Chapter 5: Kokoda Thrust

The landing at Basabua on the night of 21–22 July was a direct outgrowth of the naval reverses the Japanese had suffered at the Coral Sea and Midway. After the Battle of the Coral Sea, they had temporarily postponed the Port Moresby operation with the understanding that they would return to it as soon as succeeding operations against Midway and the Aleutians had been completed. The loss of their first-line carriers at Midway had disrupted these plans. Not only were the Japanese forced to postpone indefinitely the projected operations against the South Pacific island bases, but they had to abandon the idea of taking Port Moresby by amphibious assault. They realized that to use the few remaining carriers for support of a second amphibious thrust against Port Moresby would probably be to lose them to superior carrier forces of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, a risk that they were not prepared to take. Since they were agreed that Port Moresby, which flanked Rabaul, would have to be taken at the earliest possible moment, the problem became one of taking it without carrier support. The successful landing in the Buna–Gona area was the first indication of the manner in which they had chosen to solve that problem.1

Planning the Overland Attack

The Operations Area

The die was cast. The fighting was to be in the Papuan Peninsula, or, as the Japanese insisted on calling it, eastern New Guinea. The peninsula, part of the Territory of Papua, a lush, tropical area, most of it still in a state of nature, lies at the southeast end of New Guinea, forming the tail, so to speak, of that vast, bird-shaped island. Occupying an area of 90,540 square miles, Papua is an Australian possession, annexed by the British in 1884, and turned over to the Australians in 1901. The natives, of Melanesian stock, are at a primitive stage of development; and the fact that their hair is generally frizzly rather than woolly has given Papua its name—Papuwa being the Malay for frizzly or frizzled.

The Japanese could scarcely have chosen a more dismal place in which to conduct a campaign. The rainfall at many points in the peninsula is torrential. It often runs as high as 150, 200, and even 300 inches per year, and, during the rainy season, daily falls of eight or ten inches are not uncommon. The terrain, as varied as it is difficult, is a military nightmare. Towering sawtoothed mountains, densely covered by mountain forest and rain forest, alternate with flat malarial, coastal areas made up of matted jungle, reeking swamp, and broad

Papua

patches of knife-edged kunai grass four to seven feet high. The heat and humidity in the coastal areas are well-nigh unbearable, and in the mountains there is biting cold at altitudes over 5,000 feet. The mountains are drained by turbulent rivers and creeks, which become slow and sluggish as they reach the sea. Along the streams, the fringes of the forest become interwoven from ground to treetop level with vines and creepers to form an almost solid mat of vegetation which has to be cut by the machete or the bolo before progress is possible. The vegetation in the mountains is almost as luxuriant; leeches abound everywhere; and the trees are often so overgrown with creepers and moss that the sunlight can scarcely filter through to the muddy tracks below.

The Owen Stanley Mountains, whose peaks rise to heights of more than 13,000 feet, overshadow the entire Papuan Peninsula, running down its center to Milne Bay like an immense spine. On the northeast, or Buna, side the foothills of the range slope gently to the sea. On the southwest or Port Moresby side, the picture is startlingly different. Sharp ridges which rise abruptly from the southwest coast connect with the main range to produce a geographical obstacle of such formidable proportions that overland crossing is possible only by

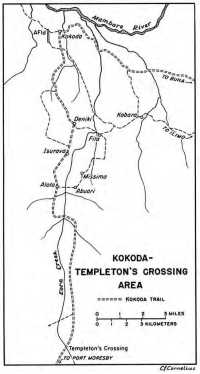

Map 4: Kokoda-Templeton’s Crossing Area

means of tortuous native footpaths or tracks that lead from one native village to the other, often at dizzy heights.

The Kokoda Trail

The best overland route to Port Moresby passed through Kokoda, a point about fifty miles from Buna and more than one hundred miles from Port Moresby. (Maps III and 4) At Wairopi, about thirty miles

southwest of Buna, a wire-rope bridge, from which the place took its name, spanned the immense gorge of the Kumusi River, a broad turbulent stream subject to dangerous undertows and flash floods. Between Buna and Wairopi the country is gentle and rolling. Past Wairopi it suddenly becomes steep and rocky. Kokoda itself is set on a little plateau between the foothills of the Ajura Kijala and Owen Stanley Ranges. On this plateau, which is about 1,200 feet above sea level, there was a small airfield, suitable only for use by light commercial planes and the smaller types of military transport aircraft.

From Kokoda, the trail leads southward along the western side of a huge canyon or chasm, the so-called Eora Creek Gorge. It passes through the native villages of Deniki and Isurava to a trail junction at Alola, where a cross-country trail from Ilimo, a point southwest of Wairopi, joins the main track via Kobara, Fila, Missima, and Abuari, a short-cut which makes it possible to bypass Kokoda. From Alola, the trail crosses to the eastern side of Eora Creek and climbs to Templeton’s Crossing, where the immense spurs of the main range are met for the first time at an elevation of 7,000 feet.

Just past Templeton’s Crossing is the Gap, the mountain pass that leads across the range. The Gap, which is only twenty miles south of Kokoda, is a broken, jungle covered saddle in the main range, about 7,500 feet high at its central point. The saddle is about five miles wide, with high mountains on either side. The trail runs about six miles through the Gap over a rocky, broken track, on which there is not enough level space to pitch a tent, and room enough for only one man to pass. From the Gap, the trail plunges downward to Myola, Kagi, Efogi, Menari, Nauro,

Jungled mountain ridges near the gap in the Owen Stanley’s (photograph taken November 1943)

Ioribaiwa, the Imita Range, and Uberi, traversing in its course mountain peaks 5,000 and 6,000 feet high, and sharp, east-west ridges whose altitude is from 3,000 to 4,000 feet. The southern edge of the range is at Koitaki, about thirty miles from Port Moresby by road, where the elevation is 2,000 feet.

From Kokoda to Templeton’s Crossing the trail climbs 6,000 feet in less than twenty miles as it crosses a series of knife-edged ridges. The peaks in the area rise as high as 9,000 feet, and the valleys, whose sides slope as much as 60 percent from the horizontal, descend as low as 1,000 feet. Ridges rising from creeks and river beds are 1,500 to 2,000 feet high, and the soil in the valleys has up to thirty feet of humus and leaf mold. The area is perpetually wet, the rainfall at 3,000 feet being 200 and 300 inches a year.

The situation is only slightly better between Myola and Uberi. There are still knife-edges and razorbacks, but now they are not as precipitous as before. The gorges, though deeper and with denser undergrowth, are less frequent, but they are still extremely hard to cross. Not till the trail reaches Koitaki does the going moderate. It was a moot point whether a large, fully equipped force could complete the difficult march from Kokoda to Koitaki, in the face

of determined opposition, and still be in condition to launch an effective attack on Port Moresby when it got there. Yet it was by an advance over this trail that the Japanese proposed to take Port Moresby.2

The Enemy Plans a Reconnaissance

The Japanese did not act recklessly in their attempt to send troops over the Owen Stanley Range. On 14 June, six days after Midway, General Hyakutake, commander of the 17th Army, was told to prepare for an overland attack on Port Moresby. General Hyakutake, then on his way to Davao, was specifically cautioned not to order major forces under his command to New Guinea until the trail had been thoroughly reconnoitered, and the operation found to be feasible. He was told that his forces were to be held in readiness for instant action should the reconnaissance have a favorable result. General Horii, commander of the Nankai Shitai, was to have the immediate responsibility for the operation. The 15th Independent Engineer Regiment, a highly trained and well-equipped combat engineer unit stationed at Davao, which had distinguished itself in combat in Malaya, would be assigned to General Horii to perform the reconnaissance.3

On 29 June the engineer regiment, with supporting antiaircraft, communications, medical, and service troops, was ordered to Rabaul, and General Horii flew to Davao on the 30th to receive his orders from General Hyakutake for the reconnaissance. Hyakutake issued the orders the next day, 1 July. They provided that the force making the reconnaissance was to consist of the engineer regiment, an infantry battalion of the Nankai Shitai, the 47th Field Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion, and supporting troops. The force was to be under command of Col. Yosuke Yokoyama, commander of the engineer regiment. Yokoyama’s mission was to land in the Buna area, advance rapidly to Kokoda and “the mountain pass south of Kokoda,” and reconnoiter the trail leading from it to Port Moresby. He was to report to General Horii as quickly as possible on the state of the Buna-Kokoda “road” and on all possible routes of advance from Kokoda to Port Moresby. Horii, in turn, was to pass on the information to higher headquarters with an endorsement setting forth his views on the feasibility of the proposed operation.4

On 11 July, with Colonel Yokoyama on his way from Davao to Rabaul, the Army Section of Imperial General Headquarters gave General Hyakutake the go-ahead signal for the reconnaissance. Hyakutake passed the orders on to General Horii, who at once worked out an agreement with the Navy and the naval air force at Rabaul for the escort and support of Colonel Yokoyama’s force. The latter force reached Rabaul

on the 14th, and two days later Horii ordered Yokoyama to “carry out a landing near Basabua, and quickly occupy a strategic line south of Kokoda in order to reconnoiter the route over which it is intended to advance.” If he found it out of the question to advance beyond Kokoda, he was to occupy and hold the area from the coast westward to the Owen Stanley Range. Yokoyama was specifically ordered to put the “road” east of the Owen Stanley Range in condition to handle motor traffic, and to prepare the “roads” in the mountains for the use, if not of vehicles, at least of pack horses.5

On 18 July, on the eve of the departure of the Yokoyama Force for Buna, General Hyakutake prepared a plan looking to the capture not only of Port Moresby but also of a flanking position at Samarai, a small island just off the southeast tip of New Guinea. Samarai had an excellent harbor and in prewar days had been a trading center of considerable importance. The Japanese, who as yet knew nothing of what was going on at Milne Bay, wanted Samarai (where they believed there was a small Allied garrison) in order to establish a seaplane base there for use in the attack on Port Moresby. The plan provided that the entire strength of the 17th Army—the South Seas Detachment at Rabaul, the Aoba and Yazawa Detachments at Davao, and the Kawaguchi Detachment at Palau—would be committed to these operations. The South Seas Detachment, with the support of the Yazawa Detachment, would take Port Moresby by an advance over the mountains, and the Navy, aided by the Kawaguchi Detachment, would seize Samarai. The Aoba Detachment would remain in army reserve.6

The Japanese apparently were no longer interested in a thorough reconnaissance of the Kokoda Trail. The mission of the Yokoyama Force had changed. Instead of being primarily a reconnaissance force, it had become an advance echelon. Its mission was not so much reconnaissance as to secure a firm foothold in the Buna-Kokoda area. When that was done, the main force would arrive and do the rest.

The Japanese Strike Inland

The Yokoyama Force Departs

The Yokoyama Force was quickly in readiness for the operation. Its troop list included the 1st Battalion, 144th Infantry, the 15th Independent Engineer Regiment (less one company and two platoons), a detachment of the 10th Independent Engineers, a company of the 55th Mountain Artillery, a company of Sasebo 5th Special Naval Landing Force, the 47th Field Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion (less two companies), several signal units, a field hospital section, and a service unit that included supply, transport, water-purification, and port battalion troops. Attached to this force of about 1,800 men were 100 naval laborers from Formosa, 52 horses, and 1,200 Rabaul natives

impressed by the Japanese to act as porters and laborers.7

The Yokoyama Force received its instructions on 16 July and left for Buna four days later with an advance unit of the Sasebo 5th Special Naval Landing Force, in three heavily escorted transports.8 Effective diversions were mounted in support of the Yokoyama Force. As the convoy sped to its target, Japanese naval troops massed at Lae and Salamaua launched heavy raids upon Mubo and Komiatum in the Bulolo Valley, the two most forward outposts of KANGA Force. In addition, Japanese submarines, which had been operating off the east coast of Australia since early June, stepped up their activity and sank four Allied merchantmen the very day of the landing.9

The landing cost the Japanese one ship, the transport Ayatozan Maru, which Allied air units caught and sank as it was unloading off Gona. Forty men and a number of vehicles were lost with the ship. The other two transports, whose cargo had already been unloaded when the air attack began, managed to escape without damage, as did their escort.10

It had been agreed that Buna would be a naval installation, and the advance unit of the Sasebo Naval Landing Force was sent there immediately on landing. Colonel Yokoyama chose Giruwa, about three and a half miles east of the anchorage, as the site of the Army base and immediately ordered all Army troops there. The evening of the landing an advance force under Lt. Col. Hatsuo Tsukamoto, commander of the infantry battalion, was organized at Giruwa and sent southward. The force was composed of the infantry battalion, an attached regimental signal unit, and a company of the 15th Independent Engineers. Tsukamoto, whose orders were “to push on night

and day to the line of the mountain range,” appears to have taken them literally. The attacking force, about 900 men, made its first bivouac that night just outside of Soputa, a point about seven miles inland, and by the following afternoon was approaching Wairopi.11

The Onset

Only light opposition faced the Japanese. MAROUBRA Force, the Australian force charged with the defense of Kokoda and the Kokoda Trail, still had most of the 39th Australian Infantry Battalion on the Port Moresby side of the range. Only Company B and the 300-man Papuan Infantry Battalion were in the Buna-Kokoda area at the time of the landing. Company B, 129 men at full strength, was at Kokoda; the PIB, part of whose strength was on patrol miles to the north, was at Awala, a few miles east of Wairopi.

A grueling overland march from Port Moresby had brought Company B to Kokoda on 12 July. Its heavy supplies and machine guns reached Buna by sea on the 19th; and company headquarters and one platoon, under the company commander, Capt. Samuel V. Templeton, set out from Kokoda the same day to bring them in. After picking up the supplies and machine guns, Templeton had almost returned to Kokoda when the Japanese landed. He turned back at once when he heard the news, and made at top speed for Awala to reinforce the PIB.12

A PIB patrol first sighted the Japanese at 1750, 22 July, a few miles from Awala. The enemy struck at Awala the following afternoon just as the headquarters of Company B and its accompanying platoon reached the area. After a short skirmish, Templeton’s force withdrew, taking up a defensive position that night just short of the Wairopi Bridge. The next day, with the enemy closing in, it pulled back over the bridge and demolished it before the Japanese could make the crossing.13

The thrust toward Kokoda caught General Morris, who, as G.O.C. New Guinea Force, was in command at Port Moresby, at a painful disadvantage. He had been ordered to get the rest of the 39th Battalion to Kokoda with all speed, as soon as the Japanese landed,14 but found himself unable immediately to comply with the order. The problem was that four companies of the 39th Battalion (Headquarters Company and three rifle companies) were on the Port Moresby side of the mountains, including a rifle company in the foothills outside Port Moresby,

and there was only one small aircraft at Port Moresby capable of landing on the small and extremely rough airfield at Kokoda.

Morris did what he could. The battalion commander, Lt. Col. William T. Owen, was immediately ordered to Kokoda by air in the one plane capable of landing there; Company C, the rifle company in the western foothills of the range, was ordered to march on Kokoda as quickly as possible; and the remaining three companies of the battalion, still at Port Moresby, were put on the alert for early movement to Kokoda by air if enough aircraft of a type capable of landing at Kokoda could be secured in time.15

The Fall of Kokoda

Colonel Owen had been instructed to make a stand immediately east of Kokoda, and, if that failed, to take up a position south of it. He arrived at Kokoda on 24 July to find that there was little he could do to stop the onrush of the Japanese. The demolition of the Wairopi Bridge had not held them up long. By the 25th, they had a hasty bridge over the Kumusi and were advancing rapidly on Kokoda. Captain Templeton (whose original force of little more than a platoon had by this time been reinforced by a second platoon of Company B) made a desperate stand that day at Gorari, about eight miles west of Wairopi. The Japanese, attacking with mortars, machine guns, and light field pieces, quickly outflanked him and forced him to withdraw to Oivi, a point in the steep foothills of the range, only eight miles by trail from Kokoda.

General Morris had meanwhile been making every effort to get men forward. Early on 26 July, the small transport aircraft at his disposal made two flights to Kokoda, bringing in thirty men from Company D. Holding half of them at Kokoda, Colonel Owen sent the other half on to Oivi where Captain Templeton was trying to hold in the face of heavy odds. The resistance at Oivi did not last long. Templeton was killed that afternoon, and his tiny force was outflanked and encircled.

Colonel Owen now had no choice but to evacuate Kokoda, and did so just before midnight. After he sent New Guinea Force notice of the evacuation, Owen’s force—the rest of Company B, and the incoming fifteen men of Company D—crossed over the western side of Eora Creek Gorge. It took up previously prepared positions at Deniki, five miles southwest of Kokoda, and was joined next day by those of the Oivi force who had succeeded in extricating themselves during the night from the Japanese encirclement.16

The Fight To Retake the Airfield

New Guinea Force received Owen’s evacuation message late on the morning of 27 July. By then the arrival from Australia of another plane had given General Morris’ headquarters two aircraft suitable for the Kokoda run, and both of them were in the

air at the time loaded with troops and supplies. They were at once recalled to Port Moresby. Next morning Owen counterattacked and, after some bitter hand-to-hand fighting, drove the Japanese out of Kokoda. Owen was now desperately in need of the very reinforcements that New Guinea Force had recalled the previous day. Unfortunately the message that he had regained Kokoda did not reach Port Moresby until late in the afternoon, too late for action that day. Meanwhile, two more planes had come from Australia. New Guinea Force, now with four transports that could land at Kokoda, planned to fly in a full infantry company with mortar and antiaircraft elements the first thing in the morning. The planes were never sent. At dawn on the 29th, the Japanese counterattacked and, after two hours of fighting during which Colonel Owen was killed, again drove the Australians out of Kokoda.17

Australian reinforcements had meanwhile begun arriving in the forward area on foot. Company C reached Deniki on 31 July, followed the next day by Company A. By 7 August, all five companies of the 39th Battalion were at the front, and MAROUBRA Force totaled 480 men. Supplies were being manhandled over the trail by the incoming troops, and by hundreds of native carriers under the supervision of ANGAU. Food and ammunition were also being dropped from the air—a dry lake bed at Myola, a few miles southeast of Kagi, the forward supply base, served as the main dropping ground.18

There were patrol clashes on 7 and 8 August, and early on 10 August MAROUBRA Force, which estimated enemy strength at Kokoda as no more than 400 men counterattacked. Three companies were committed to the assault, with the remaining two held in reserve. While one company engaged the Japanese to the south of Kokoda, a second moved astride the Kokoda–Oivi track via the Abuari–Missima–Fila cutoff and engaged them to the east of Kokoda. The third company marched undetected on Kokoda and took possession of the airfield that afternoon without suffering a single casualty.

The success was short-lived. The company astride the Japanese rear had to be ordered back to Deniki to stem a powerful enemy attack on that point, and the company holding the airfield (whose position had in any event become untenable) had to evacuate it on the night of 11–12 August because of a critical shortage of supplies.19

Colonel Yokoyama was now ready to attack with his full force. Early on 13 August, he struck the Australian position at Deniki with about 1,500 men. The Australians were forced to yield not only Deniki but also Isurava five miles away. The Japanese,

having no intention at the moment of going any farther, began to dig in.20

Kokoda and the Buna-Kokoda track were now firmly in Japanese hands, and a base had been established for the advance on Port Moresby through the Gap. According to plan, the move was to be undertaken as soon as General Horii and the main body of the South Seas Detachment reached the scene of operations.

The Main Force Arrives

The Joint Agreement of 31 July

General Hyakutake arrived at Rabaul from Davao on 24 July to find that Colonel Yokoyama had been reporting good progress in his thrust on Kokoda. As the news from Yokoyama continued good, Hyakutake, seeing no reason for further delay, recommended to Imperial General Headquarters that the overland operation be undertaken at once. Tokyo, which had been well disposed to the project from the first, quickly gave its blessing and, on 28 July, ordered the operation to be mounted as quickly as possible.21

Three days later, on the 31st, General Hyakutake concluded a joint Army-Navy agreement with Vice Adm. Nichizo Tsukahara, commander of the 11th Air Fleet, and Vice Adm. Gunichi Mikawa, commander of the newly established 8th Fleet. Mikawa had just taken over control of naval operations in the New Guinea-Bismarcks-Solomons area from the 4th Fleet. After stating that the seizure of Port Moresby and other key points in eastern New Guinea was necessary in order to secure control of the Coral Sea, the three commanders adopted a basic plan of attack patterned closely on the draft plan which General Hyakutake had prepared on 18 July, thirteen days before.

The plan provided that General Horii, with both the South Seas Detachment and the Yazawa Detachment under his command, would move on Port Moresby via Kokoda, and that the Kawaguchi Detachment, supported by units of the 8th Fleet, would take Samarai. As soon as Samarai was taken, a “Port Moresby Attack Force,” consisting of the Kawaguchi Detachment and elements of the 8th Fleet would be organized there. Then, in a move timed to coincide with diversionary attacks on the Bulolo Valley by the naval troops at Lae and Salamaua, the attack force would embark for Port Moresby, attacking it from the sea at the precise moment that the South Seas and Yazawa Detachments cleared the mountains and began attacking it from landward.

The agreement provided specifically that all the forces at the disposal of the participating commanders would be available for these operations, which were to begin on X Day, the day that the main body of the South Seas Detachment arrived at Buna. X Day was set as 7 August, the date, interestingly enough, of the projected American landing at Guadalcanal.22

Under the joint agreement of 31 July, the 8th Fleet had undertaken to have the airfields at Buna and Kokoda in operation when the main force landed. But this project was not to be easily accomplished. On 29 and 31 July the Allied Air Force caught the enemy supply ships, laden with vehicles and construction materials for the field, while they were en route to Buna. The Kotoku Maru was lost and the rest were obliged to return to Rabaul with their cargo undelivered. These mishaps, and the discovery that the airfield site at Buna was very soggy and could not possibly be put into readiness by 7 August, caused X Day to be moved forward to 16 August.23

The Landings in the Solomons

Pursuant to the Joint Directive of 2 July, the 1st Marine Division, reinforced, went ashore on Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and adjoining islands in the southern Solomons early on 7 August. The Americans quickly dispersed the weak forces the enemy had on the islands, including a few hundred garrison troops and a couple of thousand naval construction troops on Guadalcanal. By the evening of 8 August the marines were in control of Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo and held the airfield at Lunga Point on Guadalcanal, the main objective of the landings.

The 8th Fleet had been busy gathering ships for the Port Moresby operation. Though caught off balance by the landings, it struck back vigorously during the early hours of 9 August. Entering the area between Florida Island and Guadalcanal undetected, the Japanese sank four heavy cruisers, including the Australian flagship Canberra which with other ships of Task Force 44, Admiral Leary’s main force, was in the Solomons supporting the landings. That afternoon the Allied fleet pulled out of the area in accordance with a decision made the previous evening that its ships were vulnerable and would have to be withdrawn. No sooner was the withdrawal completed than the 8th Fleet and the naval air units at Rabaul began a day-and-night harassment of the Marine landing force. The next step was to send in troops.24

Here the Japanese ran into difficulties. The 8th Fleet did not have enough naval troops at Rabaul and Kavieng to counter the American landings. The 17th Army, on the other hand, was at a loss to know which of its forces to order to Guadalcanal. The South Seas Detachment, its only unit at Rabaul, was committed to the Port Moresby operation, and the rest of its troops were out of reach at Davao and Palau. After much consultation between Tokyo and Rabaul, it was decided to use the Kawaguchi Detachment, less one battalion, which would remain committed to the capture of Samarai and the subsequent landing at Port Moresby. Because there was no shipping immediately available at Palau with which to get the detachment to its destination, a further decision was made to have another force precede it. The Ichiki Detachment,

which was already at sea and in position to reach the target quickly, was given the assignment.

These decisions had scarcely been made when Rabaul discovered for the first time that the Allies were building an airfield at Milne Bay and had a garrison there. It was a startling discovery. Realizing that their reconnaissances of the area had been faulty, and that they had almost attacked the wrong objective, the Japanese at once abandoned the Samarai operation and chose Rabi, near the head of Milne Bay, as the new target. It was to be taken by the same battalion of the Kawaguchi Detachment which had previously been assigned to the capture of Samarai, plus such naval landing units of the 8th Fleet as would be available at the time of the operation.25

The Japanese Build-up at Buna

At Buna, meanwhile, the Japanese buildup was proceeding. It had been interrupted by the Allied landings in the southern Solomons, but not seriously. For example, a convoy carrying the 3,000 men of the 14th and 15th Naval Construction Units, their construction equipment, vehicles, and some army supplies had left Rabaul for Buna on 6 August. It was recalled next day by the 8th Fleet when it was only part of the way to its destination. Held over at Rabaul till the situation in the Solomons clarified itself, the convoy left Rabaul a second time on the night of 12 August and, though heavily attacked from the air on the way, reached Basabua safely the following afternoon. By early morning of the 14th, the ships were unloaded and on their way home. Next morning as work began on the Buna strip and on a dummy strip immediately to the west of it, the ships, despite more air attacks, arrived back at Rabaul undamaged.26

The main body of the Nankai Shitai (less a rear echelon which was to come later) left Rabaul on 17 August in three escorted transports. Aboard were Detachment Headquarters under General Horii; the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 144th Infantry with attached gun company, signal unit, and ammunition sections; the two remaining companies of the 55th Mountain Artillery; the rest of the 47th Field AAA Battalion; a company of the 55th Cavalry with attached antitank gun section; part of the divisional medical unit, a base hospital, a collecting station, and a divisional decontamination and water-purification unit. A naval liaison detachment, a couple of hundred more men of the Sasebo 5th Special Naval Landing Force, 700 more Rabaul natives, 170 horses, and a large tonnage of supplies were also in the convoy.27

Without being detected by Allied air units, the transports reached Basabua in the late afternoon of 18 August and were unloaded

quickly and without incident. Strangely enough, the transports were not attacked during the entire time they were at anchor, nor even while they were on their way back to Rabaul. The Allied Air Forces had been caught napping. The biggest prize of all, the main body of the Nankai Shitai and Detachment Headquarters, had landed safely.

The Yazawa Detachment, the 41st Infantry Regiment under its commander, Col. Kiyomi Yazawa, was next to go. The regiment, detached in March 1942 from the 5th Division, had distinguished itself in Malaya. Like the Nankai Shitai and the 15th Independent Engineers, it was a veteran force with a high reputation for aggressiveness. The Yazawa Force had reached Rabaul from Davao on 16 August and upon arrival had come under General Horii’s command as an integral part of the South Seas Detachment.

Rabaul had planned to have the full strength of the regiment, plus the rear echelon of the Nankai Shitai, arrive at the beachhead together. At the last moment, however, it was decided to put aboard a large Army bridge-building and road-construction unit, numbering about a thousand men. This change in plan made it necessary to leave the rear echelon troops and one battalion of the 41st Infantry for a later convoy. As finally loaded on 18 August, the troop list included regimental headquarters and two battalions of the 41st Infantry, a regimental gun unit, signal, ordnance and motor transport troops, a veterinary hospital, a water supply and purification unit, and the bridge-building and road-construction unit. Also aboard were a hundred more men of the Sasebo 5th Special Naval Landing Force, some 200 more Rabaul natives, 200 more horses, several hundred cases of ammunition, five tons of medical supplies, a quantity of gasoline in drums, and large stores of food and fodder.

The convoy left Rabaul on 19 August and landed at Basabua on 21 August in the midst of a storm. There was no interference from Allied aircraft, the ships unloaded safely, and the two battalions of the 41st Infantry made their first bivouac that night at Popondetta about fifteen miles southeast of the anchorage. Except for some 1,500 men—the rear echelon of the Nankai Shitai and the remaining battalion of the 41st Infantry, which were due in the next convoy—the full allocation of troops for the overland push against Port Moresby had arrived at the scene of operations.28

Horii would have a hard time getting additional troops, for things had not gone well at Guadalcanal. The advance echelon of the Ichiki Detachment had reached the island on 19 August. Though the strength of the force was under a thousand men, its commander had attacked at once without waiting for reinforcements. The attacking force was cut to pieces, and General Hyakutake, as a result, again had to change his plans. He returned the battalion of the Kawaguchi Detachment, which had been scheduled for the Milne Bay operations, to its parent detachment for use in the Solomons. Hyakutake then earmarked the Aoba

Detachment, previously in Army reserve, as the landing force for the Milne Bay operation, thus leaving the Army without a reserve force upon which to call in case of need.29

General Horii Takes Over

By this time General Horii had a substantial force at his disposal. A total of 8,000 Army troops, 3,000 naval construction troops, and some 450 troops of the Sasebo 5th Special Naval Landing Force had been landed safely in the Buna–Gona area since the Yokoyama Advance Force had hit the beach at Basabua a month before.30 Even with combat losses which had been light, the desertion of some of the Rabaul natives, and the diversion of a substantial portion of his combat strength for essential supply and communication activities, it was still a formidable force. But whether such a force would be able to cross the Owen Stanley Mountains in the face of determined opposition and still be in condition to launch a successful attack on Port Moresby when it reached the other side, even General Horii, poised as he was for the operation, probably would have found it difficult to answer.

General Willoughby, General MacArthur’s G-2, while admitting the possibility that the Japanese might attempt to cross the mountains in force, found it hard to believe, with the terrain what it was, that they would seriously contemplate doing so. His stated belief in late July was that the Japanese undertook seizure of the Buna–Gona–Kokoda area primarily to secure advanced airfields in the favorable terrain afforded by the grass plains area at Dobodura. They needed the airfields, he submitted, in order to bring Port Moresby and the Cape York Peninsula under attack, and also to support a possible coastwise infiltration to the southeast which would have as its culmination joint Army and Navy operations against both Port Moresby and Milne Bay. He conceded that the Japanese might go as far as the Gap in order to establish a forward outpost there, but held it extremely unlikely that they would go further in view of the fantastically difficult terrain beyond.31

On 12 August, with two landings completed, and a third expected momentarily, General Willoughby still held that “an overland advance in strength is discounted in view of logistic difficulties, poor communications, and difficult terrain.” On 18 August, the day that the main body of the Nankai Shitai landed at Basabua, he again gave it as his belief that the enemy’s purpose seemed to be the development of an air base for fighters and medium bombers at Dobodura and that, while more pressure could be expected in the Kokoda-Gap area, “an overland movement in strength is discounted in view of the terrain.”32

On 21 August, almost a week after the activity began, Allied air reconnaissance discovered for the first time that the Japanese were lengthening the small low-lying emergency landing strip at Buna which Colonel Robinson had reported as

unsuitable for military use.33 The discovery that the Japanese were building airfields in the Buna area (if only at Buna rather than as they might have done at Dobodura) led General Willoughby to the conclusion that here at last was the explanation for the Japanese seizure of the beachhead. The fact that they had done so, he thought, had nothing to do with a possible thrust through the mountains, for an overland operation against Port Moresby was to be “discounted in view of the logistical difficulties of maintaining any force in strength” on the Kokoda Trail.34

The same day that General Willoughby issued this estimate, General Horii, who had previously been at Giruwa, left the beachhead for Kokoda to take personal charge of the advance through the Gap.35 The overland operation against Port Moresby, which General Willoughby had been so thoroughly convinced the Japanese would not undertake, was about to begin.