Chapter 4: Abortive Peace Mission

Executive Headquarters1

When General Marshall arrived in China on 20 December, he immediately began a series of informal conferences with Nationalist and Communist leaders. Both sides appeared anxious to bring an end to the fighting and to have Marshall act as the mediator in their discussions. Consequently, the American was asked to be the presiding member of a three-man committee whose task was the development of a workable truce plan. The Nationalist representative was General Chang Chun; speaking for the Communists was General Chou En-lai.

The Committee of Three, as it soon came to be known, first met on 7 January at the American Ambassador’s residence in Chungking. The result of six long meetings spaced over the next three days was an agreement which ordered the cessation of all hostilities by 13 January, an end to destruction and interference with lines of communication, a partial suspension of troop movement, and the formation of an Executive Headquarters to police the truce.

The agreement was issued on 10 January over the signatures of the two Chinese members of the Committee of Three and was addressed to “all units, regular, militia, irregular and guerilla, of the National Armies of the Republic of China and of Communist-led troops of the Republic of China.”2 In modification of the ban on troop movement, both forces were allowed to make essential administrative and logistical moves of a local nature. The Nationalists, in addition, won agreement for their continued advance within Manchuria to restore Chinese sovereignty, and acknowledgement of their right to continue troop shifts necessary to complete army reorganization in the area south of the Yangtze River.

The Executive Headquarters provided for in the truce agreement was to be established in Peiping with its actions governed by three commissioners, a Nationalist, a Communist, and an American, with the latter the chairman of the organization. General Marshall appointed U.S. Chargé d’Affaires Walter S. Robertson as the American commissioner. His opposite numbers were Major General Cheng Kai Ming of the Nationalist Ministry of Operations and General Yeh-Chien-Ying, the Communist Chief of Staff. Three independent

signal systems were authorized to enable the commissioners to keep in constant and secret contact with their superiors. The commissioners had the authority to vote and negotiate among themselves, but all orders issued had to have unanimous agreement. The agency through which these orders would reach the field was the Executive Headquarters Operations Section.

The Committee of Three determined that an American officer should be the Director of the Operations Section and that he should have equal numbers of Nationalist and Communist representatives on his staff, as well as enough Americans to carry out the tripartite concept in negotiations. The U.S. Military Attaché at Chungking, Brigadier General Henry A. Byroade, was selected for the post of director. General Byroade’s main concern with the immediate problems involved in maintaining the cease-fire. Field teams, each one a miniature Executive Headquarters in organization, were to be dispatched to areas where fighting continued or broke out anew. The teams were expected to supervise the carrying out of the terms of the truce and to fix responsibility for failure to comply with them.

The initial contingent of officers and enlisted men assigned to Executive Headquarters arrived by air at Peiping on 11 January. A steady procession of Army Air Forces transports, shuttling from fields at Shanghai and Chungking, brought in additional personnel and supplies. Priority in the airlift was given to communications equipment. On the 12th and those days immediately succeeding, radio operators repeatedly sent out the cease-fire order. Byroade’s section set up operations in the buildings of the Peiping Union Medical College on 14 January and immediately made preparations to send its first teams into the field to check reports of cease-fire violations.

Support of the Executive Headquarters made heavy demands upon the aircraft availability of the Army’s Air Transport Command at Shanghai. On 15 January, a detachment of transports from MAG-25 was temporarily assigned to Peiping to increase the number of planes available to fly truce teams to trouble spots and keep them supplied on a regular schedule. The Marine planes were also used to drop leaflets incorporating the cease-fire message in areas where fighting continued. Fighters of MAG-12 and -24 flew special reconnaissance missions over Jehol Province in Manchuria to report on Communist troop movement for the Executive Headquarters.3

The fighting subsided in the first weeks after the publication of the truce agreement. The field teams sent out from Peiping were able to localize clashes between the two sides and to get a start on restoration of normal railroad communications. One result of the operations of Executive Headquarters was an immediate step up in the tempo of Japanese repatriation. The former enemy soldiers and civilians isolated by Communist action in the interior of North China were at last able to march and ride out to the embarkation ports. The continued presence of large numbers of Japanese in the disputed area was a

factor which seriously affected the chances for peace, and the truce teams were directed to take an active part in arranging their withdrawal. In coordination with the Central Government and China Theater, Executive Headquarters determined the priority and method of movement of repatriation groups and arranged to feed, house, and transport them.

With the advent of the truce, Generals Marshall and Wedemeyer were able to prod the Central Government into taking over complete responsibility for Japanese repatriation from China. This decision was in keeping with a directive from the Joint Chiefs of Staff which limited future participation in the program by China Theater forces to advisory and liaison duties. All Japanese personnel, supplies, and equipment were to be released to Nationalist control. Word of the impending change was circulated by IIIAC on 3 January, and the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions were directed to work out turnover procedures with officials of the Eleventh War Area. The switch began in Shantung on the 14th and in Hopeh on the 18th, Responsibility for the Japanese themselves was assumed immediately and the transfer of property was completed by 9 February.4

In the absence of Communist obstruction, an important factor influencing repatriation progress was the availability of shipping. In mid-January, a conference of the Pacific commands most concerned with the repatriation problem was held at Tokyo to determine shipping allocations and scheduling for the overall program. The burden of the transportation task involved in returning the more than 3,000,000 Japanese still overseas had to fall on Japanese-manned ships operated by SCAJAP (Shipping Control Administration, Japan). The requirements of naval demobilization had already made serious inroads in the number of American-manned vessels available, and in immediate prospect was the end to the use of American crews. Several hundred Liberty ships and LSTs were to be turned over to SCAJAP and sailed by Japanese seamen to supplement the captured merchant vessels already in use. The conference decided that China Theater should have the use of 30 percent of this merchant shipping, and that 100 SCAJAP Libertys and 85 LSTs would be made available in February and March for the China run. By utilizing the crew space in the LSTs for passengers, SCAJAP planned to carry 1,200 repatriates in each vessel rather than the 1,000 lifted in similar American-manned ships. The use of such measures, added to the fact that SCAJAP shipping could not be diverted to transporting Nationalist troops to Manchuria, enabled General Wedemeyer to predict that Japanese repatriation from China would be completed by the end of June.

The scheduling of Korean repatriation, a necessary consideration in those areas where the Japanese had held control, was also taken up at the Tokyo conference. The economic competition of the Koreans overseas, who were mainly laborers and artisans, made them unwelcome to native populations. Most

Koreans clamored to return home, and their agitation posed a particularly difficult problem in Japan proper where their number ran into the hundreds of thousands. Priority of shipping space was assigned to the movement of Koreans from Japan, but enough vessels were diverted to Shanghai, Tsingtao, and Tangku to allow 10,000 of the most destitute Koreans in China to leave during late January and early February.

In January, the last month in which any substantial lift by American vessels was available, 57,719 Japanese and 1,838 Koreans left North China. In the following month, 4,000 more Koreans and 43,635 Japanese were repatriated. most of the latter on SCAJAP LSTs. March saw a significant change, however, when the SCAJAP program got into full swing, and 142,235 Japanese repatriates cleared Tsingtao and Tangku. The encouraging progress confirmed General Wedemeyer’s estimate for a June end to the entire program.

During most of the period of Nationalist responsibility for repatriation in North China, American participation in the process went beyond the advice and liaison stage contemplated by the JCS. As soon as the Marines turned over security and inspection duties to Chinese forces, a distinct slackening in the standards of treatment of the Japanese was apparent. China Theater headquarters was deeply concerned by a rash of incidents of unchecked mob violence against the repatriates moving to the coast and of the looting of their meager belongings during the processing at ports of embarkation. After an investigation of the circumstances of these outrages, theater headquarters determined that American supervision of Chinese repatriation procedures was necessary. On 15 February, III Corps was directed to extend supervisory assistance to Nationalist repatriation agencies during staging, movement and loading of the Japanese. The imposition of partial control by the Marines had the desired effect of stemming further disorder in IIIAC sectors of responsibility.5

Reduction of Forces6

Hard on the heels of the assumption of responsibility for repatriation by the Nationalists came a decision by General Marshall to authorize a 20 percent reduction in strength of all Marine units in China.7 The presidential representative’s mission and authority were such that he effectively controlled American forces, although he ordinarily confined his directives to the policy level and did not interfere with operational routine.8 His decision was welcomed by Headquarters Marine Corps, since the task of maintaining a strength level of 45,000 officers and men in IIIAC seriously threatened the planned demobilization

schedule for the whole Marine Corps.9

The strength cut sanctioned by General Marshall gave the Marine Corps an opportunity to revamp its forces in North China in the planned postwar pattern of FMFPac. On 14 February, IIIAC issued its operation plan for the reduction, directing that its major components reorganize according to new peacetime (G-series) tables of organization. Missions were redefined and provision was made for the redeployment necessary to give effect to the plan. Subordinate units had prepared their own plans by the end of February to fit within the framework of action outlined by corps. March was slated to be the period of greatest activity since shipping to take home 12,000 Marines was due to arrive at Tangku and Tsingtao during the month.

Two of the supporting FMF battalions which landed with III Corps were dropped from the troop list under the reduction plan, with the companies of the 1st Military Police to be disbanded in Tientsin and those of the 11th Motor Transport to be returned to the States. The 1st Separate Engineer Battalion lost one of its three engineer companies but remained in China, Corps Troops was reorganized as a Headquarters and Service Battalion (Provisional) with companies replacing the former signal, medical, and headquarters battalions.

The widespread logistics activities of 7th Service Regiment did not permit much paring of its personnel strength but it was directed to reorganize along lines established by the Service Command, FMFPac. Support functions were consolidated in a smaller and less specialized number of service companies. In a move separate from but complimentary to the corps reorganization plan, the regiment’s detachment at Tsingtao was replaced on 19 April by the 12th Service Battalion. The battalion, which came north from Okinawa, reported to 7th Service Regiment for operational control for a short while and then became an integral part of the Marine command at the Shantung port. Stock control remained with the service regiment.10

The conversion of the 6th Marine Division to a brigade, anticipated well before the issuance of the corps operation plan, was directed to take effect by 1 April. The reduced regimental headquarters of the 4th Marines which arrived in Tsingtao from Japan on 17 January formed the core of the new unit. A new regimental Headquarters and Service Company was organized and the Weapons Company of the 22nd Marines was redesignated the Weapons Company of the 4th. By the same order, 2/29 became 1/4, 2/22 changed to 2/4, and 3/22 was redesignated 3/4. The artillery battalion of the brigade was formed from the 4th Battalion, 15th Marines. The brigade’s headquarters battalion was organized from signal, tank, assault signal, medical, and headquarters companies drawn from comparable division units. The service battalion drew its companies from the

division engineer, pioneer, motor transport, and service battalions. The 32nd and 96th Naval Construction Battalions which had been attached to the division now became a part of the brigade organization. On 26 March all remaining units of the 6th Marine Division were disbanded, and on 1 April the 3rd Marine Brigade came officially into being.

The changes ordered for the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing were far less sweeping. Flight activities in the Peiping area were consolidated at South Field (Nan Yuan), leaving West Field (Lantienchang) to U.S. Army Air Forces transports supporting Executive Headquarters. The Headquarters and the Service Squadrons of MAG-12 were ordered to the States and with them went VMTB-134 and VMF(N)-541. The fighter squadrons of MAG-12 were transferred to MAG-24. Air unit withdrawals were completed by early April.11

The reduction in strength of the 1st Marine Division was accomplished primarily by disbanding the third battalions of each of its infantry regiments and one firing battery from each of the four battalions of the 11th Marines. To facilitate its disbandment, the 1st Battalion, 29th Marines, was formally transferred from the 6th to the 1st Division on 15 February and went out of existence at Peitaiho at midnight on 31 March. The other three infantry battalions scheduled for disbandment stayed in being until 15 April when the 1st Division had completed its redeployment.

The new dispositions of the Marine forces in Hopeh placed a reduced garrison in Peiping under General Jones. The 2nd Battalions of the 1st and 11th Marines with supporting division medical and motor transport companies and a small headquarters comprised Peiping Group. A company from 2/1 provided security for MAG-24 installations at South Field, and a battery of 2/11 performed the same function for the Army’s 13th Troop Carrier Group at West Field. A radio relay station at Langfang on the boundary of the Peiping Group’s sector of responsibility was guarded by an artillery platoon from 2/11.

The 1st Marines was charged with the security of the area between Langfang and Tientsin’s East Station which included most of the international concession where corps and division service and support troops were headquartered. The 11th Marines watched the stretch of road, rail, and river between Tientsin and Tangku with a battery of 1/11 furnishing a guard for the 1st Wing facilities at Changkeichuang Field. Tangku and the railroad north to Lei-chuang near the Luan River was the responsibility of the 5th Marines.

Regimental headquarters of the 5th was established at Tangshan with 1/5 in Tangku and 2/5 at Linsi. The 1st Battalion’s sector extended north about two-thirds of the way to Tangshan; rifle sections guarded vital bridges and a radio relay at Lutai. A company of the 2,/5 was stationed at each of the two major KMA mines in the Kuyeh vicinity with the remainder of the battalion

mounting bridge guard and providing security for the mining area power plant at Linsi.

The dispositions of the 7th Marines remained much as they had been since November, with 2/7 units manning the important bridges and stations from Lei-chuang to Chang-li and 1/7 guarding the remainder of the railroad to and including Chinwangtao. Both the regiment and the 2nd Battalion maintained their headquarters in Peitaiho, while the 1st Battalion, reinforced by Battery G of the 11th Marines, garrisoned Chinwangtao.

The effect of the reorganization and the resultant departure of officers and men eligible for discharge or rotation was apparent in the steady fall of III Corps troop strength. At the end of January 1946, the total number of Marines and Navy men in the corps stood at 46,553; three months later the figure was 30,379. The deactivation of the 6th Marine Division dropped the ground strength of the Tsingtao garrison by over 6,000, while the 1st Division lost nearly 4,000 men, and the 1st Wing dipped from 6,175 to 4,200.12

Several important command changes took place in this period of reorganization and reduction of Marine forces. On 17 February, Brigadier General Walter G. Farrell from the staff of AirFMFPac replaced General Johnson as Assistant Wing Commander at Tsangkou Field. Farrell, like Johnson, was a veteran of prewar China expeditionary duty. On 1 April, General Howard, who had requested retirement after serving over 30 years as a Marine officer, relinquished command of the Marines in Tsingtao to General Clement.13 For three weeks during February and March, while General Rockey was on temporary duty in Pearl Harbor at FMFPac headquarters, General Peck commanded III Corps as senior Marine officer in China.

Despite the handicap of constant personnel changes and shifting of units in the first months of 1946, the missions assigned to the Marines were efficiently executed. The repatriation of the Japanese kept pace with the shipping assigned. The output of coal from the KMA mines in the Kuyeh area shipped from Chinwangtao climbed well above the 100,000-ton minimum set by China Theater and stayed there. And the lines of communication between Peiping and Chinwangtao were kept open.

An additional mission not formally laid down in operation orders was given IIIAC in January. General Marshall suggested that the Marines at Tsingtao take an active part in arranging the distribution of UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration) supplies in Communist areas of Shantung. The general felt that such action might improve the relations between the Communists and the Marines. Since the United States was by far the heaviest contributor to UNRRA, any help to the United Nations agency’s humanitarian and economic relief efforts could be considered

a furtherance of U.S. policy aims.14 Using light planes of VMO-6, Marine officers and UNRRA officials flew to Chefoo and Lini in January to coordinate plans for the delivery of food, clothing, and agricultural supplies. Both Generals Howard and Clement made visits to the Communist-controlled cities to assist liaison efforts.

The incidence of firing on Marines, both those on outpost duty and on aerial patrol, fell off appreciably during the months immediately following the signing of the truce. Assistance provided UNRRA in carrying out its relief program in Communist territory seemed to have the good effect desired by General Marshall. The atmosphere was hopeful and the signs at this juncture of Marine activity in North China pointed toward an early withdrawal of American troops.

In Chungking, the Political Consultive Conference which met during January arrived at a basis for organization of a coalition government that seemed to satisfy both sides. The Committee of Three was then able to agree upon a plan for integrating the Communist and Nationalist armies into a single force. The success of this latter scheme, and of the political solution, depended entirely upon the ability of the Executive Headquarters to bring an absolute end to the fighting. The experience of the truce teams proved, however, that the end of the fighting was as far off as it had ever been. Compromise agreements achieved by prolonged negotiation were violated by either side whenever the situation shifted to favor one over the other.

Marine Truce Teams15

General Marshall believed that Marine participation in the conflict control activities of Executive Headquarters should be restricted. He appeared anxious to avoid any possible misunderstanding arising from their ambiguous role in support of the Nationalist reentry into North China.16 By early March, however, it became apparent that there were not enough qualified U.S. Army personnel available to form the American contingents of all the needed truce teams. Under the circumstances, General Marshall directed the assignment of a select group of Marines to temporary duty with the Executive Headquarters. The understanding was that they were to be relieved as soon as suitable Army replacements arrived from the States.

On 11 March, III Corps issued a special order directing the formation of six liaison teams for Executive Headquarters, each to be headed by a colonel or lieutenant colonel, with a lieutenant signal officer, a radio mechanic, two radio operators, and a mechanic-driver as team members. The six senior officers chosen were Colonels Theodore

A. Holdahl and Orin K. Pressley and Lieutenant Colonels Gavin C. Humphrey, Jack F. Warner, Maxwell H. Mizell, and LeRoy P. Hunt, Jr. The need for the Marines was pressing, and the team commanders reported to Peiping on 13 March for briefing from their former posts at Tangshan, Tientsin, and Tsingtao. On the 18th after joining their Nationalist and Communist members and interpreters assigned by the headquarters, the first Marine-directed teams were sent into the field.

Two of the teams, those led by Mizell and Warner, acted as watchdogs on the railroad lines of communication. The other teams drew assignments in areas of actual or probable conflict where their duties required them to try to keep the peace through negotiation with the contending sides. The effort was taxing, and the round of conferences among the three principals members as well as the discussions with local military leaders were endless. One Marine observer who visited Pressley’s team at Chihfeng in Jehol Province commented that this method of operation placed a tremendous burden on the American member:–

Neither the Nationalist nor the Communist representative take the initiative in solving problems which come before the team. Indeed, long hours are spent in discussion of minor points while action on major points is delayed for weeks at a time. Even after action is taken and reports forwarded to Executive Headquarters one member or the other will attempt to void the decision by a new vote. The American representative has displayed more concern and taken more interest in the operation of the team than either of the Chinese representatives.17

For more than three months, the Marines with the field teams and a few radio and supply men at Peiping, a group which never exceeded 60 officers and men, played an important part in the American attempt to make the truce work. Life in the field was not easy; the place of duty was usually deep in China’s interior, and the only contact with home base was the radio and a weekly Army or Marine transport plane carrying supplies and mail. Being shot at was not at all an unusual experience for men who tried to step between two fighting forces. still, the reaction of the responsible Americans on the teams to their problems was much the same as General Marshall’s. When he visited North China and Manchuria in early March, the general pointed out that “it is not in human nature to expect individuals to forget the events of the past but there isn’t time to cogitate on that now. The rights and wrongs of the past 18 years will probably be debated for 18 years to come. But we have something now that demands that we look entirely in the future.”18 He noted further an attitude toward his task that was shared by many American team members in saying, “I am deeply involved in this matt, er and I don’t like to have anything to do with failure.”19

This determination to get the job done successfully was graphically demonstrated by the work of the few Marines who operated in South China as part of the truce team headquartered at Canton. In the mountains north and east of the city, some 3,000 Communist guerrillas posed a constant threat to lines of communication, and the Nationalists, after trying unsuccessfully to root them out, agreed to allow their evacuation by sea to Chefoo. Six Marines, two officers and three sergeants led by Captain Albin F. Nelson, were assigned by Executive Headquarters to shepherd the evacuation.

On 23 April, Nelson’s group flew from Peiping to Canton and, after a month of preparation, went up into the mountains to contact the Communist forces. Three sub-teams, each composed of a Marine officer and an NCO, a Nationalist and a Communist officer, an interpreter, and a small police escort, arranged assembly points and safeguarded the Communists in their travels through Nationalist lines. The tension was high between the bitter enemies and an open fight was never more than a hair’s breadth away. Team members handled all arrangements for feeding and housing the evacuees, inoculated them against communicable diseases, and even mustered out those Communists who did not want to make the move. The three columns collected by the sub-teams, which included women and children as well as soldiers, assembled on the beach of Bias Bay 40 miles northwest of Hong Kong( on 23 June. Typhoons delayed the arrival of LSTs which took the Communists north to Chefoo until late afternoon of the 29th, the last day of the local truce.

The job done by Nelson’s sub-teams was unique in concept and execution, but it shared the atmosphere of tension characteristic of most truce team efforts. Although for a time in the first half of 1946 it appeared that the truce might become more than a paper agreement, fighting continued, Because Communist and Nationalist commanders did not enjoy having publicity given to their cease-fire violations, the arena of battle often shifted to areas not policed by Executive Headquarters. The blame for eventual failure of the truce cannot be laid solely at the door of either side in the civil war; but as events proved, the Communists benefited from truce negotiations and regarded them strictly as devices to gain time.20

The End of the IIIAC21

In February, Generals Marshall and Wedemeyer recommended that China Theater be deactivated on 1 May. The move was made in an effort to strengthen Chiang Kai-shek’s pressure on Soviet Russia for the removal of its

occupation troops from Manchuria. The residual functions of the theater command were to pass to U.S. Army Forces, China, an administrative and service command, and Seventh Fleet. Operational control of the III Amphibious Corps would be exercised by Commander, Seventh Fleet, Admiral Charles M. Cooke, who had replaced Admiral Barbey.

General Marshall was anxious to reduce Marine forces in China to air transport, housekeeping, and security details whose main purpose would be logistical support of Executive Headquarters. He stated frequently in conversations with General Wedemeyer that the continued presence of the Marines in Nationalist territory was a source of considerable embarrassment to him in his peace negotiations. The crux of the matter lay in Marshall’s inability to persuade the Generalissimo to make the long-promised relief of the Marines and to obtain the agreement of the Committee of Three to the movement of Nationalist troops to North China for this purpose.

General Rockey, in conversations with General Wedemeyer on 18–19 March, recommended strongly that the Marines not be relieved until first-line CNA troops were firmly established in their place. The IIIAC commander believed that the Communists were strong enough to disrupt communications completely between Peiping and Chinwangtao, to stop production at the KMA mines, and even to capture ‘Tsingtao in the absence of effective opposition. Wedemeyer agreed to the risk involved in making the relief, but pointed out that the relief must be made even if only Nationalist forces locally available were used. He felt that truce teams judiciously placed in areas of potential trouble might prevent Communist depredations. It appears that both Wedemeyer and Marshall believed that the Nationalists would make no move to provide adequate security forces in North China until it was clear to them that the Marines were going to be pulled out. A tentative target date for the start of the withdrawal of the Marines was set for 15 April, but this, as well as everything else in the concept, depended upon the outcome of truce negotiations.

General Marshall returned to Washington on 12 March for a month of conferences bearing on the China situation. His absence coincided with the stepping-up of the Nationalist drive against the Communists in Manchuria, an operation which made Chungking even less willing than usual to divert good troops to rail and mine security. The Communists, naturally enough, were dead set against any movement of CNA troops into North China which might strengthen the Nationalists hand in Manchuria. Adding further complications to the issue was the belief of theater intelligence officers that the “Marines in China are the anchor on which the Generalissimo’s whole Manchuria position is swinging.”22 The effect of the altered situation was to slow the reduction of Marine forces considerably.

The pressure for the relief of the Marines was not all directed at the Nationalists or prompted by General Marshall’s desire to get American combat

troops out of China. In the postwar budget of the Navy Department expenditures for the Marine Corps were calculated on the basis of peacetime strength and organization, and the Commandant was vitally interested in withdrawing or deactivating any units in the field that were not necessary to the accomplishment of the missions assigned IIIAC. He was insistent that changes should be fitted into the organizational framework of the FMF and that the divisional structure be retained.23

Before any firm commitment was made to reduce the ground element of IIIAC, a substantial cut in its air strength was ordered. Qualified flying personnel and plane mechanics were in short supply throughout the Marine Corps, and it was no longer possible to maintain all the squadrons in North China in efficient operating status with the replacements available. In early April, plans were laid for the return of MAG-32 to the States during the following month, and the Commanding General, AirFMFPac proposed that MAG-25 also be sent home. General Rockey recommended strongly that at least one transport squadron be retained to support Marine activities and to assist Executive Headquarters in maintaining its truce teams in the field. The recommendation was adopted quickly, and VMR-153 was selected as the unit to stay while its parent group and VMR-152 returned to the west coast of the United States.

In order to determine how Marine ground forces in IIIAC could be reorganized, General Geiger and representatives of his FMFPac staff visited China between 12 and 22 May. Before leaving Pearl Harbor, the FMF staff officers drew up a plan which eliminated III Corps Headquarters and Corps Troops and 3rd Brigade Headquarters and Brigade Troops, leaving only the 1st Marine Division (Reinforced) in North China. Personnel equal to those eliminated, 391 officers and 5,700 enlisted men, were to be returned to the U.S. This plan formed a working basis for talks with Admiral Cooke and General Rockey. Once Geiger was on the scene in North China, the IIIAC and FMFPac staffs worked out changes that better fitted the situation.

Rockey had no substantial objection to the reductions outlined, but he believed that the 1st Division would need a headquarters augmentation in order to control its scattered components. Similarly, the reduction agreed upon for Tsingtao was much lighter than that originally proposed in view of the separate nature of the command there. At the end of several days of conferences, Geiger and Rockey approved a reorganization that eliminated a number of billets and reduced Marine strength by 125 officers and 1,417 enlisted men. Cooke concurred in this proposal and recommended its acceptance to Marshall, who gave his approval on 24 May.24

When the reorganization order was published on 4 June, to take effect on the 10th, General Rockey was named Commanding General, 1st Marine Division (Reinforced) and Marine Forces, China, the latter a task force designation for the division. General Worton went from chief of staff of the corps to assistant commander of the division; in general, corps staff officers were assigned the senior positions on the augmented staff. Some 600 officers and men from IIIAC Headquarters and Service Battalion were added to division troops, and the battalion itself was transferred to the division for subsequent return to the U.S. The 1st MAW, consisting of MAG-24 and the squadrons, including VMR-153, assigned to wing headquarters, came under operational control of the division. The 7th Service Regiment and one company of the 1st Separate Engineer Battalion also became part of the reinforced division; the remainder of the engineer unit was returned to the States.

At Tsingtao, the 3rd Marine Brigade ended its short existence with most of its units becoming part of the 4th Marines (Reinforced) or Marine Forces, Tsingtao. General Clement was given both commands in keeping with the wishes of General Marshall and Admiral Cooke that a general officer continue to represent the Marines in the port city. Aside from the regiment and its attached units, the task force included VMO-6, the 12th Service Battalion, and 96th Naval Construction Battalion. The total authorized strength of the 1st Marine Division (Reinforced) was set at 25,252 officers and men with 2,517 of that number naval personnel assigned to port operating, construction, and medical units.

As part of the reorganization of Marine forces, the number of general officer billets in China was cut. In view of the sharply reduced strength of the wing, the rank of the commander was set as brigadier general and the position of assistant wing commander was deleted from the T/O. General Woods was assigned new duties as Commanding General, Marine Air, West Coast and General Farrell returned to AirFMFPac. The new wing commander, Brigadier General Lawson H. M. Sanderson, reported from AirFMFPac and relieved Woods on 25 June. General Peck, who had requested retirement in April after completing more than 30 years of active duty, remained in command of the 1st Division at the Commandant’s request25 until the reorganization was completed. To round out the picture of major command changes, General Jones moved from his Peiping command to duties as President of the Marine Corps Equipment Board at Quantico.26

During the many changes in composition of Marine forces in China that took place in the spring of 1946, there was little basic change in assigned missions. Whether the operation orders originated from China Theater or Seventh Fleet, the Marines still were charged with responsibility for seeing that the vital coal supplies from the KMA mines were shipped without interruption and that

the line of communication between Tientsin and Chinwangtao was kept open. They were directed to provide logistical support to Executive Headquarters until the Army was able to relieve them. In furtherance of these tasks, principal garrisons were continued at Peiping, Tientsin, Tangku, Peitaiho, and Chinwangtao with orders to secure only the “actual ground occupied by U.S. installations, property, materiel, personnel, and intervening or surrounding ground necessary for wire and road traffic communications so that the elements of the command are not isolated.”27

In the south, the same garrison order applied to the Marine force at Tsingtao. The U.S. installations to be guarded were almost exclusively naval in character as the city had become Seventh Fleet headquarters and base of operations by June. A growing shore establishment provided administrative and logistic support to the ships of Admiral Cooke’s command. In addition, an American naval training group had been operating at the port since December with a mission of teaching Nationalist crews how to sail and fight the U. S, ships that were transferred to the Central Government under military aid laws.28

The most significant change in the tasks set the Marines was the ending of supervisory responsibility for Japanese repatriation. In April, SCAJAP increased its allotment of LSTs to the North China run and 125,872 Japanese were sent home from Tsingtao and Tangku.29 By the end of May, repatriation was completed except for those persons detained by the Chinese, serving on repatriation staffs, or too ill to be moved; only 15,855 people remained to be returned to Japan.30 With the sailing of the last scheduled repatriation ship from Tangku on 15 July, even this rearguard was gone; more than 540,000 Japanese had been repatriated from North China under Marine supervision.31

When the last SCAJAP LST cleared Tangku, it also marked the end of the entire repatriation program from China proper which saw the return of over 2,200,000 Japanese to their home islands in nine months of dedicated effort. The significance of the American contribution to this remarkable undertaking was summed up well by General Nagano, the former Japanese commander at Tsingtao, on the occasion of his leaving China. The Japanese officer, who had been charged by General Shepherd with the responsibility for seeing the last of his countrymen home from Shantung, wrote in an unofficial report to the Marine general:–

I cannot but be grateful to you and your country. This may sound rather strange from my lips. I like plain speaking. Please do not think that I am making

compliments. If anyone ever tells you that I [am] please tell him to go to Tsingtao and stand in front of the American L.S.T. and see the Japanese soldier as he passes on the ramp salute the Stars and Stripes; no Chinese flag, no Russian flag, no English flag, but the Stars and Stripes, under which they will be able to sail to Japan. Happy they! Just think of those Japanese soldiers and civilians in Manchuria and Siberia. We cannot be too grateful to you.32

The early months of 1946, when the mass of Japanese soldiers and civilians moved from the interior of North China to the repatriation ports, was the period of greatest success of the truce. The Communists, by permitting the peaceful withdrawal of the troublesome Japanese, apparently were clearing the deck for action. The number of incidents in which Marine outposts were involved in clashes with Communist troops increased steadily as summer came on. Most of these sudden flare-ups were of a minor nature and American casualties were few. Only one man was killed in the first six months of 1946 in such an affair. He died on 21 May when a small reconnaissance patrol of the 1st Marines were fired upon by 50–75 armed Chinese near a village south of Tientsin. The attacking force slipped away unpunished.

The renewed Communist effort to retain control of North China was particularly marked in Shantung where the pressure on the CNA got so bad in early June that General Clement believed that Tsingtao might be attacked. Twelve Corsairs from VMF-115 at Peiping were stationed at Tsangkou Field from 12–15 June to back up the defenses of the 4th Marines, which held a main line of resistance well inside the positions of the Nationalist garrison. The Communist drive slackened after 15 June while negotiations were being made to bring to an end even more serious fighting in Manchuria.

In many respects, the organized harassment of lines of communication in Hopeh and the bitter struggle in Shantung seemed to have been initiated by the Communists to relieve pressure on their troops north of the Great Wall. The armies of the Central Government won a series of heady victories in Manchuria during an all-out spring offensive, but the defeated Communist forces avoided entrapment. The magnitude of the battles was so great that it threatened the end of all peace efforts. Since both sides claimed at times that the 10 January truce had no effect beyond China proper, General Marshall had to negotiate a separate truce for Manchuria, A temporary halt to the fighting was ordered by the Committee of Three on 6 June and a more permanent truce was signed on the 28th. In short order, this agreement too came to be more honored in the breach than the observance.

At the end of June, General Rockey was able to make a realistic appraisal of the Marine situation in the coming months. He reported to the Commandant that in his opinion:

... conditions will operate to keep Marines in North China for a considerable period, at least during the remainder of this calendar year. Our departure would very materially influence the whole situation in China and General Marshall has apparently reversed his former ideas

about our early withdrawal. The CNA is spread thin in Manchuria. They do not appear to have the necessary troops to relieve U.S. If the Central Government loses the key cities in North China or if the coal fails to move from the KMA mines to Shanghai, Hong Kong(, Nanking, and elsewhere, the show is over as far as present plans for the unification of China are concerned.33

Capture and Ambush34

In July, the Communists reorganized their armies, naming the whole, “People’s Liberation Army,” which agreed with their title for the territory they held as the “liberated areas.” In the Communist view, the “liberated area” in Hopeh extended right up to the perimeter defenses of the Marine and Nationalist outposts along the Peiping–Mukden Railroad. Despite its nominal coloring as Nationalist, the countryside over the entire range of land between Chinwangtao and Peiping was alive with Communist guerrilla forces. In their actions they took their cue from Mao Tse-tung, whose pamphlets incorporating hard-earned lessons of guerrilla warfare were primers in Communist military schools. In regard to planning, he said:–

Without planning it is impossible to win victory in a guerrilla war. The idea of fighting a guerrilla war at haphazard means nothing but making a game of it—the idea of an ignoramus in guerrilla warfare. The operations in a guerrilla area as a whole or the operations of a single guerrilla detachment or guerrilla corps must be preceded by the most comprehensive planning possible. ...35

This dictum provides a revealing background for two Communist actions against the Marines which took place in July. One was the first occasion on which Marines other than downed airmen were held prisoner, and the other was a deliberate and well planned ambush. Yenan had evidently decided that the time had come for a major incident involving the Marines, one that could be worked for its full propaganda value. Such an incident would increase pressure in the U.S. for the withdrawal of the Marines because of the danger in which they stood.

On 13 July, the summer afternoon’s heat prompted eight men from the bridge guard at Lin-Shou-Ying to head for a nearby village to get ice. This action violated a division directive that guard detachment members would stay within the barbed wire defenses of their posts. Communist soldiers, about 80 strong, surprised and surrounded the Marines at the icehouse. One man escaped unnoticed in the gathering dusk to alert the bridge outpost which radioed

the news to 7th Marines headquarters at Peitaiho, 15 miles to the north. That evening all available men of the 1st Battalion boarded a special train at Chinwangtao and rode to the capture site to begin a dogged pursuit that continued all through a rainy night and on into the next day. No contact was made and it soon became apparent that a long search was in prospect. The Communist troops, armed with a sure knowledge of the countryside and protected by a friendly populace, was able to stay well away from the Marines.

The regimental commander decided to relieve the 1st with the 2nd Battalion and withdraw 1/7 to prepare for extensive field operations. A 200-man combat patrol of 2/7 moved out from Changli to continue pursuit on the 16th. Fields of kaoliang higher than a man’s head bordered the roads, blocking off all view. The villages along the route were deserted when the Marines first entered and then reoccupied only by women, oldsters, and children; no young men were ever seen. The patrol could easily have been ambushed despite its own precautions and the overhead cover of OYs, as virtually nothing could be seen through the dense cover of ripening crops. when a circuit of the 2/7 sector had been made without result, the patrol returned on 18 July to Changli, secured its base camp, and went back to Peitaiho.

Because none of the Marines taken near Lin-Shou-Ying or their captors could be located by patrols, Executive Headquarters was asked to take a hand in obtaining the release of the men. Before the Communists would permit a truce team to enter their territory to begin negotiations, they required that all Marine units return to the positions held on the 13th. A series of discussions were held after this was done. The communists demanded that the U.S. recognize the “unlawful” act of entering the “liberated area” and apologize; that there be no repetition of the incidents; and that the Marines captured each make a written statement of their good treatment. The upshot of this was that the seven men each wrote a letter attesting to their good treatment at the hands of the Communists, and U.S. negotiators assured the Communists that additional orders restricting the movement of Marines in the Chinwangtao area would be issued. The men were returned unharmed on 24 July.

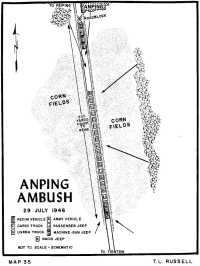

No one but the Communists could be pleased by the distasteful but necessary solution to the problem posed by the captured Marines. During all the talks leading to the men’s release, Communist officials hammered away at one theme—the Marines were actively aiding the Chinese Nationalist Army. This line of propaganda was to be sounded again and again as long as the Marines were in China, but nowhere in so outrageous and lying a fashion as in the Communist explanation of their ambush at Anping on 29 July, (See Map 35.) According to Yenan, the positions of its Eighth Route Army near Anping on the Peiping–Tientsin road were suddenly attacked on the morning of the 29th and in the battle “more than sixty U.S. soldiers were discovered fighting shoulder to shoulder with eighty-odd Kuomintang troops. ... In the afternoon an American force came as reinforcements from Tientsin. With a view to make the American

Map 35: Anping Ambush, 29 July 1946

troops conscious of what they were doing, units of the Eighth Route Army left the battle at once.”36

In truth, the Communists laid an ambush at Anping, knowing full well that their prize would be a routine Marine supply convoy. As a matter of policy, no CNA troops accompanied American trucks so there could be no claim of mutual interest or protection. On 29 July, the only Chinese vehicle in the convoy was a truck bearing UNRRA supplies. The presence of Communist troops in strength anywhere along the road to Peiping was completely unexpected, although sniping at individual trucks and jeeps had occurred several times in June. It was as a result of this occasional firing that there was a guard and convoy; the patrols which had searched the road regularly from October 1945 until March 1946 had been discontinued because there seemed to be no need for them.

On the morning of 29 July, the convoy assembled at the 1st Marines compound in Tientsin. The patrol escort, commanded by Second Lieutenant Douglas A. Corwin, consisted of 31 men from 1/11 and a 10-man 60-mm mortar section of the 1st Marines. In addition to nine supply trucks for the Peiping Marine garrison and the UNRRA vehicle, there were two Army staff cars with American personnel from Executive Headquarters and three .jeeps carrying Marines bound for Peiping. The patrol itself rode in four reconnaissance trucks and four jeeps, two of the latter carrying TCS radios. The TCSs lacked the range to keep in contact all the way to Peiping, so there was a considerable gap between the time the patrol lost touch with 1/11 and the time it was picked up by 2/11’s set at South Field. Within that stretch lay the village of Anping.

The convoy started out at 0915 with the patrol protection divided equally between forward and rear points; all vehicles proceeded at 50-yard intervals with 100 yards between elements. Radio contact with 1/11 faded by 1105 and the patrol proceeded normally until about noon when it had reached a point 44 miles from Tientsin. A line of rocks across the road slowed the lead jeeps and as they were threading their way through these obstacles, a new roadblock of ox carts was spotted just ahead. The point stopped and dismounted cautiously. At that moment, about a dozen grenades were thrown from a clump of trees 15 yards to the left of the road block. Lieutenant Corwin was killed immediately and most of the men with him were either killed or wounded in this initial attack. The survivors took cover and returned the Communist fire.

The body of the convoy halted quickly when it in turn came under steady and well-directed rifle fire which originated in a line of trees about 100 yards to the right of the road. Very few of those men riding the supply trucks and passenger vehicles were armed and they took cover as best they could in the ditch to the left of the road. The ambush was complete when the rear point, stalled by the convoy, was sprayed with fire from positions to the right and left rear. The second in command of the patrol, Platoon Sergeant Cecil J. Flanagan, then ranged up and

down the long column of vehicles directing return fire. The mortar and machine gun with the rear point were instrumental in stopping Communist attempts to rush. About 1315, during a lull in the attack, three Marines turned one of the jeeps around and made a successful break for help.

The Communists, responding to bugle signals, finally ceased fire about 1530 and began withdrawing. The attacking force, which had an estimated strength of 300 men well-armed with rifles and automatic weapons, seemed content to call it a draw with the smaller and weaker defending force. On order of the senior officer in the convoy, an Army major in special services at Executive Headquarters, the American group then gathered up its wounded, and covered by a rear guard of Flanagan’s men, continued on for Peiping. Only a few scattered shots greeted the lead vehicles as they left the ambush area; three damaged trucks were abandoned. The convoy and patrol reached the old capitol at about 1745. The Marine casualty list of the afternoon’s action reported 3 killed and 1 died of wounds and 10 wounded, all of whom were from 1/11. The first news of the ambush to reach Tientsin was brought by the Marines who had escaped from the trap early in the fire fight. Their wildly racing jeep overturned on the outskirts of the city, injuring two of the occupants, and delaying their report until a passing vehicle could be commandeered for the rest of the passage to the nearest Marine post. The 11th Marines got word of what had happened at 1630 and a heavily armed combat patrol was immediately ordered to get ready. Air support was requested of the wing, while the regimental executive officer took off in an OY of VMO-3 to scout the scene of action. Flying low over Anping at 1730, he counted 15 bodies in Communist uniform, but saw no sign of the attackers. Five Corsairs of MAG-24 which reached the ambush site at 1917 also failed to spot the Communists,37 nor was there any longer a sign of the bodies.

The 11th Marines relief force, 400-strong and backed by two 105-mm howitzers, cleared the French Arsenal at 1830 driving “at reckless speed, and still only reached the scene of combat at 2045.”38 The Communist force had vanished, taking its dead and wounded with it, and the Marines could only tow in the shot-up trucks that marked the ambush site.

In the wake of the attack, orders were issued that substantially increased the strength of patrols on the Peiping- Tientsin road. Aerial surveillance of the road increased, and fighter aircraft alert time was cut from 2 hours to 15 minutes. More powerful field radios were used to bridge the communication gap between the two cities. No further attack of similar nature occurred during the remaining months the 1st Marine Division was in China.

General Rockey launched a careful investigation of the circumstances of the ambush and the nature of the attacking force. The findings were that a deliberate and unprovoked attack had been made by strong elements of one or more

regular Communist regiments. A similar inquiry of the events at Anping conducted by a special team of Executive Headquarters foundered on Communist obstructions.39 On General Marshall’s order, the American members withdrew from the team and submitted their own report which agreed entirely with that of the 1st Marine Division.

To Marshall, the most disturbing aspect of what he called a deliberately planned and executed stroke at the Marines, was its indication of a hardening in attitude on the part of the Communists. The American representative commented later that prior to 29 July 1946 “there had not been a deliberate break which struck at us specifically, which means that they were taking measures against the Nationalist Government and ourselves all included, which is a very definite departure from what had been the status before.”40 After the Anping incident, the element of risk involved in stationing the Marines on outpost guard increased substantially. As a result, the latter part of 1946 saw a considerable concentration of Marine positions and the foreshadowing of their complete withdrawal from Hopeh.