Part V: Assault on Tinian

Blank page

Chapter 1: The Inevitable Campaign1

For Marines who had made the 3,200-mile voyage from Hawaii to Saipan, the trip to the next objective was a short one. Just three miles of water separate Tinian from Saipan, In the Pacific war, such proximity of the objective was unusual, but there were also other details of the Tinian assault which made it unique. Here was one of those military enterprises that observers like to term classic. Admiral Spruance called Tinian “probably the most brilliantly conceived and executed amphibious operation of World War II.”2 General Holland Smith saw gratifying results of the amphibious doctrine he helped develop before the war. Tinian, he wrote afterwards, was “the perfect amphibious operation in the Pacific war.”3 Marines in the battle for Tinian profited by the flexible application of amphibious warfare techniques so laboriously evolved during the practice landings of the 1930s.

Why Tinian?

Capture of the island was a military necessity. It was, of course, unthinkable that Japanese troops remain on Tinian, next door to Saipan. But there also existed a more positive reason for wanting Tinian—its usefulness for land-based aircraft. The island is the least mountainous of the Marianas, the one which was most suited for new American long-range bombers. It was from Tinian that the B-29s rose to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945.

The Japanese knew the military

value of Tinian. They had used the island for staging planes and as a refueling stop for aircraft en route to and from the Empire. On Ushi Point they had constructed an airfield which was even better than Aslito on Saipan. The two excellent strips on this field were labeled by American intelligence as Airfield No. 1 and Airfield No. 3. The older north strip, the site of the main airdrome, was 4,750 feet long. Two villages adjoined the activity, housing the personnel. On Gurguan Point was another airstrip which extended 5,060 feet (Airfield No. 2). Northeast of Tinian Town lay Airfield No. 4, still under construction. Already 70 percent surfaced, it could be used for emergency landings. These airfields drew the bulk of Japanese defensive weapons on Tinian. The enemy had sited a number of heavy and medium antiaircraft and light machine guns in the vicinity of each field, particularly the prized Ushi Point strips. (See Map 21.)

American photographic reconnaissance of Tinian, begun on a carrier strike of 22-23 February 1944, focused on the airfields, though not to the neglect of the rest of the island. Perhaps no other Pacific island, not previously an American possession, became so familiar to the assault forces because of thorough and accurate mapping prior to the landings. Documents captured on Saipan were also informative, because the Japanese, as well as the Americans, had linked the two islands in their military plans.

In the whole field of intelligence, the Tinian operation benefited from early planning, general though it was. Detailed planning for Tinian had to yield precedence to that for Saipan and Guam, but once the end of the Saipan campaign was in sight, NTLF headquarters began daily conferences regarding the assault on the nearby target.

Description of Tinian

The island the commanders talked about was scenically attractive, observed from either a ship or a plane. In fact, it was said that naval and air gunners were sorry to devastate the idyllic landscape of Tinian. It consisted mainly of small farms, square or rectangular, which, viewed from the air, appeared like squares of a checkerboard. Each holding was marked off by bordering ditches, used for irrigation, or by rows of trees or brush, planted for use as windbreaks.

Tinian measures about 50 square miles. It extends 12¼ miles from Ushi Point to Lalo Point but never is more than 5 miles wide. In the wettest months (July to October) of the summer monsoon, the island is drenched by nearly a foot of rainfall per month. Ninety percent of the area is tillable. In 1944, the population of 18,000 consisted almost entirely of Japanese, for all but a handful of the native Chamorros had been moved off to lesser islands of the Marianas. Most of the Japanese had been brought to Tinian by a commercial organization to produce sugar, the chief island product. Tinian produced 50 percent more sugar cane than Saipan. Tinian Town was the center of the industry and had two sugar mills which received the raw product, mostly freighted over a small winding railroad. A good

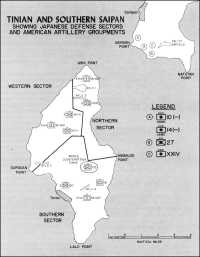

Map 21: Tinian and Southern Saipan, Showing Japanese Defense Sectors and American Artillery Groupments

network of roads also served the transportation needs of the island.

Basically, Tinian was a pleasant and prosperous island. The sole forbidding aspect, except for the Japanese military installations that summer of 1944, were the coral cliffs which rise from the coastline and are a part of the limestone plateau underlying Tinian. A few hills jut up from the plateau, but the principal one, Mt. Lasso, in the center of the island, is only 564 feet high, just a third the size of Mt. Tapotchau on Saipan; Mt. Maga, in the north, measures 390 feet, and an unnamed elevation in the south is 580 feet high. The cliffs which encircle the plateau vary in height, from 6 to 100 feet. Breaks along the cliff line are few and narrow, putting beach space at a premium.

It was, in fact, the question of landing beaches which particularly dominated the planning for Tinian, even more than it usually did for other island campaigns. The Japanese knew they could not escape an assault of Tinian—but where would the landings be made, when, and in what force? Concerning these matters, the enemy had to be kept in the dark until the invasion actually began.

Along the entire coastline of Tinian, only three areas have beaches worthy of the name. One is the vicinity of Sunharon Harbor near Tinian Town, where the several sandy stretches are the widest and most suitable beaches for invasion. On the opposite side of the island, along Asiga Bay, the cliff line breaks off, resulting in a beach approximately 125 yards wide. On the northwest coast, below Ushi Point, are two stingy strips of beach 1,000 yards apart. Intelligence reported one to be about 60 yards wide and the other about 160. Japanese civilians had found the white, sandy beaches pleasant and the water there good enough for swimming and, in fact, had called them the White Beaches. This happened also to be the code name assigned to the two beaches by invasion planners, while the Asiga Bay beach was designated Yellow Beach. (See Maps 22 and 23. )

Colonel Keishi Ogata,4 commander of the 50th Infantry Regiment and responsible for the defense of Tinian, believed the Americans would land either near Tinian Town or at Asiga Bay. The colonel’s “Defense Force Battle Plan,” issued from his command post in a Mt. Lasso cave on 28 June, showed only such expectations.5 He did not, of course, ignore the northwest beaches, but he anticipated only a small landing party there, at the most. To meet such a remote contingency, the colonel directed that some troops be positioned inland of the beaches. A “Plan for the Guidance of Battle,” issued to those troops on 7 July, was captured by Marines the day after the landing on Tinian. In that plan, Colonel Ogata ordered his men to be ready to counterattack on the larger White Beach (White 2). But he scorned the smaller beach (White 1) as being unworthy of consideration.

An enemy strongpoint, American intelligence reported, was located

about 500 yards northeast of the White Beaches. It included the usual trenches, dugouts, and light machine gun or rifle positions in a wooded area. Among the heavier weapons emplaced here were a 37-mm antitank gun, a 47-mm antitank gun, and two 7.7-mm machine guns.

Japanese Troops and Equipment

Colonel Ogata had only about 8,900 men to dispose judiciously before the Americans came. The mainstay of the Tinian garrison was the well-trained 50th Infantry Regiment, with a strength of about 3,800 men.6 The regiment consisted of headquarters, three infantry battalions (each with 880 men, organized into a headquarters detachment, three rifle companies, and a battalion gun platoon with two 70-mm guns), one 75-mm mountain artillery battalion (three four-gun batteries, one to each infantry battalion), supply, signal, and medical companies, one antitank platoon (six 37-mm guns), and a fortification detachment.

Other Army elements included the 1st Battalion of the 135th Infantry Regiment, the tank company of the 18th Infantry Regiment, a detachment of the 29th Field Hospital, and a motor transport platoon. The infantry battalion had been engaged in amphibious exercises off Tinian when, at the approach of Task Force 58 on 11 June, it was detached from its parent regiment on Saipan and put into the defense system for Tinian.7 As a result, just about half of the strength available to Colonel Ogata was made up of Army personnel.

The naval complement on Tinian consisted chiefly of the 56th Naval Guard Force (Keibitai), numbering about 1,400 men that had been partially trained as infantry. Most of the sailors of the Keibitai were assigned to the coastal defense and antiaircraft guns, but some of them comprised a Coastal Security Force which operated patrol boats and laid beach mines. The 233rd Construction Battalion came to about 600 men, while other miscellaneous construction personnel totaled around 800. The antiaircraft units of the 56th Keibitai were later identified as the 82nd and 83rd Air Defense Groups, each numbering between 200 and 250 men, the former unit being equipped with 24 25-mm antiaircraft guns and the latter with 6 dual-purpose 75-mm guns. Other naval units included a detachment of the 5th Base Force and the ground elements of seven aviation squadrons.8

In charge of all naval personnel on the island was Captain Goichi Oya, though the senior naval officer present was Vice Admiral Kakuji Kakuda, commanding the First Air Fleet, whose headquarters was on Tinian. Kakuda, however, was more interested in transferring his command elsewhere, and he left the Tinian naval duties to Captain Oya, who, a week before the invasion, moved his command post from Tinian Town to high ground near the town. Captain Oya was supposed to report to Colonel Ogata, but he was inclined to act independently.

Colonel Ogata had marked off the island into three defense sectors. The southern, the largest of the three, comprised the entire area below Mt. Lasso and included Tinian Town. The northern sector covered the Ushi Point air strips and Asiga Bay. To defend each of those sectors, Ogata assigned a battalion of the 50th Infantry Regiment and a platoon of engineers. In the western sector, however, where the northwest beaches lay, he left only the 3rd Company of the 1st Battalion and an antitank squad. The rest of the 1st Battalion was put into reserve just south of Mt. Lasso. Though in the western sector, these troops were positioned much closer to Asiga Bay than to the northwest beaches. (See Map 21.)

A “Mobile Counterattack Force”—the 1st Battalion of the 135th Infantry Regiment, actually another reserve—was located in the southern sector, centrally stationed to move either toward Asiga Bay or the Tinian Town area. The force was called mobile because it would “advance rapidly to the place of landings, depending on the situation, and attack.”9 Mobility, in fact, was a keynote of the Japanese plan. Each sector commander would be prepared not only “to destroy the enemy at the beach” but also “to shift two-thirds of the force elsewhere.”10

Incorporated within the defense were the twelve 75-mm mountain guns of the artillery battalion of the 50th Infantry Regiment which, when reinforced by the 70-mm guns of the infantry battalions, made up a Mobile Artillery Force. The artillery battalion would rapidly deploy to support jointly a counterattack with the tank company of the 18th Infantry Regiment, whose 12 light tanks were the enemy’s only armor on Tinian. This unit, positioned in the southern sector, also possessed two of the rare Japanese amphibian trucks.

Naval personnel on the island were variously employed by Colonel Ogata. They guarded the airfields, particularly at Ushi Point, and protected the harbor installations of Asiga Bay and Sunharon Harbor. Naval gunners manned most of fixed artillery on the island and its antiaircraft weapons. The former included ten 140-mm coast defense guns—three of them on Ushi Point, three on Faibus San Hilo Point, and four commanding Asiga Bay.

Three of the ten 120-mm dual purpose guns on Tinian shielded the Ushi Point air strips, while three more served the airfield at Gurguan Point. Behind Tinian Harbor stood four more 120-mm dual purpose guns, in addition to three 6-inch naval guns of British 1905 make. These 6-inch guns were so artfully

concealed in a cave that until they opened up on the day of the landing their presence was unknown. The prized Ushi Point airfield was solicitously guarded by antiaircraft weapons, including 6 13-mm antiaircraft and antitank guns, 15 25-mm twin mounts, 4 20-mm automatic cannons, and 6 75-mm guns.

Miscellaneous types rounded out the Japanese arsenal of weapons on Tinian. In 23 pillboxes which ringed Asiga Bay there were machine guns of unknown caliber. They never took a Marine’s life, however, for they—like a number of the other guns pinpointed by reconnaissance—were destroyed by bombardment prior to the invasion.

Preparatory Bombardment

Tinian received a more thorough going over than most other island objectives of the Pacific war, chiefly because the usual naval and air bombardment was augmented for weeks by the fires of artillery. On 20 June, hardly a week after the landings on Saipan, Battery B of the 531st Field Artillery turned its 155-mm guns, the “Long Toms,” upon Tinian. Other units were added thereafter until, by the middle of July, a total of 13 battalions of both Marine and Army artillery were drawn up on southern Saipan, under the command of the Army Brigadier General Arthur M. Harper, General Holland Smith’s valued artillery officer. (See Map 21.)

The Corps Artillery thus emplaced in position and firing on Tinian included the 10th Marines (less the 1st and 2nd Battalions, attached to the 14th Marines); the 3rd and 4th Battalions, 14th Marines (Headquarters and the 1st and 2nd Battalions stayed with the 4th Division); and the 4th 105-mm Howitzer Battalion, VAC, hitherto serving with the 14th Marines. These five battalions of 105-mm howitzers were attached to XXIV Corps Artillery on 15 July and were designated Groupment A, under control of Headquarters, 10th Marines. The artillery of the 27th Infantry Division (less the 106th Field Artillery Battalion) was likewise attached on 15 July and comprised Groupment B. Five battalions of XXIV Corps Artillery formed Groupment C, and they set up the long-range 155-mm guns and 155-mm howitzers, The other Army and Marine battalions were equipped with 105-mm howitzers. The Marines’ four 75-mm pack howitzer battalions were not used but were reserved more suitably for the invasion, where they would furnish close support for the assault divisions to which they were attached.

There was quite enough steel and powder to support the operation. The artillerymen used up 24,536 rounds prior to the landings. A total of 1,509 preinvasion fire missions included counterbattery, harassing, and area bombardment. Corps Artillery kept a valuable file of intelligence data on Tinian which was used by both aviators and naval gunners. A Corps Artillery intelligence section worked very closely with the Force G-2 at the NTLF command post on Saipan. Light spotter aircraft were assigned to the artillery units to observe fire results and to collect target intelligence data for either immediate or future use.

The sea bombardment of Tinian began before artillery was ashore on

Saipan. On 13 June, fire support ships of Task Force 52, which could be spared from the pounding of Saipan, were employed against Tinian. The chief object then was to forestall interference with the Saipan operation by Tinian guns or aircraft. Destroyers started a relentless patrol of Saipan Channel, turning their 5-inch guns upon shore batteries and harassing Ushi Point airfield.

Destroyer activity was rapidly extended to other waters. Star shells were placed over Tinian Harbor to prevent movement from the area of Tinian Town. That whole vicinity, especially the airfield, received harassing fire. Here, because of a shortage of destroyers, much of the responsibility fell to destroyer escorts (DEs), destroyer transports (APDs), or destroyer minesweepers (DMSs), whose crews enjoyed the change of routine. On 25 June, two DEs, the Elden and the Bancroft, spotted a few Japanese barges attempting to leave Sunharon Harbor and blocked their escape by shelling and destroying them. Destroyer escorts also roved to the northwest to harass Gurguan Point airfield by gunfire.

Starting 26 June, the cruisers Indianapolis, Birmingham, and Montpelier undertook a daily systematic bombardment of point targets, which lasted a week and paid special attention to the area of Tinian Town. Intensive bombardment by cruisers was resumed the last few days before the Tinian landings when the Louisville and the New Orleans delivered main and secondary battery fires. Both of these ships, like the Indianapolis, were heavy cruisers. The Louisville served as flagship for Rear Admiral Jesse B. Oldendorf, who commanded the fire support ships for Tinian.

During the numerous naval gunfire missions at Tinian, a variety of shells were utilized. On 18 and 19 July, two destroyers attempted to burn the wooded areas on Mt. Lasso with white phosphorus projectiles. Results were disappointing, however, evidently because of dampness due to rain. But since such fire proved terrifying to the enemy on Saipan, destroyers continued to employ it against caves on Tinian. LCI gunboats also shelled the cliff-side caves of Tinian with their 40-mm guns.

Nowhere on the island were the Japanese left at peace. Starting on 17 July, destroyers from the Saipan Channel patrol delivered surprise night fire at irregular times on the beaches of Asiga Bay, where the enemy was working feverishly to install defenses. The airfields of Tinian were incessantly harassed to deny their use by the enemy. On a single day, 24 June, the battleship Colorado shelled every airfield on the island.

The routine of bombarding Tinian, stepped up on 16 July, was climaxed on the 23rd, the day before invasion, when 3 battleships, 5 cruisers, and 16 destroyers were involved. Only the beaches due to receive the landings were slighted; for the sake of deception, they were subjected to merely casual fire from the Louisville and the Colorado. The old battleship surpassed all its previous efforts by destroying, on the same day, the three 140-mm coast defense guns of Faibus San Hilo Point, with 60 well-placed 16-inch shells. On the day of the landings, however, the Colorado was herself

to suffer tragically from the fire of a coastal battery which had not been destroyed.

From the beginning, the Japanese did not suffer the naval shelling without reacting violently, and their return fire caused damage and casualties to a few of the fire support ships. The enemy’s defenses were, as usual, well dug in, and some were able to survive the heaviest shelling. Ships found a position difficult to destroy totally except by a direct hit. Because there was a lack of profitable or suitable targets for the largest gunfire support ships, the naval bombardment was suspended for a week between the securing of Saipan on 9 July and 16 July. The only exception was night heckling of the enemy by DEs in the area of Tinian Town.

Provisions for naval gunfire were tied into the overall bombardment plan for Tinian. Efficient interlocking of the three supporting arms was served by a daily conference at NTLF headquarters on Saipan attended by representatives of artillery, air, and naval gunfire. Responsibility for daily assignments was left mainly to the fire direction center of XXIV Corps Artillery because of its collected intelligence data and excellent communication setup. Here the targets were allocated as appropriate to each of the supporting arms. If there was a unique aspect to direction of preliminary fires for Tinian, it was that artillery was a decisive factor.

The big land guns were, of course, aimed mostly at northern Tinian. The 155-mm guns could stretch to the southern part of the island, but they seldom attempted it, leaving that half to aircraft instead. Sometimes all three supporting arms had a go at a target. The area of Tinian Town, perhaps the most punished of all, was such an example, though naval gunfire did the most damage there. Use of the island road network was virtually denied to the enemy by the shells and bombs which came from everywhere, isolating some sections and destroying others.

It was neither naval gunfire nor artillery, however, which started the preparatory bombardment of Tinian. On 11 June, Vice Admiral Mitscher’s fast carrier task force sailed into the Marianas. Its immediate object was to support the Saipan operation. To minimize interference from the airfields, antiaircraft guns, and shore batteries on Tinian, these installations were bombed and strafed. The Battle of the Philippine Sea began on 17 June, and TF 58 steamed there to join the battle. Five days later, however, surface elements returned to the Tinian assignment. They then were joined by CVE-based aircraft of Task Force 52 and P-47 fighters based on Aslito. All land-based aircraft (except the Marine observation squadrons), as well as the carrier-based planes engaged in the Tinian operation, operated under Commander Lloyd B. Osborne, Commander Support Aircraft, who was embarked in the Cambria, flagship of Admiral Hill.11

Marine observation planes of VMO-2 and VMO-4 also took part in the preinvasion activity over Tinian. For several days prior to the landings, pilots operating from Aslito flew over the island, learning about it and searching for targets of opportunity. The little unarmed and unarmored OYs, veterans of Saipan, would again serve infantry and artillery missions on Tinian. Until then, they performed some spotting for the artillerymen shelling Tinian from Saipan.

After the capture of Saipan, aerial reduction of the enemy’s defensive positions was undertaken by rocketry, glide bombing, and strafing. Targets included railroad junctions, pillboxes, roads, covered artillery positions, and cane fields. The beaches, in the main, were ignored to keep the enemy puzzled, but the airfields were unreservedly raked. Enemy air strength had already been decisively cut down. Of the 107 planes estimated as being based at Tinian airfields prior to 11 June, 70 were destroyed on the ground by carrier strikes long before the capture of Saipan.

Something new was added to air bombardment at Tinian. On 19 July, an enthusiastic Navy commander arrived on Saipan with an impressive Army Air Forces film showing what happened when napalm powder was mixed with aircraft fuel. He showed the pictures to Admiral Hill and General Schmidt and both were enthusiastic about the possibilities of the new fire bomb.12 Enough napalm and detonators were at hand for a trial run by P-47s. Oil, gasoline, and napalm were mixed in jettisonable fuel tanks. The formula was later improved, but initial results proved good enough to ensure acceptance.13

The first use of the fuel-tank bombs was an attempt to burn off wooded areas which, due to dampness, had previously resisted white phosphorus and thermite. The new incendiary badly scorched the trees, but left the needles only partially burned. Because many of the trees were of hardy and indestructible ironwood, the experiment was inconclusive. Much better results were obtained when napalm was used on cane fields. Smoldering piles and smoking ashes appeared where once grew flourishing cane stalks. On 23 July, two fire bombs burned out considerable underbrush in the White Beach area.

Pilots of the P-47s, which dropped most of the bombs, objected that such missions required extremely low flying, at a risk of attracting heavy ground fire. They also reported too much upward flash, which decreased the incendiary value, and too brief a burning time—60 to 90 seconds. The idea was a promising one, however, and, when the correct formula was evolved, the new fire bomb became one of the most formidable weapons in the American arsenal.

Thus while planes, ships, and artillery foreshadowed the land battle, organization and plans for the invasion were concluded. A few command changes took place, mostly because the

recapture of Guam would be attempted at the same time.

Command Structure and Assignments

Admiral Hill took command of a reconstituted Northern Attack Force (TF 52) on 15 July, relieving Admiral Turner, who could now exercise more fully his responsibility in command of the Joint Expeditionary Force (TF 51). Hill had been Turner’s able second-in-command at Saipan. General Holland Smith was relieved on 12 July and ordered to assume command of the newly-established Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, whose functions included administrative control of all Marines in the Pacific. Command of NTLF and of the V Amphibious Corps was assigned to General Schmidt, who was relieved as 4th Division commander by Major General Clifton B. Cates, one of the few officers who had commanded a platoon, a company, a battalion, a regiment, and now a division in battle. General Watson continued in command of the 2nd Division.

General Smith, in retaining command of Expeditionary Troops (TF 56), also continued in overall command of ground forces in the Marianas operations. But neither he nor Admiral Turner was present at the Tinian landings. They sailed on 20 July, on board the Rocky Mount, to witness the invasion of Guam the next day. Though they returned on 25 July, they left the direction of the Tinian campaign to Admiral Hill and General Schmidt.

As landing force commander for Tinian, General Schmidt would be in tactical control of the troops. Admiral Hill, the attack force commander, was responsible to Admiral Turner for the capture of Tinian. Slated to command Tinian garrison troops was Marine Major General James L. Underhill. He would have the job of developing Tinian as an air base.

The 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions would still compose the assault troops of NTLF, which would make the first corps-sized Marine shore-to-shore operation under combat conditions. The two divisions, however, had suffered grievously on Saipan, and only one replacement draft of 1,268 officers and enlisted men was due before the battle on Tinian. After designating the 4th Division to make the assault landing, General Schmidt reapportioned the men and equipment available. On 18 July, he took all the armored amphibian and amphibian tractor battalions, reorganized them under a Provisional Headquarters, Amphibian Tractors, V Amphibious Corps, and attached it to the 4th Division.14

The 2nd Division lost its 1st Amphibian Truck Company, its 2nd Tank Battalion, and its last two battalions (the 1st and 2nd) of the 10th Marines to a heavy buildup of the 4th Division, whose final reinforced strength included also the 1st Joint Assault Signal Company, the 1st Provisional Rocket Detachment, the 2nd Amphibian Truck

Company, and the 1341st Engineer Battalion (Army).

While such reorganization served to mass combat power in the assault division for seizing and holding the beachhead, it left the 2nd Division markedly understrength for its own mission of landing in support. The only reinforcing units left to General Watson were the 2nd Joint Assault Signal Company and the 2nd Provisional Rocket Detachment.

The reserve 27th Infantry Division was to be prepared to embark on four hours’ notice to land on Tinian. The Army division, however, had been much reduced by casualties and detachments and could muster only about half of its original strength. One of its regiments, the 105th Infantry, was required for garrison duty on Saipan, and its division artillery had been detached earlier to the XXIV Corps Artillery for the reduction of Tinian.

In the two-weeks’ interval between the capture of Saipan and the invasion of Tinian, the battle-experienced Marines enjoyed a break, except for Japanese sniper activity. No rehearsal for the Tinian assault was held, nor was one regarded as necessary, but a certain amount of reorganization went on. On 11 July, the 2nd Marines reverted to the 2nd Division and moved to an assembly area near Garapan. The next day, the 165th Infantry was returned from the 2nd Division to the 27th Division. On 13 July, the 4th Division began moving to a rest area on southeast Saipan, behind the beaches where the Marines had landed. The 23rd Marines stayed in northern Saipan to destroy remaining pockets of Japanese resistance until relieved on 16 July by the 105th Infantry. At the same time the Army relieved the 6th Marines, which ended its mopping up activities and followed the 2nd Marines into the assembly area. The orphan 1st Battalion, 29th Marines, which had been detached from the 2nd Division to Island Command on 6 July, was due to stay on Saipan for garrison duty.

While the Saipan veterans relaxed, speculation as to the next objective was relatively absent. Troops knew the next island would be Tinian. They were left to guess where the landings would be made. That, in fact, was a question unresolved by the high command itself even after Saipan was secured.

The Issue of Where to Land

On 8 July, as time for the invasion of Tinian approached, Admiral Turner put the question to the man due to take over the Northern Attack Force. Admiral Hill was directed to prepare assault plans, suggesting where the landings be made. The debate over which beaches to use was months old. Admiral Turner’s inclination to favor the beaches around Sunharon Harbor was opposed by the majority. Four possible landing spots had been noted in this area; those just off Tinian Town had been designated Red Beach and Green Beach, with the Orange and Blue Beaches nearby. The width of all these beaches totaled 2,100 yards. They were certainly the best on Tinian and superior to those on Saipan. Each was wide, with a gentle slope, and the off-shore reef contained numerous channel openings. Although Tinian Harbor was a poor anchorage and would have to be developed shortly after the

landing, it was the only feasible place for the landing of heavy equipment.

There were, however, two major obstacles to an invasion through the Tinian Town area. One, of course, was that the Japanese expected just such an eventuality and had concentrated so many troops and weapons that a landing there could be made only at a heavy cost to the assaulting forces. The other drawback, related to the first, was that an attack there—or at Asiga Bay—would deprive the Tinian operation of just about the only element of surprise yet left to it. “The enemy on Saipan,” said Colonel Ogata on 25 June, “can be expected to be planning a landing on Tinian. The area of that landing is estimated to be either Tinian Harbor or Asiga Harbor.”15

From the beginning, therefore, American planners had viewed with interest the two small beaches on the northwest coast which, to the Japanese, seemed entirely incapable of supporting a major landing. Perhaps surprise would be obtainable there. What also favored the beaches was their proximity to Saipan for resupply purposes, and the fact that artillery support of the landing would be possible from that island.

Admiral Turner, however, saw another side to the problem. True, the beaches were close to Saipan, but that also meant a long advance down the island, once the landing on Tinian had been accomplished. A shore-to-shore movement involved risking small craft to the vagaries of uncertain weather conditions, whereas at Tinian Town there was a protected harbor, favorable to small boats and unloading operations. Weather could also prevent the rapid displacement to Tinian of field artillery when the troops outran the range of such support from Saipan.

The limited size of the northwest beaches was the chief concern of Admiral Turner, and hardly less so for General Smith and others, though they were not so dubious about them. Everyone felt that the utmost knowledge would have to preface a decision. And, at best, such beaches could serve only as paths or routes, rather than as landing beaches in the usual sense of the word.

When reporting later to Fleet Admiral King, Admiral Hill stated, in simple terms, what the problem was: could two divisions of troops be landed and supplied across beaches the size of White 1 and White 2? Of uppermost concern was whether the amphibian tractors would be able to get ashore, move up to unload, and then turn around. Intelligence sources reported that on White 1 there were only about 60 yards usable for passage of amphibian vehicles and that on the wider White 2 only the middle 65 yards were free of coral boulders and ledges.

To check such findings and also to obtain better knowledge of the beaches16 a physical reconnaissance was necessary. It would have to include Yellow Beach on Asiga Bay, should White 1 and White 2 be found unusable. On 3 July, men of the VAC Amphibious

Reconnaissance Battalion were told to be ready for a mission on some Tinian beaches. On 9 July, General Holland Smith issued the operation order to Captain James L. Jones, specifying the beaches. The mission had the approval of both Admiral Turner and Admiral Hill. The latter ordered the participation of Naval Underwater Demolition Teams.

The mission of the Marines was to investigate the beaches, measure the cliffs, and note the area just beyond, including the exits. They were to report the trafficability of the beaches for LVTs and DUKWs in particular. The naval UDT-men were to do the hydrographic reconnaissance—measuring the height of the surf and the depth of the water, observing the nature of the waves, checking the reefs and beach approaches, and looking for underwater obstacles.

After a rehearsal on the night of 9-10 July, off the beaches of Magicienne Bay, Saipan, the Marines and the Navy teams boarded the transport destroyers Gilmer and Stringham. Company A of the Marine battalion, under the command of Captain Merwin H. Silverthorn, Jr., was assigned to investigate Yellow Beach, while Company B, commanded by Lieutenant Leo B. Shinn, would undertake a reconnaissance of the White Beaches.

The evening of 10 July was very dark when the men debarked into their small rubber boats about 2030. Moonrise occurred at 2232, but fortunately a cloudy sky obscured the moon until almost midnight. Thus the final 500-yard swim to the beaches could be made under the cover of darkness.

Reconnaissance of Yellow Beach, by 20 Marines and 8 UDT-men went off just right, but the reports were unfavorable. On each side of the 125-yard beach, swimmers observed forbidding cliffs which were 20 to 25 feet high. They found also that approaches to the beach contained floating mines, anchored a foot under water off the reef, and that many underwater boulders and potholes would endanger a landing. Craft might be affected also by the relatively high surf, which is generally whipped by prevailing winds.

On the beach itself, the enemy had strung double-apron barbed wire. After working his way through it, Second Lieutenant Donald F. Neff advanced about 30 yards inland to locate exit routes for vehicles—a bold mission, for a night shift of Japanese was busy constructing pillboxes and trenches nearby, and their voices could be plainly heard. Noises resembling gunfire, which had been puzzling while the Marines were moving to the beaches, could now be identified as blasting charges. The enemy seemed vaguely conscious of something strange. Three Japanese sentries were observed peering down at the beach from a cliff, and a few lights flashed seaward. Though all went well for the reconnaissance teams, such imminence of danger caused a suggestion after the reconnaissance that, instead of being unarmed, the swimmers should be equipped with a lightweight pistol or revolver which could be fired even when wet. Captain Silverthorn reported that the reef at Yellow Beach appeared suitable for the crossing of LVTs and DUKWs, but the sum total of the situation at Yellow Beach was plainly unfavorable to a landing.

Exploration of White 1 and White 2

got off to a bad start. Whereas the current off Yellow Beach was negligible at the time, it was so unexpectedly rough on the northwest coast that it pushed the rubber boats off course. The men who were scheduled for White 2 landed instead on White 1, which they reconnoitered. The men headed for White 1 were swept about 800 yards to the north, where there was no beach.

Reconnaissance of White 2 was delayed, therefore, until the next night, when Company A undertook the mission, sending 10 swimmers ashore. On the previous night, the operation had been handled by the Gilmer, but this time the Stringham took the Marines and the UDT-men toward White 2, leaving the pickup to the Gilmer. Radar, which the Stringham possessed, enabled it to guide the rubber boats and to send course corrections over an SCR-300 radio.

Findings at the White Beaches were relatively encouraging. They showed that the measurements indicated by air and photographic coverage were approximately correct. White 1 proved to be a sandy beach about 60 yards wide, and White 2 more than twice that size. At the larger beach, however, there were coral barriers which averaged 3½ feet high. They formed the beach entrance and restricted it, for vehicles, to about 70 yards, though infantry could scramble over the barriers. On the beach itself was found a man-made wall sloping up about 1½ to 2 feet but judged passable by vehicles.

Primarily, the physical reconnaissance verified that LVTs, DUKWs, and tanks could negotiate the reef and land. Moreover, it showed that LCMs and LCVPs could unload on the generally smooth reef which extends about 100 yards from the shore. It appeared, however, that White 1 would be able to receive just 8 LVTs—and then only if some unloaded opposite the cliffs. At White 2, the landing of a maximum of 16 LVTs seemed possible, if about half unloaded in front of the adjacent cliffs.

While the cliffs at the White Beaches were not more than 6 to 10 feet high—lower than those at Yellow Beach—and could be scaled by ladders or cargo nets, they were nevertheless rocky and sharp and were deeply undercut at the bottom by the action of the sea. There were a number of breaks in the cliff walls at both beaches, where it appeared that Marines could land single file without aid and move inland. In effect, while the avenues of approach for amphibious vehicles were severely limited, the landing area was fairly wide—on White 1 a probable 200 yards; on White 2, 400 yards.

Marines who debarked from LCVPs on the reef would be able to wade ashore without risk underfoot except from small holes and boulders. No dangerous depths were found, nor any line of mines or man-made underwater obstacles. The scouts, however, were not equipped to detect the buried mine—not easy to set into coral but quite practical in the gravel at the shore edge.

Bearing such detailed reports, UDT and VAC Reconnaissance Battalion officers went to see Admiral Turner on board the Rocky Mount early on 12 July. They felt that landings could be made on the White Beaches, and that successful exits were possible inland.

With the reports at hand, Admiral Turner opened a meeting on board the

Rocky Mount on 12 July. He started the conference by talking about the various beaches of Tinian from a naval standpoint. General Schmidt and Admiral Hill then were asked for their opinions, and they spoke unreservedly in favor of the White Beaches, expressing the following views:–

1. landings at the Tinian Town area would prove too costly;

2. the artillery on Saipan could well support an invasion over the northern beaches;

3. capture of Ushi Point airfield, a primary objective, was immediately desirable for supply and evacuation;

4. tactical surprise might be possible on the White Beaches;

5. a shore-to-shore movement would be feasible; and

6. most supplies could be preloaded on Saipan and moved directly on wheels and tracks to inland dumps on Tinian.

Admiral Turner was agreeable to the idea. He remarked, later, that he had already become reconciled to the White Beaches and, like everyone else, was awaiting favorable reconnaissance reports. General Smith had been a pioneer advocate of the White Beaches, so now, with the consent of Admiral Spruance, the issue was settled.17

The next day, Admiral Turner released his operation plan, later promulgated as an order. Some 300 copies of the plan were circulated, starting in motion the troops and equipment which had hardly been idle since the capture of Saipan. On 20 July, Admiral Spruance confirmed J-Day as the 24th, but he authorized Admiral Hill to alter the date, if necessary, for the weather had to be right. This invasion was going to take place at the height of the summer monsoon period, a time of suddenly appearing typhoons and thunderstorms. The exacting logistical effort would require at least three calm days following the landings, a period to be forecast by Fifth Fleet weather reconnaissance.

Logistics: Plans and Problems

Logistics, indeed, formed the heart of the operation plan, for upon that branch of military art depended, more than usually, a victory on the battlefield. The invasion of Tinian was going to test whether Navy and Marine Corps amphibious tactics were sufficiently flexible. In the attempt to land and supply two divisions over a space of less than 200 yards, there would be the risk of a pile-up at the beaches, which would be tragically compounded if the hope of surprising the enemy proved false.

A great variance from normal ship-to-shore procedure would be the fact that, except for the initial emergency supplies on LSTs, all supplies were to be landed in a shore-to-shore movement from Saipan. The usual beachhead dumps were going to be out of the question. No supplies could be landed initially except those which could roll across the beaches in LVTs or DUKWs from the LSTs to inland dumps. The

supply plan also envisaged a shuttle of resupply by LCMs and LCTs carrying preloaded cargo trucks and trailers from Saipan and by several LSTs devoted to general reserve supplies. All equipment and supplies required were on Saipan except for petroleum products and certain types of food and ammunition, which were available on vessels in Tanapag Harbor.

To permit vehicular access over the coral ledges adjoining the beaches—and thus, in effect, widen them—a Seabee officer18 on Saipan designed an ingenious portable ramp carried ashore by an LVT. Six of the 10 constructed by the 2nd Amphibian Tractor Battalion were used at Tinian after being transported to the island by the LSD Ashland on the morning of the assault.

Even vehicles as heavy as the 35-ton medium tank could cross the ramp, which was supported by two 25-foot steel beams. These beams could be elevated 45 degrees by the LVT to reach the top of the 6-to-10 foot cliffs. As the LVT backed away, a series of 18 timbers fell into place on the beams, forming a deck for the ramp. The other end of the beams then dropped and secured in the ground at the base of the cliff, breaking free of the LVT. Such ramps were used to land vehicles until pontoon causeways were put into use. After 29 July, however, bad weather, caused by a “near-miss” typhoon, precluded unloading by anything but the agile and hardy DUKWs. At Tinian, the amphibian trucks were the prized supply vehicles. They were better suited to the roads than were LVTs, which clawed the earth. For the amphibian tractors, the engineers often constructed a parallel road.

The shipping and amphibious craft employed for moving troops and supplies were impressively numerous at Tinian, considering the size of the operation. Every available LST in the Saipan area, 37 of them—including a few from Eniwetok—was drafted to lift the troops of the 4th Division for the landing and the initial supplies for both Marine divisions. Ten LSTs were to be preloaded for the 4th Division, 10 for the 2nd Division, and 8 for NTLF. In command of the Tractor Flotilla was Captain Armand J. Robertson.

Most of the ships were loaded at Tanapag Harbor at whose excellent docks six could be handled in a day. Troops of the Saipan Island Command acted as stevedores. Beginning on 15 July, they loaded the top decks of the LSTs with enough water, rations, hospital supplies, and ammunition to last the landing force three and a half days. The assault Marines would not land with packs at Tinian. In their pockets would be emergency rations, a spoon, a pair of socks, and a bottle of insect repellant. Ponchos were to be carried folded over cartridge belts.

Four of the LSTs each loaded one of the 75-mm howitzer battalions on 22 July, off the Blue Beaches. Individual artillery pieces were stored in DUKWs on board to permit immediate movement to firing position by the two amphibian truck companies assigned to the 4th Division. Full use of the pack

howitzers was especially desired, for the division did not have its 105s.

Another four of the LSTs each loaded 17 armored amphibians in their tank decks while at Tanapag anchorage on 23 July. Two of these four ships carried medical gear stowed on their top decks. In fact, all of the preloaded cargo on the LSTs was placed topside, and as much as possible remained in cargo nets. On each LST were two cranes to expedite loading and unloading over the sides into LVTs and DUKWs.

Because all the LSTs were needed to lift 4th Division troops and supplies, one regiment of the 2nd Division—the 6th Marines—would remain on Saipan until 10 LSTs could unload their troops and return to Tanapag Harbor from Tinian. The 2nd and 8th Marines were to be moved on seven transports for a J-Day feint off Tinian Harbor. No general cargo was loaded on the transports, but each carried organizational vehicles of the units embarked.

On 21 and 22 July, two LSDs, the Ashland and the Belle Grove, loaded at the Charan Kanoa anchorage most of the tanks assigned to the 4th Division. The LSDs each took 18 medium tanks, each tank carried in an LCM. Their other cargo included flamethrower fuel and ammunition received from the merchant ship Rockland Victory on 19-20 July and a supply of water.

General Schmidt rounded up 533 LVTs, including 68 armored amphibians and 10 LVTs which were equipped with the special portable ramp.19 DUKWs available came to 130. Landing craft employed for the Saipan-to-Tinian lift numbered 31 LCIs, 20 LCTs, 92 LCMs, and 100 LCVPs. Nine pontoon barges were loaded on 19 July with fuel in drums received from the merchant ships Nathaniel Currier and Argonaut. These barges would be towed to positions off the reef to service amphibious vehicles and landing craft. Captured Japanese gasoline and matching lubricants were stocked on the barges. Five additional barges were loaded on 24 July from the Currier.

After the initial landing, the shuttle system for resupply would begin to operate between the 7th Field Depot dumps on Tinian. Twenty LCTs, 10 LCMs, and 8 LSTs were allotted for such use. Also assigned to the resupply system were 88 2½-ton trucks and 25 trailers.

On 22 and 23 July, 32 of the LSTs sailed into the Saipan anchorage, where they embarked LVTs, DUKWs, and troops of the 4th Division from the Blue, Yellow, and Red Beaches of Saipan. Herein lay another variance from the usual ship-to-shore movement of an island campaign, for, except for the two regiments of the 2nd Division embarked in transports, all other Marine units were moved to Tinian in LSTs or smaller craft.

The remaining five LSTs, still at Tanapag Harbor, embarked other troops and LVTs or DUKWs at the same time. Of the 20 LCTs available, 10 were designated for the 4th Division vehicles, which were loaded at the seaplane base in Tanapag Harbor on 23 July. Five additional LCTs were loaded the same day at the same place—three with medium tanks, four to each LCT, and two

with bulldozers and cranes. The remaining five LCTs were loaded in the forenoon of J-Day at the seaplane base with 2nd Division vehicles.

Of the 92 LCMs available, 36 bearing medium tanks were loaded onto the two LSDs. Ten were loaded with 4th Division armor on 23 July at the steel pier of Tanapag Harbor; these LCMs would make a direct passage. Forty-one of the remaining 46 loaded medium tanks and waited off the Blue Beaches for movement on 24 July or shortly after. Five of these LCMs moved to Tinian directly, and 36 were loaded on board the 2 LSDs when they returned from Tinian. The other five LCMs took on 2nd Division vehicles at the seaplane base on 24 July for direct transfer to Tinian. The available 31 LCIs were used to carry troops and vehicles of the 2nd Division to the 7 transports at Tanapag Harbor on 20-23 July, while the 100 LCVPs loaded 4th Division vehicles at the Green Beaches on 23 July for direct movement to Tinian.

While all such loading went on, the shore party of the 4th Division prepared for its modified task on Tinian. Usually, the shore party is responsible for first dumps off the beaches, but in this case not a pound of ammunition or other supplies could be landed on the sand. Still, there would be plenty to do. The shore party at Tinian was expected to keep supply traffic moving to the inland dumps, where some of its men would be working. It was also to provide equipment and personnel to expand and improve the beaches. Farther inland, responsibility for the trails and roads fell to Seabees of the 18th and 121st Naval Construction Battalions and to the assault engineers of the 1st Battalions of the 18th and 20th Marines.

Lieutenant Colonel Nelson K. Brown’s 4th Division Shore Party for Tinian was composed of the pioneers of the 2nd Battalion, 20th Marines on White Beach 2 and the Army 1341st Engineer Battalion on White 1. The Force Beachmaster was Commander Carl E. Anderson. The 2nd Division did not operate a shore party, since there were already enough men on hand. But a platoon of 2/18 pitched in on White Beach 2, and the rest of the battalion worked at the division dumps.

On 26 July, an NTLF Shore Party Headquarters, commanded by Colonel Cyril W. Martyr of the 18th Marines, was superimposed upon the 4th Division Shore Party. The change indicated recent attention to consolidating shore party activities. The NTLF Shore Party Headquarters, with a strength of 6 officers and 8 enlisted men, was taken from the Headquarters of the V Amphibious Corps and of the 18th Marines.

A departure from Saipan supply practice took place at Tinian, where the unit distribution system was used. Small arms and mortar ammunition were not delivered to the regiments. Instead, those units drew from the division dumps and delivered by truck to the battalions. This practice on Tinian was in keeping with logistical procedures employed on a smaller island, and, as a result, regimental supply dumps did not have to be moved as often as they were on Saipan.

Attack Plans

Because of the unusual shore-to-shore operation, involving constricted beach area, logistics monopolized much of the planning effort for Tinian. But mastery of the supply details could only enable that victory which arms must secure. In preparing for this battle, Marine commanders had a rare opportunity for reconnaissance. A number of them were taken on observation flights over the island or on cruises near its shores.

Under General Schmidt’s attack plans, the 4th Division, upon pushing inland over the White Beaches, was to seize Objective O-1, which included Mt. Maga. The main effort would be toward Mt. Lasso, reaching to a line which would include Faibus San Hilo Point, Mt. Lasso, and Asiga Point. (See Map 22.)

General Cates issued his operation order to the 4th Division on 17 July. He planned to use the 24th Marines in a column of battalions on White Beach 1 and the 25th Marines with two battalions abreast on White Beach 2. The 23rd Marines would be held in division reserve and wait immediately offshore.

Because the beaches were so narrow, only Company D of the 2nd Armored Amphibian Battalion was to be employed in the assault landing. One platoon would precede troop-carrying LVTs toward White 1, while the other two platoons led the attack against White 2. When the naval gunfire lifted, the armored amphibians would fire on the beaches and then turn to the flanks at a distance 300 yards from shore, where they would fire into adjacent areas. The first wave of Marines would continue forward to the beaches alone, except for the fire of the .30 caliber machine guns mounted on the LVTs.

The 2nd Division was to satisfy, partially, Colonel Ogata’s belief that the major landing was due in the Tinian Town area. The 2nd and 8th Marines, as part of a naval force, would execute a feint off Tinian Town at the hour of the actual landing to divert attention from the northern part of the island. Included in the show by the Demonstration Group would be the battleship Colorado, the light cruiser Cleveland, and the destroyers Remey and Norman Scott, delivering a “prelanding” bombardment. Following the demonstration off Tinian Town, the 2nd Division Marines would return northward to land on the White Beaches in the rear of the 4th Division. General Watson planned to put the 2nd Marines ashore on White 2 and the 8th Marines on White 1, while the 6th Marines would land over either beach. The command post of the 2nd Division was set up on board the assault transport Cavalier at 0800 on 23 July, as the men made ready for both a fake landing and the real thing.

The 27th Division, less its 105th Infantry and division artillery, would be ready to embark in landing craft on four hours’ notice to land on Tinian. Though Army infantry was never committed there, Army aircraft, artillerymen, amphibian vehicles, and engineers helped invaluably toward success of the Tinian operation.

The Mounting Thunder

Since 20 June, artillerymen on southern Saipan had been hammering Tinian. On 23 July, Corps Artillery fired 155 missions, and for J-Day, General Harper planned a mass bombardment by all 13 artillery battalions just before the landing—a crescendo of fire against every known installation on northern Tinian, every likely enemy assembly area, and every possible lane of approach by land to the White Beaches.

The Army Air Forces was likewise dedicated to seizing Tinian, which, of course, was to become particularly theirs. On the day before the landing, P-47s of the 318th Fighter Group flew 131 sorties against targets on the island,20 joining carrier aircraft from the Essex, Langley, Gambier Bay, and Kitkun Bay, which made 249 sorties. The same day saw the arrival of a squadron of B-25s on Saipan, which were shortly to join the battle for Tinian.

In order to permit heavy air strikes on southern Tinian on 23 July, naval gunners withheld their own fire for three periods of up to an hour. Off northern Tinian, the Colorado and the Louisville also ceased fire at 1720 to allow a napalm bombing mission on the White Beach area, where two fire bombs burned out some underbrush. The naval gunfire of 23 July, started at sunrise, was partly destructive, partly deceptive. Yellow Beach and the beaches around Sunharon Harbor received fire intended chiefly to mislead the enemy. At Tinian Town, particularly, care was taken to confuse Colonel Ogata. Minesweeping and UDT reconnaissance of the reef off Tinian Town were conducted, both without findings or incident. In fact, minesweepers operating in Tinian waters prior to the landings reported no obstacles to shipping, though, later on, 17 mines, previously located by UDT reconnaissance, were swept from Asiga Bay.

Before 1845 on 23 July, when all but a few fire support ships left the area for night retirement, the Tennessee and the California had fired more than 1,200 14-inch and 5-inch shells into the vicinity of Tinian Town, already nearly demolished. A notable fact of the naval bombardment on 23 July was the comparative sparing of the Asiga Bay coastline. It would have been folly to invite Colonel Ogata’s reserves to an area quite near the White Beaches, when it was better to keep them farther south.

After 1845, night harassing fire was assumed by the light cruiser Birmingham and five destroyers. The Birmingham and three of the destroyers covered road junctions between Faibus San Hilo Point and Gurguan Point on the western half of the island, besides shelling areas of enemy activity to the southwest. The destroyer Norman Scott was assigned to isolate road junctions on the east side of the island and the Yellow Beach vicinity.

To the rumbling of such gunfire, General Cates took the 4th Division command post on board LST 42 at 1500

on 23 July.21 Admiral Hill, in his attack order of 17 July, had fixed H-Hour at 0730. The sun would rise at 0557 on a day which would tell whether Tinian planners had gambled wisely when they picked such a landing area as the White Beaches. Another question was interjected shortly before dawn of J-Day, when a UDT mission on White Beach 2 was defeated by a squall which scattered the floats carrying explosives. The men had been sent from the Gilmer to blast boulders and destroy boat mines on the beach, the latter spotted by reconnaissance aircraft.

The squall was a phase of the rain which fell upon the assault-loaded LSTs the night of 23 July, when at 1800 they moved out to anchor. Nearby lay the line of departure, about 3,000 yards off the White Beaches, where Marines were to find every answer.