Chapter 10: The U.S. and Japanese High Commands

An army is of little value in the field unless there are wise counsels at home.—CICERO

During the early months of the war, while the Japanese tide of victory was flowing strong, the Allies had already begun to look to the future. Though the effort to defend the Malay Barrier had failed, the Allies had hurriedly sent reinforcements to hold Australia, Hawaii, and the island chain across the Pacific. Already, plans were maturing to build a base in Australia and to develop air and naval bases along the line of communications. It was still too early to predict the course of operations once the Allies were in a position to take the initiative, but it was not too soon to prepare for that time. Thus, while bases were being established and forces deployed to the Pacific, the Allies began to organize for the offensive ahead.

The first step in preparing for an offensive was to develop an Allied organization to coordinate the efforts of the Allies, and within this framework to devise a mechanism for planning and coordinating operations on many fronts. In this the British had the advantage of an early start, and a combined staff was quickly formed. The American counterpart of this organization, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, took shape more slowly. Utilizing existing organizations and staffs, the Americans developed during the months

after Pearl Harbor a mechanism for directing the U.S. war effort that lasted, with modifications, until the end of the war. For the Pacific, which was to become an area of U.S. responsibility, this Washington organization became in effect a supreme command.

The organization of the Japanese military high command, perfected before the war, was, on the surface, not unlike that of the United States. The commander in chief of the Japanese armed forces was the head of the state, the Emperor. Under him was Imperial General Headquarters with its Army and Navy Sections—there was no separate air service—which prepared and coordinated the operations of forces in the field. The Army and Navy Ministers sat in the Cabinet and civilian agencies directed the war effort on the home front. But this organization, superficially so similar to the American, could not conceal the fact that Japan was a military dictatorship in which the civilian officials exercised little real authority and the Emperor was but a symbol.

The Washington Command Post

At the ARCADIA Conference in Washington, it will be recalled, the first steps

had been taken toward establishment of a combined U.S.–British organization for the conduct of the war.1 It had been decided then that the Combined Chiefs of Staff would be located in Washington, where the British Chiefs would be represented by a Joint Staff Mission. During the months that followed the combined organization began to take shape and the functions of the Combined Chiefs were more clearly delineated. By the early summer of 1942 this process was largely completed.

The American side of the Allied high command developed more slowly. The old Joint Board with its Joint Planning Committee had neither the authority nor the organization to meet the challenges of global war (or of the British committee system) , and it gave way gradually to the emergent Joint Chiefs of Staff. Membership in the two bodies, though similar, was not identical. The former had consisted of the service chiefs, their deputies, and the heads of the War Plans Division and air arms of the two services. Since December 1941, Admiral King as commander of the U.S. Fleet, though not a member, had also sat with the Joint Board, whose presiding officer at the time was the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Stark. During the ARCADIA meeting the term U.S. Chiefs of Staff, employed to designate a group comparable to the British Chiefs, had referred to four men—Admiral Stark, General Marshall, Admiral King, and General Arnold. The last two were not chiefs of a service and one of them was not even a member of the Joint Board, but their inclusion was considered necessary to balance the British representation.

Within the next few months, the membership of the Joint Chiefs, which was established on 9 February, was reexamined and took final form. General Marshall’s position was not affected, except that as a result of the reorganization of the War Department in March 1942 his authority as Chief of Staff, U.S. Army, was enhanced. General Arnold’s position as commander of the newly formed semiautonomous Army Air Forces also increased his stature in the Joint Chiefs, although he remained Marshall’s subordinate and thus not in the same position in combined councils as the British air chief who was head of a separate service.

The Navy also underwent reorganization in March designed to streamline it for the war ahead. One of the effects of this reorganization was to consolidate the functions of the Chief of Naval Operations and Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, and at Admiral Stark’s behest Admiral King was placed in supreme command of all professional activities of the Navy.2 This change was formally recognized in an Executive Order of 12 March which assigned King to both commands, designated him as the principal naval adviser to the President, and gave him a greater degree of control, over the bureaus than had ever been exercised by any Chief of Naval Operations.3 In addition, he was given two strong assistants, a Vice Chief of Naval Operations, and a Deputy Commander for the U.S. Fleet.

The effects of these moves, though

they greatly increased the authority of the Chiefs within their services, was to reduce the membership of the Joint Chiefs by one. But already a move was under way to add another, one who would represent the President much as Maj. Gen. Sir Hastings Ismay represented Churchill on the British Chiefs, and because he represented no service, could serve as an impartial chairman. The President, at first cool to the idea, was finally convinced of the advantages of such an arrangement and on Marshall’s suggestion designated Admiral William D. Leahy as his own chief of staff.4 No appointment could have been better calculated to add weight to the Joint Chiefs and to cement relations with the White House. Admiral Leahy, after serving as Chief of Naval Operations, had retired from the Navy in August 1939. Since then he had served as Governor of Puerto Rico and Ambassador to the French Government at Vichy. In June 1942, he returned to the United States, and on 18 July was recalled to active duty and designated Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief—a post without precedent in American history. With this appointment, the membership of the Joint Chiefs of Staff was fixed for the duration of the war.

The charter of the Combined Chiefs approved at ARCADIA had specifically provided for a planning staff, the Combined Staff Planners, and had even named the officers who would compose that body.5

The senior members on the American side, the Joint Staff Planners UPS) , were Brig. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow and Rear Adm. Richmond K. Turner, Chiefs of the Army and Navy War Plans Division—both members of the Joint Board and, simultaneously, of that agency’s Joint Planning Committee. In this latter capacity, they directed the work of the Joint Strategic Committee, composed of at least three officers from each of the War Plans Divisions, whose task it was to work on joint war plans, and of various ad hoc committees formed to study other problems as they arose. It was natural that this organization should be taken over bodily by the Joint Chiefs, and for a time it served both bodies equally.

This system had its disadvantages, and membership of the Joint Staff Planners was soon changed. The Navy kept its chief planner, Admiral Turner, on the committee, but gave him two assistants, one of them an air officer. Probably because of the heavier burdens of the Chief of the Army’s War Plans Division, Gerow’s successor, General Eisenhower, designated the head of the division’s Strategy and Policy Group, Col. Thomas T. Handy, as the Army member of the Joint Staff Planners instead of assuming the post himself.6 The air representative

Joint Chiefs of Staff. From left: Admiral King, General Marshall, Admiral Leahy, and General Arnold

initially was Maj. Gen. Carl Spaatz, and, after the March reorganization of the War Department, the Assistant Chief of Staff for Plans of the new Army Air Force. Other members were added from time to time—an additional member in August to even the Army and Navy representation, and then seven more members with varying status to represent logistical interests. Clearly this was not a committee of equals. The senior Army and Navy planners were its leading members and by virtue of seniority, official position, and access to the chiefs of their services their views were generally binding on the other members of the committee.

The work of the Joint Staff Planners was broad and varied, ranging from global strategy to the allocation of minor items of supply and encompassing not only strategic but also operational, logistic, and administrative aspects. Obviously, the group was too unwieldy and too diverse in its composition to handle all the problems that came before it. Most of its work was farmed out to subordinate committees, the two senior members controlling the assignments. Most of these subcommittees were ad hoc, formed for a particular task and composed of planning officers and staff experts drawn from the two services by the chief Army and Navy planners. Only the Joint Strategic Committee, which had been taken over from the Joint Board and redesignated the Joint U.S. Strategic Committee (JUSSC) , had a recognized status and membership as the working group for the Joint Planners. Assigned to it full time were eight senior and highly qualified officers, four each from the Army and the Navy War Plans Divisions. One of the Army representatives was an Air Forces officer and the Navy’s contingent usually included a

Marine officer. The committee’s charter, as defined by the Joint Chiefs, called upon it to “prepare such strategical estimates, studies and plans” as the JPS directed, and, in addition, to initiate studies at its own discretion.7 It was natural, therefore, for the Joint Staff Planners to rely heavily on the JUSSC, especially in the field of broad strategy, and to invite its members to sit with them from time to time.

The role of the JUSSC in planning proved to be quite different from that envisaged by those of its members who placed somewhat more emphasis on their strategic responsibilities than did their superiors. Much of the committee’s work proved to be routine, concerned with relatively minor matters, and so heavy was the load that it had no time left to study problems it considered more important in the conduct of the war. Moreover, some of its members thought it would be more appropriately and profitably employed in the study of future strategy than in routine matters of troop deployment, production priorities shipping schedules, and the like.8

There was much merit in this view. Certainly there was a need for long-range studies, for a group of senior and experienced Army and Navy planners, free from the burdens of day-to-day problems, who would devote their time to the larger issues of the war, to future strategy and political-military questions. But who was best qualified to advise the Joint Chiefs on these high-level matters? One view was that this should be done by a reconstituted JUSSC reporting directly to the Joint Chiefs and consisting of four flag or general officers representing the Army, Navy, Army Air Forces, and the Navy air arm. Another proposal for utilizing the JUSSC more effectively in strategic planning was to reduce its membership to four senior officers with two assistants for each of its members and charge it with responsibility, under the Joint Staff Planners, for coordinating the preparation of plans in support of the basic strategy, reviewing these plans, and developing recommendations for changes in the basic strategy. If neither of these proposals was acceptable, then the JUSSC, said one of its members, ought to be redesignated the “Joint Working Committee” of the JPS in frank recognition of its present function.

The Joint Chiefs considered this problem very carefully over a period of several meetings in the fall of 1942. There was no disagreement with Marshall’s assertion of the need for “an organization, with sufficient prestige and disassociated from current operations, which can obtain a good perspective by being allowed time for profound deliberations.”9 In his view, an entirely new organization should be created to meet this need. The possibility of using the deputy chiefs of the services for this purpose, an arrangement that would permit the Joint Chiefs to leave decisions on minor matters to the new committee, was discussed at some length. The solution finally adopted represented a combination of the various proposals. To satisfy the need for a

high-level group of planners, the Joint Chiefs formed a new committee, called the Joint Strategic Survey Committee (JSSC)—not related to the JUSSC—consisting of three flag or general officers, assigned to full time duty. Reporting only to the Joint Chiefs, these officers would have no duties other than to reflect on basic strategy and the long-range implications of immediate events and decisions. No sources of information were to be denied them and they could, if they desired, attend any meeting of the Joint or Combined Chiefs of Staff and of Joint or Combined Staff Planners.10

This was to be truly a committee of “elder statesmen,” and the appointments made fully bore out this intention of the Joint Chiefs. Representing the Army was Lt. Gen. Stanley D. Embick, who had been associated with strategic planning throughout a long and distinguished career. Vice Adm. Russell Willson represented the Navy, though he had to be relieved of his important duties as Deputy Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, to serve on the committee. The Army Air Forces member was Maj. Gen. Muir S. Fairchild, recognized as an officer of exceptional ability and breadth of view. With this membership, unchanged throughout the war, the Joint Strategic Survey Committee began its existence in November 1942.

The creation of the JSSC solved only one of the problems facing the Joint Chiefs. Still needed was a group that could act for them on minor matters and could represent them on various governmental bodies where military advice was required. The idea of a committee consisting of the Deputy Chiefs of Staff, originally proposed as an alternative to the JSSC, seemed an admirable solution to this problem. Thus came into existence the Joint Deputy Chiefs of Staff (JDCS) , consisting initially of Lt. Gen. Joseph T. McNarney, Vice Adm. Frederick J. Horne, and Maj. Gen. George E. Stratemeyer.11

But the problem of the Joint U.S. Strategic Committee was still unresolved. The role the members of the committee had envisaged for themselves had now become the province of the elder statesmen of the Joint Strategic Survey Committee. Moreover, the former had been engaged since August 1942 on future strategy for the defeat of Japan. In addition, it was directed late in November to prepare a long-range study for the employment of United Nations forces for the defeat of both Germany and Japan, to be coordinated with British studies on the same problem. Since the Joint Strategic Survey Committee was engaged in similar studies, the need for a review of the duties of the JUSSC was more urgent than ever. Various proposals had been put forward, but by the end of 1942 no change had been made When it came in May 1943, it was accompanied by a reorganization of the entire JCS structure.12

The work of the Joint Chiefs was supported by a variety of other committees, some of which functioned purely in a joint capacity and some as the U.S. component of committees of the Combined Chiefs. Intelligence activities were under

the purview of the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC), which had been taken over from the Joint Board at the same time as the JUSSC. In recognition of the role of psychological warfare in modern war, a separate committee (JPWC) was formed to advise the Joint Chiefs on this subject. The Office of Strategic Services was also a part of the joint committee system, directly responsible for certain matters to the Joint Chiefs and for others to the JIC and the JPWC. Additional committees advised on communications, weather, new weapons and equipment, and transportation. (Chart 3)

Within the War Department, strategic planning and the coordination of military operations were centered in the Operations Division of the General Staff, successor to the old War Plans Division whose functions it absorbed in March 1942. In a very real sense, the Operations Division was General Marshall’s command post, the agency through which he exercised control over and coordinated the vast activities of the Army in World War II. All strategic planning in the War Department was done within the Operations Division, or funneled through it, and its officers represented the Army on virtually every major combined and joint committee. Any matters that might affect strategy or operations came to it, and its roster included logisticians as well as ground and air officers. So varied were its functions that General Wedemeyer was able to inform a British officer of the Joint Staff Mission that “your Washington contact agency is now the Executive Officer, Operations Division, War Department General Staff. He will be able to refer you directly to the proper section for solution of any problems presented.”13 In effect, it was a general staff within the general staff.

The organization of the Operations Division was tailored closely to its duties and the needs of the Chief of Staff. Under Eisenhower, its chief from February to June 1942, it was organized into three major groups—planning, operations, and logistics—and an Executive Office. The first, called the Strategy and Policy Group, was the one most intimately concerned with joint and combined planning, and was responsible for matters of general strategy, the preparation of studies, plans, and estimates, and the issuance of directives for theater and task force commanders. Its chief was the Army member of the Joint Staff Planners and from it came the representatives of the JUSSC. It had a section that dealt with future operations only, another with strategy, and one with subjects that came up for discussion at the combined level.

The coordination of operations within the Operations Division was handled by the Theater (Operations) Group. This was the largest of the groups, and was organized ultimately into sections corresponding to the various theaters of operations and serving in effect as Washington echelons of these theater headquarters. It was this group that kept in close touch with theater problems, directed the movement of troops overseas, and coordinated all War Department activities relating to theater requirements. For Pacific matters there were two sections, the Pacific and the South-

Chart 3—The Washington High Command and the Pacific Theaters, December 1942

west Pacific Theater Sections, headed from mid-1942 to mid-1944 by Cols. Carl D. Silverthorne and William L. Ritchie. Both these officers made frequent trips to the theaters and were constantly called upon by the theater commanders and by the planners in Washington for assistance and advice on theater problems.

In recognition of the intimate relationship between logistics and strategy, and the dependence of operations on manpower, weapons, equipment, and transportation, the Operations Division had a Logistics Group. This group did not participate in logistical planning or in the manifold activities related to supply of Army forces; these were the functions of G-4 and of the Army Service Forces under General Somervell. What it did instead was to view these matters from the strategic level in order to advise General Marshall on their implications when decision by the Chief of Staff became necessary. It was in a unique position to do so because of its access to the planners and theater experts in the division, and its members represented the Army on a variety of committees, both military and civilian.

The Navy Department organization for strategic planning and direction of operations was not as highly centralized as the War Department organization. The reason for this difference lay partly in Admiral King’s dual status as Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) and Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH). In the former capacity he was responsible for “the preparation, readiness and logistic support of the operating forces” of the Navy—its fleets, shore establishments, sea frontiers, and all seagoing forces. But as COMINCH, in which capacity he was the supreme commander of all operating forces of the Navy, Admiral King was responsible for execution of the plans he helped to shape. To meet his dual responsibilities, King formed two separate staff organizations, each of which maintained its own planning office.14

In his role as CNO, Admiral King had ultimately six principal assistants, a Vice Chief of Naval Operations, a Sub Chief, a Deputy for Air Operations, and three assistant chiefs. One of these last officers was Director of the War Plans Division and the principal strategic adviser of the Chief of Naval Operations. This office, comparable in prewar days and in the first months of the war to the Army’s War Plans Division, was responsible for the preparation of basic war plans, and of plans for the development and maintenance of naval forces for war. In prewar days, its director had been a member of the Joint Board, and its officers had represented the Navy on the Joint Planning Committee, the Aeronautical Board, and other joint groups. When war came most of its strategic planning functions were assumed by other offices. Finally in 1943, it was redesignated the Logistical Plans Division in recognition of the fact that its functions were limited to logistical planning and coordination. Thus, the Navy War Plans Division developed in a way quite different from the Army’s War Plans Division and, instead of becoming a super general staff, diminished in importance to become ultimately an office under the Assistant Chief of Naval Operations for Logistic Plans.

It was in his role as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, that Admiral King performed most of his duties as a member of the Joint and Combined Chiefs. Thus, it was the fleet staff, under a Deputy Commander and Chief of Staff, that assumed most of the burdens of strategic planning and direction of naval operations. For each of these functions, planning and operations, there was a separate division—the Plans Division and the Operations Division. The last, as the name implies, was concerned with the operations of fleets and naval forces and kept a constant check on their organization, combat readiness, and movements. Through this division, Admiral King maintained close contact with his fleet and force commanders, both surface and air, and exercised control over their operations. In general, this office performed the same functions as the Theater Group of the Army’s Operations Division but none of the other functions of that division.

The chief responsibility for strategic planning in the Navy resided in the Plans Division, Headquarters, Commander in Chief, United States Fleet. Like the Logistic Plans Division, CNO, it had its origins in the prewar War Plans Division, part of whose functions were transferred to the fleet staff in January 1942. When the two offices of CNO and COMINCH were combined in March 1942, the Plans Division was assigned additional responsibilities. Thus, it became the source for current and long-range strategic plans for the Navy, and its officers became the chief naval representatives on the various joint and combined committees. It was the director of this division, first Admiral Turner and then Admiral Cooke, who was the naval member of the Joint and Combined Staff Planners, as was his chief planner, usually a naval air officer. Other officers in the division sat on the Joint U.S. Strategic Committee and on various joint ad hoc committees as they were formed. The division’s main task was the preparation of estimates, studies, and plans for joint and combined forces, but it served also, much as did the Army’s Operations Division, as the coordinating agency for implementing joint plans and for liaison with other planning offices in the Navy Department and with the War Department General Staff.

The Japanese High Command

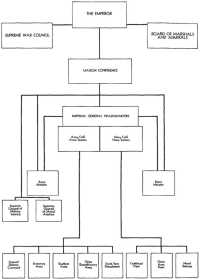

The Japanese high command, centered in Tokyo, was headed by the Emperor. Under the Japanese constitution, the Army and Navy were responsible solely to the Emperor, and the Chiefs of Staff of the two services, as imperial advisers, had direct access to the throne. The Emperor also received military counsel from two advisory bodies, the Board of Marshals and Fleet Admirals and the Supreme War Council. But the first exercised little influence and the second was consulted only on administrative matters. Real authority and control lay in the hands of the general staff and was exercised solely through the Chiefs of Staff. They alone were responsible for strategy and planning, and for the direction of operations.15

The organization of the Army and Navy General Staffs, with certain important exceptions, was similar. The Army staff was the larger, reflecting the greater power of its Chief of Staff and his control over training and other activities not shared by his naval colleague. It was organized into bureaus, the most important of which were the 1st (Operations), 2nd (Intelligence), 3rd (Transportation and Communications), and General Affairs Bureau. The main Navy staff consisted also of numbered bureaus, but the numbers did not correspond to those in the Army. The bureaus of both services, corresponding to G-Sections of Western general staffs, were usually headed by general and flag officers who exercised considerable influence on strategy and operations.

The conduct of the war was nominally in the hands of Imperial General Headquarters, acting directly under the authority of the Emperor. Representing the Army and Navy Chiefs of Staff and the War and Navy Ministries, Imperial General Headquarters was divided into the Army and Navy Sections, each acting independently. Army Section met in the Army General Staff offices, Navy Section in its own offices. At joint meetings, held about twice a week on the Imperial Palace grounds, both Chiefs of Staff presided. The Emperor occasionally attended these meetings, but rarely those of the individual service staffs.

The main weakness of Imperial General Headquarters was that it was not a single joint command, even an imperfect one. Rather it was a facade to cover two separate organizations with strong competing interests and rivalries. Army and Navy plans were developed separately in the Operations Bureaus of the General

Staffs, and plans and operations orders were issued not from Imperial General Headquarters as such but rather from its Army Section or its Navy Section. Joint operations were conducted by means of agreements between the Army and Navy, and separate orders were issued to Army and Navy commanders. Often Army-Navy disagreement over a proposed joint operation might result in delay or even the abandonment of the operation. Even when agreement was reached, the operation would normally be carried out not by a joint commander, but by separate Army and Navy commanders who would “cooperate” with each other under the terms of an Army-Navy “agreement.” On the rare occasions that saw the establishment of a joint operational command, supplies were still delivered through separate service channels, with consequent duplication, oversights, and mutual recriminations.

In the absence of any leadership on the part of the Emperor, the Army and Navy went their separate ways. But the Army was clearly the leading service. The position of General Tojo as both Premier and War Minister, along with his other Cabinet positions, undoubtedly lent the Army increased prestige, and Admiral Shigetaro Shimada, the Navy Minister during most of the war, followed a policy of trying to cooperate with the Army. There was, nevertheless, no coordinated Army-Navy policy. As one former Navy Minister put it, “As far as questions of Army operations are concerned, if the Chief of the Army General Staff says that we will do this, that is the end of it; and as far as the Navy operations are concerned, if the Chief of the Navy General Staff says we will do this, that fixes it; and should there develop

difference of opinion between the two chiefs, then nothing can be accomplished.”16 This division was a major weakness in Japan’s military establishment. The Japanese were well aware of this, and late in the war General Tojo proposed a real merger of Army and Navy Sections, a proposal that came to naught.

The link between Imperial General Headquarters and the Cabinet was the Liaison Conference. This conference, initiated briefly in 1937 after the reestablishment of Imperial General Headquarters, was resumed in 1940 and continued throughout the war. It had no formal status or authority, but was merely a framework for discussions between the civil government and the military authorities. The participants were the Chiefs of Staff, the Army and Navy Ministers (themselves active duty officers and largely under the control of the Chiefs of Staff) , the Premier, and such other ministers as might be necessary. Also present were the Cabinet secretary and the chiefs of the Military Affairs Bureaus of the Army and Navy Ministries. These last three functioned as a secretariat, and by their choice of agenda and their role in briefing the participants, they exercised a very strong influence on the outcome of the Liaison Conferences. Their presence, also, meant that the conference proceedings would soon become known to other members of the General Staffs, and the civilian participants were fully aware of the danger of assassination for anyone who raised too strong a voice against the plans of the military.

The Liaison Conference usually met twice a week, in a small conference room in one of the Imperial Palace buildings. There was no presiding officer, but the Premier occupied an armchair at the far end of the room and the others sat grouped around him. A variety of subjects was discussed at these meetings: war plans, diplomatic moves, the administration of occupied areas, and the assignment of national resources. Once a decision was reached at the Liaison Conference, it became in effect national policy by virtue of the official position of conference members, though the conference itself had no legal status.

On the surface the Liaison Conference appeared to be a meeting of equals. But appearances were deceptive. The military dominated the conference and dictated policy. “Imperial General Headquarters was in the Liaison Conferences,” explained General Tojo after the war, “and after they got through deciding things, the Cabinet, generally speaking, made no objection. Theoretically, the Cabinet members could have disagreed … , but, as a practical matter, they agreed and did not say anything.”17 Imperial General Headquarters was thus the source of Japanese national policy. “The Cabinet, and hence the civil government,” wrote former Premier Konoye in

his memoirs, “were manipulated like puppets by the Supreme Command. ...”18

On extremely important occasions, the Liaison Conference became an Imperial Conference, or a Conference in the Imperial Presence, by adding to its membership the Emperor, the President of the Privy Council, and other high officials. These meetings were much more formal that the Liaison Conferences. The participants made set speeches, previously written and rehearsed, all differences of opinion having been carefully resolved beforehand. The Emperor listened in silence, seated on a raised dais before a long, rectangular table, where the major participants sat facing each other. The three secretaries were grouped around a small table in the corner of the room. The Premier presided over the meeting, and each participant rose in turn, bowed to the Emperor, and stood stiffly in front of his chair while speaking. No one entered or left the room during the conference. At the conclusion of the presentations, the President of the Privy Council asked questions designed to elicit further information for the Emperor. These questions and answers were unrehearsed, but none of the representatives of the Cabinet dared deviate from the prearranged conclusions of the group. The Emperor, whose role was normally a passive one, did not speak. Only on very rare occasions, such as at the Imperial Conference on 6 September 1941 and the one in August 1945 that led to the Japanese surrender, did he venture to exercise his authority.19

Beneath the military high command structure in Tokyo, the Japanese had an extensive field organization. (Chart 4) In theory, field commanders were directly responsible to the Emperor, the commander in chief of the armed forces, but in fact came under the control of Imperial General Headquarters, acting for the commander in chief. There was no direct communication between the throne and the field. Basic orders were issued to field commanders as Imperial General Headquarters Army or Navy Section Orders, signed by the appropriate Chief of Staff, “by Imperial Command.” The detailed instructions necessary for the implementation of these orders, called Imperial General Headquarters Army or Navy Section Directives, were issued by the appropriate Chief of Staff without any reference to the throne. Recommendations of the field commanders to the throne or request for review of headquarters decisions had to be submitted to Imperial General Headquarters through the appropriate Chief of Staff.20

Unlike the Allies, the Japanese did not ordinarily organize their ground, air, and naval forces in the field under a single joint commander. Nor did they establish theaters of operations corresponding to geographical areas under a theater headquarters. Normally, the forces of each service in an area were placed under a separate Army or fleet headquarters whose commanders received orders through separate channels and worked together under the principle of cooperation. The highest Japanese command, equivalent to a U.S. Army overseas command or perhaps to

Chart 4—The Japanese High Command

an army group, was the general army, the size of which might vary widely, and which operated directly under the Army Section of Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo. There were three such armies during the early period of the war: Southern Army, Kwantung Army, and China Expeditionary Army. In each of these were usually one or more area armies, equivalent to U.S. field armies and consisting of units equivalent to a U.S. corps but called armies by the Japanese. There was no unit called a corps in the Japanese Army, Japanese divisions, brigades, and other separate units being assigned directly to armies. (An exception was the South Seas Detachment which served directly under Army Section, Imperial General Headquarters.) Thus, Southern Army, which conducted the opening operations of the war, consisted of four armies, two air groups, and several smaller units.

Unlike the Army, the Japanese Navy placed most of its combat forces under a single command, the Combined Fleet, which controlled all naval operations in the Pacific area and was roughly comparable to the U.S. Pacific Fleet. During the early months of the war, this fleet

had under its command six numbered fleets, two numbered air fleets, and the Southern Expeditionary Fleet. The numbered fleets, depending on their mission, contained surface, submarine, and air units as well as service and support elements and base forces. Most of the carrier-based air power of the Combined Fleet was concentrated in the 1st Air Fleet, which included four of Japan’s five carrier divisions. Land-based naval air power was for the most part assigned to the 11th Air Fleet, submarines to the 6th Fleet, and battleships to the 1st Fleet.21

This was the organization of the Japanese high command during the first year of the war. As the war progressed, adjustments were made, old organizations expanded and shifted, and new commands created to meet the needs of the changing strategic situation. But the basic structure, except for the creation of a Supreme Council in August 1944 to take the place of the Liaison Conference, remained unchanged throughout the war.