Part II: Okinawa

Blank page

Chapter 1: the Target and the Enemy

Background1

Once the Joint Chiefs of Staff decided on Okinawa as a future target, intensive planning and preparations were begun for the assault on this once obscure island. Large amounts of information of varying importance poured into the intelligence centers concerned with the impending operation, and were added to files already bulging with a store of knowledge of the Ryukyus group. Okinawa soon became the focus of attention of the CinCPac-CinCPOA headquarters and staff members who, in compliance with the JCS directive to Admiral Nimitz “... to occupy one or more positions in the Nansei Shoto,”2 filled in the details of an outline plan. A flurry of disciplined activity immediately engulfed the commands and staffs of the expeditionary forces assigned to the assault as they began their operational studies for ICEBERG, the code-name given to the approaching invasion.

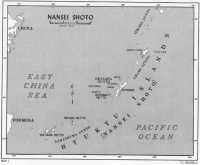

The strategic importance of Okinawa was its location, and all other considerations stemmed from this. The Japanese viewed it as an integral link in a chain of islands, the Ryukyus or the Nansei Shoto, which formed an effective barrier to an Allied advance from the east or southeast towards the Chinese mainland, Korea, or the western coast of Japan. This group of islands was ideally situated to aid in the protection of the Japanese maritime lines of supply and communication to imperial conquests in southeast Asia. The island chain also provided the Japanese Navy with the only two substantial fleet anchorages south of the Home Islands3 between

Kyushu and Formosa, and numerous operating bases for aircraft of all types as well. (See Map 1.)

From the Allied point of view, the conquest of Okinawa would be most lucrative. As the largest island in the Ryukyus, it offered excellent locations for military and naval facilities. There was sufficient land area on the island on which to train and stage assault troops for subsequent operations against the heart of the Empire. Kyushu was only 350 nautical miles away, Formosa 330 miles distant, and Shanghai, 450. Two other major purposes of the impending invasion were to secure and develop airbase sites from which Allied aircraft could operate to gain air superiority over Japan. It was expected that by taking Okinawa, while at the same time subjecting the Home Islands to blockade and bombardment, Japanese military forces and their will to resist would be severely weakened.

Okinawa: History, Land, and People4

Before Commodore Matthew C. Perry., USN, visited Okinawa in 1853–54, few Americans had ever heard of the island. This state of ignorance did not change much in nearly a century, but American preinvasion studies in 1944 soon shed some light on this all-but-unknown area.

The course of Okinawa history—from the Chinese invasions about 600 A.D. until Japanese annexation in 1879—was dominated by an amalgamation of Chinese and Japanese cultural and political determinants. For many years, the Chinese influence reigned supreme. After the first Chinese-Okinawan contacts had been made, they warred against each other until the island peoples were subdued. Shortly after 1368, when the Ming Dynasty came to power, China demanded payment of tribute from Satsudo, the King of Okinawa. The payment was given along with his pledge of fealty as a Chinese subject.

In the midst of incessant Okinawan dynastic squabbles, Chinese control remained loose and intermittent until 1609, when the Japanese overran the island, devastating all that stood in their way. The king of Okinawa then reigning was taken prisoner, and a Japanese local government was established temporarily.

For the next 250 years, the Okinawan Kingdom, as such, was in the unenviable position of having to acknowledge both Chinese and Japanese suzerainty at the same time. Finally, in May 1875, Japan forbade the islanders to send any more tribute to China, whose right to invest the Okinawan kings was now ended. In the face of mounting Okinawan protests against this arbitrary action, Japan followed its decree by dethroning the king in March 1879; he was reduced in rank, becoming a marquis of Japan. Okinawa and its neighboring islands were then incorporated within the

Map 1: Nansei Shoto

Japanese political structure as the Okinawan Prefecture. Over the years, China remained restive at this obvious encroachment, until the question was one of many settled in Japan’s favor by its victory in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894.

The islands to which the Japanese successfully gained title, the Ryukyu Retto, were in the southernmost of two groups which make up the Nansei Shoto. The shoto is a chain of islands which stretch in a 790-mile-long arc between Kyushu and Formosa, separating the Pacific Ocean from the East China Sea. One of the groups which make up the Ryukyu Retto is the Okinawa Gunto.5 The other four major island groups in the retto are Osumi, Tokara, Amami, and Sakishima. Okinawa Gunto is located at the half-way point in the arc and consists of Okinawa and numerous smaller islands. These include Kumi Shima, Aguni Shima, Ie Shima, and the Kerama Retto in the west; Iheya Retto and Yoron Shima in the north; and a group of small islands, named the Eastern Islands by the Americans, roughly paralleling the east central coast of Okinawa.

The island of Okinawa is narrow and irregularly shaped throughout its 60-mile length. (See Map 2.) In the north, the Motobu Peninsula juts out into the East China Sea and extends the island to its maximum breadth, 18 miles; immediately to the south is the narrowest part, the two-mile-wide Ishikawa Isthmus. The coastline of the island ranges in nature from a precipitous and rocky shore in the north, through a generally reef-bound lowland belt just below the , isthmus, to an area of sea cliffs and raised beaches in the south. Landing beaches suitable for large-scale amphibious operations were neither numerous nor good. The most extensive flat areas and largest beaches on the east coast were found along the shores of Nakagusuku Wan (or bay) and, on the west coast, in the area between Zampa Misaki (or point) and Oroku Peninsula. Two major fleet anchorages existed, both on the eastern side of the island: Nakagusuku Wan (later named Buckner Bay by the Americans in honor of the Tenth Army Commander) and Chimu Wan. The leading port of the Okinawa Gunto was on the west coast at Naha, the major city of the island group. Port facilities elsewhere were limited to small vessels.

Okinawa is easily divisible into three geographical parts, each one physically different from the other. The territory north of the Ishikawa Isthmus, constituting about two-thirds of the island area, is largely mountainous, heavily wooded, and rimmed with dissected terraces—or one-time flatlands which became deeply ravined by the ravages of erosion. About 80 percent of the north is covered with a dense growth of live oak and conifers, climbing vines, and brush. The highlands, rising to rugged peaks, 1,000 to 1,500 feet in height, dominate the area. Small, swift streams drain the clay or sandy-loam topsoil of the interior which is trafficable under most conditions. Cross-country movement is limited mainly by the steepness of the hills and the lush

Map 2: Okinawa Shima

vegetation. The few roads that existed in 1945 were mostly along the coast.

The middle division, consisting of that area lying between Ishikawa Isthmus and an east-west valley running between the cities of Naha and Yonabaru, is broadest in its northernmost part. Just south of the isthmus is an area resembling northern Okinawa, but the rest of the sector is, for the most part, rolling, lightly wooded country interrupted by steep cliffs and ravines. The few streams, flowing through hills which rarely exceeded a height of 500 feet, are generally narrow and shallow, so they could be easily bridged or forded.

The southernmost tip of the island, triangular in shape, is extremely hilly and was dominated by extensive limestone plateaus, some reaching over 500 feet in height. At each angle of the base of the triangle is a peninsula, Oroku on the west, and Chinen on the east.

The primary roads built by the Japanese were little more than coral- or limestone-surfaced trails, varying in width from 12 to 16 feet, on a sand and clay base. Use of these roads depended largely upon the weather, since rain reduced them to sticky and slow-drying morasses. In the dry season, the slightest movement on the roads threw up dense clouds of dust. The major arteries threaded along the coastlines, branching off into a few cross-island roads which then broke down into a capillary system of trails connecting the small villages, settlements, and individual farms. The central sector, the densely populated part of the island, contains an intricate network of roads. Only one, the broad stone-paved highway connecting the cities of Shuri and Naha, could support two lanes of traffic. In this area, the road net was augmented by a narrow gauge railway, with approximately 30 miles of track. This system provided the major trans-island communications net, running from Naha to Yonabaru on the east coast, via the towns of Kobakura and Kokuba, while trunk lines linked Kobakura and Kokuba with the west coast towns of Kadena and Itoman, respectively.

Okinawa’s climate is tropical, with moderate winters, hot summers, and high humidity throughout the year. The annual temperature range is from a minimum of 40 degrees to a mean maximum of 95 degrees in July. The months of May through September are marked by a heavy and erratic rainfall. During the typhoon season (July–November), torrential rains and winds of over 75 miles-per-hour have been recorded.6 During the rest of the year, except for brief downpours, good climatic conditions generally prevail.

The inhabitants of Okinawa in 1945 were heirs to a complex racial mixture. The original population is believed to have been a branch of the hairy Ainu and Kumaso stock which formerly inhabited Kyushu and other Japanese islands. A Mongoloid strain was introduced when Japanese pirates, who made Okinawa their headquarters, engaged in their time-honored habit of kidnapping women from the Chinese mainland.

Malayan blood was infused into this melting pot through intermarriage, immigration, and invasion. This evolution produced a people with the same basic characteristics as those of the Japanese, but with slight physical differences. The Okinawans are shorter, darker, and are inclined to have more body hair.

The 1940 census gave an estimate of slightly over 800,000 people in the Nansei Shoto as a whole, with nearly a half-million of these on Okinawa proper. Farmers constituted the largest single population class, with fishermen forming a smaller, but important, group. Approximately 15 percent of the Okinawa populace lived in Naha, and within this community were most of the higher officials, businessmen, and white collar workers—most of them Japanese who either had emigrated or been assigned from the Home Islands.

During the period of the Okinawan monarchy, there was an elaborate social hierarchy dominated by nobles and court officials. After Japanese annexation, the major social distinctions became those that existed between governing officials and natives, between urban and rural inhabitants, and between the rich and the poor—with the latter in the majority. Assimilation of the Japanese and Okinawan societies was minimal, a situation that was further irritated by the preferential treatment tendered by the Japanese to their fellow-countrymen when the more important administrative and political posts were assigned.

Another chasm separating the Japanese and Okinawan was the difference in languages. Despite a common archaic tongue which had branched into the language families of both Okinawa and Japan, there were at least five Ryukyuan dialects which rendered the two languages mutually unintelligible. The Japanese attempted to reduce the language barrier somewhat by directing that standard (Tokyo) Japanese was to be part of the Okinawan school curriculum. Several decades of formal education, however, failed to remove the influence of many generations of Chinese ethnic features which shaped the Okinawan national characteristics. The Chinese imprint on the island was such that one Japanese soldier noted that “the houses and customs here resemble those of China, and remind one of a Chinese town.”7 The natives retained their own culture, religion, and form of ancestor worship. One outward manifestation of these cultural considerations were the thousands of horseshoe-shaped burial vaults, many of impressive size and peculiar beauty, which were set into the sides of numerous cliffs and hills throughout the island.

The basic Okinawan farm settlement consisted of a group of farmsteads, each having the main and other buildings situated on a small plot of land. The farmhouses were small, thatch-roofed, and set off from the invariably winding trailside by either clay or reed walls. The agricultural communities generally clustered around their own individual marketplaces. Towns, such as Nago and Itoman, were outgrowths of the villages, differing only in the fact that these larger settlements had several modern business and government structures.

The island’s cities, Naha and Shuri, were conspicuous by their many large stone and concrete public structures and the bustle that accompanies an urban setting. Shuri was the ancient capital of the Ryukyuan kingdom and its citadel stood on a high hill in the midst of a natural fortress area of the island.

The fundamentally agrarian Okinawan economy was dependent upon three staple crops. About four-fifths of southern Okinawa was arable, and half of the land here was used for the cultivation of sweet potatoes, the predominant foodstuff of both men and animals. Sugar cane was the principal commercial crop and its cultivation utilized the second largest number of acres. Some rice was also grown, but this crop consistently produced a yield far below local requirements. Since rice production was sufficient to satisfy only two-thirds of the population’s annual consumption needs., more than 10 million bushels had to be imported annually from Formosa.8

Industrial development on the island was rudimentary. The Naha–Shuri area was the leading manufacturing center where such items as alcoholic beverages, lacquerware, and silk pongee were produced. Manufacturing was carried out chiefly in small factories or by workers in their homes. The only relatively important industry carried on outside of the Naha–Shuri complex was sugar refining, in which cattle supplied the power in very primitive mills. The fishing trade, of some importance, centered around Naha and Itoman. There were also small numbers of fishing craft based at all of the other usable harbors on the island; however, lack of refrigeration, distance to the fishing grounds, and seasonal typhoons all hindered the development of this industry and prevented its becoming a large source of income for the Okinawans.

From the very beginnings of the 1879 annexation, the Japanese government made intensive efforts to bring the Ryukyuan people under complete domination through the means of a closely controlled educational system, military conscription and a carefully supervised system of local government. The prefectural governor was answerable only to the Home Minister in Tokyo. Although the elected prefectural assembly acted as the gubernatorial advisory body, the governor accepted, rejected, or ignored their suggestions as he saw fit. On a local level, assemblies elected in the cities, towns, and townships in turn elected a mayor. All local administrative units were, in effect, directly under the governor’s control, and their acts or very existence were subject to his pleasure.

In every aspect—social, political, and economic—the Okinawan was kept in a position inferior to that of any other Japanese citizen residing either on Okinawa or elsewhere in the Empire. This did not prevent the government from imposing on the Okinawan a period of obligated military service.9 The periodic

call-ups of age groups was enforced equally upon the natives of Okinawa and the Ryukyus as on the male inhabitants of Japan proper. This provided Japan with a reservoir of trained reservists from which it could draw whenever necessary.

With the exception of those drafts of reservists leaving for active duty elsewhere, Okinawa, for all practical purposes, was in the backwash of the early stages of World War II. The island remained in this state until April 1944, when Japan activated the Thirty-second Army, set up its headquarters on Okinawa, and assigned it responsibility for the defense of the island chain.

the Japanese Forces10

Following the massive and devastating United States naval air and surface bombardment of Truk, 17–18 February 1944, and the breaching of the Marianas line shortly thereafter, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarter awakened to the obviously weak condition of the Ryukyus’ defenses. Prior to 1944, little attention had been paid to the arming of the Nansei Shoto. The island group boasted two minor naval bases only, one at Amami O-Shima and the other at Naha, and a few small Army garrisons such as the Nakagusuku Wan Fortress Artillery Unit on Okinawa.11 Acting with an alacrity born of distinct necessity, IGHQ took steps to correct this weakness in the Empire’s inner defensive positions by expediting and intensifying:

... operational preparations in the area extending from Formosa to the Nansei Islands with the view of defending our territory in the Nansei area and securing our lines of communication with our southern sector of operations, and thereby build a structure capable first, of resisting the enemy’s surprise attacks’ and, second, of crushing their attempts to seize the area when conditions [change] in our favor.12

In order to improve Japanese defenses in the Ryukyus, IGHQ assigned this mission on 22 March 1944, to the Thirty-second Army, the command of which was assumed formally on 1 April by Lieutenant General Masao Watanabe. At Naha, headquarters of the new army, staff officers hoped that enough time would be available for adequate fortification of the island. All planning was tempered by memories of the immediate past which indicated that “an army trained to attack on any and every occasion, irrespective of conditions, and with no calculation as to the real chances of success, could be beaten soundly.”13 Added stimuli to Japanese

preparations were the American invasions of Peleliu and Morotai on 15 September 1944. By this time, the Japanese high command became quite certain that either Formosa, the Ryukyus, or the Bonins, or all three, were to be invaded by the spring of 1945 at the latest. Initially, Japanese Army and Navy air forces were to blunt the assaults in a major air counteroffensive. The establishment of Allied air superiority and demonstrated weaknesses of Japanese air forces, however, caused the military leaders in Tokyo to downgrade the aviation role in the coming struggle for the defense of the Home Islands. The ground forces, then, would carry the major burden.

The Thirty-second Army staff planners wasted no time in organizing the ground defenses of Okinawa. They had learned by the cruel experiences of Japanese forces on islands which had been invaded by the Americans that a stand at the shoreline would only result in complete annihilation and that their beach positions would be torn to pieces in a naval bombardment. It became apparent, therefore, that the primary defensive positions had to be set up inland. Then, should the invaders escape destruction at sea under the guns and torpedoes of Japanese naval forces, or at the beachhead under the downpour of artillery shells, the death blow would be administered by the ground forces’ assumption “of the offensive in due course.”14 To steel the troops’ determination to fight and to keep their morale at a high peak, army headquarters devised the following battle slogans:–

One Plane for One Warship

One Boat for One Ship

One Man for Ten of the Enemy

or One Tank.15

The command of the Thirty-second Army was assumed by Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima in August 1944, when General Watanabe was forced to retire because of a continuing illness. Because of the importance of the impending Okinawa battle, IGHQ assigned General Ushijima one of the most competent officers of the Japanese Army, Major General Isamu Cho, as his chief of staff. On 21 January, army headquarters was split into two groups. Ushijima’s operations staff moved to Shuri where the general was to direct his army for the major portion of the campaign. A “rear headquarters” composed of the ordnance, veterinary, judicial, intendance,16 and the greater part of the medical staff set up near Tsukasan, south of Shuri.

Lieutenant Generals Ushijima and Cho17 complemented each other’s military qualities and personality, and formed a command team that reflected mutual trust and respect. They were ably abetted by the only holdover from

the old staff, Colonel Hiromichi Yahara, who retained his billet as Senior Officer in Charge of Operations,18 and Major Tadao Miyake as the logistics officer.19 Ushijima, a senior officer slated for promotion to general in August 1945, was reputedly a man of great integrity and character who demonstrated a quiet competence which., in turn, inspired great confidence, loyalty, and respect from his subordinates. Cho, in comparison, was a fiery, ebullient, and hard-driving individual with a brilliant, inquiring mind. He spared neither himself nor his staff. His abounding energy was effectively counterbalanced by his senior’s calm outward appearance. This combination of personalities was served by comparatively young and alert staff members who were allowed a great latitude of action and independence of thought.

The new commander of the Thirty-second Army inherited a combat organization which had been specially established for the expected invasion of Okinawa. Many independent artillery, mortar, antiaircraft t artillery (AAA), antitank (AT), and machine gun groups supplemented the fire power of the basic infantry units assigned to the army. As a result of the IGHQ decision in June 1944 to reinforce the Okinawa garrison, nine infantry and three artillery battalions were to be sent to augment the force already on the island.20 The majority of the reinforcements arrived from their previous stations in China, Manchuria, and Japan between June and August 1944.

The veteran 9th Infantry Division, first to arrive, possessed battle honors dating from the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5. Coming directly from Manchuria, and scheduled by the high command as the backbone of the defense force, the 9th’s stay on Okinawa was short-lived. The critical situation on Leyte required the assignment of the 9th there, and Ushijima, “...in accordance with orders of Imperial General Headquarters, decided on 17 November to redeploy the 9th Division in order to send an elite unit with a proud and glorious war record to a battlefield where the Imperial Army would engage in a decisive battle.”21

Probably, the most important of all of the factors which may have influenced the course of the coming battle for the Japanese, and favored an Allied victory, was the loss of this division and the fact that it was never replaced. It left in late December for the Philippines by way of Formosa where it sat out the rest of the war, prevented by Allied submarines and airplanes—and MacArthur’s landing on Luzon in January—from either continuing on to its destination or returning to Okinawa.22

Thirty-second army officers site for a formal portrait in February 1945. Numbers identify (1) Rear Admiral Minoru Ota, Commander, Naval Base Force; (2) Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima, Commanding General Thirty-second Army; (3) Lieutenant General Isamu Cho, Army C/S; (4) Colonel Hiromichi Yahara, Army Senior Staff Officer. (Photograph courtesy of OCMH, DA)

North bank of the Bishi Gawa shows the typical integrated tomb-cave-dugout defenses which characterized Japanese organization of Okinawan terrain. (USA SC188743)

Since the 9th Infantry Division was no longer available to the Thirty-second Army, and in order to carry out his defensive plans, Ushijima asked for replacements. He was notified by IGHQ on 23 January 1945 that the 84th Division in Himeji would be sent to Okinawa. This notification was cancelled that same day with the explanation that the greatest possible supply of munitions would be sent, but replacements neither could nor would be sent to the army.23 This, in effect, put Ushijima on notice that the means to improve his situation had to be found locally.

In June 1944, the Thirty-second Army was to have been reinforced by Major General Shigeji Suzuki’s 44th Independent Mixed Brigade (IMB), a unit of approximately 6,000 men organized that very month on Kyushu. It was originally composed of the 1st and 2nd Infantry Units (each essentially of regimental size) and attached artillery, engineer, and signal units. While en route to Okinawa, the Toyama Maru, the ship carrying the brigade, was torpedoed by an American submarine off Amami O-Shima on 29 June. More than 5,000 men were lost and only about 600 survivors of the ill-fated brigade landed on Okinawa; these were used as the nucleus of a reconstituted 2nd Infantry Unit. Other replacements were obtained from Kyushu as well as from the ranks of conscripted Okinawans, but the reorganized unit was never fully re-equipped. As a result, this lack of basic infantry equipment caused the 2nd Infantry Unit to be known among other soldiers on the island as the Bimbo Tai or “have-nothing-unit:”24 The 1st Infantry Unit was never rebuilt and existed merely as a headquarters organization. Instead, the 15th Independent Mixed Regiment (IMR), a unit newly raised in Narashino, Chiba-ken, was flown directly to Okinawa during the period 6–11 July and added to the 44th IMB in September, bringing its strength up to about 5,000 men.

The next unit of importance to arrive was the 24th Infantry Division which landed in August. Since its initial organization as part of the Kwantung Army in October 1939, the 24th had been responsible for the security of the eastern boundaries of Manchuria. The division, commanded by Lieutenant General Tatsumi Amamiya, was well-equipped and well-trained, but not battle-proven, before it joined the Thirty-second Army. The 24th was a triangular division which had been stripped of its infantry group headquarters, one battalion from each infantry regiment, an artillery battalion, and an engineer company, all of which had been added to expeditionary units sent from Manchuria to the Central Pacific in early 1944. Until a general Thirty-second Army reorganization in February 1945, the 24th’s infantry regiments (22nd, 32nd, and 89th Infantry) functioned with only two battalions each. The division set up its headquarters at Kadena, and in October, it assigned 300 Okinawan conscripts, received from the Thirty-second Army, to each of its infantry regiments for training and retention later by the training unit. The February reorganization brought the 24th nearly up to its

original strength and made it the largest tactical unit in the Thirty-second Army, with more than 14,000 Japanese troops and Okinawan draftees assigned to infantry, artillery, reconnaissance, engineer, and transport regiments, and divisional troops.

The final major unit assigned to General Ushijima’s command was the 62nd Infantry Division, commanded by Lieutenant General Takeo Fujioka. This was a brigaded organization which had seen action in China following its activation there in June 1943. Its table of organization, considerably different from the 24th Division’s, was similar to that of like units in the Chinese Expeditionary Army. Both of the 62nd’s brigades had served as independent commands in China since 1938, while the division as a whole fought in the April–June 1944 campaigns in northern Honan Province. Each brigade had four independent infantry battalions (IIBs); the 63rd Brigade had the 11th, 12th, 13th, and 14th IIBs, while the 15th, 21st, 22nd, and 23rd IIBs were assigned to the 64th Brigade. In 1944, two additional IIBs were sent to Okinawa as reinforcements and attached on 15 December to the division which, in turn, assigned them to the brigades. The 272nd IIB went to the 64th Brigade, while the 273 IIB went to the 63rd.

The 62nd Division lacked organic artillery and had few other supporting arms. It never attained a strength greater than 12,000 troops, the largest proportion of whom were infantrymen. The infantry battalions of the 62nd were the strongest units of their type on Okinawa, as each battalion mustered a total of 1,200 men organized into five rifle companies, a machine gun company, and an infantry gun company armed with two 75-mm guns and two 70-mm howitzers. The 272nd and 273rd IIBs were reported later as having a strength of 700 men each, but with one or two less rifle companies per battalion.

Some variance in strength was found in the infantry components of the other two major fighting organizations of the Thirty-second Army. The 2nd Infantry Unit and 15th IMR of the 44th IMB had in common three rifle battalions, an antitank company (four 37-mm or 47-mm AT guns), and a regimental gun company (four 75-mm guns). Each of the battalions listed a total strength of 700 men who were assigned to three rifle companies, a machine gun company, and an infantry gun unit (two 70-mm howitzers). The 24th Division regimental organization was similar except for the replacement, in one battalion of each regiment, of the 70-mm howitzers by a mortar platoon manning four 81-mm mortars.

Since the Japanese high command envisioned the coming battle for Okinawa as developing into one of fixed position defense, the defenders were not assigned any appreciably strong armored force. The entire Japanese tank strength, given to the Thirty-second Army in July, consisted of the 27th Tank Regiment, organized originally in Manchuria in April 1944, from elements of the 2nd Armored Division. It was a regiment in name only, as one of its medium tank companies was sent to the garrison at Miyako Jima. What remained was an armored task force with a strength of 750 men who filled the ranks of one light and one medium tank company, a tractor-drawn artillery battery,

an infantry company, a maintenance company, and an engineer platoon. The regiment’s heavy weapons included 14 medium and 13 light tanks, 4 75-mm guns, 2 47-mm AT guns, and 10 machine guns. The heaviest tank-mounted weapon was the 57-mm gun on the medium tanks.

As the Japanese position in the Philippines became hopeless, shipments of weapons to be sent there were diverted by IGHQ to Okinawa. The result was that the Thirty-second Army possessed a heavier concentration of artillery power, grouped under a single command, than had been available to any Japanese force in previous Pacific campaigns. The total artillery strength on Okinawa, with the exception of the 24th Division’s organic 42nd Field Artillery Regiment, was grouped within Major General Kosuke Wada’s 5th Artillery Command. Besides the comparatively weak 7th Heavy Artillery Regiment (formerly the Nakagusuku Wan Fortress Artillery Unit), General Wada’s command included two medium regiments, a heavy battalion, and the artillery units of the 44th IMB and 27th Tank Regiment. Combat-tested at Bataan in the Philippines, the 1st Medium Artillery Regiment had one of its two battalions assigned to Miyako Jima upon arrival from Manchuria in July. The other medium regiment was the 23rd which, until its departure for Okinawa in October, had been stationed in eastern Manchuria from the time of its activation in 1942. The two medium artillery regiments together mustered a total of 2,000 troops who manned 36 150-mm howitzers. The artillery command also contained the 100th Independent Heavy Artillery Battalion. This unit was formed in June of 1944 in Yokosuka and sent to Okinawa in July with 500 men and 8 150-mm guns.

Besides artillery units, General Wada’s troop list included a mortar regiment and two light mortar battalions. The 1st Independent Heavy Mortar Regiment’s 320-mm spigot mortars were an unusual type of weapons which Marines had first encountered on Iwo Jima.25 These awesome weapons. firing a 675-pound shell dubbed a “flying ashcan” by Americans, were the basic armament of this unit. Only half of its six batteries were on Okinawa, as the other three had been sent to Burma in mid-1942. Although the 96 81-mm mortars of the 1st and 2nd Light Mortar Battalions were nominally under the command of General Wada, actually they were assigned in close support of the various infantry units and usually operated under the direction of their respective sector defense commanders.

The infantry was strengthened with other types of artillery weapons from antiaircraft artillery, antitank, and automatic weapons units which were attached to them during most of the campaign. A dual air-ground defense role was performed by the 72 75-mm guns and 54 20-mm machine cannon in 4 independent antiaircraft artillery, 3 field antiaircraft artillery, and 3 machine-cannon battalions. In addition, 48 lethal, high-velocity, flat trajectory 47-mm guns (located in 3 independent antitank battalions and 2 independent

companies) were added to the defense. Completing the infantry fire support of the Thirty-second Army were 4 independent machine gun battalions which had a total of 96 heavy machine guns.

The rest of General Ushijima’s army consisted of many diverse units and supporting elements. The departure of the 9th Division created a shortage of infantry troops which had to be made up in as expeditious a manner as possible. The reserve of potential infantry replacements on the island varied in quality from good, in the two shipping engineer regiments, to poor, at best, in the various rear area service organizations. The 19th Air Sector Command, whose airfield maintenance and construction troops were stationed at the Yontan, Kadena, and Ie Shima airstrips, provided the largest number of replacements, 7,000 men.

Another source of troops to fill infantry ranks was found in the sea-raiding units. These organizations, first encountered by American forces in the Philippines, were designed for the destruction of amphibious invasion shipping by means of explosive-laden suicide boats. There were a total of seven sea-raiding squadrons in the Okinawa Gunto, three of which were based at Kerama Retto. Each of the squadrons had assigned to it 100 hand-picked candidates for suicide and martyrdom, whose caliber was uniformly high since each man was considered officer material. When one of these men failed to return, it was presumed that his had been a successful mission and, reportedly, he was therefore given a posthumous promotion to second lieutenant.

Japanese naval base activities on Okinawa were under the command of Rear Admiral Minoru Ota. Admiral Ota was commander of the Naval Base Force for the Okinawa area, commander of the 4th Surface Escort Unit, and also was in charge of naval aviation activities in the Nansei Islands. Army-Navy relations and the chain of command on Okinawa were based locally on mutual agreements between the Thirty-second Army and the Naval Base Force.26

Admiral Ota directed the activities of approximately 10,000 men, of whom 3,500 were Japanese naval personnel and the other 6,000–7,000 were civilian employees belonging to sub-units of the Naval Base Force. Of the total number of uniformed naval troops, only about 200 were considered to have received any kind of infantry training. Upon the activation of the base force on 15 April 1944, a small number of naval officers and enlisted men, and most of the civilians, were formed into maintenance, supply, and construction units for the large airfield on Oroku Peninsula and the harbor installations at Naha. At Unten-Ko, on Motobu Peninsula in the north, were stationed a torpedo boat squadron and a midget submarine unit. In organizing for the defense of the island, the greater portion of regular naval troops were formed into antiaircraft artillery and coastal defense batteries.

These were broken down into four battery groups which were emplaced mainly in the Naha–Oroku–Tomigusuku area. The antiaircraft units manned 20 120-mm guns, 77 machine cannon, and 60 13-mm machine guns, while the 15 coast defense batteries, placed in strategic positions on the coastline under the control of Army local sector commanders, stood ready by their 14-cm and 12-cm naval guns. Although the total strength in numbers was impressive, the Okinawa Naval Base Force did not have a combat potential commensurate with its size.

Continually seeking means to bolster his defenses, General Ushijima received permission to mobilize a home guard on the island. In July 1944, the Okinawa Branch of the Imperial Reservists Association formed a home guard, whose members were called Boeitai. They were organized on a company-sized basis by town or village and were mainly comprised of reservists. Since the Boeitai represented a voluntarily organized group, it did not come under the Japanese Military Service Act, although their training and equipment came from the regular forces into whose ranks they were to be integrated when the battle was joined. The total number of Boeitai thus absorbed by the Thirty-second Army has been estimated between 17,000 and 20,000 men.

On Okinawa there were certain units which have often been confused with the Boeitai. These were the three Special Guard Companies (223rd, 224th, and 225th) and three Special Guard Engineer Units (502nd, 503rd, and 504th) which were special components of the Thirty-second Army. During peacetime, each unit had a cadre of several commissioned and noncommissioned officers, When war broke out, certain designated reservists reported to the above units to which they had been previously assigned.27

Even the youth of the island were not exempt from the mobilization. About 1,700 male students, 14 years of age and older, from Okinawa’s middle schools, were organized into volunteer youth groups called the Tekketsu (Blood and Iron for the Emperor Duty Units). These young boys were eventually assigned to front-line duties and to guerrilla-type functions for which they had been trained. Most, however, were assigned to communication units.

It has not been conclusively determined how many native Okinawans were actually added to the forces of the Thirty-second Army, or to what extent they influenced the final course of battle. What is known, however, is that their greatest contribution was the labor they performed which, in a period of nine months, transformed the island landscape into hornets’ nests of death and destruction.

The Japanese Defenses28

Continuing American successes in the conduct of amphibious operations forced the Japanese to recognize the increasing difficulties of defending against assaults from the sea. The loss

of some islands in 1944 reportedly caused Japanese garrison units at other Imperial bases in the Pacific to lose confidence in themselves and their ability to withstand an American seaborne invasion. The Japanese high command hastily published the “Essentials of Island Defense,” a document which credited Americans with overwhelming naval and air power, and emphasized that the garrisons should “lay out and equip positions which can withstand heavy naval and aerial bombardment, and which are suitable for protracted delaying action. ... diminish the fighting effectiveness of landing units ... seize opportunities to try to annihilate the force in one fell swoop.”29

This document may have influenced General Ushijima’s decisions when he settled on a final defense plan, although his particular situation was governed primarily by the strength of the Thirty-second Army and the nature of the area it was to defend. Captured on Okinawa were a set of instructions for the defense of Iwo Jima, which were apparently a blueprint also for the defense of critical areas on the coasts of the islands of Japan. It is assumed that Ushijima may have seen these instructions, for they bore directly on his problem:–

In situations where island garrisons cannot expect reinforcements of troops from rear echelons, but must carry on the battle themselves from start to finish, they should exhaust every means for securing a favorable outcome, disrupting the enemy’s plans by inflicting maximum losses on him, and, even when the situation is hopeless, holding out in strong positions for as long as possible.30

In order to deceive the assaulting forces as to Japanese intentions a Thirty-second Army battle instruction warned the troops to “guard against opening fire prematurely.”31 A later battle instruction explained that “the most effective and certain way of [the Americans’] ascertaining the existence and organization of our firepower system is to have us open fire prematurely on a powerful force where it can maneuver.”32

These instructions were a forewarning that, rather than forcing the issue on the beaches, “the Japanese soldier would dig and construct in a way and to an extent that an American soldier has never been known to do.”33 Japanese organization of the ground paralleled that which assault troops had discovered on Biak, Saipan, and Peleliu in 1944 and Iwo Jima in 1945.34 General Cho, a strong advocate of underground and cave fortifications, took an active

part in designating where defensive positions were to be placed. The most favorable terrain for the defense was occupied and honeycombed with mutually supporting gun positions and protected connecting tunnels. Natural and man-made barriers were effectively incorporated to channel attackers into prepared fire lanes and preregistered impact areas, The reverse as well as the forward slopes of hills were fortified, while artillery, mortars, and automatic weapons were emplaced in cave mouths, with their employment completely integrated within the final protective fire plan.

Each unit commander, from brigade down to company level, was made responsible for the organization of the ground and fortification of the sector assigned to him. The need for heavy construction was lessened, in some cases, by the abundance of large caves on Okinawa which required but slight reinforcement to enable them to withstand even the heaviest bombardment. Once improvements were made, these natural fortresses served either as hospitals, barracks, command posts, or all of these combined when the size of the cave permitted. There were generally two or more entrances to the caves, which sometimes had more than one level if time and manpower was available for the extensive digging necessary. Tunnels led from the caves to automatic weapons and light artillery positions which, in conjunction with the pillboxes and rifle pits in the area, dominated each defense zone. The approaches and entryway to each cave were invariably guarded by machine guns and, in addition, by covering fire from positions outside the cave.

Integrated within the whole Japanese defensive system, these cave strongholds were, in turn, centers of small unit positions. Item Pocket, one of the most vigorously defended sectors on Okinawa, was typical of the ones American forces ran into. (See Map I) The area encompassed by this position, roughly 2,500 by 4,500 yards in size, was in the vicinity of Machinato Airfield. Both the 1st Marine and 27th Infantry Divisions fought bitterly to gain it. Disposed within the caves and bunkers of the pocket was a reinforced infantry battalion which manned approximately 16 grenade launchers, 83 light machine guns, 41 heavy machine guns, 7 47-mm antitank guns, 2 81-mm mortars, 2 70-mm howitzers, and 6 75-mm guns. A minefield and an antitank trench system completed the defenses. This sector was so organized that there were no weak points visible to the attacker. Any area not swept by automatic weapons fire could be reached by either artillery or mortars. These defensive positions formed a vital link in the chain of the tough outer defenses guarding Shuri.

Based on the dictum that “the island must be divided into sectors according to the defense plan so that command will be simplified,”35 each combat element of the Thirty-second Army was assigned a sector to develop and defend as it arrived on Okinawa. By August 1944, the 44th IMB’s 2nd Infantry Unit (400 troops) under Colonel Takehiko

Udo had occupied its assigned area, Kunigami Gun (County), and had assumed responsibility for all of the island north of the Ishikawa Isthmus, and also for Ie Shima and its airfields. Upon its arrival on Okinawa, the 24th Division had begun to construct field fortifications around Yontan and Kadena airfields in an area bounded by Ishikawa Isthmus in the north and a line from Sunabe to Ozato in the south. Below the 24th’s zone of defense, the 62nd Division was unflagging in its efforts to alter the ridges, ravines, and hillsides north of Shuri. Responsibility for the entire southern portion of Okinawa below Shuri had been assumed by the 9th Division commander.

The receipt of orders in November for the transfer of the 9th Division forced a redeployment of Thirty-second Army troops and strained a defense that was already dangerously weak. The 24th Division began moving south to take over some 9th Division positions while the 44th IMB, leaving two reinforced battalions of the 2nd Infantry Unit behind on Ie Shima and Motobu Peninsula, occupied an area which reached from Kadena airfield southward to Chatan. The 62nd Division positions were likewise affected by the withdrawal of the 9th’s 14,000 combat troops, as the northern divisional boundary of the 62nd dropped to the Chatan–Futema line. In the south, the 62nd zone of responsibility was increased tremendously to include all of Naha, Shuri, Yonabaru, and the entire Chinen Peninsula.

Although the construction of fortifications, underground positions, and cave sites had been going on since the spring of 1944, the urgency of the war situation and the expectance of an imminent invasion compelled the defenders to reevaluate their plans of deployment for blunting the assault. The exact date of the new Thirty-second Army plan is not known, but a reasonable assumption is that the loss of the 9th Division in November which triggered the shuffling of units also forced a decision on a final defense plan. At the end of the month, General Ushijima and his staff pondered the following alternatives before settling on the one which they believed would guarantee the success of their mission:–

Plan I: To defend, from extensive underground positions, the Shimajiri sector, the main zone of defenses being north of Naha, Shuri, and Yonabaru. Landings north of these defenses were not to be opposed; landings south of the line would be met at the beaches. Since it was impossible to defend Kadena airfield [with available troops], 15-cm guns were to be emplaced so as to bring fire on the airfield and deny the invaders its use.

Plan II: To defend from prepared positions the central portion of the island, including the Kadena and Yontan airfields.

Plan III: To dispose one division around the Kadena area, one division in the southern end of the island, and one brigade between the two divisions. To meet the enemy wherever he lands and attempt to annihilate him on the beaches.

Plan IV: To defend the northern part of the island, with Army Headquarters at Nago, and the main line of defense based on Hill 220, northeast of Yontan airfield.36

Realistically appraising the many factors which might affect each one of the alternate plans, the Japanese settled on Plan I. Plan III was abandoned simply because the Thirty-second Army

did not have the strength adequate to realize all that the plan encompassed. Plan IV was rejected because it conceded the loss of the militarily important south even before the battle had been joined. Plan II, the one which American staff planners feared as offering the greatest threat to a successful invasion, was regretfully relinquished by the Japanese. Ushijima, recognizing his troops’ capabilities and limitations, realized that his forces, in the main, had not been trained to fight this type of delaying action which would prolong the battle, bloody the invaders, and permit the bulk of this army to withdraw to the more heavily fortified southern portion of Okinawa. Yet, in effect, this is exactly the strategy he was forced to employ after the initial American landings.

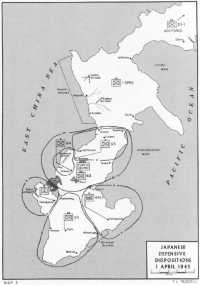

Placing Plan I into effect, the Japanese centered the main battle position in the Shuri area, where the rugged terrain surrounding the ancient capital was developed with the strongest installations oriented north toward the Hagushi beaches. (See Map 3.) The Hagushi region, coincidentally, evolved as a secondary target to the Japanese and a primary target to American staff planners. In addition, “handicapped by their lack of ability to make a logistics estimate for a landing operation,”37 the Japanese believed that the major effort would be made in the southeast with an assault across the Minatogawa beaches. overlooking both the Minatogawa and Nakagusuku Wan beaches, Chinen Peninsula heights presented the defenders with the most favorable terrain of its type on Okinawa and, as such, it was hoped that the invaders could be met and defeated here. Since, form the standpoint of actual manpower, the Chinen sector was the weakest area in the final defense plan, a goodly portion of the artillery and infantry strength of the Thirty-second Army—which could have been better employed in reinforcing Shuri positions—was diverted to the peninsula, remaining there out of action during the first weeks of the campaign.38

Among Ushijima’s most pressing needs were additional troops and time in which to train them. Extra time was needed also to provide for expanding and strengthening existing fortifications as well as the communications net. With the exception of a drastic fuel shortage, the army was in good logistical shape. Although the Thirty-second Army itself had no provisions in reserve, enough had been distributed to subordinate units, and stored by them in caves near troop dispositions, to last until September 1945. This system was satisfactory in that the strain on the overworked transportation facilities was removed, but when an area was overrun by Americans and the Japanese were

Map 3: Japanese Defensive Dispositions, 1 April 1945

forced to withdraw, the supplies were lost.

Unable to halt the inexorable press of time, General Ushijima now found it imperative to beef-up his infantry component from sources on the island, for he knew that he could expect no outside help. In addition to the mobilized Boeitai and a continuing stream of Okinawan conscriptees, the Japanese commander attempted to free his uniformed labor and service personnel for frontline duty by replacing them with able-bodied males from the large population of the island. In February 1945, more than 39,000 Okinawans were assigned to Japanese Army units on the island. The natives were placed into such categories as Main Labor (22,383), Auxiliary Labor (14,415), and Student Labor (2,944).39 The Japanese attempted to evacuate to the northern part of the island all of the rest of the population who were incapable of aiding the war effort or who were potential obstacles in the battle zone.40

General Ushijima found the additional infantry troops he required in the ranks of Thirty-second Army special and service units. The first elements affected by an army-wide reorganization at this time were seven sea-raiding base battalions. Each suicide squadron was supported by a base battalion of 900 men, and since they had completed their basic assignment of cave and suicide boat site construction, the army decided to utilize these men in an area where they were critically needed. Beginning 13 February 1945, these battalions, although retaining their original numerical designations, were reassigned as the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 26th, 27th, 28th, and 29th Independent Battalions (each averaging about 600 men) to the 24th and 44th IMB for thorough training and subsequent absorption.41 Only the maintenance company of each battalion was to remain with its respective sea-raiding suicide unit. In comparison with the regular infantry of the Japanese Army, the new battalions were poorly trained and equipped, but these 4,500–5,000 men invested enemy forces with an additional source of strength.

During the next month, March, a final army reorganization took place, at which time the Thirty-second Army directed “the various shipping, air, and rear echelon forces [to] set up organizations and dispositions for land combat.”42 Besides their basic missions, these units now had to give infantry training and field fortification construction priority in their schedules. The March reorganization supplied the army with two brigades and a regiment which appeared more significant on paper than actually was the case. These lightly equipped and untrained service troops could serve only as combat replacements with slight tactical value.

Units from the 19th Air Sector Headquarters were funneled into the 1st Specially Established Regiment which, under 62nd Division control, was responsible for the defense of the areas in the vicinity of Kadena and Yontan airfields. Support positions in the Naha–Yonabaru valley were assumed by the 1st Specially Established Brigade, composed of three regiments and formed from Thirty-second Army transport, ordnance, construction, and supply troops formerly within the 49th Line of Communications Headquarters command. A 2nd Specially Established Brigade of three regiments, culled from the 11th Shipping Group Headquarter’s shipping, sea transport, and engineer rosters, was deployed in support of the 24th Division mission—the defense of southernmost Okinawa. “Army rear echelon agencies not included in this order and their personnel will be under command of the front line unit in the vicinity where their duties are carried on, and will reinforce it in combat,” stated the all-inclusive 21 March order which put the entire Thirty-second Army in a status of general mobilization for combat.43

By 26 March, Okinawa Base Force naval and civilian personnel had been formed into the same type of jerry-built, poorly equipped, and undertrained defense units as had been the service troops of the Thirty-second Army. On Oroku Peninsula, naval lieutenants commanded those units designated as battalions while lieutenants (junior grade) became company commanders. Admiral Ota’s 13-mm and 25-mm antiaircraft batteries were re-equipped and transformed into an 81-mm mortar battery and two independent machine gun battalions and, thus armed, were the only adequately weaponed units in the naval garrison.

In less than two months after the first reorganization order had been published, General Ushijima had nearly doubled the potential combat strength of his army by the addition of approximately 20,000 Boeitai, naval, and service troops. Hurriedly, the concerted efforts of this determined Japanese force converted the Shuri area into what was to be an almost impregnable bastion, for the final defensive plan was strengthened by the defenders’ determination to hold Shuri to the last man.

Concurrent with the February army reorganization, the troops were deployed in their final positions. General Ushijima’s main battle force was withdrawn to an outpost zone just north of Futema, while elements of the 1st Specially Established Regiment were loosely disposed in the area immediately behind the Hagushi beaches. Although this was the least likely place where the Americans were expected to land, the Japanese troops defending this area were to fight a delaying action in any such eventuality, and then, after destroying the Yontan and Kadena airfields, were to beat a hasty retreat to the Shuri lines.

In the suspected invasion area, the Minatogawa beaches, the bulk of the Japanese infantry and artillery forces were positioned to oppose the landings. The 5th Artillery Command observation post was established near Itokazu in control of all of its major components, which had been emplaced in defense of

the Minatogawa sector. Since landings further north on Chinen Peninsula would give the invaders a relatively unopposed, direct route into the heart of the major Japanese defense system, the 44th IMB was assigned control of the rugged heights of the peninsula. The 24th Division, taking over the defense works begun by the 9th Division, occupied the southern portion of Okinawa from Kiyan Point to an area just north of Tsukasan. The whole of Oroku Peninsula was assigned to Admiral Ota’s forces, who were prepared to fight the “Navy Way,” contesting the invasion at the beaches in a manner reminiscent of the Japanese defense of Tarawa.44

Since the heart and soul of the Japanese defenses were located at Shuri, the most valuable and only battle-tested organization on the island, the 62nd Division, was charged with the protection of this vital area. The Japanese had shrewdly and industriously constructed a stronghold centered in a series of concentric rings, each of which bristled with well dug-in, expertly sited weapons. Regardless of where the Americans landed, either at Hagushi or Minatogawa or both, the plans called for delaying actions and, finally, a withdrawal into the hard shell of these well-disguised positions.

The isolated north was defended by the Udo Force, so-called after its leader and commanding officer of the 2nd Infantry Unit—Colonel Takehiko Udo. Its mission was twofold, defense of both Motobu Peninsula and Ie Shima. The reinforced battalion on Ie Shima was assigned secondary missions of destroying the island’s airfield and assisting in the transfer of aviation matériel to the main island. Upon completion of these duties, the unit was then to return to Okinawa where it would be assigned to the control of the 62nd Division. Udo’s battalion on Motobu Peninsula, in expectation of an invasion of Ie Shima followed by a landing on the peninsula, was disposed with its few artillery pieces so placed as to make its positions and positions on Ie Shima mutually supporting. As a result of its detachment earlier from the larger portion of the Thirty-second Army, Udo’s command was destined to fulfill a hopeless undertaking to the very end.

Air defense was not included in the Thirty-second Army plan, nor was any great aviation force available to Ushijima. He had expected that approximately 300 airplanes would be sent to Okinawa, but feared that their projected time of arrival, April, would be too late to influence the local situation. The American preinvasion air and naval bombardments in March, combined with planned Japanese destruction efforts, had rendered the Ie Shima, Yontan, Kadena, and Oroku airfields unusable.

The army did expect, however, that its exertions would be complemented by

the combat activity of its organic suicide sea units. The sea-raiding squadrons located at positions in Kerama Retto and along the Okinawa coast, would “blast to pieces the enemy transport groups with a whirlwind attack in the vicinity of their anchorages.”45 Unfortunately for the Japanese, their midget submarines and motor torpedo boats at Unten–Ko could not join this offensive endeavor, for, by the day of the American invasion, they had all been destroyed by American carrier strikes or scattered in the aftermath of an unsuccessful attack on the destroyer Tolman of Task Force 52.46

The significance of Thirty-second Army deployments and redeployments, the frenzied last-minute preparations, and the general air of expectancy were not lost upon even the lowest ranks. One private wrote as early as February, “it appears that the army has finally decided to wage a decisive battle on Okinawa.”47 Another soldier noted that “it’s like a frog meeting a snake, just waiting for the snake to eat him.”48

Between 20 and 23 March 1945, the Japanese command on Okinawa made an even more realistic estimate than had the troops of what the future held for the garrison. The Japanese reacted to news of a conference held in Washington between Admirals King and Nimitz in early March by placing a general alert into effect “for the end of March and early April,” since statistics demonstrated “that new operations occur from 20 days to one month after [American] conferences on strategy are held.”49 This estimate of when the Americans were expected was reduced three days after its publication following receipt of reports of increased shipping in the Marianas, and when repeated submarine sightings and contacts were made. All of this enabled the Japanese intelligence officers to predict without hesitation that the target was to be “Formosa or the Nansei Shoto, especially Okinawa.”50