Chapter 2: Ashore in North China

Target Analysis1

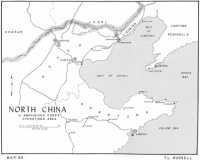

The North China plain encompasses most of Hopeh Province and extends two broad valleys through Shantung, one touching the sea near Tsingtao and the other reaching toward Central China. (See Map 33.) Irregular foothills rising into rugged mountain ranges border the plain, infringing on Hopeh’s boundaries to the north and west and interrupting the lowland in Shantung in the south and east. The plain has long been the invasion route for armies bent on China’s conquest; the Great Wall which separates Hopeh from Manchuria and Mongolia was built to check such incursions. Where the wall touches the sea, a narrow corridor begins which skirts the mountains shadowing the coast until it opens into the Manchuria plain.

In some ways the climate of North China is similar to that in the north central part of the United States. There is a significant range of temperature between the seasons, and the winters are particularly cold, owing to biting winds which whip in from the sea and out of the mountains. Rainfall is light, averaging 20–25 inches the year round, but in North China almost half of that usually falls during two months, July and August. During this rainy season, the many rivers, streams, and canals that lace the plain habitually overflow their banks and flood the countryside. Roads become virtually impassable to any heavy traffic until the end of the rains returns them to their usual dusty state. The frequent dust storms from October through May are a particularly unpleasant feature of the colder weather. There is relatively little snow in winter months.

Any fertile land in the Hopeh–Shantung region is intensely cultivated; fields are terraced high on the hillsides and edge the salt marshes and mud flats that line a good part of the low-lying coast. The staple crops are cereal grains, principally rice and kaoliang,2 augmented by family garden plots. Thousands of farm villages dot the orderly maze of small fields which give a monotonous sameness to the hinterland. Most of the seventy million people living in the two provinces in 1945 were indebted to absentee landlords and, tied to the land, eked out a marginal

Map 33: North China—III Amphibious Corps Operations Area

existence. Many townsmen and city dwellers made their living servicing and exploiting rural market areas. Trade with other parts of China and with foreign lands was funnelled almost entirely through a few large cities which lay along the principal communication routes.

From an economic viewpoint the most important city in North China at the war’s end was its commercial hub, Tientsin. Second only to Peiping in size, with a population swollen by refugees to an estimated million and a half, the city dominated an extensive network of railroads and waterways. Since it had grown to importance only during the past half century, Tientsin was quite modern in many respects. Broad, paved streets and substantial masonry buildings of foreign styling characterized the area of the former international concessions which gave the city its pronounced Western cast. Even the predominantly Chinese quarters shared this appearance of openness, especially when contrasted with the jumbled and warren-like aspect of most older cities.

Although it was 36 miles from the Gulf of Chihli, Tientsin was still China’s most important port north of Shanghai. The Hai Ho (River) and the railroad which paralleled its course from the sea were the means by which a constant flow of goods had reached and gone out from Tientsin in times of peace. An open roadstead off the entrance to the river gave anchorage over good holding ground to ocean-going vessels. Only lighters ,and coastal shipping drawing 14 feet or less were able to negotiate the Taku Bar, a barrier of silt across the river mouth that took its name from a nearby village. Seven miles upriver on the north bank was Tangku, a town which served as Tientsin’s gateway to the sea and as its railhead for transshipment of cargo. River traffic to Tientsin was extensive but confined to craft less than 300 feet in length which could negotiate the restricted turning basin at the city’s wharves.

Tientsin’s airport was about seven miles east of its outskirts near the village of Changkeichuang. The field, which was circular in outline, had three intersecting runways only one of which was paved. The comparatively short landing strips, just a bit over 4,000 feet long, and the poor drainage of the surrounding terrain often faced pilots with the prospect of coming down on a short runway that began in mud and ended in mud. Other air facilities at Changkeichuang Field were comparably limited, and the prospects for heavy use were poor without extensive construction.

In contrast to Tientsin’s one poor airfield, Peiping had two first class military airdromes, each with considerable hangar, repair, and storage facilities. Lantienchang Field, nine miles northwest of the ancient city, had five runways, all shorter than those at Tientsin but in better operating condition. Eight miles south of the city was Nan Yuan Field which the Japanese had used as a training base. Most of its installations, including four runways and a grass infield suitable for takeoffs and landings, were located within a walled oval nearly two miles long and over a mile wide. Located just outside the enclosure was an airstrip a mile and a quarter long

that could accommodate the heaviest transports and bombers.

The excellent air facilities at Peiping were an indication of its strategic importance. The ancient city, China’s capital for nearly 700 years, had a measureless value as a symbol of national power. It was the cultural and educational center of North China as well as its administrative headquarters under both Nationalists and Japanese. More than 1,650,000 people dwelt within its moated walls.

The massive walls of Peiping were the city’s most distinctive feature and gave definition to sections within their bounds. The outer walls made of earth and cement faced with brick were 40 feet high, 62 feet broad at the base, and 32 feet across the top. A deep moat, water-filled in most places, extended all around the city. In general outline Peiping resembled a square set beside a rectangle, the square being the Tartar City, the rectangle the Chinese City. The Tartar City was roughly four miles along each side, while the Chinese City was five miles long and two wide. Towering gates in the outer walls and in the interior wall between the two cities opened into broad and straight thoroughfares. Sharp contrast to these main avenues was offered by the many patternless, twisting side streets and alleys which led off them. Most of Peiping’s residents lived in family or communal compounds which lined the narrow streets.

Centered in the Tartar City to the east of an extensive system of artificial lakes was the Imperial City. Once the home of court officials and China’s leading scholars, the Imperial City completely surrounded the former palace area of the Manchus—the Forbidden City. Within high palace walls were dozens of buildings and courtyards which offered impressive testimony to the richness of a bygone era. The walls of the Imperial City had been razed to make way for roads but its confines were still clearly discernible. In the southeast part of the Tartar City was the walled Legation Quarter, the home and commercial center for a sizeable foreign community. Scattered throughout Peiping were many colorful temples and buildings of the Imperial age which helped make the city an irresistible goal for tourists in peacetime.

Some 475 miles southeast of Peiping was the port of Tsingtao, the smallest of the three North China cities which had populations of over a million. Situated on Kiaochow Bay at the tip of a stout finger of land jutting out from the south shore of Shantung Peninsula, Tsingtao had the best harbor north of Shanghai. Foreign warships, including elements of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, used its port facilities frequently in prewar years, and American naval officers were impressed with its suitability as a forward area base. Tsingtao was built up around several harbors with most of the large scale commercial activity centered on the mile-square Great Harbor in the northern part of the city where deep draft vessels could dock. Extensive rail yards and an industrial area dominated by textile mills were close to Great Harbor’s wharves. Ringing the wide semicircle of shoreline of the Outer Harbor to the south were most of the city’s public buildings.

As befitted its origin as a German leasehold, Tsingtao was laid out in orderly fashion with many Teutonic touches. Indeed, to some observers it “looked like a fragment of the Friesland or Westphalia rather than a Chinese port city.”3 Its streets were wide and paved, and its building% most of them two- and three-stories high, were modern and Western in appearance. From an incoming ship or plane, the most striking aspect of the city was the almost universal color scheme of red tile roofs and white buildings.

Tsingtao was built on the foothill reaches of an isolated cluster of mountains standing to the east of the city. To the north, well drained flatland provided ample room for airfield construction. The Japanese had established two military airdromes in the area and, in addition, had expanded the facilities of the existing commercial airfield. This field near Tsangkou village about seven miles from the outskirts of the city was perhaps the best in North China. It had two main concrete runways with extensive paved taxiways and aprons and repair shops, storage sheds, and barracks adequate to handle a large volume of air traffic. The terrain in the vicinity provided almost unlimited opportunity for expansion.

No other coastal city in Shantung or Hopeh could rival Tsingtao’s natural advantages as a port, but Chefoo, which had the best protected anchorage on Shantung Peninsula’s north shore, had comparable strategic significance in the Chinese civil war. Chefoo was 150 miles due south of Dairen and its possession gave the holder easy access to Manchuria across the mouth of the Gulf of Chihli or the capability of choking off such communication. The city had a war-swollen population of about 200,000 whose main concern was the agricultural life in the surrounding countryside. Chefoo had no rail connection with the interior and only a way-station airfield, but the rural roads leading into it were adequate to service a guerrilla army in all months but the rainy season.

The railroad network that traced its way across the North China plain was of paramount importance in determining the course of events in North China. The key line was the Peiping–Mukden Railroad; connecting and subsidiary lines reached south into Central China and north into Siberia from the terminal cities. At Tientsin the Peiping–Mukden connected with a railroad which led to Tsinan, Shantung’s capital, and thence eventually to Nanking and Shanghai. Tsinan was linked directly to Tsingtao and the sea by rail.

The prize section of the Peiping–Mukden Railroad ran between Tangku and a small coastal town 150 miles to the north, Chinwangtao. The Kailin Mining Administration (KMA), a British-controlled company, had developed Chinwangtao as a shipping point for its coal mines near Tangshan. Coal was the basic fuel for many public utilities and factories throughout China and the output of the KMA mines figured strongly in any plans for economic recovery. Like the KMA, the Nationalist Government was attracted to Chinwangtao by the fact that its wharves and

anchorages were never icebound, and it had rerouted the Peiping–Mukden tracks to go through the town. During a hard winter when the Hai River was frozen over, Chinwangtao served in Tangku’s stead as Tientsin’s port.

The Nationalists, the Communists, and the Japanese were agreed upon the strategic value—and the vulnerability—of the railroads. The Japanese were able to keep in operation only those portions of the rail system that their troops held in strength. Communist guerrillas laid waste unguarded stretches and attacked weak outposts in a ceaseless program of harassment which caused extensive damage to tracks, roadbeds, and rolling stock. The Nationalists moving into North China faced the same problem and planned the same solution as the Japanese. Chiang Kai-shek’s forces would be able to use only as much track as they could keep tightly guarded.

Most Japanese troops in North China at the war’s end were concentrated in rail junction cities and extended along the tracks between. There were 326,000 regular troops in Hopeh and Shantung and in the provinces immediately inland, Honan and Shansi, all under command of the North China Area Army of Lieutenant General Hiroshi Nemoto. Four armies, the First in Shansi, the Twelfth in Honan, Forty-third in Shantung, and the Mongolian Garrison in Hopeh had charge of area defense. In addition to the Japanese units, there were 140,000 Chinese in the puppet North China Pacification Army and an additional 340,000 village and county local defense troops under Japanese charge.

There was a marked absence of heavy supporting weapons in the Japanese Army organizations, which were composed largely of second-line troops formed from service units turned infantry and filled out with recent conscripts. The North China Pacification Army puppet units were even less well trained and equipped and the poorly armed local defense troops were of little military consequence except as manpower reserves.

In the areas where Marines of IIIAC were scheduled to land, approximately 116,000 Japanese regulars were present. In Peiping and its immediate environs were General Nemoto’s area army headquarters troops as well as similar elements of the Mongolian Garrison Army. At Tientsin, Lieutenant General Ginnosuke Uchida, Commanding General of the 118th Division, had charge of 50,000 Japanese who defended the city and guarded the rail lines halfway to Peiping, two thirds the distance to Tsinan, and as far north on the Peiping–Mukden as Chinwangtao. The area commander at Tsingtao, Major General Eiji Nagano, had 15,000 troops, including his own 5th Independent Mixed Brigade.

Communist regular forces in Hopeh and Shantung totaled 170,000 troops with at least that number in addition to partially trained rural militia. Most of the regular units were disposed near the big cities garrisoned by the Japanese, close enough to be troublesome, but far enough out of reach to avoid punitive expeditions. Nationalist strength in the two provinces was negligible, but the influence of Chiang Kai-shek was latent, not absent. Opportunists among local

government officials appointed by the Japanese puppet regime, as well as many puppet troop commanders, saw a more rewarding future in the pay of the Central Government than they did within the austere Communist setup.

The attitude of the puppet soldiers was typical of a traditional and pragmatic approach to warfare in China: “one army is pretty much the same as another.”4 The introduction by the Communists, and to a lesser extent by the Kuomintang, of political indoctrination of the coolie and peasant soldiery brought about a radical change in this feeling, Political propaganda made a potent reinforcement to military power, and its skillful use by the Communists was a significant factor in the course of the civil war. Intelligence officers of III Amphibious Corps, in assessing the difficulties of the task assigned the Marines in North China, concluded that the Communist system:

... permits a policy of expansion and contraction according to need. Their closely-woven network needs neither highways nor railroads owing to Communist independence of the major transportation lines. The process of consolidation in the interim following Japanese capitulation and the arrival of Chungking forces would seem to strengthen their ability to resist the entry of a force to take over from the Japanese. If frustrated in the immediate achievement of their objectives the Communists (unless in the meantime their differences with Chungking are resolved) are prepared to combine political with military warfare for a protracted struggle against any internal or external opponent.5

Advance Party6

While accurate order of battle information on the former enemy forces in North China was available from Japanese sources, details regarding Communist dispositions and intentions were meager. The political situation was unstable, and Chungking was unable to supply reliable intelligence which would give American planners a firm picture of what they might find upon landing. This handicap, however, did not hinder the III Amphibious Corps in compiling a considerable body of geographic information on target areas.

Many officers and senior enlisted men in the IIIAC had served in China in the years of disorder between the world wars.7 Veterans of the Embassy Guard in Peiping and Tientsin, of the 4th Marines in Shanghai, and of the two expeditionary brigades and numerous ships’ detachments landed to protect American lives and property were widely distributed

throughout both air and ground elements. Of the eight general officers in the corps’ new task organization, seven had served at least one tour in China.8 Although the corps commander, General Rockey, had never been assigned China duty, he was fortunate in having a chief of staff, General Worton, who had over 12 years’ experience in the Orient, most of it spent in North China.

Worton and the Corps G-2, Colonel Charles C. Brown, were both qualified Chinese language interpreters and translators. During 1931–1935 the two officers were assigned to the American Embassy at Peiping as language students. Colonel Brown, moreover, had just returned from duty as Assistant Naval Attaché in Chungking before he joined the IIIAC staff. The experience of Worton and Brown was of considerable value in processing intelligence data supplied by CinCPac, and in the planning for the landing, movement when ashore, and billeting of troops.

An up-to-date political-military briefing, even one which was scanty on particulars of the situation in Hopeh and Shantung, was needed. On 22 August a representative of General Wedemeyer’s theater staff, Brigadier General Haydon L. Boatner, arrived on Guam for conferences with Admiral Nimitz. The Army general had known Worton as a fellow language student in Peiping during the ’30s, and he was able to brief the Marine officer on the possible courses of action and the leaders and forces involved in the threatening civil strife. Boatner made a recommendation to CinCPac that the III Corps send an advance party to China to sound out the situation and smooth the way for the projected landings. There was little question that the logical person to lead this party was General Worton, and following Admiral Nimitz’ approval of the proposal, General Rockey made a formal request to that effect to General Wedemeyer. The response was favorable, and a tentative date of arrival in China was set for 20 September, 10 days before the Tientsin operation was to get underway.

General Worton named Colonel Brown as his executive in the advance party and added senior representatives of other corps staff sections. The officers chosen continued to take a prominent part in the intricate planning for the Marine landings, becoming familiar with the problems arising from the amount and type of forces and materiel committed, As a necessary precaution, these plans called for the first men ashore to be assault troops, but on the whole the operation contemplated was noncombat in nature. IIIAC units, standing in for Nationalist troops to arrive later, were to take over garrison duties from the Japanese and get the repatriation process started. Under these circumstances, the basic mission of the corps advance party was to contact Japanese commanders and Chinese officials to arrange barracks and storage facilities in areas where the Americans were to operate.

The actual territory to be occupied by Marine forces expanded considerably as plans evolved. In the initial assignment of objectives to IIIAC by Seventh Fleet, landings at Tsingtao and Tientsin

(including the Taku–Tangku area) were ordered and the possibility of a landing at Chinwangtao was considered.9 By 7 September the attraction of Chinwangtao’s all-weather port status had brought about its addition to northern sector objectives. Peiping was a probable target in Marine plans from their earliest stages despite its lack of formal assignment by higher authorities. Both Generals Rockey and Worton strongly believed that IIIAC would have to occupy the walled city’s airfields in order to ensure the arrival of the Nationalist forces which were to relieve the Marines.

Corps planners were well aware of the threat to peace in North China posed by Communist possession of Chefoo. General Rockey wanted to land a regimental combat team of the 6th Division at the strategically located port to take it over from the Japanese. He proposed this move to General Wedemeyer in mid- September through staff representatives of the China Theater who had visited Guam. On the 16th, theater headquarters radioed that Chiang Kai-shek and Wedemeyer had both approved IIIAC operation plans to include landing an RCT at Chefoo; the new objective was published the following day. In the same message Rockey was given a tentative schedule of arrival of Chinese Nationalist Armies (CNA) in Hopeh and Shantung. He was also informed that all questions relative to the corps move into North China would be covered in discussions after the advance party arrived in Shanghai on 20 September.10

On the recommendation of General Geiger, Colonel Karl S. Day, Commanding Officer of MAG-21 at Guam, was assigned as command pilot for the advance party. As finally constituted, Worton’s group included a field officer from each of the general staff sections and the corps surgeon as well as several junior officers and a dozen enlisted men from the corps staff. No representatives of the divisions or the wing were included since corps was prepared to handle all arrangements for reception of troops and supplies. As a parting promise to the IIIAC commander, Worton stated that he would meet Rockey’s command ship off Taku Bar on 30 September in a KMA tug; if all signs indicated an unopposed landing the tug would be flying a large American flag from its foremast.

Near midnight on 19 September the advance party took off from Guam in three transports, one primarily a fuel carrier. After a stop at Okinawa, the planes flew on to Shanghai, arriving in midafternoon, Worton commandeered a Japanese truck to move the whole party into the city where they put up at hotels. Few American or Nationalist troops were in Shanghai as yet, and the Marines were on their own for the three days they spent there while arrangements were made for the trip north.

On the day after his arrival General Worton reported to the China Theater representative, Major General Douglas

L. Weart, for orders, and saw Ambassador Patrick J. Hurley who was on his way back to Washington for a round of conferences. Neither man could give Worton a clear picture of the current situation in North China, since the Nationalists had just begun to take hold in the cities under Japanese control. They did, however, confirm his freedom of action within the broad bounds of the corps mission. The Marine general fully intended to stretch his permissive authority to arrange for the seizure of “areas necessary to facilitate the movement of the troops and supplies in order to support further operations”11 to include the occupation of Peiping. Even while this discussion was going on, Chungking was approving a revised directive to General Rockey which gave the corps a firmer basis for the Peiping move while still not naming the city as an objective. In the new wording, Rockey could, “for the security of his own forces” and of the major targets assigned to IIIAC, “occupy such intermediate and adjacent areas as he deems necessary.”12

An Army liaison officer and a State Department advisor had been added to the advance party when it took off for Tientsin on 24 September, Colonel Day led his flight up the coast to Shantung Peninsula, across its mountains and on to the mouth of the Hai River, following its course to Changkeichuang Field outside Tientsin. Almost half of the runway was under water, forcing Day to make a very difficult landing and then act as a landing signal officer to bring in the other planes. This first taste of what had been considered a major airdrome made the possession of Peiping’s airfields even more attractive.

The Japanese were waiting for the Marines when they arrived and General Worton was soon set up in temporary headquarters at the Astor House, the city’s principal hotel. After a conference with the North China Area Army’s chief of staff that evening, which indicated that the Japanese were quite ready to comply with any instructions given them, the IIIAC staff officers turned to on the various tasks falling within their areas of responsibility. Arrangements were made with Chinese Nationalist officers to take over Japanese barracks, warehouses, school buildings, and headquarters within the city. Some houses and buildings owned by members of the German community were also requisitioned by the Chinese for American use. Negotiations through consular representatives were made to occupy public buildings in the former foreign concession areas. As a general rule, property of enemy nationals was taken without ceremony, while leases were executed for holdings which were owned by Allied residents or governments. Most of the property selected in the latter category had also been used by the Japanese military forces or civilian community.

General Worton set aside the French Municipal Building, Tientsin’s most imposing structure, as IIIAC headquarters. He also laid claim to the French Arsenal, an extensive barracks and storage compound located on the road to the airfield, for wing headquarters. A reluctance to lease the arsenal on the

part of local French officials was swiftly overcome when the general used the Japanese radio to contact Chungking and get pressure brought to bear by the senior French representative in the Chinese capital. The Italian Consulate, close to East Station of the Peiping–Mukden line, was chosen as the 1st Marine Division headquarters.

As soon as the billeting and storage program was well underway at Tientsin, General Worton flew on to Peiping where he arranged to take over many of Nan Yuan Field’s facilities and to house most of the Marine units within the confines of the Legation Quarter. His State Department advisor was able to smooth the way within the diplomatic corps when any resistance arose to meeting the considerable space requirements of the proposed Marine garrison. As in Tientsin, the property taken over was mainly that seized by the Chinese from Japanese and Germans, or leased from friendly sources in continuation of usage made of it by the enemy. In both cities there were sizeable barracks once used to house troops protecting diplomatic missions following the Boxer Rebellion; these were naturally set aside for troop use.13

Few private owners were reluctant to have the Marines hold their property, even though the leases negotiated were not very profitable. Marine billeting officers could promise that property would be adequately repaired and maintained, and in many cases improved upon.14

Japanese cooperation with the advance party was exemplary. Sullenness and foot-dragging tactics, which could well have been expected, were absent.15 General Worton flew to Tsingtao, Tangshan, and Chinwangtao to confer with local Japanese commanders. Arrangements were made in each place in keeping with the procedures used in Tientsin and Peiping for reception and housing of planned IIIAC garrisons. In Tsingtao the general left Colonel William D. Crawford, an Army officer who was serving in the Corps G-1 Section, to lay the groundwork for the 6th Marine Division arrival. Worton also flew to Weihsien in Shantung, the site of Japanese POW and civilian internment camps, to expedite the release and return to Tientsin of foreign railroad and KMA executives. He was convinced that the economic welfare of a large part of China depended upon the KMA mines getting back into full production.

Shortly after General Worton visited Peiping and indicated by his actions that the Marines intended to move troops there, he received a message that “the people opposed to Chiang Kai-shek”16 would like to talk to him. A meeting was set up that night at Worton’s quarters with the full knowledge of Nationalist authorities. The caller who arrived was General Chou En-lai, the top Communist

representative in wartime truce negotiations between Yenan and Chungking. The substance of Chou’s remarks was that Communist forces would fight to prevent the Marines from moving into Peiping. General Worton in reply told the Communist leader that the Marines most certainly would move in, that they would come by rail and road, and just how they intended to do so. Further, the Marine officer pointed out that III Corps was combat experienced and ready, that it would have overwhelming aerial support, and that it was quite capable of driving straight on through any force that the Communists mustered in its path. The stormy hour-long interview ended inconclusively with Chou vowing that he would get the Marines’ orders changed; it was a grim warning of the clashes to come.

By the end of the week, the advance party had made all the most urgent arrangements for the reception of the incoming corps. They had deliberately established a pattern of direct handling of all local logistic support problems which was to hold throughout the Marines’ stay in North China. There was to be little opportunity for the traditional Chinese “squeeze” that invariably would have marked such operations had they been turned over to middlemen. In this as well as many other respects, the experience of the old China Marines was of incalculable but obvious benefit.

Hopeh Landings17

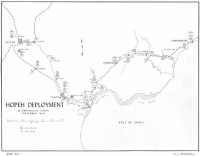

The responsibility for seizing and holding the Tientsin area rested with Major General DeWitt Peck’s 1st Marine Division. (See Map 34.) Although Corps planners recognized that the landing would be primarily a logistical problem, provision had to be made for overcoming resistance. The division designated the 7th Marines, organized as CT-7, as its assault troops. The 2nd Battalion followed by 3/7 was to make the initial landing at Tangku and secure the town for use as the IIIAC main port of entry for Hopeh operations. The 1st Battalion of the 7th was detailed to take Chinwangtao in a separate landing.

Scheduled to follow the assault troops ashore at Tangku was the Assistant Division Commander, Brigadier General Louis R. Jones, and his command group plus detachments of the 1st Pioneer Battalion to perform shore party tasks. One battalion of CT-7 would guard the lines of communication between Tangku and Tientsin while the other secured the port area. The regiment was to be prepared to place a garrison in Tangshan on order and assume responsibility for security of the railroad south to Tangku. At the same time, 1/7 at Chinwangtao would take charge of the Peiping–Mukden line north of Tangshan.

Map 34: Hopeh Deployment

The 1st Marines Combat Team was assigned the mission of occupying the city of Tientsin and Changkeichuang Field. The 5th Marines Combat Team, moving to the target in a transport division arriving a few days after the main convoy, was slated to secure Peiping and its airfields. Tientsin was the projected base for those units of the 11th Marines and division separate battalions that were not attached to infantry regiments. The greatest part of Corps Troops was also scheduled for garrison duty at Tientsin in support of the 1st Division and 1st Wing.

One corps unit, the 7th Service Regiment, was given far-reaching responsibilities that tended to increase and expand as the occupation wore on. Designated as the functional supply agency for all IIIAC ground and air elements in Hopeh, the regiment’s organization was such that it would adapt to rapidly changing conditions of service. Its logistic support companies formed the backbone of the Shore Brigade that corps organized to cope with the formidable problems presented by Tientsin’s geographic situation.

The brigade, which was strictly a temporary organization, operated with a tiny headquarters of seven officers and men under Colonel Elmer H. Salzman. Two FMF units attached to IIIAC, the 1st Military Police and 11th Motor Transport Battalions, together with medical and signal detachments from Corps Troops augmented the elements of 7th Service Regiment which were to process all personnel and cargo coming ashore. The first echelon of the Navy advanced base organization, Group Pacific 13 (GroPac-13), which was eventually to operate the port of Tangku, also came under Salzman. As soon as sufficient components of the GroPac arrived in North China, the Shore Brigade would be disbanded. For the first couple of weeks of the operation, however, General Rockey emphasized that the brigade “must have full authority over all unloading activities and must coordinate all movement of troops, equipment and supplies in the landing area.”18

Much of the concern with the logistic aspects of the Tientsin area operations was generated by the fact that all traffic from ship to shore would have to funnel through the narrow seaward channel of the Hai, across the tide-altered depth of the Taku Bar, and up river to the Tangku piers. Although extensive use of ships’ boats for unloading was planned, the strong possibility was recognized that only landing craft as large as LCTs would be practical for the long run from transport to pier. Since the condition of the river channel and the cargo handling facilities at Tangku was uncertain, plans for landing procedures were flexible enough to be adapted rapidly to the situation existing on 30 September.

The responsibility for embarking and moving the forward echelons of units headed for the Tientsin area, and for all follow-up echelons regardless of destination rested with Rear Admiral Ingolf N, Kiland, Commander, Amphibious Group 7. Under him, the commander of

Transport Squadron 17 (Transron-17), Commodore Thomas B. Brittain, was ordered to load, lift, and land the 1st Division and Corps Troops and to act as Senior Officer Present Afloat (SOPA) at the objective. General Peck would move to the target in Commodore Brittain’s flagship, while General Rockey sailed with Admiral Barbey in the command ship Catoctin. Barbey intended to take the Catoctin to the Tientsin landing and thereafter to whatever point the progress of the operation demanded.

Corps Troops on Guam began loading supplies and equipment on vessels of their assigned transport division on 11 September. Three APAs and an AKA of the division, plus 15 LSMs for the heaviest vehicles and gear, were needed to move the first echelon; the remaining two transports, a cargo ship, and additional LSMs reported to Okinawa to load out the 7th Service Regiment. On 20 September, the day after the IIIAC advance party took off for China, the corps convoy sailed for Okinawa to rendezvous with ships carrying the 1st Marine Division and Headquarters Squadron of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing.

Three of the four transport divisions of Commodore Brittain’s squadron assigned to lift the 1st Marine Division had returned to Okinawa from Korea and begun loading by 18 September. Bulk cargo of rations and fuel was taken on board off the Hagushi Beaches in the center of the island before the ships moved north to Motobu Peninsula and began loading unit equipment and supplies. Separate dumps were set up for each vessel’s load, and ship-to-dump radio contact was maintained to speed cargo handling. Landing craft were used to move light loads on all tides and heavier gear with high water; the amphibious vehicles of 3rd DUKW Company, which were not hampered by shoal water, were in use all around the clock. Much division heavy equipment, particularly that of the engineer and pioneer battalions, was loaded directly into beached LSMs which could move up river without unloading at Tangku. The rail and road bridges between Tangku and Tientsin were none too sturdy, intelligence indicated, and the possibility that they could not be used by bulldozers, tanks, and similar vehicles had to be considered.

All units were loaded for minor combat employment after the movement to North China, but in practice there was a significant difference from wartime combat loading procedures. There was little inclination to leave anything behind on Okinawa that might be useful in China. The very uncertainty of what lay ahead prompted unit commanders to fill all available spaces, cutting down on the hold room needed to work combat cargo properly, and leading in some instances to lack of clear understanding of unloading priorities.19 The hurried acquisition of clothing and matériel to cope with North China’s rugged winter continued right up to the time of sailing and further complicated the loading situation. Winter gear, particularly suitable

clothing, was in short supply for some units until late in 1945.20

In the original concept of the operation, the movement of a battalion landing team to Chinwangtao was deferred until after the main body of troops left for Tientsin, On 19 September, however, planning for concurrent movement began and an APA was detailed to load out 1/7. An LSM carrying a shore party detachment of the 1st Pioneer Battalion and a destroyer escort were scheduled to join the Chinwangtao landing force off Taku.21 Loading of the landing team was finished by 25 September, the same date that all elements of IIIAC at Okinawa completed embarkation.

Both the corps convoy from Guam and three LSTs from Zamboanga with the ground echelon of 1st MAW headquarters on board joined Transron-17 on the 24th. The flight echelon of wing headquarters had flown in on the 22nd to establish a temporary command post on Okinawa. While the Assistant Wing Commander, Brigadier General Byron F. Johnson, stayed with the CP, the wing commander, Major General Claude A. Larkin, planned to board the 1st Marine Division command ship. General Larkin intended to observe the airfield situation at Tientsin first-hand before calling in planes of his groups. The ground echelons of some wing units were already at sea by 25 September, and most of the squadrons were packed and ready to sail. Flight echelons were prepared to stage through Okinawa and Shanghai as soon as the wing declared North China airfields operational.

On the 26th the III Amphibious Corps, less the 6th Marine Division, left Okinawa bound for the Taku Bar. On board the convoy’s ships were nearly 25,000 men, the vanguard of a planned strength of 37,638 scheduled for Hopeh garrisons. Heavy seas and leaden skies attended an otherwise uneventful trip.22 On 30 September, most ships reached their assigned anchorage off the Hai River’s mouth slightly behind the time forecast and Admiral Barbey delayed H-Hour, originally 0900, to 1030. Worried by the rough water and delay in the landing as scheduled, General Rockey considered putting off the landing until the next day, but the arrival of General Worton at the Catoctin prompted him to carry through with the original landing plan.23

The corps chief of staff had sent out several encouraging situation reports after he arrived in North China, and he was able to keep his promise and meet Rockey in a KMA tug flying an American flag that signified that all was well ashore. Worton brought with him the

mayor of Tientsin who requested that at least a token force of Marines reach the city that day. When he and Worton had started down river very early that morning people were already gathering for a welcoming ceremony; a tumultuous reception was planned. Rockey acceded to the Chinese official’s request, which was seconded by Worton, and directed that one battalion of the 7th Marines go straight on through to Tientsin as soon as it landed.

The Navy’s river control organization was getting into operation while General Worton was briefing General Rockey. The long run in from the anchorage to Tangku’s docks—15 miles minimum—combined with rough water over Taku Bar to rule out the use of ships’ landing craft to land troops and supplies. The unloading task was shifted entirely to LSMs, LCIs, such LCTs as could be made available from Korea and Japan, and locally hired Chinese lighters. Control officers in patrol craft were stationed in the rendezvous area off Taku Bar, in the river mouth just over the bar, and at the docks where liaison was maintained with the shore brigade. Loaded craft reported to the rendezvous control, were dispatched to the bar on the approval of the river control at the docks, and assigned to specific docks or beaches by the river mouth control.24

General Jones, the ADC of the 1st Division, with some of his staff, arrived at Tangku via a patrol craft at 1030; the two hours it took him to travel from transport to dock was typical of the time lapse involved in reaching shore. It was 1315 before the initial assault battalion of the 7th Marines, 2/7, reached land after transferring to’ LCIS from its APA. The 2nd Battalion spread out through the port town to establish security for the incoming troops and supplies. The 3rd Battalion, 7th, with the regimental headquarters attached, landed next and immediately boarded a train at the dock railyard for Tientsin. In late afternoon 3/7, which had been greeted by cheering, flag-waving Chinese all the way up the Hai River to Tangku and all along the rail line to Tientsin, stepped off its cars into the thick of an unbelievably noisy and happy crowd of thousands of people.25

The corps advance party had arranged for Japanese trucks to carry the men to their billet, the commandeered racecourse buildings on the western outskirts of the city,26 but progress through the packed streets of the former concessions was kept to a snail’s pace. The utility-clad Marines with full ammunition belts and mammoth transport packs must have looked little like the Marines of prewar years to the Chinese, but their welcome was as fervid as that for a long-lost friend.

Each man in 3/7 had only one day’s ration in his pack when he went ashore,

1st Marine Division troops landing at Taku on 30 September 1945. (USN 80-G-417486)

Tientsin citizens welcome first Marines to return to city since end of war. (USMC 225072)

since his unit, like all others in the corps, had loaded the remainder of the required five days’ rations in organizational vehicles.27 The trucks that should have stayed with the 3rd Battalion according to original plans were left in Tangku when the battalion made its unexpected trip to Tientsin. The lack of food was acutely felt, but members of the advance party were soon able to arrange for locally procured rations.28

The mix-up regarding rations was not uncommon during the first three days of the operation while Tangku port facilities were being adapted to handle the flood of heavy military equipment and bulk supplies directed to shore, One of the greatest problems was getting loaded vehicles off landing craft and onto dry land. The mud bank near the pier selected as a vehicle landing would not support the Marine trucks until hundreds of loads of stone ballast and layers of logs had provided a firm ramp. The high gasoline consumption rate of trucks hauling ballast and struggling through mud to shore resulted in unexpected priority requests from Shore Brigade that complicated unloading procedures. By 2 October, LSMs were proceeding upriver to Tientsin with the heaviest equipment and unloading ramp-to-ramp into LCMs that ferried the cargo to shore. Later, a pontoon causeway was towed up to Tientsin and put into use for unloading the LSMs.29

Corps planners had allowed for the near-certainty that there would be vexing logistical problems in making the landing at Tangku. After the assault battalions had established themselves ashore, the Shore Brigade was given the time to get itself set up and in efficient operation before calling in additional forces. More troops and supplies could have been landed on 30 September, but to no particular useful purpose. As it was, more than 5,400 men and 442 tons of equipment (including 115 vehicles) came ashore the first day. The total of unloading increased rapidly as Tangku’s piers, its warehouses and dump areas, and its freight yard maintained the driving pace dictated by the need to clear Transron-17 ships for further tasks.

Shortly after the first troops had reached the docks, a flying boat carrying Admiral Kinkaid and Lieutenant General George E. Stratemeyer, who was commanding the China Theater while General Wedemeyer was in Washington with Ambassador Hurley, set down near the Catoctin. The two officers immediately were apprised of the favorable situation ashore. In an ensuing conference, the future actions of IIIAC were discussed with Admiral Barbey and General Rockey. A decision made by the Marine commander earlier that day—to proceed immediately with the Chinwangtao landing—was approved; LT 2/7 was underway for its target that evening. The long-planned

movement of Marines to Peiping was at last approved officially. In a joint reappraisal of the corps mission, a decision was made to cancel some of the reinforcing naval units assigned to its task organization. Three of six naval construction battalions,, a fleet hospital, and some GroPac units were dropped from follow-up echelons of IIIAC. This reduction, though minor in nature, was merely the first whittling down of corps strength; the demobilization rush still to come would pare it to the marrow and eventually force it out of existence.

The sea was too rough for Admiral Kinkaid’s seaplane to take off during the first few days of October, and he and General Stratemeyer finally left by land plane from Tientsin on the 3rd. By the time of their departure, the operation was progressing smoothly; the reception of the Marines by the Chinese continued to be vocal and enthusiastic. Most of the unloading problems imposed by the lack of adequate facilities at Tangku had been solved. General Peck had landed with his headquarters group and set up the division CP in the ex- Italian Concession of Tientsin. The 1st Marines, charged with the security of the city, had established headquarters at the British Barracks, and sent guard detachments to the French Arsenal and Changkeichuang Field. On 5 October, the 11th Marines took over the arsenal guard when the artillery regiment’s CP was opened there. The 7th Marines continued to keep its headquarters and one battalion in Tientsin, but moved from the racecourse to billets in the Japanese School in the ex-Russian Concession on the west side of the Hai River.

The detached 1st Battalion of the 7th Marines, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John J. Gormley, began landing at Chinwangtao at 1010 on 1 October. The troops went ashore in four waves of landing craft but found no opposition; instead, cheering townsmen met them at the beaches. Gormley took command ashore with the landing of his last wave. At 1140 the battalion’s transport moved to dockside and began unloading; its holds were cleared by the evening of the next day.30

The situation in Chinwangtao was tense. Closely investing the town were regular and guerrilla forces of the Communist Eighth Route Army; exchanges of small arms fire were frequent. About 1,600 Japanese and puppet troops were in Chinwangtao and another 2,000 were at Peitaiho, a one-time summer resort 10 miles south down the coast.31 The Japanese regulars were ready to leave for Tangshan as soon as 1/7 took over, expecting to surrender there with the main area command. Gormley, however, disarmed the Japanese, pulled the puppet troops off the perimeter defenses where they were constantly harassed by the Communists and replaced them with Marines,32 and arranged to take the surrender of the garrison. Most of the Japanese troops and civilians were dispatched to Tangshan by rail on 3

October, and the formal surrender took place on the 4th. The Communist leaders in the area sent word that they would be happy to cooperate with the Marines, an attitude of friendliness that had a very short life.

The surrender of all the Japanese forces in the Tientsin area, some 50,000 men, was arranged to take place on the morning of 6 October. The Japanese were directed to turn in their arms, equipment, and ammunition and to keep only such supplies as were needed for health and subsistence, Japanese units were to continue their guard duties until relieved by Marines, and those that did surrender were allowed to keep one rifle with five rounds of ammunition for each ten men to safeguard persons and supplies until these could be placed in physical custody of Marine units. The 1st Marine Division was given the responsibility of collecting the Japanese materiel and controlling the surrendered troops. The attitude of the Japanese officers and men was so universally cooperative that most of the administrative and logistical arrangements for care of former enemy forces were left in the hands of the Japanese themselves.33 The Japanese civilians in the area, who were also to be repatriated with their military brethren under the terms of the surrender, followed suit and ran their own community in a disciplined manner which created few problems for the Marines.

The surrender ceremony itself, conducted with considerable formality, took place in the plaza in front of the French Municipal Building, now officially IIIAC Headquarters. General Rockey had assumed command ashore, reporting to China Theater for orders, on 5 October. An honor guard of company strength, the band, and the colors of the 1st Marine Division formed a background to the actual signing. Lieutenant General Ginnosuke Uchida, accompanied by a small representative staff, signed for the Japanese; symbolically, these officers laid down their treasured swords. General Rockey acting in the name of Chiang Kai-shek signed for the Allies. Looking on as official guests were the senior officers of the Marine units in China and representatives of the countries and other armed services who had contributed to the victory. Unofficial American observers lined the windows and roof of the corps headquarters, and the adjoining streets were filled with the citizens of Tientsin. Most appropriately, the Japanese surrender party filed off the plaza to the strains of “The Marine’s Hymn.”

Chinese Nationalist officers, who were beginning to arrive by air in increasing numbers were quite interested in taking the prestige-laden surrender of the North China Area Army. General Rockey, who felt that the Tientsin ceremony

was a necessary and appropriate tribute to his own men, agreed to support this plan for the surrender at Peiping. The first elements of the 92nd CNA to be airlifted to the old capital by American transports arrived on 6 October, and on the following day, a 95-vehicle convoy of the 5th Marines reached the city.

The violent Communist reaction to the Marine move, promised by General Chou En-lai to General Worton, had already made itself evident. Marine reconnaissance parties that went to Peiping in 5 October found a series of roadblocks on the Tientsin–Peiping road that narrowed passage room to jeep width. On the 6th, an engineer group guarded by a rifle platoon of the 1st Marines attempted to remove the roadblocks. They were fired upon by an estimated 40–50 troops at a point 22 miles northwest of Tientsin and withdrew to the city after a short firefight. Three Marines were hit and at least one of the attackers was struck by return fire. The engineers returned to their task the following day escorted by a platoon of tanks, a rifle company of the 1st Marines, and a covering flight of carrier planes.34 The roadblocks were removed without incident, allowing the 5th Marines’ vehicles to reach Peiping safely before nightfall.

The 5th Marines transport division had arrived off Taku on the 2nd and begun discharging cargo on the 5th and troops on the 6th.35 By this time almost all corps and division troops in the forward echelon, except the unit ship platoons left on board to unload cargo, were ashore. The LSTS of the 1st MAW Headquarters Squadron laid alongside the docks at Tangku on the 7th and began unloading.

When the CP of the wing shifted from Okinawa to Tientsin at midnight on 6 October, following the arrival of the first planes from wing and MAG-24 and -25 at Changkeichuang Field,36 all but one of the major unit headquarters of Expeditionary Troops were ashore and in operation. The convoy carrying the 6th Marine Division was at sea proceeding to its objectives, but the Chinese Communists had already beaten them to one. Rear Admiral Thomas G. W. Settle, commanding a cruiser force which had put into Chefoo harbor, reported that the Japanese had evacuated the city and the Communists had seized it and were ill-disposed to any suggestions that they hand over control to anybody else. Admiral Kinkaid requested General Rockey to proceed to Chefoo with Admiral Barbey and investigate the advisability of landing Marines there in light of the altered situation. Immediately following the surrender ceremony in Tientsin, the two commanders boarded the Catoctin and headed for Chefoo. (See Map 33.)

Shantung Landing37

The Catoctin dropped anchor in Chefoo city harbor in midmorning of 7 October under the protective guns of Admiral Settle’s flagship, the cruiser Louisville. Two days of conferences on ship and ashore took place between the local Communist military and political officials and the senior American officers. Barbey and Rockey saw numerous Communist troops in the port and were told by their leaders that any attempt by the Nationalists to land with or after the Marines would be opposed.38 The implication was clear that a Marine landing at Chefoo would not mean the liberation of a Japanese-held city but rather a partisan act for the Nationalists in the civil war. Under these circumstances, as the corps commander wrote shortly afterwards to the Commandant of the Marine Corps:–

Admiral Barbey and I both felt that any landing there would be an interference in the internal affairs of China; that it would be bitterly resented by the Communists and that there would probably be serious repercussions. Although the opposition would not have been very serious, there was apt to be some fighting, sabotage and guerrilla warfare. Upon our recommendation, the landing was cancelled.39

After he received a dispatch recommendation from General Rockey on 8 October, General Stratemeyer conferred with Chiang Kai-shek and then radioed approval.40 The China Theater deputy commander also suggested that the Chefoo landing force be sent ashore at Tsingtao.41 Word of the change in operation orders was passed to the 6th Marine Division on the 9th when its convoy was two days out of Tsingtao.

The cancellation of the Chefoo operation was not much of a surprise to Major General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., the 6th Division commander. General Rockey had warned him as early as 4 October that the presence of Communist troops might make it inadvisable to land Marines there. The division billeting plan issued the next day made tentative provision for the accommodation of the Chefoo landing force, the 29th Marines, in buildings in Tsingtao.

Before Chefoo was written off as an objective, the planned Tsingtao ground garrison consisted of the 6th Marine Division, less two of its rifle regiments, with sufficient supporting units to enable General Shepherd to perform his mission of securing the city and Tsangkou Field. Tsangkou, which was projected as the aerial port of entry for North China, was designated the home base of MAG-32 and of Marine Wing Service Squadron 1, which was to operate a processing center for all aviation personnel entering or leaving the area. Operational control of Tsangkou-based squadrons rested with General Larkin as wing commander rather than General Shepherd as area commander.

The 6th Marine Division’s mounting out for China was an orderly and uneventful procedure as befitted the veteran status of the troops and naval elements involved. Transport Squadron 24 under Commodore Edwin T. Short assembled at Guam after its transport divisions had helped move occupation forces to Japan. Loading began on 23 September when the IIIAC convoy had cleared the island, and on the 29th the transports carrying the 29th Marines sailed to Saipan to relieve congestion in the loading area. The transron reassembled at sea on 3 October and sailed on past Okinawa for Shantung. On board the ships were 12,834 men of the landing force and 17,038 tons of supplies, including 1,333 vehicles.

Taking advantage of the delay in the Tsingtao operation caused by the shortage of shipping, General Shepherd had sent an advance party led by Colonel William N. Best, the Division Quartermaster, to China with the 1st Marine Division. Best was directed to proceed to Tsingtao and to “take all possible steps to insure orderly and efficient arrival, discharge, and billeting of the division.42 On 7 October, General Shepherd followed up his advance party and transferred with a small staff to the destroyer escort Newman in order to reach Tsingtao a day ahead of Transron 24. The general wanted to check the situation ashore and explore the possibility of canceling the planned assault phase of the operation and proceeding without delay to general cargo discharge over Tsingtao docks.

A typhoon which struck the Okinawa area on 8 October caught the ships of Transron 24 in its lashing edge, Rough seas slowed the convoy to such an extent that Commodore Short had to delay the landing date 24 hours. Toward the center of the furious storm, waves as high as 40 feet and winds that reached above 100 knots tore at the LSTs carrying the ground echelons of wing units to Tsingtao and Tangku. The turbulence was so great that the main deck of one landing ship split and it had to return to Okinawa for repairs.

The havoc wrought by the typhoon at Okinawa was even greater than it was at sea. Winds with gusts that destroyed measuring instruments swept across Chimu Field where planes and gear of 1st MAW squadrons were parked waiting on clearance for the move to China. The extent of the material damage was hard to believe; every plane in VMSB- 244 and VMTB-134 was unflyable when the high winds abated on the 10th. Resupply

stores, personal baggage, and unit equipment were scattered and torn apart. The flight echelons of MAG-32 squadrons, working around the clock, performed a miracle of reconstruction on their battered ships. Searching out needed tools and materiel in dumps and storeships throughout the island and its anchorages, improvising and even improving as they made repairs, the pilots, gunners, and ground crews had their planes airborne within a week.43

Weather is no respecter of person, and the typhoon that struck Okinawa gave General Shepherd, on board the Newman, “his roughest experience at sea.”44 All hands were thankful to see the hills of Tsingtao come up on the horizon on the morning of the 10th, and enjoy the prospect of setting foot on the ground again. Alerted by Colonel Best, the mayor of the city and a delegation of local officials met the general when he landed. Billeting preparations were well in hand, and the cooperation of the Japanese garrison was exemplary. Shepherd decided that there was no need to land assault battalions to secure the wharves prior to the main landing.

Admiral Kinkaid flew in from Shanghai on the 10th, shortly after the Catoctin arrived from Chefoo, and broke his flag on board the command ship. Generals Rockey and Shepherd and Admiral Barbey discussed the China situation with the Seventh Fleet commander, and reviewed the difficulties inherent in their instructions to cooperate with the Central Government forces while avoiding any collaboration with the Communists. The schedules for arrival of the rear echelon of IIIAC units and for the initiation of repatriation of Japanese soldiers and civilians came under consideration. Since the JCS had stated that it was U.S. policy to assist the Chinese Government in establishing its troops in the liberated areas, particularly Manchuria, as rapidly as possible,45 both the movement of follow-up echelons and the progress of repatriation hinged upon the extent to which American vessels were used to move Nationalist armies. Ships of Transron 17 were assigned to transport the 13th CNA from Kowloon to Hulutao and the 8th CNA from Kowloon to Tsingtao; and as soon as Transron-24 cleared its holds, it was to pick up the 52nd CNA at Haiphong and take it to Dairen.

Commodore Short brought the 6th Division convoy into Kiaochow Bay on the 11th under a continuous cover of carrier air launched from ships of TF 72 which were keeping station at sea just off the Shantung coast. The standby air and naval gunfire support programmed for both the northern and southern sector landings had not been used, but both objective areas were well accustomed to flights of Navy planes overhead by the time the troops came ashore. The aerial show of force over Tsingtao was but one of a progression that had begun when the Fast Carrier Task Force first sailed into the Yellow Sea in August. Every city and town on the Marine occupation schedule and the countryside for many

Navy carrier planes in a “show of force” flight over Peking with the Forbidden City in the background. (USN 80-G-417426)

Repatriated Japanese soldiers salute American flag upon boarding LSTs returning them home to Japan. (USN 80-G-702992)

miles around had been made aware that the American combat aircraft supported the occupation. A good part of the task of 1st MAW squadrons would be to continue the surveillance and show of force flights started by the Navy carrier planes, which were calculated to impress the Japanese and cause the Communists to take heed.

After he had received the latest hydrographic information and arranged a docking schedule that suited the altered 6th Division landing priorities, Commodore Short brought his first transports into Great Harbor and authorized unloading to begin. The first unit over the side was the 6th Reconnaissance Company which landed at 1430 and boarded Japanese trucks provided by the advance party. These men got the initial taste of Tsingtao’s welcome to the division, and found it to be fully as loud, enthusiastic, and memorable as that which had greeted the first Marines to enter Tientsin. The reconnaissance outfit threaded its way through the crowded streets and out past the city outskirts to Tsangkou Field where the Japanese guard was relieved.

Other elements of the division disembarked and moved to their billets on schedule, with the 22nd Marines, which had been detailed as assault troops in the original scheme of maneuver, leading the way. The 22nd moved into Shantung University Compound, a considerable collection of buildings which was also to house part of the 29th Marines and the 6th Medical Battalion. The Japanese girls’ high school set aside as the barracks of the 15th Marines was gutted by fire on the night of the 10th. Subsequent investigation showed this to be an act of arson by the school’s caretaker without the sanction or encouragement of Japanese authorities. The Marine artillerymen moved instead into an old set of barracks built by the Germans and into another school. Most of the remainder of the division was billeted in Japanese schools also; the tank battalion occupied Japanese barracks near the tank and vehicle park which was established on open ground near the racecourse. The 6th Marine Division CP opened at the former Japanese Naval Headquarters Building on the shore of the Outer Harbor on the 12th; General Shepherd took command ashore reporting to IIIAC for orders on the 13th. All troops were off their ships by the 16th and the transron sailed the following day.

Admiral Kinkaid had stayed at Tsingtao just long enough to see that the operation was proceeding smoothly and then had flown out. On the 12th, the Catoctin followed suit and upped anchor for Chinwangtao with General Rockey still on board. The IIIAC commander and Admiral Barbey wanted to investigate the situation at the KMA port town, particularly with regard to the potential danger posed by the strong Communist forces in the vicinity. Seemingly, after the decision not to land at Chefoo was announced, the Communist leaders ordered a temporary respite in their harassment of the Marines. A Communist general in civilian clothes even called at corps headquarters in Tientsin to apologize for the attack on the road patrol.46 But the lull was only fleeting

while attempts were made to sound out Marine commanders on their attitudes.

General Shepherd was approached by an emissary of the Communist commander in Shantung on 13 October with a letter that offered to assist the Marines in destroying the Japanese and puppet forces and in policing Tsingtao. It called attention to the fact that the Nationalist Army was going to land at the city under the protection of the Marines in a move that was sure to bring open war in Shantung; despite this, the Communist general hoped that his force and the Marines could still cooperate. General Shepherd carefully prepared a point by point reply and dispatched it by the same emissary on the 16th. The Marine commander pointed out that the mission of his division was a peaceful one and that it could not and would not cooperate in any way to destroy Japanese or Chinese forces. The city of Tsingtao was also peaceful, he noted; and should any disorders arise, “my Division of well-trained combat veterans will be entirely capable of coping with the situation.”47 Shepherd then stated that the movement of Nationalist troops into Tsingtao was a factor beyond his control, but that he could promise that the 6th Division would not take the part of either side in armed conflict. In the face of the Marine general’s determination to carry out his orders to cooperate with the National Government and to avoid assistance to Yenan’s forces, the Communist commander could make no headway.

If there ever was a time when the Communist Eighth Route Army and the Marines could have coexisted peacefully, it was in early October 1945. This chance, however slim, was soon thrown away with the outbreak of a series of harassing attacks against the 1st Marine Division units guarding the communication routes in Hopeh. In the 6th Marine Division zone, the more usual form of harassment became small arms fire against low-flying reconnaissance aircraft.

The first Marine squadron to establish itself at Tsingtao was VMO-6. On 12 October, its 16 light observation aircraft (OYs) flew into Tsangkou Field from the escort carrier Bougainville which had transported the squadron from Guam. Although the 1st Wing had administrative responsibility for VMO-6, operational control was assigned by corps to the 6th Division; a similar setup involving the 1st Division and VMO-3 applied in the Tientsin area. While the OYs’ principal tasks would be liaison and surveillance flights for ground units, their ability to land and take off from makeshift airstrips also ensured their use for retrieving downed airmen.

The flight echelon of MAG-32 arrived at Tsangkou Airfield on 21 October amidst the preparations of the ground crewmen to get set up for extensive aerial operations. General Shepherd was anxious that regular reconnaissance flights over the interior of Shantung be made to report on the activities of the Japanese and of the Communists. He made an oral request to that effect; and on 26 October, the torpedo and scout bombers of the group began flying over Chefoo and Weihaiwei, the mountains of the Shantung Peninsula, and the

railroad leading into Tsinan, headquarters city for the Japanese Forty-third Army garrison.

The Japanese troops that were in the immediate Tsingtao vicinity, those controlled by the 5th Independent Mixed Brigade, were fortunate since their repatriation was assured. Before the other units of the Forty-third Army, strung out along the rail line and quartered in the provincial capital, could count on heading home, they would have to wait relief by Nationalist units. Most intelligence sources indicated that the relief could well be a bloody one. Communist troop dispositions along the vital railroad promised a battle to CNA forces attempting to reach Tsinan.

Major General Eiji Nagano, the local Japanese commander in Tsingtao, was directed to surrender his troops to General Shepherd on 25 October. Admiral Barbey, General Rockey, and a. gathering of distinguished official guests were invited to witness the ceremony; General Shepherd asked Lieutenant General Chen Pao-tsang, Deputy Commander of the Nationalist Eleventh War Area, to sign as Chiang Kai-shek’s personal representative. The entire 6th Marine Division, less the 4th Marines still in Japan, was also a witness. On the morning of the 25th, more than 12,000 men marched on to the oval infield of the Tsingtao racecourse and formed in company and battalion mass columns. To their front, on a raised platform erected for the occasion, General Nagano and the Allied commanders signed the surrender documents. The Japanese general and his staff then laid down their swords, a gesture of defeat of tremendous significance to them. Division military police escorted the former enemies from the field to close the proceedings.48

Consolidation Phase49

The 6th Marine Division settled into a garrison routine with relative ease. The potential for trouble was strong in view of the impoverished thousands of jobless refugees who jammed the poorer sections of the city and overflowed into a miserable collection of shacks and cave hovels on its outskirts. A rash of thievery and mob action broke out from these slums. Directed against German and Japanese households, it occurred within a week of the Marine landing. The local police seemed powerless to prevent the outrages, but squad-sized patrols of the 22nd and 29th Marines soon restored order. While the mob violence abruptly ceased with the advent of Marine street patrols, the threat of its renewal remained. General Shepherd’s prompt action in bolstering civil authority had its desired effect, however. It dispelled any idea that may have existed in the minds of the people of Tsingtao, or of the watching Communists, that the 6th Marine Division was just a show force.

The division’s rear echelon arrived from Guam on 28 October. On the same date naval units needed to operate Tsingtao’s port as an advance fuel and supply base for the Seventh Fleet began

unloading. By the month’s end, the ground portion of the city’s American garrison was firmly established.

At Tsangkou, aerial activity was greatly increased over that originally planned by the decision to base MAG-25 as well as MAG-32 at the field. The deficiencies of Changkeichuang Field at Tientsin for extensive use by either fighter or transport aircraft persuaded General Larkin to switch the transport group’s home station. The group service squadron was diverted to Tsingtao while it was still at sea en route from Bougainvillea, and the flight echelon began ferrying men and equipment to Tsangkou on the 22nd. From the moment the group’s two transport squadrons, VMR-152 and -153, arrived in China they were heavily committed to support the III Corps. Regular passenger and cargo runs to Shanghai, to Peiping, and to Tientsin were scheduled. In addition, special missions were flown as the situation required; in mid-October Marine transports were used to evacuate the Allied internees at Weihsien after Communist troops cut the railroad south to Tsingtao. The two night fighter squadrons of MAG-24, VMF (N)-533 and -541, set up at Nan Yuan Field outside Peiping without incident. The group’s ground echelon, which moved to the target in company with that of MAG-32, had been battered by the typhoon off Okinawa but came out of the storm with no crippling damage.50 MAG-24’s first regular flight operations began on 17 October as the ground echelon was unloading at Tangku.

The rest of Peiping’s complement of Marine planes, the Corsairs of MAG-12, staged through Tsangkou to Lantienchang Field on 25 October. Since the group’s ground elements were still at sea at the end of the month, effective operations of its fighter squadrons, VMF-115, -211, and -218, waited upon their landing. For the most part, however, the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing was ashore and in service by 30 October. On that date, General Larkin, whose failing health would not allow him to remain in China, was detached to return to the States.

The new wing commander, Major General Louis E. Woods, who had led the 2nd Wing at Okinawa, arrived at Tientsin on the 30th and assumed command the following day.51 By this time, his planes had relieved the carrier aircraft of TF 72 of all supporting missions flown for IIIAC. The reconnaissance and surveillance flights requested by ground commanders were now all the responsibility of 1st Wing squadrons. The Marine pilots also inherited the dubious privilege of being fired upon by Communist riflemen and machine gunners who took exception to their presence overhead, No return fire was authorized without permission of higher headquarters, and the sporadic shots went without the repayment that the flyers dearly wished to

make.52 Instead, minimum altitudes at which scouting flights were made were steadily raised to lessen the risk to plane and crew.

The Communist troops who fired at Marine planes seemed equally attracted by Marine-guarded trains. Regularly throughout October., pot shots were taken at trains on the Peiping–Mukden line as they rattled by, and the Marines returned fire if any targets could be seen. On 18 October, six Communist soldiers were killed in the act of firing on a train running between Langfang and Peiping, but for the most part the shooting on both sides was without visible result. Jeep patrols in the vicinity of Marine positions were also fired upon by concealed riflemen and three men were wounded in such incidents through 30 October.

The Tientsin–Peiping road, site of the first clash in China between Communist troops and Marines, broke out in a fresh rash of roadblocks on 15 October and succeeding nights. This activity soon ended, however, when word was passed to farmers along the route that the next ditch dug across the road would be filled in from the nearest field.53 Patrols of the 5th Marines roamed the road as far south as Ho-Hsi-Wu, the halfway town below which the 1st Marines zone of responsibility began. Along the rail line between the two cities, Langfang was the limiting point and a small detachment of the 5th occupied the station there.

A subordinate command of the 1st Division, Peiping Group, under the ADC, General Jones, was established to control Marine activities in the capital. Only two battalions of the 5th Marines, the 2nd and 3rd, were part of the Peiping Group. The 1st Battalion was attached to the 11th Marines which had security responsibility for the stretch of road, rail, and river between Tientsin and Tangku. The infantry battalion was assigned to Tangku, guarding the enormous dumps of ammunition and supplies that were building in the area.

Although Tientsin was the supply center for IIIAC units in the northern sector, Tangku was developed as the major storage area to prevent unnecessary transshipment of materiel unloaded at the docks along the river. On 15 October, the Corps Shore Brigade was disbanded and the 7th Service Regiment took over its duties; GroPac- 13 and the 1st Pioneer Battalion were placed under its operational control. At Tsingtao,, a provisional detachment of 7th Service was activated with the landing of the 6th Division to support Marine activities in the south. The service regiment was officially designated the responsible and accountable supply agency for all organized and attached military and naval units of III Corps in North China on 21 October.

The dispositions of 1st Marine Division troops in the Tientsin area remained throughout October much as they were just after the landing. Most of the division’s strength was concentrated in cities and major towns where their presence acted as a strong deterrent to mob action. When raging crowds of Chinese attacked Japanese civilians

in Tientsin on 13 October, riot squads of the 1st Marines waded into the fighting to rescue the Japanese and quickly quelled the disturbances before serious damage was done. Here, as in Tsingtao, the city’s unruly element was given a sharp warning that the Marines would act strongly to prevent disorder whenever local authorities failed to do so.

General Peck was in no hurry to expose his men in small and vulnerable guard detachments along the Peiping–Mukden line.54 As a consequence, the Japanese continued to outpost the bridges and isolated stretches of track between Chinwangtao and Peiping during October. Disarmament of Japanese troops within the garrison cities occupied by the Marines was effected smoothly with minimum supervision by American forces. The concentration point for the Japanese in the 1st Division zone was their North China Field Warehouse five miles southeast of Tientsin on the Tangku road; the details of feeding, housing, and processing thousands of soldier and civilian repatriates were all handled by Japanese officials acting under the direction of a handful of Marines. The extent of the repatriation problem facing the 6th Division at Tsingtao and the 1st at Tientsin was revealed by North China Area Army officers who estimated that there were 326,375 military and 312,774 civilians in North China who would have to be sent home. The first reduction from this vast total was made on 22 October, when 2,924 civilians and 436 military patients boarded a Japanese ship at Tangku and left for Japan.