Part III: The Marshalls: Quickening the Pace

Blank page

Chapter 1 : FLINTLOCK Plans and Preparations1

Getting on with the War

During the series of Allied conferences that resulted in approval for the Central Pacific campaign, the first proposed objective was the Marshalls. Because of the lack of information concerning these islands and the shortage of men and materiel, the initial blow struck the Gilberts instead. After the capture of Apamama, Makin, and Tarawa, planes based at these atolls gathered the needed intelligence. As this information was processed, American planners prepared and revised several concepts for an offensive against the Marshalls.

Like GALVANIC, the invasion of the Marshalls was the responsibility of the Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas, Admiral Nimitz. His principal subordinate planner was Admiral Spruance, Commander, Fifth Fleet and Central Pacific Force.2 Admiral Turner, Commander, V Amphibious Force, and General Holland Smith, Commanding General, V Amphibious Corps, were the officers upon whom Spruance relied for advice throughout the planning of the operation.

Early Plans for the Marshalls

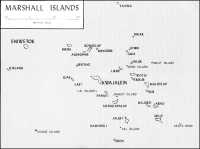

The Marshalls consist of two island chains, Ratak (Sunrise) in the east and Ralik (Sunset) in the west. Some 32 atolls of varying size form the Marshalls group. Those of the greatest military importance by late 1943 were Mille, Maloelap, and Wotje in the Ratak chain, and in the Ralik chain, Jaluit, Kwajalein, and Eniwetok. Except for

Jaluit, which was a seaplane base,3 all of these atolls were the sites of enemy airfields, and those in the Ralik chain were suitable as naval anchorages.4 (See Map 7.)

In May 1943, at the Washington Conference, the CCS recommended to the Allied heads of state that an offensive be launched into the Marshalls. At this time, American planners believed that the services of two amphibious divisions and three months’ time would be needed to neutralize or occupy all of the major atolls in the group and Wake Island, as well. The JCS considered the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Marine Divisions available for immediate service and was certain that the 4th Marine Division, then training in the United States, would be ready for combat by the end of the year.5

After the Washington Conference had adjourned, the JCS directed Admiral Nimitz to submit a plan for operations against the Marshalls, and the admiral responded with a preliminary proposal,6 necessarily vague because he lacked adequate information on the area. Within three weeks after receiving Nimitz’ views, on 20 July the JCS directed him to plan for an attack against the Gilberts, a move to be made prior to the Marshalls offensive. Thus, early planning for the Marshalls coincided with preparations for GALVANIC.

By the end of August, Nimitz and his staff had carefully evaluated the proposed Marshalls operation. In their opinion, the United States was strong enough to undertake an offensive that would strengthen the security of Allied lines of communications, win bases for the American fleet, force the enemy to redeploy men and ships, and possibly result in a stinging defeat for the Imperial Navy. The attackers, however, would need to gain aerial superiority in the area and obtain accurate intelligence. A solution was required for the logistical problem of sustaining the fleet in extended operations some 2,000 miles west of Pearl Harbor. Finally, VAC would have to speed the training of the 35,000 amphibious troops required for the campaign. The proposed objectives were key islands in Kwajalein, Wotje, and Maloelap Atolls. Central Pacific amphibious forces were to seize all of these simultaneously while ships and aircraft neutralized Jaluit and Mille. Nimitz now requested specific authorization to seize control of the Marshalls, urging that “thus we get on with the war.”7

At the Quebec Conference of August 1943, Allied leaders agreed that an effort against the Marshalls should follow the successful conquest of the Gilberts. Accordingly, the JCS on 1 September issued Nimitz a directive to undertake the operations he had recently proposed and, upon their completion, to seize or neutralize Wake Island

Map 7: Marshall Islands

and Eniwetok, as well as Kusaie in the Carolines. By this time, the 2nd Marine Division was committed to GALVANIC, the 1st to the New Britain operation, and the 3rd to the Solomons offensive. As assault troops for the Marshalls, the JCS made available, pending the completion of its training, the 4th Marine Division and also selected the 7th Infantry Division, which had seen action in the Aleutians, and the 22nd Marines, then guarding Samoa.8 See Map I.)

The Shaping of Flintlock9

On 22 September, Nimitz handed Spruance a preliminary study in support of the course of action he had proposed to the JCS and directed him to prepare to assault the Marshalls on 1 January 1944. The study itself was not considered complete, so the objectives might be altered as additional intelligence became available.10 Because of this lack of information on the Marshalls area, Spruance began studying two alternatives to Nimitz’ suggested course of action. All of these proposals called for simultaneous assaults, at some time in the operation, upon three atolls, Maloelap, Wotje, and either Mille or Kwajalein.11

Although Nimitz on 12 October issued an operation plan for FLINTLOCK, the Marshalls Operation, he avoided selecting specific objectives. Within two days, however, he decided to employ the 7th Infantry Division against both Wotje and Maloelap and to attack Kwajalein with the 4th Marine Division and 22nd Marines. He fixed 1 January 1944 as target date for the storming on Wotje and Maloelap and proposed to attack Kwajalein on the following day.

General Holland Smith’s VAC staff now prepared an estimate of the situation based on the preliminary plans advanced by Admirals Nimitz and Spruance. The likeliest course of action, according to the VAC paper, was to strike simultaneously at Wotje and Maloelap, with the Kwajalein assault troops serving as reserve. On the following day, or as soon as the need for reinforcements had passed, the conquest of the third objective would begin. Smith’s headquarters drew up a tentative operation plan for such a campaign, but at this point the attack against the Gilberts temporarily halted work on FLINTLOCK.

Prior to the GALVANIC operation, Admiral Turner had done little more than gather information concerning the proposed Marshalls offensive. Immediately following the conquest of the Gilberts, Turner’s staff carefully examined the FLINTLOCK concept and concluded that Maloelap and Wotje should be secured before Kwajalein was attacked. Meanwhile, every planning agency in the Central Pacific Area was digesting the lessons of GALVANIC. Among other things, the theories regarding naval gunfire were revised.

As an Army officer assigned to General Smith’s staff phrased it, “Instead of shooting at geography, the ships learned to shoot at definite targets.”12 After they had evaluated events in the Gilberts and assessed their own strength, Turner and Smith agreed that with the forces available Kwajalein could not be taken immediately after the landings on Wotje and Maloelap. Nimitz, acting on the same information available to his subordinates, also desired to alter FLINTLOCK, but in an entirely different manner.

On 7 December, CinCPac proposed an amphibious thrust at Kwajalein in the western Marshalls, coupled with the neutralization of the surrounding Japanese bases. In a series of conferences of senior commanders that followed, General Smith joined Admirals Turner and Spruance in objecting to this bold stroke.13 Spruance, the most determined of the three, pointed out that immediately after the capture of Kwajalein units of his Central Pacific Force were scheduled to depart for the South Pacific. Once the fast carriers had steamed southward, he could no longer maintain the neutralization of Wotje, Maloelap, Mille, and Jaluit, and the enemy would be able to ferry planes to these Marshalls bases in order to attack the line of communications between the Gilberts and Kwajalein. Spruance also desired to ease the logistical strain by seizing an additional fleet anchorage in the Marshalls. To meet the last objective Nimitz included in FLINTLOCK the capture of a second atoll, one that was weakly defended. To cripple Japanese air power, he approved a more thorough pounding of the enemy bases that ringed Kwajalein.14

After informing the JCS of his change of plans, Nimitz on 14 December directed Spruance and his other subordinates to devise a plan for the assault on Roi and Kwajalein Islands in Kwajalein Atoll. The alternative objectives were Maloelap and Wotje, but whichever objectives were attacked, D-Day was fixed as 17 January 1944.15 On 18 December, Nimitz informed King that he had set back D-Day to 31 January in view of the need for additional time for training and the need to make repairs to the carriers USS Saratoga, Princeton, and Intrepid.16

The assignment of another reinforced regiment, the 106th RCT of the 27th Infantry Division, to the FLINTLOCK force increased the number of men available for the expanded plan, but Turner continued to worry about the readiness of the various units. On 20 December, he requested that D-Day be postponed until 10 February to allow the two divisions to receive the proper equipment and to enable the 4th Marine Division to hold rehearsals.17 No further delays were authorized, however, as the JCS had directed that

the operation get under way “not later than 31 January 1944.”18

Nimitz’ headquarters on 20 December issued FLINTLOCK II, a joint staff study which incorporated the results of his recent conversations with Spruance. Carrier aircraft, land-based bombers, and surface ships were to blast the Japanese bases at Wotje and Maloelap. If necessary, the carriers would launch strikes to aid land-based planes in neutralizing Mille, Jaluit, Kusaie, and Eniwetok. The primary objectives remained Roi and Kwajalein Islands, but a secondary target, Majuro Atoll, was also included.

Admiral Spruance, in reviewing the reasons that he recommended Majuro as an objective, stated:–

Airfields on Majuro would enable us to help cover shipping moving in for the buildup of Kwajalein, and it would give us a fire protected anchorage at an early date for fleet use, if the capture of Kwajalein were a protracted operation. We had been fortunate during the Gilberts operation in being able to fuel fleet forces at sea without having them attacked by submarines. This we did by shifting the fueling areas daily. There were too many islands through the Marshalls for that area to lend itself to this procedure.”19

With the final selection on 26 December of an assault force for Majuro, the FLINTLOCK plan was completed. For a time, General Smith had considered using most of Tactical Group I, the 22nd Marines and the 106th Infantry, against Majuro. A staff officer of Tactical Group I, who was present during the discussions of this phase of the operation, recalled that “General Holland Smith paced the floor of the little planning room, cigar butt in mouth or hand—thinking out loud.” Thanks to additional intelligence, the choice by this time lay between employing an entire regiment or a smaller force. After weighing the evidence, Smith announced he was “convinced that there can’t be more than a squad or two on those islands today ... let’s use only one battalion for the Majuro job.”20 As a result, 2/106 was given the task of seizing Majuro, while the remainder of that regiment and the 22nd Marines were designated the reserve for FLINTLOCK.

Organization and Command

Task Force 50, commanded by Admiral Spruance, included all the forces assigned to the FLINTLOCK operation. Its major components were: Task Force 58, Rear Admiral Marc A. Mitscher’s fast carriers and modern battleships; Task Force 57, Defense Forces and Land-Based Air, commanded by Rear Admiral John H. Hoover; Task Group 50.15, the Neutralization Group under Rear Admiral Ernest G. Small; and Admiral Turner’s Task Force 51, the Joint Expeditionary Force. Admiral Spruance decided to accompany the expedition to the Marshalls, but he would not assume tactical command unless the Imperial Japanese Navy chose to contest the operation.

Admiral Turner, as commander of

the Joint Expeditionary Force, was primarily concerned with conveying the assault troops to the objective and getting them safely ashore. Within his command were: the Southern Attack Force, over which he retained personal command; the Northern Attack Force, entrusted to Rear Admiral Richard L. Conolly, a veteran of the Sicily landings; the Majuro Attack Group under Rear Admiral Hill, commander at Tarawa; Captain Harold B. Sallada’s Headquarters, Supporting Aircraft, the agency through which Admirals Turner, Conolly, and Hill would direct aerial support of the landings; and General Smith’s Expeditionary Troops. Among the 297 vessels assigned to Turner for FLINTLOCK were two new AGC command ships, 7 old battleships, 11 carriers of various classes, 12 cruisers, 75 destroyers and destroyer escorts, 46 transports, 27 cargo vessels, 5 LSDs, and 45 LSTs.21

As far as General Smith’s status was concerned, Spruance’s command structure for FLINTLOCK fit the situation and continued the primary responsibility of Admiral Turner for the success of the operation.22 Until the amphibious phase was completed and the troops were ashore, Admiral Turner would, through the attack force commanders, exercise tactical control. After the 7th Infantry Division had landed on Kwajalein Island and the 4th Marine Division on Roi-Namur, General Smith was to assume the authority of corps commander and retain it until Admiral Spruance declared the capture and occupation of the objectives to be completed. The authority of the Marine general, however, was as limited as it had been in the Gilberts operation, for he could not make major changes in the tactical plan nor order unscheduled major landings without the approval of Admiral Turner. Included in Expeditionary Troops with the two assault divisions were the 106th Infantry, 22nd Marines, the 1st and 15th Marine Defense Battalions, Marine Headquarters and Service Squadron 31, and several Army and Navy units which would help garrison and develop the captured atolls.

At Roi-Namur, objective of the Northern Attack Force, and at Kwajalein Island, where the Southern Attack Force would strike, Admirals Conolly and Turner were initially to command the assault forces through the appropriate landing force commander. As soon as the landing force commander knew that his troops had made a lodgment, he was to assume command ashore. The Majuro operation was an exception, for Admiral Hill, in command of the attack group, was in control from the time his ships arrived, throughout the fighting ashore, until Admiral Spruance proclaimed the atoll captured.

Applying the Lessons of Tarawa

Everyone who took part in planning FLINTLOCK profited from the recent GALVANIC operation. To prevent a repetition of the sort of communications failures that had happened off

Betio, the commander of each attack force was to sail in a ship especially designed to serve as a floating headquarters during an amphibious assault. The AGC Rocky Mount would carry Turner to Kwajalein, while Conolly would command the Roi-Namur assault from the AGC Appalachian. The Cambria, a transport equipped with additional communications equipment, was assigned to Admiral Hill for use at Majuro.

Prior to the attack on Tarawa, Marine planners had requested permission to land first on the islands near Betio to gain artillery positions from which to support the main assault. The loss of surprise and the consequent risk to valuable shipping were judged to outweigh the tactical benefits to be gained from these preparatory landings, and the 2nd Marine Division was directed to strike directly at the principal objective. Such was not the case in FLINTLOCK. Plans called for both the 7th Infantry Division and the 4th Marine Division to occupy four lesser islands before launching their main attacks.

In addition to providing for artillery support of the major landings, planners sought to increase the effectiveness of naval gunfire. On D minus 1, while cruisers and destroyers of Task Force 51 bombarded Maloelap and Wotje, Admiral Mitscher’s fast battleships were to hammer Roi-Namur and Kwajalein Islands. At dawn, elements of Task Force 58 would begin the task of destroying Japanese aircraft, making the flight strips temporarily useless, and shattering coastal defense guns. After pausing for an air strike, the ships were to resume firing, primarily against shore defenses. On D-Day, the landing forces would seize certain small islands adjacent to the main objectives. These operations were to be supported by naval gunfire and aerial bombardment in a manner similar to that planned for the assaults on Kwajalein Island and Roi-Namur. Plans also called for the American warships to maintain the neutralization of principal objectives while supporting the secondary landings elsewhere in the atoll.

About 25 minutes before H-Hour for the main landings, cruisers, destroyers, and LCI(G)s were to begin firing into the assault beaches, distributing high explosives throughout an area bounded by lines 100 yards seaward of the edge of the water, 200 yards inshore, and 300 yards beyond both flanks. Admiral Turner directed that cruisers continue their bombardment until the landing craft were 1,000 yards from shore, destroyers until the assault waves were 500 yards or less from the island, and LCI(G)s until the troops were even closer to their assigned beaches. Since the plan depended upon the progress of the assault rather than on a fixed schedule, the defenders would not be given the sort of respite gained by the Betio garrison.23

The LCI(G)s which figured so prominently in Admiral Turner’s plans were infantry landing craft converted into shallow-draft gunboats. These vessels mounted .50 caliber machine guns, 40-mm and 20-mm guns, as well as 4.5-inch rockets. Another means of neutralizing the beach defenses was provided by the armored amphibian, LVT(A)(1), which boasted a 37-mm gun and five .30 caliber machine guns. One machine gun was located atop the turret, one was mounted coaxially with the cannon, a third was located in a ball and socket mount in the forepart of the hull, and the other two were placed on ring mounts to the rear of the turret.24 Protection for the crew of six was provided by ¼ to ½ inch of armor plate and by small shields fixed to the exposed machine guns. Neither the LCI(G)s nor the LVT(A)(1)s were troop carriers.25 A few LVT(2)s with troops embarked were equipped with multiple rocket launchers to assist in the last-minute pounding of Japanese shore defenses.

Admiral Turner and General Smith also attempted to increase the effectiveness of supporting aircraft. The strikes delivered to cover the approaching assault waves were scheduled according to the progress of the LVTs. When the amphibian tractors reached a specified distance from the beaches, the planes would begin their attacks, diving parallel to the course of the landing craft and at a steep angle to lessen the danger of accidentally hitting friendly troops. During these preassault aerial attacks, both naval guns and artillery were ordered to suspend firing,

Throughout the operation, carrier planes assigned to support ground troops were subject to control by both the Commander, Support Aircraft, and the airborne coordinator. The coordinator, whose plane remained on station during daylight hours, could initiate strikes against targets of opportunity, but the other officer, who received his information from the attack force commanders, was better able to arrange for attacks that involved close cooperation with artillery or naval gunfire. During GALVANIC, the airborne coordinator had performed the additional task of relaying information on the progress of the battle. This extra burden now fell to a ground officer, trained as an aerial observer, who would report from dawn to dusk on the location of friendly units, enemy strongpoints, and hostile activities.26

The Landing Force Plans

The objectives finally selected for FLINTLOCK were Majuro and Kwajalein Atolls. Measuring about 24 miles from east to west and 5 miles from north to south, Majuro was located 220 nautical miles southeast of Kwajalein. Admiral Hill, in command of the Majuro force, decided to await the results of a final reconnaissance before choosing his course of action. Elements of the VAC Reconnaissance Company

Map 8: Kwajalein Atoll

would land on Eroj and Calalin, the islands that guarded the entrance to Majuro lagoon, then scout the remaining islands. Once Japanese strength and dispositions had been determined, the landing force, 2/106, could make its assault.

Kwajalein Atoll, 540 miles northwest of Tarawa, is a triangular grouping of 93 small reef-encircled islands. The enclosed lagoon covers 655 square miles. Because of the vast size of the atoll, Admiral Turner had divided the Expeditionary Force into Northern and Southern Landing Forces. In the north, at the apex of the triangle, the recently activated 4th Marine Division, commanded by Major General Harry Schmidt, a veteran of the Nicaraguan campaign, was to seize Roi-Namur, twin islands joined by a causeway and a narrow strip of beach. The site of a Japanese airfield, Roi had been stripped of vegetation, but Namur, where the enemy had constructed numerous concrete buildings, was covered with palms, breadfruit trees, and brush. The code names chosen for the islands were CAMOUFLAGE for wooded Namur and for Roi, because so little of it was concealed, BURLESQUE.27 (See Map 8.)

Crescent-shaped Kwajalein Island, objective of the Southern Landing Force, lay at the southeastern corner of the atoll, some 44 nautical miles from Roi-Namur. Major General Charles H. Corlett, who had led the Kiska landing force, would hurl his 7th Infantry Division against the largest island in the atoll. Here the enemy had constructed an airfield and over 100 large buildings. Although portions of the seaward coastline were heavily wooded, an extensive road net covered most of the island.

Throughout the planning of the Marshalls operation, General Schmidt and his staff were located at Camp Pendleton, California, some 2,200 miles from General Smith’s headquarters at Pearl Harbor. The problem posed by this distance was solved by shuttling staff officers back and forth across the Pacific, but division planners continued to work under two disadvantages, a shortage of time and a lack of information. These twin difficulties stemmed from Admiral Nimitz’ sudden decision to attack Kwajalein Atoll, bypassing Wotje and Maloelap. The division staff, however, proved adequate to the challenge, and by the end of December its basic plan had been approved by VAC. The timing of approval and issue was so tight, however, that some units sailed for Hawaii without seeing a copy.28

The Northern Landing Force plan consisted of three phases: the capture of four offshore islands, the seizure of Roi-Namur, and the securing of 11 small islands along the northeastern rim of Kwajalein Atoll. The first phase was entrusted to the IVAN Landing Group, the 25th Marines, Reinforced, commanded by Brigadier General James L. Underhill, the Assistant Division Commander. These troops were to seize ALBERT (Ennumennet), ALLEN (Ennubirr), JACOB (Ennuebing), and IVAN (Mellu) Islands as firing positions for

the 14th Marines, the division artillery regiment. The troops involved in this operation would land from LVTs provided by the 10th Amphibian Tractor Battalion. Company A, 11th Amphibian Tractor Battalion, which reinforced the 10th, along with Companies B and D, 1st Armored Amphibian Battalion, were chosen to spearhead the assaults. When this phase was completed, the LVT and artillery units would revert to division control, and the 25th Marines would become the division reserve for the next phase.

The 23rd Marines received the assignment of storming Roi while the 24th Marines simultaneously attacked Namur. Both regiments were to land from the lagoon, the 23rd Marines over Red Beaches 2 and 3 and the 24th Marines on Green 1 and 2. In the meantime, the 25th Marines could be called upon to capture ABRAHAM (Ennugarret) Island.29 Detailed plans for the final phase were not issued at this time.

General Schmidt organized his assault waves to obtain the most devastating effect from his armored amphibians and LCI gunboats. The LCI(G)s were to lead the way until they were about 1,000 yards from the beach. Here they were to halt, fire their rockets, and continue to support the assault with their automatic weapons. Then the LVT(A)s would pass through the line of gunboats, open fire with 37-mm cannon and machine guns, and continue their barrage “from most advantageous positions.”30 The troop carriers were directed to follow the armored vehicles, passing through the line of supporting amphibians if it was stopped short of the beach. The few LVT(2)s armed with rockets were to discharge these missiles as they drew abreast of the LCIs.

The 7th Infantry Division faced fewer difficulties in planning for the capture of Kwajalein Island. General Corlett was experienced in large-scale amphibious operations, and two of his regiments, the 17th and 32nd Infantry, had fought at Attu, while the third, the 184th Infantry, had landed without opposition at Kiska. The Army division easily kept pace with the changes in the FLINTLOCK concept, for its headquarters was not far from General Smith’s corps headquarters.

Like the Marine division in the north, General Corlett’s Southern Landing Force faced an operation divided into several phases. The first of these was the capture of CARLSON (Enubuj), CARLOS (Ennylabegan), CECIL (Ninni), and CARTER (Gea) Islands by the 17th Infantry and its attached units. Once these objectives were secured and artillery emplaced on CARLSON, the 17th Infantry would revert to landing force reserve. Next, the 184th and 32nd Infantry would land at the western end of Kwajalein Island and attack down the long axis of the island. The third phase, the seizing of BURTON (Ebeye), BURNET (unnamed), BLAKENSHIP (Loi), BUSTER (unnamed), and BYRON (unnamed), as well as the final operations,

the landings on BEVERLY (South Gugegwe), BERLIN (North Gugegwe), BENSON (unnamed), and BENNETT (Bigej), were tentatively arranged, but the assault troops were not yet designated.31 (See Map 8.)

The assault formations devised by Corlett’s staff differed very little from those in the 4th Marine Division plan. Instead of preceding the first assault wave, the armored LVTs, amphibian tanks in Army terminology, were to take station on its flanks. Also, the Army plan called for the LVT(A)s to land regardless of Japanese opposition and support the advance from positions ashore. After the infantry had moved 100 yards inland, the amphibians might withdraw.32

Intelligence33

When Admiral Nimitz first began planning his Marshalls offensive, he had little information on the defenses of those islands. Because the enemy had held the area for almost a quarter-century, the Americans assumed that the atolls would be even more formidable than Tarawa. The first photographs of the probable objectives in the western Marshalls were not available to General Smith’s staff until after GALVANIC was completed. The corps, however, managed to complete its preliminary area study on 26 November. Copies of this document were then sent to both assault divisions. Throughout these weeks of planning, the 7th Infantry Division G-2 was a frequent visitor to General Smith’s headquarters, and this close liaison aided General Corlett in drafting his landing force plan. Unfortunately, close personal contact with the 4th Marine Division staff was impossible, but corps headquarters did exchange representatives with General Schmidt’s command. Carrier planes photographed Kwajalein Atoll during a raid on 4 December, but the pictures they made gave only limited coverage of this objective. Interviews with the pilots provided many missing details. Additional aerial photos of the atoll were taken during December and January. Reconnaissance planes took pictures of Majuro on 10 December. A final photographic mission was scheduled for Kwajalein atoll just two days before D-Day.

Submarines also contributed valuable intelligence on reefs, beaches, tides, and currents of Kwajalein. The Seal photographed the atoll in December, and the Tarpon carried out a similar mission the following month. Plans called for Underwater Demolition Teams, making their first appearance in combat, to finish the work begun by the undersea craft. These units were to scout the beaches of Kwajalein and Roi-Namur Islands on the night of 31 January-1 February. After obtaining up-to-date hydrographic data, the swimmers would return to destroy mines and antiboat obstacles.

By mid-January, VAC intelligence officers had concluded that Kwajalein Atoll, headquarters of the 6th Base Force and, temporarily, of the Fourth Fleet, was the cornerstone of the Marshalls fortress. Originally, most of the weapons emplaced on the larger islands of the atoll had been sited to protect the ocean beaches, but since the Tarawa operation, in which the Marines had attacked from the lagoon, the garrisons were strengthening and rearranging their defenses. Except for Kwajalein Island, where photographs indicated a cross-island line, the Japanese had concentrated their heaviest installations along the beaches. In general, the assault forces could expect a bitter fight at the beaches as the enemy attempted to thwart the landing. Once this outer perimeter was breached, the defenders would fight to the death from shell holes, ruined buildings, and other improvised positions.

The atoll garrison was believed to be composed of the 6th Base Force, 61st Naval Guard Force, a portion of the 122nd Infantry Regiment, and a detachment of the 4th Civil Engineers. Intelligence specialists believed that reinforcements, elements of the 52nd Division, were being transferred from the Carolines to various sites in the Marshalls. The enemy’s total strength throughout Kwajalein Atoll was estimated to be 8,000-9,600 men, 6,150-7,100 of them combat troops.

General Smith’s intelligence section predicted that the 7th Infantry Division would face 2,300-2,600 combat troops and 1,200-1,600 laborers. The enemy appeared to have built a defensive line across Kwajalein Island just east of the airfield, works designed to supplement the pillboxes, trenches, and gun emplacements that fringed the island. Photographs of Roi-Namur disclosed coastal perimeters that featured strongpoints at each corner of both islands. Very few weapons positions were discovered in the interior of either island. Namur, however, because of its many buildings and heavy undergrowth, offered the enemy an excellent chance to improvise a defense in depth. At both Kwajalein and Roi-Namur Islands, the installations along the ocean coasts were stronger than those facing the lagoon. No integrated defenses and only a small outpost detachment were observed on Majuro. (See Map V.)

Corps also had the task of preparing and distributing the charts and maps used by the assault troops, naval gunfire teams, defense battalions, and other elements of FLINTLOCK Expeditionary Troops. Each division received 1,000 copies of charts (on a scale of one inch to one nautical mile) and of special terrain maps (1:20,000), and as many as 2,000 copies of another type of special terrain map (1:3,000). On the 1:3,000 maps, the particular island was divided into north, east, west, and south zones. Within each zone, known gun positions were numbered in clockwise order, each number prefixed by N, E, W, or S to indicate the proper zone. All crossroads and road junctions also were given numbers. Besides the customary grid system, these maps also showed the number and outline of all naval gunfire sectors. By compressing so much information onto a single sheet, the corps devised a map that suited a variety of units.

The information gathered, evaluated, and distributed by Admiral Nimitz’ Joint Intelligence Center, General Smith’s amphibious corps, and Admiral Turner’s amphibious force was both accurate and timely. Sound intelligence enabled Nimitz to alter his plans and strike directly at Kwajalein. A knowledge of the enemy defenses made possible an accurate destructive bombardment and, together with hydrographic information, guided attack force and landing force commanders in the selection of assault beaches.

Communications and Control34

Generals Corlett and Schmidt planned to destroy the enemy garrison in a series of carefully coordinated amphibious landings. For this reason, success depended to a great extent upon reliable communications and accurate timing. Although the introduction of command vessels had given attack force and landing force commanders a better means of controlling the different phases of the operation, not every communications problem had been solved.

The Marine assault troops assigned to FLINTLOCK used much of the same communications equipment that had proved inadequate in the Gilberts. The radios in the LVTs were not waterproofed, a fact which would greatly reduce communication effectiveness during the landing.35 Both the TBX and TBY radios, neither type adequately waterproof, had to be used again in the Marshalls. Eventually, it was hoped, these sets could be replaced, the TBX by some new, lighter, and more reliable piece of equipment and the TBY by the portable SCR 300 and mobile SCR 610 used by the Army. Although intended for infantrymen rather than communications men, the hand-carried MU radios were too fragile to survive the rugged treatment given them in rifle units. The SCR 610 worked well, but it too was vulnerable to water damage. No waterproof bags were available for either spare radio batteries or telephone equipment.

In an attempt to insure unbroken communications, both the 4th Marine Division and the 7th Infantry Division were assigned Joint Assault Signal Companies (JASCOs). The Marine 1st JASCO was activated on 20 October 1943 at Camp Pendleton, California. The primary mission of this unit was to coordinate all supporting fires available to a Marine division during an amphibious operation. In order to carry out this function, the company was divided into Shore and Beach Party Communications Teams, Air Liaison Parties, and Shore Fire Control Parties. Early in December, the company joined VAC and was promptly attached to the 4th Marine Division. During training, the various teams were attached to the regiments and battalions of the division. Thus each assault battalion could become familiar with its shore and beach party, air liaison, and fire control teams. The Army 75th JASCO was attached in the same manner to the battalions of the 7th Infantry Division. Communications equipment, however,

was but a means of control. If the landings were to succeed, they would have to be precisely organized and accurately timed. Unit commanders and control officers would have to be located where they could see what was happening and influence the conduct of the battle. For FLINTLOCK, the movement of assault troops from the transports to the beaches was carefully planned, and an adequate system of control was devised.

Instead of transferring from transports to landing craft and finally to LVTs, as had been done at Tarawa, the first waves of assault troops were to move from the transports directly to the LSTs that carried their assigned tractors.36 The men would climb into the assault craft as the LSTs steamed to a position near the line of departure from which the ships would launch the amphibians. Next, the LVTs were to form waves, each one guided by a boat commander. At the line of departure, the commander of each wave reported to the control officer, a member of the V Amphibious Force staff.

Among other vessels, each control officer had at his disposal two LCCs (Landing Craft Control vessels), steel-hulled craft similar in appearance to motor torpedo boats. These carried radar and other navigational aids and were designated as flank guides for the leading assault waves. After the first four waves had crossed the reef, the LCCs, which were incapable of beaching and retracting, would take up station in a designated area 2,000 yards from shore. Since reserve units were to follow a transfer scheme similar to that planned for Tarawa, officers in the LCCs now had to supervise the shifting of men from landing craft to returning LVTs, as well as the formation of waves, and the dispatch of tractors to the beach.

A submarine chaser was assigned the control officer to enable him to move wherever he might be needed in the immediate vicinity of the line of departure. A representative of the landing force commander, the commander of the amphibian tractor battalion, a representative of the division supply officer, and a medical officer were embarked in the same craft. These men were given power to make decisions concerning the ship-to-shore movement, the landing of supplies, and the evacuation of wounded. A second submarine chaser, this one stationed continuously at the line of departure, carried a representative of the transport group commander. This officer saw to it that the waves crossed the line either according to the prearranged schedule, as the control officer directed, or in the case of later waves as the regimental commander requested.

Off the beach his troops were assaulting, the regimental commander was to establish a temporary floating command post in a submarine chaser. While in this vessel, he would be able to contact by radio or visual signals the landing force commander, the various boat waves, and his battalions already ashore. As soon as the regimental commanders had established command posts ashore, the submarine chasers

could be used by the division headquarters.

Logistics37

The geographical separation of the units assigned to FLINTLOCK affected logistical planning as well as tactical training. The 4th Marine Division trained at Camp Pendleton and prepared to sail from San Diego, the 7th Infantry Division and 106th Infantry trained on Oahu, and the 22nd Marines made ready in Samoa prior to its movement to the Hawaiian Islands. In spite of the distance involved, General Smith later reported that in the field of logistics “no major difficulties were encountered.”38

There were, however, several minor problems. The 22nd Marines, for example, was unable to obtain from Marine sources either 2.36-inch rocket launchers and ammunition for them, or shaped demolitions charges, but a last-minute request to Army agencies was successful.39 The 4th Marine Division had to revise its logistical plans in the midst of combat loading. Originally, Admiral Nimitz had prescribed that each division carry to the objective five units of fire for each of its weapons except antiaircraft guns. Officers of the 7th Infantry Division requested additional ammunition, but the admiral was reluctant to accept their recommendations. Not until 5 January did he approve 10 units of fire for 105-mm howitzers and 8 for all other ground weapons. Nor was the 7th Infantry Division without its troubles, for the water containers provided by Army sources proved useless, and drums had to be obtained from the Navy.

A total of 42 days’ rations was scheduled to be carried to Kwajalein Atoll. Each Marine or soldier was to land with 2 days’ emergency rations. A 4-day supply of the same type of food was loaded in LSTs, and an additional 6-day amount was lashed to pallets for storage in the transports. The cargo ships assigned to the expedition carried enough dried, canned, and processed food to last the assault and garrison troops for 30 days. Five day’s water, in 5-gallon cans and 55-gallon drums, was stowed in the LSTs and transports. Logistical plans also called for a 30-day quantity of maintenance, medical, and aviation supplies, as well as fuels and lubricants. The assault divisions and the garrison units also brought with them large amounts of barbed wire, sandbags, and light construction material.

Not all of this mountain of supplies and ammunition was combat loaded. Those items likely to be needed early in the operation were stowed in easily accessible places according to probable order of use. The remaining supplies were loaded deep within the cargo vessels in a manner calculated to conserve space. Some emergency supplies, including ammunition, water, and rations, were placed in LSTs.

Admiral Conolly divided his transports

into three groups, one per infantry regiment, each with four transports and a cargo vessel. The 105-mm howitzers of the 4th Marine Division were loaded into LCMs, landing craft that would be ferried to Roi-Namur in an LSD. The 75-mm pack howitzers were placed in LVTs, and these tractors embarked in LSTs. A second LSD carried the LCMs in which the 15 Shermans of the division medium tank company were loaded. All 36 light tanks of the 4th Tank Battalion were stowed in the transports. Admiral Turner, who had retained responsibility for conducting the 7th Infantry Division to Kwajalein Island, organized his shipping in much the same way.

At Tarawa, the flow of supplies to the assault units had been slow and uncertain. Admiral Turner, in an effort to prevent a similar disruption, directed that beach party and shore party units sail in the same transports, draw up joint plans, and land rapidly. Skeleton beach parties and elements of shore parties were assigned to the fourth wave at each beach, and the remainder of the units were ordered to follow as quickly as possible.

The corps directed the 7th Infantry Division to form shore parties from its 50th Engineer Battalion and elements of the Kwajalein Island garrison force, while the 4th Marine Division was to rely upon men from the 20th Marines, its engineer regiment. One shore party, reinforced by medical, quartermaster, ordnance, and other special troops, was attached to each infantry battalion. The principal weakness in this phase of the supply plan was the use of men from reserve combat units to bring the shore parties to their authorized strength of approximately 400. Pontoon causeways, broken into sections and loaded in LSTs, were made available for use at Roi-Namur, Kwajalein, and CARLSON Islands, and at Majuro Atoll. The pontoons could be joined together to serve as piers for the unloading of heavy equipment. Enough emergency supplies were loaded in LSTs to sustain the battle until the beaches were secured. At Roi-Namur, LVTs, the only amphibious cargo vehicles available to the Marine division, were to serve as the link between the LSTs and the battalions advancing inland. After the beaches had been secured, the transports would begin unloading.

The 7th Infantry Division had, in addition to its amphibian tractors, 100 DUKWs. These 2½-ton amphibian trucks were called upon to perform at Kwajalein Island much of the work expected of LVTs at Roi-Namur. Sixty DUKWs were assigned to land the division artillery, and 40 of them, also stowed in LSTs, were to give logistical support to infantry units by bringing ashore emergency supplies. Some of the critical items were loaded in the trucks before the parent LSTs sailed from Hawaii.

Admiral Turner’s medical plan gave beachmasters authority over the evacuation of wounded. Theirs was the task of selecting the boats or amphibious vehicles that would carry away casualties. The medical section of the beach party was responsible for distributing the wounded among the cargo ships and transports. All of these vessels could receive the injured, but by D plus 3 all casualties

would be collected in specified vessels or transferred to the hospital ships scheduled to arrive on that day.

Training for Flintlock

The 4th Marine Division was able to undergo amphibious training in conjunction with Admiral Conolly’s support ships and transports. A division exercise was held on 14-15 December, before either the admiral or General Schmidt were certain what course FLINTLOCK would follow. Another exercise took place at San Clemente Island off the California coast on 2-3 January 1944. This second landing was in effect a rehearsal, for all amphibious shipping joined many of Conolly’s warships and carriers in the exercise.

The January landing also gave the division a chance to test its aerial observers. These were the ground officers who would be flown over Roi-Namur to report throughout the day on the progress of the battle. This aspect of the exercise was a complete success, but the work of the LVTs and LSTs was far less impressive.

On 5 December, the division’s 4th Amphibian Tractor Battalion was broken up, and four/seventh’s of its men were used to form the cadre of the 10th Amphibian Tractor Battalion, reinforced by Company A, 11th Amphibian Tractor Battalion.40 The two units were then brought up to authorized strength by the addition of recruits and the transfer of trained crews from the 1st Armored Amphibian Battalion. By the time these changes had been made, less than a month remained in which to check the tractors, install armor plate, waterproof radios, train the new crews, lay plans for the landings, take part in the San Clemente rehearsal, load the vehicles into amphibious shipping, and make a final check to determine that the LVTs were fit for combat. These varied tasks had to be carried out simultaneously with the obtaining of supplies, processing of men, and the other duties routine to a unit preparing for action. Unfortunately, many of the LSTs were manned by sailors as inexperienced as the Marine tractor crews. Admiral Conolly recalled:–

A number of these ships were rushed from their Ohio River building yards straight to the West Coast. They had inadequate basic training, little or no time to work with their embarked troops, and, in some cases, arrived in San Diego a matter of a few days before final departure for the Marshalls.41

Although the San Clemente exercise was staged to promote close cooperation between the LSTs and LVTs, the sailors and Marines gained little confidence in one another. Some of the ships refused to recover any tractors except those they had launched; as a result several tractors ran out of gas and were lost. There also was one collision between an LST and an LVT. “All this,” one participant drily observed,

“was very poor for morale just before combat.”42

The LSTs, loaded with amphibian tractors, sailed from San Diego on 6 January, to be followed a week later by the remainder of Admiral Conolly’s attack force. At the time of its departure, the first convoy had not yet received copies of the final operations plans issued by Admirals Spruance, Turner, and Conolly. These documents did not arrive until 18 January, two days before the LSTs set sail for the Marshalls and two days prior to the arrival of the rest of Conolly’s ships in Hawaiian waters. Since the two groups shaped different courses toward the objective, there was no opportunity for last-minute coordination.43

General Corlett, like General Schmidt, had carefully studied the lessons of Tarawa, so the 7th Infantry Division also was thoroughly trained for atoll warfare. The Army unit, however, had its share of problems in finding crews for its amphibian tractors. On 25 November, the division established a school to train members of the regimental antitank companies as LVT drivers and mechanics. The graduates of this course were selected to man the tractors that would carry the assault waves. The landings would be supported by the 708th Amphibian Tank Battalion which was attached to the division early in December. For FLINTLOCK the amphibian tractors were incorporated into the Army tank battalion and the resultant organization called the 708th Provisional Amphibian Tractor Battalion.44

By the time of its attachment to VAC for operational control, the 7th Infantry Division was well grounded in tank-infantry-engineer teamwork. The amphibious training of General Corlett’s troops took place in December and January, with the most attention devoted to the comparatively inexperienced 184th Infantry. The division and the 22nd Marines conducted their final rehearsals between 12 and 17 January. The troops landed at Maui’s Maalaea Bay and made a simulated assault on Kahoolawe Island. The Majuro landing force, 2/106, made a practice landing on the shores of Oahu on 14 January.

Preliminary Operations45

Aircraft of all services joined surface ships in a series of raids planned to batter Kwajalein Atoll, neutralize the Japanese bases that surrounded it, and gain information on the enemy’s defenses. Mille, Jaluit, and Maloelap were the principal targets hit during November and December by Army and Navy planes of Admiral Hoover’s command. During January, after the Gilberts fields had been completed, the heaviest tonnage fell on Kwajalein and Wotje. Land-based planes in December

and January dropped 326 tons of explosives on targets in Maloelap Atoll, 313 on Kwajalein, 256 on Jaluit, 415 on Mille, and 367 on Wotje. The Japanese retaliated by loosing a total of 193 tons of bombs on Makin, Tarawa, and Apamama. In the meantime, patrol bombers from Midway were active over Wake Island.

On 4 December, while Army bombers were raiding Nauru Island and Mille, carrier task groups commanded by Rear Admirals Charles A. Pownall and Alfred E. Montgomery launched 246 planes against Kwajalein and Wotje Atolls. The aviators sank 4 cargo ships, damaged 2 old light cruisers, shot down 19 enemy fighters, and destroyed many other planes on the ground. Japanese fliers, stung by this blow, caught the retiring carriers, and in a night torpedo attack damaged the USS Lexington.

Except for an attack by carrier aircraft and surface ships against Nauru on 8 December, land-based planes swung the cudgel until 29 January. On that day, carriers and fast battleships returned to the Marshalls, attacking the Japanese bases in an unexpected thrust from the westward.46 Rear Admiral Samuel P. Ginder’s carriers hit Maloelap, and Rear Admiral John W. Reeves sent his aircraft against Wotje, while carrier task groups commanded by Rear Admiral Frederick C. Sherman and Admiral Montgomery attacked Kwajalein and Roi-Namur Islands. Surface ships bombarded the targets in conjunction with the air raids.

On 30 January, Reeves took over the preparatory attack against Kwajalein Island, while Sherman began a 3-day effort against Eniwetok Atoll.47 Ginder maintained the neutralization of Wotje, refueled, and on 3 February replaced Sherman. The task groups under Reeves and Montgomery continued to support operations at Kwajalein Atoll until 3 February.

As these preparations mounted in intensity, the Northern and Southern Attack Forces drew near to their objectives. On 30 January, fire support ships of these forces paused to hammer Wotje and Maloelap before continuing onward to Roi-Namur and Kwajalein. Meanwhile, the supporting escort carriers (CVEs) joined in the preparatory aerial bombardment of the objectives. On 31 January, the 4th Marine Division and 7th Infantry Division would begin operations against island fortresses believed to be stronger than Betio.

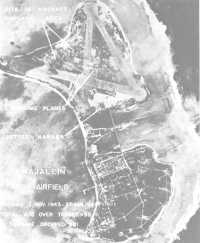

Roi-Namur, under bombing attack by Seventh Air Force planes, appears in an intelligence photo taken just prior to the prelanding bombardment. (USAF B50003AC)

The Defenses of Kwajalein Atoll48

Just as he had startled his subordinates by proposing an immediate attack on Kwajalein, Nimitz also surprised his adversaries. “There was divided opinion as to whether you would land at Jaluit or Mille,” a Japanese naval officer confessed after the war. “Some thought you would land on Wotje, but there were few who thought you would go right to the heart of the Marshalls and take Kwajalein.”49

Unlike their leaders, the defenders of Kwajalein Atoll, dazed by a succession of air raids, quickly became convinced that their atoll ranked high on Nimitz’ list of objectives. “I welcome the New Year at my ready station beside the gun,” commented a squad leader in the 61st Guard Force. “This will be a year of decisive battles. I suppose the enemy, after taking Tarawa and Makin, will continue on to the Marshalls, but the Kwajalein defenses are very strong.”50

Actually the Japanese high command had been slow to grasp the importance of the Marshalls. Prewar plans called principally for extensive mine-laying to deny the atolls to United States forces, but the effectiveness of medium bombers during the war against the Chinese had indicated that similar planes based on atolls could be a grave threat to shipping. A survey showed that the best sites for air bases were Wotje, Maloelap, Majuro, Mille, and Kwajalein. This last atoll, now the target of the American expeditionary force, was selected as administrative and communications center for the Marshalls area.

During 1941, the 6th Base Force and the 24th Air Squadron of the Fourth Fleet51 were made responsible for defending the islands. The base force immediately set to work building gun emplacements and other structures at Kwajalein, Wotje, Maloelap, and Jaluit. By December 1941, the various projects were nearly complete, and the Japanese forces employed against the Gilberts and Wake Island were able to operate from the Marshalls.52

The number of troops assigned to the Marshalls grew throughout 1942, but the islands themselves began to diminish in strategic importance. Japanese planners came to regard the Marshalls, like the Gilberts, as outposts to protect the more important Carolines and Marianas. Although the Imperial Navy began, in the fall of 1943, to speed work on the defenses of the Carolines and Marianas, the Marshalls were not neglected. If attacked, the outlying atolls were to hold out long enough for naval forces and aircraft to arrive on

the scene and destroy the American warships and transports. These were the same tactics that had failed in the Gilberts.53

Late in 1943, large numbers of Army troops began arriving in the Marshalls, and by the end of that year 13,721 men of the 1st South Seas Detachment, 1st Amphibious Brigade, 2nd South Seas Detachment, and 3rd South Seas Detachment were stationed on atolls in the group, on nearby Wake Island, and at Kusaie. Of these units, only the 1st South Seas Detachment had seen combat. Its men had been incorporated into the 122nd Infantry Regiment and had fought for three months on Bataan Peninsula during the Japanese conquest of the Philippines.

The enemy also sent the 24th Air Flotilla to the threatened area. This fresh unit served briefly under the 22nd Air Flotilla already in the area, but at the time of the first preparatory carrier strikes, the remaining veteran pilots of the 22nd were withdrawn and their mission of defending the Marshalls handed over to the newcomers.54 As the Kwajalein operation drew nearer, progressively fewer Japanese planes were able to oppose the aerial attacks. By 31 January, American pilots had won mastery of the Marshalls skies.

At Roi-Namur, principal objective of the 4th Marine Division, was the headquarters of the 24th Air Flotilla, commanded by vice Admiral Michiyuki Yamada, who had charge of all aerial forces in the Marshalls. The enemy garrison was composed mainly of pilots, mechanics, and aviation support troops, 1,500-2,000 in all. Also, there were between 300 and 600 members of the 61st Guard Force, and possibly more than 1,000 laborers, naval service troops, and stragglers.55 Only the men of the naval guard force were fully trained for ground combat.

In preparing the defenses of Roi-Namur, the enemy concentrated his weapons to cover probable landing areas, an arrangement in keeping with his goal of destroying the Americans in the water and on the beaches. The defenders, however, failed to take full advantage of the promontories on the lagoon shores of both Roi and Namur, sites from which deadly flanking fire might have been placed on the incoming landing craft. Both beach and antitank obstacles were comparatively few in number, although a series of antitank ditches and trenches extended across the lagoon side of Namur Island.56 Ten pillboxes mounting 7.7-mm machine guns, a 37-mm rapid-fire gun, a pair of 13-mm machine guns, and two 20-mm cannon were scattered along the beaches over which General Schmidt intended to land. Most of these positions were connected by trenches. Although two pair of twin-mounted 127-mm guns were emplaced on Namur, these weapons covered the

ocean approaches to the island. The enemy had no integrated defenses within the coastal perimeter, but he could fight, on Namur at least, from a myriad of concrete shelters and storage buildings. (See Map V.)

Kwajalein Island was the headquarters of Rear Admiral Monzo Akiyama’s 6th Base Force,57 and its garrison was stronger in ground combat troops than that at Roi-Namur. About 1,000 soldiers, most of them from the Army 1st Amphibious Brigade, fewer than 500 men of the Navy 61st Guard Force, and a portion of a 250-man detachment from the Special Naval Landing Force were the most effective elements of the defense force. A few members of the base force headquarters and a thousand or more laborers also were available. In the southern part of the atoll, the enemy had some 5,000 men, fewer than 2,000 of them skilled combat troops.

The defenses on Kwajalein Island, like those on Roi-Namur, lacked depth and were strongest along the ocean coast. The western end of Kwajalein Island, where General Corlett planned to land, was guarded by 4 twin-mounted 127-mm guns (weapons emplaced to protect the northwest corner of the island), 10 pillboxes, 9 machine gun emplacements, and a few yards of trenches. The cross-island defenses noted in aerial photographs actually consisted of an antitank ditch, a trench system, and seven machine gun positions. The trenches, though, began near a trio of 80-mm guns that were aimed seaward. Although he had few prepared positions in the interior of the island, there were hundreds of buildings from which the enemy might harry the attackers.

Both of the principal objectives were weak in comparison to Betio Island. Few obstacles protected the assault beaches, and work on many installations was not yet finished. In spite of these deficiencies, the soldiers and Marines could expect bitter fighting. “When the last moment comes,” vowed one of the atoll’s defenders, “I shall die bravely and honorably.”58 In happy contrast to Kwajalein Atoll was Majuro, where a Navy warrant officer and a few civilians had been left behind when the Japanese garrison was withdrawn.59