Part VI: The Return to Guam

Blank page

Chapter 1: Preparing for Guam

Plans Made—and Revised1

The battle to recapture Guam took place at the same time as the Tinian campaign, but it was the former that drew more attention from the American people. A possession of the United States since the island was taken from Spain in 1898, Guam had fallen to the Japanese just three days after Pearl Harbor.2

To regain the island was not only a point of honor; Guam was now definitely wanted for an advance naval base in the Central Pacific and for staging B-29 bomber raids upon Japan itself. Recapture of Guam had been scheduled as phase II of the FORAGER operation; it was slated to follow phase I immediately after the situation at Saipan permitted.3 In May 1944, when the preparations for Guam were taking shape, the tentative landing date was expectantly set as 18 June, three days after the scheduled D-Day at Saipan. As it turned out, however, the landings on Guam did not come until 21 July.

There were several reasons for postponing W-Day, as D-Day of Guam was called. The first was the prospect of a major naval engagement, which evolved as the Battle of the Philippine Sea. Intelligence that a Japanese fleet was headed for the Marianas had been confirmed by 15 June, and Admiral Spruance cancelled W-Day until further notice to prevent endangering the transports and LSTs intended for Guam. These vessels were then ordered to retire 150 to 300 miles eastward of Saipan.

On 20 June the Battle of the Philippine Sea was over; Japanese ships and planes were no longer a substantial threat to American forces in the Marianas. By then, however, there were other facts to consider before W-Day could be reset. Japanese resistance on

Saipan had required the commitment of the entire 27th Infantry Division, the Expeditionary Troops Reserve. The only available force was the 77th Infantry Division, which was then ashore in Hawaii.

The Marines assigned to recapture Guam had been deprived of their reserve; yet the dimensions of the approaching battle appeared to increase. Japanese prisoners and documents captured on Saipan confirmed what aerial photographs of Guam were indicating, that enemy strength on the island had been increased. Anticipating a campaign even more difficult than Saipan, Admiral Spruance saw the necessity for having an adequate reserve immediately available. At the same time, he realized that additional troops might yet be needed on Saipan, so the task force slated for Guam was retained as a floating reserve for the Saipan operation during the period 16-30 June.

Admiral Nimitz was willing to release the 77th Division to General Holland Smith as Expeditionary Troops Reserve, and on 21 June, he sent word that one regimental combat team would leave Hawaii on 1 July, with the other two following as the second echelon after transports arrived from Saipan. In a hastily assembled transport division of five ships, the 305th RCT and an advance division headquarters sailed from Honolulu on 1 July. On 6 July, General Holland Smith assigned the 77th Division to General Geiger’s control. Admiral Nimitz then sent for the 26th Marines to serve as Expeditionary Troops Reserve for Guam, and the regiment departed San Diego on 22 July.

It was Nimitz’ wish that Guam be attacked as soon as the 305th reached the area. Further postponement of the landings would give the Japanese more time to prepare. Besides that, the weather normally changed for the worse in the Marianas during late June or early July. The rainfall increased, and to the west of the islands, typhoons began to form, creating sea conditions unfavorable for launching and supporting an amphibious operation.

Just as anxious as Nimitz to avoid prolonged delay, Spruance reviewed the situation with the top commanders assigned to the Guam operation. At a meeting off Saipan on 30 June, they concurred in his judgment that “the Guam landings should not be attempted until the entire 77th Division was available as a reserve.”4 To that decision, Nimitz agreed. On 3 July, Spruance designated the 25th as tentative W-Day. On 8 July, after learning that the entire Army division would be at Eniwetok by the 18th, four days before it was expected, he advanced the date to 21 July, and there it stood.

The Fifth Fleet commander had postponed W-Day “with reluctance,”5 knowing that for the Marines due to land on Guam, it meant more days of waiting on board crowded ships under the tropical sun. Except for the replacement of the 27th Division by the 77th, the command and troop organization for the Guam campaign had not been changed, and troop movements until the middle of June had gone ahead as planned. The task

force charged with the recapture of Guam sailed from Kwajalein for the Marianas on 12 June, to act as reserve at the Saipan landings before executing its primary mission.

Command and Task Organization6

The top commands for Guam were the same as those for Saipan and Tinian. Under Admiral Spruance, commanding Central Pacific Task Forces, Admiral Turner directed the amphibious forces for the Marianas, and General Holland Smith commanded the landing forces. Guam was to involve Admiral Turner’s and General Smith’s subordinate commands, Southern Attack Force (TF 53) and Southern Troops and Landing Force (STLF). At Guam, unlike Saipan, the hard-hitting senior Marine general would not take direct command of operations ashore, but would leave it to Major General Roy S. Geiger, whose III Amphibious Corps had been designated the landing force for the Guam campaign.

In direct command of the Southern Attack Force, activated on 24 May 1944, was Admiral Conolly, who had taken Roi and Namur in the Marshalls a few months before. Admiral Nimitz had assigned to TF 53 a number of ships from the South Pacific Force, which until 10 May, had been engaged in General MacArthur’s Hollandia operation. As the attack plan for Guam envisaged simultaneous landings at two points, Admiral Conolly divided his task force into a Northern Attack Group, which he himself would command, and a Southern Attack Group, to be led by Rear Admiral Lawrence F. Reifsnider. To facilitate joint planning, Conolly and key members of his staff flew to Guadalcanal, arriving on 15 April, and set up temporary headquarters near the CP of the landing force.7

Admiral Conolly’s task force was the naval echelon immediately superior to the Southern Troops and Landing Force. That organization traced back to the I Marine Amphibious Corps (IMAC) activated in November 1942. On 10 November 1943, after the successful start of the Bougainville operation, the then corps commander, Lieutenant General Alexander A. Vandegrift, left the Pacific to become 18th Commandant of the Marine Corps. He was relieved by Major General Geiger, who had led the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing at Guadalcanal.8 On 15 April 1944, IMAC became the III Amphibious Corps (IIIAC), still under

Geiger and with headquarters on Guadalcanal.

The III Amphibious Corps consisted largely of the 3rd Marine Division, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, and Corps Artillery. The division had returned to Guadalcanal in January 1944 after its first campaign, the battle for Bougainville, and had camped at Coconut Grove, Tetere. Few command changes took place. Major General Allen H. Turnage retained command for the Guam campaign; Brigadier General Alfred H. Noble became assistant division commander, relieving Brigadier General Oscar R. Cauldwell; and Colonel Ray A. Robinson relieved Colonel Robert Blake as chief of staff, the latter assuming command of the 21st Marines. On 21 April, Colonel Blake was relieved by Lieutenant Colonel Arthur H. Butler who was promoted to colonel shortly thereafter and then led the regiment on Guam. The other regiments that comprised the division were the 3rd, the 9th, the 12th (artillery), and the 19th (engineer).

The 1st Provisional Marine Brigade was just a few months old, having been organized at Pearl Harbor on 22 March 1944, but the Marines that composed it were battle-tried men. The historic 4th Marines, with its traditions of Dominican and China service, and lastly of Corregidor,9 had been reactivated on Guadalcanal on 1 February 1944, absorbing the famed Marine raiders, veterans of fighting in the Solomons.10 Lieutenant Colonel Alan Shapley, who had commanded the 1st Raider Regiment, was assigned to command the 4th Marines; he led the regiment in the seizure of Emirau Island in March.

The other major unit in the brigade was the 22nd Marines, which had fought at Eniwetok before coming to Guadalcanal in April 1944. Colonel John T. Walker, who had commanded the 22nd in the Marshalls, became temporary commander of the brigade on 10 April 1944, when Brigadier General Thomas E. Watson, its first commander, was assigned to lead the 2nd Marine Division. On 16 April, Brigadier General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr. assumed command of the brigade, but Colonel Walker remained as chief of staff, leaving the 22nd Marines under Colonel Merlin F. Schneider. The new commander of the brigade had served with the old 4th Marine Regiment, having been its adjutant in Shanghai for a period during the 1920s. Now, with the new 4th Marines part of his command, General Shepherd arrived at Guadalcanal on 22 April from duty as ADC of the 1st Marine Division during the Cape Gloucester campaign on New Britain.

Planning for the Guam operation began immediately, but as General Shepherd later noted:–

... the limited staff provided the 1st Brigade and lack of an adequate Headquarters organization, placed a heavy load on the Brigade Commander and his Chief of Staff. Since each of the two Regiments composing the Brigade had operated independently in previous campaigns the task of molding these infantry units and their supporting elements into a unified command presented many problems to the new commander and his embryo staff in the limited time available before embarkation for the Guam operation. With customary Marine sagacity, however, plans were completed and units readied for embarkation on schedule.”11

The artillery component of IIIAC had been activated originally in IMAC on 13 April 1944 and then consisted of the 1st 155-mm Howitzer Battalion and the 2nd 155-mm Gun Battalion, in addition to the 3rd, 4th, 9th, 11th, 12th, and 14th Defense Battalions. Two days later, when IMAC was redesignated, the artillery organization became III Corps Artillery and the 2nd 155-mm Gun Battalion was redesignated the 7th.12 For the Guam operation, it was decided to employ the two 155-mm artillery battalions and the 9th and 14th Defense Battalions. Elements of the 9th were attached to the brigade, and units of the 14th would serve with the division. On 16 July, the 2nd 155-mm Howitzer Battalion of the V Amphibious Corps was added. It replaced the 305th Field Artillery Battalion (105-mm) and the 306th Field Artillery Battalion (155-mm howitzer), which were reattached to their parent 77th Division for the landing.

Named to command the III Corps Artillery was Brigadier General Pedro A. del Valle. He had led an artillery regiment, the 11th Marines, in the battle for Guadalcanal. At Guam he would have control over all artillery and antiaircraft units in the STLF. Under his command also would be a Marine observation squadron (VMO-1), equipped with eight high-wing monoplanes.

Once Guam was again under the American flag, Marine Major General Henry L. Larsen’s garrison force would begin its mission. The prospective island commander and part of his staff arrived at IIIAC headquarters on Guadalcanal on 29 May. The time proved somewhat early, considering the postponement of W-Day, but it helped to unify the total plans for Guam.

Guam, 1898-194113

The delay of the Guam landings was not without some benefits. For one thing, it permitted American military intelligence to gain a better knowledge of the island and of Japanese defenses there. The easy capture of Guam by the enemy in 1941 followed years of neglect by the United States. In 1898 the American Navy had wanted

Guam chiefly as a coaling station for vessels going to the Philippines. The other islands of the Marianas, including Saipan and Tinian, were left to Spain, which sold them the next year to Germany.14 In 1919, by the Treaty of Versailles, Japan received those islands as mandates, a fact that put Guam in the midst of the Japanese Marianas.

At this time, it seemed unlikely to many Americans that they would ever be at war with Japan. In 1923, when one of the worst earthquakes of history devastated Japan, Americans gave generously to relieve the suffering. A year before, the United States had joined with Japan, Great Britain, France, and Italy in a treaty that restricted naval armament and fortifications in the Pacific. As one result, the United States agreed to remove the six 7-inch coastal guns that had been emplaced on Guam. The last gun was removed by 1930.

Japan withdrew from the arrangement in 1936, but by then the treaty had quashed some ambitious planning by American naval officers to fortify Guam. The idea of turning the island into a major base had not been supported, however, either by the Secretary of the Navy or by the Congress, which was averse to large military appropriations.15 As late as 1938, it refused to fortify Guam.

The collapse of efforts to transform Guam from a naval station into a major naval base did not, however, put an end to preparing plans on paper. In 1921, the Commandant of the Marine Corps approved a plan of operation in the event of war with Japan. From 1936 on, officers attending the Marine Corps Schools at Quantico bent over a “Guam Problem,” dealing with capture and defense of the island.16

As for Guam, it remained a minor naval station, useful mainly as a communications center. It had become a relay point for the trans-Pacific cable, and the Navy set up a powerful radio station at Agana, the capital.17 Few ships docked at the large but poorly improved Apra Harbor. In 1936, Pan American clippers began to stop at the island, bringing more contact with the passing world. No military airfield existed, although plans were underway to build one in late 1941.

The Governor of Guam was a naval officer, usually a captain, who served also as Commandant of the United

States Naval Station. He controlled the small Marine garrison with its barracks at the village of Sumay, overlooking Apra Harbor. The Marines guarded installations such as Piti Navy Yard and the governor’s palace. Ten Marine aviators and their seaplanes had been sent to Guam in 1921, but they were withdrawn in 1931 and no others came until 13 years later.18

The American, however, is a Robinson Crusoe on whatever island he finds himself. On Guam he fostered the health of the natives, developed compulsory education, and improved the road and water supply systems. The naval administration also took some interest in the economic welfare of the island, encouraging small industries such as those manufacturing soap and ice, but avoiding interference with the farmers’ preferred old-fashioned methods. Little was exported from the island except copra, the dried meat of the ripe coconut. The largest market for native products was the naval colony itself. In addition, the Navy employed many Guamanians in the schools, the hospital, and other government departments. A heritage of that service was a devoted loyalty to the United States, which was not forgotten when war came and the Japanese occupied the island. The enemy made no attempt to use the conquered people as a military force but did press them into labor digging trenches, constructing fortifications, and carrying supplies.

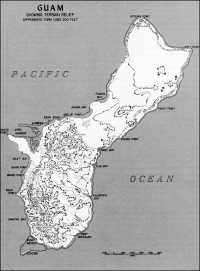

The Guamanians are a racial mixture of the original islanders—the intelligent and gentle Chamorros, a Polynesian people from Asia—and Spanish or Filipino colonists. In 1940, the governor reported the native population as 21,502. It was concentrated near the harbor of Apra; about half of the number dwelt at Agana, and another 3,800 lived in villages close to the capital. Piti, the port of entry for Agana, located about five miles southwest of it, contained 1,175 inhabitants. Asan, a village between Agana and Piti, had 656. The municipality second in size to Agana was Sumay, with a population of 1,997, on the northeast shore of the Orote Peninsula. Here, in addition to the Marine barracks and rifle range, were the headquarters of the Pacific Cable Company and of Pan American Airways. The rest of the peninsula consisted of rolling terrain, marked by tropical vegetation, with some mangrove swamps and a few coconut groves. (See Map 24).

Six other villages in the southern half of the island accounted for 5,000 of the population: Agat, Umatac, Merizo, Inarajan, Yona, and Sinajana.19 Most of the other natives lived on farms, some near rural centers like Talofofo in the south, or Dededo, Barrigada, Machanao, and Yigo in the north. Such centers included simply a chapel, a school, and a store. On the farms, most of which were located in southern Guam, the natives raised livestock, corn (the chief food staple), vegetables, rice, and fruit. Villagers, too, would sometimes have a plot of land that they tilled. The farmers took their products to market on carts

Map 24: Guam, Showing Terrain Relief

drawn by the carabao, a water buffalo.

The people of Guam were under the supreme authority of the governor, but not unhappily. They did not receive American citizenship, but they had the status of American nationals and their leaders served on the governor’s staff of advisors. When the Japanese seized the island in 1941, they tried at first to preserve the contentment of the natives.20 They offended the Guamanians, however, by changing the name of their homeland to “Omiyajima” (Great Shrine Island) and that of their capital to “Akashi” (Red or Bright Stone). The schools were ordered to teach Japanese instead of English. In 1944, as the Japanese rushed work on island defenses, they closed the schools and required labor even by children. Much of the island food supply was taken over by the expanded garrison. Native health and welfare was neglected because the Japanese became engrossed in preparing for the American invasion.

The enemy had a sizable territory to get ready. Guam is the largest island north of the equator between Hawaii and the Philippines. With an area of 225 square miles, it is three times the size of Saipan and measures 30 miles long by 4 to 8½ miles wide. The island is encircled by a fringing coral reef, ranging in width from 25 to 700 yards. For the most part, the coastline was familiar only to the native fishermen, although the United States Navy had prepared some good hydrographic charts.

Guam consists actually of two topographic entities, the north and the south, joined by a neck of land between Agana and Pago Bays. A small river starts in the Agana lowland and empties into the bay. North of that central strip, the island is largely a cascajo (coral limestone) plateau, covered with hardwood trees and dense tropical vegetation, but partly useful for agriculture. The southern half of Guam is the truly agricultural section, where streams flow through fertile valleys. Cattle, deer, and horses graze upon the hills. A sword grass, called neti, is common to the whole island.

A warm and damp air hangs over the land, but the temperature seldom rises much above the average of 87 degrees. Like the rest of the Marianas, Guam was often called “the white man’s tropics.” From July to December, however, the island is soaked by rain nearly every day. The road system became rough to travel when it rained. A mere 100 miles of hard-surfaced roads were joined by unsurfaced roads and jungle trails which turned to mud when wet.21 The main road on the island ran from Agat along the west coast to

Agana, thence northeast to Finegayan, east of Tumon Bay. There it split into two parallel branches, both ending near Mt. Machanao. Despite the high precipitation, problems of water supply had occurred until the Americans constructed some reservoirs. The water system was then centered in the Almagosa reservoirs around Agat.

A number of elevations, high and low, appear on the landscape, but there are no real mountains. Cliffs rim the shoreline of the northern plateau, from Fadian Point to Tumon Bay. Above the tableland itself Mt. Santa Rosa (840 feet) rises in the northeast. At the center of the plateau is Mt. Mataguac (620 feet), and near the northern tip lies Mt. Machanao (576 feet). Marking the southern edge of the plateau, Mt. Barrigada rises to 640 feet, and from its slopes a 200-foot bluff reaches west to upper Agana Bay. These hills are not so high as those of southern Guam, but they are comparably rocky at the top and covered on the sides with shrubs and weeds.

A long mountain range lies along the west side of southern Guam from Adelup Point south to Port Ajayan at the tip of the island. Parts of the mountain range, such as Chonito Cliff near Adelup Point, rise very close to the shore. Inland of Apra Harbor is a hill mass, with a maximum height of 1,082 feet. Here are Mt. Chachao, Mt. Alutom, and Mt. Tenjo. The highest hill on Guam—Mt. Lamlam (1,334 feet)—rises from the ridge line below the Chachao–Alutom–Tenjo massif. Conspicuous in the ridge, which starts opposite Agat Bay, are the heights of Mts. Alifan and Taene. Near Agana Bay and the central lowland, which links northern and southern Guam, lies Mt. Macajna. Several prominent points of land that figured in the fighting jut from the west coast of the island—Facpi, Bangi, Gaan, Asan, and Adelup. On the northern end are Ritidian Point and Pati Point. The largest island off the coast is Cabras, a slender finger of coral limestone about a mile long; the island partly shelters Apra Harbor. Others, like Alutom, Anae, Neye, and Yona, are hardly more than islets. Rivers are numerous on Guam but most of them are small. The Talofofo and the Ylig are difficult to ford on foot, but others are easy to cross except when they are flooded.

Such geographic forms were known to Navy and Marine officers that had been stationed on Guam, and from those men was gleaned much of the intelligence necessary for planning the operation. Other sources were natives that were serving in the United States Navy at the time the Japanese seized Guam. Despite the fact that Guam had been an American possession for almost a half-century, the sum total of knowledge held by American authorities concerning the island was relatively small. In February 1944, the Office of Naval Intelligence issued a useful “Strategic Study of Guam;” the data was compiled by Lieutenant Colonel Floyd A. Stephenson, who had served with the Marine garrison on the island, and who returned in July 1944 as Commanding Officer, IIIAC Headquarters and Service Battalion.

The Marine Corps Schools had prepared some materials in connection with the “Guam Problem,” and its map of the island was of particular use. It

formed the basis of the maps drawn by the Joint Intelligence Center, Pacific Ocean Areas and furnished to the III Amphibious Corps. The cartographers at the Marine Corps Schools had worked from ground surveys made by Army engineers, but the Corps C-2 complained that the contours on the maps they received “did not portray anything like a true picture of the terrain except in isolated instances.”22 The road net, they said, was “generally correct” but did not show recent changes or roads built by the Japanese.

To correct such omissions and errors, aerial photography was called for. The first photo mission, flown on 25 April 1944, suffered the handicap of cloud cover, but subsequent flights in May and June produced somewhat better results, and photographic reconnaissance was kept up until after the landings. A naval officer, Commander Richard F. Armknecht, who had been a public works officer on Guam, prepared an excellent relief map, based largely upon his own thorough knowledge of the terrain. Admiral Conolly was so impressed with the map that he ordered several more made to give the fire support ships for study. By these means, information about the island was expanded, but knowledge of it was still deficient, especially regarding the areas of vegetation and the topography.23

Intelligence of the coastline was obtained by a submarine and by UDT men. The USS Greenling got some good oblique photographs of the beaches and also took depth soundings and checked tides and currents. The underwater demolition teams started their reconnaissance and clearing of the assault beaches on 14 July. The men destroyed 940 obstacles, 640 off Asan and 300 off Agat; most of these were palm log cribs or wire cages filled with coral. Barbed wire was sparsely emplaced, however, and no underwater mines were found. On the reef that men of the 3rd Division would cross, the UDT men put up a sign: “Welcome, Marines !”24

The Japanese on Guam, 1941-194425

The size of the Japanese force and the state of its recent defenses indicated that the enemy did not plan a

cordial welcome for the Marines.26 After the Japanese seized Guam in 1941 they undertook no better preparation to defend it than the Americans had done. The enemy left only 150 sailors on the island—the 54th Keibitai, a naval guard unit. Guam and other isolated Pacific islands were regarded merely as key points of the patrol network, not requiring Army troops for defense.

In late 1943, Japan became fearful of an American push through the Central Pacific and put new emphasis upon defense of the Marianas. As a result, the 13th Division, which had been fighting in China since 1937, was slated for duty in the Marianas. In October 1943, an advance detachment of about 300 men sailed for Guam, but military developments in south China prevented the sending of the rest of the division. Instead, the 29th Division was substituted. It took up the great responsibility indicated by advice from Tokyo: “The Mariana Islands are Japan’s final defensive line. Loss of these islands signifies Japan’s surrender.”27

The 29th Division had been a reserve for the Kwuantung Army. In February 1944, while undergoing anti-Soviet combat training in Manchuria, the unit received its marching order for the Marianas. Horses were left behind,28 the troops were supplied with summer uniforms, and on 24 February the division embarked in three ships at Pusan, Korea. On board the Salcito Maru was the 18th Infantry Regiment; on another ship, the 50th Infantry Regiment; and on the third, the 38th Infantry Regiment and division headquarters.

Disaster befell the Salcito Maru when it was just 48 hours’ sailing distance from Saipan. The American submarine Trout sank the ship by a torpedo attack at 1140 on 29 February. The regimental commander and about 2,200 of the 3,500 men on board ship were drowned. In addition, eight tanks and most of the regimental artillery and heavy equipment were lost.29 The two destroyers of the convoy picked up survivors and took them to Saipan, where the 18th was reorganized. The 1st Battalion stayed on Saipan, and the tank company went to Tinian. The regimental headquarters, newly commanded by Colonel Hiko-Shiro Ohashi, and two battalions were sent to Guam, arriving there on 4 June. The regiment brought along two companies of the 9th Tank Regiment. The two infantry battalions each had three rifle companies, a trench mortar company (seven 90-mms), and a pioneer unit. Minus the battalion on Saipan, the regiment numbered but 1,300 men after the reorganization.

The 50th Infantry Regiment went to Tinian. Division headquarters, with Lieutenant General Takeshi Takashina

commanding, and the 38th Infantry Regiment (Colonel Tsunetaro Suenaga) proceeded to Guam, arriving there on 4 March. This regiment numbered 2,894 men and included signal, intendance (finance and quartermaster), medical, transport, and engineer units. Its three infantry battalions each contained three rifle companies, an infantry gun company, and a machine gun company. Attached to each infantry battalion was one battery of 75-mm guns from the regimental artillery battalion.

The second largest Army component sent to Guam was the 6th Expeditionary Force, which sailed from Pusan and reached Guam on 20 March. This unit totaled about 4,700 men drawn from the 1st and 11th Divisions of the Kwantung Army; it comprised six infantry battalions, two artillery battalions, and two engineer companies. On Guam, the force was reorganized into the 2,800-man 48th Independent Mixed Brigade (IMB), under the command of Major General Kiyoshi Shigematsu, who had brought the force to the Marianas, and the 1,900-man 10th Independent Mixed Regiment (IMR), commanded by Colonel Ichiro Kataoka.

The infantry battalions of the 48th IMB and the 10th IMR included three rifle companies, a machine gun company, and an infantry gun company (two 47-mm antitank guns and either two or four 70-mm howitzers). The infantry battalions of the 38th Regiment had the same organization, except that the gun company had four 37-mm antitank guns and two howitzers.

The total number of Army troops, including miscellaneous units, came to about 11,500 men.30 The overall command of both Army and Navy units on Guam went to General Takashina, whose headquarters strength was estimated at 1,370. Upon arrival on the island, he had been given the Southern Marianas Group, which included Guam and Rota, and, after the fall of Saipan, also Tinian. Defense of the entire Marianas was the responsibility of General Obata, commander of the Thirty-first Army, into which the 29th Division had been incorporated, but the general left the immediate defense of Guam to the division commander.

In February 1944, the Japanese naval units on Guam had comprised about 450 men. From then on, however, the 54th Keibitai was steadily reinforced by additional coast defense and antiaircraft units, so that by July the organization totaled some 2,300 men commanded by Captain Yutaka Sugimoto, once island commander. Two naval construction battalions had 1,800 men relatively untrained for fighting. With nearly 1,000 miscellaneous personnel, the figure for naval ground units reached about 5,000. Naval air units probably held some 2,000 men.31 Most accounts agree that the entire Japanese troop strength on

Guam totaled a minimum of 18,500 men.32

On 23 June, the 1st Battalion of the 10th IMR, with one artillery battery and an engineer platoon attached, moved to Rota for garrison duty. Shortly thereafter, the battalion was joined by a task force composed of the 3rd Battalion, 18th Regiment, supporting engineers, and amphibious transport units; the object, a countermanding on Saipan. The condition of the sea made such a mission impossible, however, so 3/18 returned to Guam on 29 June. The 1st Battalion, 10th IMR remained on Rota, but since it could possibly be transferred in barges to Guam, both American and Japanese listings included it as part of defensive strength of the larger island.

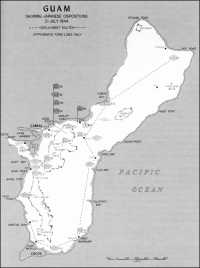

Documents showing enemy strength figures and unit dispositions fell into American hands with the capture of Thirty-first Army headquarters on Saipan. Such information helped IIIAC intelligence officers prepare a reliable sketch map indicating the main Japanese defensive dispositions as of late June. General Takashina had set them up on the premise that the landing of a division-level unit was possible on beaches in the Tumon Bay-Agana Bay-Piti coastal section and the beach of Agat Bay. The Japanese were expecting four or five American divisions, a force adequate for landing operations at two fronts. (See Map 25.)

The enemy’s immediate concern was the defense of Apra Harbor and of the island airfields. Construction of a military airfield near Sumay on the Orote Peninsula (occupying the golf course of the former Marine Barracks) had not been started until November 1943. The Japanese based about 30 fighter planes here. In early 1944, construction was begun on two other airfields, one at Tiyan near Agana and the other in the vicinity of Dededo. The Tiyan (Agana) airfield became operational by summer. This was intended for use by medium attack planes; the Japanese had six of those on the island.

Assigned to the Agana sector, which covered that part of the west coast from Piti to Tumon Bay, were the four infantry battalions of the 48th Brigade. The 319th Independent Infantry Battalion was positioned inland, east of Agana, in reserve. The 320th Battalion manned defenses near the coastline between Adelup Point and Asan Point. The 321st Battalion was located around Agana Bay, and the 322nd Battalion at Tumon Bay. The Agana sector received most of the Army artillery: the brigade artillery unit and the two artillery batteries of the 10th IMR, all under the control of the 48th IMB.33 In the Agana sector also were naval land combat troops holding the capital city, most of the 29th Division service troops, and General Takashina’s command post at Fonte. The 3rd Battalion, 38th Infantry, initially stationed in reserve behind the 48th Brigade positions, was returned to Colonel Suenaga’s control in July and moved south to rejoin its regiment.

The rest of the 38th Infantry had

Map 25: Guam, Showing Japanese Dispositions, 21 July 1944

been put into the Agat sector, which stretched along the coast between Agat Bay and Facpi Point, with 1/38 covering the Agat Beach area. Colonel Suenaga’s command post was located on Mt. Alifan. The Agat sector included the Orote Peninsula, where most of the naval infantry, the 60th Antiaircraft Defense Unit, and coast defense elements of the 54th Keibitai were stationed; 2/38 occupied the base of the peninsula. Completing the troop organization for the peninsula was the 755th Air Group, which had reorganized its 700 men for ground combat.

Until General Takashina was fairly sure where the unpredictable Americans would land, he kept some troops in other parts of the island. Stationed in southeast Guam until July was the 10th IMR (less 1/10 on Rota). In extreme northern Guam was the 2nd Battalion, 18th Regiment. The 3rd Battalion of the regiment, after failing to get to Saipan, took up defense positions between Piti and Asan Point in the Agana sector. General Shigematsu, commanding the 48th IMB, had the responsibility for island defense outside the Agat sector, which was under Colonel Suenaga.

In early July, the Japanese virtually abandoned other defense positions and began to localize near the expected landing beaches on the west coast. The 10th IMR went to Yona, thence to positions in the Fonte-Ordot area—ominously near the Asan beaches. The 9th Company of the regiment was ordered into a reserve position near Mt. Alifan to lend support to the 38th Regiment. Most of the 2nd Battalion, 18th Regiment was brought south to back up the 320th Independent Infantry Battalion; the 5th Company of 2/18 was put to work constructing defenses in the hills between Adelup Point and Asan Point. These troop movements, made mostly at night, were handicapped by the American bombardment.

The enemy’s armor was shifted around as the Japanese got ready. The tank units were positioned in reserve, prepared to strike the beachhead with the infantry. One was the 24th Tank Company, assigned as the division tank unit, with nine light tanks (eight of its tanks had been lost in the sinking of the 18th Regiment transport). That company was put at Ordot, inland of Fonte. The 2nd Company, 9th Tank Regiment, with 12 to 14 tanks, mostly mediums, was turned over to the 48th IMB. The 1st Company, 9th Tank Regiment, with 12 to 15 light tanks, was assigned to the 38th Regiment and took up a position to the rear of the Agat beaches.

The Japanese fortification of Guam was, like the buildup of manpower on the island, a hasty development. Before the 29th Division was stationed here, the enemy had only a few batteries on the island, and these were not dug in. The principal armament consisted of 75-mm field guns, the largest caliber artillery was 150-mm. Two cave-type dugouts for the communications center at Agana were under construction, and a concrete naval communications station was being built at Fonte.

In the fever of preparations after 1943, the Japanese armed the ground from Tumon Bay to Facpi Point, providing concrete pillboxes, elaborate trench systems, and machine gun

emplacements. Mortars, artillery, and coast defense guns were positioned along the coast. The number of antiaircraft weapons was increased; the 52nd Field Antiaircraft Battalion was assigned to the Orote airfield and the 45th Independent Antiaircraft Company to Tiyan. In the defense of the Orote Peninsula, the 75-mm antiaircraft guns of the 52nd could serve as dual-purpose weapons, augmenting the artillery.

An unfortunate result of the postponing of W-Day was the extra time it afforded the Japanese to prepare. They overworked the naval construction battalions and native labor to bulwark the island, mostly in the vicinity of the beaches and the airfields. Some inland defenses were constructed, however, and supply dumps were scattered through the island.

American photo reconnaissance between 6 June and 4 July showed an increase of 141 machine gun or light antiaircraft positions, 51 artillery emplacements, and 36 medium antiaircraft positions. Better photographs may have accounted for the discovery of some of the additional finds; still, the buildup was remarkable considering the short period involved. The number of coast defense guns, heavy antiaircraft guns, and pillboxes had increased appreciably also. The distribution of weapons to Army forces on Guam was indicated from a captured document dated 1 June 1944:–

14—105-mm howitzers

10—75-mm guns (new type)

8—75-mm guns

40—75-mm pack howitzers (mountain)

9—70-mm howitzers (infantry)

8—75-mm antiaircraft guns (mobile)

6—20-mm antiaircraft machine cannon

24—81-mm mortars

9—57-mm antitank guns

30—47-mm antitank guns

47—37-mm antitank guns

231—7.7-mm machine guns

349—7.7-mm light machine guns

540—50-mm grenade dischargers34

Of grim significance in the enemy’s defensive organization was their intention to deny land access to Orote Peninsula. A system of trenchworks and foxholes was constructed in depth across the neck of the peninsula and supported with large numbers of pillboxes, machine gun nests, and artillery positions. Rocks and tropical vegetation provided concealment and small hills lent commanding ground.

The Preparatory Bombardment35

If the postponing of W-Day permitted the Japanese to put up more defenses, it also gave American warships and planes time to knock more of them down. Beginning on 8 July, the enemy was subjected to a continuous 13-day naval and air bombardment. It was the wholesale renewal of the first naval gunfire on 16 June, when two battleships, a cruiser, and a number of destroyers from Task Force 53 shelled the Orote Peninsula for some two hours, exciting Japanese fears of imminent invasion. Planes from Task

Force 58 had started bombing Guam on 11 June, hitting the enemy airfields particularly; by 20 June, the Japanese planes based there had been destroyed and the runways torn up.36 On 27 June, Admiral Mitscher’s airmen bombed Japanese ships in Apra Harbor. Then, on 4 July, destroyers of TF 58 celebrated the day by exploding 5-inch shells, like giant firecrackers, upon the terrain in the vicinity of Agana Bay, Asan Point, and Agat Bay.

Such gunfire, however, was a mere foretaste of what was to come from the sea and air. On 8 July, Admiral Conolly began the systematic bombardment, day after day, which was to assume a scale and length of time never before seen in World War II.37 Destroyers and planes struck at the island, and on 12 July they were joined by battleships and cruisers. Two days later, Admiral Conolly, arriving in his command ship, the Appalachian, took personal charge of the bombardment. From then on it reached, the Japanese said, “near the limit bearable by humans.”38 The incessant fire not only hindered troop and vehicle movements and daytime work around positions, but it also dazed men’s senses.39

Admiral Conolly, justifying his nickname “Close-in,” took his flagship to 3,500 yards from the shore and went to his task with dedication. “He made a regular siege of it,” wrote a naval historian.40 On the Appalachian, a board of Marine and Navy air and gunnery specialists kept a daily check of what had been done and what was yet to be done. General Geiger, who was on board with Conolly, said that “the extended period of bombardment, plus a system of keeping target damage reports, accounted for practically every known Japanese gun that could seriously endanger our landing.”41 It was the belief of Admiral Conolly’s staff that “not one fixed gun was left in commission on the west coast that was of greater size than a machine gun.”42

Every exposed naval battery was believed destroyed; more than 50 percent of the installations built in the seashore area of the landing beaches were reported demolished.43 A number of guns emplaced in caves, with limited fields of fire, were reduced in efficiency when naval shells wrecked the cave entrances. Some permanent constructions, however, which were thickly walled with concrete and cascajo, and at least partially dug into the earth, resisted even a direct hit.

Certain installations and weapons escaped. The Japanese reported later that their antiaircraft artillery on

Guam “sustained damage from naval gunfire only once,”44 and only once did water pipes receive a direct hit. Communications installations were constructed in dead spaces immune to bombardment, and practically no lines were cut by naval gunfire. Moreover, no damage was done to power installations because generators were housed in caves. The interior of the island was, of course, less the province of ships’ guns than of roving aircraft; the Japanese claimed that naval gunfire had very little effect beyond four kilometers (roughly, two miles) from the shoreline. It thus did little damage to enemy construction in the valleys or the jungle.

While air bombardment and strafing was able to reach where naval gunfire could not, the Japanese mastery of the art of concealment still hampered destruction. On 28 June, Admiral Mitscher’s aircraft began periodic strikes against Guam; then on 6 July, TF 58 and two carrier divisions of Admiral Conolly’s TF 53 started the full-scale preparatory air bombardment. Targets included supply dumps, troop concentrations, bridges, artillery positions, and boats in military use. Most such craft were sunk by strafing, the rest by naval gunfire. Harbor installations were spared for use after the battle. In the period of the preparatory bombardment, the island was divided into two zones—naval gunfire and air alternated zones morning and afternoon. Aircraft were particularly useful at hindering Japanese troop movements; they were less effective against enemy gun emplacements.

On 12 July, before leaving Eniwetok for Guam, Admiral Conolly met with Admiral Mitscher, and they set up a schedule of intensified strikes, which were to take place from 18 July through W-Day. Mitscher greatly increased the number of aircraft available to Conolly for the final all-out attacks. Until 18 July, TF 58 had made strikes on Guam independently of Commander, Support Aircraft, Guam. For the period 18-20 July, the combined tonnage reached the figure 1,131, including bombs, depth charges, and rockets. The explosives were not delivered, however, without some losses to American aircraft. Sixteen naval planes were brought down by the Japanese antiaircraft fire before W-Day.

Japanese Fortune Telling45

It was the focus of the intensified bombardment starting 18 July which tipped off American intentions. From the action of the ships at sea, rather than from any leaves in a teacup, the Japanese were able to foretell more specifically where the invaders would come ashore.46 When UDT men

cleared obstacles from the chosen beaches, all doubt was removed.

In 1941, the Japanese had landed their main force at Tumon Bay, so at first they had supposed the Americans would attempt the same; the beach was ideal for an amphibious assault (at least two miles of sand), the reef was not impassable, and inland the ground rose gently. This judgment regarding the Tumon beaches did not give much weight to the factors that decided American planners against them—their distance from Apra Harbor and the highly defensible terrain that blocked the way to the harbor.

The enemy had not, however, really expected a repetition of their other landings elsewhere on the island, where neither the surf nor the ground was appropriate for a large-scale invasion. It was not until the middle of June, when the Americans began shelling the beaches below Tumon Bay, that the Japanese gave serious attention to fortifying the west coast south of the bay. Before then, they had viewed as dismaying to an invader the wide reef protecting the beaches here—”a reef varying in width from 200 to 500 yards offshore.”47 Moreover, on the commanding ground just inland, the defenders would have excellent observation for mortar and cannon fire,

As late as 16 July, General Shigematsu regarded the Agana sector as the probable area of invasion, with the Agat sector as a second target area if a two-front attack were staged. A landing force at Agat Bay could seize the Orote airfield. The white sandy beach along most of Agat Bay was comparable to that of Tumon Bay. Before the American bombardment shattered the picture, the beach was fringed with palm trees. The northern coastline of Agat Bay, along the Orote Peninsula, is different, however; there a fringe of cliffs ranges from 100 to 200 feet high.

The Japanese did not rule out a possible small American landing at Pago Bay on the east coast for the purpose of getting behind their lines, but General Takashina’s defense efforts were almost wholly devoted to the west coast. Imperial General Headquarters doctrine insisted upon the destruction of the assault forces at the beaches, though Lieutenant Colonel Hideyuki Takeda, the perceptive operations officer of the 29th Division, favored a deployment in depth at Guam.48 If the Japanese beach defense units should fail to destroy the American landing force at the beaches, General Takashina had instructed the 10th IMR and the two battalions of the 18th Regiment to counterattack in force.

American Tactical Plans49

American tactical spadework for the assault on STEVEDORE, the code

name assigned to Guam, had been started at Pearl Harbor as early as March 1944. General Geiger’s staff prepared the tentative operation plan, which was approved by General Holland Smith on 3 April and shortly after by Admirals Turner and Spruance. The working out of details went forward on Guadalcanal, where, with the establishment of the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade command post on 2 May, every major unit of the corps was present.

On 17 May, General Geiger circulated the corps operation plan. As originally evolved at Pearl Harbor, it provided for a 3rd Marine Division landing on beaches between Adelup Point and Asan Point, while to the south the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade was to go ashore between Agat village and Bangi Point. Subsequent junction of the beachheads was planned.

Early capture of the Orote Peninsula-Apra Harbor area was imperative to secure the use of the harbor and the Orote airfield. Here was, as General Holland Smith said, “the focal point of attack.”50 Upon General Shepherd’s brigade fell the hard assignment of seizing the Orote Peninsula, a rock-bound fortress. In order to free the brigade for such a mission, the 305th Infantry of the 77th Division was attached on 10 July to follow the brigade ashore, while the rest of the Army division remained as corps reserve.51 Major General Andrew D. Bruce, commanding the 77th, wanted to use his other two regiments for a secondary landing on northwest Guam about W-Day plus four to attack the Japanese rear, but it was felt that the Army troops should be kept in reserve, available for support at the beachheads.

The 305th Regiment was to relieve the brigade on the Force Beachhead Line (FBHL), which extended from Adelup Point along the Mt. Alutom–Mt. Tenjo–Mt. Alifan ridge line to Facpi Point. The brigade could then reorganize for the attack on the Orote Peninsula. Once that area was secured, the brigade would again take over the defense of the FBHL, while Army troops joined with the 3rd Marine Division in seizing the rest of Guam.

The two assault points were five miles apart, creating the situation of two almost separate military operations by the same landing force. Owing to this distance, each of Admiral Conolly’s two attack groups, northern and southern, would land and support its own assault troops.

In the north, the three regiments of the 3rd Marine Division would land abreast on a 2,500-yard front—the 3rd Marines on Beaches Red 1 and 2, the 21st Marines in the center on Beach Green, and the 9th Marines on Beach Blue. At one end of the front jutted Adelup Point and at the other, Asan Point; both had cave-like holes appropriate for enemy machine gun positions. Beyond the beaches lay dry rice paddies, yielding to the Fonte Ridge which overlooked the landing area. On 15 July, General Shigematsu moved his battle command post to this high ground. (See Map VII.)

The 1st Provisional Marine Brigade would go ashore with two regiments abreast—the 22nd Marines on Yellow Beaches 1 and 2; the 4th Marines on White Beaches 1 and 2, to the south. These beaches stretched more than a mile between Agat village and Bangi Point, with Gaan Point at the middle. The cliffs of the Orote Peninsula 2,000 yards to the north flanked the landing area. Neye Island, just off the peninsula, and Yona Island, near the White Beaches, rose from the water like enigmatic bystanders, probably carrying hidden weapons.

Two 155-mm battalions of the III Corps Artillery were to land behind the brigade, whose artillery group included the 75-mm pack howitzer battalion of each regiment and two other units to be attached on landing—the Army 305th Field Artillery Battalion and Battery C, 1st 155-mm Howitzer Battalion. Artillery support for the 3rd Division would be provided by the 12th Marines, comprised of two 75-mm pack howitzer battalions and two 105-mm howitzer battalions. The fires of the 12th Marines were to be reinforced by the 7th 155-mm Gun Battalion firing from the southern beachhead, while the brigade artillery group would be backed up by the 1st 155-mm Howitzer Battalion.

Logistics52

The 105-mm howitzers would be taken ashore in amphibian trucks of the IIIAC Motor Transport Battalion, which had been converted to a DUKW organization for Guam. DUKWs would also carry radio jeeps, 37-mm antitank guns, and infantry ammunition; after that, they would be used for resupply. Of the 100 amphibian trucks in the battalion, the 40 of Company C were assigned to the brigade, while the remaining 60 would support the 3rd Division.

Other supplies would be moved by amphibian tractors from the reef edge across the beaches to dumps inland. The 180 LVTs of the 3rd Amphibian Tractor Battalion would serve the Marine division; the 4th Amphibian Tractor Battalion, with 178 LVTs, was attached to the brigade.53 After the securing of the beaches, LSTs would anchor at the reef edge for unloading.

At the northern beaches the reef was dry at low water, and trucks would be able to run out from the shore to the edge. At the southern beaches the water over the reef was always too deep for trucks to operate; LVTs and DUKWs would have to bear the cargo, risking the usual coral heads and potholes.

Neither reef was covered at any time with water deep enough for shallow draft craft to pass over. In fact, nowhere along the entire coastline of Guam was the reef covered at high tide by more than two feet of water. Cranes could be operated on the northern reef, but only those cranes that

were mounted on pontoon barges would be usable on the southern reef. Forty-four 9 x 21-foot barges and twelve 6 x 54-foot pontoon causeways were to be carried to Guam on the sides of LSTs to save deck space for troop cargo; brackets for that purpose were installed on 17 of the landing ships.

Task Force 53 mounted out in the Solomons, where ships drew upon the storage dumps at the Naval Base, Tulagi, and the floating storage in Purvis Bay. The transports anchored close to Cape Esperance and Tetere, Guadalcanal, to be near the Marine camps to facilitate training and combat loading. Kwajalein and Roi Islands in the Marshalls served as the staging area, but owing to the postponement of W-Day it was necessary to restage at Eniwetok. The restaging involved topping off with fuel, water, provisions, and ammunition.

Adequate shipping had been provided to lift the units originally assigned to IIIAC, but additional units to be embarked required some reductions of cargo, particularly vehicles. On 4 May, for instance, Admiral Conolly was directed to take on board the entire first garrison echelon, comprising 84 officers and 498 enlisted men, an addition that somewhat complicated the allotment of space between assault and garrison troops.

In general, the logistic planning for operations on the large island of Guam had been so efficiently accomplished that no serious difficulty arose. The shipping available for FORAGER was never really enough, but miracles of adjustment were performed. Square pegs were practically fitted into round holes, and the distances between Guadalcanal and the chief sources of supply at Pearl Harbor, Espiritu Santo, and Noumea were telescoped by fast ships.

Outstanding and new in the logistic preparation for Guam was the IIIAC Service Group, an organization used again later at Okinawa. Staffs of the Corps Engineer and Corps Quartermaster formed the nucleus of the group, which shortly after W-Day, would include personnel of the engineer, construction, medical supply, and transport services. The Corps Engineer, Lieutenant Colonel Francis M. McAlister, was assigned to command the group; he would supervise the corps shore party operations once the Japanese port facilities had been seized. Until the garrison commander took over, the Service Group would operate the port to be established in Apra Harbor and also the airfields to be built. In a word, no time was going to be lost in transforming Guam into an advance base.

For landing the mountain of supplies, the harbor offered Piti Navy Yard and the seaplane ramp at Sumay as the best unloading points, at least at the start. The corps shore party planned to operate Piti with the 2nd Battalion, 19th Marines, and Sumay with the two pioneer companies of the brigade. Two naval construction battalions, the 25th and the 53rd, had been attached to IIIAC; initially the Seabees, along with corps engineers, would develop the road net in the beachhead area. After the battle was over, the 5th Naval Construction Brigade, comprised of three regiments, would begin its work under the Island Command.

Essential to the ambitious plans for developing a base, however, was the recapture of the island. The American

ground forces to be engaged totaled 54,891 men:

| 3rd Marine Division | 20,328 |

| 1st Provisional Marine Brigade | 9,886 |

| 77th Infantry Division | 17,958 |

| III Amphibious Corps Troops | 6,719 |

Source: 54

A provisional replacement company (11 officers and 383 enlisted men) embarked with the assault troops. The unit would help with unloading until its men were needed to replace combat losses. A provisional smoke screen unit, formed to augment a Seabee battalion, was also to be available for frontline combat.55 For the handling of casualties, the landing force had a corps medical battalion, which embarked with equipment and supplies to operate a 1,500-bed field hospital. In addition, there were two medical companies with the brigade and the division medical battalion. The 77th Division would bring an Army field hospital.

As at Saipan, the APAs would bear the initial casualty load from the beach assault. After treatment by frontline medical personnel, wounded men would be taken either by stretcher bearers or ambulance jeep to the beaches, where they would be received by beach medical parties and placed in an LVT or DUKW for movement to transports and LSTs equipped and staffed to handle the casualties.

Training and Sailing56

Most of the Marines that would fight on Guam were veterans of recent combat and experienced in an amphibious operation, but training on Guadalcanal was none the less intensive. Emphasis lay upon development of efficient tank-infantry teams. From 12 to 22 May, training included six days of ship-to-shore practice (three for each attack group), two days of air support exercises in conjunction with regimental landings, and two days of combined naval air and gunfire support exercises. On the 22nd, the Northern Attack Group sortied from Guadalcanal and Tulagi, cruised for the night, and then made its approach to the rehearsal beach at Cape Esperance. All assault troops and equipment of the 3rd Division were landed, supported by air and naval gunfire bombardment. Only token unloading of heavy equipment, such as tanks and bulldozers, was made. The Southern Attack Group conducted a similar rehearsal in the same area during 25-27 May. The practice was particularly designed to test communications and control on the water and on the shore.

Training on Guadalcanal was somewhat

handicapped because the island has no fringing reef, such as would be encountered at Guam. In the ship-to-shore phase, troops had to practice transferring from boats to tractors at an arbitrary point simulating the edge of the reef. Reality was lent to the rehearsals, however, by the use of live bombs and ammunition in the naval air and gunfire support exercises.

The Army troops due for Guam went straight from Hawaii to their staging area at Eniwetok, so they did not take part in the IIIAC training on Guadalcanal. The 77th Infantry Division had not yet experienced combat, but the men had been schooled in amphibious warfare, desert and mountain warfare, village fighting, and infiltration tactics at Stateside camps and then had spent some time at the Jungle Training Center on Oahu.57 The 305th Infantry Regiment joined Task Force 53 at Eniwetok on 10 July, and the remainder of the 77th Division reached there a week later.

Marines of the 3rd Division, their dress rehearsals over, embarked on transports and LSTs from docks at Tetere. Other ships loaded brigade troops at Kukum. On 1 June, the tractor groups left for the staging area. at Kwajalein. The faster transport and support groups of TF 53, which included the Appalachian with IIIAC Headquarters on board, followed on 4 June. The ships stayed in the Marshalls long enough to take on fuel, water, and provisions and to transfer assault troops from transports to landing ships. By 12 June, Admiral Conolly’s entire task force had left in convoy formation, bound for the Saipan area. For 10 days, from 16 June, Marines waited on board ships near Saipan, retiring every night and returning every morning, to be ready in the event they were needed on shore. On 25 June, Admiral Spruance sent ships of the Northern Transport Group, which was carrying the 3rd Marine Division, to a restaging area at Eniwetok, but he detained the brigade for five more days before returning it to the Marshalls.

Among the Marines sidetracked at Eniwetok were men of Marine Aircraft Group 21. On 4 June, the forward echelon of MAG-21, then attached to the 4th Marine Base Defense Aircraft Wing, had sailed from Efate in the New Hebrides for Guadalcanal, expecting to go on to Guam. The pilots of Marine Corsairs were prepared to fly close support missions on Guam once Orote airfield was secured and made ready. To their dismay, the men were kept on board ship at Eniwetok from 19 June to 23 July.

While the ships lingered at Eniwetok, Marines were debarked, a few at a time, for exercises on sandy islets of the lagoon, but that was hardly a respite from the average of 50 days that troops had to spend on board the hot and overcrowded ships before getting off at Guam. Marines tried to shield themselves from the burning sun by rigging tents and tarpaulins on the weather decks of LSTs. As was common on every troop ship in the Pacific, men would leave the stuffy holds to seek a cool sleeping spot topside. In the ships

due for Guam, there were several platoons of war dogs, who shared the discomfort of the voyage but were not bothered by the dwindling supply of cigarettes. A variation of shipboard monotony occurred on 17 June when a formation of Japanese torpedo bombers approached the Northern Tractor Group; the attackers were turned away by the fire of LSTs and LCTs, which shot down three of the enemy planes. One of the prized LCI(G)s was hit; the gunboat was taken under tow, but finally had to be sunk by destroyer gunfire.58

General Geiger reported that “contrary to popular opinion, this prolonged voyage had no ill effect upon the troops.”59 Nevertheless, everyone breathed a sigh of relief when finally, beginning on 11 July, elements of Task Force 53 again sailed for Guam. The bulk of the troops, including RCT 305, departed in transports on 18 July. The ships which had been sent from Saipan to Pearl Harbor to pick up RCTs 306 and 307, arrived at Eniwetok just before the main force got underway for Guam. They continued on their long voyage to the objective on the 19th. On 20 July, the Indianapolis, bringing Admiral Spruance, joined the great task force, and, on the same day, Admiral Turner and General Holland Smith departed Saipan in the Rocky Mount to observe the Guam landings. The Japanese, viewing the armada from the crest of Mt. Tenjo, counted 274 vessels.

By the afternoon of 20 July, every ship that would be connected with the amphibious assault was either at or approaching its designated position off Guam. Prospects for success on W-Day appeared to be good, except for a flurry of concern lest an impending typhoon move near the area—and that worry was dismissed by Admiral Conolly’s hurricane specialist. The weather prediction for W-Day was optimistic: a friendly sky, a light wind, a calm sea.

Admiral Conolly confirmed H-Hour as 0830. In a dispatch to the task force, he felt able to say, that because of the excellent weather, the long preparatory bombardment, and the efficient beach clearance, “conditions are most favorable for a successful landing.”60 Events of the next day would show whether he was right.