Appendices

Appendix A: Marine POWs1

Capture

All but four of the 2,274 Marines who became prisoners of war in World War II were taken by the Japanese. The known exceptions were Marines assigned to the Office of Strategic Services, better known as the OSS, who were captured in 1944 by German forces while engaged in covert activities in company with the French underground. Of the remainder of the Marines who were captured, 268 died en route to or in prison camp, and 250 men, who were known to have been captured but are otherwise unaccounted for, are presumed to have died. A total of 1,756 captured Marines returned to the jurisdiction of the United States; a very small number of these were escapees, and the rest were liberated at the end of the war.2 The majority of the Marine POWs had been captured early in the war. The rest, mostly aviation personnel, fell captive to the Japanese after the beginning of Marine air operations in the Allied South Pacific drive.

On 8 December 1941 (Manila Time), Japanese forces took their first Marine prisoners of war—the officers and men of the American Embassy Guard, Peiping, and of the Marine Legation Guard, Tientsin. A detail of 22 men from the Tientsin detachment was captured while stockpiling supplies at the Chingwangtao docks in anticipation of an immediate evacuation. The North China Marines were scheduled to depart Chingwangtao on 10 December 1941 in the President Harrison, which had evacuated the 4th Marines from Shanghai during the last week of November.

At approximately 0800 on the 8th, however, about 1,000 Japanese troops surrounded the Tientsin barracks, while three enemy planes circled overhead. The Marine gate sentry phoned his commanding officer, Major Luther A. Brown, and stated that a Japanese officer wanted

to speak to him.3 The officer, a Major Omura who was well known to Brown, brought a written proposal that all officers and men be assembled in one place in the barracks compound, and all of their weapons and equipment in another, while the Japanese took over. The alternative to surrender was “that the Japanese would enforce their proposal with the troops at hand.”4

Brown told the major that he would sign the proposal only if the Japanese accorded his men the privileges due them under the Boxer Protocol to which Japan and the United States had been signatories. Following a telephone conversation with the local Japanese commander, Lieutenant General Kyoji Tominaga, with whom Brown had been friendly in prewar days, Major Omura stated that Tominaga agreed to the stipulation and that Japan would honor it if valid. Brown believed that this stipulation should have guaranteed the repatriation of his men.5

General Tominaga arranged for Brown to telephone Colonel William W. Ashurst, senior Marine officer in North China and commander of the American Embassy Guard in Peiping. Ashurst told Brown that he was accepting a similar Japanese proposal and advised the Tientsin Marine commander to do the same.6 The embassy and legation guards thought that if they offered no resistance, they would be considered part of the diplomatic entourage and therefore would be repatriated. Unfortunately, the basis for this belief was nonexistent. Because their initial treatment was relatively mild, and because they received repeated informal Japanese assurances that they would be repatriated, the Marines made no attempt to escape.7

Following the establishment of communications with the Japanese Government through Swiss diplomatic channels for the purpose of setting up the exchange of Japanese and American consular officials, the United States attempted to get Japan to recognize the diplomatic status of the North China Marines. In a telegram on 26 December 1941, the Swiss Government was requested to inform Japan that “The United States Government considers that its official personnel subject to this exchange includes ... the marine guards remaining in China and there under the protection of international agreement. ...”8

In reply, Japan stated that “it is unable to agree to include United States Marine Guards remaining in China as they constitute a military unit.”9 The United States was busy at this time setting up the exchange program overall,

and informed the Imperial Government through Swiss channels that it would revert to this point at a later date. Japan inferred from this statement that “the United States Government do not insist in inclusion of the Marine Guards in the present exchange.”10 This inference was incorrect because on 13 March, when it provided a list of the Americans to be repatriated, the Department of State referred to what it had said previously regarding the return of the Marine guards and stated that it expected the Japanese Government “to take cognizance of their true status as diplomatic guards.”11

Neither Major Brown nor Colonel Ashurst, who had surrendered the Peiping guard at 1100 on 8 December, knew of this diplomatic interchange. On 3 January 1942, the Peiping Marines were brought to Tientsin and quartered with Brown’s troops. At Major Brown’s intercession, Major Edwin P. McCaulley, who had retired and was living in Peiping but was recalled to active duty as the Quartermaster for the Peiping Guard, was relocated by the Japanese to a Tientsin hotel, and later returned to the United States on the first exchange ship.12

On the 27th, the entire group of Marines was moved, together with all personal effects, by train to Shanghai, where a Japanese officer told them in English as they entered the prison camp, that “they were not prisoners of war although they would be treated as such and that North China Marines would be repatriated.”13 Until the exchange ships left without the Marines, the men believed that they would be repatriated. Brown said after the war that they were convinced that they were at least slated to be returned to the United States, but that the excuse the Japanese gave for failing to send them back was that there was not enough room for them on board the exchange ships.14 This may have been a valid excuse, for many grave problems concerning shipboard accommodations arose which threatened the whole repatriation process.15

On 2 February 1942, the North China Marines arrived at Woosung prison camp, at the mouth of the Whangpoo River near Shanghai, where they joined the Marine survivors of Wake Island who had arrived on 24 January. Also at Woosung were a handful of Marines, who, unlike the others, received diplomatic immunity and were to be repatriated later in 1942. These men were Quartermaster Clerk Paul G. Chandler, First Sergeant Nathan A. Smith, Supply Sergeant Henry Kijak, and Staff Sergeant Loren O. Schneider, all members of the 4th Marines who had been left at Shanghai to settle government accounts after their regiment had sailed for the Philippines.16 For some unknown reason, unless they had been gulled into

believing so, the Japanese thought that these last four were part of the U.S. consular staff at Shanghai and therefore entitled to diplomatic immunity.

Chandler and the other three Marines became prisoners on 8 December, and were transferred several times to other prisons in the Shanghai area before they, too, arrived at Woosung. This was a former Japanese Army camp, approximately 20 acres overall, and completely enclosed with two electrified fences. The buildings were all frame structure and unheated. Most of the prisoners were not dressed warmly enough to withstand the biting Chinese winter, and all were insufficiently fed.17

The second group of Marines to become captives of the Japanese were the 153 members of Lieutenant Colonel William K. MacNulty’s Marine Barracks, Sumay, Guam, including the 28 Marines assigned to the Insular Patrol (Police). Saipan-based Japanese bombers hit the island of Guam on 8 December (Manila Time) and again on the 9th. The Guam Marines took up positions in the butts of the rifle range on Orote Peninsula and, after making all possible preparations for a stiff defense, awaited the anticipated Japanese assault.

It was not long in coming, for early on the 10th, two separate enemy forces landed, one above Agana, and the main group below Agat. Aware of the overwhelming superiority of the enemy and in order to safeguard the lives of Guamanian citizens, Captain George J. McMillin, USN, Governor of Guam, surrendered the island to the Japanese shortly after 0600. Scattered fighting continued throughout the day as the enemy spread out over the island and met isolated pockets of opposition. Nonetheless, the defenders could offer only token resistance to the well-armed Japanese, who quickly had control of the entire island.

On 10 January 1942, the American members of the Guam garrison were evacuated to prison camps in Japan. After a five-day sea voyage, the prisoners arrived at the island of Shikoku and were imprisoned at Zentsuji,18 where they remained until they were transferred in June 1942 to Osaka on

North China Marines, en route to prison camp in Shanghai, are paraded through the streets of Nanking by their captors on 10 January 1942. (Photograph courtesy of Colonel Luther A. Brown)

POW quarters at Fengt’ai, where the Woosung prisoners were held for a short time before being transferred to camps in Japan. (Photograph courtesy of Colonel Luther A. Brown)

Honshu. First Sergeant Earl B. Ercanbrack, as senior Marine noncommissioned officer of the Guam men, became camp leader at Osaka from the date of their capture until October, when Japanese Army authorities turned the POWs over to the tender mercies of civilian guards and work supervisors. Until that time, the Marines were treated fairly. Although the Marines were assigned to heavy manual labor both at Osaka and Zentsuji, none of the men felt that the “work was unfair or the treatment other than just and honorable.”19 This situation changed after the middle of October when the POWs were treated “as criminals, subjected to ridicule and humiliation, and ... suffered cruel and unjust punishment without opportunity to offer protest or seek justice.”20

Some of the Guam prisoners believed that it was not entirely proper to work so hard for the enemy, and a number of the POWs at Osaka “formed a somewhat informal, loose group or faction who felt that it was our duty to slow down the National (Jap) War Effort. We never seemed to properly understand the Jap guards, we stumbled, spilled bags, caused minor damage and bettered our own morale but did little real damage to their war effort.”21 In October 1942, 80 men of the Osaka camp were called out of formation, advised that they had been observed by prison authorities, who had decided that the Americans were noncooperative and therefore to be transferred to a more severe camp. “So this group, half USMC and half USN (known thereafter as the ‘Eighty Eight Balls’) were sent to Hirohata to work as stevedores shoveling coal and iron ore at Seitetsu Steel Mills.”22

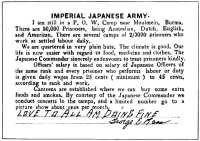

Perhaps some insight into the reasons underlying Japanese treatment of prisoners may be found in the following statement made by a senior enemy officer to Ercanbrack’s group on the day that it was transferred to Hirohata camp, west of Osaka. The Japanese colonel told the Americans that:

We were cowards, else we would have killed ourselves as brave Japanese soldiers would have done, that he could not forget that our comrades in arms were killing Japanese brothers and husbands, that we

chose the disgrace of a cowardly surrender and that we must suffer.23

As Japanese war reverses mounted and Allied planes began bombing the Home Islands, the lot of the POWs grew worse.

After a heroic stand against tremendous odds, on 23 December the defenders of Wake Island surrendered to become the third group of Marines to be captured by the enemy. The Wake prisoners were comprised of the survivors of the 1st Defense Battalion detachment and VMF-211.24 Also taken at the same time with these Marines and a few Army Air Corps and Navy personnel were some 1,100 civilian contract employees who were actively engaged in constructing new and extensive defenses on the island when war struck.

Immediately following the capitulation of the Wake Island garrison,25 the men were subjected to numerous indignities regardless of rank. By sunset of 23 December, all of the Americans on the island had been rounded up. Commander Winfield S. Cunningham, the island commander, Major James P.S. Devereux, the senior Marine officer on Wake, and eight others were confined in a one-room cottage. Most men of the Marine detachment had been taken at their defense positions, but not before they had dismantled and destroyed their personal weapons and had damaged beyond any further use their crew-served pieces. Those wounded prior to 23 December and those who had been hospitalized for other reasons had been placed in an underground ammunition magazine for protection from Japanese bombs.

Both the wounded and others captured after the enemy landings were held under guard at the VMF-211 aircraft parking area until dusk on 25 December, when they were marched around the island to the vacated civilian barracks. At this time, the wounded who were completely unable to walk were taken to the improvised hospital mentioned above. “During this period of approximately 54 hours, there was no medical attention of any kind, no form of protection from the sun by day and cold rain by night, no food, and almost no water.”26

On 11 January 1942, the Americans were alerted that they would be evacuated to prison camps shortly. A group of regulations, violation of any one of which could result in the death penalty, was read to the prisoners. Amongst the heinous crimes for which they could be executed were such things as: “talking without permission and raising loud voices,” “carrying unnecessary baggage in embarking,” and “using more than two blankets.”27

Early on the morning of 12 January, the prisoners were herded aboard the Nitta Maru, a relatively new Japanese passenger liner; enlisted Marines, sailors, and civilians were placed in the holds, while the officers and the senior civilian supervisor were locked in the mail room. Left on the island were approximately 300 civilian construction workers, who were to rebuild installations there, and another 100 or so civilians and servicemen who were too ill to be moved. Most of those who remained were later evacuated to prison camps in either China or Japan. Tragically, nearly 100 of the civilians were lined up on a beach on Wake the night of 7 October 1943 and executed by a machine gun firing squad. For this crime, Rear Admiral Shigematsu Sakaibara—the Japanese commander of Wake—and a number of his officers were tried, found guilty, and hanged after the war’s end.28

Dressed in whatever tattered tropical clothing they could find29 and carrying only the barest minimum of personal possessions allowed by their captors, the Americans spent 12 days on board the ship under very difficult conditions. They were systematically deprived of their valuables, fed only sporadically, not permitted to talk to one another, and given no room for exercise. On 18 January, the ship arrived at Yokohama, where the squadron commander of VMF-211, Major Paul A. Putnam and a number of other men were removed and taken to camps in Japan. Six days later, the Wake prisoners arrived at Shanghai. Here they were told that they would be paraded through the city and marched out to the Woosung camp. Somehow the parade did not materialize.30 Major Devereux particularly remembered the bitter cold the prisoners felt at Yokohama and Shanghai, for they were only partially clad in khaki uniforms and not acclimated to the change from the tropical weather of Wake.31 Once the Americans arrived at Woosung, the Japanese Navy relinquished its responsibility for the POWs to the Army. Most of the Wake prisoners remained at Woosung until they were transferred in December to Kiangwang, five miles away. In May 1945, they began a journey that was, for most of them, to end eventually in Japan.32

Chronologically, the next group of Marines captured belonged to the Marine detachment of the USS Houston. This heavy cruiser, together with the Australian light cruiser HMAS Perth and two other Allied naval vessels, had been ordered to block the Japanese invasion of Java and to destroy the enemy attack force headed for Banten Bay on the northwest corner of the Dutch colonial possession. Shortly after midnight of 28 February, Perth and Houston, outnumbered in a punishing engagement with Japanese warships guarding the landing force, were sunk within 40 minutes of each other. Of the more than 1,000 men on the Houston, only 368 survived; 24 of this number were Marines from the 74-man detachment.

Even before their capture, the lot of the survivors was not an easy one. Oil-soaked and half-drowned—many of them wounded—they remained in the water or on life rafts for eight hours or more. Some of the men were picked up by Japanese landing craft between dawn and 0800 on 1 March. They were taken to the beach on St. Nicholas Point, Banten Bay, where they were pressed into unloading enemy transports and hauling supplies.33 Many of the men had neither clothes nor shoes and were covered from head to toe with fuel oil from the ships that had been sunk. These men became badly sunburned, and to aggravate matters, they were given little or no medical attention or food and “no water ... as the Japs didn’t have any themselves. There were a few cases of beating to hurry up the work—this was the main Japanese landing and the invaders were obviously pressed for time.”34

The captives were fed rice and meat balls late that night and the following morning, when the officers were separated from the enlisted prisoners and trucked to the town of Serang. On 2

March, in a temperature of 100 degrees, the enlisted sailors and Marines, barefooted and lightly clad, were marched the nearly 30 miles to Serang over a concrete highway, pushing Japanese ammunition and supply carts all of the way.

Some Houston survivors were picked up by a Japanese transport ship, which took them on board, searched them, and then returned them to their life rafts. One of the Americans put on a life jacket, swam to shore, and spent three days in the coastal hills trying to join Allied forces on Java. Unfortunately for this Marine, natives found him and turned him over to Japanese troops. Another life raft, with four Marines and two sailors aboard, drifted for three days around the northwest coast of Java and through the Sunda Strait. On the afternoon of 3 March, it was beached at Laboehan (Labuan), and the six Americans took to the jungles. After two days of thrashing about they met Javanese natives who promised to guide them to Dutch forces, but instead led them right to a Japanese machine gun position.35

It was believed that many of the men who survived the sinking of the Houston reached the beaches of Java, only to be killed outright by natives armed with knives. On the march from Serang to Batavia, the natives stoned the POWs and otherwise abused them with little or no interference from the Japanese guards.36

Before the end of the week following the loss of the Houston and Perth, all Allied survivors of the naval engagement had been captured and detained in Serang. Conditions here were very bad; dysentery and malaria broke out among the prisoners, who were afforded little medical relief. The captives went almost completely without food, and by the end of March, they began succumbing to beriberi and other diseases caused by malnutrition.

Between 12 and 15 April, the POWs were removed from Serang to Batavia, where they were interned in a former Dutch military cantonment known before the war as the Bicycle Camp, for some unknown reason. Under vastly improved conditions, the prisoners remained here until October, when after a transfer first to Shanghai, they were again transferred, this time to Burma where their real ordeal began.

When they were captured, members of the 4th Marines experienced somewhat different circumstances than had the Houston Marines. Following its withdrawal from Shanghai, the 4th Marines landed on 30 November and 1 December 1941 at the U.S. Naval Station, Olongapo, on Subic Bay, Luzon, Philippine Islands. Immediately after the Japanese attack on the Philippines, the regiment was committed to action along with other forces which had been stationed in the islands. After an epic, four-month-long stubborn resistance, the American and Filipino defenders of Bataan were forced to surrender on

9 April 1942, and the men on Corregidor, nearly a month later on 6 May.37 Collectively, the number of Marines taken prisoner in the Philippines formed the largest Marine contingent the Corps lost at any one time.

Included in the ranks of the 4th Marines captured in the Philippines were men from Marine organizations which had been stationed in the islands when the 4th arrived from China. These units—Marine Barracks, Olongapo, and 1st Separate Marine Battalion, Cavite—were absorbed by the regiment in December 1941 and January 1942. As the fighting progressed, the 4th detached some of its units for commitment where fighting was heaviest and they were needed—and where they were finally captured.

At the end of the war, after Marine Corps authorities had checked all possible sources, official Marine records listed 105 Marines captured on Bataan and 1,283 on Corregidor. Of this number, 490 men never survived for a number of reasons. Some succumbed to wounds received during the fighting, others died because of malnutrition, beatings, and various diseases. Finally, a number of men were executed for illegal or real violations of Japanese prison regulations, some were killed when American aircraft bombed enemy ships transporting prisoners to Japan, and still others were outrageously murdered in a massacre at the Puerto Princess prison camp.

One of the most difficult and trying periods experienced by American POWs is better known as the Bataan Death March, which followed the fall of that peninsula. Much has been written of the suffering, indignities, and atrocities which constituted the common fate of the Americans and Filipinos who surrendered to Lieutenant General Masaharu Homma’s forces. Primarily because of his responsibility for the insensate and uncontrolled brutality of his soldiers during this infamous event, Homma was tried, found guilty, and executed after the end of the war. It would serve no purpose to recount, step by step, the bloody and tragic evacuation of the POWs from Bataan to Camp O’Donnell, a trek that was approximately 85 miles of hell.

Corregidor held out a month longer than Bataan—to 6 May 1942, when at 1200, the white flag of surrender was hoisted over this and the other fortified islands in Manila Bay. Despite these obvious signs of capitulation, the Japanese on Bataan continued to pour artillery fire on Corregidor and enemy aircraft flew sortie after sortie over the island, dropping bombs that day and night. Early the next morning it was quiet; the fighting had ended for the embattled inhabitants of Corregidor, but not the war—and the Japanese were to remind them constantly of this fact in both word and deed until the Americans were liberated over three years later.

Late on the afternoon of the 7th, the Japanese began collecting and concentrating their prisoners in a small beach area near a large galvanized iron building

which had been the garage of an Army coast artillery unit. Enroute to this place of confinement, which eventually was to hold nearly 13,000 Americans and Filipinos, the prisoners were searched many times by Japanese soldiers who took “watches, fountain pens, money, clothing, canteens, mess gear, etc., in fact anything we had that they wanted.”38 This unmitigated thievery, in which Japanese officers also took part, was a commonplace experience of nearly every American prisoner, no matter where or when he had been captured.

Initially, there was neither food nor water for the Corregidor prisoners except for the meager amount they may have been able to keep with them, and “for one well near a partially destroyed garage. The water was of doubtful quality and the amount of water in the well was very small.”39 The POWs’ thirst was so great that they drained the radiators of wrecked automobiles, trucks, and tractors and drank the rusty fluid. A water pipeline was finally installed, “...one spigot of one-half inch pipe for the Americans and one spigot of the same size for the Filipinos,”40 who had been segregated from the others. It was frequently necessary for an individual to stand in line for 24 hours before he could fill his canteen, and often a guard would walk up and turn off the spigot, apparently as a form of punishment. Particularly aggravating the suffering of the prisoners was the weather, for May is the hot season in Luzon.

This in itself created serious health problems, because many bodies on the island remained unburied until approximately 10 days after the surrender. A Navy chaplain, who remained on Corregidor for two months after the Japanese took over, told another prisoner that some bodies were not found and buried until the first or second week of June.

In addition to the hardships imposed upon the prisoners by the enemy and their difficulty in adjusting to their status as captives, all POWs—regardless of rank—were required to salute or bow to every Japanese soldier—from private to general—whose paths they crossed. Non-observance of this regulation resulted in a beating of various degrees of severity. As a matter of fact, prisoners could be and very often were beaten on the slightest pretext or for no reason at all. This was one aspect of the character and personality of the Japanese which American POWs were unable to fathom for the entire period of their captivity.41

Prisoners were fed sporadically during their first few days of captivity on Corregidor, and only those who were

lucky or energetic ate during this time.42 At the first Japanese ration issue, the food was distributed inequitably. After this, some form of discipline and order appeared in the ranks of the POWs, and the Americans took charge of the ration issue.

The Japanese numbered each prisoner and divided the entire group of POWs into divisions of 1,000. These divisions were then sub-divided into groups of 100. Rations were allotted according to the strength of each division, which issued the food to the 100-man groups. In some cases, group kitchens had already been established. In other instances, three or four cooking groups were formed which took the entire ration, cooked it, and then apportioned it to their members on an equitable basis. In this manner, every prisoner was fed and nourished on the same sort of starvation diet as his fellows.

Because the Japanese authorities were not unduly concerned with enforcing sanitary regulations and establishing some sort of discipline and order within the ranks of the POWs, the prisoners took it upon themselves to organize a military police company of approximately 100 men, nearly half of whom were Marines. Physical and moral persuasion were employed by the MPs since the company had no real authority to enforce its orders. In spite of the boiling sun, the swarms of flies, the paucity of food and water, and the lack of even minimal sanitary facilities, conditions improved considerably once the full weight and effect of the MP company were asserted.

On the night of 22 May, a heavy, cold rain fell on Corregidor, worsening the miserable lot of the prisoners. At dawn the next day, they were told to pack their belongings and prepare to leave the island bastion. After considerable confusion and milling about, the POWs were marched to the docks, and loaded aboard several vessels in the bay, where they spent the night under absurdly crowded conditions. Early on the morning of 24 May, the men were herded into landing barges, put ashore at the southern end of Dewey Boulevard in Manila, and marched through the city to Bilibid Prison in the infamous Japanese “Victory Parade.” The Japanese, in the words of one of the prisoners:

... compelled the Filipino civilians to attend the parade, many of whom cried while others tried to slip us food. The Filipinos ... caught giving food to the Americans were brutally punished by the Japs. We had only one short water stop during the hike. Many people dropped out because of the terrific heat, heavy packs, almost no sleep for three days. ... Everyone had to keep hiking until they passed out, then a truck picked up the unconscious and brought them in.43

The prisoners were herded into old Bilibid Prison, where all remained until the morning of the 25th. Early that day, the first of several groups to be transferred was moved by train to prison camps located in the vicinity of Cabanatuan, approximately 75 miles north of

Manila. The rail trip was a trying ordeal for the already ill-treated prisoners. At some stops on this trip, “the Filipinos tried to give the prisoners food and candy and sometimes succeeded.”44 Groups of 100 were crowded into boxcars in which there was just enough room for each man to stand up during the six-hour trip. A total of 1,500 men in four groups left Bilibid and were sent to Cabanatuan Camp 3, a march of 20 kilometers from the town. The remainder of the Corregidor prisoners were sent to Camps 1 and 2, not too far from 3. Because of a severe water shortage at Camp 2, it was evacuated after the POWs had been there two days and the men were sent to one of the other two camps.

While at Bilibid Prison, all American officers in the grade of colonel and above were segregated from the rest of the prisoners for transfer to camps other than those set aside for lesser ranked POWs.45 One of the officers transferred was Colonel Samuel Howard, the commander of the 4th Marines. His group was moved on 3 June to a prison camp outside of Tarlac, Luzon, where it remained until 12 August. Among these officers was Lieutenant General Jonathan M. Wainwright, the former commander of American forces in the Philippines and the senior American officer present in camp. On 12 August, the officers were entrained for Manila, and placed on board the Nagara Maru, which sailed the following day for Formosa, leaving behind American soldiers, sailors, Marines, and civilians, and Filipino servicemen. All were to endure months of hard labor, starvation, mistreatment, and numerous indignities at the hands of the Japanese before General MacArthur’s forces liberated the Philippines.

Tragically, the last Marines captured in a group in the Pacific War were nine members of Lieutenant Colonel Evans F. Carlson’s 2nd Raider Battalion, which raided Makin Island in the Gilberts on 17–18 August 1942. Although this raid was successful within the limits imposed on the overall operation, serious consequences resulted from its aftermath. Following their surprise landing, the Marine raiders had killed every enemy soldier on the island and destroyed many of the Japanese supply dumps and facilities there. When the battalion had completed its mission and attempted to return to the submarines which had carried it to Makin, the Marines found that the surf was heavier than had been expected and were unable to maneuver their rubber craft through the breakers to clear water. The submarines remained submerged through most of the 18th, but moved into the mouth of the island lagoon at approximately 1930 that evening. There they met and took aboard tattered raiders, who had managed to jury-rig their rubber boats to a native outrigger canoe, in which they were able to negotiate the tossing surf. Both submarines then immediately departed for Pearl Harbor.

Nobody knew it at the time, but nine Marines had been left behind. They were captured later by Japanese reinforcements which mounted out of a nearby

island garrison on 18 and 20 August. Thirty-three Japanese flew in to the atoll on 20 August, and a larger group arrived at Makin on a ship the following day. These Japanese reported that they found 21 Marine bodies, 5 rubber boats, 15 machine guns, 3 rifles, 24 automatic rifles, 350 grenades, “and a few other things.”46

The captured Marines received satisfactory care at the hands of their captors on Makin, and humane treatment continued for nearly a month after they had been moved to Kwajalein. Early in October, Vice Admiral Koso Abe, Marshall Islands commander, was advised that he need not send these prisoners to Tokyo. A staff officer from a higher headquarters told Abe that a recently established policy permitted the admiral to dispose of these men on Kwajalein as he saw fit. Abe then ordered the Marines beheaded. A native witnessed the executions, and based on his and other testimony in war crimes trials after the war, Abe was convicted of atrocities and hanged at Guam. Captain Yoshio Obara, Kwajalein commander who had been ordered to arrange the executions, was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment, and Lieutenant Hisakichi Naiki, also involved in the affair, was sentenced to 5 years in prison.47

After the capture of the men left on Makin, the only Marines to fall into Japanese hands were individual pilots and aircraft crewmen whose planes were shot down over or near enemy territory. The story of Major Gregory Boyington, VMF-214 commander and recipient of the Medal of Honor, who was shot down over Rabaul on 3 January 1944, in general reflects the experiences of other Marine aviators who were downed and survived, only to become prisoners.

After Boyington’s plane was hit and set afire, he parachuted and landed in the water. He spent eight hours in his life raft before being picked up and taken to Rabaul by a Japanese submarine. In the middle of February 1944, Boyington and five other POWs were flown from Rabaul to an airport on the outskirts of Yokohama by way of Truk, Saipan, and Iwo Jima. Upon setting down on Japanese soil, the six prisoners were walked from the airport to a point outside of Yokohama and trucked a distance to a streetcar terminal. Here they boarded a trolley which took them to a Japanese Navy-run POW camp at Ofuna, the prewar Hollywood of Japan.

Processed through or at Ofuna were captured Allied submariners, pilots, and technicians whom the enemy believed could provide special information of value. Holding Boyington and some others as captives rather than POWs, the Japanese never reported their whereabouts or existence to the International Red Cross and these men were therefore listed as missing or killed in action. Boyington remained at Camp Ofuna until the last months of the war, when he was transferred to Camp Omori near Tokyo, and there he was liberated.

With the exception of those aviators who were downed near Chichi Jima in

the Benin Islands and executed there, most pilots and crewmen underwent to a greater or lesser degree the same incessant round of beatings and interrogations as had Major Boyington. The severity of their initial period of captivity depended on where they had been captured and who their captors were as well as how long it took before they were transported to POW camps in Japan.

OSS Marines

[qzqzqz ??? See Herringbone Cloak—GI Dagger: Marines of the OSS for a detailed history of these Marines.]

The circumstances of the capture and subsequent imprisonment of the four Marines captured by the Germans in Europe were considerably different than the experiences of the men taken in the Pacific. Interestingly enough, the Marines in Europe were captured within a few days of each other, although they were on different missions. Major Peter J. Ortiz, and Sergeants John P. Bodnar and Jack R. Risler went into captivity on 16 August 1944, and Second Lieutenant Walter W. Taylor on the 21st.

Ortiz was a veteran OSS-man who, before entering the Marine Corps in 1941, had served with the French Foreign Legion and risen through the ranks of that organization. He was an officer at the time of the fall of France when captured by the Germans for the first time. He escaped from a POW camp in Austria and made his way to the United States by way of Lisbon, Portugal. He returned to France as a member of a three-man interallied mission called UNION, which was dropped in southeast France on the night of 6–7 January 1944 to impress maquis48 leaders in the Rhone Valley and Savoy regions that “‘organization for guerilla activity especially on or after D-Day is now their most important duty.’”49 Although the agents on this mission were dropped in plain clothes, they took their uniforms with them, and the leader of the group claimed that they were “the first allied liaison officers to appear in uniform in France since 1940.”50 “Ortiz, who knew not fear, did not hesitate to wear his US Marine captain’s uniform in town and country alike; this cheered the French but alerted the Germans, and the mission was constantly on the move.”51 Their task completed, the UNION group was withdrawn from France and returned to England in late May 1944.

The Marine officer returned to the Haute Savoie region of France again on 1 August 1944 with a mission entitled

UNION II. This was an all-American group of seven men headed by an OSS Army major and containing Ortiz, Sergeants Bodnar and Risler, a third Marine sergeant, Frederick J. Brunner, and several other men. Dropped with these agents were numerous containers of supplies for the maquis in the region. The quickening pace of French guerrilla activities here as well as elsewhere in France made these units the objects of German search parties, and particularly in this area for it was still under the control of strong enemy forces. For the Haute Savoie, Allied liberation was still in the future.

On 16 August, Ortiz and his group were surrounded by a Gestapo party in the vicinity of Centron, a small village in the Haute Savoie region just south of Lake Geneva, the local headquarters of the OSS team. Ortiz surrendered because he believed that if he and his men shot their way out of the entrapment, local villagers would undoubtedly suffer reprisals for German deaths which a fire fight surely would have produced.52 Brunner, however, managed to escape the trap, swam a swiftly flowing river to the other side of the village, and traveled across 15 miles of enemy-held territory to reach the relative safety of another resistance group.53

Upon their capture, Ortiz and the others passed through a series of German POW camps before they finally arrived at Marlag–Milag Nord. This was a group of POW camps for Allied naval and merchant marine personnel in Westertimke (Tarmstadt Oest), which was located in a flat, sandy plain between the Weser and Elbe Rivers, 16 miles northeast of Bremen.

Lieutenant Taylor, the other Marine captured in Europe, was the operations officer of the OSS intelligence team assigned to the 36th Infantry Division, Seventh Army, for the invasion of Southern France in the Cannes–Nice area. On D plus 5 (20 August 1944),

Taylor, his section chief, and a Marine sergeant attached to the team went behind German lines to determine what German intentions were—retreat or fight. Taylor and an agent recruited from a local resistance group were to reconnoiter Grasse—15 miles inland and directly west of Nice, Recalling this mission, Taylor said:

I was to stay behind with the agent and the Citroen [a car the two had “liberated”], accomplish the mission of taking him in and waiting and then taking him out; and then we were to get to the 36th as fast as we could. The agent had been leading the Resistance fight against the Germans ever since the landing and was absolutely exhausted, falling asleep time and time again while we were briefing him. ... At dawn the next morning, the agent and I headed for the town of St. Cezaire, which was declared to be in the hands of the Resistance and where I was to let the agent down and wait for his return from Grasse. However, during the night, due to Allied pressure on Draguignan and Fayence, what evidently was a company of Germans had taken up positions in St. Cezaire. On approaching the dead-still town by the steep and winding road, we ran into a roadblock of land mines; we both thought it was Resistance, and the agent took my carbine and jumped out of the car to walk toward the line of mines. He lasted just about 10 feet beyond the car and died with a bullet through his head. I still thought it was the trigger-happy Resistance but started to get out of there ... even faster when I finally saw a German forage cap behind some bushes above the road. But the car jammed against the outer coping, and a German jumped down on the road in front of me and threw a grenade under the car, I tried to get out of the right door and luckily did not, because I would have been completely exposed to the rifle fire from the high cliff on that side above the car. The grenade exploded and I was splashed unconscious on the road. When I came to, I was surrounded.

It might be interesting to note that when I have thought about the incident of my capture I have always pictured us as coming down a long hill and seeing, across a wooded stream valley, the site of the road-block with men in uniform scurrying about and climbing the cliff-embankment. I have always blamed myself for thinking them to be Resistance and not recognizing them as Germans ... and thus causing our trouble and the death of the agent. However, after years of trying, in 1963 I returned to the scene and found that the reality was quite different from my image, that the road did not go down the opposite side of the valley, that there were no trees, that the actual site of the road-block is completely invisible from any part of the road until one is within about 20 yards, in other words that I could not possibly have seen men ... scurrying or been aware of the block.54

The Nazis took Taylor to Grasse for treatment and interrogation. The hand grenade had shredded his left thumb and there were approximately 12 shell fragments embedded in his left leg, “6 of which at last count remain.”55 On the ride to Grasse, being strafed by Allied aircraft all the way, Taylor managed to get rid of an incriminating document by stuffing it behind the seat cushion of the vehicle in which he was riding. In Grasse he was subjected to intensive interrogation, which ended when he vomited all over the uniform of his inquisitor. From 21 August to 10 September, he was passed through and treated at six different Italian and German hospitals in Italy. On the 10th, he was sent to a POW hospital at Freising,

Oberbayern, some 20 miles north of Munich and approximately 17 miles northeast of infamous Dachau.

Six weeks later, Taylor was transferred to a hospital 15 miles further east at Moosburg, where he remained until the end of November, when he was well enough to be placed in a transient officers’ compound nearby. At the end of January, Taylor was sent to the same camp in which Ortiz was imprisoned. On 9 April 1945, the prisoners at the Westertimke camp were given three hours to move out of camp because of the imminent approach of British forces. The suddenness of this move disrupted the escape plans of Taylor, who had prepared and laid aside false identity cards, maps, compass, civilian clothes. food, and other items necessary for an escape between 15 and 20 April. By the 10th, the Germans had moved the prisoners out and onto the road toward Luebeck, northeast of Hamburg. Taylor, Ortiz, and another man planned to leave that night. During the afternoon, however, continuous Allied strafing of the area created such confusion that the three Americans were able to break from the column in which they were marching and make for the nearby woods, where they were joined by a sergeant major of the Royal Marines—another escapee.

For eight days, the men hid in the woods by day and moved at night, intent on evading German troops and civilians. The escapees waited to be overrun by British forces and made some attempt to find Allied front lines, whose positions were uncertain and, from the sound of the gunfire they heard, were constantly changing. When they could not make contact with the British, the escaped POWs returned to the vicinity of the camp from which they had been moved. Their food soon gave out and two of the party became sick from drinking swamp water, whereupon they returned to the camp to find it, to all intents and purposes, in the hands of the Allied prisoners. Merchant seamen and ailing military personnel had replaced the nominal guard left behind by the Germans. In fact, on the night that the runaways returned, the British prisoners took over the actual guarding and administration of the camp. On 29 April, British forces liberated the prisoners, and on the next day they were trucked out of the area for return to their respective countries.

Prison Camps: Locations, Conditions, and Routine

Article 77 of the Geneva Protocol states that, on the outbreak of war, each of the belligerents was to establish an information bureau, which would prepare POW lists and forward them to a central information agency, ostensibly to be organized by the International Red Cross. By this means, information about POWs could be sent to their families. The Protocol, in addition, stipulated that each of the belligerents was bound to notify the others within the shortest possible time of the names and official addresses of prisoners under its jurisdiction.

For nearly a year after the attack on Pearl Harbor, it was virtually impossible for the United States to obtain reliable information concerning Americans

imprisoned by the Japanese.56 It was not until the war had ended and the POWs were liberated that the families of a number of them found out that they were still alive. The special prisoner category into which Major Boyington fell is an example of this. Another was that of the survivors of the Houston whose existence was not known until very near the end of the fighting.

The Casualty Division at Headquarters Marine Corps maintained the records of Marines reported to have been taken prisoner. Information concerning Marine POWs came from such sources as the Provost Marshal General of the Army, the Department of State, the International Red Cross, as well as from reports of escaped prisoners. As soon as the Casualty Division definitely learned that a Marine was a POW, his next of kin was notified and asked to keep in touch with the HQMC Prisoner of War Information Bureau. As long as the individual Marine continued in a POW status, his allotments were paid and his pay and allowances accrued to his benefit. If authoritative word was received that a Marine had died in a prison camp or that he had been killed in action, his account was closed out and all benefits paid to his beneficiaries.

Soon after the North China, Wake, and Guam Marines had been captured, the Casualty Division was able to list them as POWs. Little of what had happened to the Marines captured in the Philippines was learned until a considerable time after their imprisonment. The Japanese were quite slow in reporting the names of prisoners or of Allied personnel who had died in prison camp. The enemy also had an irresponsible attitude about forwarding mail from POWs to their families or delivering mail to the prisoners despite major attempts to open lines of communication through neutral powers for this purpose.

In the summer of 1943, the Japanese restricted the number of words on incoming letters to 25 per message, and mail sent by POWs was limited to only a few words on a form with a printed message supplied by their captors.

Marine POWs were imprisoned in some 33 camps located in Burma, China, Formosa, Japan, Java, Malaya, Manchuria, the Philippines, and Thailand. Very often they were transferred through a series of camps before they were liberated. The North China and Wake Island Marines were imprisoned initially at Woosung camp, outside of Shanghai. The prisoners’ quarters consisted of seven ramshackle barracks, each of which was “a long, narrow, one-story shanty into which the Japs crowded two hundred men.”57 Adjacent to the end of the buildings were toilets and a wash rack. Facing the toilets., much too close for normal standards of sanitation, was the galley where the POWs’ food was prepared. Administrative offices, quarters for the guards, and storerooms comprised the rest of the camp area. Surrounding Woosung was an electrified fence, and inside that

another electrified fence was erected around the barracks and the toilets. In the time that the prisoners remained at this camp, two of them were electrocuted when they accidentally touched the wire barrier. According to Colonel Luther A. Brown, who was in this camp, “one Marine POW was murdered by a Japanese sentry with rifle fire at close range. Colonel Ashurst demanded that the sentry be tried and punished, however, the Japanese transferred the sentry.”58

Each prisoner was given a mattress filled with straw and two cotton blankets for his bedding, but the Japanese covers were so skimpy, they were:

... not half as warm as one ordinary American blanket. The jerry-built barracks gave little protection against the intense cold, and during the bitter winter we were soon pooling our blankets and sleeping four in a bunk to keep from freezing to death.59

Living conditions at Woosung were not particularly good, nor was Japanese treatment of the prisoners gentle. Each morning and evening, the POWs fell out in sections of approximately 36 men for a roll call. Invariably one or more of

the men would be slapped or beaten for such minor offenses as not standing at attention or appearing to be inattentive.60

According to Major Devereux:

The guards were brutal, stupid, or both. They seemed to delight in every form of abuse, from petty harassment to sadistic torture, and if the camp authority did not actively foster this type of treatment, they did nothing to stop it.61

One former Marine POW has written in retrospect:

Possibly their actions reflected their basic training. On the first night in Woosung, Major Brown heard a rumpus in the guard-room nearby. On going to the door he saw the Japanese sergeant of the guard strike a private in the face, then the private bowed to the sergeant, and the same routine [was] repeated several times until the private’s nose was bloody.62

One of the most brutal guards at Woosung was a civilian interpreter by the name of Isamu Ishihara, who had learned English in Honolulu where he had been educated and later worked as a taxi driver. This man was dubbed the “Beast of the East” by the prisoners he “flogged, kicked, and abused. ...”63

One day in Woosung, for no apparent reason, Ishihara became infuriated with Sir Mark Young, the former Governor General of Hong Kong, and whipped out his sword to strike the elderly Briton. Major Brown of the Tientsin Marines twisted the sword out of Ishihara’s hands and made him back off. Brown suffered no punishment for this daring act. Immediately after this episode, Captain Endo, the Japanese camp executive officer, beat Ishihara with a 2x4 board, and the interpreter was forbidden thereafter to wear a sword.64

Other incidents in the camp reflected what appeared to be the Japanese respect of force, firm action, or courage. At one evening check, Ishihara struck a Marine platoon sergeant. The sergeant returned the blow, knocking the Japanese to the ground. On rising, the latter approached the sergeant, placed his hand on the Marine’s shoulder, and said, “You are a good soldier.”65 Later, on the event of the Emperor’s Birthday, the Marine sergeant was given a reward for being a “model POW.”

One of those who experienced Ishihara has written:

The following anecdote may well be apocryphal, but I have heard it from several sources. Ishihara ... tried to turn himself in as a war criminal when the trials were being conducted in Japan. At first the investigators brushed him off as the Japanese version of the compulsive confessor who harasses our police with confessions to all the crimes he reads about in the newspapers. But he was persistent, and finally his story was confirmed by statements made by the survivors of his lunatic fits of rage. ... At his trial, the prosecutor asked Ishihara why his hand was bandaged. Ishihara replied, ‘If I were Japanese soldier, I commit harakiri when Japan surrenders; but since I am only civilian working for Army, I only cut off little finger, that’s enough.’ Anyway ...

all of us who knew ‘Ishi’ believe it fits him to a ‘T.’”66

The Japanese attitude toward their prisoners was expressed many times in various ways. One Christmas, a prison camp commander left no doubt in the minds of his charges about their status when he told them:

From now on, you have no property. You gave up everything when you surrendered. You do not even own the air that is in your bodies. From now on, you will work for the building of Greater Asia. You are the slaves of the Japanese.67

Colonel Ashurst, the senior officer prisoner, continually protested the treatment the POWs were receiving and attempted to get the Japanese authorities to recognize the Geneva Protocol as the basis on which Woosung should be run, but to no avail. A representative of the International Red Cross visited Woosung after the POWs had been there for eight or nine months, and managed to arrange for a few shipments of food and supplies to the prisoners. The general attitude of the Japanese captives was that without these Red Cross food and medical parcels, many more prisoners would not have survived the war.

The food at Woosung consisted of a cup of rice and a bowl of watery vegetable soup for breakfast and dinner, and a loaf of bread weighing approximately 150–160 grams (less than half a pound) and vegetable soup again for supper. These rations were supplemented with whatever else the prisoners could obtain from the guards by paying exorbitant prices on the black market.

The protests of Colonel Ashurst and the continued visits of members of the Swiss Consulate as representatives of the International Red Cross finally bore fruit, for in December 1942, the prisoners were moved to Kiangwan, five miles distant from Woosung. Here conditions were just slightly improved. At Kiangwan, Colonel Ashurst agreed to have the officers work on a prison farm. The officers labored for approximately 8 to 10 hours daily, from 0730 until 1200 and then from 1300 to 1730 in the summer. Enlisted prisoners worked about the same hours, but their duties were more onerous. The six-acre farm produced vegetables intended for the prisoners, but the produce was occasionally confiscated by the guards.

Following a Japanese raid on the POW farm, Major Brown and several other officers in turn conducted a night raid on the small Japanese garden. Colonel Otera, the camp commander, sent for Brown and permitted him to speak after a long heated tirade during which he brandished his sword in a menacing manner. Brown pointed out that many difficult situations had arisen:

... because of misunderstandings and differences between the Occidental and Oriental philosophies and that therefore the POWs never knew what to do and not do, even though specific rules governing POWs had been requested, but refused since they were ‘part of Japanese Army Regulations and therefore secret.’ Hence the solution to a dangerous situation—watch the Japanese and follow their example. Otera received this remark with great mirth and replied, ‘Don’t ever take Japanese vegetables again and the Japanese will not take yours.’ Thereafter all POW farm produce went to [their] galley

except two shipments Colonel Ashurst agreed to send to the American Civilian Internment Center in Shanghai.68

In another encounter with the Japanese over the POW truck farm, when camp authorities ordered the officers to spread “night soil” on the garden, Colonel Ashurst told them, “‘No, they will not do it. You will have to kill me first.’ The Japanese cancelled the order.”69

The enlisted POWs at Kiangwan worked on a rifle range north of the local military airport from about the beginning of January 1943 to September 1944. This work consisted of very heavy labor, and this, added to their poor diet, resulted in many cases of malnutrition and tuberculosis. In September 1944, the enlisted men were put on other details, such as digging ditches and building emplacements and gasoline storage dumps.

For these labors, the prisoners were paid, but in such small amounts that little was left after ever-increasing deductions were made for such items as food, clothing, heat, electricity, rent, and anything else the Japanese authorities could assess them for. The POWs pooled their last few payrolls at Kiangwan to buy a few pounds of powdered eggs for the sick.70 The POWs began a recreation program, using “recreational equipment donated by the people in Shanghai and delivered ... by the international Red Cross.”71

On 17 March 1942, after the prisoners at Woosung had been forced to sign a paper promising not to escape, Corporals Jerold Story, Connie Gene Battles, and Charles Brimmer, and Private First Class Charles Stewart, Jr., escaped from the prison camp. They headed for the Jessfield Road area outside of Shanghai, where they made contact with a British woman who hid them. The Japanese learned of their presence in the woman’s house, surrounded it on 16 April, and the Marines gave themselves up. The four men were imprisoned in the Jessfield Road Jail in separate cells, interrogated, and beaten. The next day, they were removed to the infamous Bridge House Jail in Shanghai, and questioned for long hours at a stretch over a period of nine days.

During the time that he spent at the Bridge House, Story was beaten on an average of once every three days, and on 29 June 1942, he and his companions were transferred to Kiangwan. Here they were tried by court-martial. The Marines were not told what the charges were, were not given counsel of any sort, and were not even allowed to make a plea. It would not have done any good anyway, because the trial was conducted in Japanese. After the trial was over, the men learned that, Battles, Stewart, and Story had been sentenced to four years in prison, and Brimmer, seven years. It appeared that the latter had been given the longer sentence because the Japanese believed him to be the ring leader. Story recalled that Brimmer had admitted this, even though it was not true, to stop the Japanese from beating him.

When they told Brimmer he got seven

years, we all started to laugh and told him he would be an old man before he left the prison. As we started to walk out of the courtroom the Japs called us back and raised Brimmer’s sentence to nine years, evidently because we had laughed.72

For about 10 days after their trial, the Marines were kept at Kiangwan, but on 9 July 1942, they were removed to Ward Road Gael in Shanghai. This was a completely modern prison used only for those POWs convicted and sentenced by Japanese courts for “criminal offenses.” On 9 October 1944, Story, together with a British and an American naval officer, sawed the bars out of their cells, climbed down ropes which they had manufactured from blankets, and escaped over the prison wall into Shanghai. The three eventually made their way to Chungking and freedom.

On the night of their escape, they met other prisoner-escapees from the .jail. These men were Commander Winfield S. Cunningham, Brimmer, Stewart, another Marine, and a Navy pharmacist’s mate. These men were recaptured. In March 1942, Cunningham and the head of the construction gang on Wake, Nathan Dan Teeters, had escaped from Woosung, only to be recaptured almost immediately. Apparently in response to continuous American complaints about the treatment of U.S. prisoners, on 11 December 1942 Japan notified the United States by cable through Swiss channels of the attempted escape in March of Cunningham and the Marines and said:–

Plan escape made by persons in question constitutes grave violation (Japanese Law of 1915) regarding punishments inflicted prisoners war, their chief in this case Commander Cunningham liable death penalty according this law. Nevertheless, Japanese authorities showed clemency and condemned them to punishment which considered very light compared gravity accusations. As consequence Japanese government does not see itself in position entertain protest of American Government.73

Commander Cunningham was sentenced to 10 years’ close confinement in prison for the crime of desertion from the Japanese Army, and jailed with Story and the other Marines at Ward Road Gael in mid-1942. Through various channels of information, the United States Government was able to obtain accurate and documented accounts of alleged Japanese violations of the Geneva Protocol occurring in prison camps near large cities which were visited, when permitted, by the representatives of the International Red Cross and neutral observers.

In response to the information it had received about the trials of Cunningham and the others, on 12 December 1942, the United States drew up a well-documented list of complaints, containing the names of the individuals concerned and the incidents in which they were involved, and indicted the Japanese Government for its treatment of civilian and military POWs. The Department of State vehemently protested the illegal sentences imposed on the escapees by the Japanese military court, and emphatically denied the legality of the courts-martial themselves. The United States demanded that the sentences be cancelled, the punishments for the attempted

escapes be given in accordance with the provisions of the Protocol, and that the prisoners be treated with the respect due given to the prisoner’s grade or rank and position. The Japanese did not respond to these demands.74

At Kiangwan as at Woosung earlier, the POWs continued the dull, uneventful routine of prison camp life. Evening roll call was held at 2030, and depending upon the season, between 2100 and 2300, when taps was sounded, the lights went out in the barracks. “Then the hungry, weary prisoners lay in the dark, trying to forget the thoughts a man cannot forget, hoping to sleep until the bugle called them out to slave again.”75

Of these days, Major Devereux recalled:

That was our routine, our way of life for almost four years—except when it was worse. But . . that is only part of the story of our captivity, the easiest part. Hidden behind the routine, under the surface of life in prison camp, was fought a war of wills for moral supremacy—an endless struggle, as bitter as it was unspoken, between the captors and the captives. The stakes seemed to me simply this: the main objective of the whole Japanese prison program was to break our spirit, and on our side was a stubborn determination to keep our self-respect whatever else they took from us. It seems to me that struggle was almost as much a part of the war as the battle we fought on Wake Island.76

To retain their self-respect and maintain a form of unit integrity, even in prison, the POWs established their own internal organization. Such principles of military discipline as respect for seniors and saluting continued despite the situation. The prisoners were generally under continuous pressure from their fellow Americans to remain clean and neat, even under the most difficult circumstances. A recreation program was begun, but was limited in scope because some forms of athletics were too strenuous for the POWs’ weakened condition. Some attempt was made to institute an education program, and in 1942 the men organized classes in mathematics, history, and other subjects of interest. No more than 10 men were allowed to meet at any one time, for any group larger than that was immediately suspected of planning an escape. After the movement to Kiangwan, the education project was abandoned because the work load became too heavy.77

American prisoners at all camps soon discovered that no matter how badly they were treated, they had one defensive weapon they could employ to prevent the Japanese from breaking their pride entirely, and that weapon was their universal observance of military discipline and continued existence as a military organization. Without this defense,

at isolated times the POWs became only a mob of craven creatures upon whom the enemy prison guards could and did visit all forms of cruel and unusual punishment. By maintaining military discipline even while in prison, the officers were able to represent their men properly in dealings with the Japanese and very often prevented the men from suffering heavier beatings than those which were meted out. By acting as a buffer, the officers at times received the punishment due to be given to someone else. And most important, the realization that they were still part of a military organization was a very vital factor in maintaining POW morale at as high a level as possible.

Although the health of the prisoners at Kiangwan could not by any stretch of the imagination be categorized as good, it was not critical and the death rate was very low. A primary reason for this condition was that the POWs were not in a tropical climate and the weather, by and large, was not too bad. Overwork and malnutrition, however, contributed to the high incidence of diarrhea, dysentery, tuberculosis, malaria, influenza, and pellagra. During their more than three years at Woosung and Kiangwan, the prisoners received from the United States three shipments of Red Cross food parcels and medical supplies which undoubtedly sustained the men, although Japanese soldiers pilfered from these shipments and sold the stolen items in Shanghai.

Of these three shipments, the only large one:

... was held by the Japanese while they put pressure on Colonel Ashurst to sign a receipt for the lot. This he refused to do, based on the fact that the supplies (medical and individual boxes) were not under his control. The Japanese tried in many ways, over a considerable time, to get Colonel Ashurst to sign the invoices, but he was adamant. There were some prisoners who wished Colonel Ashurst to sign, evidently hoping to receive some part of the shipment. Apparently under orders from higher authority the camp Japanese finally turned the supplies over to Colonel Ashurst, and he signed for them. As against the strong possibility that little benefit to the POWs would have been derived from the supplies, if signed for without control, Colonel Ashurst’s superb handling of the issue provided us with a significant amount of essential food and medical supplies.78

The Marines at Kiangwan were kept fairly well abreast of the progress of the war, as:

... Sgt Balthazar Moore, USMC, and Lt John Kinney, USMC, and [I] manufactured a short wave radio out of stolen parts and listened fairly regularly to KWID in San Francisco, and BBC from New Delhi. Unfortunately the true reports had to be mixed with spurious information because of the tendency of a lot of people to talk too loud, too long, and in the wrong place at the wrong time. Col Ashurst, Major Brown and Major Devereux were regularly informed of the true context [of the news]. Additionally, small crystal sets were manufactured; lead and sulphur for the crystal; and wire and a ‘Nescafe’ can for the earphone. The shortwave radio set was hidden in various places but perhaps the best place was in the forty to fifty gallon ‘ordure crocks’ in the toilets, or buried under the barracks. The information provided by the short wave radio and the crystal sets (which obtained

Russian newscasts from Shanghai) served to stabilize the morale of the prisoners.79

By March 1945, the POWs began hearing numerous rumors to the effect that they were to be moved from Kiangwan. Although the prison guards insisted that nothing like that was to take place, the POWs began preparing for a journey by discarding possessions they no longer needed and hoarding food and the like for what might turn out to be a difficult trip. Still other prisoners began preparations for an escape during the move. One of the Wake prisoners recalled:

On 8 May 1945 the Japanese organized a working party to go into Shanghai to prepare railroad cars for a move of the prisoners. Two Marine Officers volunteered to accompany the working party in the hope that something could be done that would assist in an escape during the trip. It was well known from information gained from recently captured aviators that the 100 mile stretch of the railroad north of Nanking was virtually in the hands of the Chinese. On arrival at the railroad yard in Shanghai, it was found that the cars to be used were standard Chinese boxcars with sliding doors in the center and windows on either side of the ends. The Japanese instructions were that barbed wire was to be nailed over the windows and barbed wire put up to enclose the ends of the boxcars leaving a space between the doors free for the guards. It was obvious that the only means of escape would be through the windows and that this would be impossible if within full view of the guards. Also provided by the Japanese for each end of the car was a five gallon can to be used as a toilet during the trip. After considerable discussion with the Japanese, they finally agreed that the Officer’s car should provide some privacy for the toilet. This was to be accomplished by removing doors from a nearby Japanese barracks and installing these in the corner of the boxcar, thus enclosing not only the toilet but the window. The barbed wire was carefully put on the window so that it would be easily unhooked. Directly outside of the windows were metal rungs that would provide a ladder to descend prior to jumping to the ground. With this arrangement, it appeared that certainly one person could make an escape, and if the guards were not alert it was possible that several might escape before the decreased numbers would be noticed.80

The main party of 901 prisoners left on 9 May; remaining behind in Shanghai were 25 seriously ill and wounded men. The first leg of the trip, Shanghai to Nanking, approximately 100 miles, took 24 hours. Upon arrival at Nanking, the POWs were taken from the train, marched through the city, and boated to the other side of the Yangtze River, where they reboarded their trains, which had crossed the river empty. On the night of 10–11 May 1945, First Lieutenants John F. Kinney and John A. McAlister, taken prisoner at Wake Island, First Lieutenants Richard M. Huizenga and James D. McBrayer, captured in North China, and Mr. Lewis S. Bishop, a former pilot with the Flying Tigers, escaped from the train.

The following is McBrayer’s account of the escape:–

These four Marine officers had long planned for an escape, slowly accumulating tools necessary to cut through a fence, etc. Once they learned of the planned move of the prisoners by train, they laid plans to cut a hole in the bottom of the boxcars and escape via the ‘rods’ while the train was moving. Fortunately the boxcar in

which they were placed had a small window in the corner which was covered with barbed wire and small iron bars, which they could cut with their stolen tools.

The boxcars had contained forty to fifty officers, about twenty to twenty-five being wired in by barbed wire in each end. Four Japanese guards were in the wired-off middle section between the sliding doors of the boxcars. Blankets and blackout equipment was placed over all openings in the car because of U.S. aircraft strikes. Huizenga, Kinney, McAlister, and McBrayer placed the ‘five gallon gasoline can toilet’ near the window in their end of the car so as to give a reasonable excuse to be near the blacked out window.

The POW train left Nanking traveling north toward Tientsin about midnight, the four Marine officers took turns going to the ‘head,’ and cutting the wires and bars when it appeared the Japanese guards were not looking or alert, particularly while the guards were eating supper.

The four Marine officers planned to jump off the train about midnight near the Shantung border because of the Communist 8th Route Army operations in that area. They planned to jump in pairs as Huizenga and McBrayer each spoke some Chinese, but Kinney and McAlister did not. However, each had a small ‘pointee-talkee,’ which a Chinese-American had prepared for them in camp in the event the officers became separated. When the time came to escape—about midnight—the officers discovered there were no hand holds on the side of the car, consequently they could not hang on and jump in pairs. [Therefore,] it was out of the window and out into the black night.

The prison train was making about forty miles per hour when each jumped into the black unknown. Each officer had to time his approach to the window when the four Japanese guards were not looking, and slide up under the blanket covering the window and jump. Consequently the individual officers were strung out up and down the track for many miles. Lewis Bishop ... had not been included in the escape plans, but when he saw the hole he followed. Each officer was quite battered by the jump from a fast moving train. Each one also had ... [a] harrowing experience prior to establishing contact with friendly Chinese guerrillas. The latter brought the five escaped officers together in about five days; it was only then that the four Marines knew Bishop had jumped from the train.

The five ... stayed with the Chinese guerrillas and made a long swing to the east and joined elements of the Chinese Communist New Fourth Army. They traveled with the Chinese Communist troops until they reached the boundary between the Chinese Communist and Chinese Nationalist Armies. An apparent armistice was declared between the two Chinese forces, and the escapees were transferred to the Nationalist troops. At this point the escape seemed in doubt as both the ... Communists and the Nationalists told [the Americans], ‘the other side will kill you and blame it on us to cause trouble with your government.’ Fortunately, the treatment of the escapees by the guerrillas, the Communists and the Nationalists, was excellent, and the former POWs gained strength and weight.

During their tour of the Anwhei–Shantung provincial areas the escapees attended many patriotic rallies, and always they were requested to sing the American National Anthem. As they could not really sing the ‘Star Spangled Banner’ and do it justice, they invariably responded with the Marine Corps Hymn. So if part of China today thinks ‘From the Halls of Montezuma’ is the U.S. National Anthem, you know who to blame: Huizenga, Kinney, McAlister, and McBrayer, Marines, and Bishop, a Marine ‘by adoption.’81

Aided by the Chinese forces, the five Americans finally reached an emergency airstrip at Li Huang on 16 June, and subsequently returned to the United States. The night after these five

escaped, two civilian prisoners also left the train; one made a successful getaway, but the other was recaptured and badly beaten.

On 14 May, the prison caravan reached Fengt’ai, slightly west of Peiping, where there were fewer facilities, less food, and more miserable conditions than at either Woosung or Kiangwan. At Fengt’ai:

All prisoners were put in a large warehouse. Instead of rice, flour was announced as the staple food. Claiming that flour, per se, was an impossible diet the POW mess officer demanded that the Japanese provide some means to process this into bread. An oven was finally located (it had belonged to the N. China Marines in Peiping) and bread production started.

Later, the Japanese ordered the mess officer to make hardtack ‘for the Japanese Army’ and hundreds of pounds of hardtack poured out of the oven, put into sacks and stored. Much thought went into the manufacture of this hardtack, unfortunately. When the prisoners later arrived in Hokkaido the hardtack was there, to be a part of our ration. It was completely spoiled and inedible. Our sabotage of the Japanese war effort had boomeranged.82

Approximately a month later—on 19 June—the POWs began another trip by boxcar, this time to the port of Pusan in Korea, which had an infinitely worse camp than the previous ones the prisoners had been in. After three days here, they were packed into the crowded lower deck of a ferry steamer, which transported them to Honshu. When unloaded, the POWs:

... again were crowded into trains and sent around the island of Honshu via Osaka and Tokyo by train and ferry to the island of Hokkaido, where they were regrouped in various camps in the mining area, The officers were separated from the enlisted men and put in a small compound, meeting there a group of Australian officers, The men were sent to a number of camps where they found Australian, Indonesian and other prisoners.83

They remained on Hokkaido until liberated.

In the southern part of Japan, the Guam Marines were put to work in earnest at Zentsuji in early March 1942, two months after their arrival. For their first major task, they had to construct rice paddies on the side of a mountain near the prison camp. AS one Marine recalled:

The axes that were used to knock down the trees were the most modern equipment I saw on the entire project. The rest of the equipment was even more basic—hoes, rakes, a shovel or two, and hands.84

Groups of prisoners were continually transferred to other camps from Zentsuji in the months following their arrival. In May 1942, one such group was sent to Osaka Prisoner of War Camp 1, which was actually a warehouse not far from the docks of this port city. As a matter of fact, most of the POW camps situated in such metropolitan areas of the country as Tokyo, Osaka, Kobe, and Yokohama were in warehouses or buildings of the same type. In violation of other articles of the Geneva Protocol, many of these city camps were directly in the center of strategic areas, and the men imprisoned there were forced to work as stevedores, loading and unloading war material from military transports.

The majority of the camps in Japan, however, were situated in rural or suburban locales. The stockades consisted of several areas of fenced-in grounds and one- and two-story wooden barracks of the kind generally used by the Japanese Army.

Some Guam Marines were transferred in October 1942 to Hirohata Sub-Camp, which was within the Osaka camp groupment. Hirohata was administered by enlisted Japanese Army personnel, and by hanchos, or civilian labor supervisors who wore a red armband to mark their authority, and who had the power of life and death over their hapless captives. Although otherwise unarmed, the hanchos carried clubs or bamboo sticks of some sort which they wielded with relish on all ranks whether provoked by the prisoners or not.85 Most of these civilians and many of the soldiers at the camp conducted black market activities, selling at exorbitant prices to the prisoners Red Cross supplies, food, and other items that the men were entitled to.