Chapter 28: The Execution of Strategy: Pacific Operations, August–December 1943

The conduct of war resembles the workings of an intricate machine with tremendous friction, so that combinations which are easily planned on paper can be executed only with great effort.—CLAUSEWITZ

While plans for the future were being made in Tokyo and Washington, the war in the Pacific went forward rapidly on every front. Between the summer of 1943 and the end of the year, Allied forces in the Pacific hit the enemy from every direction in a bewildering variety of operations that set the pattern of Pacific warfare. These operations were everywhere marked by the employment of air, ground, and naval forces—American, Australian, and New Zealand—under a unified command and a timetable that called for the most careful planning and coordination. Whatever differences existed between the services or among the Allies, operations against the enemy were conducted in a spirit of cooperation and mutual good will.

New Georgia

Capture of the Munda airfield by Admiral Halsey’s forces on 5 August had signified the end of only one phase, though an important one, of the New Georgia campaign.1 There were still a large number of Japanese on New Georgia Island and they would have to he tracked down and captured or killed before the island could be considered secure. Then the remaining islands in the group—Arundel, Baanga, Gizo, Kolombangara, and Vella Lavella—would have to be occupied or neutralized. Only then would the campaign he ended and the forces of the South Pacific free to move on into the northern Solomons.

Even before Munda had fallen, General Griswold, XIV Corps commander, had taken steps to prevent the escape of the Japanese on New Georgia. Patrols had gone out to encircle the airfield and to cut all routes of escape. Following them had come stronger forces. Leaving the 43rd Division to guard the airfield, Griswold had sent elements of the 25th Division north along the inland trail from Munda to Bairoko Harbor, where

a mixed force of Marine and Army troops had been trying unsuccessfully to overcome a small Japanese garrison. A second column, consisting of elements of the 37th Division, Griswold sent along the west coast of the island toward Zieta.2

The Japanese were not so easily trapped. Having withdrawn successfully from Munda on 3 August, the Army and Navy commanders in the central Solomons, General Sasaki and Admiral Ota, now decided they could no longer hold New Georgia with the troops at their disposal. Leaving a small force to harass the Americans and maintain a foothold on the island against the day of their return, they transferred their remaining troops to other islands in the group: to Baanga, which lay within artillery range of Munda; to Arundel, covering the narrow water route northward from Munda; and to Kolombangara, where Sasaki established his headquarters. Reinforcements had been promised from Rabaul, and with these Sasaki and Ota hoped ultimately to launch a counteroffensive and drive the enemy from New Georgia.3

The Americans required more than two weeks of hard fighting to clear the small Japanese force left behind by Sasaki on New Georgia. (Map 10) By that time, mid-August, all Japanese hopes for a counteroffensive had disappeared. The reinforcements sent by higher headquarters at Rabaul, about 1,500 Army and Navy troops, had been intercepted in Vella Gulf on the night of 6-7 August and virtually destroyed. Only about 300 men had survived to reach Vella Lavella. Next had come orders to withdraw from Baanga, where the Americans had already landed, and to cancel all plans for counterattack. Sasaki’s mission now was to hold out as long as possible to give the Japanese in the northern Solomons time to make ready for the next Allied advance. No more reinforcements would be forthcoming; Sasaki would have to do the job with what he had—a mixed force of about 11,000 men, most of whom were concentrated on Kolombangara.

Meantime, Admiral Halsey had revised his own plans. The prospect of “another slugging match” such as the one at Munda to capture the airfield at Vila on Kolombangara, the objective set in the original plans, was not an attractive one.4 No one wanted to do it, but how could it be avoided? With the advantage of hindsight, the answer seems simple enough—bypass it, neutralize it, and go on to Bougainville. The planners on Halsey’s staff were thoroughly aware of the advantages of bypassing enemy strongpoints. Though not yet publicized by that name, the maneuver was a well-understood military principle. As General MacArthur wrote: “The system is as old as war itself. It is merely a new

Map 10: South Pacific Operations, June–November 1943

name, dictated by new conditions, given to the ancient principle of envelopment. … It has always proved the ideal method for success by inferior in number but faster moving forces.”5

The idea of bypassing Kolombangara, therefore, was a natural one. The obvious alternative was Vella Lavella, fifteen miles to the northwest and defended by only a handful of Japanese. A landing there would certainly be easier, if intelligence estimates were correct, and would have the further advantage of placing South Pacific forces even closer to their next objective, Bougainville, than a landing at Kolombangara. Halsey liked the idea when it was proposed to him in July, but before he would buy it he wanted the answer to certain questions. Could fighter aircraft be based there to support the invasion of Bougainville? Could the Japanese field at Vila be interdicted by artillery during the landing and could Sasaki’s line of supply be cut so that the Kolombangara garrison could safely be left “to die on the vine”?6

The answers were provided by a reconnaissance party, which reported at the end of July that a field could be built near Barakoma at the south end of the island. Also reassuring, though incorrect, was the news that there were no Japanese in the area. On the basis of this information and the recommendation of Admiral Wilkinson, Turner’s successor, Halsey issued orders for the capture of Vella Lavella on 11 August. The invasion force would consist of a regimental combat team from the 25th Division, plus supporting and service troops, under Brig. Gen. Robert B. McClure. Army and Navy construction troops would go in shortly after the invasion to build the airfield and a small naval base.7 Three separate naval forces, including aircraft carriers and submarines, would provide close support for the landing and stand ready to head off any Japanese attempt to interfere with the invasion. Aircraft from New Georgia would cover the landing also and in addition strike Japanese bases in the Shortlands and on Bougainville. Griswold’s contribution to the operation would consist of the capture of Arundel Island, immediately to the south of Kolombangara. With artillery emplaced there he could take Vila airfield under direct fire and render it useless for the period of the campaign.

D-day for the Vella Lavella, invasion was 15 August, and on the 12th an advance party left Rendova to mark the beaches at the landing site. News had also come from the Australian coast watcher there that about forty Japanese had been taken prisoner by the natives, and the advance party was given the additional task of collecting these prisoners. It later developed that the Japanese, whose number had increased to about 300, had not been captured at all. Despite this disturbing news, the advance party held the beachhead for the main invasion force, capturing seven Japanese in the process.

D-day was a complete success. The assault troops landed without interference, and supplies were unloaded with a minimum of confusion. Ground operations thereafter consisted largely of mopping up small groups of Japanese, an activity that occupied the troops until almost the end of September. By that time Arundel had fallen to Griswold’s troops after a long and unexpectedly difficult fight by the small Japanese garrison. But the major Japanese resistance came from the air, and for almost a month Allied and Japanese planes fought it out over the central Solomons.

While this battle was in progress, General Sasaki began to make plans for his escape. He had accomplished his mission and could now give up the central Solomons to the enemy. But to get his men through to southern Bougainville where they were needed to fight again was no easy task. The evacuation of Kolombangara began on 28 September. By transport, barge, landing craft, and other types of vessels, the Japanese troops made their way northward under cover of darkness. Of the 11,000 men Sasaki had gathered at Kolombangara, more than 9,000 made good their escape.

Finally, on the night of 6 October a strong destroyer force came down with transports to pick up the last survivors. A small group of American destroyers, outnumbered three to one, intercepted the Japanese, but suffered heavy losses and was unable to prevent the rescue. With this engagement, known as the Battle of Vella Lavella, the New Georgia campaign came to an end. It had lasted more than four months and had required far larger forces than had been estimated. But at its conclusion, the forces of the South Pacific were at the threshold of Bougainville, whose invasion was less than a month away.

Salamaua to Sio

While Halsey was thrusting forward the right leg of the Allied advance toward the Bismarcks deep into enemy territory, MacArthur was pushing the left leg forward into the Huon Peninsula. (Map III) During July and August, when fighting raged the fiercest in the Solomons, Australian and American troops advanced slowly toward Salamaua. This was only a diversionary move, intended to deceive the enemy. Lae was the real objective and Allied Air and Naval Forces operations during this period were directed as much toward its seizure as to support of the Salamaua campaign. Thus, by the time Salamaua was captured on 12 September, General Kenney’s air forces had struck a heavy blow at Japanese air power, and Admiral Kinkaid’s destroyers and PT boats had cut deeply into the enemy’s thin line of communications. Ground troops, too, had taken a heavy toll, for General Imamura, determined to hold Salamaua, had placed there the bulk of the 10,000 men available for the defense of the Lae–Salamaua area.8

Operations against Lae began even before Salamaua had fallen. Allied Air Forces planes began the preassault bombardment on 1 September, while continuing to neutralize Japanese fields in New Guinea and New Britain. On the morning of the 4th, troops of the 9th Australian Division came ashore in the vicinity of Lae, one brigade landing sixteen miles east of the town and another four miles closer in. A Japanese effort to break up the landing with an air attack proved unsuccessful and by evening of D-day the Australians had secured the beachheads and begun the drive westward toward Lae.

Nadzab was captured the next day, 5 September, by the 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment in the first Allied airborne operation of the Pacific war. Flown in from Port Moresby in ninety-six C-47’s, accompanied by over 200 bombers, fighters, and other aircraft, the paratroopers reached Nadzab without mishaps. At 1020 the jump began, and within five minutes the entire regiment was dropping gently toward the ground. Three men were killed and thirty-three injured during the drop, but once on land there were no further casualties. The Japanese had been taken completely by surprise, and had failed to provide any reception whatever.

With the strip at Nadzab in his possession, General MacArthur sent in the airfield engineers and then the 7th Australian Division. On the 10th, this division began its advance eastward

Australian troops go ashore near Lae

down the Markham Valley toward Lae, in concert with the westward drive of the 9th Australian Division along the coast. Lae was now virtually cut off, and the Japanese wisely decided to pull out and make their way overland as best they could to the north shore of the Huon Peninsula. Thus, the Australians met no strong organized resistance and on 15 September entered Lae, only to find the Japanese gone.

The rapid seizure of Lae put MacArthur about a month ahead of the original CARTWHEEL schedule, which had set a mid-October target date for the Finschhafen operation. But before taking advantage of this stroke of good fortune, MacArthur ordered a comprehensive review of the Allied situation in New Guinea. The objective was control of Vitiaz and Dampier Straits, separating the Huon Peninsula and New Britain. The capture of Finschhafen was only one step toward this goal; Madang, the Japanese stronghold on the north shore of the peninsula, and Cape Gloucester in western New Britain would have to be taken also to gain control of these strategic straits. The problem, therefore, was how to exploit the gains at Lae and Salamaua to achieve the final objective more rapidly.

In a sense, it was the Japanese who answered this question by drawing the absolute national defense line from the Marianas through the Carolines to western New Guinea, thereby placing the Solomons, Rabaul, eastern New Guinea, and the Gilberts and Marshalls in the category of areas whose retention

Airborne operations at Nadzab

was not essential to Japanese victory.9 But this decision by Imperial General Headquarters did not mean that those areas forward of the line were to be abandoned. Rather, Japanese positions there were to be strengthened and held as long as possible, and commanders in the field were enjoined to exert their utmost efforts to delay the enemy’s drive toward the absolute defense line.

It was on the basis of these orders and the reinforcements sent by Imperial General Headquarters that the Japanese commanders in the Solomons and New Guinea made their plans for defense. An essential aspect of these plans, it will be remembered, was control of Dampier and Vitiaz Straits. To this end the Japanese strengthened the defenses of Bougainville in an effort to stem the Allied drive up the Solomons, and reinforced Rabaul and the Cape Gloucester garrison in western New Britain to hold the east side of the straits.

The key position on the New Guinea flank was Finschhafen, an airfield site and staging point for men and supplies. No one knew better than Lt. Gen. Hatazo Adachi, 28th Army commander in New Guinea, that the 1,000-man garrison at Finschhafen was inadequate, but, lacking the troops, there was nothing he could do to reinforce it. The Allied invasion of Lae changed the situation and led to a change in plans that freed the 20th Division from its current assignment. One element of the division Adachi ordered inland to Kaiapit, strategically

situated near the source of the Markham and Ramu Rivers, to prevent the Allies from advancing down the Ramu Valley to Madang. The main body of the division, then located at Bogadjim about 25 miles south of Madang, he ordered to Finschhafen, 200 miles away.

When the 20th Division left Bogadjim on 10 September, five days before the Australian occupation of Lae, Allied plans for the next advance had been laid. Estimating correctly that the Japanese would stubbornly resist the Allied drive along the Huon Peninsula, it was agreed that General Blarney’s New Guinea Force should advance simultaneously along the coast to Finschhafen and Saidor and inland to Kaiapit, then down the Ramu Valley to Dumpu, in conjunction with the invasion of western New Britain by General Krueger’s Alamo Force. The probable target date, it was then estimated, would be December 1943.

This plan and the target date was set at a conference in Port Moresby on 3 September, before the Lae invasion and before the 20th Division had begun its move toward Finschhafen. The absence of opposition at Lae combined with information on the enemy’s movements forced a rapid change in the timetable. Now the Allies much reach Finschhafen before the 20th Division. MacArthur waited only for the first troops to reach Lae. When they did, on 15 September, he ordered General Blarney to start the drive up the Markham Valley. Two days later, he issued his orders for the seizure of Finschhafen. The Madang operation was temporarily postponed in the hope that it might ultimately prove unnecessary.

The advance up the Markham Valley began almost immediately. On 19 September a company of Australian infantry, flown by transport planes to a point about eight miles from Kaiapit, seized that strategic village at the head of the valley. (Map I) There it was joined two days later by elements of the 7th Division from Nadzab. The drive down the Ramu Valley began soon after and by 6 October Dumpu was in Allied hands.

The landing at Finschhafen came on 22 September, and was made by a brigade of the gth Australian Division. After a week of hard fighting, the Australians captured the town and nearby airfield on 2 October. But the victory was, in a sense, a hollow one, for the bulk of the Japanese garrison, 4,000 men, had retreated to the 3,240-foot-high Satelberg, a peak that dominated Finschhafen and the surrounding area. There it was joined by the 20th Division and on 16 October, the Japanese launched a coordinated ground and seaborne counterattack. This effort failed, but the Japanese kept trying until the end of October. Thereafter they went on the defensive. The Australians had now received reinforcements and it was their turn to take the offensive. But a month of difficult fighting was still required to drive the Japanese off Satelberg.

The Australians did not stop once they had taken the peak. Their orders were to take Sio, about fifty miles up the coast, so they pushed on, driving the remnants of the 20th Division before them. On 1 January 1944, they reached their objective and seized the town, thereby bringing under Allied control a 60-mile-stretch of coast line extending from Finschhafen to Sio. Except for

Map 11: Southwest Pacific Operations, September 1943–February 1944

isolated centers of resistance, the New Guinea Force campaign in the Huon Gulf area was over.

The Gilbert Islands10

While MacArthur and Halsey were taking turns hitting the Japanese, Admiral Nimitz had moved into the Gilberts, thus launching the long delayed offensive westward across the vast ocean reaches of the Central Pacific.

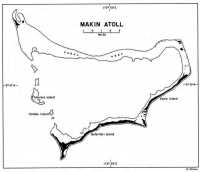

For this operation, Nimitz had the bulk of the Pacific Fleet, the Fleet Marine Force, the Army’s Seventh Air Force, and the combat and logistical elements of General Richardson’s command. All of these contributed to or directly participated in the Gilberts invasion.11 The role of the Army was to furnish the assault element for Makin, land-based aircraft for Admiral Hoover’s

Map 12: Makin Atoll

Defense and Shore-Based Air Force, logistical support, and part of the garrison force.

Preparations for the invasion of the Gilberts had begun in August 1943, when Nimitz received the directive for the operation from the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Since that time, the forces had been selected and trained, an organization established under Spruance for the conduct of this and succeeding amphibious operations, a joint staff provided for Nimitz, and the equipment and supplies needed for the assault and subsequent occupation of the islands assembled.

The task had not been easy. This was the first offensive effort in the Central Pacific Area and the transition from a defensive to an offensive role required many adjustments in organization and outlook. Preparations were complicated also by the problems of inter-service relations and the fact that the major assault units were not only from different services and accustomed to operate in different ways but also were scattered

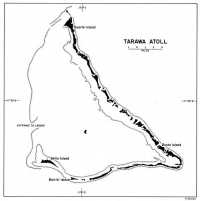

throughout the Central and South Pacific Areas. The 27th Division, scheduled to take Makin, was in Hawaii; the 2nd Marine Division, which was to seize Tarawa, was in New Zealand; and the three defense battalions were at Wallis, Samoa, and Pearl Harbor. To assemble, train, and rehearse these forces and bring them into position before the objective at the exact moment and in the right order was a complex and difficult task.

An additional factor that affected all preparations for the Gilberts invasion was that they had to be done concurrently with the planning for the Marshalls. There was simply not enough of everything to go around. Many of the vessels used for the first operation would have to be used again in the Marshalls two months later. But expendable supplies could not be reused, nor could the assault forces for the Gilberts be employed again in so short a time. Thus, two separate task forces, complete with all the equipment and supplies needed for amphibious warfare had to be assembled simultaneously. It was a job of the first magnitude for a headquarters that had not yet conducted a single amphibious attack.

One of the chief tactical problems of the Gilberts invasion as well as subsequent operations against coral atolls was to carry the assault troops and their supplies across the fringing reefs that encircled the objective and constituted a major hazard in the landing. To traverse this obstacle and to take the troops across the defended beaches, the assault forces had the shallow-draft amphibian tractors, officially designated LVT but more often called the amphtrac or Alligator. With the 2½-ton amphibian truck (the DUKW), used first in the Sicily and New Georgia campaigns, the LVT rates as one of the great contributions of World War II to the art of amphibious warfare. Both were truly amphibious weapons of the most modern design and played a vital role in making possible the efficiency and success that marked amphibious operations in the Pacific during World War II.

At an early stage in the planning for the Gilberts campaign it was realized that LVTs would be required both at Tarawa and Makin. (Maps 12 and 13) Especially at Tarawa, where the water over the fringing coral reefs was extremely shallow and the beach defenses especially strong, was there need for the amphibian tractor. Since most of the amphtracs the 2nd Marine Division had were of the early unarmored type, subject to mechanical failures and clearly inadequate for the job, the division requested 100 of the latest models, LVT(2). The request was granted but because of a shipping shortage, the division received only 50. This gave the Marines a total of about 125 of the vehicles, enough for the first three waves of the assault. The 27th Infantry Division, which would face less formidable obstacles at Makin, had 48 of the amphtracs, but received them only at the end of October, thirteen days before it embarked for the invasion.

The movement to the objective was itself a masterpiece of logistical planning. On 3i October, part of the garrison force left Oahu in six LSTs with destroyer escort; five days later three more LSTs carrying the amphibian tractors and special landing forces for the Makin invasion sailed for the Gilbert Islands. The first group, traveling more slowly and by a longer route, would reach its destination

Map 13: Tarawa Atoll

later than the second, which was scheduled to arrive at the same time as the main body of Admiral Turner’s Northern Attack Force. This last, consisting of the Makin assault troops and the expeditionary force, loaded in attack transports, and a carrier group under Rear Adm. Arthur W. Radford left Pearl Harbor on 10 November in the company of the Carrier Interceptor Group. The carriers sailed a course parallel to and 350 miles northwest of the landing force until they were 800 miles from the target. There the carriers struck out in different directions to their assigned stations and the landing force turned south

to meet Rear Adm. Harry W. Hill’s Southern Attack Force. On 18 November, Hill and Turner rendezvoused at a point about 600 miles southeast of Makin and traveled toward the objective along a parallel course.

The elements constituting the Southern Attack Force, scheduled for the Tarawa invasion, came from the South Pacific. From New Zealand the 2nd Marine Division went to Efate in the New Hebrides for rehearsal and from there sailed in attack transports for the Gilberts On 13 November. Next day it was joined by the Southern Carrier Group from Espiritu Santo, and a few clays later by a small force of light cruisers from Bougainville.12 Just south of Funafuti, the carriers parted company with Admiral Hill who headed for his rendezvous with Turner. The Relief Carrier Group under Admiral Sherman, which had supported Halsey in the Bougainville operation, fueled at Espiritu Santo and sailed north to Nauru, hit it on the 19th, then provided cover for the Makin and Tarawa garrisons en route to the objective. From Wallis Island, west of Samoa, came the garrison force for Apamama, and from Samoa came the LSTs carrying the fifty new amphtracs for the 2nd Marine Division.

Late on the night of 19 November, the two attack forces and the vast armada of warships, cargo vessels, transports, and other craft were in their assigned positions. During the early morning hours of the 20th, as the battleships and heavy cruisers moved into position for the opening bombardment and the carriers sent their planes off the flight decks to bomb and strafe the beaches, the transports took their assigned stations and prepared to debark the troops. The invasion of the Gilberts had begun; four months of planning and preparation were now to reach fruition.

The Japanese had offered comparatively little opposition to the approach of these various task forces from all parts of the Pacific. Some land-based planes had come out to strike at one of the LST groups, but without much effect. The Combined Fleet at Truk had not stirred. Twice before, once in September and again in October, when a fast carrier force under Rear Adm. Charles A. Pownall had struck the Gilberts and Wake, Admiral Koga had sallied forth to give battle. Both times he had failed to find Pownall’s elusive carriers and had returned to Truk empty-handed. Apparently convinced by the Bougainville landing that the Americans would not strike now in the Central Pacific, Koga had sent 173 of his carrier-based planes and a strong force of heavy cruisers to Rabaul at the beginning of November. The result was disastrous. Without his cruisers and the carrier planes, Koga dared not venture out of Truk. Helpless, he had to stand by idly as the huge American fleet converged on the Gilberts. The one chance he had sought for a showdown with the Pacific Fleet was lost.

Though the main striking force of the Combined Fleet was immobilized at this critical juncture, the Japanese were by no means defenseless. Despite the attacks of Admiral Pownall’s fast carrier force, Japanese aircraft in the Gilberts–Marshalls area were still capable of inflicting damage. And at Truk were submarines that could strike heavy blows if they could get within reach of the Allied

LVTs at Tarawa

invasion force. These Koga sent out as soon as he heard of the landing and one of them sank the escort carrier Liscome Bay on 24 November. Koga also sent ground and air reinforcements to Tarawa, but they got only as far as the southern Marshalls. By that time Tarawa had fallen and the troops were used to bolster the defenses of Kwajalein instead.

The defense plans of the local garrisons at Makin and Tarawa were little affected by events at Rabaul and Truk. Makin had the smaller force, about 700 men, and most of these were labor and service troops. Effective combat strength was probably no more than 300. Light defenses had been constructed along the lagoon side, and across the island were two tank barrier systems surrounded by ditches, pill boxes, and wire entanglements. Gun emplacements and rifle pits, so placed as to provide mutual support and interlocking fields of fire, guarded the approaches to these barriers and offered additional protection against assault from the ocean side of the island. These were not formidable defenses, nor was the defending force large, but so narrow and restricted was the area of operations that the greatly outnumbered Japanese fully expected to give a good account of themselves.

On Tarawa, the defenders were not only more numerous but enjoyed also the advantage of strong fortifications. The total force numbered about 4,800 men, more than half of them effective combat troops. The island itself had been converted into a fortress, ringed with beach defenses whose 13-mm. and 7.7-mm. machine guns were carefully

positioned to drive off the invaders. On the fringing reef were log and concrete obstacles to channelize approaching boats. In the water and on the beaches were additional obstacles and double-apron low-wire fences along which the defenders could lay down a barrage of antiboat fire calculated to halt the invaders before they could step ashore. Inland from the beaches were bombproof shelters of concrete and coconut logs for weapons and men alike, connected by a system of ditches and tunnels. A large array of guns ranging in size from 8-inch to 13-mm., and seven tanks fringed the armament of the Japanese defenders. Of all the beaches assaulted in World War II, only Iwo Jima was more strongly fortified or more stubbornly defended than Tarawa.

The capture of Makin took three days and cost more in naval casualties than in ground troops. Despite its great superiority in men and weapons, the 27th Division had considerable difficulty overcoming the 700 defenders. Combat casualties numbered 218 (66 killed and 152 wounded), as compared to an estimated 395 Japanese killed in action, a ratio of 6 to 1. When the American losses incurred in the sinking of the Liscome Bay are added to this total, however, the balance is on the other side. With the 642 men that went down with the carrier, American casualties exceeded the strength of the entire Japanese garrison on Makin.

If Makin had been, as one naval historian wrote, “a pushover for the ground troops,”13 Tarawa was a grim and deadly struggle, probably the toughest fight thus far in Marine Corps history. In the same length of time it took the 27th Division to capture Makin, the 2nd Marine Division stormed the heavily fortified beaches of Tarawa, reduced its cement and steel emplacements one by one, and killed virtually every Japanese soldier on the island. The cost was terrific—3,301 casualties, of whom over 1,000 were killed in action or died later of wounds.

Was the island worth the price? General Holland Smith, Marine commander of the expeditionary force, thought not. Tarawa, he declared later, had “no particular strategic importance” and should have been bypassed and neutralized from bases to the east and south. Its capture, he charged, was “a terrible waste of life and effort.”14 Few of General Smith’s colleagues agreed with this judgment. Strategically and tactically, they held, the campaign in the Gilberts proved of great value. Without advance bases in the Gilberts, operations against the Marshalls would have been enormously difficult and infinitely more complicated and hazardous. Moreover, the lessons learned at Tarawa—one officer compiled a list of one hundred mistakes made during the operation—were of inestimable value in subsequent assaults. The most important of these was the conclusive proof it offered, as Admiral Hill wrote, that naval task forces “had the power to move into an area, obtain complete naval air control of that area, and remain there with acceptable losses throughout the entire assault and preliminary consolidation phases.”15 Had this fact not been demonstrated—and up to this time it had not been—the entire Central Pacific

Landing Craft moving in on Butaritari Island. Note LSTs standing offshore at top, and reef side of island at bottom

offensive might well have ended before it began.

CARTWHEEL Completed

General MacArthur and Admiral Halsey, meanwhile, had been pushing forward in New Guinea and the Solomons. Having taken Lae and Finschhafen, and begun his drive up the Markham Valley, MacArthur had still to gain control of the Vitiaz and Dampier Straits before he could breach the Bismarcks barrier. On his part, Halsey was to move into the northern Solomons from where he would be in position to unite with MacArthur in the final phase of CARTWHEEL.

Before the New Georgia fighting was over, South Pacific aircraft had begun an intensified campaign to neutralize Japanese airfields in southern Bougainville and in the Shortlands while ground and naval forces prepared for the invasion to follow.16 By 1 November, D-day for the landing, all fields in the Bougainville area had been rendered inoperational.

The neutralization of Japanese air power in the northern Solomons coincided with the arrival of strong air reinforcements at Rabaul, just at the moment when the Bougainville invasion was getting under way. To the 200 aircraft based at Rabaul were added, at the beginning of November, 173 carrier planes from the Combined Fleet at Truk. This move was part of a Japanese plan known as Operation RO, which had as its purpose the delay of the Allied drive toward the “absolute national defense line.” Originator of the plan was Admiral Koga, Yamamoto’s successor, who hoped that by concentrating all available naval, land, and carrier air forces at Rabaul lie could cut the Allied line of communications and thus retain control of the straits between New Guinea and New Britain. It was admittedly a risky scheme, for without their aircraft the carriers were useless and without the carriers the Combined Fleet was helpless to stop the U.S. Pacific Fleet. But Koga, having satisfied himself that Nimitz did not intend to move into the Marshalls, took the risk. He had failed in his attempt to catch the U.S. Fleet in the Wake area and now was determined to catch it in the northern Solomons. It was a bad gamble and Koga lost not only his planes but also his chance to stop the Central Pacific offensive in its tracks. Here, at the very outset, was demonstrated in striking fashion the advantages of the twin drive through the South–Southwest Pacific and Central Pacific Areas.

The Bougainville campaign had begun on 27 October with the seizure of the Treasury Islands by New Zealand and American troops.17 That same day marines landed on Choiseul to the southwest in a feint toward the east coast of Bougainville. The real invasion, when it came on i November, was actually made on the west coast, midway up the island, at Empress Augusta Bay, and it caught the Japanese by surprise. Despite

local opposition from a small well dug-in garrison at Cape Torokina, between the two southernmost landing beaches, the 3rd Marine Division made good its landing and by the end of D-day held a narrow beachhead 4,000 yards in length along the shore of Empress Augusta Bay.

Japanese air and naval reaction to the Allied invasion of Bougainville was prompt and violent. On i November, after a vain effort to send in ground reinforcements to destroy the American force in Empress Augusta Bay, a naval task force (2 heavy and 2 light cruisers accompanied by 6 destroyers) under Vice Adm. Sentaro Omori was sent down from Rabaul. It was intercepted by Rear Adm. Aaron S. Merrill’s Task Force 39 off Cape Torokina and turned back after a battle that lasted most of the night.18 A strong attempt by the Japanese next morning, 2 November, to knock out Merrill’s cruisers from the air and thus isolate the beachhead was foiled by planes from New Georgia. Further attempts were discouraged by General Kenney’s aircraft from the Southwest Pacific, whose raids against Rabaul kept the Japanese busy defending their own base. Here again the coordinated action of adjacent Allied theaters paid large dividends.

Meanwhile, Admiral Koga had assembled at Truk a formidable force of 7 heavy cruisers, 1 light cruiser, 4 destroyers, and about a half dozen auxiliary vessels. These he sent south under Vice Adm. Takeo Kurita to Rabaul, where they arrived safely in the early morning of 5 November. The threat presented by this force was a serious one. With Merrill’s cruisers temporarily out of action after four engagements in two days, Halsey did not have a single heavy cruiser to send against Kurita. This was, he later wrote, “the most desperate emergency that confronted me in my entire term as COMSOPAC.”19 But south of Guadalcanal, refueling after 1-2 November strikes in the northern Solomons, was Rear Adm. Frederick C. Sherman’s fast carrier force (Saratoga and Princeton), lent by Nimitz for the invasion. Another carrier force had been promised by Nimitz, who was himself in the midst of last-minute preparations for the Gilberts, but it would not arrive until the 7th.

Though reluctant to use the fast carriers against a strong base like Rabaul and fearful of the damage or loss he might incur in such a mission, Admiral Halsey could see no other way of meeting the threat posed by Kurita’s force. Having made up his mind, he acted with characteristic dispatch. Sherman was to proceed immediately toward Rabaul, and, on the morning of the 5th, launch an all-out attack on Kurita’s ships from a point about 230 miles to the southeast. Aircraft from New Georgia would provide cover during the approach and retirement, and MacArthur’s aircraft would follow up with an attack on Rabaul that afternoon.

Halsey’s boldness paid off handsomely. The weather was perfect and the plan was carried out without a hitch. At the cost of ten planes and fifteen men, Sherman inflicted such heavy damage on the

enemy fleet that Koga pulled it back to Truk late on the afternoon of the 5th. Kenney’s follow-up with 27 B-24’s and 58 P-38’s met little opposition, for the Japanese were out looking for Sherman and the Southwest Pacific aircraft were able to bomb installations and docks at Rabaul without serious opposition.

Japanese air power at Rabaul fared no better than the surface forces but accomplished a good deal more destruction. Ever since the landing at Torokina, Japanese aircraft had hammered away at targets in the Bougainville area and had fought an incessant battle with Allied aircraft from New Georgia. In a sense, this was the real battle of Bougainville, for had the Japanese won control of the air they could have cut off the beachhead area and brought in sufficient troops to drive out the marines. Thus, the Allied command exerted every effort to maintain local air superiority and to keep open the line of communication. South Pacific aircraft flew countless missions over Bougainville and struck repeatedly at the enemy’s air bases. In one day, there were more than 700 takeoffs and landings at the Munda field alone. The contribution of General Kenney’s air force was to bomb the fields at Rabaul, which he did at every opportunity.

The arrival of the additional carrier group (Essex, Bunker Hill, and Independence) from the Central Pacific on 7 November offered Halsey a golden opportunity.20 Encouraged by Sherman’s success, he sent both carrier groups to Rabaul on a double strike. Sherman delivered his attack on the morning of the t i th, damaged some ships, and escaped without detection. The second force, led by Rear Adm. Alfred L. Montgomery, launched its strike simultaneously, but had to fight its way out. It would have been better for the Japanese, perhaps, had they not found Montgomery, for they lost thirty-five planes in a vain effort to hit the carriers.

If Admiral Koga had needed any further proof that Operation RO was a failure, the events of 11 November must have convinced him. The next day he ordered the remaining 120 carrier planes back to Truk before they should all be lost. Thus, on the eve of the Gilberts invasion, the one force that the Allies feared most, the Combined Fleet, was helpless to interfere. It would be months before the carrier losses could be replaced and the cruisers damaged at Rabaul put in action again. The failure of the RO operation also marked the end of Rabaul’s importance as the base for Japanese operations against any Allied advance in the Solomons and New Guinea. With land-based aircraft at close striking range, the Allies were able to neutralize the once great Japanese bastion and bypass it without danger. For the Japanese, the large garrison and formidable defenses at Rabaul ultimately proved a liability, rather than an asset.

Air and naval victory assured the success of the Bougainville invasion and greatly eased the task of the ground forces. Reinforcements and supplies began to come in on 8 November and before the end of the month the Army’s 37th Division was sharing the beachhead with the 3rd Marine Division. Air raids were still frequent, and the Japanese had

Admiral Halsey, Maj. Gen. Robert S. Beightler, and Maj. Gen. Roy S. Geiger (seated, left to right) discuss a map problem at the 37th Division command post on Bougainville

succeeded in putting ashore first a regiment and then other troops that made the going hard for the Americans. By 15 December, when General Griswold’s XIV Corps took over from I Marine Amphibious Corps, there were 44,000 men within a defended semicircular perimeter about 23,000 yards in length. As in New Georgia, Halsey made General Harmon his deputy for ground operations on Bougainville, and by the end of the month the Americal Division had begun to replace the 3rd Marine Division. Bougainville was now virtually an Army show.

The blow that finally broke the Japanese hold on the Vitiaz-Dampier bottleneck and gave the Allies clear passage through the Bismarck barrier was delivered by MacArthur’s forces at the turn of the year.21 It was a one-two punch, a right at Cape Gloucester in western New Britain to gain control of Dampier Strait and a left at Saidor on the north shore of the Huon Peninsula. Both operations had been on the books for some time, but the New Britain plan was the older one and dated from the days when Rabaul was the great objective. The Saidor plan was of more recent vintage,

General Griswold and General Harmon (center) being briefed on the tactical situation by 3rd Marine Division officers.

having been proposed in September by General Chamberlin, and was related to the Australian drive up the New Guinea coast from Finschhafen to Sio. The Cape Gloucester operation looked east, the Saidor west and north, but both formed part of the single plan to breach the Bismarcks barrier and both were conducted by General Krueger’s ALAMO Force.

Planning for New Britain had begun in August but it was not until 22 September that MacArthur issued the directive for the operation to General Krueger. Under this directive, General Krueger’s ALAMO Force (U.S. Sixth Army) was required to conduct extensive airborne and amphibious operations designed to gain control of two large offshore islands (Rooke and Long) and virtually half of New Britain. D-day was optimistically set for 20 November, and General Krueger was directed at the same time to prepare for the capture of Rabaul in cooperation with South Pacific forces.

The extensive operations envisaged in this plan, combined with the rapid progress of the advance in New Guinea and the fact that the Joint Chiefs of Staff had already decided to bypass Rabaul, produced a thorough review of the New Britain project. General Kenney thought the operation entirely unnecessary, and told MacArthur that a field at Cape Gloucester would not provide any more air support than could be provided with the bases already in Allied hands. An airfield at Saidor, he conceded,

Supply road on Bougainville built by Army engineers. Note how coconut logs are used to support steep bank and underside of road.

might be necessary.22 General Chamberlin, MacArthur’s G-3, did not dispute this point, but observed that possession of western New Britain would strengthen the Allied position in the area and facilitate operations in New Ireland and the Admiralties. Admirals Carpender and Barbey also favored control of both sides of the Vitiaz–Dampier barrier; it was the seizure of Gasmata on the southwest shore of New Britain that bothered them. That operation, they felt, would take their ships too close to Japanese bases at Rabaul.

The result of this review was a revised plan, issued on 10 November, which called only for the occupation of Cape Gloucester, the adjacent islands, and “minimum portions” of western New Britain. But now the naval commanders were dissatisfied. They apparently wanted a PT base on the south shore and none was provided for in the plan. Obligingly, MacArthur authorized the seizure of Arawe, believed to be weakly defended, as an additional objective on General Kenney’s assurance that air support could be provided.23

Fixing a target date for the invasion proved no easy matter and was complicated

by airfield construction schedules, tide, weather, and the phases of the moon. The first date selected, 20 November, was quickly discarded, and on Chamberlin’s recommendation 4 December was chosen. Krueger objected and asked for either more time or more ships. Since the ships were not available, he got more time, and the dates finally selected were 15 December for Arawe and 26 December for Cape Gloucester. The same ships that were used for Arawe would carry the invasion force to Cape Gloucester.

The assault units for the New Britain operation were American and were assigned to ALAMO Force. (The New Guinea Force, it will be remembered, was composed almost entirely of Australian units.) Arawe was to be taken by a force built around the 112th Cavalry Regiment and the 148th Field Artillery Battalion under Brig. Gen. Julian W. Cunningham. The assault force for the Cape Gloucester landing was a much stronger one, consisting of the 1st Marine Division, veteran of the Guadalcanal Campaign, the 12th Marine Defense Battalion, the Army’s 2nd Engineer Special Brigade, and miscellaneous service and supporting units. In ALAMO Force reserve was the 32nd Division, which had fought at Buna.

Planning for the Saidor operation was less complicated, partly because the problems presented were simpler and partly because the operation was decided upon at the last moment. The advantages of an Allied base at Saidor derived from its location. Not only would it give MacArthur control of Vitiaz Strait and virtually the entire north shore of the Huon Peninsula, but it would also provide a base for further advances along the New Guinea coast. Bogadjim was only about fifty miles away; Madang another twenty. Moreover, the bulk of Adachi’s /8th Army was divided between Madang and Sio, toward which the Australians were already driving. The capture of Saidor would place Allied forces between the two main Japanese concentrations.

Though an outline plan for the Saidor invasion was ready by 11 December, it was not until the 17th, two days after the Arawe landing, that MacArthur ordered Krueger to proceed with the operation, in cooperation with Australian operations in the Ramu Valley and against Sio. The assault force was to come from the 32nd Division, ALAMO Force reserve for western New Britain. D-day was tentatively set for 2 January 1944, with the understanding that the exact date of the landing would depend upon the situation at Cape Gloucester. This proviso was necessary because there were not enough landing craft in the theater for both operations and Krueger would have to use the same vessels for both landings.

General Krueger, a cautious and conservative commander, was apprehensive about the Saidor landing. The schedule was admittedly a tight one. Moreover, the ALAMO Force would be involved in three separate operations simultaneously at a time when New Guinea Force was engaged on two separate fronts. There was little margin for error or for the unexpected, and the job of keeping these forces supplied would be difficult. For these reasons, Krueger urged postponement of the Saidor operation, but to no avail. The Allied advance had gained a momentum MacArthur was unwilling to lose. He therefore ordered Krueger to proceed as planned with the assurance that supplies would be forthcoming. On

30 December, the target date 2 January was confirmed.24

By the time all arrangements for the Saidor invasion had been completed, ALAMO Force had established itself firmly in western New Britain. At Arawe, the 112th Cavalry had landed on 15 December and secured a beachhead. Opposition was light initially, but the Japanese quickly ordered reinforcements to Arawe and by the end of the year the Americans faced the prospect of an arduous fight to clear the area. Two weeks were required for that job, but it was not until mid-February that the Japanese finally withdrew. Once won, the area proved of little value to the Allies and no PT base was ever built there.

At Cape Gloucester the Japanese offered little resistance to the assault forces when they came ashore on 26 December. Only when the Marine troops reached the airdrome area west of the landing beaches did they meet any opposition, and that was quickly overcome. Driving rain, jungle undergrowth, and swamp presented more difficulties than did the enemy. The most serious fighting came after the capture of the airfield on 30 December, but by the middle of January it was over and the marines spent the rest of their time in the Cape Gloucester area in mopping up. How heavy had been the fighting is indicated by the casualties in the 1st Marine Division and attached units: 328 killed and 844 wounded in action. By the end of February the Japanese had

withdrawn to Rabaul and left the Americans in complete possession. Ultimately two strips were built, but they were no longer needed. Like Arawe, Cape Gloucester had little strategic significance, for its conquest came at a time when the war was moving rapidly past the Bismarck barrier. Yet both operations did serve the purpose of providing additional security on the right flank of the drive up the New Guinea coast.

The Saidor invasion force spent New Year’s Eve and the first day of the year aboard landing craft. On the 2nd, the troops were put ashore with an efficiency and dispatch that bore witness to the value of training arid experience over the past few months. There was virtually no opposition and the only untoward incident came early the next morning when the Americans fired on their own ships in the dim light of dawn. Fortunately there was no damage. The few Japanese in the vicinity of Saidor were quickly disposed of, after which engineers and service troops moved in to clear the way for the construction of an airfield, roads, docks, and other installations. On to February, when the Australians at Sio had advanced up the coast to make contact with the Saidor Force, General Krueger announced that the campaign was over. It took a month more for the Australians in the Ramu Valley to complete their drive and on 21 March, elements of the 7th Australian and 32nd U.S. divisions finally met. On 13 April, Bogadjim fell and all of the Huon Peninsula with the Markham and Ramu Valleys lay in Allied hands.

The end of Japanese resistance at Bogadjim marked the completion of CARTWHEEL. In a period of ten months, two more than MacArthur had originally

estimated it would take, forces of the South and Southwest Pacific had advanced up the coast of New Guinea and through the Solomons in successive stages in a series of mutually supporting and coordinated operations and now stood in position to breach the Bismarck barrier. Despite the unique command arrangements by which MacArthur exercised strategic control and Halsey the command of South Pacific forces, cooperation between the two theaters had been excellent. Not once had there been any disagreement that had not been settled quickly with good will on both sides, or any failure to coordinate operations in the two theaters and to provide support when it was needed.

The original design of CARTWHEEL had been to place the forces of the South and Southwest Pacific in position to converge on Rabaul. But that objective had been changed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff while operations were in progress. Rabaul was not to be captured but neutralized. Thus, as the forces of the South and Southwest Pacific came within fighter range of Rabaul, they initiated an intensive air campaign against the Japanese base and by February 1944 had rendered it virtually impotent. Thereafter, as MacArthur resumed his advance through the Bismarck Archipelago and thence westward along the New Guinea coast toward the Philippines, Allied aircraft kept a careful watch on Rabaul. Though never reduced, the Japanese garrison there maintained a precarious existence until the war’s end brought relief.