miles it chopped off the distance to this enemy stronghold. To a large extent, the key to the objectives and pace of CARTWHEEL operations was this distance, measured in terms of the range of the fighter plane. No step forward was made beyond the effective reach of land-based fighter cover.

The firm establishment of each new Allied position placed a lethal barrier of interceptors closer to Rabaul and its outguard of satellite bases. Equally as important, the forward airfields provided a home for the fighter escorts and dive bombers which joined with long-range bombers to knock out the enemy’s airfields. Protected by mounting numbers of Allied planes, many of them manned by Marines, the areas of friendly territory that saw their last hostile aircraft or vessel grew steadily. Japanese admirals learned from bitter experience that their ships could not sail where their planes could not fly.

By carrying the fight to the enemy, Allied air units played a decisive role in reducing Rabaul to impotency. Although this aerial offensive was closely related to the air actions in direct support of CARTWHEEL’s amphibious operations, its importance warrants separate accounting.

Objective Folder1

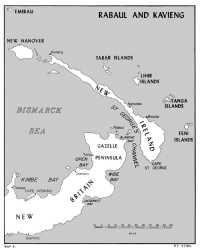

As they fought their way up the Solomons chain and along the enemy coast of eastern New Guinea, few members of Halsey’s and MacArthur’s naval and ground forces had time to consider any Japanese position but the one to their immediate front. To these men, Rabaul was little more than a worrisome name, the base of the enemy ships and planes that attacked them. Allied pilots and aircrews, however, got to know the Japanese fortress and its defenders intimately. The sky over St. George’s Channel, Blanche Bay, and Gazelle Peninsula was the scene of one of the most bitterly fought campaigns of the Pacific War.

To picture Rabaul as it appeared to the men who battled to reach it, to bomb and strafe it, and to get away alive, requires a description of more than the northern tip of Gazelle Peninsula where the town, its harbor, and its airfields were located. To flyers, the approaches were as familiar as

the objective itself, and a strike directed against Rabaul evoked a parade of impressions—long over-water flights; jungle hills slipping by below; the sight of the target—airfield, ship, or town, sometimes all three; the attack and the violent defense; and then the seemingly longer, weary return over land and sea.

In order to fix Rabaul as an air objective, one should visualize its position in midyear 1943 as the powerful hub of the Japanese airbase system in the Southeast Area. To the west on New Guinea, at Hollandia, Wewak, and Madang, were major airdromes with advance airstrips building on the Huon Peninsula and across Vitiaz Strait at Cape Gloucester. Staging fields in the Admiralty Islands gave enemy pilots a place to set down on the flight from eastern New Guinea to Rabaul. Kavieng’s airbase was also a frequent stopover point, not only for planes coming from the west but for those flying south from Truk, home of the Combined Fleet and its carriers. Southeast of New Britain in the Solomons lay the important airfields at Buka Passage at one end of Bougainville and at Buin-Kahili and Ballale Island at the other. Forward strips at Vila and Munda in the New Georgia Group marked the limit of Japanese expansion.

Distances in statute miles from Rabaul to the principal bases which guarded it, and to the more important Allied positions from which it was attacked, are as follows:

| Truk | 795 |

| Guadalcanal | 650 |

| Wewak | 590 |

| Port Moresby | 485 |

| Madang | 450 |

| Munda Point | 440 |

| Dobodura | 390 |

| Lae | 385 |

| Admiralties | 375 |

| Woodlark | 345 |

| Finschhafen | 340 |

| Kahili | 310 |

| Kiriwina | 310 |

| Cape Gloucester | 270 |

| Cape Torokina | 255 |

| Buka Passage | 190 |

| Kavieng | 145 |

The starting point for measuring these distances was a small colonial town that had, in the immediate prewar years, a population of about 850 Europeans, 2,000 Chinese, and 4,000 Melanesians. Quite the most important place in the Australian Mandated Territory of New Guinea, Rabaul was for many years the capital of the mandate. When two volcanic craters near the town erupted in May 1937, the decision was made to shift the government to Lae, but the pace of island life was such that the move had barely begun when the Japanese struck.

The town was located on the shore of Simpson Harbor, the innermost part of Blanche Bay, a hill-encircled expanse six miles long and two and a half wide. One of the finest natural harbors in the Southwest Pacific, the bay is actually the crater of an enormous volcano, with the only breach in its rim the entryway from the sea and St. George’s Channel. Two sheer rocks called The Beehives, which rise 174 feet above the water near the entrance to Simpson Harbor, are the only obstacles to navigation within the bay. There is space for at least 20 10,000-15,000-ton vessels, plus a host of smaller craft, to anchor within Simpson’s bounds. Separated from this principal anchorage by little Matupi Island is Matupi Harbor, a sheltered stretch guarded on the east and north by a wall of mountains. Just inside the

Map 31: Rabaul and Kavieng

headlands, Praed Point and Raluana Point, at the entrance to Blanche Bay are two further protected harbors. Both, Escape Bay in the north by Praed Point and Karavia Bay in the south, are less useful, as their waters are too deep for effective anchorages.

Prominent landmarks, as easily recognizable from the air as The Beehives, are the craters that form a part of the hills surrounding Rabaul. Directly east of Matupi Harbor is Mt. Tavurvur (741 feet), which erupted in 1937, and due north is Rabalankaia Crater (640 feet). These two heights give Crater Peninsula its name, but they are overshadowed by the peninsula’s mountainous ridge which has three companion peaks, South Daughter (1,620 feet), The Mother (2,247 feet), and North Daughter (1,768 feet). The town of Rabaul nestled between the foothills of North Daughter and the narrow sandy beaches of Simpson Harbor. Across Blanche Bay from Mt. Tavurvur is its partner in the 1937 eruption, Vulcan Crater (740 feet), which juts out from the western shore to form one arm of Karavia Bay.

In the years of peace, the land to the south and east of Blanche Bay was extensively planted in coconuts. The rich volcanic soil there was fertile, and, like most of the northern third of Gazelle Peninsula, the area was relatively flat. Most of the 100 or so plantations on the peninsula were located here, with a large part of them to be found in the region north of the Warangoi and Keravit Rivers. The only other considerable plantation area along the northern coast lay between Cape Lambert, the westernmost point on Gazelle Peninsula, and Ataliklikun Bay, into which the Keravit River emptied. The majority of the 36,000 natives who were estimated to be on the peninsula lived in or near this northern sector.

The rest of Gazelle Peninsula, which is shaped roughly like a square with 50-mile-long sides, is mountainous, smothered by jungle, and inhospitable to the extreme. Two deep bights, Wide Bay on the east coast and Open Bay on the west, set off the peninsula from the rest of New Britain. Access to Rabaul from this part of the island was possible by a coastal track, broken frequently by swamps and rivers, and a web of trails that cut through the rugged interior. For the most part, these routes were hard going and usable only by men on foot.

The wild, inaccessible nature of the central and southern sectors of Gazelle Peninsula made the contrast with the Rabaul area all the more striking. Even before the war, the mandate government had developed a good road net to serve the various villages, plantations, and missions. The Japanese made extensive improvements and expanded the road system to connect with their troop bivouacs and supply dumps. Many of these installations were invisible from the air, hidden in the patches of jungle that interspersed the plantations and farms. The major Japanese construction work, however, was done on airfields, and the five that they expanded or built from scratch became as familiar to Allied aircrews as their own home bases.

Both of the small fields maintained at Rabaul by the Royal Australian Air Force were enlarged and made into major airdromes by the Japanese. Lakunai airfield and its hardstands and revetments occupied all the available ground on a small peninsula that ran out to Matupi Island. A 4,700-foot coral runway, varying in

width from 425 to 525 feet, began at Simpson Harbor and ended at Matupi Harbor. The sharply rising slopes of Rabalankaia Crater blocked any extension of the field to the northeast and a small creek was a barrier on the northwest.

The other former RAAF base, Vunakanau airfield, was located at an altitude of 1,000 feet on a plateau about 11 miles southwest of Rabaul. Except for two coconut plantations, the plateau was covered by scrub growth and kunai grass. The ground was quite irregular and laced with deep gullies, and the 5,100 x 750-foot runway the enemy built was the practical limit of expansion. Centered on this grass-covered larger strip was a concrete runway, 4,050 feet long and 140 feet wide. Vunakanau became the largest Japanese airdrome at Rabaul, and its straggling network of dispersal lanes and revetments spread over an area of almost two square miles.

The longest airstrip at Rabaul was constructed at Rapopo on the shore of St. George’s Channel about 14 miles southeast of the town and a little over 5 miles west of Cape Gazelle, the northeast corner of Gazelle Peninsula. Designed and built as a bomber field, Rapopo was sliced through the center of a coconut plantation that gave it its name. The clearing for the north-south strip ran 6,900 feet from the sea to a river that effectively barred further extension. A coral-surfaced runway began about 1,600 feet from a low, coastal bluff and occupied the full width of the cleared space.

Well inland from the other airfields, 15 miles southeast of Vunakanau and 8 miles southwest of Rapopo, the Japanese built Tobera airfield. Its runway, 5,300 x 700 feet, with a hard-surfaced central strip 4,800 x 400 feet, was situated on a gently sloping plateau that divided the streams which flowed north to the sea from those which ran south to the Warangoi River. Like most of its companion fields, Tobera was constructed in a plantation area with its dispersal lanes and field installations scattered amidst the coconut trees.

The fifth airfield at Rabaul was located on Ataliklikun Bay just north of the Keravat River and 26 miles southwest of Rabaul. Keravat airfield was plagued by drainage problems and had perhaps the poorest location and the greatest engineering problems. By the end of November 1943, the Japanese had been able to grade and surface a 4,800 x 400-foot runway, but Keravat never became fully operational and saw very limited use as an emergency landing ground.

Caught up and deserted by the rush of events was an auxiliary airfield that was started and never finished on Duke of York Island. The island is the largest of a group of 13 islets that stand in St. George’s Channel midway between New Britain and New Ireland. The press for additional airstrips on which to locate and, later, to disperse and protect Rabaul’s air garrison was met instead by fields on New Ireland.

There were four operational airfields on that narrow, 220-mile-long island with two, Namatami and Borpop, sited about 50 miles northeast of Rabaul on New Ireland’s eastern shore. At Kavieng on the island’s northern tip and Panapai close by was an extensive airbase, the largest in the Bismarcks outside of Rabaul’s immediate environs. Kavieng and Rabaul had been seized at the same time and grew apace with each other until they both, in turn, were relegated to the backwash of the war by the withdrawal of their aerial defenders.

Garrison Forces2

In January 1942, Rabaul had a small garrison of about 1,350 men, a reinforced Australian infantry battalion. Kavieng had no defenders at all save a few police boys. The towns themselves and the islands on which they stood were ripe for the taking whenever the Japanese got around to the task. In the enemy’s war plans, elements of the Fourth Fleet that had seized Guam and Wake made up the Rabaul Invasion Force. The assault troops at Rabaul would be the South Seas Detached Force, an Army brigade that had landed at Guam, reinforced by two companies of the Maizuru 2nd Special Naval Landing Force, the victors at Wake.3 The remainder of the Maizuru 2nd was detailed to occupy Kavieng.

The Rabaul Invasion Force rendezvoused at sea north of the Bismarcks on 19 January, and, on the next day, enemy carrier-based bombers and fighters hit both targets. At Rabaul, the defending air force—five RAAF Wirraway observation planes—was quickly shot out of the sky, and the airstrips were bombed. The carrier planes made diversionary raids on Lae, Salamaua, and Madang on the 21st, and then hit Rabaul again on the 22nd, knocking out Australian gun positions on North Daughter and at Praed Point.

After this brief preparation, Japanese transports and supporting vessels sailed into Blanche Bay near midnight on 22 January, and the assault troops began a staggered series of landings shortly thereafter. The enemy soldiers stormed ashore at several points along the western beaches of Simpson Harbor and Karavia Bay, while the naval landing force hit Rabaul and Lakunai airfield. The Australians, spread out in small strongpoints along the shore and on the ridge just inland, fought desperately in the darkness but were gradually overwhelmed and forced to pull back. As daylight broke, the 5,000-man Japanese landing force called down naval gunfire and air support to hammer the retreating defenders. At about 1100, the Australian commander, seeing that further resistance would be fruitless, ordered his men to break contact, split up into small parties, and try to escape.

The Japanese harried the Australian troops relentlessly, using planes and destroyers to support infantry pursuit columns.

Most of the defenders were eventually trapped and killed or captured on Gazelle Peninsula, but one group of about 250 officers and men stayed a jump ahead of the Japanese, reached Talasea after an exhausting march, and got away safely by boat, landing at Cairns, Queensland, on 28 March. Naturally enough, the fact that they were driven from Rabaul rankled the Australians, but the opportunity for retaliation was still years away.

Flushed with success, the Japanese set about extending their hold throughout the Bismarcks, the Solomons, and eastern New Guinea. Rabaul served as a funnel through which troops, supplies, and equipment poured, at first in a trickle, then in a growing stream until the defeats at Guadalcanal and Buna-Gona checked the two-pronged advance. In the resulting reassessment of their means and objectives, the Japanese reluctantly decided to shift to a holding action in the Solomons in order to concentrate on mounting a sustained offensive on New Guinea. Essential to this enemy decision was the fact that a system of airfields existed between Rabaul and Guadalcanal.

The 650-mile distance from Henderson Field to Vunakanau and Lakunai was a severe handicap to Japanese air operations during the Guadalcanal campaign. The need for intermediate bases was obvious, and enemy engineers carved a succession of airfields from plantations, jungle, and grasslands in the central and northern Solomons during the last few months of 1942. Only Buka, which was operational in October, was completed in time to be of much use in supporting air attacks on the Allied positions on Guadalcanal. Fields at Kahili, Ballale, Vila, and Munda, however, were all in use by the end of February 1943, some as staging and refueling stops and the others as fully operational bases. It was these airfields that furnished Rabaul the shield that the Japanese needed to stave off, blunt, or delay Allied attacks from the South Pacific Area. The task of manning these bases was exclusively the province of the Eleventh Air Fleet.

The Eighth Area Army’s counterpart of Admiral Kusaka’s air fleet, the 6th Air Division, was almost wholly committed to support of operations on New Guinea by the end of 1942. During the bitter fighting in Papua, Japanese air support had been sporadic and sparse, a situation that General Imamura intended to correct. Rapopo Airfield at Rabaul, which became operational in April 1943, was constructed by the Army to accommodate a growing number of planes, and work was begun on a Navy field at Keravat to handle even more. At about this time, the strength of the 6th Air Division peaked at 300 aircraft of all types. Many of these planes were stationed at Rabaul, but a good part were flying from fields on New Guinea, for Imamura had ordered the 6th to begin moving to the giant island on 12 April.

On eastern New Guinea, as in the Solomons, airfields closer to the battle scene than those at Rabaul were needed to provide effective air support to Japanese troops. Consequently, two major airbases were developed at Wewak and Madang on the coast northwest of the Huon Peninsula. Despite the heavy use of these fields, the operating efficiency of Army air units dropped steadily in the first part of 1943. The rate at which 6th Air Division planes were destroyed by Allied pilots and gunners was so great that even an average

monthly flow of 50 replacement aircraft could not keep pace with the losses. In July, Tokyo added the 7th Air Division from the Netherlands East Indies to Eighth Area Army’s order of battle and followed through by assigning the Fourth Air Army to command and coordinate air operations. By the time the air army’s headquarters arrived at Rabaul on 6 August, a move of all Army combat aircraft from the Bismarcks was well underway.

In light of the desperate need of the Eighteenth Army on New Guinea for air support, Imperial General Headquarters had urged General Imamura to leave the air defense of Rabaul entirely to the Navy and concentrate all his air strength in the Eighteenth’s sector. After discussing the proposed change with Admiral Kusaka, who would acquire sole responsibility for directing air operations at Rabaul, the general ordered the transfer. By the end of August, Fourth Air Army’s headquarters was established at Wewak, and all Army aircraft, except a handful of reconnaissance and liaison types, were located on New Guinea.

When the last Japanese Army plane lifted from Rapopo’s runway, the crucial period of the Allied aerial campaign against Rabaul was still in the offing. The men, the planes, and the units that would fight the enemy’s battle were essentially those which had contested the advance of South Pacific forces up the Solomons chain in a year of furious and costly air actions. In that time, Japanese naval air groups were rotated in and out of Rabaul, and were organized and disbanded there with little apparent regard for a fixed table of organization. Two administrative headquarters, the 25th and 26th Air Flotillas, operated under Eleventh Air Fleet to control the air groups; for tactical purposes, the flight echelons of the flotillas were organized as the 5th and 6th Air Attack Forces. Since the accounts of senior surviving air fleet officers, including Admiral Kusaka, differ considerably in detail on enemy strength and organization, only reasonable approximations can be given for any one period.

In September 1943, on the eve of the Allied air offensive against Rabaul, the Eleventh Air Fleet mustered about 300 planes and 10,000 men, including perhaps 1,500 flying personnel. Three fighter groups, the 201st Air Group, the 204th, and the 253rd, each with a nominal strength of 50 aircraft and 75 pilots, were the core of the interceptor force. One medium bomber unit, the 705th Air Group, was present, together with elements of at least two more groups, but heavy losses had reduced them all to skeleton proportions of a bomber group’s normal strength of 48 planes and 300 crewmen. There was one combined dive bomber-torpedo bomber outfit, the 582nd Air Group, whose strength was 36 attack aircraft and 150 crewmen. Two reconnaissance groups, the 938th and 958th, each with 28 float planes and about 100 flying personnel, completed the air fleet’s complement of major units. A few flying boats, some transports assigned to each air group, and headquarters and liaison aircraft were also present.

To keep up with the steady drain of combat and operational losses, Tokyo sent 50 replacement aircraft to Rabaul each month. Approximately one-third of these planes were lost in transit, but the remainder, 80 percent of them fighters, reached their destination after a long overwater flight staged through Truk and Kavieng. Land-based naval air units in quiet sectors of the Pacific were drawn

upon heavily for planes and pilots and received in exchange battle-fatigued veterans from Rabaul.4 The drain of Japanese naval planes and personnel from the Netherlands Indies grew so serious toward the end of 1943 that the Army’s 7th Air Division had to be returned to the area to plug the gap.

In every possible way, the Japanese tried to ready Rabaul’s air garrison for the certain Allied onslaught. Flight operations from the most exposed forward airstrips in the Solomons were sharply curtailed to conserve aircraft and crews. At all airfields, blast pens and dispersal areas were strengthened and expanded, and antiaircraft guns were disposed in depth to cover approaches. Tobera airfield was rushed to completion to lessen the concentration of aircraft at Vunakanau and Lakunai and to provide space for reinforcements from the Combined Fleet. Poised at Truk, two carrier air groups with about 300 planes stood ready to join Kusaka’s command when the situation worsened enough to demand their commitment. Although the newest Japanese plane models were to be fed in to Rabaul’s air defense as they became available, the overwhelming majority of the planes that would rise to meet the Allied attacks would be from one family of fighters, the Zeros.

Enemy Planes and Aircrews5

During the first nine months of the war, the Allies tried to identify Japanese air craft as the enemy did, by the year of initial adoption and type. The calendar the Japanese used was peculiarly their own, with the year 2597 corresponding to 1937, and there were a number of different Type 97s in use, among them an Army fighter, an Army medium bomber, a Navy torpedo bomber, and a Navy flying boat. This was the system that gave rise to the name Zero for the Type O Navy fighter plane that was first employed in 1940 during the fighting in China.

By the time of Pearl Harbor, the Zero had replaced its Type 96 predecessor as the standard Japanese carrier fighter. Based on its performance capabilities, enemy intelligence officers were confident that the plane could gain control of the air over any battle area, and that in aerial combat, “one Zero would be the equal of from two to five enemy [Allied] fighter planes, depending upon the type.”6 This assessment, unfortunately, proved to be too close to the truth for the peace of mind of Allied pilots. In a dogfight, the Zero was at its best; at speeds below 300 miles per hour, it could outmaneuver any plane

that it encountered in 1942. By the end of that year, however, the Zero had officially lost its well-remembered name among the Allies and had become instead, the Zeke.

The name change, part of a new system of enemy aircraft designation, was ordered into effect in the Southwest Pacific in September 1942 and adopted in the South Pacific in December. The Japanese identification method, with all kinds of planes assigned the same type-year, proved too cumbersome for Allied use. In its stead, enemy aircraft were given short, easily pronounced code titles; fighters and floatplanes received masculine names, with feminine names going to bombers, flying boats, and land-based reconnaissance planes. Despite the switch, the name Zero died hard, particularly among Marine pilots and aircrews in Halsey’s forces, and it was at least six months before they gave the substitute, Zeke, popular as well as official sanction.7

The Zeke was unquestionably the most important enemy plane that fought in the Rabaul aerial campaign. Developed by the Mitsubishi Aircraft Company, the original version of the fighter had two models, one with folding wing tips for carrier use and the other built to operate from land bases. An all-metal, single-engine monoplane, the Zeke had low-set wings tapered to a rounded tip. The pilot sat high in an enclosed cockpit controlling two 7.7-mm machine guns synchronized to fire through the propeller and two 20-mm cannon fixed in the wings. Performance assets were rapid take-off and high climbing rates, exceptional maneuverability at speeds up to 300 miles per hour, and a total range of 1,580 miles with maximum fuel load and economy speeds. The Zeke’s principal liabilities as a combat aircraft, ones it shared with every Japanese military plane, were relatively flimsy construction and a lack of armor protection for pilot, fuel, and oxygen.

Most of the Zekes that defended Rabaul in late 1943 were of a later model than the 1940. The improved planes had the same general appearance but were fitted with racks to carry one 132-pound bomb under each wing and had a more powerful motor that added 15 miles to the former maximum speed of 328 miles per hour at 16,000 feet. Another model of the basic Type O Navy fighter, one with the same engine, armament, and flight performance as the later model Zeke, was the Hamp.8 Identified at first as a new plane type because of its shorter, blunt-tipped wing, the Hamp was later recognized as a legitimate offspring of the parent Zero. The only other Navy fighter operating out of Rabaul in significant numbers was the Rufe, a slower floatplane version of the Zeke.

The standard enemy land-based naval bomber was the versatile Betty, a 1941 model that was as frequently used on transport, reconnaissance, and torpedo bombing missions as it was for its primary purpose. In the pattern of most enemy medium bombers, the Betty was a twin-engine, mid-wing monoplane with a cigar-shaped fuselage and a transparent nose, cockpit, and tail. Operated by a crew of

seven to nine men, the plane could carry a maximum bomb load of 2,200 pounds and was armed with four 7.7-mm machine guns, all in single mounts, and a 20-mm cannon in its tail turret. The Betty was fast, 276 miles per hour at 15,000 feet, and had a range of 2,110 miles at cruising speed with a normal fuel and bomb load. To achieve this relatively high speed and long range, Mitsubishi Aircraft’s designers had sacrificed armor and armament. Much of the plane was built of lightweight magnesium, a very inflammable metal, and in the wing roots and body between were poorly protected fuel and oil tanks. “The result was a highly vulnerable aircraft so prone to burst into flames when hit that Japanese aircrews nicknamed it ‘Type 1 Lighter.’”9

Even more vulnerable to Allied fire than the Betty was the principal dive bomber in the Eleventh Air Fleet, the Val. The pilot, who controlled two forward firing 7.7-mms in the nose of the monoplane, sat over one unprotected fuel tank and between two others in the wings; the gunner, who manned a flexible-mount 7.7-mm in the rear of the cockpit enclosure, was uncomfortably close to the highly explosive oxygen supply. A pair of bomb racks located under each of the plane’s distinctive elliptical-shaped wings, and one under the body between the fixed landing gear, enabled the Val to carry one 550- and four 132-pound bombs. The dive bomber’s best speed was 254 miles per hour at 13,000 feet, and its normal range at cruising speed with a full bomb load was 1,095 miles. When it flew without escort, the Val was easy game for most Allied fighters.

The slowest of the major plane types at Rabaul, and the one with the poorest performance, was a torpedo bomber, the Kate. The plane was as poorly armed as the Val and was almost as inflammable. The two- to three-man crew all sat in a long, enclosed cockpit atop a slim 33-foot body; the wing span of the monoplane, 50 feet, gave it a foreshortened look. One torpedo at 1,760 pounds was its usual load, although a 1,000-pound bomb or two 250-pound bombs could be carried instead. Since it had a weak engine and its lethal cargo was stowed externally, at emergency speed and its best operating altitude, 8,500 feet, the Kate could only make 222 miles per hour.

Aside from those mentioned, many other Japanese Navy aircraft and an occasional Army plane were encountered and engaged by the Allies in aerial attacks on Rabaul. The Zeke fighter family, however, furnished most of the interceptors and escorts, and the Bettys, Vals, and Kates delivered the dwindling enemy offensive thrusts. A once-numerous fleet of Japanese flying boats, reconnaissance planes, and transports fell away into insignificance by October 1943. The feebly armed and unarmed survivors avoided Allied aircraft like a plague, since they were dead birds if caught.

There was no enemy plane that flew from Rabaul that was not a potential flaming death trap to its crew. To meet the specifications outlined by the Japanese Navy, aircraft designers sacrificed safety to achieve maneuverability in fighters and long range in bombers. Heightening the losses suffered by these highly vulnerable planes was the plummeting level of skill of their flying and maintenance personnel.

Captured Japanese Zero, showing U.S. plane markings, aloft over the San Diego area during test flights. (USN 80-G-11475)

Japanese Val dive bombers are shown armed and ready to take off on a bombing mission in film captured early in 1943. (USN 80-G-345598)

By 1943, the problem of keeping aircraft in forward areas in good operational condition and adequately manned had become acute. The senior staff officer of the 25th Air Flotilla during the critical period of the battle for Rabaul recalled:

In the beginning of the war, during 1942, if 100% of the planes were available for an attack one day, the next day 80% would be available, on the third day 50%. In 1943, at any one time, only 50% of the planes were ever available, and on the next day following an all-out operation only 30% would be available. By the end of 1943, only 40% at any one time would be serviceable. In 1942, the low availability was due to lack of supply; from 1943 on, it was due to lack of skill on the part of maintenance personnel and faulty manufacturing methods. Inspection of the aircraft and spare parts, prior to their delivery to Rabaul, was inadequate, and there were many poorly constructed and weak parts discovered. The Japanese tried to increase production so fast that proper examination was impossible.10

Japanese naval aviation had begun the war with 2,120 aircraft of all types, including trainers. In April 1943, after 16 months of heavy fighting, the total strength stood at 2,980, which meant that the manufacturers had been able to do little more than keep pace with combat and operational losses. In the succeeding year, the production rate nearly doubled, but losses soared also; there were 6,598 planes on hand in April 1944, but the standard of construction had deteriorated badly.11

Even more serious than the sag in the quality of naval aircraft maintenance and production was the steady attrition of experienced flight personnel. The pilots who began the war averaged 800 hours of flying time, and many of them had combat experience in China. Relatively few of these men survived until the end of 1943; a great many died at Coral Sea and Midway and in air battles over Guadalcanal. Others crashed trying to stretch the limited range of Vals and Kates to cover the long stretch between Rabaul and Guadalcanal. The replacements, pilots and aircrews alike, could not hope to match the worth of the men whose places they took.

Two years of flight training and practice had been the prewar requisite to make a man a qualified naval pilot or “observer” (bombardiers, navigators, and gunners). In 1941, the training time was cut about in half. Pilots spent about 60 hours in primary and intermediate trainers, observers spent 44, both in a six-month period. Flight training in combat types, spread over a four-to-six month period, was 100 hours for pilots and 60 hours for observers. Thereafter, 150 hours of tactical flight training was programmed for men in the units to which they were assigned. At Rabaul, however, this phase was spent in combat, and those few who survived 150 hours could count themselves as living on borrowed time.

The majority of flying personnel in the Japanese Navy were warrant officers, petty officers, and naval ratings. Regular and reserve officers selected for pilot and observer training were intended for command billets; they were few in number, and, as combat flight leaders, their losses were disproportionately great. In the Rabaul area by the fall of 1943, a representative Betty unit with 11 planes had only one officer among 23 pilots and one among 38 observers, while all of the 39

radiomen and mechanics were enlisted men.12

An experienced Japanese combat air commander, operations officer at Buin-Kahili during September 1943, characterized these aircrews as personifying:

... Japan’s people on the battlefield, for they came from every walk of life. Some of them carried the names of well-known families; some noncommissioned officers were simple laborers. Some were the only sons of their parents. While we maintained strict military discipline on the ground, with proper observance for rank, class, and age, those differences no longer existed when a crew’s plane lifted its wheels from the ground.

The enemy cared little about the groups which constituted our aircrews and there existed no discrimination on the part of the pilot who caught our planes in his sights! Our air crews were closely knit, for it mattered not one whit whether an enlisted man or an officer manned the machine guns or cannon. The effect was exactly the same. Unfortunately this feeling of solidarity of our aircrews was unique in the Japanese military organization.13

Fighter pilot or bomber crewman, the Japanese naval flyer who fought at Rabaul was aware that he was waging a losing battle. The plane he flew was a torch, waiting only an incendiary bullet to set it alight. The gaping holes in his unit left by the death of veterans were filled by young, inexperienced replacements, more a liability than an asset in combat air operations. Despite the handicaps under which he fought—out-numbered, out-gunned, and out-flown—the enemy flyers fought tenaciously right up to the day when Rabaul was abandoned to its ground defenders.