Chapter 8: Reduction of the Shuri Bastion

As conceived in Tenth Army plans, the object of the full-scale attack beginning on 11 May was to destroy the defenses guarding Shuri. In the end, this massive assault took the lives of thousands of men in two weeks of the bloodiest fighting experienced during the entire Okinawa campaign. For each frontline division, the struggle to overcome enemy troops on the major terrain feature in the path of its advance determined the nature of its battle. Facing the front of the 96th Infantry Division was Conical Hill; the 77th Division fought for Shuri itself. Marines of the 1st Division had to overcome Wana Draw, while Sugar Loaf Hill was the objective of the 6th Marine Division. (See Map V)

Battle For Sugar Loaf Hill1

Sugar Loaf Hill was but one of three enemy positions in a triangularly shaped group of hills which made up the western anchor of the Japanese Shuri defense system. Sugar Loaf was the apex of the triangle, which faced north, its flanks and rear well covered by extensive cave and tunnel positions in Half Moon Hill to the southeast and the Horseshoe to the southwest. The three elements of this system were mutually supporting. In analyzing these defenses, the 6th Marine Division pointed out that:–

... the sharp depression included within the Horseshoe afforded mortar positions that were almost inaccessible to any arm short of direct, aimed rifle fire and hand grenades. Any attempt to capture Sugar Loaf by flanking action from east or west is immediately exposed to flat trajectory fire from both of the supporting terrain features. Likewise, an attempt to reduce either the Horseshoe or the Half Moon would be exposed to destructive well-aimed fire from the Sugar Loaf itself. In addition, the three localities are connected by a network of tunnels and galleries, facilitating the covered movement of reserves. As a final factor in the strength of the position it will be seen that all sides of Sugar Loaf Hill are precipitous, and there are no evident avenues of approach into the hill mass. For strategic location and tactical strength it is hard to conceive of a more powerful position than the Sugar Loaf terrain afforded. Added to all the foregoing was the bitter fact that troops assaulting this position presented a clear target to enemy machine guns, mortars, and artillery emplaced on the Shuri heights to their left and left rear.2

Following its successful charge to seize the crest of Sugar Loaf, Major Courtney’s small group had dug in. An unceasing enemy bombardment of the newly won position, as well as the first in a series of Japanese counterattacks to regain it, began almost immediately. At midnight, 14–15 May, there were sounds of enemy activity coming from the other

side of the crest, signifying an impending banzai charge to Courtney. He forestalled the charge by leading a grenade-throwing attack against the reverse slope defenders, in the course of which he was killed.

At 0230, only a handful of tired and wounded Marines remained on the top of Sugar Loaf, and Lieutenant Colonel Woodhouse ordered his reserve, Company K, to reinforce the depleted group. With the coming of dawn, the forces on Sugar Loaf had been reduced again by enemy action and fire, while 2/22 itself had been hit by numerous Japanese counterattacks and attempts at infiltration all along the battalion lines. At 0630, Company D of 2/29 was attached to the 22nd Marines to help mop up the enemy in the rear of 2/22.

There were less than 25 Marines of Courtney’s group and Company K remaining in the 2/22 position on Sugar Loaf when daylight came; at 0800, the seven survivors of the Courtney group were ordered off the hill by the battalion commander. Within a short time thereafter, the enemy launched another attack against the battered position. During the height of this attack, a reinforced platoon of Company D arrived on the hilltop and was thrown into the battle. Suffering heavy casualties while en route to the position, the Company D platoon was hit even harder by the charging Japanese as soon as it arrived at the top of the hill. At 1136, the few survivors of Company K and the 11 Marines remaining of the Company D platoon were withdrawn from Sugar Loaf. The Company D men rejoined their parent unit, which was manning a hastily constructed defensive line organized on the high ground just in front of Sugar Loaf.

The enemy counterattack was the beginning of a series which soon reached battalion-sized proportions, and which, by 0900, had spread over a 900-yard front extending into the zones of 1/22 and 3/29. An intensive naval gunfire, air, and artillery preparation for the division assault that morning temporarily halted the enemy attack, but it soon regained momentum. By 1315, however, the Japanese effort was spent, though not before the 22nd Marines in the center of the division line had taken a terrific pounding. In an incessant mortar and artillery bombardment supporting the enemy counterattack, the battalion commander of 1/22, Major Thomas J. Myers, was killed, and all of his infantry company commanders—and the commander and executive officer of the tank company supporting the battalion—were wounded when the battalion observation post was hit.3

Major Earl J. Cook, 1/22 executive officer, immediately took over and reorganized the battalion. He sent Companies A and B to seize a hill forward of the battalion left flank. When in blocking positions on their objective—northwest of Sugar Loaf—the Marines could effectively blunt counterattacks expected to be mounted in this area. Because the possibility existed of a breakthrough in the zone of 2/22, the regimental commander moved Company

Sugar Loaf Hill, western anchor of the Shuri defenses, seen from the north. (USMC 124983)

Tanks evacuate the wounded as the 29th Marines continue the attack on Sugar Loaf. (USMC 122421)

I of 3/22 into position to back up the 2nd Battalion. At 1220, Lieutenant Colonel Woodhouse was notified that his exhausted battalion would be relieved by 3/22 as soon as possible, and would in turn take up the old 3rd Battalion positions on the west coast along the banks of the Asato. The relief was effected at 1700 with Companies I and L placed on the front line, and Company K positioned slightly to the right rear of the other two. Company D, 2/29, reverted to parent control at this time.

During the ground fighting on the night of 14–15 May, naval support craft smashed an attempted Japanese landing in the 6th Division zone on the coast just north of the Asato Gawa. Foreseeing the possibility of future raids here, General Shepherd decided to strengthen his beach defenses. In addition to a 50-man augmentation from the regiment, 2/22 was also reinforced by the 6th Reconnaissance Company to bolster its night defenses. To further strengthen Lieutenant Colonel Woodhouse’s command, he was given operational control of 2/4, which was still in corps reserve.

The objective of the 29th Marines on 15 May was the seizure of Half Moon Hill. The 1st and 3rd Battalions encountered the same bitter and costly resistance in the fight throughout the day that marked the experience of the 22nd Marines. A slow-paced advance was made under constant harassing fire form the Shuri Heights area. By later afternoon, 1/29 had reached the valley north of Half Moon and became engaged in a grenade duel with enemy defenders in reverse slope positions. Tanks supporting the Marine assault elements came under direct 150-mm howitzer fire at this point. Several of the tanks were hit, but little damage resulted. At the end of the day, the lines of the 29th Marines were firmly linked with the 22nd Marines on the right and the 1st Division on the left.

Facing the 6th Marine Division was the 15th Independent Mixed Regiment, whose ranks were now sadly depleted as a result of its unsuccessful counterattack and because of the advances of 1/22 and the 29th Marines. More than 585 Japanese dead were counted in the division zone, and it was estimated that an additional 446 of the enemy had been killed in the bombardments of supporting arms or sealed in caves during mopping-up operations.4 Expecting that the Americans would make an intensive effort to destroy his Sugar Loaf defenses, General Ushijima reinforced the 15th IMR with a makeshift infantry battalion comprised of service and support units from the 1st Specially Established Brigade.5

The success of the 6th Division attack plan for 16 May depended upon the seizure of Half Moon Hill by the 29th Marines. (See Map VI) Once 3/29 had seized the high ground east of Sugar Loaf, 3/22 was to make the major division effort and capture the hill fortress. Immediately after the attack was launched, assault elements on the regimental left flank encountered heavy fire and bitter opposition from enemy strongpoints guarding the objective. The 1st Battalion was spearheaded by a Company B platoon and its supporting armor. After the tank-infantry

teams had passed through the right flank to clear the reverse slope of the ridge held by Company C, devastating small arms, artillery, mortar, and antitank fire forced them to withdraw. The fury of this fire prevented Company C from advancing over the crest of the ridge and the other two platoons of Company B from moving more than 300 yards along the division boundary before they too were stopped by savage frontal and flanking fire.

The night defenses of the battalion remained virtually the same as the night before; however, the units were reorganized somewhat and their dispositions readjusted. At 1400 that afternoon, Lieutenant Colonel Jean W. Moreau, commander of 1/29, was evacuated after he was seriously wounded by an artillery shell which hit his battalion OP; Major Robert P. Neuffer assumed command.

Continuously exposed to heavy enemy artillery and mortar bombardment, 3/29 spent most of the morning moving into favorable positions for the attack on Half Moon. Following an intensive artillery and mortar preparation, tanks from Companies A and B of the 6th Tank Battalion emerged from the railroad cut northeast of Sugar Loaf and lumbered into the broad valley leading to Half Moon. While Company A tanks provided Company B with direct fire support from the slopes of hills just north of Sugar Loaf, the latter fired into reverse slope positions in the ridge opposite 1/29, and then directly supported the assault elements of the 3rd Battalion.

At about the same time that their armor support appeared on the scene, Companies G and I attacked and quickly raced to and occupied the northern slope of Half Moon Hill against slight resistance. The picture changed drastically at 1500, however, when the Japanese launched a violent counteroffensive to push the Marines off these advanced positions even while they were attempting to dig in. The enemy poured machine gun, rifle, and mortar fire into the exposed flanks and rear of the Americans, who also were hit by a flurry of grenades thrown from caves and emplacements on the south, or reverse, slope of the hill. As evening approached, increasing intense enemy fire penetrated the smoke screen covering the digging-in operations of the troops and they were ordered to withdraw to their earlier jump-off positions to set in a night defense.

On the right of the division, when the 22nd Marines attack was launched at 0830 on the 16th, assault elements of the 1st Battalion were immediately taken under continuous automatic weapons fire coming from the northern edge of the ruins of the town of Takamotoji, just as they were attempting to get into position to support the attack of 3/22. The fact that this previously quiet area now presented a bristling defense indicated that the Japanese had reinforced this sector to confound any American attempt to outflank Sugar Loaf from the direction of Naha. In the end, because of the criss-crossing fires coming from the village, Half Moon Hill, and the objective itself, the 3rd Battalion was unable to fulfill its assignment.

The battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Malcolm “O” Donohoo, had planned to attack Sugar Loaf from the east once the flank of the attacking unit, Company I, was safeguarded by a successful 3/29 advance. Company L, 3/22,

was to support the attack by covering the south and east slopes of Sugar Loaf with fire, while 1/22, in turn, would take the high ground west of Sugar Loaf, where it would support the Company L movement by fire. The success or failure of the attack on the hill hinged on the success or failure of 3/29.

At 1500, despite the fact that 3/29 had not fully occupied the high ground, Company I moved out with its tank support and reached Sugar Loaf without serious opposition. Once the troops in the van attempted to gain the crest, however, they began receiving heavy enemy mortar and machine gun fire. In an effort to suppress this fire, the tanks began flanking the hill, but ran into a minefield where one tank was lost. Company I, nevertheless, gained the top of the hill at 1710 and began digging in. The situation was in doubt now, because both 1/22 and Company L were pinned down and 3/29 was forced to withdraw from Half Moon. Company I, therefore, was in an exposed position and its precarious hold on Sugar Loaf had become untenable. With both flanks exposed and its ranks depleted by numerous casualties, the company had to be pulled back from the hill under the cover of tire of both division and corps artillery. As 3/22 reorganized for night defense, enemy batteries bombarding the Marine lines wounded Lieutenant Colonel Donohoo, who was replaced by Major George B. Kantner, the battalion executive officer.

This day was categorized by the 6th Division as the “bitterest” of the Okinawa campaign, a day when “the regiments had attacked with all the effort at their command and had been unsuccessful.”6 One infantry regiment, the 22nd, had been so sorely punished that, in assessing his losses for the day, Colonel Schneider reported that the combat efficiency of his unit was down to 40 percent.7 Because the fighting of the preceding eight days had sapped the offensive capabilities of the 22nd Marines and reduced the regiment to a point where its continued employment was inadvisable, it became apparent that the 29th Marines would have to assume the burden of taking Sugar Loaf. On 17 May, the regimental boundary was shifted west to include the redoubt in its zone and thereby lessen control problems in the attacks on both it and Half Moon.

In an effort to neutralize the seemingly impregnable Japanese defenses here, the attack of 17 May was preceded by an intensive bombardment of 29th Marines objectives by all available supporting arms. In this massive preparation were the destructive fires of 16-inch naval guns, 8-inch howitzers, and 1,000-pound bombs. Following this softening up, and spearheaded by a heavy and continual artillery barrage, the 29th Marines launched a tank-infantry attack with three battalions abreast. The 1st and 3rd Battalions on the left had the mission of taking Half Moon, while 2/29, with Company E in assault, was to take Sugar Loaf.

Company E made three attempts to take its objective, and each proved costly and unsuccessful. The first effort, involving a wide flanking movement in which the railroad cut was utilized for cover, was stymied almost immediately when the troops surged onto open

ground. A close flanking attack around the left of the hill characterized the second effort, but the steep southeastern face of the height precluded a successful climb to the top. The axis of the attack was then reoriented to the northeast slope of Sugar Loaf, and the lead platoon began a difficult trek to the top, all the while under heavy mortar fire coming from covered positions on Half Moon. Three times the assaulting Marines reached the crest, only to be driven off by a combination of grenades and bayonet charges. Almost all fighting was at close range and hand-to-hand.

After quickly reorganizing for a fourth try, the now-fatigued and depleted company drove to the hilltop at 1830, when it was met again by a determined Japanese counterattack. This time, however, the Marines held, but heavy casualties and depleted ammunition supply forced the battalion commander to withdraw the survivors of the company from Sugar Loaf. Thus, the prize for which 160 men of Company E had been killed and wounded on that day fell forfeit to the Japanese. Some small sense of just retribution was felt by Company E Marines when the enemy foolishly and boldly attempted to reinforce Sugar Loaf at dusk by moving his troops to the hill along an uncovered route. Artillery observers immediately called down the fire of 12 battalions on the unprotected Japanese, decisively ending their reinforcement threat.

So well integrated were the enemy defenses on Half Moon and Sugar Loaf, capture of only one portion was meaningless; 6th Division Marines had to take them all simultaneously. If only one hill was seized without the others being neutralized or likewise captured, effective Japanese fire from the uncaptured position would force the Marines to withdraw from all. This, in effect, was why Sugar Loaf had not been breached before this, and why it was not taken on the 17th.

A combination of tank fire, flame, and demolitions had temporarily subdued the Japanese opposing the 1/29 approach on the 17th and enabled Companies A and C to advance swiftly across the valley and up the forward slopes of Half Moon. While Company C mopped up remaining enemy defenders, Company A renewed its attack across the valley floor and raced to the forward slopes of Half Moon. When Company B attempted to cross open ground to extend the battalion lines on the left, it was stopped cold by accurate fire coming from the hill, Sugar Loaf, and Shuri. At this time, the positions held by the exposed platoons of Company A became untenable. The battalion commander authorized their withdrawal to a defiladed area approximately 150 yards forward of their line of departure that morning.

By 1600, 3rd Battalion companies had fought their way to Half Moon under continuous fire and begun digging in on the forward slope of the hill. They were not able to tie in with 1,/29 until 1840, two hours after Company F had been ordered forward to fill in the gap between the battalions. Following a crushing bombardment of these hastily established positions on Half Moon and the exposure of the right flank of 3/29 to direct and accurate fire from enemy-held Sugar Loaf, the entire battalion

was pulled back when Company A was withdrawn from its left. Strong positions were established for night defense—only 150 yards short of Half Moon. The gaps on either side of 3/29 were protected by interlocking lanes of fire established in coordination with 1/29 on its left flank and 2/29 on its right. On 18 May at 0946, less than an hour after the 29th Marines attacked, Sugar Loaf was again occupied by 6th Division troops. (See Map VII) The assault began with tanks attempting a double envelopment of this key position with little initial success. A combination of deadly AT fire and well-placed minefield quickly disabled six tanks. Despite this setback and increasingly accurate artillery fire, a company of medium tanks split up and managed to reach and occupy positions on either flank of Sugar Loaf, from which they could cover the reverse slopes of the hill.

In a tank-infantry assault, Company D, 2/29, gained the top of the heretofore- untenable position, and held it during a fierce grenade and mortar duel with the defenders. Almost immediately after subduing the enemy, the company charged over the crest of the hill and down its south slope to mop up and destroy emplacements there. Disregarding lethal mortar fire from Half Moon that blanketed Sugar Loaf, Company D dug in at 1300 as well as it could to consolidate and organize its newly won conquest.

All during the attempts to take Sugar Loaf and Half Moon, the enemy on Horseshoe Hill had poured down never-ending mortar and machine gun fire on the attacking Marines below. To destroy these positions, Company F was committed on the battalion right. Supported by fire from 1/22 on its right and Marines on Sugar Loaf, the company pressed forward to the ridge marking the lip of the Horseshoe ravine. Here it was stopped by a vicious grenade and mortar barrage coming from the deeply entrenched enemy. Because of this intense resistance, the company was forced to withdraw slightly to the forward slope of the ridge, where it established a strong night defense.

Implicit in the 6th Marine Division drive towards the Asato Gawa was a threatened breakthrough at Naha. To forestall this, General Ushijima moved four naval battalions to back up the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade. Few men in the rag-tag naval units were trained for land combat, much less combat at all, since the battalions were comprised of inexperienced service troops, civilian workers, and Okinawans who had been attached to Admiral Ota’s Naval Base Force. The commander of the Thirty-second Army thought that the lack of training could be compensated in part by strongly arming the men with a generous allotment of automatic weapons taken from supply dumps on Oroku and the wrecked aircraft that dotted the peninsula’s airfield.8

Despite their lack of combat experience, the naval force was to perform a three-fold mission with these weapons: back up the Sugar Loaf defense system, hold the hills northwest of the Kokuba River, and maintain the security of Shuri’s western flank in the event that the defenses of the 44th IMB collapsed. The furious Japanese defense of the buffer zone stretching from the Naha estuary of the Kokuba to the western outskirts of the town of Shuri indicated their concern with the threat to the left flank of the Shuri positions.9

The coming of darkness on 18 May was not accompanied by any noticeable waning in the furious contest for possession of Sugar Loaf, a battle in which the combat efficiency of the 29th Marines had been so severely tested and drained. In the nearly nine days since the Tenth Army had first begun its major push, the 6th Marine Division had sustained 2,662 battle and 1,289 nonbattle casualties,10 almost all in the ranks of the 22nd and 29th Marines. It was patently obvious that an infusion of fresh blood into the division lines was a prerequisite for the attack to be continued with undiminished fervor. Accepting this fact, General Geiger released the 4th Marines to parent control effective at 0800 on 19 May, at which time General Shepherd placed the 29th Marines in division reserve, but subject to IIIAC control.

At 0300 on the morning of the scheduled relief, a strong Japanese counterattack hit the open right flank of Company F, 2/29, poised just below the lip of the Horseshoe depression. The fury of the enemy attack, combined with an excellently employed and heavy bombardment of white phosphorous shells, eventually forced the advance elements of Company F to withdraw to the northern slope of Sugar Loaf.11 At first light, relief of the three exhausted battalions of the 29th began, with 2/4 taking up positions on the left, 3/4 on the right.

Despite the difficult terrain, constant bombardment of the lines, and opposition from isolated enemy groups which had infiltrated the positions during the night, the relief was effected at 1430 at a cost to the 4th Marines of over 70 casualties—primarily from mortar and artillery fire. At approximately 1530, a counterattack was launched against 2/4, which then was in a precarious position on Half Moon Hill, on the division left flank. After nearly two hours of fighting, the attack was broken up. The advance Marine company was then withdrawn from its exposed point to an area about 150 yards to the rear, where the battalion could reinforce the regimental line after tying in with 3/5 and 3/4.

The area from which the attack had been launched against Company F, 2/29, was partially neutralized during the day by the 22nd Marines. Under its new commander,

Colonel Harold C. Roberts,12 the regiment pushed its left flank forward 100–150 yards to the high ground on the left of Horseshoe. Disregarding heavy artillery and mortar fire as well as they could, the Marines dug in new positions which materially strengthened the division line.

After a night of this heavy and accurate enemy bombardment, the two assault battalions of the 4th Marines jumped off at 0800 on 20 May. Preceded by a thorough artillery preparation and supported by the 6th Tank Battalion, the 5th Provisional Rocket Detachment, and the Army 91st Chemical Mortar Company, the Marines moved rapidly ahead for 200 yards before they were slowed and then halted. The determined refusal of the Japanese infantry entrenched on Half Moon and Horseshoe Hills to yield, and fierce machine gun and artillery fire from hidden positions in the Shuri Hill mass, where enemy gunners could directly observe the Marine attack, blocked the advance.

It soon appeared as though the fight for Half Moon was going to duplicate the struggle for Sugar Loaf. To reinforce the 2/4 assault forces and to maintain contact with the 5th Marines, Lieutenant Colonel Reynolds H. Hayden, commander of 2/4, committed his reserve rifle company on the left at 1000. In face of a mounting casualty toll, at 1130 he decided to reorient the axis of the battalion attack to hit the flanks of the objective rather than its front. While the company in the center of the battalion line remained in position and supported the attack by fire, the flank companies were to attempt an armor-supported double envelopment. At 1245, when coordination for this maneuver was completed, the attack was renewed.

Company G, on the right, moved out smartly, and, following closely behind the neutralizing fires of its supporting tanks, it seized and held the western end of Half Moon. While traversing more exposed terrain and receiving fire from three sides, the left wing of the envelopment—Company E—progressed slowly and suffered heavy casualties. Although subjected to a constant barrage of mortars and hand grenades, the company reached the forward slope of its portion of the objective, where it eventually dug in for the night. The night positions of 2/4 were uncomfortably close to those of the Japanese, and separated only by a killing zone along a hill crest swept by both enemy and friendly fire. Nonetheless, the battalion had made fairly substantial gains during the day and it was set in solidly.

Earlier that day, as 3/4 attacked enemy positions on the high ground forming the western end of Horseshoe, it had received fire support from the 22nd Marines. The 4th Marines battalion employed demolitions, flamethrowers, and tanks to burn and blast the honeycomb of Japanese-occupied caves in the forward (north) slope of Horseshoe Hill. When the regiment halted the attack for the day at 1600, 3/4 had gained its objective. Here, the battalion was on high ground overlooking the

Horseshoe depression where the Japanese mortars, which had caused so many casualties that day, were dug in.

To maintain contact with 2/4 and to strengthen his line, Lieutenant Colonel Bruno A. Hochmuth, 3/4 commander, had committed elements of his reserve, Company I, shortly after noon. Anticipating that a counterattack might possibly be mounted against 3/4 later that evening, Colonel Shapley ordered 1/4 to detail a company to back up the newly won positions on Horseshoe. Company B was designated and immediately briefed on the situation of 3/4, routes of approach, and courses of action to be followed if the Japanese attack was launched.

The sporadic mortar and artillery fire that had harassed 4th Marines lines suddenly increased at 2200, when bursts of white phosphorous shells and colored smoke heralded the beginning of the anticipated counterattack. An estimated 700 Japanese struck the positions of Companies K and L of 3/4. As soon as the enemy had showed themselves, they were blasted by the combined destructive force of prepared concentrations fired by six artillery battalions.13 Gunfire support ships provided constant illumination over the battlefield. Company B was committed to the fight and “with perfect timing,”14 moved into the line to help blunt the attack.

Star shells and flares gave a surrealistic cast to the wild two-and-a-half hour fracas, fought at close quarters and often hand-to-hand. The fight was over at midnight; the few enemy who had managed to penetrate the Marine lines were either dead or attempting to withdraw. The next morning, unit identification of some of the nearly 500 Japanese dead revealed that fresh units—which included some naval troops—had made the attack. The determination of the attackers to crush the Americans reemphasized the extremely sensitive and immediate Japanese reaction to any American threat against Shuri’s western flank.

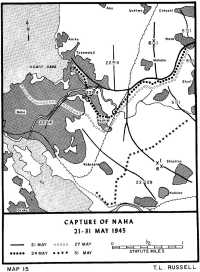

On 21 May, the main effort of the 6th Division attack was made by the 4th Marines, with the 22nd Marines pacing the attack and giving fire support. The objective was the Asato River line. (See Map 15.) Under its new commander, Lieutenant Colonel George B. Bell, 1/4 attacked in the center of the line.15 Forward progress down the southern slopes of Sugar Loaf towards the easternmost limit of Horseshoe was slowed by both bitter fighting and the

Map 15: Capture of Naha, 21–31 May 1945

rain that fell during the morning and most of the afternoon. This downpour turned the shell-torn slopes into slick mud-chutes, making supply and evacuation over the treacherous footing almost impossible. But the fresh battalion overcame the combination of obstacles placed in its way by the weather, terrain, and numerous remaining enemy pockets all along the river front, to advance 200 yards.

Demolition and flamethrower teams blasted and burned the way in front of 3/4 as it drove into the extensive and well-prepared enemy positions in the interior of Horseshoe. By midafternoon, Companies K and L had destroyed the deadly mortars emplaced there, and were solidly positioned in a defense line that extended approximately halfway between Horseshoe Hill and the Asato Gawa.

Intensive mortar and artillery fire from the heights of Shuri combined with the rugged terrain within the 2/4 zone of action restricted the use of tanks and prevented that battalion from advancing appreciably on 21 May. After five days of furious fighting and limited gains in the Half Moon area, General Shepherd concluded that the bulk of enemy firepower preventing his division from retaining this ground was centered in the Shuri area, outside of the division zone of action.

Thoroughly estimating the situation, he decided to establish a strong reverse slope defense on the division left, to concentrate the efforts of the division on a penetration in the south and southwest, and to make no further attempts at driving to the southeast, where his troops had been meeting withering fire from Shuri. The division commander believed that this new maneuver would both relieve his forces of a threat to their left flank and at the same time give impetus to a drive to envelop Shuri from the west.

The sporadic rain which fell on the 21st, came down even more heavily and steadily that night. Resupply of assault elements and replenishment of forward supply dumps proved almost impossible. The unceasing deluge made southern Okinawa overnight a veritable mudhole and a greater obstacle to all movement than the unrelenting enemy resistance.

The Battle For Wana Draw16

When the 1st Marine Division smashed the Japanese outpost line at Dakeshi, the battleground for General del Valle’s Marines shifted to the foreboding Wana approaches to the Shuri hill mass. (See Map 14.) All evidence now signified that the main Japanese defenses in southern Okinawa consisted of a nearly regular series of concentric rings whose epicenter was protected by some of the most rugged terrain yet encountered in the drive south. The mission of breaching the Wana defenses fell to the 1st Marine and 77th Infantry Divisions at the same time that the 6th Marine and 96th Infantry Divisions attempted to envelop enemy flanks.

A somewhat crude Japanese propaganda attempt appeared in a leaflet discovered on the body of an infiltrator in the rear of the 1st Division on 14

May. Purportedly a letter from a wounded 96th Division soldier in enemy hands, it warned in fractured English that:–

... the battles here will be 90 times as severe as that of Yusima Island [Iwo Jima]. I am sure that all of you that have landed will lose your lives which will be realized if you come here. The affairs of Okinawa is quite different from the islands that were taken by the Americans.17

An analysis made of the Wana positions after the battle showed that the Japanese had “taken advantage of every feature of a terrain so difficult it could not have been better designed if the enemy himself had the power to do so.”18 Utilizing every defense feature provided by nature, General Ushijima had so well organized the area that an assault force attacking to the south would be unable to bypass the main line of resistance guarding Shuri, and would instead have to penetrate directly into the center of the heretofore unassailable defenses of the Thirty-second Army.

The terrain within and immediately bordering the division zone was both varied and complex. The southernmost branch of the Asa Kawa meandered along the gradually rising floor of Wana Draw and through the northerly part of Shuri. Low rolling ground on either side of the stream offered neither cover nor concealment against Japanese fire coming from position along the reverse slope of Wana Ridge and the military crest in the southern portion of the ridge. Approximately 400 yards wide at its mouth, Wana Draw narrowed perceptibly as the stream flowing through it approached the city. Hill 55,19 a dominating piece of terrain at the southern tip of the ridge, guarded the western entry into the draw. Bristling with nearly every type of Japanese infantry weapon, the positions on the hill had clear fields of fire commanding all approaches to the draw. Manning these guns were troops from the 62nd Division’s 64th Brigade, and an ill-assorted lot of stragglers from remnants of the 15th, 23rd, and 273rd Independent Infantry Battalions, the 14th Independent Machine Gun Battalion, and the 81st Field Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion, all under command of the Brigade.20

By 0400 on 15 May, elements of the 5th Marines had relieved 2/1 and most of 3/1. At 0630, the relief was completed and Colonel Griebel assumed command of the former 1st Marines zone west of Wana. The 5th Marines commander placed 2/5 in assault with the 3rd Battalion in support and the 1st in reserve. Acting on the recommendations of battalion and regimental commanders of both the 1st and 5th Marines, General del Valle decided to neutralize the high ground on both sides of Wana Draw. Tanks and self-propelled 105-mm howitzers were to shell the area thoroughly before 2/5 tried to cross the open ground at the mouth of the draw.

Wana Ridge, rugged barrier in the path of the 1st Division, is shown looking southeast toward Shuri. (USMC 148651)

105-mm howitzer of the 15th Marines is swamped, but still in firing order after ten days of rain. (USMC 122735)

Fire teams from Company F protected nine Shermans of the 1st Tank Battalion against possible attacks from suicide-bent enemy soldiers as the tanks worked over the Japanese positions in the mouth of the draw during the morning. Because tanks invariably drew heavy artillery, mortar, and AT fire, the Marines guarding them were forced to take cover. Nevertheless, the open ground of the battle area permitted the infantry teams to cover the tanks with fire from protected positions at long range. The mediums received heavy and intense fire from the sector to their front and from numerous cave positions on both sides of the draw. Some respite was gained when naval gunfire destroyed a 47-mm AT gun which had hit three tanks at least five times each.

About midafternoon, the tanks withdrew to clear the way for a carrier-plane strike on the draw. Following this attack, the nine original tanks, now reinforced by six others, continued the process of neutralizing the draw. Another 47-mm AT gun opened up late in the afternoon, but it was destroyed before it could damage any of the tanks.

After a day spent probing the mouth of Wana Draw, 2/5 infantry companies set up night defenses east of the railroad, dug in, and established contact all along their front. At the CP that night, the 5th Marines commander observed that “Wana Draw was another gorge like the one at Awacha. It was obvious that the position would have to be thoroughly pounded before it could be taken,”21 and ordered the softening-up operations of the 15th repeated the next day.

Colonel Snedeker’s 7th Marines spent the 15th in reorganizing its infantry companies, improving occupied positions, and mopping up in the vicinity of Dakeshi.22 During the day, air liaison parties, gunfire spotters, and forward observers were kept busy directing concentrated artillery and naval gunfire bombardments and air strikes on known enemy strongpoints on Wana Ridge. At 2100, 1/7 was ordered to prepare a feint attack on 16 May, when all supporting arms were to fire a preparation and troops were to concentrate as though preparing to jump off in an assault.

The battalion was already positioned for the feint when preparatory fires began at 0755. At this time, 4.2-inch and 81-mm mortars smoked the area immediately in front of 1/7 to heighten the deception. Fifteen minutes after it had begun, the barrage was lifted for another fifteen-minute period in an attempt to deceive the Japanese. The Marines believed that the enemy, fooled into thinking that an attack was imminent, would rush from covered caves to reoccupy their battle positions, where they would again be blasted. When there was no apparent reaction to the feint, supporting arms resumed firing at 0825 with undetermined results.

At 0950, regiment notified Lieutenant Colonel John J. Gormley, the 1/7 commander, that an air strike on Wana Ridge was scheduled for 1000, immediately following which he was to send patrols forward to determine what remaining enemy resistance existed on the target. Having learned that the strike was delayed, at 1028 Lieutenant Colonel Gormley requested that the mission be cancelled and sent the patrols out after he had ordered a mortar barrage placed on the ridge.

The Company C patrols moved forward unopposed until they reached the western end of Wana Ridge. Here they received intense grenade and machine gun fire which was answered by their battalion 81-mm mortars and supporting fire from the 5th Marines. Rushing forward when this fire had been lifted, the patrols carried and occupied the troublesome objective.

Lieutenant Colonel Gormley then ordered the newly won position held and reinforced by troops he sent forward for this purpose. Once leading elements began to move out again, enemy troops lodged in burial vaults and rugged coral formations showered grenades down upon the advancing Marines. Unsuccessful in halting the advance, the enemy tried but failed to mount a counterattack at 1605. Although supporting arms of 1/7 blunted this attempt, enemy resistance to the Marine attack continued.

Nightfall forced the battalion commander to withdraw the troops spearheading the assault and move them to more secure positions on a plateau almost directly north of the ridge for night defense. Contact was then established on the right with 2/5 and on the left with 3/7. At 2400, 3/7 effected a passage of the lines to relieve the 1st Battalion, which then went into regimental reserve.

During the 16th., 15 tanks, two of them flamethrowers, had supported the attack of 1/7 from positions on Dakeshi Ridge, while a total of 30 tanks—including 4 flamethrowers—supported 2/5 by burning and blasting enemy strongpoints in Wana Draw. At 0900, the 2/5 armored support drew antitank, mortar, and artillery fire that disabled two tanks, and damaged two others, which withdrew after evacuating the crews of the stalled cripples. Two of the AT positions which had been spotted in the morning were destroyed that afternoon when the main battery of the USS Colorado was brought to bear on them. Generally, when a Marine tank was damaged and abandoned temporarily, efforts to retrieve it later were usually stymied by enemy fire. Disabled tanks remaining in the field overnight usually were either destroyed by enemy demolition teams or occupied by snipers, who converted them into armored pillboxes.

Before retiring at nightfall on 16 May, the 1st Tank Battalion had expended nearly 5,000 rounds of 75-mm and 173,000 rounds of .30 caliber ammunition, and 600 gallons of napalm on targets on Dakeshi Ridge and in Wana Draw that day.23 Following the two-day process of softening up provided by all supporting arms, the 5th Marines prepared to run the gantlet of Wana Draw on 17 May.

“Under the continued pounding of one of the most concentrated assaults in Pacific Warfare,”24 cracks appeared in the Shuri defenses on 17 May. On that day, 2/5 made the main regimental effort, sending tank-infantry teams to the mouth of Wana Draw, where they worked over the caves and pillboxes lining its sides. The 2/5 attack was made in conjunction with a 7th Marines effort to gain the pinnacle ridge forming the northern side of the draw.

When a terrific mortar and artillery barrage drove the 7th back at 1200, 2/5 assault troops—also under heavy fire-were forced back to their original positions, where they could protect the exposed flank of the 7th Marines battalion.

On the right of 2/5, Company E finally succeeded in penetrating the Japanese defenses. After having been driven back earlier in the day, the company established a platoon-sized strongpoint on its objective, the west nose of Hill 55. Because the low ground lying between this point and battalion frontlines were swept by heavy enemy fire, tanks were pressed into use for supply and evacuation purposes.

Having relieved 1/7 at 0600, 3/7 attacked towards Wana Ridge from Dakeshi Ridge with two companies in assault: Company I on the right, K on the left. A total of 12 gun and 2 flamethrower tanks supported Company K as it attempted to secure the low ridge crest northwest of Wana. Meanwhile, Company I gained and held a plateau that led to the western nose of the Wana Ridge line.

Extremely heavy resistance plagued Company K efforts to move forward, as the enemy concentrated his fire on the leading infantry elements. Attempting to lessen the effectiveness of the Marine tank-infantry tactics, the Japanese employed smoke grenades to blind the tanks and drastically restricted their supporting fires. Before the tanks could be isolated in the smoke and cut off from their infantry protection, and when the flanks of Company K became so threatened as to make them untenable, both tanks and infantry were withdrawn—the latter to Dakeshi to become 3/7 reserve. Late in the afternoon, the 3/7 commander ordered Company L forward to reinforce I for the night and to assist in the attack the next morning.

Following a period of intermittent shelling from enemy mortars and artillery during the night 17–18 May, 3/7 again attacked Wana Ridge. Supporting arms delivered intense fire on the forward slopes and crest of the ridge all morning; the attack itself began at noon. Reinforced by a platoon from L, Company I succeeded in getting troops on the ridge, but furious enemy grenade and mortar fire inflicted such heavy casualties on the assault force that Lieutenant Colonel Hurst was forced to withdraw them to positions held the previous night, where he could consolidate his lines. An abbreviated analysis by the division fairly well summarized that day’s fighting: “gains were measured by yards won, lost, then won again.”25

Pinned down by heavy enemy fire on the reverse slope of its position on Hill 55, the isolated platoon from Company E, 2/5, could neither advance nor withdraw. Tanks again supplied ammunition and rations to the dug-in troops. Six mediums initially supported the early-morning operations of 2/5 by firing into caves and emplacements in the terrain complex comprising the draw. This tank fire was coordinated with that coming from Shermans in the Wana Draw sector. In addition to this daylong tank firing, the artillery battalions expended over 7,000 rounds of 105-mm and 75-mm artillery ammunition on selected point targets.26

Under the cover of tank fire, at 1200 Company F sent one infantry platoon and an attached engineer platoon with flamethrowers and demolitions into the village of Wana to destroy enemy installations there, The party worked effectively until 1700, when it was recalled to Marine lines for the night because Wana Ridge, forming the northern side of the draw behind and overlooking the village, was still strongly infested by the enemy. Before leaving Wana, Marines destroyed numerous grenade dischargers, machine guns, and rifles found in the village and in the tombs on its outskirts.

The 1st Marine Division’s bitter contest for possession of Wana Draw continued on 19 May along the same bloody lines it had run on the four previous days. Colonel Snedeker’s regiment again made the major effort for the division, and the 5th Marines continued to punish the mouth of Wana Draw. As before, attacking Marines were sorely beset by enemy fire, which answering artillery, tank, mortar, and regimental 105-mm howitzer concentrations had failed to neutralize.

The 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines, attacked that afternoon in a column of companies, Company I in the lead, followed by Companies L and K in that order. Resistance to the attack was immediate, although the vanguard managed to reach the nose of the coral ridge to its front under a blanket of mortar shells falling all about. Then, because 3/1 was to relieve 3/7 and it was too risky to effect a relief right on the ridge under the conditions then prevailing, the leading elements withdrew about 75 yards to the rear.

Earlier in the day, 1/7 and 2/7 had been relieved in position near Dakeshi by 1/1 and 2/1 respectively. With the relief of the 3rd Battalion, the 7th Marines relinquished the responsibility for the capture of Wana Ridge to Colonel Mason’s 1st Marines, and Colonel Snedeker’s regiment went into division reserve. In the five-day struggle for Wana, the 7th Marines had lost a total of 44 men killed, 387 wounded, 91 nonbattle casualties, and 7 missing. Of this number, the 3rd Battalion sustained 20 Marines killed and 140 wounded. In a supporting and diversionary role for the five-day period, the 5th Marines suffered 13 men killed and 82 wounded.

Despite the punishment they had received from the 5th Marines and its supporting tanks, the Japanese built new positions in Wana Draw daily, and reconstructed and recamouflaged by night old ones that Marine tank fire had exposed and damaged by day. As the

assault infantry plunged further into the draw, and as the draw itself narrowed, an increasing number of Japanese defensive positions conspired with the rugged terrain to make passage more difficult. Dominating the eastern end of Wana Ridge, on the northwestern outskirts of Shuri, was 110 Meter Hill,27 commanding a view of the zones of both the 1st Marine and 77th Infantry Divisions. Defensive fire from this position thwarted the final reduction of Japanese positions in Wana Draw and eventual capture of the Shuri redoubt.

Tanks, M-75 (self-propelled 105-mm howitzers), 37-mm guns, and overhead machine gun fire supported the attacks which jumped off at 0815. The assault troops moved rapidly to the base of the objective, tanks and flamethrowers clearing the way, while enemy mortar and machine gun fire inflicted heavy casualties in the ranks of the onsurging Marines.

Initially, 3/1 moved to the southeast and up the northern slope of Wana Ridge, where it became involved in hand grenade duels with Japanese defenders. The Marines prevailed and managed to secure approximately 200 yards of this portion of the ridge. By 1538, 2/1 reported to regiment that it was on top of the objective and in contact with 3/1, and had secured all of the rest of the northern slope of the ridge with the exception of the summit of 110 Meter Hill. A considerable gap between the flanks of 2/1 and the 305th Infantry on the Marine left was covered by interlocking bands of machine gun fire and mortar barrages set up by both units. Confronted by intense enemy fire from reverse slope positions, 2/1 riflemen were unable to take the hillcrest and dug in for the night, separated from the enemy by only a few yards of shell-pocked ground.

After it tied in with 2/1 for the night of 19–20 May, Lieutenant Colonel Stephen V. Sabol’s 3rd Battalion moved out at 0845, and was again within grenade-throwing range of Wana Ridge defenders. Burning and blasting, tanks supported the assault by destroying enemy-held caves and fortified positions blocking the advance. When 3/1 had gained the northern slope of the ridge and could not budge the Japanese troops in reverse-slope defenses, Colonel Mason decided to burn them out by rolling split barrels of napalm down the hill into Japanese emplacements in Wana Draw, and then setting them afire by exploding white phosphorous (WP) grenades on top of the inflammable jellied mixture.

Working parties began manhandling drums of napalm up the hill at 1140, and had managed to position only three of them by 1500. At 1630, these were split open, sent careening down the hill, and set aflame by the WP grenades. An enemy entrenchment about 50 yards down the incline halted the drums; in the end, the Japanese sustained little damage and few injuries from this hastily contrived field expedient. The proximity of the combatants that night led to considerable mortar, hand grenade, and sniper fire, as well as the usually lively and abusive exchange of curses, insults, and threats of violence

that often took place whenever the protagonists were within shouting distance of each other.

On the division right, 2/5 jumped off in attack on 20 May at 0900, supported by artillery and M-7 fire and spearheaded by tanks. The battalion objective was the area running roughly from Hill 55 southwest to the Naha–Shuri road. A continuous artillery barrage was laid on Shuri Ridge, the western extension of the commanding height on which Shuri Castle had been built, as assault units quickly worked their way towards the objective. At 0930, lead elements were engaged in close-in fighting with enemy forces in dug-in positions bordering the road. Under constant and heavy enemy fire, engineer mine-clearing personnel preceded the tanks to make the road safe for the passage of the mediums. Working just in front of the advancing troops, the Shermans flushed a number of enemy soldiers from their hidden positions and then cut them down with machine gun fire. Close engineer-tank-infantry teamwork permitted the Marines to secure the objective by noon.

Heavy small arms and mortar fire poured into the advance 2/5 position, which Company E held all afternoon. The sources of this fire were emplacements located on Shuri Ridge. Continued artillery and pointblank tank fire, and two rocket barrages, finally silenced the enemy weapons. By 2000, Company E had established contact all along the line and dug in for the night. Except for the usual enemy mortar and artillery harassment, there was little activity on the front. Just before dawn, 1/5 relieved the 2nd Battalion in place; 2/5 then went into regimental reserve.

Once in position, 1/5 was ordered to patrol aggressively towards Shuri Ridge and on the high ground east of Half Moon Hill. It maintained a sufficient force in the vicinity of Wana Ridge and Hill 55, at the same time, to assist the 1st Marines attack. Tank-infantry teams again reconnoitered the area south of the division line against a hail of machine gun and mortar fire. In addition to providing the tanks protection from Japanese tank-destroyer and suicide units, Marine ground troops directed the tank fire on targets of opportunity. Tank commanders in vehicles that were sometimes forward of foot troops often called down artillery fire on point targets at extremely close ranges. In spite of fierce resistance that became most frenzied as Marines closed in on Shuri, the 5th Marines positions on Hill 55 were advanced slightly in order to give the division more favorable jumping off points for a concerted effort against General Ushijima’s headquarters.

At dawn on 21 May, 2/1 moved out against heavy opposition to secure the summit of 110 Meter Hill and the rest of Wana Ridge. Although some small gains were made, the objectives could not be reached. Tank support, which heretofore had been so effective, was limited because of the irregular and steep nature of the ground. Though armor could provide overhead fire, the vehicles were unable to take reverse slope positions under fire because a deep cleft at the head of the draw prevented the Shermans from getting behind the enemy. Reconnaissance reports indicated that as the draw approached Wana, it walls rose to sheer heights of from 200 to 300 feet. Lining

the wall faces were numerous, well-defended caves that were unapproachable to all but the suicidally inclined. It was readily apparent that no assault up the draw would be successful unless preceded by an intense naval gunfire, air, and artillery preparation. Included also in the reports was the fact that the steep terrain forward of Wana did not favor tank operations.

On the left of 2/1, Company G mopped up opposition in the small village on the northern outskirts of Shuri. Resisting the attempts of the company to turn the flank of 110 Meter Hill were elements of the 22nd Independent Infantry Battalion, the sole remaining first-line infantry reserve of the Thirty-second Army—thrown into the breach to hold the area around the hill.28 Advancing down the draw were two companies abreast, E and F, whose attack was initially supported by the massed fires of battalion mortars and then by all other supporting arms.

Darkening skies and intermittent rain squalls obscured the battle scene to friendly and enemy observers alike. Although it was apparent that 2/1 was right in the middle of a preregistered impact area, judging from the accuracy of enemy mortar and artillery fire, the battalion held its forward positions despite mounting casualties. A gap existing between 2/1 and the 77th Division was covered by fire, and Company F linked with Company C of 1/1, had been temporarily attached 3rd Battalion for night defense.

Under its new commander, Lieutenant Colonel Richard F. Ross, Jr.,29 3/1 attempted to clear out reverse slope positions on Wana Ridge in a concerted tank-infantry effort. According to the plan, Company L and the tanks-each to be accompanied by one fire team—would attack up Wana Draw. Supporting this assault from the crest of the ridge would be the other two infantry companies in the battalion, prepared to attack straight across the ridge on order. Their objectives were Hill 55 and the ridge line to the east.

Company C, 1/1, was ordered to take over the 3rd Battalion positions, when Lieutenant Colonel Ross’ men jumped off in the assault. At about 1415, Company L began the slow advance against bitter opposition. Almost immediately, several of the escorting tanks were knocked out by mines and AT guns. Company K moved across the draw to Hill 55 at 1500, followed by I, which was pinned down almost immediately by extremely heavy mortar and machine gun fire and unable to advance beyond the middle of the draw. By 1800, Company K was on Hill 55 and tied in with 1/5, but could not push further east towards Shuri.

Because the rampaging enemy fire prevented Companies I and L from reaching the ridgeline and advancing up Wana Draw, they were withdrawn to that morning’s line of departure positions. Company C of 1/1 was placed

under the operational control of 3/1 for the night and occupied the positions held by Company I on 20 May. Here, it tied in with Company L on the right and on the left with Company F, 2/1.

The miserable weather prevailing all day on 21 May worsened at midnight when the drizzle became a deluge and visibility was severely limited. Taking advantage of these conditions favoring an attacking force, an estimated 200 Japanese scrambled up Wana Ridge to strike all along the Company C line. In the midst of a fierce hand grenade battle, the enemy managed to overrun a few positions. These were recaptured at dawn, when the Marines regrouped, reoccupied the high ground, and restored their lines. In the daylight, approximately 180 enemy dead were counted in front of Marine positions.30

Torrential rains beginning the night of 21–22 May continued on for many days thereafter. This downpour almost halted the tortuous 1st Division drive towards Shuri. Seriously limited before by terrain factors and a determined stand by the enemy in the Wana area, tank support became nonexistent when the zone of the 5th Marines, the only ground locally which favored armored tactics, became a sea of mud. Under these conditions aiding the Japanese defense, the 1st Division was faced with the alternatives of moving ahead against all odds or continuing the existing stalemate. To make either choice was difficult, for both presented a bloody prospect.

The Army’s Fight31

For IIIAC, the period 15–21 May was marked by the struggles of its divisions to capture two key strongpoints—Wana Draw and Sugar Loaf Hill. During this same seven days, XXIV Corps units fought a series of difficult battles to gain the strongly defended hills and ridges blocking the approaches to Shuri and Yonabaru. (See Map IV) These barriers, incongruously named Chocolate Drop, Flat Top, Hogback, Love, Dick, Oboe, and Sugar, gained fleeting fame when they became the scenes of bitter and prolonged contests. But, when XXIV Corps units had turned the eastern flank of Shuri defenses and anticipated imminent success, the Army attack—like that of the Marines—became bogged down and was brought to a standstill when the rains came.

On 15 May, the 77th Division continued its grinding advance in the middle of the Tenth Army line against the hard core of Thirty-second Army defenses at Shuri; 96th Division troops, in coordination with their own assault against Dick Hill, supported the 77th Division attack on Flat Top Hill. Fighting on the left of the 96th, the 383rd Infantry found it difficult and dangerous to move from Conical Hill because of overwhelming fire coming from a hill complex southwest of their location. In addition, the 89th Regiment tenaciously held formidable and well-organized defenses on the reverse slope of Conical,

and prevented the soldiers from advancing farther south.32

On 16 May, 2/383 attacked down the southeast slope of the hill, but murderous enemy crossfire again prevented the soldiers from making any significant gains. A supporting platoon of tanks, however, ran the gantlet of fire sweeping the coastal flat and advanced 1,000 yards to enter the northwestern outskirts of Yonabaru, where the Shermans lashed the ruins of the town with 75-mm and machine gun fire. Heavy Japanese fire covering the southern slopes of Conical prevented the infantry from exploiting the rapid armor penetration, however. After having exhausted their ammunition supply, the tanks withdrew to the line of departure.

On the division right flank, the 382nd Infantry attempted to expand its hold on Dick Hill. In a violent bayonet and grenade fight, American troops captured some 100 yards of enemy terrain, but heavy machine gun fire from Oboe Hill—500 yards due south of Dick—so completely covered the exposed route of advance, the soldiers were unable to move any farther.

Fire from many of the same enemy positions which had held back 96th Division forces, also effectively prevented the 307th Infantry from successfully pushing the 77th Division attack on Flat Top and Chocolate Drop Hills. Both frontal and flanking movements, spearheaded by tanks, were held up by extremely accurate and vicious Japanese machine gun fire and mortar barrages.

Somewhat more successful on the 16th was the 305th Infantry, which threw the full weight of all of its supporting arms behind the attack of the 3rd Battalion. Flamethrower tanks and medium tanks mounting 105-mm howitzers slowly edged along the ridges leading to Shuri’s high ground. Barring the way in this broken terrain were Okinawan burial vaults which the Japanese had occupied, fortified, and formed into a system of mutually supporting pillboxes. At the end of a ferocious day-long slugging match, this armored vanguard had penetrated 200 yards of enemy territory to bring the 77th Division to within 500 yards of the northernmost outskirts of Shuri.

A very successful predawn attack by the 77th Division on 17 May surprised the Japanese, forcing them to relinquish ground. Substantial gains were made and commanding terrain captured, including Chocolate Drop Hill and other nearby hills. Advancing abreast of each other, 3/305 and 2/307 dug in at the end of the day only a few hundred yards away from Shuri and Ishimmi. Although outflanked by 3/307, Flat Top defenders sent down a heavy volume of machine gun and mortar fire on the soldiers as they attempted to move across exposed country south of the hill. Troops following the assault elements spent daylight hours mopping up, sealing caves and burial vaults, and neutralizing those enemy strongpoints bypassed in the early-morning surprise maneuver.

Practically wiped out that day was the enemy 22nd Regiment, which had defended Chocolate Drop, and whose remnants were still holding the reverse slopes of Flap Top and Dick Hills. Reinforcing these positions was the 1st

Battalion of the 32nd Regiment. On 17 May, this regiment was ordered by the 24th Division commander, Lieutenant General Tatsumi Amamiya, to take over the ground formerly held by the 22nd Regiment, and to set in a Shuri defense line that would run from Ishimmi to Dick and Oboe Hills. Taking advantage of the natural, fortress-like properties of the region which they were to defend, the depleted 32nd Regiment and survivors of the 22nd were disposed in depth to contain potential American penetrations.33 Few reserves were available to the defenders should the Americans break through.

On 17 May, the 96th Division ordered the 382nd Infantry to attack and capture the hill mass south of Dick Hill and centering about Oboe. The failure of this effort indicated that the ground here needed to be softened up further before the infantry could advance. In the sector of Conical Hill held by the 383rd, steady pressure from reverse slope defenders forced the division to commit into the line a third regiment—the 381st Infantry—to maintain the positions already held by the 96th. At this time, 3/381 assumed control of the left portion of the 2/383 sector on the eastern slope of the hill, and brought up its supporting weapons in preparation for a new attack.

While the remainder of 96th Division assault battalions held their lines and tank-infantry, demolition, and flamethrower teams mopped up in their immediate fronts, 3/381 made the division main effort. Operating to the west of the coastal road, medium tanks supported the attack by placing direct fire on machine gun positions on Hogback Ridge, a terrain feature running south from Conical Hill. Hogback’s defenders disregarded the tank fire to place heavy machine gun and mortar barrages against the battalion attacking up finger ridges sloping down to the ocean. Although this heavy resistance limited the advance to only 400 yards, the division commander believed he could successfully attack through Yonabaru to outflank Shuri.

Both frontline divisions of XXIV Corps progressed on 18 May. Units of the 77th penetrated deeper into the heart of Shuri defenses by driving 150 yards farther south along the Ginowan–Shuri highway and advancing up to 300 yards towards Ishimmi. On 19 May, the 77th Division began a systematic elimination of Japanese firing positions in 110 Meter Hill, Ishimmi Ridge, and the reverse slopes of Flat Top and Dick Hills. All of these positions provided the enemy with good observation and clear fields of fire, commanding terrain over which the American division was advancing. Every weapon in the 77th arsenal capable of doing so was assigned to place destructive fire on the enemy emplacements. While these missions were being fired, the infantry fought off a series of counterattacks growing in size and fury as darkness fell. The enemy was finally turned back at dawn on 20 May when all available artillery was called down on them.

In the 96th Division zone on the 19th, the left regiment again made the main effort while the center and right regiments destroyed cave positions and gun emplacements in the broken ground between

Conical and Dick Hills. Hogback Ridge and Sugar Hill, which rose sharply at the southern tip of this ridge to overlook Yonabaru, were bombarded by two platoons of medium tanks, six platoons of LVT(A)s, artillery, and organic infantry supporting weapons. The attack following this preparation failed, however, in the face of overwhelming enemy fire. Destruction of enemy positions spotted the day before did serve, however, to weaken further the faltering 89th Regiment defense.

Returning to Hogback Ridge on 20 May, the attacking infantry made a grinding, steady advance down the eastern slopes of the ridge and finally reached Sugar Hill. Other 96th Division units also registered some significant gains that day; 383rd Infantry assault battalions fought to within 300 yards of Love Hill, destroying those strongpoints that had blocked their progress for a week. The 382nd Infantry finally reduced all enemy defenses on the southern and eastern slopes of Dick Hill, while it supported a successful 77th Division attack on Flat Top at the same time.

On gaining Flat Top Hill, the 307th Infantry was then ready to continue the attack south to Ishimmi Ridge and then on to Shuri. Coordinating its attack with the 1st Marines on its right, the 305th advanced down the valley highway 100- 150 yards or to within 200 yards of the outskirts of Shuri. As a result of these gains, the 77th Division commander planned another predawn surprise attack, only this time on a coordinated division-wide level across the front.

Assault troops of the 307th Infantry jumped off at 0415 on 21 May in the zone of the 305th, advancing 200 yards without opposition, (See Map VIII) An hour later, leading elements had entered the northern suburbs of Shuri and were fighting their way up the eastern slopes of 110 Meter Hill. The 306th Infantry, which relieved the 305th later that morning, sent its 2nd Battalion to the right of the line where visual contact was made with the 1st Marines. By nightfall, having spent most of the day mopping up bypassed positions, the 306th set up a night defense on a line running from the forward slopes of Ishimmi Ridge, through the outskirts of Shuri, to 110 Meter Hill.

The assault battalions of the 307th Infantry, the other 77th Division frontline regiment, jumped off at 0300 to take the regimental objective, a triangularly shaped mass consisting of three hills located in open ground about 350 yards south of Flat Top. The lead elements reached the objective at dawn, but following units were unable to exploit the successful maneuver when they were discovered by the enemy and pinned down by his frontal and flanking fire. Any further move forward was prohibited by this continuous and accurate fire, and the battalion was forced to dig in at nightfall on the ground then held.

Overall, the most important advances on 21 May in the XXIV Corps zone were made by 96th Division units. As 1/383 moved out against moderate opposition to take Oboe Hill, 2/383 paced the advance by attacking over exposed terrain to its southeast to take a hill approximately 400 yards from Shuri. At 1130, when enemy elements were noticed pulling out of their positions in front of the attacking infantry, the Japanese were fired upon as they retreated towards

higher ground. Despite this withdrawal of the enemy, American forces were prevented from advancing any further during the day by isolated enemy counterattacks along the regimental lines.

On Love Hill, enemy defenders who had successfully refused to yield ground during the past week again steadfastly maintained their positions on the 21st. They called down heavy and accurate artillery concentrations on American tank-infantry teams reaching the base of the hill and forced them to turn back.

The western slopes of Hogback Ridge were secured by 2/383 as the 3rd Battalion, 381st Infantry, fought its way up the eastern slopes to the top of Sugar Hill. Every yard acquired during the day came because of the individual soldier’s efforts in the face of fanatic enemy determination to hold. Nevertheless, advance elements of 3/381 were in position about 200 yards from the Naha–Yonabaru highway by nightfall. As a result of this hard-won success, a 700-yard-long corridor down the east coast of Okinawa was secured, giving promise that the final reduction of the Shuri redoubt might be launched from this quarter.

To strengthen the attack on Shuri, which General Hedge believed could be outflanked when he viewed the progress of the 96th Division, he alerted the 7th Infantry Division and ordered it to move to assembly areas immediately north of Conical Hill on 20 May. Two days later, the division was committed in the line and attacked to take the high ground south of Yonabaru.

Intermittent rain beginning on 21 May increased steadily to become soaking torrents before the assault infantry of the 7th Division was in jumpoff positions. In no time at all, “the road to Yonabaru from the north—the only supply road from established bases in the 7th Division zone ... became impassable to wheeled vehicles and within two or three days disappeared entirely and had to be abandoned.”34 Like the Tenth Army divisions on the west coast, those on the east were effectively stymied by the mud and the rain, which now seemed to be allied with General Ushijima and his Thirty-second Army.

Fighting the Weather35

The Naha–Yonabaru valley served as a funnel through which American forces could pass to outflank Shuri. A major obstacle blocking the entrance to this route is the Ozato Hills, a rugged and complex terrain mass paralleling Nakagusuku Wan and lying between Yonabaru and the Chinen Peninsula. Since strong blocking positions were needed in the Ozato Hills to safeguard the left flank and rear of the force assigned to assault Shuri, the 184th Infantry of the 7th Division was ordered to take Yonabaru on 22 May and secure the high ground overlooking the village.

In a surprise attack at 0200, 2/184 spearheaded a silently moving assault force which passed through Yonabaru

quickly, and was on the crest of its objective—a hill south of the village—by daylight. When the enemy arose at dawn and emerged from cave shelters to man gun and infantry positions, he met sudden death under American fire. The Thirty-second Army was completely taken aback, for an American night attack was totally unexpected in this sector, much less an attack unsupported by armor.36 When the commander of the 184th saw that his initial effort was successful, he committed a second battalion and drove forward to secure other key points in the zone. By the end of the day, the regiment had advanced 1,400 yards and gained most of its objectives, even though rain and mud drastically hampered all phases of the operation.

While the 7th Division scored for the Tenth Army on the east coast, IIIAC units pushed forward on the west. In the 6th Marine Division zone, the 4th Marines attacked to gain the northern bank of the Asato Gawa. (See Map 15.) The 1st and 3rd Battalions advanced as 2/4 maintained positions on Half Moon Hill and kept contact with the 1st Marine Division. Assault troops seized the objective by 1230, when patrols crossed the shallow portion of the Asato and moved 200 yards into the outskirts of Naha before drawing any enemy fire.37 Frontline Marines dug in reverse slope positions along the northern bank of the river under the sporadic fire of heavy caliber artillery weapons and mortars. At 6th Division headquarters, plans were drawn for a river crossing on 23 May.

Although the flank divisions of the Tenth Army were making encouraging progress, the three divisions in the center of the line found success to be an elusive thing during the week of 22 May, A fanatic Japanese defense compounded the difficulties arising because of the steady rain. Supply, evacuation, and reinforcement were all but forestalled by the sea of mud, which caused the troops to wallow rather than maneuver. Under these conditions, infantry units could only probe and patrol ahead in their immediate zones.

The rain continued for nine days, and ranged from light, scattered showers to driving deluges. In the end, the entire southern front became a morass that bogged down both men and machines. Footing was treacherous in the mud swamps appearing in valley floors, and all slopes—from the gentlest to the most precipitous—were completely untrafficable. Because TAF planes had been grounded and could not fly airdrop missions, all supplies had to be manhandled to the front. Tired, wornout foot troops from both frontline and reserve units were pressed into action and formed into carrying parties.

Despite the unrelenting round-the-clock efforts of engineers to keep the road net between forward supply dumps

and the frontlines in operating condition, continued use by trucks and amtracs finally caused the roads to be closed, but only after the mud itself had bemired and stalled the vehicles. As a result, division commanders found it impossible to build up and maintain reserve stocks of the supplies needed to support a full-scale assault. With the movement of American forces all but stopped, the entire front became stalemated.

During the advance to the south, responsible Tenth Army agencies had reconnoitered both the east and west coasts of Okinawa behind the American lines in an attempt to find suitable landing and unloading sites. When discovered and found secure from enemy fire, they were developed and LSTs and other landing vessels were pressed into use to bring supplies down the coasts from the main beaches and dumps in the north.38 The two divisions deriving the major benefits from use of the overwater supply routes were the 6th Marine and 7th Infantry Divisions anchored on the open coasts. Behind the 1st Marine and 77th and 96th Infantry Divisions, in the center of the Tenth Army line, was a mired road net which prevented any resupply effort by vehicles coming both from the north and laterally from the coasts.

A sanguine outlook for continued advances by the Tenth Army flanking divisions was dispelled when they ran into resistance of the same type and intensity offered to the center units. A combination of this increased resistance and the appalling weather forestalled the potential envelopment and isolation of the main forces of the enemy, and forced the two coastal divisions into the same sort of deadlock the rest of the Tenth Army was experiencing.

Attacking to the west on 23 May, the 7th Division immediately ran into heavy resistance in the hills just north of the Yonabaru–Naha road. Both division assault regiments met increasingly stiff opposition during the day, because: “The Japanese realized that this advance along the Yonabaru–Naha road threatened to cut off the Shuri defenders. ...”39 Even in the midst of the American attacks, the enemy attempted to infiltrate and counterattack.

At the same time that the 184th Infantry moved into the Ozato Hills and towards the mouth of the valley leading to Shuri, the 32nd Infantry struck out to the west and southwest through Yonabaru to isolate the forces protecting the Thirty-second Army redoubt. Units spearheading the regimental drive were slowed and unable to advance in the face of the considerable machine gun and mortar fire coming from positions in the low hills east of Yonawa. Here, a mile southwest of Yonabaru, the regiment was forced to halt and dig in a line for the night because tanks, urgently needed to sustain the drive, had become immobilized by the mud.

On the west coast, despite the continuing rain during the night of 22–23 May, 6th Division patrols crossed and recrossed the Asato almost at will to feel out the enemy. (See Map 15.) Scouts from the 6th Reconnaissance Company patrolled the south bank of

the upper reaches of the river, and reported back at 0718 that the stream was fordable at low tide, resistance was light, and no occupied positions had been found.40

Because the patrol reports of this and other units indicated “that it might be feasible to attempt a crossing of the Asato without tank support,”41 early that morning General Shepherd ordered the 4th Marines to increase the number of reconnaissance patrols south of the river, and to be ready to cross it if enemy resistance proved light.

Between dawn and 1000 on the 23rd, Marine lines received long-range machine gun and rifle fire from high ground near Machisi, but the patrols met no determined resistance at the river bank. General Shepherd decided to force a crossing here with two assault battalions of the 4th wading through ankle-deep water to the other side. At 1130, a firm bridgehead was established against only light resistance; 1/4 was dug in and prepared to continue the attack on the right, 3/4, on the left.

The regimental objective was a low ridge, running east to west, about 500 yards south of the river in the vicinity of Machisi. The attacking Marines approaching this point began to meet sharply increased opposition. Previous suspicions concerning the nature of the defenses here were confirmed when the infantry neared the height. In addition to reverse-slope mortar emplacements,, the face of the height was studded with many Okinawan tombs that had been fortified. Darkness halted the attack 100 yards short of the objective, where the troops were ordered to organize and defend the high ground they held.