Chapter 14: The End of an Era

On 26 December, Manila was declared an open city. All newspapers published the text of the proclamation and radio stations broadcast the news through the day. A huge banner bearing the words Open City and No Shooting was strung across the front of the city hall. That night the blackout ended and Manila was ablaze with light.1

With the evacuation of the government and the army, a feeling of foreboding and terror spread through the city, and the exodus, which had ceased after the first confusion of war, began again. “The roads back into the hills,” noted one observer, “were black with people striving to reach their native villages ... The few trains still running into the provinces were literally jammed to the car tops.”2 The business district was deserted and there were few cars along Dewey Boulevard.

Here and there a few shops made a brave attempt at a holiday spirit with displays of tinsel and brightly wrapped gifts. On the Escolta, two Santa Clauses with the traditional white beards and red costumes looked strangely out of place. One walked up and down as if dazed while the other, more practical, piled sandbags before the entrance to his shop. “No girls in slacks and shorts were bicycling along the water front,” wrote Maj. Carlos Romulo reminiscently, “and there were no horseback riders on the bridle path ... the Yacht Club, the night clubs and hotels ... all looked like funeral parlors.”3 “Let it be known,” reported NBC correspondent Bert Silen, “that our Christmas Eve was the darkest and gloomiest I ever hope to spend.”4

Late on the night of 26 December Radio Tokyo acknowledged receipt of the Manila broadcasts declaring the capital an open city.5 Official notification to 14th Army came later, either on the 28th or after, when Imperial General Headquarters forwarded the information from Tokyo. Apparently MacArthur made no attempt to notify the Japanese forces in the Philippines of his intentions, but a mimeographed announcement of the open city declaration was in the hands of the Japanese troops by 31 December.6

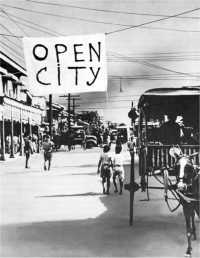

The Open City (Japanese photograph)

Either the Japanese in the Philippines were unaware of the open city declaration or they chose to ignore it, for enemy aircraft were over the Manila area on 27 December. The Army’s 5th Air Group sent 7 light and 4 heavy bombers against Nichols Field, and at least 2 fighters over the port district that day.7 But the main bombing strikes, directed against the Manila Bay and Pasig River areas, were made by naval aircraft. For three hours at midday, successive waves of unopposed bombers over Manila wrought great destruction on port installations and buildings in the Intramuros, the ancient walled city of the Spaniards. The attack against shipping continued the next day, with additional damage to the port area.8

Ed: As already noted in footnote 18 (Chapter 10):

“... The first specification in the charge against General Homma when he was tried as a war criminal in Manila in 1946 was the violation of an open city. Since Manila was used as a base of supplies, and since a U.S. Army headquarters was based in the city and troops passed through it after 26 December, it is difficult to see how Manila could be considered an open city between 26 and 31 December 1941. ...”

By New Year’s Eve the rear echelon of USAFFE headquarters under General Marshall had completed its work and was prepared to leave the “open city.” The capital was subdued but ready to greet the New Year. Hotels, nightclubs, and cabarets were opened, a dance was held at the Fiesta Pavilion of the Manila Hotel, and many women donned evening gowns for the first time since the start of the war. But no sirens were sounded as in the past to herald the new year; there was no exploding of fire-crackers, no tooting of horns, and no bright lights from naval ships in the bay lighting the sky. The only fireworks came from burning military installations. Along Manila streets the uncollected garbage of many days lay almost unnoticed.9

While a few citizens drank and danced, most of the bars closed at 2100. A large number of bartenders, in what someone termed a “scotched-earth policy,” smashed the remaining bottles to prevent their falling into Japanese hands.10

The next morning the quartermaster stores in the port area were thrown open to the public and great crowds hurried towards the piers. About to be burned, the sheds yielded a wide assortment of booty to the delighted Filipinos. The ice plant, filled with frozen food, was also thrown open. Not all the residents were at the piers; many attended church services for the Japanese were expected that afternoon.11

For almost forty years Manila had been the outpost of American civilization in the Orient. Now the badly mauled port area was quiet and dead as the old year. From the waters of Manila Bay rose the funnels of sunken ships and along the waterfront stood the blackened, empty walls and the battered piers, mute epitaph to one of the finest harbors in the Far East.12

The city was surrounded by an inferno of flame, noise, and smoke. Fuel supplies at Fort McKinley to the southeast, installations that survived the bombing at Nichols Field to the south, and the ruins of Cavite across Manila Bay were demolished in great bursts of flame and explosion. The bewildered and frightened population was further panic-stricken by the soaring flames from the oil tanks at Pandacan, which ate up surrounding warehouses and buildings

and sent up black clouds of smoke. The flaming oil floated along the Pasig and set other fires along the banks. And from the air the enemy continued to drop bombs, adding even more fuel to the great conflagration which swept huge areas in and around the city. “To the native population of Manila,” commented one observer, “it seemed like the end of the world.”13

The Occupation of Manila

On the first day of the New Year the Japanese 48th Division and the 4th and 7th Tank Regiments were twelve miles above the northern outskirts of Manila. To the south that night advance elements of General Morioka’s 16th Division reached Manila Bay at a point less than ten miles from the capital city.14 With two divisions “ready to go,” Homma stopped the advance on the outskirts of the capital over the protests of both divisional commanders. “If those division went in together from south and north,” he explained later, “anything might happen.”15

Both divisions could have entered Manila on New Year’s Day and expected to do so. When the order to advance did not come, Lt. Gen. Yuichi Tsuchibashi, 48th Division commander, sent Homma an urgent message at 1040, pointing out that the great fires had dissipated “the Army’s hope of preserving the city of Manila” and that “to rescue Manila from this conflagration” he planned to enter the capital in force. From Homma he requested approval for his plan.16 This was followed by a plea from the division’s chief of staff, who wrote: “I beseech you at the order of my superior to promptly approve the previously presented plan.17

Immediately after the 14th Army command post completed its movement from Binalonan to Cabanatuan, a staff conference was held at 1900 on New Year’s Day to decide on the method of entry into Manila. Two plans were discussed: one to send a force into the city immediately, as proposed by the 48th Division commander; the other to dispatch a “military commission” to the capital to urge its surrender while the troops remained outside the city.

The former plan was finally adopted, and at 2000 the 48th Division was ordered to seize Manila and prevent its destruction. Similar orders were given the 16th Division at 1000 on 2 January. General Morioka would also occupy Cavite and Batangas.18 The line of the Pasig River, which flowed through the capital and into Manila Bay, was set as operational boundary between the two divisions. That night supplementary orders from General Homma fixed the size of the force entering Manila from the north at three infantry battalions of the 48th Division. The 16th Division was seemingly left free to determine the number of its troops entering Manila. Further order apparently directed that the city was not to

be entered until the 2nd, for no entry was made that night.19

Inside the city a newspaper extra at noon on New Year’s Day declared the enemy to be on the verge of entry and advised inhabitants to remain in their homes and await further orders from the Philippine authorities in control. Anticipating confinement in internment camps, American residents immediately packed toilet articles and a change of clothing.20 Word of the impending entry of the Japanese reached Corregidor quickly. MacArthur reported to the War Department on the morning of the 2nd that Japanese troops would enter Manila that afternoon. His information was accurate enough to enable him to predict that the force would be small and that its duties would be limited to the maintenance of law and order, “which would indicate that there will be no violence.”21 That morning Japanese nationals were released from custody. The crowds, laden with stores from the quartermaster warehouses, began to break into business establishments and wholesale looting began.22 The once proud city, covered with the ashes and filth of destruction, was difficult to recognize as the beautiful and orderly metropolis it had been less than a month before.

Finally, at 1745 on Friday, 2 January 1942, the Japanese entered Manila. Maj. Gen. Koichi Abe, 48th Division infantry group commander, led one battalion of the 1st Formosa and two of the 47th Infantry into the northern sector of the capital. Simultaneously, from the south, the 16th Reconnaissance Regiment and a battalion of the 20th Infantry also entered.23 Accompanied by released Japanese civilians, who acted as interpreters, the occupying troops posted guards at strategic points and set about securing the city.24 “The joyful voices of the Japanese residents,” reported General Morioka, “were overwhelming.”25

The voices of the other residents were not so joyful. Throughout the city at important intersections Japanese officers and interpreters set up card tables and checked pedestrians. All “enemy aliens,” British and Americans, were ordered to remain at home until they could be registered and investigated. The only Caucasians who walked the streets unmolested were Germans, Italians, and Spaniards.26

All that night Japanese trucks poured into the city, their occupants taking over private hotels and some public buildings as billets. Enemy troops moved into the University of the Philippines and other school buildings. The next morning the only cars on the street were those driven by Japanese officers and civilians. From their radiators flew the flag of the Rising Sun. Spanish, French, Italian, German, Portuguese, and Thai flags could also be seen. The vault of the national treasury at the Intendencia Building was sealed and a large placard announced the building and its contents to be the property of the Japanese Government. The banks remained closed and the doors

Japanese Light Tanks moving toward Manila on the day the city was entered

of Manila restaurants were also shut. Newspaper publication was briefly suspended and then began again under Japanese control. The few stores that were open did a land-office business with Japanese officers who bought up brooches and watches with colorful occupation pesos.27

Governmental departments of the Philippine Commonwealth were placed under “protective custody.” The courts were temporarily suspended, utilities were taken over by the Japanese, and a bewildering list of licenses and permits was issued to control the economic life of the Islands. Japanese sick and wounded were moved into the Chinese General Hospital and three wards of the Philippine General Hospital. All British and Americans were ordered to report for internment, and nearly 3,000 were herded together on the campus of Santo Tomas University. “Thereafter,” reported the Japanese, “peace and order were gradually restored to Manila.”28

The restoration of “peace and order” required the Japanese to place many restrictions on the civilian population. On 5 January a “warning” appeared in heavy black type across the top of the Manila Tribune. “Any one who inflicts, or attempts to inflict, an injury upon Japanese soldiers or individuals,” it read, “shall be shot to death;” but “if the assailant, or attempted assailant,

cannot be found, we will hold ten influential persons as hostages who live in and about the streets or municipalities where the event happened.” The warning concluded with the admonition that “the Filipinos should understand our real intentions and should work together with us to maintain public peace and order in the Philippines.”29

With the occupation of Manila, General Homma had successfully accomplished the mission assigned by Imperial General Headquarters. But he could draw small comfort from his success, for MacArthur’s forces were still intact. The newly formed Philippine Army, the Philippine Scouts, and the U.S. Army garrison had successfully escaped to Bataan and Corregidor. So long as they maintained their positions there, the Japanese would be unable to enter Manila Bay or use the Manila harbor. The Japanese had opened the back door to Manila Bay but the front door remained firmly closed.

Strategic Views on the Philippines

To the civilians who watched quietly from behind closed shutters as the Japanese entered their city it seemed incredible that the war was less than a month old. In that brief span of time, the enemy had made eight separate landings on widely dispersed beaches. He had driven out of the Philippines the Far East Air Force and the Asiatic Fleet. On Luzon he had marched north and south from each end of the island to join his forces before Manila. Casualties had been comparatively light and the main objective was now in his hands.

In that same time the Japanese had secured a foothold in Mindanao to the south and had gained control of the important harbor at Davao. Brig. Gen. William F. Sharp’s forces on that island were still intact, however, and held the airfield at Del Monte, the only field in the archipelago still capable of supporting heavy bombers. In the Visayas the Japanese had made no landings. There the scattered American and Philippine garrisons on Panay, Cebu, Bohol, Leyte, and other islands fortified their defenses and made plans for the day when the enemy would appear off their shores.

Elsewhere, the Japanese forces had set about exploiting their initial gains. Hong Kong had fallen to the 23rd Army on Christmas Day. General Yamashita’s 25th Army, which had landed on the Malay Peninsula on the first day of war, was now pushing ever closer to Singapore. Japanese forces in the Sulu Archipelago and Borneo consolidated their positions and prepared to move into the Netherlands Indies. The South Seas Detachment, which had seized Guam, was now ready to move on to Rabaul, while other units staged for operations in the Celebes–Ambon area. Important Burmese airfields had been attacked on 25 December and at the year’s end the 15th Army was concentrating in Thailand for its invasion of Burma. After the first rapid gains, the enemy was ready for further offensives. The Allies had little left to challenge the Japanese bid for supremacy in the Southwest Pacific and Southeast Asia.

General MacArthur attributed the success of the Japanese to American weakness on the sea and in the air. The enemy, he pointed out, now had “utter freedom of naval and air movements” and could be expected to extend its conquests southward into the Netherlands Indies, using Mindanao as a base of operations.30 If the

Japanese were able to seize the Netherlands Indies, he warned, the Allies would be forced to advance from Australia through the Dutch and British islands to regain the Philippines. He regarded it as essential, therefore, to halt the Japanese drive southward, and proposed that air forces should be rushed to the Southwest Pacific. Operating from advance bases, these planes could prevent the Japanese from developing airfields. Concurrently, with strong naval action to keep open the line of communication to Mindanao, Japanese air forces were to be neutralized by Allied air power, and then ground forces would be landed there. He had already done all he could to support such action, MacArthur told the War Department, by sending his air force to Australia and the Netherlands Indies and by supporting Mindanao with reinforcements and ammunition. “I wish to emphasize,” he concluded, “the necessity for naval action and for rapid execution by land, sea, and air.”31

Receiving no reply to this message, General MacArthur took the occasion, on 1 January, when asked about the evacuation of President Quezon, to emphasize his isolated position and to remind the Chief of Staff of his strategic concept for a combined effort by land, sea, and air forces through the Netherlands Indies to Mindanao. Quezon’s departure, he warned, would undoubtedly be followed by the collapse of the will to fight on the part of the Filipinos, and he pointedly added that, aside from 7,000 combat troops (exclusive of air corps), his army consisted of Filipinos. “In view of the Filipinos effort,” he declared, “the United States must move strongly to their support or withdraw in shame from the Orient.”32

Just a week later, as his forces withdrew behind the first line of defenses on Bataan, MacArthur outlined for the Chief of Staff the preparations he was making for the arrival of an expeditionary force in Mindanao. These included transfer of equipment for one division, the movement of nine P-40s and 650 men of the 19th Bombardment Group to Del Monte, and plans to develop additional landing fields there. It was essential, he wrote, to inaugurate a system of blockade-running to Mindanao since supplies were low.

Our air force bombardment missions from south should quickly eliminate hostile air from Davao and our pursuit should go into Del Monte without delay. Establishment of air force will permit immediate extension into Visayas and attacks on enemy forces in Luzon. ... An Army Corps should be landed in Mindanao at the earliest possible date. ... Enemy appears to have tendency to become overconfident and time is ripe for brilliant thrust with air carriers.33

MacArthur’s pleas for a major Allied effort in the Southwest Pacific were received with sympathy in Washington, where the first wartime United States-British conference on strategy was in session. The British recognized the importance of the threat in the Far East and agreed that munitions and supplies should go there, even though such shipments represented a diversion from the agreed strategy that the main effort should be made against Germany first. “The President and Prime Minister, Colonel

Stimson and Colonel Knox, the British Chiefs of Staff and our corresponding officials,” General Marshall told MacArthur, “have been surveying every possibility looking toward the quick development of strength in the Far East so as to break the enemy’s hold on the Philippines.”

Though all were agreed on the need for action in the Southwest Pacific, little could be done. The loss in capital ships, Marshall explained, prevented naval convoys for heavy reinforcements and the concentration of strong naval forces in the Southwest Pacific such as MacArthur was requesting. Heavy bombers were on the way, via Africa and Hawaii, and pursuit planes were being sent by every ship, so that the Allies should soon have aerial supremacy in the Southwest Pacific. “Our great hope,” Marshall told MacArthur, “is that the rapid development of an overwhelming air power on the Malay Barrier will cut the Japanese communications south of Borneo and permit an assault in the southern Philippines.” The naval carrier raids MacArthur was asking for were not ruled out entirely but little hope was offered for such an effort. Marshall closed his message on a note of encouragement for the future and the assurance that “every day of time you gain is vital to the concentration of overwhelming power necessary for our purpose.”34

Actually, the American and British staffs in Washington had already agreed upon the strategy for the Far East: to hold the Malay Barrier from the Malay Peninsula through Sumatra and Java to Australia. This line was considered the basic Allied defensive position in the Far East, and the retention of its east and west anchors, Australia and Burma, was therefore regarded as essential. The latter had additional strategic importance because it was essential to the support of China and the defense of India. The Allies were agreed that land, sea, and air forces should operate as far forward of the barrier as possible in order to halt the Japanese advance southward. The support of the Philippine garrison and the re-establishment of the line of communications through the Netherlands Indies to Luzon apparently came after the more important task of holding Australia and Burma.35

During the first week in January the War Plans Division of the General Staff, which had been studying the possibility of sending an expedition to the relief of the Philippine garrison, came to the conclusion that the forces required could not be placed in the Far East in time. While this reason was probably the overriding consideration in its recommendation that operations to relieve the Philippines not be undertaken, the War Plans Division went on to point out that the dispatch of so large a force would constitute “an entirely unjustifiable diversion of forces from the principal theater—the Atlantic.” The greatest effort which could be justified on strategic grounds was to hold the Malay Barrier while projecting operations as far north as possible to provide maximum defense in depth. This view was essentially that already agreed upon by the Combined Chiefs of Staff. The War Plans Division therefore recommended that, “for the present,” operations in the Far East should be limited to these objectives.36

The War Plans Division study is of considerable interest, not only for the effect it may have had on MacArthur’s requests for a joint advance through the Netherlands Indies to Mindanao, but also for its realistic appraisal of the strategic situation in the Far East and the importance of the Philippine Islands. Accepting General MacArthur’s estimate of Japanese strength in the Philippines and of the length of time he could hold out against serious attack—three months—the Army planners agreed that the loss of the Philippines, “the key to the Far East position of the Associated Powers,” would be a decisive blow, followed probably by the fall of the Netherlands Indies and Singapore.37 Australian and British trade routes would then be seriously threatened, while Japan’s strength would be increased by control of the raw material in the Indies. The isolation of China was “almost certain to follow.”38 This analysis coincided with MacArthur’s, as did the plan of operations outlined to recover the Philippines.

It was when the planners considered the means necessary to carry out these operations that they found themselves in disagreement with General MacArthur. They estimated that 1,464 aircraft of various types, only about half of which were available, would be necessary to advance from Australia to Luzon. The difference would have to come from other areas—Hawaii, Panama, and the United States—and from lend-lease aircraft already committed. Additional airfields would have to be built in Australia and along the line of advance. The line of communications to Australia would have to be made secure and a logistical organization developed to support the drive northward. Such an effort, the planners estimated, would require very large naval resources. With the vessels already in the area, the Allies would have to transfer 7 to 9 capital ships, 5 to 7 carriers, about 50 destroyers, 60 submarines, and the necessary auxiliary vessels from the Atlantic and Mediterranean to the Pacific and Far East. The diversion of naval forces might well result in the loss of the supply routes to Europe and the middle East and would severely limit the defense of the Western Hemisphere. It was not surprising, therefore, that the War Plans Division concluded that the relief of the Philippine garrison could not be accomplished in the three months left, and that the allocation of such sizable forces to the project would represent a major and unjustifiable diversion from the main effort.39

There is no record of any formal approval of the conclusions of the War Plans Division. Both Secretary Stimson and General Marshall noted the study but made no comment. If there had ever been any serious consideration given to MacArthur’s proposals to send an expedition to the relief of the beleaguered Philippine garrison, the War Plans study put an end to such hopes. But there was no relaxation of the determination to send General MacArthur whatever aid was within the means of the United States and its Allies. President Roosevelt had time and again stated his desire to do so and as late as 30 December had written Stimson that he wished the War Plans Division to explore every possible means of

relieving the Philippines. “I realize great risks are involved,” he said, “but the objective is important.”40

While the President’s stated desire remained the official policy of the government and the hope of the American people, the strategy evolved by the Allies placed more realistic limits to he objectives they hoped to attain. The conference then meeting in Washington agreed that the Allies must hold the Malay Barrier and established a theater of operations known as the ABDA (American-British-Dutch-Australian) area, with Gen. Sir Archibald P. Wavell in command, to coordinate the efforts of the various national forces in that region. This command, the first Allied command of the war, included the Philippines, the Netherlands Indies, Malaya, and Burma. Wavell’s mission was to hold the Malay Barrier against the advancing Japanese, but he was also directed to re-establish communications through the Netherlands Indies with Luzon and to support the Philippine garrison. Thus, General MacArthur was placed under Wavell’s command, but, explained General Marshall, “because of your present isolation this will have only nominal effect upon your command. ...”41

Actually, the organization of the ABDA area had no effect on operations in the Philippines, and aside from a formal acknowledgment between the two commanders there was no communication between the two headquarters. Although General Marshall pointed out that the new arrangement offered “the only feasible method for the eventual relief of the Philippines.”42 it was already clear to General MacArthur that the Allies were not going to make a determined effort to advance to his rescue.

It was perhaps just as well that the Americans and Filipinos who crowded into Bataan and took their positions behind the lines already established did not know how serious was the Allied position in the Far East and how remote were their chances for relief. Ahead of them were long, dreary months of starvation and hard fighting before they would be herded into prison camps. At least they could hope that help was on the way. Only General MacArthur and his immediate staff knew the worst.