Chapter IV: Prewar Plans, Japanese and American

By the summer of 1941, as the United States was beginning to strengthen the Philippines, Japan had reached “the crossroads of her fate.”1 The economic sanctions imposed by America, Great Britain, and the Netherlands had cut her off from the strategic materials necessary to support he war in China and threatened eventually to so weaken the Japanese economy as to leave Japan defenseless in a struggle with a major power. The leaders of Japan were faced with a difficult choice. They could either reach agreement with the United States by surrendering their ambitions in China and southeast Asia, or they could seize Dutch and British possessions by force.

The second course, while it would give Japan the natural resources so sorely needed, almost certainly meant war with Great Britain and the Netherlands. In the view of the Japanese planners, the United States would also oppose such a course by war, even if American territory was not immediately attacked. Such a war seemed less dangerous to Japan in the fall of 1941 than ever before and, if their calculations proved correct, the Japanese had an excellent chance of success. The British Empire was apparently doomed and the menace of Russian action had been diminished by the German invasion of that country and by the Japanese-Soviet neutrality pact.

The major obstacles to Japan’s expansion in southeast Asia was the United States. But Japanese strategists were confident they could deprive the United States of its western Pacific base in the Philippines and neutralize a large part of its Pacific Fleet at the start of the war. In this way they hoped to overcome America’s potential superiority and seize the southern area rapidly.

The Japanese Plan

Japanese strategy for a war with the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands was apparently developed in about six months by Imperial General Headquarters.2 Although this strategy was never

embodied on one document, it can be reconstructed from separate Army and Navy plans completed by the beginning of November 1941. Thereafter it was modified only in minor respects.3

Strategic Concepts

The immediate objective of Japanese strategy was the capture of the rich Dutch and British possessions in southeast Asia, especially Malaya and the Netherlands Indies. (Map 1) To secure these areas the Japanese believed it necessary to destroy or neutralize the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, deprive the United States of its base in the Philippines, and cut America’s line of communications across the Pacific by the seizure of Wake and Guam. Once the coveted area to the south had been secured, Japan would occupy strategic positions in Asia and in the Pacific and fortify them immediately with all the forces available, chief reliance being placed on mobile naval and air forces. These positions were to form a powerful defensive perimeter around the newly acquired southern area, the home islands, and the vital shipping lanes connecting Japan with its sources of supply.

The area marked for conquest formed a vast triangle, whose east arm stretched from the Kuril Islands on the north, through Wake, to the Marshall Islands. The base of the triangle was formed by a line connecting the Marshall Islands, the Bismarck Archipelago, Java, and Sumatra. The western arm extended from Malaya and southern Burma through Indochina, and thence along the China coast. The acquisition of the island-studded area would give to Japan control of the resources of southeast Asia and satisfy the national objectives in going to war. Perhaps later, if all went well, the area of conquest could be extended. But there is no evidence that it was the intention of the Japanese Government or of the Army and Navy to defeat the United States, and so far as is known no plan was ever drawn up for that purpose. Japan apparently planned to fight a war of limited objectives and, having gained what it wanted, expected to negotiate for a favorable peace.

Operations to secure these objectives and others would begin on the first day of war when Japanese military and naval forces would go into action simultaneously on many fronts. Navy carrier-based aircraft would attack Pearl Harbor. Immediately after, joint Army and Navy air forces would strike American air and naval forces in the Philippines, while other Japanese forces hit British Malaya. After these simultaneous attacks, advance Army units were to be landed at various point in Malaya and the Philippines to secure air bases and favorable

Map 1: Japanese Plan and Disposition of the Armies

positions for further advances. The results thus obtained were to be immediately exploited by large-scale landings in the Philippines and in Malaya and the rapid occupation of those areas. At the same time Thailand was to be “stabilized,” Hong Kong seized, and Wake and Guam occupied. The conquest of the Bismarck Archipelago would follow the seizure of the last two islands.

The occupation of Java and Sumatra was to begin after this initial period. While Java was being attacked from the air, Singapore was to be taken under fire from the land side by Japanese forces moving down the Malay Peninsula. Once that fortress was reduced these forces were to move on to northern Sumatra. Meanwhile, other Japanese forces moving southward through the Netherlands Indies were to join those in Sumatra in the final attack on Java.

Japanese planners anticipated that certain events might require an alteration of these plans and accordingly outlined alternative courses of action. The first possibility was that the Japanese-American negotiations then in progress would prove successful and make war unnecessary. If this unexpected success was achieved all operations were to be suspended, even if the final order to attack had been issued.4 The second possibility was that the United States might take action before the attack on Pearl Harbor by sending elements of the Pacific Fleet to the Far East. In that event, the Combined Fleet would be deployed to intercept American naval forces. The attacks against the Philippines and Malaya were to proceed according to schedule.

If the Americans or British launched local attacks, Japanese ground forces were to meet these while air forces were brought into the area to destroy the enemy. These local operations were not to interrupt the execution of the grand plan. But if the United States or Great Britain seized the initiative by opening operations first, Japanese forces were to await orders from Imperial General Headquarters before beginning their assigned operations.

The possibility of a Soviet attack or of a joint United States-Soviet invasion from the north was also considered by the Japanese planners. If such an attack materialized, operations against the Philippines and Malaya would be carried out as planned while air units would be immediately transferred from the home islands or China to destroy Russian air forces in the Far East. Ground forces were to be deployed to Manchuria at the same time to meet Soviet forces on the ground.

The forces required to execute this ambitious plan were very carefully calculated by Imperial General Headquarters. At the beginning of December 1941 the total strength of the Army was 51 divisions, a cavalry group, 59 brigade-size units, and an air force of 51 air squadrons. In addition, there were ten depot divisions in Japan.5 These forces were organized into area commands widely scattered throughout the Far East. (See Table 5.) The largest number of divisions was immobilized in China and large garrisons were maintained

Table 5—Organization and Disposition of Japanese Army, 1 December 1941

| Area | Headquarters | Divisions | Brigades a | Air Squadrons |

| Homeland | Imperial GHQ General Defense Command b Eastern District Army Central District Army Western District Army Northern District Army 1st Air Group | 52 Division Imperial Guard, 2nd, 3rd, 51st, 57th Depot Divisions 53, 54th Divisions 4th, 5th, 55th Depot Divisions 6th, 56th Depot Divisions 7th Divisions | 4 3 3 1 | 9 |

| Manchuria | Kwantung Army 3rd Army 4th Army 5th Army 6th Army 20th Army Defense Command Air Corps (Directly attached units) 2nd Air Group | 10th, 28th, 29th Divisions 9th, 12th Divisions 1st, 14th, 57th Divisions 11th, 24th Divisions 23rd Division 8th, 25th Divisions | 1 4 5 4 1 4 5 | 21 35 |

| China | China Expeditionary Army North China Area Army 1st Army 12th Army Mongolia Garrison Army 11th Army 23rd Army 1st Air Brigade | 27th, 35th, 110th Divisions 36th, 37th, 41st Divisions 17th, 32nd Divisions 26th Division, Cavalry Group 3rd, 6th, 13th, 34th, 39th, 40th Divisions 38th, 51st, 104th Divisions 4th Division (at Shanghai under direct command of Imperial GHQ | 5 3 3 1 2 5 1 | 16 |

| Korea | Korea Army | 19th, 20th Divisions | ||

| Formosa | Formosa Army | |||

| For the South | Southern Army c 14th Army 15th Army 16th Army 25th Army 3rd Air Group 5th Air Group 21 Ind Air Unit South Seas Detachment (at Bonins under direct command of Imperial GHQ) | 21st Division 16th, 48th Divisions 33rd, 55th Divisions 2nd Division Imperial Guard, 5th, 18th, 56th Divisions | 1 1 1 1 | 48 20 2 |

| Total | 51 | 59 | 151 |

a Brigades include all brigade size units, i.e., garrison forces in China and Manchuria, South Seas Det., etc.

b Command of the General Defense Command over each district army and the 1st Air Army in the Homeland was limited to only the matters pertaining to defense of the Homeland.

c Although the 21st, 33rd and 56th Divisions were assigned to the Southern Army, they were still in North China, Central China and Kyushu, respectively, on 1 December 1941. Their departures from the above areas were 20 January 1942, 13 December 1941 and 16 February 1942, respectively. 56th Division was placed under the command of 25th Army on 27 November 1941.

Source: Compiled by the Reports and Statistical Division of the Demobilization Bureau, 14 January 1952.

in Manchuria, Korea, Formosa, Indochina, and the home islands. Only a small fractions of Japan’s strength, therefore, was available for operations in southeast Asia and the Pacific.

In the execution of this complicated and intricate plan, the Japanese planners realized, success would depend on careful timing and on the closest cooperation between Army and Navy forces. no provision was made for unified command of the services. Instead, separate agreements were made between Army and fleet commanders for each operation. These agreements provided simply for cooperation at the time of landing and for the distribution of forces.

The Plan for the Philippines

The Japanese plan for the occupation of the Philippines was but part of the larger plan for the Greater East Asia War in which the Southern Army was to seize Malaya and the Netherlands Indies while the Combined Fleet neutralized the U.S. Pacific Fleet. The Southern Army was organized on 6 November 1941, with Gen. Count Hisaichi Terauchi, who had been War Minister in 1936, as commander. His orders from Imperial General Headquarters were to prepare for operations in the event that negotiations with the United States failed. Under his command were placed the 14th, 15th, 16th and 25th Armies, comprising ten divisions and three mixed brigades. Southern Army’s mission in case of war would be to seize American, British, and Dutch possessions in the “southern area” in the shortest time possible. Operations against the Philippines and British Malaya were to begin simultaneously, on orders from Imperial General Headquarters.6

Southern Army immediately began to prepare plans for seizure of the southern area. To 14th Army, consisting of the 16th and 48th Divisions and the 65th Brigade, was assigned the task of taking the Philippine Islands. The campaign in the East Indies was to be under the control of 16th Army; the 15th Army would take Thailand. The 25th Army was assigned the most important and difficult mission, the conquest of Malaya and Singapore, and was accordingly given four of the Southern Army’s ten divisions. Air support for these operations was to be provided by two air groups and an independent air unit. The 5th Air Group was assigned to the Philippine campaign.7

Beginning on 10 November a number of meetings attended by the senior army and navy commanders were held in Tokyo to settle various details in the execution of the plans. The commanders of the 14th, 16th, and 25th Armies, in session with the Premier (who was also the War Minister), the Army Chief of Staff, and General Terauchi, were shown the Imperial General Headquarters operational plans, given an outline of the strategy, and told what their missions would be in the event of war. In the discussions between Army and Navy commanders that followed this meeting a few modifications were made in the general strategy and specific operational plans

were put into final form.8 On the 20th Southern Army published its orders for the forthcoming operations, omitting only the date when hostilities would start.

Specific plans for the seizure of the Philippine Islands were first developed by the Japanese Army’s General Staff in the fall of 1941. As the plans for the southern area were developed, the Philippine plan was modified to conform to the larger strategy being developed and to release some of the forces originally assigned 14th Army to other, more critical operations. The final plan was completed at the meetings between the 14th Army commander, Lt. Gen. Masaharu Homma, and the commanders of the 5th Air Group (Lt. Gen. Hideyoshi Obata), the 3rd Fleet (Vice Adm. Nishizo Tsukahara), held at Iwakuni in southern Honshu from the 13th to the 15th of November.

The general scheme of operations for the Philippine campaign called for simultaneous air attacks starting on X Day, the first day of war, against American aircraft and installations in the Philippines by the 5th Air Group (Army) and the 11th Air Fleet (Navy). While the air attacks were in progress, advance Army and Navy units were to land on Batan Island, north of Luzon; at three places on Luzon: Aparri, Vigan, and Legaspi; and at Davao in Mindanao. The purpose of these landings was to seize airfields. The air force was to move to these fields as soon as possible and continue the destruction of the American air and naval forces from these close-in bases.

When the major part of American air strength had been eliminated, the main force of the 14th Army was to land along Lingayen Gulf, north of Manila, while another force would land at Lamon Bay, southeast of the capital. These forces, with close air support, were to advance on Manila from the north and south. It was expected that the decisive engagement of the campaign would be fought around Manila. Once the capital was taken, the islands defending the entrance to Manila Bay were to be captured and Luzon occupied.

Imperial General Headquarters and Southern Army expected General Homma to complete his mission in about fifty days; at the end of that time, approximately half of the 14th Army, as well as the Army and Navy air units, were to leave the Philippines for operations in the south.9 The remaining elements of the 14th Army were then to occupy the Visayas and Mindanao as rapidly as possible. Little difficulty was expected in this phase of the operations and detailed plans were to be made at the appropriate time. The Japanese considered it essential to the success of Southern Army operations to gain complete victory in the Philippines before the end of March 1942. Forces assigned to the Philippine campaign, small as they were, were required in other more vital areas.

The Japanese plan was based on a detailed knowledge of the Philippine Islands and a fairly accurate estimate of American and Philippine forces.10 The Japanese were aware that the bulk of the American and

Philippine forces was on Luzon and that the U.S. Army garrison had been increased since July 1941 from 12,000 to 22,000. Eighty percent of the officers and 40 percent of the enlisted men were thought to be Americans and the rest, Filipinos. American troops were regarded as good soldiers, but inclined to deteriorate physically and mentally in a tropical climate. The Filipino, though inured to the tropics, had little endurance or sense of responsibility, the Japanese believed, and was markedly inferior to the American as a soldier. The American garrison was correctly supposed to be organized into one division, an air units, and a “fortress unit” (Harbor Defenses of Manila and Subic Bays). The division was mistakenly thought to consist of two infantry brigades, a field artillery brigade, and supporting services. The Japanese knew that MacArthur also had one battalion of fifty-four tanks—which was true at that time—and believed that there was also an antitank battalion in the Islands. The harbor defenses were known to consist of four coast artillery regiments, including one antiaircraft regiment.

The Japanese estimated that the American air force in the Philippines was composed of one pursuit regiment of 108 planes, one bombardment regiment of about 38 planes, one pursuit squadron of 27 planes, and two reconnaissance squadrons of 13 planes. American aircraft were based on two major fields on Luzon, the Japanese believed. They placed the pursuit group at Nichols Field, in the suburbs of Manila, and the bombers at Clark Field. Other fields on Luzon were thought to base a total of 20 planes. The Japanese placed 52 navy patrol and carrier-based fighter planes at Cavite and 18 PBYs at Olangapo.

The strength of the Philippine Army and the Constabulary, the Japanese estimated, was 110,000 men. This strength, they thought would be increased to 125,000 by December. The bulk of the Philippine Army, organized into ten divisions, was known to consist mostly of infantry with only a few engineer and artillery units. This army was considered very much inferior to the U.S. Regular Army in equipment, training, and fighting qualities.

Though they had a good picture of the defending force, Japanese knowledge of American defense plans was faulty. They expected that the Philippine garrison would make its last stand around Manila and when defeated there would scatter and be easily mopped up. No preparation was made for an American withdrawal to the Bataan peninsula. In October, at a meeting of the 14th Army staff officers in Tokyo, Homma’s chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Masami Maeda, had raised the possibility of a withdrawal to Bataan. Despite his protests, the subject was quickly dropped.11 Staff officers of the

48th Division also claimed to have discussed the question of Bataan before the division embarked at Formosa. The consensus then was that while resistance could be expected before Manila and on Corregidor, Bataan “being a simple, outlying position, would fall quickly.”12

The Japanese originally planned to assign to the Philippine campaign six battalions for the advance landings, two full divisions for the main landings, and supporting troops. So meager were the forces available to Southern Army that General Homma was finally allotted for the entire operations only 2 divisions, the 16th and 48th. Supporting troops included 2 tank regiments, 2 regiments an 1 battalion of medium artillery, 3 engineer regiments, 5 antiaircraft battalions, and a large number of service units. Once Luzon had been secured, most of the air units and the 48th Division, as well as other units, were to be transferred to the Indies and Malaya. At that time Homma would receive the 65th Brigade to mop up remaining resistance and to garrison Luzon. The 16th Division would then move south and occupy the Visayas and Mindanao.

The 14th Army commander had also counted on having the support of a joint Army and Navy air force of 600 planes. But one of the two air brigades of the 5th Air Group and some of the naval air units originally destined for the Philippines were transferred to other operations. The addition of the 24th Air Regiment to the 5th Air Group at the last moment brought the combined air and naval strength committed to the Philippine campaign to about 500 combat aircraft.

Air and Naval Plans

Air operations against the Philippines would begin on the morning of X Day when planes of the Army’s 5th Air Group and the Navy’s 11th Air Fleet would strike American air forces on Luzon. These attacks would continue until American air strength had been destroyed. For reasons of security, there was to be no aerial or submarine reconnaissance before the attack, except for high-altitude aerial photographs of landing sites.13

By arrangement between the Japanese Army and Navy commanders, Army air units were to operate north of the 16th degree of latitude, a line stretching across Luzon from Lingayen on the west coast to the San Ildefonso Peninsula on the east. Naval air units were made responsible for the area south of this line, which included Clark Field, the vital Manila area, Cavite, and the harbor defenses. This line was determined by the range of Army and Navy aircraft. The Navy Zero fighters had the longer range and were therefore assigned missions in the Manila area. Carrier planes of the 4th Carrier Division, originally based at Palau, were to provide

air support for the landings at Davao and Legaspi.14

Once the advance units of 14th Army had landed and secured airfields, the main force of the 5th Air Group was to move up to the fields at Aparri, Laoag, and Vigan, while naval air units would base on the field at Legaspi and Davao. The airfield near Aparri was mistakenly believed to be suitable for heavy bombers and the bulk of the 5th Air Group was ordered there. It was anticipated that the forward displacement of the air forces would be completed by the sixth or seventh day of operations. During this week a naval task force from the 3rd Fleet was to provide protection for the convoys and carry out antisubmarine measures in the Formosa area and in Philippine waters.

Naval surface forces assigned to the Philippines operations were under the 3rd Fleet. This fleet, commanded by Admiral Takahashi, was primarily an amphibious force with supporting cruisers and destroyers. Its principal mission was to support the landings in the Philippines by minelaying, reconnaissance, escorting the troops during the voyage to the targets, and protecting them during landing operations. No provision was made for surface bombardment of shore objectives, presumably in the interests of secrecy.15

Because of the many landings to be made at widely scattered points in the Philippine archipelago it was necessary to organize the 3rd Fleet into numerous special task forces. For the landing on Batan Island the Third Surprise Attack Force of 1 destroyer, 4 torpedo boats, and other small craft was organized. The naval escort for the landing of the advance units on Luzon consisted of the First, Second, and Fourth Surprise Attack Forces, each composed of 1 light cruiser, 6 or 7 destroyers, transports, and other auxiliary craft. The Legaspi Force (Forth Surprise Attack Force) was to be staged at Palau, and since it could not be supported by the planes of the 11th Air Fleet it included the South Philippines Support Force, comprising the 4th Carrier Division and 2 seaplane carriers with 20 planes each. The units landing at Davao were to be covered by this same force.

To support the main landings Admiral Takahashi created the Close Cover Force, which he commanded directly, composed of 1 light and 2 heavy cruisers, and 2 converted seaplane tenders. Two battleships and 3 heavy cruisers from Vice Adm. Nobutake Kondo’s 2nd Fleet then operating in Malayan and East Indian waters, were also to support he landings, which would be additionally supported by 3 of the escort groups. The Lamon Bay Attack Group, in addition to 1 light cruiser and 6 destroyers, included 6 converted gunboats and 1 battalion of naval troops.

Concentration of Forces

Early in November the forces assigned to the Philippine campaign began to move to their designated jump-off points. The 5th Air Group arrived in southern Formosa from Manchuria during the latter part of the month. On 23 November two of the advance detachments stationed in Formosa boarded ship at Takao and sailed to Mako in the Pescadores. Between 27

November and 6 December the 48th Division (less detachments) concentrated at Mako, Takoa, and Kirun, and made final preparations for the coming invasion. The first units of the 16th Division sailed from Nagoya in Japan on 20 November, followed five days later by the remainder of the division. Part of this division concentrated at Palau and the main body at Amami Oshima in the Ryukyus. On 1 December, when General Homma established his command post at Takao, he received final instructions from Southern Army. Operations would begin on 8 December (Tokyo time).

The Plan of Defense

Plans for the defense of the Philippine Islands had been in existence for many years when General MacArthur returned to active duty. The latest revision of these plans, completed in April 1941 and called War Plan ORANGE-3 (WPO-3), was based on the joint Army-Navy ORANGE plan of 1938, one of the many “color” plans developed during the prewar years. Each color plan dealt with a different situation, ORANGE covering an emergency in which only the United States and Japan would be involved. In this sense, the plan was strategically unrealistic and completely outdated by 1941. Tactically , however, the plan was an excellent one and its provisions for defense were applicable under any local situation.16

WPO-3

In War Plan ORANGE it was assumed that the Japanese attack would come without a declaration of war and with less than forty-eight hours’ warning so that it would not be possible to provide reinforcements from the United States for some time. The defense would therefore have t be conducted entirely by the military and naval forces already in the Philippines, supported by such forces as were available locally. The last category included any organized elements of the Philippine Army which might be inducted into the service of the United States under the Tydings-McDuffie Act.

An analysis of Japanese capabilities, as of 1 July 1940, led the Philippine Department planners to believe that the enemy would send an expedition of about 100,000 men to capture Manila and its harbor defenses in order to occupy the Philippines, sever the American line of communications, and deny the United States a naval base in the Far East. It was expected that this operation would be undertaken with the greatest secrecy and that it would precede or coincide with a declaration of war. The garrison therefore could expect little or no warning. The attack would probably come during the dry season, shortly after the rice crop was harvested, in December or January. The enemy was assumed to have extensive knowledge of the terrain and of American strength and dispositions, and would probably be assisted by the 30,000 Japanese in the Islands.

Army planners in the Philippines expected the Japanese to make their major attack against the island of Luzon and to employ strong ground forces with heavy air and naval support. They would probably

land in many places simultaneously in order to spread thin the defending forces and assure the success of at least one of the landings. Secondary landings or feints were also expected. It was considered possible that the Japanese might attempt in a surprise move to seize the harbor defenses with a small force at the opening of hostilities. Enemy air operations would consist of long-range reconnaissance and bombardment, probably coming without warning and coordinated with the landings. The Japanese would probably also attempt to establish air bases on Luzon very early in the campaign in order to destroy American air power and bomb military installations.

Under WPO-3 the mission of the Philippine garrison was to hold the entrance to Manila Bay and deny its use to Japanese naval forces. There was no intention that American troops should fight anywhere but in central Luzon. U.S. Army forces, constituting the Initial Protective Force, had the main task of preventing enemy landings. Failing in this, they were to defeat those forces which succeeded in landing. If, despite these attempts, the enemy proved successful, the Initial Protective Force was to engage in delaying action but not at the expense of the primary mission, the defense of Manila Bay. Every attempt was to be made to hold back the Japanese advance while withdrawing to the Bataan peninsula. Bataan was recognized as the key to the control of Manila Bay, and it was to be defended to the “last extremity.”

To reinforce the Initial Protective Force, Philippine Army units were to be mobilized immediately upon the outbreak of war and would be ready to participate in the defense of Bataan. If used as anticipated in WPO-3, which was prepared before July 1941, the Philippine Army would be under the command of the Philippine Department commander and would be utilized to defend Manila Bay. The plan did not contemplate using Philippine Army units for the defense of the entire archipelago.

WPO-3 divided Luzon, the principle theater of operations, into six sectors with a mobile reserve. Detailed plans for the defense of each sector were made by the sector commanders. The commander of the Philippine Division, the only U.S. Army division in the Philippines, in addition to conducting operations in the sector or sectors assigned to him, was to organize the defenses of Bataan and to command operations there if necessary.

Air support was to be provided by the 4th Composite Group, the predecessor of the Far East Air Force. This group was to obtain information of enemy location, strength, and disposition by continuous reconnaissance, attack the Japanese whenever conditions were favorable, and support ground operations. in order to keep this air force in operation as long as possible, its planes were to be employed “conservatively” and every effort was to be made to supplement the strength of the group by taking over the Philippine Army Air Corps and commercial planes.

The navy was to set up defensive coastal areas at the entrances to Manila and Subic Bays. At the first sign of an attack a defensive area was to be set up around Manila to control all shipping and a patrol system established for Manila and Subic Bays. The Army, through the Department quartermaster, would control all shore facilities at the port of Manila.

The supply plan in WPO-3 was a complicated one. Provision had to be made to

supply the six sectors during the initial phase of operations and to withdraw supplies into Bataan where a base would be established to support a prolonged defense. Supply officers estimated that they would probably require enough supplies for 31,000 men (the Bataan Defense Force)—later raised to 40,000 men—to last 180 days. The defense reserve already on hand, except for ammunition, was considered by the planners sufficient to supply such a force for the period required in a defensive situation. The bulk of the supplies was stored in the Manila area which lacked adequate protection from attacking aircraft. In the event it became necessary to move the supplies to Corregidor and Bataan, the enemy would have to be delayed long enough to carry out this operation.

Prior to the start of operations on Bataan, supplies were to be moved rapidly to the peninsula. At the same time the Corregidor reserves, set first at a 6-month supply for 7,000 men and then for 10,000 men, were to be brought up to the authorized allotment. Philippine Department depots and installations in the Manila area were to be maintained just as long as the tactical situation permitted. Depots at Fort Stotsenburg, Fort William McKinley, Tarlac, San Fernando, Manila, and elsewhere would supply the various sectors. A Bataan Service Area was to be established, initially to assist in organizing the final defense positions and ultimately to supply the entire force after it had withdrawn to Bataan for the last stand. All stock in the Department, except those of the Harbor Defenses of Manila and Subic Bays, would eventually be transferred to Bataan.

Plans for local procurement included the exploitation of the Manila area with its commercial warehouses, factories, and transportation facilities. Procurement districts, coinciding roughly with the sector boundaries, would be established later.

Troops would take the field with two days of Class I supplies (rations), one emergency rations, and two days of fire. Class I and III supplies (gasoline and lubricants) would be issued automatically thereafter at rail or navigation heads; Class II, IV, and V supplies (clothing, construction and other heavy equipment, and ammunition) would be requisitioned from depots as needed. The issue of supplies to Philippine Army units would depend upon the speed with which they were mobilized and their location.

The transportation of troops and equipment, the planners realized, would be a difficult problem. There was a large number of passenger buses on Luzon, centrally organized and operated. The 4,000 trucks on the islands were of varying type, size, and condition and were mainly individually owned. Passenger buses were to be requisitioned immediately by the Army for use as personnel carriers. Since it would take longer to requisition trucks, cargo requirements were to be kept to an absolute minimum. In the initial move by the mobile forces toward the threatened beaches, little difficulty was expected with motor transportation. later, as supply requirements rose and as troops moved back toward Bataan (if the enemy could not be repelled at the beaches), motor pools were to be formed. When Philippine Army units were mobilized the drain on the motor transport services was expected to increase greatly since these units had no organic motor transportation.

Nothing was said in WPO-3 about what

was to happen after the defenses on Bataan crumbled. Presumably by that time, estimated at six months, the U.S. Pacific Fleet would have fought its way across the Pacific, won a victory over the Combined Fleet, and made secure the line of communications. The men and supplies collected on the west coast during that time would then begin to reach the Philippines in a steady stream. The Philippine garrison, thus reinforced, could then counterattack and drive the enemy into the sea.

Actually, no one in a position of authority at that time (April 1941) believed that anything like this would happen. Informed naval opinion estimated that it would require at least two years for the Pacific Fleet to fight its way across the Pacific. There was no plan to concentrate men and supplies on the west coast and no schedule for their movement to the Philippines. Army planners in early 1941 believed that at the end of six months, if not sooner, supplies would be exhausted and the garrison would go down in defeat. WPO-3 did not say this; instead it said nothing at all. And everyone hoped that when the time came something could be done, some plan improvised to relieve or rescue the men stranded 7,000 miles across the Pacific.17

The MacArthur Plan

General MacArthur had the answer to those who saw no way out of the difficulty in the Philippines. The defeatist and defensive WPO-3 was to be transformed into an aggressive plan whose object would be the defeat of any enemy that attempted the conquest of the Philippines. An optimist by nature, with implicit faith in the Philippine people, MacArthur was able to inspire the confidence and loyalty of his associates and staff. His optimism was contagious and infected the highest officials in the War Department and the government. By the fall of 1941 there was a firm conviction in Washington and in the Philippines that, given sufficient time, a Japanese attack could be successfully resisted.

In pressing for a more aggressive plan, enlarged in scope to include the entire archipelago, MacArthur could rely on having a far stronger force than any of his predecessors. His growing air force included by the end of November 1941 thirty-five B-17s and almost 100 fighters of the latest type. Many more were on their way. The performance of the heavy bombers in early 1941 justified the hope that the South China Sea would be successfully blockaded by air and that the Islands could be made a “self-sustaining fortress.”18

MacArthur could also count on the Philippine Army’s ten reserve divisions, then being mobilized and trained, and one regular division. During his term as Military Advisor, he had worked out the general concept of his strategy as well as detailed plans for the use of this national army. As commander of U.S. Army Forces in the Far East he could plan on the use of the regular U.S. Army garrison as well as the Philippine Army. He was in an excellent position, therefore, to persuade the War Department to approve his own concepts for the defense of the Philippines.

Almost from the date of his assumption of command, MacArthur began to think about replacing WPO-3 with a new

plan.19 From the first, as is evident from his establishment of the Philippine Coast Artillery Command, he apparently intended to defend the inland seas and the entrances to Manila and Subic Bays. By September his plans had progressed sufficiently to enable him to inform General Wainwright of his intention to reorganize the forces in the Philippines and to give that officer his choice of commands.20

The opportunity to request a change in plans for the defense of the Philippines came in October, after MacArthur received a copy of the new war plan, RAINBOW 5, prepared by the Joint Board some months earlier. This plan, which was world-wide in its provisions and conformed to arrangements with the British staff, called for a defensive strategy in the Pacific and Far East and recognized Germany as the main enemy in the event of a war with the Axis. Based on the assumption that the United States would be at war with more than one nation and would be allied with Great Britain, RAINBOW accepted implicitly the loss of the Philippines, Wake, and Guam. Like ORANGE, it assigned Army and Navy forces in the Philippines the mission of defending the Philippine Coastal Frontier, defined as those land and sea areas which it would be necessary to hold in order to defend Manila and Subic Bays. Also, as in ORANGE, the defense was to be conducted entirely by Army and Navy forces already in the Philippines, augmented by such local forces as were available.21 No reinforcements could be expected.

MacArthur immediately objected to those provisions of RAINBOW relating to the Philippines and called for the revision of the plan on the ground that it failed to recognize either the creation of a high command for the Far East or the mobilization of the Philippine Army. In a strong letter to the War Department on 1 October, the former Chief of Staff pointed out that he would soon have a force of approximately 200,000 men organized into eleven divisions with corresponding corps and army troops, as well as a strengthened air force. There could be no adequate defense of Manila Bay or of Luzon, he said, if an enemy was to be allowed to land and secure control of any of the southern islands. With the “wide scope of possible enemy operations, especially aviation,” he thought such landings possible. He urged, therefore, that the “citadel type defense” of Manila Bay provided in the ORANGE and RAINBOW plans be changed to an active defense of all the islands in the Philippines. “The strength and composition of the defense forces projected here,” General MacArthur asserted, “are believed to be sufficient to accomplish such a mission.”22

The reply from Washington came promptly. On the 18th General Marshall informed MacArthur that a revision of the Army mission had been drafted in the War Department and was then awaiting action by the Joint Board, “with approval

General Macarthur with Maj. Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright on 10 October 1941

expected within the next ten days.” MacArthur’s recommendation that the Philippine Coastal Frontier be redefined to include all the islands in the archipelago, Marshall continued, would also be presented to the Joint Board for approval. The assignment of a broader mission than that contained in RAINBOW, Marshall explained, was made possible because of the increased importance of the Philippines “as a result of the alignment of Japan with the Axis, followed by the outbreak of was between Germany and Russia.”23 General Marshall took advantage of the fact that Brereton was just then leaving for the Far East to send his reply to MacArthur by personal courier.

Brereton arrived in Manila on 3 November and was warmly greeted by his commander in chief. After reading Marshall’s note, MacArthur, in Brereton’s words, “acted like a small boy who had been told that he is going to get a holiday from school.” He jumped up from his desk, threw his arms around Brereton and exclaimed, “Lewis you are just as welcome as the flowers in May.” Turning to his chief of staff, General Sutherland, he said, “Dick, they are going to give us everything we have asked for.”24

With this notice that his plans would soon be approved by the Joint Board, MacArthur immediately organized his forces to execute the larger mission. On 4 November he formally established the North and South Luzon Forces, and the Visayan-Mindanao Force, all of which had actually been in existence for several months already.25

Approval by the Joint Board of the RAINBOW revisions requested by MacArthur was forwarded from Washington on 21 November. In the accompanying letter, General Marshall made the significant observation that air reinforcements to the Philippines had “modified that conception [purely defensive operations] of Army action in this area to include strong air operations in the furtherance of the strategic defensive.”26 He also told MacArthur to go ahead with his plans “on the basis of your interpretation of the basic war plan.”

In the revised joint RAINBOW plan, the Philippine Coastal Frontier, which had been defined as consisting of Luzon and the land and sea areas necessary to defend that island, was redefined to include “all the land and sea areas necessary for the defense of the Philippine Archipelago.”27 In effect, this gave MacArthur authority to defend all of the Philippine Islands.

The Army task originally assigned in RAINBOW was simply to defend the coastal frontier. The November revision not only enlarged the coastal frontier but gave MacArthur the following additional tasks:

1. Support the Navy in raiding Japanese sea communications and destroying Axis forces.

2. Conduct air raids against Japanese forces and installations within tactical operating radius of available bases.

3. Cooperate with the Associated Powers in the defense of the territories of these Powers in accordance with approved policies and agreements.28

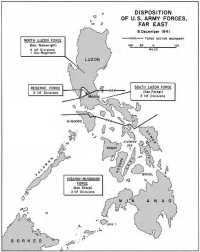

Map 2: Disposition of U.S. Army Forces, Far East, 8 December 1941

It also provided specifically for a defense reserve for 180 days, instead of the 90-day level originally granted to General Grunert. These additional tasks recognized the existence of an effective air force in the Philippines capable of striking at Japanese lines of communications and bases, such as Formosa, and the fact that the Philippine Army had been inducted into federal service by including it with forces available to accomplish the tasks assigned.

Once his plan to defend all of the islands had been approved, General MacArthur was able, on 3 December, to define the missions of the four major tactical commands created a month earlier. (Map 2) The North Luzon Force, which had been under the command of Brig. Gen. Edward P. King, Jr., from 3 to 28 November, now came under General Wainwright. This force had responsibility for the most critical sector in the Philippines, including part of the central plains area, Lingayen Gulf, the Zambales coast, and the Bataan peninsula. General Wainwright was instructed to protect airfields and prevent hostile landings in his area, particularly at those points opening into the central plains and the road net leading to Manila. In case of a successful landing the enemy was to be destroyed. In contrast to WPO-3, which provided for a withdrawal to Bataan, MacArthur’s plan stated there was to be “no withdrawal from beach positions.” The beaches were to “be held at all costs.”29

Immediately on receipt of these instructions General Wainwright was to prepare detailed plans to execute his mission. Frontline units were to make a reconnaissance of their sectors and emplace their weapons. Positions four hours distant from the front lines were to be selected for the assembly of troops.

On 3 December, when Wainwright received his mission, his North Luzon Force consisted of three Philippine Army divisions—the 11th, 21st, and 31st—the 26th Cavalry (PS), one battalion of the 45th Infantry (PS) on Bataan, two batteries of 155-mm guns, and one battery of 2.95-inch mountain guns. The 71st Division (PA), though assigned to North Luzon Force, could be committed only on the authority of USAFFE. Wainwright was promised additional troops when they arrived from the United States or were mobilized by the Philippine Army.

The South Luzon Force, under Brig. Gen. George M. Parker, Jr., was assigned the area generally south and east of Manila. Like the force to the north, it was to protect the airfields in its sector and prevent hostile landings. General Parker was also enjoined to hold the beaches at all costs. The South Luzon Force was much smaller than that in the north. It consisted initially of only two Philippine Army divisions, the 41st and 51st, and a battery of field artillery. Additional units were to be assigned at a later date when they became available.30

The Visayan-Mindanao Force under Brig. Gen. William F. Sharp was charged with the defense of the rest of the archipelago. Its primary mission was to protect the airfields to be built in the Visayas; its secondary mission was to “prevent landings of hostile raiding parties, paying particular attention to the cities and essential public utilities.” Since landing in force south of

Luzon would not have had any decisive results, no mention was made of the necessity of holding the beaches.31

Table 6—Assignment of Forces, USAFFE, 3 December 1941

| Troop Assignment | ||

| Sector | U.S. Army | Philippine Army |

| North Luzon Force | Force Hq and Hq Co (U.S.), 26th Cavalry (PS), One bn, 45th Inf (PS), Btry A 23 FA (Pk) (PS), Btrys B and C 86th FA (PS), 66th QM Troop (Pk) (PS) | 11th Division, 21st Division, 31st Division, 71 Division (used as directed by USAFFE) |

| South Luzon Force | Force Hq and Hq Co (U.S.), Hq and Hq Btry, Btry A, 86th FA (PS) | 41st Division, 51st Division |

| Visayan-Mindanao Force | Force Hq and Hq Co (PS) | 61st Division, 81st Division, 101st Division |

| Reserve Force | Hq, Philippine Dept, Philippine Division (less one bn), 86th FA (PS) less dets, Far East Air Force | 91st Division Hq, Philippine Army |

| Harbor Defenses | Headquarters, 59th CA (U.S.), 60th CA (AA) (U.S.), 91st CA (PS), 92nd CA (PS), 200th CA (U.S.) assigned to PCAC |

Source: Ltr Orders, CG USAFFE to CG NLF, SLF, V-MF, 3 Dec 41, AG 381 (12–3–41) Phil Rcds; USAFFE-USFIP Rpt of Opns, pp. 17–18.

The Visayan-Mindanao sector would also include the coastal defenses of the inland seas when these were completed and General Sharp was to provide protection for these as well. One battalion of the force was to be prepared to move to Del Monte in Mindanao with the mission of guarding the recently completed bomber base there. No American or Philippine Scout troops were assigned to the Visayan-Mindanao Force, except those in headquarters. For the rest, the force consisted of the 61st, 81st, and 101st Division, all Philippine Army. (See Table 6)

On Luzon, between the North and South Luzon Forces was the reserve area, including the city of Manila and the heavily congested area just to the north. This area was directly under the control of MacArthur’s headquarters and contained the Philippine Division (less one battalion), the 91st Division (PA), the 86th Field Artillery (PS),

the Far East Air Force, and the headquarters of the Philippine Department and the Philippine Army. The defense of the entrance to Manila and Subic Bays was left, as it always had been, to Gen. Moore’s Harbor Defenses augmented by the Philippine Coast Artillery Command.32

During the last few months of 1941 the training of both U.S. Army and Philippine Army units progressed at an accelerated pace. The strength of the Scouts, an elite organization with a high esprit de corps, had been brought up to its authorized strength of 12,000 quickly. Membership in Scout units was considered a high honor by Filipinos and the strictest standards were followed in selection. To provide the training for the new Scout units, as well as Philippine Army units, a large number of officers was authorized for USAFFE. By the fall of 1941 they began to arrive in Manila. Training of U.S. Army units was also intensified during this period. By the beginning of December, General Wainwright later wrote, “the American and Philippine Scout organizations were fit, trained in combat principles and ready to take the field in any emergency.” The omission of Philippine Army units is significant.33

The Last Days of Peace

Already there had been warnings of an approaching crisis. On 24 November the Pacific and Asiatic Fleet commanders had been told that the prospects for an agreement with Japan were slight and that Japanese troop movements indicated that “a surprise aggressive movement in any direction, including attack on Philippines or Guam was a possibility.”34 Three days later a stronger message, which the War Department considered a “final alert,” went out to Hawaii and the Philippines. The Army commanders, MacArthur and lt. Gen. Walter C. Short, were told:

Negotiations with Japan appear to be terminated to all practical purposes with only the barest possibility that the Japanese Government might come back and offer to continue. Japanese future action unpredictable but hostile action possible at any moment. If hostilities cannot, repeat cannot, be avoided the United States desires that Japan commit the first overt act. This policy should not, repeat not, be construed as restricting you to a course of action that might jeopardize your defense. Prior to hostile Japanese action you are directed to undertake such reconnaissance and other measures as you deem necessary. Report measures taken. Should hostilities occur you will carry out the tasks assigned in RAINBOW 5...35

At the same time the Navy Department sent to its Pacific commanders an even stronger message, to be passed on to the Army commanders in Hawaii and the Philippines. “This dispatch,” it read, “is to be considered a war warning. Negotiations with Japan ... have ceased and an aggressive move by Japan is expected

within the next few days.” Navy commanders were alerted against the possibility of a Japanese invasion of the Philippines, Thailand, or Malaya, and were told to take appropriate defensive measures.36

Immediately on receipt of the 27 November warning, MacArthur, Hart, and the Hon. Francis B. Sayre, U.S. High Commissioner to the Philippine Islands, met to discuss the measures to be taken. Sayre presented the President’s view to Mr. Quezon and told him that Roosevelt was relying upon the full cooperation of the Commonwealth.37 The next day MacArthur reported to the Chief of Staff the measures taken in the Philippines to prepare for a Japanese attack. Air reconnaissance had been extended and intensified “in conjunction with the Navy” and measures for ground security had been taken. “Within the limitations imposed by present state of development of this theater of operations,” he said, “everything is in readiness for the conduct of a successful defense.”38

The first week of December 1941 was a tense one for those in the Philippines who had been informed of the latest steps in the negotiations with Japan. American planes continued to notice heavy Japanese ships movements in the direction of Malaya, and unidentified aircraft—presumed to be Japanese—were detected over Luzon. On the 5th of December the commander of Britain’s Far Easter Fleet, Admiral Sir Tom Phillips, came to Manila to confer with Admiral Hart and General MacArthur about joint plans for defense. The next day news was received that a Japanese force had been sighted in the Gulf of Siam heading westward. Admiral Phillips left immediately by plane for Singapore where his flagship, Prince of Wales, lay at anchor, next to the battle cruiser Repulse.39

On 6 December, Saturday, MacArthur’s headquarters ordered North Luzon Force to be ready to move promptly to its assigned positions on beach defense, and Wainwright noted that around his headquarters at Stotsenburg “the tension could be cut with a knife.”40 In response to a warning against sabotage, MacArthur told General Arnold that a full air alert was in effect and all aircraft dispersed and placed under guard.41

Sunday, 7 December—it was the 6th in Washington—was a normal day, “nothing ominous in the atmosphere, no forebodings or shadows cast by coming events.”42 Men went about their work as usual. The only excitement arose from the fact that the Clipper, with its anxiously awaited mail sacks, was due. The last letters from home had reached the Islands ten days before.

That night the 27th Bombardment Group gave a party, recalled as a gala affair with “the best entertainment this side of Minsky’s,” at the Manila Hotel in honor of General Brereton.43 Brereton records conversations with Rear Adm. William R. Purnell

and Brig. Gen. Richard K. Sutherland, Hart’s and MacArthur’s chiefs of staff, during the course of the evening. Purnell told him that “It was only a question of days or perhaps hours until the shooting started” and that he was standing by for a call from Admiral Hart. Sutherland confirmed what Purnell had said, adding that the War and Navy Departments believed hostilities might begin at any time. Brereton then immediately instructed his chief of staff to place all air units on “combat alert” as of Monday morning, 8 December.44

Except for the few senior officers who had an intimate knowledge of events, men went to bed that night with no premonition that the next day would be different from the last. The Clipper had not arrived, and the last thoughts of many were of family and home, and the hope that the morrow would bring “cheerful and newsy letters.”45 Many listened to the radio before going to bed, but the news was not much different from that of previous days. Some heard American music for the last time. At Fort Stotsenburg a few officers of the 194th Tank Battalion listened to the Concerto in B Flat Minor before turning in. On the last night of peace Tschaikowsky’s poignant music made an impression which was to be deep and lasting.46