Chapter 3: Saipan: The First Day1

The final reports from underwater demolition teams were encouraging, for Kauffman’s men had found the reef free of mines and the boat lanes clear of obstacles, As dawn approached, the Americans noted that flags, probably planted after the underwater reconnaissance, dotted the area between the reef and the invasion beaches. These markers, intended to assist Japanese gunners in shattering the assault, were probably helpful to the troops manning the beach defenses, but the artillery batteries, firing from the island interior, were so thoroughly registered and boasted such accurate data that the pennants were unnecessary.2 Whatever their tactical value, the flags served as a portent of the fierce battle that would begin on the morning of 15 June.

Forming For the Assault

The transport groups carrying those members of the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions who had not been crammed into the LSTs took station off Saipan at 0520. Two transport divisions steamed toward Tanapag Harbor to prepare for the demonstration to be conducted by the 2nd and 24th Marines along with the orphaned battalion, 1/29. The other vessels, however, waited some 18,000 yards off Charan Kanoa. At 0542, Admiral Turner flashed the signal to land the landing force at 0830, but he later postponed H-Hour by 10 minutes.

The preparatory bombardment continued in all its fury as the LSTs approached Saipan and began disgorging their LVTs. Smoke billowed upward from the verdant island, but a short distance seaward, the morning sun, its rays occasionally blocked by scattered clouds, illuminated a gentle sea. Neither wind, waves, nor unforeseen currents impeded the launching of the tractors or the lowering of landing craft.

Nearest the beaches that morning were the two battleships, two cruisers, and six destroyers charged with the final battering of the defenses which the Marines would have to penetrate. Beyond these warships, some 5,500 yards from shore, the LSTs carrying the assault elements of both divisions paused to set free their amphibian tractors. Control craft marked by identifying flags promptly took charge of the LVTs and began guiding them into formation. Farthest out to sea were the landing ships that carried field artillery and antiaircraft units and the LSDs that had ferried to Saipan the tank battalions of both divisions.

As the landing craft swarmed toward the line of departure, their movement was screened by salvos from certain of the fire-support units. Other warships lashed out at those areas from which the enemy might fire into the flanks of the landing force. Agingan Point and Afetna Point shuddered under the impact of 14-inch shells, while to the north, the Maryland hurled 16-inch projectiles into Mutcho Point and Maniagassa Island. The naval bombardment halted as scheduled at 0700 for a 30-minute aerial attack. When the planes departed, Admiral Hill, the designated commander of the landing phase, assumed control of the fire support ships blasting the invasion beaches. The naval guns then resumed firing, raising a pall of dust and smoke that made aerial observation of the southwestern corner of Saipan almost impossible.3

At the line of departure, 4,000 yards from the smoke-shrouded beaches, 96 LVTs, 68 armored amphibian tractors, and a dozen control vessels were forming the first wave. These craft were posted to the rear of a line of 24 LCI gunboats. The remaining waves formed seaward of the line of departure to await the signal to advance toward the dangerous shores. Beyond the lines of tractors, the boats carrying reserve units maneuvered into position for their journey to the transfer area just outside the reef, where they would be met by tractors returning from the beaches. The LSTs assigned to the artillery units prepared to launch their DUKWs and LVTs, while the tank-carrying LCMs got ready to wallow forth from the LSDs. The control boats organizing these final waves rode herd on their charges to insure that the beachhead, once gained, could be rapidly reinforced.

At 0812, the first wave was allowed to slip the leash and lunge, motors roaring, toward shore. Ahead of these LVTs were the LCI(G)s which would pass through the line of supporting warships to take up the hammering of the beaches. Within the wave itself, armored amphibians stood ready to thunder across the reef and then begin their own flailing of the beaches. Overhead were the aircraft selected to make the final strike against the shoreline.

To the left of Afetna Point, looking inland from the line of departure,

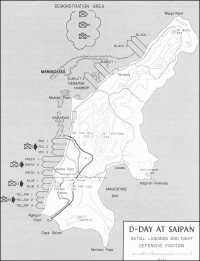

Map 16: D-Day at Saipan

General Watson’s 2nd Marine Division, two regiments abreast, surged toward the Red and Green Beaches. Farthest left was the 6th Marines, commanded by Colonel James P. Riseley. The assault battalions of the regiment were to storm two 600-yard segments of the coast labeled Red 2 and Red 3. On Riseley’s flank, beyond a 150-yard gap, was Colonel Clarence R. Wallace’s 8th Marines, also landing on a 1,200-yard, two-battalion front. Included in the 8th Marines zone, divided into Beaches Green 1 and 2, was the northern half of Afetna Point. To the right of General Watson’s troops lay 800 yards of comparatively untroubled ocean, but off Charan Kanoa the seas were churned white by the LVTs carrying General Schmidt’s 4th Marine Division. Next to the gap, within which two fire-support ships were rifling high explosives into the island, was the 23rd Marines, under the command of Colonel Louis R. Jones. Separated by a lane of 100 yards from Jones’ two assault battalions were the two battalions that were leading Colonel Merton J. Batchelder’s 25th Marines toward its objective. The 23rd Marines was to seize Beaches Blue 1 and 2, while the 25th Marines crossed Yellow 1 and 2. The frontage assigned each battalion was 600 yards. The right limit of Yellow 3, southernmost of the beaches, lay a short distance north of Agingan Point. (See Map 16.)

These two divisions were Admiral Turner’s right hand, his knockout punch. As he delivered this blow, he feinted with his left hand, the units that had been sent toward Tanapag Harbor.

The Tanapag Demonstration

Since 14 June, two old battleships, a cruiser, and four destroyers had been shelling the coastline from Garapan to Marpi Point. While the assault waves were forming off Charan Kanoa on the morning of the 15th, the transports lying off the entrance to Tanapag Harbor began lowering their landing craft. Except for the intelligence section of the 2nd Marines, no troops embarked in these boats, which milled about approximately 5,000 yards from shore and then withdrew. By 0930, the craft were being hoisted on board the transports.

The maneuvering of the landing craft drew no response from Japanese guns, nor did observers notice any reinforcements being rushed into the threatened sector. A prisoner captured later in the campaign, an officer of the 43rd Division intelligence section, stated that the Japanese did not believe that the Marines would land at Tanapag Harbor, for on D minus 1 the heaviest concentrations of naval gunfire, as well as the bulk of the propaganda leaflets, had fallen in the vicinity of Charan Kanoa. The enemy, though, was not absolutely certain that he had correctly diagnosed Admiral Turner’s intentions, so the 135th Infantry Regiment was not moved from the northern sector.4 Admiral Turner’s demonstration had immobilized a portion of the Saipan garrison, but it had not forced the Japanese to weaken the

concentration of troops poised to defend the southwestern beaches.

The Landings

Although the demonstration drew no fire, the enemy reacted violently to the real landing. A few shells burst near the line of departure as the LVTs were starting toward shore, but this enemy effort seemed feeble in comparison to the American bombardment which was then reaching its deafening climax. Warships hammered the beaches until the tractors were within 300 yards of shore, and concentrated on Afetna Point until the troops were even closer to the objective. Carrier planes joined in with rockets, 100-pound bombs, and machine gun fire when the first wave was 800 yards from its goal. The pilots, who continued their attacks until the Marines were ashore, carefully maintained a 100-yard safety zone between the point of impact of their weapons and the advancing LVTs.

Bombs, shells, and rockets splintered trees, gouged holes in Saipan’s volcanic soil, and veiled the beaches in smoke and dust. The scene was impressive enough, but one newspaper correspondent nonetheless scrawled in his notebook: “I fear all this smoke and noise does not mean many Japs killed.”5 The newspaperman was correct. From the midst of the seeming inferno, the Japanese were preparing to fight back.

As soon as the tractors thundered across the reef, they were greeted by the fires of automatic cannon, antiboat guns, artillery pieces, and mortars. To the men of the 2nd Marine Division it seemed that the shells were bursting “in an almost rhythmical patter, every 25 yards, every 15 seconds. ...”6 Japanese artillery units had planned to lavish 15 percent of their ammunition on the approaching landing craft and an equal amount on the beaches.7 Some of these projectiles were bound to find their mark. Here and there an LVT became a casualty. Such a victim “suddenly stood on end and then sank quivering under a smother of smoke. Bloody Marines twisted on its cramped deck, and in the glass-hatched driver’s cabin another Marine slumped among the stained levers.”8 In spite of their losses, the assault waves pressed forward, and by 0843 the first of the troops were ashore.

The 2nd Marine Division, bound for the beaches on the left, landed somewhat out of position. Since control craft could not cross the reef, the LVTs were on their own during the final approach. Drivers found it difficult to maintain direction in the face of deadly fire, and a strong northerly current, undetected by the previous day’s reconnaissance, further complicated their task. Commander Kauffman’s underwater scouts had landed during different tidal conditions, so they did not encounter the treacherous current. Thus, the drift of sea, the inability of control vessels to surmount the reef, and the Japanese fusillade combined to

force the division to land too far to the left.

The 6th Marines was scheduled to cross Red 2 and 3, but 2/6, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Raymond L. Murray, and Lieutenant Colonel John W. Easley’s 3/6 came ashore some 400 yards north of their goals, arriving on Red 1 and 2 respectively. In the zone of the 8th Marines, the situation was more serious. Lieutenant Colonel Henry P. Crowe’s 2/8 and 3/8, under Lieutenant Colonel John C. Miller, Jr., landed on Green 1, some 600 yards from the regimental right boundary. Since the enemy had dropped a curtain of fire over the beaches, this accidental massing of troops contributed to the severe losses suffered during the day.

The 4th Marine Division landed as planned, with 3/23, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John J. Cosgrove, and 2/23, under Lieutenant Colonel Edward J. Dillon, seizing footholds on Blue 1 and 2, while Lieutenant Colonel Lewis C. Hudson’s 2/25 and Lieutenant Colonel Hollis U. Mustain’s 1/25 landed on Yellow 1 and 2. Once ashore, the attached LVTs and armored amphibians were to have fanned out to overrun Agingan Point, Charan Kanoa, and the ridge line some 2,000 yards inland of the coast. Enemy fire, however, prevented the coordinated thrust upon which General Schmidt had counted. Portions of the division advanced as far as the ridges, but other units were forced to abandon their tractors at the beaches.9 All along the western beaches, the attack was losing its momentum. The next few hours could prove critical.

The Fight For the RED Beaches

During the planning of the Saipan operation, General Watson had expressed doubts concerning the soundness of the Northern Troops and Landing Force scheme of maneuver. The Commanding General, 2nd Marine Division, did not believe that the LVTs could scale the embankments, thread their way through the rocks, or penetrate the swamps that in many places barred the exits from the beaches. Instead of having the tractors advance to the 0-1 Line, he wanted the LVT(A)s to move a short distance inland and keep the defenders pinned down while the first wave of LVTs cleared the beaches and discharged their troops. Succeeding waves would halt on the beaches, unload, and return to the transfer area. Watson was convinced that the tractors should not attempt to advance beyond the railroad line running northward from Charan Kanoa. General Holland Smith accepted these suggestions and permitted the 2nd Marine Division to attack on foot from the railroad to O-1. General Schmidt, however, chose to rely on his LVTs to execute the original scheme of maneuver in his division zone.

That General Watson obtained a modification of the plan was fortunate, for intense enemy fire and forbidding terrain halted the tractors near the beaches. On Red 1 and 2, the initial thrust of the 6th Marines stalled about 100 yards inland. The captured strip of sand was littered with the hulks of disabled tractors. Here the wounded lay amid the bursting shells to await evacuation, while their comrades plunged into the thicket along the coastal highway.

For the most part, the Marines were fighting an unseen enemy. A Japanese tank, apparently abandoned, lay quiet until the assault waves had passed by and then opened fire on Lieutenant Colonel William K. Jones’ 1/6, the regimental reserve, as that unit was coming ashore. Rounds from a rocket launcher and rifle grenades permanently silenced the tank and killed its occupants. From the smoke-obscured ground to the front of 3/6, a machine gun poured grazing fire into the battalion lines. Equally impersonal, and perhaps more deadly, were the mortar and artillery rounds called down upon the advancing Marines by observers posted along the Japanese-held ridges that formed the O-1 Line.

Occasionally, small groups of Japanese from the 136th Infantry Regiment suddenly emerged from the smoke, but the enemy preferred mortar, artillery, and machine gun fires to headlong charges. A few minutes after 1000, as Colonel Riseley was establishing his regimental command post on Red 2, between 15 and 25 Japanese suddenly materialized and began attacking southward along the beach. The bold thrust accomplished nothing, for the enemy soldiers were promptly cut down.

Light armor from Colonel Takashi Goto’s 9th Tank Regiment made two feeble counterattacks against the 6th Marines. At noon, two tanks rumbled forth from their camouflaged positions to the front of 2/8 and started southward along the coastal road, Evidently the tank commanders were bewildered by the smoke, for they halted their vehicles within Marine lines. The hatch of the lead tank popped open, and a Japanese thrust out his head to look for some familiar landmark. Before the enemy could orient himself, Marine rocket launcher teams and grenadiers opened fire, promptly destroying both tanks. An hour later, three tanks attempted to thrust along the boundary between the 1st and 2nd Battalions. Two of the vehicles were stopped short of the Marine positions, but the third penetrated to within 75 yards of Colonel Riseley’s command post before it was destroyed.

The first few hours had been costly for Riseley’s 6th Marines. By 1300, an estimated 35 percent of the regiment had been wounded or killed. Lieutenant Colonel Easley, though wounded, retained command over 3/6 for a time. Lieutenant Colonel Murray, whose injuries were more serious, turned 2/6 over to Major Howard J. Rice. Rice, in turn, was put out of the fight when, for the second time within five hours, a mortar round struck the battalion command post. Lieutenant Colonel William A. Kengla, who was accompanying the unit as an observer, took over until Major LeRoy P. Hunt, Jr., could come ashore.

In spite of the losses among troops and

leaders alike, the attack plunged onward. By 1105, the shallow initial beachhead had been expanded to a maximum depth of 400 yards. Twenty minutes later, Lieutenant Colonel Jones’ 1/6 was ordered to pass through 3/6, which had been severely scourged by machine gun fire, and attack to the O-1 Line, where it would revert to reserve by exchanging places with the units it had just relieved. This planned maneuver could not be carried out. The 1st Battalion could not gain the ridge line, and as the 6th Marines moved forward, the regimental frontage increased until all three battalions were needed on line.

During the day’s fighting, a gap opened between the 6th and 8th Marines. Colonel Riseley’s troops, manning a dangerously thin line and weary from their efforts, could extend their right flank no farther. Colonel Wallace’s 8th Marines, which had undergone a similar ordeal, was in much the same condition.

The GREEN Beaches and Afetna Point

The key terrain feature in the zone of the 8th Marines was Afetna Point which straddled the boundary between the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions. Since the company charged with capturing Afetna Point would have to attack toward the flank of General Schmidt’s division, about half the unit was issued shotguns. These short-range weapons would not be as dangerous as M1s to friendly troops, and their wide patterns of dispersion would make up for their comparative inaccuracy. The attackers, Marines of Company G, also carried their regularly assigned weapons for use after the point had been secured.

While coming ashore, Wallace’s command had suffered “miraculously few LVT casualties”10 in spite of the ponderous barrage falling on and near the beaches. Both assault battalions, Crowe’s 2/8 and Miller’s 3/8, landed on the same beach, Green 1, and their component units became intermingled. In the judgment of the regimental commander, “If it had not been for the splendid discipline of the men and junior officers, there would have been utter confusion.”11 The various commanders, however, could not be certain of the exact location and composition of their organizations.

After a brief pause to orient themselves, the companies began fanning out for the attack. On the right, Company G of Crowe’s battalion, its flank resting upon the Charan Kanoa airstrip, pushed southward along Green 2 toward Afetna Point. The advance was bitterly opposed. Japanese riflemen fired across the narrow runway into the exposed flank of the company until they were killed or driven off by Marine mortars and machine guns. On the opposite flank were emplaced nine antiboat guns. Fortunately for Company G, the Japanese gunners doggedly followed their orders to destroy the incoming landing craft, so the Marines were able to attack these emplacements from the rear. By darkness, when the company dug in for the night, all but two of the gun positions had been overrun, and all of Green

2, including the northern half of Afetna Point, was in American hands. In his report of the Saipan operation, Colonel Wallace expressed his belief that because of the confused landing, the capture of the point was delayed by 24 hours.

While one company was battling to join forces with the 4th Marine Division and secure use of the boat channel that led to Green 3, the rest of 2/8 was advancing toward the marsh extending northward from Lake Susupe. Elements of the battalion crossed the swamp, only to discover they were isolated, and had to fall back to establish a line along the firm ground to the west. On the left, 3/8 pushed directly inland from Green 1.

The regimental reserve, 1/8, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Lawrence C. Hays, Jr., was ordered ashore at 0950. One of Hays’ companies was sent toward the airstrip to protect the left flank of the unit attacking Afetna Point. The two remaining rifle companies were committed along the boundary between the 2nd and 3rd battalions.

The next landing team to reach the Green Beaches was Lieutenant Colonel Guy E. Tannyhill’s 1/29, the division reserve. Lieutenant Colonel Tannyhill’s Marines, who had taken part in the feint off Tanapag, came ashore early in the afternoon and were attached to the 8th Marines. Company B was ordered to seal a gap in the lines of 2/8, but the reinforcing unit became lost, and Company A was sent forward in its place. This second attempt was thwarted by Japanese forward observers who promptly called for artillery concentrations which halted the Marines short of the front lines. While the men of Company A were seeking cover from the deadly shells, Company B found its way into position to close the opening.

The 8th Marines had battled its way as far inland as the swamps. On the left, the opening between Wallace’s regiment and the 6th Marines was covered by fire. The actual lines of the 8th Marines began in the vicinity of the enemy radio station near the regimental left boundary, continued along the western edge of the swamp, and then curved sharply toward Afetna Point. In carving out this beachhead, the regiment had suffered about the same percentage of casualties as had the 6th Marines. Because of the intermingling of the assault battalions, Colonel Wallace could not at the time make an accurate estimate of his losses. The problem of reorganizing 2/8 and 3/8 was complicated by the grim resistance and the loss of both battalion commanders. Lieutenant Colonels Crowe and Miller had been wounded seriously enough to require evacuation from the island. Command of 2/8 passed to Major William C. Chamberlain, while Major Stanley E. Larson took the reins of the 3rd Battalion.

Charan Kanoa and Beyond

South of Afetna Point and Charan Kanoa pier lay the beaches assigned to Colonel Jones’ 23rd Marines. At Blue 1, eight LVTs, escorted by three armored amphibians and carrying members of Lieutenant Colonel Cosgrove’s 3/23, bolted forward along the only road leading beyond Charan Kanoa. The column exchanged shots with Japanese

Fire team member dashes across fire-swept open ground past a dud naval shell as Marines advance inland from Saipan beaches. (USMC 83010)

Japanese medium tanks knocked out during the night counterattack on 17 June at Saipan. (USN 80-G-287376)

snipers who were firing from the ditches over which the highway passed, but it encountered no serious resistance in reaching Mount Fina Susu astride the O-1 Line. The troops dismounted and established a perimeter atop the hill, a position exposed to direct fire from Japanese cannon and machine guns as well as to mortar barrages. The LVT(A)s, which mounted flat-trajectory weapons that might have aided the unit mortars in silencing enemy machine guns, halted at the base of the hill. No friendly units were within supporting distance on either flank, but the Marines managed to foil periodic attempts to infiltrate behind them. After dark, the defenders of Fina Susu were ordered to abandon their perimeter and withdraw to the battalion lines.

A similar breakthrough occurred at Blue 2, where five LVT(A)s and a trio of troop-carrying tractors followed the Aslito road all the way to O-1. Again, the remainder of the battalion, in this case Lieutenant Colonel Dillon’s 2/23, was stalled a short distance inland. The advanced outpost had to be recalled that evening.

The 23rd Marines was unable to make a coordinated drive to the O-1 Line. In the north, the Lake Susupe swamps stalled forward progress, and to the south a steep incline, rising between four and five feet from the level beaches but undetected by aerial cameras, halted the tractors. Because of the gap between divisions, the regimental reserve came ashore early in the day to fill out the line as the beachhead was enlarged. At 1055, 1/23, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Haas, landed and moved into an assembly area 300 yards inland of Blue 1. The beachhead, however, did not expand as rapidly as anticipated, so the battalion spent the morning standing by to protect the left flank or reinforce the front. After sundown, Haas’ troops were ordered to relieve Cosgrove’s 3rd Battalion.

Although few men actually gained the O-1 Line, the 23rd Marines nevertheless managed to gain a firm hold on the Blue Beaches, in spite of the violent fire and formidable natural obstacles which it encountered. Japanese mortar crews and cannoneers created havoc among the amphibian tractors which were attempting to find routes through either the swamp or the embankment. Yet, the Marines cleared the beaches to battle their way toward the ridges beyond. The ruins of Charan Kanoa were overrun and cleared of snipers. A consolidated beachhead some 800 yards in depth was wrested from a determined enemy. The 23rd Marines was ashore to stay.

Action On the Right Flank

Agingan Point, south of the beaches upon which Colonel Batchelder’s 25th Marines landed, was a thorn in the regimental flank throughout the morning of D-Day. On Yellow 1, the beach farthest from the point, Lieutenant Colonel Hudson’s 2/25 landed amid a barrage of high explosives. Approximately half of the LVTs reached the railroad embankment, which at this point ran diagonally inland between 500 and 700 yards from the coastline. LVT(A)s from the Army’s 708th Amphibian Tank Battalion spearheaded the drive, pushing steadily forward in spite of small arms fire from the eastern side

of the rail line. These Japanese riflemen fell back, but artillery pieces and dual-purpose antiaircraft guns kept pumping shells into the advanced position. A bypassed pair of enemy mortars now joined in the bombardment. Since no friendly troops were nearby, Navy planes were called in to destroy the weapons.

To the south, the assault waves of Lieutenant Colonel Mustain’s 1/25 were stopped a dozen yards past the beach. Enfilade fire from Agingan Point inflicted many casualties and prevented the survivors from moving forward. LVTs of the Army’s 773rd Amphibian Tractor Battalion barely had room to land the succeeding waves. Since bursting shells were churning the narrow strip of sand, the tractor drivers retreated as quickly as they could, sometimes departing before communications gear and crew-served weapons and their ammunition could be completely unloaded.

Focal point of enemy resistance was Agingan Point, a maze of weapons positions, and the patch of woods adjacent to that promontory. About 800 yards to Mustain’s front, four or more artillery pieces slammed shells directly into the crowded beachhead. Gradually, however, the Marines worked their way forward, finally reaching O-1 late in the afternoon.

At 0930, the Japanese made their first attempt to hurl 1/25 into the sea. While troops advanced across the ridge that marked the O-1 Line, another enemy force attacked from Agingan Point in an effort to roll up the narrow beachhead. The battalion commander called for air strikes and naval gunfire concentrations which ended the threat for the time being. The defenders, however, persisted in their efforts. Early in the afternoon, tanks from the 4th Tank Battalion joined Mustain’s infantrymen in wiping out two Japanese companies, thus crushing the strongest counterattack of the day against the division flank.

Immediately upon landing, Lieutenant Colonel Justice M. Chambers’ 3/25, the regimental reserve, sent reinforcements to Mustain. In the confusion of landing, portions of two rifle companies, instead of one complete company, were directed toward Agingan Point. The remainder of the reserve moved forward, mopping up in the wake of the advancing assault battalions. About 700 yards inland, Chambers’ men took cover along the railroad embankment. From the comparative safety of this position additional reinforcements were dispatched to Agingan Point, where 1/25 had by now seized the initiative from the elements of the 47th Independent Mixed Brigade that had been posted there.

Progress on the southern flank was slow, for a powerful enemy contingent occupied the point. Like the Eniwetok Island garrison, these soldiers had dug and carefully camouflaged numerous spider holes. The defenders waited until a fire team had passed them, then emerged from concealment to take aim at the backs of the Marines. One of the companies detached from Chambers’ battalion reported killing 150 Japanese during the afternoon.

In spite of the battering it had received from artillery located in the island’s interior, the 25th Marines made the deepest penetration, over 2,000 yards, of the day’s fighting. Its

battalions had reached the O-1 Line throughout the regimental zone, but an enemy pocket, completely isolated from the main body, continued to cling to the tip of Agingan Point. Both divisions had gained firm holds on the western beaches.

Supporting Weapons and Logistical Problems12

After the preliminary bombardment had ended, ships and aircraft continued to support both divisions. Planes remained on station throughout the day. Once the liaison parties ashore had established radio contact with the agencies responsible for coordinating and controlling their missions, the pilots began attacking mortar and artillery positions as well as reported troop concentrations.

Warships played an equally important role in supporting the Marines. From the end of the preparatory shelling until the establishment of contact with the battalions they were to support, the fire-support units blasted targets of opportunity. Subsequent requests from shore fire control parties were checked against calls for air strikes to avoid duplication of effort and the possible destruction of low-flying planes. Perhaps the most striking demonstration of the effectiveness of naval gunfire in support of the day’s operations ashore was the work of the battleship Tennessee and three destroyers in helping to halt the first counterattack against Mustain’s troops.

The 2nd Tank Battalion, commanded by Major Charles W. McCoy, and the 4th Tank Battalion, under Major Richard K. Schmidt, also assisted the riflemen in their drive eastward. Armor from McCoy’s battalion crawled from the LCMs, plunged into the water at the reef edge, and passed through the curtain of shellfire that barred the way to Green 1. Since the enemy still held Afetna Point, the boat channel leading to Green 3 could not be used as planned. The last tank lumbered ashore at 1530, 2½ hours after the first of the vehicles had nosed into the surf. One company of 14 Sherman medium tanks helped shatter the positions blocking the approaches to Afetna Point. A total of eight tanks were damaged during the day, but seven of these were later repaired.

Heavy swells, which mounted during the afternoon, helped complicate the landing of the 4th Tank Battalion. Company A started toward Blue 2, but en route the electrical systems of two tanks were short-circuited by seawater. Another was damaged after landing. Four of the 14 Shermans of Company B survived shells and spray to claw their way onto the sands of Blue 1. Six tanks of the company were misdirected to Green 2, but only one actually reached its destination, the rest drowned out in deep water; the sole survivor was promptly commandeered by the 2nd Tank Battalion. Company C, which landed on Yellow 2 without

losing a single tank, supported the advance of Dillon’s 2/23. Company D landed 10 of its 18 flame-throwing light tanks, but these machines were held in an assembly area. As far as the 4th Division tankers were concerned, the crucial action of the day was the smashing of the afternoon counterthrust against 1/25.

Two 75-mm pack howitzer battalions landed on D-Day to support General Watson’s division. Lieutenant Colonel Presley M. Rixey’s 1/10 went into position to the rear of the 6th Marines, while the 2nd Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel George R. E. Shell, crossed the airstrip in order to aid the 8th Marines. In crossing the runway, Shell’s men were spotted by the enemy, but the ensuing counterbattery fire did not destroy any of their howitzers. Colonel Raphael Griffin established his regimental command post before dark, but none of the 105-mm battalions were landed.

South of the 2nd Marine Division beachhead, all five battalions of Colonel Louis G. DeHaven’s 14th Marines landed on the Blue and Yellow beaches. The 2nd Battalion had the greatest difficulty in getting ashore, for its elements were scattered along three different beaches. During reorganization on Blue 2, casualties and losses of equipment to both the sea and hostile fire forced the battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel George B. Wilson, Jr., to merge his three 75-mm batteries into two units. The other pack howitzer battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Harry J. Zimmer’s 1/14, was forced to disassemble its weapons and land from LVTs, as the DUKWs that were scheduled to carry the unit failed to return as planned after landing a 105-mm battalion. The only firing position available to 1/14 on Yellow 1 was a scant 100 yards from the water. Firing from Yellow 2 was 3/14, a 105-mm battalion commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. MacFarlane, the first element of the 14th Marines to go into action on Saipan. Immediately after landing on Blue 2, Lieutenant Colonel Carl A. Youngdale’s 4th Battalion lost four 105s to Japanese mortar fire, but the artillerymen managed to repair the damaged weapons. From its positions on Blue 2, 5/14, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Douglas E. Reeve, temporarily silenced a Japanese gun that was pounding the beachhead from a range of 1,500 yards.

Supplying the landing force did not prove as difficult at Saipan as it had at Tarawa. By having certain of the LVTs dump boxes of rations and medical supplies, cases of ammunition, and cans of water onto the beaches as the later waves were landing, supply officers were able to sustain the assault troops. Unlike the cargo handlers at Betio, the Saipan shore parties soon had sufficient room to carry out their tasks. Early in the afternoon, supplies began flowing from the transports, across the beaches, and to the advancing battalions. Japanese fire and a lack of vehicles, however, did handicap the D-Day supply effort.

Enemy artillery and mortar concentrations also endangered the lives of the wounded Marines who were waiting on the beaches for the tractors that would carry them out to sea. About 60 percent of the wounded were taken directly to the transports. Although no accurate accounting was made until 17

June, as many as 2,000 men may have been killed or wounded on D-Day.

The Situation Ashore: The Evening of D-Day

By darkness on D-Day, the two Marine divisions had succeeded in establishing themselves on the western coast of Saipan. Approximately half of the planned beachhead had been won, but the enemy still held the ridges that dominated captured segments of the coastal plain. The 2nd Marine Division manned a line that stretched from the coast about one mile south of Garapan to the middle of Afetna Point. The maximum depth of the division beachhead was about 1,300 yards. Before dark, Colonel Walter J. Stuart had landed one battalion and part of another from his 2nd Marines. These reserves provided added strength in the event of a counterattack. Also ashore was General Watson, who now commanded operations from a captured munitions dump inland of the coastal road on the boundary between Red 1 and Red 2. The cached explosives were removed during the night and following morning. (See Map 16.)

In the 4th Marine Division zone, those elements of the 23rd Marines that had reached the O-1 Line fell back some 800 yards during the night. After this adjustment, the front moved from the coastline 800 yards inland along the division boundary, turned south past Charan Kanoa, and then bulged eastward to O-1. In the right half of General Schmidt’s zone of action, a band of Japanese entrenched on Agingan Point prevented the Marines from occupying all the territory west of the critical ridge line. Colonel Franklin A. Hart’s 24th Marines was ashore, with elements of its 1st Battalion committed between 2/23 and 2/25, while the rest of the regiment occupied assembly areas. General Schmidt had moved into a command post on Yellow 2.13

The Japanese Strike Back

As soon as American carrier planes had begun to hammer the Marianas in earnest, Admiral Toyada signaled the execution of A-GO. On 13 June, as it was starting northward from Tawi Tawi, Ozawa’s task force encountered the submarine USS Redfin, which reported its strength, course, and speed. Another submarine, the USS Flying Fish, sighted Ozawa’s ships on 15 June, as they were emerging from San Bernardino Strait between Samar and Luzon. The Japanese were by this time shaping an eastward course. On this day, the submarine USS Seahorse observed the approach of the warships diverted from Biak, but the enemy jammed her radio, and she was unable to report the sighting until 16 June.

Admiral Spruance was now aware that enemy carriers were closing on the Marianas. Japanese land-based planes also were active, as was proved by an unsuccessful attack upon a group of

American escort carriers on the night of 15 June. After evaluation of the latest intelligence, Spruance decided on the following morning to postpone the Guam landings, tentatively set for 18 June, until the enemy carrier force had either retreated or been destroyed.

While Ozawa was steaming nearer, the Japanese on Saipan were preparing to carry out their portion of A-GO. As one member of the 9th Tank Regiment confided to his diary, “Our plan would seem to be to annihilate the enemy by morning.”14 First would come probing attacks to locate weaknesses in the Marine lines, then the massive counterstroke designed to overwhelm the beachhead.

The heaviest blows delivered against General Watson’s division were aimed at the 6th Marines. Large numbers of Japanese, their formations dispersed, eased down from the hills without feeling the lash of Marine artillery. The two howitzer battalions, all that the division then had ashore, were firing urgent missions elsewhere along the front and could not cover the avenue by which the enemy was approaching. The California received word of the movement and opened fire in time to help crush the attack. Before midnight, the Japanese formed a column behind their tanks in an effort to overwhelm the outposts of 2/6 and penetrate the battalion main line of resistance. Star shells blossomed overhead to illuminate the onrushing horde. Riflemen and machine gunners broke the attack, and the California secondary batteries caught the survivors as they were reeling back. Although this first blow had been parried, the Japanese continued to jab at the perimeter.

At 0300, regimental headquarters received word that an attack had slashed through the lines of 3/6, but the company sent to block this penetration found the front intact. A similar report received some three hours later also proved false. The enemy, however, maintained his pressure until a platoon of medium tanks arrived to rout what remained of the battalion which the 136th Infantry Regiment had hurled against the beachhead. In eight hours of intense fighting, the 6th Marines had killed 700 Japanese soldiers.

The 8th Marines was harassed throughout the night by attacks that originated in the swamps to its front. These blows, weak and uncoordinated, were repulsed with the help of fires from 2/10. The enemy did not employ more than a platoon in any of these ill-fated thrusts.

Throughout the sector held by General Schmidt’s 4th Marine Division, the Japanese made persistent efforts to shatter the American perimeter. Approximately 200 of the enemy advanced from the shores of Lake Susupe, entered the gap between the divisions, and attempted to overwhelm 3/23. The battalion aided by Marine and Army shore party troops, held firm.

The 25th Marines stopped one frontal attack at 0330, but an hour later the Japanese, advancing behind a screen of civilians, almost breached the lines of the 1st Battalion. As soon as the Marines discovered riflemen lurking behind the refugees, they called 1/14 for artillery support. This unit, out of

ammunition, passed the request to 3/14, which smothered the attack under a blanket of 105-mm shells. The only withdrawal in the 25th Marines sector occurred when a Japanese shell set fire to a 75-mm self-propelled gun. Since the flames not only attracted Japanese artillery but also touched off the ammunition carried by the burning vehicle, the Marines in the immediate area had to fall back about 200 yards.

The Japanese had been unable to destroy the Saipan beachhead, but the battle was just beginning. The Thirty-first Army chief of staff admitted on the morning of 16 June that “the counterattack which has been carried out since the afternoon of the 15th has failed because of the enemy tanks and fire power.” Yet, he remained undaunted. “We are reorganizing,” his report continued, “and will attack again.”15 While the battle raged ashore, an enemy fleet was bearing down on the Marianas. If all went as planned, Admiral Ozawa and General Saito might yet trap the American forces.