Part IV: Occupation of Japan

Blank page

Chapter 1: Initial Planning and Operations

The war was over, but the victory was not yet secure. Foremost among the multitude of new and pressing problems confronting Allied planners was the question of how the Japanese military would react to the sudden peace. On bypassed islands throughout the Pacific, on the mainland of Asia, and in Japan itself, over four million fighting men were still armed and organized for combat. Would all of these men, who had proven themselves to be bitter-end, fanatical enemies even when faced with certain destruction, accept the Emperor’s order to lay down their weapons? Or would some of them fight on, refusing to accept or believe in the decision of their government? Would the tradition of fealty to the wishes of the Emperor overbalance years of conditioning that held surrender to be a crushing personal and national disgrace?

Logically, the focal point of Japanese physical and moral strength was the seat of Imperial rule. If Tokyo could be occupied without incident, the chances for a successful and bloodless occupation of Japan and the peaceful surrender of outlying garrisons would be greatly enhanced. Plans for seizure of ports of entry in the Tokyo Bay area by occupation forces received top priority. Speed was essential and the spearhead troops of the occupying forces were selected from those units with the highest state of combat readiness.

From General MacArthur’s command, the 11th Airborne Division was to stage from Luzon through Okinawa to an airfield outside of Tokyo. Admiral Nimitz ordered the Third Fleet, cruising the waters off Japan, to form a landing force from ships’ complements to supplement the force that was to seize Yokosuka Naval Base in Tokyo Bay. To augment this naval force, FMFPac was directed to provide a regimental combat team for immediate occupation duty. These Marines, and others who followed them, were destined to play an important role in the occupation of Japan.

The Yokosuka Operation1

Months before the fighting ended, preliminary plans and concepts for the

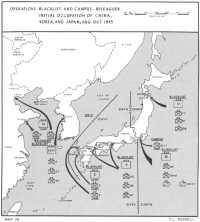

occupation of Japan had been formulated at the headquarters of MacArthur and Nimitz. Staff studies, based on the possibility of swift collapse of enemy resistance, were prepared and distributed at army and fleet level for planning purposes. In the early summer of 1945, as fighting raged on Okinawa and in the Philippines, dual planning went forward for both the assault on Japan (OLYMPIC and CORONET) and the occupation operation (BLACKLIST). (See Map 26.)

Many essential elements of the two plans were similar, and the Sixth Army, which had been slated to make the attack on Kyushu under OLYMPIC, was given the contingent task of occupying southern Japan under BLACKLIST.2 In like manner, the Eighth Army, utilizing the wealth of information it had accumulated regarding Honshu in planning CORONET, was designated the occupying force for northern Japan. The Tenth Army, also scheduled for the Honshu assault by CORONET, was given the mission of occupying Korea in BLACKLIST plans.3

When, in the wake of atomic bombings and Russian entry into the war, the Japanese government made its momentous decision to surrender, the “only military unit at hand with sufficient power to take Japan into custody at short notice and enforce the Allies’ will until occupation troops arrived”4 was Admiral William F. Halsey’s Third Fleet, at sea off the enemy coast. Advance copies of Halsey’s Operation Plan 10–45 for the occupation of Japan, which set up Task Force 31, the Yokosuka Occupation Force, were distributed on 8 August. Two days later, Rear Admiral Oscar C. Badger (Commander, Battleship Division 7) was designated the commander of TF 31, and all commanders of carriers, battleships, and cruisers in the Third Fleet were alerted to organize and equip bluejacket and Marine landing forces from amongst their crews. At the same time, FMFPac directed the 6th Marine Division to furnish one RCT to the Third Fleet for possible early occupation duty in Japan.5

General Shepherd, the division commander, without hesitation selected the 4th Marines. This was a symbolic gesture on his part, as the old 4th Marine Regiment had participated in the Philippine Campaign in 1942 and had been captured with other U.S. forces in the Philippines. Now the new 4th Marines would be the main combat formation taking part in the initial landing and occupation of Japan.6

Brigadier General William T. Clement, Assistant Division Commander, was named to head the Fleet Landing Force.

On 11 August, IIIAC prepared preliminary plans for the activation of Task Force Able, which consisted of a skeletal headquarters detachment, the

Map 26: Operations BLACKLIST and CAMPUS-BELEAGUER—Initial Occupation of China, Korea, and Japan; Aug–Oct 1945

4th Marines, Reinforced,7 an amphibian tractor company, and a medical company. Concurrently, oficers designated to form General Clement’s staff were alerted and immediately began planning to load out the task force. Warning orders, directing that the RCT with attached units be ready to embark within 48 hours, were passed to the staff.

The curtain of secrecy surrounding the proposed operation was lifted at 0900 on 12 August so that task force units could deal directly with the necessary service and supply agencies without processing their requests through the corps staff. All elements of the task force were completely re-outfitted, and the 5th Field Service Depot and receiving units went on a 24-hour day to complete the resupply task. The 4th Marines joined 600 replacements from the FMFPac Transient Center, Marianas, to fill the gaps in its ranks left by combat attrition and stateside rotation.

Dump areas and dock space were allotted by the Island Commander, Guam, to accommodate the five transports, a cargo ship, and an LSD of Transport Division 60 assigned to lift Task Force Able. The mounting-out process was considerably aided by the announcement that all ships would arrive in port on 13 August, 24 hours later than they were originally scheduled. On the evening of the 14th, however, “all loading plans for supplies were thrown into chaos”8 by news of the substitution of a smaller type of transport for one of those of the original group. The resultant reduction of shipping space was partially made up by the assignment of an LST to the transport force. Later, after the task force had departed Guam, a second LST was allotted to lift most of the remaining supplies, including the tractors of Company A, 4th Amphibian Tractor Battalion.

Loading began at 1600, 14 August, and continued throughout the night. The troops boarded ship between 1000 and 1200 the following day, and that evening, the transport division sailed for its rendezvous at sea with the Third Fleet. “In a period of approximately 96 hours the Fourth Regimental Combat Team, Reinforced, had been completely re-outfitted, all equipment deficiencies corrected, all elements provided an initial allowance to bring them up to T/O and T/A [Table of Allowance] levels, and a thirty-day re-supply procured for shipment.”9

Two days prior to the departure of the main body of Task Force Able, General Clement and a nucleus of his headquarters personnel left Guam on the LSV (landing ship, vehicle) USS Ozark to join the Third Fleet. There had been

no opportunity for preliminary planning, and no definite mission had been received, so the time en route to the rendezvous was spent studying intelligence summaries of the Tokyo Bay area. Halsey’s ships were sighted and joined on 18 August. The next morning, Clement and key members of his staff transferred to the battleship Missouri for the first of a round of conferences on the coming operation.10

Admiral Badger formed TF 31 on 19 August from the ships assigned to him from the Third Fleet. The transfer of men and equipment to designated transports by means of breeches buoys and cargo slings began immediately. Carriers, battleships, or cruisers were brought along both sides of a transport to expedite the operation.11 In addition to the landing battalions of bluejackets and Marines, Third Fleet units formed base maintenance companies, a naval air activities organization to operate a Yokosuka airfield, and nucleus crews to take over captured Japanese vessels. Vice Admiral Sir Bernard Rawlings’ British Carrier Task Force contributed a landing force of seamen and Royal Marines. In less than three days, the task of transferring at sea some 3,500 men and hundreds of tons of weapons, equipment, and ammunition was accomplished. The newly formed units, as soon as they reported on board their transports, began an intensive program of training for ground combat operations and occupation duties.

On 20 August, the ships carrying the 4th RCT arrived and joined the burgeoning task force. General Clement’s command now included the 5,400 men of the reinforced 4th Marines, a three-battalion regiment of approximately 2,000 Marines taken from 33 ships’ detachments,12 a naval regiment of 956 men organized from the crews of 10 ships into a regimental headquarters, landing battalions, and 8 nucleus crew units to handle captured shipping,13 and a British battalion of 250 seamen and 200 Royal Marines. To act as a floating reserve for the landing force, five additional battalions of bluejackets were organized and appropriately equipped from within the carrier groups.

Fleet Landing Force personnel are transferred from USS Missouri to USS Iowa somewhere at sea off the coast of Japan prior to the initial occupation landings. (USN 80-G-332826)

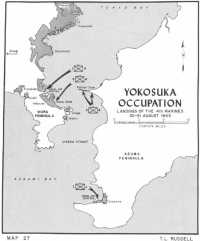

Halsey had assigned TF 31 a primary mission of seizing and occupying the Yokosuka Naval Base and its airfield. (See Map 27.) Initial collateral missions included the demilitarization of the entire Miura Peninsula, which formed the western arm of the headlands enclosing Tokyo Bay, and the seizure of the Zushi area, tentative headquarters for MacArthur, on the southwest coast of the peninsula. To accomplish these missions two alternative schemes of maneuver were considered. The first contemplated a landing by assault troops on beaches near the town of Zushi, followed by an overland drive east across the peninsula to secure the naval base for the landing of supplies and reinforcements. The second plan involved a direct landing from within Tokyo Bay on the beaches and docks of Yokosuka Naval Base and Air Station, followed on order by the occupation of Zushi and the demilitarization of the entire peninsula. All planning by TF 31 was coordinated with that of the Eighth Army, whose commander, Lieutenant General Robert L. Eichelberger, had been appointed by MacArthur to command the forces ashore in the occupation of northern Japan.

On 21 August, General Eichelberger, who had been informed of the alternative plans formulated by TF 31, directed that the landing be made at the naval base rather than in the Zushi area. Admiral Halsey had recommended the adoption of the Zushi landing plan since it did not involve bringing shipping into restricted Tokyo Bay until assault troops had dealt with “the possibility of Japanese treachery.”14 The weight of evidence, however, was rapidly swinging in support of the theory that the enemy was going to cooperate fully with the occupying forces and that some of the precautions originally thought necessary could now be held in abeyance. But the primary reason for the selection of Yokosuka rather than Zushi for the landing area was the problems that would arise in moving the landing force overland from Zushi to Yokosuka. “This overland movement would have exposed the landing force to possible enemy attack while its movement was restricted over narrow roads and through a series of tunnels which were easily susceptible to sabotage. Further, it would have delayed the early seizure of the major Japanese naval base.”15

Eichelberger’s directive also included the information that the 11th Airborne Division was to establish its own airhead at Atsugi airfield a few miles northwest of the north end of the Miura Peninsula. The original plans of the Fleet Landing Force, which had been made on the assumption that General Clement’s men would seize Yokosuka Air Station for the airborne operation, had to be changed to provide for a simultaneous Army-Navy landing. A tentative area of responsibility including the cities of Uraga, Kubiri, Yokosuka, and Funakoshi was assigned to Clement’s force, and the rest of the peninsula became the responsibility of the 11th Airborne Division.

To ensure the safety of Allied warships entering Tokyo Bay, Clement’s

Map 27: Yokosuka Occupation—Landings of the 4th Marines, 30–31 August 1945

operation plan detailed the British Landing Force to land on and demilitarize four small island forts in the Uraga Strait at the entrance to Tokyo Bay. To erase the threat of shore batteries and coastal forts, the reserve battalion of the 4th Marines (2/4) was given the mission of landing on Futtsu Saki, a narrow point of land jutting into the eastern side of Uraga Strait. After completing its mission, 2/4 was to re-embark in its landing craft and rejoin its regiment. Nucleus crews from the Fleet Naval Landing Force were to enter the inner Yokosuka Harbor prior to the designated H-Hour and take over the damaged battleship Nagato, whose guns commanded the landing beaches.

The 4th Marines, with 1/4 and 3/4 in assault, were scheduled to make the initial landing at Yokosuka on L-Day. The battalions of the Fleet Marine and Naval Landing Forces were to land in reserve and take control of specific areas of the naval base and air station, while the 4th Marines pushed inland to link up with elements of the 11th Airborne Division landing at Atsugi airfield. The cruiser San Diego, Admiral Badger’s flagship, 4 destroyers, and 12 gunboats were to be prepared to furnish naval gunfire support on call. Although no direct support planes were assigned, approximately 1,000 fully armed aircraft would be airborne and available if needed. Despite the hope that the Yokosuka landing would be uneventful, TF 31 was prepared to deal with either organized resistance or individual acts of fanaticism on the part of the Japanese.

L-Day had been originally scheduled for 26 August but on 20 August, a threatening typhoon forced Admiral Halsey to postpone the landing date to the 28th. Ships were to enter Sagami Wan, the vast outer bay, on L minus 2. On 25 August, word was received from MacArthur that the anticipated typhoon would delay Army air operations for 48 hours, and L-Day was consequently set for 30 August and the entry of the Sagami Wan ordered for the 28th.

The Japanese had been warned as early as 15 August to begin minesweeping in the waters off Tokyo to facilitate the operations of the Third Fleet. On the morning of the day stipulated for American entry into Sagami Wan, Japanese emissaries and pilots were to meet with Rear Admiral Robert B. Carney, Halsey’s Chief of Staff, and Admiral Badger on board the Missouri to receive instructions relative to the surrender of the Yokosuka Naval Base and to guide the first Allied ships into anchorages. Halsey was not anxious to keep his ships, many of them small vessels crowded with troops, at sea in typhoon weather, and he asked and received permission from MacArthur to put into Sagami Wan one day early.16

The Japanese emissaries reported on board the Missouri early on 27 August. They said a lack of suitable minesweepers had prevented them from clearing Sagami Wan and Tokyo Bay, but the movement of Allied shipping to safe berths in Sagami Wan under the guidance of Japanese pilots was accomplished nonetheless without incident. By late afternoon, the Third Fleet was anchored at the entrance of Tokyo Bay. American minesweepers checked the

channel leading into the bay and reported it clear.

On 28 August, the first American task force, consisting of combat ships of Task Force 31, entered Tokyo Bay and dropped anchor off Yokosuka at 1300. Vice Admiral Totsuka, Commandant of the First Naval District and the Yokosuka Naval Base, and his staff reported to Admiral Badger in the San Diego for further instructions regarding the surrender of his command. Only the absolute minimum of maintenance personnel, interpreters, guides, and guards were to remain in the naval base area; the guns of the forts, ships, and coastal batteries commanding the bay were to be rendered inoperative; the breechblocks were to be removed from all antiaircraft and dual-purpose guns. Additionally, the Japanese were told to fly a white flag over every gun position and to station at each warehouse and building an individual who had a complete inventory of the building and keys to all the spaces. “Both of the above were meticulously carried out.”17

As the naval commanders made arrangements for the Yokosuka landing, a reconnaissance party of Army troops landed at Atsugi airfield to prepare the way for the airborne operation on L-Day. Radio contact was established with Okinawa, where the 11th Division was waiting to execute its part in BLACKLIST. The attitude of the Japanese officials, both at Yokosuka and Atsugi, was uniformly one of docility and cooperation, but bitter experience caused the Allied commanders and troops to view with a jaundiced eye the picture of the Japanese as meek and harmless.

On the evening of 27 August appeared a reminder of another aspect of the war. At that time, two British prisoners of war hailed one of the Third Fleet picket boats in Tokyo Bay and were taken on board the San Juan, command ship of a specially constituted Allied Prisoner of War Rescue Group. Their harrowing tales of life in the prison camps and of the extremely poor physical condition of many of the prisoners prompted Halsey to order the rescue group to stand by for action on short notice. On 29 August, the Missouri and the San Juan task group entered Tokyo Bay. At 1420, Admiral Nimitz arrived by seaplane and authorized Halsey to begin rescue operations immediately.18 Special teams, guided and guarded by carrier planes overhead, immediately started the enormous task of bringing in the prisoners from the many large camps in the Tokyo–Yokohama area. By 1910 that evening, the first RAMPs (Recovered Allied Military Personnel) arrived on board the hospital ship Benevolence, and at midnight 739 men had been brought out.19

Long before dawn on L-Day, the first group of transports of TF 31 carrying 2/4 began moving into Tokyo Bay. All

the plans of the Yokosuka Occupation Force had been based on an H-Hour of 1000 for the main landing, but last-minute word was received from MacArthur on 29 August that the first serials of the 11th Airborne Division would be landing at Atsugi airfield at 0600. Consequently, to preserve the value and impact of simultaneous Army-Navy operations, TF 31 plans were changed to allow for the earlier landing time.

The first landing craft carrying Marines of 2/4 touched the south shore of Futtsu Saki at 0558; two minutes later, the first transport plane rolled to a stop on the runway at Atsugi, and the occupation of Japan was underway. In both areas, the Japanese had followed their instructions to the letter. On Futtsu Saki the coastal guns and mortars had been rendered useless, and only the bare minimum of maintenance personnel, 22 men, remained to make a peaceful turnover of the forts and batteries. By 0845, the battalion had accomplished its mission and was re-embarking for the Yokosuka landing, now scheduled for 0930.

With first light came dramatic evidence that the Japanese would comply with the surrender terms. On every hand, lookouts on TF 31 ships could see white flags flying over abandoned and inoperative gun positions. Nucleus crews from the Fleet Naval Landing Force boarded the battleship Nagato at 0805 and received the surrender from a skeleton force of officers and technicians; the firing locks of the ship’s main battery had been removed and all secondary and AA guns had been dismounted. On the island forts, occupied by the British Landing Force at 0900, the story was much the same—the coastal guns had been rendered ineffective, and the few Japanese remaining as guides and interpreters amazed the British with their cooperativeness.

The Japanese had not only cleared the naval yard and the airfield areas as directed, but had removed from the immediate area all Japanese whom they considered ‘hot-headed’ or whom they believed would not abide by the Emperor’s decree. Additionally, uniformed police from Tokyo had been brought down and were stationed outside of the Initial Occupation Line which effectively cordoned the occupation forces from the Japanese population. It was obvious that the Japanese fully intended to carry out the terms of the surrender.20

The main landing of the 4th Marines, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Fred D. Beans, was almost anticlimactic Exactly on schedule, the first waves of 1/4 and 3/4 crossed the line of departure and headed for their respective beaches. At 0930, men of the 1st Battalion landed on Red Beach southeast of Yokosuka airfield and those of the 3rd Battalion on Green Beach in the heart of the Navy yard. There was no resistance. The Marines moved forward rapidly, noting that the few unarmed Japanese present wore white armbands, according to instructions, to signify that they were essential maintenance troops, officials, or interpreters. Leaving guards at warehouses, primary installations, and gun positions, the 4th Marines pushed on to reach the designated Initial Occupation Line.

General Clement and his staff landed at 1000 on Green Beach and were met by a party of Japanese officers, who

Members of the Yokosuka Occupation Force inspect a Japanese fortification on Futtsu Saki. (USMC 134741)

General Clement looks over Yokosuka Naval Base after its surrender by the former commander (r.). (USMC 133863)

formally surrendered the naval base area. “They were informed that noncooperation or opposition of any kind would be severely dealt with.”21 Clement then proceeded to the Japanese headquarters building, where an American flag presented by the 6th Marine Division was officially raised.22

Vice Admiral Totsuka had been ordered to be present on the docks of the naval base to surrender the entire First Naval District to Admiral Carney, acting for Admiral Halsey, and Admiral Badger. The San Diego, with Carney and Badger on board, tied up at the dock at Yokosuka at 1030. The surrender took place shortly thereafter with appropriate ceremony, and Badger, accompanied by Clement, departed for the Japanese Naval Headquarters building to set up the headquarters of TF 31.

With operations proceeding satisfactorily at Yokosuka and in the occupation zone of the 11th Airborne Division, General Eichelberger took over operational control of the Fleet Landing Force from Halsey at 1200. Both of the top American commanders in the Allied drive across the Pacific set foot on Japanese soil on L-Day; General MacArthur landed at Atsugi airfield at 1419 to begin de facto rule of Japan, which was to last more than five years, and Admiral Nimitz, accompanied by Halsey, came ashore at Yokosuka at 1330 to make an inspection of the naval base.

Reserves and reinforcements landed at Yokosuka during the morning and early afternoon according to schedule. The Fleet Naval Landing Force took over the area that had been secured by 3/4, and the Fleet Marine Landing Force occupied the airfield installations seized earlier by 1/4. The British Landing Force, after evacuating all Japanese personnel from the island forts, landed at the navigation school in the naval base and took over the area between the sectors occupied by the Fleet Naval and Marine Landing Forces. Azuma, a large island hill mass, which had been extensively tunneled for use as a small boat supply base, was part of the British occupation area. It was investigated by a force of Royal Marines and found deserted.

The 4th Marines, relieved by the other elements of the landing force, moved out to the Initial Occupation Line and set up a perimeter defense for the naval base and airfield. Patrol contact was made with the llth Airborne Division, which had landed 4,200 men during the day.

The first night ashore was uneventful, marked only by routine guard duty. General MacArthur’s orders to disarm and demobilize had been carried out with amazing speed. There was no evidence that the Japanese would do anything but cooperate with the occupying troops. The Yokosuka area, for example, which had formerly been garrisoned by about 50,000 men, now held less than a tenth of that number in skeletal headquarters,

processing, maintenance, police, and minesweeping units. It was clear that, militarily at least, the occupation was slated for success.

On 31 August, the Fleet Landing Force continued to consolidate its hold on the naval base area. Company L of 3/4 sailed in two destroyer transports to Tateyama Naval Air Station on the northeastern shores of Sagami Wan to reconnoiter the beach approaches and to cover the 3 September landing of the 112th Cavalry RCT. Here again, the Japanese were waiting peacefully to carry out their surrender instructions.

Occupation operations continued to run smoothly as preparations were made to accept the surrender of Japan on board the Missouri. Even as the surrender ceremony was taking place, advance elements of the main body of the Eighth Army occupation force were entering Tokyo harbor. Ships carrying the headquarters of the XI Corps and the 1st Cavalry Division docked at Yokohama. Transports with the 112th Cavalry RCT on board moved to Tateyama, and on 3 September, the troopers landed and relieved Company L of 3/4, which then returned to Yokosuka.

As the occupation operation proceeded without the discovery of any notable obstacles, plans were laid to dissolve the Fleet Landing Force and TF 31. The 4th Marines was selected to take over responsibility for the entire naval base area. By 6 September, ships’ detachments of bluejackets and Marines had returned to parent vessels and the provisional landing units were disbanded.

While a large part of the strength of the Fleet Landing Force was returning to normal duties, a considerable augmentation to Marine strength in northern Honshu was being made. On 23 August, AirFMFPac had designated Marine Aircraft Group 31, then at Chimu airfield on Okinawa, to move to Japan as a supporting air group for the northern occupation. Colonel John C. Munn, its commanding officer, had reconnoitered Yokosuka airfield soon after the initial landing, and on 7 September the first echelon of his headquarters and the planes of Marine Fighter Squadron 441 flew in from Okinawa. Surveillance flights over the Tokyo Bay area began the following day as additional squadrons of the group continued to arrive. Initially, Munn’s planes served under Third Fleet command, but on 16 September, MAG-31 came under operational control of Fifth Air Force.

Admiral Badger’s TF 31 had been dissolved on 8 September when the Commander, Fleet Activities, Yokosuka, assumed responsibility to SCAP for the naval occupation area. General Clement’s command continued to function for a short time thereafter while most of the reinforcing units of the 4th Marines loaded out for return to Guam. On 20 September, Lieutenant Colonel Beans relieved General Clement of his responsibilities at Yokosuka, and the general and his Task Force Able staff flew back to Guam to rejoin the 6th Division. Before he left, however, Clement was able to take part in a ceremony in which 120 RAMPs of the “old” 4th Marines captured at Corregidor, received the colors of the “new” 4th from the hands of the men who had carried on the regimental

tradition in the Pacific war.23

After the initial major contribution of naval land forces to the occupation of northern Japan, the operation became more and more an Army task. As additional troops arrived, the Eighth Army area of effective control was enlarged to include all of northern Japan. In October, the occupation zone of the 4th Marines was reduced to include only the naval base, airfield, and town of Yokosuka. In effect, the regiment became a naval base guard detachment, and on 1 November, control of the 4th Marines passed from Eighth Army to the Commander, U.S. Fleet Activities, Yokosuka.24

In addition to routine security and military police patrols, the Marines also carried out Eighth Army demilitarization directives, and collected and disposed of Japanese military and naval material. Detachments from the regiment supervised the unloading at Uraga of Japanese garrison troops returning from bypassed Pacific outposts.

On 20 November, the 4th Marines was detached from the administrative control of the 6th Division and placed directly under FMFPac. Orders were received directing that preparations be made for 3/4 to relieve the regiment of its duties in Japan, effective 31 December. In common with the rest of the Armed Forces, the Marine Corps faced great public and Congressional pressure to send its men home for discharge as rapidly as possible. Its world-wide commitments had to be examined with this in mind. The Japanese attitude of cooperation with occupation authorities fortunately permitted considerable reduction of troop strength.

In Yokosuka, Marines who did not meet the age, service, or dependency point total necessary for discharge in December or January were transferred to the 3rd Battalion, and men with the requisite number of points were concentrated in the 1st and 2nd Battalions. On 1 December, 1/4 completed loading out and sailed for the States to be disbanded. The 3rd Battalion, reinforced by the regimental units and a casual company formed to provide replacements for ships’ Marine detachments, relieved 2/4 of all guard responsibilities on 24 December. The 2nd Battalion, with the

Regimental Weapons and the Headquarters and Service Companies, loaded out between 27–30 December and sailed for the United States on New Year’s Day.

The 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines, assumed the duties of the regiment at midnight on 31 December, although a token regimental headquarters remained in Yokosuka to carry on in the name of the 4th Marines. On FMFPac order, this headquarters detachment left Japan on 6 January to join the 6th Marine Division at Tsingtao, in North China.

On 15 February 1946, 3/4 was reorganized and redesignated the 2nd Separate Guard Battalion (Provisional), FMFPac. Its military police and security duties in the naval base area remained the same. Most of the occupation tasks of demilitarization in the limited area of the naval base had been completed, and the battalion settled into a routine of guard, ceremonies, and training that was little different from that of any Navy yard barracks detachment in the United States.

The continued cooperation of the Japanese with SCAP occupation directives and the lack of any overt signs of resistance considerably lessened the need for the fighter squadrons of MAG-31. On 7 October, Fifth Air Force returned control of the group to the Navy. Regular reconnaissance flights in the Tokyo area were discontinued on 15 October, and the operations of MAG-31 were confined largely to mail, courier, transport, and training flights. Personnel and unit reductions similar to those imposed on the 4th Marines also occurred in the air units. By the spring of 1946, the need for Marine participation in the occupation of Japan had diminished, and early in May, MAG-31 received orders to return to the United States. By 20 June, all serviceable aircraft had been shipped out and on that date, all group personnel were flown out of Japan. The departure of MAG-31 marked the end of Marine occupation activities in northern Japan and closed the final chapter of the Yokosuka operation.

Sasebo–Nagasaki Landings25

The favorable reports of Japanese compliance with surrender terms in northern Japan allowed a considerable number of changes to be made in the operation plans of Sixth Army and Fifth Fleet. Prisoner of war evacuation groups could be sent into ports of southern Honshu and Kyushu prior to the arrival of occupation troops, and the main landings could be made administratively without the show of force originally thought necessary. In fact, before the first troop echelon of Sixth Army arrived in Japan, almost all of the RAMPs and civilian internees had been

The “new” 4th Marines passes in review for members of the “old” 4th, recently liberated from prison camps. (USMC 135287)

26th Marines moves into Sasebo. (USMC 139128)

released from their prisons and processed for evacuation by sea or air.

Japanese authorities received orders from SCAP to bring Allied prisoners into designated processing centers on Honshu and Kyushu. In the Eighth Army occupation zone, Yokohama was the center of recovery activities, and by 21 September, 17,531 RAMPs and internees (including over 7,500 from the Sixth Army area) had been examined there and hospitalized or evacuated.26 On 12 September, after Fifth Fleet minesweepers had cleared the way, a prisoner recovery group put into Wakayama in western Honshu and began processing RAMPs. In less than three days, the remainder of the prisoners in the Sixth Army area on Honshu and those from Shikoku—in all 2,575 men—had been embarked in evacuation ships.

Atom-bombed Nagasaki, which has one of the finest natural harbors in Japan, was chosen as the evacuation port for men imprisoned in Kyushu. Minesweeping of the approaches to the port began on 8 September, and the RAMP evacuation group was able to enter on the 11th. The operation was essentially completed by the time occupation troops began landing in Nagasaki; over 9,000 prisoners were recovered.

At the time that the Eighth Army was extending its hold over northern Japan, and the recovery teams and evacuation groups were clearing the fetid prison compounds, preparations for the Sixth Army occupation of western Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu continued. The occupation area contained 55 percent of the total Japanese population, including half of the presurrender home garrisons, three of the four major naval bases in Japan, all but two of its principal ports, four of its six largest cities, and three of its four main transportation centers. Kyushu, which was destined to be largely a Marine occupation responsibility, supported a population of 10 million in 15,000 square miles of precipitous terrain. Like all of Japan, every possible foot of the island was intensively cultivated, and enough rice and sweet potatoes were produced to allow inter-island export. The main value of Kyushu to the Japanese economy, however, was its industries. The northwest half of the island contains extensive coal fields, the greatest pig iron and steel producing district in Japan, and most important shipyards, plus a host of smaller industrial facilities.

The V Amphibious Corps, initially composed of the 2nd, 3rd, and 5th Marine Divisions, had been given the task of occupying Kyushu and adjacent areas of western Honshu and Shikoku in Sixth Army plans, at the same time that the I and X Corps of the Eighth Army took control of the rest of western Honshu and Shikoku. The Fifth Fleet, under Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, was responsible for collecting, transporting, and landing the scattered elements of General Walter Krueger’s army.27 Because of a lack of adequate shipping, the Marine amphibious corps was not able to

move its major units to the target simultaneously.28 Therefore, it was necessary that the transport squadron that lifted the 5th Marine Division and VAC Headquarters from the Hawaiian Islands be sent to the Philippines to load out the 32nd Infantry Division, which was substituted on 6 September for the 3rd Marine Division in the occupation force.29

The first objective to be secured in the VAC zone under Sixth Army plans was the naval base at Sasebo in northwestern Kyushu. (See Map 28.) Its occupation by the 5th Marine Division was to be followed by the seizure of Nagasaki 30 air miles to the south by the 2nd Marine Division. When the turn-around shipping arrived, the 32nd Infantry Division was to occupy the Fukuoka–Shimonoseki area, either by an overland move from Sasebo or a direct landing, if the mined waters of Fukuoka harbor permitted. Once effective control had been established over the entry port area, the subordinate units of VAC divisions would gradually spread out over the entire island of Kyushu and across the Shimonoseki straits to the Yamaguchi Prefecture of Honshu to complete the occupation tasks assigned by SCAP.30

Major General Harry Schmidt, VAC commander, opened his command post on board the Mt. McKinley off Maui in the Hawaiian Islands on 1 September and sailed to join the 5th Division convoy, already en route to Saipan. LST and LSM groups left the Hawaiian area on 3 September with corps troops and the numerous Army augmentation units necessary to make the combat units an effective occupation force. At Saipan, the various transport groups rendezvoused and units of the 2nd Marine Division embarked. Conferences were held to clarify plans for the operations, and two advance reconnaissance parties were dispatched to Japan. One, led by Colonel Walter W. Wensinger, VAC Operations Officer, and consisting of key staff officers of both the corps and the 2nd Division, flew to Nagasaki, where it arrived on 16 September. The second party of similar composition, but with beachmaster representatives and 5th Division personnel included, left for Sasebo by high speed transport (APD) on 15 September. The mission of the parties was:–

... to facilitate smooth and orderly entry of U.S. forces into the Corps zone of responsibility by making contact with

Map 28: Maximum deployment of VAC on Kyushu as of 14 October 1945

key Japanese civil and military authorities; to execute advance spot checks on compliance with demilitarization orders: and to ascertain such facilities for reception of our forces as condition and suitability of docks and harbors, adequacy of sites selected by map reconnaissance for Corps installations, condition of airfields, roads, and communications.31

After issuing instructions to Japanese officials at Nagasaki, Colonel Wensinger and the corps staff members proceeded by destroyer to Sasebo where preliminary arrangements were made for the arrival of the 5th Division. On 20 September, the second reconnaissance party arrived at Sasebo, contacted Wensinger, and completed preparations for the landing.

At dawn on 22 September (A-Day), the transport squadron carrying Major General Thomas E. Bourke’s 5th Marine Division and corps headquarters troops arrived off Sasebo. Members of the advance party transferred from an APD which had met the convoy, and reported to their respective unit command ships. At 0859, after Japanese pilots had directed the transports to safe berths in the inner harbor of Sasebo, the 26th Marines (less 3/26) began landing on beaches at the naval air station. As the men advanced rapidly inland, relieving Japanese guards on naval base installations and stores, ships carrying other elements of the division moved to the Sasebo docks to begin general unloading. The shore party, reinforced by the 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines, was completely ashore by 1500 and started cargo unloading operations which continued through the night.

The rest of the 28th Marines, in division reserve, remained on board ship on A-Day. The 1st Battalion of the 27th Marines landed on the docks in late afternoon and moved out to occupy the zone of responsibility assigned its regiment. Before troop unloading was suspended at dusk, two artillery battalions of the 13th Marines and regimental headquarters had landed on beaches in the aircraft factory area, and the 5th Tank Battalion had disembarked at the air station. All units ashore established guard posts and security patrols, but the first night of the division in Japan passed without any noticeable event.

On 23 September, as most of the remaining elements of the 5th Division landed and General Bourke set up his command post ashore, patrols started probing the immediate countryside. Company C (reinforced) of the 27th Marines was sent to Omura, about 22 miles southeast of Sasebo, to establish a security guard over the naval air training station there. Omura airfield had been selected as the base of Marine air operations in southern Japan. A reconnaissance party, led by Colonel Daniel W. Torrey, Jr., commanding officer of MAG-22, had landed and inspected the field on 14 September, and the advance flight echelon of his air group had flown in from Okinawa six days later. Corsairs of VMF-113 reached Omura on 23 September, and the rest of the group flight echelon arrived before the month was over. The primary mission of MAG-22 was similar to that of MAG-31 at Yokosuka: surveillance flights in support of occupation operations.

As flight operations commenced at Omura and the 5th Division consolidated its hold on Sasebo, the second major element of VAC landed in Japan. The early arrival at Saipan of the transports assigned to lift the 2nd Division, coupled with efficient staging and loading, had enabled planners to move the division landing date ahead two days. When reports were received that the approaches to the originally selected landing beaches were mined but that the harbor at Nagasaki was clear, the decision was made to land directly in the harbor area. At 1300 on 23 September, the 2nd and 6th Marines landed simultaneously on the east and west sides of the harbor.

The two regiments moved out swiftly to occupy the city and curtain off the atom-bomb-devastated area. The Marine detachments from the cruisers Biloxi and Wichita were relieved by 3/2, which took up the duty of providing security guards in Nagasaki for RAMP operations. Ships were brought alongside of wharfs and docks to facilitate cargo handling, and unloading operations were well underway by nightfall. A quiet calm ruled the city to augur a peaceful occupation.

On 24 September, as the rest of Major General LeRoy P. Hunt’s 2nd Division began landing, the corps commander arrived from Sasebo by destroyer to inspect the Nagasaki area. General Schmidt had established his CP ashore at Sasebo the previous day and taken command of the two Marine divisions. The only other major Allied unit ashore in Kyushu, an Army task force that was occupying Kanoya airfield in the southernmost part of the island, was transferred to General Schmidt’s command from the Far East Air Forces on 1 October. This unit, which was built around a reinforced battalion (1/127) of the 32nd Infantry Division, had been flown into Kanoya on 3 September to secure an emergency field on the aerial route to Tokyo from Okinawa and the Philippines.

General Krueger, well satisfied with the progress of the occupation in the VAC zone, assumed command of all forces ashore at 1000 on 24 September. The first major elements of the other corps of the Sixth Army began landing at Wakayama the next day. On every hand, there was ample evidence that the occupation of southern Japan would be bloodless.

Among the VAC troops, whose previous experience with the Japanese in surrender had been “necessarily meager,” considerable speculation developed regarding:

... to what extent and how, if at all, the Japanese nation would comply with the terms of surrender imposed. ... The only thing which could be predicted from the past was that the Japanese reaction would be unpredictable.32

And it was. In fact, the eventual key to the pattern and sequence of VAC occupation operations was “the single outstanding fact that Japanese compliance with the terms was as nearly correct as could be humanly expected.”33