Chapter 25: Operations and Plans, Summer 1943

The art of war is simple enough. Find out where your enemy is. Get at him as soon as you can. Strike at him as hard as you can, and keep moving on.—GENERAL GRANT

The intensive activity that marked the preparations of the Central Pacific Area during the summer and early fall of 1943 for the projected offensive into the Gilberts and Marshalls had little or no effect initially on operations in the Solomons and New Guinea. There the forces of General MacArthur and Admiral Halsey, operating under CARTWHEEL, had gone into action at the end of June. The objective was the line Lae—Salamaua—Finschhafen—western New Britain—southern Bougainville, to be reached in eight months. From there, the Allies would be in position finally to drive on Rabaul and gain control of the Bismarck Archipelago.

CARTWHEEL Begins The Southwest Pacific

The first phase of CARTWHEEL, the occupation of Woodlark and of Kiriwina in the Trobriands, Nassau Bay, and New Georgia, began on the last day of June 1943.1 (Map III) Seizure of the first two

objectives MacArthur assigned to General Krueger’s newly formed ALAMO Force, Allied Air and Naval Forces furnishing support as required. This was the first amphibious operation in the Southwest Pacific Area and the planning was careful and complete. The VII Amphibious Force under Rear Adm. Daniel E. Barbey provided the ships to transport and land the assault troops; Allied Naval Force, the vessels to clear the sea lanes and protect the invasion force from enemy surface attack. General Kenney’s Allied Air Force undertook to neutralize distant air bases and furnish close air support. The ground troops were organized into two separate task forces, each of regimental size, one to take Woodlark, the other Kiriwina.2

Preparations for the landings were thorough, and May and June were busy months at Milne Bay and Townsville, staging points for the operation. Rehearsals

were held during the last days of June, though it was already known that there were no Japanese on either Woodlark or Kiriwina. As a matter of fact, advance parties landed . at both places before D-day and began to prepare for the arrival of the main body. The actual landings on 30 June, therefore, came as an anticlimax, and, aside from the confusion caused by the darkness and the unfamiliar waters, were made without difficulty.

As events turned out, the seizure of Woodlark and Kiriwina was unnecessary. Intended originally to provide the Southwest Pacific forces with advance fighter and medium bomber bases within range of Japanese airfields in the northern Solomons and in the Rabaul area, these islands were never really utilized for that purpose. Other sites captured during the Allied drive provided better bases when the time came. But the operation was of value in another way, for it provided the forces in MacArthur’s area with training and experience in amphibious operations they had not had before.

The landing at Nassau Bay, made simultaneously with the occupation of Woodlark and Kiriwina, was also unopposed. Situated on the New Guinea coast a short distance below the Japanese strongholds at Salamaua and Lae, Nassau Bay offered logistical advantages too good to miss. In Allied hands, it would open a water route along which supplies could be brought to the Australian troops then pushing forward from Watt, about twenty-five miles inland, toward Salamaua. Hitherto supplied by air and native carriers, the Australians had progressed slowly, building roads as they went. An operation against Nassau Bay had other advantages: it would give MacArthur a base from which to mount and support further advances up the New Guinea coast; and, if made at the same time as the Woodlark and Kiriwina landings, would serve to confuse the enemy. The drive to Salamaua from Nassau Bay would mask also the more important Allied drive against Lae, further up the New Guinea coast.

The operation itself, though it was unique in some respects, presented few difficulties.3 A force known as the MacKechnie Force and consisting of the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, augmented by support and service troops, was organized for the landing under the control of New Guinea Force.4 Staging out of Morobe, about forty miles south of Nassau Bay, the 1,000 men of the MacKechnie Force made the run to their objective in PT boats and landing craft on the night of 29 June. Despite the confusion created by rain and darkness, most of the men were ashore and ready for the enemy by daybreak of the 30th. The slight Japanese opposition that developed later was easily overcome and by 2 July the beachhead was secure and contact made with the Australians from Wau. The drive against Salamaua, about twenty miles to the north, could now begin in earnest.

South Pacific

Simultaneously with the landings at Nassau Bay and in the Trobriands, the forces of the South Pacific made their

Fijian Commandos with their New Zealand leader

first move into the New Georgia group in the central Solomons. This was by far the most ambitious undertaking of the first phase of CARTWHEEL and the forces allocated to the operation by Admiral Halsey were proportionately larger. Organized in accordance with the naval practice predominating in the South Pacific, these forces included Aubrey W. Fitch’s Aircraft, South Pacific; submarines of the Seventh Fleet on loan from MacArthur’s area; a naval covering force of carriers, battleships, cruisers, and destroyers commanded by Halsey himself; and, finally, the Attack Force, led by Admiral Turner and comprising all the ships, landing craft, supplies, and troops required for the initial landings.

The troops allotted to Admiral Turner for the invasion included the Army’s 43rd Division, a Marine Raider regiment (less two battalions) , a 155-mm. howitzer battalion and a Marine defense battalion, Fijian commandos, antiaircraft, construction, and service units, all organized into the New Georgia Occupation Force under Maj. Gen. John H. Hester, commander of the 43rd Division. Hester, therefore, functioned in a dual capacity, ‘as did most of the members of his staff—an arrangement that seemed to General Harmon to bode trouble for the future.5

The plan of operations for the conquest of New Georgia, designated TOENAILS, was dictated in part by geography and in part by enemy strength and dispositions. Composed of about a dozen comparatively large and hundreds of tiny islands extending in a northwest-southeast direction for 130 miles, the New Georgia group presents major problems for an invasion force. It is partially surrounded by a coral barrier, inside of which are large lagoons with shallow bottoms and dangerous coral outcroppings. Entrance into the group from the south is limited generally to narrow passages and channels calling for expert navigation. Munda Point on New Georgia Island, the largest of the group, is inaccessible to large vessels, but to the south, across Blanche Channel, lies Rendova and a sheltered harbor. To the northeast, extending the chain toward Bougainville, are Kolombangara and Vella Lavella.

Defending the central Solomons were about 10,000 Japanese Army and Navy troops, organized into two separate commands and operating under the direct control of Navy headquarters on Rabaul.

Army forces under Maj. Gen. Noboru Sasaki consisted of troops drawn largely from the 6th and 38th Divisions; naval forces, led by Rear Adm. Minoru Ota, of the Kure 6th and Yokosuka 7th Special Naval Landing Forces. Formed into scattered detachments these troops were strategically placed to repel any enemy attempt to seize the airfields and harbors in the area.6

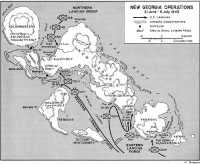

Admiral Halsey’s plan for gaining control of this complex of islands and reefs was a complicated one, but precise and detailed in all respects. Since the island of New Georgia could not be invaded directly, Halsey decided to gain first a foothold in the islands, from which he could mount and support the main assault. Rendova filled these requirements admirably and became the major objective of the preliminary landings to be made on D-day, 30 June. But it was not the only objective, for that same day South Pacific forces were to occupy three other positions in the New Georgia group—Segi Point, Wickham Anchorage, and Viru Harbor. The first was intended for use later as a fighter base, the last two as staging areas for supplies and reinforcements. (Map 8)

The invasion of New Georgia Island was scheduled to come four days after the preliminary landings. It was to be mounted from Rendova, in landing craft and small boats brought up for the purpose from Tulagi and Guadalcanal. The main force would land in the south and strike out for Munda, while a secondary force landed on the opposite side of the airfield near Enogai Inlet in Kula Gulf, a move designed to cut the Japanese line of communications. Once Munda was captured, South Pacific forces would mop up and secure the island, then move on up the New Georgia chain to Vila airfield on Kolombangara in preparation for the later invasion of southern Bougainville.

With the experience of Guadalcanal still fresh in mind, Halsey and his staff took every precaution to ensure adequate supplies for the invasion force and the prompt development of logistical facilities. Virtually every agency in the South Pacific contributed to this effort, appropriately designated DRY GOODS. During the months preceding the invasion, supplies poured into Guadalcanal, there to be stockpiled for the day they would be needed. Despite the shortage of service troops and port facilities and the destruction caused by a severe tropical storm, thousands of tons were unloaded across the Guadalcanal beaches by the end of June in an effort characterized by heroic improvisations and effective use of the newly developed 2½-ton amphibian truck, the DUKW. Guadalcanal also served as the staging area for part of the assault force, and the location of the 37th Division, elements of which were to stand by as area reserve for the operation.

Detailed and exact as these plans were, they had to be revised at the last moment. Unexpectedly, the Japanese sent reinforcements toward Segi Point, one of the four preliminary landing sites of the Allied invasion earmarked for use as an advanced lighter strip. To avert the loss of this potential base, Halsey quickly altered his plans, moving up the date of the landing and substituting elements of

Map 8: New Georgia Operations

the 4th Marine Raider Battalion for the original landing force. No time was lost. By the night of 20 June, the marines were on their way toward Segi Point in two fast destroyer-transports. Next morning they landed without opposition, beating out the Japanese.

The remainder of the plan for the preliminary landings on 30 June, with one exception, was carried out as scheduled, but not without considerable confusion and unexpected difficulties. The night was dark, the weather foul, and the sea rough. At Wickham Anchorage, the troops started to land on the wrong beach and had to re-embark. On the second try, the small boats heading blindly toward shore were scattered by larger craft. Six were lost on the reef. The landing, when it was made, came at the wrong beaches and was marked by an “impressive disorganization.” Fortunately, there were no Japanese on hand and the troops were able to re-form before the shooting began. By 4 July Wickham Anchorage was secure.

The Viru landing was not made at all. The Japanese were already in possession,

and the assault force, after waiting outside the harbor for the Marines from Segi to take the place by overland assault, finally disembarked at the latter site, twelve miles away. The next morning, Viru Harbor was in American hands.

At Rendova, where the bulk of the troops were to land, the weather and darkness also had their effect. One ship ran aground on a reef, and the specially trained “Barracudas”—C and G Companies, 172nd Infantry—who were to cover the major landing came ashore some miles from their destination at Rendova Harbor. Thus, when the first boats of the main assault force moved toward the beaches in the first light of dawn, they carried with them Turner’s admonition, “You are the first to land—expect opposition.”7 But the warning proved unnecessary. The 120-man Japanese garrison, taken by surprise, offered only desultory opposition and by 0800 the assault force was safely ashore. The operation, remarked General Harmon, who was present during the landing, “was splendidly executed and reflects great credit on Admiral Turner and his Staff and Commanders. ...”8

Though the Rendova garrison offered little opposition on the ground, Japanese air and artillery went into action promptly once the enemy realized what was happening. Coastal defense guns from Munda Point and from Baanga Island opened fire on Turner’s naval escort, scoring a hit on the destroyer Gwin. At 1100 came the first of several air attacks, one of which resulted in the loss of the flagship McCawley. But the Americans gave as much as they got and knocked down most of the attacking aircraft.

The chief obstacle to the landing came not from the Japanese but from the reefs, shallow waters, and soft red clay roads of Rendova. These combined to impede unloading operations and to create utter confusion on shore, where heavy mud-bound trucks clogged all routes to the supply dumps. Soaked radios, poor packaging, and inadequately marked containers added further to the troubles of the beach masters. Finally General Hester was forced to call a halt to the unloading of vehicles until the supply situation ashore was cleared up. But this measure proved inadequate and ultimately the supply experts revised their plans for a supply base at Rendova.

The main landing on the southern coast of New Georgia, west of Munda Point, came 2 July, after several false starts. Three days later, a second force came ashore on the west coast of the island at Rice Anchorage. While this force worked its way into position to cut off the Japanese defenders from their line of supply and reinforcements—a mission it never actually accomplished—the Army troops to the southeast began their arduous march through the jungles toward the Munda airfield.

From the start, the campaign went badly. Heat, tangled undergrowth, and the determined opposition of the enemy slowed the advance and brought heavy casualties to the inexperienced troops of the 43rd Division. On 7 July, elements of the 37th Division on Guadalcanal were ordered forward, and three days later, in a vain effort to inject fresh spirit into the worst-hit of his two front-line

RENDOVA Commanders. From left, Brig. Gen. Leonard F. Wing, Admirals Wilkinson and Turner, and General Hester.

RENDOVA Landing Forces being carried to their objective in Higgins boats.

regiments, General Hester relieved its commander and most of the regimental staff. Despite these efforts, the offensive ground slowly to a halt.

If General Hester was concerned with the speed of his advance, so also were his superiors. Harmon’s misgivings that Hester “did not have enough command and staff ... to watch the whole show as well as keep a close hold on his Division” had led him, before D-day, to instruct Maj. Gen. Oscar W. Griswold, XIV Corps commander on Guadalcanal, to be ready to take over if necessary. “Thought I would watch the operation,” he later explained to General Handy. “and if it didn’t go properly throw in Griswold and the advance echelon of XIV Corps staff.”9 Hester’s conduct of the Rendova operation gave Harmon no reason to believe that such a change would soon be necessary. As a matter of fact, he had nothing but praise for the New Georgia Occupation Force commander.10

By 5 July, after the drive to Munda began, Harmon had apparently revised his views. Though he did not at that time feel that Hester should be replaced, he did believe that the New Georgia commander needed more staff officers so that he could devote his time to operations. He recommended to Halsey, therefore, that the forward echelon of the XIV Corps staff should move up to New Georgia about 8 July and that Griswold should take over the Occupation Force after the capture of Munda.11

Admiral Turner, commander of the entire New Georgia assault force and therefore Hester’s immediate superior, was “in violent disagreement” with this proposal. It was Harmon’s belief that the admiral “was inclined more and more to take active control of land operations,” and he saw little hope of reaching agreement with him. He therefore appealed directly to Halsey, who, on 6 July, decided in favor of the Army commander. The relief of Hester as commander of the New Georgia Occupation Force—there was no thought of relieving him of his division—would be decided later.12

But Turner was not content to leave the matter there and presented his case directly to Halsey, as he had every right to do. Regretting the necessity for disagreeing with Harmon, Turner nevertheless argued strongly for the retention of Hester as commander of the Occupation Force. To replace him with Griswold, Turner contended, would deal “a severe blow” to the morale of troops on New Georgia. Moreover, he could see no reason for a change, in view of Hester’s admirable conduct of operations. Harmon disagreed, and it was on his advice that Halsey acted. Thus, on to July, General Griswold received orders to go to New Georgia and at a date to he specified later—presumably after the capture of Munda, assume command of the Occupation Force. Turner would continue to support the operation but would no longer have authority over the ground forces.13

This matter decided, Harmon remained at his headquarters in Nouméa to await the capture of Munda. On the morning of the 13th, he dictated a letter to General Handy in Washington. His mood was optimistic and he forecast early success. “Hester,” he reported, “is close to Lambeti Point and generally closing in on Munda. Liversedge [commander of the force that had landed at Rice Anchorage] holds Enogai Inlet and is astride the junction of the Munda–Bairoko–Enogai trails.”14 The letter was never sent, for that same morning brought alarming news from Griswold, recently arrived in New Georgia. The operation, Griswold reported, was going badly, with the 43rd Division about ready “to fold up.” In his opinion, the division would “never take Munda,” and he advised that the 25th Division and the remainder of the 37th be sent quickly to New Georgia “if this operation is to be successful.”15

The promptness with which higher headquarters acted on receipt of this news is a mark of the efficiency of the South Pacific command and the close cooperation between the Army and Navy commanders in the area. Harmon and Halsey went into conference immediately, and before the meeting was over Halsey had made his decision. Harmon was to assume complete control of ground operations in New Georgia with full authority “to take whatever steps were deemed necessary to facilitate the capture of the airfield.”16

This was the second time that Halsey had thus expressed his confidence in the Army commander by making him virtually his deputy for ground operations,17 and Harmon assumed his new duties with dispatch and in a confident spirit. First he ordered Griswold to be ready to assume command “on prompt notice,” and to prepare plans for resuming the offensive. The reinforcements he needed, Harmon assured him, would be available at the proper time. Then at about noon of the 14th, Harmon left by plane for Guadalcanal, from where he could oversee the movement of reinforcements and reach the front lines in short order. That same day, a regimental combat team of the 25th Division was alerted for movement to New Georgia on twelve hours’ notice.18

The next move was Halsey’s. On 15 July, he relieved Admiral Turner of command in the South Pacific and transferred him to the Central Pacific, where he was to head the amphibious forces in the coming offensive. This transfer, based on orders from Nimitz and seemingly unrelated to events in New Georgia, effectively removed from the scene the chief architect of the New Georgia plan and Hester’s most effective champion. His successor, Rear Adm. Theodore S. Wilkinson, assumed command that same day.

General Hester’s relief as commander of the New Georgia Occupation Force followed only a few hours later. Even before Turner’s departure, Griswold had his orders to assume command of the Occupation Force at 2400, 15 July. At that time, Griswold formally took over control of ground operations on New Georgia under Harmon. Hester’s command of the 43rd Division was not affected by this change.

The shift in command of the New Georgia operation accomplished no miracles. The jungle remained as impenetrable as ever, the heat as intense, and the Japanese as determined as before to hold Munda airfield. It took time to bring in reinforcements and reorganize the troops for a fresh assault. By 25 July, General Griswold was ready to resume the offensive. The attack opened on the morning of the 25th when air and naval forces went into action and Army artillery battered the Japanese in their dugouts. When the artillery lifted, the ground troops, after throwing back a Japanese counterattack that penetrated to the 43rd Division command post, made their way forward slowly through the jungle. The going was tough and 43rd Division troops, already tired, failed to keep pace with the advance. Finally, on 29 July, Harmon sent in Brig. Gen. John R. Hodge, Assistant Division Commander, 25th, to replace Hester. The general, he felt, was tired—“had lost too much sap.” He had carried too much of a load from the start of the campaign and had lost touch with his own troops. For that Harmon was willing to take most of the blame. He had failed to see, he confided to his chief of staff, that one man could not handle both the division and Occupation Force, “that a Corps commander and staff were necessary.”19

The relief of Hester coincided with the Japanese decision to pull back to their final line in front of the airfield. Thereafter the advance of the American troops was more rapid, and Harmon was able to report to Halsey on 1 August that “there is no presently valid reason for doubting its success.”20 But he still expected to meet strong opposition and doubted that the fight would be over in time for tea tomorrow.”21

The end was closer than Harmon thought, for the Japanese were at the end of their rope. By 3 August, the Americans had reached the edge of the Munda airfield and circled it on the north. On the 4th they overran the field. “Open season in Nips today ... ,” Harmon wrote. “All are determined that tomorrow’s action spells bad news for Tojo. The sun shines brightly.”22 Next day, despite the rain, the last enemy resistance was overcome. At 1410, Munda was in American hands.

The one great lesson of the New Georgia campaign was that it demonstrated strikingly the consequences of a failure to adhere to the principles of unity of command in joint operations. The relief of General Hester was the culmination of a series of events that had their origin in faulty command arrangements. Admiral Turner, as commander of the Attack Force, exercised his control of the ground forces in an active manner and showed no disposition to relinquish this control even after the troops were established ashore.

Munda Airfield fell to American forces on 4 August 1943

And not only were the 43rd Division commander and his staff improperly used, but ground units were shuffled in a manner that no experienced Army commander would have tolerated. “This incident,” wrote General Hull some years after the event, “demonstrates the fallacy of placing forces of one service under the immediate control of an officer of another service who is not trained in the organization and tactics involved in the operation of that service.”23

Strategic Forecast, August 1943

As American troops were making their way slowly through the jungles of New Georgia toward Munda airfield, the planners in Washington were preparing for their next full-scale conference with the British, to be held in Quebec in mid-August. The chief problems facing the

On New Georgia. Generals Twining (left), Harmon, Griswold, and Breene, and Brig. Gen. Dean G. Strather

Americans were those connected with the war in Europe; the time had come it seemed to them for a final decision on the cross-Channel attack.

But the war in the Pacific also required attention. There was as yet no approved long-range plan for the defeat of Japan, no clear decision on the area where the main effort would be made, or even whether the invasion of Japan would be necessary. However important these matters may have been, they were not, in the summer of 1943, urgent except insofar as they affected plans for the immediate future. Thus, though the planners continued their search for a long-range plan and produced numerous valuable studies in the process, they did so with a recognition that final agreement on such a plan would probably have to await the settlement of numerous unresolved problems, not the least of which was the future role of the Soviet Union and China in the war against Japan.

Though handicapped by the lack of a long-range strategy into which to fit their plans for the immediate future, the planners proceeded as best they could to outline a pattern of operations to be followed in the Pacific during the next eighteen months, utilizing the studies already made and tentatively approved as the

basis for planning. Central Pacific strategy, at least through the seizure of the Marshalls, was clear, but there was some doubt as to where Nimitz’ forces would go after that. CARTWHEEL also set out a firm schedule for MacArthur and Halsey, but doubts had recently been expressed on the necessity for the capture of Rabaul. To clear up these and other matters, the planners turned to MacArthur for his advice.24

MacArthur’s answer came early in August in the form of a revision of his RENO plan outlining the steps by which he intended to return to the Philippines.25 These steps, or operations, were divided into six phases, the first of which was identical with CARTWHEEL. By March 1944, according to RENO II, forces of the Southwest Pacific would have secured the objectives outlined in Phase I—control of the Bismarck Archipelago, including the capture of Rabaul, and of eastern New Guinea. Phase II, which would begin on 1 August, would carry the advance into the Hollandia area of Dutch New Guinea, bypassing Wewak. This move was to be accompanied by the invasion of the Kai, Aroe, and Tanimbar Islands in the Netherlands Indies off the southwest coast of New Guinea, a move designed to guard the left flank of the main drive up the northwest coast of the dragon-shaped island. The remainder of 1944 and the early months of 1945 would be devoted to Phase III operations in northwest New Guinea and would culminate in the capture of the Vogelkop Peninsula, head of the New Guinea dragon.

During the next two phases of RENO, for which MacArthur set no dates, forces of the Southwest Pacific would continue their advance along the Netherlands Indies axis to seize the islands between New Guinea and the Philippines, thereby gaining control of the Celebes Sea. At the same time the Palau group in the western Carolines was to be captured, either by MacArthur or Nimitz, to protect the right flank of the advance into Mindanao, the final phase of RENO II.

In its general features, RENO II clearly reflected MacArthur’s strategic and tactical concepts and his view of the importance of the Philippines in the war against Japan. It called for the capture of Rabaul as a necessary preliminary to control of the Bismarck Archipelago, and for bypassing Wewak, whose capture General Marshall had suggested in July. Implicit in the plan was the view that the New Guinea route was superior to the Central Pacific, and that the step-by-step advance under cover of land-based aircraft was the safest course to follow. And it repeated the familiar arguments for the concentration of Pacific resources on the drive up the New Guinea coast as the most effective way to exploit the Allied advantages in that area and to speed up the tempo of the war.

Though MacArthur’s schedule of operations for 1943 and 1944 was generally acceptable in Washington, his views on broad Pacific strategy found little support. Not only had the Joint Chiefs of Staff and their planners become convinced of the desirability of the Central Pacific route, but they had also apparently made up their minds about Rabaul. Thus, the program drawn up by the

planners for the remainder of 1943 and 1944 gave full weight to the Central Pacific offensive and called for the neutralization rather than the capture of Rabaul. The reconciliation of this program with MacArthur’s promised to be a difficult task.

In the opinion of the planners, Admiral Nimitz’ forces, after they had completed the operations already scheduled in the Gilberts and Marshalls, should continue westward into the Carolines, taking first Ponape, then Truk, “the key Japanese position in the Central Pacific,” and finally Yap and the Palau Islands.26 From there, at some indefinite day, the forces of the Central Pacific would move into the Philippines. Though no operations were scheduled for the Marianas, the planners indicated their intention of preparing an outline plan for the recapture of Guam in the near future.

The strategic objective of the program developed in Washington early in August was the line Palaus–Vogelkop Peninsula. This aim fitted in perfectly with MacArthur’s RENO plan, though the operations envisaged in Washington were not identical with those outlined by MacArthur. For one thing, the Washington planners ruled out the capture of Rabaul as an unnecessary move and “an intolerable drain” on resources and manpower. For another, they included in their program the seizure of Wewak, despite MacArthur’s assertion that the operation “would involve hazards rendering success doubtful.”27 Finally, they omitted altogether the operations MacArthur had scheduled in the Netherland East Indies to protect the left flank of his advance along the New Guinea coast.28

The similarity of the Washington and RENO plans was more marked than the differences. In both, MacArthur’s and Halsey’s forces were to complete CARTWHEEL; next, they were to gain control of the Bismarck Archipelago. This last they were to accomplish, under the Washington plan, in three phases: first, seizure of the islands along the eastern border of the Archipelago (New Ireland, New Hanover, and St. Matthias); second, capture of the Admiralty Islands to the north and west; and, finally, occupation of the New Guinea coast line as far west as Wewak. These tasks completed, MacArthur was to continue along the northwest coast of New Guinea in a series of amphibious and airborne operations that would take him to the Vogelkop Peninsula by the end of 1944.29 Or so the planners believed.

The timetable for this ambitious program—which also included operations in the China-Burma-India Theater—was carefully worked out to exploit the advantages inherent in an advance along two widely separate routes. (Table 5) Thus, while Nimitz prepared for the Gilberts invasion in November 1943, MacArthur and Halsey were to continue their own offensives in New Guinea and the northern Solomons. In January 1944 Nimitz would go into the Marshalls and

Table 5: Timetable of Pacific Operations, August 1943

| Target Date | Central and North Pacific | Southwest Pacific | South Pacific |

| 15 August 1943 | Kiska | ||

| 1 September | Lae, Madang | ||

| 15 October | Buin, Faisi | ||

| 15 November | Gilberts | ||

| 1 December | New Britain (Cape Gloucester) | Kieta, Buka (Neutralize) | |

| 11 January 1944 | Marshalls | ||

| 1 February | Neutralize Rabaul, Wewak | ||

| 1 May | Kavieng | ||

| 1 June | Ponape | Manus | |

| 1 August | Hollandia | ||

| 1 September | Truk | ||

| 15 September | Wadke Island | ||

| 15 October | Japan Island in Crelvink Bay | ||

| 30 November | Manokwari on the Vogelkop Peninsula | ||

| 31 December | Palau |

the next month MacArthur would assault Wewak. These operations concluded, Halsey would occupy Kavieng in New Ireland in May, and then in June the forces of all three would go into action simultaneously against Ponape, Manus, and Hollandia. When Nimitz moved out against Truk in September, MacArthur was to start his advance toward the Vogelkop Peninsula. By the end of the year, if all went well, both commanders would have reached their objectives and would he standing on the Palaus-Vogelkop line.

The planners were entirely confident that the resources required to carry out this program could be made available in time. They expected also that if forces were idle in one area they could be transferred to the other so that the momentum of the drive would not be lost. But the Washington authorities were careful not to commit themselves in advance to such transfers or to any single theater, agreeing only that if there were any conflicts “due weight should be given to the fact that operations in the Central Pacific” promised a more rapid advance that operations elsewhere.

On 7 August, just one week before the scheduled Quebec Conference, the Joint Chiefs met to discuss, among other things, the program outlined by the planners.30 On the whole, they thought it a sound plan and accepted most of it without question. The one important point relating to the Pacific that came up during the discussion was Admiral King’s suggestion for greater flexibility in the Central Pacific so that Nimitz could advance north from the Carolines, toward Japan as well as west toward the Philippines.

What he had in mind was the possibility of moving into the Marianas, either in conjunction with or instead of the seizure of the Palaus.

Capture of the Marianas was a project King had long favored. At the Casablanca Conference, seven months before, he had described these islands as “the key to the situation because of their location on the Japanese line of communication.”31 By the time of the TRIDENT Conference in May, he had found additional reasons for going into the Marianas but the program then approved had not included any operations for their capture.32 Now, in August, he again emphasized the importance of these islands. This time he secured from his colleagues their assent to inclusion in the approved program for 1943–1944—the statement that “it may be found desirable or necessary to seize Guam and the Japanese Marianas, possibly the Bonins” after capture of Truk. Such a move, it was asserted, “would have profound effects on the Japanese because of its serious threat to the homeland.”33 These and other minor changes were quickly made and on 9 August the Joint Chiefs gave their approval to the program. Soon after, the American delegation left for Quebec.

The main business of the conference at Quebec was the war in Europe. The British, as a matter of fact, had momentarily hoped to avoid altogether any discussion of Japan, but the Americans would not let them do so. The war in the Pacific had an urgency for them it did not have for the British. Moreover, strategic plans in one theater were bound to affect plans in the other. As General Marshall observed early in the conference, “it was essential to link Pacific and European strategy.” And Admiral King did not fail to point out that the inability of the Allies to take Rabaul in 1943, as originally planned, was a direct result of the failure at Casablanca to consider the requirements of the Pacific war in relation to the war in Europe.34

It was not until 17 August, after they had discussed the war in Europe at length, that the Combined Chiefs turned to the American program for operations against Japan in 1943–44.35 The debate that followed dealt largely with the situation in Southeast Asia, the area in which American and British views differed most markedly. On the Pacific side, recognized by now as virtually an American domain, harmony prevailed. Only one important point did the British raise. Would it not be advisable, they asked, to curtail operations in New Guinea and make the main effort through the Central Pacific rather than advance equally up both fronts? The forces thus released, they suggested, could then be used in the cross-Channel attack for which the Americans were pushing so hard.36

American strategic planners at the Quadrant Conference. From left: Generals Handy, Wedemeyer, and Fairchild, and Admiral Willson

The idea that the main effort should be made in the Central Pacific was not a new one. The Americans had discussed it frequently among themselves and there were many, especially in the Navy, who favored it. King himself would have preferred such a strategy, but before the British he hewed firmly to the party line and championed the cause of the Southwest Pacific. The dual advance, he declared, was more advantageous than an advance along one route. Each complemented the other; together, they produced greater results than could either alone and opened up additional areas of exploitation. Thus the two forces could converge on the Philippines or, one could go north from Truk into the Marianas. Furthermore, Marshall observed, the Japanese were losing heavily in New Guinea.37

The British suggestion that the savings effected by limiting operations in New Guinea be applied to OVERLORD held no appeal for the Americans, despite their desire to secure a commitment for the cross-Channel attack. The advocates of the Central Pacific strategy saw it as an opportunity to speed up the tempo of the war by concentrating on the area that promised the most decisive results, not as a means of providing additional forces for Europe. If the allocations to MacArthur were cut back, then these

The Combined Chiefs at Quebec

From left foreground. Lord Louis Mountbatten, Admiral Pound, General Brooke, Air Chief Marshal Portal, Field Marshal Dill, General Ismay, Brigadier Harold Redmond, Comdr. R. D. Coleridge, Generals Deane, Arnold, and Marshall, Admirals Leahy and King, and Captain Royal.

resources, declared King, should go to Admiral Nimitz for the advance across the Central Pacific. Moreover, General Marshall pointed out, most of the forces required for MacArthur’s advance in New Guinea were already in or en route to the theater and, in any case, could not be employed in Europe. To curtail MacArthur’s operations, therefore, would not produce additional forces for OVERLORD.38

Having stirred up this brief tempest, the British backed off. They did not mean, they said, that operations in New Guinea should be discontinued. All they had in mind was to limit MacArthur’s forces to a holding role and to assure themselves that the Americans did not intend to recapture all of New Guinea. With this latter point, MacArthur himself would have agreed; but certainly not with the former. Neither his plans nor those of the Washington planners contemplated such a role for the Southwest Pacific. But since the British did not pursue the question further at this time, the discussion was dropped.

Only one other time during the conference did the British seek to limit operations in New Guinea and that was when

the Combined Chiefs were considering their interim report to the President and Prime Minister on 21 August. This time the British approached the matter from another angle. They had no objection to the American program in the Pacific for 1943–1944, they declared, but thought it should include a statement requiring the review of operations in New Guinea “to ensure that the results likely to be obtained are commensurate with the effort involved.”39 There was little reason for such a request since the Joint Chiefs, as a matter of course, kept all American operations under constant review. Moreover, such a statement might easily be interpreted as an expression of a lack of confidence in General MacArthur. Already, the Americans pointed out, MacArthur had been disappointed by the refusal to provide him with forces he had asked for. The British suggestion could serve only to add to his disappointment and to have “a disheartening effect upon him.” When this was pointed out, the British promptly withdrew their suggestion, explaining that they had had “no idea” that the final report would be sent to General MacArthur.

Though the war against Japan continued to take up much of the time of the conferees at Quebec, there was no further discussion of the Pacific program for 1943–1944. The Combined Chiefs of Staff accepted the American plan in toto and incorporated it in the final report that the President and Prime Minister approved on the last day of the conference.40 This action, in effect, placed the seal of approval on the specific operations outlined in the broad program. For the Central Pacific, this meant the seizure of the Gilberts, the Marshalls, Ponape and Truk in the Carolines, and, finally, either the Palaus or the Marianas, or both. For MacArthur, the decision of the Combined Chiefs meant the disapproval of his plans to take Rabaul. But it was also an assurance that he would not be limited to a holding mission and that operations in his theater would not be curtailed. Specifically, his task for the next sixteen months would be to complete CARTWHEEL, gain control of the Bismarck Archipelago, neutralize Rabaul, capture Kavieng, the Admiralties, and Wewak, then advance along the northwest coast of New Guinea to the Vogelkop Peninsula in a series of “airborne-waterborne” operations. Nothing was said about the Philippines, but presumably sometime in 1945 he could launch his invasion of the islands, in conjunction with a drive from the Central Pacific.