Part VI: Conclusion

Blank page

Chapter 1: Encirclement

In the late summer of 1943, while the Joint Chiefs were deciding to neutralize Rabaul rather than capture it, General MacArthur’s staff was preparing plans for the operations which would follow Bougainville and Cape Gloucester and complete the encirclement of the key New Britain base. With a tentative target date of 1 March 1944, MacArthur intended to seize Kavieng, using SoPac forces, and the Admiralties, employing his own SWPA troops, planes, and ships. The establishment of Allied airfields at Finschhafen and Cape Gloucester meant that the Admiralties’ landings could be covered adequately by land-based fighters, but Kavieng operations required carrier air support. Even the boost in range given SoPac fighters by airfields at Cape Torokina would not be enough to provide effective escorts and combat air patrols over Kavieng.

Once the Central Pacific offensive got underway with operations in the Gilberts, it appeared that mounting demands on the Pacific Fleet’s shipping resources would serve to put off D-Day at Kavieng until about 1 May 1944.1 Faced with the possibility that there would be “a six months interval between major South Pacific operations” which might “kill the momentum of the South Pacific drive,” Admiral Halsey consulted General MacArthur, who gave “his unqualified approval” to the scheme for an intermediate operation “which would keep the offensive rolling, provide another useful base, and keep the pressure on the enemy.”2

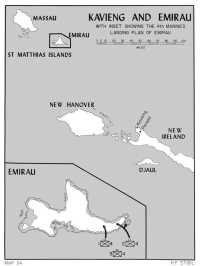

As Halsey ordered his staff to prepare the plans for the seizure of the Green Islands, the intermediate target he had selected, he also directed them to study the possibility of seizing Emirau Island in the St. Matthias Group as an alternative to Kavieng. ComSoPac felt that the time was ripe for another bypass operation, one that would achieve the same objective as the proposed large-scale Kavieng assault, but at much less cost. The admiral argued vigorously for his point of view at Pearl Harbor in late December, and in Washington in January, during a short leave he spent in the States.3

Although General MacArthur indicated on 20 December that the possession of airfields at either Kavieng or Emirau would accomplish his mission of choking off access to Rabaul4 he was soon firm again in his belief that the New Ireland base would have to be captured. This was the stand that SWPA representatives took at a coordinating conference held on 27 January

at Pearl Harbor, where preparations went ahead for a simultaneous assault on Kavieng and the Admiralties. The new tentative target date was 1 April, a month and a half after SoPac forces were slated to secure the Green Islands.

Green and Admiralty Island Landings5

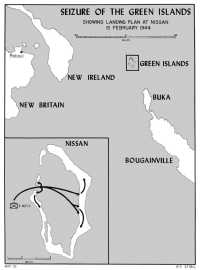

Before the Green Islands was chosen as the next SoPac objective after Bougainville, several other prospective targets were considered and rejected. A proposal to seize a foothold in the Tanga Islands, 35 miles east of New Ireland, was turned down because the operation could not be effectively covered by land-based fighters. Similarly, the capture of enemy airstrips at Borpop or Namatami was discarded because carrier support as well as a large landing force, would be required to handle Japanese resistance.6 Nissan, the largest of the Green Islands, was not only close enough to Torokina for AirSols fighter support, but also was weakly defended. (See Map 32.)

Located 37 miles northwest of Buka and 55 miles east of New Ireland, Nissan is an oval-shaped atoll 8 miles long with room on its narrow, flat main island for a couple of air strips. With Rabaul only 115 miles away and Kavieng about a hundred miles farther off, the Allied objective was clearly vulnerable to enemy counterattack once it was taken. By 15 February, however, the swing of fortune against the Japanese made that risk readily acceptable. In fact, Admiral Halsey reported that the campaign to neutralize Rabaul’s air strength “had succeeded beyond our fondest hopes.”7

Although aerial photographs and the scanty terrain intelligence available regarding the Green Islands indicated that Nissan was suitable for airfield development, nothing sure was known. A 24-hour reconnaissance in force, to be launched close enough to D-Day to prevent undue warning and consequent reinforcement of the garrison, was decided upon to obtain detailed information. New Zealand infantrymen of the 30th Battalion made up the main body of the 330-man scouting party; they were reinforced by American Navy specialists who would conduct the necessary harbor, beach, and airfield surveys.

The landing force loaded on board APDs at Vella Lavella at midday on 29 January, rehearsed the operation that evening, and got underway for the target at dawn. Escorted and screened by destroyers, the high-speed transports hove to off Nissan just after midnight and started debarking troops immediately The column of LCVPs was led into the atoll lagoon by two PT boats that had sounded a clear passage during a previous reconnaissance mission. By 0100, all troops were ashore near the proposed airfield site;

Map 32: Seizure of the Green Island, Showing Landing Plan at Nissan, 15 February 1944

there was no sign of enemy opposition. Once it was obvious that the landing was safely effected, the transports and escorts shoved off for the Treasurys in order to be well away from Nissan by daylight.

The atoll reconnaissance started when dawn broke, and the findings were very encouraging. Preliminary estimates that Nissan could accommodate a fair-sized airbase and that its lagoon and beaches could handle landing ships proved accurate, and, despite evidence that about 100 Japanese occupied the islands, there was only one clash with the defenders. In an exchange of fire with a well-hidden machine gun, an LCVP-borne scouting party lost three men and had seven others wounded. Showing that Rabaul was well aware of the raid, seven Zekes appeared during the afternoon to strafe and bomb the landing craft; one sailor was killed and two were wounded.

Right on schedule, at 0010 on 1 February, the APDs and their escorts arrived in the transport area off Nissan. After breasting a choppy sea, the landing craft and the troops were all back on board ship by 0145. On the return voyage, the escorts added a bonus prize to the successful mission when the destroyers Guest and Hudson sank a Japanese submarine, the I-171, with a barrage of depth charges.

Since the reconnaissance of Nissan confirmed earlier estimates of its value as an objective, Admiral Halsey’s operation plan for its capture, issued on 24 January, went unchanged. Admiral Wilkinson, as Commander Task Force 31, was directed to seize the Green Islands using Major General H. E. Barrowclough’s 3rd New Zealand Division (less the 8th Brigade) as the landing force. ComAirSols would provide reconnaissance and air cover, and as in previous SoPac operations, a commander and staff to control air activities at the objective. Brigadier General Field Harris, well experienced in this type of assignment after similar service at Bougainville, was designated ComAirGreen. To cover the landings, two cruiser-destroyer task forces would range the waters north, east, and south of the islands, while a tightly echeloned procession of APDs, LCIs, and LSTs ran in toward the target from the west, unloaded, and got clear as soon as possible. The possibility of a Japanese surface attack could not be discounted with Truk presumably still the main Combined Fleet base, and an aerial counterattack from Rabaul and Kavieng was not only possible but probable.

The pending assault did not catch the Japanese unawares, but the incessant AirSols strikes on Eleventh Air Fleet bases at Rabaul, coupled with RAAF and Fifth Air Force attacks on Kavieng, gave the enemy no chance for effective countermeasures. The original garrison of the Green Islands, 12 naval lookouts and 60 soldiers who operated a barge relay station, fled to the nearby Feni Islands on 1 February after briefly engaging the Allied reconnaissance force. About a third of these men returned to Nissan on the 5th to reinforce a small naval guard detachment that had been sent by submarine from Rabaul after word of the Allied landing was received. The combined garrison stood at 102 men on 14 February, when Japanese scout planes reported that a large convoy of transports, screened by cruisers and destroyers, was headed north from the waters off Bougainville’s west coast.

Japanese aircraft harassed the oncoming ships throughout the moonlit night approach, but managed to score on only

one target, the light cruiser St. Louis, which steamed on despite damage and casualties from one bomb hit and three near misses. The amphibious shipping reached its destination unscathed, and, at 0620, the first wave of New Zealander assault troops from the APDs was boated on the line of departure. In order to spare the atoll’s natives, there was no preliminary or covering fire as the LCVPs raced shoreward. AirSols planes were overhead, however, ready to pounce on any Japanese resistance that showed, destroyers had their guns trained ashore, and LCI gunboats shepherded the landing craft to the beaches.

All landings were unopposed, the first at 0655 on small islets at the entrance to the lagoon and those immediately following which were made near the prospective airfield site. About 15 Japanese dive bombers attempted to hit the transports at about this time, but a fury of antiaircraft fire from every available gun caused them to sheer off after some ineffectual bombing. The AirSols combat air patrol, all from VMF-212, claimed six of the attacking planes; the Japanese admitted losses of four Bettys, two Kates, six Vals, and a Rufe during both the night heckling and the unsuccessful thrust at the landing ships.

The New Zealanders sent patrols out as soon as the landing force was firmly set up ashore, but these encountered only slight resistance. The operation proceeded smoothly and without encountering any unforeseen snags. As soon as the APDs discharged the assault troops, they picked up an escort and headed south, while 12 LCIs beached on Nissan and quickly unloaded. At 0835, an hour before the LCIs left, 7 LSTs, each loaded with 500 tons of vehicles and bulk cargo, entered and crossed the lagoon and nosed into shore. When the LSTs retired at 1730, Admiral Wilkinson in his flagship and the remainder of TF 31’s ships accompanied them, leaving behind 6 LCTs to serve the budding base.

On D-Day, 5,800 men had been landed—to stay. Although there were almost 100,000 Japanese troops located close by on the Gazelle Peninsula and New Ireland, they were held at bay by superior Allied air and naval strength. The situation of the Japanese units located south of the newest SoPac outpost was “hopeless” in General MacArthur’s view, and he reported to the JCS that the successful landing “rings the curtain down on [the] Solomons campaign.”8

Despite the overwhelming odds against them, the defenders of Nissan Atoll fought tenaciously against the New Zealanders, killing 10 and wounding 21 of the 3rd Division’s men in 5 days of mopping-up action.9 The last pocket of resistance was not wiped out until the 19th when the Japanese remnant sent Admiral Kusaka the message: “We are charging the enemy and beginning radio silence.”10

What little help Rabaul could offer its doomed outguard on Nissan was confined to night bombing, and even that proved costly and futile for the Japanese. The attacking planes lost three of their number to VMF(N)-531 Venturas vectored to their targets by one of the squadron’s GCI teams. Even the nuisance value of night raiders was lost when the Combined Fleet ordered all flyable aircraft out of Rabaul

on the 19th. With the departure of defending Zekes, the New Britain base lay wide open to AirSols attack, particularly to strikes that could be mounted or staged from fields in the Green Islands. Even more important, Kavieng, where the Japanese still had some planes, was within easy reach of fighters and light bombers dispatched by ComAirGreen.

Seabee units outdid themselves and surpassed all base development goals. The fighter field was able to handle its first emergency landing on 4 March, the date on which Admiral Wilkinson passed command of the Green Islands to General Barrowclough. Three days later, AirSols fighters staged through Green, as Nissan was usually called, to attack Kavieng. Completion of the bomber field was scheduled for 1 April, but the first group of light bombers, 36 SBDs and 24 TBFs from Piva, was able to stage for a strike and hit Kavieng on 16 March. On the 19th, VMSB-243, VMTB-134, and part of VB-98 were detached from Strike Command, Piva and shifted to Green and General Harris’ command.

The light bombers did not get to settle in at their home field for a while though, but shared instead the fighter strip with the Corsairs of VMF-114 and -212. The Thirteenth Air Force preempted the bomber field when its B-24s landed on Green en route to strikes on Truk. Until hardstands for the Liberators were completed on 15 April, the Marine and Navy bombers competed with Seabee construction equipment for room. “Frequently trucks hauling coral would be sandwiched between sections of planes taxiing and often [an] entire strike [group] would inch by fighters parked along the ends of the taxiway. Each TBF would have to taxi with folded wings and unfold them only when in position along the strip.”11

The temporary crowding served a useful purpose, however; it made maximum use of Green’s airfields at a time when many of the missions flown by AirSols planes helped isolate the newest Bismarck’s battleground, the Admiralties. The seizure of these islands, 200 miles from Wewak and 260 miles from Kavieng, snapped the last link between General Imamura and his Eighth Area Army troops fighting on New Guinea.

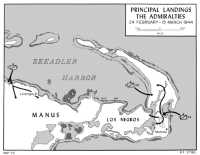

In terms of their eventual usefulness, the Admiralties far outshone any other strategic objective that was seized during the operations against Rabaul. Seeadler Harbor, contained in the hook-like embrace of the two main islands, Manus and Los Negros, is, if anything, as fine as Rabaul’s harbor and well able to handle warships and auxiliaries of all sizes. In 1942, at Lorengau village on Manus, the largest island, the Japanese had built an airfield and followed up in 1943 by constructing another at Momote Plantation on Los Negros. Both fields were used as staging points for traffic between Rabaul and New Guinea. (See Map 33.)

When Allied advances on the Huon Peninsula and in the Solomons threatened the Bismarcks area, Admiral Kusaka and General Imamura both ordered more of their troops into the Admiralties. A naval garrison unit from New Ireland was able to get through to Lorengau in early December, but ships carrying Army reinforcements from Japan and the Palaus were either sunk by American submarines or turned back by the threat of their torpedoes. In late January, Imamura dispatched one infantry battalion from

Seabee equipment is unloaded from an LST at Nissan Island on D-Day of the Green Islands operation. (USMC 77990)

First wave ashore on Los Negros, troopers of the 1st Cavalry Division, advance toward Momote airfield. (SC 187412)

Kavieng and another from Rabaul on board destroyers that reached Seeadler despite harassment by Allied aircraft. These soldiers, together with those of a transport regiment and the naval contingent already present, made up a formidable defense force of about 4,400 men.

Realizing that he was charged with defending a prize that the Allies could ill afford to ignore, the Japanese commander in the Admiralties decided that deception was one of his most effective weapons. When General Kenney’s planes attacked Lorengau and Momote airfields, the enemy leader ordered his men not to fire back. He told them, in fact, not to show themselves at all in daylight. His ruse had the desired effect; reconnaissance planes could spot few traces of enemy activity. On 23 February, three B-25s “cruised over Manus and Los Negros for ninety minutes at minimum altitude without having a shot fired at them or seeing any signs of activity either on the airdromes or along the beaches.”12 To American Generals Kenney and Whitehead, the situation seemed ripe for a reconnaissance in force, one that might open the way for an early occupation of the Admiralties and the consequent upgrading of the target dates for all later operations.

General MacArthur, impressed by the promise of a quick seizure of an important objective, accepted General Kenney’s proposal that a small force carried on destroyers and APDs land on Los Negros and seize Momote airfield, repair it, and hold it ready for reinforcement by air if it proved necessary. In case Japanese resistance proved too stiff, the reconnaissance force could be withdrawn by sea. If, on the other hand, the enemy garrison was weak, the original landing force would be strong enough to hold its own and open the way for reinforcing echelons.

Acting on General MacArthur’s orders, issued on 24 February, the 1st Cavalry Division (Major General Innis P. Swift) organized a task force of about 1,000 men, most of them from its 1st Brigade, to make the initial landing. If all went well, follow-up echelons would bring in more cavalrymen plus Seabees and other supporting troops to mop up the Japanese and begin base construction. Commanding the reconnaissance force, its backbone the 2nd Squadron, 5th Cavalry, was Brigadier General William C. Chase. The SWPA’s veteran amphibious force commander, Admiral Barbey, was responsible for the conduct of the operation. General MacArthur decided that both he and Admiral Kinkaid would accompany the attack group that transported Chase’s troops in order to evaluate at first hand the results of the reconnaissance.

On 27 February, two days before D-Day, a small party of ALAMO scouts landed on Los Negros about a mile south of Momote; they reported the jungle there to be a bivouac area alive with enemy troops. The scouts’ finding was too inconclusive to bring about any change in the size of Chase’s force, but the information did result in the detail of a cruiser and two destroyers to blanket the bivouac area with naval gunfire when the landing was attempted. The rest of the covering force, another cruiser and two more destroyers, was assigned Lorengau and Seeadler Harbor as an area of coverage. Nine destroyers of the attack group, each transporting about 57 troopers, were assigned fire support areas which would directly

cover the landing attempt. Three APDs, each with 170 men on board, would land the first three waves of assault troops.

The chosen landing area, a beach near the airfield, could be reached only through a 50-yard-wide opening in the fringing reef that closed the narrow entrance to a small harbor on the eastern shore of Los Negros. The site seemed so improbable for a landing that the Japanese concentrated most of their strength to meet an attack from the Seeadler Harbor side of the island.

On 27 February, the 1st Cavalry Division troops boarded ship at Oro Bay, and the attack group moved out to rendezvous with its escort off Cape Sudest. Through a heavy overcast on the morning of the 29th, the American ships approached the Admiralties and deployed to bombardment and debarkation stations off the coast of Los Negros. At 0728, three B-24s bombed Momote, but poor visibility cancelled out most of the rest of the preparatory air strikes. Cruisers and destroyers began shelling the island at 0740 and continued firing as the troops in LCVPs crossed the line of departure, 3,700 yards out, and headed for the beach. Fifteen minutes later, as the first wave passed through the harbor channel, enemy machine guns on the headlands opened fire on the boats while heavier guns took on the cruisers and destroyers. Counterbattery fire was prompt and effective; the Japanese guns fell silent. At 0810, a star shell fired from the cruiser Phoenix signalled the end of naval gunfire and brought in three B-25s, all that had reached the target in the foul flying weather, to strafe and bomb the gun positions on the headlands.

The first troops were on the beach at 0817 and moving inland; the few Japanese defenders in the vicinity pulled back in precipitous haste. Enemy gun crews manning the weapons interdicting the entrance channel began firing again when naval gunfire lifted. Destroyers pounded the gun positions immediately and drove the crews to cover, a pattern of action that was repeated throughout the morning. The American landings continued despite the Japanese fire, and by 1250, General Chase’s entire command had landed. The cost of the operation thus far was two soldiers killed and three wounded, a toll doubled by casualties among the LCVP crews. Five enemy dead were counted.

The cavalrymen advanced across the airfield during the afternoon, but pulled back to man a tight 1,500-yard-long perimeter anchored on the beach for night defense. General MacArthur and Admiral Kinkaid went ashore about 1600, conferred with General Chase, and heard the reports that the cavalrymen had run across signs of a considerable number of enemy troops. After assessing the available intelligence, and viewing the situation personally, the SWPA commander ordered General Chase to stay put and hold his position at the airfield’s eastern edge. As soon as the senior commanders were back on board ship, orders were dispatched to send up more troops and supplies to reinforce the embattled soldiers. Two destroyers remained offshore to furnish call-fire support when the rest of the task group departed at 1729.

The first of the counterattacks that the cavalrymen expected, and had prepared for as best they could with their limited means, came that night. The Japanese on Los Negros, who outnumbered the Americans

handily, did not take advantage of their strength and made no headway in a series of small-scale attacks that sometimes penetrated the perimeter but never seriously threatened the integrity of the position. With daylight, American patrols pushed out from their lines until they ran into heavy enemy resistance, then pulled back to let the destroyers and the force’s two 75-mm howitzers fire on the Japanese. Aircraft made nine supply drops for the cavalrymen during the day, and, toward evening, Fifth Air Force planes bombed the enemy positions, despite the ineffectual attacks of several Japanese Army fighters which showed up from Wewak. There was an unsuccessful assault on the cavalrymen’s lines at dusk, and another night of infiltration attempts that ended with a two-day count of 147 Japanese dead within American lines.

By dawn of 2 March, the Japanese had lost their chance to drive out the reconnaissance force, for the first reinforcement echelon, 1,500 more troopers and 428 Seabees, stood offshore. An American destroyer and two minesweepers of the landing ship escort attempted to force the entrance of Seeadler Harbor, but uncovered a hornet’s nest of coast defense guns which forced them to sheer off. Warned away from Seeadler for the time being, the amphibious craft landed their troops and cargo on the beaches guarded by Chase’s men.

Once the fresh troops were ashore, General Chase attacked and seized the airfield against surprisingly light resistance. There was ample evidence, however, that the Japanese were readying an all-out attack. It came on the night of 3-4 March, a night of furious fighting that saw 61 Americans killed and 244 wounded, with 9 of the dead and 38 of the wounded Seabees, who backed up the cavalry’s lines. At the focal point of the attack, 167 enemy soldiers fell; hundreds more fell all along the perimeter.

The remainder of the 1st Cavalry Division joined its advance forces in the Admiralties during the following week. The Japanese on Los Negros were either killed or driven in retreat to Manus. Air and ship bombardment eliminated the enemy guns that had shielded the Seeadler entrance, and on 9 March, the 2nd Cavalry Brigade entered the harbor and landed on Los Negros. The cavalry division commander, General Swift, now planned the seizure of Lorengau airdrome and the capture of Manus.

On 15 March, following a series of actions that cleared the small islands fringing the harbor of the enemy, the 2nd Brigade landed on Manus and fought its way to the airfield. Even though the main objective was quickly secured, the big island was far from won. It was two months before the combat phase of the operation was ended and the last organized resistance in the Admiralties faded. The count of Japanese dead reached 3,280, 75 men were captured, and another 1,100 were estimated to have died and been buried by their own comrades. The 1st Cavalry Division lost 326 troopers and had 1,189 of its men wounded in the protracted and bitter fighting.

While the battle raged, the naval construction battalions and the Army engineers turned to on the airfields and naval base projected for the islands. Momote was operational by 7 March, and, on the 9th, a squadron of Australian Kittyhawks from Kiriwina moved in as part of the garrison. The RAAF planes, soon reinforced, flew cover for B-25 bombers at first and then began to fly bombing and

Map 33: Principal Landings in the Admiralties, 24 February–15 March 1944

strafing strikes of their own in support of the cavalrymen’s offensive. On 16 March, the Australian squadrons were given the primary mission of protecting all Allied shipping in the vicinity of the Admiralties.13

When Lorengau airfield proved unsuitable for extensive development, the engineers and Seabees shifted their tools and machines to Mokerang Plantation on Los Negros, about 7,000 yards northwest of Momote on the Seeadler shore. The new field was operational by 21 April. The naval base, including two landing strips for carrier aircraft on outlying islands, flourished. Manus, as the whole base complex was generally known, grew to be as important in staging and supporting Allied operations during 1944 as Guadalcanal had been in 1943 and Espiritu Santo in 1942.

Emirau: The Last Link14

At one time in the planning for the operations that would follow Bougainville and Cape Gloucester, General MacArthur and his staff had considered it necessary to make a landing at Hansa Bay between the Japanese Eighteenth Army’s bases at Madang and Wewak. The early and successful move into the Admiralties, from which planes could easily interdict both enemy positions, crystallized opinion against the Hansa Bay venture. In its stead, on 5 March, MacArthur proposed to the JCS that he completely bypass the Madang-Wewak area and take a long step forward in his advance toward the Philippines by seizing Hollandia in Netherlands New Guinea. In the same message, the general reaffirmed his conviction that Kavieng had to be taken to insure the complete neutralization of Rabaul.

In Washington, where the need for taking Kavieng had been seriously questioned, considerable weight was obviously given to Admiral Halsey’s opinion, voiced in person in January, that “the geography of the area begged for another bypass,”15 and that:

... the seizure of an airfield site in the vicinity of the St. Matthias Group appeared to be a quick, cheap operation which would insure the complete neutralization of Kavieng and complete the isolation of Rabaul and the Bismarcks in general. Furthermore, the Carolines would be brought just that much nearer as a target for our own aerial operation.16

The fact that Admiral Nimitz joined in recommending that the Kavieng operation be dropped in favor of the much less expensive seizure of Emirau may have been decisive.

On 12 March, the JCS issued a new directive for future operations in the Pacific, cancelling Kavieng and Hansa Bay and ordering the capture of Hollandia and Emirau, the latter as soon as possible. General MacArthur immediately issued

orders halting preparations for the Kavieng attack, then only 18 days away, and directed Admiral Halsey to seize Emirau instead, using a minimum of ground combat forces. In his turn, ComSoPac ordered his amphibious force commander, Admiral Wilkinson, to take the new objective by 20 March and recommended that the 4th Marines be used as the landing force. The message from Halsey at Noumea to Wilkinson at Guadalcanal was received early on the morning of 15 March when loading had already started for Kavieng.

The I Marine Amphibious Corps, composed of the 3rd Marine Division and 40th Infantry Division, had been the chosen landing force for Kavieng. For that operation, the 3rd Division was reinforced by the 4th Marines, and the regiment was ready to load out when word was received of the change in plans. Fortunately, the headquarters of III Amphibious Force, IMAC, the 4th Marines, and the transport group which was to carry the troops to the target were close together and planning got underway immediately. General Geiger noted that the several staffs “had only about six or eight hours to work up the Emirau plans”17 that had resulted from Admiral Halsey’s earlier interest in the island as a SoPac objective. Late in the afternoon of the 15th, the admiral flew in to Guadalcanal from New Caledonia and quickly approved the concept of operations that had been developed.

Commodore Lawrence F. Reifsnider was to command the amphibious operation, with Brigadier General Alfred H. Noble, ADC of the 3rd Marine Division, in command of the landing force. General Noble, who was also slated to become the island’s first commander, had a small staff made up of IMAC and 3rd Division personnel. An air command unit for Emirau, under Marine Colonel William L. McKittrick, was formed from the larger headquarters that had been organized to control air operations at Kavieng.

The 4th Marines, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Alan Shapley, was the newly formed successor to the regiment captured on Corregidor.18 It was activated on 1 February from former raider units, after the Commandant decided there was no longer enough need to justify the existence of battalions specially raised for hit-and-run tactics.19 On the 22nd, the Commandant directed General Geiger to reinforce the regiment by the addition of a pack howitzer battalion, engineer, medical, tank, and motor transport companies, and reconnaissance, ordnance, war dog, and service and supply platoons. Only the tank and medical companies had been added by the date the regiment sailed for Emirau. For the landing operation, the 3rd Division provided amphibian tractor and pioneer companies and motor transport and ordnance platoons; the 14th Defense Battalion furnished a composite automatic weapons battery.

The pace of preparations for Emirau was so swift that it put a temporary crimp

Map 34: Kavieng and Emirau

in JCS plans for the employment of the Marines released by the cancellation of Kavieng. On 14 March, MacArthur received and passed on to Halsey for compliance, a JCS directive that the 3rd Marine Division, the 4th Marines, and the 9th and 14th Defense Battalions were to be released to the control of CinCPOA immediately. By the time the admiral received this order, it was too late to replace the 4th Marines and still meet Emirau’s D-Day of 20 March; some platoons of the 14th Defense Battalion were already on board ship. Consequently, ComSoPac outlined the situation to Admiral Nimitz and promised to release all units required for future operations as soon as possible. In view of the circumstances, Admiral Nimitz concurred in the temporary transfer of troops for use at Emirau.

The target for the operation is an irregularly shaped island eight miles long, hilly and heavily wooded. It lies in the southeastern portion of the St. Matthias Group, about 25 miles from Massau, the other principal island. Situated 90 miles northwest of Kavieng, Emirau was considered suitable for development as a base for fighters, bombers, and torpedo boats. All intelligence indicated that the Japanese had not occupied the islands in any appreciable strength, and a photo reconnaissance mission flown by VD-1 on 16 March revealed no trace of enemy activity or installations. (See Map 34.)

Even though little opposition was expected, detailed provisions for strong air and naval gunfire support were a part of the Emirau operation plan. The naval bombardment group that was to have shelled Kavieng under the cancelled plan was ordered to hit the town and its airfields anyway as insurance against interference from the enemy. While it was anticipated that there would be no need for preliminary bombardment of Emirau before the landing, two destroyers of the escort were prepared to deliver call fire, and planes from two supporting escort carriers were to be overhead, ready to strafe and bomb as necessary. The cruisers and other destroyers of the escort would take station to screen the landing. Should a Japanese surface threat materialize, the 4 battleships and 15 destroyers pounding Kavieng on D-Day would be available as a weighty back-up power. On Green, planes of VMSB-243, VMTB-134, and VB-98 were on standby for possible employment, reinforcing the carrier planes.

The formidable support preparations for Emirau made the unopposed amphibious operation seem anticlimactic. The loading, movement, and landing of General Noble’s force was conducted in an aura of orderly haste. New shipping assignments, necessitated by the change in plans, forced the 4th Marines to sort and redistribute all the supplies in its beach-side dumps during the night of 15 March. Loading began the next morning and continued through the 17th when the troops went on board ship, and Commodore Reifsnider’s attack group sailed from Guadalcanal.

The ships left in two echelons, grouped by cruising speed and destined to rendezvous on D minus 1. The Marines of the two assault battalions, 1/4 and 2/4, were on board nine APDs; the remainder of the landing force traveled to the target on three LSDs and an APA. One LSD transported the 66 LVTs that would land the assault waves over Emirau’s fringing reef, another carried three LCTs, two of them loaded with tanks, and the third had three

LCTs on board bearing radar and antiaircraft guns.

At 0605 on 20 March, the attack group arrived in the transport area, the LSD launched her LVTs, and the assault troops transferred to the tractors using the APDs’ boats which were supplemented by those from the APA. Then, as the men of the reserve battalion, 3/4, scrambled down the nets into boats to be ready for employment wherever needed, Corsairs of VMF-218 flashed by overhead to make a last minute check of the island for signs of the Japanese. Right on schedule, the assault waves crossed the island’s encircling reef and went ashore on two beaches about 1,000 yards apart near the eastern end of the island, while a detachment of 2/4 secured a small islet that sheltered the easternmost beach. Soon after the assault troops landed, the 3rd Battalion’s boats grounded on the reef, and the reserve waded ashore through knee-deep water. During these landings, a few shots were fired in return to supposed enemy opposition, but subsequent investigation showed that there were no Japanese on the island.

Had there been opposition, one hitch in the landing plan could have been fateful. The tanks were not launched in time for the assault, since their LSD’s flooding mechanism was only partially operative. A fleet tug with the escort was able to drag the loaded LCTs out through the stern gate by means of a towline. Although by this time the success of landing was assured, the tanks were run ashore anyway both as insurance and for training.

Supplies began coming in about 1100, first from the APDs and then from the APA, with the LCTs helping the ships’ boats to unload. By nightfall, 844 tons of bulk cargo had been landed in addition to the weapons and equipment that went ashore in the assault. All the ships sailed just after sunset, leaving General Noble’s force of 3,727 men to hold the island and prepare for follow-up echelons.

Emirau’s natives told the Marines that only a handful of Japanese had been on the island, and they had left about two months before the landing. Intelligence indicated that there were enemy fuel and ration dumps on Massau and a radio station on a nearby island. On 23 March, destroyers shelled the areas where the reported installations lay and, according to later native reports, succeeded in damaging the dumps and radio enough to cause the Japanese to finish the job and try to escape to Kavieng. On the 27th, a destroyer intercepted a large canoe carrying enemy troops about 40 miles south of Massau; the Japanese opened up with rifles and machine guns, and the ship’s return fire destroyed them all. This episode furnished the last and only vestige of enemy resistance in the St. Matthias Group.

The first supply echelon reached Emirau on 25 March, bringing with it the men and equipment of a battalion of the 25th Naval Construction Regiment. The Seabees and the supplies landed over beaches and dumps that had been prepared by the 4th Marines. Five days later, three more naval construction battalions arrived to turn to on the air base and light naval facilities. An MTB squadron began patrolling on the 26th while its base was being readied. Sites for two 7,000-foot bomber strips and a field 5,000-feet-long for fighters were located and surveyed before the month’s end. On 31 March, heavy construction on the airfields began.

In view of the island’s projected role as an important air base, General Noble’s relief as island commander was a naval aviator,

Major General James T. Moore, who had been Commanding General, 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, since 1 February. General Moore, with advance elements of the wing headquarters squadron, arrived on Emirau on 7 April, following by two days the forward echelon of MAG-12. Relief for the 4th Marines by the island’s garrison, the 147th Infantry Regiment, took place on 11 April, and the Marines left on the same ships that brought the Army unit. At noon on the 12th, acting on Admiral Wilkinson’s orders as operation commander, General Moore formally assumed command of all ground forces on Emirau.

Throughout April, airfield construction continued at a steady but rapid tempo in order to ready the island for full use in the interdiction of Japan’s Bismarcks bases. The first emergency landing was made on the 14th when a Navy fighter came down on one of the bomber strips. On the 29th, SCAT transports began operating regularly from the new fields, and, on the 2nd of May, the first squadron of the MAG-12 garrison, VMF-115, arrived and sent up its initial combat air patrol. In the next two weeks, several more Marine fighter, dive, and torpedo bomber squadrons moved up from Bougainville and Green. By mid-May, Emirau was an operating partner in the ring of SWPA and AirSols bases that throttled Rabaul and Kavieng.

The Milk Runs Begin20

The prime target at the hub of the encircling Allied airfields, Rabaul, had no respite from attack even while the SWPA forces were seizing the Admiralties and SoPac troops were securing Emirau. If anything, the aerial offensive against the enemy base intensified, since the absence of interceptors permitted both a systematic program of destruction and the employment of fighters as bombers.

First on the list of objectives to be eliminated was Rabaul proper. The town was divided into 14 target areas which, in turn, were further subdivided into two or three parts; each was methodically wiped out. Two weeks after the opening attack of 28 February, the center of the town was gutted, and most strikes, thereafter, were aimed at more widely spaced structures on the outskirts. By 20 April, only 122 of the 1,400 buildings that had once comprised Rabaul were still standing and these were “so scattered that it was no longer a paying proposition to try to make it a 100 percent job.”21

Weeks before the AirSols staff reached this conclusion, the task of reducing the town to rubble and charred timbers was left pretty much to the fighter-bombers, while the B-24s, B-25s, SBDs, and TBFs concentrated on the two largest enemy supply dumps, one about two miles west of Rapopo and the other on the peninsula’s north coast three miles west of Rabaul. Bomber pilots found that

500-pound bombs containing clusters of 128 smaller incendiary bombs were more effective than high explosive in laying waste to these sprawling areas of storage tents, sheds, and ammunition piles.

Over the course of three months, during which the major destruction of above-ground installations was accomplished, an average of 85 tons of bombs a day was dropped on Rabaul targets. The attack was a team effort, done in part by all the plane types assigned to AirSols command. The two Liberator groups of the Thirteenth Air Force provided a normal daily effort of 24 planes until 23 March, when all heavy bombers were diverted to attacks on Truk and other targets in the Carolines. The Thirteenth’s B-25 group also sent up an average of 24 planes a day. The strength of Marine and Navy light bombers varied during the period, but generally there were three SBD and three TBF squadrons at Piva and three SBD and one TBF squadron at Green; in all about 160-170 planes were available, with a third to a half that number in daily use. Even when the Japanese attacked the Torokina perimeter in March, and much of the air support of the defending Army troops was furnished by Piva-based light bombers, there was little letup in the relentless attack on Rabaul. The SBD-TBF squadrons at Green increased their efforts, which were supplemented daily by the attacks of 48-60 fighters equipped to operate as bombers.

Once the Zekes disappeared from the sky over the Bismarcks, AirSols had a surplus of fighter planes. Consequently, all Army P-38s, P-39s, and P-40s, and RNZAF P-40s, were fitted with bomb racks, after which they began making regular bombing attacks. At first, the usual loading was one 500-pound bomb for the Airacobras, Warhawks, and Kittyhawks and two for the Lightnings, but before long, the single-engine planes were frequently carrying one half-ton bomb apiece and the P-38s, two. Except for some bombing trial runs by Corsairs against targets on New Ireland, AirSols, Navy and Marine fighters in this period confined their attacks on ground targets to strafing runs. Later in the year, all fighter aircraft habitually carried bombs.22

The pattern of attacks was truly “clock-round,” giving the enemy no rest, with the nighttime segment of heckling raids dominated by Mitchells. Army B-25s drew the job at first, but with the entry into action of VMB-413 in mid-March, the task gradually was given over to Marine PBJs. The Marine squadron, the first of five equipped with Mitchells to serve in the South and Southwest Pacific, proved particularly adept at night operations as well as the more normal daylight raids. General Matheny, the veteran bomber commander, specially commended the unit for its development of “the dangerous, tiresome mission of night heckling against the enemy bases to the highest perfection it has attained in the fourteen months I have been working under ComAirSols.”23

The object of the heckling missions was to have at least one plane over the target all night long. For the enemy troops below, the routine that was developed must

Town of Rabaul shows the effect of area saturation bombing in this photograph taken from a Navy SBD during an attack on 22 March 1944. (USN 80-G-220342)

Corsairs at Emirau in position along the taxiway to the new airfield which was operational less than two months after the landing. (USMC 81362)

have been nerve-wracking. At dusk, the first PBJ:

... appeared over Rabaul just as the Japanese began their evening meal. It dropped several bombs and retired. Minutes later, it came in again, hundreds of feet lower. More bombs dropped and it circled away. This pattern was repeated until, on its last run, the plane strafed the area.

As the sound of its motor died away, the Japanese heard the second plane coming in on schedule to repeat the maddening process which went on night after night.24

The enemy troops that were subjected to the mass air raids of spring 1944 were surprisingly better off than aerial observers could tell. Spurred on by the punishing attacks which scored heavily against major targets, the Japanese dispersed a substantial portion of their supplies out of sight under cover of the jungle. Even more significant was the fact that every man not bedridden or wounded labored to dig caves and tunnels to shelter the troops and matériel needed to fight should the Rabaul area be invaded. By the end of May, enough supplies were underground to insure that the Japanese could make a prolonged defense. The digging-in process kept up until the end of the war, making Rabaul a fortress in fact as well as name.

The responsibility for the defense of the Rabaul area was a dual one, with Japanese Army and Navy troops holding separate sectors. The battered town and the mountainous peninsula east of it, from Praed Point to the northern cape, was defended by elements of the Southeast Area Fleet. Other naval troops, primarily antiaircraft artillery and air base units converted to infantry, held positions in the vicinity of Vunakanau and Tobera airfields. Eighth Area Army defended the rest of Gazelle Peninsula north of the Keravat and Warangoi Rivers. General Imamura, deeply imbued with the offensive spirit of Japanese military tradition, prepared battle plans which would meet an invasion attempt, wherever it occurred, with vigorous counterattacks. If all else failed, he felt that “the members of the whole army should commit the suicide attack.”25 Admiral Kusaka believed it was his primary duty to keep “his forces safe as long as possible and planned to hold on and destroy the enemy fighting strength”26 by a tenacious defense of the elaborate fortifications the Navy had constructed in the hills back of Rabaul. Despite the difference in philosophy of ultimate employment, however, officers and men of both services worked together well, readying themselves to meet an attack that never came.

The growing desperation of the Japanese position in the Bismarcks was borne home to General Imamura by an order which the area army’s assistant chief of staff characterized as “a cruel, heartless, unreasonable measure.”27 On 25 March, the units on New Guinea which had been under Imamura’s command, the Fourth Air and Eighteenth Armies, were transferred by Imperial General Headquarters to the control of the Second Area Army defending western New Guinea. Since by this time the only contact the Eighth Area Army had with its erstwhile troops was by radio, the transfer was a practical move,

however disheartening its effect may have been on the army staff at Rabaul. As if to soothe the sense of isolation and loss, Tokyo directed General Imamura to defend Rabaul as a foothold from which future offensive operations would be launched.

The emptiness of this promise of future Japanese offensives was emphasized by the changes Rabaul’s impotence wrought in the dispositions of Allied forces in the South and Southwest Pacific. From the start of the New Georgia operation, most of the combat troops, planes, and ships assigned to Admiral Halsey’s command had operated in the SWPA under General MacArthur’s strategic direction. On the 25th of March, the JCS issued a directive that outlined a redisposition of forces to take effect on 15 June, by which the bulk of SoPac strength was assigned to MacArthur’s operational control for the advance to the Philippines. CinCSWPA would get the Army’s XIV Corps Headquarters and Corps Troops, plus six infantry divisions. Added to the Seventh Fleet were 3 cruisers, 27 destroyers, 30 submarines, 18 destroyer escorts, an amphibious command ship, an attack transport, an attack cargo ship, 5 APDs, 40 LSTs, and 60 LCIs. The Thirteenth Air Force was also to be transferred, but with instructions that its squadrons would support Pacific Ocean Areas’ operations as required.

Marine ground forces in the South Pacific were assigned to Admiral Nimitz’ command, as CinCPOA, to take part in the Central Pacific drive. The majority of Marine air units, however, were detailed to the SWPA as the core strength of the aerial blockade of bypassed enemy positions in the Solomons and Bismarcks.

Under the assignment of forces first worked out by JCS planners, the Royal New Zealand Air Force units, which had played such an important role in the AirSols campaign against Rabaul, were relegated to the SoPac garrison. This decision was unacceptable to the New Zealand Government which wanted its forces to continue their active role in the Pacific fighting. The end result of representations by the New Zealand Minister in Washington was the allocation of seven squadrons—four fighter, two medium bomber, and one flying boat—to the SWPA and seven squadrons of the same types to the South Pacific. Since, by this time in 1944, all RNZAF units were either equipped or in the process of being equipped with U.S. Navy planes, an overriding factor in squadron assignment was the ease of maintenance and resupply in areas that would be manned primarily by U.S. Navy and Marine units. Under the plans developed, the deployment of the RNZAF to assigned SWPA bases, Bougainville, Los Negros, Emirau, and Green, would not be completed until late in the year.

Many of the units that officially became part of General MacArthur’s command in June were already under his operational control two months earlier. By mid-April, the 13th Air Task Group, comprising heavy bombers of the Thirteenth Air Force under Major General St. Clair Street, was operating against the Palaus and Carolines to protect the flank of the Hollandia task forces. One heavy bombardment group of Street’s command moved from Munda and Guadalcanal to Momote field on Los Negros on 20 April. The other group of the Thirteenth’s B-24s followed soon after, and both bombed enemy

bases that threatened MacArthur’s further moves up the New Guinea coast and Nimitz’ thrust into the Marianas.

Since he was to have a second American air force operating under his headquarters, General Kenney recommended and had approved the formation of a new command, Far East Air Forces (FEAF), whose principal components would be the Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces. In addition to heading FEAF, Kenney remained Commanding General, Allied Air Forces, and, as such, commanded all other air units assigned to the Southwest Pacific Area, including those that had been a part of AirSols.

On 15 June 1944, all military responsibility for the area and the Allied units west of 159° East Longitude and south of the Equator passed to General MacArthur. Coincident with this change, Admiral Halsey relinquished his command of the South Pacific Area to his deputy of eight months standing, Vice Admiral John H. Newton, and went to sea as Commander, Third Fleet. The AirSols units became part of a new organization, Aircraft, Northern Solomons, with an initial strength of 40 flying squadrons, 23 of them Marine. The seven Thirteenth Air Force squadrons that were included in AirNorSols were under orders to join FEAF, and eight of the Navy’s and RNZAF’s were headed for SoPac garrison duty.28

Reflecting the preponderance of Marine elements assigned to AirNorSols was the appointment of General Mitchell as its commander. Mitchell, who had turned over leadership of AirSols to the Army Air Forces’ Major General Hubert R. Harmon on 15 March,29 had shortly thereafter relieved Admiral Fitch as ComAirSoPac. Throughout this period, the Marine general continued to head MASP also, but with his assumption of duties as ComAirNorSols, he designated Brigadier General Claude A. Larkin to succeed him in the South Pacific command and preside over its dissolution. According to plans for the future employment of its component wings, the 1st in the Southwest and the 2nd in the Central Pacific, there was no longer any need for MASP. Completing the picture of Marine air command changes, General Mitchell took over the 1st Wing at the same time he became ComAirNorSols and established the headquarters of both organizations on Bougainville.

The command reorganization of 15 June 1944 marked the end of an important phase of the Pacific fighting, one which saw the onetime scene of violent battle action gradually become a staging and training center for combat on other fronts. In fitting tribute to the men who drove the Japanese back from the Solomons and Bismarcks, Admiral Halsey sent a characteristic farewell message to all ships and bases when he departed Noumea, saying “‘Well done’ to my victorious all-services South Pacific fighting team. You have met, measured, and mowed down the best the enemy had on land and sea and in the air.”30

The Mitchells Remain31

Controlling most of the strikes against Japanese targets when AirNorSols was activated was Fighter-Strike Command, headed by Colonel Frank H. Schwable. The title of this headquarters, the successor to AirSols Strike Command, reflected the shift in emphasis of fighter missions from air combat to strafing and bombing in company with SBDs and TBFs. The life of the new command was short, however, for General Mitchell abolished all separate type commands on 21 August when he centralized direction of tactical air operations under his own headquarters with Colonel Schwable as operations officer. Responsibility for controlling the aircraft assigned to various missions at each AirNorSols base remained with the area air commander who was also, in most cases, a Marine air group commander. Marines of the group headquarters doubled as members of the air commander’s staff, serving together with representatives of other Allied and American units flying from the particular base.

Logistic support of the AirNorSols squadrons, except for those in the Admiralties, was to be the responsibility of ComSoPac until December when agencies of the Seventh Fleet could take over. For Mitchell’s Marine units this function, once channeled through MASP, was made the responsibility of Marine Air Depot Squadron 1, which remained in the South Pacific to handle the 1st Wing’s personnel and supply needs. A similar role as a rear echelon for 2nd Wing units staging to Central Pacific bases was performed by MAG-11’s service squadron. All men and equipment that had been part of MASP were distributed to other units or returned to the States. General Larkin, who decommissioned MASP on 31 July, wrote its informal but apt epitaph in a letter to General Rowell at MAWPac:–

Certainly hate to see this command go under but it has outlived its usefulness, and it is always good news when units can be done away with rather than having to form new ones. At least it is an indication that we are doing okay with the war in this area by reducing and going forward.32

The inevitable result of the continuous Allied advance was that fields that had once bustled with combat air activity—at Noumea, Efate, Espiritu Santo, Guadalcanal, Banika, and Munda—were relegated to limited use or closed down. Newer, fully developed bases like Green and Emirau carried the burden of the attack against Rabaul and Kavieng, while most of the strikes aimed at the thousands of Japanese troops still active in the northern Solomons were mounted from the Piva fields. The more profitable enemy targets, however, those that could be reached only by heavy bombers and the few short-range planes that could crowd onto advanced airstrips, were hit less frequently than the bypassed positions. In July, as an example, SWPA land-based air forces flew over

8,000 sorties against targets in bypassed areas but only 3,000 against targets in the forward areas.33 There was a constant danger that bombing attacks against blockaded enemy forces would degenerate into what ComAirPac called “mere weight lifting,”34 an ineffective use of the air weapon, which was perhaps the most powerful available to Allied commanders.

General Kenney was well aware of the fact that some of his most effective aviation units, the veteran Marine squadrons, were tied down in the Solomons and Bismarcks. He intended to employ them in the seizure of Mindanao, and, to make the Marine units available, he determined to replace them with RNZAF and RAAF squadrons. In like manner, General MacArthur planned to relieve the American infantry divisions on Bougainville and New Britain with Australian troops. There was a strong current of opinion at MacArthur’s headquarters that further operations in British and Australian territories and mandates should be undertaken by Commonwealth forces. On 12 July, CinCSWPA confirmed this concept in a letter to the Australian commander, General Blamey, stating:

A redistribution of Allied forces in the SWPA is necessitated by the advance to the Philippine Islands. Exclusive of the Admiralties, it is desired that Australian forces assume the responsibility for the continued neutralization of the enemy in the Australian and British territory and mandates in the SWPA by the following dates:

Northern Solomons–Green Island–Emirau—1 Oct 44,

Australian New Guinea—1 Nov 44,

New Britain—1 Nov 4435

General Blamey ordered the Australian II Corps to relieve the American XIV Corps on Bougainville, the 40th Infantry Division on New Britain, and the garrisons on Emirau, Green, Stirling, and New Georgia. The 6th Australian Division was designated to replace the American XI Corps in eastern New Guinea. Not content with holding defensive perimeters, the Australians intended to seek out and destroy the Japanese wherever this would be done without jeopardizing Allied positions.

Since the Australians planned an active campaign with a limited number of troops—two brigades on New Britain and four on Bougainville—plentiful and effective close air support was a necessity. Some of it would be provided by RAAF reconnaissance and direct support aircraft operating under control of Australian ground force commanders, but most of the planes would come from ComAirNorSols. According to plans, a New Zealand Air Task Force under Group Captain Geoffrey N. Roberts, was to take over control of air operations from AirNorSols when the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing moved to the Philippines.

One big hitch in this plan for RNZAF replacement of the 1st Wing occurred when the first target in the American return to the Philippines was shifted northward from Mindanao to Leyte. This change cancelled the wing’s prospective employment, for, as General Kenney later explained: “... the movement forward of any air units in the Southwest Pacific depended upon the location of the unit under consideration, the availability of shipping, and the availability of airdromes

in the forward zone.”36 In the perennially tight shipping situation, the distance of the wing from the Philippines acted against its employment as a unit. As a consequence, the changeover date from AirNorSols to RNZAF command, originally projected for 1 November 1944, was repeatedly delayed and did not take place until 15 July 1945. In the interim, the 1st Wing’s operational strength was pared down to its transport and medium bomber groups; all fighter and dive bomber squadrons were transferred piecemeal to the Philippines.37

About 20 September, wing headquarters received the first word that its seven dive bomber squadrons would be employed in the Luzon campaign. For the most effective combat control, it was decided to employ two air groups, one of four squadrons and the other of three, and on 1 October, by transfers and joinings, MAG-24 became an all-SBD outfit (VMSB-133, -236, -241, and -341). A new Headquarters, MAG-32, was sent out from Hawaii to command the wing’s remaining Dauntless squadrons (VMSB-142, -224, and -243). Air intelligence officers with experience in close air support techniques as practiced in the Marshalls and Marianas reported from the Central Pacific to assist in training the SBD crews. General Mitchell issued a training directive which indicated that the dive bombers would “be employed almost exclusively as close support for Army ground forces in an advancing situation” and that their basic mission would “be largely confined to clearing obstacles immediately in front of friendly troops.”38 Army units worked closely with the Marine squadrons during the training to formulate realistic problems of troop support. Whenever Japanese antiaircraft concentrations were light, the SBD pilots practiced their air support techniques during the regular routine of strikes on enemy targets.

The monotonous pattern of attacks on the same targets, day after day, went on regardless of the pending deployment of various wing units. One virtue of the situation was that many Marine pilots and aircrewmen got their first taste of combat flying during these months of strikes against bypassed objectives. Once, whole squadrons had been sent back to the States after completing a combat tour, but now, only the individual veterans returned and the squadrons remained, kept up to strength by replacements. The flying, gunnery, and bombing experience gained while hitting Rabaul and Kavieng and tackling the Japanese positions in the northern Solomons was invaluable. Although combat and operational casualties were low, there was enough opposition from enemy gunners, enough danger from the treacherous weather, to make pilots handle any AirNorSols mission with prudence. The urge for more violent action was always present, however, and the flyers were cautioned repeatedly in orders against “jousting with A/A [antiaircraft] positions in any area at any time.”39

About the only variety that flyers had in what the 1st Wing’s history called a “deadly routine of combat air patrol, milk run bombing, and night heckling” was experimenting with new weapons and techniques.40 Incendiaries of different types were tested against Japanese installations, and bomb loadings were varied to measure destructive effect. This diversity brought no letup in the weight of the attack delivered against major enemy objectives until the end of the summer when, as the air operations commander at Piva noted, “practically all of the good targets in these areas had been destroyed.”41 As the Japanese went underground to find cover in the faceless jungle, the number of obvious targets steadily lessened, and many AirNorSols strikes blasted and burned area targets in a systematic destruction pattern much like that which leveled the town of Rabaul. Even the gardens that the Japanese troops planted to supplement their rations were sprayed with oil in hope that the crops would wither and die.

During September and October, one spectacular new air weapon, a drone bomb, was tested against Japanese targets in the AirNorSols area. The drones, specially built planes capable of carrying a 2,000-pound bomb, were radio controlled by torpedo bombers of a special naval test unit. Synchronized television screens in drone and control planes enabled the controllers to view what was ahead of the drones and to crash them against point targets. After test attacks on a ship hulk beached at Guadalcanal, the test unit moved up to Stirling and Green and made 47 sorties in conjunction with F4Us, SBDs, and PBJs. The results were inconclusive. Two of the pilotless bombs were lost en route to targets because of radio interference, mechanical defects caused five crashes, Japanese antiaircraft shot down three, and five drones had television failures and could not locate a target. Of those drones that did attack, 18 hit their objective and 11 missed or near missed. ComAirNorSols concluded that there was a future for this weapon, but that it needed more development work and better aircraft for drones. Evidently, the Chief of Naval Operations, who in August had turned down a request to use SBDs as drones, agreed with General Mitchell’s evaluation. Since the “better aircraft” were needed elsewhere, the test unit was decommissioned shortly after completing its last strike on 26 October.42

Vastly more effective than the imaginative drone bombs were the attacks by more workaday aircraft. The Corsairs, in particular, expanded their usefulness through regular bombing missions, since there was little call for them in their role as interceptors. It was this aspect of the Corsairs’ capabilities, however, that brought about their employment in the Philippines.

Fighter planes were badly needed at Leyte where Third Fleet carriers had stayed a month beyond the time of their scheduled departure for a strike on Japan in order to fly cover for amphibious shipping. Two of the Seventh Fleet’s escort carriers had been lost in the Battle of Leyte Gulf and four more had been damaged,

so that Admiral Kinkaid was desperately short of planes for air defense. Fifth Air Force P-38s, based at a muddy, inadequate forward airstrip at Tacloban, had their hands full defending the immediate beachhead area and could do little to augment the shipping protection afforded by carrier aircraft. Greatly increasing the seriousness of the air picture was the advent of the kamikazes, the Japanese suicide pilots who crashed their bomb-laden planes against shipping targets.

Admiral Halsey, who was anxious to free his carriers for the attack on the Japanese home islands, saw a solution to his problem in the Marine Corsairs of the 1st Wing. He reminded General MacArthur that these fighters were available and had proved themselves repeatedly when they flew under Halsey’s command.43 They were capable of reinforcing the Army Air Forces’ planes in interceptor and ground support roles and would be a welcome addition to the air cover of the Seventh Fleet’s ships. Deciding quickly to employ the Marine planes, MacArthur ordered them brought forward. On 30 November, General Mitchell received a directive from Allied Air Forces to transfer four of the 1st Wing’s Corsair squadrons to operational control of the Fifth Air Force on Leyte. The planes were to arrive at Tacloban by 3 December.

As soon as the order was received, MAG-12 (VMF-115, -211, -218, and -313) was alerted for the move and ceased all combat operations under ComAirNorSols. With Marine PBJs as navigational escorts, the flight echelons of group headquarters and the fighter squadrons arrived in the Philippines on schedule, after covering 1,957 miles from Emirau via Hollandia and Peleliu. A shuttle service by R4Ds of MAG-25, supplemented by C-47s of the Fifth Air Force, carried essential maintenance men and material forward to insure that the Corsairs kept flying. On 5 December, MAG-12 pilots flew their initial combat patrols in the Philippines and shot down the first of a long string of enemy planes.44

On 7 December, a week after the first Marine fighters were ordered to Leyte, MAG-14 and the remaining four Corsair squadrons in the 1st Wing were put on 48-hours notice for a forward movement. This time the destination was an airfield yet to be built on Samar, and the move was not so precipitate as that of MAG-12. The first squadron of MAG-14 to fly in from Green, VMO-251,45 arrived on Samar on 2 January. The forward echelons of the group headquarters and service squadrons, and of VMF-212, -222, and -223, had arrived by 24 January. Again PBJs guided and escorted the Corsairs and, stripped of most of their guns and extra weight, helped transport key personnel and priority equipment from Green

Leyte invasion fleet assembled in Seeadler Harbor in the Admiralties symbolizes the move forward from the Solomons and Bismarcks. (SC 283167)

Marine Mitchells fly over Crater Peninsula during one of the ceaseless round of suppressive attacks that neutralized Rabaul. (USMC 114743)

and Piva in addition. Marine and Army transports planes carried the bulk of the men and gear of the forward echelon.

The ground echelons of the Marine fighter groups were not able to begin moving to the Philippines until February when shipping priorities eased after the Luzon landings. In contrast, a good part of the ground echelons of MAG-24 and -32 squadrons preceded their planes to Luzon and helped establish a field at Mangaldan near Lingayen Gulf. Flights of SBDs began arriving from the Bismarcks on 25 January, and, by the end of the month, all seven Dauntless squadrons were operational.46

The withdrawal of Marine fighters and dive bombers from operational control of ComAirNorSols placed the burden of maintaining the aerial blockade of the bypassed Japanese on RNZAF Corsairs and Venturas and MAG-61’s Mitchells. The New Zealanders smoothly took on all fighter-bomber commitments that the Marines had handled; there was no break in the unremitting pattern of harassing attacks and watchdog patrols. RNZAF Corsairs also flew close and direct support strikes for the Australian infantrymen on Bougainville, working closely with the RAAF tactical reconnaissance aircraft attached to the II Corps. The Mitchells and Venturas also flew ground support missions for the Australians, but spent most of their time making bombing attacks on Rabaul, Kavieng, and the other principal Japanese bases.

The Venturas, which were not fitted with a bombsight suitable for medium-level (9,500-13,000 feet) drops until April 1945, relied on Marine PBJs as strike leaders in this type of mission. When the Mitchell released its bombs, the accompanying RNZAF bombers dropped theirs also. The resulting concentration of hits was particularly effective against the larger targets found at Rabaul, where most of the medium-level bombing was done. Low-level attacks by both the Mitchell and Ventura squadrons were aimed primarily at targets that were not so well protected by antiaircraft as those at Rabaul.

Only one squadron of MAG-61’s Mitchells was freed from the frustrating round of policing missions in the Bismarcks and Solomons. On 3 March, on orders from Allied Air Forces, VMB-611 was transferred to MAG-32 with orders to move forward from Emirau to the Philippines. By the end of the month, 611’s PBJs were operating from fields on Mindanao. The four bombing squadrons remaining in MAG-61, VMB-413, -423, -433, and -443, served the last months of the war at Emirau and Green. Orders to deploy to the Philippines were finally received just prior to the end of the fighting.

As if to signify the near completion of the aerial campaign that had begun at Guadalcanal almost three years before, General Mitchell relinquished command of AirNorSols and the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing on 3 June 1945 and returned to the States two days later. A little over a month after the general’s departure, the long-awaited transfer of control of air operations to the RNZAF finally took place. On 15 July, Air Commodore Roberts assumed command from Marine Brigadier General Lewie G. Merritt and AirNorSols was dissolved. General Merritt’s 1st Wing now came under the

orders of the New Zealand Air Task Force.47

By the time Air Commodore Roberts took over the direction of air operations, the primary mission of most combat aircraft in his command was support of the Australian ground forces of II Corps. On Bougainville, in a nine-months-long offensive, the Australians had pushed the Japanese back in all directions from the Torokina perimeter and were driving on the enemy positions at Buin, Numa-Numa, and Bonis. On New Britain, the Australians, operating from a base camp at Jacquinot Bay on the southern coast, kept aggressive patrols forward in the Open Bay-Wide Bay region of Gazelle Peninsula, sealing off the Japanese at Rabaul from the rest of the island. In March, when an airfield was opened at Jacquinot, RAAF planes and, later, RNZAF Corsairs and Venturas, flew ground support missions and attacked the enemy at Rabaul. (See Map 31.)

On 3 August, General Kenney directed General Merritt to move the headquarters of the 1st Wing and MAG-61 to the Philippines. Six days later, Marine planes flew their last bombing mission against Rabaul. Six PBJs from VMB-413, six from VMB-423, five from VMB-443, and one from group headquarters took part; an RNZAF Catalina went along as rescue Dumbo. Each Mitchell carried eight 250-pound bombs which were dropped through heavy cloud cover with unobserved results; the targets were storage and bivouac areas near Rabaul and Vunakanau.

When the fighting ended on 14 August, some Mitchells had already flown to the Philippines, the remainder made the trip by the 19th. The wing’s command post shifted from Bougainville to Zamboanga on Mindanao on 15 August. Ahead of the Marine squadrons lay months of hectic peacetime employment in North China as part of the American occupation forces. Behind the flyers and ground crews was a solid, lasting record of achievement in every task of aerial combat and blockade that had been asked of them.