Chapter 11: XIV Corps’ First January Offensive: The West Front

General Patch, it will be remembered, had ordered the attack against Mount Austen in December as a preliminary to a large offensive in January. Once the 132nd Infantry had taken Hill 27 and encircled the east portion of the Gifu, it became possible for troops to operate over the hills west of Mount Austen in a drive, beginning on 10 January 1943, which was designed to destroy the Japanese or drive them from Guadalcanal.

Except for the attacks against Mount Austen, the American lines in the west sector had not changed substantially since November. The west line, running south from Point Cruz, was refused eastward at Hill 66, and joined the old perimeter defense line at the Matanikau River. South of the perimeter defense the 132nd Infantry was facing the Gifu garrison between Hills 31 and 27 on Mount Austen.

In late December General Patch had ordered the west sector extended to provide more maneuver room for the projected January offensive, and to ensure the unhindered construction of a supply road west of the Matanikau.1 The Americal Division’s Reconnaissance Squadron had seized Hill 56—an isolated eminence about 600 yards southeast of Hill 66—against scattered opposition, while the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines, had taken Hills 55 and 54 west of the Matanikau. There are no ridges connecting Hills 56 and 66, or 56 with 55. The troops did not hold a continuous line, but patrols covered the deep canyons between the hills.

The supply road in question was an extension of Marine Trail, a track which led from the coast road southward along the east bank of the Matanikau to Hill 49. By 5 January Americal Division engineers had built a motor bridge across the Matanikau at the foot of Hill 65. Bulldozing the road, they had reached the 900-foot summit of Hill 55 by 9 January.

By the first week of January 1943, the divisions of the XIV Corps, it will be recalled, numbered over 40,000 men, as compared with less than 25,000 Of the Japanese 17th Army on Guadalcanal. All three combat teams of Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins’ 25th Division had landed on Guadalcanal between 17 December 1942 and 4 January 1943, and bivouacked east of the Lunga River. Headquarters of the 2nd Marine Division and the reinforced 6th Marines, Col. Gilder T. Jackson commanding, had reached Guadalcanal on 4 January to join the rest of the division. Brig. Gen. Alphonse De Carre, the assistant division commander, led the 2nd Marine Division on Guadalcanal.2

Although the XIV Corps’ troop strength and materiel sufficed for an offensive, the transportation of supplies to the front prior to and after 10 January was difficult. Poor roads and lack of sufficient motor transport slowed the movement of supplies to all units. Only the indispensable, rugged $frac14;-ton truck (jeep) could negotiate the rough corduroy trails and steep hills of the southern sector. The 25th Division’s infantry units, operating in that area, were to depend almost entirely upon jeeps and hand-carriers for ammunition, food, water, and for evacuation. The supply of the 2nd Marine Division was easier over the coast road and lateral trails.

At the start of the January offensives the Japanese positions west of the Matanikau were substantially the same as in December. The enemy had concentrated considerable strength between Point Cruz and Kokumbona. He did not hold a continuous line on the uphill flank but rather a series of strong points with patrols and riflemen covering the areas between. In the coastal sector the enemy continued to employ the north-south ravines to good advantage. By placing machine guns at the head of a draw the Japanese could enfilade with flanking fire any troops attempting to advance west. Thus a few Japanese could delay or halt hundreds of Americans. American headquarters believed that the Japanese held strongly the high ground south of Hill 66 and west of the Matanikau.3 In the Gifu on Mount Austen soldiers from the 124th and 228th Infantry Regiments continued to resist and some elements of the same regiments, supported by artillery and mortars, were occupying areas to the west.

General Patch explained his plan for the first offensive in a letter to General Collins dated 5 January 1943. (Appendix B) He ordered the 25th Division,

then east of the Lunga River, to relieve the 132nd Infantry on Mount Austen without delay and to seize and hold a line approximately 3,000 yards west of Mount Austen. (Map XIII) The 2nd Marine Division was to maintain contact with the right flank of the 25th Division, which would provide for the security of its own left flank. General Patch gave General Collins the authority to deal directly with the 2nd Marine Air Wing commander in securing close air support.

General Patch ordered the Americal Division Artillery and one recently arrived 155-mm. howitzer battery and one 155-mm. gun battery of the Corps Artillery to support the 2nd Marine Division’s advance along the coast and to be prepared to reinforce the 25th Division Artillery. The 75-mm. pack howitzers of the 2nd Battalion, 10th Marines, were to support the 25th Division Artillery.4 The Americal Division was to hold the perimeter defense from 9 to 26 January. Only its artillery, the Reconnaissance Squadron, the 182nd Infantry, and the 2nd Battalion of the 132nd Infantry were to take part in the XIV Corps’ January offensives.

Capture of the Galloping Horse

The 25th Division’s Preparations

The offensive in January was to be General Collins’ first combat experience. Graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in 1917 at the age of twenty, he had been sent to Germany to serve with the Army of Occupation in 1919. From 1921 to 1931 he attended and instructed in various Army schools, and was graduated from the Command and General Staff School in 1933. After a tour of duty in the Philippines, he was graduated from the Army Industrial and War Colleges. He taught at the War College for two years, served for several months with the War Department General Staff, and in 1941 became Chief of Staff of the VII corps, an organization which he was to command in the European Theater of Operations during 1944 and 1945. Immediately after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Collins became Chief of Staff of the Hawaiian Department and in May 1942 he was made a major general and given the command of the 25th Division.

Upon receipt of General Patch’s orders, the 25th Division made preparations

The first January offensive zone was west of the Matanikau and Army fighting was concentrated in the area of Hills 54, 55, 56

From Hill 42 on Mount Austen’s northwest slopes, the sector could be seen clearly by 25th Division troops resting before the offensive started

for the attack. Patrols examined all ground which could be covered on foot. General Collins, Brig. Gen. John R. Hodge, the assistant division commander, Brig. Gen. Stanley E. Reinhart, the artillery commander, staff officers, all regimental commanders, and most battalion commanders flew over the division’s zone of action. Air photographs and observation gave a good view of the open country, but jungle obscured the canyons, valleys, and ravines.

Intelligence officers of the 25th Division had little information on the enemy’s strength and dispositions in the division’s zone, but they did know that the Japanese were defending a series of strong points and that they held the Gifu and the high ground south of Hill 66 in strength.5

In the absence of complete information about the enemy’s dispositions, terrain largely dictated the 25th Division’s plan.6 General Patch did not assign a southern boundary to the 25th Division, but the Lunga River would limit its movements south of Mount Austen. The northern divisional boundary ran along the northwest Matanikau fork. The Matanikau forks divided the 25th Division’s zone into three almost separate areas: the area east of the Matanikau where the Gifu strong point was located; the open hills west of the Gifu between the south and southwest Matanikau forks; and the open hills south of the Hill 66 line between the northwest and southwest Matanikau forks.

General Collins issued Field Order No. 1 to the 25th Division on 8 January 1943.7 With the 3rd Battalion of the 182nd Infantry, the Americal Division Reconnaissance Squadron, and the 1st Battalion of the 2nd Marines attached,8 the 25th Division was to attack at 0635, 10 January. It was to seize and hold the assigned line about 3,000 yards west of Mount Austen—a line running generally south from the Hill 66 positions taken in November 1942. To the 35th Infantry, a Regular Army regiment commanded by Col. Robert B. McClure, were attached the 25th Division Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop and the 3rd Battalion, 182nd Infantry. Colonel McClure’s troops were to relieve the 132nd Infantry at the Gifu, take the high ground west of the Gifu, and attack west to seize and hold the division objective in the 35th Infantry’s zone, a line about 3,000 yards west of Mount Austen. The 27th Infantry, a Regular Army regiment commanded by Col. William A. McCulloch, was ordered to capture the high

ground between the northwest and southwest Matanikau forks. Col. Clarence A. Orndorff’s 161st Infantry (less the 1st Battalion), formerly of the Washington State National Guard, was to be in division reserve.

Divisional artillery battalions were to fire a 30-minute preparation on 10 January, from 0550 to 0620, on the water hole near Hill 66 and the hills to the south in the 27th Infantry’s zone. Artillery preparation and aerial bombardment were to be omitted in the 35th Infantry’s zone to avoid warning the Japanese of the effort against their south flank.

The 8th Field Artillery Battalion (105-mm. howitzers) was to give direct support to the 27th Infantry. Directly supporting the 35th Infantry would be the 105-mm. howitzers of the 64th Field Artillery Battalion. The 89th (105-mm. howitzers) and the 90th (155-mm. howitzers) Field Artillery Battalions, and the 2nd Battalion, 10th Marines, were originally assigned to general support. When General Collins later committed the 161st Infantry to mopping up actions, the 89th supported that regiment. The 75-mm. pack howitzers of the 2nd Battalion, 10th Marines, were to support the fires of the 8th Field Artillery Battalion as a secondary mission, for the open terrain of the 27th Infantry’s zone would permit profitable use of light artillery. On 10 January the 155-mm. howitzers of the Americal Division’s 221st Field Artillery Battalion also supported the 25th Division’s artillery.

The enemy’s deficiency in artillery and air power simplified the problem of selecting forward artillery positions west of the Lunga River. Since defilade, camouflage, and concealment were not necessary, the artillerymen were able to emplace their guns on the forward slopes of hills with impunity.9 All battalions prepared to move their howitzers from east of the Lunga to positions far enough west to be able to fire into Kokumbona. The 64th Field Artillery Battalion, supporting the 35th Infantry, selected positions on Mount Austen’s foothills—the slopes of Hills 34 and 37, about 2,000 yards northeast of the Gifu and 9,000 yards southeast of Kokumbona. The 8th Field Artillery Battalion, supporting the 27th Infantry, selected positions on Hills 60, 61, and 62, south of the 64th and about 3,000 yards east of the easternmost hill in the 27th Infantry’s zone. The 89th Field Artillery Battalion decided on Hill 49, a high bluff east of the Matanikau River. The 90th Field Artillery Battalion selected positions about 1,000 yards east of the junction of Wright and the coastal roads.10

Rough ground and insufficient motor transport complicated the movement

Casualty movement taxed the facilities of medical units during the January offensive. The jeep, only vehicle able to negotiate the poor roads, was used as above to carry patients to hospitals

Men were brought out of the front lines by hand-carry teams

of weapons, spare parts, ammunition, rations, and water. Every battalion initially hauled two units of fire from the ammunition dump near the Ilu River to its battle position, a distance of over ten miles for each battalion. Two units of fire for the 105’s weigh 135 tons, or fifty-four 2½-ton truckloads. Each 105-mm. battalion possessed but five 2½-ton trucks. The 90th’s heavy transport originally consisted of only ten 4-ton trucks. In addition each battalion had but five jeeps, two ¾-ton weapons carriers, and four 1-ton trailers.11 By borrowing six 2½-ton trucks from the Americal Division and driving all vehicles day and night, the artillery battalions were able to put their howitzers into their positions and haul enough ammunition to support the projected offensive by 8 January.12 With their howitzers in place, the artillery battalions established check points and registered fire on prospective targets.

Air officers worked directly with General Collins and the 25th Division staff in planning air support. As some of the Japanese positions were defiladed from artillery fire, dive bombers and fighter-bombers were needed. SBDs were to drop 325-pound depth charges and P-39’s; 500-Pound demolition bombs, on the defiladed positions.13

The 25th Medical Battalion solved the problem of evacuation from Mount Austen and the hills to the west in the same manner as had the 101st in December 1942. Engineers and medical troops strung cableways across canyons, rigged skids on light Navy litters so that they could slide, and later used a boat line on the Matanikau to evacuate wounded. Carrying litters up and down steep slopes exhausted litter-bearers so quickly that litter squads were enlarged from the usual four to six, eight, and even twelve men.14 Converted jeeps were used as ambulances on the roads and trails.

H Hour for the 25th Division was set at 0635, 10 January 1943. This attack, the most extensive American ground operation on Guadalcanal since the landing, was to open the final drive up the north coast. To make the offensive a success, the 25th Division had to carry out two missions: reduce the Gifu strong point, thus eliminating the last organized bodies of enemy troops east of the Matanikau; and capture the high ground south of the Point Cruz–Hill 66 line, thus beginning the envelopment of the Point Cruz-Kokumbona area and extending

the western American lines far enough inland to make the forthcoming western advance a clean sweep.

27th Infantry’s Preparations

In the 27th Infantry’s zone, the 900-foot-high hill mass formed by Hills 55–54–50–51–52–57–53, called the Galloping Horse from its appearance in an aerial photograph, dominated the Point Cruz area to the north. (Map XIV) The distance from Hill 53, the “head” of the Galloping Horse, to Hill 66 is about 1,500 yards. Hill 50, the “tail,” lies about 2,000 yards northeast of Hill 53. The Horse is isolated on three sides:15 the Matanikau River’s main stream separates it on the east from the high ground north of Mount Austen; the southwest fork of the Matanikau cuts it off from the hills on the south; and the northwest Matanikau fork flows between the Galloping Horse and the hills on the north. The heavy jungles lying along the river forks also help to isolate the hill mass. The southern slopes of the Horse’s back and head—Hills 51, 52, and 53—are almost perpendicular, and Hills 50 and 55 are nearly as steep. The hills are open, with only a few scattered trees. The main vegetation consists of high, dense, tough grass and brush.

XIV Corps headquarters believed that the enemy’s hold on the Galloping Horse was strong and that he would vigorously oppose the attack in this zone.16 Throughout December 1942 and January 1943, patrols from the 2nd Marines and the Americal Division’s Mobile Combat Reconnaissance Squadron had met heavy enemy rifle, machine-gun, and mortar fire from the vicinity of Hill 52. The enemy troops, including elements of the 228th and 230th Infantry Regiments of the 38th Division, also held a series of strong points along the banks of the southwest Matanikau fork south of the Galloping Horse.

Colonel McCulloch, commanding the 27th Infantry, determined to attack south across the 2,000-yard front of the Galloping Horse with two battalions supported by sections of the 27th Infantry’s Cannon Company. Believing that the jeep trail from the Matanikau up to the summit of Hill 55 was not adequate for the delivery of supplies to two battalions attacking abreast, he decided to attack from two separate points. He ordered Lt. Col. Claude E. Jurney’s 1st Battalion to attack on the right (west) against Hill 57 (the forelegs) from Hill 66 in the 2nd Marine Division’s zone. The battalion was to advance south of Hill 66 across the northwest Matanikau fork, to seize the water hole where the 182nd Infantry’s detail had been ambushed on 18 November, and to take the

Corps’ objective in its zone, the north part of Hill 57. F Company of the 8th Marines and the Americal Division’s Reconnaissance Squadron were to provide flank security for the 1st Battalion. Colonel Jurney’s battalion was to be supplied over the more convenient Hill 66 route. Twenty-five men from each company of the 1st Battalion were to carry supplies forward from Hill 66.

The 3rd Battalion, Lt. Col. George E. Bush commanding, was to advance on the left in a wide enveloping movement. Colonel Bush’s troops were to assemble behind the 2nd Marines’ lines on Hill 55, and then advance south along the Galloping Horse’s hind legs and attack generally southwest to take Hill 53, the Corps’ objective in the 3rd Battalion zone. Supplies for the 3rd Battalion were to be brought from the coast road along Marine Trail, across the Matanikau, and up the jeep trail to Hill 55, from where they would be hand-carried by seventy-five natives escorted by soldiers of the Antitank Company. The assault battalions were to reach their lines of departure from the coast road.

Lt. Col. Herbert V. Mitchell’s 2nd Battalion was to be initially in regimental reserve in assembly areas at the base of Hill 55.17 The 1st Battalion of the 161st Infantry, Lt. Col. Louie C. Aston commanding, was attached to the 27th Infantry for this action to block the southwest Matanikau fork between Hill 50 and the high ground to the south, and to assist in holding a defense line along Hills 50 and 51 after their capture. General Collins warned Colonel McCulloch that, if the 35th Infantry encountered difficulty in taking its objective to the south, the 27th might have to come to its assistance from the Hill 51–52 area before moving west to take Hill 53.

The First Day: 1st Battalion Operations

Artillery preparation for the attack on the Galloping Horse began at 0550, 10 January, when the 25th Division artillery fired a heavy concentration on the water hole near Hill 66 and on the Galloping Horse’s forelegs. In thirty minutes 5,700 rounds were fired by six field artillery battalions-the 8th, 64th, 89th, and 90th from the 25th Division; the 2nd Battalion, 10th Marines; and the 221st from the Americal Division. Fire was controlled by the 25th Division’s fire direction center. The 105-mm. howitzers fired 3,308 rounds; 155’s fired 98; 75’s fired 1,874. The total weight of the projectiles was 99½ tons.18

To make all initial rounds hit their targets simultaneously, the artillery employed time-on-target fire. This technique, which the 25th Division had

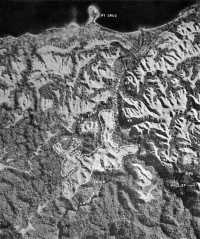

The Galloping Horse. This vertical photograph was taken from about 12,000 feet

rehearsed in previous training, invariably caused carnage among troops caught in the open, for they were not warned to take cover by the shells from the nearest battery landing shortly before the main concentration. The artillery fired at irregular intervals, hoping that the enemy troops who had survived the first blasts would believe the shelling to be over and expose themselves during lulls to the next volleys.

This time-on-target (TOT) “shoot” was the first divisional TOT firing of the Guadalcanal campaign, and may have been the first divisional combat TOT firing by American artillerymen during World War II.19 The fire devastated the vicinity of the water hole. It was so effective that when the 1st Battalion attacked south against its objective over a route known to have been formerly strongly held by the enemy, it encountered only minor opposition.

As steep cliffs masked some of the enemy positions on the Horse from artillery shells, aircraft from the 2nd Marine Air Wing then struck at the positions on the reverse slopes. At 0620, when the artillery fire ceased, twelve P-39’s and an equal number of dive bombers (SBDs) flew over to strike at the Japanese. Each P-39 carried one 500-pound bomb, and each dive bomber carried three 325-pound depth charges.20 The artillery had laid a smoke line from the southwest tip of Hill 66 to the Horse’s left (east) foreleg. No plane was to bomb east of the smoke line. But just before the attacking aircraft reached the target area, a quantity of ammunition blew up on Hill 56. It had been struck either by a short American shell or by an accurate round from the enemy’s artillery. The leading bomber, apparently misled by the smoke from the exploding ammunition, dropped a depth charge on the 8th Marines on Hill 66, and the second bombed Hill 55 east of the smoke line. Fortunately no marines or soldiers were hurt.21

Success of the 1st Battalion’s attack south from Hill 66 against Hill 57 on 10 January depended partly upon the security of its flanks while it crossed the northwest Matanikau fork in the ravine between Hills 66 and 57. After the bombardment F Company of the 8th Marines moved to the southwest corner of Hill 66 to be in position to tie the 2nd Marine Division’s left flank to the point where the 25th Division’s right flank would be when it had reached its objective.

By 0742 the Marine company was in place. B Company of Colonel Jurney’s battalion left Hill 66 at 0735 to seize the water hole. F (8th Marines) and B Companies then joined their flanks, thus assuring the security of the 1st Battalion’s right flank.

The Americal Division’s Mobile Combat Reconnaissance Squadron had the mission of protecting the left flank of Colonel Jurney’s battalion by blocking the ravine between Hill 56 and the Horse’s left (east) foreleg. Soldiers of the squadron reached the ravine and set up a block by 0830. An hour and a half later B and A Companies of the 27th Infantry made contact with the squadron.22

While its flanks were being secured, the 1st Battalion moved off Hill 66 in column of companies, with A Company leading, followed by C and D. Progress was rapid; the terrain offered more resistance than the Japanese. The TOT concentration had prevented any vigorous enemy resistance, and only three machine guns fired at the 1st Battalion. By 1027 A Company had crossed the river fork, and by 1140 the entire battalion had reached its objective on Hill 57.23 Colonel Jurney’s men organized their positions on Hill 57 and fired in support of the 3rd Battalion’s advance against Hill 52. In the afternoon Colonel Jurney sent out a patrol which reached Hill 52 after dark to establish contact with the 3rd Battalion.

The First Day: 3rd Battalion Operations

In its zone the 3rd Battalion was to have a harder and longer fight. There the terrain, though open, is extremely rough. The thick woods in the valleys extend along the north side of the zone for 1,500 yards between the Horse’s hind legs and forelegs. The Horse’s body, formed by an open area 600 yards across from north to south, is cut by hills and ravines. Waist-high grass and broken ground in this area provided cover for advancing troops. South along the Horse’s body the precipitous, almost perpendicular slopes leading to the jungled gorge of the southwest Matanikau fork made troop movements in that direction almost impossible. Hill 52 in the middle dominates the neighboring hills. Between Hills 52 and 53 are two smaller hills, invisible from the ground east of Hill 52, which the 25th Division later called Exton and Sims Ridges after two 2nd Battalion lieutenants who were killed on 12 January.

Because it dominated the surrounding area, Hill 52 was an intermediate objective for the 3rd Battalion in its attack toward Hill 53. It was a naturally strong position that a few troops could easily hold. Its level crest dominated

the approaches from the east and north, and the steep palisades on the south blocked any flanking movements from that side. Sheer drops on the west and south protected the defenders from American fire. Marine and Reconnaissance Squadron patrols had previously approached Hill 52 and reported it to be a “hornet’s nest.”24 Although the area to the east had been scouted, no patrols had been able to push west of Hill 52 prior to 10 January. The 27th Infantry’s information about the terrain west of Hill 52 had been derived from aerial reconnaissance and photographs.

Colonel Bush, commanding the 3rd Battalion, planned to move south from Hill 55 to take Hills 50 and 51, and then to attack west to seize Hills 52 and 53. Since Hill 52 was too formidable to be taken by frontal assault, he hoped to take it by a double envelopment from the south and north, L Company on the left (south) and I on the right (north), and K in battalion reserve. To each assault company he attached a machine gun platoon from M Company. Two 37-mm. guns from the Antitank Platoon of Battalion Headquarters Company, plus M Company’s 81-mm. mortar platoon, were to constitute the base of fire on Hill 54, which was also the site of the battalion command post. Hill 52 had not been a target for the preparatory aerial and artillery bombardments, although the artillery had registered on the crest. The 8th and other supporting battalions were to fire on call to support the 3rd Battalion’s attack.

The 3rd Battalion left its assembly area at the foot of Hill 55 at 0300, 10 January. By 0610 the battalion had climbed Hill 55 and reached its line of departure on the north slopes. At H Hour, 0635, the battalion moved southward through the Marine lines in column of companies to deploy for the attack. By 0646 the troops were moving down the forward slopes of Hill 54 toward Hills 50 and 51. L Company captured Hill 51 without opposition and there established a base of fire. One platoon covered the company’s left and rear; another platoon was held in support. Capt. Oliver A. Roholt, the company commander, sent the 1st Platoon to attack the southeast corner of Hill 52. Protected by the uneven ground and high grass, the platoon advanced rapidly and aggressively and by 0700 was halfway up the east slope.25 As the soldiers prepared to assault the crest, Japanese machine-gun and mortar fire f rom their front and left flank forced them to halt. Captain Roholt, on Hill 51, did not believe that the platoon could outflank the enemy position, for mutually supporting

Japanese riflemen and machine gunners could cover all approaches from the east and north, and the steep precipice on the south would prevent the platoon from approaching the Japanese right flank or rear. The platoon had actually attacked along the front of the enemy line, and had thus exposed its own left flank to the enemy.

Colonel Bush had planned to call for artillery fire to neutralize the crest of Hill 52 prior to the infantry attack, but L Company had moved too rapidly. The artillery could not fire on Hill 52’s crest without endangering the platoon. While the 1st Platoon hugged the ground American artillery put fire on targets beyond Hill 52 but did not dare risk shelling the enemy strong point.26 American 37-mm. guns and mortars put direct fire on and over the crest, but the 37’s could not reach the Japanese troops, who were defiladed by the sheer drop. Mortar fire could have hit the enemy on Hill 52, but the 3rd Battalion mortar crews did not know the exact location of the enemy weapons.

Captain Roholt ordered the platoon to withdraw 100 yards east to enable him to cover the whole crest with mortar fire. The message was relayed to the platoon leader, but, as the words “100 yards” had been inadvertently dropped from the message by the time he received it, he pulled his men all the way back to Hill 51.27 L Company did not then renew the assault against Hill 52 but continued to fire at the crest. Captain Roholt informed Colonel Bush that the terrain created difficulties of control and communication which made a deep southern envelopment impracticable. He advised the colonel to abandon the idea of envelopment from the south.

Meanwhile Capt. H. H. Johnson, Jr. was leading I Company in its attempted northern envelopment on the battalion’s right. At 0635 I Company had moved off Hill 54 in column of platoons to advance along the edge of the woods north of the Horse. The enemy fired at Captain Johnson’s company from two directions, with the machine guns and mortars emplaced on Hill 52 on the left, and with rifles from the woods on the right. Captain Johnson was forced to deploy an entire platoon to cover his right flank. The company established a base of fire on a small ridge about 200 yards southwest of Hill 54 and prepared to attack Hill 52.28 While mortars and antitank guns struck Hill 52,

I Company assaulted uphill, but the enemy machine guns and mortars stopped it 200 yards short of the objective. The attempted double envelopment thus failed on both flanks.

Captain Johnson requested help at 0930. In view of this request and the impracticability of a southern flanking movement, Colonel Bush decided to commit K Company, and to shift his attack to the north to envelop Hill 52 from the northeast and north. He ordered Capt. Ben F. Ferguson, commanding K Company, to advance west beyond I Company to make a deeper envelopment. Slowed by rifle and machine-gun fire, K Company covered the 900 yards between its reserve position on Hill 54 and the north slopes of Hill 52 by 1300. While K Company was advancing along the edge of the woods, the heavy weapons on Hill 54 and L Company’s 60-mm. mortars on Hill 51 continued to fire on Hill 52.

Colonel Bush’s final plan for the capture of the hill called for another envelopment. The holding force, I Company, was to attack from the northeast while K Company, with one rifle platoon from L and a machine gun platoon from M Company attached, enveloped the position from the north. L Company, holding Hill 51 with one platoon, was in reserve. The attack would be supported by field artillery fire, machine guns, mortars, and antitank guns. The assaulting units moved into position; by about 1400 Colonel Bush had determined the exact location of the assault companies, although the battalion command post on Hill 54 had been harassed by enemy rifle fire. The forward observer then called for artillery fire to be delivered on the crest of Hill 52, but a communication failure delayed the artillery until 1430.29

About noon, after the 3rd Battalion’s attack had bogged down, Colonel McCulloch had sent the air support commander forward to confer with Colonel Bush on Hill 54. The 3rd Battalion commander had shown him the most likely targets on the Galloping Horse, and the air officer had agreed to bomb Hill 52 at 1500 unless the hill had been captured by that time. An artillery smoke shell was to mark the target and indicate to the pilots that they were to execute the planned bombing mission. Bush’s plan called for K Company to assault Hill 52 before 1500, and had Hill 52 fallen before then, the planes were not to drop their bombs. By 1430, when the artillery was ready to fire the concentration on Hill 52, the planes were overhead. Colonel Bush decided to use the planes despite the fact that K Company would have to withdraw the right (western)

27th Infantry Area, 10 January 1943, as seen from the air

part of its deployed front, which lay along a prolongation of the bombing line, which ran from north to south. Delayed bomb releases would have endangered the troops.

The planes bombed Hill 52 successfully; they spaced the depth charges well.30 Not one fell on the east slope but all hit the reverse slope. Four charges exploded on the target, and two were duds. After the bombing four howitzer battalions put a 20-minute concentration on Hill 52. When the 105’s ceased firing, the 37-mm. guns and mortars fired in support of the infantry.

Under cover of the 37-mm. and mortar fire, the infantrymen launched a coordinated attack. K Company had resumed its position on the north slopes of Hill 52. The platoon from L Company covered the gap between K and I. The soldiers crawled close to the crest under cover of the supporting fire, then, with bayonets fixed, rushed and captured it.31 By 1635 the 3rd Battalion had cleaned out the enemy’s positions on the western slopes, captured six machine guns which had survived the bombardment, killed thirty Japanese, and secured the hill. The battalion did not attack again that day but organized a cordon defense on Hill 52 for the night.

The 25th Division, carrying out the most ambitious divisional offensive on Guadalcanal since the capture of the Lunga airfield, had made good progress in its first day of combat. The artillery fire had been especially effective. The 1st Battalion, 27th Infantry, had reached the division objective in its zone. The 3rd Battalion, meeting heavier resistance, had advanced 1,600 yards toward its objective and captured Hills 50, 51, and 52. Over half the Galloping Horse was in American hands. Patrols from the 1st Battalion had reached Hill 52 to make contact with the 3rd Battalion. Colonel Mitchell’s 2nd Battalion, 27th Infantry, in regimental reserve, occupied the Hill 50–51 area, and had established contact between the 3rd Battalion, 27th Infantry, and the 3rd Battalion, 182nd Infantry, on the Matanikau. American casualties had been light.32 It had not been necessary to commit the division reserve, the 161st Infantry.

The Second Day

The 3rd Battalion of the 27th Infantry prepared to renew its attack toward Hill 53 on 11 January but was faced with a shortage of water. Very little drinking

water had been brought forward to the 3rd Battalion during its fight on 10 January, which was a hot, sunny day. Springs and streams are usually plentiful in the Solomons, but there was then no running water on the Galloping Horse. Colonel Bush delayed his attack against Hill 53 on 11 January until after 0900 in the vain hope that water would reach his thirsty troops. The water point at the foot of Hill 55 was adequate and the supply officer had sent water up the trail but units in the rear had apparently diverted it before it could reach the soldiers in combat.33 As most of the soldiers of the 3rd Battalion had entered combat with but one canteen of water, they had to attack on 11 January carrying only the water which remained in their canteens from the previous day.

Colonel Bush’s plan for 11 January called for two companies to attack abreast after artillery bombardment. On the left I Company was to deploy on the ridge along the top of the gorge and attack southwest over the first ridge (Exton Ridge) west of Hill 52, to the next ridge (Sims Ridge) 200 yards away, while it secured its rear and left flank with one platoon. K Company, following, was to pass through I on Sims Ridge to take Hill 53 which lay 850 yards beyond Hill 52. On the right, L Company was to advance northwest from Hill 52 to that part of Hill 57 which lay in the 3rd Battalion zone, make contact with the 1st Battalion, drive south to clear the woods between Hills 57 and 53, and make contact with K and I Companies. One machine gun platoon from M Company was to accompany each assault company; the 81-mm. mortars were to remain on Hill 54. Colonel Bush assigned eleven men from Headquarters and M Companies to carry water to the advancing troops.

Both assault companies moved off the right (north) end of Hill 52 after the artillery preparation. The security platoon of I Company reached a narrow bottleneck west of Hill 52 between two ridges. The rest of the company followed. When fire from Japanese mortars, machine guns; and rifles began to hit them, the soldiers halted. I Company requested that mortars and artillery put fire on the enemy but did not move forward nor maneuver to the enemy flanks.34 Squeezed in the narrow gap, the company was hit repeatedly by mortar fire. Many spent and thirsty men collapsed. In one platoon only ten

men were still conscious at noon.35 Mortar fragments wounded Captain Johnson about 1300, and he was evacuated.

Also unsuccessful was L Company’s attack. The lead platoon and one attached machine gun platoon cut through the ravine north of Hill 52 to secure the right flank. They turned west, and advanced to Hill 57, then turned left to climb the southeast slopes. When heavy machine-gun fire from the flanks and rear halted them, they dug in to await the main body, which did not arrive. When dusk fell the two platoons, out of communication with the battalion, returned to Hill 52.36 The main body of L Company had not advanced, but had deployed behind I Company to hunt down scattered enemy riflemen.

By midafternoon Colonel Bush felt certain that the 3rd Battalion could not take its objective that day. Since the position reached by I Company was untenable, I and L Companies returned to Hill 52 for the night. After dusk the force which had been halted on Hill 57 also returned. Between 1500 and 1600 accurate, heavy Japanese mortar fire forced the 3rd Battalion to take cover, and delayed defensive preparations for the expected night attack. The enemy did make a slight effort to infiltrate the lines that night, but was repulsed by L Company.

Colonel McCulloch ordered the exhausted 3rd Battalion to go back to Hills 55 and 54 into regimental reserve on the morning of 12 January, and Colonel Mitchell’s 2nd Battalion took over the assault against the ridges and Hill 53. Up to this time the 2nd Battalion had held the rear areas taken by the 3rd Battalion and had helped to carry supplies forward. The 1st Battalion of the 161st Infantry then took over the Hill 50–51 area.

The Third Day

Colonel Mitchell planned to attack on 12 January to capture Hill 53 and that part of Hill 57 which lay in his zone. (Map XV) The attack was to be delivered from Hill 52 with two companies abreast. F would be on the left, G on the right, and E in reserve. F Company was to capture Hill 53, while G Company moved to the right to join with the 1st Battalion on Hill 57. H Company was to emplace its heavy machine guns and 8i-mm. mortars on Hill 52. Artillery and aerial bombardments were to support the infantry’s attacks.

After a preliminary bombardment both assault companies moved out of the cordon defense on Hill 52 at 0630, 12 January. On the right G Company advanced to the north and west. Some enemy riflemen in the woods north of Hill 52 opened fire but were hunted down by patrols from G Company. As the company moved west Japanese in the jungle north of Sims Ridge opened fire, but G Company continued its march and by noun had made contact with the 1st Battalion on Hill 57.

G Company was the only unit which reached its objective on 12 January. In general, vigorous Japanese resistance halted the 2nd Battalion’s advance. At the beginning of the day the Japanese were occupying Exton Ridge, and Sims Ridge 200 yards west of Exton; Hill 53 southwest of Hill 52; the jungle north of Sims; and the shallow dip between Exton and Sims Ridges. Enemy machine guns covered all approaches, and the steep precipice above the southwest Matanikau fork prevented F and E Companies from enveloping the enemy from the south.37

F Company attacked Exton Ridge but moved too far to the right and exposed the battalion’s left flank. By then the Japanese had pulled off Exton Ridge and F Company took it quickly but could advance no farther toward Hill 53. Colonel Mitchell then committed his reserve, E Company, to F’s left to cover the battalion’s south (left) flank, but E Company also failed to advance beyond Exton Ridge.38 Fire from Sims Ridge held both companies in place, Colonel Mitchell decided to envelop Sims Ridge. He withdrew F Company from Exton and ordered it to move to the right to attack Sims Ridge from the north. E Company continued its attack but failed to progress. When F Company attacked southward against Sims it was able to capture the north slopes, but about halfway to the crest it was halted by an enemy strong point that was dug in on the reverse (west) slope. At first the soldiers could not locate the position which machine guns were defending from all sides. Meanwhile E Company, trying to advance over Exton, in avoiding enemy fire had moved to the right and partly intermingled with F Company.

To give closer support to the assault companies, H Company then moved its heavy machine guns to Exton Ridge.39 On Sims Ridge the infantry sought out the enemy strong point. Capt. Charles W. Davis, the battalion executive

officer, with Capt. Paul K. Mellichamp and Lt. Weldon Sims crawled down the east side of the ridge behind a waist-high shelf, a natural approach. When Lieutenant Sims exposed himself above the shelf, a Japanese machine gunner shot him fatally through the chest. His companions then pulled his body down and returned to the 2nd Battalion lines.40

When the strong point was thus approximately located, American machine guns and mortars opened fire while the infantry made one more effort to overcome the enemy. Captain Davis crawled behind the shelf close to the strong point and radioed firing data to H Company’s 81-mm. mortar squads. As both he and the men of E and F Companies were then less than fifty yards from the enemy the exploding shells showered dirt, rock chips, and fragments among them, but failed to destroy the enemy position.41 The enemy machine guns were still in action and kept the American infantry in place.

Meanwhile Colonel Mitchell had left the battalion command post on Hill 52 to join the assault companies on Sims Ridge. As the Japanese and Americans on Sims Ridge were within grenade-throwing distance of each other, he decided not to use 81-mm. mortars. The 1st Battalion mortar sections on the north end of Hill 57 offered to fire at troops visible to them on Sims, but Colonel Mitchell feared that the troops were his own and declined. By the time the last attacks by E and F Companies had been halted halfway to the objective, the day was nearly gone.

By late afternoon the two companies had exhausted their drinking water; the men were on the verge of collapsing. They organized an all-round defense on the north slopes of Sims Ridge in anticipation of a Japanese night counterattack. Colonel Mitchell decided to spend the night with the troops on Sims Ridge instead of returning to the battalion command post on Hill 52, for the regimental executive officer was then at the command post and could act in emergencies.42

During the day the 8th Field Artillery Battalion had fired the seventeen concentrations requested by Colonel Mitchell. Together with its supporting battalions, the 8th also adjusted fire on Hill 53 in preparation for the next day’s assault.

The Japanese did not attack the 2nd Battalion that night, but they did

succeed in cutting the telephone line between Colonel Mitchell and Hill 52.43 Some of the American soldiers, facing the Japanese for the first time at night, fired indiscriminately in the enemy’s direction.

Fourth Day

The 2nd Battalion’s attack plan for 13 January called for E Company to continue the attack against Sims Ridge from the north. At the same time F Company was to withdraw from the ridge and advance along a covered route between the jungle and the Horse’s neck to attack the north end of Hill 53 H Company was to maintain the base of fire on Hill 52 and Exton Ridge.

E Company attacked as ordered but was immediately hatted by machinegun fire from the strong point. Six volunteers from F Company then worked their way to within twenty-five yards of the strong point, but two were killed by machine-gun fire and the survivors withdrew.

The short distance separating the Japanese from the Americans on Sims Ridge protected the Japanese from 60-mm. mortar fire. E and F Companies fired their 60-mm. mortars from the north end of Sims Ridge but the range was too short and the enemy position too high up to make such firing effective. The 60-mm. squads moved back and fired repeatedly to hit the strong point. They shortened the range until the barrels pointed almost vertically, but they still could not hit the target. For safety’s sake Mitchell ordered the 60-mm. mortars to cease firing.

Colonel Mitchell and the battalion executive officer then devised a plan to break the stale-mate. The colonel took part of E Company down Sims Ridge behind the shelf on the east slope to a point directly east of the enemy. Meanwhile Captain Davis, the executive, and the four survivors of the party which had previously approached the strong point crawled and wriggled their way southward down the west slope close to the enemy position. They were to neutralize the strong point with grenades to prepare the way for Colonel Mitchell’s unit to assault from the east on Davis’ whistle signal.

The five men had crawled to within ten yards of the position when the Japanese hurled grenades at them. Although their aim was accurate, the grenades failed to explode. The Americans replied with eight grenades which did explode, then sprang up to rush the enemy, some of whom fled. Captain Davis’ rifle jammed after one round. He threw it away, drew his pistol, and the five men leaped among the surviving Japanese and finished them with

rifles and pistols. E Company witnessed this bold rush and, in the words of General Collins who observed the day’s fighting and helped to direct mortar fire from Hill 52, “came to life” and drove uphill to sweep the last Japanese from Sims Ridge.44 For his gallant action, Captain Davis later received the Medal of Honor.45

Like the 3rd Battalion on 11 January, the 2nd Battalion had received almost no water after it attacked on 12 January, and thirst might well have caused the 13 January attack to stall. But shortly after E Company had cleared Sims Ridge a quick heavy cloudburst soaked the earth and cooled the soldiers who were able to obtain a little water from standing pools and by wringing their clothes. The amount they obtained, though scanty, proved sufficient to sustain them.46

While F Company was moving along its covered route, three field artillery battalions put fire on Hill 53. When the artillery fire ceased both companies (F and E) attacked Hill 53. E Company advanced south and west along Sims Ridge to seize the high ground on the top of the Horse’s head, and F Company emerged from the jungle to attack the head from the north. The infantrymen capitalized on the shock effect of the artillery by attacking immediately after it stopped firing.47 The 2nd Battalion found that organized Japanese resistance had ceased.48 By 1030 the 2nd Battalion had captured all but the southwest tip of Hill 53; by noon it had taken the entire hill and reached the division’s objective in its zone.49

E Company destroyed a Japanese 70-mm. gun on Hill 53, and captured a number of rifles, grenade dischargers, machine guns, and some ammunition. Colonel Mitchell’s battalion, in two days of action, had lost two officers and twenty-nine enlisted men killed, and had killed an estimated 170 Japanese soldiers from the 228th and 230th Infantry Regiments, 38th Division. A few of the enemy dead wore good clothes and had been in good physical condition, but the remainder were ragged and half-starved.50

G Company, which had made contact with the 1st Battalion on Hill 57

Final attacks on the Galloping Horse were supported by howitzers of the 2nd Battalion, 10th Marines

The 27th Infantry cleaned out the enemy from positions such as the one below, dug into the coral rock hillside and camouflaged with kunai grass laid over a stick framework

on 12 January, sent one platoon to cover the low-flying jungle area between Hills 57 and 53. The next day the 2nd Battalion cut a trail from Hill 53 to Hill 57.

By nightfall of 13 January the western American lines on Guadalcanal extended 4,500 yards inland (south) from Point Cruz across Hill 66 to Hills 57 and 53. The 27th Infantry had taken all its objectives, pocketed the enemy in the river gorges, and was firmly seated on the Galloping Horse, waiting for the 35th Infantry to complete its longer advance to the division’s objective in its zone to the south. From 15 to 22 January the 161st Infantry, in a series of sharp fights, cleaned out the Japanese positions south of the Galloping Horse in the gorge of the southwest Matanikau fork.51 During this period the 27th Infantry fought no more major actions, but mopped up the Japanese remaining in the jungled gorge north of the Galloping Horse, built defense positions, constructed roads, and patrolled to the west to prepare for the next assault.

The Coastal Offensive

The 2nd Marine Division, holding the Hill 66-Point Cruz line on the coast on the right of the 25th Division’s zone of action, remained in place during the first three days of the Galloping Horse action. On 12 January the Marine division received orders from General Patch to begin its advance westward from the Hill 66-Point Cruz line.

This attack, which was to be supported by Americal and 2nd Marine Division artillery and the 2nd Marine Air Wing, was the 2nd Division’s first operation as a complete division. The only fresh infantry regiment in the division was the 6th Marines, which had landed on Guadalcanal on 4 January 1943. The 2nd Marines, which had landed in the Guadalcanal-Tulagi area on 7 August 1942, by January was overdue for relief. The 8th Marines, which had arrived in November, had also taken part in several engagements. In December 1942 the 2nd and 8th Marines had relieved the weary 164th and 182nd Regiments west of the Matanikau, and in January the 6th Marines had begun relieving the 2nd and 8th Marines while those units were in contact with the enemy. Two battalions of the 2nd Marines participated in the attack of 13 January and withdrew to the Lunga perimeter defense the next day. The 8th Marines remained in action until 17 January.

Japanese soldiers from the 2nd Division were then holding the coast sector. In some areas, especially in the wooded ravine just west of the Point Cruz-Hill 66 line, their defenses were very strong. As in November and December enemy machine guns at the head (south end) of each draw were able to pour flanking fire into advancing American troops.

The enemy’s ravine defenses determined the 2nd Marine Division’s plan of attack. The assault was to be delivered in successive echelons from left to right. The units on the left were to move forward to knock out the enemy weapons at the head of each draw, thus clearing space through which the units on the right could maneuver.52

The 2nd Marines opened the attack at 0500, 13 January. (Map XVI) By 0730 the regiment had moved 800 yards west from Hill 66, at a cost of 6 killed and 61 wounded.53 At noon the 6th Marines moved forward to relieve the 2nd.

Ten minutes after the 2nd Marines had jumped off, the leading units of the 8th Marines on the right of the 2nd began the attack. They moved from the east slopes of Hills 80 and 81 toward the ravine to the west. The Japanese in the ravines stopped the move with machine-gun, mortar, and rifle fire. Thus at the end of the first day the left flank units of the 2nd Marine Division had advanced, but the attack in the center had been halted. The 8th Marines tried again on 14 January but failed to gain.

The regiment brought up tanks on 15 January to crack the Japanese emplacements, but failed to achieve much success. In the afternoon the marines brought a flamethrower forward to use it in action for the first time. The flamethrower burned out one Japanese emplacement ten minutes after its two-man operating team reached the front, and burned out two more emplacements later in the day.54

By the end of 17 January the 8th Marines had cleared out the ravine to its front and had advanced its line forward beside the 6th Marines on the left. In five days of fighting the 2nd Marine Division had gained about 1,500 yards. It reported that it had killed 643 Japanese and captured 2 prisoners, 41 grenade dischargers, 57 light and 14 heavy machine guns, 3 75-mm. field pieces, plus small arms, mines, and a quantity of artillery ammunition.55

By 18 January, when the 8th Marines were withdrawn, American troops were holding a continuous line from Hill 53 north to the coast. It reached the beach at a point some 1,500 yards west of Point Cruz. The XIV Corps had gained a position from which it could start its drive into Kokumbona, long a major objective. This drive was begun just before the 35th Infantry of the 25th Division completed its task on Mount Austen.