Part IV: Saipan: The Decisive Battle

Blank page

Chapter 1: Background to FORAGER1

Strategic and Tactical Plans

While the Japanese bolstered their defenses along the Central Pacific Front, American strategists were concluding their lengthy debate concerning the future course of the Pacific war. At the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, the CCS had accepted in principle a Central Pacific offensive aimed toward the general area of the Philippines but proceeding by way of the Marshalls, Carolines, and Marianas. In spite of objections by General MacArthur, this proposed offensive was finally incorporated in the Strategic Plan for the Defeat of Japan, with the seizure of the Marshalls and Carolines listed among the Allied goals for 1943-1944. Overall strategy against Japan called for two coordinated drives, one westward across the Central Pacific and the other, by MacArthur’s forces, northward from New Guinea.

The Importance of the Marianas2

The staunchest advocate of operations against the Marianas was

Admiral King, who believed that the capture of these islands would sever the enemy’s lines of supply to Truk and Rabaul and provide bases for operations against targets farther west. During the Quebec meeting of Anglo-American planners, a conference that lasted from 14 to 24 August 1943, the admiral again stressed the importance of the Marianas. British representatives asked King if it might not be wise to restrict operations in MacArthur’s theater so that the Allies might divert to Europe some of the men and material destined for the Southwest Pacific. The admiral answered that “if forces were so released they should be concentrated on the island thrust through the Central Pacific.”3 He added, however, that he considered the two offensives against the Japanese to be complementary. General Marshall then pointed out that the troops scheduled for the New Guinea operations were either en route to or already stationed in the Southwest Pacific.

At Quebec the CCS approved the forthcoming operations against the Gilberts and Marshalls but merely listed the Marianas as a possible objective to be attacked, if necessary, when American forces had advanced to within striking distance. The American Joint Planning Staff, acting upon this tentative commitment, began preparing an outline plan for the conquest of the Marianas. When Admiral Nimitz turned his attention to the Central Pacific drive approved at Quebec, he noted that the Marianas might serve as an alternate objective to the Palaus. In brief, amphibious forces might thrust to the Philippines by way of the Carolines and Palaus or strike directly toward the heart of the Japanese empire after seizing bases in the Marianas and Bonins. The agreements reached at Quebec also affected General MacArthur’s plans, for the Allies gave final acceptance to the JCS recommendation that Rabaul should be bypassed. This decision, although it changed the general’s plans, actually enabled him to speed his own advance toward the Philippines. (See Map I.)

As the next meeting of the Anglo-American Chiefs of Staff, scheduled for November 1943, drew nearer, the JCS began preparing its proposals for the future conduct of the Pacific war. Among the items under discussion was the employment of a new long-range bomber, the B-29, against Japanese industry. This plane, according to General Henry H. Arnold, Commanding General, Army Air Forces, “would have an immediate and marked effect upon the Japanese and if delivered in sufficient quantities, would undoubtedly go far to shorten the war.”4

At this time, Arnold was planning to strike from bases on the Chinese mainland,

an undertaking which required new flying fields, a vast amount of fuel and supplies, numerous American flight crews, mechanics, and technicians, and a strengthening of the Chinese Nationalist armies defending the bases. The large airfield nearest Japan was at Chengtu, 1,600 miles from any worthwhile target. If necessary, the B-29’s, loaded with extra gasoline instead of high explosives, could take off from India, fly to advanced airfields in China where the emergency fuel tanks could be replaced with bombs, then continue to the Japanese home islands. Unfortunately, the Chinese might prove incapable of holding these way-stations on the aerial road to Japan. What was needed were bases secure from enemy pressure but within range of the Home Islands. The solution lay in the Marianas, some 1,200 miles from the Japanese homeland, but this group was in the hands of the enemy. Army Air Force planners urged that the Marianas be captured and developed as B-29 bases, but they also desired to begin the strategic bombing of Japan as quickly as possible, using the India-China route.5

General Arnold was confident that masses of B-29s could destroy Japan’s “steel, airplane, and other factories, oil reserves, and refineries,” which were concentrated in and around “extremely inflammable cities.”6 His colleagues, already looking ahead to the invasion of Japan, apparently shared his conviction, for they accepted as a basis for planning the assumption, set forth by Vice Admiral Russell Willson, that: “If we can isolate Japan by a sea and air blockade, whittle down her fleet, and wipe out her vulnerable cities by air bombardment, I feel that there may be no need for invading Japan—except possibly by an occupying force against little or no opposition—to take advantage of her disintegration.”7

The importance attached to strategic bombardment and naval blockade caused the Marianas to assume an increasing significance in American plans, since submarines as well as aircraft might operate from the island group. Evidence of the value of the Marianas was the recommendation by the Strategy Section to the Strategy and Policy Group of the Army Operations Division that the island bases, once they were ready for operations, should have priority over the mainland fields in the allotment of aircraft. “It is self-evident,” Army strategists remarked, “that these aircraft should operate from bases within striking range of Japan proper, if that is possible, rather than from a more distant base such as Chengtu.”8 Throughout SEXTANT, as the latest international meeting was called, the United States emphasized the need for air bases in the western Pacific.

The SEXTANT conference, 22

November-7 December 1943, actually was a series of discussions among Allied leaders. After conversations with Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek at Cairo, President Roosevelt, Prime Minister Churchill, and their advisors journeyed to Teheran, Iran, where they met a Soviet staff led by Marshal Joseph Stalin. The Anglo-American contingent then returned to Cairo so that the combined staffs might revise their world-wide strategy to include commitments made to either Nationalist China or the Soviet Union.

Out of SEXTANT came a schedule, drafted for planning purposes, which called for the invasion of the Marianas on 1 October 1944 and the subsequent bombing by planes based in the islands of targets in and near the Japanese home islands. The date of the Marianas operation, however, might be advanced if the Japanese fleet were destroyed, if the enemy began abandoning his island outposts, if Germany suddenly collapsed, or if Russia entered the Pacific war. The strategy behind this timetable called for two series of mutually supporting operations, one by MacArthur’s troops, and the other by Nimitz’ Central Pacific forces. Since the advance across the Central Pacific promised the more rapid capture of airfields from which to attack Japan and could result in a crushing defeat for the Japanese navy, Nimitz would have priority in men and equipment. The timing of MacArthur’s blows would depend upon progress in the Central Pacific. Planners believed that by the spring of 1945 both prongs of the American offensive would have penetrated deeply enough into the enemy’s defenses to permit an attack in the Luzon-Formosa-China area.

On 27 December, area planning began as Nimitz issued his GRANITE campaign plan, a tentative schedule of Central Pacific operations which also helped to establish target dates for landings in the Southwest Pacific that would require support by the Pacific Fleet. First would come FLINTLOCK, scheduled for 31 January 1944, then the assault on Kavieng, 20 March, which would coincide with an aerial attack on Truk. On 20 April, MacArthur’s troops, supported by Nimitz’ warships, would swarm ashore at Manus Island. The fighting would then shift to the Central Pacific for the Eniwetok assault, then set for 1 May, the landing at Mortlock (Nomoi) 1 July, and the conquest of Truk to begin on 15 August. The tentative target date for the Marianas operation, which included the capture of Saipan, Tinian, and Guam, was 15 November 1944.

As if to prove that his GRANITE plan was more flexible than the mineral for which it was named, the admiral on 13 January advanced the capture of Mortlock and Truk in the Carolines, to 1 August. If these two landings should prove unnecessary, the Palau Islands to the west could serve as an alternate objective. From the Palaus, the offensive would veer northeastward to the Marianas, where the assault troops were to land on 1 November. Late in January 1944, Nimitz summoned representatives from the South Pacific and invited others from the Southwest Pacific to confer with his own staff officers on means of further speeding the war against Japan.

Nimitz, informed of the recent decisions

concerning B-29 bases, offered the conference a choice between storming Truk on 15 June, attacking the Marianas in September, and then seizing the Palaus in November or bypassing Truk, striking at the Marianas on 15 June, and then landing in the Palaus during October. Some of those present, however, were interested in neither alternative. The leader of these dissenters was General George C. Kenney, commander of Allied air forces in General MacArthur’s theater, who managed to convince various Army and Navy officers that the Central Pacific campaign be halted in favor of a drive northward from New Guinea to the Philippines. As Kenney recalled these sessions, he remarked that “we had a regular love feast. [Rear Admiral Charles H.] McMorris, Nimitz’ Chief of Staff, argued for the importance of capturing the Carolines and the Marshalls [FLINTLOCK was about to begin], but everyone else was for pooling everything along the New Guinea-Philippines axis.”9 Although fewer than Kenney’s estimated majority were willing to back a single offensive under MacArthur’s leadership, a sizeable number of delegates wanted to bypass the Marianas along with Truk. Nimitz, however, brought the assembled officers back to earth by pointing out that the fate of the Marianas was not under discussion. When reminded that the choice lay between neutralizing or seizing Truk before the advance into the Marianas, they chose to bypass the Carolines fortress.

General MacArthur also saw no strategic value in an American conquest of the Marianas. He dispatched an envoy to Washington to urge that the major effort against Japan be directed by way of New Guinea and the Philippines. Like those who dissented during Nimitz’ recent conference, the general’s representative accomplished nothing, for the JCS had reached its decision.

On 12 March, the JCS issued a directive that embodied the decisions made during the recent Allied conferences. General MacArthur’s proposed assault on Kavieng was cancelled, and the New Ireland fortress joined Rabaul on the growing list of bypassed strongholds. Southwest Pacific forces were to seize Hollandia, New Guinea, in April and then undertake those additional landings along the northern coast of the island which were judged necessary for future operations against the Palaus or Mindanao. This revision in the tasks to be undertaken in the South and Southwest Pacific enabled the Army general to return to Nimitz the fleet units borrowed for the Kavieng undertaking.

In the Central Pacific, where amphibious forces had seized Kwajalein and Eniwetok Atolls and carrier task groups had raided Truk, Nimitz was to concentrate upon targets in the Carolines, Palaus, and Marianas. His troops were scheduled to attack the Marianas on 15 June, while aircraft continued to pound the bypassed defenders of Truk. In addition, the admiral had the responsibility of protecting General MacArthur’s flank during the attack upon Hollandia and

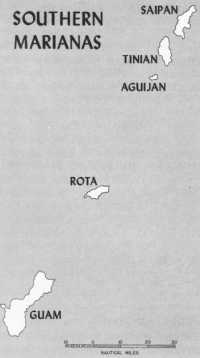

Map 14: Southern Marianas

subsequent landings. Throughout these operations, the two area commanders would coordinate their efforts to provide mutual support.

Although the Marianas lacked protected anchorages, a fact which Nimitz had pointed out to the JCS, these islands were selected as the next objective in the Central Pacific campaign. The major factor that influenced American planners was the need for bases from which B-29s could bomb the Japanese homeland. Instead of seizing advance bases for the fleet, the mission which the Marine Corps had claimed at the turn of the century, Leathernecks would be employed to capture airfield sites for the Army Air Forces.

After receiving the JCS directive, Nimitz ordered his subordinates to concentrate upon plans for the Marianas enterprise and to abandon the staff work that had been started in preparation for an assault on Truk. On 20 March, the admiral issued a joint staff study for FORAGER, the invasion of the Marianas. The purpose of this operation was to capture bases from which to sever Japanese lines of communication, support the neutralization of Truk, begin the strategic bombing against the Palaus, Philippines, Formosa, and China. Target date for FORAGER was 15 June.

The decision to bypass Truk and Kavieng enabled Admiral Nimitz to alter the established schedule for the Central Pacific offensive. The revised campaign plan, GRANITE II, called for the capture of Saipan, Guam, and Tinian in the Marianas, to be followed on 8 September by landings at Palau. Southwest Pacific Area forces were to invade Mindanao on 15 November.

The final Central Pacific objective, with a tentative target date of 15 February 1945, would be either southern Formosa and Amoy or the island of Luzon. Not until October 1944 did the JCS officially cancel the Formosa-Amoy scheme, an operation that would have required five of six Marine divisions, in favor of the reconquest of Luzon. The first of the Marianas Islands scheduled for conquest was Saipan. This objective was, in a military as well as a geographic sense, the center of the

group. Ocean traffic destined for the Marianas bases generally was channeled through Saipan. There, also, were the administrative headquarters for the entire chain, a large airfield and supplementary flight strip, as well as ample room for the construction of maintenance shops and supply depots. Finally, Saipan could serve as the base from which to attack Tinian, only three miles to the southwest, the island which had the finest airfields in the area. From Saipan, artillery could dominate portions of Tinian, but the western beaches of the northern island were beyond the range of batteries on Tinian. Thus, to strike first at Saipan was less risky than an initial blow at the neighboring island. Once the Americans had captured Saipan, Tinian, and Guam, the Japanese base at Rota would be isolated and subject to incessant aerial attack. (See Map 14. )

Saipan: The First Objective10

The Mariana group is composed of 15 islands scattered along the 145th meridian, east longitude. The distance from Farallon de Pajaros at the northern extremity of the chain to Guam at its southern end is approximately 425 miles. Since the northern islands are little more than volcanic peaks that have burst through the surface of the Pacific, only the larger of the southern Marianas are of military value. Those islands that figured in American and Japanese plans were Saipan, some 1,250 miles from Tokyo, Tinian, Rota, and Guam.

Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese explorer sailing for Spain, discovered the Marianas in 1521. The sight of Chamorros manning their small craft so impressed the dauntless navigator that he christened the group Islas de las Velas Latinas, Islands of the Lateen Sails, in tribute to native seamanship. His sailors, equally impressed but for a different reason, chose the more widely accepted name Islas de los Ladrones, Islands of the Thieves. Possibly moved by this latter title to reform the Chamorros, Queen Maria Anna dispatched missionaries and soldiers to the group, which was retitled in her honor the Marianas.

All of these islands were Spanish possessions at the outbreak of war with the United States in 1898. During the summer of that year, an American warship accepted the surrender of Guam, a conquest that was affirmed by the treaty that ended the conflict. In 1899, the remaining islands were sold to Germany as Spain disposed of her Pacific empire. Japan seized the German Marianas during World War I. After the war, the League of Nations appointed Japan as trustee over all the group except American-ruled Guam. When Japan withdrew from the League of Nations in 1935, she retained her portion of the Marianas as well as the Marshalls and Carolines. In the years that followed, the Japanese government

kept its activities in the group cloaked in secrecy.

No single adjective can glibly describe the irregularly shaped island of Saipan. Three outcroppings, Agingan Point, Cape Obiam, and Nafutan Point, mar the profile of the southern coast. The western shoreline of Saipan extends almost due north from Agingan Point past the town of Charan Kanoa, past Afetna Point and the city of Garapan to Mutcho Point. Here, midway along the island, the coastline veers to the northeast, curving slightly to embrace Tanapag Harbor and finally terminating at rugged Marpi Point. The eastern shore wends its sinuous way southward from Marpi Point, beyond the Kagman Peninsula and Magicienne Bay, to the rocks of Nafutan Point. Cliffs guard most of the eastern and southern beaches from Marpi Point to Cape Obiam. There is a gap in this barrier inland of Magicienne Bay, but a reef, located close inshore, serves to hinder small craft. Although the western beaches are comparatively level, a reef extends from the vicinity of Marpi Point to an opening off Tanapag Harbor, then continues, though broken by several gaps, to Agingan Point. (See Map 15.)

Saipan encompasses some 72 square miles. The terrain varies from the swamps inland of Charan Kanoa to the mountains along the spine of the island and includes a relatively level plain. The most formidable height is 1,554-foot Mount Tapotchau near the center of the island. From this peak, a ridge, broken by other mountain heights, runs northward to 833-foot Mount Marpi. To the south and southeast of Mount Tapotchau, the ground tapers downward to form a plateau, but the surface of this plain is broken by scattered peaks. Both Mounts Kagman and Nafutan, for example, rise over 400 feet above sea level, while Mount Fina Susu, inland of Charan Kanoa, reaches almost 300 feet. The most level regions—the southern part of the island and the narrow coastal plain—were under intense cultivation at the time of the American landings. The principal crop was sugar cane, which grew in thickets dense enough to halt anyone not armed with a machete. Refineries had been built at Charan Kanoa and Garapan, and rail lines connected these processing centers with the sugar plantations.

Saipan weather promised to be both warm, 75 to 85 degrees, and damp, for the invasion was scheduled to take place in the midst of the rainy season. Planners, however, believed that the operation would end before August, usually the wettest month of the year. Typhoons, which originate in the Marianas, posed little danger to the expedition for such storms generally pass beyond the group before reaching their full fury.

As American strategists realized, Saipan offered no harbor that compared favorably with the atoll anchorages captured in previous operations. The Japanese had improved Tanapag Harbor on the west coast, but there the reef offered scant protection to anchored vessels. Ships which chose to unload off Garapan, just to the south, were at the mercy of westerly winds. The deep waters of Magicienne Bay, on the opposite shore, were protected on the north and west but exposed to winds from the southeast.

The geography of the objective influenced both planning and training. The size of the island, the reefs and cliffs that guarded its coasts, its cane fields and mountains, and the disadvantages of its harbors had to be considered by both tactical and logistical planners. Whatever their schemes of maneuver and supply, the attackers would encounter dense cane fields, jungles, mountains, cities or towns, and possibly swamps. The Marines would have to prepare to wage a lengthy battle for ground far different from the coral atolls of the Gilberts and Marshalls.

Command Relationships

Since FORAGER contemplated the eventual employment of three Marine divisions, a Marine brigade, and two Army divisions against three distinct objectives within the Mariana group, the command structure was bound to be somewhat complex. Once again, Admiral Nimitz, who bore overall responsibility for the operation, entrusted command of the forces involved to Admiral Spruance. As Commander, Central Pacific Task Forces, Spruance held military command of all units involved in FORAGER and was responsible for coordinating and supervising their performance.11 He was to select the times of the landings at Tinian, Guam, and any lesser islands not mentioned in the operation plan and to determine when the capture and occupation of each objective had been completed. As Commander, Fifth Fleet, he also had the task of thwarting any effort by the Combined Fleet to contest the invasion of the Marianas.

Vice Admiral Turner, Commander, Joint Amphibious Forces (Task Force 51), would exercise command over the amphibious task organizations scheduled to take part in FORAGER. The admiral, under the title of Commander, Northern Attack Force, reserved for himself tactical command over the Saipan landings. As his second-in-command, and commander of the Western Landing Group, which comprised the main assault forces for Saipan, Turner had the veteran Admiral Hill.12 At both Tinian and Guam, Turner would exercise his authority through the appropriate attack force commander.

In command of all garrison troops as well as the landing forces was Holland M. Smith, now a lieutenant general. Smith, Commanding General, Expeditionary Troops, also served as Commanding General, Northern Troops and Landing Force (NTLF) at Saipan. As commander of the expeditionary troops, he exercised authority through the landing force commander at a given objective from the time that the amphibious phase ended until the capture and occupation phase was completed. Thanks to his dual capacity at Saipan, the general would establish his command post ashore when he believed the beachhead to be secured, report this move to the attack force commander, and begin directing the battle for the island. Since Saipan was a large enough land mass to require a 2-division

landing force, Smith would be the equivalent of a corps commander.

Faced with the burdens of twin commands, the Marine general reorganized his VAC staff as soon as the preliminary planning for the Marianas operation had been completed. For detailed planning, he could rely on a Red Staff, which was to assist him in exercising command over Northern Troops and Landing Force, and a Blue Staff, which would advise him in making decisions as Commander, Expeditionary Troops.

Apart from his role in FORAGER, Smith was charged, in addition, with “complete administrative control and logistical responsibility for all Fleet Marine Force units employed in the Central Pacific Area.”13 Since all Marine divisions in the Pacific were destined for eventual service in Nimitz’ theater, the general was empowered to establish an administrative command which included a supply service. Once the Marianas campaign was completed, Nimitz intended to install Smith as Commanding General, Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, with control over the administrative command and two amphibious corps.14

Northern Troops and Landing Force was composed of two veteran divisions led by experienced commanders. The 2nd Marine Division, which had earned battle honors at Guadalcanal and Tarawa, was now commanded by Major General Thomas E. Watson, whose Tactical Group 1 had seized Eniwetok Atoll. Major General Harry Schmidt’s 4th Marine Division had received its introduction to combat during FLINTLOCK. The second major portion of Expeditionary Troops, Southern Troops and Landing Force, was under the command of Major General Roy S. Geiger, a naval aviator, who had directed an amphibious corps during the Bougainville fighting. Geiger’s force consisted of the 3rd Marine Division, tested at Bougainville, and the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade. The brigade boasted the 22nd Marines, a unit that had fought valiantly at Eniwetok Atoll, and the 4th Marines. Although the 4th Marines, organized in the South Pacific, had engaged only in the occupation of Emirau Island, most of its men were former raiders experienced in jungle warfare.

During the interval between the Kwajalein and Saipan campaigns, the Marine Corps approved revised tables of organizations for its divisions and their components, a decision which affected both the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions. Aggregate strength of the new model division was 17,465, instead of the previous 19,965. The principal components now were a headquarters battalion, a tank battalion, service troops, a pioneer battalion, an engineer battalion, an artillery regiment, and three infantry regiments. Service troops included service, motor transport, and medical battalions; the component once designated “special troops” existed no longer. The new tables called for the elimination of the naval construction battalion that had been part of the discarded engineer regiment and the transfer of the scout company,

now reconnaissance company, from the tank battalion to headquarters battalion. The artillery regiment was deprived of one of its 75-mm pack howitzer battalions, leaving two 75-mm and two 105-mm howitzer battalions. The infantry regiments continued to consist of three infantry battalions and a weapons company. The old 12-man rifle squad was increased to a strength of 13 and divided into three 4-man fire teams. Finally, the special weapons battalion had been disbanded and its antitank duties handed over to the regimental weapons companies, while the amphibian tractor battalion was made a part of corps troops.

Except for the absence of LVTs, the most striking change in the revised division’s equipment was the substitution of 46 medium tanks for 54 light tanks within the tank battalion. The authorized number of flamethrowers had been gradually increased from 24 portables to 243 of this variety plus 24 of a new type that could be mounted in tanks, thus giving official approval to the common practice of issuing prior to combat as many flamethrowers as a division could lay hands upon. The artillery regiment lost 12 75-mm pack howitzers, but the number of mortars available to infantry commanders was increased from 81 60-mm and 36 81-mm to 117 60-mm and 36 81-mm. Since each of the newly authorized fire teams contained an automatic rifle, the new division boasted 853 of these weapons and 5,436 M1 rifles instead of 558 automatic rifles and 8,030 M1s. Although it would seem that the reorganized division could extract a greater volume of fire from fewer men, such a unit also would require reinforcements, notably a 535-man amphibian tractor battalion, before attempting amphibious operations.15

Both Marine divisions scheduled for employment at Saipan were almost completely reorganized before their departure for the objective. Neither had disbanded its engineer regiment although the organic naval construction battalions were now attached and would revert to corps control after the landing.16 The two surviving Marine battalions were originally formed according to discarded tables of organization as pioneer and engineer units. Thus, they could perform their usual functions even though they remained components of a regiment rather than separate battalions. Reinforced for the Saipan landings, its infantry battalions organized as landing teams and its infantry regiments as combat teams, each of the two divisions numbered approximately 22,000 men.17 In contrast, the 27th Infantry Division, serving as FORAGER reserve, could muster only 16,404 officers and men when fully reinforced.

During the battle for Saipan, the attacking Marines would be supported by heavier artillery weapons than the 75-mm and 105-mm howitzers that had aided them in previous Central Pacific operations. Two Army 155-mm

howitzer battalions joined a pair of Army 155-mm gun battalions to form XXIV Corps Artillery under command of Brigadier General Arthur M. Harper, USA. In addition, a Marine 155-mm howitzer battalion was attached by VAC to the 10th Marines, artillery regiment for the 2nd Marine Division. The 4th Marine Division, however, had to be content with an additional 105-mm howitzer battalion. The remainder of VAC artillery was retained under corps control in Hawaii.18

Another division which might see action at Saipan was the FORAGER reserve, the 27th Infantry Division, an organization that had yet to fight as a unit. During GALVANIC, the division commanding general, Major General Ralph C. Smith, had led the 165th Infantry and 3/105 against enemy-held Makin Atoll. As part of Tactical Group 1, 1/106 and 2/106 had fought at Eniwetok Island. The remaining battalion of the 106th Infantry landed at Majuro where there was no opposition, and the other two battalions of the 105th Infantry lacked combat experience of any sort. Also in reserve was the inexperienced 77th Infantry Division, but this unit would remain in Hawaii as a strategic reserve until enough ships had returned from Saipan to carry it to the Marianas. Not until 20 days after the Saipan landings would the 77th Division become available to Expeditionary Troops for employment in the embattled islands.

The effort against Saipan, then, rested in capable hands. The team of Spruance, Turner, and Holland Smith had worked together in the Gilberts and Marshalls. Both assault divisions were experienced and commanded by generals who had seen previous action in the Pacific war. Only the Expeditionary Force reserve, which might be employed at Saipan, was an unknown factor, for the various components of the 27th Infantry Division had not fought together as a team, and there was considerable difference in experience among its battalions.

Logistical and Administrative Planning19

In attacking Saipan, Nimitz’ amphibious forces would encounter an objective unlike any they seized in previous Central Pacific operations. The mountainous island, with a total land area of some 72 square miles, was a far different battleground from the small, low-lying coral atolls of the Gilberts and Marshalls. The capture of this limited land mass could not be accomplished at a single stroke, a fact that was reflected in the plan of resupply adopted at the urging of General Holland Smith. The assault forces were directed to carry a 32-day supply of rations, enough fuel, lubricants,

chemical, ordnance, engineer, and individual supplies to last for 20 days, a 30-day quantity of medical supplies, 7 days’ ammunition for ground weapons, and a 10-day amount for antiaircraft guns.

Vast as this mountain of supplies might be, the Commanding General, Expeditionary Troops, wanted still more. The Navy accepted his recommendations that an ammunition ship anchor off Saipan within five days after the landings and that supply vessels sailing from the continental United States be “block loaded.” In other words, those ships that would arrive with general supplies after the campaign had begun should carry items common to all troop units in a sufficient quantity to last 3,000 men for 30 days. The portion of the plan dealing with ammunition resupply worked well enough, but block loading proved inefficient. Since the blocks had been loaded in successive increments, each particular item had to be completely unloaded before working parties could reach the next type of supplies. Admiral Turner later urged a return to the practice of loading resupply vessels so that the various kinds of cargo could be landed as needed. He saw no need in forcing many ships to carry a little bit of everything, when, by concentrating certain items in different ships, selective unloading was possible.

As usual, hold space was at a premium, so Expeditionary Troops kept close watch on the amount of equipment carried by assault and garrison units. The three divisions that figured in the Saipan plan adhered to the principles of combat loading, but only one, the 27th Infantry Division, made extensive use of pallets. In fact, the Army unit exceeded the VAC dictum that from 25 to 50 percent of embarked division supplies be placed on pallets. The 2nd Marine Division lashed about 25 percent of its bulk cargo to these wooden frames, while the 4th Marine Division placed no more than 15 percent of its supplies on pallets. General Schmidt’s unit lacked the wood, waterproof paper, and skilled laborers necessary to comply with the wishes of corps. To complicate the 4th Marine Division loading, G-4 officers found that certain vessels assigned to carry cargo for Schmidt’s troops were also to serve other organizations. In addition, the transports finally made available had less cargo space than anticipated. Under these circumstances, division planners elected to use every available cubic foot for supplies, vehicles, and equipment. Even if material had been available, there would have been room for few pallets.

Applying the lessons of previous amphibious operations, VAC addressed itself to the problems of moving supplies from the transports to the units fighting ashore. In April 1944, a Corps Provisional Engineer Group was formed, primarily to provide shore party units for future landings. The two Marine Divisions assigned to VAC for FORAGER had already established slightly different shore party organizations, but since both were trained in beachhead logistics, the engineer group did not demand that they be remodeled to fit a standard pattern. Backbone of the shore parties for both divisions were the pioneer battalions and the attached naval construction battalions.

The 2nd Marine Division assigned pioneer troops as well as Seabees to each

shore party team, while the 4th Marine Division concentrated its naval construction specialists in support of a single regiment. If this construction battalion should be needed for road building or similar tasks, the 4th Marine Division would be forced to reorganize its shore party teams in the midst of the operation. Neither Marine division used combat troops to assist in the beachhead supply effort.

To support both the garrison and assault units assigned to FORAGER, the Marine Supply Service organized the 5th and 7th Field Depots.20 Marines trained to perform extensive repairs on weapons, fire control equipment, and vehicles accompanied the landing forces, while technicians capable of making even more thorough repairs embarked with the garrison troops. The 7th Field Depot was chosen to store and issue supplies, distribute ammunition, and salvage and repair equipment on both Saipan and Tinian. The 5th Field Depot would perform similar duties on Guam. At the conclusion of FORAGER, the two depots were to assist in re-equipping the 2nd and 3rd Marine Divisions by accepting, repairing, and re-issuing items turned in prior to their departure from the Marianas by the 4th Marine Division and 1st Provisional Marine Brigade. Since plans called for Saipan to be garrisoned primarily by Army troops, the 7th Field Depot eventually would move its facilities to nearby Tinian, although it would continue to serve Marine units on the other island.

Authority to determine which boats were to evacuate the wounded from Saipan rested in the beachmasters. During the early hours of the operation, casualties were to be collected in three specially equipped LSTs, treated, and then transferred to wards installed in certain of the transports. One of the hospital LSTs would take station off the beaches assigned to each of the Marine divisions. The third such vessel was to relieve whichever of the other two was first to receive 100 casualties. Each of the trio of landing ships had a permanent medical staff of one doctor and eight corpsmen. An additional 2 doctors and 16 corpsmen would be reassigned from the transports to each of the LSTs before the fighting began. Plans also called for hospital ships to arrive in the target area by D plus three or when ordered forward from Eniwetok by Admiral Turner. Detailed plans were also formulated for the air evacuation of severely wounded men from the Marianas. Planes of the Air Transport Command, Army Air Forces, would load casualties at Aslito airfield and fly them to Oahu via Kwajalein.21

In spite of the scope of the Saipan undertaking and the possibility of numerous casualties, no replacement drafts were included in the expedition, for G-1 planners believed that men transferred from one unit could replace those lost by another. During the Saipan fighting, the 2nd Marine Division

was to be kept at peak effectiveness by the reassignment of troops from the 4th Marine Division. This plan, however, had to be abandoned, for the mass transfers required under such an arrangement would have crippled General Schmidt’s division. Instead, replacement drafts were dispatched to Saipan during June and July.

Intelligence for Saipan

Until carrier planes attacked Saipan on 22-23 February 1944, American intelligence officers had no accurate information concerning the island defenses. As a result of these strikes, planners received aerial photographs of certain portions of the island. Ideal coverage, General Holland Smith’s G-2 section believed, could be obtained if photographic missions were flown 90, 60, 30, and 15 days before the Saipan landings. Unfortunately, Navy carrier groups were too busy blasting other objectives to honor such a request, but additional pictures were taken by long-range Navy photo planes. Between 17 April and 6 June, Seventh Air Force B-24s escorted their Navy counterpart PB4Ys from Eniwetok to the Marianas on seven joint reconnaissance missions.22 Although the final set of photographs reached Expeditionary Troops headquarters at Eniwetok, where the expedition had paused en route to the objective, the assault elements had already set sail for Saipan. As a result, the troops that landed on 15 June did not benefit from the final aerial reconnaissance. Equally useless to the attacking divisions were the photographs of the island beaches taken by the submarine Greenling, for these did not cover the preferred landing areas.

The aerial photographs taken by carrier aviators were not of the best quality, for the taking of pictures was more or less a sideline, and a dangerous one at that. First in the order of importance was the killing of Japanese, but the most profitable target for American bombs was not always the island or area which the intelligence experts wanted photographed. Admiral Spruance did for a time contemplate a second carrier strike against Saipan, a raid which would have netted additional photographs to supplement those taken in February by carrier aircraft and in April and May by Eniwetok-based photographic planes. In order to avoid disclosing the Marianas as the next American objective, the Admiral decided against the raid.

The photos obtained during the February raid along with charts captured in the Marshalls provided the information upon which Expeditionary Troops based its map of Saipan. Since the sources used did not give an accurate idea of ground contours, map makers had to assume that slopes were uniform unless shadows in the pictures indicated a sudden rise or sharp depression. Clouds, trees, and the angle at which the photos were taken helped hide the true nature of the terrain, so that many a cliff was interpreted on the map as a gentle slope. Fortunately, accurate Japanese maps were to be captured during the first week of fighting.

The strength, disposition, and armament of the Saipan garrison was difficult to determine. Documents

captured in previous campaigns, reports of shipping activity, and aerial photographs provided information on the basic strength, probable reinforcement, and fixed defenses of the garrison. As D-Day approached, Admiral Turner and General Smith obtained additional fragments of the Saipan jigsaw puzzle, but full details, such as the complete enemy order of battle, would not be known until prisoners, captured messages, and reports from frontline Marine units became available.

On 9 May, Expeditionary Troops estimated that no more than 10,000 Japanese were stationed at Saipan, but by the eve of the invasion, this figure had soared to 15,000-17,600. This final estimate included 9,100-11,000 combat troops, 900-1,200 aviation personnel, 1,600-1,900 Japanese laborers plus 400-500 Koreans, and 3,000 “home guards,” recent recruits who were believed to be the scrapings from the bottom of the manpower barrel. The actual number of Japanese was approximately 30,000 soldiers and sailors plus hundreds of civilians.

Although aerial photographs gave the landing force an accurate count of the enemy’s defensive installations, these pictures did not disclose the number of troops poised inland of the beaches. The number and type of emplacements, however, did indicate that reinforcements were pouring into the island. By comparing photos taken on 18 April with those taken on 29 May, intelligence experts discovered an increase of 30 medium antiaircraft guns, 71 light antiaircraft cannon or machine guns, 16 pillboxes, a dozen heavy antiaircraft guns, and other miscellaneous weapons.

Intelligence concerning Saipan was not as accurate as the information previously gathered for the Kwajalein campaign. The 1,000-mile distance of the objective from the nearest American base, the clouds which gathered over the Marianas at this time of year, and the fear of disclosing future plans by striking too often at Saipan were contributing factors. The lack of usable submarine photographs was offset by the possession of hydrographic charts seized in the Marshalls and by the boldness of underwater demolition teams. Under cover of naval gunfire, these units scouted the invasion beaches during daylight on D minus 1 to locate underwater obstacles.

Tactical Plans

Northern Troops and Landing Force was assigned the capture of both Saipan and adjacent Tinian. For these operations, service and administrative elements of the command were banded together in Corps Troops, while the combat elements were the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions, supported by XXIV Corps Artillery. One Marine infantry battalion, 1/2, was withdrawn from the 2nd Marine Division and placed under corps control for a special operation in connection with the Saipan landing. To replace this unit, General Watson was subsequently given the 1st Battalion, 29th Marines. This outfit, made up of drafts from the 2nd Division, was located at Hilo, Hawaii. After the campaign, 1/29 was destined to join the rest of its regiment at Guadalcanal and form part of the

6th Marine Division.23 In addition to the combat troops, NTLF also controlled two garrison forces, composed mainly of Army units for Saipan and Marine units for Tinian. The 27th Infantry Division, as Expeditionary Troops reserve, might be employed to reinforce Northern Troops and Landing Force at Saipan or Tinian, or to assist Southern Troops and Landing Force at Guam. As a result, the division G-3 section prepared 21 operation plans, 16 of them dealing with possible employment at Saipan.

The basic scheme of maneuver for the Saipan attack called for the 23rd and 25th Marines, 4th Marine Division, to land on the morning of 15 June over the Blue Beaches off the town of Charan Kanoa and across the Yellow Beaches, which extended southward from that town toward Agingan Point. At the same time, the 6th and 8th Marines, 2nd Marine Division, were to land on the Red and Green Beaches just north of Charan Kanoa. To deceive the enemy, General Smith decided to make a feint toward the coastline north of Tanapag Harbor, a maneuver which he assigned to the 2nd Marines, including 1/29, and the 24th Marines. (See Map 16.)

Another portion of the plan, one that eventually was canceled, would have sent 1/2 ashore near the east coast village of Laulau on the night of 14-15 June. This reinforced battalion was to have pushed inland to occupy the crest of Mount Tapotchau and hold that position until relieved by troops from the western beachhead. After this part of the plan had been abandoned, 1/2 remained ready to land on order at Magicienne Bay, or, if the tactical situation demanded, elsewhere on the island.

Striking inland, the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions were to seize the high ground that stretched southward from Hill 410 through Mount Fina Susu to Agingan Point. Since this high ground dominating the beaches had to be seized as rapidly as possible, the LVTs and their escorting LVT(A)s were to thrust toward the ridge line, bypassing pockets of resistance along the shore. From this terrain feature, General Schmidt’s division was to push eastward beyond Aslito Airfield to Nafutan Point, while General Watson’s Marines secured the shores of Magicienne Bay and attacked northward toward Marpi Point. Among the intermediate objectives of the 2nd Marine Division during this final advance were Mount Tipo Pale, Mount Tapotchau, and the city of Garapan.

The ship-to-shore movement that would trigger the battle for Saipan was patterned after earlier amphibious operations in the Marshalls. Because of the reef that guarded the landing sites, LVTs were required by the attacking Marines. Northern Troops and Landing Force had a total of six amphibian tractor battalions, three of them, the 2nd, 4th, and 10th, Marine units and the others, the 534th, 715th, and 773rd, Army organizations. The tractors assigned to the assault infantry battalions, as well as those assigned to one reserve battalion in each division, were ferried to Saipan in LSTs. Since the tank landing ships also carried the Marines assigned to land in these LVTs, relatively few assault

troops would be forced to transfer from one type of craft to another. All reserve infantry elements, except for the two battalions assigned to LSTs, were scheduled to proceed in LCVPs from their transports to a designated area where they would change to LVTs. The organic field artillery regiments of both divisions embarked their battalions in LSTs. The 75-mm howitzers and crews were to land in LVTs, and the 105s in DUKWs. Both types of weapons were placed in the appropriate vehicles before the expedition sailed. Tanks once again were preloaded in LCMs, and these craft embarked in LSDs.

The assault on Saipan would be led by rocket-firing LCI gunboats which were followed by armored amphibian tractors. The LVT(A)4s, manned by the Marine 2nd Armored Amphibian Tractor Battalion, were modifications of the type used in the Marshalls. Instead of a 37-mm gun and three .30 caliber machine guns, the new vehicles boasted a snub-nosed 75-mm howitzer mounted in a turret and a .50 caliber machine gun. The other unit assigned to the Saipan operation, the Army’s 708th Amphibian Tank Battalion, was equipped with older LVT(A)1s and a few LVT(A)4s.

To control the Saipan landings, Admiral Hill selected officers experienced in amphibious warfare. At the apex of the control pyramid was the force control officer, who had overall responsibility for controlling all landing craft involved in getting two divisions ashore on a frontage of some 6,000 yards.24 A group control officer was assigned each division, and a transport division control officer was in charge of each regiment in the landing force. On D-Day, the force control officer would, by means of visual signals and radio messages, summon the leading waves to the line of departure and dispatch them toward the island. Transport division control officers had the tasks of sending in the later waves according to a fixed schedule and of landing reserves as requested by the regimental commander or his representatives.

One LCC was stationed on either flank of the first wave formed by each assault regiment. These vessels were to set the pace for the amphibian tractors in addition to keeping those vehicles from wandering from course. When the initial wave crossed the reef, a barrier which the control craft could not cross, the LCCs would take up station seaward of that obstacle to supervise the transfer of reserve units from LCVPs to LVTs. Later assault waves would rely on designated LCVPs to guide them as far as the reef.

Since communications had been the key to control in previous operations, Admiral Turner decided to employ at Saipan 14 communications teams, each one made up of an officer, four radiomen, and two signalmen. In addition to placing these teams where he thought them necessary, the admiral had additional radio equipment installed in the patrol craft, submarine chasers, and LCCs that were serving as control vessels. In this way, adequate radio channels were available to everyone involved in controlling the landings, the supply effort, and the evacuation of casualties.

Air and Naval Gunfire Support

After Navy pilots based on fast carriers had destroyed Japanese air power in the Marianas, other aviators could begin operations designed to aid the amphibious striking force. Because of its size, Saipan imposed new demands upon supporting aircraft. Pilots assisting an attack against an atoll could concentrate on a relatively small area, but in their strikes against a comparatively large volcanic island, the aviators would have to range far inland to destroy enemy artillery and mortars which could not be reached by naval guns and to thwart efforts to reinforce coastal defense units. The neutralization of the beach fortifications was to follow a flexible schedule, while strikes against defiladed gun positions or road traffic could be launched as required by planes on station over the island.

The first D-Day attack against the beach defenses was a 30-minute bombing raid scheduled to begin 90 minutes before H-Hour. Naval gunfire would be halted while the planes made their runs. This strike was intended to demoralize enemy troops posted along the beaches as well as to destroy particular installations.

To make up for the absence of field artillery support, such as had been enjoyed in the Marshalls, aircraft were ordered to strafe the beaches while the incoming LVTs were between 800 and 100 yards of the island. This aerial attack would coincide in part with the planned bombardment by warships of this same area, for naval gunfire would not be shifted until the troops were 300 yards from the objective. Pilots were informed of the maximum ordinate of the naval guns, and since their shells followed a rather flat trajectory, the approach of the planes would not be seriously hindered. When the leading wave was 100 yards from its objective, the aviators were to shift their point of aim 100 yards inland and continue strafing until the Marines landed.

Prior to H-Hour, all buildings, suspected weapons emplacements, and possible assembly areas more than 1,000 yards from the coastline were left to the attention of naval airmen. Planes armed with bombs or rockets had the assignment of patrolling specific portions of Saipan to attack both previously located installations and targets of opportunity. After the landings, aircraft would cooperate with naval gunfire and artillery in destroying enemy strongpoints and hindering Japanese road traffic.

The air support plan also provided for the execution of strikes at the request of ground units. A Landing Force Commander Support Aircraft was appointed primarily to insure coordination between artillery and support aviation. A requested strike might be directed by any of four individuals: the Airborne Coordinator, aloft over the battlefield; the leader of the flight on station over the target area; the Landing Force Commander Support Aircraft with headquarters ashore; or the Commander Support Aircraft, located in the command ship and aware of the naval gunfire plan.

The decision whether to handle the strike himself or delegate it to another was left to the Commander Support Aircraft. He would select the person best informed on the ground situation

to direct a particular attack. He also had the responsibility of insuring that his subordinates were fully informed concerning troop dispositions and any plans to employ other supporting weapons.

The preliminary naval bombardment of Saipan was to begin on D minus 2 with the arrival off the objective of fast battleships and destroyers from Task Force 58. The seven battleships, directed to remain beyond the range of shore batteries and away from possible minefield, would fire from distances in excess of 10,000 yards. The nocturnal harassment of the enemy was left to the destroyers. On the following day, the fire support ships, cruisers, destroyers, and old battleships were scheduled to begin hammering Saipan from close range.

The plan for D-Day called for the main batteries of the supporting battleships and cruisers to pound the beaches until the first wave was about 1,000 yards from shore. The big guns would then shift to targets beyond the O-1 Line, which stretched from the northern extremity of Red 1 through Hill 410 and Mount Fina Susu to the vicinity of Agingan Point. Five-inch guns, however, were to continue slamming shells into the beaches until the troops were 300 yards from shore, when these weapons also would shift to other targets. The final neutralization of the coastal defenses was left to the low-flying planes which had begun their strafing runs when the LVTs were 800 yards out to sea.

During the fighting ashore, on-call naval gunfire was planned for infantry units. To speed the response to calls for fire support, each shore fire control party was assigned the same radio frequency as the ship scheduled to deliver the fires and the plane that observed the fall of the salvos. A Landing Force Naval Gunfire Officer was selected to go ashore and work with the Landing Force Commander Support Aircraft and the Corps Artillery Officer in guaranteeing cooperation among the supporting arms.