Chapter 17: The Battle of the Points

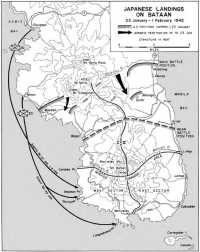

On the same day that General MacArthur made his decision to withdraw from the Abucay–Mauban line, 22 January, the Japanese set in motion a new series of operations potentially as dangerous to the American position on Bataan as General Nara’s assault against II Corps. Begun as a limited and local effort to exploit the break-through at Mauban, this fresh Japanese attack soon broadened into a major effort by 14th Army headquarters to outflank I Corps and cut the West Road. It was to be an end run, amphibious style, with its objectives far to me south, in the Service Command Area. Altogether the Japanese landed at three separate places, each a finger of land—a point—jutting out from the rocky coastline of western Bataan into the South China Sea. The first landings came on 23 January, as the American and Filipino troops began to fall back to he reserve battle position; the last, on 1 February, four days after the new line along the Pilar–Bagac road had been established. Although the Japanese committed only two battalions to this amphibious venture, it posed a threat out of all proportion to the size of the forces engaged. (Map 13)

The Service Command Area

When the American line was first established on Bataan on 7 January, defense of the southern tip of the peninsula, designated the Service Command Area, had been assigned to Brig. Gen. Allan C. McBride, MacArthur’s deputy for the Philippine Department. McBride’s command included, roughly, all of Bataan south of the Mariveles Mountains (the line Mamala River–Paysawan River formed the northern boundary), and was divided into an East and West Sector by the Paniguian River which flows southward into Mariveles Bay. Excluded from his control was the naval reservation near the town of Mariveles which was under the control of the Navy and defended by naval troops.1

The Service Command Area covered over 100 square miles. The distance around the tip of Bataan along the East and West Roads, from Mamala River on the Manila Bay side to the Paysawan River on the South China Sea coast, is at least forty miles. Inland, the country is extremely rugged and hilly, with numerous streams and rivers flowing rapidly through steep gullies into the surrounding waters. The coast line facing Manila Bay is fairly regular but the west coast, where the Japanese landings came, is heavily indented with tiny bays and inlets. The ground on this side of the peninsula is thickly forested almost to the shore line where the foothills of the central ranges end in abrupt cliffs. Sharp points of land extend from the “solid curved dark shore line” to form small bays. A short distance inland, and connected with a few of the more prominent points by jungle trails was the single-lane,

Map 13: Japanese Landings on Bataan

badly surfaced West Road, which wound its tortuous way northward from Mariveles.2

An adequate defense of this long and ragged coast line would have been difficult under the best of circumstances. With the miscellany of troops assigned to him, the task was an almost impossible one fro General McBride. Defending the east coast was a small Filipino force under Maj. Gen. Guillermo B. Francisco, commander of the 2nd Division (PA). To accomplish his mission he had the 2nd and 4th Constabulary Regiments, as well as other miscellaneous elements of his division, and one battery of 75-mm. guns (SPM). All that was available to guard the west coast against hostile landings was a mixed force of sailors, marines, airmen, Constabulary, and Philippine Army troops. Command of this sector was given to Brig. Gen. Clyde A. Selleck, 71st Division commander, on 8 January. Both sector commanders, Francisco and Selleck, had similar orders: to construct obstacles and station their troops along those beaches suitable for hostile landings, maintain observation posts on a 24-hour schedule, and make arrangements for a mobile reserve of battalion size, alerted and ready to move by bus on thirty minutes’ notice.3

General Selleck reported to McBride on the 9th and was told then “what I was to do and what I had to do it with.”4 His task was to defend ten miles of the western coast of Bataan from Caibobo Point southward to Mariveles, where the Navy’s responsibility began. The orders that had brought Selleck to the Service Command Area had also taken from him practically all of the combat elements of his 71st Division, leaving only the headquarters and service troops and one battalion of artillery (two 75-mm. guns plus one battery of 2.95-inch guns). In addition to these troops he had the 1st Constabulary Regiment from Francisco’s division and five grounded Air Forces pursuit squadrons. From Comdr. Francis J. Bridget, commanding the naval battalion at Mariveles, he received the assurance that the bluejackets would move in the West Sector should it southern extremity be threatened.5

The troops assigned to Selleck’s command constituted a curious force indeed. Many of the men had no infantry training and some had never fired a rifle. They wore different uniforms and came from different services. Altogether, they formed a heterogeneous group which, even under peacetime conditions, would have given any commander nightmares. The planeless airmen had been issued rifles and machine guns when they reached Bataan and ordered to train as infantry. They had two weeks to make the transformation. During this time, to quote one of the number, the “charged up and down mountains and beat the bush for Japs” in an effort to master the rudiments of infantry tactics.6 Their attempts to acquire proficiency in the use of the strange assortment of weapons in their possession

were hardly more successful. Some had the .30-caliber World War I Marlin machine gun; others, air corps .50-caliber guns on improvised mounts, Lewis .30-caliber machine guns, and Browning automatic rifles (BAR). In a group of 220 men there were only three bayonets, but, wrote one of their officers, “that was all right because only three ... men knew anything about using them.”7

The Constabulary had had little training as infantry, having served as a native police force prior to their induction into the Army in December. The naval battalion consisted of aviation ground crews left behind when Patrol Wing Ten flew south, sailors from the Canopus, men from the naval base at Mariveles, and from forty to sixty marines of an artillery unit. Of this group, only the marines had any knowledge of infantry weapons and tactics.8

With this force Selleck made his plans to resist invasion. He set up his command post along the West Road at KP 191, midway between the northern and southern extremities of his sector and about 5,000 yards inland from Quinauan Point. After a reconnaissance, he set his men to work cutting trails through the jungle and forest to the tips of the more important promontories along the coast. Barbed wire was strung, machine guns emplaced, lookouts posted, and wire and radio communications established. Selleck had four 6-inch naval guns, but had time to place only two of them, manned by naval gun crews, into position. One was at the northern extremity of his sector; the other, in the south. The third was to have been put in at Quinauan Point but the cement base was still hardening when the Japanese attacked. The road cut through the jungle to bring the gun in, however, proved invaluable later. Selleck also planned to install searchlights atop prominent headlands to forestall a surprise night landing but never received the equipment.9

On 22 January Selleck was still frantically seeking more men and more weapons for his sector, but the critical ten miles of beach, which had been practically undefended only two weeks before, was now manned by troops and organized into battalion sectors for defense. On the north was the 17th Pursuit Squadron, about two hundred men strong. Below it, down to the Anyasan River, was the 1st Battalion, 1st Constabulary Regiment. The 34th Pursuit Squadron, with 16 officers and 200 men, occupied the next sector of the beach which included Quinauan Point. Following in order from north to south were the 2nd Battalion of the Constabulary regiment, the 3rd Pursuit Squadron, and then the naval battalion. In reserve Selleck had the 3rd Battalion of the Constabulary regiment and the 20th and 21st Pursuit Squadron.10 There was little more he could do but wait and trust that his inexperienced and poorly equipped men would perform well if the Japanese should come ashore at any of the tiny inlets in the West Sector.

Longoskawayan and Quinauan Points

The Japanese scheme for a landing behind the American lines, a maneuver which General Yamashita was then employing with marked success in Malaya, originated with General Homma. On 14 January, when General Kimura, commander of the force driving down the West Road against Wainwright’s I Corps, came to call on him, Homma had expressed his concern over the “stalemate” on the west coast. Though he did not apparently issue orders for an amphibious move, he pointed out to Kimura the advantages of a landing to the enemy’s rear and told him that landing barges had already been ordered from Lingayen to Olongapo.11 With he detachment of about 5,000 men, including most of the 20th and 122nd Infantry, Kimura had then advanced down the west coast and on 21 January—when the 3rd Battalion of the 20th Infantry established itself firmly on the West Road behind Wainwright’s main line of resistance—appeared to be in an excellent position to reach Bagac from where he could move east to take II Corps from the rear.12

That his drive on Bagac could be continued “without difficulty” seemed certain to Kimura. But to forestall a possible enemy reaction south of Bagac and to protect his right (south) flank once he started to move east along the Pilar–Bagac road, Kimura decided to follow Homma’s suggestion and send a portion of his detachment by water from Moron to Caibobo Point, five air miles below Bagac. Selected to make this amphibious hop was Colonel Tsunehiro’s 2nd Battalion, 20th Infantry, then in reserve at Mayagao Point.13 This move, if properly reinforced and supported, might have had disastrous consequences for the American position on Bataan. It might well render Bagac, the western terminus of the Pilar–Bagac road, untenable for the Americans, but off all of the American and Filipino forces north of Bagac, and present a serious threat to II Corps on the east and Mariveles to the south.

That it did not was due to chance, poor seamanship, and the lack of adequate maps and charts. When the 2nd Battalion embarked in barges at Moron on the night of 22 January, it was ill prepared for the journey. Lack of time ruled out preparations ordinarily required to insure the success of an amphibious operation. The only map available was scaled at 1:200,000, virtually useless for picking out a single point along the heavily indented coast line.14 So deceptively does the western shore of Bataan merge into the looming silhouette of the Mariveles Mountains that it is difficult even in daylight to distinguish one headland from another, or even headland from cove. At night it is impossible.

Once afloat the Japanese found themselves in difficulty. The tides were treacherous and the voyage a rough one for the men crowded into the landing barges. Unexpected opposition developed when the U.S. Navy motor torpedo boat, PT-34, commanded by Lt. John D. Bulkeley and on a routine patrol mission, loomed up in the darkness. After a fifteen-minute fight, PT 34 sank one of the Japanese vessels. Unaware of the presence of other enemy vessels

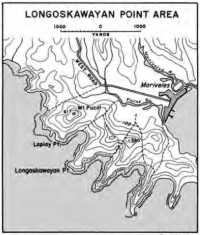

Map 14: Longosskawayan Point Area

in the area, the torpedo boat continued on its way. About an hour later Bulkeley encountered another of the Japanese landing craft and dealt it a fatal blow. Before it sank he managed to board and take two prisoners and a dispatch case with Japanese documents.15

By this time the Japanese invasion flotilla had not only lost its bearings but had split into two groups. Not a single Japanese soldier reached Caibobo Point. The first group, carrying about one third of the battalion, came ashore at Longoskawayan Point, ten air miles southeast of the objective. The rest of the battalion, by now a mélange of “platoons, companies, and sections,” landed seven miles up the coast, at Quinauan Point.16 At both places the Japanese achieved complete tactical surprise, but only at the expense of their own utter, through temporary, bewilderment.

The Landings

Longoskawayan Point, a fingerlike promontory jutting out into the South China Sea and only 3,000 yards west of Mariveles Harbor, is the southern coast of a small bay whose northern shore is formed by Lapiay Point. (Map 14) Four hundred yards wide at its tip and twice that at the base, Longoskawayan Point is only 700 yards long. Skirting its narrow coast are rocky cliffs about 100 feet high, covered with tall hardwood trees and the lush vegetation of the jungle. Visibility on the ground is limited by creepers, vines, and heavy undergrowth to a few yards; travel, to the narrow footpaths. The base of the point is less than 2,000 yards from Mariveles, the major port of entry for Bataan.

Map 14: Longoskawayan Point Area

Just inland from Lapiay Point is the 617-foot high Mt. Pucot, dominating the West Road and the harbor of Mariveles. Though within range of Corregidor’s heavy guns, its possession by the enemy would enable him to control the southern tip of Bataan with light artillery. This fact had been recognized early by the Navy and Commander Bridget had posted a 24-hour lookout on the summit of Mt. Pucot. He had, moreover, by agreement with General Selleck, promised to send his naval battalion into the area should the Japanese make an effort to seize the hill.17

The presence of a Japanese force in the vicinity of Mt. Pucot was first reported by the naval lookout at 0840 of the 23rd. The 300 Japanese, first estimated as a force of 200 by the Americans, had by this time moved inland from Longoskawayan and Lapiay Points and were approaching the slopes of the hill. Though Bridget had 600 men at Mariveles, only a portion of this force was available initially to meet the Japanese threat. As soon as he had dispatched a small force of marines and sailors to the hill he therefore requested reinforcements from Selleck, who promptly dispatched one pursuit squadron and a 2.95-inch mountain pack howitzer, with crew, from the 71st Division. Later in the day Bridget was further reinforced by a portion of the American 301st Chemical Company.18

When the first elements of Bridget’s battalion reached Mt. Pucot they found an advance detachment of Japanese already in possession. Before the enemy could dig in, the marines and bluejackets cleared the summit, then mopped up the machine-gun nests along the slopes. The 3rd Pursuit Squadron to the north suffered a few casualties the first day, when a squad, sent to investigate the firing, ran into a Japanese patrol. That night the men of the 301st Chemical Company took up a position along the north slope of Mt. Pucot and established contact with the 3rd Pursuit. Marines and sailors were posted on Mt. Pucot and along the ridges to the south. The howitzer was emplaced on a saddle between the two ridges southeast of the hill.19

When the sun rose the next morning, 24 January, the Americans discovered that during the night the Japanese had reoccupied their former positions along the west and south slopes of Mt. Pucot. This was the sailors’ and marines’ first experience with the Japanese penchant for night attacks. The Americans normally halted their attack about an hour before sunset, for the light faded quickly in the thick jungle where even during midday the light was muted. As the troops along the Abucay line had discovered, the Japanese frequently launched a counterattack shortly after dark. Unless a strong defense had been established before darkness, they were often able to regain the ground lost during the day. At the end of such a counterattack the Japanese usually settled down for the night and by daybreak were dug in along a new line. The Filipinos had displayed considerable nervousness during night attacks and had showed a tendency to fire intermittently through the night at the last known Japanese positions to their front. In their first encounter with the Japanese the men of Bridget’s battalion reacted in the same manner.

For the Japanese, this first encounter with the untrained bluejackets was a confusing and bewildering one. A Japanese soldier recorded in his diary that he had observed among the Americans a “new type of suicide squad” dressed in brightly colored uniforms. “Whenever these apparitions reached an open space,” he wrote, “they would attempt

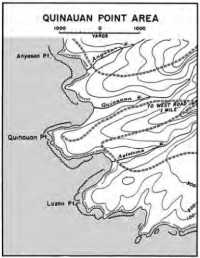

Map 15: Quinauan Point Area

to draw Japanese fire by sitting down, talking loudly and lighting cigarettes.”20 The brightly colored uniforms the Japanese noted were the result of an effort by the sailors to dye their whites khaki, an effort which produced a uniform of a “sickly mustard yellow” color.

During the 24th, in a day of vigorous patrol action, the marines and sailors succeeded in driving the Japanese back to Longoskawayan and Lapiay Points. By nightfall they were in control of Mt. Pucot and dug in along the ridges commanding the Japanese positions. But it was evident that the enemy force was too well entrenched and too strong to be expelled by less than a full battalion with supporting weapons.

Quinauan Pint, where the remaining 600 men of Colonel Tsunehiro’s 2nd Battalion, 20th Infantry, landed, is about midway between Mariveles and Bagac. Like Longoskawayan Point, it is a heavily timbered promontory with trees sixty to eighty feet high and with a thick jungle undergrowth. Two roads suitable for motor vehicles and tanks connected the points with the West Road. As in the landing to the south, the Japanese had by chance come ashore in an area where they could move inland rapidly, cut the I Corps line of communication, and threaten the southern tip of the peninsula. (Map 15)

Guarding the beaches along which the bulk of the 2nd Battalion landed was the 34th Pursuit Squadron. Some salvaged .50-caliber machine guns with improvised firing mechanisms had been emplaced along Quinauan Point, but evidently the airmen had failed to make proper provision for security for there was no warning of the presence of the enemy. The gun crews, awakened by the sound of the Japanese coming ashore in pitch blackness and unable to fire their .50-caliber machine guns, put up no resistance. After giving the alarm, they “crept back to their CP.”21 By the time the squadron was alerted the enemy had completed the hazardous landing and was safely on shore.

News of this landing reached General Selleck at his command post at KP 191 at 0230, six hours before the Longoskawayan landing was reported. He immediately dispatched Colonel Alexander, recently assigned American instructor of the 1st Philippine Constabulary, with the 3rd Battalion of that regiment to drive the enemy back into

the sea.22 In the time it took the Constabulary to reach the scene of action, the Japanese dug in and constructed defensive positions hear the base of the point. When the Constabulary attacked at about 1000 of the 23rd, therefore, it ran into strong opposition and was finally halted about 600 yards from the tip of the 1,000-yard-long peninsula. Alexander then tried to flank the Japanese position but that move, too, proved unsuccessful. Before the end of the day Alexander had reached the conclusion that he was facing a reinforced battalion, about seven hundred Japanese, and called on Selleck for tanks, artillery, and more infantry, preferably Americans or Scouts.23

Back at Selleck’s headquarters on the West Road, the 23rd was a hectic day. McBride was there and so was General Marshall, MacArthur’s deputy chief of staff. By that time news of the landing at Longoskawayan Point had been received and Sutherland had telephoned from Corregidor to say that the Japanese were landing at Caibobo Point. This last report, evidently based on the documents picked up by Lieutenant Bulkeley, was quickly proved erroneous. The three men were discussing plans for containing the Japanese at the two points and driving them back into the sea when Alexander’s request for reinforcements was received. McBride turned to Marshall and asked for tanks to send to Quinauan Point, but the urgent need for armor to cover the withdrawal from the Abucay line, scheduled to begin that night, made it impossible for Marshall to grant this request. The USAFFE deputy chief of staff left shortly for his own headquarters and late that night telephoned Selleck to relay MacArthur’s orders that he, Selleck, was to take personal charge of the attack on Quinauan Point the next morning.24

Meanwhile Colonel Alexander’s force had been augmented by the addition of two Bren gun carriers, sent in lieu of the tanks, and by elements of the 21st Pursuit Squadron, a company of Constabulary troops, and a provisional company formed from Selleck’s 71st Division headquarters company. Despite these reinforcements, attacks made during the 24th were unsuccessful and evening found the heterogeneous force in a holding position at the base of the peninsula.25 Present during the day’s action was Col. Charles A. Willoughby, intelligence officer on MacArthur’s staff. When Colonel Alexander was hit in the hand at 1600 it was Willoughby who accompanied the wounded man off the field.26

During the day there had been a change in command in the West Sector. General Marshall, who believed that only a small number of Japanese had come ashore at

Quinauan Point, had come to he conclusion that the offensive was not being pushed aggressively enough.27 He passed this estimate on to General Sutherland sometime during the night of 23–24 January, and, as a result, it was decided at USAFFE to relieve Selleck and send Col. Clinton A. Pierce to the West Sector to take over command. pierce had earned high praise and an enviable reputation for his handling of the 26th Cavalry (PS) since the start of the campaign and he seemed the right man for the job. In the early morning hours of the 24th, Colonel Pierce, who was to be promoted to brigadier general in six days, appeared at Selleck’s headquarters with the information that he had been ordered to assume command of the West Sector. This was the first intimation Selleck had that he was to be relieved. Later that day, after he received official notice of his relief from General McBride, Selleck took Pierce to Quinauan Point, turned of to him command of the sector, and left for the Service Command.28

The change in command of the West Sector occurred almost simultaneously with a reorganization of the command on Bataan following the withdrawal to the reserve battle position. On 25 January McBride was relieved of responsibility for beach defense and that mission was assigned by USAFFE to the two corps commanders. Francisco’s command along the east coast was merged with Parker’s corps, and the West Sector was redesignated the South Sector of Wainwright’s corps on the west. Pierce, as commander of the South Sector, now came directly under Wainwright’s command.29

Despite these administrative changes and the arrival of additional reinforcements—including the rest of the 21st Pursuit Squadron—the situation on Quinauan Point remained the same on the 25th and 26th. It was evident that trained infantry troops supported by artillery and tanks would be required to clear out the entrenched Japanese on both Quinauan and Longoskawayan Points. On the 26th USAFFE ordered the 2nd Battalion, 88th Field Artillery (PS), which had withdrawn to I Corps from the Abucay line, to the west coast to support the troops on beach defense. One battery of the Scout battalion’s 75-mm. guns went to Longoskawayan Point; another battery, to Quinauan Point.30

The dispatch of trained infantry troops into the threatened area was hastened when, on 27 January, the Japanese attempted to reinforce their stranded men at Quinauan. MacArthur’s headquarters quickly concluded that this move presaged a major enemy drive to cut the West Road and ordered Wainwright to clear the area as soon as possible. Wainwright thereupon ordered two Scout battalions, released from USAFFE reserve the day before, to move in and take over these sectors. The 2nd Battalion, 57th Infantry, was to go to Longoskawayan Point the 3rd Battalion, 45th, to Quinauan Point.31 When the movement of

these units was completed Wainwright hoped to wind up the action on both points in short order.

The Fight for Longoskawayan Point

The Americans on Longoskawayan Point had made little progress since 24 January. On that day Bridget had called up more of his men from Mariveles and had received from the 4th Marines on Corregidor two 81-mm. mortars and a machine-gun platoon. By morning of the 25th the two guns were in position on a saddle northwest of Mt. Pucot. Aided by an observation post on the hill, they had lobbed their shells accurately into the Japanese positions on both Longoskawayan and Lapiay Points. When the mortar fire lifted, patrols had moved in to seize both points. Lapiay had been abandoned and was occupied with no difficulty. But the men who attempted to reach Longoskawayan were driven back. There the Japanese were strongly entrenched and supported by machine guns and mortars. All efforts to drive them out that day failed and Bridget called for support from Corregidor.32

Since the morning of the 25th the crew of Corregidor’s Battery Geary (eight 12-inch mortars) had been waiting eagerly for permission to open fire on the Japanese. At 1000 this permission had been denied and Col. Paul D. Bunker, commander of the Seaward Defenses on Corregidor, had bone back to his quarters “inwardly raving with disappointment.”33 Finally, late that evening word had come from Maj. Gen. Edward P. King, Jr., USAFFE artillery officer, that the battery could fire in support of the naval battalion. At about midnight the men began their “first real shoot of the war.”34 Using 67-pound land-attack projectiles with superquick fuses, “which worked beautifully,” Battery Geary fired sixteen rounds at a range of 12,000 yards, only 2,000 short of extreme range. The results were most gratifying. After the fourth shot the forward observer on Mt. Pucot reported that such large fires had been started on Longoskawayan point that he could no longer see the target.35

This bombardment, the first hostile heavy caliber American coast artillery fire since the Civil War, made a strong impression on the Japanese. One of them later declared: “We were terrified. We could not see where the big shells or bombs were coming from; they seemed to be falling from the sky. Before I was wounded, my head was going round and round, and I did not know what to do. Some of my companions jumped off the cliff to escape the terrible fire.”36

Even with the aid of the heavy guns from Corregidor, Bridget’s battalion was unable to make any headway against the Japanese on the point. Unless reinforcements were received, not only was there little likelihood of an early end to the fight but there was a possibility that the enemy might even launch a counterattack. Fortunately, the reinforcements sent by Wainwright began to arrive. On the evening of the 26th the battery of 75-mm. guns from the 88th Field

Artillery arrived and next morning the guns were in place, ready for action.37

At 070, 27 January, all the guns that could be brought to bear on Longoskawayan Point—the 75-mm. battery of the 88th Field Artillery, the two 81-mm. mortars of the 4th Marines, the 2.95-inch pack howitzer from the 71st Field Artillery, and the 12-inch mortars of Battery Geary—opened fire with a deafening roar. The barrage lasted for more than an hour and when it lifted the infantry moved out to take the point.

Though it seemed that nobody “could be left alive” after so heavy a shelling, the marines and sailors who attempted to occupy Longoskawayan found the Japanese active indeed.38 Not only were all attempts to push ahead repulsed but, when a gap was inadvertently left open in the American line, the Japanese quickly infiltrated. For a time it appeared as though they would succeed in cutting off a portion of the naval battalion and only the hasty action of the 81-mm. mortars and the pack howitzer saved the situation. At the end of the day Bridget was no nearer success than he had been before the attack opened.

Prospects for the next day were considerably improved when, at dusk, the 500 Scouts of the 2nd Battalion of the 57th infantry, led by Lt. Col. Hal C. Granberry, reached Longoskawayan Point. That night they relieved the naval battalion and early the next morning moved out to the attack.39 In the line were Companies E and G, with F in reserve. The Scouts advanced steadily during the morning but halted when it became apparent that the artillery, its field of fire masked by Mt. Pucot, could not support the attack. A platoon of machine guns was set up on an adjoining promontory to the left to cover the tip of the point, and a platoon of the 88th Field Artillery moved to a new position from which it could fire on the Japanese.40 By nightfall the Scouts had advanced about two thirds of the length of Longoskawayan Point.

At dawn of the 29th, the Scouts moved back to their original line of departure to make way for a thirty-minute artillery preparation, to begin at 0700. Again the 12-inch mortars on Corregidor joined the guns off the point.41 A unique feature of this preparation was the participation by the minesweeper USS Quail, which stood offshore and fired at specified targets on land.42 Still supported by the Quail, which continued firing until 0855, the Scouts moved out again at 0730 only to discover that the Japanese had occupied the area won the day before. It was not until 1130 that the Scouts regained the line evacuated earlier in the morning. That afternoon Colonel Granberry put Company F into the line and within three hours the 2nd Battalion was in possession of the tip of Longoskawayan Point. Except for mopping up, a job left largely to the naval battalion and to armored launches, the fight for Longoskawayan Point was over.43 Next day the Scout

battalion rejoined its regiment at sector headquarters on the West Road, carrying with it a supply of canned salmon and rice, the gift of a grateful Commander Bridget.44

The cost of the action had not been excessive. In wiping out a force of 300 Japanese the American had suffered less than 100 casualties; 22 dead and 66 wounded. Half of the number killed and 40 of the wounded had been Scouts. Once again the Americans had learned the lesson, so often demonstrated during the campaign, that trained troops can accomplish easily and quickly what untrained soldiers find difficult and costly. But had it not been for the prompt action of the naval battalion, Mt. Pucot might well have been lost during the first day of action.

Although the Americans had not know it, the Japanese on Longoskawayan had never had a chance to inflict permanent damage for their location was unknown to higher headquarters. Indeed, neither Kimura, who had sent them out, nor Tsunehiro, the battalion commander, seems to have been aware, or even to have suspected, that a portion of the 2nd Battalion had landed so far south. Later, the Japanese expressed amazement and disbelief when they learned about this landing. One Japanese officer would not be convinced until he was shown the Japanese cemetery at Longoskawayan Point.45 Thus, even if they had succeeded in gaining Mt. Pucot, there was little likelihood that the small force of 300 Japanese at Longoskawayan Point could have exploited their advantage and seriously threatened the American position in southern Bataan.

The Fight for Quinauan Point

While the Japanese were being pushed off Longoskawayan Pint, the battle for Quinauan Point, seven miles to the north, continued. By 27 January the Japanese landing there had been contained but the fight had reached a stalemate. Against the 600 Japanese of Colonel Tsunehiro’s 2nd Battalion, 20th Infantry, Pierce had sent a miscellaneous and motley array of ill-assorted and ineffective troops numbering about 550 men and drawn from a wide variety of organizations: the V Interceptor Command, the 21st and 34th Pursuit Squadrons, headquarters of the 71st Division (PA), the 3rd Battalion, 1st Philippine Constabulary, and Company A, 803rd Engineers (US).46 It is not surprising, therefore, that little progress had been made in pushing the enemy into the sea.

On 27 January, it will be recalled, Wainwright had been ordered to ring the fight on the beaches to a quick conclusion and had dispatched the 3rd Battalion, 45th Infantry (PS), to Quinauan Point. By 0830 of the 28th, the entire Scout battalion, numbering about 500 men and led by Maj. Dudley G. Strickler, was in position at the point ready to start the attack. All units except the V Interceptor Command (150 men), which

remained to cover the beached below the cliff line, were relieved.47

The Scouts advanced three companies abreast in a skirmish line about 900 yards long, their flanks protected by the grounded airmen. Attached to each of the rifle companies was a machine-gun platoon, placed along the line at points where it was thought enemy resistance would be stiffest. The line stretched through dense jungle where the visibility was poor and the enemy well concealed. “The enemy never made any movements or signs of attacking our force,” wrote the Scout commander, “but just lay in wait for us to make a move and when we did casualties occurred and we still could not see even one enemy.”48

Under such conditions it is not surprising that the battalion was unable to make much progress during the day. Despite the fact that the machine guns were set up just to the rear of the front line and “shot-up” from top to bottom those trees that might conceal enemy riflemen, advances during the day were limited to ten and fifteen yards at some points. Progress along the flanks was somewhat better and in places the Scouts gained as much as 100 yards. By 1700, when the battalion halted to dig in for the night and have its evening meal of rice and canned salmon, Major Strickler had concluded that it would be impossible for his Scouts, aided only by the airmen, to take the point. He asked for reinforcements and that night Company B, 57th Infantry (PS), was attached to his battalion.49

On the 29th, shortly after dawn, the attack was resumed. Two platoons of Company B, 57th Infantry, were in position on the battalion right flank; the rest of the reinforcing company was in reserve. Despite the strengthened line no more progress was made on this day than had been made the day before. Again casualties were heavy, especially in the center where resistance was strongest.

The battle continued throughout the 30th and 31st , with about the same results. The Japanese were being pushed slowly toward the sea, but only at very heavy cost. No headway could be made at all against the enemy positions along the cliff and on the high ground about 200 yards inland from the tip of the point.

Hindering the advance as much as the enemy was the jungle. The entire area was covered with a dense forest and thick undergrowth that made all movement difficult and dangerous. Even without enemy opposition the troops could move through the jungle only with great difficulty, cutting away the vines and creepers that caught at their legs and stung their faces and bodies. The presence of concealed enemy riflemen and light machine-gun nests, invisible a few feet away, added immeasurably to the difficulty of the attacking troops. In such terrain, artillery, mortar, and armor could be of slight assistance and the advance had to be made by the rifleman almost unaided. It was a slow and costly process.

At daylight, 1 February, in an effort to reduce the opposition in the center, the infantry attack was preceded by a heavy but ineffective mortar operation. When it lifted the two center companies moved in quickly but were able to advance only a short distance before they were halted. Major Strickler then went forward to the front lines to

make a personal reconnaissance. He was last seen in the vicinity of Company B, 57th Infantry. After an intensive search during the day battalion headquarters regretfully reported that its commander was missing, presumably killed in action. Capt. Clifton A. Croom, battalion adjutant, assumed command.50

By now the battalion was sadly reduced in strength, with casualties estimated as high as 50 percent. The men, “:dead tired from loss of sleep and exposure,” would need help soon if the attack was to be pushed aggressively.51 On the afternoon of the 2nd Captain Croom asked General Pierce for tanks, a request, happily, that Pierce was now in a position to grant, for on the night of 31 January, on orders from MacArthur’s headquarters, General Weaver had sent the 192nd Tank Battalion (less one company) to the west coast. In less than two hours a platoon of three tanks from Company C was in position on the line.52

Late on the afternoon of the 2nd, with the aid of tanks, the attack was resumed. General Weaver, arriving as the tanks were making their third attack, was on hand to observe the action. This attack, like the others, failed to make any headway, and on Weaver’s insistence two more attacks, preceded by artillery preparation, were made, with little success. Late in the afternoon Col. Donald B. Hilton, executive officer of the 45th Infantry, arrived and assumed control of all troops on the point.53

The next morning the Scouts and tankers resumed the attack, but with little success. Stumps and fallen trees impeded the advance of the tanks whose usefulness was further limited by the absence of proper coordination between infantry and armor, and faulty communication and control. When the battalion halted at 1700 it was not far from its original line of departure. That night it was joined by Captain Dyess and seventy men from the 21st Pursuit Squadron which had been in the fight earlier but had been relieved when the Scouts had taken over the line on the 28th. “On our return,” wrote Dyess, “we found that the Scouts had occupied fifty yards more of the high jungle above the bay—at terrible cost to themselves. Their casualties had run about fifty percent. The sight and stench of death were everywhere. The jungle, droning with insects, was almost unbearably hot.”54

For the attack of the 4th Colonel Hilton received two additional tanks and a radio control car. Deploying his tanks across the narrow front and stationing men equipped with walkie-talkie sets with each tank, Hilton moved his reinforced battalion out early in the morning. The line moved forward steadily, the tanks, guided by directions from the radio control car, spraying the area to the front with their machine guns and knocking out strong points.

Success crowned this coordinated infantry-tank attack. By the end of the day the Japanese had been crowded into an area 100 yards wide and only 50 yards from the cliff at the edge of the point. Plainly visible to the Scouts were the Japanese soldiers and beyond them the blue water of the South China Sea. Suddenly the men witnessed

a remarkable sight. Screaming and yelling Japanese ripped off their uniforms and leaped off the cliff. Others scrambled over the edge and climbed down to prepared positions along the rock ledges. Down on the beach Japanese soldiers ran up and down wildly. “I’ll never forget the little Filipino who had set up an air-cooled machine gun at the brink and was peppering the crowded beach far below,” wrote one eyewitness. “At each burst he shrieked with laughter, beat his helmet against the ground, lay back to whoop with glee, then sat up to get in another burst.”55

Though the Americans reached the edge of the cliff the next morning, the fight was not yet over. The Japanese had holed up in caves along the cliff and in the narrow ravines leading down to the beaches. Every effort to drive them out during the next few days failed. Patrols which went down the ravines or the longer way around the beach to polish off the enemy only incurred heavy casualties. Though their case was hopeless the Japanese steadfastly refused to surrender. “The old rules of war,” wrote General Wainwright, “began to undergo a swift change in me. What had at first seemed a barbarous thought in the back of my mind now became less unsavory. I thought of General U.S. Grant’s land mine at Petersburg and made up my mind.”56

First he made arrangements to bring a small gunboat close in to shore to shell the area. Then, at dawn of the 6th, he sent in a platoon of the 71st Engineer Battalion (PA) under the supervision of Colonel Skerry, the North Luzon Force engineer, to assist the attacking troops—the 3rd Battalion, 45th Infantry, and Company B, 57th Infantry (PS)—in routing out the holed-up Japanese. Fifty-pound boxes of dynamite fired with time fuses were lowered over the cliff to the mouth of the caves. After a Scout engineer sergeant was fatally wounded while lowering one of the boxes, this method was abandoned in favor of throwing dynamite hand grenades (four stick of dynamite with a 30-second time fuse) along the length of the cliffs close to the bottom edges from where the Japanese fire had come. By this means most of the Japanese (about fifty) were forced into one large cave that was completely demolished by dynamite. All of the enemy had not yet been exterminated and when patrols entered the area, they encountered spasmodic fire.57

It was not until 8 February that the Japanese were finally exterminated. The job was done from the seaward side, as at Longoskawayan Point. Two armored naval motor launches armed with 37-mm. and machine guns, and two whaleboats, each with ten men from the 21st Pursuit Squadron on board, sailed from Mariveles at 0600 that morning. In command of the boats was Lt. Comdr. H.W. Goodall; Captain Dyess led the landing parties. At about 0800 the small flotilla arrived off Quinauan Point and the navy gunners took the beach under fire. Sheets lowered over the face of the cliff marked the Japanese positions. When the opposition on shore had been neutralized, the whaleboats, waiting a mile off the coast, came in to land the airmen. One group landed on the northern side of Quinauan Point, the other along the southern beaches. Both moved cautiously toward the tip of the peninsula while Scout patrols from the battalion on the cliffs above worked their way

down through the ravines. Despite attacks by three enemy dive bombers which hit the small boats and the men on shore, the operation was successfully concluded during the morning.58

The end of resistance on Quinauan Point marked the destruction of the 2nd Battalion, 20th Infantry. Three hundred of that battalion’s number had been killed at Longoskawayan; another 600, at Quinauan. In the words of General Homma, the entire battalion had been “lost without a trace.”59 But the cost had been heavy. The 82 casualties suffered at Longoskawayan were less than on fifth of the number lost at Quinauan. On 28 January when the 3rd Battalion, 45th Infantry, took over that sector it had numbered about 500 men. It marched out with only 200; 74 men had been killed and another 234 wounded. The other Scout units, Company B, 57th Infantry, left Quinauan Point with 40 men less than it had had ten days earlier. Other units suffered correspondingly high losses. Total casualties for the Quinauan Point fight amounted to almost 500 men.60 It was a heavy price to pay for the security of the West Road, but there was still a payment due, for the Japanese, on 27 January, had landed at yet another point on the west coast behind Wainwright’s front line.

Anyasan and Silaiim Points

General Kimura’s success against Wainwright’s Mauban line between 20 and 23 January had led 14th Army headquarters to revise its estimate of the situation and to prepare new plans for the occupation of Bataan. Originally, the main effort had been made against II Corps on the east. In view of Kimura’s success, General Homma now decided to place additional forces on the west and increase pressure against I Corps in the hope that he might yet score a speedy victory. On the 25th, therefore, he directed Lt. Gen. Susumu Morioka, 16th Division commander, who had come up from southern Luzon and was now in Manila with a portion of his division, to proceed to western Bataan with two battalions of infantry and the headquarters of the 21st Independent Engineer Regiment and there assume command of the operations against I Corps.61

The First Landing

Homma’s order of the 25th, though made two days after the landings at Longoskawayan and Quinauan, contained no reference to his effort to outflank I Corps by sea. Homma was not yet convinced that this amphibious venture should have the full support of 14th Army. The decision to reinforce Tsunehiro’s 2nd Battalion at Quinauan,

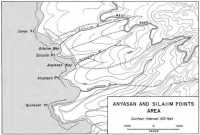

Map 16: Anyasan and Silaiim Points Area

the only landing of which the Japanese had knowledge, was made by General Morioka, Kimura’s immediate superior. To him, as to Kimura, the landing held out the promise of large results. Even before he left Manila, he ordered one company of the small force at his disposal to go to the aid of the 2nd Battalion, 20th Infantry. The company selected was from the same regiment’s 1st Battalion. It was to move with all speed from Manila to Olongapo and there pick up supplies for the trapped and hungry men “fighting a heroic battle” against a “superior enemy” on Quinauan Point.62

The reinforcing company reached Olongapo at the head of Subic Bay on the night of 26 January. At midnight it embarked in landing craft loaded with ammunition, rations, and supplies, and set sail for Quinauan. Once more poor seamanship and the lack of navigation charts and large-scale maps led the Japanese astray. This time they landed about 2,000 yards short of the objective, between the Anyasan and Silaiim Rivers, in the sector guarded by the 1st Battalion, 1st Philippine Constabulary.63 (Map 16)

The beach on which the Japanese craft ran aground was little different from that at Longoskawayan and Quinauan. The coast line here presented the same irregular appearance as that to the south. Dense tropical forest and thick undergrowth extended almost to the shore line, and the foothills

of the Mariveles Mountains formed steep cliffs about 100 feet high just in front of the beach. The two rivers, Silaiim on the north and Anyasan about 1,000 yards to the south, emptied into shallow bays, each bearing the name of the river. Separating the two bays was Silaiim Point, a narrow headland which formed the upper shore of the southern bay. The lower coast of the bay received it name from the southernmost of the two rivers. Thus, from north to south, presenting a confusion of identically named geographic features, were: Silaiim Bay, Silaiim River, Silaiim Point, Anyasan Bay, Anyasan River, and Anyasan Point. This confusion of points, when combined with those to the north and south, was as bewildering to the troops as it is, probably, to the reader. Their plight was most aptly expressed by one member of a wire crew, perched atop a telephone pole who, when asked where he was, replied, “For Christ’s sake, sir, I don’t know. I am somewhere between asinine and quinine points.”64

Inland, the ground was even more difficult than at Longoskawayan and Quinauan. Small streams branched off from the two rivers, dry at this time of the year, to create additional hazards to troop movements and to provide cover for the enemy. With only one access trail from the West Road to the beach, the task of maintaining communications and supplying troops to the front would be a difficult one. The absence of roads would also limit the effective use of tanks in formation and require their employment singly or in small numbers at isolated points. Similarly, the dense forest, by restricting observation and increasing the hazards of tree bursts, would limit the use of artillery and mortars. Like the fights then in progress at Longoskawayan and Quinauan, the struggle to drive off the Japanese between the Anyasan and Silaiim Rivers would be a job for the rifleman.65

In MacArthur’s headquarters, the new landing was regarded as the prelude to a major enemy offensive. Should this hostile force, thought to be of “considerable size,” establish contact with the Japanese on Quinauan Point to the south or advance as far as the West Road, only 2,700 yards away, it would present “a threat of no mean importance.”66

Coming ashore at about 0300 of the 27th, the confused and lost Japanese of the 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry, numbering about two hundred men, met no more resistance than had their fellows in the 2nd Battalion. The Constabulary troops on beach defense promptly took flight at the first approach of the enemy and the entire Constabulary battalion was soon dispersed. At dawn, when General Pierce received news of the landing, he immediately dispatched the 17th Pursuit Squadron, then in sector reserve, to meet the invaders.67

The grounded airmen moved out shortly after dawn. At the abandoned Constabulary command post, where breakfast still simmered in the pots. they discovered a smashed switchboard and an aid station complete with stretchers. After breakfasting on the food and reporting the situation to sector headquarters, the men set off jauntily for

the coast. As they did so, some men were heard inquiring how to fire their rifles.

More than a mile inland from the beach and about 400 yards distant from the vital West Road, they 17th Pursuit Squadron met the enemy’s advance patrols. The Japanese pulled back without offering serious resistance and the squadron was able to advance along the path between the two rivers until it was about 1,000 yards from the shore line. The Japanese had apparently established their front line positions here and the Americans’ easy march came to an abrupt halt. Joined at this point by the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Philippine Constabulary, which had just been in the fight against the Japanese roadblock to the north, the Americans dug in for the night.68 This was to be the easiest advance by the troops in the Anyasan–Silaiim sector.

The next day, 28 January, the airmen and Constabulary attacked during the morning. Either because the Japanese had pulled back or shifted position during the night, the Constabulary battalion was able to advance almost to the coast at Anyasan Bay. That night, when the Japanese appeared ready to counterattack, the Constabulary pulled back leaving the 17th Pursuit to fend for itself. The threat to the West Road now seemed serious, for there was every indication that the Japanese force, whose size and precise location were still not known, might burst out of the beachhead and create havoc behind the American lines.69

The situation was saved the next day when the Scouts of the 2nd Battalion, 45th Infantry, arrived on the scene, led by their executive officer, Capt. Arthur C. Biedenstein. General Pierce placed Biedenstein in charge of the operation and gave him the 1st Battalion, 1st Philippine Constabulary, and the 1st Battalion, 12th Infantry (PA)—both of which had just been relieved at Quinauan Point—to clear out the Japanese. To guard the West Road and insure the safety of the line of communication, he placed Company A, 57th Infantry (PS), on patrol to the rear.70

On 30 January, after a personal reconnaissance to locate the Japanese, Captain Biedenstein opened the attack. Calling for support from the 75-mm. guns of the 88th Field Artillery, whose Battery D was in position to assist the men in both the Quinauan and Anyasan–Silaiim sectors, he sent his Scouts out to regain the beach near the mouth of the Silaiim River. Either the battalion’s front line had been incorrectly reported to the artillery or plotted inaccurately, for the result of the preparation was almost disastrous. Without adequate communication between infantry and artillery and with high trees limiting observation and causing tree bursts, the Scouts soon found themselves under fire from their own guns. Before the artillery command post could be reached, four Scouts had been killed and sixteen more wounded. The offensive of the 30th came to an end even before it had fairly begun.71

That night the 57th infantry (less detachments) was moved to South Sector headquarters on the West Road with orders to prepare for operations in the Anyasan–Silaiim sector. Hardly had the regiment arrived when General Pierce called for a volunteer—a lieutenant colonel or major—to coordinate the activities of the troops already engaged on that front. Maj. Harold K. Johnson, who had been relieved as S-3 of the regiment a week earlier and had “nothing else specific to do,” volunteered for the job. “When I reported to General Pierce at 7:30 P.M.,” he wrote in his diary, “I found about as complete a lack of knowledge of conditions n the coast along which the Japanese had landed as could be imagined.”72

A personal reconnaissance on the night of the 30th did not greatly increase his knowledge of the enemy but it did give him a clearer picture of the disposition of the units now under his control. On the north, between Silaiim River and Canas point, was the 1st Battalion, 12th Infantry (PA), facing almost due north and with its right flank on the sea. Facing west and holding a line from the Silaiim River to the trail leading from Silaiim Point to the West Road, was the 2nd Battalion, 45th Infantry. Below it, to the left of the trail and extending the line south as far as the Anyasan River, was the 1st Battalion, 1st Constabulary. To the rear, along the trail, was the 17th Pursuit. Since there were no troops south of the Anyasan River, Johnson asked for and received permission to relieve Company A of the 57th infantry from its patrolling mission along the West Road and send it to Anyasan Point, the promontory south of the river bearing the same name. Its new mission was to establish contact with the enemy on the point in an effort to determine his strength and locate his positions.

Johnson’s efforts on the 31st were directed primarily toward securing information about the strength and disposition of the enemy. While Company A of the 57th Infantry reconnoitered Anyasan point to the south, the 1st Battalion, 12th Infantry, pivoted on its right (west) flank and swept in on the beaches of Silaiim Bay. At the same time the Scouts and Constabulary between the Anyasan and Silaiim Rivers pushed westward toward the sea. The 17th Pursuit remained in place, keeping open the line of supply and communications. Unopposed, the Scout and Philippine Army battalions cleared the area north of the Silaiim River during the morning, thus reducing the beachhead by about one third. The Constabulary troops, however, were stopped cold after an advance of about 100 yards. The Scout company moving out toward Anyasan Point failed to make any contact that day. Johnson now knew where the Japanese were dug in. But he still had no knowledge of their strength or defenses.

With this scanty information, Major Johnson concluded that there was no hope of clearing the area with the force he had. His 2nd Battalion, 45th Infantry, was in poor shape. It had reached the Anyasan–Silaiim sector after a grueling march from Abucay where it had been badly mauled. One of its companies had been hard hit and disorganized by fire from friendly artillery and casualties throughout the battalion had been heavy. The unopposed Scout company to the south could not be expected to make rapid progress through the jungle and it was too weak to attack alone if it should meet

an enemy force. Of the rest of his troops Johnson had no high opinion. He did not believe that the 17th Pursuit would be “particularly helpful in an assault,” or that the Constabulary would contribute much in an offensive. On the evening of the 31st, therefore, he asked General Pierce for more troops, and asserted that in his opinion only his own regiment, the 57th Infantry, then at sector headquarters, would be able to clear the Japanese out of the area. “No other troops,” he declared, “would make the necessary attacks.”73 That night the 57th Infantry was released to General Pierce, who immediately ordered it into the Anyasan–Silaiim area. Next morning Lt. Col. Edmund J. Lilly, Jr., commander of the 57th Infantry, assumed control of operations there and Major Johnson resumed his former post as S-3.

By the end of January the enemy had been isolated and contained. A strong force was assembling for a determined effort to root out the Japanese hiding in the canebrakes, thickets, and creek bottoms of the Anyasan and Silaiim Rivers. The Japanese at Longoskawayan Point had been killed or driven into the sea. At Quinauan Pint the slow costly process of attrition was under way. To General Pierce the situation everywhere in the South Sector seemed generally favorable. But appearances were deceptive, for already the Japanese had launched a desperate and final effort to reinforce their beachheads on the west coast.

The Second Landing

At the time it was made, USAFFE’s estimate that the first landing in the Anyasan–Silaiim sector presaged a major enemy effort to cut the West Road was incorrect. Events soon proved it prophetic, however, for on the evening of 27 January General Homma had for the first time lent his support to the landings. That day, in an order to General Morioka, he had directed that the beachhead at Quinauan Point be reinforced and that the augmented force drive inland to seize the heights of Mariveles and then the town itself.74

Morioka’s first efforts to comply with Homma’s orders were limited to attempts to drop rations, medicine, and supplies from the air to his beleaguered forces on the beaches. But the Japanese aircraft were unable to locate their own troops in the jungle. Supplies fell as often on Americans and Filipinos as they did on the starved Japanese. The Scouts of the 45th Infantry one day picked up twelve parachute packages containing food, medicine, ammunition, and maps. The rations consisted of a soluble pressed rice cake, sugar, a soy bean cake, a pink tablet with a strong salty taste, and “other ingredients [which] could not be determined.”75

While these efforts to supply the troops by air were in progress, Morioka assembled the troops he would require to reinforce the beachhead and push on to Mariveles. On 31 January he ordered the 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry, one company of which was already in the Anyasan–Silaiim area, to undertake this dangerous mission. Maj. Mitsuo Kimura, battalion commander, immediately

made his preparations to sail the next night.76

By this time Morioka had tipped his hand. First warning of the impending Japanese move had reached the Americans on the 28th when a Filipino patrol on the opposite side of Bataan had found a mimeographed order on the body of a slain Japanese officer. When translated, it revealed the Japanese intention to reinforce the beachheads and drive toward Mariveles. Thus warned, USAFFE took measures t counter the expected landings. Observers on the west coast were alerted and General Weaver, the tank commander, was directed to send one of his two tank battalions (less one company) to the threatened area. The few remaining P-40s were gassed, loaded with 100-pound antipersonnel bombs and .50-caliber ammunition, and ordered to stand by for a take-off at any time.77

The night of 1–2 February was clear, with a full moon. As the enemy flotilla sailed south it was spotted by American observers and a warning was flashed to MacArthur’s headquarters. The land, sea, and air forces so carefully prepared for just this moment, were immediately directed to meet and annihilate the enemy. The result was the first large coordinated joint attack of the campaign. While the motor torpedo boats sought targets offshore, the 26th Cavalry moved out from I Corps reserve to Caibobo Point to forestall a landing there. The four P-40s, all that remained of the Far East Air Force, took off from the strip near Cabcaben, cleared the Mariveles Mountains, and headed for the enemy flotilla of twelve or more barges. Sighting the target, they swooped low to release their 100-pound antipersonnel bombs, then turned for a strafing run over the landing boats.

By now the Japanese were nearing Quinauan Point. Their reception from the men on shore, themselves under fire from a Japanese vessel thought to be a cruiser or destroyer, was a warm one. Artillery shell fragments churned the sea around the landing boats as Battery D of the 88th Field Artillery and Battery E of the 301st let go with their 75s and 155s. Together, the two batteries fired a total of 1,000 rounds that night. Fire from the heavy machine guns and small arms of the Scout battalion on the point peppered the small boats and caused numerous casualties among the luckless men on board.

While the landing boats were being attacked by air, artillery, and infantry weapons, Pt 32 moved in to attack the Japanese warship, actually a minelayer, stationed off Quinauan Point to cover the landing of Major Kimura’s battalion. The enemy vessel turned her searchlight full on the patrol boat and let go with four or five salvos from two guns, thought to be of 6-inch caliber. The PT boat sought unsuccessfully to knock out the searchlight with machine gun fire, and then loosed two torpedoes. As she retired the men on board observed explosions on the enemy vessel, which later reported only slight damage from shore batteries.78

For the Americans and Filipinos who witnessed the battle in the clear light of the full moon, it was a beautiful and heartening sight to see the remnants of the enemy flotilla, crippled and badly beaten, turn away and sail north shortly after midnight. Homma’s plan to reinforce his troops on Quinauan Point had failed and in the first flush of victory the Americans believed the surviving Japanese had returned to Moron. But Major Kimura either had no intention of admitting defeat or was unable to make the return journey in his battered boats. With about half his original force he landed instead in the Anyasan–Silaiim area where he was joined by his battalions advance company.79 Once more, against an alerted and prepared foe, the Japanese had landed behind Wainwright’s line. All hope for an early end to the fight for Anyasan and Silaiim Points was now gone.

Colonel Lilly, who had assumed command of operations in the Anyasan–Silaiim sector on 1 February, spent the day in a thorough reconnaissance of the area. On the evening of the 1st he still had no knowledge of the strength of the Japanese, but he had concluded that he would be more likely to encounter the enemy in the jungle than along the river beds. The arrival of Japanese reinforcements apparently led to no change in plans formed the previous night, and on the morning of the 2nd he launched an attack with three Scout battalions abreast. on the north, its right flank resting on the dry bed of the Silaiim River, was the 2nd Battalion, 45th Infantry, now led by its commander, Lt. Col. Ross B. Smith. To its south (left) was the 3rd Battalion, 57th, and next to it the 1st Battalion (less Company B, at Quinauan) of the same regiment. The mission of the northernmost battalion was to seize the mouth of the river and the north side of Silaiim Point. The center unit, between the two rivers, would take the point itself while the 1st Battalion on the south was directed to take Anyasan Point. Guarding the north flank of the advance was the 1st Battalion, 12th Infantry, assigned to beach defense above Silaiim River. The 17th Pursuit Squadron remained astride the trail to the West Road to secure the line of communication. In reserve was the 2nd Battalion of Colonel Lilly’s 57th Infantry, recently arrived from Longoskawayan Point, and the Constabulary battalion.

The attack jumped off at daybreak, as the first rays of light filtered through the leafy branches of the high hardwood trees. Advancing cautiously through the luxuriant undergrowth, the two right (northern) battalions met resistance almost immediately. The southernmost battalion, however, met no opposition that day or during the four days that followed. But its progress was slow for the ground before it was exceedingly rough and difficult. The battalions to he north, after small gains, concluded that the force opposing them was a strong one and spent the rest of the day developing the hostile position.

On the 3rd tanks joined in the action. In answer to a request of the day before, Company C, 192nd Tank Battalion (less one platoon at Quinauan), consisting of nine tanks, had been sent forward from sector headquarters. Colonel Lilly placed them between

the two rivers, the only area even remotely suitable for tank operations. Restricted to the narrow trail and hampered by heavy jungle, the tanks were forced to advance in column and were utilized essentially as moving pillboxes.

At the outset tank-infantry coordination was poor, the foot soldiers having been directed to remain 100 to 150 yards behind the tanks. With their limited fields of fire and in column formation, the tanks were particularly vulnerable to enemy mine and grenade attack. It is not surprising, therefore, that on the first day the armor was used the results obtained were disappointing. In at least one case the result was tragic. The enemy, unimpeded by the Scouts who were well behind the tanks, disabled one of the tanks, set it on fire, then filled it with dirt. The crew never had a chance and was first cremated, then buried.80 After this experience the riflemen were instructed to work closely with the armor and four infantrymen were assigned to follow each tank. When the Japanese dropped down into their foxholes now to allow the tanks to pass, the foot soldiers picked them off before they could get back on their feet.

The greatest threat to the tanks came from enemy mines. The Japanese would dash from cover, fix a magnetic mine against the front of the tank and scurry for the trees. Or they would attach a mine to a string and drag it across the trail in front of an advancing tank. Had not the infantry provided close support, the tanks would not have lasted long in the Anyasan–Silaiim fight.

The employment of artillery also presented a difficult problem, as Colonel Lilly quickly discovered. The ground sloped up from the beach and there were no commanding heights along which to emplace the guns so that they could support the first-line troops. Tree bursts from the 75-mm. shells represented a real danger to friendly troops. The one battery of 155-mm. howitzers that was available had no fire direction equipment of any kind and could no be used for infantry support. In the absence of artillery forward observers, infantry rifle company commanders observed fire in front of their own lines and sent corrections to the artillery command post which had established communications directly with the assault companies.

The 2nd Battalion, 88th Field Artillery (PS), which was assigned the task of providing support for all the troops in Pierce’s South Sector, had to emplace its two four-gun batteries in pairs. To coordinate its fire the battalion had to lay thirty-eight miles of wire, in addition to utilizing the infantry communications net. The problem of firing from an altitude of 800 feet, through trees averaging 60 to 80 feet in height, at an enemy on an elevation of 100 feet or less and at a distance of about 4,000 yards, without hitting friendly front-line troops was a difficult one, and one that was never entirely solved. In the fight for Quinauan and Anyasan–Silaiim, the artillery battalion expended about 5,000 rounds, without appreciably affecting the course of the action.81

Machine guns, though available, were not employed widely in the fight for Anyasan and Silaiim Points, first, because the undergrowth limited the field of fire, and second, because of the difficulty of ammunition resupply. There was no way of brining up ammunition except by hand and it was hard enough to keep the riflemen supplied. Machine gunners, therefore, were employed as

ammunition carriers for the riflemen. Their use thus, observed Major Johnson, “out-weighed the advantages of their supporting fire.”82

Although the Scout units had both 60- and 81-mm. mortars, they had little or no ammunition for these weapons. They did use the 3-inch Stokes mortar ammunition in the 81-mm. weapon, but, in addition to the limitations imposed by the terrain, the efficiency of this weapon was severely curtailed by the abnormally high percentage of duds. To the end, the fight for Anyasan and Silaiim Points remained primarily a rifleman’s fight.

While infantry-tank and infantry-artillery coordination were worked out during the 3rd and 4th of February, the advance of the two right battalions—the 2nd Battalion, 45th Infantry, and the 3rd Battalion, 57th Infantry—proceeded slowly. Until the southern battalion fought its way through the jungle and established contact with the enemy on Anyasan Point, thus securing the left flank, the rest of the line had to proceed cautiously. Finally, on the 7th, this battalion reached the Japanese positions, but was roughly repulsed. American Air Corps troops and the Constabulary battalion were then sent in to join the fight. The Constabulary was placed on the right (north) of the 1st Battalion, 57th, with orders to maintain contact with the 3rd Battalion to he north. The Air Corps troops went in on the left and established contact with the Scouts on Quinauan Point, thus completing a continuous line from the northern edge of Silaiim Bay to the southern extremity of Quinauan Point, a distance of about 4,000 yards.

The troops all along the front now began to advance more rapidly. Progress was facilitated when, on the 8th, a platoon of 37-mm. guns was released from Quinauan, where the fight ended that day. The guns were emplaced on a promontory overlooking Anyasan Point from where they would take the Japanese supply dumps under fire. The end of resistance at Quinauan also made possible the return of Company B, 57th Infantry, to the heavily engaged 1st Battalion on Anyasan Point.83

By this time the debilitating effects of the half ration instituted a month earlier were becoming apparent. Some of the men grew listless and less eager to fight. Each day it became more difficult to push the front-line troops into aggressive action, and after the first five days it became necessary to rotate the assault battalions. Even the procurement of additional rations by the 57th Infantry, a Scout unit of high exprit de corps, did not improve matters much.

The necessity of feeding the troops during the daylight hours imposed further restrictions on combat efficiency by shortening the fighting day. The two meals were served shortly after daybreak and just before dark so that the action was usually broken off in time to set up defensive positions against night attacks and eat the last meal of the day. Even when operations were proceeding favorably, it was necessary to follow this procedure for, with the meager ration, it was essential that every man get his full share to maintain his efficiency in combat.

Fortunately, even with the half ration, the morale of the Scouts did not deteriorate. They understood, as many did not, that they were receiving all the food that a determined commander could get for them, and there was little looting or stealing from the kitchens. But the effect of the ration on the performance of troops in combat was

undeniable. “A prolonged period of reduced rations,” concluded Major Johnson, “destroys the will to fight almost entirely, and ... may even destroy the will to survive.”84

On 9 February, the 3rd Battalion, 57th Infantry, in the center of the line, was replaced by the rested and refreshed 2nd Battalion, with the result that the attack that day was pushed more aggressively. One enemy strongpoint which had held up the 3rd Battalion was taken during the afternoon, but the Japanese counterattacked that night to recapture the position. The following day, 10 February, the 2nd Battalion resumed its march, retook the strongpoint, and then continued to move forward steadily. By evening of the next day it had reached the mouth of the Anyasan River, squeezing out the Japanese and forcing them on to Silaiim Point, between the two rivers, and in front of the 45th Infantry Scouts who were advancing more slowly. The situation of Major Kimura’s remaining troops was desperate and their defeat a certainty.

As early as the 7th the Japanese had apparently realized that their forces on the west coast beachheads were doomed. From Major Kimura, commander of the troops at Silaiim, General Morioka received word that a “bitter battle” was in progress and that the enemy was attacking with tanks and artillery. “The battalion,” wrote Kimura, “is about to die gloriously.”85 General Morioka responded to this message by ordering the 21st Engineer Regiment to rescue the trapped men. On the night of the 7th the engineers, in thirty boats of varying sizes, left Olongapo for the beachheads. As they came in to shore to search for their stranded fellows they were met by artillery and machine-gun fire, as well as bombs from two P-40s. In the face of this strong opposition they returned empty-handed to Olongapo. The next night they tried again and this time succeeded in evacuating thirty-four of their wounded comrades. This was their last trip.86

Unable to evacuate his men, Morioka finally decided to relieve them from their assignment so that they could make a last desperate effort to save themselves. In orders sealed in bamboo tubes and dropped from the air, he instructed Major Kimura to bring his decimated battalion out by sea, on rafts or floats, and get them to Moron. If no other means were available the men would have to swim. Included in the orders was detailed information on tides, currents, the time of the rising and setting of the sun and moon, and directions for the construction of rafts. Unhappily for Kimura, copies of the orders fell into American hands, were quickly translated, and circulated to the troops on the front line. Thus alerted, riflemen along the beaches north of Silaiim got valuable target practice firing at Japanese swimmers and machine gunners were on the watch for rafts and floats. Only a few of the enemy were able to escape by sea. most of those who were not shot or captured probably drowned.87

But before his final annihilation Major Kimura made one last effort to break out of

the cordon which held him tight on Silaiim Point. At dawn, 12 February, with about two hundred men, he launched a counterattack against the 2nd Battalion, 45th Infantry. A gap about 100 yards wide had opened in that battalion’s line, between Companies, E and F, on the 9th, but this fact had never been reported to Colonel Lilly. An effort had been made t close it but when the Japanese counterattacked it was covered only by patrol. Driving in through the two companies, the Japanese met only scattered resistance in their pell-mell rush to escape. The weight of the attack was met by a machine gun section which fought heroically but unavailingly to stop the Japanese. One gun crew made good its escape after all its ammunition was gone, but the other, except for one man who had left to get more ammunition, was killed. The two gun crews together accounted for thirty Japanese.

Once they broke through the line the Japanese turned north toward the Silaiim River. At the mouth of the river were the command posts of the 17th Pursuit, which was patrolling the beach along Silaiim Bay, and of Company F, 45th Infantry. The Japanese attacked both command posts, wounding Capt. Raymond Sloan, commander of the 17th Pursuit, who died later.88

A hurried call for aid was sent to Colonel Lilly, and at about 1000, just as the 2nd Battalion, 45th Infantry, command post came under heavy machine gun fire, the 3rd Battalion, 57th Infantry, reached the threatened area. Two of its companies formed a skirmish line to fill in the gap left by the routed 17th Pursuit and finally tied in with the north company of the 2nd Battalion, 45th Infantry. About noon the Scouts attacked the Japanese and during the afternoon advanced steadily against stiff but disorganized resistance. The next morning the attack was resumed and by 1500 all units reached the beach, now littered with the equipment and clothing of those Japanese who had taken to the water to escape. The only enemy left were dead ones, and the beach was befouled with bloated and rotting bodies.

Few of the Japanese had been taken prisoner. As at Longoskawayan and Quinauan they showed a reluctance to surrender though their cause was hopeless. MacArthur’s headquarters, in its first effort to use psychological warfare, made available a sound truck and two nisei and urged Colonel Lilly to broadcast appeals to the Japanese to give themselves up. But the higher headquarters failed to provide a script for the nisei and placed on the regiment responsibility for the truck and the interpreters.

To the regiment’s reluctance to accept this responsibility was added its disinclination to take prisoners. The Scouts had found the bodies of their comrades behind Japanese lines so mutilated as to discourage any generous impulse toward those Japanese unfortunate enough to fall into their hands. Some of the bodies had been bayoneted in the back while the men had had their arms wired behind them. One rotting body had been found strung up by the thumbs with the toes just touching the ground, mute evidence of a slow and tortured end. Nor did the Japanese show any signs of gratitude when their lives were

spared. When one of them was brought to a battalion headquarters he had promptly attempted to destroy both himself and the headquarters with a hand grenade. It is not surprising, therefore, that “a passive resistance to the use of the sound truck developed and there were sufficient delays to that it was not used.”89

About eighty of the enemy had made good their escape from the beachhead during the counterattack of the 12th. Hiding out in the daytime and traveling only at night, they made their way northward by easy stages. Four days later they were discovered about seven miles from Silaiim Point and only one mile from the I Corps main line of resistance. Their undetected four-day march through the congested area behind I Corps can be attributed to the wildness of the country and to their skill in jungle warfare. Only the defensive barbed wire and cleared fields of fire along the font had prevented them from reaching their own lines. A squadron of the 26th Cavalry was sent from corps reserve on the 16th to root them out. It took two days and the help of troops from the 72nd and 92nd Infantry to do the job.90