Chapter 4: Southern Philippines Operations1

The beginning of March 1945 saw American forces firmly entrenched in the Philippines. On Leyte, military operations were all but completed and the objectives of the Leyte campaign, the establishment of a solid base for the reconquest of the Philippines, had been achieved. Japanese emphasis on the defense of Leyte had adversely affected the enemy capability of making a decisive stand on Luzon, the strategic nerve center of the Philippines. Unable to stem the American advance, the Fourteenth Area Army on Luzon resorted to the operational stratagem of “confining the American forces to Luzon despite inferior strength... and holing up in the mountainous districts of Luzon.”2 Aside from tying down sizable American forces in what was at best a prolonged delaying action, the enemy was unable to seriously upset the American timetable. In four months of operations, the U.S. Sixth and Eighth Armies had also seized Samar and Mindoro, as well as some of the smaller islands in the Visayan and Samar Seas.

Barely a month after the campaign on Luzon had begun, General MacArthur decided that the time had come to move into the southern Philippines. The general deemed the recapture of Palawan, Mindanao, and other islands in the Sulu Archipelago essential for two reasons. First, bypassing the southern Philippines would leave their inhabitants at the mercy of Japanese garrisons for an undetermined period of time, a situation clearly inconsistent with United States interests in the area. Secondly, theater strategy required early seizure of the islands for ultimate use as air and naval bases, as well as for serving as a steppingstone in the projected conquest of Borneo and other Japanese-held islands in the Dutch East Indies, the area presently part of Indonesia.

The plans developed for the recapture of the Southern Philippines were known as the VICTOR operations. They were numbered I through V and called for the following schedule:

| VICTOR I (Panay) | 18 Mar 45 |

| VICTOR II (Cebu, Negros, Bohol) | 25 Mar 45 |

| VICTOR III (Palawan) | 28 Feb 45 |

| VICTOR IV (Zamboanga and Sulu Archipelago) | 10 Mar 45 |

| VICTOR V (Mindanao) | 17 Apr 45 |

On 6 February 1945, General MacArthur ordered Eighth Army to prepare operations against Palawan, Mindanao, and other islands in the Sulu Archipelago. Lieutenant General Robert L. Eichelberger, the army commander, had available for the southern Philippine operations Headquarters, X Corps, five infantry divisions, and a regimental combat team of parachutists. On 17 February, Eighth Army issued a plan of operations for the reoccupation of the southern Philippines.3 The first of the operations was VICTOR III. Landings by the 41st Infantry Division were to be carried out on 28 February at Palawan and on 10 March at Zamboanga, the western extremity of Mindanao. The Thirteenth Air Force was to provide air support for the two operations in addition to its mission of supporting Eighth Army on those Philippine islands that were located south of Luzon.

Far East Air Forces planned to have Marine aviation units participate in the liberation of the southern Philippines. To this end, MAG-12 and -14, stationed on Leyte and Samar respectively, were to reinforce the Thirteenth Air Force; the Marine dive bomber units of MAGs- 24 and -32, which had performed so well on Luzon, were to be shifted south to Mindanao as soon as they had completed their mission of supporting the Sixth Army. MAGs-12, -14, and -32 the landings on Zamboanga and in the subsequent ground operations.

The 41st Infantry Division had the task of seizing the town of Zamboanga in an amphibious assault. Due to its peculiar location in relation to the remainder of Mindanao, Zamboanga province was virtually separated from the island except for a narrow isthmus. There, inaccessible mountains and dense jungle formed a major terrain obstacle. During the conquest of Mindanao, Eighth Army expected to rely on the assistance of a sizable guerrilla force. Organized in 1942 and supplied and trained by the Americans since then, this native force could be of immediate assistance to the invasion troops. The guerrillas, under the command of Colonel Wendell W. Fertig, numbered over 33,000 by February of 1945; 16,000 of them were armed.

Similar guerrilla organizations of varying size existed on the islands of Negros, Cebu, and Panay. Bohol, Palawan, and other islands in the Sulu Archipelago harbored small guerrilla units that were relatively ineffective. Prior to the assault on the southern Philippine islands, the primary mission of the insurgents was to furnish intelligence; once the invasion of an island was imminent, the guerrillas were to cut enemy lines of communications, clear beachheads, and box in the Japanese to the best of their capabilities.

The Japanese garrison on eastern Mindanao consisted of the 30th and 100th Infantry Divisions; the 54th Independent Mixed Brigade, consisting of three infantry battalions as a nucleus, with attached naval units, was deployed on

Curtiss “Helldivers” armed with rockets and bombs, replace SBDs of VMSB-244. (USMC A700606)

Filipino guerrillas at Malaban Airstrip, Mindanao. (USMC 117638)

Zamboanga Peninsula. The 55th lndpendent Mixed Brigade, composed of two infantry battalions, occupied Jolo Island in the Sulu Archipelago. The 102nd Division was spread over Panay, Negros, Cebu, and Bohol; half of the division had been previously sent to Leyte. The Japanese in the southern Philippines were under the command of the Thirty-Fifth Army headed by Lieutenant General Sosaku Suzuki. The latter’s attempts to evacuate most of his forces from Leyte to the southern islands was frustrated by the vigilance of American aircraft and torpedo boats; in all, only about 1,750 of the 20,000 Japanese on Leyte eventually made it across to Cebu Island during the early months of 1945. The Japanese commander was able to make good his escape to Cebu in mid-March, only to perish at sea a month later while en route to Mindanao, when the vessel on which he was embarked was sunk off Negros by American aircraft.

There were more than 102,000 Japanese in the southern Philippines, including 53,000 Army troops, nearly 20,000 members of the Army air forces, 15,000 naval personnel, and 14,800 noncombatant civilians. Despite this imposing figure, there were only about 30,000 combat troops. Moreover, the enemy garrisons were spread over numerous islands. Even though they were aware of the existence of guerrilla units, the Japanese felt that they were firmly in control of the situation. There was a sense of optimism—quite unfounded as it turned out—that the Americans might bypass the southern Philippines as they left Japanese garrisons unmolested on other islands in the Pacific. The sentiment among the Japanese was one of general unconcern; even if the Americans decided to venture into the southern Philippines, they would probably be content to seize only the principal ports. The overall attitude of the Japanese garrisons in the southern Philippine islands was perhaps best summed up by a U.S. Army historian, who described the situation as follows:–

The Japanese in the Southern Philippines, therefore, apparently felt quite secure if not downright complacent. Such an outlook would be dangerous enough if shared by first-class troops; it was doubly so when held by the types of units comprising the bulk of the forces in the southern islands. ... Most of the Japanese units in the Southern Philippines had enough military supplies to start a good fight, but far from enough to continue organized combat for any great length of time. ... As was the case in Luzon, the Japanese in the Southern Philippines, given their determination not to surrender, faced only one end—death by combat, starvation, or disease.4

What could happen when Japanese complacency was shattered was clearly illustrated on Palawan Island in mid-December 1944. Up to the autumn of 1944, the Japanese garrison numbering somewhat more than 1,000 men, had led a relatively peaceful existence, except for an occasional ambush by Filipino insurgents. Since the summer of 1942, about 300 American prisoners of war had worked on the construction of an airfield on Palawan. This field was eventually destroyed by American air attacks before it ever became of any major use to the enemy. As the pace of the campaign quickened and an invasion

of Palawan appeared imminent in mid-December, the Japanese garrison panicked and carried out a brutal massacre of the unarmed American prisoners of war. Many of them, huddled in trenches or shelters, were soaked with gasoline and burned to death, while others were bayoneted or shot in the stomach. A few of the Americans were able to escape their tormentors and eventually found their way back to American-held islands, where word of the atrocity was spread. But for most of the prisoners of war on Palawan, the eventual liberation of the island two months after the massacre came too late.5

Zamboanga6

Marine aviation did not play any part in the conquest of Palawan, though the Thirteenth Air Force carried out extensive bombing and strafing operations during the two days preceding the landing. Results of these air attacks were limited by the absence of enemy installations and defenses. The landing itself was unopposed and the two airstrips on the island were seized within hours after the first troops had gone ashore. The Japanese garrison withdrew to the hill country in the interior and from there offered sporadic opposition, which continued well into the summer. Even though work on airstrips near Iwahig and Puerta Princess began at once, neither strip was ready for use by fighter and transport planes until 18 March. By that time, it was too late to provide air support for the invasion of Zamboanga, for that operation had already been launched on the 10th. Participation of Marine aviation units in the VICTOR operations had already been decided upon in the course of February. Under the overall direction of the Thirteenth Air Force, MAGs-12, -14, -24, and -32 were slated to move south to Mindanao. The initial mission of MAGs-12, -14, and -32 was to provide direct air support to the 41st Infantry Division during the invasion of Zamboanga. General Kenney authorized the 1st MAW to reinforce the four Marine air groups with additional wing units from the northern Solomons.

The imminent liberation of the southern Philippines necessitated the employment of even more Marine aircraft. From his headquarters at Bougainvillea in the Solomons, General Mitchell, commander of 1st MAW and Commander Aircraft, Northern Solomons, controlled all aircraft in the area, except for a few Australian tactical reconnaissance planes. Since by late February of 1945, only few Marine squadrons were still operating in the Solomons, it was planned that responsibility for air operations in the Solomons-Bismarck Archipelago would in time be transferred to the Royal New Zealand Air Task Force.

In preparation for the invasion of Zamboanga, Marine air units from bases scattered between the northern

Solomons and the Philippines began to stage. Control of the staging was complicated by the fact that a number of aviation units had been broken up. As a result, by late February, the headquarters and service squadrons of MAG-12 still had not caught up with the air group, nor had the ground echelons of VMF-115, -211, -218, and 313 joined their flight echelons, which were engaged in combat operations on Leyte. The situation of MAG-14 was similar, with ground echelons of VMF-212, -222, -223, and -251 still en route to the Philippines in late February, even though the flight echelons of these squadrons had been operating from Samar since early January. MAG-61, commanded by Colonel Perry K. Smith, was still stationed on Emirau Island, north of the Solomons, where it was both undergoing final training in medium altitude bombing and employed for tactical operations against the Japanese on New Britain, New Ireland, and Bougainvillea. Like other Marine air groups, MAG-61 suffered from over-dispersal. The headquarters and service squadrons, as well as VMB-413, -433, -443, and the flight echelon of VMB- 611 were stationed on Emirau; VMB- 423 occupied Green Island; the ground echelon of VMB-611 had departed Hawaii in late September 1944 and since then had remained aboard ship off Leyte, Samar, and Lingayen before finally going ashore on Mindoro on 25 February.

Additional Marine air units sent to assist in operations in the southern Philippines were Air Warning Squadrons 3 and 4 (AWS-3 and -4). The latter arrived off Leyte on 4 March from Los Negros in the Admiralty Islands, while the former, coming from Bougainvillea, reached Mindoro on the 20th. As the date for the invasion of the Zamboanga Peninsula drew closer, a personnel change occurred when on 25 February, Colonel Verne J. McCaul relieved Colonel William A. Willis as commanding officer of MAG-12. General Mitchell charged Colonel Jerome of MAG-32 with overall command of Marine air units of MAGs-12, -24, and -32 scheduled to move to Zamboanga for participation in operations against Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago. From the island of Samar, MAG-14 was to support operations on Panay, Cebu, and Mindanao.

Before the assault against Zamboanga could be launched, steps had to be taken to assure that the primary objectives of the operation were met. The prime purpose of the seizure of the peninsula was to gain control of Basilan Strait which constitutes one of the two main approaches to Asia from the southwest Pacific. The peninsula featured good landing beaches and airfields protected by inaccessible mountains. The airstrips were located along the southeast coast near Zamboanga Town. Possession of Zamboanga would enable the Americans to establish additional air and naval bases for continued operations in the southern Philippines, particularly against eastern Mindanao. On Zamboanga, as on other enemy-occupied islands in the Philippines, Filipino insurgents had gradually taken over small areas; on Mindanao, Negros, and Cebu half a dozen airstrips were in Filipino hands. When necessary, these airstrips were used by Army transport

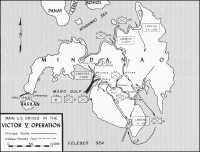

Map 21: Main U.S. Drives in the VICTOR V Operation

aircraft, escorted by Marine Corsairs, to furnish the natives with supplies. About 150 miles to the northeast of Zamboanga Town, near the northern tip of the peninsula, the guerrillas were in possession of an airstrip near the town of Dipolog. (See Map 21). This airfield had been used since 1943 by Allied aircraft to supply guerrilla forces on the Zamboanga Peninsula.

As preinvasion plans for the assault against western Mindanao neared completion, Far East Air Forces reported on 2 March that the airfield on Palawan Island would not be completed in time for VICTOR IV, and it was decided to move one fighter squadron to Dipolog. Before the arrival of the fighters, however, it became necessary to provide adequate protection for the airfield. In a rapid change of original plans, and in order to forestall any Japanese attempt to seize the airfield from the guerrillas, two companies of the 24th Infantry Division, reinforced with two heavy machine gun platoons and one 81-mm mortar section, were airlifted to Dipolog on 8 March, two days before the actual invasion date. The mission of this force was to defend the airfield, though they were not to take offensive action unless it became necessary to do so in maintaining uninterrupted air support.

This Army force, however, was not the first American contingent to arrive at Dipolog, for as early as 2 March MAG-12 ordered an advance echelon consisting of two officers and six enlisted men to move to the airstrip to prepare it as a staging base for guerrilla support missions in northwestern Mindanao. This move was completed on the following day. On 7 March, two Corsairs arrived at Dipolog in order to support the guerrillas. By 9 March, a total of sixteen Corsairs were stationed at the field, all of them engaged in support of guerrillas or in flying missions in support of the imminent invasion. As far as was known to Eighth Army, “this was the first time that aircraft have operated from airdromes before securing them by an assault landing. The use of guerrilla-held airstrips proved to be a marked advantage in this operation.”7

There were bizarre overtones to the activities of Marine aviators operating from an enemy-held island, as outlined in the following account:–

Two planes from Dipolog reconnoitered the road from Dipolog to Sindangan. On the road about a mile north of Siari they sighted about 200 troops dressed as natives but all were carrying arms. The troops at the head of the column were carrying a large American flag. The planes buzzed the troops and the troops waved back. They also sighted four bancas (dugout canoes) about thirty to forty feet long just off Lanboyan Point. Upon returning to Dipolog and reporting their sightings, guerrilla headquarters informed them that the troops sighted were Japs, not guerrillas, and that the bancas were also Jap controlled.8

In a quick response to this information, the two Marine aviators took off again, and headed back to the scene of the earlier sightings. Five dugout canoes, under sail and occupied, were the first to be strafed. The planes then went after the troops and caught up with the column, which was plodding

along the road, still carrying the American flag. When the aircraft began to circle for a strafing run, the troops dropped the flag and headed for the bushes. The two pilots strafed the troops on the road, five pack carabaos, as well as bushes on either side of the road, using about 4,000 rounds of ammunition in the process. The foliage prevented any observation of results.

While Marine aircraft were operating with impunity from Dipolog under the very noses of the Japanese, an amphibious force under the command of Rear Admiral Forrest B. Royal, Commander of Naval Task Group 78.1, was en route to Mindanao. The invasion convoy carried the 41st Infantry Division, commanded by Major General Jens A. Doe, charged with making the assault landing. The prime mission of the naval task group was to transport the division from its staging areas on Mindoro and Leyte to the Zamboanga Peninsula and keeping it supplied after the landings. A secondary mission was the protection of the assault force against hostile naval action, although intelligence indicated that only motor torpedo boats and submarines would be encountered.

Included in the assault force were staffs and ground echelons of MAG-12 and -32, as well as AWS-4. The ground echelon of MAG-32, loaded in six LSTs, had left Luzon on 23 February and proceeded to Mindoro for staging. Ground crewmen of MAG-12 had boarded LSTs at Leyte and headed to Mindoro for staging. AWS-4 staged directly from Leyte Gulf on 8 March and joined the invasion convoy as it headed for western Mindanao. Among the Marines headed for Zamboanga were the forward echelons of MAGs-12 and -32 consisting of operations, intelligence, and communications personnel under the command of Colonel Jerome.

The Thirteenth Air Force had commenced the preinvasion bombardment of the Zamboanga Peninsula as early as 1 March. From 4-8 March, the Army Air Forces concentrated on the destruction of enemy aircraft, personnel, and supplies in areas adjacent to Japanese airfields in Borneo, Davao, and Zamboanga. Planes from MAG-12, based at Dipolog, and Army aircraft provided air cover for the assault force as the ships approached the Zamboanga Peninsula. No opposition was encountered in the air.

Early on 10 March, a task force consisting of two light cruisers and six destroyers moved into Basilan Strait just off the southern tip of the Zamboanga Peninsula. This force began an intense bombardment of the beachhead area, which included a stretch of the coastline from Caldera Point to Zamboanga City and inland for a distance of 2,500 yards. As incessant air strikes hit the landing beaches and adjacent area to the north, the first infantrymen went ashore. The beaches, though heavily fortified, were not defended in strength and only moderately heavy machine gun fire greeted the assault units. Japanese defensive positions, although superior in layout and construction to any previously encountered in the Philippines, were in many instances unmanned.

By midmorning, the advancing infantrymen seized the first airstrip near Zamboanga Town. At noon, the 163rd

Infantry Regiment, supported by a tank company, stood poised to assault the town itself. Except for a number of mines and booby traps that remained to be cleared, Zamboanga Town was firmly in American hands by late afternoon. The initial objective of the Marine aviation personnel taking part in the landings was San Roque airfield, situated northwest of Zamboanga Town and only a mile inland from the invasion beaches. Heavy resistance encountered by the men of the 41st Infantry Division near the village of San Roque delayed capture of the airfield until 12 March, though Colonel Jerome and his staff were able to reconnoiter the strip on the day of the first landings. Personnel from MAGs-12 and -32 began unloading shortly before noon of J-Day, even though by this time the Japanese were shelling the beaches with artillery and mortars.

The 41st Infantry Division did not succeed in driving the Japanese entirely from the San Roque airstrip area until the afternoon of 13 March. At this time, the 973rd Aviation Engineer Battalion moved in on the heels of the advancing infantry and work began around the clock to ready the field for operations. Upon arrival at San Roque airfield, the Marines promptly redesignated it as Moret Field in commemoration of a Marine aviator, Lieutenant Colonel Paul Moret, formerly commanding VMTB-131, who had been killed when a transport on which he was a passenger crashed on New Caledonia in 1943.

While work on Moret Field was in progress, aircraft from Dipolog flew patrol missions over the beach area and executed air strikes in support of the infantry. As the soldiers advanced into the foothills to the north of Moret Field, Japanese resistance stiffened; elaborate booby traps also took their toll among the Americans. On 13 March the 163rd Infantry Regiment suffered 83 casualties when the Japanese blew up a hill north of Santa Maria to the north of Zamboanga Town.9 Apparently the enemy had decided to explode a hidden bomb and torpedo dump and detonated it electrically when American troops had advanced up the hill in strength.

Japanese demolition experts also succeeded in throwing a scare into the Eighth Army commander following his inspection trip to Zamboanga. Just as General Eichelberger was preparing to return to the USS Rocky Mount and was passing through Zamboanga Harbor on a barge, the Japanese decided to give him a farewell salute. As the general himself described the incident:–

Apparently enemy field glasses still accurately observed the harbor. Anyway, a detonator somewhere let loose a naval mine which sent a cascade of water ten stories high. It just missed my boat; after swallowing hard, I found myself intact and went aboard the cruiser. A Navy flying boat picked me up shortly after and took me back to Leyte in very stormy weather.10

During the time that Moret Field was being readied for operations, the Japanese remained passive in the air. The only exception occurred on 13 March, when a single enemy aircraft made two strafing runs over the field and dropped a bomb with negligible effect. Moret Field became operational on 15 March

with the arrival of eight Corsairs of VMF-115. By the 18th, the flight echelons of VMF-211, -218, and -313 had reached Zamboanga. The Army Air Forces 419th Night Fighter Squadron, equipped with P-61s, was also based at Moret Field.

As early as 12 March, Thirteenth Air Force had designated Colonel Jerome as Commander Air Groups, Zamboanga, Mindanao, hereafter referred to as Marine Aircraft Groups, Zamboanga (MAGsZam). Initially, Colonel Jerome’s command included MAGs-12 and -32, though a month later MAG-24 joined the two air groups on Mindanao. One member of MAG-24, Lieutenant Colonel McCutcheon, had accompanied Colonel Jerome to Moret Field for the express purpose of establishing an organization similar to the one previously used at MAGsDagupan on Luzon.

As the infantry continued the advance into the interior of the Zamboanga Peninsula, enemy harassment of Moret Field decreased until it stopped altogether. The Corsairs of MAG-12 began to lend close air support on 17 March, when Captain Samuel H. McAloney, intelligence officer of MAG- 32, was designated as commander of the support air party with the 163rd Infantry Regiment. The primary mission of MAGsZam was close support of ground troops, though Marine Corsairs also maintained continuous convoy over friendly shipping in the Sulu Sea.

Marine organization for close air support at MAGsZam was simpler than it had been on Luzon, since Marine aviation had sole responsibility for the operation of Moret Field. In addition, the regiments of the 41st Infantry Division requested air support directly from MAGsZam. The support air parties with the infantry consisted of a captain, one or more first lieutenants, two or more radio operators, and two or more radio technicians. Air-ground communication was carried on with two types of mobile radio gear. A large van with high frequency (HF) equipment with an effective range of more than 100 miles was used; where only distances of less than 15 miles had to be covered, more compact equipment was employed. The use of the van or jeep depended on the distance of the air support parties from MAGsZam, though there were many occasions when the two vehicles, working as a team, were employed. The radio jeep, in view of the limited range of its radio equipment, maintained contact with the communications van; the latter, in turn, acted as a relay with MAGsZam.

On the level below the air support party was the air liaison party consisting of a Marine aviator, a radio operator, and a technician. The liaison party was equipped with a radio jeep, maps and aerial photographs of the area in which it was to operate, as well as a field telephone which could be used in conjunction with the radio. Air-ground liaison was helped by the presence of AWS-4 at Moret Field. The latter unit, redesignated the 76th Fighter Control Center, had ample communications facilities. Beyond its mission of watching for approaching enemy aircraft and assisting friendly aircraft in getting back to the field, personnel of the air warning squadron employed their radio

LSTs land Marine aviation personnel and supplies on Zamboanga. (USMC 1116824)

U.S. Army 41st Infantry Division honors Marine aviation for air support received in the Southern Philippines. (USMC 116887)

and radar equipment in supplementing the existing ground-air communications setup.

Marine aviators on the Zamboanga Peninsula flew their first air support missions at very close range, since the objectives invariably were located just a few miles from the runways of Moret Field. In a situation similar to that on Peleliu, Marine aviation personnel could watch the entire action from the runway. It was not unusual for a member of the air liaison party to scan the frontline before a mission, accompanied by the flight leader. The two Marines would then discuss the situation with the commander of the Army battalion involved, and the flight leader thus could receive a direct briefing as to the type of air support desired by the ground troops.

As the Japanese were driven back into the hills of Zamboanga, and Moret Field was further extended, additional aviation units began to arrive. The mission of the Marine dive bomber squadrons on Luzon came to a close on 23 March and VMSB-142 and -236 reached Moret Field on the following day. Despite an otherwise uneventful flight of the SBDs from Luzon to Zamboanga, this flight was to culminate in the death of two Marine aviators:–

Fate decided this by the toss of a coin. Squadron procedure had two pilots assigned to one plane. Prior to departing from Luzon, it was decided to toss a coin to see who would fly to Zamboanga. Lt. Charles C. Rue and Lt. Charles F. Flock tossed, and Rue won the toss. On the flight down from Mangaldan, Rue broke an oil line and made a crash landing, on the supposedly guerrilla held air strip on Panay. Planes in the flight observed Rue and his gunner get out of their plane and wave to a group of men who came out of the jungle at the edge of the strip. About six weeks later, when the Army invaded Panay, it was learned through interrogation of prisoners, that Rue and his gunner had been beheaded the day after they were taken prisoner.11

Between 18 and 24 March, MAGsZam aircraft carried out their primary mission of supporting the 41st Infantry Division advance, Among the first air strikes was an attack by eight aircraft against the enemy dug in at Capisan, 3,500 yards north of Zamboanga Town. The planes dropped instantaneously fused 1,000 pound bombs on the assigned area, but results of the attack were unobserved. While strafing the entire area, the Marines drew light but accurate machine gun fire which damaged two of their aircraft. In a second strike on the same day, eight aircraft, each carrying a 175-gallon napalm fire bomb, attacked a ridge north of Zamboanga Town, where the enemy was dug in. Six napalm bombs covered the area; two failed to release; one of these was jettisoned over the water and the other was returned to base. After the strike, ground observers reported that the area of the target was well burned out and appeared lifeless and deserted.

As the Japanese were driven back into the inhospitable interior of Zamboanga, Marine aviators continued to carry out similar missions. In an innovation of close air support techniques, a support air party officer on 21 March relayed target information from an L-4 spotter plane to the air liaison party in a radio jeep on the ground; the latter,

in turn, coached the planes to the target. Positions indistinguishable from a fast moving Corsair thus could be easily pinpointed. The observer in the Cub plane remained over the target after the strike and reported excellent results. This was later verified by the commanding officer of the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry Regiment, who reported that the enemy had withdrawn from the bombed area, blowing up two ammunition dumps and firing one warehouse on their way.

On 22 March, 16 Corsairs executed a concentrated attack on Japanese troops dug in on top of an L-shaped ridge 500 yards northwest of Masilay. The infantry had failed in the attempt to take the ridge on the preceding day. The planes dropped 13 quarter-ton bombs over the target without being able to observe the results of the bombing. However, when 2/162 resumed its advance, the infantrymen did not encounter any enemy opposition on the ridge. The battalion commander subsequently reported that an enemy pillbox had received a direct bomb hit and 63 Japanese dead had been counted by nightfall.

The remainder of March saw the continued advance of 41st Infantry Division troops into the interior of Zamboanga. As early as 26 March, MAG-32, in discussing the development of Moret Field, was able to make the following note:–

This lower end of Zamboanga Peninsula has taken on a bustling, businesslike air, and with the air strip in full operation, camps being built, engineering sheds being rushed to completion, mess halls going up, all Marine units are functioning at top speed to establish all the elements of a fully equipped advance Marine Air Base.12

Except for the presence of an Army Air Forces night fighter squadron and a few Navy PBYs used for rescue work, Moret Field continued to remain under Marine control. Eventually, the field was to house a total of 299 aircraft: 96 F4Us, 151 SBDs, 18 PBJs, 18 SB2Cs, 2 F6Fs, 1 FM, 2TBFs, 5 R4Ds, and 6 Army P-61 “Black Widow” night fighters.13

Operations at Moret Field soon were going into high gear and MAGsZam aircraft extended their operations to adjacent islands in the Sulu Archipelago. Between 8 and 22 March, the guerrilla-held strip at Dipolog was occupied by a group of Marine ground personnel and an Army security detail. The grass strip even boasted a temporary fighter control center. Aircraft from MAGsZam became frequent visitors to Dipolog, flying in one day with supplies for the guerrillas, staying overnight, and returning to Moret Field on the following day.

On 27 March word was received at Moret Field that a force of about 150

Japanese, armed with two grenade launchers, one light machine gun, two automatic rifles, and more than a hundred rifles was headed towards Dipolog and had advanced to within about 11 miles of the field.14 The guerrilla force of 400, commanded by Army Major Donald H. Wills, was armed but had never been in action before. Because of the potentially menacing situation, all American personnel were ordered to evacuate Dipolog on 27 March and left the field in the course of the day.

MAGsZam dispatched four aircraft to Dipolog to investigate conditions there. Though somewhat at variance in minor details with the official record, the comments of the division leader are of interest:

We sent a division of Corsairs to Dipolog in response to a request for air support. The tone of the message received at Zamboanga was that Dipolog was in imminent danger of falling, which we learned was not the case when we got there. The 500 to 600 Filipino guerrillas who opposed the Jap force were evidently keenly interested in avoiding a fight with the Japs. Major Wills evidently figured an air strike might boost their morale and damage the enemy at the same time.

The lack of maps or photos of any kind, as well as no way to mark targets and no communication with the troops all combined to dictate the method we used. Sharpe [1st Lieutenant Winfield S. Sharpe], as the smallest man in the division, was elected to sit on Major Wills’ lap.15

Shortly thereafter, the aircraft took off. Sitting on the Army major’s lap, Lieutenant Sharpe led the four Corsairs in six strafing runs over the enemy positions while Major Wills pointed out the targets. The Japanese received a thorough strafing and were forced to pull back several miles. Having expended their ammunition, the Corsairs returned to Dipolog where Captain Rolfe H. Blanchard, the division leader, and Lieutenant Sharpe spent the night while the remaining two aircraft returned to Moret Field. Following his return to MAGsZam on 28 March, Captain Blanchard discovered that squeezing two men into the narrow confines of a Corsair cockpit did not meet with the wholehearted approval of his superiors. In the flight leader’s own words:–

I don’t recall what happened to Sharpe for this incident, but I was mildly reprimanded by Lieutenant Colonel Leek of MAG-12, who acted as MAGsZam Group Operations Officer, together with Lieutenant Colonel McCutcheon until the latter’s departure from Moret Field and I learned (reliability of source unknown) that Major Wills was awarded the Silver Star.16

The existence of a Marine aviation group with two operations officers requires an explanation, which since the end of World War II has been furnished by Colonel Leek, who made the following comment:–

The operations organization as it existed had been set up by LtCol Keith B. McCutcheon who, although the operations officer of MAG-24, had accompanied Colonel Jerome from Dagupan for the express purpose of placing into effect a command operations organization similar to the one at Dagupan. Once the organization

was functioning, LtCol Frederick E. Leek who had taken the advance echelon of MAG-12 into Zamboanga relieved LtCol McCutcheon. Although personnel were pooled, responsibilities can never be shared. LtCol Leek as senior of the two group operations officers functioned as MAGSZAM operations officer until he was detached, at which time (17 May 45) he was relieved by LtCol Wallace T. Scott of MAG-32.17

On 29 March, a ceremony was held in front of the operations tower on Moret Field. while the 41st Infantry Division band played, Colonel Jerome, with officers of the Marine air groups at attention behind him, received a plaque from General Doe, commanding the 41st Infantry Division. The plaque itself was spectacular in its own right Six feet high by four feet, it was trimmed with captured Japanese naval signal flags. Mounted on it was a Japanese light machine gun, still showing the scars of battle. Below that was an enemy battle flag of white silk with the red “Rising Sun” of Nippon. Beneath it were listed the islands nearby which the division had invaded with Marine air support. At the top of the plaque were the words: “In Appreciation-41st Infantry Division.”

Even more impressive for the Marines were the words of the Army division commander which accompanied the award. In addition to commending the air groups for the support of ground operations, General Doe had this to say:–

The readiness of the Marine Air Groups to engage in any mission requested of them, their skill and courage as airmen, and their splendid spirit of cooperation in aiding ground troops have given this Division the most effective air support yet received in any of its operations.18

On 30 March, the already formidable Marine establishment at MAGsZam was further strengthened by the arrival of the flight echelon of VMSB-611 under the command of Lieutenant Colonel George H. Sarles. Prior to its arrival at Moret Field, the squadron had been stationed on Emirau Island in the St. Matthias Group. VMSB-611 was equipped with 16 Mitchell medium bombers (PBJs). Each of these aircraft was capable of carrying eight rockets, a bombload of 3,000 pounds, and anywhere between eight and fourteen .50 caliber machine guns. The bombers further contained airborne radar, an instrument panel for the pilot and copilot, as well as long-range radio and complete navigation equipment. The profusion of electronic gear made the PBJs particularly adaptable to operating at night and under conditions of poor visibility.

The versatility that Lieutenant Colonel Sarles expected from his pilots and planes became evident during intensive training on Emirau. His copilot, who remained with the squadron commander in preference to having a crew of his own, made this following comment about his commanding officer:–

He wanted us to be able to play the role of fighters where fighters were needed, of bombers, of photographers, skip bombers,

and indeed it seemed on some occasions that he thought we were capable of dive bombing. During the Philippine campaign we strafed, bombed, skip bombed, fired rockets, photographed, flew observers, were sent on antisub patrols, were sent up at night as night fighters, and bombed at medium altitudes. In fact, one member of VMB-611 shot down with his fixed guns, and using his bombsight as a gun-sight, a Japanese twin-engine light bomber, a “Lily.”19

Shortly after their arrival at Moret Field, the PBJs began to fly long-range reconnaissance patrols over Borneo and Mindanao. They searched the seas for enemy submarines and photographed future landing sites in the Sulu Archipelago. Pilots of VMB-611 struck at enemy truck convoys and airfields at night and harassed the Japanese with nuisance flights. Use of the Mitchells made it possible for MAGsZam to conduct operations against the enemy around the clock.

Progress of the 41st Infantry Division advance across the Zamboanga Peninsula was a costly and time-consuming process. Operations on the peninsula continued until the latter part of June, which saw the end of coordinated enemy resistance, though infantrymen and guerrillas continued to ferret enemy stragglers out of the inaccessible hills and jungles long after that date. At the same time that Japanese resistance on Zamboanga was gradually reduced, a number of operations, many of them supported by Marine aviation, were executed in the southern Philippines. For many of the enemy, the illusion that the islands which they garrisoned might be bypassed by the Americans, was effectively destroyed.

Southern Visayas and Sulu Archipelago20

The invasion of the Zamboanga Peninsula on 10 March 1945 represented only the first step in an entire series of amphibious landings designed to drive the Japanese out of the southern Philippines. Six days after the 41st Infantry Division set foot on Zamboanga, a company of the 162nd Infantry of that division crossed Basilan Strait and went ashore on Basilan Island, 12 miles south of Zamboanga Town. Other islands in the vicinity were quickly captured against negligible enemy resistance.

Capture of Basilan Island marked the arrival of the first American troops in the Sulu Archipelago, a chain of islands extending southwestward from Mindanao toward Borneo. Even while the drive against the Sulu Archipelago got under way, two other divisions of the Eighth Army were assaulting additional islands in the central Philippines, particularly those islands surrounding the Visayan Sea. The assault on these islands—Panay, Negros, Cebu,

and Bohol—began with the invasion of Panay on 18 March when the 40th Infantry Division landed on the latter island unopposed. Following a brief destroyer bombardment the first assault wave hit the beach—to be greeted on shore “by men of Colonel Peralta’s guerrilla forces, dressed in starched khaki and resplendent ornaments.”21

The landing on Panay marked the beginning of the VICTOR I operations. Air support for the landings was provided by planes from three Marine fighter squadrons of MAG-14 based on Samar. Twenty-one Corsairs of VMF-222 patrolled over the beachhead during the day of the landings, though the enemy remained just as passive in the air as on the ground. The squadron’s only attack mission for 18 March was the strafing of six barges in the Iloilo River.

Pilots from VMF-251 searched the waters adjacent to the Panay beachheads for enemy shipping, but failed to find any trace of enemy activity. VMF-223 had the mission of neutralizing any Japanese air effort on adjacent Negros Island while the landings were in progress. The Corsairs swept down on six enemy airstrips on Negros during the day and destroyed two Japanese fighters. No lucrative targets ever materialized for the eager Marine aviators on Panay; the enemy kept to the woods and offered only weak resistance to the advancing infantry. The occupation of Panay largely resembled a major mop-up operation; just as most of the American forces on Panay had refused to surrender to the Japanese in 1942, so now the Japanese commander, Lieutenant Colonel Ryoichi Totsuka, marched the 1,500 troops under his command into the hills, where they remained until the end of the war. By the end of June, U.S. Army casualties on Panay were about 20 men killed and 50 wounded.

On 26 March, VICTOR II got under way when the America] Division landed on Cebu Island, about five miles southwest of Cebu City. Preceded by a devastating naval bombardment, leading waves of LVTs rolled onto the beach, where a nasty surprise awaited them. The first wave was abruptly halted when ten of the 15 landing vehicles were disabled by land mines. Several men were killed and others were severely injured as they stepped on mines while dismounting.

It was soon discovered that the existing beach defense was the most elaborate and effective yet encountered in the Philippines, even though the covering fire from prepared defenses was limited to small arms and mortar fire. The entire length of the landing beach bristled with mines ranging in size from 60-mm mortar shells to 250-pound aerial bombs.

Subsequent waves of infantry unloaded on the beach, but made no attempt to move forward into the mined area. All along the shore, between the minefield and the water’s edge, men were crowded shoulder to shoulder, two and three deep. As they moved up and down the beach, unsuccessfully trying to find a clear opening, it became apparent that organization was breaking down and adequate control was lacking.22

Eventually, the confusion on the beachhead subsided, and despite the

lack of an adequate number of engineers, the troops pushed through after lanes were finally cleared. Behind the minefield, 50 yards inland in the palm groves, the assault force encountered continuous barriers; antitank ditches, log fences and walls, timber sawhorses, and steel rail obstacles all designed to block the advance of tracked or wheeled vehicles. Together with the minefield, these obstacles were covered by well-prepared firing positions which included concrete pillboxes having walls from seven inches to three feet thick, emplacements walled with one to four coconut logs, barbed wire, and a network of trenches.

Strangely enough, the presence of such formidable defenses did not induce the Japanese to vary their recently instituted strategy of withdrawing from the beach area and resisting the American invasion troops with a force only strong enough to be of nuisance value. The enemy reaction to the American assault on Cebu proved no exception to his earlier practice. Even the few Japanese who were left to man the prepared positions had been forced to abandon them by the intensive and concentrated bombardment of the beach area by American naval guns. “Had these installations been manned by even a small but determined force, the troops massing behind the mine field would have been annihilated and the eventual victory would have become far more costly.”23 As it was, enemy casualties on or near the invasion beaches the first day were 88 killed and 10 captured; American losses were eight killed and 39 wounded.24

As infantrymen of the Americal Division consolidated their beachhead on Cebu and advanced northward toward Cebu City, the Japanese began a hasty evacuation of the town. Throughout 26 March, Marine aviators of MAG-14 attacked enemy motorized columns and dismounted infantry headed for the hills northwest of Cebu City. Planes from VMF-222, -223, and -251 strafed the enemy with .50 caliber machine guns, destroying about 20 trucks and inflicting an undetermined number of casualties.

Japanese resistance on Cebu followed a familiar course. Unable to stem the American advance and severely harassed by American air, the enemy withdrew into the hills, from where he offered prolonged resistance. By late June numerous Japanese were still able to hide out in the hills, living a hunted existence, but ineffective as fighting groups.

Meanwhile, the American drive through the southern Philippines continued. Two days after the invasion of Cebu, troops of the 40th Infantry Division invaded Negros Island in a shore-to-shore operation from Panay. As on Cebu, the enemy withdrew into the hills, harassed by Marine aircraft and Filipino guerrillas. By mid-June, the Japanese on Negros no longer constituted an organized fighting force. A number of stragglers remained to lead a Precarious existence, in which a struggle for survival in the hills was paramount.

The isolation in which the remaining enemy troops in the southern Visayas found themselves is best illustrated by their ignorance of the end of the war. American leaflets dropped over enemy-held areas on Cebu by order of Major General William H. Arnold, commanding the Americal Division, informed the Japanese holdouts that the war was over and promised them fair treatment in accordance with the rules of the Hague and Geneva Conventions. On 17 August the Japanese replied with the following message:

We saw your propaganda of 16th August 1945; do not believe your propaganda. We request that you send to us a Staff Officer of General Yamashita in Luzon if it is true that Imperial Japanese surrendered to the Americans.25

A further exchange of communications proved fruitless. The Japanese radio equipment on Cebu was out of order, and the holdouts had no way of getting direct information from Tokyo. Orders were issued to the effect that officers and men would be punished if they believed the American propaganda. The situation was clarified however, on 19 August, when the Japanese were able to repair one of the radio receivers and learned that Japan was in fact defeated. “There was no longer any doubt in their minds; their country was really defeated, so their only course of action was to surrender themselves to the Americans.”26 On Cebu, two lieutenant generals, a major general, and an admiral surrendered, as did the remaining Japanese garrison of 9,000 men. The Americal Division and attached units had killed another 9,300 Japanese on Cebu and about 700 more on nearby Bohol and eastern Negros at a cost of 449 men killed and 1,872 wounded in action.

Throughout the VICTOR I and II operations in the southern Visayas, aircraft of MAG-14 gave all possible support to the ground troops. In addition to guerrillas who directed the Marine pilots to their targets, Army support air parties also were in operation on all of the newly invaded islands. The Thirteenth Air Force on Leyte directed MAG-14 by means of daily assignment schedules to report in for control to various support air parties. The Army Air Forces on many occasions furnished air coordinators in B-24s, which led the flights to the targets and pinpointed objectives. Despite poor weather, planes of MAG-14 flew a total of more than 5,800 hours during the month of April alone, an average of almost nine hours per day per plane.27

By early May, the need for air support in the central Philippines had decreased and MAG-14 was transferred to the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing on Okinawa. The air group ceased combat operations on Samar on 15 May. Once more, Marine aviators had made a material contribution to the liberation of the Philippines. In paying tribute to the accomplishments of these Marine aviators, General Eichelberger expressed himself as follows:–

Marine Air Group Fourteen rendered an outstanding performance in supporting overwater and ground operations against the enemy at Leyte, Samar, Palawan, Panay, Cebu, and Negros, Philippine Islands. This group provided convoy cover, fighter defense, fire bombing, dive bombing and strafing in support of ground troops. The enthusiasm of commanders and pilots, their interest in the ground situation and their eagerness to try any method which might increase the effectiveness of close air support, were responsible in a large measure for keeping casualties at a minimum among ground combat troops.28

Concurrently with operations in the southern Visayas, the drive into the Sulu Archipelago, a continuation of VICTOR IV, also gained momentum. On 2 April, elements of the 41st Infantry Division invaded Sanga Sanga in the Tawi Tawi Group at the extreme southern end of the Sulu Archipelago, 200 miles south of Zamboanga and 30 miles east of the coast of Borneo. The invasion force encountered only light opposition and, later in the day, launched a shore-to-shore assault against adjacent Bongao Island.

Both assault operations were supported by Marine aircraft. On 1 April, both islands had been heavily bombed and napalmed by Corsairs of VMF-115 and -313. The next day, on board the destroyer USS Saufley, Colonel Verne J. McCaul, commanding MAG-12, served as support air commander. The control room of the destroyer contained three air support circuits. One of these controlled the combat air patrol; another circuit was available for air-sea rescue operations; a third was utilized for direction of support missions on the beach. In the course of both landings, as Marine fighters and bombers circled overhead, a radio jeep went ashore with the assault troops. This jeep contained the Marine air-ground liaison team headed by Captain Samuel McAloney as support air controller. As soon as the Marine team reached the beach, Captain McAloney took charge of the direction of the strike planes.

During the Bongao landings, 44 dive bombers from MAG-32 dropped 20 tons of bombs on the island. SBDs of VMSB-236 attacked an enemy observation post and troop concentrations. While the dive bombers were bombing such enemy objectives as they could locate, Corsairs from VMF-115 and -211 flew combat air patrol over Sanga Sanga. The Marine fighters attacked an enemy radio station with unobserved results. The Corsairs provided air cover for the invasion force until 8 April, when targets suitable for aerial bombing or strafing were no longer in evidence.

Even as the occupation of Sanga Sanga and Bongao Islands was progressing, bypassed Jolo Island to the north was drawing a lot of attention from the Marine aviators, who carried out daily raids. As early as 4 April, SBDs of VMSB-236 carried General Doe, commanding the 41st Infantry Division, and a member of his staff to Jolo Island on a reconnaissance mission. Following several reconnaissance flights by the division commander, all officers and senior noncommissioned officers of RCT 163 made similar flights over their landing beaches and zones of advance. This was possible because

of the large Marine aircraft group at Zamboanga and the lack of Japanese air strength.

Jolo, situated 80 miles southwest from Zamboanga, was within easy range of Moret Field. Moro guerrillas had seized the initiative from the Japanese prior to the American landings. As a result the Japanese had been forced to withdraw into the interior, where they established their defenses on five mountains named Bangkal, Patikul, Tumatangas, Date, and Daho.

On 9 April, elements of the 41st Infantry Division landed on Jolo Island in a shore-to-shore operation from Zamboanga. The Marine landing party, consisting of 5 officers and 11 men, was headed by Captain McConaughy. Lieutenant Colonel John Smith was support air commander and Captain McAloney was support air controller. The team was equipped with a radio-equipped truck and two similarly equipped jeeps. During the landing near Jolo Town, the Marine air liaison party was compelled to disembark the radio-equipped jeeps in four feet of water, because the Landing Ship, Medium (LSM), carrying these vehicles could not get close enough to the beach. The unexpected baptism in salt water played havoc with the radio gear, which had to be disassembled, carefully cleansed with fresh and sweet water, dried with carbon tetrachloride from fire extinguishers, and finally reassembled before it could be put back into operation. The radio truck landed somewhat later at a different beach without undue complications.

In the face of light enemy opposition, the 41st Infantry Division pressed onwards into the interior of the island. Two of the Japanese hill strongholds, Mt. Patikul and Mt. Bangkal, were seized within 24 hours after the initial landings. The infantry advance was executed under a constant umbrella of Marine fighters and dive bombers. On the very first day of the Jolo operation, Marine aviators pummeled the enemy with 7,000 pounds of napalm, nearly 15 tons of bombs, and 18,200 rounds of ammunition.29 In one day, Marine aviators knocked out nine enemy gun positions, razed two radio shacks and towers, and knocked out seven enemy-occupied buildings and personnel areas.

The infantry advance into the interior of Jolo Island met its first strong resistance at the approaches to Mt. Date. Nevertheless, this enemy strongpoint fell on 12 April. Mt. Daho, six miles southeast of Jolo Town, loomed as the next major obstacle in the path of the advancing infantry. This formidable strongpoint with an elevation of 2,247 feet was of historical significance, for about four decades earlier Americans had fought the Moros on this mountain. It was estimated that about 400 Special Naval Landing Force troops were entrenched on Mt. Daho, equipped with nine dual 20-mm guns, as well as heavy and light machine guns.

The attack against Mt. Daho began on 16 April, when infantrymen and Filipino guerrillas ran into a veritable hail of fire from the Japanese defenders, who were using connecting trenches, pillboxes, and dugouts to best advantage. The preliminary bombardment of the Japanese strongpoints by aircraft and artillery proved inadequate

and the advance stalled, For the next four days, artillery and Marine aviation took turns in softening up the enemy, who obviously was determined to make his last stand here. On 18 April, 27 SBDs of VMSB-243 and 18 SBDs of VMSB-341 from Moret Field dropped over 21 tons of bombs on the enemy under the direction of the Support Air Party. On the following day, 47 SBDs of VMSB-236 and 18 SBDs of VMSB-243 continued the neutralization of the enemy on Mt. Daho. Of the results achieved, the ground forces reported: “Of 42 bombs dropped this morning, 35 were exactly on the target. Remainder were close enough to be profitable.30

By 20 April it seemed that Mt. Daho was ripe for a direct assault. As the infantrymen edged their way up the hill, they were halted by a hail of fire which killed 3 men and wounded 29.31 Once more, the attack was halted as artillery and supporting aircraft shelled, bombed, and strafed the obstinate holdouts. In the course of 21 April, 70 SBDs dropped more than 15 tons of bombs on enemy positions at Mt. Daho. As night fell, the artillery began to saturate the target area.

Early on 22 April, 33 SBDs from VMSB-142, -243, and -341 and four rocket-firing Mitchell bombers (PBJs) of VMB-611 attacked Japanese positions on Mt. Daho. Again, the infantry jumped off for the attack on the stronghold. This time, the attack carried the hill. Speaking of the final assault, the division historian made the following comment:–

The combined shelling and bombing was so effective that the doughboys were able to move forward at a rapid pace without a single casualty. The area was found littered with bodies of 235 Japs and it was believed that many more had sealed themselves into caves and blown themselves to bits. This broke the Jap stand in this sector and the few enemy troops that escaped from Mt. Daho wandered aimlessly in small groups and were easy prey for roving guerrilla bands.32

Fighting on Jolo Island continued until well into the summer of 1945, but the capture of Mt. Daho had broken the backbone of the enemy defense. Control of Jolo provided the Americans with the best port in the Sulu Archipelago; it also marked the completion of the drive into the archipelago.

Mindanao33

One more operation was required to bring all of the southern Philippines under Allied control. This operation was VICTOR V, the seizure of Mindanao, southernmost and second largest island in the Philippines. This island, measuring 300 miles from north to south and about 250 miles from east to west at its widest point, had a population of nearly two million just before the outbreak of World War II. Even

though the Zamboanga Peninsula technically is part of the Mindanao mainland, “the peninsula, for purposes of military planning, was not considered part of Mindanao at all.”34 Hence, because of the forbidding mountain barrier separating eastern Mindanao from the Zamboanga Peninsula, a separate invasion of the eastern portion of the island had to be instituted despite the presence of American forces on Zamboanga since 10 March 1945.

Prior to the VICTOR V operation, enemy strength on Mindanao, less Zamboanga, was estimated at 34,000. Of this number, 19,000 were combat troops; 11,000 were service troops; an estimated 3,000-5,000 poorly armed Japanese civilians, conscripted residents of Mindanao, made up the rest of the garrison.35

Responsibility for the Mindanao operation was assigned to the X Corps, commanded by Major General Franklin C. Sibert. Capture of the island was to be carried out by the 24th and 31st Infantry Divisions, which were to invade the west coast of Mindanao near Malabang and Parangon 17 April 1945. Task Group 78.2, under the command of Rear Admiral Albert G. Noble, furnished the amphibious lift, convoy escort, and naval gunfire support for the X Corps en route from staging areas on Mindoro, Leyte, and Morotai to Mindanao.

Despite the impressive size of the Japanese garrison on Mindanao, the invasion force could count on assistance from guerrilla forces on the island, which “were the most efficient and best organized in the Philippines.”36 These Filipinos were commanded by Colonel Wendell W. Fertig, a former American engineer and gold miner, who had turned guerrilla after the fall of the Philippines and built up an effective insurgent force. Fertig had maintained radio communications with Mas- Arthur’s headquarters ever since the summer of 1942 and, from 1943 onwards, had been the recipient of supplies brought in first by submarine and later by air or small vessels. The presence of an insurgent force in the enemy rear began to pay dividends even before the first X Corps troops landed on Mindanao. Prior to the invasion force’s move towards the island, Colonel Fertig’s guerrilla force had been attacking the Japanese garrison at Malabang, with the support of Marine aircraft from Moret Field.

By 5 April, following the expulsion of the enemy from Malabang and vicinity by the guerrillas, Marine aircraft started to operate from the Malabang airstrip. “As the front lines were then less than a half mile from the airstrip, Marine pilots visited ground observation posts for briefing, and after studying enemy defenses, flew a mere 800 yards before releasing their bombs on primary hostile targets.”37

Nor were these Marine air strikes in support of the guerrillas all the Japanese had to worry about. For six days prior to the American landings on Mindanao, heavy bombers hit Cagayan, Davao, Cotabato, Parang, and Kabacan, some of the more important towns

on the island. At the same time medium bombers struck Surigao, Malabang, Cotabato, and the Sarangani Bay area. Dive bombers hit pinpointed targets, while fighters carried out several sweeps daily over the roads and trails throughout the island.

The official Army history has described the situation of the Japanese in the immediate area of the contemplated landings as follows:–

By the 11th of April the last Japanese had fled toward Parang and the guerrillas had completed the occupation of the entire Malabang region. On 13 April Colonel Fertig radioed Eighth Army that X Corps could land unopposed at Malabang and Parang and that the Japanese had probably evacuated the Cotabato area as well.38

In addition to the assistance furnished to the guerrillas on Mindanao by aircraft from MAGsZam, the Thirteenth Air Force, reinforced by elements of the Fifth Air Force and the Royal Australian Air Force Command, had carried on a continuous air offensive of neutralizing enemy air, ground, and naval forces, and to prevent Japanese reinforcements and supplies from reaching the objective area. Fifth Air Force, commanded by Major General Ennis C. Whitehead, had the specific mission of providing aerial reconnaissance, photography, and providing air cover for the convoys and naval forces. The Allied Forces had done their job well. As the time for the invasion of Mindanao approached, little was left of the 1,500 enemy aircraft once assumed to have been stationed on Mindanao. The actual measure of the destruction of the Japanese Air Force was evident by the number of Japanese aircraft that were to make an appearance over the island during the VICTOR V operation. Throughout the campaign, only five enemy aircraft were sighted over Mindanao. Even though the enemy controlled two dozen airstrips on the island, American air supremacy was complete.

As soon as possible after X Corps had gone ashore on Mindanao, MAG-24 was to be flown from Luzon to the Malabang airstrip, situated 150 miles east of Moret Field. Upon its arrival on Mindanao, MAG-24 was to operate under the direction of Colonel Jerome as part of MAGsZam in an organizational scheme closely resembling that previously existing on Luzon.

Since the guerrillas appeared to be in firm control of the Malabang area, the landing force sent to Malabang was reduced from a division to one battalion. Instead, the main assault was made at Parang, 17 miles to the south. This decision, which involved changing the entire assault plan at sea, was reached after Lieutenant Colonel McCutcheon of MAG-24 had personally reconnoitered the Malabang area several days before the landings. The Marine aviator conferred with guerrilla leaders on the ground and, accompanied by one of them, Major Rex Blow, an Australian who had been captured by the Japanese at Singapore and who subsequently had found his way to the Philippines, flew back to Zamboanga. These two men proceeded by small boat to join the Mindanao-bound invasion convoy on the afternoon of 16 April. “Information these two men furnished

to the X Corps commander, firmed the decision to land at Parang rather than Malabang.”39

The landings at Parang proceeded without incident early on 17 April, following an unnecessary two-hour cruiser and destroyer bombardment. Fighters, dive bombers, and medium bombers from Moret Field maintained vigil over Parang and Malabang. Incessant sweeps over the highways of Central Mindanao kept the movement of enemy troops to a minimum. An Army Air Forces air support party, in direct contact with the Marine pilots, directed the aircraft to targets that included enemy supply dumps, troop concentrations, and installations. Eighteen dive bombers of VMSB-341 and 17 SBDs of VMSB-142 circled over the beachheads, subject to call by the support air party. At the same time, 20 Corsairs of VMF-211 flew combat air patrol over the beaches; another 10 Corsairs from VMF-218 protected the cruiser force offshore.

First Marine unit ashore at Parang was AWS-3, which landed at noon and set up radio equipment on the beach. VMSB-244 personnel landed at Parang along with the main body of X Corps. The remainder of the Marine aviation units landed later in the day three miles north of Malabang Field. Movement of personnel and equipment to the airstrip was impeded by heavy rains, muddy roads, and bridges which had been demolished by guerrillas or the withdrawing enemy. In the words of the U.S. Army X Corps commander: “As to bridges, they had been destroyed by guerrillas time and again until I don’t believe there was a highway bridge intact in the whole island.”40

With the help of Army engineers, Malabang Field was readied for the flight echelon of MAG-24. When the first planes of MAG-24 arrived from Luzon on 20 April, the pilots and crews found an engineering line already set up and a camp area beginning to take shape. First of the dive bomber squadrons to arrive was VMSB-241, followed by VMSB-133 and -244 during the following two days. The Marines renamed the airstrip Titcomb Field in honor of Captain John A. Titcomb who had been killed while directing an air strike on Luzon.

On 21 April, AWS-3, meanwhile redesignated as the 77th Fighter Control Center, assumed fighter direction and local air warning responsibility from the control ship. The air warning squadron’s radio and radar equipment operated around the clock; personnel monitored two radar search sets, in addition to eight different radio channels at various frequencies in the high frequency and very high frequency bands.41

The advance of the 24th and 31st Infantry Divisions towards the east coast of Mindanao near Davao and towards the southeastern tip of the island towards Sarangani Bay made good progress in the days following the invasion. On 22 April, MAG-24 initiated operations from Titcomb Field to support the advance of the Army divisions, one day ahead of schedule. Technically, MAG-24 came under the control of MAGsZam. In practice, because of the distance between Moret and Titcomb Fields, MAG-24 operated practically as a separate unit. Night fighters and local combat air patrols for Titcomb Field were made available by MAGsZam to MAG-24 from aircraft stationed at Moret Field.

The operations of MAG-24 on Mindanao differed considerably from those of Marine aviators elsewhere in the Philippines. The X Corps retained control of the air support strikes because of the distances support aircraft had to fly to provide support and the existence of two separate Marine air groups, not including elements of the Thirteenth Air Force which furnished heavy strikes. The circumstance that the two infantry divisions were operating in widely separated zones, plus the necessity of close coordination with the guerrillas, all combined to make a centralized control indispensable.

To facilitate close control over air strikes, support air parties were attached to X Corps and the two infantry divisions. The support aircraft officer worked closely with the division air officer and provided communications facilities for direct support requests. In addition to the support air parties, the Army 295th Joint Assault Signal Company (JASCO) made available 12 forward air control teams equipped with short-range radio gear mounted in jeeps for air-ground communication. These teams were apportioned between the two infantry divisions for the primary purpose of directing close support strikes.

The technique employed on Mindanao was unusual in other respects. Due to the organizational setup, a constant air alert was maintained overhead to minimize the delay between requests for air support and the actual strikes. JASCO teams were used throughout the Mindanao campaign. With the support air parties thus reinforced, there was no need to shuffle the JASCO teams from one line unit to the other as strikes were required. Instead, a battalion commander could request air support with reasonable assurance that the strike would be carried out without undue delay.

As the two infantry divisions of X Corps advanced across Mindanao, SBDs from Titcomb and Moret Fields ranged ahead of the Army troops, driving the enemy from roads and villages in the path of the American advance. Despite demolished bridges and sporadic resistance, the advance of the ground forces proceeded ahead of schedule. On 27 April, the 24th Infantry Division seized

Digos on the east coast of Mindanao and pivoted northward towards Davao; the capital city of the island fell on 3 May, after the infantry had covered a distance of 145 miles in 15 days. The 31st Infantry Division, advancing northward through the Mindanao Valley seized Valencia on 16 May and Malaybaley several days later.

Marine aviators employed napalm bombs for the first time on Mindanao on 30 April, when they were dropped on an enemy held hill near Davao. The results of this attack were such, that, according to an official Army account:–

From this time on, fire from the air was available, with strikes as large as thirty-two 165 gallon tanks being dropped on a target. In several instances, entire enemy platoons were burned in their positions and in other cases, flaming Japanese fled from positions, only to encounter machine gun fire from ground troops.42

On 8 May, three SBDs of VMSB-241 and eight dive bombers from VMSB-133 flew a spectacular strike against an enemy strongpoint west of Sayre Highway opposite Lake Pinalay. At this point, elements of the 124th Infantry Regiment, 31st Infantry Division, were encountering heavy enemy resistance. Since the weather was closing in, and the opposing forces were only about 200 yards apart, there was a great risk involved to the friendly troops in obtaining close support. Nevertheless, such support was forthcoming in what the Marine pilots subsequently termed “the closest support mission yet flown by VMSB-241.”43 Yellow panels were employed to indicate friendly positions. The target was marked with smoke, and nine SBDs, in a neat example of precision bombing, unloaded nearly five tons of bombs within the 200 yard area. The Japanese position was completely eliminated. The grateful commander of 3/124 requested the Marine ground controller to radio the following message to the Marine pilots:–

Jojo (133) and Dottie (241) flights gave finest example of air-ground coordination and precision bombing I have ever seen. Debris from the bombs fell on our men but none was injured.44

As the 24th Infantry Division approached Davao, the normal combat air patrol was increased from three to six aircraft. At the same time, an intensive effort was under way to break up the Japanese defensive positions near the city. As a result, the pace reached between 150 and 200 sorties a day. The largest number of strikes in one day involved 245 aircraft, dropping 155 tons of bombs.45 Attempts by Marine aviators to have close air support gain the acceptance of the ground troops had by this time come full circle. As early as the drive through the Sulu Archipelago, one observer noted:–

... the sight of the jeeps with their Marine insignia was a matter of course to the infantrymen. Close air support was no longer novel or a matter of unusual interest to the soldiers. It was always there. It always worked. It was now just a part of the first team.46

Far from having to fight for acceptance, some Marine pilots on Mindanao found that “the infantry was apt to call

for planes to hit a pin-point target that any hard-driving rifle squad could have retaken. However, such enthusiasm was much preferred to indifference.”47

During the latter part of May, Japanese resistance in the mountains east of the Sayre Highway stiffened appreciably. Even though, by this time, the X Corps operations on Mindanao had entered the mop-up and pursuit phase, rough terrain and poor trails in the mountainous regions of the island hampered the advance of the infantry. At the same time, heavy rains curtailed aerial observation of Japanese activity. As American troops advanced farther into the mountains, the enemy began to fight doggedly for every inch of ground.

In order to drive the Japanese from one of their strongholds, Marine dive-bomber pilots tried out yet another tactic on 1 June. This new method involved the saturation bombing of a very small area. No less than 88 SBDs attacked an enemy troop concentration and gun positions with a variety of bomb loads, including napalm. No enemy fire greeted the advancing infantrymen, who had expected to encounter stubborn resistance.

The stage for the biggest air strike on Mindanao was set when, on 19 June, a 31st Infantry Division artillery spotter aircraft observed large contingents of enemy troops moving into the Umayam River Valley in northern Mindanao. On the following morning, additional liaison aircraft flew over the area and reaffirmed the presence of enemy concentrations, but unfavorable weather precluded any offensive action from the air. On 21 June, all Marine aircraft that could be spared were requested to hit this area. Airborne coordinators in artillery spotter planes directed 148 dive bombers and fighter bombers to the target. During a four-hour period, the planes unloaded 75 tons of bombs on bivouac areas, supplies, buildings, and marching troop columns. Because of inclement weather, observation of results was limited; nevertheless, a number of large fires were clearly visible, bodies were observed floating in the river, and individual Japanese could be seen fleeing before the strafing aircraft. Subsequent reports indicated that about 500 Japanese were killed in this attack.

Despite bad weather and occasionally fanatical enemy resistance in the mountains of central and northern Mindanao, the handwriting was on the wall for the Japanese remaining on the island. On 30 June, General Eichelberger declared he eastern Mindanao operation completed and reported to General MacArthur that organized opposition on the island had ceased. Actually, isolated Japanese units were to continue fighting right up to the end of the war, and during the period 30 June through 15 August, American and Filipino guerrilla units killed 2,235 Japanese in addition to the more than 10,000 enemy killed on Mindanao prior to 30 June,48 U.S. Army casualties through 15 August had numbered 820 killed and 2,880 wounded.49 Among the Marine aviators who did not survive the Mindanao operation was Lieutenant Colonel Sarles, the energetic commander of VMB-611,

whose PBJ failed to pull up after a low level attack on the Kibawe Trail in northern Mindanao on 30 May.50

During the period of 17 April through 30 June, Marine aviators flew a total of 10,406 combat sorties in support of X Corps, and dropped a total of 4,800 tons of bombs. Nearly 1,300 five-inch rockets were fired in low level attacks against Japanese installations during the same period.51 From the first strategic attack until the final Japanese defeat, more than 20,000 sorties of all types of aircraft were flown in support of the Mindanao Campaign.52

On 12 July, Marine aviators in the Philippines carried out their last major support mission of the war when they flew cover for an amphibious landing team of the 24th Infantry Division at Sarangani Bay in southern Mindanao. With few exceptions, Marine and Allied aircraft had exhausted all profitable targets by mid-July. As far as the liberation of the Philippines was concerned, Marine aviation had fully achieved the objective it had set for itself: close air support that was consistently effective, and a menace only to the enemy.

Conclusion of Philippine Operations53

By late April 1945 the main objectives of American operations in the Philippines had been accomplished: MacArthur’s forces had seized strategic air bases which could be used to deny the enemy access to the East Indies; at the same time, American forces had gained control of bases in the Philippines from which an invasion of Japan could be mounted. In addition, the Allied advance through the Philippines had freed the majority of Filipinos from Japanese occupation. In a futile attempt to stem the American advance through the Philippines, the Japanese had sacrificed more than 400,000 of their troops.54 When the war ended, more than a 100,000 Japanese—including noncombatant civilians—still remained in the archipelago. While the main body of American troops were preparing for an assault against Japan proper, the remnants of erstwhile proud Japanese garrisons in the Philippines were reduced to impotence and forced to forage for scraps to keep themselves alive, hunted by Americans and Filipinos alike.

For Marine aviators in the Philippines, the summer of 1945 brought changes both in personnel and equipment. On 1 June, Colonel Lyle H. Meyer turned over the command of MAG-24 to Colonel Warren E. Sweetser, Jr.55 Two days later, after 26 months’ service in the Pacific Theater, General Mitchell relinquished his command of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing and AirNorSols

to Major General Louis E. Woods who, as a lieutenant colonel, had organized and commanded the wing at Quantico during the summer of 1941. General Woods was to recall: