Chapter 8: Advances Toward Kokumbona

In November, General Vandegrift had been able to resume the attempt to extend the western line beyond Kokumbona. The 17th Army had been decisively defeated in October, and was unable to mount another counteroffensive until it could receive strong reinforcements. More American troops and planes were soon to be sent to Guadalcanal, and the offensive could be resumed with good prospects of ultimate success.

Operations 1–11 November

Kokumbona Offensive, 1–4 November

The first offensive move was begun before the mid-November naval battle. The objectives were about the same as those of the Marine offensive which opened on 7 October—first, the trail junction and landing beaches at Kokumbona, over 8,000 yards west of the Matanikau, and second, the Poha River, about 2,600 yards beyond Kokumbona. Once the Poha River line had been gained, the Lunga airfields would be safe from enemy artillery fire.

The infantry forces selected for the attack were the 5th Marines, the 2nd Marines (less the 3rd Battalion), and the Whaling Group, which now consisted of the Scout-Sniper Detachment and the 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines. Supporting the offensive were to be the 11th Marines and attached Army artillery battalions, aircraft, engineers, and a boat detachment from the Kukum naval base.

The infantry forces were to attack west in column of regiments on a 1,500-yard front from the Matanikau River, the line of departure. The 5th Marines, closely followed by the 2nd Marines in reserve, would make the assault. The Whaling Group would move out along the high grassy ridges on the left (south) of the assault forces to protect the left flank. Colonel Edson was to command the attacking force. The time for the attack was set for 0630, 1 November.

Full use was to be made of supporting artillery and mortar fire. The 11th Marines and attached battalions were to mass fire first in front of the 5th

Opening the Kokumbona offensive. Col. Merritt A. Edson (seated at desk) discusses plans for the 1 November attacks beyond the Matanikau River

Part of the plan was the construction of fuel-drum pontoon footbriges across the stream, where Marines are seen crossing en route to the front lines

Marines. Artillery and mortar fire were to be placed on each objective and on each ravine and stream approached by the infantry. At least two battalions of artillery were to fire at targets as far west as the Poha, displacing their howitzers forward as the need arose. Aircraft were to strike enemy troop concentrations and artillery positions. Spotting planes for the division artillery would be furnished by the 1st Marine Air Wing.

On the night before the assault, the 1st Engineer Battalion was to construct footbridges across the Matanikau, and an additional bridge suitable for vehicles on the day of the attack. The naval boat detachment was to provide boats for amphibious supply and evacuation as the troops advanced up the coast.1

In preparation for the attack, the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 2nd Marines were brought to Guadalcanal from Tulagi. The 3rd Battalion, which had served as division mobile reserve for six weeks, was sent to Tulagi to rest. The 5th Marines moved to the forward Matanikau position to relieve the 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines, and the 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines; responsibility for the 5th Marines’ old sector in the perimeter defense was assigned to the 2nd Battalion of the 7th Marines. Detachments from the heavy weapons companies of the 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines, and from the 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines, remained in position along the Matanikau to cover the attacking forces as they made the crossing on 1 November. The 2nd Marines (less the 3rd Battalion) meanwhile moved into bivouac east of the Matanikau River.

The engineers salvaged and prepared material for the bridges between 25 and 31 October. On the afternoon of 31 October they hauled the material to the east bank of the river. Early on the morning of 1 November E Company of the 5th Marines crossed the river to outpost the west bank in order to cover the troops constructing the bridges. Between 0100 and 0600, 1 November, A, C, and D Companies of the 1st Engineer Battalion laid three footbridges over the river. Each bridge had a 40-inch-wide treadway which was supported by 2-by-4-inch stringers lashed to a light framework which in turn was lashed to floating fuel drums.

At daybreak on 1 November the 11th Marines, assisted by the 3rd Defense Battalion’s 5-inch guns, fired the preliminary bombardment. The cruisers San Francisco and Helena and the destroyer Sterrett had been sent up by Admiral Halsey, and they shelled the areas west of Point Cruz.2 P-39’s and SBDs from

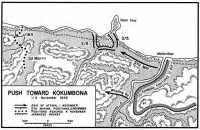

Map 9: Push Toward Kokumbona, 1–4 November 1942

Henderson Field struck Japanese artillery positions, while nineteen B-17’s from Espiritu Santo dropped 335 100-pound bombs on Kokumbona.3

When the artillery fire lifted, the three battalions of the 5th Marines started across the Matanikau bridges. (Map 9) By 0700 the move had been completed successfully, and the 1st and 2nd Battalions, on the right and left respectively, deployed to the attack. Their left was covered by the Whaling Group, which had crossed the river farther upstream. The 1st Battalion of the 5th, advancing over the flat ground along the beach, met the heaviest opposition as the Japanese, yielding ground slowly and reluctantly, fought a delaying action. The 2nd Battalion, moving over higher ground, pushed ahead rapidly and lost contact with the 1st shortly after 1230. The advancing forces halted for the night short of Point Cruz, having gained slightly more than 1,000 yards in the day’s action.

During the day the engineers, using a 10-ton temporary pier, had put a vehicular bridge across the Matanikau about 500 yards from the mouth. Although completed that day the bridge could not be used until the following afternoon, when a new road from the coast road to the bridge was completed.

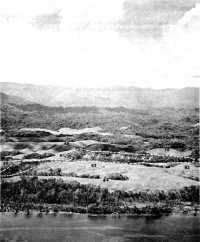

The Point Cruz Trap into which the Japanese were pushed by the advance of 1–4 November, is shown at the top of this vertical aerial photograph. Bridging the Matanikau in the vicinity of the sharp river bend, the 5th Marines moved along the flat coastland north of Hills 78 and 79 while the Whaling Group crossed near Hill 67 and fought westward over the terrain of Hills 73–75

The next morning Colonel Edson committed the reserve 3rd Battalion to assist the 1st Battalion on the right, while the 2nd Battalion, having advanced beyond Point Cruz, turned to the right to envelop the enemy by attacking northward. By 1042 the 2nd Battalion had reached the beach west of the Point and trapped the Japanese who were still opposing the 1st and 3rd Battalions.4

During the afternoon of 2 November the two battalions of the 2nd Marines passed by on the left of the 5th Marines to continue the westward push the next day. On 3 November the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines, and the Whaling Group, which had continued its advance inland, led the assault. The 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines, and, the 1st Battalion, 164th Infantry (Lt. Col. Frank C. Richards commanding), which had been ordered forward from its positions on the Ilu River, were in reserve. Meanwhile the 5th Marines successfully reduced the pocket at Point Cruz; the regiment killed about 350 Japanese and captured twelve 37-mm. guns, one field piece, and thirty-four machine guns. In the final phases of the mop-up the 5th Marines delivered three successful bayonet assaults,5 and drove the surviving Japanese into the sea.6 After the reduction of the pocket the 5th Marines and the Whaling Group were ordered back to the Lunga area, and Colonel Arthur, commanding the 2nd Marines, took over tactical direction of the offensive from Colonel Edson.

The next day the 1st Battalion of the 164th Infantry and the 2nd Marines (less the 3rd Battalion) resumed the advance. By afternoon they had moved forward against the retreating Japanese to a point about 2,000 yards west of Point Cruz, or about 4,000 yards short of Kokumbona. At that point division headquarters halted the advance. Enemy troops had landed east of the perimeter defense, and there could be no further westward movement until the threat had been removed. At 1500 the three battalions dug in at Point Cruz to hold part of the ground they had gained.

Koli Point

Division headquarters had been expecting a Japanese landing in early November at Koli Point east of the Lunga perimeter.7 To forestall the attempt, the 2nd Battalion of the 7th Marines, Lt. Col. H. H. Hanneken commanding, had been ordered out of the Lunga perimeter to make a forced march to the Metapona River, about thirteen miles east of the Lunga. By nightfall of 2 November,

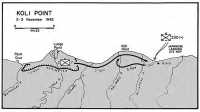

Map 10: Koli Point, 2–3 November 1942

when the 5th Marines had reduced the Point Cruz pocket, the battalion had established defensive positions east of the Metapona’s mouth near the village of Tetere. (Map 10) About 2200 on 2 November the silhouettes of one Japanese cruiser, one transport, and three destroyers appeared offshore in the rainy darkness to land supplies and about 1,500 soldiers8 from the 230th Infantry at Gavaga Creek, about one mile east of Colonel Hanneken’s position. Hyakutake had ordered these troops, with ammunition and provisions for 2,000 men, to land, join Shoji’s force in the vicinity of Koli Point, and build an airfield.9

By the time the Japanese were landing, Colonel Hanneken’s radio communication had failed, and he was unable to inform division headquarters of his situation. The next morning the Japanese force moved west. The Marine battalion engaged the enemy, and was hit by artillery and mortar fire. When one Japanese unit pushed southwest to outflank the marines, the battalion, fighting

as it went, withdrew slowly westward along the coast, crossed the Nalimbiu, and took a stronger position on the west bank. Colonel Hanneken, whose troops were running short of food, attempted to radio information about his situation to division headquarters but was not able to get his message through until 1445.10

When headquarters received Hanneken’s message, arrangements for support and reinforcement were quickly completed. Aircraft from the Lunga airfields bombed and strafed enemy positions, but as no targets were visible from the air results were probably insignificant.11 The cruisers San Francisco and Helena and the destroyers Sterrett and Lansdowne, which had been supporting the Kokumbona attack, sailed eastward to shell Koli Point.12 The 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, with the regimental commander Col. Amor L. Sims, immediately embarked on landing craft to reinforce the 2nd Battalion at Koli Point. (Map VIII.) The 164th Infantry (less the 1st Battalion) was ordered out of its positions along the Ilu to march east to a point about 4,000 yards south of the 7th Marines at Koli Point to be in position to envelop the Japanese left (south) flank.13

General Rupertus, assistant commander of the 1st Marine Division, took command of the Koli Point operation, his first tactical experience on Guadalcanal. On 4 November, the day on which the Kokumbona attack was halted, the Lunga perimeter command was reorganized. General Rupertus was transferred from the relative quiet of Tulagi to Guadalcanal. The Lunga area was divided into two separate sectors, one east of the Lunga and one west of the river. General Rupertus took the east sector. Brig. Gen. Edmund B. Sebree, assistant commander of the Americal Division, who had just landed on the island to prepare for the arrival of the remainder of his division, took the west sector. Both generals reported directly to division headquarters, which thus operated as a small corps headquarters.

On 4 November General Rupertus, and regimental headquarters and the 1st Battalion of the 7th Marines reached Koli Point. The 164th Infantry (less the 1st Battalion) and B Company of the 8th Marines left the Ilu River line at 0600 to march to their objective about seven miles to the east. General Sebree accompanied the 164th to gain close experience with jungle warfare. At the same time, 1st Marine Division headquarters issued orders to the 2nd Raider Battalion,

which had just landed at Aola Bay with the 147th Infantry, to advance overland toward Koli Point to intercept any Japanese detachments moving eastward.

The 164th Infantry progressed slowly on its inland march through swampy jungles and hot stretches of high kunai grass. As there were no inland roads, trucks carried some supplies along the coast to Koli Point, but inland the soldiers of the 164th Infantry, wearing full combat equipment, had to hand-carry all their weapons and ammunition. It was noon before the regiment reached the first assembly area on the west bank of the Nalimbiu River. While regimental headquarters and the 3rd Battalion bivouacked for the night, the 2nd Battalion. advanced northward in column of companies along the west bank of the Nalimbiu. After advancing about 2,000 yards, the 2nd Battalion bivouacked. It had not established contact with the 7th Marines. Patrols had met only a few small Japanese units.

On the following morning, 5 November, General Rupertus ordered the 164th Infantry (less the 1st Battalion) to cross to the east bank of the Nalimbiu, and then to advance north to Koli Point to destroy the Japanese facing the 7th Marines at Koli Point. The 3rd Battalion crossed the flooded Nalimbiu about 3,500 yards south of Koli Point, then swung north to advance along the east bank. Again no large organized enemy force appeared. The battalion advanced against occasional rifle and machine-gun fire. Machine-gun fire halted two platoons of G Company for a time until American artillery and mortar fire silenced the enemy guns. The 2nd Battalion of the 164th Infantry, which had withdrawn to the south from its bivouac positions, followed on the right and rear of the 3rd Battalion.

Action on 6 November was indecisive. The 7th Marines crossed the flooded Nalimbiu with difficulty, while the 164th Infantry’s battalions moved slowly through the jungle. The 3rd Battalion found an abandoned Japanese bivouac about 1,000 yards south of Koli Point, but the enemy had escaped to the east. The 3rd Battalion reached Koli Point at night on 6 November and was followed by the 2nd Battalion the next morning. During the night of 5–6 November the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, mistaking each other for the enemy, exchanged shots.14 Regimental headquarters and the Antitank and E Companies of the 164th Infantry, together with B Company of the 8th Marines, followed a more circuitous route, and reached Koli Point later in the morning.

The combined force then advanced eastward to a point about one mile west

of the wide mouth of the Metapona River. Again there was no enemy resistance, possibly because the Japanese were preparing defenses east of the Metapona to permit the main body to escape.15 The Americans dug in to defend the beach west of the Metapona against an expected landing on the night of 7–8 November, but it failed to materialize. On 8 November the 2nd Battalion of the 164th Infantry was attached to the 7th Marines and placed in reserve. To surround the Japanese, who had dug in along Gavaga Creek at Tetere about one mile east of the Metapona, the three battalions left their positions west of the wide, swampy mouth of the Metapona and advanced to the east and west of Gavaga Creek. The 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, occupied the west bank and took positions running inland from the beach. The 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines, was posted on the east to hold a shorter line between the east bank of Gavaga Creek and the beach. When dengue fever put General Rupertus out of action on 8 November, General Sebree took command on orders from Vandegrift.

With the Japanese force located and surrounded, the size of the American force at Koli Point could be safely reduced. Since General Vandegrift desired to commit a large part of the 164th Infantry to the attack against Kokumbona, regimental headquarters, the Antitank Company, and the 3rd Battalion of the 164th Infantry and B Company of the 8th Marines were brought back to the Lunga perimeter by boat and truck on 9 November.

On that day, at Koli Point, the 2nd Battalion (less E Company) of the 164th Infantry took positions on the right of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines. During the night E Company was committed to the left flank of the 2nd Battalion of the 7th Marines. The Americans now held a curved line from the beach around a horseshoe bend in Gavaga Creek. The Japanese, blocked on the east and west, repeatedly attempted to break out of the trap. They used machine guns, mortars, and hand grenades in their attempts to drive the Americans back. One gap in the American lines remained open in the south, for F and E Companies of the 164th, which were separated by the swampy creek, had failed to make contact. Although wounded seven times by mortar shell fragments, Colonel Puller remained in command of the 1st Battalion of the 7th Marines.

The marines and soldiers, supported by 155-mm. gun batteries, two 75-mm. pack howitzer batteries, and aircraft, began to reduce the pocket. The Japanese resisted vigorously with grenades, mortars, automatic weapons, and small arms. On 10 November F Company of the 164th Infantry attempted to close the gap

and join flanks with E Company. The attempt failed, and the commander of the 2nd Battalion of the 164th was relieved.16 On the next day G Company drove east to close the gap. As the Marine battalions closed in from the east and west, the 2nd Battalion of the 164th Infantry pushed north to reach the beaches in the late afternoon of 11 November. By 12 November the pocket had been entirely cleared. About forty Americans had been killed, 120 wounded; 450 Japanese had been killed.17 The captured materiel included, besides stores of rations and fifty collapsible landing boats, General Kawaguchi’s personal effects.

Hyakutake apparently abandoned the idea of building an airfield near Koli Point, for he ordered Shoji’s troops to return via the inland route to Kokumbona.18 Some of the Japanese had escaped through the gap between the two companies, and some others had apparently withdrawn inland about 7 November. These forces, retreating south and west toward Mount Austen, were harried by Lt. Col. Evans F. Carlson’s 2nd Raider Battalion which had marched west from Aola Bay. The raiders, in a remarkable 30-day march outside the American lines, covered 150 miles, fought 12 separate actions, and killed over 400 enemy soldiers at a cost of only 17 raiders killed before they finally entered the Lunga perimeter on 4 December.19 Of the estimated 1,500 Japanese soldiers who may have landed at Koli Point, probably less than half survived to rejoin the main forces at Mount Austen and the hills to the west,

Resumption of the Kokumbona Offensive

On 10 November, with the trapping of the Japanese at Koli Point, it became possible to renew the westward offensive toward Kokumbona. Under Colonel Arthur’s command, the 1st Battalion of the 164th Infantry, the newly arrived 8th Marines, and the 2nd Marines (less the 3rd Battalion) moved west from Point Cruz on 10 November. Supported by fire from the 1st, A and 5th Battalions of the 11th Marines, the composite force executed a frontal attack on a three-battalion front. The 1st Battalion, 164th Infantry, advanced on the right along the beach; the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines, advanced in the center, and the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines, was echeloned to the left and rear in the attack. On 11 November the advance was resumed against rifle, machine-gun, and mortar fire. By noon the troops had fought their way to a point slightly beyond that which they had reached on 4 November.

Carlson’s Raiders, landing at Aola Bay the morning of 4 November, moved toward Koli Point to intercept Japanese forces which had come ashore east of the Lunga perimeter. Enemy positions were beyond Taivu Point, seen on the far horizon

Japanese collapsible landing boats of the type shown in this picture taken later in the Guadalcanal campaign, were part of the materiel captured at Koli Point. With the stern section removed, the boat’s sides can be compressed as the rubber bottom folds

The Japanese were grimly determined to prevent the Americans from taking Kokumbona. This village was the site of the 17th Army command post, and also the terminus of the main supply trail to the positions which the Japanese were secretly preparing on Mount Austen. Accordingly Hyakutake assigned the mission of halting the American attack to a new general, Maj. Gen. Takeo Ito, Infantry Group commander of the 38th Division and a veteran of the fighting in China. Ito had landed at Tassafaronga from a destroyer on 5 November to take command of a reserve force of 5,000 men. Believing that the American front west of Point Cruz was so narrow that he could easily outflank it, he moved his force to a concealed position in the jungled hills on the left flank of the Americans, about 5,000 yards south of the beach. From this point he planned to strike the American left flank and rear.20

Before Ito could attack, and before the Americans were even aware that their left was in danger, Vandegrift was once more forced to halt the offensive when he received word that the Japanese were preparing to bring large troop convoys to Guadalcanal in mid-November. To meet the threat of another counteroffensive, all troops were needed within the Lunga perimeter.

The battalions disengaged; the 2nd and 8th Marines retired toward the Matanikau, covered by the 1st Battalion of the 164th Infantry. The marines recrossed the Matanikau on 11 November, followed next day by the Army battalion. The entire 164th Infantry, having returned from its operations across the Matanikau and Metapona Rivers, went into division reserve. Once safely across the Matanikau, the Americans destroyed the bridges and held their lines while the air and naval forces fought desperately to keep the Japanese away.

Push Toward the Poha

As a result of the naval victory in mid-November and the arrival of the 182nd Infantry, commanded by Col. Daniel W. Hogan, the offensive toward Kokumbona and the Poha Rivers was resumed. The 1st Marine Division headquarters, which ordered the attack, placed General Sebree, commander of the western sector, in tactical command. Available troops in the west sector included the 164th Infantry, the 8th Marines, and the two battalions of the 182nd Infantry. To support operations in any direction, all artillery battalions remained grouped within the perimeter under del Valle’s command.

General Sebree planned first to gain a line of departure far enough west of the Matanikau and far enough south of the beach to provide sufficient room for the regiments to maneuver. Once the line of departure had been gained, a full-scale offensive could be opened. The line which General Sebree planned to capture first ran about 2,500 yards inland from Point Cruz to the southernmost point (Hill 66) of a 1,700-yard-long ridge (Hills 66–81–80).

It was thought that the west bank of the Matanikau was not occupied by the Japanese during the second week of November. This belief was confirmed by infantry and aerial reconnaissance patrols, and General Sebree and Colonel Whaling of the Marines personally patrolled the ground as far west as Point Cruz without meeting any Japanese.

Once the line of departure had been gained, the assault units were to move west, followed by the 1st Marines on the inland flank. The latter regiment was to turn northward to envelop any Japanese pockets as the 5th Marines had done so successfully earlier in the month, while the assault units continued to advance westward. This part of the plan was canceled when the 1st Marine Division was alerted for departure from Guadalcanal.21

The 2nd Battalion of the 182nd Infantry was to cross the Matanikau on 18 November to seize Hill 66, the highest ground north of the northwest Matanikau fork, and the 1st Battalion of the 182nd Infantry would advance across the river and west to Point Cruz the next day. As the American forces which had withdrawn on 11–12 November had destroyed all the Matanikau. bridges, engineers were to bridge the river, improve the coast road, and build a trail over the ridges to Hill 66.

The terrain west of the Matanikau differs from the deep jungles of the inland areas. The coast is flat and sandy. South of the beach rocky ridges, covered with brush and coarse grass, thrust upward to heights of several hundred feet. These ridges, running from north to south, rise near the beach and increase in height toward the south. Between these steep ridges are deep, jungled ravines which the Japanese could exploit to good advantage. The ridge line formed by Hills 80, 81, and 66 faces northwest and turns sharply eastward at Hill 66 toward the Matanikau River’s main stream. It is separated from the high hills on the south by the valley cut by the northwest Matanikau fork.

Unknown to the Americans, the 17th Army had also been planning for local offensive action. While the shattered 2nd Division assembled near Kokumbona,

the 38th Division had been ordered to advance east from Kokumbona, cross the Matanikau, and seize the high ground on the east bank for artillery positions and as a line of departure for another assault against the Lunga airfields. At the same time troops under Ito’s command had been ordered to occupy Mount Austen.22

On 18 November the 2nd Battalion of the 182nd Infantry (Lt. Col. Bernard B. Twombley commanding), covered by the 8th Marines on the east bank of the Matanikau, crossed a footbridge about 700 yards from the Matanikau’s mouth to seize Hill 66. (Map IX) The battalion climbed to the top of the first ridge on the west bank (Hill 75) and advanced southwest behind the ridge crest toward Hill 66, about 2,000 yards from Hill 75. There were no Japanese on the ridges, but the inexperienced battalion made slow progress. The men, having landed only six days before, were not yet accustomed to the moist heat. Since landing, most of them had been unloading ships and moving their supplies. They carried full loads of ammunition, water, and food. Many who had not swallowed salt tablets collapsed, exhausted from the hard climb. The 2nd Battalion did not reach Hill 66 until noon.23 Having taken the objective, the men dug foxholes and gun emplacements on the west and south military crests of Hill 66. On the left was G Company, and F on the right. Battalion reserve consisted of E Company, and H Company put its mortars in a gully behind the battalion command post.24

In the afternoon a detail of two officers and thirty enlisted men from G Company went into the valley on the south to fill canteens at a water hole. They reached the spring safely, but failed to post sentries as they filled the clanking canteens. As one man in the group glanced up, he saw a Japanese officer and about twenty soldiers deploying in the jungle near by. The Japanese promptly opened fire. The water detail scattered, each man taking cover as best he could. When a rescue party from the 2nd Battalion later made its way to the spring, the enemy patrol withdrew and the water party straggled back to the crest of Hill 66. One officer and one enlisted man had been killed.25 There were no more encounters with the Japanese that day.

The 1st Battalion of the 182nd Infantry, commanded by Lt. Col. Francis F.

MacGowan, crossed the Matanikau the next morning (19 November). The battalion advanced along the flat ground between the northernmost hills and the beach, while B Company of the 8th Marines, acting on Sebree’s orders, advanced over the most northerly hill (Hill 78) to cover the battalion’s left flank. About 400 yards west of the river the battalion met fire from small enemy groups, but there was no heavy fighting. The battalion moved slowly and cautiously, fighting a series of skirmishes as it moved toward Point Cruz.26

B Company of the 8th Marines also met enemy fire west of Point Cruz and withdrew to the vicinity of Hill 78 to take cover. The company again attempted to advance, but could not gain ground.27 About noon Colonel MacGowan’s battalion halted just east of Point Cruz; it dug in along a 700-yard line from the beach east of the point to the west tip of Hill 78, refusing the left flank eastward a short distance along the south slopes of the hill. The Marine company then withdrew across the Matanikau to rejoin its regiment. The 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 182nd Infantry were then separated by a gap of over 1,000 yards.

Japanese troops had been secretly moving east from Kokumbona.28 These forces took positions west of the 1st Battalion during the night of 19–20 November, while artillery and mortars fired on the American lines. About dawn on 20 November part of this force struck suddenly at the 1st Battalion’s left flank. The troops holding high ground on the battalion’s left held their line, but as the attack developed along the 1st Battalion’s line the troops on the low ground fell back about 400 yards. General Sebree, Lt. Col. Paul A. Gavan, the operations officer, and Lt. Col. Paul Daly, the assistant intelligence officer, of the Americal Division, came forward and found the battalion “somewhat shaken.” They halted the withdrawal and reorganized the companies.29

Planes and artillery then struck at the Japanese, who had not exploited their advantage by advancing east of Point Cruz, and the 1st Battalion again moved west and by 0900 had regained its position.30

C and A Companies of the 182nd attacked west after the recapture of the initial line and advanced to the beach just west of Point Cruz. There the attack stalled after the companies had been hit hard by Japanese artillery and mortar

fire. There was “considerable confusion and some straggling” in the 182nd Infantry, and it was only after order had been restored that the 1st Battalion organized a disciplined firing line.31 The Japanese retained Point Cruz itself.

By afternoon on 20 November it had become obvious that more American troops were needed west of the Matanikau. The Japanese were known to be moving more troops forward into the engagement.32 General Sebree therefore ordered the more experienced 164th Infantry out of reserve to fill the gap between the two battalions of the 182nd Infantry. The 164th Infantry was to enter the line under cover of darkness and attack the next morning. The 1st Battalion of the 164th Infantry entered the line on the left of the 1st Battalion of the 182nd Infantry, and the 3rd Battalion of the 164th moved in between the 2nd Battalion, 182nd Infantry, and the 1st Battalion, 164th. Each battalion of the 164th took over about 500 yards of the line, and the 182nd Infantry battalions, on either side of the 164th Infantry, extended their flanks to join with those of the 164th.

During the first three days of the operation supplies for the units west of the Matanikau had been carried forward by hand from the river line. The engineers finally succeeded in building a footbridge over the flooded Matanikau, but the bridge for heavy vehicles was not completed until 21 November.33

The 1st Battalion of the 182nd attacked west from the Point Cruz area on 21 November. It met heavy artillery and mortar fire, as well as small-arms fire from some Japanese entrenched on Point Cruz itself, the beach on the west, and the near-by hills and ravines. The battalion reduced Point Cruz, but failed to advance west.34

The battalions of the 164th Infantry also attacked to the west on 21 November from the Hill 80–81 ridge line. A ravine about 200 feet deep, varying in width from 150 to 300 feet, lay directly in front of Hills 80 and 81. A series of steep ridges (Hills 83 and 82) lay west of the ravine. To get through the ravine and gain the ridges on the west, it would be necessary for the 164th Infantry to cross about fifty yards of open ground on the ridge. Between 11 and 18 November the Japanese had built strong positions, containing a large number of automatic weapons, in the hills and ravines and on the flat ground west of Point Cruz. The hill positions, well dug in on the reverse slopes, were defiladed

The ravine in front of Hills 80–81, where the 164th Infantry attacks stalled on 23 November, was well defended by Japanese dug into defiladed positions in Hills 83 and 82. American troops were halted on the line of Hills 66, 81, 80

from American artillery and mortar fire. Machine guns sited at the head of each ravine could put flanking fire into advancing troops. The ravine in front of Hills 81–80 was especially well defended. On the flat ground in places where a thin layer of earth covered a coral shelf, the Japanese had dug shallow pits with overhead cover, as well as foxholes under logs and behind trees. These positions, organized in depth, were mutually supporting. Small arms supported the automatic weapons, and artillery and mortars could cover the entire American front.35

Japanese fire quickly halted the 164th Infantry after it had made an average gain of less than forty yards. The 182nd and 164th Regiments attacked again on 22 November but failed to make progress. In the afternoon the 8th Marines was notified that it was to pass through the 164th Infantry the next day to attack toward Hill 83.

After the infantry had withdrawn 300 yards behind the front lines early on 23 November, the 245th Field Artillery Battalion and L Battery and the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 11th Marines fired a 30-minute concentration on the Japanese lines. The 8th Marines then passed through the 164th Infantry and delivered successive attacks against the Japanese throughout the day. The regiment was supported by the artillery which fired 2,628 rounds of all calibers.36 During the bombardment, Hyakutake and the 17th Army chief of staff were slightly injured at their command post near Kokumbona.37 The American forces failed to gain. The Japanese, defending vigorously, put fire all along the entire American lines. The 3rd Battalion of the 164th Infantry was hit by accurate fire. In the afternoon Of 23 November mortar fire struck the command posts of L, 1, and K Companies, and killed the battalion surgeon, four lieutenants, and one 1st sergeant.38

American headquarters concluded that “further advance would not be possible without accepting casualties in numbers to preclude the advisability of [continuing] this action.”39 The troops were ordered to dig in to hold the Hill 66–80–81-Point Cruz line. The attack had ended in a stalemate.

Operations up to 23 November had demonstrated that frontal assault would be costly. By 25 November less than 2,000 men of the 164th Infantry were fit

for combat. Between 19 and 25 November 117 of the 164th had been killed, and 208 had been wounded. Three hundred and twenty-five had been evacuated from the island because of wounds or illness, and 300 more men, rendered ineffective by wounds, malaria, dysentery, or neuroses, were kept in the rear areas.40 The 1st Marine Division was soon to be relieved, and its impending departure would reduce American troop strength too greatly to permit the execution of any flanking movements over the hills south of Hill 66. Until reinforcements could be brought in, the westward offensive had to be suspended.

The attacks on 18–23 November had, however, achieved some success. Hyakutake’s plan to recapture the Matanikau’s east bank had been thwarted, although in November he secretly began to increase his strength on Mount Austen.41 American troops had finally established permanent positions west of the Matanikau. The Americans and the Japanese now faced one another at close ranges, the Americans on high ground, the Japanese on reverse slopes and in ravines. Each side could cover the opponent’s lines with rifle, automatic, mortar, and artillery fire, and put mortar and artillery fire on the trails and rear areas. Americans and Japanese were to hold these static but dangerous lines until the beginning of the XIV Corps’ general offensive in January.