Chapter 4: Providence Forestalled

The Joint Directive of 30 March 1942 had visualized a defensive phase followed by “major amphibious operations,” which would be launched from the Southwest Pacific and South Pacific Areas. The idea of an offensive of any kind in the Pacific seemed wildly optimistic in March and early April, but the establishment by Admiral King on 29 April of a South Pacific Amphibious Force made up principally of the amphibiously trained and equipped 1st Marine Division was at least a step in that direction.1 While the assignment of this force laid the foundation for an eventual offensive from the South Pacific Area, it was clear that as long as the Japanese enjoyed overwhelming naval superiority in the Pacific, especially in carriers, the offensive would have to wait and the striking forces of both areas would have to remain dispersed and on the defensive. Should it become possible, however, to destroy a substantial portion of Japan’s carrier strength, the way would be open for offensive action in the Pacific with the available means, limited though they were. The opportunity to inflict such a blow upon the Japanese Fleet came in early June, and the Pacific Fleet, which had long waited for the chance, exploited it to the full.

Moving to the Offensive

The Battle of Midway

On 5 May Admiral Yamamoto was ordered to seize Midway and the Aleutians immediately after the capture of Port Moresby. The reverse at the Coral Sea caused the Port Moresby operation to be postponed, and Midway and the Aleutians went into top place on the Japanese operational schedule. On 18 May Yamamoto was further instructed that when he had taken Midway and the Aleutians he was to cooperate with the 17th Army, which had been established that day, in the capture of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Samoa, and in the seizure as well of Port Moresby. Though New Caledonia, Fiji, and Samoa were to be taken first, the seizure of all four objectives was, as far as possible, to be accomplished in one continuous thrust.2

The commander of the 17th Army, Lt. Gen. Haruyoshi Hyakutake, was ordered to attack New Caledonia, Fiji, Samoa, and Port Moresby in order “to cut off communications between America and Australia.” He lost no time in alerting the elements of

his newly formed command—the South Seas Detachment at Rabaul, the Kawaguchi Detachment at Palau, and the Yazawa and Aoba Detachments at Davao—to their part in the forthcoming operations. Hyakutake parceled out the objectives as follows: the South Seas Detachment (the 144th Infantry reinforced) was to take New Caledonia; the Kawaguchi Detachment (the 124th Infantry reinforced) and an element of the Yazawa Detachment (the 41st Infantry) were to move against Samoa; and the Aoba Detachment (the 4th Infantry reinforced) was to land at Port Moresby. All units were to be in instant readiness for action as soon as the Midway-Aleutians victory was won.3

Admiral Yamamoto had meanwhile detailed an immense force to capture Midway including the four large fast carriers Kaga, Akagi, Hiryu, and Soryu. The remainder of Admiral Nagumo’s command, the Shokaku and Zuikaku, were not able to participate because of the action at the Coral Sea.

Admiral Nagumo’s carrier force left Japan for Midway on 27 May, the same day that the transports left Saipan and the cruisers and destroyers, which were to cover them, left Guam. The main body of the fleet, with Admiral Yamamoto in command, left from various Japanese ports a day later.4

The U.S. Pacific Fleet had learned ahead of time of Yamamoto’s intentions. Three aircraft carriers, the Enterprise, Hornet, and Yorktown, lay in wait for the enemy a couple of hundred miles north of Midway. The first sightings of the Japanese force were made on 3 June, and the issue was decided the next morning after a massive attack on Midway by enemy carrier planes.

The last enemy plane had scarcely left Midway when three of the enemy carriers—the Akagi, Kaga, and Soryu—all closely bunched together, were hit fatally by the dive-bomber squadrons of the Enterprise and the Yorktown. The Kaga and Soryu went down late that afternoon; the Akagi, with uncontrollable fires raging aboard, took longer to succumb but was finally scuttled by its own crew that evening. The Hiryu, which had been a considerable distance ahead of the main carrier force, succeeded in knocking out the Yorktown before it too was set afire by dive bombers from the Enterprise and Hornet. Burning fiercely, the Hiryu was scuttled by its crew the next morning.

The loss of the carriers forced Yamamoto to break off the engagement and to withdraw his fleet to the north and west with U.S. naval units in pursuit. The Pacific Fleet had lost a carrier, a destroyer, 150 aircraft, and 300 men, but it had broken the back of the Japanese Fleet and gained one of the greatest naval triumphs in history.5

With the Combined Fleet routed, and its main striking force destroyed, the Allies were at last in a position to seize the initiative. The time had come to counterattack.

The 2 July Directive

The magnitude of the Japanese disaster at Midway was immediately realized. Offensive plans to exploit the new situation

USS Yorktown under Japanese fire during the Battle of Midway

and add further to the enemy’s discomfiture were quickly evolved and presented to the Joint Chiefs of Staffs for consideration.

General MacArthur, who assumed as a matter of course that he would be in command from start to finish since all the objectives lay in his area, had proposed that the operation be an uninterrupted thrust through New Guinea and the Solomons, with Rabaul as the final objective. The Navy, standing for a more gradual approach, insisted that Tulagi would have to be taken and secured before the final attack on Rabaul was mounted. In addition, it had raised strong objections to having General MacArthur in command of the operation, at least in its first, purely amphibious, stages.

General Marshall found it difficult to secure agreement on these issues, but succeeded finally on the basis of a draft directive that divided the operation into three tasks. Task One, the seizure of the Tulagi area, was to be under Vice Adm. Robert L. Ghormley, Commander of the South Pacific Area, while Tasks Two and Three would be under General MacArthur.6

Agreement on the final form of the directive was reached on 2 July. After stating that offensive operations would be conducted with the ultimate objective of seizing and occupying the New Britain–New Ireland–New Guinea

area, the directive laid down the following tasks:

a. Task One. Seizure and occupation of the Santa Cruz Islands, Tulagi, and adjacent positions.

b. Task Two. Seizure and occupation of the remainder of the Solomon Islands, of Lae, Salamaua, and the northeast coast of New Guinea.

c. Task Three. Seizure and occupation of Rabaul and adjacent positions in the New Guinea–New Ireland area.

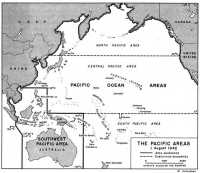

Task One, under Admiral Ghormley, was given a target date of 1 August. MacArthur would not only supply naval reinforcements and land-based air in support of Task One but would also provide for the interdiction of enemy air and naval activities westward of the operating areas. To remove the objection that Admiral Ghormley would exercise command in General MacArthur’s area, the boundary between the Southwest Pacific Area and South Pacific Area would, as of 1 August, be changed to 159° East Longitude, thereby bringing Tulagi and adjacent positions into the South Pacific Area.7 (Map 3)

The SWPA Prepares

Girding for Action

General MacArthur now had a twofold responsibility. His responsibility under Task One was to lend the South Pacific Area the fullest support possible with his aircraft, submarines, and naval striking force. His responsibility under the succeeding tasks was to prepare his command for early offensive action, and this he lost no time in doing.

A change was made in the command of the Allied Air Forces. On 13 July, Maj. Gen. George C. Kenney, then commanding general of the Fourth Air Force at San Francisco, was ordered to take over command of the Allied Air Forces. General Brett was to remain temporarily in command until Kenney’s arrival.8

The U.S. Army services of supply were reorganized. The United States Army in Australia (USAFIA), which was essentially a supply echelon, and not, as its name suggested, an administrative headquarters for U.S. troops in Australia, was discontinued on 20 July. The United States Army Services of Supply, Southwest Pacific Area (USASOS SWPA), with General MacArthur’s deputy chief of staff, Brig. Gen. Richard J. Marshall, in command, was established the same day. General Barnes, like General Brett, was ordered back to the United States for reassignment.9

To achieve more effective control over operations, General Headquarters, Southwest Pacific Area (familiarly known as GHQ), and subordinate Allied land, air, and naval headquarters were moved from Melbourne to Brisbane. The move was completed on 20 July,10 and brought the highest headquarters in the area 800 miles closer to

Map 3: The Pacific Areas, 1 August 1942

the combat zone and in position to make a further forward move should one be required by the trend of operations.

United States antiaircraft units at Perth, which were obviously no longer needed there, were transferred to Townsville, and the 32nd and 41st Divisions were ordered to new camps in Queensland, where they were to be assigned to a corps and given training in jungle warfare.11 The 41st Division, then in training near Melbourne, began to move to Rockhampton on 12 July. A day later, the 32nd Division began to move from Adelaide to a camp near Brisbane.12

The corps command had been given initially to Maj. Gen. Robert C. Richardson, Jr., then Commanding General, VII Corps. However, when it was found that General Richardson (who had reached Australia in early July, in the course of a tour of inspection for General Marshall) had strong objections to serving under Australian command, the assignment went to Maj. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger, Commanding General, I Corps, a classmate at West Point of both Generals Harding and Fuller of the 32nd and 41st Divisions, which were to make up his corps.13

Airfield construction in the forward areas was accelerated. By early July, the airfields in the York Peninsula-Horn Island area were well along, and air force units were occupying them as rapidly as they became ready for use.14 At Port Moresby, seven fields were projected, and work was progressing on four. At Milne Bay, three fields were under way, and one strip was expected to be in full operation by the end of the month.15

These heavy construction commitments made it necessary to send more U.S. engineer troops to New Guinea to assist the American and Australian engineers already there. The 808th Engineer Aviation Battalion, then at Darwin, was put on orders for Port Moresby on 21 July. The 2nd Battalion of the 43rd U.S. Engineers (less Company E, which was at Port Moresby) was ordered to Milne Bay the same day to join with the company of the 46th Engineers, which was already on the ground, in the construction of the crucially needed airfields there.16

Buna and the Theater Plan

The theater plan of operations, the TULSA plan, was revised in the light of the 2 July directive. It had previously merely pointed to the need of a major airfield in the Buna area if Lae and Salamaua were attacked. As revised, it now provided for the immediate establishment of a field in that area in order that it might be available for support of operations against Lae and Salamaua as prescribed by Task Two.17

The problem was how to meet this requirement. There was a small neglected emergency strip just southeast of Buna about which little was known except that it seemed to be too wet and too low lying to be exploited profitably for military use. On 9 July GHQ ordered a reconnaissance of the Buna area. The object of the reconnaissance was to ascertain whether the existing strip had any military value and, if not, to find an all-weather site elsewhere in the area which the military could use.

The PROVIDENCE Operation

The Reconnaissance

The reconnaissance was made on 10 and 11 July by a party of six officers from Port Moresby, who reached the area in a Catalina flying boat. The party was headed by Lt. Col. Bernard L. Robinson, a ranking U.S. engineer officer at Port Moresby, and included three Australian officers who had personal knowledge of the area, Lt. Col. Boyd D. Wagner, U.S. fighter group commander at Port Moresby, and Colonel Yoder. Carefully examining the terrain of the entire area, the six officers found that, while the existing strip was virtually useless for military purposes, the grass plains area at Dobodura fifteen miles south of Buna was an excellent site suitable for large-scale air operations, even in the rainy season which was then only a few months away.

In a special report to General Casey, Colonel Robinson recommended that the existing site not be developed, except perhaps as an emergency landing field for fighter aircraft. The site at Dobodura, on the other hand, he thought almost ideal for large-scale military use. Drainage was good; stone, gravel, and timber in adequate amounts were to be found in the area; and considerable native labor was available locally for the construction of the field. The site would provide ample room for proper aircraft dispersal, and with only light clearing and grading would provide an excellent landing field, 7,000 feet long and more than 300 feet wide, lying in the direction of the prevailing wind.18

The Plan To Occupy Buna

When the news was received at GHQ that Dobodura was an all-weather site, it was decided to establish an airfield there with all possible speed. On 13 July General Chamberlin called a meeting of the representatives of the Allied Land Forces, the Allied Air Forces, the Antiaircraft Command, and the supply services to discuss in a preliminary way the part each could expect to play in the operation. A second meeting was called the next day in which the matter was discussed in greater detail and a general scheme of maneuver for the occupation of Buna was worked out.19

The plan was ready on the 15th, and instructions to the commanders concerned went out the same day. The operation, which was given the code name PROVIDENCE, provided for the establishment of a special unit, Buna Force, with the primary mission of preparing and defending an airfield to be established in the Buna area. At first the airfield would consist only of a strip suitable for the operation of two pursuit squadrons, but it was eventually to be developed into a base capable of accommodating three squadrons of pursuit and two of heavy bombardment.

Brig. Gen. Robert H. Van Volkenburgh, commanding general of the 40th Artillery Brigade (AA) at Port Moresby, was to be task force commander with control of the troops while they were moving to Buna. An Australian brigadier would take command at Buna itself.

The movements of Buna Force to the target area would be in four echelons or serials,

covered by aviation from Milne Bay and Port Moresby to the maximum extent possible. Defining D Day as the day that Buna would first be invested, the orders provided that Serial One, four Australian infantry companies and a small party of U.S. engineers, would leave Port Moresby on foot on D minus 11. These troops were scheduled to arrive at Buna, via the Kokoda Trail, on D minus 1, at which time they would secure the area and prepare it for the arrival of the succeeding serials.

Serial Two, 250 men, mostly Americans, including an engineer party, a radar and communications detachment, some port maintenance personnel, and a .50-caliber antiaircraft battery, would arrive at Buna in two small ships on the morning of D Day. The incoming troops would combine with those already there and, in addition to helping secure the area, would provide it with antiaircraft defense.

Serial Three, the main serial, would include the Australian brigadier who was to take command at Buna, an Australian infantry battalion, an RAAF radar and communications detachment, the ground elements of two pursuit squadrons, an American port detachment, and other supporting American troops. This serial was due at Buna on D plus 1, in an escorted convoy of light coastwise vessels, bringing its heavy stores and thirty days’ subsistence for the garrison.

The fourth serial would consist of a company of American engineers and the remaining ground elements of the two pursuit squadrons that were to be stationed in the area. It would reach Buna from Townsville by sea on D plus 14, accompanied by further stores of all kinds for the operation of the base.

The attention of hostile forces would be diverted from the Buna area, both before and during the operation, by attacks upon Lae and Salamaua by KANGA Force and the Allied Air Forces. Since the “essence” of the plan was “to take possession of this area, provide immediate antiaircraft defense, and to unload supplies prior to discovery,” no steps were to be taken to prepare the airdrome at Dobodura until Serial Three had been unloaded, lest the enemy’s attention be prematurely attracted to it.20

Colonel Robinson, who was to be in charge of the construction of the airfield, was cautioned that no clearing or other work was to be started at Dobodura until the engineers and protective troops had disembarked and the ships had been unloaded. Lt. Col. David Larr, General Chamberlin’s deputy, who had been detailed to assist General Van Volkenburgh in coordinating the operation, made it clear to all concerned that its success depended upon secrecy in preparation and execution. Every precaution was to be taken to conceal the movement, its destination, and its intent. Above all, the existence of the airdrome was to be concealed from the Japanese as long as possible.21

Movement orders for the first three serials were issued on 17 July. Serial One was to leave Port Moresby at the end of the month, 31 July. It would arrive at Buna on 10–12 August, a few days after the Guadalcanal

landing, which, by this time, had been advanced to 7 August.22

The Japanese Get There First

Colonel Larr Sounds the Alarm

General Van Volkenburgh and Colonel Larr had scarcely begun to make their first preparations for the operation when they received the disturbing intelligence on 18 July that the Japanese also appeared to have designs on Buna. Twenty-four ships, some of them very large, had been seen in Rabaul harbor on 17 July, and a number of what appeared to be trawlers or fishing boats loaded with troops had been reported off Talasea (New Britain). The troops, estimated as at least a regiment, were obviously from Rabaul,23 and to General Van Volkenburgh and Colonel Larr, who talked the matter over, it added up to just one thing—that the Japanese were moving on Buna.

Colonel Larr, then at Townsville, at once got General Sutherland on the telephone. Speaking both for himself and General Van Volkenburgh, he noted that Serial One, which was not to begin moving till the end of the month, might reach Buna too late. He proposed therefore that forces be immediately dispatched to Buna by flying boat in order to forestall a possible Japanese landing there. He urged that an antiaircraft battery be dispatched by flying boat to Buna at least by 21 July, and that the PBY’s then go on to Moresby to fly in as many troops of Serial One as possible. The whole schedule of PROVIDENCE, he said, had to be accelerated. Serials Two and Three would have to arrive together; and the occupying force would, if necessary, have to be supplied entirely by air.

Larr went on to say that he knew that the Air Force could not possibly move more than a hundred men into Buna by flying boat at one time. He urged that immediate action be taken nevertheless to accelerate PROVIDENCE, for both he and General Van Volkenburgh felt that the element of surprise had already been lost. He concluded his call with these words: “We may be able to hold Buna if we get there first.”24

General Chamberlin answered for General Sutherland the next day. The troop concentrations at Rabaul and Talasea, General Chamberlin radioed, did not necessarily mean that the Japanese intended a hostile move against Buna. Nor was it by any means certain that the element of surprise had been lost. The suggested plan to occupy Buna immediately was likely to defeat itself because it lacked strength. The danger was that it would serve only to attract the enemy’s attention, and perhaps bring on an enemy landing—the very thing that was feared. For that reason, the original plan would have to be adhered to substantially as drawn. General Van Volkenburgh and Colonel Larr were assured that the dispatch of Serial One to Kokoda would be hastened and that every effort would be made to get it there at the earliest possible moment.25 It was clear however that even

if there was an acceleration it would be slight. D Day would still have to follow the Guadalcanal landing.

The Enemy Crashes Through

The Air Force had meanwhile been striking at Rabaul as frequently as it was able. The bombing had been sporadic at best; and because the B-17’s in use were badly worn, and the bomber crews manning them (veterans, like their planes, of Java and the Philippines) were tired and dispirited, the results were far from gratifying.26 Thinking to give the men a rest and to gain time in which to put “all equipment in the best possible condition,” General Brett (who continued as air commander, pending General Kenney’s arrival) suspended all bombing missions on 18 July.27 Except for a nuisance raid on Kieta on Bougainville Island by an LB-30 from Townsville, no combat missions were flown on either the 18th or 19th. A single Hudson sent from Port Moresby on the 19th to reconnoiter Talasea and Cape Gloucester (on the northwest tip of New Britain) for some further sign of the troop-laden trawlers which had so disturbed General Van Volkenburgh and Colonel Larr reported no sightings whatever in the area.28

The next morning the picture changed completely. A B-17, staging from Port Moresby, sighted two warships and five other vessels thought to be warships about seventy-five nautical miles due north of Talasea. Two merchantmen, which could have been transports, were sighted just north of Rabaul moving in a westerly direction as if to join the ships off Talasea.29

What followed was a study in frustration. Bad weather set in; there was a heavy mist; and visibility went down to virtually nothing. The air force though on the alert, and with an unusually large number of aircraft in condition to attack, could find no trace of the convoy until 0820 on the morning of 21 July, when a cruiser, five destroyers, and several transports were glimpsed fleetingly ninety miles due east of Salamaua. The convoy, which was seen to be without air cover, was sighted again at 1515 off Ambasi, a point forty miles northwest of Buna. A single B-17 followed by five B-26’s located and attacked it there, but without result. Darkness set in, and, although the Japanese gave away their position by shelling Gona and Buna from the sea at 1800 and 1830, all further attempts to locate the convoy that night proved fruitless.30

The Landing

At 0635 the following morning, the invasion convoy was discovered just off Gona

by an RAAF Hudson.31 The exact point was Basabua, about one and one-half miles south of Gona and about nine miles northwest of Buna. At the moment of discovery, landing operations, though far advanced, were not yet complete. Landing barges were still moving from ship to shore, and supplies, which were being rapidly moved into the surrounding jungle, still littered the beach. Antiaircraft had already been set up ashore, but there were no Japanese aircraft overhead32 despite the fact that Lae was only 160 miles away, and the Japanese, who had air superiority in the region, were suffering from no dearth of aircraft at the time. Fortunately for the Japanese ashore, a heavy haze hung over the area and made effective attack from the air extremely difficult. The Air Force made 81 sorties that morning, dropped 48 tons of bombs, and used up more than 15,000 rounds of ammunition in strafing the area,33 but the results were disappointing.

One transport was hit and went up in flames. A landing barge with personnel aboard was strafed and sunk; a float plane (probably from the Japanese cruiser that had escorted the convoy) was shot down; landing barges, tents, supplies, and antiaircraft installations were bombed and strafed; and a hit was claimed on one of the destroyers. By 0915, all the vessels with the exception of the burning transport, had cleared the area safely and were heading north.34

The Japanese in the landing force lost no time in clearing their supplies from the beach. Shielded by the luxuriant jungle and the deepening haze, they quickly made good their landing. The implications of its success for the Southwest Pacific Area were all too clear. The PROVIDENCE operation had been forestalled by almost three weeks. Plans for the early inception of Task Two had been frustrated. The Papuan Campaign had begun.